Abstract

A three-dimensional model of the left acetabulum with inserted threaded cup has been generated, based on the finite element method, to calculate stress patterns in the standing phase during walking. In this study, a hemispherical cup with sharp threads, a parabolic cup with flat threads and a conical cup with sharp threads were analysed and compared. Stress patterns in both implant components and adjacent bony structures were calculated in a directly postoperative situation. The different cups were found to induce different stress patterns, deformations and shifting tendencies. The inlays deform notably and show characteristic rotational movement patterns together with the shell. The inclination angle increases in the hemispherical cup and decreases in the parabolic cup. The conical cup levers outward almost parallel to the bone stock by approximately 0.05 mm. The pole surfaces of the various cups – especially the very convex area next to the threads – induce increased compressive stress in the superior section of the acetabular base. This is increased by a factor of three in the conical cup in comparison to the hemispherical cup and less so in comparison to the parabolic cup. This study illustrates that three-dimensional stress calculations are suitable for procuring additional biomechanical information to augment clinical studies, for evaluating implants and for establishing stability prognoses, especially for newly developed prototypes.

Résumé

Une étude basée sur les éléments finis à partir d’un modèle tridimensionnel d’une hanche gauche a permis de calculer les contraintes générées sur une cupule vissée durant la marche. Pour cette étude, deux cupules différentes ont été analysées, une cupule hémisphérique vissée et une cupule vissée de type conique. Ces différentes cupules entraînent des contraintes différentes. L’angle d’inclinaison augmente dans les cupules hémisphériques et diminue dans les cupules de type parabolique conique. Le bras de levier des cupules de forme conique est pratiquement parallèle à 0,05 mm près au stock osseux. Le contact polaire supérieur de ces différentes cupules entraîne, notamment dans les zones les plus convexes des spires, des augmentations de contraintes au niveau de la partie supérieure de l’acétabulum. Ce phénomène est multiplié par trois dans les cupules coniques en comparaison aux cupules hémisphériques. L’étude tridimensionnelle de ces cupules est fiable, donnant des informations biomécaniques supplémentaires pour les études cliniques, pour l’évaluation des implants et permet de faire un pronostic sur la stabilité de ceux-ci, notamment lorsque l’on développe un nouveau prototype.

Introduction

Cementless hip systems utilize two types of cups, pressfit or threaded cups, both of which come in varying geometrical designs. These are usually hemispherical, parabolic, conical or combinations thereof [17]. Both types of cementless systems procure primary stability through form-fitting and frictional connection.

Secondary stability, which is of great importance for the patient, is based on mechanically satisfactory and long-lasting biological integration of the implant. Several factors influence secondary stability, such as primary stability, surgical preparation, cup positioning, cup material and surface structure, postoperative loading and, finally, the pattern of mechanical stress within the implant-bone-interface during functional loading. The physiological distribution of mechanical stress according to Wolff’s transformation principle [17, 21] is a major factor that influences long-term results. However, due to the biomechanics of the hip joint, implants do not uniformly integrate with physiological density, but instead obtain semi-integration (islands of bony ongrowth) or integrate with sub-physiological density [5, 20].

Local trabecular fixation of threaded cups was observed by Effenberger et al. [2] and subsequently calculated by Witzel [17] using a two-dimensional model.

New bony formations are typical in the area of the threads and at the acetabular base and transmit joint loading forces into adjacent bone structures. Calculations show that these areas are characterized by distinct compressive stress vectors.

With the development of finite element methods (FEM), compressive stress patterns can be determined. Initially, due to software insufficiencies and limited computer capacity, only two-dimensional (2-D) calculations using one implant and one acetabular section were possible [10]. However, with time, it was posibble to systematically supplement 2-D models with other pelvic structures [9, 17]. One major drawback of all 2-D models is that they have the same source of error because C-shaped acetabular sections which act too flexibly under loading are used for analysis instead of ring-shaped sections.

