Abstract

Sacral chordomas are rare, slow-growing tumours that are amenable to surgery, but unfortunately often diagnosed late. The aim of the study was to identify presenting symptoms, which may aid diagnosis and reduce the treatment time. Forty-four patients were identified with sacral chordoma between 1989 and 2006. Clinical and pathological records were reviewed retrospectively to elicit the symptoms recorded prior to diagnosis, duration of symptoms, surgical treatment, size of tumour and survival. Eleven patients were excluded, leaving 33 patients in the study group. Thirty-one patients had chordomas arising from the sacrum and two patients from the coccyx. The mean duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis was 120 weeks (2.3 years), with a median of length of 104 weeks (two years) and range of 26 to 416 weeks (0.5 to eight years). The mean maximum tumour size at resection was 8.3 cm, with a mean volume of 614 cm3 (range 9–2,113 cm3). Pain, typically dull and worse with sitting, was the most common presenting symptom in 85% of patients. The classic symptoms of cauda equina (saddle anaesthesia, bladder or bowel dysfunction) occurred in 70% patients (23 patients). Sacral chordoma should be considered in cases of back pain with coccydynia, especially with neurological symptoms.

Résumé

Les chordomes sacrés sont des tumeurs d’évolution lente. On peut être amené à les prendre en charges chirurgicalement avec un diagnostic souvent tardif. Le but de cette étude est de mettre en évidence les symptômes qui peuvent aider à un diagnostic plus précoce et réduire ainsi les délais du traitement. Quarante-quatre patients présentant un chordome sacré ont été analysés entre 1989 et 2006. Les signes cliniques et les éléments pathologiques ont été analysés de façon rétrospective sur le plan diagnostic, notamment durée des signes, ainsi que sur le plan du traitement chirurgical, taille de la tumeur et courbe de survie. Onze patients ont été exclus 33 patients restent dans le groupe d’étude. Trente-et-un patients avaient un chordome jouxtant le sacrum et 2 jouxtant le coccyx. La durée moyenne des signes avant le diagnostic était de 120 semaines (2 à 3 ans) avec une médiane de 104 semaines (2 ans) de 26 à 416 semaines (0.5 à 8 ans). La taille moyenne de la tumeur après résection était de 8.3 cm avec un volume moyen de 614 cm3 (9 à 2113 cm3). La douleur, typiquement assez sourde est aggravée par la position assise, il s’agit du signe le plus habituel chez 85% des patients. Le signe classique de syndrome de la « queue de cheval » survient chez 70% des patients (anesthésie en selle et dysfonction vésicale) (23 patients). Le chordome sacré doit être évoqué dans les cas de douleurs lombaires avec coccydynie spécialement s’il existe des signes neurologiques.

Introduction

Sacral chordomas are slow-growing, gelatinous, extradural tumours with areas of haemorrhage and necrosis that often reach a large size and cause late-onset compressive neurological symptoms [1]. Though rare, with a reported incidence of approximately 1:1,000,000 [2], these tumours have a poor response to radiotherapy or chemotherapy, but are amenable to surgical treatment. Larger and more proximally located tumours may require excision of sacral nerve roots leading to incontinence, sexual dysfunction and motor weakness. Despite their low tendency to metastasise, a poor long-term prognosis is generally observed [3], and survival is determined by the success or failure of local control [4]; therefore, the advantage of early diagnosis would seem evident.

The unfortunate tale of delayed diagnosis of chordoma is a common story amongst patients referred to our unit and echoed by a ‘Personal View’ article previously published in the BMJ [5]. Two medical students (GE,RG) saw three such patients in one clinic and enquired if a pattern of symptoms could be identified that may facilitate earlier diagnosis.

Methods

Electronic patient records identified 44 patients with sacral chordoma between 1989 and 2006. The clinical and pathological records were carefully reviewed retrospectively to elicit the symptoms recorded prior to diagnosis, duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis, surgical treatment, size of tumour and survival. Patients were contacted by telephone where possible. Eleven patients were excluded, leaving 33 patients in the study group. Reasons for exclusion were:

Being referred with locally recurrent disease after initial treatment in another unit (six patients).

Insufficient data available from notes and patients were not contactable (five patients).

Patient diagnosed incidentally whilst asymptomatic (one patient).

After the interview, the recorded data on symptoms were categorised to allow statistical analysis to be performed using Microsoft excel and Statview statistical packages. Mann Whitney U testing was performed for symptoms and Kaplan Meier for survival analysis. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Thirty-three patients were in the study group (23 males, ten females) with a mean age of 60 years at diagnosis (range 28–95 years). Thirty-one patients had chordomas arising from the sacrum and two patients from the coccyx. The mean duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis was 120 weeks (2.3 years), with a median length of 104 weeks (two years) and a range of 26 to 416 weeks (0.5 to eight years). The mean maximum size of the tumour at resection was 8.3 cm, with a mean volume of 614 cm3 (range 9–2,113 cm3).

Three patients presented with metastases at diagnosis (two lung and one lymph nodes) and the ten year Kaplan meier survival was 63%; however, only 41% patients survived without local recurrence of the disease at ten years.

