Abstract

The cell walls of mycobacteria form an exceptional permeability barrier, and they are essential for virulence. They contain extractable lipids and long-chain mycolic acids that are covalently linked to peptidoglycan via an arabinogalactan network. The lipids were thought to form an asymmetrical bilayer of considerable thickness, but this could never be proven directly by microscopy or other means. Cryo-electron tomography of unperturbed or detergent-treated cells of Mycobacterium smegmatis embedded in vitreous ice now reveals the native organization of the cell envelope and its delineation into several distinct layers. The 3D data and the investigation of ultrathin frozen-hydrated cryosections of M. smegmatis, Myobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin, and Corynebacterium glutamicum identified the outermost layer as a morphologically symmetrical lipid bilayer. The structure of the mycobacterial outer membrane necessitates considerable revision of the current view of its architecture. Conceivable models are proposed and discussed. These results are crucial for the investigation and understanding of transport processes across the mycobacterial cell wall, and they are of particular medical relevance in the case of pathogenic mycobacteria.

Keywords: bacterial cell wall, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium smegmatis, mycolic acid layer

Mycobacteria have evolved a complex cell wall, comprising a peptidoglycan-arabinogalactan polymer with covalently bound mycolic acids of considerable size (up to 90 carbon atoms), a variety of extractable lipids, and pore-forming proteins (1–3). The cell wall provides an extraordinarily efficient permeability barrier to noxious compounds and contributes to the high intrinsic resistance of mycobacteria to many drugs (4). Because of the paramount medical importance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the ultrastructure of mycobacterial cell envelopes has been intensively studied during recent decades. The current view of the cell wall architecture is essentially based on a model suggested by Minnikin (5). He proposed that the covalently bound mycolic acids form the inner leaflet of an asymmetrical bilayer. Other lipids extractable by organic solvents were thought to form the outer leaflet, either intercalating with the mycolates (5, 6) or forming a more clearly defined interlayer plane (7). Elegant x-ray diffraction studies proved that the mycolic acids are oriented parallel to each other and perpendicular to the plane of the cell envelope (8). Furthermore, freeze–fracture studies showed a second fracture plane in electron micrographs (9), indicating the existence of a hydrophobic bilayer structure external to that of the cytoplasmic membrane. Mutants or treatments affecting mycolic acid biosynthesis and the production of extractable lipids resulted in an increase of cell wall permeability in various mycobacteria and related microorganisms (10–12) and a drastic decrease of virulence, underlining the importance of the integrity of the cell wall for intracellular survival of M. tuberculosis (1).

However, this model also faced criticism, mainly because electron microscopy of mycobacteria, particularly thin sections thereof, never provided clear evidence for an outer lipid bilayer (2). An electron-transparent zone in stained thin sections (13, 14), which was shown to comprise lipids (i.e., predominantly mycolic acids) (15), was covered by a stained outer layer thought to represent carbohydrates, peptides, and other lipids (4). The whole structure is of considerable thickness, which poses the problem of understanding how the Mycobacterium smegmatis porin MspA with its comparatively much shorter hydrophobic surface is inserted (16–18).

In this study, we reinvestigated the cell wall structure of M. smegmatis, Myobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin, and Corynebacterium glutamicum by means of electron microscopical cryotechniques. Cryo-electron tomography (CET; ref. 19) of intact mycobacteria in a close-to-life state and vitreous cryosections (20) of unfixed and unstained cells now reveal the mycobacterial outer membrane in its natural context.

Results

CET Reveals the Native Architecture of Bacterial Cell Envelopes.

The structure of bacterial cell walls as determined by electron microscopy of conventional ultrathin sections is often affected by chemical fixation, dehydration, staining, and resin embedding. We investigated the cell envelope architecture in M. smegmatis mc2155, M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin, and, as a control, in Escherichia coli DH5α, with frozen-hydrated and otherwise untreated intact cells by CET. Fig. 1A shows an electron microscope projection of M. bovis imaged with subcritical electron dose conditions and liquid nitrogen cooling. The major cell envelope layers are discernible, and they are clearly recovered in the x–y slices extracted from the tomograms after denoising (Fig. 1B). To evaluate the structural preservation of the cell wall in CET, we chose E. coli as a reference organism. The location of the outer membrane close to the peptidoglycan (distance ≈7.5 nm; Fig. 1C) and the width of the periplasm (≈16 nm) are consistent with the structure of periplasmic protein complexes such as Braun's lipoprotein, the flagellar basal body, and the TolC-AcrB assembly that serve as molecular rulers [for details, see supporting information (SI) Table 1]. We interpret this as evidence for accurate preservation of the native structure of the cell envelope in CET.

