Abstract

Repeat proteins are widespread in nature, with many of them functioning as binding molecules in protein–protein recognition. Their simple structural architecture is used in biotechnology for generating proteins with high affinities to target proteins. Recent folding studies of ankyrin repeat (AR) proteins revealed a new mechanism of protein folding. The formation of an intermediate state is rate limiting in the folding reaction, suggesting a scaffold function of this transient state for intrinsically less stable ARs. To investigate a possible common mechanism of AR folding, we studied the structure and folding of a new thermophilic AR protein (tANK) identified in the archaeon Thermoplasma volcanium. The x-ray structure of the evolutionary much older tANK revealed high homology to the human CDK inhibitor p19INK4d, whose sequence was used for homology search. As for p19INK4d, equilibrium and kinetic folding analyses classify tANK to the family of sequential three-state folding proteins, with an unusual fast equilibrium between native and intermediate state. Under equilibrium conditions, the intermediate can be populated to >90%, allowing characterization on a residue-by-residue level using NMR spectroscopy. These data clearly show that the three C-terminal ARs are natively folded in the intermediate state, whereas native cross-peaks for the rest of the molecule are missing. Therefore, the formation of a stable folding unit consisting of three ARs is the necessary rate-limiting step before AR 1 and 2 can assemble to form the native state.

Keywords: folding kinetics, protein folding, NMR, protein structure, Thermoplasma volcanium

Ankyrin repeat (AR) proteins are ubiquitious and involved in numerous fundamental physiological processes (1). A common feature of repeat proteins from all families is their modular architecture of homologous structural elements forming a scaffold for specific and tight molecular interactions. This property has been applied in biotechnology to generate AR proteins with high affinities for target proteins (2). The AR consists of 33 amino acids that form a loop and a β-turn followed by two antiparallel α-helices connected by a tight turn. Up to 29 repeats can be found in a single protein, but usually four to six repeats stack onto each other to form an elongated structure with a continuous hydrophobic core and a large solvent accessible surface (3–6). Unlike the packing of globular protein domains, the linear arrangement of the repeat modules in AR proteins implies that local, regularly repeating packing interactions are very important and may dominate the thermodynamic stability and the folding mechanism. AR proteins are therefore expected to fold in a fast, modular, multistate reaction controlled by short-range interactions. Interestingly, folding of naturally occurring AR proteins is much slower than expected from the low contact order and shows almost exclusively two-state behavior under equilibrium conditions (7–16). However, kinetic and equilibrium analysis of the folding of CDK inhibitor p19INK4d (17, 18) and Notch ankyrin domain (19), revealed a surprising folding mechanism including the formation of an intermediate state as rate limiting step. Partially folded intermediate states found on the folding pathway of small globular domains usually form much faster than the rate limiting step of folding. Thus, the intermediate state of an AR protein may act as a scaffold, requiring initial folding before zipping up of the less stable repeats in a fast reaction to the native state.

Folding studies on naturally occuring AR proteins have until now focused only on eukaryotic proteins. To test the validity of a possible common mechanism of AR folding, we performed a Blast search with the p19INK4d sequence as template on evolutionary much older archaeal organisms. A new protein of similar length and with <25% sequence identity to p19INK4d was identified in Thermoplasma volcanium (20). The herein determined structure by x-ray crystallography confirmed that this archaeal AR protein (tANK) folds into five sequentially arranged ARs with an additional helix at the N terminus. Equilibrium and kinetic folding analyses of this protein by fluorescence and CD spectroscopy revealed a sequential three-state folding mechanism with the expected unusual fast equilibrium between the native and intermediate state. Compared with p19INK4d and the Notch ankyrin domain, the intermediate state of tANK can be populated to 90% at equilibrium, making high-resolution studies possible. GdmCl induced equilibrium unfolding transitions monitored by NMR showed that the amide protons of AR 3–5 in the intermediate still resonate at native chemical shifts whereas the N-terminal AR are mainly unfolded. Limited proteolysis data confirmed AR 3–5 as the most stable part of the protein.

Results and Discussion

X-Ray Structure of tANK.

