Abstract

Ryanodine receptor (RyR) Ca2+ channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of skeletal muscle are regulated by the 12 kDa FK506- (or rapamycin-) binding protein (FKBP12). Rapamycin can also activate RyR channels with FKBP12 removed, suggesting that compounds with macrocyclic lactone ring structures can directly activate RyRs. Here we tested this hypothesis using two other macrocyclic lactone compounds, ivermectin and midecamycin.

Rabbit skeletal RyRs were examined in lipid bilayers. Ivermectin (cis, 0.66–40 μm) activated six of eight native, four of four control-incubated and eleven of eleven FKBP12-‘stripped’ RyR channels. Midecamycin (cis, 10–30 μm) activated three of four single native channels, six of eight control-incubated channels and six of seven FKBP12-stripped channels. Activity declined when either drug was washed out.

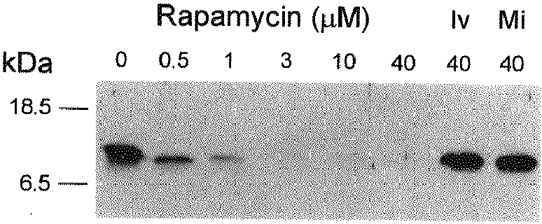

Neither ivermectin nor midecamycin removed FKBP12 from RyRs. Western blots of terminal cisternae (TC), incubated for 15 min at 37 °C with 40 μm ivermectin or midecamycin, showed normal amounts of FKBP12. In contrast, no FKBP12 was detected after incubation with 40 μm rapamycin.

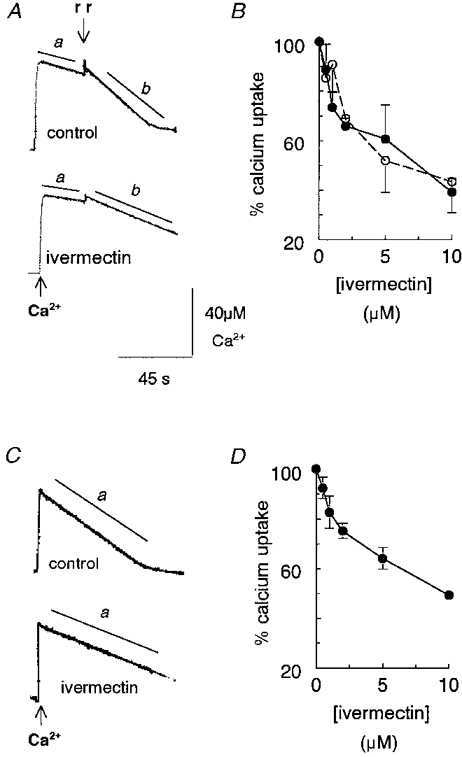

Ivermectin reduced Ca2+ uptake by the SR Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase. Ca2+ uptake by TC fell to ∼40% in the presence of ivermectin (10 μm), both with and without 10 μm Ruthenium Red. Ca2+ uptake by longitudinal SR also fell to ∼40% with 10 μm ivermectin. Midecamycin (10 μm) reduced Ca2+ uptake by TC vesicles to ∼76% without Ruthenium Red and to ∼90% with Ruthenium Red.

The rate of rise of extravesicular [Ca2+] increased ∼2-fold when 10 μm ivermectin was added to TC vesicles that had been partially loaded with Ca2+ and then Ca2+ uptake blocked by 200 nm thapsigargin. Ivermectin also potentiated caffeine-induced Ca2+ release to ∼140% of control. These increases in Ca2+ release were not seen with midecamycin.

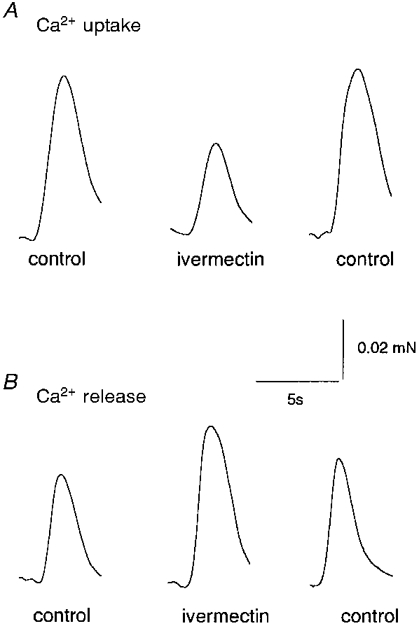

Ivermectin, but not midecamycin, reversibly reduced Ca2+ loading in four of six skinned rat extensor digitorum longus (EDL) fibres to ∼90%, and reversibly increased submaximal caffeine-induced contraction in five of eight fibres by ∼110% of control. Neither ivermectin nor midecamycin altered twitch or tetanic tension in intact EDL muscle fibres within 20 min of drug addition.

The results confirm the hypothesis that compounds with a macrocyclic lactone ring structure can directly activate RyRs. Unexpectedly, ivermectin also reduced Ca2+ uptake into the SR. These effects of ivermectin on SR Ca2+ handling may explain some effects of the macrolide drugs on mammals.

The ryanodine receptor (RyR) is a large conductance ion channel which allows Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of skeletal muscle to initiate contraction in response to sarcolemmal depolarization (Dulhunty, 1992). The contraction is terminated when Ca2+ is pumped back into the SR by the Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase. The functional skeletal RyR Ca2+-release channel is a homotetrameric complex of RyR monomers (Mr∼560 000) and four FK506-binding proteins (FKBP12, Mr∼12 000), each of which is tightly bound to a RyR monomer (Timerman et al. 1993; Brillantes et al. 1994; Wagenknecht et al. 1996). The immunosuppressive drugs FK506 and rapamycin bind with nanomolar affinities to FKBP12, causing the binding protein to dissociate from the RyR tetramer as the drug-bound protein complex (Jayaraman et al. 1992; Timerman et al. 1993). The RyRs, ‘stripped’ of their FKBP12 co-proteins, display increased channel activity (Mayrleitner et al. 1994; Ahern et al. 1997a). We found that rapamycin also has an FKBP12-independent action on the RyR, since the release channel is activated by rapamycin even when ‘stripped’ of FKBP12. Thus we postulated that there is a binding site on the RyR for compounds with macrocyclic lactone structures similar in size to rapamycin and FK506 (Ahern et al. 1997b).

To test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of the anti-helminthic ivermectin (Campbell, 1989) and the antibiotic midecamycin (Hamilton-Miller, 1992; Mazzei et al. 1993). The chemical structures of both drugs contain a sixteen-membered macrocyclic lactone ring. Ivermectin (22,23-dihydroavermectin B1a) is a member of the avermectin class of macrocyclic lactones, isolated from Streptomyces avermitilis, which are potent antihelminthics and insecticides and are used to treat onchocerciasis (river blindness) in humans (Campbell, 1989). The EC50 for the biological activity of avermectins is strongly correlated with their ability to activate glutamate-sensitive channels and their binding affinity for nematode membrane preparations (Arena et al. 1995). The antihelminthic activity of ivermectin is believed to depend on its paralysing the pharyngeal muscle and preventing feeding (Dent et al. 1997; Brownlee et al. 1997; Geary et al. 1998). Avermectin B1a can both activate (nanomolar concentrations) and inhibit (micromolar concentrations) GABA-gated Cl− currents in mammalian neurones (Bloomquist, 1993; Huang & Casida, 1997). There are no previous reports of ivermectin affecting mammalian skeletal muscle, or of midecamycin acting on ion channels. Quinolidomycin A1, which has a 60-membered macrocyclic lactone ring structure, activates Ca2+ release from SR vesicles, but only about 50 % of this release is inhibited by the RyR channel blockers Ruthenium Red, procaine and Mg2+ (Ohkura et al. 1996).

The results presented here show that micromolar ivermectin reversibly activated native RyR channels incorporated into planar lipid bilayers. Micromolar midecamycin also reversibly activated some, but not all, channels. Since we found here that these macrocyclic lactones did not dissociate FKBP12 from the RyR, and both drugs reversibly altered FKBP12-‘stripped’ RyR activity, the results provide strong evidence that macrocyclic lactones exert their effects by acting directly on the RyR channel complex. Ivermectin increased Ca2+ release from SR vesicles and from skinned muscle fibres, not only by activating the RyR channels but also by inhibiting Ca2+ uptake by the SR Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase. Midecamycin reduced Ca2+ uptake by the SR, but to a lesser extent than ivermectin and had no detectable action on Ca2+ release from SR vesicles or on skinned fibres. These effects of micromolar concentrations of ivermectin could contribute to symptoms of drug overdose in mammals.

METHODS

Materials

Rapamycin was obtained from Calbiochem and as a gift from Wyeth-Ayerst (Princeton, NJ, USA), ivermectin was a gift from Merck, Sharp & Dohme (Sydney, Australia), and ryanodine was obtained from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (San Diego, CA, USA) and Latoxan (Rosans, France). Other chemicals and biochemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich. Stock solutions of ivermectin and midecamycin were prepared in ethanol or DMSO.