Fig. 1.

CET of M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (A, B, D), M. smegmatis (E), and E. coli (C). (A) Intact cell rapidly frozen (vitrified) in growth medium and imaged by using low-dose conditions at liquid nitrogen temperature. Black dots represent gold markers. (B–E) Calculated x–y slices extracted from subvolumes of the three-dimensionally reconstructed cells and corresponding density profiles of the cell envelopes. The profiles were calculated by averaging cross-sections of the cell envelopes along the x–y direction in 20 independent slices. A total of 10,000 cross-sections for the mycobacteria and 8,000 for E. coli were aligned by cross-correlation before averaging. The fitted Gaussian profiles in C (dashed curves) indicate the positions of the peptidoglycan (PG) and the outer membrane (OM). (D and E) Subtomograms recorded at nominal −6-μm defocus and reconstructed without noise reduction. CM, cytoplasmic membrane; L1 and L2, periplasmic layers; MOM, mycobacterial outer membrane. (Scale bars: A, 250 nm; B and C, 100 nm; D and E, 50 nm.)

M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin possesses a multilayered cell envelope structure (Fig. 1 A and B). The inner layer represents the cytoplasmic membrane, and the outer layer, the mycobacterial outer membrane (see below). The layers L1 and L2 cannot be assigned according to structural appearance alone. They likely represent structures related to the peptidoglycan–arabinogalactan–mycolate network visualized in their natural arrangement within the cell wall (SI Table 2).

The Outer Layer Is Revealed as a Lipid Bilayer in Cryo-Electron Tomograms.

In the case of intact cells, membranes are not usually resolved as lipid bilayers in CET because of cell thickness, the limited number of projections, and the focus conditions. To clarify the membrane structure further, we adapted the focus conditions for data recording (see Materials and Methods) and analyzed the tomograms to exploit the full resolution available. The x–y slices and the averaged density profiles in Fig. 1 D and E now clearly reveal the bilayer structure of the cytoplasmic membrane with an apparent total thickness of ≈7 nm. Concomitantly, the fine structure of the outer membrane of M. bovis and M. smegmatis is also rendered visible as a bilayer. It is ≈8 nm thick, and thus only 15% thicker than the cytoplasmic membrane. We use the term mycobacterial outer membrane to distinguish the structure from the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria.

Further, M. smegmatis cells were incubated with 1% octyl β-glucoside before freezing to probe the nature of the bilayer. After treatment and resuspension in detergent-free buffer, the cells became extremely hydrophobic and aggregated strongly. This phenomenon is consistent with the removal of lipids that expose a hydrophilic head group, such as polar glycolipids and glycopeptidolipids, and the exposure of lipids with hydrophobic ends, such as the covalently bound mycolic acids. Cells that could be resuspended were virtually intact and exhibited limited detergent effects, as observed by CET. Similar effects have never been found in untreated cells. Fig. 2A, E, and F shows an undisturbed cell wall region comprising four cell envelope layers similar to the architecture of untreated M. smegmatis (Fig. 1), as well as the bilayer structure of the mycobacterial outer membrane. The lipidic nature of the bilayer is demonstrated by the detergent effects, which disturb the membrane structure and apparently dissolve extractable lipids (Fig. 2 B–D).