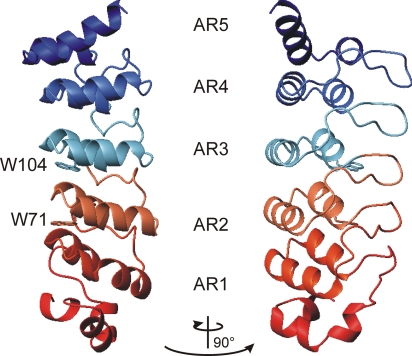

To compare protein folding data derived from human AR proteins with thermophilic AR proteins, we performed a Blast search against the archaean database using the human p19INK4d sequence as template. A putative AR protein (tANK) was identified in Thermoplasma volcanium sharing <25% sequence identity with the human p19INK4d protein [see supporting information (SI) Fig. 7]. The top hits in a second Blast search with the sequence of tANK in the nonredundant protein database only comprised archaeal homologs. Therefore, a horizontal gene transfer seems to be unlikely. The crystal structure of this protein was solved to 1.65 Å resolution, confirming the expected five-membered AR fold. Structural refinement procedures and statistics are given in the supporting information. Compared with p19INK4d (21, 22), the thermophilic protein harbours an extension of 23 aa at the N terminus which forms an additional helix (Fig. 1). The backbone rmsd for AR 3–5 between the mesophilic and thermophilic protein was <1.5 Å, indicating the high conservation of this structure element in evolution.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the structure of the thermophilic ankyrin repeat protein tANK (Protein Data Base ID code 2RFM). Five ARs (AR1–AR5), each comprising a loop, a β-turn, and two sequential α-helices form the elongated structure, extended by an α-helical N terminus are shown. Side chains of the wild-type fluorescence probes Trp-71 and Trp-104 are indicated as sticks. The figure was created by using MOLMOL (34).

GdmCl-Induced Unfolding Involves the Formation of a Partially Structured Intermediate.

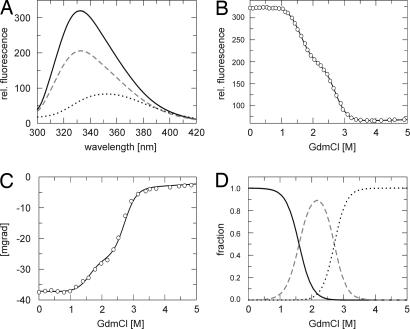

The stability of tANK was monitored by fluorescence- and CD spectroscopy in the presence of various amounts of GdmCl. Trp-71 and Trp-104 located in AR 2 and 3 (Fig. 1) proved excellent probes to follow the transition curve. Upon unfolding, the fluorescence of the native protein N is strongly quenched and the maximum of the spectrum is shifted to higher wavelength (333 nm → 355 nm). At medium concentrations of GdmCl, however, an intermediate state I gets populated, which shows a quenched maximum still at 333 nm (Fig. 2A). To follow the α-helical content of the protein upon GdmCl unfolding, far-UV CD at 222 nm was used as a second probe. At medium concentrations of GdmCl (2 M) one third of the native CD signal is lost, indicating the unfolding of some secondary structure elements (Fig. 2C). A combined analysis of GdmCl-induced unfolding curves monitored by fluorescence (Fig. 2B) and CD according to a three-state model revealed a global stability of ΔGu = 52.6 ± 1.8 kJ/mol for tANK; 18.5 ± 1.0 kJ/mol count for the N to I transition, whereas the intermediate state has a stability of 34.1 ± 1.5 kJ/mol relative to U. Resulting m values are 11.6 ± 0.7 kJ·mol−1 M−1 and 12.6 ± 0.6 kJ·mol−1 M−1 for the first and second transitions, respectively. Calculated populations of N, I, and the unfolded state (U) according to these biophysical parameters show that I is populated to an extent of 90% under equilibrium conditions at ≈2.1 M GdmCl (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

GdmCl-induced unfolding of tANK monitored by fluorescence and CD spectroscopy. (A) Fluorescence spectra of tANK at 0 M (black line), 2 M (broken gray line) and 5 M (dotted black line) GdmCl after excitation at 280 nm. GdmCl induced unfolding transitions monitored by fluorescence at 335 nm (B) and CD at 222.6 nm (C). Solid lines in B and C represent the least square fit of a three-state model (see Materials and Methods for details). (D) Calculated equilibrium populations of the native N (black line), intermediate I (broken gray line), and unfolded state U (dotted black line) according to the global analysis of fluorescence and CD equilibrium data.