Vesicle preparation

New Zealand White rabbits were killed by captive bolt and the back and leg muscles removed immediately. SR vesicles were isolated as described by Saito et al. (1984) with minor modifications (Ahern et al. 1994, 1997a). TC vesicles were obtained from the 38 %-45 % sucrose interface, and longitudinal SR (LSR) from the 32 %-34 % sucrose interface. FKBP12 was removed from TC vesicles by incubation with either 10 or 20 μm rapamycin for 15-20 min at 37°C. ‘Control-incubated’ channels were incubated in the same way, but without rapamycin. The amount of FKBP12 remaining bound was assessed by immunostaining Western blots of TC vesicles with antipeptide antibodies raised against peptides corresponding to the N-terminal sequence of FKBP12. Details of the FKBP12 ‘stripping’ procedure, production of antipeptide antibodies, electrophoresis and Western blotting are given in Ahern et al. (1997a).

Lipid bilayers and recording and analysis of single channel activity

Experiments were carried out at 20-25°C. The techniques are described in detail in Ahern et al. (1994) and Laver et al. (1995). Bilayers were formed from phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylcholine (5:3:2 w/w) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL, USA) across an ∼250 μm diameter aperture in the wall of a 1.5 ml Delrin cup (Cadillac Plastics, Australia). TC vesicles (final concentration, 10 μg ml−1) and drugs were added to the cis chamber. The normal cis solution contained 250 mM CsCl, 1 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM Tes (pH 7.4 with CsOH), and the trans solution contained 50 mM CsCl, 1 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM Tes (pH 7.4). Changes in free Ca2+ concentration in the cis solution, and drug washout, were achieved by perfusion with appropriate solutions. Bilayer potential was controlled and currents recorded using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments). Bilayer potentials are given relative to the trans chamber.

Channel activity was recorded at 1 kHz (10-pole low-pass Bessel, -3 dB) and digitized at 2 or 5 kHz. Analysis of single channel records (Channel 2, P. W. Gage & M. Smith, John Curtin School of Medical Research, Australian National University) yielded channel open probability (Po), frequency of events (Fo), open times, closed times and mean open or closed times (To or Tc), as well as mean current (I). The event discriminator was set above the baseline noise at ∼20 % of the maximum current, rather than the usual 50 %, so that openings to both subconductance and maximum conductance levels were included in the analysis.

Single channel activity of RyRs fell into two modes, either high activity (Po > 0.1), or low activity (Po < 0.01). The mode of the control activity in a channel was maintained for the duration of the experiment and was reflected in the activity recorded in the presence of drugs. The different modes led to large standard errors in average data. The different modes were also seen in FKBP12-stripped and control-incubated channels. In some cases, the majority of channels in one preparation showed low activity, while most channels in another preparation showed high activity. This can be seen in data presented in Table 2, where FKBP12-stripped channels in one experiment had an average Po of 0.007 ± 0.004, but average Po values of 0.183 ± 0.117 and 0.297 ± 0.159 in two other experiments (means ±s.e.m.).

Table 2.

Reversible effects of ivermectin on single channel properties of native, control-incubated and FKBP12-stripped RyRs

| RyR | n | Po | To (ms) | Fo (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native (10−3 M Ca2+) | ||||

| Control | 8 | 0.015 ± 0.009 | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 21 ± 6 |

| Ivermectin (0.66–4.0 μM) | 8 | 0.079 ± 0.019** | 1.21 ± 0.22* | 68 ± 10** |

| Control incubated (10−7 M Ca2+) | ||||

| Control | 4 | 0.013 ± 0.004 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 6 ± 3 |

| Ivermectin (40 μM) | 4 | 0.241 ± 0.066** | 5.6 ± 2.5** | 51 ± 11** |

| Washout | 4 | 0.096 ± 0.059* | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 26 ± 12* |

| FKBP12 stripped (10−4 M Ca2+) | ||||

| Control | 4 | 0.007 ± 0.003 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 8 ± 4 |

| Ivermectin (4.0 μM) | 4 | 0.023 ± 0.014 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 21 ± 10 |

| FKBP12 stripped (10−4 M Ca2+) | ||||

| Control | 4 | 0.007 ± 0.004 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 8 ± 4 |

| Ivermectin (20–24 μM) | 4 | 0.080 ± 0.040† | 1.8 ± 0.3* | 40 ± 15† |

| FKBP12 stripped (10−7 M Ca2+) | ||||

| Control | 7 | 0.183 ± 0.117 | 6.3 ± 4.0 | 15 ± 10 |

| Ivermectin (34–40 μM) | 7 | 0.404 ± 0.133** | 12.8 ± 6.4 | 46 ± 9* |

| Washout | 7 | 0.274 ± 0.097* | 8.2 ± 2.8 | 40 ± 8 |

Concentrations of ivermectin and cis Ca2+ are given for each set of data. Channel activity was measured over ~60 s periods before and after addition of ivermectin. The data are given as means ± S.E.M. for n channels. Asterisks indicate the significance of the difference between the control and ivermectin values or between ivermectin and recovered (Washout) values using Student's t test on the mean of the logarithm of individual values

P < 0.05

**P < 0.01

Not significantly different from control when tested with Student's t test, but significantly different according to the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (P < 0.05).

Ca2+ uptake into SR vesicles

Ca2+ uptake was measured using a procedure based on Chu et al. (1989). Extravesicular Ca2+ was monitored at 710 nm with the Ca2+ indicator antipyrylazo III, using a Cary 3 Spectrophotometer (Varian, Mulgrave, Victoria, Australia). Identical uptake experiments, performed at 790 nm, showed no changes in optical density (OD) which would alter the rate of Ca2+ uptake measured from recordings at 710 nm. The temperature of the cuvette solution was thermostatically controlled at 25°C and the solution was stirred magnetically during experiments. TC or LSR vesicles (100 μg of protein) were added, to a final volume of 2 ml, to a solution containing (mM): 100 KH2PO4 (pH 7), 1 MgCl2 (86 μm free Mg2+), 1 Na2ATP and 0.2 antipyrylazo III. Ca2+ was added, to a final concentration of 50 μm, and a loading rate was obtained from the decline in OD at 710 nm (slope a, Fig. 5A). Ruthenium Red was then added to a final concentration of 5 μm and the uptake rate in the absence of a Ca2+ efflux through the RyR obtained (slope b, Fig. 5A).

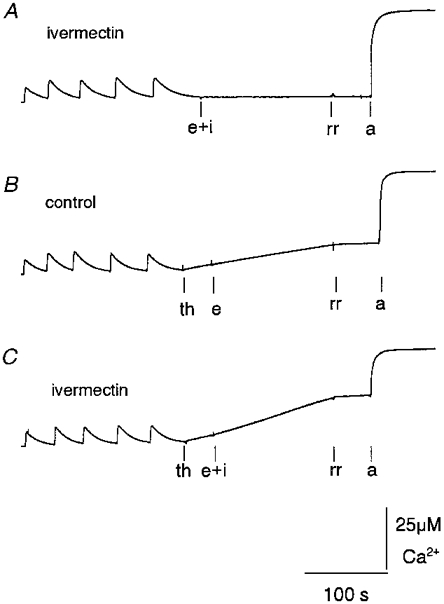

Figure 5. Ivermectin releases Ca2+ from partially loaded TC vesicles in the absence and presence of thapsigargin.

Records of OD changes at 710-790 nm following changes in extravesicular [Ca2+], using antipyrylazo III (500 μm) as the Ca2+ indicator. Extravesicular [Ca2+] increased by ≈4 μm at the start of each record when TC vesicles were added to the cuvette and then declined as Ca2+ was sequestered by the TC vesicles. The following four positive deflections indicate addition of four aliquots of CaCl2 (7.5 μm final concentration). A, ivermectin added with ethanol vehicle (e + i, 10 μm). B, thapsigargin (th, 200 nM) added before ethanol control (e, 0.2 % v/v). C, thapsigargin (200 nM) added before ivermectin (e + i, 10 μm). In A-C, Ruthenium Red (rr, 10 μm) was added before the ionophore A23187 (a, 3 μg ml−1) at the end of each record. The vertical calibration bar shows [Ca2+] (see legend to Fig. 4). In this experiment an increase in [Ca2+] of 25 μm caused an increase of 0.3 OD units.

Ca2+ release from TC vesicles

Ca2+ release was measured as described by Timerman et al. (1993). TC vesicles were added to a solution containing (mM): 100 KH2PO4 (pH 7), 4 MgCl2 (370 μm free Mg2+), 1 Na2ATP and 0.5 antipyrylazo III. Experiments were performed at 710 and 790 nm. Step changes in OD at both wavelengths were seen upon addition of ivermectin or Ruthenium Red to the cuvette and were subtracted from the records shown in Figs 5 and 6. Vesicles were partially loaded with Ca2+, after four sequential additions of CaCl2, each initially increasing the extravesicular [Ca2+] by ∼7.5 μm (Figs 5 and 6). The ability of ivermectin to potentiate caffeine- (0.5-5 mM) induced release of Ca2+ was measured in the presence of thapsigargin (200 nM, added to inhibit Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase activity; Sagara & Inesi, 1991) and an additional 5 mM MgCl2 (added to depress Ca2+ leakage through the RyR which was apparent when the Ca2+ pump was blocked). The Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (3 μg ml−1) was added at the completion of each experiment to release the Ca2+ remaining in the TC vesicles.

