Abstract

Intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) signals were studied with spatial resolution in bovine vascular endothelial cells using the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator fluo-3 and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Single cells were stimulated with the purinergic receptor agonist ATP resulting in an increase of [Ca2+]i due to intracellular Ca2+ release from inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-sensitive stores. ATP-induced Ca2+ release was quantal, i.e. submaximal concentrations mobilized only a fraction of the intracellularly stored Ca2+.

Focal receptor stimulation in Ca2+-free solution by pressure application of agonist-containing solution through a fine glass micropipette resulted in a spatially restricted increase in [Ca2+]i. Ca2+ release was initiated at the site of stimulation and frequently propagated some tens of micrometres into non-stimulated regions.

Local Ca2+ release caused activation of capacitative Ca2+ entry (CCE). CCE was initially colocalized with Ca2+ release. Following repetitive focal stimulation, however, CCE became detectable at remote sites where no Ca2+ release had been observed. In addition, the rate of Ca2+ store depletion with repetitive local activation of release in Ca2+-free solution was markedly slower than that elicited by ATP stimulation of the entire cell.

From these experiments it is concluded that both intracellular IP3-dependent Ca2+ release and activation of CCE are controlled locally at the subcellular level. Moreover, redistribution of intracellular Ca2+ stored within the endoplasmic reticulum efficiently counteracts local store depletion and accounts for the spatial spread of CCE activation.

Stimulation of vascular endothelial cells with the vasoactive agonist adenosine triphosphate (ATP) evokes a rise in intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). ATP acts through purinergic receptors to stimulate the formation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and subsequent Ca2+ release from intracellular storage sites of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Chen et al. 1996; Madge et al. 1997). Depletion of the IP3-sensitive Ca2+ store results in Ca2+ entry from the extracellular environment, which plays a key role in maintaining the ER Ca2+ load (Schilling et al. 1992; Madge et al. 1997). The activation mechanism of this ‘capacitative Ca2+ entry’ (CCE) pathway residing in the plasma membrane and its molecular identity in endothelial cells remains elusive. Models explaining the signalling mechanism which functionally links the ER Ca2+ store to stimulation of Ca2+ entry across the plasma membrane postulate either the involvement of a diffusible messenger or a direct physical link between an ER Ca2+-sensing protein and the plasma membrane CCE pathway (for a review see Berridge, 1995; see also Parekh & Penner, 1997; Putney, 1997; Holda et al. 1998). Recent reports of CCE in Xenopus laevis oocytes (Petersen & Berridge, 1996; Jaconi et al. 1997) have revealed a colocalization of Ca2+ entry with the sites of IP3-induced Ca2+ release. A similar membrane-restricted regulation of the Ca2+ entry pathway has been reported for polarized airway epithelial cells (Paradiso et al. 1995). Moreover, CCE but not the agonist-induced Ca2+ release was suppressed in endothelial cells treated with cytochalasin D to disrupt the actin microfilaments (Holda & Blatter, 1997). Taken together, these findings suggest that CCE may be controlled in a subcellularly restricted fashion. Elements of the cytoskeleton might participate either directly or by providing a structural scaffold that ensures the physical proximity of the two membranes involved in the signalling mechanism.

In the present study, we have used confocal Ca2+ imaging and a focal agonist application system to investigate the spatial interrelation between agonist-induced Ca2+ release from the ER and CCE across the plasma membrane in cultured vascular endothelial cells. The results suggest that Ca2+ release and CCE are controlled through a subcellularly restricted mechanism which does not involve ‘long-range’ intracellular messengers. Moreover, intra-ER redistribution of stored Ca2+ from non-stimulated regions of the cell to the site of Ca2+ release prevents local store depletion and is responsible for activation of CCE at sites distant from Ca2+ release.

METHODS

Cell culture and solutions

Experiments were performed on single cultured CPAE vascular endothelial cells in non-confluent cultures. The CPAE cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) was originally derived from calf pulmonary artery endothelium. Details of the culture conditions have been published previously (Holda & Blatter, 1997; Hüser & Blatter, 1997). Cells from passages 3–6 were used for experimentation. The cells were superfused continuously with standard physiological salt solution, containing (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose and 10 Hepes, adjusted to pH 7.3 with NaOH. In the Ca2+-free solution CaCl2 was omitted. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (20–22°C).