Analytical ultracentrifugation of tANK indicates that the intermediate state is monomeric: the sedimentation equilibration at 1.95 M GdmCl gave an Mr of 22.7 ± 1.6 kDa, which is consistent with the mass of one polypeptide chain (see SI Fig. 8). However, at this GdmCl concentration, a 1 mM protein sample forms fibrils after several days (see SI Fig. 11). This is consistent with the idea that populated but destabilized folding intermediates are prone to the formation of ordered aggregates (23).

Folding Kinetics.

Unfolding and refolding kinetics of tANK were measured by stopped-flow fluorescence spectroscopy. Unfolding under fully denaturing conditions (>3 M GdmCl) is fast and best described by a biphasic process with rate constants that differ by at least a factor of 20 (Fig. 3A). Each unfolding reaction contributes to 50% of the whole unfolding amplitude (Fig. 3C). Below 3 M GdmCl, however, the amplitude for the slow unfolding reaction decreases faster compared with the amplitude for the fast unfolding reaction, indicating the population of the intermediate state. At 2 M GdmCl, for example, where I is the dominant species, the fast unfolding phase accounts for 90% of the amplitude. The refolding reaction starting from fully unfolded protein is best described by three exponential functions with folding rates that differ by more than a factor of 10 (Fig. 3B). The fast reaction adds to >85% of the amplitude, whereas the two slow reactions account for <10% each (Fig. 3D). Nevertheless, at low GdmCl concentrations, no fast refolding phase in the range between 100 s−1 and 1,000 s−1 was observed in this experiment. Note that the entire refolding amplitude is detectable during the refolding reaction, evident from the start and end point analysis of the kinetics (Fig. 3F). Because of the latter observation, burst phase intermediates or problems in reversibility can be excluded. These findings can be explained by the sequential folding mechanism U ⇌ I ⇌ N already observed for p19INK4d and the Notch ankyrin domain. The formation of the intermediate state is rate limiting during the refolding reaction. Kinetic experiments using single mixing can only directly monitor reactions that occur before the rate limiting step if the rates differ by >5-fold. This explains the absence of a very fast refolding phase between 0 and 1 M GdmCl (Fig. 3E). To confirm this assumption, unfolding and refolding reactions were initiated from the intermediate state. Protein was incubated at 1.7 M GdmCl (45% native, 55% I, 0% U) and refolded to native conditions between 0.4 and 1.6 M GdmCl. All refolding kinetics were very fast and followed a single exponential function (Fig. 3B Inset). These rates filled the missing gap of the Chevron plot (open gray symbols in Fig. 3E) and thereby assigned the fast folding reaction to the transition between the native and intermediate state. Below 0.5 M GdmCl, the rates exceed the limits of conventional stopped-flow techniques.

Fig. 3.

Single mixing unfolding and refolding kinetics of tANK detected by stopped flow fluorescence. (A and B) Experimental data are plotted in black and fits in gray. (A) Unfolding was initiated by a rapid change from 0 M to 4 M GdmCl and can be best fitted by a double exponential function. (B) Refolding was initiated by rapid dilution from 5 M to 0.9 M GdmCl and follows a sum of three exponentials. Refolding (A Inset) and unfolding traces (B Inset) starting from GdmCl concentrations where the intermediate is highly populated (1.7 M GdmCl for refolding and 2.6 M GdmCl for unfolding) can be best described by a single exponential function. Amplitudes of refolding (C) and unfolding (D) phases, calculated as a percentage of the total fluorescence change between the native and unfolded state: filled diamond, slow phase; filled circle, fast phase of unfolding; the amplitude of the refolding kinetics is dominated by one phase (open diamonds) and two minor phases (open hexagon, slow; open inverted triangle, very slow) with <10% of the whole amplitude are detectable. (E) GdmCl dependence of apparent folding rates of tANK monitored at 15°C, pH 7.4. Filled symbols indicate unfolding experiments, open symbols indicate refolding experiments. Gray symbols represent folding rates that result from unfolding and refolding kinetics starting from the intermediate state. (F) Start and end point analysis of the kinetic experiments. End points of unfolding (filled triangle) and refolding (filled circle) reactions follow fluorescence equilibrium data (Fig. 2B). Start point (open circle and triangle) analysis reveal that there is no obvious burst-phase observable.

