Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Our goal was to evaluate the effects of breastfeeding and dietary experiences on acceptance of a fruit and a green vegetable by 4- to 8-month-old infants.

METHODS

Forty-five infants, 44% of whom were breastfed, were assigned randomly to 1 of 2 treatment groups. One group was fed green beans, and the other was fed green beans and then peaches at the same time of day for 8 consecutive days. Acceptance of both foods, as determined by a variety of measures, was assessed before and after the home-exposure period.

RESULTS

During the initial exposure, infants ate more calories from peaches than from green beans. Breastfed infants showed greater liking of peaches, as did their mothers, who ate more fruits in general than did mothers who formula fed. Although formula-feeding mothers ate more green beans, there was no difference in their infants’ acceptance of this vegetable. For breastfed and formula-fed infants, repeated dietary exposure to green beans, with or without peaches, resulted in greater consumption of green beans (56.8 vs 93.6 g). Only infants who experienced green beans with peaches displayed fewer facial expressions of distaste during feeding. Mothers were apparently unaware of these changes in acceptance.

CONCLUSIONS

Breastfeeding confers an advantage in initial acceptance of a food, but only if mothers eat the food regularly. Once weaned, infants who receive repeated dietary exposure to a food eat more of it and may learn to like its flavor. However, because infants innately display facial expressions of distaste in response to certain flavors, caregivers may hesitate to continue offering these foods. Mothers should be encouraged to provide their infants with repeated opportunities to taste fruits and vegetables and should focus not only on their infants’ facial expressions but also on their willingness to continue feeding.

Keywords: breastfeeding, flavor, fruits and vegetables, nutrition, infants

Because consumption of vegetables and fruits is linked to lower risks of obesity and certain cancers,1 health organizations throughout the world recommend 5 to 13 servings of fruits and vegetables per day, depending on caloric intake.2,3 Despite such recommendations, adults are not eating enough fruits and vegetables,3 and neither are children.4,5 The 2004 Feeding Infants and Toddlers study, which was designed to update knowledge on the feeding patterns of US children, alarmingly revealed that toddlers ate more fruits than vegetables and 1 in 4 did not consume even 1 vegetable on a given day. They were more likely to be eating fatty foods and sweet-tasting snacks and beverages and less likely to be eating bitter-tasting vegetables.4,5 None of the top 5 vegetables consumed by toddlers was a dark-green vegetable.5

From the perspective of the ontogeny of taste,6,7 these data are not surprising because of the functional importance of taste in nutrient selection, especially in children. It has been hypothesized that preferences for sweet tastes evolved to solve a basic nutritional problem of attracting children to sources of high calories during periods of maximal growth,8 whereas bitter rejection evolved to protect against poisoning, because many toxic substances are bitter and distasteful by nature.9 Consequently, preferences for foods (eg, dark-green vegetables) and beverages (eg, coffee) that taste bitter are largely learned.

When asked whether there is an optimal way to introduce fruits and vegetables into infants’ diets, health professionals are faced with a difficult challenge because of the paucity of evidence-based research.10,11 Many research studies that revealed relationships between food habits in childhood and those later in life were correlational in nature12,13 and consequently inconclusive.11 Because of the lack of research, many feeding practices are based on idiosyncratic parental behavior, family traditions, or medical lore.14,15 Such lore relates that infants should not have any experience with fruits before they are introduced to green vegetables, because their inherent sweet preferences might interfere with acceptance of foods that taste bitter. Although no data support the contention that experience with fruits hinders vegetable acceptance,16 there is evidence suggesting that other early experiences promote healthy eating patterns.

The first type of experience results from the mother’s eating habits during pregnancy. Specifically, prenatal experiences with food flavors, which are transmitted from the mother’s diet to the amniotic fluid, lead to greater acceptance and enjoyment of those foods during weaning. In an experimental study, infants whose mothers were assigned randomly to drink carrot juice during the last trimester of pregnancy enjoyed carrot-flavored cereals more than did infants whose mothers did not drink carrot juice or eat carrots.17

Similar findings were observed for infants whose mothers were assigned randomly to drink carrot juice during lactation, which leads us to the second type of experience, namely, breastfeeding.17 If their mothers eat fruits and vegetables, then breastfed infants learn about these dietary choices, because a variety of food flavors are transmitted to human milk.18,19 These varied sensory experiences with food flavors may help explain why breastfed infants are less picky20 and more willing to try new foods,21,22 which contributes to greater fruit and vegetable consumption in childhood.13,23,24