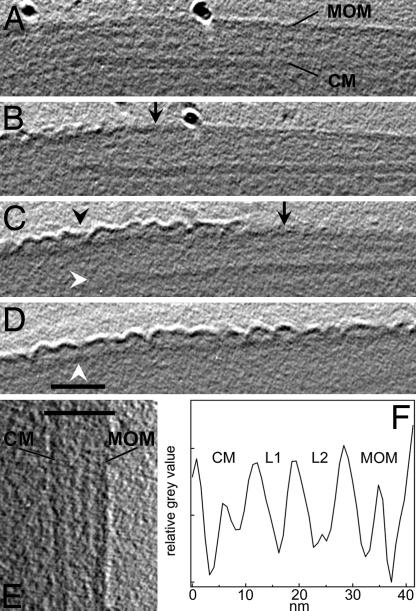

Fig. 2.

CET of intact M. smegmatis treated with octyl β-glucoside. (A–D) x–y slices of the tomogram without noise filtering. (A) Region of the apparently intact mycobacterial outer membrane (MOM), cytoplasmic membrane (CM), and periplasmic layers L1 and L2 as marked in F. The prominent black dot represents a gold marker used for alignment purposes. (B–D) Slices of cell wall positions with successively affected MOM (black arrowhead) and dissolved CM (white arrowhead in C) because of treatment with detergent. Black arrows indicate the approximate border between detergent-affected and apparently undisturbed regions of the MOM. (D) The white arrowhead indicates the putative mycolate layer. (Scale bar: 50 nm.) (E) Enlarged slices of the cell envelope illustrating the bilayer structure of the CM and the MOM. The bar indicates the width of the profile displayed in F. The averaged profile was calculated according to the procedure described in the legend of Fig. 1.

It is remarkable that the inner membrane is dissolved in regions where the detergent had affected the structure of the outer membrane. Octyl β-glucoside obviously made the mycobacterial outer membrane penetrable and destroyed the inner membrane. Also, the periplasmic layers appear to become affected. Degradation of structures by lytic processes cannot be excluded in places where the cytoplasm infiltrated the periplasm. The remaining layer below the outer membrane–detergent composite in Fig. 2 B–D likely represents the covalently linked mycolic acids that cannot be removed by detergents. The putative mycolic acid layer still shows local contacts to the detaching membrane material (Fig. 2C), but it is not obvious whether the layer was a constituent of the mycobacterial outer membrane.

Vitreous Cryosections Confirm the Bilayer Structure of Mycobacterial Outer Membranes.

Because, to our knowledge, membrane bilayer structures have not previously been rendered visible in tomograms of intact cells, we attempted to reproduce our results by means of thin, frozen-hydrated sections. Cells of both M. smegmatis and M. bovis were rapidly frozen under high-pressure conditions as described previously (20). Sections with a nominal thickness of 35 nm revealed similar substructures in the periplasmic space of both species and suggested that the periplasmic layers comprise several domains (Fig. 3). The bilayer structure of the cytoplasmic membrane as well as of the outer membrane is clearly resolved in regions perpendicular to the cutting direction. These are disturbed least by compression (21). The results confirm the structure of the mycobacterial outer membrane in Figs. 1 and 2, having an overall thickness of ≈8 nm in both M. smegmatis and M. bovis. Because we observed a dilation of structural detail by ≈20% perpendicular to the cutting direction in the periplasm of E. coli (see details in SI Table 1), the thicknesses of membranes and periplasmic layers as determined in cryosections from mycobacteria represent upper values (SI Table 2). The identical appearance of the two areas of high contrast in the bilayer structures (Fig. 3 B and C) indicates that the head group regions of the outer membrane exhibit similar mass (electron) densities that result in the same image (phase) contrast in the microscope. Thus, neither the mass distribution of lipid head groups in the two leaflets nor their cumulative thickness normal to the membrane plane gives rise to a clear morphological asymmetry.

Fig. 3.

Cryo-electron micrographs of vitreous cryosections from mycobacteria. The sections have a nominal thickness of 35 nm. (A) Cross-section of an M. smegmatis cell deformed by the cutting process. Regions perpendicular to the cutting direction (arrowheads) were used for further analyses. (Scale bar: 200 nm.) (B) Cell envelope of M. smegmatis (subarea from A). (C) Cell envelope of M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin. (Scale bars: 100 nm.) (D and E) Averaged profiles from the cell envelopes of M. smegmatis (D) and M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (E). CM, cytoplasmic membrane; L1 and L2, domain-rich periplasmic layers; MOM, mycobacterial outer membrane. Note that the distances between the membranes and layers are influenced by the cutting process. The bilayer structure of the CM and the MOM is discernible (B–E). Images are corrected for the contrast transfer function with fitted defocus values of −6.4 μm (B) and −6.7 μm (C).