Ca2+ measurements

Endothelial cells were loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator fluo-3 by exposure to 5 μm of the membrane permeant acetoxymethyl ester of the dye (fluo-3 AM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 20 min at 37°C. Following transfer of the coverslip onto the stage of an inverted microscope (Axiovert 100, Carl Zeiss, Germany) equipped with a × 40 objective lens (Plan-Neofluar, oil immersion, 1.3 NA, Carl Zeiss), the cells were washed for 10 min with standard physiological salt solution to allow sufficient time for de-esterification. The microscope was attached to a confocal laser scanning unit (LSM 410, Carl Zeiss). The fluo-3 fluorescence was excited using the 488 nm line of an argon-ion laser while emitted fluorescence was recorded simultaneously at wavelengths ≥ 515 nm. In the recordings shown, changes in Ca2+-sensitive fluorescence were averaged over small subcellular regions of interest (ROIs), about 200–400 μm2 in size. Relative changes in [Ca2+]i were expressed as changes of fluo-3 fluorescence normalized to resting fluorescence (F/F0).

For staining the ER, cells were incubated in 500 nM DiOC6 (Molecular Probes) for 5 min and subsequently washed in standard physiological salt solution for 10 min. Fluorescence was excited at 488 nm and simultaneously recorded at wavelengths ≥ 515 nm.

Focal application system

During experimentation the cells were placed in the laminar flow from a fast solenoid-operated perfusion system allowing rapid exchange of the extracellular solution (half-time, t0.5≡ 100 ms). For focal application of agonist (ATP)-containing solution a glass micropipette (tip diameter, 1–3 μm) was positioned close to a cell process, which was located downstream of the cell body with regard to the direction of bulk flow. The ATP solution was ejected by pressure application. Control experiments using fluorescent solutions revealed that focal stimulation at any pressure setting was restricted to cellular regions located downstream from the pipette opening. Furthermore, pressure application of agonist-free solution did not induce Ca2+ release or Ca2+ entry (not shown).

RESULTS

Ca2+ release and CCE induced by whole-cell stimulation

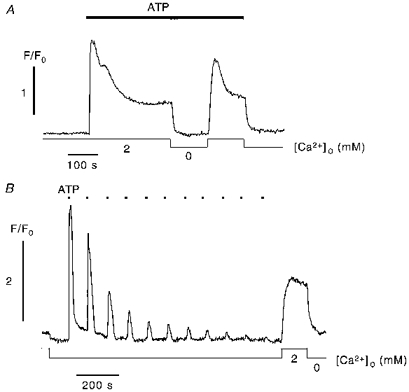

Figure 1 summarizes the characteristics of intracellular Ca2+ release and CCE upon stimulation of the whole cell with ATP. Prolonged stimulation of the cell with a high agonist concentration (Fig. 1A) resulted in a rapid rise of [Ca2+]i due to Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive stores (Schilling et al. 1992). [Ca2+]i subsequently declined to an elevated plateau level, which was determined by the rate of CCE and the counteracting cellular Ca2+ extrusion mechanisms (Schilling et al. 1992; Madge et al. 1997; Klishin et al. 1998). Consequently, removal of extracellular Ca2+ resulted in a decrease in [Ca2+]i to resting levels. Subsequent readdition of Ca2+ to the extracellular solution caused a CCE signal with a rapid rise and a marked overshoot followed by a decrease in [Ca2+]i to the previously described plateau level. Klishin and co-workers (Klishin et al. 1998) have attributed this overshoot of CCE to the delayed Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent activation of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump. The overshoot, however, was not seen in all recordings, most probably because CCE was not always maximally activated under our experimental conditions. Figure 1B shows a recording from a cell repetitively stimulated with short (10 s) pulses of ATP (1 μm) in Ca2+-free solution. Because of the net cellular Ca2+ loss associated with each stimulation, the amplitude of the resulting [Ca2+]i transients decreased progressively. Following store depletion by this protocol readdition of extracellular Ca2+ elicited a large CCE transient.

Figure 1. Ca2+ release and capacitative Ca2+ entry in response to global agonist stimulation.

A, superfusion with ATP (1 μm) of the whole cell in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ evoked a biphasic [Ca2+]i transient. The initial phase was caused by Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, while the maintained plateau phase was primarily carried by CCE. Consequently, removal of extracellular Ca2+ resulted in a decrease of [Ca2+]i to resting levels. Readdition of Ca2+ typically elicited a biphasic rise in [Ca2+]i carried exclusively by CCE. B, repetitive agonist stimulation (1 μm ATP, 10 s pulses) in Ca2+-free solution elicited [Ca2+]i transients with successively decreasing amplitudes caused by progressive store depletion. The marked rise in [Ca2+]i upon readdition of extracellular Ca2+ indicated the activation of CCE.