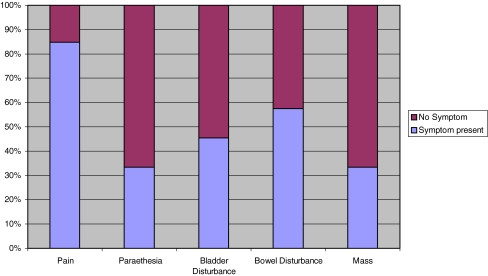

When symptoms were analysed they were categorised into pain symptoms, neurological symptoms, bladder symptoms, bowels symptoms and patient awareness of swellings. Pain was the most common presenting symptom with 85% of patients complaining of pain (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of patients with a major symptom for each category

The character of the pain was typically dull and worse with sitting (Fig. 2) and interestingly caused lower back pain as frequently as sacral pain. One of the classic symptoms of cauda equina (saddle anaesthesia, bladder or bowel dysfunction) occurred in 70% patients (23 patients).

Fig. 2.

Characteristics of pain symptoms

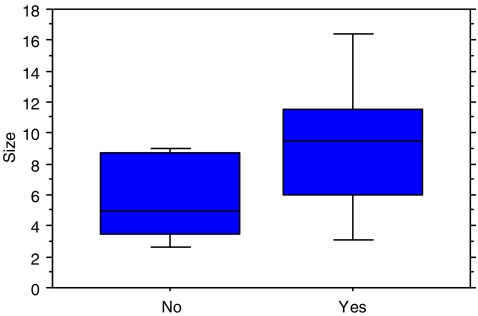

There was a significantly larger volume of tumour at resection in patients with neurological compressive symptoms (parathesia, bladder or bowel dysfunction). Patients with compressive symptoms had a mean resection size of 9.3 cm and those without had a mean of 5.9 cm (P=0.045, Fig. 3). There was no correlation between the duration of symptoms and size of tumour at resection. Neither was there any correlation between the duration of symptoms and neurological compression.

Fig. 3.

Box plot for resection size for patients with compressive neurological symptoms

Discussion

Chordoma is a rare condition; however, there are a number of symptoms that correlate strongly with a sacral pathology. Symptoms such as pain accompanied with neurological symptoms including parasthesia, urinary or bowel disturbances and weakness in the lower limbs should all be recognised as clinical red flag signs and are strong indicators of sinister pathology worthy of further investigation.

It became apparent during the study that most of the patients had undergone multiple investigations attempting to exclude differential diagnoses prior to the diagnosis of chordoma. Early diagnosis may allow the detection of smaller, more easily resectable tumours with less subsequent morbidity. Chordomas are generally slow-growing tumours and excision of the tumour may be curative in the face of few alternative therapies. Excision of the tumour if large or proximal may require excision of affected sacral nerve roots, which results in permanent incontinence, sexual dysfunction and motor weakness.

The majority of patients presenting in our unit unfortunately echoed the experiences of the patient previously featured in the BMJ [5], with the majority suffering a delayed diagnosis until further investigations led to an MRI scan. Back pain is a notoriously unspecific symptom, with a long list of possible causes, and the majority of doctors will see a huge number of cases of lower back pain each year, most of which will be due to mechanical causes, such as muscular pain. However, in the authors experience, back pain in combination with neurological symptoms, pain persisting and gradually worsening over time and coccyx pain that fails to resolve should prompt a doctor to initiate further investigations including plain X-ray or MRI scans. Recently published guidelines for investigation of back pain would recommend further investigation in patients with the above symptoms, whether or not the underlying diagnosis is of chordoma [6].

In the series above, one patient underwent a transurethral prostatectomy following urinary disturbances, but remained symptomatic following surgery. He was seen by many health care professionals from different medical subspecialities; however, it was not until his GP organised an MRI scan that an underlying sacral chordoma was detected.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of chordoma or a primary sacral tumour remains uncommon, however, should be considered in patients with dull lower back or coccygeal pain (typically worse on sitting) especially if associated with an alteration of bowel or urinary habits. Chordoma and other sacral tumours are curable with surgery and early diagnosis may lead to preservation of bladder, bowel, motor and sexual function (Table 1).

Table 1.

Breakdown of symptoms per category

| Frequency | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Neurological | Bladder | Bowel | Mass | |||||

| Sitting | 11 | Saddle parathesia | 7 | Incontinence | 9 | Constipation | 14 | Sacral | 9 |

| Lower back | 13 | Leg parathesia | 6 | Outflow obstruction | 7 | Incontinence | 4 | Buttock | 3 |

| Sacral | 13 | Motor weakness | 2 | Erectile dysfunction | 1 | Rectal discharge | 1 | ||

| Leg | 6 | Tenesmus | 1 | ||||||

| Buttock | 5 | ||||||||

| Perianal | 3 | ||||||||

| Perineal | 3 | ||||||||

| Night | 3 | ||||||||

References

- 1.Hoskin PJ, Neal AJ (2003) Clinical oncology 3rd edn, basic principles+practice: CNS tumours. Arnold, Hodder Headline Group, London, p 161

- 2.McMaster ML et al (2001) Chordoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1973–1995. Cancer Causes Control 12:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Baratti D, Gronchi A, Pennacchioli E, Lozza L, Colecchia M, Fiore M, Santinami M (2003) Chordoma: natural history and results in 28 patients treated at a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol 10:291–296 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bissett D, Cassidy J, Spence RAJ (2004) Oxford handbook of oncology: bone and soft tissue malignancies. Oxford University Press, p 525

- 5.Anonymous (2000) Why a massive tumour went undetected. BMJ 320:523 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Thomas S (2006) Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ 332:1430–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]