The third type of experience, which occurs once children begin eating solid foods, involves repeated dietary exposure. Children became more accepting of a food after repeated exposure.16,22 Merely looking at the food was not sufficient. Children had to taste the food to learn to like it.25

The present study followed from this body of research and was designed to elucidate some of the factors that contribute to acceptance of a green vegetable and a fruit initially and after different types of dietary exposure. Three hypotheses were tested. First, we hypothesized that, relative to formula-fed infants, breastfed infants would be more accepting of a novel food, but only if their mothers consumed such foods regularly. Second, we hypothesized that repeated exposure to green beans would lead to greater acceptance of that food. Third, we hypothesized that infants would be more accepting of green beans if their previous dietary experience with this food was associated with a fruit, because research reveals that liking for a bitter-tasting vegetable or beverage is enhanced if it is associated with sweet tastes.26,27

METHODS

Subjects

Forty-five mothers whose infants had been born at term and healthy and were between the ages of 4 and 8 months were recruited through advertisements in local newspapers, breastfeeding support groups, and the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Twenty of the mothers in this study were Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children participants, 12 of whom had some college education and 10 of whom breastfed their infants. The ethnicity of the subjects was 36.4% black, 45.5% white, 6.8% Hispanic, and 11.4% other/mixed ethnicity.

Only infants who had been weaned to cereal but had very little experience with fruits and vegetables qualified for the study. At the start of the study, infants had been eating cereal for 6.7 ± 1.6 weeks. Ten of the infants had been fed bananas, applesauce, or an orange vegetable 1 or 2 times, and 1 ate bananas daily. None had exposure to green beans, and only 1 had tasted peaches. Twenty of the infants were currently breastfeeding and had been breastfed exclusively for at least the first 2 months of life, whereas 21 were formula fed and had no or very little (ie, <7 days) experience with breastfeeding. The remaining 4 infants were both breastfed and formula fed. The Office of Regulatory Affairs at the University of Pennsylvania approved all procedures, and informed consent was obtained from each mother.

Procedures

To accustom infants to some aspects of the testing procedures, mothers were sent some items (eg, bib) to use during the 3 days preceding and throughout the experimental period.16 No additional foods or beverages were introduced into the infants’ diet during the study. To increase compliance, telephone contact was made with the mothers, who recorded the time of day and types and quantities of foods and liquids they fed their infants throughout the study. All of the mothers complied with these instructions.

Foods

The target foods, namely, puréed green beans (Stage 2; 1.30 J/g [0.31 cal/g]) and peaches (Stage 2; 2.97 J/g [0.71 cal/g]), were commercially available infant foods from Gerber Products (Fremont, MI). The maximal amounts extracted from the containers were ~ 113 g of green beans and ~ 99 g of peaches.

Experimental Design

Mother/infant dyads participated in a 12-day experimental study. Each mother brought her infant to the Monell Chemical Senses Center 2 days before (days 1 and 2) and after (days 11 and 12) an 8-day home-exposure period. On days 1 and 11, we evaluated infants’ acceptance of green beans; on days 2 and 12, we evaluated their acceptance of peaches. Infants were assigned randomly to 1 of 2 treatment groups. One group (group GB) was fed green beans, whereas the other (group GB-P) was fed green beans and then (within 1 hour) peaches throughout the 8-day home-exposure period (days 3–10). To minimize possible effects attributable to different levels of satiation, the test sessions at the Monell Chemical Senses Center and on each exposure day occurred at the same time of day, with infants having last been fed 2.6 ± 0.1 hours before feeding.

Monell Chemical Senses Center Test Sessions

Using methods established in our laboratory,16,28 testing occurred under naturalistic conditions, in which infants determined the pacing and duration of the feeding. Mothers fed at their customary pace until the child rejected the food ≥3 consecutive times or finished 2 jars of food. Immediately after each feeding session, the mothers rated, on a 9-point scale, how much they thought their infant liked the food; greater numbers reflected greater liking.