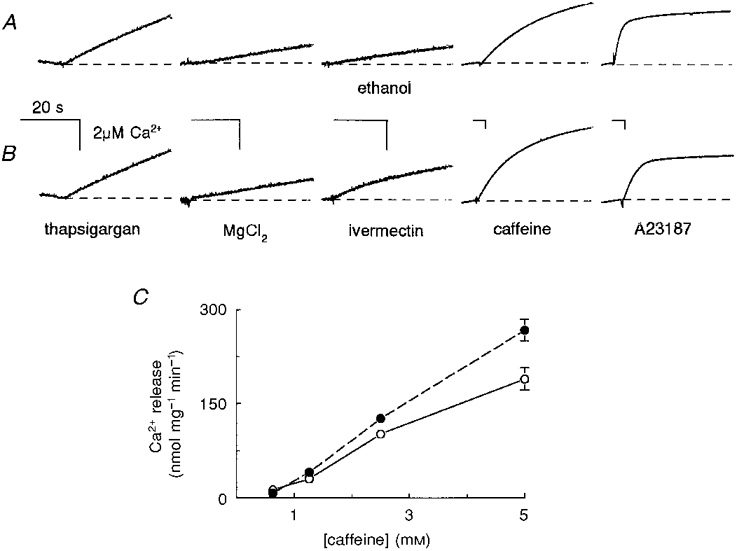

Figure 6. Ivermectin released Ca2+ from TC vesicles and enhanced caffeine-induced Ca2+ release.

A, control records. B, Ca2+ release in the presence of ivermectin. A and B show records of OD changes at 710-790 nm in response to changes in extravesicular [Ca2+], using antipyrylazo III (500 μm) as a Ca2+ indicator. TC vesicles were partially loaded with Ca2+ by adding four aliquots of CaCl2 (each 7.5 μm final concentration) as shown in Fig. 5. The scaling of the records has been adjusted (as indicated by the calibration bars for 20 s and 20 μm Ca2+) to best display the response to each addition (note the changes in the calibration bars with caffeine and A23187). First record, increase in extravesicular [Ca2+] with 200 nM thapsigargin. Second record, reduced rate of Ca2+ release when MgCl2 was added to the solution (to give a total Mg2+ concentration of 9 mM). Third record, Ca2+ release was not altered by addition of 0.25 % (v/v) ethanol (A), but was enhanced by 10 μm ivermectin (B). Fourth record, enhanced rate of release following 5 mM caffeine addition. Final record, all remaining Ca2+ was released from TC vesicles by A23187. C, ivermectin potentiates caffeine-induced Ca2+ release from TC vesicles. Initial rates of Ca2+ release (nmol (mg TC protein)−1 min−1) induced by caffeine (0.6-5 mM) in control (ethanol, 0.25 % v/v, ○) and with ivermectin (10 μm, •). The rate of release shown in C is the initial rate in caffeine minus the preceding rate with ethanol (A) or with ethanol plus ivermectin (B). Data points are means ±s.e.m. (n= 7) using TC vesicles from two SR isolations. The vertical calibration bar shows [Ca2+] (see legend to Fig. 4). In this experiment an increase in [Ca2+] of 2 μm caused an increase of 0.02 OD units.

Skinned fibre experiments

Extensor digitorum longus (EDL) fibres were dissected from male Wistar rats, following asphyxiation by CO2 and cervical dislocation. The fibres were mechanically skinned under paraffin oil (Lamb & Stephenson, 1990). One end of the fibre was attached to an Akers semiconductor force transducer (model AE 875, SensorNor a.s., Horten, Norway) using silk suture and the other end held by clamping forceps. The fibre was lowered sequentially into 2 ml baths containing the following solutions (see Table 1), in order of application: (i) release solution to release all Ca2+ remaining in the SR; (ii) maximum activating solution (pCa, ∼4) to determine the maximum force that could be produced by the contractile proteins; (iii) high relaxing solution (50 mM EGTA) to remove Ca2+; (iv) low relaxing solution (50 μm EGTA) to remove excess EGTA; (v) release solution to confirm that the SR remained depleted of Ca2+; (vi) 30 s in high relaxing solution; (vii) 30 s in low relaxing solution.

Table 1.

Solutions for skinned fibre experiments

| Solution | Hepes (mM) | Mgtotal§ (mM) | EGTA (mM) | Catotal‖ (mM) | HDTA (mM) | NaN3 (mM) | Caffeine (mM) | ATP (mM) | CP (mM) | pCa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAS | 90 | 10.3 (1) | 50 | 50 | — | 1 | — | 8 | 10 | 4.2 |

| HRS | 90 | 10.3 (1) | 50 | — | — | 1 | — | 8 | 10 | 12.8 |

| LRS | 90 | 8.6 (1) | 0.2† | — | 50 | 1 | — | 8 | 10 | 9.4 |

| LS | 90 | 8.6 (1) | 1.0* | — | 50 | 1 | — | 8 | 10 | 7.7 |

| RS | 90 | 2.0 (0.05) | 0.5† | — | 50 | 1 | 30 | 8 | 10 | 9.9 |

| RSSM | 90 | 5.3 (0.25) | 0.5‡ | — | 50 | 1 | 15 | 8 | 10 | 9.9 |

MAS, maximum activating solution; HRS, high relaxing solution; LRS, low relaxing solution; LS, load solution; RS, release solution; RSSM, submaximal release solution. All solutions were adjusted to pH 7.4 using 4 M KOH.

LS was made by adding 100 μl of HRS and 20 μl of 49 mM CaCl2 to 5 ml of LRS (lacking EGTA).

LRS and RS were initially made without EGTA. EGTA was included by adding 20 or 50 μl of HRS, respectively, to 5 ml of LRS or RS immediately before use.

RSSM was made by combining 2.5 ml of LRS (without EGTA) with 2.5 ml of RS (lacking EGTA) and then adding 50 μl of HRS.

Mg2+ was added as MgO; the calculated free [Mg2+] is given in parentheses.

Ca2+ was added as Ca(CO3)2. HDTA, hexamethylenediamine-tetraacetate; CP, creatine phosphate.

The SR was loaded with Ca2+ by exposing the fibre to load solution (pCa, 7.7) in which Ca2+ was moderately buffered. Loading was terminated by exposing the fibre to the low relaxing solution for 30 s. The extent of loading was assessed from the amplitude of the contracture in the release solution (30 mM caffeine, 0.05 mM free Mg2+). The load time required for ∼50 % maximum loading was determined for each fibre. The free [Ca2+] in the solutions was calculated using the program ‘Bound and Determined’ (Marks & Maxfield, 1991).

Caffeine-induced Ca2+ release was examined by maximally loading fibres with Ca2+, followed by 30 s in the low relaxing solution and then the release solution containing 15 mM caffeine and 0.25 mM free Mg2+, which gave ∼50 % maximal release.

Intact fibre experiments

Methods are described in Dulhunty (1991). Small bundles of EDL fibres from adult male rats were dissected and bathed in a Krebs solution containing (mM): 120 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 11 glucose and 2 Tes (pH 7.4). Twitches were elicited at 0.1 Hz, with fused tetanic contractions elicited at 5 min intervals.

Block of the Ca2+ release channel by Ruthenium Red

The Ca2+ release channel blocker Ruthenium Red was used to show either (a) that Ca2+ release was through the RyR in vesicle experiments, or (b) that single channel recordings were from RyRs incorporated into bilayers. Concentrations of Ruthenium Red ranging from 5 to 80 μm were used for different purposes. Ruthenium Red at 5-10 μm was sufficient to substantially reduce Ca2+ release from SR within seconds of application. The same concentrations of Ruthenium Red took 30-60 s to fully block RyRs in bilayer experiments, while 80 μm Ruthenium Red blocked all single channel activity within 10 s. Higher concentrations of Ruthenium Red were used in many bilayer experiments to block the channel before the bilayer broke. Differences in the sensitivity of RyR channels to Ruthenium Red (see e.g. Smith et al. 1988) may be explained by differences in the purity (from 10 to 50 %) of Ruthenium Red from different sources (P. R. Junankar, unpublished observations). The reason for the difference in sensitivity to Ruthenium Red between RyR channels in vesicles and in bilayers is not clear, but has been observed with other agents (e.g. Lu et al. 1994; Mack et al. 1994; El-Hayek et al. 1995) and suggests that the sensitivity to drugs can be altered by incorporation of channels into bilayers.

