Summary

The heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycan, syndecan-1, plays a major role in multiple myeloma (MM) by concentrating heparin-binding growth factors on the surface of MM cells (MMC). Using Affymetrix microarrays and real-time RT-PCR, we show that the gene encoding heparanase (HPSE), an enzyme that cleaves HS-chains, is expressed by 11/19 myeloma cell lines (HMCLs). In HSPE-positive HMCLs, syndecan-1 gene expression and production of soluble syndecan-1, unlike expression of membrane syndecan-1, were significantly increased. Knockdown of HPSE by siRNA resulted in a decrease of syndecan-1 expression and soluble syndecan-1 production without affecting membrane syndecan-1 expression. Thus, HPSE influences expression and shedding of syndecan-1. Contrary to HMCLs, HPSE is expressed in only 4/39 primary MMC samples, whereas it is expressed in 36/39 bone marrow (BM) microenvironment samples. In the latter, HPSE is expressed at a median level in polymorphonuclear cells and T cells; it is highly expressed in monocytes and osteoclasts. Affymetrix data were validated at the protein level, both on HMCLs and patient samples. We report for the first time that a gene’s expression mainly in the BM environment, i.e. HSPE, is associated with a shorter event-free survival of newly diagnosed myeloma patients treated with high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. Our study suggests that clinical inhibitors of HPSE could be beneficial for patients with MM.

Keywords: Aged, Bone Marrow, metabolism, Bone Marrow Cells, metabolism, Cell Line, Tumor, Gene Expression Regulation, Enzymologic, Gene Expression Regulation, Neoplastic, Glucuronidase, physiology, Humans, Middle Aged, Monocytes, metabolism, Multiple Myeloma, diagnosis, enzymology, pathology, Neutrophils, metabolism, Osteoclasts, metabolism, Prognosis, Syndecan-1, biosynthesis

Keywords: myeloma, heparanase, syndecan-1

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a B cell neoplasia characterized by the growth of a clone of malignant plasma cells (PCs) in the bone marrow. Syndecan-1, a transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG), is expressed by both normal and malignant PCs and is now widely used to identify and purify these cells 1,2. We have previously shown that among the 10 known HSPGs, syndecan-1 is the main one present on the surface of PC 3. Syndecan-1 binds to extracellular matrix proteins and to growth factors that have a HS-binding domain, thus promoting their activity 4. In particular, it has been shown that syndecan-1 mediates hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) binding and promotes c-met signalling in myeloma cells (MMC)5. We and others have shown that syndecan-1 is necessary for the MMC growth activity of HGF and epidermal growth factor (EGF)-family ligands that have a HS-binding domain 3,5–7. Syndecan-1 concentrates high amounts of growth factors at the cell surface and then likely facilitates the activation of their receptors. The ectodomain of syndecan-1 can be cleaved from the MMC surface into a soluble form by metalloproteinases that remain to be identified in MMC 8,9. Soluble syndecan-1 is present at high levels in the serum of patients with MM and is an indicator of poor prognosis 8, 10, 11. It also accumulates in the bone-marrow microenvironment where it might sequester heparin-binding growth factors in the proximity of the tumor 12. Accordingly, it has been shown that soluble syndecan-1, which retains biologically active HS chains, can promote tumor growth in a myeloma SCID-hu mouse model13.

The function of HSPGs is regulated by extracellular enzymes that modulate the structure of HS-chains. One such enzyme is heparanase (HPSE), encoded by only one gene in mammalian cells 14, 15. HPSE is an endoglucuronidase that cleaves HS chains at only a few sites, resulting in HS fragments of 10–20 sugar units long 14, 16.

These fragments are long enough to bind growth factors and can be more biologically active than the native HS chains 17. HPSE is overexpressed in numerous tumors where it increases the angiogenic and metastatic potential of tumor cells 18. In patients with MM, HPSE activity could be found in bone marrow aspirates 19. HPSE increases microvessel density 19 and promotes growth and metastasis of MMC to bone in vivo 20.

Here we show for the first time that HPSE is involved in the regulation of syndecan-1 gene expression and controls the production of soluble syndecan-1 in myeloma cell lines. In patients with newly-diagnosed MM, HPSE is expressed mainly by cell-fractions of the bone marrow microenvironment, especially monocytes and osteoclasts, but weakly by MMC. High HPSE expression in bone marrow of patients with MM correlates with a shorter event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OAS).

Materials and Methods

Cell samples

Whole bone marrow samples (WBM) and purified MMC were obtained from 39 patients with MM at diagnosis (presenting at the university Hospitals of Heidelberg, Germany and Montpellier, France) after written informed consent was given. These patients were treated with high-dose chemotherapy (HDC) and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). The study was approved by the ethics boards of both Universities. According to the Durie-Salmon classification, 8 patients were in stage IA, 6 in stage IIA, 22 in stage IIIA, and three in stage IIIB. Four patients had IgAκ MM, 3 IgAλ MM, 19 IgGκ MM, 7 IgGλ MM, 4 Bence-Jones κ MM, 1 Bence-Jones λ MM, and 1 non-secreting MM. MMC were purified with anti-CD138 MACS microbeads (Miltenyi-Biotec, Paris, France). Normal WBM samples were obtained from healthy donors after informed consent was given. For 7 additional patients with newly-diagnosed MM, BM environment cells (ENV) were obtained by removing myeloma cells with CD138 Miltenyi microbeads (<1% plasma cells). For 5 other patients with newly-diagnosed MM, BM T cells, monocytes, and polymorphonuclear cells were purified as described previously 21. Osteoclasts and BM stromal cells (BMSCs) were generated in vitro as described 21. Immature dendritic cells (DCs) were generated from leukapheresis products of MM patients, as previously described 22. Briefly, 8 × 106 G-CSF-mobilized leukapheresis cells were plated in 2 ml of X-VIVO15 medium (BioWittaker, Walkersville, MD) per well in six-well flat-bottomed plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). Non-adherent cells were discarded by gentle rinsing after a 2-hour incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2. Adherent cells were cultured in X-VIVO15 medium with 2% human albumin, 100 ng/mL of GM-CSF (LEUKINE®, Berlex, Montville, NJ) and 25 ng/mL of IL-4 (Cellgenix, Freiburg, Germany) for 5 days. Mature DCs were obtained by a further 24-hour maturation with GM-CSF, IL-4 and TNFα. Human IL-6 dependant XG myeloma cell lines (HMCLs) were obtained in our laboratory 23,24. They were routinely maintained in RPMI1640, 10% fetal calf serum, and 2 ng/ml of IL-6 (Abcys, Paris, France). U266, SKMM, OPM2, LP1, and RPMI8226 HMCLs were purchased from ATTC (Rockville, MD, USA).

Microarrav hybridization

RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), the SV-total RNA extraction kit (Promega, Mannheim, Germany), and Trizol (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Biotinylated complementary RNA (cRNA) was amplified with double in vitro transcription, according to the Affymetrix small sample labeling protocol (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The biotinylated cRNA was fragmented and hybridized to the human genome U133 set (for HMCLs) or U133 Plus 2.0 (for patient samples) microarrays according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Affymetrix). Fluorescence intensities were quantified and analyzed using the GCOS software (Affymetrix).