Home-Exposure Period

At the end of the second test day, mothers were given jars of puréed infant food for the home-exposure period. Each jar was labeled with the date on which the contents of that particular jar should be fed. On each exposure day, mothers, who were trained at the Monell Chemical Senses Center, offered their infants the contents of 1 jar of puréed green beans until the infant either refused the food on ≥3 consecutive occasions or finished the contents of the jar. Only 1 child finished the jar on each day of the exposure period. Within the next hour, mothers in group GB-P offered their infants the contents of 1 jar of puréed peaches. Mothers refrained from feeding the infants any milk or other solid food during the 1-hour periods that preceded and followed these feedings, to ensure that the infants were hungry during the feeding and to avoid any interference during the postingestive period, respectively.29 Mothers then resealed each jar and stored it in a freezer until they returned the jars to the Monell Chemical Senses Center on day 11.

Videotape Analyses

In addition to determining intake, which primarily reflects how much a food is wanted,30 we measured the infants’ facial expressions during feeding, which are measures of hedonic responses or liking in nonverbal animals,30 including human infants.17,31–33 Each videotape was subjected to frame-by-frame analysis by means of a Windows-based, event recorder program, the Observer (Noldus Information Technology, Heerlen, Netherlands). A trained rater who was certified in the Facial Action Coding System34 and who was unaware of the infants’ group designation scored the first 2 minutes of each test session for all except 3 infants. We focused on brow movements (ie, brow lowering and inner brow raises), nose wrinkling, upper-lip raising, squinting, and gaping, as illustrated in Fig 1, because these facial expressions have been identified as prototypical of distaste31,34 and are more discriminating in gauging infants’ like and dislike of tastes and flavors.17,31,32 Gaping and 2 other facial responses (dimpling and lip tightening) were not included in the final analyses, because at least two thirds of the infants did not display these faces while being fed green beans. Because of marked individual differences in the types of facial responses made during feeding, we also report on the total number of distaste facial expressions for each spoonful offered.

FIGURE 1.

Examples of types of facial expressions displayed during the first 2 minutes of feeding: brow lowerer (A), inner brow raise (B), squint (C), nose wrinkle (D), upper-lip raise (E), and gape (F).

Questionnaires

Mothers were queried about their infants’ feeding history and various aspects of their own eating habits, such as the frequency with which they ate various vegetables and fruits. All except 1 completed a 10-item scale that measured their food neophobia (the propensity to approach or to avoid novel foods) and an 8-item scale that measured general neophobia.35 All except 1 mother completed a 95-item questionnaire that measured infant temperament.36

Statistical Analyses

For each infant, we determined total food intake (grams and calories), duration of feeding (minutes), rate of feeding (grams per minute), frequency of distaste facial expressions made per spoonful offered during the first 2 minutes of the feeding, and mothers’ ratings of their infants’ enjoyment of the food for each test session at the Monell Chemical Senses Center. To determine whether there were differences between infants’ initial responses to green beans and peaches, repeated-measures analyses of variance were conducted with food (green beans or peaches) as the within-subjects variable. To determine whether breastfeeding affected initial acceptance, separate 1-way analyses of variance were conducted with feeding history (breastfed or formula fed) as the between-subjects variable for each measure. The 4 infants who were both breastfed and formula fed were excluded from this analysis because of the small sample size. Similar analyses were conducted on lactating and formula-feeding mothers’ dietary habits.

To determine the effects of dietary treatment on green bean and peach acceptance, 2-way repeated-measures analyses of variance were conducted with treatment group (group GB or group GB-P) as the between-subjects factor and time (before or after home exposure) as the within-subjects factor. Four infants were excluded from the analyses of green bean acceptance and 3 from those of peach acceptance because mothers were non-compliant with test procedures (n = 2), infants were sick during testing or exposure (n = 2), or infants ate the maximum amount of food offered during their initial exposure (n = 3). All summary statistics are expressed as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

There were no significant differences between the 2 treatment groups in any of the characteristics measured (Table 1). Infants who were exclusively breastfed for the first few months of life were not significantly different from formula-fed infants in their age, weight-for-age percentile, and temperament or their mothers’ age and income (data not shown). Lactating mothers had more years of education (P < .02) and weaned their infants to cereal later (P < .001) than did those who fed exclusively formula. However, there was no relationship between initial acceptance of green beans or peaches and the amount of time the infants had been fed cereal.