Statistics

Average data are given as means ± 1 s.e.m. The significance of the difference between the logarithms of paired variables was tested using Student's t test for paired data. Some data were tested using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Differences were considered to be significant when P≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Ivermectin reversibly activates RyRs

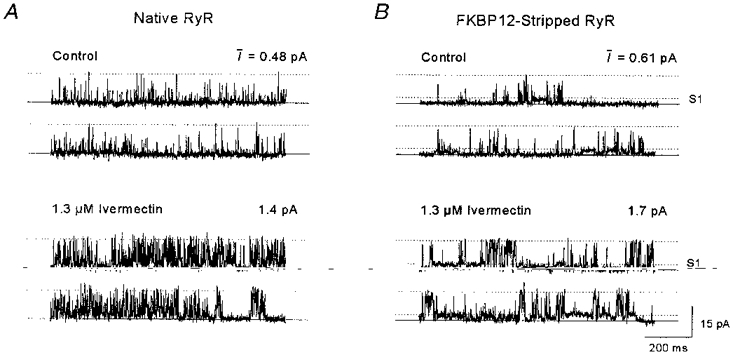

Ivermectin increased the activity of native and FKBP12-stripped RyR channels, without affecting single channel conductance. Brief discrete events, apparent in Fig. 1A, dominated native RyR activity when channels were inhibited by 1 mM cis Ca2+.

Figure 1. Activation of RyRs by ivermectin.

A, continuous channel activity of a single RyR incorporated from native TC vesicles. Upper traces, control recording. Lower traces, recording after addition of 1.3 μm ivermectin. B, continuous activity from an FKBP12-stripped RyR, incorporated from FKBP12-stripped TC vesicles. Upper traces, control activity. Lower traces, activity after addition of 1.3 μm ivermectin. Bilayer potential was +40 mV and solutions contained 250/50 mM CsCl and 1/1 mM Ca2+ (cis/trans). In A and B the continuous lines show the zero current level, maintained when the channel is closed. The upper dotted line shows the maximal single channel conductance, and the lower dotted line in B shows the lowest subconductance level, S1. The mean current, I (in pA), was calculated from at least 60 s of activity including that in A and B.

When 1.3 μm ivermectin was added to the cis chamber, the frequency of channel openings increased: open events became longer and the mean current (I) increased (Fig. 1A). The mean current through native RyRs increased in eleven out of thirteen bilayers with 0.66-4.0 μm ivermectin and increased reversibly with 40 μm ivermectin in four out of four bilayers containing control-incubated channels. Records from bilayers with only one active single channel were analysed further and the data are summarized in Table 2.

With 0.66-4.0 μm ivermectin, open probability (Po) increased in six out of eight native RyR channels, mean open time (To) became longer in all eight channels and the frequency of openings (Fo) increased in seven channels. Native channel activity in one of one experiment fell to control levels when ivermectin was perfused out of the cis chamber. Po, To and Fo increased in each of the four control-incubated channels exposed to 40 μm ivermectin. The ratio of the value of each parameter in ivermectin relative to control was calculated for each of the four channels and expressed as percentage, e.g. (Po,ivermectin/Po,control) × 100 %. The average changes were: 2300 ± 720 % for Po, 242 ± 41 % for To and 1065 ± 342 % for Fo. All parameters in each of the four control-incubated channels fell towards control levels after ivermectin was washed out.

Ivermectin also activated FKBP12-stripped channels (Table 2). Stripped channel activity (Fig. 1B) consisted of long openings to a submaximal level (S1) at ∼25 % maximum current, with brief openings to higher conductance levels (described previously, Ahern et al. 1997a). The frequency and duration of openings to S1 and to the maximum conductance level increased after addition of 1.3 μm ivermectin to the channel shown in Fig. 1B, with an accompanying increase in I. Po, To and Fo increased in one of four single FKBP12-stripped channels with 4 μm ivermectin. All of the parameters increased when the same four channels were exposed to 20 or 24 μmcis ivermectin, and the parameters also increased in six of seven FKBP12-stripped channels with 34-40 μm ivermectin (Table 2).

When ivermectin (34-40 μm) was perfused out of the cis chamber, FKBP12-stripped channel activity returned slowly towards control levels in six out of the seven channels. On average, Po recovered significantly from the exposure to the antihelminthic (Table 2). Ruthenium Red (10 or 80 μm) was added to the cis chamber in eleven experiments in which ivermectin had activated channels, and channel activity was abolished in all cases.

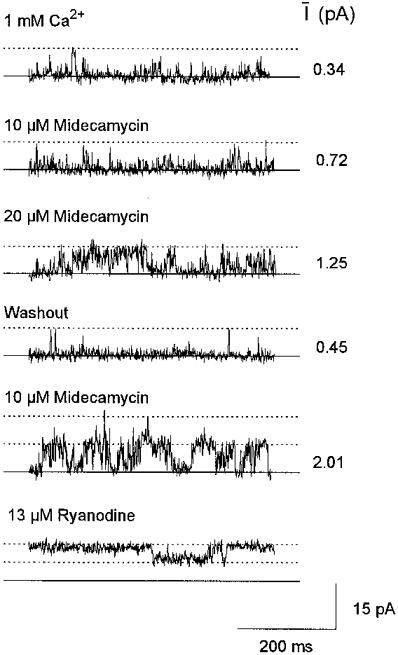

Action of the antibiotic midecamycin on RyR channels

Midecamycin (10-20 μm) reversibly activated native RyRs in three of four bilayers. In one experiment (Fig. 2), I increased with 10 μmcis midecamycin and increased further with a second addition of 10 μm midecamycin.

Figure 2. Reversible activation of native RyR channels by midecamycin.

Channel activity obtained from one bilayer containing at least two RyR channels. Two sequential additions of 10 μm midecamycin were followed by cis chamber perfusion and then 10 μm midecamycin was added once again, followed by 13 μm ryanodine. One channel was active in the bilayer in the top four records; two channels were active in the final two records. Channel activity was recorded at +40 mV with 1 mM cis Ca2+. The maximum open level for a single channel is indicated by the first dotted line in each record. The summed conductance for the two channels is indicated by the upper dotted line in the last two records. The mean current (I) recorded from > 80 s of continuous activity under each condition is shown beside each record (in pA).

I then fell with midecamycin washout. Two channels became active when the bilayer was again exposed to 10 μm midecamycin. Adding 13 μmcis ryanodine then induced long openings in both channels to ∼50 % maximum conductance (Fig. 2). In the other experiments, 10 μm midecamycin (n= 1) increased Po from 0.029 to 0.051 (To from 0.64 to 0.71 ms, and Fo from 44 to 72 s−1), while 16 μm midecamycin (n= 1) increased Po from 0.05 to 0.17 (To from 0.89 to 1.19 ms and Fo from 57 to 142 s−1).

Midecamycin (cis, 20-30 μm) increased I in control-incubated channels (8 of 12 bilayers) and in FKBP12-stripped channels (8 of 14 bilayers). Of eight single control-incubated channels, Po and Fo increased in six and To increased in five channels. For these eight channels, the averages of the percentage changes after exposure to midecamycin were: 323 ± 150 % for Po, 117 ± 16 % for To and 345 ± 80 % for Fo. Of the seven single FKBP12-stripped channels, Po and Fo increased in four and To increased in six channels with midecamycin, with the averages of the percentage change seen upon exposure to midecamycin being: 292 ± 159 % for Po, 125 ± 20 % for To and 185 ± 63 % for Fo.

Perfusing midecamycin out of the cis chamber was followed by a reduction in I in six of six bilayers with control-incubated channels, and seven of seven bilayers with FKBP12-stripped RyRs. Channels activated by midecamycin, like those activated by ivermectin, failed to show a preferential increase in activity to submaximal conductance levels. The results suggest that midecamycin altered activity in some native, control-incubated and FKBP12-stripped channels in much the same way as ivermectin. However, the changes with midecamycin were smaller than those with ivermectin and required higher concentrations of the drug.

The effects of ivermectin and midecamycin were not due to the addition of the vehicle. Ethanol (0.3 % v/v) alone has no significant effect on the single channel kinetics of skeletal or cardiac RyRs (Ahern et al. 1994; Eager et al. 1997). In the present experiments, 2 %cis ethanol failed to alter single channel characteristics in three control-incubated and five FKBP12-stripped RyRs within 2 min of addition (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ethanol at 2% does not alter single channel characteristics of control-incubated or FKBP12-stripped RyRs

| RyR | n | Po (ms) | To | Fo (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control incubated (10−7 M Ca2+) | ||||

| Control | 3 | 0.100 ± 0.960 | 11.2 ± 10.4 | 6 ± 2 |

| Ethanol | 3 | 0.088 ± 0.086 | 4.6 ± 3.9 | 8 ± 6 |

| FKBP12 stripped (10−7 M Ca2+) | ||||

| Control | 5 | 0.297 ± 0.159 | 10.0 ± 5.0 | 25 ± 9 |

| Ethanol | 5 | 0.301 ± 0.151 | 11.0 ± 5.3 | 23 ± 8 |

Channel activity was measured over ~60 s periods before and after addition of ethanol. The data are given as means ± S.E.M.