Mycolic Acids Are an Essential Part of the Outer Membrane in C. glutamicum.

A mycolic acid-deficient mutant is required to assess the contributions of these lipids to the outer membrane. Such mutations are lethal in mycobacteria, whereas mycolic acid-deficient mutants of the closely related corynebacteria are viable (12). Therefore, we investigated wild-type C. glutamicum and the mycolic acid-free mutant Δpks13 (12) in vitreous cryosections. Fig. 4 demonstrates that C. glutamicum also possesses an outer membrane, as shown for M. smegmatis and M. bovis (Figs. 2 and 3). Importantly, the outer membrane is absent in the Δpks13 mutant (Fig. 4B). The mutant cell wall is thinner by 5–8 nm (mean: 6.4 nm; Fig. 4 B and D), which corresponds to the dimension of the missing bilayer structure. These results establish that mycolic acids are indispensable for the structural integrity of the outer membrane. This finding is consistent with the key role of mycolic acids for the cell wall permeability barrier in C. glutamicum (22). Furthermore, the periplasmic constituents are also organized in layers, indicating the formation of domains similar to those observed in mycobacteria (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Cryo-electron micrographs of vitreous cryosections from C. glutamicum. The sections have a nominal thickness of 35 nm. (A and C) Wild-type cells imaged at high (A) and low (C) defocus. The bilayer structure of the cytoplasmic membrane (CM) and of the outer membrane (OM) is resolved in minimally compressed parts of the cell envelope (arrowheads). (B) Projection of an ultrathin section of the mycolic acid-lacking mutant C. glutamicum Δpks13 at low defocus. (D) Thickness of the cell walls determined from several cells as measured from the surface of the CM to the outer surface of the cell wall. In images of the mutant cell wall, the cell boundary was identified by the change from higher to lower contrast (background). The center of the thickness curves corresponds to the position of the cell envelope “poles” that are oriented perpendicular to the cutting direction. Filled symbols, wild-type cells; open symbols, mutant cells.

Discussion

The Outer Cell Wall Layer Is the Mycobacterial Outer Membrane.

The combination of cryo-electron tomography that preserves the architecture of cells and of vitreous cryosections that allows one to identify structures in cross-sections of ultrathin specimens in projection proved suitable for the investigation of mycobacterial cell envelopes. Our study revealed the bilayer structure of lipid membranes in tomograms of intact bacteria, and thus opens the way to investigate cell envelopes and their macromolecular constituents by cellular CET in situ. The cryo-electron microscopical investigations in this study provided (i) direct evidence that the outermost layer in M. smegmatis, M. bovis, and C. glutamicum is an outer membrane with a bilayer structure, (ii) the insight that the layer of bound mycolic acids is leaky to amphiphilic molecules (octyl β-glucoside) once the integrity of the mycobacterial outer membrane has been affected by the detergent, and (iii) direct evidence for a multilayered cell wall organization in mycobacteria. The findings provide the molecular explanation for the existence of outer membrane proteins (17, 23) and periplasmic proteins, such as PhoA (24) in mycobacteria.

The Structure of the Mycobacterial Outer Membrane Differs from Current Models.