Real-time reverse transcriptase-polvmerase chain reaction

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). We generated cDNA from 100 ng of total RNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Cergy-Pontoise, France). For real-time RT-PCR, we used Assay-on-Demand primers and probes and the TaqMan Universal Master Mix from Applied Biosystems (Courtaboeuf, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression was measured using the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System. For comparative analysis of gene expression, data were obtained by using the ΔΔCt method derived from a mathematical approach previously described. For each sample, the CT value for the gene of interest was determined and normalized to its respective CT value for beta2-microglobulin (B2M) (ΔCT=CT − CTB2M) or GAPDH (ΔCT=CT − CTGAPDH), and compared to a cell type used as a positive control. The formula used was: 1/2ΔCT sample − ΔCT control cell line. Ct values were collected during the log phase of the cycle. The results were expressed as the relative mRNA levels to control cell sample mRNA.

Western blot

Cells were lysed in 10 mM Tris-HCI (pH 7.05), 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 30 mM sodium pyrophosphate (NaPPi), 1% triton X-100, 5 μM ZnCl2, 100 μM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 20 mM p-nitrophenolphosphate (PNPP), 20 μg/ml aprotinin, 2.5 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM benzamidine, 5 μg/ml pepstatin, and 50 nM okadaic acid. Lysates were resolved on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide by gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher and Schuell, Kassel, Germany). Membranes were blocked for 2 hours at room temperature in 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris-HCI (pH 7.4), 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T), 5% non-fat milk, and then immunoblotted with a rabbit polyclonal anti-heparanase antibody (InSight Biopharmaceuticals, Rehovot, Israel) at a 1:1000 dilution. As a control for protein loading, we used a mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma, St Louis, MO). The primary antibodies were visualized with goat anti-rabbit (Sigma) or goat anti-mouse (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) peroxidase-conjugated antibodies by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system.

HPSE activity assay

HPSE activity in HMCLs was measured with a commercial assay based on the measurement of HPSE-induced degradation of biotinylated-HS fragments (b-HS) (Takara Bio Inc., Kyoto, Japan). Briefly, 10×106 cells were collected and suspended in 1 ml of extraction buffer. After cell debris removal by centrifugation, the supernatant was incubated with biotinylated-HS (b-HS) for 45 min at 37°C. The mixture was then incubated on a FGF-coated plate and undegraded b-HS was detected by HRP-streptavidin. This b-HS fragment is specifically designed so that it cannot bind to FGF when being degraded by HPSE, thus resulting in a lower HRP signal. Correspondence between absorbance at 450 nm and HPSE activity was determined by comparison to a standard curve established using unlabelled heparan sulfate as a standard substitute.

siRNA experiments

MMC were transfected with 1 nM of SMARTpool HPSE siRNA or 1 nM of non-targeting siRNA (siGLO) (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA). For transfections, Amaxa nucleofection technology was used (Amaxa, Köln, Germany). U266 myeloma cells were resuspended in the nucleofector T solution, available as part of the Amaxa cell optimization kit, and were electroporated using the T-001 protocol. Briefly, 4 × 106 cells were aliquoted in 100 μl with 15 μg of siRNA and were transferred to a cuvette and nucleofected with the Amaxa Nucleofector device. Cells were immediately transferred into wells containing 37°C prewarmed culture medium in 24-well plates. All experiments were performed in duplicate. At days 1–2 after electroporation, (i) the gene expression level of HPSE, syndecan-1, B2M, and GAPDH were analysed by real-time PCR; (ii) membrane syndecan-1 expression levels at the cell surface were analysed with a FACS-Calibur fluorescence-activated cell sorter (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA), using PE-conjugated anti-CD138 (Beckman-Coulter, Marseilles, France); (iii) cells were counted and viability was assessed using Annexin-V FITC (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany); (iv) soluble syndecan-1 was measured by ELISA from cell line culture supernatants.

Production of soluble syndecan-1 by myeloma cell lines

HMCLs in the exponential growth phase were cultured for 3 days. The cell count, the density of membrane syndecan-1 and the concentration of soluble syndecan-1 were measured every day for 3 days. Soluble syndecan-1 was measured using an ELISA kit with a detection level of 8 ng/ml (Diaclone, Besançon, France).

Immunohistochemistry

HPSE expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry on bone marrow biopsies from 20 newly diagnosed patients with myeloma, after written informed consent was given. Biopsies were fixed in Bouin’s, decalcified and routinely processed for paraffin embedding. Sections of Bouin-fixed, paraffin-embedded HMCLs (XG-2 and XG-7) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Tissue sections were deparaffined in xylene and rehydrated through graded concentrations of ethanol and distilled water. Epitope retrieval was performed by incubating the slides for 40 min in 10 mM EDTA buffer solution (Euromedex, Souffelweyersheim, France), pH 7.2, at 99.8°C, in a double-boiler. The slides were then incubated for 30 min in a blocking solution containing 10% goat serum (Dako cytomation S.A.S., Trappes, France). Slides were washed and endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol followed by 15-min incubation in CAS Block™ (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA). The slides were stained with a rabbit polyclonal anti-HPSE antibody (Insight Biopharmaceutical) at a concentration of 4.5 μg/ml. All stainings were performed with the NEXES Ventana Medical Systems automaton using the iVIEW™ DAB Detection Kit (Ventana Medical Systems, Illkirch, France) with goat anti-rabbit secondary Abs and diaminobenzidine as chromogen, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The immunohistochemical reaction was counterstained with haematoxylin. Heparanase staining was determined by two pathologists (P. R. and Thérèse Rousset, C.H.U. Montpellier, France). Each section stained with anti-HPSE was compared with an adjacent section stained with irrelevant rabbit serum as a negative control.

Statistical analysis

Gene Expression Profiles were analyzed with our bioinformatics platform (RAGE, remote analysis of microarray gene expression, http://rage.montp.inserm.fr) designed by T. Reme (INSERM U475, Montpellier, France) or SAM (Significance Analysis of Microarrays) software. SAM analysis was applied to 22530 probesets with at least 3 presences in the 19 HMCLs samples and a variation coefficient ≥ 20. We performed a two class comparison between HPSEpos and HPSEneg HMCls, with 1000 permutations and a false discovery rate of 7.7%. Statistical comparisons were made with the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test or the Student t-test for pairs. The statistical significance of differences in event-free survival between groups of patients was estimated by the log-rank test. An event was defined as relapse or death (for EFS) or as death (for OAS). The survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

HPSE expression in myeloma cell lines

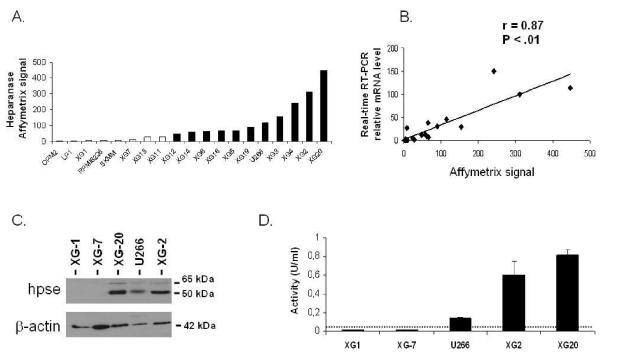

Expression of HPSE was evaluated with Affymetrix U133 set microarrays on 19 HMCLs. Eleven of 19 HMCLs displayed a “present” call for the HPSE probeset (HPSEpos) with a median expression level of 90 (range 48–448, Figure 1 A). The other 8 cell lines displayed an “absent” call (HPSEneg) with a low expression level (median=6, range=2–28) (Figure 1 A). The call (“present” or “absent”) is determined by Affymetrix GCOS-software and indicates whether a gene is reliably expressed or not 25. The data were validated by real-time RT-PCR (r = 0.87, P < .01, Figure 1B). HPSE expression at the protein level was evaluated by Western blot analysis. HPSE was detected in 3/3 HMCLs with a “present” Affymetrix detection call (U266, XG-2 and XG-20), but not in those with an “absent” Affymetrix call (XG-1 and XG-7, Figure 1C). The 50 kDa MW active form of the enzyme was predominant, but the 65 kDa MW proenzyme could also be detected (Figure 1C). Furthermore, HMCLs were tested for HPSE activity using an assay based on the measurement of HPSE-induced degradation of biotinylated-HS fragments (b-HS). In this assay, undegraded b-HS is bound to an FGF-coated plate and bound b-HS is detected by HRP-streptavidin. The b-HS fragment is specifically designed so that it does not bind to FGF when degraded by HPSE, thus resulting in a lower HRP signal. HPSE activity was high in the HPSEpos XG-2 and XG-20 HMCLs (0.6 U/ml and 0.82 U/ml, respectively). It was intermediate in U266 (0.14 U/ml) and below the detection limit (0.05 U/ml) in the HPSEneg XG-1 and XG-7 HMCLs (Figure 1D). Thus, HPSE activity correlated with HPSE expression in HMCLs.