In addition, channel activity did not change when ethanol was washed out of the cis chamber in two of two control-incubated channels or in four of four FKBP12-stripped channels.

Ivermectin and midecamycin do not remove FKBP12 from TC vesicles

Since FKBP12-stripped channels and RyRs containing FKBP12 (native or control incubated) responded in a similar way to applications of ivermectin (or midecamycin), it was likely that removal of FKBP12 was not necessary for channel activation. However, it remained possible that the drugs could induce FKBP12 dissociation from the RyR. TC vesicles were incubated with ivermectin (40 μm) and midecamycin (40 μm), as well as rapamycin (0.5-40 μm), for 15 min at 37°C. After the drugs were removed from the vesicles by centrifugation, the resuspended membranes were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (Fig. 3) before immunostaining with antibodies to FKBP12.

Figure 3. Ivermectin and midecamycin do not remove FKBP12 from TC vesicles, in contrast to the effect of rapamycin.

Western blot of TC vesicles which had been pre-incubated with rapamycin (0.5-40 μm), ivermectin (Iv, 40 μm) or midecamycin (Mi, 40 μm). The blot was immunostained with an affinity-purified antiFKBP12-peptide antibody. The positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left. The immunostaining at ≈12 kDa in vesicles treated with ivermectin or midecamycin was not decreased compared with the control vesicles. No detectable FKBP12 was observed in SR vesicles preincubated with 10-40 μm rapamycin.

In contrast to rapamycin, neither midecamycin nor ivermectin caused FKBP12 dissociation from the TC vesicles. Furthermore, unlike bastadin and FK506 (Mack et al. 1994), ivermectin did not act synergistically with rapamycin in promoting the removal of FKBP12 from RyRs (P. R. Junankar, unpublished observations).

Ivermectin reduces the rate of Ca2+ uptake by TC vesicles

The experiments in this and the following sections examine the possibility that ivermectin and midecamycin alter Ca2+ handling by the SR. The rate of removal of Ca2+ from the extravesicular solution by TC or LSR was examined in the absence or presence of Ruthenium Red (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. The effect of ivermectin on Ca2+ uptake by SR vesicles.

A and C, records of changes in OD at 710 nm in response to changes in extravesicular [Ca2+], using antipyrylazo III (200 μm) as a Ca2+ indicator. A, Ca2+ uptake by TC vesicles after addition of 50 μm Ca2+ to the cuvette. Slope a is the initial rate of Ca2+ uptake before adding 5 μm Ruthenium Red (rr) (indicated by the discontinuity in the decline in OD). Slope b is the initial rate of Ca2+ uptake after adding Ruthenium Red. B, the initial rate of Ca2+ uptake by TC as a function of ivermectin concentration, expressed as a percentage of the control rate, before (○) and after (•) adding Ruthenium Red. Data points are means ±s.e.m. (n= 3); vesicles were from two separate SR preparations. C, Ca2+ uptake by LSR vesicles after adding 50 μm Ca2+ to the cuvette. Slope a is the initial rate of Ca2+ uptake. D, the initial rate of Ca2+ uptake by LSR as a function of ivermectin concentration, expressed as a percentage of the control rate. Data points are means ±s.e.m. (n= 4); vesicles were from three SR preparations. The control records in A and C were obtained after addition of ethanol (0.5 % v/v). The ivermectin records were obtained after addition of 10 μm ivermectin. The vertical calibration bar shows [Ca2+], which was routinely determined from the OD response to step increases in [Ca2+] and was linear over the range of [Ca2+] values shown in the figure. In this case an increase in [Ca2+] of 42 μm caused an increase of 0.1 OD units.

The rate of Ca2+ removal by TC vesicles (slope a, Fig. 4A) depends on Ca2+ uptake by the SR Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase minus Ca2+ release through RyR channels and other Ca2+ leakage pathways. Ca2+ efflux through RyR channels was blocked when Ruthenium Red (5 μm) was added and the rate of Ca2+ removal increased (slope b, Fig. 4A). We had predicted that, if Ca2+ release alone was enhanced by ivermectin, slope a only would be reduced after ivermectin addition to TC vesicles. Surprisingly, both slope a and slope b were less steep than control with 10 μm ivermectin. Ivermectin caused a concentration-dependent decrease in the rate of Ca2+ uptake in both the absence and presence of Ruthenium Red (5 μm), with IC50 values (from the best fit of a simple Michaelis-Menton equation to the data) of 3.54 ± 1.37 and 2.01 ± 0.74 μm, respectively (Fig. 4B).

If the only effect of ivermectin was to enhance Ca2+ release through RyRs, then slope a in LSR vesicles should not be altered by ivermectin because the vesicles contain little RyR protein (Kourie et al. 1996). The paucity of RyR channels was confirmed by a lack of effect of Ruthenium Red on Ca2+ uptake rates by LSR (not shown). The rate of Ca2+ uptake (slope a in Fig. 4C) was reduced with 10 μm ivermectin, with an average reduction to ∼40 % of control (Fig. 4D). The IC50 for the action of ivermectin on Ca2+ uptake in LSR was 3.42 ± 0.67 μm, very close to the value obtained for the Ruthenium Red-inhibited TC vesicles. Since ivermectin slowed Ca2+ removal from the extravesicular solution in two situations in which RyR activity was minimal, the results suggest that ivermectin reduced the rate of Ca2+ uptake by the Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase.

The control experiments shown in Fig. 4 were performed in the presence of ethanol (the same volume as added with midecamycin; the maximum volume of ethanol added was 0.5 % v/v). Ethanol alone reduced Ca2+ uptake by TC vesicles in each of three preparations, to 77 ± 7 % of control before adding Ruthenium Red, and to 80 ± 3 % of control after Ruthenium Red.

Experiments were also performed with ivermectin dissolved in DMSO (which was the vehicle used in subsequent skinned fibre experiments, below). Rates with DMSO alone were 115 ± 12 % of control (n= 5) before Ruthenium Red and 107 ± 8 % of control after Ruthenium Red was added. Ivermectin (10 μm) in DMSO reduced the rate of Ca2+ uptake both before and after adding Ruthenium Red in three out of three preparations, to 66 ± 8 and 54 ± 5 %, respectively, of the controls in DMSO. Thus ivermectin substantially reduced Ca2+ uptake whether ethanol or DMSO was used as the vehicle.

In contrast to ivermectin, midecamycin (10-40 μm in ethanol) had minimal effects on Ca2+ uptake by TC. In one experiment, the uptake rates in 10 and 40 μm midecamycin were 103 and 120 %, respectively, of control before Ruthenium Red addition, and 104 and 107 % of control, respectively, with Ruthenium Red. In the presence of DMSO, midecamycin (10 μm) reduced Ca2+ uptake before and after adding Ruthenium Red in three out of three experiments, with averages of 76 ± 11 and 90 ± 3 %, respectively, of the control rates with DMSO alone. Although midecamycin reduced Ca2+ uptake in this series of experiments (with DMSO as the vehicle), the reduction in Ca2+ uptake was substantially less than that seen with ivermectin.

The Ca2+ uptake experiments (Fig. 4) provide no information about the effects of ivermectin on Ca2+ release through the RyR because the dominant contribution of reduced Ca2+ pump activity masked any reduction in Ca2+ uptake due to RyR activation. This was not surprising since the Ca2+- Mg2+-ATPase is the most abundant protein in all fractions of SR (Saito et al. 1984). The specific effect of ivermectin on Ca2+ release was examined in the following experiments.

Ivermectin increases Ca2+ release from TC vesicles in the presence of thapsigargin

Native TC vesicles were partially loaded with Ca2+ by adding four aliquots of Ca2+ to the cuvette, each of which initially increased the extravesicular [Ca2+] by 7.5 μm (Methods, Fig. 5).

Neither ivermectin (10 μm) nor ethanol alone (0.5 % v/v) altered the resting extravesicular [Ca2+] when added to the cuvette (Fig. 5A, n= 5). The increase in extravesicular [Ca2+] when A23187 was added indicated that the vesicles were loaded with Ca2+. Either antipyrylazo III was not sensitive enough to give a measureable response to the Ca2+ released by ivermectin and/or any increase in Ca2+ release was compensated for by Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase activity which, although reduced by ivermectin (Fig. 4 above), may have remained sufficient to prevent an increase in extravesicular Ca2+. Thapsigargin (200 nM) was added in subsequent experiments to block the Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase (Sagara & Inesi, 1991).