Numerous models for the mycobacterial cell envelope have been proposed (4, 7, 8, 25–28), but electron microscope investigations neither proved nor disproved the suggested architectures. CET and vitreous cryosections now confirm the presence of a mycobacterial outer membrane. In addition, our results call into question other aspects of the current models. First, the head group regions show almost identical mass densities in cryosections, which denotes that the average composition and distribution of head groups do not differ significantly with respect to their masses in either membrane leaflet. By contrast, the asymmetry of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is clearly visible in cryosections (21, 29). This result conflicts with the assumption that the inner leaflet of the mycobacterial outer membrane consists exclusively of mycolic acids with identical carbohydrate head groups and that the outer leaflet is a mixture of extractable lipids containing carbohydrates, peptides, and phosphorylated compounds. Second, the outer membrane is thinner than expected. Experiments with ultrathin sections of mycobacteria prepared by freeze substitution showed an electron-transparent zone of 7–12 nm that is thought to contain the bound mycolic acids and that is covered by the stained outer layer of ≈6–11 nm (10, 13–15) containing lipids (30, 31). The theoretical models suggest a hydrocarbon region of ≈9 nm with the lipid residues in an extended conformation. Taking into account that the α-chain region of bound mycolic acids is in the gel phase and the remainder, including extractable lipids, is in the fluid phase (6), the hydrocarbon region should be thinner. Based on the relative shrinkage of fluid membranes compared with those in the gel phase (32), we assessed a lower limit of ≈7 nm. However, the outer membrane has a measured total thickness of ≈8 nm or less, in perfect agreement with the porin MspA that serves as a molecular ruler. The hydrophobic surface of MspA is only 3.7 nm in height (17), and the porin (total length: 9.8 nm) is inaccessible to surface labeling over 7 nm from the periplasmic end to the middle of the hydrophilic rim (18). These distances correspond to the observed membrane dimensions, including headgroup regions. Moreover, the top part of MspA extends into the aqueous environment, as suggested by electron microscopy of isolated cell walls (16).

Modified Models of the Mycobacterial Outer Membrane.

Significant revisions are required to reconcile the current model of the mycobacterial outer membrane with the results of this study. The apparent symmetry suggests that similar (extractable) lipids are located in both leaflets of the mycobacterial outer membrane, which is in agreement with quantitative determinations (8). Accordingly, bound mycolic acids might not cover the cells completely. While this likely applies for corynebacteria (9), it was proposed to be different for mycobacteria (8). The smaller membrane thickness poses a more serious problem, unless the conformation of the hydrocarbon region is considerably different from the current view. Because x-ray experiments and molecular modeling indicate a tight packing of mycolic acids (8, 33), it is unlikely that their conformation is significantly smaller than assumed. Hence, it is legitimate to look for alternative architectures with a reduced membrane thickness. Two theoretical solutions with positional variations of mycolic acids are compatible with the results of this study. Either the meromycolates span the entire hydrophobic region and only the α-chain is covered by fatty acids from the other leaflet (Fig. 5A), or the mycolic acid layer contributes to the inner leaflet by the extended branches of the meromycolates (≈3.3 nm in length), whereas the major part is located below the outer membrane proper (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, for corynebacteria, it was already discussed that the inner leaflet contains soluble lipids (9, 34), whereas the bound mycolates rather serve to “tether” the outer membrane in an arrangement similar to that in Fig. 5A (28). The arrangement in Fig. 5B likely requires shielding of the hydrocarbon region that is exposed to the periplasm, which remains to be established, and apolar head groups of unbound lipids in the inner leaflet. Appropriate candidates are the apolar glycopeptidolipids in M. smegmatis (2) and phthiocerol dimycocerosates in M. tuberculosis, which represent the respective major extractable lipids and contribute to the permeability characteristics of the cell wall (30, 35, 36). The tentative model in Fig. 5B is in accordance with other experimental findings. (i) The outer membrane possesses a hydrophobic interphase that would account for a fracture plane observed in freeze–fracture experiments. (ii) Some extractable lipids are more intimately bound to mycolic acids than others. They might be located in the inner leaflet of the outer membrane (30, 31). (iii) It is consistent with a tight packing of mycolic acids and the results of Liu et al. (6), who observed that spin-labeled fatty acids partitioned only into the region of extractable lipids in isolated cell walls. (iv) It is consistent with the molecular structure of MspA. All outer membrane architectures discussed imply an indispensable role of the mycolic acids for the integrity or stability of the mycobacterial outer membrane. This implication is in agreement with the absence of the bilayer in the C. glutamicum mutant investigated here and the apparent loss of the mycobacterial outer membrane in species with impaired mycolate synthesis (10). These considerations suggest that it is essential to gain insight into the conformation of the hydrocarbon region (e.g., by means of molecular dynamics simulations of a complete membrane bilayer) and to localize the mycolic acids more precisely to gain a comprehensive view of the mycobacterial outer membrane.

