Abstract

The distribution of ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP channels) was investigated in four cell types in hippocampal slices prepared from 10- to 13-day-old rats: CA1 pyramidal cells, interneurones of stratum radiatum in CA1, complex glial cells of the same area and granule cells of the dentate gyrus. The neuronal cell types were identified visually and characterized by the shapes and patterns of their action potentials and by neurobiotin labelling.

The patch-clamp technique was used to study the sensitivity of whole-cell currents to diazoxide (0·3 mm), a KATP channel opener, and to tolbutamide (0·5 mm) or glibenclamide (20 μm), two KATP channel inhibitors. The fraction of cells in which whole-cell currents were activated by diazoxide and inhibited by tolbutamide was 26% of pyramidal cells, 89% of interneurones, 100% of glial cells and 89% of granule cells. The reversal potential of the diazoxide-induced current was at the K+ equilibrium potential and a similar current activated spontaneously when cells were dialysed with an ATP-free pipette solution.

Using the single-cell RT-PCR method, the presence of mRNA encoding KATP channel subunits (Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1 and SUR2) was examined in CA1 pyramidal cells and interneurones. Subunit mRNA combinations that can result in functional KATP channels (Kir6.1 together with SUR1, Kir6.2 together with SUR1 or SUR2) were detected in only 17% of the pyramidal cells. On the other hand, KATP channelsmay be formed in 75%of the interneurones, mainly by the combination of Kir6.2 with SUR1 (58% of all interneurones).

The results of these combined analyses indicate that functional KATP channels are present in principal neurones, interneurones and glial cells of the rat hippocampus, but at highly different densities in the four cell types studied.

Compared with other areas of the brain, the hippocampus is extremely sensitive to hypoxia (Smith et al. 1984) and has a very low threshold for the initiation of epileptiform activity (Dichter & Ayala, 1987). It has frequently been suggested (see e.g. Alzheimer & ten Bruggencate, 1988; Mourre et al. 1989) that ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels) may play a decisive role in these processes, because these channels couple cell metabolism to excitability (for a review on KATP channels see Ashcroft & Ashcroft, 1990).

Evidence for the existence of KATP channels in the brain came initially from the presence of binding sites for the sulphonylurea glibenclamide, a fairly specific inhibitor of KATP channels (Mourre et al. 1989). In the hippocampus of the adult rat, the highest densities of glibenclamide binding sites were found in the granular layer of the dentate gyrus and in the stratum lucidum of the CA3 field, whereas in other hippocampal areas the densities of the sites were intermediate to low (Mourre et al. 1991).

Subsequent searches for KATP channels in brain slices with electrophysiological techniques have demonstrated the existence of KATP channels in neurones of the substantia nigra (Schwanstecher & Panten, 1993), the striatum (Schwanstecher & Panten, 1994; Lee et al. 1998), the hypothalamus (Ashford et al. 1990) and the midbrain (Guatteo et al. 1998). However, electrophysiological studies on hippocampal slices have not yet provided a definite answer. Most of these studies were performed on CA1 pyramidal neurones of rat hippocampus and even for this single cell type the results were controversial. Extreme views were presented by Erdemli & Krnjevi´c (1996) and Hyllienmark & Brismar (1996) who questioned the existence of KATP channels in these cells, and by Fujimura et al. (1997) who ascribed a decisive role to KATP channels in the hypoxic hyperpolarization of CA1 pyramidal cells.

The recent molecular characterization of KATP channels has offered additional ways to localize the subunits of these channels in various tissues. As first shown for the KATP channel of pancreatic β cells (Inagaki et al. 1995a), this channel is composed of the inward rectifier K+ channel Kir6.2 and a sulphonylurea receptor SUR (now named SUR1, see Inagaki et al. 1996). The overlap in the distribution of the two subunits found in brains of adult rat and mouse by in situ hybridization analysis suggests the presence of KATP channels in the respective regions. Interestingly, the expression of Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunit mRNA in the hippocampus was strongest in dentate gyrus granule cells but only moderate in CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cells (Karschin et al. 1997).

The aim of the present study was to look for the presence and subunit composition of KATP channels in individual, identified hippocampal cells of rat brain slices by performing whole-cell current measurements and by using the single-cell reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) method.

Some of the results have been published in abstract form (Zawar et al. 1997, 1998).

METHODS

Preparation of hippocampal slices

Hippocampal slices were prepared from brains of young (10- to 13-day-old) Wistar rats as described previously (Edwards et al. 1989). In short, rats were decapitated and brain hemispheres rapidly isolated and transferred into ice-cold bicarbonate-buffered standard saline (for composition see below). Hippocampal slices of 200-300 μm thickness were cut with a vibratome, then kept for 1 h at 34°C, and thereafter at 25°C in a chamber containing standard saline bubbled with a mixture of 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2 before electrophysiological recordings were performed.

Solutions and drugs

The composition of the standard saline (bath solution) was (mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3 and 20 glucose (pH 7.4 when gassed with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2). To block voltage-gated Na+ channels and GABA-mediated postsynaptic currents, 0.5 μm tetrodotoxin (TTX) and 10 μm bicuculline methiodide, respectively, were added to the standard saline. TTX was not used during recordings of action potentials. The pipette solution (internal solution) contained (mM): 140 KCl, 11 EGTA, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes and, unless otherwise noted, 0.5 ATP (pH 7.2 with KOH). The calculated K+ equilibrium potential is -102 mV at 22°C. To label the cells for morphological studies, 1 % neurobiotin tracer (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) was added to the internal solution. Tolbutamide (Sigma) and diazoxide (Schering, Berlin, Germany) were added to the standard saline as 20 mM stock solutions dissolved in 0.15 M NaOH and the pH adjusted to 7.4 with HCl. Glibenclamide (Sigma) was dissolved as a 20 mM stock solution in DMSO and diluted in the standard saline. In single-cell RT-PCR experiments, the pipette solution contained (mM): 140 KCl, 5 EGTA, 3 MgCl2, 10 Hepes and 5 ATP (pH 7.2). In this case, all chemicals were RNase free and the solution was sterilized by filtering before use.

Electrophysiological recordings

For electrophysiological measurements, slices were transferred to the recording chamber where they were continuously perfused with oxygenated standard saline at room temperature (19-23°C) or with this saline containing diazoxide and/or tolbutamide or glibenclamide (see below). The four cell types studied (pyramidal cells of CA1, interneurones from the stratum radiatum of CA1, complex glial cells from the same layer and granule cells from the dentate gyrus) were identified visually using a × 40 water immersion objective on an upright microscope (Axioscope FS, Zeiss) with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics.

Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany), coated with silicone resin (General Electrics, Rüsselsheim, Germany), and had resistances of 2-3 MΩ when filled with the internal solution. All experiments were performed using the tight-seal whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique with an EPC-9 amplifier and Pulse software (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). Slow capacity current transients were compensated and the cell capacitance (C) estimated from this compensation. The series resistances in all experiments were within the range between 4.0 and 22.1 MΩ with a mean (±s.e.m.) of 11.4 ± 0.5 MΩ (n= 74). In the current-clamp mode, the resting membrane potential was determined and cells were tested for their ability to generate action potentials spontaneously and in response to depolarizing current pulses. In the voltage-clamp mode, the holding potential was set to -70 mV and membrane currents were recorded using two voltage pulse protocols: (i) 100 ms voltage steps to -80 and -60 mV separated by a gap of 100 ms and 15 s intervals between subsequent -80 mV steps, (ii) voltage ramps of 2 s duration from +40 to -120 mV and a pause of 10 s between subsequent ramps. Data were sampled at 100 μs intervals (2 ms intervals in the ramp experiments) and filtered by a four-pole Bessel filter at 3.3 kHz (167 Hz in the ramp experiments).

Single-cell RT-PCR

All cells examined by the single-cell RT-PCR were identified visually and monitored during the harvesting of the cell content by infrared-differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) microscopy (Dodt & Ziegelgänsberger, 1990). To harvest the cytoplasm, steady negative pressure was applied to the pipette in the whole-cell recording mode and the flow of cytoplasm from the cell to the pipette followed on a video monitor (Plant et al. 1997). As much of the cell content as possible, but without the nucleus, was harvested without loss of the seal. The nucleus was not aspirated to avoid possible amplification of genomic DNA from the intronless Kir6.2 in the PCR. Under a dissecting microscope, the pipette tip was broken and the contents of the pipette expelled into a PCR tube by application of positive pressure (N2, 200-400 kPa). The tube contained 2.5 μl of a solution of hexamer random primers (final concentration, 5 μm), the four deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (final concentration, 0.5 mM) and dithiothreitol (final concentration, 10 mM), to which 20 U ribonuclease inhibitor and 100 U Moloney murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL) were added (for details see Lambolez et al. 1992; Audinat et al. 1994). The ∼10 μl of reaction mix was incubated at 37°C for 1 h to synthesize single-stranded complementary DNA (cDNA), then stored at -80°C up to 5 days until used for PCR amplification. Controls with water and with total RNA from adult rat brain, prepared using a guanidinium thiocyanate single-step method (Chomczynski & Sacchi, 1987), were performed in parallel.

A multiplex PCR (mPCR; see e.g. Ruano et al. 1997) protocol was used to amplify simultaneously the mRNA transcipts of the KATP channel subunits Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1 and SUR2 using the following subunit-specific pairs of primers. Kir6.1: up 5′: TTGGGT TTGGAGGGAGAATG, starting point (SP) 421; low: ACAGGG GGCTACGCTTATCA, SP 832; fragment size, 411 bp. Kir6.2: up 5′: CTGCCTTCCTTTTCTCCATC, SP 355; low: TTACCACCCACA CCGTTCTC, SP 740; fragment size, 385 bp. SUR1: up 5′: TGG GGAACGGGGCATCAACT, SP 2465; low: TGGCTCTGGGGC TTTTCTC, SP 2853; fragment size, 388 bp. SUR2: up 5′: GCAAGAGCGTGGAAGAGAC, SP 1534; low: TGCCCCATGAGA AGTATCC, SP 2035; fragment size, 501 bp.

All of these primers were designed according to the nucleotide sequences deposited in GenBank (accession numbers: Kir6.1: D42145; Kir6.2: D86039, X97041, U44897; SUR1: L40624, X97279; SUR2: D83598) using the oligo program (Rychlik & Rhoads, 1989) version 4.0. Furthermore, mRNA transcripts encoding the NMDA glutamate receptor subunits NR2A-C were amplified in all CA1 pyramidal cells with primers according to Audinat et al. (1994). Taq polymerase (2.5 U; Taq 2000, Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany) in a buffer containing 1 mM Mg2+ was added to the 10 μl of RT product giving a final volume of 70 μl. Two drops of mineral oil (Sigma) were added and after 1 min at 94°C, the primer pairs (4 in interneurones for amplification of Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1 and SUR2, 5 in pyramidal cells for amplification of Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1, SUR2 and NR2A-C; 10 pmol each) in a volume of 30 μl were added. After 3 min at 94°C, 35 cycles (94°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; 72°C, 40 s) of PCR were performed, followed by an elongation period of 10 min at 72°C. The product of this amplification was purified using MicroSpin columns (Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). The purified product (3 μl) was used as a template in the second round of PCR amplification, where each of the four (or five) transcripts was individually amplified using its specific primer pair in 40 cycles of PCR (94°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s (59°C, 30 s for SUR1; 52°C, 36 s for NR2A-C); 72°C, 40 s; 10 min final elongation). The Mg2+ concentration of the PCR buffer was increased to 1.5 mM for the amplification of Kir6.1. To test for the specificity of the amplification products, the following restriction enzymes were used: Kir6.1, AvaII; Kir6.2, NdeI; SUR1, XhoI (all from Stratagene); SUR2, MspI (Pharmacia Biotech). Each amplification reaction or restriction digestion product (10 μl) was run on a 2 % agarose gel in parallel with pGEM (Promega Corp., Mannheim, Germany) as a molecular weight marker, and stained with ethidium bromide.

In our experiments the cell content was aspirated without the nucleus to avoid a possible amplification of genomic DNA in the PCR. As an additional control, single cells were treated in the same way as described above, but without adding reverse transcriptase to the RT reaction. Under these conditions, no amplification products were observed, showing that genomic DNA was indeed not amplified (n= 3).

Neurobiotin labelling and tissue staining

After establishing the whole-cell mode, cells were dialysed for at least 13 min with the standard pipette solution containing 1 % neurobiotin. During this time, the cell type was characterized electrophysiologically by the characteristic shapes and patterns of their action potentials (Fig. 1, bottom). At the end of the recordings, the slice was fixed for 30 min at room temperature in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Gibco-BRL) containing 4 % paraformaldehyde and 0.1 % glutaraldehyde. Then, slices were transferred to PBS with 4 % paraformaldehyde and further fixed overnight at 4°C. After rinsing 3 times for 10 min in PBS, the slices were incubated in PBS containing 0.1 % Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 1 h to permeabilize the cells, then rinsed again and afterwards transferred to PBS with 50 μg ml−1 fluorescein- avidin D (Vector Labs). After 2 h, the slices were rinsed and then mounted without dehydration in Vectorshield (Vector Labs).

Figure 1. Morphological and electrophysiological characterization of CA1 pyramidal cells, interneurones and dentate granule cells.

Top row, hippocampal slice stained with DAPI. The white frames enclose the regions in which the somata of CA1 pyramidal cells (A), interneurones from stratum radiatum CA1 (B) and dentate granule cells (C) were located. Second row, morphology of a pyramidal cell (A), an interneurone (B) and a granule cell (C). The cells were filled with neurobiotin, coupled to avidin-fluorescein, and imaged using a two-photon microscope. Axons are marked by white arrows. Note that the interneurone (B) is shown at a higher magnification and that the distal dendrites of this cell were cut during slicing. Third row, spontaneous action potentials recorded in the three cell types. Fourth row, trains of action potentials evoked by 400 ms current pulses of 50 pA, as indicated by the bars.