If neither geometrical nor material prerequisites are complied to the results, the latter are not biomechanically viable. Erroneous results will be also obtained if the surfaces of friction pairs are not taken into consideration. Consequently, a realistic three-dimensional (3-D) model that includes friction and contact surfaces and material parameters should be used for stress analysis.

Initial results for unstructured hemispherical pressfit cups based on this 3-D concept have been published [12, 18]. The study reported here presents the results for non-integrated acetabular threaded cups.

Material and methods

Based on the information described in the Introduction, our 3-D stress analysis was conducted by generating a 3-D volumetric model of the left pelvic half with a non-integrated threaded cup. The model was divided into 85.996 finite elements in a tetrahedral shape, with each tetrahedral shape having ten nodes. This model is positioned in the sacroiliac joint. The joint force which is produced during the standing phase during walking is transferred from the prosthetic head through the polyethylene inlay and shell into the pelvis. Additional compensatory force induction occurs via the os ilium, os ischii, spina ischiadica and the superior rim of the acetabulum. The four components are set using the following parameters:

pelvis: Young’s modulus E = 4 kN/mm2, Poisson ratio ν = 0.1;

cup: E = 110 kN/mm2, ν = 0.3;

polyethylene (PE) inlay: E = 0.5 kN/mm2, ν = 0.45;

prosthetic head: E = 190 kN/mm2, ν = 0.3.

Contact elements are placed between the prosthetic head and the PE inlay, and between the inlay and shell, which – as under in vivo circumstances – enable pressure and shear stress (free option of friction coefficients) but do not transfer tensile forces, because a gap occurs during tensile stress. By adding contact elements, it is possible to calculate relative movement. The surfaces between the shell and threads and pelvis are prepared in a similar manner for analysis of directly postoperative situations. Therefore, stable situations, relative movement and gap formation can be calculated. Direct node coupling between the components is used only for simulating consolidated situations.

Based on the FEM calculation, ANSYS software (ANSYS, Canonsburg, Pa.) was used for stress analysis. The virtual implanted cup can be of any shape. In this study we analyse a hemispherical, a parabolic and a conical cup shape:

hemispherical cup: sharp threads, thread depth (t)=2.2 mm, pitch (P)=3.5 mm;

Parabolic cup: flat threads, t = 2.8 mm, P = 5.0 mm;

Conical cup: sharp threads, t = 3.0, P = 5.0 mm.

All calculations were made using a high power computer system (Power Challenge XL12/R8000; Silicon Graphics, Mountain View, Calif.) in the Electronic Data Processing Centre of the Ruhr University, Bochum. The advantage of the FEM based on 3-D calculations in comparison to planar photoelasticimetry or to wire strain gauging is the procurement of volumetric information on both stress patterns and relative movement at interface surfaces. Structural movement, such as relative movement of cup, PE inlay and head, are assessed by contour superposition of the non-deformed model against the deformed model and – as for stress values – calculated for each node. In addition, after complete calculation, the model can be cut into an unlimited number of sections in order to calculate stress patterns within these sections. It is, of course, possible to procure stress fields across the complete surface of the model and of the contact surfaces.

A knowledge of 3-D mechanical stress patterns according to the Wolff transformation principle is prerequisite for assessing osseous reactions in a bony implant bed and for interpreting radiologically observed osseous reconstruction in the pelvis after in vivo implantation.

Compromises in terms of simplified model geometry and relatively undifferentiated material values are necessary because of the time required for the calculations and because of the limited number of nodes (128,000) due to software limitations. All structures are considered to be homogeneous, isotropic and linearly elastic. Initial stress that would occur during a theoretical screw-in process is disregarded. Principal stress patterns can be displayed separately. These are colour-coded in the sections of the model for repeat identification, whereby a certain range of stress is accorded a specific colour. A stress path with relatively high values can also be characterized by a single colour. The results of these FE-calculations can be quantitatively graded by radiographs, microradiographs and histological analysis [2].