Figure 1. HPSE expression and activity are heterogeneous in HMCLs.

A. Expression of HPSE in 19 HMCLs determined using Affymetrix U133 set microarrays. White and black histograms indicate that the Affymetrix call is “absent” or “present”, respectively. B. Correlation between Affymetrix and real-time RT-PCR HPSE expression data. For real-time RT-PCR, HPSE expression in each sample was normalized to that of GAPDH and the XG-2 cell line was used as a reference with the arbitrary value of 100. C. HMCLs were lysed and the lysates were separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot with a polyclonal anti-HPSE antibody. Both the 65 kDa MW pro-enzyme and the 50 kDa MW active form were identified. β-actin was used as a loading control. Results are of one experiment representative of three. kDa, molecular weight in thousands. D. HPSE activity was determined using an ELISA-type detection assay. HMCLs lysates were incubated with biotinylated HS (b-HS) and then only undegraded b-HS could bind an FGF-coated ELISA plate. Bound b-HS was detected with HRP-streptavidin followed by a colorimetric assay. HPSE activity corresponding to absorbance at 450 nm was determined by comparison with a standard curve as described in “Material and Methods”. One unit is defined as the activity that can degrade 0.063 ng of b-HS when reacted at pH 5.8 at 37°C for one min. The detection limit (dotted line) was 0.05 U/ml. Results are of one experiment representative of three.

Gene expression profile associated with HPSE expression in myeloma cell lines

As the HPSE signal expression in HMCLs is either present or absent, these HMCLs are of interest to study the biological function of HPSE in MM. We compared the gene expression profile of the 11 HPSEpos HMCLs with those 8 HPSEneg HMCLs in a supervised analysis performed with the SAM software using 1000 permutations. Only probesets that were “present” in more than 3 samples and had at least a 2-fold change in expression were retained in the analysis. This resulted in a list of 41 probesets that were all overexpressed in HPSEpos HMCLs, with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 7.7%. These 41 probesets interrogated 33 genes and 3 expressed sequence tags (EST), which are listed in Table 1. Interestingly, syndecan-1 was among those 41 genes.

Table 1. SAM-defined overexpressed genes in HMCLs expressing HPSE.

These data are the 41 probesets overexpressed at least two-fold in the 11 HPSEpos HMCLs compared to the 8 HPSEneg HMCLs (SAM analysis with a FDR of 7.7%). Genes are ordered based on the SAM score.

| Probeset | Gene Name | Gene description | SAM Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 219403_s_at | HPSE | heparanase | 1.82 |

| 222881_at | HPSE | heparanase | 1.82 |

| 230241_at | IFRG15 | Interferon responsive gene 15 | 1.82 |

| 219253_at | FAM11B | family with sequence similarity 11. member B | 1.78 |

| 227697_at | SOCS3 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | 1.78 |

| 212037_at | PNN | Pinin. desmosome associated protein | 1.73 |

| HUMISGF3A_MA_at | STAT1 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 1.91 kDa | 1.73 |

| 204908_s_at | BCL3 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 3 | 1.65 |

| 221876_at | DKFZp762P2 | hypothetical protein DKFZp762P2111 | 1.65 |

| 218935_at | EHD3 | EH-domain containing 3 | 1.65 |

| 201316_at | PSMA2 | Proteasome (prosome. macropain) subunit. alpha type. 2 | 1.65 |

| HUMISGF3A_3_at | STAT1 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 1.91 kDa | 1.65 |

| 212269_s_at | MCM3AP | minichromosome maintenance deficient 3 associated protein | 1.61 |

| 201286_at | SDC1 | syndecan-1 | 1.61 |

| 238418_at | SLC35B4 | Solute carrier family 35. member B4 | 1.61 |

| 209969_s_at | STAT1 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 1.91 kDa | 1.61 |

| 230917_at | --- | 1.57 | |

| 227749_at | --- | 1.57 | |

| 202086_at | MX1 | myxovirus resistance 1. interferon-inducible protein p78 (mouse) | 1.57 |

| 237942_at | SNRK | SNF related kinase | 1.57 |

| HUMISGF3A_3_at | STAT1 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 1.91 kDa | 1.57 |

| 237299_at | --- | 1.53 | |

| 221764_at | C19orf22 | chromosome 19 open reading frame 22 | 1.53 |

| 217925_s_at | C6orf106 | chromosome 6 open reading frame 106 | 1.53 |

| 201082_s_at | DCTN1 | dynactin 1 (p150. glued homolog. Drosophila) | 1.53 |

| 206662_at | GLRX | glutaredoxin (thioltransferase) | 1.53 |

| 227713_at | KATNAL1 | Katanin p60 subunit A-like 1 | 1.53 |

| 225752_at | NIPA1 | non imprinted in Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome 1 | 1.53 |

| 201964_at | ALS4 | amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 4; juvenile | 1.49 |

| 207522_s_at | ATP2A3 | ATPase. Ca++ transporting, ubiquitous | 1.49 |

| 236831_at | C3orf6 | chromosome 3 open reading frame 6 | 1.49 |

| 239629_at | CFLAR | CASP8 and FADD-like apoptosis regulator | 1.49 |

| 225097_at | HIPK2 | homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2 | 1.49 |

| 211824_x_at | NALP1 | NACHT. leucine rich repeat and PYD containing 1 | 1.49 |

| 213241_at | PLXNC1 | plexin C1 | 1.49 |

| 226782_at | SLC25A30 | Solute carrier family 25. member 30 | 1.49 |

| 235035_at | SLC35E1 | Solute carrier family 35. member E1 | 1.49 |

| 212926_at | SMC5L1 | SMC5 structural maintenance of chromosomes 5-like 1 (yeast) | 1.49 |

| HUMISGF3A_MA_at | STAT1 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 1.91 kDa | 1.49 |

| 200887_s_at | STAT1 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 1.91 kDa | 1.49 |

| 209197_at | SYT11 | Synaptotagmin XI | 1.49 |

Correlation between soluble syndecan-1 production and HPSE gene expression in HMCL

