Abstract

Background

Magnesium salts bind dietary phosphorus, but their use in renal patients is limited due to their potential for causing side effects. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of magnesium carbonate (MgCO3) as a phosphate-binder in hemodialysis patients.

Methods

Forty-six stable hemodialysis patients were randomly allocated to receive either MgCO3 (n = 25) or calcium carbonate (CaCO3), (n = 21) for 6 months. The concentration of Mg in the dialysate bath was 0.30 mmol/l in the MgCO3 group and 0.48 mmol/l in the CaCO3 group.

Results

Only two of 25 patients (8%) discontinued ingestion of MgCO3 due to complications: one (4%) because of persistent diarrhea, and the other (4%) because of recurrent hypermagnesemia. In the MgCO3 and CaCO3 groups, respectively, time-averaged (months 1–6) serum concentrations were: phosphate (P), 5.47 vs. 5.29 mg/dl, P = ns; Ca, 9.13 vs. 9.60 mg/dl, P < 0.001; Ca × P product, 50.35 vs. 50.70 (mg/dl)2, P = ns; Mg, 2.57 vs. 2.41 mg/dl, P = ns; intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), 285 vs. 235 pg/ml, P < 0.01. At month 6, iPTH levels did not differ between groups: 251 vs. 212 pg/ml, P = ns. At month 6 the percentages of patients with serum levels of phosphate, Ca × P product and iPTH that fell within the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) guidelines were similar in both groups, whereas more patients in the MgCO3 group (17/23; 73.91%) than in the CaCO3 group (5/20, 25%) had serum Ca levels that fell within these guidelines, with the difference being significant at P < 0.01.

Conclusion

Our study shows that MgCO3 administered for a period of 6 months is an effective and inexpensive agent to control serum phosphate levels in hemodialysis patients. The administration of MgCO3 in combination with a low dialysate Mg concentration avoids the risk of severe hypermagnesemia.

Keywords: End-stage renal disease, Hemodialysis, Magnesium carbonate, Phosphate-binders

Introduction

Normalization of the serum phosphate level is the cornerstone of medical protocols aimed at preventing and treating secondary hyperparathyroidism. Moreover, it has been shown that elevated serum levels of phosphate and the calcium–phosphate product (Ca × P) play an important role in the development of extraosseous calcifications and are associated with increased mortality in hemodialysis patients [1, 2]. The ingestion of phosphate-binding agents in conjunction with dietary phosphate restriction and its adequate removal by dialysis are the cornerstones of serum phosphate control in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients. However, four decades after the introduction of chronic hemodialysis in early 1960s, we have not yet found the ideal phosphate binder(s) in terms of combined efficacy, safety and low cost. Aluminum and calcium salts and non-aluminum and non-calcium agents, such as sevelamer and lanthanum carbonate, all have advantages and disadvantages [3]. Magnesium-containing agents are aluminum- and calcium-free and are inexpensive phosphate-binders and, to date, their potential has not been explored extensively. In studies involving small series of both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients, magnesium carbonate (MgCO3) and magnesium hydroxide [Mg(OH)2] have been administered either alone or in combination with calcium salts with good results [4–10]. However, these compounds are not widely used in ESRD patients because nephrologists have an inordinate fear of hypermagnesemia and the belief that Mg administration frequently is accompanied by gastrointestinal disorders.

We carried out this study in hemodialysis patients to evaluate the efficacy and safety of MgCO3 as a phosphate-binder when given with a concurrent low dialysate magnesium solution. The control of serum phosphate in the two groups of patients was the primary outcome, while secondary outcomes were changes in serum calcium, magnesium, Ca × P and PTH levels and changes in bowel movements.