Results

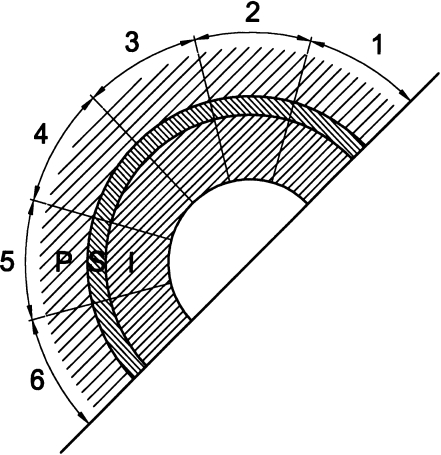

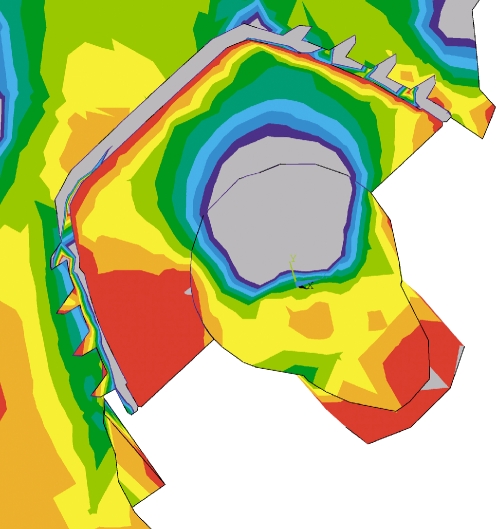

The 3-D model of the left pelvis is divided into two planes in order to assess stress fields inside the model. The plane (Fig. 1) is produced by an orientating section through the pelvis from the midpoint of the hip joint to the sacroiliac joint. Stress analysis in this orientating section (OS; Fig. 2) procures information on stress patterns from the femoral head to the sacrum. Effects caused by the capsular-ligament-system that inserts at the cranial rim of the acetabulum can also be assessed.

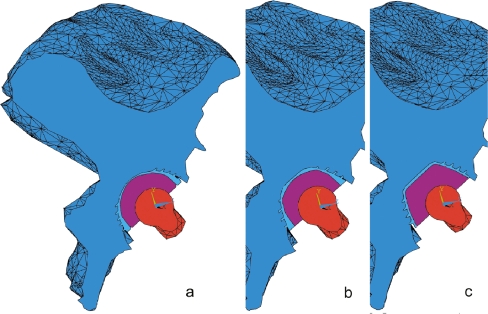

Fig. 1.

Three-dimensional (3-D) computational model of a left pelvis with a non-integrated threaded cup and prosthetic femoral head. Any number of sections through the model can be created for stress analysis; in this case, an orientating section between the center of the prosthetic head to the sacroiliac joint. a Hemispherical threaded cup, b parabolic threaded cup, c conical threaded cup

Fig. 2.

View of acetabulum (P) and cup (S) with inlay (I) with regions 1 to 6 per section. The orientating section (OS) contains regions OS 1 – OS 6

It should be noted that due to the orientation of the sections, the figures do not generally depict the pole openings of the cups and that the straight shell of the conical cup seems slightly curved.

Hemispherical cup

In this case, the implant is not consolidated; the cup and threads are form-fitting. Only pressure and shear forces can be transferred from implant to pelvis; however, as the calculations show, bony structures, implant shell and thread teeth are subjected to partial bending under tensile stress. Figure 3 depicts results after the calculation of compressive stress in the OS: a principal stress path leads from the femoral head to the sacroiliac joint. Values for compressive stress (negative sign) are between −1 N/mm2 on the bony acetabular side and more than −4.5 N/mm2 on the bony sacral side. In the superior region of the acetabulum, in area 2 (OS 2; Fig. 2), compressive stress is up to −3.5 N/mm2 in the area of the stressed rim of the acetabulum and the thread teeth and shows a decreasing tendency towards the first medial thread tooth (down to −1.5 N/mm2). Compressive stress is reduced to between −1 and −2 N/mm2 in the area of the bony base of the acetabulum (OS 3 and 4), which is impinged by the pole of the cup. Towards the inferior part of the acetabulum near the cup, compressive stress continuously decreases to almost zero (OS 6). Only the tips of the threads induce local stress of about −1 to −1.5 N/mm2.