Extravesicular [Ca2+] increased at a rate of 49.8 ± 1.4 nmol (mg SR protein)−1 min−1 (n= 7) after thapsigargin was added, and ceased after addition of 10 μm Ruthenium Red (Fig. 5B), indicating that Ca2+ was released through RyR channels. Adding 10 μm ivermectin to thapsigargin-treated vesicles enhanced Ca2+ release to 81.4 ± 3.8 nmol mg−1 min−1 (n= 4), also via RyR channels since all release ceased with Ruthenium Red (Fig. 5C). Ca2+ release from thapsigargin-treated vesicles remained at 44.4 ± 3.8 nmol mg−1 min−1 (n= 3) when ethanol (0.5 % v/v) was added alone (Fig. 5B).

Midecamycin (40 μm) did not affect extravesicular [Ca2+] in experiments where total MgCl2 concentration was 9, 4 or 2 mM. Ca2+ release in this series of experiments was 77 ± 8 nmol mg−1 min−1 (n= 7) after adding thapsigargin and this was unchanged with 0.25 % (v/v) ethanol (78 ± 10 nmol mg−1 min−1, n= 4) or with 40 μm midecamycin (74 ± 6 nmol mg−1 min−1, n= 6).

Ivermectin potentiates caffeine-induced Ca2+ release from SR vesicles

Caffeine was used as a means of amplifying Ca2+ release in order to examine the effects of ivermectin in the vesicle system. The continued Ca2+ release from TC vesicles after addition of thapsigargin and ivermectin meant that insufficient Ca2+ remained in the vesicles for examination of caffeine-induced release. Therefore Ca2+ release was reduced (Fig. 6A and B) by adding a further 5 mM MgCl2 to give a total free [Mg2+] of ∼0.9 mM, which substantially reduces Ca2+ release through the RyR (Meissner, 1994; Laver et al. 1997).

The reduced rate of increase in extravesicular [Ca2+] with Mg2+ provides further evidence that Ca2+ release from the vesicles was through the RyR. Ivermectin (10 μm), added after 5 mM MgCl2, increased Ca2+ release (Fig. 6B) thus overcoming the block of RyRs by ∼0.9 mM free Mg2+. Ethanol alone had no effect on Ca2+ release (Fig. 6A). Caffeine-activated Ca2+ release was greater with ivermectin (Fig. 6B) than in control (Fig. 6A), and less Ca2+ remained in the vesicles to be released by A23187 (final records in Fig. 6A and B).

Caffeine-activated Ca2+ release in the presence of 10 μm ivermectin was greater than expected for a simple additive effect of the two drugs. Initial rates of Ca2+ release induced by caffeine (0.6-5 mM, measured from records similar to those in Fig. 6A and B) were corrected for ‘background’ rates in ethanol or ivermectin. Ivermectin potentiated the caffeine-induced release of Ca2+ from TC vesicles in which the RyR was inhibited by Mg2+ (Fig. 6C), suggesting that ivermectin increased the sensitivity of the RyR to caffeine (see Discussion below).

No enhancement of caffeine- (0.63-6.3 mM) activated Ca2+ release from thapsigargin-treated TC vesicles was observed with midecamycin (n= 7, Table 4).

Table 4.

Individual measurements of initial rate of caffeine-activated Ca2+ release with paired experiments using the ethanol vehicle alone (0.4% v/v) and then 40 μM midecamycin in ethanol

| Caffeine concentration (mM) | Ethanol control (nmol mg−1 min−1) | Midecamycin (nmol mg−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.63 | 137 | 92 |

| 0.63 | 98 | 103 |

| 0.63 | 98 | 78 |

| 1.25 | 137 | 180 |

| 2.5 | 650 | 740 |

| 2.5 | 305* | 207* |

| 6.3 | 560* | 431* |

All experiments, except those marked with an asterisk, were performed in the presence of 200 nM thapsigargin. The rate given is the initial rate in ethanol or midecamycin minus the rate of release before addition of ethanol or midecamycin. The experiments were performed with vesicle preparations giving a stronger response to caffeine than those used for the experiment in Fig. 6.

On average, caffeine-activated Ca2+ release with 0.63 mM caffeine was 109 ± 11 nmol mg−1 min−1 with ethanol (0.4 % v/v) alone and 91 ± 7 nmol mg−1 min−1 with ethanol plus 40 μm midecamycin. Experiments using FKBP12-stripped vesicles were attempted, but were not successful because the vesicles were ‘leaky’ and did not accumulate sufficient Ca2+ to allow us to examine the ability of the drugs to release Ca2+.

Action of ivermectin on intact and skinned rat EDL fibres

The results described thus far suggest that ivermectin might affect Ca2+ stores in intact skeletal muscle. To test this possibility, 40 μm ivermectin was added to the solution bathing small bundles of rat EDL fibres in four experiments. There was no change in twitch or tetanic tension for up to 20 min after adding the drug (preparation run-down prevented an examination of longer exposures). Ivermectin may not have fully partitioned into the cytoplasm and SR within the 20 min of the experiment. Rapamycin and FK506 (at 10 μm) enhance RyR activity (Ahern et al. 1994) to a far greater extent than ivermectin (see above) and enhance caffeine-induced contraction in intact rat soleus fibres in Ca2+-free solutions (Brillantes et al. 1994). Although the RyR is more sensitive to these agents, they did not increase twitch tension in rat EDL fibres in Ca2+-containing Krebs solutions (J. Mould, unpublished observations).

Ivermectin did alter Ca2+ loading and caffeine-activated Ca2+ release from many skinned rat EDL muscle fibres. Since ethanol enhanced Ca2+ release from skinned fibres (not shown), stock ivermectin solutions for these experiments were prepared in DMSO, a solvent vehicle which did not alter load times or tension during release (n= 8). Ivermectin (40 μm) did not alter the maximum Ca2+-activated force generated by the contractile proteins (n= 5; not shown). In Ca2+ loading experiments, the amount of Ca2+ loaded (i.e. the peak tension in response to the 30 mM caffeine, 0.05 mM Mg2+ maximum release solution) increased approximately linearly with time and reached a maximum with a loading time of 2.5 min. The time required for ∼50 % loading of the SR was ∼1.0 min in the presence of DMSO (0.4 % v/v) alone. When 40 μm ivermectin was added before, and during, the same 50 % loading period as that used in the bracketing DMSO controls (see Methods), peak tension induced by the maximum release solution fell in four of six fibres (see e.g. fibre in Fig. 7A).

Figure 7. Ivermectin (40 μm) reduces Ca2+ uptake by SR in skinned EDL muscle fibres and increases caffeine-activated Ca2+ release.

The records show tension as a function of time. A, records obtained from one fibre during maximal Ca2+ release (30 mM caffeine, 0.05 mM Mg2+), after submaximal Ca2+ loading (see text and Methods). The bracketing control records were obtained with the solvent vehicle DMSO (0.4 % v/v) in the low relaxing solution used immediately before loading, and in the load solution. Ivermectin (40 μm: 8 μl of 10 mM ivermectin, i.e. 0.4 % v/v) was added to identical solutions in order to obtain the ivermectin record. B, records obtained from one fibre during exposure to the submaximal Ca2+ release solution (15 mM caffeine, 0.25 mM Mg2+). The bracketing control records were obtained with the solvent vehicle DMSO (0.4 % v/v) in the low relaxing solution used immediately before release, and in the release solution. The record labelled ivermectin was obtained with 40 μm ivermectin added to identical solutions.

On average, peak tension in ivermectin was 92 ± 3 % (n= 6) of the DMSO control. Since the size of the tension response to 30 mM caffeine (0.05 mM Mg2+) reflected the amount of Ca2+ loaded (i.e. tension increased with load time until maximum loading was achieved), the fall in tension suggested that ivermectin reduced Ca2+ uptake by the SR in the skinned fibres.

Tension during caffeine-activated Ca2+ release was enhanced in some fibres that were exposed to 40 μm ivermectin before and during release (Methods, Fig. 7B). In this experiment, maximal loading was achieved by 2.5 min exposure to the load solution. After equilibration in low relaxing solution, fibres were exposed to the 15 mM caffeine release solution to produce a contraction with an amplitude of 40-80 % of that recorded with maximum release. This solution was submaximal because of the lower caffeine concentration (15 mM) and the higher Mg2+ concentration (0.25 mM). Exposure to ivermectin increased tension in five of eight fibres (Fig. 7B), with the average response in ivermectin being 109 ± 7 % (n= 8) of the response with DMSO alone.

DISCUSSION

Ivermectin and midecamycin reversibly increased the single channel activity of native and FKBP12-stripped RyRs in lipid bilayers. Ivermectin and midecamycin increased the frequency and duration of RyR channel openings and therefore increased the open probability and the mean current. RyR activation was not associated with an increase in the number of channel openings to submaximal conductance levels in native or control-incubated channels. Indeed an increase in channel openings to the maximum conductance was apparent when ivermectin or midecamycin activated single FKBP12-stripped channels and when rapamycin activated FKBP12-depleted RyRs (Ahern et al. 1997b). The increased opening to the maximum conductance was in contrast to the increase in channel openings to submaximal conductance levels seen when FK506 or rapamycin activate native RyR channels (Ahern et al. 1994; Brillantes et al. 1994). Since neither ivermectin nor midecamycin removed FKBP12 from TC vesicles, and since both drugs activate FKBP12-stripped RyR channels, the macrocyclic lactones must activate the RyRs through a mechanism that is independent of the FKBP12 molecules tightly bound to the RyR.