Subjects and methods

Patients and study design

Stable ESRD patients on maintenance hemodialysis in our renal unit participated in the study. The protocol of this project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital. Exclusion criteria were: age <18 years, hemodialysis for less than 6 months, psychiatric or other disorders leading to non-compliance, unlikeliness to continue hemodialysis for more than 6 months in the same facility, critical illness at the time of recruitment, previous parathyroidectomy, severe hyperparathyroidism [serum intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) > 500 pg/ml], normal serum phosphate (<5.5 mg/dl) without phosphate-binders, diseases resulting in diarrhea and the lack of informed consent. A total of 54 patients met the criteria and were approached for enrolment. The inclusion period lasted 2 months, between March 2 and April 29, 2006. Enrolled patients signed an informed consent and thereafter entered a 4-week washout period during which we withdrew all phosphate-binders as well as vitamin D medications. After the washout phase, three patients were removed because they had serum phosphate levels lower than 5.8 mg/dl; the remaining 51 patients were allocated to receive either MgCO3 tablets (MgCO3 group) or calcium carbonate tablets (CaCO3 group) for 6 months. We chose CaCO3 instead of calcium acetate because the latter is not commercially available in Greece. Four patients did not agree to consume MgCO3 but did agree to participate by taking their standard binder of CaCO3; we allocated these patients to the CaCO3 group, whereas the remainder of the patients were randomly allocated with a ratio 1:1 to either the CaCO3 (21 randomly assigned patients plus 4 = 25 patients) or to the MgCO3 (26) group. Each MgCO3 tablet contained 250 mg MgCO3, which is equivalent to 71 mg of elemental magnesium, and each CaCO3 tablet contained 420 mg of CaCO3 equivalent to 168 mg of elemental calcium. All patients were on the same standard dialysis schedule (three times weekly × 4 h), and in all of the patients the delivered dose of hemodialysis, as calculated by applying the single pool Kt/Vurea index using the second-generation formula of Daugirdas [11],, was ≥1.35. In both groups, calcium concentration in the dialysate bath was 1.50 mmol/l, whereas magnesium concentration was 0.48 mmol/l in the CaCO3 group and 0.30 mmol/l in the MgCO3 group. The National Kidney Foundation (NKF) suggests a bath calcium dialysate concentration of 1.25 mmol/l (based on opinion, not on evidence). We used a bath concentration 1.50 mmol/l because we wanted to avoid episodes of hypocalcemia, particularly in the MgCO3 group. The patients should be more susceptible to manifest hypocalcemia since they did not receive vitamin D. The starting dose of both phosphate-binders were three tablets of MgCO3 or CaCO3 daily; the dose was adjusted thereafter according to the serum phosphate values: weekly for the first month and then monthly. The dosage of the study drug was increased to one or two tablets per meal as required to achieve the target of serum phosphate level ≤5.5 mg/dl. Based on our clinical experience, to achieve adequate control of serum phosphate we set the maximum daily dose of CaCO3 to 3780 mg (nine tablets), which is equivalent to 1512 mg of elemental calcium, and the maximum daily dose of MgCO3 to 2250 mg (nine tablets), which is equivalent to 639 mg of elemental magnesium. Each patient’s full biochemical profile was obtained at baseline, then weekly during the first month and monthly thereafter. Parathyroid hormone was measured at baseline and then at monthly intervals. If a patient developed hypercalcemia (serum Ca > 10.5 mg/dl), the daily dose of CaCO3 was reduced by one or two tablets. The same was done in patients with severe hypermagnesemia, which is defined as a serum magnesium level >3.5 mg/dl. If severe hypermagnesemia persisted for more than 3 weeks, the administration of MgCO3 was stopped, and the patient was dropped from the study. No patient received vitamin D or a calcimimetic agent during the study. Serum total calcium values were corrected to the serum albumin values.

Statistical analysis

The laboratory values were expressed as mean [± one standard deviation (SD)].

Student’s two-tailed unpaired t test was used to compare values between the two groups of patients at baseline and at 6 months. We used repeated measures of analysis of variance (repeated ANOVA method) to test for differences between the two treatment groups in average values of calcium, phosphate, Ca × P, magnesium, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and PTH over time (time-averaged mean value differences). The chi-square test was applied to determine differences in the prevalence of laboratory data. Significance was set at a P level of <0.05.

Results

Of the 26 patients enrolled in the MgCO3 group, one dropped out due to non-compliance. Of the remaining 25 patients, two (8%) discontinued ingestion of MgCO3 and dropped out: one (4%) because of persistent diarrhea, and one (4%) because of recurrent hypermagnesemia. Of the 25 patients in the CaCO3 group; five were removed from the study (two received a kidney transplant, one died (pneumonia), one suffered a stroke and was unable to swallow tablets and one moved to another hospital). The use of phosphate-binders and vitamin D by the patients before the washout period is given in Table 1. Patients’ mean serum values at baseline and at the end of the follow-up period are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The monthly follow-up of the mean biochemical parameters are shown in Figs. 1–4. The mean Kt/Vurea was 1.379 ± 0.026 in the MgCO3 and 1.381 ± 0.027 in the CaCO3 group.