Fig. 5.

Theoretical models of the mycobacterial outer membrane exhibiting reduced thickness. Lipids in the gel phase are indicated by straight lines, and those in the fluid phase, by zigzags. Open symbols indicate apolar headgroups; filled symbols represent polar headgroups. The covalent bonding of mycolic acids (red) to the arabinogalactan polymer is indicated. The profile of the pore protein corresponds to MspA of M. smegmatis (length: 9.8 nm). The molecular constituents are drawn approximately to scale. (A) The meromycolate of bound mycolic acids spans the hydrocarbon region. (B) The regions of meromycolates not being paired by the α-chain of mycolic acids interact with the inner leaflet and apolar headgroups of extractable lipids. The remaining parts form an additional hydrophobic zone below the outer membrane.

The investigation of frozen-hydrated preparations rendered the periplasmic layers visible, as well as domains that likely represent the complex organization of the peptidoglycan-arabinogalactan-mycolate polymer. The discernible structures imply a more differentiated architecture than that derived from chemically fixed and stained material. Once it is possible to assign the layers L1 and L2 and their domains to known constituents of the cell wall, we should be able to establish a more comprehensive model of the cell wall architecture. Such a model will also provide us with a better basis to understand the peptidoglycan and arabinogalactan structure in mycobacteria (37, 38).

In conclusion, we believe that proof of the existence of a mycobacterial outer membrane and, by inference, of a periplasmic space in mycobacteria, the structural features of the membrane, and the confirmation that extractable lipids play an important role for the membrane properties will have an impact on the design and interpretation of experiments aimed at elucidating the translocation pathways for nutrients, lipids, proteins, and antimycobacterial drugs across the cell envelope.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions.

M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin and M. smegmatis mc2155 were grown at 37°C in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium (Difco Laboratories) supplemented with 0.2% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 80, or on Middlebrook 7H10 agar (Difco Laboratories) supplemented with 0.2% glycerol. The media for the bacillus Calmette–Guérin strain were additionally supplemented with ADS (0.5% BSA fraction V, 0.2% dextrose, and 14 mM NaCl) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). E. coli DH5α was routinely grown in LB medium at 37°C. The S-layer-less C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 RES167 (39) and C. glutamicum Δpks13::km (12) were cultured at 30°C in BHI medium (Difco Laboratories). For growth of the Δpks13 strain, kanamycin was added to a final concentration of 25 μg/ml.

Detachment of the Outer Membrane.

M. smegmatis mc2155 was routinely grown overnight in Middlebrook 7H9 medium. After extensive washing with 25 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.0, buffer solution, cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in the same buffer containing 1.0% octyl β-glucoside. The cells were harvested and prepared for cryo-electron microscopy as described below.

Vitreous Sectioning.

Suspension cultures of M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin, M. smegmatis, or C. glutamicum were concentrated by low-speed centrifugation (4,000 × g), mixed 1:1 with extracellular cryoprotectant (40% dextran, 100–200 kDa), and drawn into copper capillary tubes. The tubes were rapidly frozen in an EM-Pact1 high-pressure freezer (Leica Microsystems). Cryosections of M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin, M. smegmatis, and C. glutamicum were produced with an Ultracut FC6 cryoultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems). The temperatures of the knife, the sample holder, and the chamber atmosphere were held between −150°C and −160°C. The copper tube was fixed in a chuck in the microtome and trimmed of copper and excess sample. Sections were prepared at a nominal thickness of 35 nm by means of a 25° diamond knife (Diatome) with a clearance angle of 6°. The cutting speed was between 1.0 and 10 mm/s. An ionizing gun was used to improve the gliding of section ribbons along the knife surface. The sections were transferred with an eyelash to a copper grid covered with a continuous carbon film and were firmly pressed by means of a stamping tool to improve contact.

Cryo-Electron Microscopy.