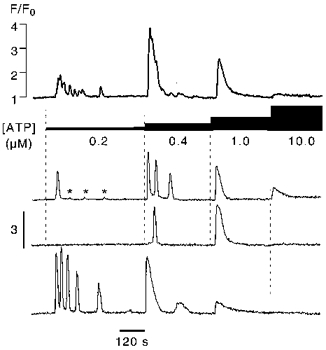

The biphasic time course of the [Ca2+]i transient evoked by 1 μm ATP with its pronounced plateau phase in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 1A) was the first indication that this agonist concentration maximally stimulated Ca2+ release. To further test the concentration dependence of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization by the purinergic agonist we superfused endothelial cells with increasing ATP concentrations in Ca2+-free solution. The result is shown in Fig. 2. The ensemble trace (Fig. 2, top trace) which represents the mean fluorescence changes of 20 cells subjected to the same experimental protocol revealed that submaximal ATP concentrations did not mobilize all the releasable Ca2+. This phenomenon which is commonly referred to as quantal Ca2+ release (Muallem et al. 1989) has been observed in many electrically non-excitable cells (for a review see Bootman et al. 1994; Parys et al. 1996). The concentration dependence for ATP was steep, with a threshold concentration for Ca2+ release of about 150 nM (not shown in this set of recordings). In most cells (90 %) superfusion with 1 μm ATP resulted in the complete discharging of the agonist-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ pool. Further increase of the agonist concentration was without any effect on [Ca2+]i.

Figure 2. Concentration dependence of ATP-induced Ca2+ release.

Endothelial cells were superfused with increasing concentrations of ATP in Ca2+-free solution. The top trace shows the mean fluorescence ([Ca2+]i) changes obtained from 20 cells subjected to the same experimental protocol. The 3 lower traces were derived from individual cells. Very low ATP concentrations caused single [Ca2+]i spikes or locally restricted release events (marked by asterisks). Submaximal ATP concentrations (0.2–0.4 μm) released only a fraction of the total intracellularly stored Ca2+. Typically, Ca2+ release evoked by intermediate agonist concentrations was oscillatory. A further step increase in [ATP] resulted in an additional [Ca2+]i transient or enhanced oscillations. Maximally stimulatory agonist concentrations (≥1μM) evoked only a single slowly declining [Ca2+]i transient.