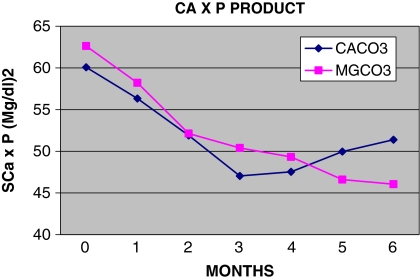

Fig. 2.

Monthly follow-up of serum calcium (sCa)

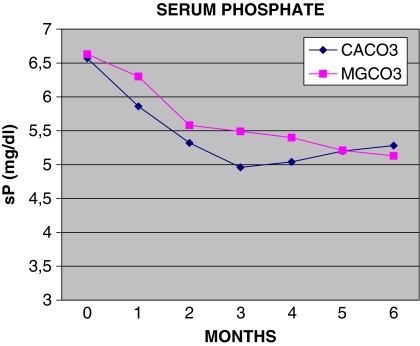

Fig. 3.

Monthly follow-up of serum Ca × P product (SCa × P)

Table 1.

Patients’ data in terms of the use of phosphate-binders and vitamin D before the washout period

| MgCO3 group (n = 25) | CaCO3 group (n = 21) | |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D | 11/25 | 8/21 |

| Phosphate binders | 25/25 | 21/21 |

| CaCO3 | 19 | 16 |

| Sevelamer | 2 | 4 |

| CaCO3 + sevelamer | 4 | 1 |

Table 2.

Mean serum values at baseline

| MgCO3 group | CaCO3 group | P value (t test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.23 | 65.32 | P = ns |

| SD | 12.19 | 11.68 | |

| Calcium (mg/dl)a | 9.42 | 9.14 | P = ns |

| SD | 0.54 | 0.43 | |

| Phosphorous (mg/dl) | 6.63 | 6.58 | P = ns |

| SD | 0.86 | 0.88 | |

| Ca × P product (mg/dl)2 | 62.62 | 60.08 | P = ns |

| SD | 10.36 | 8.35 | |

| Magnesium (mg/dl) | 2.38 | 2.36 | P = ns |

| SD | 0.28 | 0.29 | |

| ALP (IU/l) | 76 | 86 | P = ns |

| SD | 37 | 35 | |

| Intact PTH (pg/ml) | 316 | 296 | P = ns |

| SD | 182 | 157 |

SD, Standard deviation; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; PTH, parathyroid hormone; ns, not significant

aSerum total calcium level corrected to serum albumin

Table 3.

Mean values at 6 months

| MgCO3 group | CaCO3 group | P value (t test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium (mg/dl)a | 8.97 | 9.72 | t = 2.16 |

| SD | 0.57 | 0.42 | P < 0.05 |

| Phosphorous (mg/dl) | 5.12 | 5.28 | t = 0.49 |

| SD | 0.70 | 0.74 | P = NS |

| Ca × P product (mg/dl)2 | 46.04 | 51.38 | t = 0.30 |

| SD | 7.65 | 7.75 | P = NS |

| Magnesium (mg/dl) | 2.59 | 2.40 | t = 1.59 |

| SD | 0.43 | 0.41 | P = NS |

| ALP (IU/l) | 89 | 84 | t = 0.46 |

| SD | 28 | 26 | P = NS |

| Intact PTH (pg/ml) | 251 | 212 | t = 0.42 |

| SD | 118 | 198 | P = NS |

aSerum total calcium corrected to serum albumin

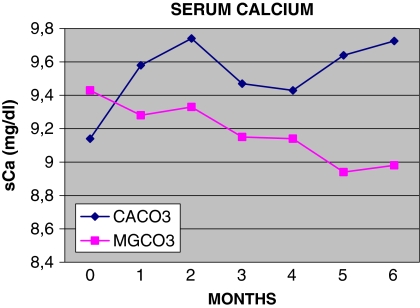

Fig. 1.

Monthly follow-up of serum phosphate (sP)

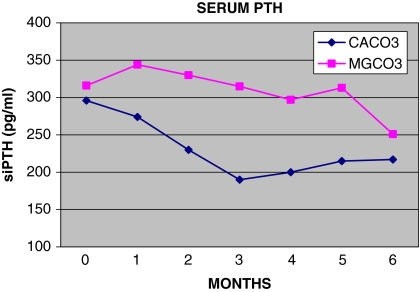

Fig. 4.