Unfolding reactions at high GdmCl concentration with protein preincubated at 2.6 M GdmCl (0% native, 55% I, 45% U) follow a single exponential decay (Fig. 3A Inset). These unfolding rates (closed gray symbols in Fig. 3E) match with slow unfolding rates observed in unfolding experiments starting from the native state. Therefore, we assign these rates to the slow reaction between the intermediate and the unfolded state. These data clearly confirm the early observations seen for p19INK4d and the Notch ankyrin domain, namely that the formation of the intermediate state is indeed the rate limiting step in the folding reaction.

Although logarithms of the fastest un-/folding rates show a linear dependence of the GdmCl concentration, a pronounced kink in the unfolding and refolding limb of the U ↔ I transition is visible. These “roll overs” are not caused by kinetic coupling of the observed folding rates, because the refolding and unfolding rates differ by more than a factor of 10. Furthermore, unfolding rates derived from unfolding reactions initiated from the intermediate state also result in a downward curvature of the unfolding limb. Curvatures in the refolding and unfolding limbs of the Chevron plot have been observed for various proteins (24, 25). These nonlinearities are often interpreted in terms of a broad energy barrier, where the addition of denaturant can cause a movement of the transition state which results in kinetic anomalies (25). Alternatively, the existence of additional high energy intermediates in unfolding and refolding reactions can explain these observations (26).

In contrast to the fast reactions, the two minor phases detected in refolding reactions starting from the unfolded state do not show a significant dependence on GdmCl concentration (Fig. 3E). None of these two folding reactions is detectable when refolding is initiated from the intermediate state, indicating that these reactions originate from heterogeneity in the unfolded state. The temperature dependence of the slowest refolding rate yields in an activation energy of 78.5 ± 3 kJ/mol, typical for prolyl cis/trans isomerization reactions (27) (see SI Fig. 10). This assumption could be confirmed by a 5-fold acceleration of this folding phase in the presence of 10% of the prolyl isomerase SlyD from Thermus thermophilus (C.L., unpublished results, data not shown). It should be noted that all prolyl peptide bonds of the native state are in the trans conformation according to the crystal structure of tANK.

The second slow folding rate has a GdmCl independent time constant of 1 s at 15°C. Although the amplitude for this reaction is quite small (<5%), the refolding rate could be accurately determined due to the large change in fluorescence between the native and the unfolded state. The activation energy for this reaction was determined to 47.5 ± 3 kJ/mol (see SI Fig. 10). Compared with literature data (28), this suggests that the origin of this folding rate is caused by the isomerization of nonprolyl cis peptide bonds in the unfolded state.

GdmCl Folding Transition Monitored by NMR.