TABLE 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Characteristic | Group GB | Group GB-P |

|---|---|---|

| Infants | ||

| Age, mean ± SEM, mo | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.2 |

| Gender, female/male | 6/10 | 15/14 |

| Infants’ feeding history | ||

| Breastfed, never formula fed, n | 7 | 13 |

| Formula fed, never breastfed, n | 9 | 12 |

| Both breastfed and formula fed, n | 0 | 4 |

| Age at cereal introduction, mean ± SEM, mo | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.2 |

| Mothers | ||

| Age, mean ± SEM, y | 32.2 ± 1.4 | 31.6 ± 0.9 |

| BMI, mean ± SEM, kg/m2 | 30.2 ± 2.4 | 27.1 ± 1.0 |

| Multiparous, n | 12 | 23 |

| Years of schooling, mean ± SEM | 14.7 ± 0.5 | 14.8 ± 0.4 |

| Food neophobia score (range: 10–70), mean ± SEM | 30.6 ± 3.6 | 36.3 ± 2.6 |

| General neophobia score (range: 8–56), mean ± SEM | 24.4 ± 2.1 | 24.2 ± 1.8 |

| Mother/infant pairs, n | 16 | 29 |

Initial Acceptance and Liking

Initially, infants ate more calories from peaches (201.7 ± 24.3 J [48.2 ± 5.8 cal]) than from green beans (73.6 ± 9.6 J [17.6 ± 2.3 cal]; P < .001). As they ate, the majority of infants displayed squints (95%), brow movements (82%), and upper-lip raises (76%), whereas less than one half (42%) wrinkled their noses. Although there were marked differences in the prevalence of these facial expressions among individuals and in response to the food being eaten, the facial displays were related to food acceptance. For example, infants who squinted more or displayed more distaste expressions overall ate peaches (P < .03) and green beans (P < .05) at slower rates.

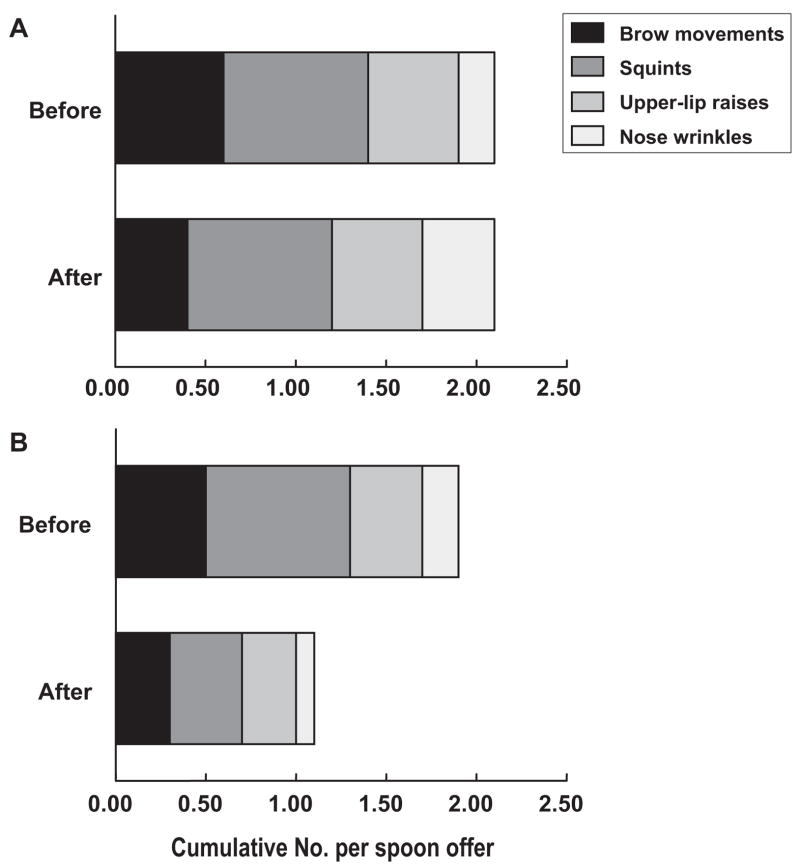

Infants who were breastfed for the first few months of life consumed significantly more peaches (P < .001) (Fig 2A) for longer periods of time (P < .01) at a faster rate (P < .03) and displayed fewer upper-lip raises (P < .05) and negative facial responses overall during feeding (P < .05) (Fig 2B), compared with formula-fed infants. As shown in Fig 2C, the mothers of the breastfed infants ate significantly more fruits during the previous week, compared with formula-feeding mothers (P < .04).

FIGURE 2.

Amounts of peaches consumed (A) and number of distaste expressions displayed per spoonful of peaches (B) by breastfeeding and formula-feeding infants during their first feeding of peaches at the Monell Chemical Senses Center and number of times lactating and formula-feeding mothers reported eating fruits during the previous week (C). a P < .05, compared with breastfed infants (A and B) or lactating mothers (C).