Monthly follow-up of serum PTH (siPTH)

The mean daily dose of CaCO3 was 6.76 tablets (range 3–9) containing a total of 2839 mg (range 1260–3780) of CaCO3, which is equivalent to 1136 mg of elemental calcium (range 504–1512 mg) The mean daily dose of MgCO3 was 6.21 tablets (range 3–9) containing a total of 1552 mg (range 750–2,250) of MgCO3, which is equivalent to 441 mg of elemental magnesium (range 213–639 mg). A Shapiro–Wilk test did not indicate any evidence against the normality assumption for the distribution of calcium, phosphate, Ca × P, magnesium, ALP and PTH levels within the two groups (CaCO3 and MgCO3) at any time period during the follow-up. The significance level for the normality tests was set to a = 0.001.

Average values of the biochemical data during months 1–6 are shown in Table 4. The initial mean serum phosphate levels were 6.63 mg/dl in the MgCO3 group and 6.58 mg/dl in the CaCO3 group (P = ns), while at the end of the study serum phosphate values were 5.13 and 5.26 mg/dl in the MgCO3 and CaCO3 groups respectively (P = ns; Tables 2, 3). Time-averaged mean serum phosphate values were 5.47 mg/dl in the MgCO3 group and 5.29 mg/dl in the CaCO3 group (P = ns; Table 4). Serum phosphate levels decreased by 23% in the MgCO3 group and by 19% in the CaCO3 group (P = ns). At the end of the study 17 of 23 (74%) patients in the MgCO3 and 13 of 20 (65%) of the CaCO3 group, (χ2 = 0.10, P = ns) had serum phosphate values within the range recommended by the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) guidelines (upper threshold of 5.5 mg/dl) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Average serum values during months 1–6 of the follow-up period

| MgCO3 group | CaCO3 group | P value (t test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium (mg/dl)a | 9.13 | 9.60 | P < 0.001 |

| SD | 0.53 | 0.45 | |

| Phosphorous (mg/dl) | 5.47 | 5.29 | P = ns |

| SD | 0.81 | 0.93 | |

| Ca × P product (mg/dl)2 | 50.35 | 50.70 | P = ns |

| SD | 7.75 | 8.07 | |

| Magnesium (mg/dl)2 | 2.57 | 2.41 | P = ns |

| SD | 0.41 | 0.32 | |

| ALP (IU/l) | 88 | 80 | P = ns |

| SD | 32 | 27 | |

| Intact PTH (pg/ml) | 285 | 231 | P < 0.01 |

| SD | 161 | 177 |

aSerum total calcium corrected to serum albumin

Table 5.

Patients with laboratory values within the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) guideline range at 6 months

| MgCO3 group (n, %) | CaCO3 group (n, %) | χ2, P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | 17/23 (73.91) | 5/20 (25) | χ2 = 8.42, P < 0.01 |

| Phosphorous | 17/23 (73.91) | 13/20 (65) | χ2 = 0.10, P = ns |

| Ca × P product | 20/23 (86.95) | 14/20 (70) | χ2 = 0.99, P = ns |

| PTH | 11/23 (47.82) | 8/20 (40) | χ2 = 0.79, P = ns |

Mean serum Ca values at baseline were 9.42 mg/dl in the MgCO3 group and 9.14 mg/dl in the CaCO3 group (P = ns) (Table 2). Time-averaged mean serum values were 9.13 mg/dl in the MgCO3 group and 9.60 in the CaCO3 group (P < 0.001) (Table 4). At 6 months, these values were 8.97 and 9.72 mg/dl, respectively (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Seventeen patients (17/23; 74%) who received MgCO3 and only 5/20 (25%) of those on CaCO3 had serum Ca values within the K/DQOI guidelines ( χ2 = 8.42, P < 0.01) (Table 5). We encountered six episodes of hypercalcemia, defined as a serum calcium level >10.5 mg/dl, in the CaCO3 group in comparison to one episode in the MgCO3 group.

The two groups of patients had nearly equal values of serum Ca × P product at the beginning, at the end as well as during the period study (Tables 2–4), with the MgCO3 group having 62.6 mg2/dl2 and the CaCO3 group having 60.1 mg2/dl2 (P = ns) (Table 1). Mean levels of Ca × P during months 1–6 of the follow-up were similar – 50.35 mg2/dl2 in the MgCo3 group and 50.70 mg2/dl2 in the CaCo3 group (P = ns) (Table 4); at the end of the study, the corresponding values were 46.0 and 51.4 mg2/dl2 (P = ns) (Table 3), whereas 20/23 (87%) and 14/20 (70%) patients, respectively, had Ca × P product below the upper limits of K/DQOI recommendations (P = ns) (Table 5).