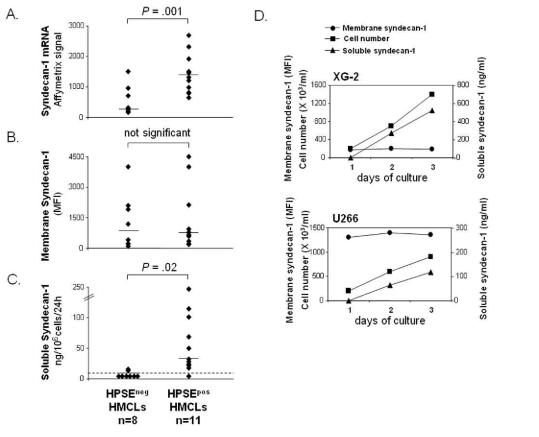

As shown in Figure 2A, syndecan-1 gene was significantly overexpressed 4.3-fold in HPSEPOS HMCLs (median=1320) compared to HPSEneg HMCLs (median =304). As syndecan-1 is expressed as a membrane protein that is cleaved by metalloproteinases, we quantified membrane expression and soluble syndecan-1 production in HMCLs (Figures 2B and 2C). Using FACS analysis, no significant difference in membrane syndecan-1 expression was found between HPSEpos HMCLs (median MFI=656) and HPSEneg HMCLs (Median MFI=799) (Figure 2B). The rate of soluble syndecan-1 production in culture supernatant of HMCLs was measured during the exponential growth phase, between day 2 and day 3 of culture. Indeed, soluble syndecan-1 accumulated in culture medium in parallel with cell count increase, as shown for XG-2 and U266 in Figure 2D. Soluble syndecan-1 production was below the detection level (<8 ng/mL) in 6/8 HPSEneg HMCLs, whereas it was detected in 10/11 HPSEpos HMCLs with a median production of 35 ng/106 cells/24h (P = .02, Figure 2C). The rate of soluble syndecan-1 production did not correlate with the density of membrane syndecan-1 in the 19 HMCLs (data not shown). This data suggested that HPSE may influence syndecan-1 gene expression and/or the shedding of soluble syndecan-1.

Figure 2. HMCLs that express HPSE produce higher amounts of soluble syndecan-1.

A. Syndecan-1 expression was determined in the 19 HMCLs using Affymetrix U133 set microarrays. B. Mean fluorescence intensity of membrane syndecan-1 expression determined with a PE-conjugated anti-GDI38 MoAb, a PE-isotype-matched control MoAb, and FACS analysis. For each cell line, the mean fluorescence intensity obtained with the control MoAb was set between 4–6. C. For the 19 HMCLs, the rates of production of soluble syndecan-1 per 106 cells and per 24 h was determined during the 2nd and 3rd days of culture (exponential growth phase) and measured by ELISA. The dotted line indicates the detection limit of the test (<8 ng/mL). D. For XG-2 and U266 HMCLs, the cell count, the density of membrane syndecan-1 and the concentration of soluble syndecan-1 in the culture supernatant were determined each day for three days.

HPSE downregulation reduces syndecan-1 mRNA expression and soluble syndecan-1 production in HMCLs

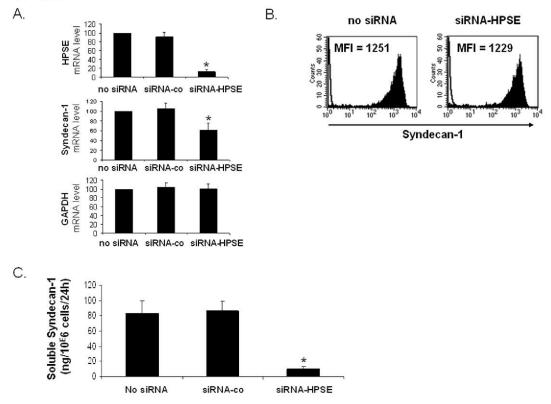

In order to address this question, we used siRNA technology. Electroporation of the U266 HMCL with a HPSE-specific siRNA resulted in a 87% inhibition of HPSE expression as determined by real-time RT-PCR in five independent experiments (P< .01) whereas electroporation with a non-targeting control siRNA (siRNA-co) did not affect the mRNA level of HPSE (Figure 3A, first panel). Of major interest, HPSE downregulation induced a 38% reduction of syndecan-1 mRNA expression (P<.01), without affecting GAPDH mRNA expression (Figure 3A, 2nd and 3rd panel). The HPSE non-targeting siRNA-co did not affect syndecan-1 or GAPDH expression. We then investigated whether targeting HPSE mRNA may influence membrane syndecan-1 expression or soluble syndecan-1 production. Electroporation of HPSE-specific siRNA had no effect on the expression of membrane syndecan-1 (Figure 3B). In contrast, HPSE downregulation resulted in nearly 80% inhibition (P< .01) of soluble syndecan-1 production (Figure 3C). No inhibition was found with the control siRNA (Figure 3C). Of note, the siRNA-HPSE did not significantly affect the survival and proliferation of U266 cells (data not shown). Those data indicate that targeting HPSE mRNA results in a decrease of syndecan-1 gene expression and soluble syndecan-1 production without effecting the expression of membrane syndecan-1.

Figure 3. Syndecan-1 mRNA and soluble syndecan-1 are downregulated in HPSE-silenced cells.

U266 cells were electroporated with no siRNA or with a non-targeting control siRNA (siRNA-co) or with an HPSE-specific siRNA (siRNA-HPSE), and cultured for two days. A. At day 2, HPSE, syndecan-1, and GAPDH expression were quantified by real-time RT-PCR and were normalized for each sample to that of B2M. Cells electroporated with no siRNA were used as a reference and were assigned the arbitrary value of 100. Data are means ±SD of the gene expression levels determined for five independent experiments. *Indicates that the mean value is statistically significantly from that obtained with the control (no siRNA), using a Student t test for pairs (P≤.05). B. Membrane expression of syndecan-1 was determined with a PE-conjugated anti-GDI38 MoAb and a PE-isotype-matched control MoAb and FACS analysis. Results shown are those of one experiment representative of five. C. U266 cells were electroporated with no siRNA or with a non-targeting control siRNA (siRNA-co) or with an HPSE-specific siRNA (siRNA-HPSE). Data are expressed as the means ±SD of the rates of production of soluble syndecan-1 per 106 cells and per 24 h determined during the first and second days of culture after electroporation determined in five separate experiments. Indicates that the mean value is statistically significantly different from that obtained in the control (no siRNA), using a Student f test for pairs (P≤.05).

Heparanase is mainly expressed by cells from the bone-marrow environment, in particular monocytes and osteoclasts