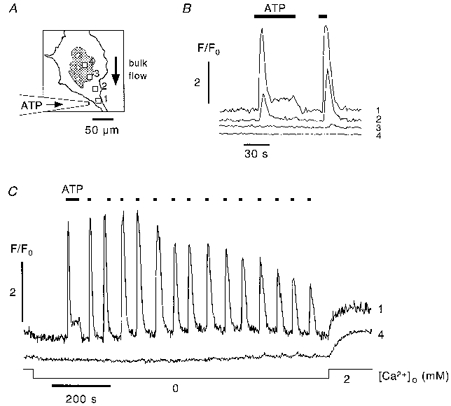

Focal agonist stimulation triggers subcellularly restricted Ca2+ release

In the experiment depicted in Fig. 3 agonist stimulation was confined to one end of a narrow cell process (Fig. 3A, position 1). We used 1 μm ATP for local stimulation rather than a supramaximal agonist concentration to ensure that Ca2+ release remained confined to the stimulated region. Furthermore, 1 μm ATP should mobilize most or all intracellular Ca2+ at the site of stimulation (see Fig. 2) resulting in a marked and rapid depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Purinergic stimulation rapidly initiated Ca2+ release at the site of stimulation (Fig. 3B, trace 1). Ca2+ release subsequently extended some 10 μm (Fig. 3B, trace 2) into non-stimulated regions but failed to propagate further than ∼60 μm (traces 3 and 4). It should be noted that the spatio-temporal pattern of Ca2+ release elicited by focal agonist stimulation critically depended on the geometry of the cell and the subcellular region subjected to stimulation. Spatially restricted Ca2+ release could be induced most reliably when stimulating at narrow cell processes. In most cells release failed to propagate beyond the point where the cell process fused into the larger cell body. In contrast to global agonist stimulation in Ca2+-free solution (Fig. 1B), repetitive Ca2+ release transients could be evoked by focal ATP stimulation without pronounced signs of store depletion. In the example shown in Fig. 3C (trace 1), the amplitude of the 15th ATP-induced [Ca2+]i transient was still about 50 % that of the 1st transient. Thus, a mechanism must exist which attenuates store depletion when Ca2+ release is confined to a small subcellular region. A probable mechanism accounting for the continuous replenishment of Ca2+ stores is the redistribution of intracellularly stored Ca2+ ions within the ER from non-excited regions to the site where Ca2+ release and Ca2+ extrusion across the plasma membrane had occurred. Because in these particular experiments the cellular volume affected by focal agonist-induced Ca2+ release was small compared with the total cell volume, repetitive Ca2+ release resulted only in moderate signs of local store depletion. Finally, readdition of extracellular Ca2+ following repetitive focal ATP stimulation (Fig. 3C) resulted in a clearly detectable CCE signal at the site of stimulation (trace 1) and at a distant site where no Ca2+ release was observed (trace 4). The differences in the rate of rise of the CCE signal were most probably due to differences in the regional surface-to-volume (s/v) ratio, i.e. the rate of rise of the Ca2+ entry signal is higher in regions with a larger s/v ratio (Hüser & Blatter, 1997; Holda et al. 1998). These differences were most pronounced when comparing Ca2+ entry signals from regions located in the cell periphery or a fine cell process with those recorded in the cell body or in the perinuclear space.

Figure 3. Focal agonist stimulation results in spatially restricted Ca2+ release.

A, contour image of the cell. The shaded area represents the nuclear and perinuclear space. Focal ATP stimulation was confined to the end of a narrow cell process (position 1). Positions 2–4 are successively greater distances from the focal stimulation point into the main body of the cell. B, focal stimulation triggered Ca2+ release starting at the site of stimulation (trace 1). The region of elevated [Ca2+]i subsequently expanded in a wave-like fashion towards more central regions of the cell (trace 2). No release of Ca2+ could be detected at distances ≥ 75 μm (traces 3 and 4) from the site of stimulation. C, series of [Ca2+]i transients evoked by repetitive focal stimulation in Ca2+-free solution (trace 1). Notably, locally restricted Ca2+ release was less affected by store depletion when compared with global agonist stimulation (Fig. 1B). Note no detectable Ca2+ release at position 4.

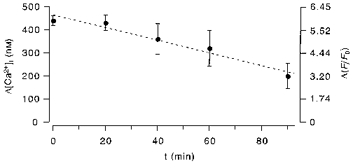

The data presented in Fig. 3 demonstrate that CCE can be activated in subcellular regions that do not show intracellular Ca2+ release. During the period of repetitive local agonist stimulation (17 min), however, the whole cell was superfused with Ca2+-free solution. It was likely that during this period stores in non-stimulated regions lost some Ca2+ due to agonist-independent leakage of Ca2+ from the intracellular store. To test whether such passive Ca2+ leakage from intracellular Ca2+ stores can account for the time-dependent activation of CCE at remote sites, we measured the amount of Ca2+ releasable by ATP (10 μm) as a function of time of preincubation in Ca2+-free solution (Fig. 4). The results revealed that in endothelial cells the passive discharge of the agonist-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ store was very slow. Furthermore, CCE was not detectable as a change of [Ca2+]i in cells incubated for less than 90 min in Ca2+-free solution (not shown here). It should be noted here that the sensitivity of [Ca2+]i measurements to CCE is limited. The rate of CCE has to be sufficiently high to overcome cellular Ca2+ buffering and ER reuptake to be detected by the fluorescence indicator. Therefore failure to record CCE signals at times ≤ 90 min does not necessarily indicate the absence of Ca2+ entry. The experiment demonstrates, however, that passive Ca2+ leakage from the ER alone was not sufficient to account for a significant activation of CCE in cells superfused with Ca2+-free solution for periods of less than 20 min.

Figure 4. Passive store depletion by Ca2+ leakage.

Endothelial cells were superfused with Ca2+-free solution and stimulated with 10 μm ATP to release Ca2+ from the entire agonist-sensitive Ca2+ pool. The plot of the mean amplitude (each point represents the mean ±s.d. of 4–8 cells) of the resulting [Ca2+]i transient vs. the time of preincubation in Ca2+-free solution revealed only a slow loss of releasable Ca2+ from intracellular Ca2+ stores in the absence of agonist. [Ca2+]i has been calculated according to the formula: [Ca2+]i=Kd (F/F0)/(Kd/[Ca2+]rest - (F/F0) + 1), where Kd= 1 μm and [Ca2+]rest= 50 nM.