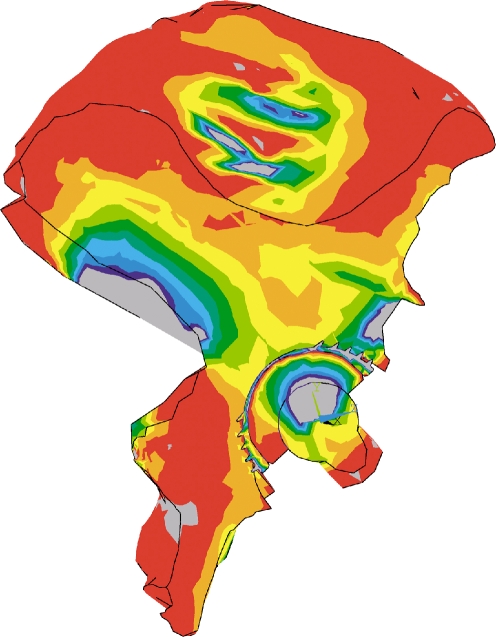

Fig. 3.

Hemispherical threaded cup. Compressive stress pattern in the orientating section

The analysis of deformation and relative movement of the superior area of the threaded cup depict a compression of the PE inlay between the prosthetic head and shell and almost no gap formation between the shell, threads and the acetabulum. Inferiorly, the prosthetic head notably pushes into the PE inlay with the formation of a lateral gap. Relative to the shell, the PE inlay rotates inferiorly outward. Again inferiorly, shell and thread are levered out of the acetabulum; at the same time, laterally, the teeth flanks show a tight fit. This inferior deformation corresponds to a tendency of the hemispherical cup to rotate outward in the lateral direction with an increasing inclination angle.

Parabolic cup

The results for the parabolic threaded cup in the orientating section show a broad compressive stress field progressing from the convex pole surface to the sacroiliac joint. Compressive stress values range from −1 to more than −4.5 N/mm2. In the superior area of the acetabulum (Fig. 4) compressive stress is up to −4.5 N/mm2 between the stressed acetabular rim and the lateral thread tips (OS 1), which decreases to −2 N/mm2 at the first medial thread tooth. Compressive stress is between −1 and −2.5 N/mm2 at the base of the acetabulum and decreases to −1 N/mm2 inferiorly near the cup. Here the thread tips cause local stress of up to −3.5 N/mm2.

Fig. 4.

Parabolic threaded cup. Compressive stress pattern in the orientating section

The analysis of deformation and relative movement in the superior part of cup and thread show an even, osseous form-fitting closure and notable compression of the PE inlay. Inferiorly, penetration of the prosthetic head is especially notable, with the formation of a gap between the PE inlay and shell. The inferior thread teeth shows osseous closure on the medial sides and gaps at the tips and lateral flanks, indicating that there is a tendency to rotate to the right (decrease of the inclination angle).

It is notable that the superior thread teeth and the second inferior thread tooth are supported in the medial direction with compressive stress of up to −2 N/mm2.