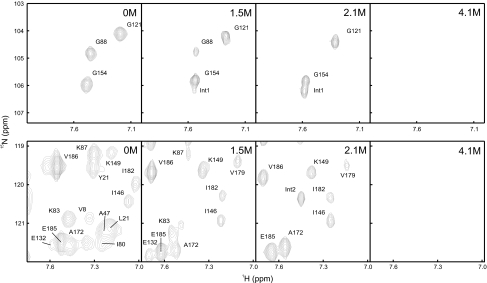

As a result of the high population of the intermediate state under equilibrium conditions, it was possible to further characterize this state by NMR spectroscopy. To this end, >83% of the backbone amide protons of the native state were assigned using standard 3D experiments (see SI Fig. 9). The GdmCl induced transition of tANK was followed by a series of 19 2D 15N-TROSY-HSQC spectra recorded at various GdmCl concentrations. Long incubation times of the NMR samples at medium concentrations of GdmCl resulted in fibril formation (see above). Thus for each datapoint a fresh sample was prepared in the transition region of the GdmCl transition. 66 out of 185 possible native amide cross-peaks could be followed during the entire transition without overlap of cross-peaks from I and U. Fig. 4 depicts two sections from these 15N-TROSY-HSQCs, where cross-peaks of the native state disappear at low (e.g., G88) or at high (e.g., G121) GdmCl concentrations. Some cross-peaks appear only at intermediate GdmCl concentrations (e.g., Int1 and Int2). It should be noted that the selected sections are outside the range of cross-peaks of the unfolded state and that the chemical exchange between the three states is slow compared with chemical shift time scale at GdmCl concentrations, were U, I, and N are highly populated.

Fig. 4.

Sections of 15N-TROSY-HSQC spectra of tANK show the disappearance of native cross-peaks at low (e.g., G88) and high (e.g., G121) denaturation concentrations. Transiently appearing cross-peaks of the intermediate state are labeled with Int. Residues of AR 3–5 are still present at 2.1 M GdmCl, where the intermediate state is maximally populated, whereas signals of the N-terminal part are missing. This indicates that AR 3–5 remain folded in the intermediate state.

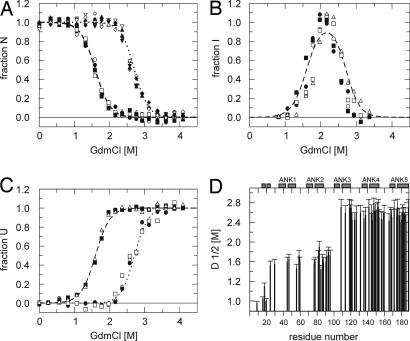

For quantitative analysis, the volume of each cross-peak present at 0 M GdmCl was plotted against the GdmCl concentration, resulting in 66 unfolding transition curves (examples are shown in Fig. 5A). They can be grouped into two classes, following the two transitions seen from fluorescence and CD data (Fig. 2). Unfolding curves derived from N-terminal repeats show a transition midpoint of ≈1.6 M GdmCl (Fig. 5D). These cross-peaks with native chemical shifts vanished at 2.1 M GdmCl, where the intermediate state is maximally populated. In contrast, residues of AR 3–5 still show native chemical shifts at 2.1 M GdmCl and also unfold cooperatively with a transition midpoint of ≈2.6 M GdmCl (Fig. 5D). Detailed analysis allows assignment of the two transitions observed by optical methods to the respective residues in tANK. Amide protons of the first ARs follow the decay of the native population as derived from fluorescence and CD data. However, residues from AR 3–5 can be described by the sum of the native and intermediate population. This demonstrates that in the intermediate state, amide protons of AR 3–5 still show native chemical shifts whereas resonances of residues from AR 1 and 2 show nonnative chemical shifts. Moreover, the build-up of 40 unfolded cross-peaks could be followed over the entire GdmCl range (examples shown in Fig. 5C). Interestingly, they show a corresponding pattern, where some are already maximally populated in the intermediate state, suggesting some N-terminal residues sense a completely unfolded chemical environment. The larger fraction of unfolded peaks follows the decay of the intermediate state. Furthermore, 12 additional peaks could be directly assigned to the intermediate state far off random coil shifts (e.g., Int1 in Fig. 4), which arise during the first transition. They get fully populated at 2.1 M GdmCl and then decay at higher GdmCl concentrations. The course of additional intermediate signals with GdmCl concentration (Fig. 5B) agrees well with the intermediate population calculated from the fluorescence data (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 5.