Starting mean levels of serum iPTH were similar in both groups – 316 ± 182 pg/ml in the MgCO3 group and 296 ± 157 pg/ml in the CaCO3 group (P = ns) (normal range 10–65 pg/ml) (Table 2). During the 6-month follow-up period, average iPTH levels were significantly higher in the MgCO3-treated patients (285 pg/ml) than in those treated with CaCO3 (231 pg/ml) (P < 0.01) (Table 4). However, at the end of the study, those levels did not differ significantly – 251 ± 118 and 212 ± 198 pg/ml, respectively (P = ns) (Table 3). In terms of PTH levels, there was no statistically significant difference between the CaCO3 group and the MgCO3 group – 29 versus 21%, respectively (χ2 = 0.11, P = ns). Moreover, ten of 23 (43%) patients in the MgCO3 group and nine of 20 (45%) in the CaCO3 group had initial levels of iPTH above 300 pg/ml; in three of these ten patients (30%) of the MgCO3 group and five of the nine (56%) of the CaCO3 group, the iPTH decreased below 300 pg/ml [χ2 = 1.38, P = ns; 11/23 (48%)]. Eight of 20 patients (40%) in the CaCO3 group and six of 23 patients (26%) in the MgCO3 group (P = ns) had final values of iPTH below 150 pg/ml. The number of patients of both groups, patients who received MgCO3, and eight of 20 (40%) patients who received CaCO3 who had serum phosphorus, calcium, Ca × P product and iPTH values at 6 months that fell within the range recommended by the K/DOQI guidelines are shown in Table 5 (χ2 = 0.79, P = ns).

During the follow-up period the average serum Mg levels were slightly – but not significantly – higher in the MgCO3 group than in the CaCO3 group: 2.57 vs. 2.41 mg/dl (P = ns) (Table 4). Similarly, at 6 months, these values were 2.59 and 2.40 mg/dl (P = ns) (Table 3). One patient of the 25 (4%) stopped taking MgCO3 because of recurrent high levels of serum magnesium (>3.5 mg/dl, the upper threshold according to our protocol). Two more patients manifested a transient elevation of serum magnesium – from 3.18 to 3.36 mg/dl. No patient in the CaCO3 group had a serum magnesium >3 mg/dl.

Discussion

This is the first study that compares MgCO3 with only one other phosphate-binder in hemodialysis patients. Our results show that MgCO3 administered for a period of 6 months has a good phosphate-binding ability, is well tolerated by most patients and is accompanied by a low incidence of side effects.

O’Donovan et al. [4] described 28 patients on hemodialysis who were given magnesium chloride in place of oral aluminum hydroxide. These patients were also switched from a dialysate containing 0.85 mmol/l magnesium to one not containing any magnesium at all. After 24 months of treatment on this regimen, serum phosphate was effectively controlled in these patients. The researchers saw no evidence of increased secondary hyperparathyroidism. Delmez et al. [5] conducted a 10-week, prospective, randomized crossover study of 15 hemodialysis patients, who were on MgCO3 with a dialysate magnesium concentration of 0.25 mmol/l; with this regimen, these investigators were able to reduce the CaCO3 dose and use a higher dose of calcitriol. Mean serum phosphate levels in the patients were similar with the MgCO3/CaCO3 combination as with the CaCO3 treatment alone (5.7 ± 0.2 vs. 5.2 ± 0.2 mg/dl, respectively), and there were no adverse gastrointestinal effects. Parsons et al. [6] described 32 continuous cycling peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) in patients who were dialyzed with magnesium-free dialysate and used a mixture of CaCO3 and MgCO3 as a phosphate-binder for over 1 year. These patients achieved satisfactory control of hyperparathyroidism, with normal serum calcium, phosphorous and magnesium concentrations. Other investigators have also shown that the use of magnesium-containing agents as phosphate-binders can provide effective control of serum phosphate and hyperparathyroidism and that serum magnesium levels remain within acceptable ranges [7–10]. Spiegel et al. [12] recently compared a regimen of MgCO3 and CaCO3 versus one with calcium acetate and found that the two were equally effective as phosphate-binders.