It is possible that the macrocyclic lactone quinolidomycin A1, which stimulated 45Ca2+ release from loaded SR vesicles via a mechanism that can only partly be blocked by RyR inhibitors (Ohkura et al. 1996), acts at the same FKBP12-independent site as rapamycin, ivermectin and midecamycin. However, there are considerable differences between the structures of these macrocyclic lactones. Rapamycin has a twenty-nine-membered ring structure (Harding et al. 1989), ivermectin and midecamycin both possess sixteen-membered rings, while quinolidomycin A1 has a sixty-membered ring structure. In addition, the number and size of side groups varies widely between the compounds. Although there is no direct evidence that each of the macrocyclic lactones binds to the RyR at the same site, the following observations suggest that they may act at one site: (a) each drug has a lactone group as a part of its macrocyclic structure, (b) each drug produces very similar changes in single channel activity, and (c) the action of the drugs is independent of FKBP12.

Other macrocyclic compounds also activate the RyR. Bastadin 5, a heterocyclic compound of similar size to rapamycin but lacking a lactone group, increases single channel open time but does not alter the open probability (Mack et al. 1994). Rapamycin and ivermectin, on the other hand, increase Po by increasing both the frequency and duration of openings. Channels activated by midecamycin also showed increases in open probability, event duration and frequency as well as mean current. It has also been proposed (Mack et al. 1994) that bastadin 5 acts synergistically with FK506 to help remove FKBP12 from RyR, a property not shared by ivermectin (P. R. Junankar, unpublished results). Therefore it is likely that bastadin 5 activates RyRs by a mechanism that is different from that of rapamycin, ivermectin and midecamycin.

Ivermectin increases Ca2+ release from SR vesicles

The effects on Ca2+ handling by SR vesicles and Ca2+ release from skinned fibres were consistent with the ability of ivermectin to increase RyR activity. Ivermectin-induced Ca2+ release from TC vesicles was seen when the Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase was blocked by thapsigargin. In addition caffeine-activated Ca2+ release from TC vesicles and from skinned fibres was enhanced by this antihelminthic drug. It is possible that the enhanced caffeine-activated Ca2+ release from TC vesicles was due to the higher extravesicular Ca2+ concentration after addition of ivermectin (∼6 μm compared with ∼5 μm, Fig. 6A and B) before caffeine was added. However, the effect of Ca2+ on RyR activation by caffeine (in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+ and 1 mM AMP-PCP, a non-hydrolysable form of ATP), assessed from [3H]ryanodine binding, is maximal at less than 1 μm Ca2+ and independent of [Ca2+] between 1 and 100 μm Ca2+ (Pessah et al. 1987).

An unexpected finding was that ivermectin reduced Ca2+ uptake into the SR by the Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase. Bastadin 5 (10 μm) also decreases Ca2+ uptake by junctional SR vesicles (Pessah et al. 1997) but contrary to our results with ivermectin, the uptake was double the control when the RyR was inhibited by Ruthenium Red or ryanodine. This indicates that bastadin activated the Ca2+ pump whereas our results in the presence of Ruthenium Red, and with LSR, show that ivermectin inhibited the Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase.

That midecamycin was less effective than ivermectin in reducing Ca2+ uptake by the SR, and did not release Ca2+ from SR vesicles or skinned fibres, was not surprising since the macrocyclic antibiotic was less effective in increasing single RyR channel activity. The minimum concentration of midecamycin required to influence the open times of single channels was 10 μm, in contrast to the minimum concentration of ivermectin which was 1.3 μm. The reason for the less effective action of midecamycin on single channels is not clear. It is possible that the binding of midecamycin is much weaker than ivermectin and that concentrations in excess of 40 μm would be required to observe gross channel activation and activation of Ca2+ release in vesicles and skinned fibres.

Effects of ethanol

Ethanol (0.5-2 % v/v) enhanced Ca2+ release from skinned fibres, slowed Ca2+ uptake into SR vesicles, and did not alter Ca2+ release from TC vesicles or single RyR channel activity. Oba et al. (1997) also found that ethanol (up to 1 % v/v) did not alter single frog RyR channel characteristics when added alone, but enhanced the activity of caffeine-activated channels and also enhanced caffeine-activated Ca2+ release from SR vesicles. These conflicting results are typical of variations often noted when different experimental preparations are used. For example, low pH enhances Ca2+ transients in intact fibres (Westerblad & Allen, 1993), but strongly inhibits RyR channel activity (Ma et al. 1988). Another example is dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) II-III loop peptides which activate [3H]ryanodine binding to SR, and Ca2+ release from SR vesicles at micromolar concentrations, yet activate single RyR channels at nanomolar concentrations (Lu et al. 1994; El-Hayek et al. 1995). A final example is bastadin, which enhances Ca2+ release from the SR, but has no effect on single channel open probability (Mack et al. 1994). These results are difficult to reconcile, but suggest, not unexpectedly, that the regulation of RyR channels is very dependent on other factors present in the system. For example, signalling systems which may be disrupted with vesicle isolation, or geometrical features that might be lost with vesicle incorporation into bilayers.

Implications of the action of ivermectin on Ca2+ handling by skeletal SR

The biological action of ivermectin on invertebrates has been attributed to its action on the neuromuscular system. Inhibitory glutamate and GABAA-gated Cl− channels are activated at picomolar to nanomolar concentrations of ivermectin (Rohrer & Arena, 1995; Duce et al. 1995). These concentrations would not be sufficient to deplete Ca2+ stores unless the sensitivity of invertebrate RyRs is higher than mammalian RyRs. Toxic effects of ivermectin overdoses have been reported in mice, rats, dogs, cats and sheep, and these effects include mydriasis, muscle tremors, ataxia and weakness (Campbell, 1989; Lovell, 1990). In one case study, hyperthermia was reported in a dog (Hopkins et al. 1990). Malignant hyperthermia in pigs and humans is a result of a mutation in the RyR which leads to a higher than normal Ca2+ efflux from the SR (Ohta et al. 1989). Therefore this and some of the other side effects of ivermectin might result from its action on the skeletal RyR and SR Ca2+ pump which would deplete Ca2+ stores and increase myoplasmic Ca2+.

Alterations in Ca2+ uptake and release may explain both the positive and the negative side effects of other macrolide drugs. The macrolide immununosuppressant FK506 is associated with well-known nephro- and neurotoxicities, some of which do not depend on the ability of the FK506-FKBP12 complex inhibiting calcineurin. More recently, FK506 and non-immunosuppressive macrolides have been shown to promote neurite outgrowth in cell cultures and regeneration in nerve crush models, by calcineurin-independent mechanisms (Gold et al. 1997; Steiner et al. 1997a, b). In addition, macrolide antibiotics are protective against glutamate excitotoxicity; the protection is structure dependent with larger ringed macrolides being more effective (Manev et al. 1993). The molecular basis for these neuronal effects is unknown, but it is possible that they are partly mediated by altered Ca2+ transport across the endoplasmic reticulum, similar to those reported here in the SR.

In conclusion, our findings confirm the hypothesis that drugs containing a macrocyclic lactone ring structure can activate the RyR channel by binding to a site on the RyR tetramer that is independent of FKBP12. Ivermectin also potentiated caffeine-induced release of Ca2+ from isolated TC vesicles and from SR in skinned muscle fibres, providing further evidence for an activating effect on the RyR Ca2+ release channel. An additional action of ivermectin was its inhibition of the SR Ca2+ pump in SR vesicles, a result that was consistent with reduced uptake of Ca2+ in skinned fibres. These observations may explain some of the side effects of ivermectin poisoning and macrolide drugs in mammals.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Joan Stivala for expert assistance with isolation and characterisation of SR vesicles and with FKBP12-stripping procedures. We are also grateful to Michael Smith, Bernie Keys, Glen Whalley and Lorline Hardy for their assistance.