GdmCl induced unfolding transitions of tANK monitored by NMR. 15N-TROSY-HSQC spectra were recorded between 0 and 4.2 M GdmCl. (A) Normalized cross-peak volumes of backbone amides assigned to the native state at 0 M GdmCl. E45, D60, L78, G88, and V91 of AR 1–2 follow the decay of the native state population derived from the fluorescence and CD data (broken line). G109, E119, G142, L153, and A189 of AR 3–5 follow the sum of the native state and intermediate state population derived from the fluorescence and CD data (dotted lines). (B) Additional, transient cross-peaks which do not heavily overlap with peaks from the native or denatured state agree with the intermediate population (broken line) resulting from fluorescence and CD data. (C) The build-up of cross-peak volumes of the denatured state was monitored over the entire GdmCl range. Some cross-peaks are already maximal at intermediate GdmCl concentrations (2.1 M GdmCl), whereas the volumes of other cross-peaks increased with unfolding of the intermediate state. The data suggest that some residues experience a denatured like environment in the intermediate state. (D) Midpoints of denaturation profiles of 66 of 185 possible amide cross-peaks show that the two N-terminal AR are by 1 M GdmCl less stable compared with C-terminal three repeats.

Transition curves resulting from the N-terminal helical extension (residues 1–24) of tANK show much lower midpoints compared with the rest of the molecule (Fig. 5D). These data match with limited proteolysis data (see SI Table 2), which showed a rapid degradation of the N-terminal 25 residues. Longer incubation times, however, lead to a stable 10 kDa fragment as judged by SDS page, identified as AR 3–5 by mass spectroscopy. The proteolysis data therefore verify the graded thermodynamic stability of tANK found from GdmCl induced unfolding transitions.

Sequential Folding Mechanism of tANK.

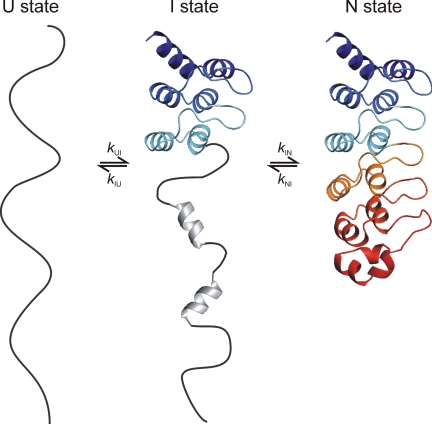

The biophysical data presented here suggest the simplified model for folding of tANK outlined in Fig. 6. Folding and unfolding of tANK is a sequential, discrete process via an on-pathway intermediate with a highly cooperative transition between the consecutive steps. The partially folded state contains folded AR 3–5. The N-terminal part of the intermediate might contain some residual secondary structure indicated by the CD detected unfolding transition (Fig. 2C) and the good dispersion of NMR chemical shifts from some residues of this region (Fig. 4). The formation of this intermediate state is rate limiting for the refolding reaction, which suggests a scaffold function for AR 3–5. Interestingly, sequences of AR 3–5 of tANK and p19INK4d show a high homology to the consensus AR sequence (29, 30). Designed AR proteins based on this consensus sequence are known to be significantly more stable compared with naturally occurring AR proteins (29). Therefore we propose that ARs with the highest local stability (usually two to three repeats) form the initiation site of the folding reaction.

Fig. 6.

Simplified folding model of tANK. The protein folds via an on-pathway intermediate in which the two N-terminal repeats are unfolded and the three C-terminal repeats are natively folded. Additional NMR cross-peaks of the intermediate state, which do not show a random coil chemical shift, and CD data suggest that there is some residual secondary structure in AR 1 and 2.

Materials and Methods

Gene Construction, Protein Expression and Purification.