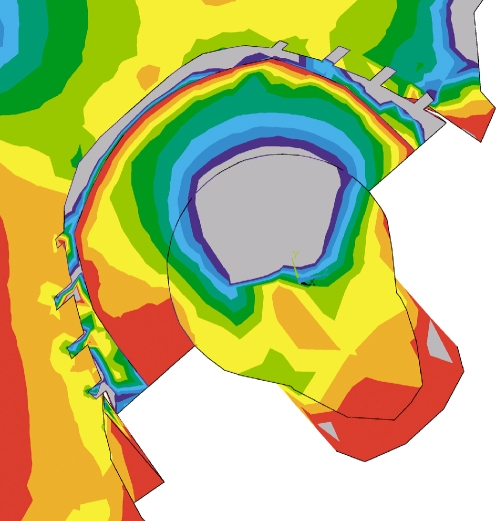

Conical cup

The orientating section shows a principal stress path that progresses in the direction of force induction through the prosthetic head, inlay and the superior convex pole surface into the acetabulum. The stress path divides in the middle of the acetabulum and progresses medially to the sacroiliac joint and laterally to the superior acetabular rim. Inferiorly, the cup is subjected to extensive pressure. Figure 5 depicts the compressive stress patterns. The acetabular base shows a very heterogeneous compressive stress value ranging from −0.5 to −3.0 N/mm2. The bony bed of the convex pole surface has additional increased stress peaks. Compressive stress is −3.0 N/mm2 in the inferior area of OS 4 and increases to more than −4.5 N/mm2 superiorly in OS 3. The superior part of the cup and thread teeth induces compressive stress that decreases markedly in the lateral direction (OS 1) to 0 N/mm2. Inferiorly, extensive compressive stress of up −3.0 N/mm2 stretches from OS 4 and OS 5 to OS 6. In the second and third thread bases, compressive stress increases up to −4.0 N/mm2.

Fig. 5.

Conical threaded cup. Compressive stress pattern in the orientating section

Deformation analysis shows that, superiorly, the prosthetic head pushes into the PE inlay. The inlay altogether is subject to an overall even compression between the head and shell. The cup and threads evenly compress the adjacent acetabular bed. Inferiorly, the shell and thread teeth are levered almost parallel out of the acetabulum at a tenfold magnification of the true shifting. In the lateral OS 6 region, the inlay levers out of the shell, and the prosthetic head levers out of the inlay.

Discussion

Several studies have been published [1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 22] on second-generation threaded cups [3] in terms of long term-survival rates of 90–100% after 10–16 years (Table 1). Provided that an implant has an ideal position and has fully penetrated the bone, 3-D FE analyses show that the compressive stress of spherically shaped implants is the most evenly distributed. Conical implants have a concentration of stress distribution at the superior pole. As demonstrated through 3-D analysis, a spherical implant provides an ideal stress distribution; consequently, this shape is being increasingly incorporated into current implant designs as biconical, parabolic and spherical shapes.

Table 1.

Results of threaded cups in primary hip arthroplasty

| Implant-Design/Type | Author | FU/OPa | Age of patient (years) | Follow-up (years) | Revision rate (%) | Survival rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conical | |||||||

| Zweymüller | Pospischill and Knahr [13] | 103/152 | 59.2 | 14.4 | 2.9 | 95.6 | 15 years, aseptic loosening |

| 10.7 | revisions of insert infection | ||||||

| 1 | |||||||

| Zweymüller | Vervest [16] | 142/221 | 65 | 12 | 96 | 12 years | |

| Zweymüller | Pieringer et al. [11] | 75/100 | 58 | 12.5 | 96.9 | 7 aseptic loosenings | |

| Zweymüller | Effenberger et al. [4] | 147/220 | 65.8 | 9.2 | 3.1 | 95 | 10 years |

| 89 | 13 years | ||||||

| 4 | 10 revisions of insert | ||||||

| Hemispherical | |||||||

| Tropic (HA coated) | Reikeras and Gunderson [15] | 128 | 48 | 13 | 91 | 16 years | |

| Trident (HA coated) | Epinette et al. [6] | 164/330 | 61 | min. 10 | 1.2 | 98.8 | 4 revisions of the cup |

| Biconical | |||||||

| Bicon | Zweymüller [22] | 203/322 | 59 | 10.1 | 0.6 | 99.2 | 2 revisions (loosening, cup fracture) |

| Parabolical | |||||||

| Hofer-Imhof | Ramsauer and Dorn [14] | 133/211 | 67 | 9.5 | 95.3 | 11.8 years | |

| 2 | 5 revisions of the cup |

aNumber of patients in the follow-up (FU)/number of patients operated on (OP)