The grids with the vitreous sections were transferred to a Gatan cryoholder under liquid nitrogen and inserted into a Philips CM300 electron microscope operating at −180°C and equipped with a field emission gun as electron source, operating at 300 kV. The vitreous state of the sections was confirmed by electron diffraction. Images were recorded with a 2,048 × 2,048 pixel CCD camera (Gatan) with a primary magnification of ×37,000, corresponding to a pixel size of 0.44 nm at the CCD camera. Images were recorded with defocus values ranging from −1 to −12 μm to take advantage of inherent phase contrast. The total electron dose was kept below 1,000 e−/nm2 per projection image.

CET.

Quantifoil copper grids (Plano) were prepared by placing a 3.5-μl droplet of 10-nm colloidal gold clusters (Sigma) on each grid for subsequent alignment purposes. A 5-μl droplet taken from a midlogarithmic-phase culture was placed on a prepared grid, and after blotting was embedded in vitreous ice by plunge freezing into liquid ethane (temperature ≈ −170°C). Tomographic tilt series were recorded on a Tecnai Polara transmission electron microscope (FEI) equipped with a field emission gun and operated at 300 kV. The specimen was tilted about one axis with 2° increments over a total angular range of ±64°. To minimize the electron dose applied to the ice-embedded specimen, data were recorded under low-dose conditions by using automated data acquisition software (40). The total dose accumulated during the tilt series was kept below 160 e−/Å2. The microscope was equipped with a Gatan postcolumn energy filter (GIF 2002) operated in the zero energy loss mode with a slit width of 20 eV. To account for the increased specimen thickness at high tilt angles α, the exposure time was multiplied by a factor of 1/cos α. The recording device was a 2,048 × 2,048 pixel CCD camera (Gatan). The pixel size in unbinned images was 0.74 nm for E. coli and 0.79 or 0.82 nm for the mycobacteria at a primary magnification of ×27,500. Images were recorded at nominal −12-μm or −6-μm defocus, the latter condition aiming at higher resolution at the expense of contrast.

Image Processing.

All 2D projection images of a tilt series were aligned with respect to a common origin by using 10-nm colloidal gold particles as fiducial markers. Three-dimensional reconstructions were calculated either by weighted back projection or the simultaneous iterative reconstructive technique (SIRT) algorithm (41). A nonlinear anisotropic diffusion algorithm (42) was applied to reduce noise in survey tomograms. Three-dimensional data sets that were used for calculations of density profiles were not filtered. The distances between the cell envelope structures were determined by averaged cross-sections of the cell walls. For this purpose, the tomograms were oriented such that the longitudinal axis of the cells was parallel to the x–y plane of a 3D coordinate system. Subvolumes of the whole reconstructions that covered a long, preferably straight region of the cell wall were averaged in z. The z dimension of the subvolumes was kept small enough to prevent artificial blurring of the membrane because of the cylindrical shape of the cells. The resulting 2D projection was rotated to align the membranes parallel to the y axis. The image was separated into one-pixel-thick rows along the y direction, which were aligned subsequently via cross-correlation to unbend the curved cell envelope traces. The resulting image was projected along the y direction to obtain an averaged density profile across the cell envelope structures. In projections exhibiting sufficient contrast, we determined the contrast transfer function (43) and corrected for it to minimize optical aberrations introduced by the microscope. Images were processed with MatLab7 (Math Works) incorporating the TOM toolbox (44).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We are grateful to Mamadou Daffé for the mutant strains of C. glutamicum. We thank Günter Pfeifer for valuable help in the initial phase of the project, which was supported by a grant of the Network of Excellence for 3-Dimensional Electron Microscopy of the 6th framework of the European Union.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0709530105/DC1.