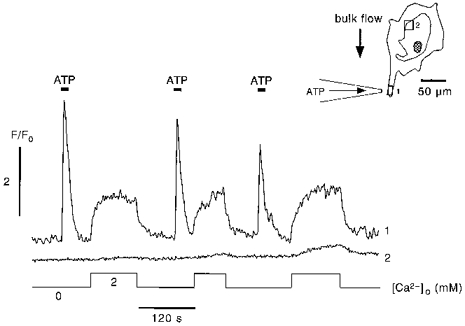

Colocalization of CCE with Ca2+ release

From the experiments presented it became clear that CCE could be activated in subcellular regions where no previous Ca2+ release had occurred. Moreover, the distance between sites of intracellular Ca2+ release (and concomitant Ca2+ loss in Ca2+-free solution) and sites of capacitative Ca2+ entry could be large suggesting that locally restricted Ca2+ depletion could lead to global activation of CCE across the entire plasma membrane. In the experiment shown in Fig. 5 conditions were chosen to further resolve the spatial and temporal dependence of CCE on agonist-induced intracellular Ca2+ release. As in previous experiments, focal ATP stimulation was restricted to a cell process (Fig. 5, inset, position 1). The resulting Ca2+ release propagated to the point where the cell process fused into the larger cell body. No Ca2+ release was observed at a site ∼100 μm away (position 2) from the region showing Ca2+ release. Readdition of extracellular Ca2+ following the first short ATP pulse revealed a clear CCE transient in the cell process (Fig. 5, trace 1). No appreciable CCE signal, however, could be recorded at the distant unstimulated site (Fig. 5, trace 2). Importantly, repeating this protocol caused CCE to become visible and progressively larger at the remote site where at no point in time had any Ca2+ release occurred. Thus, while CCE was initially colocalized with Ca2+ release in the cell process, repetitive local Ca2+ release caused activation of CCE at sites not participating in IP3-induced Ca2+ release. Initial colocalization of CCE with Ca2+ release was observed in all five cells subjected to comparable stimulation protocols. The lack of changes in [Ca2+]i at the remote site during agonist stimulation suggested that a possible mechanism for the slow spatial spread of CCE from the site of Ca2+ release/loss to non-excited regions might be provided by the redistribution of Ca2+ within the ER Ca2+ store.

Figure 5. Colocalization of CCE with Ca2+ release.

Comparison of the time course of [Ca2+]i at the cell process (inset, position 1) and a remote site (inset, position 2) not participating in intracellular Ca2+ release. Following the first ATP pulse (1 μm for 10 s) in Ca2+-free solution, readdition of extracellular Ca2+ revealed activation of CCE at the site of Ca2+ release (trace 1). At this time, no Ca2+ entry could be detected at the remote site. With repetitive focal stimulation of Ca2+ release, however, CCE became progressively visible at the distant non-stimulated site (trace 2).

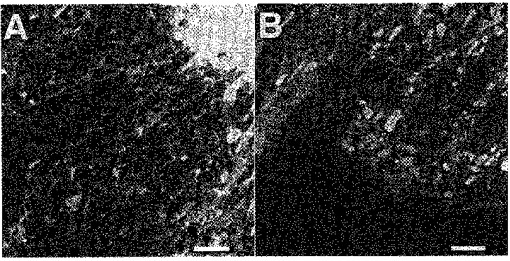

Staining of endothelial cells with the carbocyanine dye DiOC6, which has been used to stain intracellular endo- and sarcoplasmic Ca2+ stores in various cell types (e.g. Terasaki et al. 1985; Blatter, 1995; Golovina & Blaustein, 1997), revealed heteromorphic intracellular structures (Fig. 6). Image resolution was best in the cell periphery, where the cell thickness is likely to be less than one confocal section. Besides the round or ellipsoid structures (Fig. 6B), DiOC6 labelled a structure of narrow interconnected tubules. Because of their shape and higher fluorescence intensity the non-reticular structures were most probably mitochondria. The reticular structure closely resembled the ER morphology reported for example in kidney cells (Terasaki et al. 1985; Lee et al. 1989). The interconnection of the ER tubules supports the notion of a continuous intracellular Ca2+ storage organelle and provides the structural basis for a Ca2+ redistribution process within the ER lumen.

Figure 6. Visualization of the endoplasmic reticulum with DiOC6.