To date, 3-D calculations using an entire half of the pelvis with integrated prosthetic components have only been conducted using hemispheric pressfit cups [12, 18], and calculations of stress patterns with threaded cups have only been conducted using parts of the pelvis [8]. Based on the FEM with improved software and increased computer capacity, it is now possible to generate more comprehensive models and to differentiate between directly postoperative and consolidated situations. This is of particular importance in terms of obtaining realistic information on the induction and transfer of stress in initially stable implants that have not yet consolidated because, according to Wolff [21] and Witzel [17], postoperative stress patterns influence long-term integration and secondary stability. Calculations of consolidated implants remain unsatisfactory because these are based on a situation of uniform implant-bone integration instead of a situation with patches of osseous ongrowth or with widespread ongrowth of differing quality [20]. Furthermore, as software and hardware capacities improve, calculations with thin cortical layers will be possible, which are necessary for more applicable results. At the present time, such calculations are only possible with less comprehensive smaller models [19].

A comparison of our results shows that each implant has a specific effect on the bony bed. As the OS demonstrate, in a directly postoperative situation, hemispheric and parabolic cups induce a notable stress path into the sacroiliac joint and the lateral acetabular roof. Compressive stress induction is advantageous in the OS 1–3 regions (Figs. 3, 4, 5) but inferiorly less beneficial in OS 5–6. In this latter area, there is notable compressive stress induction only at the tips of the threads, an effect that is more apparent in parabolic cups than in hemispherical cups. The conical cup shows advantageous stress induction in this region (Fig. 5).

When local compressive stress concentrations in the bony bed at the superior pole curve (OS 3) are compared, the hemispherical cup has the smallest values. These are larger in the parabolic cup and higher by a factor of three in the conical cup and are, therefore, reciprocally proportional to the pole curvature radius (factor 1/3).

The pole surfaces also induce differing stress patterns. Local compressive stress peaks increase from the hemispherical cup to the conical cup by a factor of three with increasing inhomogeneity. An inhomogeneous stress pattern has the risk that local rod-like trabecular structures will evolve in place of stable, flatter integrative structures that are also more resistant to stochastic stress.

The inlays are subjected to notable deformations by the prosthetic head, to hydrostatical stress near the cup, and – together with the shell – to characteristic translations and outward or inward rotations. With insufficient form-fitting, hemispherical cup inlays and shells rotate inferiorly outward at an increased inclination angle. Parabolic cup inlays also rotate inferiorly outward, but in the opposite direction as the shells, which lose stability and have a decreased inclination angle. Conical cup inlays produce a gap at the acetabular rim without rotational movement; the cup levers itself out parallel to the osseous bed without rotating. Gap width is, on average, 0.05 mm and larger than the gaps of the other cups.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Electronic Data Processing Center of the Ruhr University, Bochum for mainframe calculations, also Prof. Dr.-Ing. Welp at the Institute for Construction Technique for donating software and additional computer and printer capacity, also engineers Dr. Ing. Weiss and Dipl. Ing. Wittenschläger for their effective support.