In our study, MgCO3 was well tolerated by most of our patients – only two of the 25 patients (8%) of this group were removed from the study, one for diarrhea and the other for hypermagnesemia. A third patient complained initially of mild diarrhea and abdominal discomfort, but this resolved after the first week. In comparison, five patients in the CaCO3 arm complained of constipation, but none dropped out of the study.

Serum phosphate levels after the 4-week wash-out period were 6.63 mg/dl in the MgCO3 group and 6.58 mg/dl in the CaCO3 group. These values are lower than those reported by other investigators: 7.7 mg/dl by Qunibi et al. [13] in the CARE study, 7.4–7.7 mg/dl by Chertow et al. [14] in the Treat to Goal study and 6.6–7.2 mg/dl by Asmus et al. [15]. However, in the recently presented preliminary results of the CARE 2 study [16], patients’ mean serum phosphate values were 6.5–6.6 mg/dl. Our values may have been lower because our patients adhered more closely to their diet, they were receiving an adequate dose of hemodialysis or they had neither marked hyperparathyroidism (siPTH <500 pg/ml) nor did they receive vitamin D. The Mediterranean type of diet consumed by our population on the island of Crete is less likely to cause hyperphosphatemia.

The serum phosphate level was reduced equally in both groups, and after the second month of treatment the mean values of serum phosphate in the two groups were comparable. (Table 3; Fig. 1).

In terms of the biochemical findings, the main difference between the two groups was the levels of serum calcium. Hypercalcemia is the price one has to pay for adequate phosphate-binding control with calcium-containing binders; the absence of hypercalcemia is the major advantage of magnesium-based phosphate-binders.

We observed that patients receiving MgCO3 were more likely to have serum calcium levels within the K/DQOI guidelines [17] than those on CaCO3. Both groups of patients achieved a mean serum Ca × P product of <55 mg2/dl2 (Tables 3, 4). Consequently, a significant proportion of patients had a Ca × P product within the K/DQOI recommendations (Table 5).

The risk of severe hypermagnesemia is a major concern when magnesium salts are administered to hemodialysis patients. In such patients serum magnesium levels depend chiefly on the dialysate concentration of this ion, which standardly ranges between 0.45 and 0.50 mmol/l. In the MgCO3 group we used a low magnesium dialysate, 0.30 mmol/l, and this enabled us to avoid extreme hypermagnesemia and keep serum magnesium levels within acceptable ranges.

Clinical symptoms and ECG disorders due to hypermagnesemia appear only when the level of serum magnesium >4 mg/dl [18]. The ionized fraction that represents approximately 60% of the total serum magnesium is the biologically active form of this element. Truttmann et al. [19] and Saha et al. [20] recently demonstrated that the ionized fraction of magnesium lower in HD patients than in individuals with normal renal function; therefore, the incidence of ‘real hypermagnesemia’ may be overestimated in these patients. Of note is that serum magnesium accounts for approximately 1% of the total body magnesium since it is mainly an intracellular cation. Estimation of total body magnesium is based on the determination of intracellular magnesium (IcMg) levels in skeletal muscles or in peripheral lymphocytes [21]. Calculations on the levels of magnesium in these tissues in uremic patients have produced conflicting results, with positive or neutral or even a negative correlation with serum magnesium being found [22, 23].

Although we did not examine the consequences of hypomagnesemia and high serum magnesium levels, various studies have shown that hypomagnesemia plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases and that a high serum magnesium level may retard the development and/or acceleration of arterial atherosclerosis [24, 25]. Meema et al. [26] first showed that ‘hypermagnesemia might be associated with retardation or improvement of arterial calcifications in peritoneal dialysis patients’. Izawa et al. [27] described a hemodialysis patient in whom soft-tissue calcifications resolved after treatment with a dialysate with a high concentration of magnesium. Two studies by our team [28, 29] clearly demonstrated that the absence of mitral annular calcifications and a thinner carotid intima media thickness in hemodialysis patients both correlated with higher levels of serum and intracellular magnesium. In a previous study, we showed that both intracellular and serum magnesium concentrations were directly associated with 5-year survival in 94 hemodialysis patients of our unit [30].