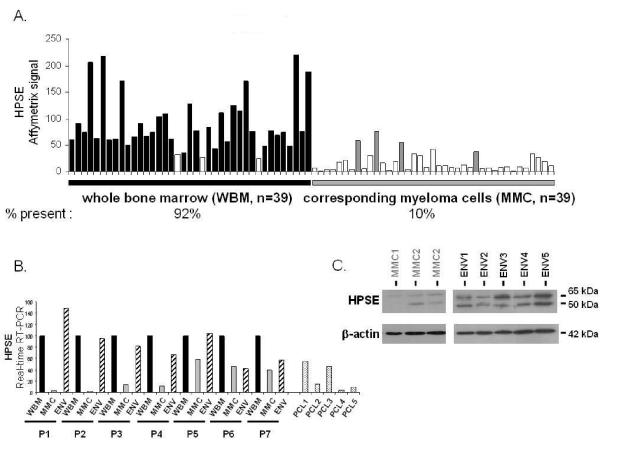

In order to determine if HPSE is expressed in the bone marrow of patients with MM, we evaluated the gene expression level of HPSE in the whole bone marrow (WBM) (including MMC and cells of the microenvironment) of 39 newly-diagnosed patients as well as in the MMC purified from the BM of the same 39 patients, using U133 Plus 2.0 Affymetrix microarrays. A high HPSE expression was detected in the WBM samples (Figure 4A). The HPSE expression in the WBM samples (median=76, range=25–221) was 7.6-fold higher (P < .0001) than that found in the corresponding MMC (median=10, range=8–26). Furthermore, HPSE had an Affymetrix “present call” in 92% (36/39) of the WBM samples, whereas it had a “present call” in only 10% (4/39) of the purified MMC samples (Figure 4A). HPSE was also expressed in the WBM of seven normal donors (median=84, range=70–110, data not shown). To confirm those data, HPSE expression was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR in the WBM of seven additional newly-diagnosed patients, as well as in the corresponding purified MMC and the corresponding microenvironment cells depleted from MMC (< 2% MMC, noted ENV, figure 4B). For each patient, the WBM sample was used as a reference and was assigned the arbitrary value of 100. For 4/7 patients (P1–P4), HPSE was almost exclusively expressed by cells from the environment (ENV). For the other three patients (P5–P7), HPSE was expressed by both MMC and cells from the environment (Figure 4B). As HPSE was much more frequently expressed in HMCLs derived from patients with extramedullary myeloma (58% of presence, see Fig 1A) compared to BM primary MMC, we looked for HPSE expression in purified MMC from five patients with plasma cell leukemia (PCL1–5). HPSE expression was in the same range than that found in purified MMC from patients with intramedullary myeloma (Figure 4B). Environment cells depleted from MMC (ENV) and purified MMC were also analysed by Western blot. HPSE protein was detected in 5/5 environment cell samples. It was barely detectable in 3/3 purified MMC samples but its expression was much lower than that found in the environment cells (Figure 4C), thus confirming the Affymetrix and real-time RT-PCR data.

Figure 4. Comparison of HPSE expression between WBM and the corresponding purified MMC of patients.

A. Expression of HPSE was determined in the WBM of 39 myeloma patients as well as in the myeloma cells purified from the bone marrow of the same patients, using Affymetrix U1332 Plus 2.0 microarrays. White histograms indicate that the Affymetrix call is “absent”; black (WBM) and grey (MMC) histograms indicate that it is “present”. B. HPSE expression was measured by real-time RT-PCR in the whole bone marrow of seven MM patients (WBM, black bars), in the corresponding MMC (grey bars), in the corresponding microenvironment depleted from myeloma cells (<2% MMC, ENV, crosshatched bars) and in MMC from five patients with PCL. HPSE expression was normalized to that of GAPDH. For each patient, the WBM sample was used as a reference and was assigned the arbitrary value of 100. For the five patients with PCL, the WBM sample of patient 1 was used as a reference. The median percentage of plasma cells in bone marrow aspirates from the seven patients with intramedullary myeloma was 8,5% (range=6–40). C. HPSE protein expression was determined in microenvironment cells depleted from MMC (< 2% MMC, ENV1-5) of five patients and in purified MMC of three other patients (MMC1-3). Cells were lysed and the lysates were separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot with a polyclonal anti-HPSE antibody. Both the 65 kDa MW pro-enzyme and the 50 kDa MW active form were identified. β-actin was used as a loading control. Results are from two separate western blots, one with 3 purified MMC, the other one with the 5 microenvironment cells. The HPSEpos XG-2 HMCL was used as a positive HPSE protein control in the two blots (results not shown). kDa, molecular weight in thousands.

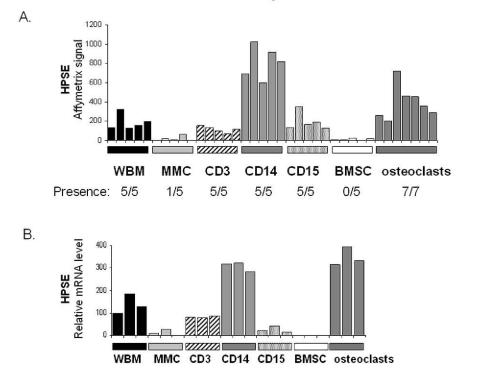

In order to identify the cell populations expressing HPSE in the myeloma microenvironment, bone marrow T lymphocytes (CD3+), monocytes (CD14+), polymorphonuclear cells (CD15+), and MMC (CD138+) were purified from the BM of five patients with newly-diagnosed myeloma. In addition, BM stromal cells (BMSCs, n=5) and osteoclasts (n=7) were generated from MM patients’ cells in vitro. For each population, the gene expression level of HPSE was assayed using Affymetrix U133 plus 2.0 microarrays. As shown in figure 5A, HPSE was mainly expressed by CD14+ monocytes and osteoclasts. HPSE expression in monocytes (median=819) and osteoclasts (median=355) was, respectively, 200-fold and 88-fold higher than that in MMC (median=4). HPSE was not expressed by BMSCs. All data were validated by real-time RT-PCR (Figure 5B). Of note, no HPSE expression could be detected in monocyte-derived immature or mature dendritic cells using real-time RT-PCR (data not shown). Thus, HPSE is highly expressed by the BM environment, mainly by monocytes and osteoclasts, and occasionally by primary MMC.

Figure 5. Expression of HPSE in subpopulations of the BM environment of patients with MM.

A. Expression of HPSE was determined in the WBM of five MM patients as well as in MMC, CD3+ cells, CD14+ cells, and CD15+ cells purified from the bone marrow of the same patients, using Affymetrix plus 2.0 microarrays. The five BMSC and seven osteoclast samples were obtained by culture in vitro. B. HPSE expression was measured by real-time RT-PCR. HPSE expression was normalized to that of GAPDH. One WBM sample was used as a reference and was assigned the arbitrary value of 100.

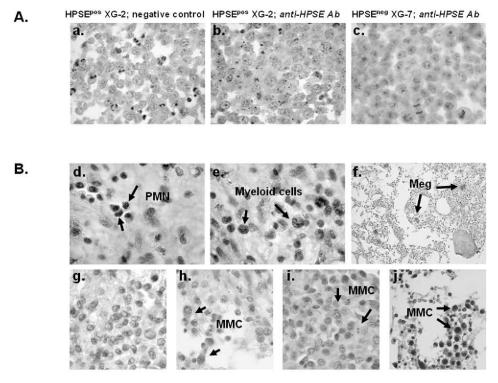

To further clarify the contribution of MMC in the HPSE expression, bone marrow biopsies from 20 patients with MM were stained using the polyclonal anti-HPSE antibody. The anti-HPSE antibody efficiently labelled the XG-2 HMCL which has a “present” Affymetrix detection call (Figure 6A, panels a–b), unlike the XG-7 HMCL which has an “absent” call (Figure 6A, panel c). As expected from the Affymetrix data, HPSE was expressed by polymorphonuclear cells and myeloid cells within the BM of 20/20 patients (as shown for one patient in Figure 6B, panels d–e). In addition, a strong staining of megakaryocytes was found (Figure 6B, panel f). Regarding MMC, HPSE expression was heterogeneous among patients. Data are summarized in Table 3. HPSE expression lacked in the MMC of 3/20 patients (as illustrated for one patient in Figure 6B, panel g). In the majority of the patients, a strong heterogeneity was found with few positively stained MMC close to negative tumor cells (Figure 6B, panels h–i, and Table 3). This heterogeneous HPSE expression among MMC is in agreement with previously published data 19. HPSE expression level in the positively stained MMC was low. In 2/20 samples, we found a higher percentage of more intensely labelled MMC (Figure 6B, panel j, and Table 3). Of note, a strong nuclear staining appeared in the MMC from those two patients.