A living culture of Thermoplasma volcanium (DSM 4300) was purchased from DSMZ (Deutsche Sammlung von Mirkroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany). The organism was grown in Thermoplasma volcanium medium (medium 398) under anaerobic conditions at 60°C for 2 weeks. Genomic DNA was prepared using the Wizard DNA Purification System (Promega). The gene for the thermophilic AR protein was amplified by using flanking primers and cloned into a pet28c vector. The gene sequence was confirmed by automated DNA sequencing. Protein was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) and purified from soluble material. Cells were resuspended in IMAC binding buffer (50 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM Imidazole, pH 8.0) and lysed by sonication. Protein was eluted from the IMAC-column by step elution with 250 mM imidazole, pooled, and dialyzed against Thrombin cleavage buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). The His-tag was cleaved off by adding 2 units of thrombin per mg of protein at 4°C overnight. Protein was further purified by an additional IMAC-column and gel filtration (superdex 75) to virtual homogeneity in the presence of reducing agent. Protein was concentrated and stored at −80°C. Identity of the protein was verified by electrospray mass spectrometry. Perdeuterated, isotopically labeled 2H, 15N, 13C-NMR-samples were produced using M9 minimal media made up with 2H2O and 13C-glucose as carbon source and 15NH4Cl as nitrogen source, respectively, and supplemented with vitamin mix.

Crystallization.

Protein was rebuffered in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 and concentrated to 50 mg/ml. Crystals were grown by hanging drop vapor diffusion method at 13°C in 24-well crystallization plates. The drops contained 2 μl of protein and 2 μl of reservoir solution (20% glycerol, 2 M ammoniumsulfate, 1% 1,3 butanediol) with 0.5 ml of reservoir solution in each well. Crystals grew within 4 weeks. The structure was determined in house using the anomalous signal of iodine (Single-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion or SAD), after soaking of the crystal in crystallization buffer containing 50 mM KI for 20 h before measurement.

X-Ray Diffraction and Structural Refinement.

X-ray diffraction and structural refinement are described in SI Text.

CD and Fluorescence.

GdmCl ultrapure was purchased from MP Biomedicals, LLC (Eschwege, Germany) and all other chemicals from Merck. All experiments were performed at 15°C in the presence of 0.1 mM TCEP. Far-UV CD GdmCl-induced unfolding transitions of the AR protein were monitored at 222.6 nm for 1–3 μM protein solutions with varying GdmCl concentrations and 4–6 h incubation time to reach equilibrium with a JASCO J600A spectropolarimeter. GdmCl transitions monitored by fluorescence were recorded with a JASCO FP6500 fluorescence spectrometer. A fluorescence spectrum was recorded for each data point from 300 to 420 nm after excitation at 280 nm. All experimental data were analyzed according to a three-state model by nonlinear least-squares fit with proportional weighting to obtain the Gibbs free energy of denaturation ΔG as a function of the GdmCl concentration (31). Fluorescence transition curves detected at various wavelength were analyzed together with CD data using the program Scientist (MicroMath).

Kinetics.

Kinetic experiments were performed using an Applied Photophysics SX-17MV and SX-20MV stopped-flow instrument at 15°C. An excitation wavelength of 280 nm was used, and emission was monitored at wavelengths above 305 nm using cut-off filters. Unfolding experiments were performed by mixing native protein or the intermediate state (0 or 1.7 M GdmCl) in 20 mM Na-phosphate (pH 7.4) with 5 or 10 volumes of GdmCl containing the same buffer. Refolding was initiated by 11- or 6-fold dilution of unfolded protein or the intermediate state (5 or 2.6 M GdmCl). The final protein concentration was 1–3 μM. Data collected from at least 4–8 scans were averaged and fitted using Grafit 5 (Erithacus). Unfolding traces were fitted to two exponential functions. Refolding traces were fitted to a sum of three exponential functions. The slowest refolding phase was also determined by manual mixing in the presence and absence of the prolyl isomerase Thermus thermophilus SlyD.

NMR.