One of the secondary objectives of the study was to investigate if MgCO3 effectively controls serum iPTH. Calcium carbonate was more effective than MgCO3 in decreasing serum iPTH. In the MgCO3-treated patients time-average mean values of iPTH during months 1–6 were significantly higher than in those treated with CaCO3 (Table 4). However, the final levels of serum iPTH at 6 months did not differ significantly between the two groups. Furthermore, at the end of 6 months, a slightly higher number of patients (48%) in the MgCO3 group than in the CaCO3 (40%) group achieved serum iPTH values in the range of 150–300 pg/ml.

In the presence of almost equal serum P values in the two groups, we hypothesize that the relatively higher PTH reduction in the CaCO3 group was due to the significant higher concentration of serum calcium in this group. On the other hand, high levels of serum magnesium have a similar, but weaker, action in suppressing PTH secretion [31]. Figure 4, which shows the monthly follow-up of serum iPTH levels, shows that the curve of the change in mean iPTH values is different in the MgCO3-treated patients in that the mean values increase during the first month of the treatment, subsequently falling (but slower than in the CaCO3 group) and finally, in the sixth month, they approach the mean iPTH values of the CaCO3 group. We speculate that the shape of this curve indicates that suppressive action of serum magnesium on the parathyroid glands is weaker but delayed compared to that of serum calcium. The number of patient who had final serum iPTH values of <150 pg/ml, which could be associated with adynamic bone disease, did not differ in the two groups. However, the impact of the two regimens on the patients’ bone turn over was not included in the objectives of the study, so we did not obtain data associated with bone metabolism markers.

Our experience suggests that a significant proportion of hemodialysis patients need more than one agent to achieve a satisfactory phosphate-binding. In such cases, MgCO3 could be if not the primary at least the second constituent of the phosphate-binding regimen, combined ideally with a calcium-containing salt. An additional advantage is that MgCO3 is much less expensive than the newest sevelamer HCL and lanthanum carbonate.

The limitations of our study are: (1) it is a single-center study, although this has also a number of advantages; (2) the number of the participant patients was not large, although it is one of the largest groups reported to date; (3) the allocation of the patients to the two regimens was only partially random; (4) the relatively low starting serum phosphate level in conjunction with the no vitamin D use means that the patients were not typical of most HD patients; (5) we did not obtain data on the patients’ bone metabolism markers.

In conclusion, our study showed that MgCO3 administered for a period of 6 months is an effective and inexpensive agent to control serum P levels in hemodialysis patients. Gastrointestinal disorders due to its use were minor, while its administration in combination with a low dialysate magnesium concentration reduces the risk of severe hypermagnesemia. Patients treated with MgCO3 had a mild suppression of PTH, an optimum regulation of Ca × P product, relatively low serum calcium and no episodes of hypercalcemia. We believe that this demonstration of the effectiveness of MgCO3 to bind phosphate warrants further investigation in a larger group of patients.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM, Ofsthum N, Lowrie EG, Chertow GM (2004) Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 15:2208–2218 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Drueke T, Foley RN (2006) Improving outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 105:S1–S4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Salusky IB (2006) A new era in phosphate binder therapy. What are the options? Kidney Int Suppl 105:S10–S15 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.O’Donovan R, Baldwin D, Hammer M, Moniz C, Parsons V (1980) Substitution of aluminium salts by magnesium salts in control of dialysis hyperphosphatemia. Lancet 1:880–882 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Delmez JA, Kelber J, Norword KY, Slatopolsky E (1996) Magnesium carbonate as a phosphate binder: a prospective, controlled, crossover study. Kidney Int 49:163–167 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Parsons V, Papapoulos SE, Weston MJ, Tomlinson S, O’Riordan JL (1980) The long-term effect of lowering dialysate magnesium on circulating parathyroid hormone in patients on regular haemodialysis therapy. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 93:455–460 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Shah GM, Winer RL, Cutler RE, Arief AI, Goodman WG, Lacher JW, Schoenfeld PY, Coburn JW, Horowitz AM (1987) Effects of a magnesium-free dialysate on magnesium metabolism during continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 10:268–275 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Roujouleh H, Lavaud S, Toupance O, Melin GP, Chanard G (1987) Magnesium hydroxide treatment of hyperphosphatemia in chronic hemodialysis patients with an aluminum overload. Nephrology 8:45–50 [PubMed]