The carbocyanine dye DiOC6 stained heteromorphic structures in vascular endothelial cells. The images show detailed subcellular sections from the perinuclear region (left) and the cell periphery (right) at high electronic magnification (average of 8 consecutively recorded frames). The vesicular structures in the cell periphery most probably represent mitochondria, since their fluorescence intensity markedly exceeds the staining of the reticular structure. In addition, similar structures were labelled when tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE), which selectively stains mitochondria, was applied (not shown). The ER was visible as a network of narrow interconnected tubules. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

The experiments presented in this paper used spatially resolved confocal [Ca2+]i measurements together with focal agonist stimulation to study the subcellular regulation of intracellular Ca2+ release and capacitative Ca2+ entry in vascular endothelial cells. The main results of this study were threefold. First, focal agonist stimulation at a small cell process caused spatially restricted release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Release frequently propagated some tens of micrometres into non-stimulated regions. Second, Ca2+ store depletion by repetitive focal stimulation of a small subcellular region had a slower time course than store depletion caused by stimulation of the entire cell. Third, CCE was initially restricted to those subcellular regions where Ca2+ release had occurred previously. Following repetitive local release and concomitant Ca2+ extrusion at the site of release, however, capacitative Ca2+ entry became detectable at remote sites, which did not participate in Ca2+ release.

The purinergic agonist ATP binds to surface membrane receptors to stimulate the membrane bound intracellular formation of IP3 by phospholipase C (Madge et al. 1997). IP3 is a diffusible messenger that binds to the IP3 receptor in the ER membrane to initiate Ca2+ release into the cytosol (Berridge, 1997). Confining agonist stimulation to a small subcellular region by focal agonist application is expected to result in marked subcellular [IP3] gradients. IP3 diffusion away from its site of synthesis most probably accounted for the spread of Ca2+ release into regions excluded from extracellular stimulation in our experiments. The range of action of IP3, which is determined by its diffusion coefficient and its rate of degradation, has been estimated to be about 17 μm (Kasai & Petersen, 1994). This value, however, should vary significantly with cell geometry. In particular, when stimulating a narrow cell process with a high s/v ratio, the resulting rise in [IP3] will be faster and reach higher concentrations than in the cell body (compare Schaff et al. 1997). As a result the diffusional spread of IP3 is faster and is expected to extend over larger distances in the narrow processes than in the cell body. It is therefore conceivable that the diffusion of IP3 from its site of formation underlies the observed propagation of Ca2+ release of about 40–80 μm into non-stimulated regions. [Ca2+]i waves most frequently failed to propagate beyond the point where the cell process fused into the larger cell body. During whole-cell agonist stimulation [Ca2+]i waves also started in the cell processes before propagating towards the centre of the cell. Under these conditions, the wave propagation velocity abruptly slowed down at the points where the narrow process merged with the large volume cell body (Hüser & Blatter, 1997).

Agonist-induced Ca2+ release in Ca2+-free solution was associated with a pronounced depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. The degree of depletion depended on the agonist concentration. Submaximal concentrations released only a fraction of the intracellularly stored Ca2+. Thus agonist- induced Ca2+ release in vascular endothelial cells displayed quantal behaviour typical for many non-excitable cells (Parys et al. 1996). The ATP concentration used for local and global stimulation (1 μm) in our experiments was high enough to ensure local release of the major fraction of stored Ca2+ and subsequent Ca2+ extrusion. Depletion of the Ca2+ store, in turn, resulted in the activation of CCE (Fig. 1B; see also Schilling et al. 1992). The rate of Ca2+ loss from the ATP-sensitive intracellular store during superfusion with Ca2+-free solution in the absence of agonist stimulation was very slow (Fig. 4). In fact, after 90 min preincubation in Ca2+-free medium the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i transient was reduced by only 50 %. At this point Ca2+ entry was not detectable as a change of [Ca2+]i upon readdition of extracellular Ca2+. Ca2+ extrusion and the resulting store depletion were markedly facilitated during agonist stimulation. The rate of store depletion with repetitive agonist stimulation, however, was considerably less when stimulation was restricted to a small cell process. Therefore, a mechanism must exist which compensates for the local loss of stored Ca2+. An attractive candidate for such a mechanism is the intraluminal redistribution of stored Ca2+ within the ER. The visualization of the ER as narrow interconnected tubules (Fig. 6; compare Lee et al. 1989) supports the notion that the ER forms a continuous intracellular membrane network. Moreover, the ER continuity has been assessed functionally using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) in basophilic leukaemia cells expressing a luminal 60 kDa protein conjugated with the green fluorescent protein (Subramanian & Meyer, 1997). The FRAP experiments revealed a high mobility of the protein within the ER lumen with an apparent diffusion coefficient of ∼0.5 μm2 s−1. Thus local Ca2+ depletion can be effectively counteracted by redistribution of stored Ca2+ within the ER. Thus, locally restricted Ca2+ release and depletion would eventually result in global store depletion (Fig. 3). Again, the slow rate of passive store depletion ruled out the possibility that incubation of the cell in Ca2+-free solution alone accounts for the time-dependent activation of CCE at non-stimulated sites.