Figure 6. HPSE is expressed by BM environment cells and by a minor subpopulation of myeloma cells.

A. XG-2 and XG-7 cells were stained with control rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Ab) (panel a) or with a polyclonal anti-HPSE Ab at 4.5 μg/ml (panels b,c). Note the dot-like staining signal. B. BM biopsies from patients with MM were stained with the polyclonal anti-HPSE Ab (4.5 μg/ml). Panels d–f: environment cells in the BM of one patient representative of twenty. PMN, polymorphonuclear cells; Meg, megakaryocytes. Panels g–j: heterogeneous HPSE expression among MMC in the bone marrow of four representative patients (g=patient 1; h=patient 4; i=patient 11; j=patient 20; see Table 3). The brown reaction product indicates the location of polyclonal Ab against HPSE. Original magnification of 1000× (or200× in f).

Table 3. Heparanase expression in the MMC from 20 patients with MM.

BM biopsies from patients with MM were stained with the polyclonal anti-HPSE Ab (4.5 μg/ml) as described in material and methods. Both HPSE-positive and HPSE-negative MMC were counted on each slide and results are expressed as the percentage of HPSE-positive MMC.

| Patients | Percentage of HPSE-positive MMC |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0% |

| 2 | 0% |

| 3 | 0% |

| 4 | 1% |

| 5 | 2% |

| 6 | 2% |

| 7 | 3% |

| 8 | 4% |

| 9 | 6% |

| 10 | 7% |

| 11 | 10% |

| 12 | 10% |

| 13 | 12% |

| 14 | 14% |

| 15 | 18% |

| 16 | 20% |

| 17 | 24% |

| 18 | 25% |

| 19 | 73% |

| 20 | 75% |

| Median: 8.6% | |

Taken together, those data indicate that HPSE is mainly expressed by cells of the BM environment of patients with MM.

HPSE expression in the whole bone marrow of myeloma patients at diagnosis correlates with survival

We investigated the connection of clinical parameters with HPSE gene expression for 30 of the 39 patients with newly-diagnosed MM who were treated with HDC and ASCT. Patients were classified into two groups: 15 HPSE:low patients with the lowest HPSE expression in the WBM (median expression=60) and 15 HPSEhigh patients with the highest HPSE expression (median expression=125) (Figure 7A, left panel). The HPSEhigh group had an increased percentage of patients with elevated C-reactive protein and beta2-microglobulin (P≤ .05, Table 2). Other clinical parameters - lactate dehydrogenase, serum calcium, albumin, hemoglobin, age, presence of bone lesions, and cytogenetic abnormalities - were not significantly different. According to the international staging system (ISS), the HPSEhigh group included a significantly higher frequency of patients with stage III MM and a lower frequency of patients with stage I MM. The stages according to the Durie-Salmon classification were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 2). HPSEhigh patients had a shorter EPS (50% of survival = 6 months, P=.017) than HPSE1low patients (50% of survival not reached) (Figure 7A). The OAS was also significantly shorter in HPSEhlgh patients (P=.023). In a Cox proportional-hazard model monitoring for the highest or lowest HPSE expression in the WBM as well as ISS stage, both parameters were significantly predictive for EPS (P=.029 and P=.002, respectively). If HPSE expression was tested together with ISS staging, ISS staging remained an independent prognostic factor (P=.02) unlike HPSE expression. Classifying these 30 patients into two groups according to HPSE expression in MMC did not result in any significant differences in the EFS or OAS between the two groups (Figure 7B). This is in agreement with the low HPSE expression in MMC compared to that found in the microenvironment. Those data indicate that HPSE expression in the WBM, but not in the MMC, is linked to the prognosis of myeloma patients.

Figure 7. Event free survival and overall survival of patients with newly-diagnosed MM according to HPSE expression in the WBM and MMC.

A. Expression of HPSE in the WBM of 30 newly diagnosed patients (left panel) and Kaplan-Meier survival curves for MM patients with the highest (HPSEhigh, n=15) or the lowest (HPSElow, n=15) HPSE expression in the WBM (right panel). B. Expression of HPSE in the purified MMC from 30 newly-diagnosed patients and Kaplan-Meier survival curves for MM patients with the highest (n=15) or the lowest (n=15) HPSE expression in the MMC.

Table 2. Clinical data for HPSEhigh and HPSElow patients.

Thirty newly-diagnosed patients with MM were separated in two subgroups (HPSEhigh and HPSElow) according to HPSE gene expression in the WBM, assayed with Affymetrix U133 microarrays. Data are the percentages of patients within each subgroup with the indicated clinical or biological parameters. Statistical comparisons were made with the Chi square test. Data are shown in italics when the percentages between the two groups are significantly different.

| HPSElow n=15 | HPSEhigh n=15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| % of patients in each subgroup | P = | ||

| Age ≥ 65 years | 13 | 27 | 0.36 |

|

Beta2-microglobulin < 3.5 mg/l > 5.5 mg/l |

80 0 |

47 27 |

0.05 0.03 |

| C-reactive protein > 5 mg/l | 7 | 40 | 0.03 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase ≥ 240 mmol/l | 20 | 27 | 0.66 |

| Albumin < 35 g/l | 33 | 40 | 0.7 |

| Hemoglobin < 10 g/dl | 20 | 47 | 0.1 |

| Ca++ < 2,65 mmol/l | 100 | 100 | 1 |

| Kappa light chain | 67 | 53 | 0.45 |

| Lambda light chain | 33 | 47 | 0.45 |

| IgA subtype | 20 | 13 | 0.61 |

| Bone lesions ≥ 3 | 15 | 23 | 0.61 |

| t(4;14) | 15 | 0 | 0.14 |

| del(chr13) | 62 | 46 | 0.39 |

| DS classification | 0.82 | ||

| Stage I | 13 | 7 | |

| Stage II | 20 | 20 | |

| Stage III | 67 | 73 | |

| ISS classification | 0.008 | ||

| Stage 1 | 47 | 7 | |

| Stage II | 53 | 60 | |

| Stage III | 0 | 33 | |

Discussion

Given the major role of the syndecan-1 HSPG in MM, mainly as a co-receptor for numerous MMC growth factors, we investigated the expression and possible function of HPSE in myeloma. We found that HPSE is expressed in 11/19 HMCLs and influences syndecan-1 mRNA expression: (i) when comparing the gene expression profile of the 11 HPSEpos HMCLs to that of the 8 HPSEneg HMCLs, syndecan-1 was one of the genes overexpressed with the highest fold change in HPSEpos HMCLs; (ii) the silencing of HPSE expression with siRNAs induced a downregulation of syndecan-1 mRNA. We used the siRNA methodology because neutralizing antibodies to HPSE are not presently commercially available. Interestingly, though HPSE expression does not interfere with membrane syndecan-1 expression, it is strongly correlated with the rate of soluble syndecan-1 production by HMCLs. Seven of 8 HPSEneg HMCLs failed to produce detectable soluble syndecan-1, whereas 10/11 of HPSEpos HMCLs produced large amounts. In addition, targeting HPSE mRNA with siRNA induced a strong inhibition of soluble syndecan-1 production. One possible mechanism to explain the effect of HPSE on the shedding of syndecan-1 could be that degradation of HS chains by the HPSE enzyme would render membrane syndecan-1 more easily accessible to metalloproteinases. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that treatment of MM cells with the bacterial enzyme heparitinase, which completely degrades HS chains, also induced an increase in soluble syndecan-1 production by HMCLs (data not shown). Of note, membrane syndecan-1 expression in the 19 HMCLs did not correlate with the rate of soluble syndecan-1 production and the HPSE inhibition by siRNA did not affect membrane syndecan-1 expression. One explanation is that the downregulation of HPSE yields a decreased mRNA expression and concomitantly reduces shedding of syndecan-1 protein, which taken together does not influence the net amount of syndecan-1 on the surface of HMCLs.