- 9.Guillot AP, Hood VL, Runge CF, Gennari FJ (1982) The use of magnesium-containing in patients with end-stage renal disease on maintenance hemodialysis. Nephron 30:114–117 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Moriniere P, Vinatier I, Westeel PF, Cohemsolal M, Belbrik S, Abdulmassih Z, Hocine C, Marie A, Leflon P, Roche C (1988) Magnesium hydroxide as a complementary aluminium-free phosphate binder to moderate doses of oral calcium in uremic patients on chronic haemodialysis: lack of deleterious effect on bone mineralization. Nephrol Dial Transplant 3:651–656 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Daugirdas JT (1993) Second generation logarithmic estimates of single pool variable volume Kt/V: an analysis of error. J Am Soc Nephrol 4:1205–1213 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Spiegel DM, Farmer B, Chonhol M (2006) Magnesium carbonate is an effective phosphate binder. National Kidney Foundation, Spring Clinical Meeting 2006, Chicago [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Quinibi WY, Hootkins RE, McDowell LL, Meyer MS, Simon M, Garza RO, Pelham RW, Cleveland MV, Muenz LR, He DY, Nolan CR (2004) Treatment of hyperphosphatemia in hemodialysis patients: the Calcium Acetate Renagel Evaluation (CARE STUDY). Kidney Int 65:1914–1926 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Chertow GM, Burke SK, Raggi P, Treat to Goal Working Group (2002) Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 62:245–252 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Asmus HG, Braun J, Krause R et al. (2005) Two year comparison of sevelamer and calcium carbonate on cardiovascular calcification and bone density. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20:1653–1661 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Quinibi W, Moustafa M. Kessler P, Muenz L, Budoff M (2006) Coronary artery calcification in hemodialysis patients. Preliminary results from the Calcium Acetate Renagel Evaluation-2 (CARE-2) study. Poster presented at the 39th ASN Congress, San-Diego, CA

- 17.National Kidney Foundation (2003) K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease patients. Am J Kidney Dis 42[Suppl 3]:S1–S202 [PubMed]

- 18.Agus ZS, Moral M (1991) Modulation of cardiac ion channels by magnesium. Ainu Rev Physiol 53:299–307 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Truttmann AC, Farina R, Vizier RO, Niftier JM, Pfister R, Bianchetti MG (2002) Maintenance hemodialysis and circulating ionized magnesium. Nephron 92:616–621 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Saha H, Harmoinen A, Nisula M, Pasternack A (1998) Serum ionized versus total magnesium in patients with chronic renal disease. Nephron 80:149–152 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kelepouris E, Agus ZS (1998) Hypomagnesaemia: renal magnesium handling. Semin Nephrol 18:58–73 [PubMed]

- 22.Hutchison AJ (1997) Serum magnesium and end-stage renal disease. Perit Dial Int 17:327–329 [PubMed]

- 23.Mountokalakis TD (1990) Magnesium metabolism in chronic renal failure. Magnes Res 3:121–127 [PubMed]

- 24.Maier J (2003) Low magnesium and atherosclerosis: an evidence-based link. Mol Aspects Med 24:137–146 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Ueshima K (2005) Magnesium and ischemic heart disease: a review of epidemiological, experimental, and clinical evidences. Magnes Res 18:275–284 [PubMed]

- 26.Meema HE, Oreopoulos DG, Rapaport A (1987) Serum magnesium level and calcification in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 32:388–394 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Izawa H, Imura M, Kuroda M, Takeda R (1974) Effect of magnesium on secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic hemodialysis: a case with soft tissue calcification improved by high Mg dialysate. Calcif Tissue Res 15:162 [PubMed]

- 28.Tzanakis I, Pras A, Kounali D, Mamali V, Kartsonakis V, Mayopoulou-Symvoulidou D, Kallivretakis N (1987) Mitral annular calcification in hemodialysis patients: a possible protective role of magnesium. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12:2036–2037 [PubMed]

- 29.Tzanakis I, Virvidakis K, Tsomi A, Mantakas E, Girousis N, Karefylakis N, Papadaki A, Kallivretakis N, Mountokalakis T (2004) Intra- and extracellular magnesium levels and atheromatosis in haemodialysis patients. Magnes Res 17:102–108 [PubMed]

- 30.Tzanakis I, Tsomi A, Papadaki A, Mantakas E, Kallivretakis N (2006) The higher intracellular magnesium, the better long-term survival on hemodialysis. Poster presented at the 39th ASN Congress, San Diego, CA

- 31.Wei M, Esbaei K, Bargman J, Oreopoulos D (2006) Relationship between serum magnesium, parathyroid hormone, and vascular calcification in patients on dialysis: a literature review. Perit Dial Int 26:366–373 [PubMed]