Labelled neurones were imaged with a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 (Munich, Germany) two-photon system (custom modified), equipped with a Tsunami titan/saphir laser (785 nm, pulsed with 80 MHz and pumped by a Millenia laser; both from Spectra-Physics, Darmstadt, Germany). The tissue was imaged with a × 20 (NA, 0.5) or a × 40 (NA, 0.8) Olympus water immersion objective in an Olympus microscope (BX50WI, Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) and the fluorescence detected at 510-570 nm. Optical sections at consecutive intervals of 1-2 μm were imaged through the depth of the labelled neurones and saved as image stacks. Summing up this stack using the summation option of the two-photon software onto a single plane generated a two-dimensional reconstruction of the labelled neurone (Fig. 1, second row).

To visualize the structure of the hippocampus, a separate set of slices was incubated in 2.5 μg ml−1 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride hydrate (DAPI, Sigma) for 2 min and the fluorescence detected at 620 nm (Fig. 1, top row).

Statistics

Cumulative results from n cells are given as means ±s.e.m. Significant differences between data from various hippocampal cell types were determined using Student's unpaired t test at the 1 or 0.1 % significance levels.

RESULTS

Morphological and electrophysiological characterization of hippocampal cells

In this study, neurones and glial cells from the hippocampus of 10- to 13-day-old rats were investigated. Glial cells from the stratum radiatum of the CA1 area could be distinguished from neurones by their inability to generate action potentials and by a more negative resting potential of -75.4 ± 3.8 mV (n= 15) when compared with CA1 pyramidal cells (-55.4 ± 1.8 mV; n= 17), CA1 interneurones from the stratum radiatum (-52.5 ± 1.2 mV; n= 22) and dentate granule cells (-57.1 ± 1.9 mV; n= 22). Glial cells were further subdivided into complex glial cells, which were identified by non-linear, time-dependent currents evoked by depolarizing and hyperpolarizing voltage steps, and passive glial cells that are characterized by time-independent currents (Steinhäuser et al. 1994).

The neurones investigated in this study were identified visually on the basis of their location in specific layers of the hippocampal slice and the morphology of their soma and primary dendrites. To verify this identification made using DIC optics, some neurones were characterized in more detail by the shapes and patterns of their action potentials and by neurobiotin labelling. These included five CA1 pyramidal cells, seven CA1 interneurones from the stratum radiatum and eight granule cells located in the dentate gyrus.

The top row of Fig. 1A-C shows a hippocampal slice from a 13-day-old rat. To localize the cell somata in the slice, the nuclei were stained with DAPI and the white frames enclose the areas in which the cell types examined were located. Fig. 1A illustrates a CA1 pyramidal cell with a typical pyramidal-shaped soma and the primary dendrite branching into the stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare. Spontaneous action potentials of this cell type were broader than those of interneurones and granule cells and showed a small, but long-lasting after-hyperpolarization (AHP). Current injection induced a train of action potentials in pyramidal cells with decreasing amplitude and increasing spike broadness (last 2 rows of Fig. 1A).

In contrast to pyramidal cells, the somata of CA1 interneurones from the stratum radiatum were multipolar. The axon of the interneurone shown in the second row of Fig. 1B was branched with several fine arborizations. Although the morphology of the interneurones examined was quite heterogeneous, the electrophysiological properties were similar. Spontaneous action potentials had a larger amplitude and shorter duration than those of pyramidal cells and the AHP was more pronounced (third row of Fig. 1B). The same current injection protocol as in Fig. 1A induced a train of action potentials of similar shapes with constant intervals between two spikes (fourth row of Fig. 1B). This interspike interval became shorter with current injections of increasing intensity (not shown). Therefore, the interneurones examined could be classified as ‘fast spiking cells’ in contrast to ‘non-fast spiking cells’ (Kawaguchi & Hama, 1987). The shapes and patterns of the action potentials in CA1 pyramidal cells and CA1 interneurones found in this study are characteristic for both cell types (Lacaille & Schwartzkroin, 1988; Morin et al. 1996). However, the amplitudes of action potentials in pyramidal cells were smaller than in interneurones in all of our experiments, but larger in the report of Morin et al. (1996). It is possible that the neurobiotin added to the pipette solution influenced the shape of the pyramidal cell action potentials, as recently shown for rat neostriatal neurones (Schlösser et al. 1998).

The second row of Fig. 1C illustrates the morphology of a granule cell in the dentate gyrus. In this cell, the axon originated from a primary dendrite, an anomaly described before (see Fig. 7 in Seress & Pokorny, 1981). Like CA1 interneurones, granule cells also showed a large and short action potential but with a different AHP shape. Current injection of 50 pA resulted either in short trains of action potentials at the beginning of the current pulse or in bursts of one to five action potentials separated by silent periods (fourth row of Fig. 1C). The most striking difference in the pattern of action potentials is the decrease in the amplitude of the potentials during the first few spikes in granule cells, whereas in the interneurones of this area, the amplitudes increase (Mott et al. 1997).

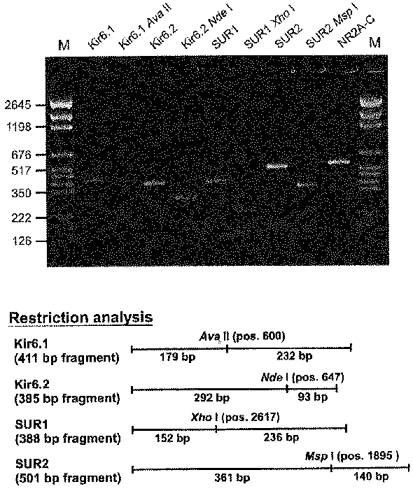

Figure 7. Presence of KATP channel subunit mRNA in adult rat brain.

Upper panel, agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR products from total RNA of adult rat brain stained with ethidium bromide. The amplification products of the KATP channel subunits Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1 and SUR2 as well as their restriction analysis are indicated for the different lanes. The restriction fragments are visible as faint bands except the smaller restriction fragment of the Kir6.2 amplification product, which was too small to be detected in the gel. The penultimate lane shows a 547 bp amplification product of the NMDA receptor subunits NR2A-C. M, molecular weight marker pGEM (fragment size in bp). Lower panel, restriction analysis with fragment sizes of the multiplex PCR products encoding KATP channel subunits, the restriction enzymes used and their corresponding restriction fragments. Furthermore, the position of digestion relative to the translation start site of the coding sequence for each KATP channel subunit is given.

Electrophysiological identification of KATP channels in hippocampal cells

Figure 2A shows whole-cell currents in a granule cell of the dentate gyrus recorded at the holding potential of -70 mV, during 100 ms pulses to -60 mV and after return to the holding potential. Corresponding current responses were elicited by potential steps to -80 mV. The stationary currents at the end of the -60 and -80 mV test pulses are plotted in Fig. 2B at various times after establishing the whole-cell mode. Initially, the currents at -60 and -80 mV changed spontaneously by a process that is probably related to the slow equilibration of the cell interior with the pipette solution. Bath application of diazoxide (0.3 mM) induced outward currents which were roughly twice as large at -60 than at -80 mV. The induced currents persisted for several minutes after wash-out of diazoxide but disappeared rapidly after application of tolbutamide (0.5 mM). A second treatment with diazoxide evoked smaller outward currents which, again, were sensitive to tolbutamide.