References

- 1.Barry CE, III, Lee RE, Mdluli K, Sampson AE, Schroeder BG, Slayden RA, Yuan Y. Prog Lipid Res. 1998;37:143–179. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(98)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daffé M, Draper P. Adv Microbial Physiol. 1998;39:131–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niederweis M. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1167–1177. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan PJ, Nikaido H. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:29–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minnikin D. In: The Biology of Mycobacteria. Tatledge C, Stanford J, editors. Vol 1. London: Academic; 1982. pp. 94–184. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, Rosenberg EY, Nikaido H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11254–11258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rastogi N, Hellio R, David HL. Zbl Bakt. 1991;275:287–302. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikaido H, Kim S-H, Rosenberg EY. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1025–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puech V, Chamie M, Lemassu A, Lanéelle M-A, Schiffler A, Gounon P, Bayan N, Benz R, Daffé M. Microbiol. 2001;147:1365–1382. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-5-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Salyden RA, Barry CE, III, Liu J. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7224–7229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etienne G, Villeneuve C, Billman-Jacobe H, Astarie-Dequeker C, Dupont M-A, Daffé M. Microbiol. 2002;148:3089–3100. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Portevin D, de Sousa-D'Auria C, Houssin C, Grimaldi C, Chami M, Daffé M, Guilhot C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:314–319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305439101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul TR, Beveridge TJ. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6508–6517. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6508-6517.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mineda T, Ohara N, Yukitake H, Yamada T. Microbiologica. 1998;21:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul TR, Beveridge TJ. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1542–1550. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1542-1550.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelhardt H, Heinz C, Niederweis M. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37567–37572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faller M, Niederweis M, Schulz GE. Science. 2004;303:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1094114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahfoud M, Sukumaran S, Hülsmann P, Grieger K, Niederweis M. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5908–5915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumeister W. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:933–937. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Amoudi A, Chang JJ, Leforestier A, McDowall A, Salamin LM, Norlén LPO, Richter K, Sartori Blanc N, Studer D, Dubochet J. EMBO J. 2004;23:3583–3588. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matias VRF, Al-Amoudi A, Dubochet J, Beveridge TJ. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6112–6118. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.20.6112-6118.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebhardt H, Meniche X, Tropis M, Krämer R, Daffé M, Morbach S. Microbiology. 2007;153:1424–1434. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/003541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alahari A, Saint N, Campagna S, Molle V, Molle G, Kremer L. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6351–6358. doi: 10.1128/JB.00509-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolschendorf F, Mahfoud M, Niederweis M. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:2435–2442. doi: 10.1128/JB.01600-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barry CE, III, Mdluli K. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:275–281. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee RE, Brennan PJ, Besra GS. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol. 1996;215:1–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80166-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chatterjee D. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1997;1:579–588. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(97)80055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dover LG, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, Pallen MJ, Parkhill J, Besra GS. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:225–250. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang P, Bos E, Heymann J, Gnaegi H, Kessel M, Peters PJ, Subramaniam S. J Microsc. 2004;216:76–83. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2720.2004.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ortalo-Magné A, Lemassu A, Lanéelle M-A, Bardou F, Silve G, Gounon P., Marchal G, Daffé M. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:456–461. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.456-461.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Etienne G, Laval F, Villeneuve C, Dinadayala P, Abouwarda A, Zerbib D, Galamba A, Daffé M. Microbiology. 2005;151:2075–2086. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27869-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heller H, Schaefer M, Schulten K. J Phys Chem. 1993;97:8343–8360. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong X, Hopfinger AJ. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:1052–1065. doi: 10.1021/bm034514c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bayan N, Houssin C, Chami M, Leblon G. J Biotechnol. 2003;104:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(03)00163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Camacho LR, Constant P, Raynaud C, Lanéelle M-A, Triccas JA, Gicquel B, Daffé M, Guilhot C. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19845–19854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brennan PJ. Tuberculosis. 2003;83:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dmitriev BA, Ehlers S, Rietschel ET, Brennan PJ. Int J Med Microbiol. 2000;290:251–258. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crick DC, Mahapatra S, Brennan PJ. Glycobiology. 2001;11:107R–118R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.9.107r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dusch N, Pühler A, Kalinowski J. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1530–1539. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1530-1539.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koster AJ, Grimm R, Typke D, Hegerl R, Stoschek A, Walz J, Baumeister W. J Struct Biol. 1997;120:276–308. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kak AC, Slaney M. Principles of Computerized Tomographic Imaging. New York: IEEE; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frangakis AS, Hegerl R. J Struct Biol. 2001;135:239–250. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sorzano COS, Jonic S, Núñez-Ramírez R, Boisset N, Carazo JM. J Struct Biol. 2007;160:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nickell S, Förster F, Linaroudis A, Del Net W, Beck F, Hegerl R, Baumeister W, Plitzko JM. J Struct Biol. 2005;149:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.