HPSE expression has been documented in several solid tumors. In particular, by real-time RT-PCR, increased levels of HPSE mRNA have been found in human breast, colon, lung, prostate, and ovarian tumors, compared with corresponding normal tissues 16. In order to demonstrate the biological significance of HPSE in multiple myeloma, we analysed HPSE expression in the bone marrow of patients with MM. Here we show that HPSE is expressed in the BM of patients with MM, both at the mRNA and protein levels, and that cells of the environment are the main source of HPSE. Among the different cell components of the BM, the highest HPSE expression was found in monocytes. We detected no HPSE expression in monocyte-derived immature or mature dendritic cells that were generated in vitro. Our findings are in agreement with recently published data showing that HPSE protein is present both in monocytes and dendritic cells unlike HPSE mRNA, which is exclusively expressed in monocytes. This indicates that HPSE gene expression and synthesis mainly occur in monocytes or in the very early steps of differentiation toward immature dendritic cells 26. HPSE was also expressed in T cells and polymorphonuclear cells, at a lower level. As MMC survive and proliferate in a tumor niche involving BMSCs and osteoclasts which cannot be harvested in vivo, we produced them in vitro and found that osteoclasts highly expressed HPSE, unlike BMSCs. It is likely that the MMC themselves can also be a source of HPSE, at least in some patients. However, overall, HPSE expression in MMC was much lower than that found in the environment cells. First, the HPSE Affymetrix signal was 7.6-fold lower in MMC compared to WBM samples, and it was reliably detectable in tumor cells of only 10% of the patients (4/39). Secondly, HPSE protein expression measured by Western-blot was barely detectable in MMC compared to environment cells. Third, using immunohistochemistry, we found that HPSE was expressed by the environment cells of 20/20 patients whereas most MMC were negative or expressed low levels of HPSE. In the majority of the patients, few positively stained MMC were surrounded by HPSE-negative MMC. This heterogeneity, which is in agreement with the previous report by Kelly et al. 19, might explain why we found a low HPSE expression in the majority of the purified MMC samples compared to the BM environment samples. It is noteworthy that in 2/20 patients (patients 19 and 20) we found groups of intensely labelled myeloma cells. This is in agreement with the Affymetrix data showing that 10% of the patients expressed reliable amounts of HPSE mRNA in the MMC. Contrary to primary MMC, HPSE expression was detectable in 58% (11/19) of the HMCLs. We already pointed out that HMCLs may express some genes – HB-EGF, IL-6, and APRIL – that are originally expressed by the BM environment but not by primary MMC themselves 6,27. Of note, HPSE expression in MMC from patients with plasma cell leukemia was in the same range than that found in MMC from patients with intramedullary myeloma.

A major finding of this study is that HPSE expression in the WBM of patients with MM is an indicator of poor prognosis. Thus, HPSE mRNA expression in the WBM holds prognostic value even though its median expression in patients with MM did not differ from that of healthy donors. In agreement with this observation, it was previously reported that healthy individuals and MM patients have similar amounts of IGF-1 in the circulation whereas MM patients with low serum IGF-1 levels have a favourable prognosis 28. Despite the low number of patients whose HPSE expression and clinical data were available and the short follow-up (median=2 years), the difference in EPS and OAS between HPSEhigh and HPSElow patients was highly significant with HPSE expression predicting a less favourable disease outcome. HPSEhigh patients had higher CRP and beta2-microglobulin levels than HPSElow patients. HPSE expression was also linked to ISS staging, the HPSElow group having a higher percentage of stage 1 and a lower percentage of stage 3 patients than the HPSEhigh group. The prognostic value of HPSE expression in the WBM was not independent of ISS staging. Of note, the percentage of MMC in the WBM in the HPSElow group (median 4.5; range 0.03–45) was not statistically significantly different from that in the HPSEhigh group (median 2.9; range 0.5–12). Classifying patients in two groups according to HPSE expression in purified MMC did not yield any difference in EFS or OAS, neither in this set of 30 patients (see Figure 6B) nor in a larger set of MMC from 104 newly-diagnosed patients (data not shown). This again emphasizes that HPSE is mainly expressed by the BM environment and that this expression is biologically relevant. This is the first study showing that a gene measured in the bone marrow microenvironment has prognostic value in MM.

The fact that HPSE controls syndecan-1 expression and soluble syndecan-1 production may explain at least in part the poor prognosis of HSPEhigh patients, as increased levels of soluble syndecan-1 have been described as a bad prognostic factor in patients with MM 10,11. Soluble syndecan-1 can promote tumor growth in a murine model 13, presumably because it can sequester heparin binding growth factors that support MMC growth as well as angiogenic factors like VEGF 5,29,30, thus providing MMC with an increased amount of growth factors. Consistently, Kelly et al have shown HPSE to increase microvessel density 19, which in turn correlates with poor prognosis in MM 31,32. In an independent series of 20 newly-diagnosed patients, we did not find any significant correlation between HPSE expression in the WBM and soluble syndecan-1 concentration in the plasma (data not shown), likely because soluble syndecan-1 can be retained by the BM matrix and hence only partially circulates 33. The impact of HPSE expression on survival may further be linked to the modification of syndecan-1 HS chains by the endoglysosidase enzymatic activity of HPSE. The ability of HPSE to degrade HS chains into small fragments is critical to promote tumor growth in epithelial tumors 16,34 and HPSE enzymatic activity is present in the BM aspirates of patients with myeloma 19. HPSE may promote tumor growth by releasing heparin-binding MMC growth factors or angiogenic factors that are trapped within the environment through the HS chains of syndecan-1. Accordingly, it has been shown that HPSE can release HS-bound growth factors such as FGF2 from the extracellular matrix 35. Alternatively, HPSE may improve the HS-mediated effect of heparin binding-growth factors. Indeed, small fragments resulting from the HPSE cleavage were reported to be more biologically active than the native HS chains from which they are derived 17. Finally, besides its endoglycosidase activity, it is now becoming clear that HPSE might have other non-enzymatic functions which may also have an impact on tumor growth. It was not within the scope of our study to elucidate the mechanism involved in the regulation of syndecan-1 gene expression and shedding by HPSE, but one can speculate that it might involve such non-enzymatic functions. These non-enzymatic functions include stimulation of endothelial cell invasion via AKT pathway activation 36, enhanced cell adhesion of glioma 37, lymphoma 38 and T cells mediated by β1-integrin 39, and induction of VEGF expression 40. These mechanisms are poorly understood but might involve a yet undefined receptor that could lead to activation of transduction pathways and mediate diverse biological effects.

Altogether, these data provide evidence that HPSE can modulate syndecan-1 activity through the cleavage of its HS chains but also through the regulation of syndecan-1 mRNA expression and shedding. HPSE, mainly produced by the environment, is an indicator of poor prognosis for MM patients. Therefore, HPSE inhibitors like PI-88 which is currently in clinical trials 41, will be of interest for the treatment of patients with MM.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by grants from the Ligue Nationale Centre Le Cancer (équipe labellisée), Paris, France. It is part of a national program called « Carte d’ldentité des Tumeurs » (CIT) funded by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (http://www.ligue-cancer.net).