Mogami and co-workers (Mogami et al. 1997) have presented evidence that Ca2+ entry and reuptake into the Ca2+ store restricted to the basolateral membrane of pancreatic acinar cells resulted in refilling of Ca2+ stores at the apical pole of the cell. Because the refilling of apical stores was not accompanied by any detectable increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, these authors concluded that Ca2+ ions were transported from the site of uptake into basolateral stores via ‘tunnels’ to release sites at the opposite pole of the cell. Similarly, the redistribution of stored Ca2+ in our experiments was not accompanied by any detectable change in [Ca2+]i. Such a mechanism necessitates a continuous ER-Ca2+ store allowing effective intraluminal diffusion of Ca2+. Generally, the ER-Ca2+ store appears to be physically continuous. Intraluminal Ca2+ diffusion tends to equilibrate concentration gradients within the store. The rate of redistribution, however, is slow when compared with the rate of Ca2+ release and/or uptake. Therefore, segregation of release channel proteins (IP3 or ryanodine receptors) and Ca2+ pumps into discrete subcellular ER regions may account for the functional compartmentalization of cytosolic and intraluminal [Ca2+] directly visualized in imaging experiments (e.g. Button & Eidsath, 1996; Golovina & Blaustein, 1997; Berridge, 1997; Hüser & Blatter, 1997).

As pointed out above, the intraluminal redistribution of stored Ca2+ provides a means for the spatial spread of store depletion. This mechanism would account for the activation of CCE at a site where no Ca2+ release preceded Ca2+ entry (Figs 3 and 5). Following readdition of extracellular Ca2+ to probe for activation of CCE after a single focal agonist stimulation (Fig. 5) the CCE-mediated rise in [Ca2+]i strictly colocalized with the site of Ca2+ release. A similar colocalization of CCE with Ca2+ release has been reported for Xenopus laevis oocytes (Petersen & Berridge, 1996; Jaconi et al. 1997). Although these experiments do not exclude the participation of a diffusible intracellular messenger in the activation of CCE, they suggest that the effective range of such a factor does not exceed that of IP3. Both Ca2+ release induced by IP3 and activation of CCE are controlled locally at the subcellular level. In this model, local store depletion would lead to activation of CCE only in plasma membrane areas in the proximity of the store. Furthermore, disruption of the structural arrangement of the participating signalling components by degradation of cytoskeletal elements has been shown to selectively suppress CCE but not agonist-induced Ca2+ release (Holda & Blatter, 1997). Thus, the spatial range of the CCE-activating signal is clearly more restricted than the receptor-induced intracellular IP3 signal. In addition, a possible direct involvement of the cytoskeleton in the CCE signalling mechanism presents an attractive hypothesis which, however, needs further experimental support. It should be noted that the requirement of an intact cytoskeleton for CCE activation may be cell type-specific, since in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts disruption of actin microfilaments exerted opposite effects (Ribeiro et al. 1998). According to these authors, CCE in cytochalasin D-treated cells remained functional but IP3-dependent Ca2+ release was abolished.

In summary, subcellularly localized activation of the inositolphosphate metabolism by focal application of the purinergic receptor agonist ATP resulted in spatially restricted Ca2+ release in vascular endothelial cells. Due to the diffusional spread of IP3, Ca2+ release expanded some tens of micrometres into non-stimulated regions. Local store depletion caused activation of CCE that was initially restricted to the site of Ca2+ release. Furthermore, subsequent redistribution of stored Ca2+ within the ER-Ca2+ store from non-stimulated regions to sites of local depletion served to replenish the Ca2+ store in the stimulated region and to spread the signal for CCE activation throughout the cell.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr S. L. Lipsius and K. Sheehan for critically reading the manuscript and R. Gulling for expert technical help. This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-51941 and by grants from the American Heart Association National Center, the Arthur J. Schmitt Foundation, and the Schweppe Foundation Chicago. L. A. B. is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association. J. H. is a postdoctoral fellow of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