All NMR spectra were acquired with a Bruker Avance 800 and 900 spectrometer in 20 mM Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 10% 2H2O. For backbone assignment trHNCA, trHNCACB and trHN(CO)CACB were measured with a 1.2 mM 15N/13C/2D labeled sample at 25°C. The assignment was transferred by a series of 15N-TROSY-HSQC at different temperatures to 15°C. The GdmCl transition was performed with 15N labeled samples at 15°C using 15N-TROSY-HSQC. Native protein was diluted with 8 M GdmCl stock solution to the desired GdmCl concentration. For each data point in the transition region (1.5–3 M GdmCl), a fresh sample of 500 μM protein was prepared before use to avoid fibril formation (see SI Fig. 11). Signal intensities of all spectra were referenced according to the protein concentration in the respective sample. Spectra were processed using NMRpipe (32) and analyzed with NMRView (33). Signal intensities of the native, intermediate, and unfolded population were used for analysis of the GdmCl equilibrium transition and compared with populations resulting from fluorescence and CD measurements.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank Paul Rösch and Hartmut Oschkinat for NMR spectrometer time at 800 and 900 MHz, Franz Xaver Schmid for use of equipment, Peter Schmieder (North-East NMR center, FMP Berlin) for measurement of the assignment spectra, Rolf Sachs and Gerd Hause for electron microscopy, Heinrich Sticht for BlastP searches, and Mirko Sackewitz for helpful discussions. This research was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ba 1821/3–1,2 and GRK 1026 “Conformational transitions in macromolecular interactions”) and the excellence initiative of the state Sachsen-Anhalt.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2RFM).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0710657105/DC1.

References

- 1.Bork P. Proteins. 1993;17:363–374. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binz HK, Amstutz P, Kohl A, Stumpp MT, Briand C, Forrer P, Grütter MG, Plückthun A. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:575–582. doi: 10.1038/nbt962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosavi LK, Cammett TJ, Desrosiers DC, Peng ZY. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1435–1448. doi: 10.1110/ps.03554604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Main ER, Lowe AR, Mochrie SG, Jackson SE, Regan L. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorina S, Pavletich NP. Science. 1996;274:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard J, Bechstedt S. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R224–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plaxco KW, Simons KT, Baker D. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:985–994. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowe AR, Itzhaki LS. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zweifel ME, Barrick D. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14357–14367. doi: 10.1021/bi011436+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devi VS, Binz HK, Stumpp MT, Plückthun A, Bosshard HR, Jelesarov I. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2864–2870. doi: 10.1110/ps.04935704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang KS, Guralnick BJ, Wang WK, Fersht AR, Itzhaki LS. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1869–1886. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosavi LK, Williams S, Peng ZY. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:165–170. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Street TO, Bradley CM, Barrick D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4907–4912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608756104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan C, Li J, Selby TL, Byeon IJ, Tsai MD. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:201–211. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mello CC, Barrick D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14102–14107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403386101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kloss E, Courtemanche N, Barrick D. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;469:83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Löw C, Weininger U, Zeeb M, Zhang W, Laue ED, Schmid FX, Balbach J. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeeb M, Rösner H, Zeslawski W, Canet D, Holak TA, Balbach J. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:447–457. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mello CC, Bradley CM, Tripp KW, Barrick D. J Mol Biol. 2005;352:266–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawashima T, Amano N, Koike H, Makino S, Higuchi S, Kawashima-Ohya Y, Watanabe K, Yamazaki M, Kanehori K, Kawamoto T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14257–14262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumgartner R, Fernandez-Catalan C, Winoto A, Huber R, Engh RA, Holak TA. Structure. 1998;6:1279–1290. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brotherton DH, Dhanaraj V, Wick S, Brizuela L, Domaille PJ, Volyanik E, Xu X, Parisini E, Smith BO, Archer SJ, et al. Nature. 1998;395:244–250. doi: 10.1038/26164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobson CM. Nature. 2003;426:884–890. doi: 10.1038/nature02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fersht AR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14121–14126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260502597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otzen DE, Kristensen O, Proctor M, Oliveberg M. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6499–6511. doi: 10.1021/bi982819j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez IE, Kiefhaber T. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balbach J, Schmid FX. In: Mechanisms of Protein Folding. Pain RH, editor. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2000. pp. 212–237. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pappenberger G, Aygun H, Engels JW, Reimer U, Fischer G, Kiefhaber T. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:452–458. doi: 10.1038/87624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohl A, Binz HK, Forrer P, Stumpp MT, Plückthun A, Grütter MG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1700–1705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337680100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosavi LK, Minor DL, Jr, Peng ZY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16029–16034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252537899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hecky J, Müller KM. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12640–12654. doi: 10.1021/bi0501885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson BA, Blevins RA. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.