References

- Ahern GP, Junankar PR, Dulhunty AF. Single channel activity of the ryanodine receptor calcium release channel is modulated by FK506. FEBS Letters. 1994;352:369–374. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01001-3. 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern GP, Junankar PR, Dulhunty AF. Subconductance states in single-channel activity of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptors after removal of FKBP12. Biophysical Journal. 1997a;72:146–162. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78654-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern GP, Junankar PR, Dulhunty AF. Ryanodine receptors from rabbit skeletal muscle are reversibly activated by rapamycin. Neuroscience Letters. 1997b;225:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00193-6. 10.1016/S0304-3940(97)00193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arena JP, Liu KK, Paress PS, Frazier EG, Cully DF, Mrozik H, Schaeffer JM. The mechanism of action of avermectins in Caenorhabditis elegans: correlation between activation of glutamate-sensitive chloride current, membrane binding, and biological activity. Journal of Parasitology. 1995;81:286–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomquist JR. Toxicology, mode of action and target site-mediated resistance to insecticides acting on chloride channels. Comparitive Biochemistry and Physiology C. 1993;106:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(93)90138-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brillantes A-M B, Ondrias K, Scott A, Kobrinsky E, Ondriasova E, Moschella MC, Jayaraman T, Landers M, Ehrlich BE, Marks AR. Stabilization of calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) function by FK506-binding protein. Cell. 1994;77:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee DJA, Holden-Dye L, Walker RJ. Actions of the antihelminthic invermectin on the pharyngeal muscle of the parasitic nematode, Ascaris suum. Journal of Parasitology. 1997;115:553–561. doi: 10.1017/s0031182097001601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WC. Ivermectin and Abamectin. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Chu A, Dixon MC, Saito A, Seiler S, Fleischer S. Isolation of sarcoplasmic reticulum fractions referable to longitudinal tubules and junctional terminal cisternae from rabbit skeletal muscle. Methods in Enzymology. 1989;157:36–50. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent JA, Davis MW, Avery L. avr-15 encodes a chloride channel subunit that mediates inhibitory glutamatergic neurotransmission and ivermectin sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO Journal. 1997;16:5867–5879. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5867. 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duce IR, Bhandal NS, Scott RH, Norris TM. Effects of Ivermectin on gamma-aminobutyric acid- and glutamate-gated chloride conductance in arthropod skeletal muscle. In: Marshall Clark J, editor. Molecular Action of Insecticides on Ion Channels. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1995. pp. 251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Dulhunty AF. Activation and inactivation of excitation-contraction coupling in rat soleus muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;439:605–626. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulhunty AF. The voltage-activation of contraction in skeletal muscle. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 1992;57:181–223. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(92)90024-z. 10.1016/0079-6107(92)90024-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eager KR, Roden LD, Dulhunty AF. Actions of sulfhydryl reagents on single ryanodine receptor Ca2+-release channels from sheep myocardium. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:1908–1919. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.6.C1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hayek R, Antoniu B, Wang J, Hamilton SL, Ikemoto N. Identification of calcium release-triggering and blocking regions of the II-III loop of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:22116–22118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22116. 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary TG, Sims SM, Thomas EM, Vanover L, Davis JP, Winterrowd CA, Klein RD, Ho NFH, Thompson DP. Haemonchus contortus: ivermectin-induced paralysis of the pharynx. Experimental Parasitology. 1998;77:88–96. doi: 10.1006/expr.1993.1064. 10.1006/expr.1993.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold BG, Zeleny-Pooley M, Wang MS, Chaturvedi P, Armistead DM. A nonimmunosuppressant FKBP-12 ligand increases nerve regeneration. Experimental Neurology. 1997;147:269–278. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6630. 10.1006/exnr.1997.6630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton-Miller JMT. In-vitro activities of 14-, 15- and 16-membered macrolides against Gram-positive cocci. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1992;29:141–147. doi: 10.1093/jac/29.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding MW, Galat A, Uehling DE, Schreiber SL. A receptor for the immunosuppressant FK506 is a cis-trans peptidyl-prolylsomerase. Nature. 1989;341:758–761. doi: 10.1038/341758a0. 10.1038/341758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins KD, Marcella KL, Strecker AE. Ivermectin toxicosis in a dog. American Veterinary Medical Association Journal. 1990;197:93–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Casida JE. Avermectin B1a binds to high- and low-affinity sites with dual effects on the gamma-aminobutyric acid-gated chloride channel of cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1997;281:261–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman T, Brillantes A-M, Timerman AP, Fleischer S, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Marks AR. FK506 binding protein associated with the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:9474–9477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourie JI, Laver DR, Junankar PR, Gage PW, Dulhunty AF. Characteristics of two types of chloride channel in sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles of rabbit skeletal muscle. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:202–221. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79564-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb GD, Stephenson DG. Calcium release in skinned muscle fibres of the toad by transverse tubule depolarization or by direct stimulation. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;423:495–517. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laver DR, Baynes TM, Dulhunty AF. Magnesium inhibition of ryanodine receptor calcium channels: evidence for two independent mechanisms. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1997;156:213–229. doi: 10.1007/s002329900202. 10.1007/s002329900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laver DR, Roden LD, Ahern GP, Eager KR, Junankar PR, Dulhunty AF. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ inhibits the ryanodine receptor from cardiac muscle. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1995;147:7–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00235394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell RA. Ivermectin and piperazine toxicoses in dogs and cats. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice. 1990;20:453–468. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(90)50038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Xu L, Meissner G. Activation of the skeletal muscle calcium release channel by a cytoplasmic loop of the dihydropyridine receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:6511–6516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Fill M, Knudson CM, Campbell KP, Coronado R. Ryanodine receptor of skeletal muscle is a gap junction-type channel. Science. 1988;242:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.2459777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack MM, Molinski TF, Buck ED, Pessah IN. Novel modulators of skeletal muscle FKBP12/calcium channel complex from Ianthella basta. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:23236–23249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manev H, Favaron M, Candeo P, Fadda E, Lipartiti M, Milani D. Macrolide antibiotics protect neurons in culture against the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated toxicity of glutamate. Brain Research. 1993;624:331–335. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90098-8. 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks PW, Maxfield FR. Preparation of solutions with free Ca concentration in the nanomolar range using 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetracetic acid. Annals of Biochemistry. 1991;193:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90044-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayrleitner M, Timerman AP, Wiederrecht G, Fleischer S. The calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum is modulated by FK-506 binding protein: effect of FKBP-12 on single channel activity of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Cell Calcium. 1994;15:99–108. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(94)90048-5. 10.1016/0143-4160(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzei T, Mini E, Novelli A, Periti P. Chemistry and mode of action of macrolides. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1993;31:1–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_c.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G. Ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channels and their regulation by endogenous effectors. Annual Review of Physiology. 1994;56:485–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.002413. 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.002413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oba T, Koshita M, Yamaguchi M. Ethanol enhances caffeine-induced Ca2+-release channel activation in skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C622–627. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkura M, Miyashita Y, Kakubari M, Hayakawa Y, Seto H, Ohizumi Y. Characteristics of 45Ca2+ release induced by quinolidomicin A1, a 60-membered macrolide from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1996;1294:177–182. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(96)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T, Endo M, Nakano T, Morohoshi Y, Wanikawa K, Ohga A. Ca-induced Ca release in malignant hyperthermia-susceptible pig skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:C358–367. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.2.C358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessah IN, Molinski TF, Meloy TD, Wong P, Buck ED, Allen PD, Mohr FC, Mack MM. Bastadins relate ryanodine-sensitive and -insensitive Ca2+ efflux pathways in skeletal SR and BC3H1 cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C601–614. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessah IN, Stambuk RA, Casida JE. Ca2+-activated ryanodine binding: mechanisms of sensitivity and intensity modulation by Mg2+, caffeine, and adenine nucleotides. Molecular Pharmacology. 1987;31:232–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer SP, Arena JP. Ivermectin interactions with invertebrate ion channels. In: Marshall Clark J, editor. Molecular Action of Insecticides on Ion Channels. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1995. pp. 264–283. [Google Scholar]

- Sagara Y, Inesi G. Inhibition of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport ATPase by thapsigargin at subnanomolar concentrations. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:13503–13506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Seiler S, Chu A, Fleischer S. Preparation and morphology of sarcoplasmic reticulum terminal cisternae from rabbit skeletal muscle. Journal of Cell Biology. 1984;99:875–885. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.875. 10.1083/jcb.99.3.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JS, Imagawa T, Ma J, Fill M, Campbell KP, Coronado R. Purified ryanodine receptor from rabbit skeletal muscle is the calcium-release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum. Journal of General Physiology. 1988;92:1–26. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.1.1. 10.1085/jgp.92.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner JP, Connolly MA, Valentine HL, Hamilton GS, Dawson TM, Hester L, Snyder SH. Neurotrophic actions of nonimmunosuppressive analogues of immunosuppressive drugs FK506, rapamycin and cyclosporin A. Nature Medicine. 1997a;3:421–428. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-421. 10.1038/nm0497-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner JP, Hamilton GS, Ross DT, Valentine HL, Guo H, Connolly MA, Liang S, Ramsey C, Li JH, Huang W. Neurotrophic immunophilin ligands stimulate structural and functional recovery in neurodegenerative animal models. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997b;94:2019–2024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2019. 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timerman AP, Ogunbumni E, Freund E, Wiederrecht G, Marks AR, Fleischer S. The calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum is modulated by FK-506-binding protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:22992–22999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenknecht T, Grassucci R, Berkowitz J, Wiederrecht GJ, Xin H-B, Fleischer S. Cryoelectron microscopy resolves FK506-binding protein sites on the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:1709–1715. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79733-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerblad H, Allen DG. The influence of intracellular pH on contraction, relaxation and [Ca2+]i in intact single fibres from mouse muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;466:611–628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]