Figure 2. Response of a dentate granule cell to application of diazoxide and tolbutamide.

Responses of whole-cell currents in a granule cell of the dentate gyrus to diazoxide (Diaz) and tolbutamide (Tol). A, currents recorded before, during and after 100 ms pulses from -70 to -60 mV at the times indicated by a-c in the experiment illustrated in B. Inset, protocol of voltage pulses to -80 and -60 mV. B, stationary currents at -80 and -60 mV recorded at 15 s intervals at various times after forming the whole-cell mode. Diazoxide (0.3 mM) and tolbutamide (0.5 mM) were applied twice each as indicated by the bars. The bars show the time during which the drugs were present in the bath.

The effects of diazoxide and tolbutamide on whole-cell currents in various hippocampal cell types were studied using identical or similar protocols to that in Fig. 2. Thus, in the experiment of Fig. 3, performed on an interneurone in the stratum radiatum of CA1, the pipette solution contained no ATP (in all other experiments illustrated 0.5 mM ATP was added to the internal solution). With this ATP-free solution, an outward current developed with time upon wash-out of ATP from the cell. Similar currents that activated during dialysis with an ATP-free pipette solution were observed in four of six interneurones and in three of four granule cells, but in none of seven pyramidal cells. Figure 3 illustrates that, in addition to the current induced by wash-out of ATP, a second outward current component was evoked by diazoxide and that both current components were completely blocked by tolbutamide. The inhibitory effects of tolbutamide were observed even in the presence of diazoxide, which shows that wash-out of diazoxide was not a prerequisite for a subsequent current block by tolbutamide.

Figure 3. Response of a CA1 interneurone to application of diazoxide and tolbutamide.

Responses of whole-cell currents in an interneurone of the stratum radiatum of CA1 to diazoxide (0.3 mM) and tolbutamide (0.5 mM). A, currents recorded before, during and after 100 ms pulses from -70 to -60 mV at the times indicated by a-d in the experiment illustrated in B. B, stationary currents at -60 and -80 mV at various times after forming the whole-cell mode. The pipette solution contained no ATP in this experiment.

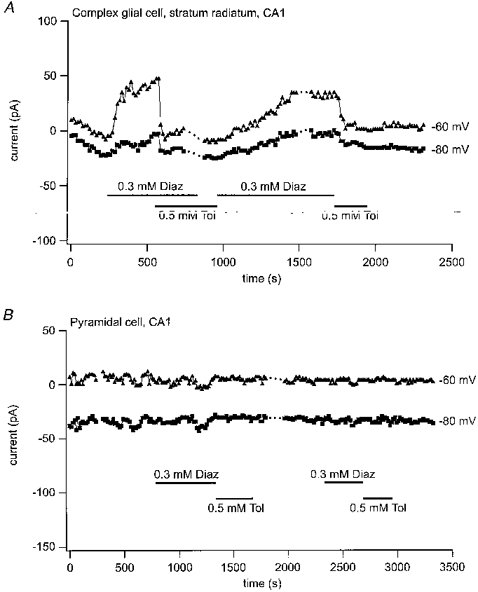

Diazoxide- and tolbutamide-sensitive currents were not only found in hippocampal neurones but also in glial cells. This is illustrated in Fig. 4A with whole-cell currents recorded in a complex glial cell in the stratum radiatum of CA1. In contrast, in passive glial cells, the currents measured in five experiments were completely insensitive to diazoxide and tolbutamide (not shown).

Figure 4. Response of a complex glial cell and a pyramidal cell to application of diazoxide and tolbutamide.

Responses of stationary whole-cell currents at -60 and -80 mV to diazoxide (0.3 mM) and tolbutamide (0.5 mM) in a complex glial cell from stratum radiatum CA1 (A) and in a CA1 pyramidal cell (B) at various times after forming the whole-cell mode.

Most of the CA1 pyramidal cells tested were also diazoxide and tolbutamide insensitive and only a small fraction of the cells exhibited weak responses after application of the drugs. An example of a cell which did not respond is shown in Fig. 4B. Neither application of diazoxide nor tolbutamide induced any current change at -60 or -80 mV.

In all neuronal and glial cells that responded to diazoxide and tolbutamide, the currents activated by diazoxide at -60 mV were larger than those at -80 mV. The reversal potentials of the activated currents, as obtained by linear interpolation between the current values at -60 and -80 mV, were -104.7 ± 1.9 mV for pyramidal cells (n= 7), -96.8 ± 1.5 mV for interneurones (n= 16), -96.1 ± 1.5 mV for glial cells (n= 10) and -99.8 ± 1.2 mV for granule cells (n= 17). To determine the reversal potential of the diazoxide-induced currents more accurately, whole-cell currents were recorded in response to voltage ramps in the absence and presence of diazoxide. In the experiment shown in Fig. 5, the diazoxide-induced currents reversed direction at -95 mV. The mean reversal potential of the diazoxide-induced currents in four interneurones was -102.8 ± 4.5 mV, close to the calculated K+ equilibrium potential of -102 mV. The outward rectification of the diazoxide-induced currents, seen in Fig. 5 and in all other experiments on interneurones, could be due to actions of diazoxide on voltage-dependent currents (Erdemli & Krnjevi´c, 1995). An outward rectification is also predicted by the different K+ concentrations in the external and internal solutions (2.5 and 140 mM, respectively).

Figure 5. Reversal potential of the diazoxide-induced whole-cell current.

Current-voltage relationships for an interneurone from the stratum radiatum of CA1 measured using voltage ramps of 2 s duration from +40 to -120 mV (voltage protocol in the upper inset). Each trace is the average of three ramps: a, control, before the application of diazoxide; b, diazoxide, in the presence of 0.3 mM diazoxide. b - a is the current induced by diazoxide. The lower inset shows the reversal potentials of the three traces at a higher resolution.

To summarize the effects of diazoxide (0.3 mM) and tolbutamide (0.5 mM) on the four hippocampal cell types investigated, cells of each type responding to both drugs by current changes larger than 5 pA at -60 mV were distinguished from cells that did not respond. The lower panel of Fig. 6 gives the proportions of the two classes. The extremes are complex glial cells from the stratum radiatum of CA1 which all responded and CA1 pyramidal cells of which more than 70 % did not react. As a quantitative measure of the activating effects of diazoxide in responding cells, we determined the currents induced by diazoxide at a potential of -60 mV (maximum current in the presence of 0.3 mM diazoxide minus stationary current after a subsequent application of 0.5 mM tolbutamide). The results are: 115 ± 11 pA for interneurones of stratum radiatum, CA1 (n= 16); 82 ± 16 pA for complex glial cells of stratum radiatum, CA1 (n= 10); 61.5 ± 8 pA for granule cells, dentate gyrus (n= 17); and 46 ± 6 pA for pyramidal cells, CA1 (n= 7). The differences in the mean currents of the various cell types could reflect different sizes of the neurones and glial cells of each group, and the large standard errors could be due to variable cell sizes within each group. To account for these possible differences and variabilities, the diazoxide-induced currents were normalized to the cell capacitance of each cell. The results are plotted in the upper part of Fig. 6 and reveal characteristic differences between the current/capacitance (I/C) values from the four hippocampal cell types studied. Specifically, the normalized responses in interneurones from the stratum radiatum of CA1 were significantly larger than those in granule cells of the dentate gyrus (P < 0.01) or in CA1 pyramidal cells (P < 0.001). The responses of granule cells from dentate gyrus (P < 0.001), as well as of complex glial cells from stratum radiatum of CA1 (P < 0.01), were also significantly larger than those of the CA1 pyramidal cells, which showed the weakest responses.