Although formula-feeding and breastfeeding mothers reported that they ate green beans and green vegetables at levels below current recommendations (green beans were eaten 1.7 ± 0.20 times and green vegetables 4.3 ± 0.50 times during the week preceding testing), formula-feeding mothers ate more green beans after the birth of their child than lactating mothers (2.4 ± 0.4 times per week, compared with 1.1 ± 0.3 times per week; P < .02). Despite the formula-feeding mothers’ more frequent consumption, there were no significant differences between formula-fed and breastfed infants’ initial intake of green beans or the type of facial responses made during feeding.

Effects of Repeated Exposure on Acceptance and Liking

During the exposure period, the 2 treatment groups ate similar amounts of green beans (average daily intake: 68.6 ± 7.6 g for group GB and 61.9 ± 5.8 g for group GB-P); group GB-P ate, on average, 47.4 ± 15.8 g of peaches each day of the home-exposure period. As shown in Table 2, such repeated exposure with (group GB-P) or without (group GB) peaches led to significant increases in infants’ consumption of green beans (P < .001) and the rate at which they ate this food (P < .001). By dividing the amount of green beans consumed after exposure by the amount consumed before exposure for each infant (after/before), we found that the infants increased their intake of green beans almost threefold (2.7 ± 0.5-fold), on average. There was no significant interaction between infants’ feeding history and treatment group; both breastfed and formula-fed infants increased acceptance of green beans after the home-exposure period.

TABLE 2.

Infants’ Acceptance of Green Beans and Peaches Before and After 8-Day Exposure Period

| Group GB | Group GB-P | Both Groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green beans | |||

| Intake, mean ± SEM, g | |||

| Before exposure | 65.3 ± 12.5 | 52.3 ± 9.0 | 56.8 ± 7.3 |

| After exposure | 97.5 ± 17.3a | 91.6 ± 12.4a | 93.6 ± 10.0a |

| Rate of consumption, mean ± SEM, g/min | |||

| Before exposure | 4.8 ± 0.8 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.4 |

| After exposure | 6.6 ± 1.0a | 6.3 ± 0.7a | 6.4 ± 0.6a |

| Mothers’ rating of infants’ liking, mean ± SEM | |||

| Before exposure | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 7.1 ± 0.4 | 6.9 ± 0.3 |

| After exposure | 6.9 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 0.4 | 6.9 ± 0.3 |

| Peaches | |||

| Intake, mean ± SEM, g | |||

| Before exposure | 70.9 ± 14.0 | 67.7 ± 10.4 | 68.8 ± 8.3 |

| After exposure | 74.7 ± 15.1 | 79.2 ± 11.2 | 77.6 ± 8.9 |

| Rate of consumption, mean ± SEM, g/min | |||

| Before exposure | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.4 |

| After exposure | 5.8 ± 0.8a | 5.9 ± 0.6a | 5.8 ± 0.4a |

| Mothers’ rating of infants’ liking, mean ± SEM | |||

| Before exposure | 6.8 ± 0.5 | 7.1 ± 0.4 | 7.0 ± 0.3 |

| After exposure | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 6.4 ± 0.4 |

Group GB was fed green beans, and group GB-P was fed green beans and then peaches during the exposure period.

Significant at P < .05, compared with before exposure.