References

- 1.Wijdenes J, Vooijs WC, Clement C, et al. A plasmocyte selective monoclonal antibody (B-B4) recognizes syndecan-1. Br J Haematol. 1996;94:318–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costes V, Magen V, Legouffe E, et al. The Mi15 monoclonal antibody (anti-syndecan-1) is a reliable marker for quantifying plasma cells in paraffin-embedded bone marrow biopsy specimens. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1405–1411. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahtouk K, Cremer FW, Reme T, et al. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans are essential for the myeloma cell growth activity of EGF-family ligands in multiple myeloma. Oncogene. 2006;25:7180–7191. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couchman JR. Syndecans: proteoglycan regulators of cell-surface microdomains? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:926–937. doi: 10.1038/nrm1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derksen PW, Keehnen RM, Evers LM, van Oers MH, Spaargaren M, Pals ST. Cell surface proteoglycan syndecan-1 mediates hepatocyte growth factor binding and promotes Met signaling in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002;99:1405–1410. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahtouk K, Jourdan M, De Vos J, et al. An inhibitor of the EGF receptor family blocks myeloma cell growth factor activity of HB-EGF and potentiates dexamethasone or anti-IL-6 antibody-induced apoptosis. Blood. 2004;103:1829–1837. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahtouk K, Hose D, Reme T, et al. Expression of EGF-family receptors and amphiregulin in multiple myeloma. Amphiregulin is a growth factor for myeloma cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:3512–3524. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhodapkar MV, Kelly T, Theus A, Athota AB, Barlogie B, Sanderson RD. Elevated levels of shed syndecan-1 correlate with tumour mass and decreased matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity in the serum of patients with multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 1997;99:368–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.3893203.x. [published erratum appears in Br J Haematol 1998 May;101(2):398] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhodapkar MV, Abe E, Theus A, et al. Syndecan-1 is a multifunctional regulator of myeloma pathobiology: control of tumor cell survival, growth, and bone cell differentiation. Blood. 1998;91:2679–2688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein B, Li XY, Lu ZY, et al. Activation molecules on human myeloma cells. CurrTop Microbiol Immunol. 1999;246:335–341. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60162-0_41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seidel C, Sundan A, Hjorth M, et al. Serum syndecan-1: a new independent prognostic marker in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2000;95:388–392. [published erratum appears in Blood 2000 Apr 1;95(7):2197] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanderson RD, Yang Y, Suva LJ, Kelly T. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans and heparanase--partners in osteolytic tumor growth and metastasis. Matrix Biol. 2004;23:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, Yaccoby S, Liu W, et al. Soluble syndecan-1 promotes growth of myeloma tumors in vivo. Blood. 2002;100:610–617. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vlodavsky I, Friedmann Y, Elkin M, et al. Mammalian heparanase: gene cloning, expression and function in tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 1999;5:793–802. doi: 10.1038/10518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kussie PH, Hulmes JD, Ludwig DL, et al. Cloning and functional expression of a human heparanase gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:183–187. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vlodavsky I, Goldshmidt O, Zcharia E, et al. Mammalian heparanase: involvement in cancer metastasis, angiogenesis and normal development. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:121–129. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato M, Wang H, Kainulainen V, et al. Physiological degradation converts the soluble syndecan-1 ectodomain from an inhibitor to a potent activator of FGF-2. 1998;4:691–697. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vlodavsky I, Friedmann Y. Molecular properties and involvement of heparanase in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:341–347. doi: 10.1172/JCI13662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly T, Miao HQ, Yang Y, et al. High heparanase activity in multiple myeloma is associated with elevated microvessel density. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8749–8756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y, Macleod V, Bendre M, et al. Heparanase promotes the spontaneous metastasis of myeloma cells to bone. Blood. 2005;105:1303–1309. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreaux J, Cremer FW, Reme T, et al. The level of TACI gene expression in myeloma cells is associated with a signature of microenvironment dependence versus a plasmablastic signature. Blood. 2005;106:1021–1030. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarte K, Fiol G, Rossi JF, Klein B. Extensive characterization of dendritic cells generated in serum-free conditions: regulation of soluble antigen uptake, apoptotic tumor cell phagocytosis, chemotaxis and T cell activation during maturation in vitro. Leukemia. 2000;14:2182–2192. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang XG, Gaillard JP, Robillard N, et al. Reproducible obtaining of human myeloma cell lines as a model for tumor stem cell study in human multiple myeloma. Blood. 1994;83:3654–3663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rebouissou C, Wijdenes J, Autissier P, et al. A gp130 interleukin-6 transducer-dependent SCID model of human multiple myeloma. Blood. 1998;91:4727–4737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu WM, Mei R, Di X, et al. Analysis of high density expression microarrays with signed-rank call algorithms. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1593–1599. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.12.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benhamron S, Nechushtan H, Verbovetski I, et al. Translocation of active heparanase to cell surface regulates degradation of extracellular matrix heparan sulfate upon transmigration of mature monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:6417–6424. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein B, Tarte K, Jourdan M, et al. Survival and proliferation factors of normal and malignant plasma cells. Int J Hematol. 2003;78:106–113. doi: 10.1007/BF02983377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Standal T, Borset M, Lenhoff S, et al. Serum insulinlike growth factor is not elevated in patients with multiple myeloma but is still a prognostic factor. Blood. 2002;100:3925–3929. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Vos J, Hose D, Reme T, et al. Microarray-based understanding of normal and malignant plasma cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;210:86–104. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahtouk K, Hose D, Reme T, et al. Heparanase influences expression and shedding of syndecan-1, and its expression by the bone marrow environment is a bad prognostic factor in multiple myeloma. ASH Annual meeting abstract; 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munshi NC, Wilson C. Increased bone marrow microvessel density in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma carries a poor prognosis. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:565–569. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pruneri G, Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, et al. Microvessel density, a surrogate marker of angiogenesis, is significantly related to survival in multiple myeloma patients. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:817–820. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayer-Garner IB, Sanderson RD, Dhodapkar MV, Owens RB, Wilson CS. Syndecan-1 (CD138) immunoreactivity in bone marrow biopsies of multiple myeloma: shed syndecan-1 accumulates in fibrotic regions. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:1052–1058. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parish CR, Freeman C, Hulett MD. Heparanase: a key enzyme involved in cell invasion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1471:M99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(01)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitelock JM, Murdoch AD, lozzo RV, Underwood PA. The degradation of human endothelial cell-derived perlecan and release of bound basic fibroblast growth factor by stromelysin, collagenase, plasmin, and heparanases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10079–10086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gingis-Velitski S, Zetser A, Flugelman MY, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase induces endothelial cell migration via protein kinase B/Akt activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23536–23541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zetser A, Bashenko Y, Miao HQ, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase affects adhesive and tumorigenic potential of human glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7733–7741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldshmidt O, Zcharia E, Cohen M, et al. Heparanase mediates cell adhesion independent of its enzymatic activity. Faseb J. 2003;17:1015–1025. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0773com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sotnikov I, Hershkoviz R, Grabovsky V, et al. Enzymatically quiescent heparanase augments T cell interactions with VCAM-1 and extracellular matrix components under versatile dynamic contexts. J Immunol. 2004;172:5185–5193. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zetser A, Bashenko Y, Edovitsky E, Levy-Adam F, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression: correlation with p38 phosphorylation levels and Src activation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1455–1463. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parish CR, Freeman C, Brown KJ, Francis DJ, Cowden WB. Identification of sulfated oligosaccharide-based inhibitors of tumor growth and metastasis using novel in vitro assays for angiogenesis and heparanase activity. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3433–3441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]