Figure 6. Amplitude of diazoxide-induced currents in different hippocampal cell types.

Maximum currents induced by 0.3 mM diazoxide at a potential of -60 mV in four hippocampal cell types as indicated. The figure summarizes experiments performed with pipette solutions without (n= 17) or with 0.5 mM ATP (n= 57). The lower panel shows the proportion of cells that responded to diazoxide and to tolbutamide. The maximum currents of the responding cells were normalized to the cell capacitance and plotted in the upper panel. The columns and bars denote the means ±s.e.m.

Additional experiments were performed to verify that diazoxide-induced currents in hippocampal cells were not only blocked by tolbutamide (0.5 mM), but also by glibenclamide (20 μm). The experiments were conducted using the same protocol as that in Fig. 2 and revealed a fast and complete block of diazoxide-induced currents in interneurones, complex glial cells and granule cells (n= 4 for each cell type, data not shown).

KATP channel subunit mRNA in adult rat brain

Before investigating the expression pattern of mRNA for KATP channel subunits in individual cells, we tested the sensitivity and selectivity of the primers designed to amplify KATP channel subunit cDNA (see Methods) using DNaseI-treated total RNA from the brain of adult rats (age, 2 months). In the upper panel of Fig. 7, the agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide shows the results of RT-multiplex PCR using 10 ng of DNaseI-treated total RNA as the template. The sizes of the PCR products obtained were those expected from the published sequences for the subunits Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1 and SUR2 using the chosen primers (411 bp for Kir6.1, 385 bp for Kir6.2, 388 bp for SUR1 and 501 bp for SUR2). The specificity of the products was further tested by restriction analysis. The lower panel of Fig. 7 shows the selected restriction enzymes together with the size of the expected restriction fragments for the different KATP channel subunits. Restriction digestion of the PCR products resulted in two specific fragments (seen as faint bands in the gel) of the size expected for the respective KATP channel subunit, except for the PCR product of Kir6.2 where the smaller restriction fragment was too small to be detected on the gel. These results demonstrate that the primers chosen specifically amplify cDNA for the KATP channel subunits (Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1 and SUR2) and that mRNA for all of the subunits is present in adult rat brain. Furthermore, an amplification product encoding the NMDA receptor subunits NR2A-C is shown on the agarose gel (upper panel of Fig. 7). Of these, NR2A and NR2B subunit mRNAs are known to be present in CA1 pyramidal cells of 10- to 15-day-old rats (Garaschuk et al. 1996). Therefore, the detection of these subunits was used as a positive control for the RT-PCR reaction in the subsequent single-cell RT-PCR experiments on pyramidal cells for neurones in which neither Kir nor SUR subunits could be detected. By optimizing the PCR conditions, we were able to detect transcripts of all KATP channel subunits down to 10 pg of cDNA derived from adult rat brain total RNA. To rule out contamination in all RT-PCR experiments with total RNA, controls with water instead of RNA or cDNA, and with RNA but without reverse transcriptase in the RT reaction were performed in parallel (not shown).

mRNA distribution of KATP channel subunits in single hippocampal neurones

After establishing the selectivity and sensitivity of the PCR method to detect mRNA for all KATP channel subunits in total RNA from rat brain, the approach was applied to single hippocampal cells. We selected CA1 pyramidal cells and interneurones because the lowest and highest current responses to diazoxide were observed in these two cell types (Fig. 6). Figure 8 shows two typical examples of the single-cell RT-PCR results for single hippocampal neurones. On the left, the PCR products of a CA1 pyramidal cell are presented. In this cell, only SUR2 together with the positive control NR2A-C, but no Kir subunit mRNA could be detected. The right part of the figure illustrates an interneurone from the stratum radiatum of the CA1 region in which mRNA for Kir6.2 together with mRNA for SUR1 was detected.

Figure 8. KATP channel subunit mRNA in single hippocampal neurones.

The cytoplasm of single cells was submitted to RT-multiplex PCR, and the reaction products were separated in agarose gel in the presence of the molecular weight marker pGEM (M) and stained with ethidium bromide. The scale to the left of each gel indicates the fragment size (in bp). The CA1 pyramidal cell (cell 67) expressed the SUR2 and NR2A-C subunit mRNAs, whereas the interneurone from stratum radiatum CA1 (cell 59) showed expression of Kir6.2 and SUR1 mRNA.

Table 1 summarizes the KATP channel subunit mRNA combinations detected in eighteen pyramidal cells and twelve interneurones. mRNA for Kir6.1 was found in nearly 40 % of both cell types, whereas mRNA for Kir6.2 as well as for SUR1 was much more frequently detected in interneurones than in pyramidal cells. Thus, in interneurones, the most common subunit mRNA combination, found in seven of twelve cells examined, was Kir6.2 together with SUR1. In all interneurones examined, at least one KATP channel subunit mRNA was present. Thus, a simultaneous amplification of NR2A-C subunit mRNAs was not necessary in these cells. Interestingly, mRNA for SUR2 was detected more frequently in pyramidal cells (5/18, 28 %) than in interneurones (1/12, 8 %). However, in most of these cells that expressed mRNA for SUR2, mRNA for a Kir subunit, which is essential for the formation of KATP channels, was missing. Using the criterion that the expression of the subunit Kir6.1 together with the subunit SUR1 or the subunit Kir6.2 together with one of the subunits SUR1 or SUR2 is required to form functional KATP channels, we found that only 17 % of the CA1 pyramidal cells, but 75 % of all interneurones were able to form KATP channels.

Table 1.