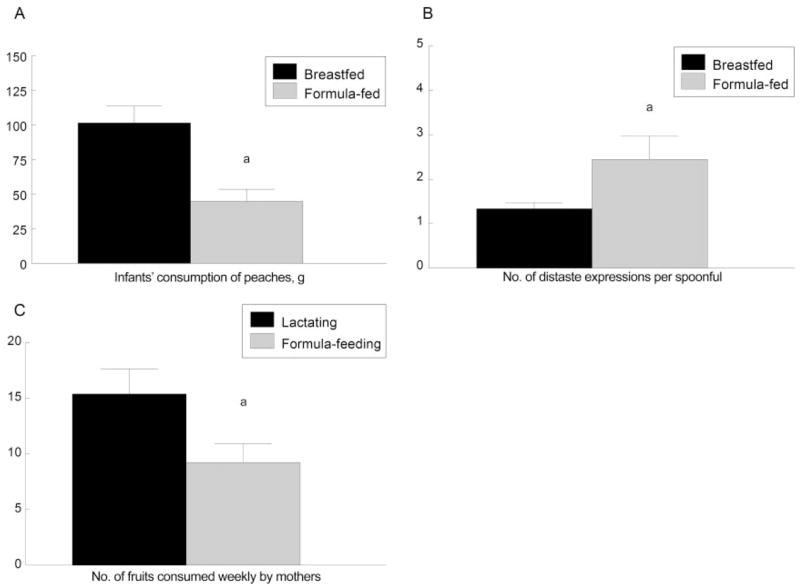

As shown in Fig 3, there was a significant interaction between the treatment group and the time for the types of facial expressions made during feeding of green beans (P < .04). Although there were no differences in the numbers of facial displays group GB infants made while eating green beans on the 2 test days at the Monell Chemical Senses Center, group GB-P infants, who were fed green beans and peaches, made fewer brow movements (P < .01), squints (P < .003), and upper-lip raises (P < .02) while eating green beans after, compared with before, the home-exposure period. Mothers were apparently unaware of this difference, because their ratings of enjoyment did not increase after the home-exposure period for either treatment group (Table 2).

FIGURE 3.

The cumulative number of brow movements (brow lowerers and inner brow raises combined), squints, upper-lip raises, and nose wrinkles made during green bean feeding, before and after the home-exposure period. Panel A shows data from group GB infants who were fed only green beans and panel B shows data from group GB-P infants who were fed both green beans and peaches during the 8-day home-exposure period. Infants in group GB-P displayed fewer brow movements (P < .02), squints (P < .01), and distaste expressions overall (P < .001) per spoonful of green beans after the 8-day home-exposure period, compared with before the exposure period.

Neither treatment group increased intake or displayed fewer distaste facial responses while eating peaches and the mothers’ rating of the infants’ enjoyment of peaches did not change after the home-exposure period. As shown in Table 2, both groups of infants ate the peaches at a faster rate (P < .005), which might indicate that they were becoming more efficient feeders.

DISCUSSION

Breastfeeding confers an advantage when infants first taste a food, but only if their mothers regularly eat similar-tasting foods. Breastfed infants were more accepting of peaches, when first introduced, than were formula-fed infants, as determined by intake, rate of consumption, and facial expressions. This enhanced acceptance of fruit could be attributable to more exposure to fruit flavors, because their mothers ate more fruits during lactation.

The frequency with which mothers need to eat a food to enhance their children’s liking remains unknown. The 1 randomized, experimental study revealed that breastfed infants whose mothers drank carrot juice 4 days/week during the first 2 months of lactation or the last trimester of pregnancy were more accepting of carrot-flavored foods, compared with breastfed infants whose mothers avoided carrots during this time period. Because carrot flavor and several other flavors are transmitted to amniotic fluid37 and mother’s milk,18,19 experiences with flavors before and after birth at the very least predispose young infants to respond favorably to those familiar flavors, which facilitates the transition from fetal life through the breastfeeding period to the initiation of a varied, solid-food diet.

Unlike a previous report,22 breastfeeding did not confer an advantage for green bean acceptance, either before or after exposure to this vegetable. The absence of an effect could be attributable to the low levels of exposure resulting from the low frequency of consumption by lactating mothers, effects of in utero exposure to green bean flavor for both breastfeeding and formula-feeding infants, or an interaction of the 2 factors. Because lactating mothers ate green beans and vegetables infrequently and at levels well below current recommendations,3 we hypothesize that experience with breastfeeding alone is not sufficient to enhance initial acceptance. Moreover, merely being exposed to the sight or smell of the food seemed to be insufficient to enhance acceptance, because, although formula-feeding mothers were more likely to eat green beans, their infants ate similar amounts of this food. As has been observed with older children,25 infants must taste the food to learn to like it.

Repeated opportunities to taste green beans enhanced acceptance to a similar extent for breastfed and formula-fed infants, a finding that is consistent with previous studies with infants16 and children.38,39 In the present study, we used commercial infant foods because of the consistency of flavor and quality control. What is not known is whether experience with such infant foods hinders the transition to eating fresh fruits or raw or cooked vegetables, which differ in flavor and texture. Findings from the present study suggest that, the more familiar the flavor experience, the better the likelihood of acceptance.