References

- 1.Delaunay CP, Kapandji AI (2004) Einsatz der Zweymüller und Alloclassic-CSF sandgestrahlten Titanschraubpfannen in der primären totalen Hüftendoprothetik. In: Effenberger H (Hrsg). Schraubpfannen. Effenberger, Grieskirchen, pp 205–210

- 2.Effenberger H, Böhm G, Huber M, Lintner F, Hofer H (2000) Experimental study of bone-implant contact area with a parabolic acetabular component (Hofer-Imhof). Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 120:160–165 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Effenberger H, Imhof M, Witzel U (2001) Gewindedesign von Schraubpfannen. Z Orthop 139:428–434 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Effenberger H, Ramsauer T, Dorn U (2004) Factors influencing the revision rate of Zweymueller acetabular cup. Int Orthop 28:155–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Engh Ch, Zettl-Schaffer KF, Kukita Y, Sweet D, Jasty VM, Bragdom C (1993) Histological and radiographic assessment of well functioning porous-coated acetabular components. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 75:814–824 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Epinette JA, Manley MT, D’Antonio JA, Edidin AA, Capello WN (2003) A 10-year minimum follow-up of hydroxyapatite-coated threaded cups: clinical, radiographic and survivorship analyses with comparison to the literature. J Arthroplasty 18:140–148 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Grübl A, Chiari C, Gruber M, Kaider A, Gottsauner-Wolff F (2002) Cementless total hip arthroplasty with a tapered, rectangular titanium stem and a threaded cup. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 84-A:425–431 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Huiskes R (1987) Finite element analysis of acetabular reconstruction. Acta Orthop Scand 58:620–625 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Levenstone M, Beaupre GS, Schurmann DJ, Carter DR (1993) Computer simulations of stress-related bone remodelling around non cemented acetabular components. J Arthroplasty 8:595–605 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Peterson DR, Crowninshield RD, Brand RA, Johnston RC (1982) An axisymmetric model of actabular components in total hip arthroplasty. J Biomech 15:305–315 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Pieringer H, Auersper V, Griessler W, Böhler N (2003) Long-term results with the cementless Alloclassic brand hip arthroplasty system. J Arthroplasty 18:321–328 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Pfleiderer M (1997) Mikrobewegungen zementfreier Hüftpfannen im Beckenknochen. Fortschr.-Ber., VDI, Düsseldorf

- 13.Pospischill M, Knahr K (2005) Cementless total hip arthroplasty using a rectangular tapered stem. Follow-up for ten to 17 years. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 87:1210–1215 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ramsauer T, Dorn U (2004) Prinzip und Ergebnisse mit der Hofer-Imhof Schraubpfanne. In: Effenberger H (Hrsg.) Schraubpfannen. Effenberger, Grieskirchen, pp 275–278

- 15.Reikeras O, Gunderson RB (2006) Long-term results of HA coated versus HA coated hemispheric press fit cups: 287 hips followed for 11 to 16 years. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 77:535–542 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Vervest TM, Malefijt Jde M, Hendriks JC, Gonsens T, Bonnet M (2005) Ten to twelve-year results with the Zweymuller cementless total hip prosthesis. J Arthroplasty 20:362–368 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Witzel U (1996) Mechanische Integration von Schraubpfannen. Ein Beitrag zur hüftendoprothetischen Versorgung. Thieme, Stuttgart

- 18.Witzel U (1998) Distribution of stress in a hemispherical RM cup and its bony bed. In: Bergmann EG (Hrsg) Hip-joint surgery, the RM cup. Einhorn-Presse Verlag, Reinbek, pp 29–41

- 19.Witzel U, Jackowski, Jöhren P (1998) Analyse der Spannungsverteilung in spongiösen Sinus-Augmentat nach sekundärer Implantation mit Hilfe der finiten Elemente (FEM). Straumann, Freiburg

- 20.Witzel U (2000) Die knöcherne Integration von Schraubpfannen. In: Perka C, Zippel H (Hrsg.): Pfannenrevisionseingriffe nach HTEP – Standards und Alternativen. Einhorn-Presse Verlag, Reinbek, pp 11–16

- 21.Wolff J (1892) Das Gesetz der Transformation des Knochens. Hirschwald, Berlin

- 22.Zweymüller K (2006) Redesigned threaded, double-cone titanium cups yield excellent mid-term results. Orthopedics 29:809–810 [DOI] [PubMed]