Expression patterns of KATP channel subunits in pyramidal cells and interneurones

| Cell | Kir6.1 | Kir6.2 | SUR1 | SUR2 | NR2A–C | KATP channels possible |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyramidal cell | ||||||

| 50 | — | — | — | + | + | no |

| 52 | — | + | — | — | — | no |

| 53 | + | + | + | + | + | yes |

| 54 | — | — | — | + | + | no |

| 61 | + | + | — | — | — | no |

| 63 | + | + | — | + | + | yes |

| 67 | — | — | — | + | + | no |

| 68 | + | + | + | — | + | yes |

| 73 | — | — | — | — | + | no |

| 74 | — | + | — | — | + | no |

| 75 | — | — | — | — | + | no |

| 76 | + | — | — | — | + | no |

| 77 | — | — | — | — | + | no |

| 79 | + | — | — | — | + | no |

| 80 | + | + | — | — | + | no |

| 81 | — | — | — | — | + | no |

| 82 | — | — | — | — | + | no |

| 83 | — | + | — | — | + | no |

| Interneurone | ||||||

| 55 | + | + | + | + | nt | yes |

| 56 | + | — | + | — | nt | yes |

| 59 | — | + | + | — | nt | yes |

| 64 | — | + | + | — | nt | yes |

| 65 | + | — | — | — | nt | no |

| 66 | — | + | + | — | nt | yes |

| 69 | — | — | + | — | nt | no |

| 71 | + | — | + | — | nt | yes |

| 72 | + | + | — | — | nt | no |

| 84 | — | + | + | — | nt | yes |

| 85 | — | + | + | — | nt | yes |

| 86 | — | + | + | — | nt | yes |

The cytoplasm of 18 CA1 pyramidal cells and 12 interneurones from stratum radiatum CA1 was submitted to the RT-multiplex PCR protocol. For pyramidal cells, the primers for KATP channel subunits and for NR2A–C were present, whereas for interneurones the primers for NR2A–C were absent and the possible presence of NR2A–C was not tested (nt) in these cells. The presence of a subunit mRNA is marked by +, the absence by —. All interneurones tested contained the mRNA for at least one KATP channel subunit. If Kir6.1 together with SUR1, Kir6.2 with SUR1 or Kir6.2 with SUR2 was present in a cell, the possibility of forming KATP channels was denoted as yes.

DISCUSSION

In our experiments, two different strategies were applied to demonstrate the presence of KATP channels in individual, identified hippocampal cells: the current responses to KATP channel modifiers were analysed with the patch-clamp technique, and KATP channel subunit mRNA was identified using the RT-PCR method. Most of the hippocampal cell types studied electrophysiologically, except for passive glial cells, may express KATP channels. The proportion of cells expressing channels and the current density were, however, very different in the individual cell types. In the cells with the highest and lowest current densities, CA1 interneurones and CA1 pyramidal cells, respectively, a single-cell RT-PCR analysis showed a heterogeneous pattern of Kir and SUR subunit expression. From the mRNA expression pattern, only a small proportion of pyramidal cells but most interneurones have mRNA compositions that could result in functional KATP channels. These proportions are similar to those obtained from the electrophysiological analysis.

Diversity of KATP channel currents in hippocampal cells

KATP channels in various tissues can be activated by K+ channel openers and blocked by K+ channel inhibitors (for a review on the pharmacology of KATP channels see Edwards & Weston, 1993). Unfortunately, these agents may not be specific for KATP channels but could also modify other types of ion channel in neuronal cells. Thus, the opener diazoxide (at a high concentration of 0.65 mM) has been claimed to inhibit numerous components of voltage-dependent inward and outward currents in CA1 pyramidal cells (Erdemli & Krnjevi´c, 1995), and the inhibitor tolbutamide may block several types of Ca2+- and voltage-dependent K+ channels in these cells (Erdemli & Krnjevi´c, 1996). To avoid such ambiguities, five criteria were used in our electrophysiological measurements to identify KATP channels. (1) Application of 0.3 mM diazoxide induced an outward current (Figs 2, 3, 4A and 5) that (2) could be inhibited by 0.5 mM tolbutamide (Figs 2, 3 and 4A) or 20 μm glibenclamide. (3) Outward currents could be activated not only by diazoxide, but also when cells were dialysed by an ATP-free pipette solution (Fig. 3). Under these conditions, KATP channels are expected to become unblocked after a fall of the intracellular ATP concentration, and slowly developing outward currents are indicative of the presence of these channels in substantia nigra neurones (Röper & Ashcroft, 1995) and in hippocampal cells (present study). (4) The reversal potential of the diazoxide-induced current was at the calculated K+ equilibrium potential of -102 mV (Fig. 5), whereas the equilibrium potential for Ca2+ is positive and that for Cl− near 0 mV for the external and internal solutions used in our experiments. Hence, the currents induced by diazoxide indeed arise from the activation of K+-selective ion channels. (5) The current-voltage relationship of the diazoxide-induced currents was almost linear between -60 and -80 mV (Fig. 5). This is a characteristic property of KATP channels (e.g. see Noma, 1983) and excludes all types of voltage-dependent K+ channels (A-type K+ channels, delayed rectifier K+ channels) that are activated by depolarizing pulses to voltages > -50 mV.

As shown in Fig. 4B and in the lower part of Fig. 6, not all types of hippocampal cells studied fulfilled the criteria. In particular, many cells did not respond to diazoxide and tolbutamide. The fraction of responding cells depended on the cell type and was largest in complex glial cells (all cells responded) and smallest in CA1 pyramidal cells (only 26 % responded). The cells that respond and those that do not respond could constitute two distinct populations of neurones with and without functional KATP channels, respectively.

Not only the fraction of cells responding to diazoxide and tolbutamide but also the amplitude of the diazoxide-induced currents in responding cells varies with the cell type, with the largest currents observed for interneurones in the stratum radiatum of CA1 (upper panel of Fig. 6). Interestingly, diazoxide activated the smallest currents in CA1 pyramidal neurones, which was also the cell type with the lowest fraction of responding cells. It is important to note that this is the hippocampal cell type on which most previous electrophysiological measurements were performed (Erdemli & Krnjevi´c, 1996; Hyllienmark & Brismar, 1996; Fujimura et al. 1997). Thus our new results show that KATP channels in non-pyramidal cells are present at much higher densities than in pyramidal neurones and therefore may be important for hippocampal function.

KATP channel subunits in rat brain and in hippocampal neurones

KATP channels are heteromultimers composed of four inwardly rectifying potassium channel subunits Kir6.x and four sulphonylurea receptors SUR (Clement et al. 1997; Inagaki et al. 1997; Shyng & Nichols, 1997). The subunit composition of a KATP channel determines the conductance, the blocking potency of ATP and other nucleotides and the pharmacological profile of the channel. Thus, KATP channels of pancreatic β cells, composed of Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits (Inagaki et al. 1995a), are sensitive to ATP, diazoxide and tolbutamide, whereas Kir6.2 together with the isoform SUR2A of SUR2 forms KATP channels typical of heart and skeletal muscle with sensitivities to ATP and glibenclamide, but not to diazoxide (Inagaki et al. 1996). Kir6.1 together with SUR1 subunits (Ämmäläet al. 1996) as well as Kir6.2 together with the isoform SUR2B of SUR2 (Isomoto et al. 1996) combine to form ATP-, diazoxide- and tolbutamide-sensitive KATP channels. Finally, nucleoside diphosphate-sensitive, but ATP-insensitive K+ channels which are activated by diazoxide and blocked by tolbutamide may be formed from Kir6.1 and SUR2B subunits (Yamada et al. 1997). Our whole-cell experiments do not allow us to differentiate between the various subunit combinations, nor do they prove or exclude the presence of Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1 or SUR2 in the hippocampus. Of these subunits, Kir6.1 (Inagaki et al. 1995b), Kir6.2 (Inagaki et al. 1995a) and SUR2 (Inagaki et al. 1996) have previously been detected in rat brain by Northern blot analysis. On the other hand, SUR1 was reported to be expressed only in small amounts in rat brain (Inagaki et al. 1996). The presence of all known KATP channel subunits (Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1 and SUR2) in the rat brain was shown by Karschin et al. (1998) and in our experiments (Fig. 7) using PCR techniques.