References

- Berridge MJ. Capacitative calcium entry. Biochemical Journal. 1995;312:1–11. doi: 10.1042/bj3120001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Elementary and global aspects of calcium signalling. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;499:291–306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatter LA. Depletion and filling of intracellular calcium stores in vascular smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:C503–512. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.2.C503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootman MD, Cheek TR, Moreton RB, Bennett DL, Berridge MJ. Smoothly graded Ca2+ release from inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive Ca2+ stores. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:24783–24791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button D, Eidsath A. Aequorin targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum reveals heterogeneity in luminal Ca2+ concentration and reports agonist- or IP3-induced release of Ca2+ Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1996;7:419–434. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.3.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BC, Lee C-M, Lee YT, Lin W-W. Characterization of signaling pathways of P2Y and P2U purinoceptors in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1996;28:192–199. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovina VA, Blaustein MP. Spatially and functionally distinct Ca2+ stores in sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 1997;275:1643–1648. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1643. 10.1126/science.275.5306.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holda JR, Blatter LA. Capacitative calcium entry is inhibited in vascular endothelial cells by disruption of cytoskeletal microfilaments. FEBS Letters. 1997;403:191–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00051-3. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holda JR, Klishin A, Sedova M, Hüser J, Blatter LA. Capacitative calcium entry. News in Physiological Sciences. 1998;13:157–163. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1998.13.4.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hüser J, Blatter LA. Elementary events of agonist-induced Ca2+ release in vascular endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:C1775–1782. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaconi M, Pyle J, Bortolon R, Ou J, Clapham DE. Calcium release and influx colocalize to the endoplasmic reticulum. Current Biology. 1997;7:599–602. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00259-4. 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai H, Petersen OH. Spatial dynamics of second messengers: IP3 and cAMP as long-range and associative messengers. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90112-0. 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klishin A, Sedova M, Blatter LA. Time-dependent modulation of capacitative Ca2+ entry signals by plasma membrane Ca2+ pump in endothelium. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C1117–1128. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.4.C1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Ferguson M, Chen LB. Construction of the endoplasmic reticulum. Journal of Cell Biology. 1989;109:2045–2055. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2045. 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madge L, Marshall ICB, Taylor CW. Delayed autoregulation of the Ca2+ signals resulting from capacitative Ca2+ entry in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;498:351–369. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogami H, Nakano K, Tepekin AV, Petersen OH. Ca2+ flow via tunnels in polarized cells: recharging of apical Ca2+ stores by focal Ca2+ entry through basal membrane patch. Cell. 1997;88:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81857-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muallem S, Pandol SJ, Beeker TG. Hormone-evoked calcium release from intracellular stores is a quantal process. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:205–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso AM, Mason SJ, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. Membrane-restricted regulation of Ca2+ release and influx in polarized epithelia. Nature. 1995;377:643–646. doi: 10.1038/377643a0. 10.1038/377643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB, Penner R. Store depletion and calcium influx. Physiological Reviews. 1997;77:901–930. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parys JB, Missiaen L, De Smedt H, Sienaert I, Casteels R. Mechanisms responsible for quantal Ca2+ release from inositol trisphophate-sensitive calcium stores. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;432:359–367. doi: 10.1007/s004240050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen CCH, Berridge MJ. Capacitative calcium entry is colocalised with calcium release in Xenopus oocytes: evidence against a highly diffusible calcium influx factor. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;432:286–292. doi: 10.1007/s004240050135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JW., Jr . Capacitative Calcium Entry. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro CMP, Reece J, Putney JW., Jr Role of the cytoskeleton in calcium signalling in NIH 3T3 cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;272:26555–26561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaff J, Fink CC, Slepchenko B, Carson JH, Loew LM. A general computational framework for modeling cellular structure and function. Biophysical Journal. 1997;73:1135–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling WP, Cabello OA, Rajan L. Depletion of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate sensitive intracellular Ca2+ store in vascular endothelial cells activates the agonist-sensitive Ca2+-influx pathway. Biochemical Journal. 1992;284:521–530. doi: 10.1042/bj2840521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian K, Meyer T. Calcium-induced restructuring of nuclear envelope and endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores. Cell. 1997;89:963–971. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki M, Song J, Wong JR, Weiss MJ, Chen LB. Localization of endoplasmic reticulum in living and glutaraldehyde-fixed cells with fluorescent dyes. Cell. 1985;38:101–108. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]