Although 8 exposures might be sufficient to increase willingness to consume green beans, it remains unknown how many exposures to green beans alone are needed to increase liking of this food. What did seem to affect the liking of green beans was whether the infants were fed peaches shortly after they ate green beans during the 8 days of exposure. These findings are consistent with previous work that revealed that the liking for a less-palatable food or beverage is enhanced when the food or beverage is associated with sweet tastes.26,27 How the timing of fruit introduction to infants’ diets, as well as that during the course of a meal, affects overall vegetable acceptance remains unknown. Specifically, we do not know whether feeding peaches before green beans would modify infants’ acceptance of the latter. Nevertheless, the present data do suggest that the hunger state of the child at the time of exposure may be important. Infants who were exposed repeatedly to green beans and peaches (group GB-P) did not eat more peaches after the home-exposure period. We hypothesize that, because the infants always ate peaches after the green beans and possibly when sated, they did not have the opportunity to learn that peaches alleviate hunger. This is consistent with a previous report in which adults who were exposed repeatedly to a novel fruit snack while satiated failed to increase consumption and had less desire to eat the snack.40 More study of how hunger state facilitates the development of liking for foods is warranted.

Eating peaches and green beans activated distinct, stereotyped, motor behaviors involving the orofacial region. There were individual differences in the display of these facial expressions while eating, which in some cases predicted the rate at which infants ate a particular food. Whether these individual differences reflect genetic variations in taste sensitivity remains unknown.41 Experience modified intake, but only those who experienced peaches after green beans seemed to like the taste of the green beans more after exposure. Although measures of liking are related to intake,42 they are governed by separate neural substrates30 and do not always change in tandem.30,43

Facial expressions, which indicate the intensity and hedonics of perceived sensations, might have evolved to signal that infants are eating something harmful and consequently might have been used by mothers to protect the infants. Given the evolutionary significance of the innate facial responses to certain tastes,33 it is not surprising that mothers are often hesitant to continue feeding a food they believe their infants dislike. We suggest that mothers should be encouraged to focus on their infants’ willingness to eat the food and not just on the distaste facial expressions made during feeding. Mothers should also be aware that, with repeated dietary exposure, it may take longer to observe changes in facial expressions than in intake.

CONCLUSIONS

The best predictor of how many fruits and vegetables children eat is whether they like the taste of these foods.44 Additional experimental studies, as well as randomized nutritional interventions that focus on maternal dietary habits during pregnancy and lactation and infant dietary experiences, are needed for better understanding of how liking for the flavor of foods develops.11

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HD37119. Dr Forestell was the recipient of a Canadian Institutes of Health research postdoctoral fellowship.

We acknowledge Jennifer Kwak, Amanda Jagolino, and Lindsay Morgan for expert technical assistance; Linda Kilby and the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children Center of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for help in recruiting mothers; Gerber Products for supplying the infant foods; and Dr Gary Beauchamp for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose

References

- 1.Bazzano L, He J, Ogden LG, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease in US adults: the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey epidemiologic follow-up study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:93–99. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Disease: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 916. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. 6. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox MK, Pac S, Devaney B, Jankowski L. Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study: what foods are infants and toddlers eating? J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(suppl):s22–s30. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mennella JA, Ziegler P, Briefel R, Novak T. Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study: the types of foods fed to Hispanic infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(suppl):s96–s106. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desor J, Maller O, Greene LS. Preference for sweet in humans: infants, children, and adults. In: Weiffenback JM, editor. Taste and Development: The Genesis of Sweet Preference. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1977. pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kajiura H, Cowart BJ, Beauchamp GK. Early developmental change in bitter taste responses in human infants. Dev Psychobiol. 1992;25:375–386. doi: 10.1002/dev.420250508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drewnowski A. Sensory control of energy density at different life stages. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glendinning JI. Is the bitter rejection response always adaptive? Physiol Behav. 1994;56:1217–1227. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butte N, Cobb K, Dwyer J, Graney L, Heird W, Rickard K. The Start Healthy feeding guidelines for infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:442–454. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas A. Programming by early nutrition: an experimental approach. J Nutr. 1998;128(suppl):401S–406S. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.2.401S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Wendy B, Ziegler PJ. Children’s food preferences: a longitudinal analysis. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1638–1647. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicklaus S, Boggio V, Chabanet C, Issanchou S. A prospective study of food variety seeking in childhood, adolescence and early adult life. Appetite. 2005;44:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, et al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2006;118:1323] Pediatrics. 2006;117:544–559. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mennella JA, Turnbull B, Ziegler PJ, Martinez H. Infant feeding practices and early flavor experiences in Mexican infants: an intra-cultural study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:908–915. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerrish CJ, Mennella JA. Flavor variety enhances food acceptance in formula-fed infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:1080–1085. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.6.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mennella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK. Prenatal and post-natal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e88. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/107/6/e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Mennella JA, Beauchamp GK. Maternal diet alters the sensory qualities of human milk and the nursling’s behavior. Pediatrics. 1991;88:737–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mennella JA. The chemical senses and the development of flavor preferences in humans. In: Hartmann PE, Hale T, editors. Textbook of Human Lactation. Amarillo, TX: Hale Publishing; 2007. pp. 403–413. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galloway AT, Lee Y, Birch LL. Predictors and consequences of food neophobia and pickiness in young girls. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:692–698. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mennella JA, Beauchamp GK. Developmental changes in the acceptance of protein hydrolysate formula. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1996;17:386–391. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199612000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan SA, Birch LL. Infant dietary experience and acceptance of solid foods. Pediatrics. 1994;93:271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooke LJ, Wardle J, Gibson EL, Sapochnik M, Sheiham A, Lawson M. Demographic, familial and trait predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption by pre-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:295–302. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Bounds W, Ziegler P, Reidy K. Do food-related experiences in the first 2 years of life predict dietary variety in school-aged children? J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34:310–315. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birch LL, McPhee L, Shoba BC, Pirok E, Steinberg L. What kind of exposure reduces children’s food neophobia? Looking vs. tasting. Appetite. 1987;9:171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(87)80011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein LJ, Nagai H, Nakagawa M, Beauchamp GK. Effects of repeated exposure and health-related information on hedonic evaluation and acceptance of a bitter beverage. Appetite. 2003;40:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(02)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Havermans RC, Jansen A. Increasing children’s liking of vegetables through flavour-flavour learning. Appetite. 2007;48:259–262. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mennella JA, Beauchamp GK. Mothers’ milk enhances the acceptance of cereal during weaning. Pediatr Res. 1997;41:188–192. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199702000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cannon DS, Best MR, Batson JD, Brown ER, Rubenstein JA, Carrell LE. Interfering with taste aversion learning in rats: the role of associative interference. Appetite. 1985;6:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(85)80046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berridge KC. Food reward: brain substrates of wanting and liking. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1996;20:1–25. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00033-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenstein D, Oster H. Differential facial responses to four basic tastes in newborns. Child Dev. 1988;59:1555–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soussignan R, Schaal B, Marlier L, Jiang T. Facial and autonomic responses to biological and artificial olfactory stimuli in human neonates: re-examining early hedonic discrimination of odors. Physiol Behav. 1997;62:745–758. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53–74. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ekman P, Friesen WV, Hagar JC. Facial Action Coding System on CD-ROM. Salt Lake City, UT: Network Information Research; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pliner P, Hobden K. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite. 1992;19:105–120. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90014-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carey WB, McDevitt SC. Revision of the Infant Temperament Questionnaire. Pediatrics. 1978;61:735–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mennella JA, Johnson A, Beauchamp GK. Garlic ingestion by pregnant women alters the odor of amniotic fluid. Chem Senses. 1995;20:207–209. doi: 10.1093/chemse/20.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wardle J, Herrera ML, Cooke L, Gibson EL. Modifying children’s food preferences: the effects of exposure and reward on acceptance of an unfamiliar vegetable. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:341–348. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wardle J, Cooke LJ, Gibson EL, Sapochnik M, Sheiham A, Lawson M. Increasing children’s acceptance of vegetables; a randomized trial of parent-led exposure. Appetite. 2003;40:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(02)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibson EL, Wardle J. Effect of contingent hunger state on development of appetite for a novel fruit snack. Appetite. 2001;37:91–101. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mennella JA, Pepino MY, Reed DR. Genetic and environmental determinants of bitter perception and sweet preferences. Pediatrics. 2005;115:216–222. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sclafani A, Ackroff K. Nutrient-conditioned flavor preference and incentive value measured by progressive ratio licking in rats. Physiol Behav. 2006;88:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forestell CA, LoLordo VM. Palatability shifts in taste and flavour preference conditioning. Q J Exp Psychol B. 2003;56:140–160. doi: 10.1080/02724990244000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Resnicow K, Davis-Hearn M, Smith M, et al. Social-cognitive predictors of fruit and vegetable intake in children. Health Psychol. 1997;16:272–276. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]