In the hippocampus of the rat, in situ hybridization analysis revealed overlapping expression patterns of Kir6.2 and SUR1 (Karschin et al. 1997). This was further confirmed in another study by RT-PCR experiments on cultured hippocampal neurones, where mRNA for Kir6.2 and SUR1, but not for the SUR2 subunit was detected (Lauritzen et al. 1997). In this study we show for the first time the expression of specific KATP channel subunit mRNAs in distinct hippocampal cell types. To obtain this information, we applied the single-cell RT-PCR method to CA1 pyramidal cells and to interneurones from the stratum radiatum of CA1. As shown in Fig. 8 and Table 1, mRNA not only for Kir6.2 and SUR1, but also for Kir6.1 and SUR2 could be detected in both cell types, but with clearly different incidences. In contrast, only Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits were found in individual dorsal vagal neurones and surrounding glial cells of rat brainstem slices (Karschin et al. 1998), and only Kir6.1 and SUR1 subunits in rat striatal cholinergic interneurones (Lee et al. 1998). Although our primers did not discriminate between the SUR2 isoforms SUR2A and SUR2B, the SUR2 subunits detected in single hippocampal cells most probably correspond to SUR2B, since only SUR2B, not SUR2A, was reported to be present in the forebrain of the mouse (Isomoto et al. 1996).

According to our experiments on rat hippocampus, the most frequent mRNA subunit combination that can result in functional KATP channels in CA1 pyramidal cells and interneurones was Kir6.2 together with SUR1. This combination, originally found for pancreatic KATP channels, was detected in 75 % of all cells in which KATP channels are possible (Table 1). In interneurones, 58 % of the cells examined showed this combination. However, within each population there were also cells with other subunit combinations (e.g. cells 63 and 71), and several cells where more than one combination could form KATP channels (e.g. cells 53 and 55). Thus, individual neurones of each CA1 cell-type studied (pyramidal cells and interneurones of the stratum radiatum) may express different types of KATP channels. Similarly, heterogeneous properties of single KATP channels were described in the hypothalamus (Ashford et al. 1990) and in other areas of the rat brain (Ohno-Shosaku & Yamamoto, 1992; Schwanstecher & Panten, 1993, 1994).

The most remarkable result of our single-cell RT-PCR analysis is the striking difference between the percentages of CA1 pyramidal cells and interneurones in which KATP channels are possible (Table 1). Thus, only 17 % of the pyramidal cells, but 75 % of the interneurones showed a mRNA subunit combination (Kir6.1 together with SUR1, Kir6.2 together with SUR1 or SUR2) that can result in functional KATP channels. This is in agreement with the distinct percentages of the two cell types that showed diazoxide- and tolbutamide-sensitive whole-cell currents (26 and 89 %, see lower panel of Fig. 6).

Conclusions

A striking heterogeneity in the expression pattern of functional KATP channels was found in this study for various cell types of the hippocampus. Our results, based on electrophysiological measurements and single-cell RT-PCR experiments, firmly establish the differential, cell-type specific expression of KATP channels in hippocampal cells. They extend previous glibenclamide binding studies (Mourre et al. 1991) and an in situ hybridization analysis of the distribution of KATP channel subunits (Karschin et al. 1997). Furthermore, we report that in the hippocampus KATP channels are not only present in neurones but also in glial cells. The different expression levels of KATP channels in the hippocampus could be related to the differential responses of hippocampal cell types to ischaemic insult or metabolic inhibition. Thus, CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurones are much more sensitive to anoxia than granule cells of the dentate gyrus (Krnjevi´c & Ben-Ari, 1989). Furthermore, CA1 pyramidal cells in the adult rat are much more vulnerable to ischaemia than CA1 interneurones (Fryd Johansen et al. 1983). We propose that these differences are due to the higher number of functional KATP channels in granule cells and interneurones compared with pyramidal cells. Thus, a decline of the intracellular ATP concentration following ischaemia or metabolic inhibition would activate more KATP channels in granule cells and interneurones than in pyramidal cells. Consequently, a stronger hyperpolarization, a more effective damping of electrical activity and a better preservation of cellular ATP levels would occur in granule cells and interneurones than in pyramidal cells. A protective role of KATP channels was also concluded from the effects of openers of these channels which prevent the ischaemia-induced neuronal death in the rat hippocampus (Heurteaux et al. 1993).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Jens Eilers for help with the two-photon microscopy and Dr Karl Kafitz for introduction to the method of neurobiotin labelling. Furthermore, we are grateful to Reiko Trautmann and Heide Krempel for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Schwerpunkt: K+ Kanäle).

References

- Alzheimer C, ten Bruggencate G. Actions of BRL 34915 (cromakalim) upon convulsive discharges in guinea pig hippocampal slices. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1988;337:429–434. doi: 10.1007/BF00169535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ämmälä C, Moorhouse A, Ashcroft FM. The sulphonylurea receptor confers diazoxide sensitivity on the inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir6.1 expressed in human embryonic kidney cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:709–714. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft SJH, Ashcroft FM. Properties and functions of ATP-sensitive K-channels. Cellular Signalling. 1990;2:197–214. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(90)90048-f. 10.1016/0898-6568(90)90048-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford MLJ, Boden PR, Treherne JM. Glucose-induced excitation of hypothalamic neurones is mediated by ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Pflügers Archiv. 1990;415:479–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00373626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audinat E, Lambolez B, Rossier J, Crépel F. Activity-dependent regulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit expression in rat cerebellar granule cells. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;6:1792–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Analytical Biochemistry. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement JP, IV, Kunjilwar K, Gonzalez G, Schwanstecher M, Panten U, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Association and stoichiometry of KATP channel subunits. Neuron. 1997;18:827–838. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter MA, Ayala GF. Cellular mechanisms of epilepsy: A status report. Science. 1987;237:157–164. doi: 10.1126/science.3037700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodt HU, Zieglgänsberger W. Visualizing unstained neurons in living brain slices by infrared DIC-videomicroscopy. Brain Research. 1990;537:333–336. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90380-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA, Konnerth A, Sakmann B, Takahashi T. A thin slice preparation for patch-clamp recordings from neurones of the mammalian central nervous system. Pflügers Archiv. 1989;414:600–612. doi: 10.1007/BF00580998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Weston AH. The pharmacology of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1993;33:597–637. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdemli G, Krnjevi´c K. Actions of diazoxide on CA1 neurons in hippocampal slices from rats. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1995;73:608–618. doi: 10.1139/y95-077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdemli G, Krnjevi´c K. Tolbutamide blocks Ca2+- and voltage-dependent K+ currents of hippocampal CA1 neurons. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;304:37–47. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryd Johansen F, Balslev Jørgensen M, Diemer NH. Resistance of hippocampal CA-1 interneurons to 20 min of transient cerebral ischemia in the rat. Acta Neuropathologica. 1983;61:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00697393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura N, Tanaka E, Yamamoto S, Shigemori M, Higashi H. Contribution of ATP-sensitive potassium channels to hypoxic hyperpolarization in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77:378–385. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.1.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaschuk O, Schneggenburger R, Schirra C, Tempia F, Konnerth A. Fractional Ca2+ currents through somatic and dendritic glutamate receptor channels of rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;491:757–772. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guatteo E, Federici M, Siniscalchi A, Knöpfel T, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Whole cell patch-clamp recordings of rat midbrain dopaminergic neurons isolate a sulphonylurea- and ATP-sensitive component of potassium currents activated by hypoxia. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:1239–1245. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurteaux C, Bertaina V, Widmann C, Lazdunski M. K+ channel openers prevent global ischemia-induced expression of c-fos, c-jun, heat shock protein, and amyloid β-protein precursor genes and neuronal death in rat hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1993;90:9431–9435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyllienmark L, Brismar T. Effect of metabolic inhibition on K+ channels in pyramidal cells of the hippocampal CA1 region in rat brain slices. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:155–164. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, IV, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Reconstitution of IKATP: An inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science. 1995a;270:1166–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, IV, Wang C-Z, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Seino S. A family of sulfonylurea receptors determines the pharmacological properties of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Neuron. 1996;16:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Seino S. Subunit stoichiometry of the pancreatic β-cell ATP-sensitive K+ channel. FEBS Letters. 1997;409:232–236. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Tsuura Y, Namba N, Masuda K, Gonoi T, Horie M, Seino Y, Mizuta M, Seino S. Cloning and functional characterization of a novel ATP-sensitive potassium channel ubiquitously expressed in rat tissues, including pancreatic islets, pituitary, skeletal muscle, and heart. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995b;270:5691–5694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomoto S, Kondo C, Yamada M, Matsumoto S, Higashiguchi O, Horio Y, Matsuzawa Y, Kurachi Y. A novel sulfonylurea receptor forms with BIR (Kir6.2) a smooth muscle type ATP-sensitive K+ channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:24321–24324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karschin A, Brockhaus J, Ballanyi K. KATP channel formation by the sulphonylurea receptors SUR1 with Kir6.2 subunits in rat dorsal vagal neurons in situ. Journal of Physiology. 1998;509:339–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.339bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karschin C, Ecke C, Ashcroft FM, Karschin A. Overlapping distribution of KATP channel-forming Kir6.2 subunit and the sulfonylurea receptor SUR1 in rodent brain. FEBS Letters. 1997;401:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Hama K. Two subtypes of non-pyramidal cells in rat hippocampal formation identified by intracellular recording and HRP injection. Brain Research. 1987;411:190–195. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90700-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krnjevi´c K, Ben-Ari Y. Anoxic changes in dentate granule cells. Neuroscience Letters. 1989;107:89–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90796-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacaille J-C, Schwartzkroin PA. Stratum lacunosum-moleculare interneurons of hippocampal CA1 region. I. Intracellular response characteristics, synaptic responses, and morphology. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:1400–1410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01400.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambolez B, Audinat E, Bochet P, Crépel F, Rossier J. AMPA receptor subunits expressed by single Purkinje cells. Neuron. 1992;9:247–258. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen I, De Weille JR, Lazdunski M. The potassium channel opener (−)-cromakalim prevents glutamate-induced cell death in hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;69:1570–1579. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Dixon AK, Freeman TC, Richardson PJ. Identification of an ATP-sensitive potassium channel current in rat striatal cholinergic interneurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:441–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.441bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin F, Beaulieu C, Lacaille J-C. Membrane properties and synaptic currents evoked in CA1 interneuron subtypes in rat hippocampal slices. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:1–16. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott DD, Turner DA, Okazaki MM, Lewis DV. Interneurons of the dentate-hilus border of the rat dentate gyrus: Morphological and electrophysiological heterogeneity. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:3990–4005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-03990.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourre C, Ben Ari Y, Bernardi H, Fosset M, Lazdunski M. Antidiabetic sulfonylureas: localization of binding sites in the brain and effects on the hyperpolarization induced by anoxia in hippocampal slices. Brain Research. 1989;486:159–164. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourre C, Widmann C, Lazdunski M. Specific hippocampal lesions indicate the presence of sulfonylurea binding sites associated to ATP-sensitive K+ channels both post-synaptically and on mossy fibers. Brain Research. 1991;540:340–344. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma A. ATP-regulated K+ channels in cardiac muscle. Nature. 1983;305:147–148. doi: 10.1038/305147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Yamamoto C. Identification of an ATP-sensitive K+ channel in rat cultured cortical neurons. Pflügers Archiv. 1992;422:260–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00376211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant T, Schirra C, Garaschuk O, Rossier J, Konnerth A. Molecular determinants of NMDA receptor function in GABAergic neurones of rat forebrain. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;499:47–63. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röper J, Ashcroft FM. Metabolic inhibition and low internal ATP activate K-ATP channels in rat dopaminergic substantia nigra neurones. Pflügers Archiv. 1995;430:44–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00373838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruano D, Perrais D, Rossier J, Ropert N. Expression of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs by layer V pyramidal cells of the rat primary visual cortex. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;9:857–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychlik W, Rhoads RE. A computer program for choosing optimal oligonucleotides for filter hybridization, sequencing and in vitro amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Research. 1989;17:8543–8551. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.21.8543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlösser B, ten Bruggencate G, Sutor B. The intracellular tracer Neurobiotin alters electrophysiological properties of rat neostriatal neurons. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;249:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanstecher C, Panten U. Tolbutamide- and diazoxide-sensitive K+ channel in neurons of substantia nigra pars reticulata. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1993;348:113–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00168546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanstecher C, Panten U. Identification of an ATP-sensitive K+ channel in spiny neurons of rat caudate nucleus. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;427:187–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00585961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seress L, Pokorny J. Structure of the granular layer of the rat dentate gyrus. A light microscopic and Golgi study. Journal of Anatomy. 1981;133:181–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng S-L, Nichols CG. Octameric stoichiometry of the KATP channel complex. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:655–664. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M-L, Auer RN, Siesjö BK. The density and distribution of ischemic brain injury in the rat following 2–10 min of forebrain ischemia. Acta Neuropathologica. 1984;64:319–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00690397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhäuser C, Jabs R, Kettenmann H. Properties of GABA and glutamate responses in identified glial cells of the mouse hippocampal slice. Hippocampus. 1994;4:19–36. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Isomoto S, Matsumoto S, Kondo C, Shindo T, Horio Y, Kurachi Y. Sulphonylurea receptor 2B and Kir6.1 form a sulphonylurea-sensitive but ATP-insensitive K+ channel. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;499:715–720. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawar C, Plant TD, Neumcke B. Striking heterogeneity in the expression pattern of functional KATP channels in the rat hippocampus. Pflügers Archiv. 1997;434(suppl. 5) R105 (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Zawar C, Schirra C, Plant TD, Konnerth A, Neumcke B. Distinct KATP channel subunits in pyramidal cells and interneurones of the rat hippocampus revealed by single cell-RT-PCR. Pflügers Archiv. 1998;435(suppl. 6) R56 (Abstract) [Google Scholar]