Abstract

The effects of the divalent cations Ca2+, Mg2+ and Ni2+ on unitary Na+ currents through receptor-regulated non-selective cation channels were studied in inside-out and cell-attached patches from rat adrenal zona glomerulosa cells.

External Ca2+ caused a concentration-dependent and voltage-independent inhibition of inward Na+ current, exhibiting an IC50 of 1.4 mm. The channel was also Ca2+ permeant and external Ca2+ shifted the reversal potential as expected for a channel exhibiting a constant Ca2+:Na+ permeability ratio near to 4.

External and internal 2 mm Mg2+ caused voltage-dependent inhibition of inward and outward Na+ current, respectively. Modelling Mg2+ as an impermeant fast open channel blocker indicated that external Mg2+ blocked the pore at a single site exhibiting a zero voltage Kd of 5.1 mm for Mg2+ and located 19% of the distance through the transmembrane electric field from the external surface. Internal Mg2+ blocked the pore at a second site exhibiting a Kd of 1.7 mm for Mg2+ and located 36% of the distance through the transmembrane electric field from the cytosolic surface.

External Ni2+ caused a voltage- and concentration-dependent slow blockade of inward Na+ current. Modelling Ni2+ as an impermeant slow open channel blocker indicated that Ni2+ blocked the pore at a single site exhibiting a Kd of 1.09 mm for Ni2+ and located 13.7% of the distance through the transmembrane electric field from the external surface.

External 2 mm Mg2+ increased the Kd for external Ni2+ binding to 1.27 mm, consistent with competition for a single binding site. Changing ionic strength did not substantially affect Ni2+ blockade indicating the absence of surface potential under physiological ionic conditions.

It is concluded that at least two divalent cation binding sites, separated by a high free energy barrier (the selectivity filter), are located in the pore and contribute to Ca2+ selectivity and permeability of the channel.

Non-selective cation channels are involved in a multiplicity of cellular functions including control of membrane excitability, synaptic transmission, sensory transduction and receptor-mediated signal transduction (Seimen, 1993). These channels share the common feature of non-selective permeation by monovalent cations but differ widely in divalent cation permeability, unitary conductance and regulation of gating behaviour. In a wide variety of cell types, receptor-activated Ca2+ influx may involve second messenger-mediated activation of non-selective cation channels (Tsien & Tsien, 1990; Fasolato et al. 1994). These channels may be Ca2+ permeant and mediate Ca2+ influx directly as well as indirectly by causing membrane depolarization and activation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. In some cell types capacitative Ca2+ influx induced by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores (Putney, 1986) may involve activation of non-selective cation channels (for review, see Parekh & Penner, 1997).

We previously described a Ca2+-permeant non-selective cation channel activated by angiotensin II stimulation in rat adrenal glomerulosa cells (Lotshaw & Li, 1996). Stimulation of Ca2+ influx is essential for angiotensin II or elevated extracellular K+ stimulation of aldosterone secretion in these cells (Ganguly & Davis, 1994). Angiotensin II was observed to increase single channel open probability and this effect may contribute to stimulation of aldosterone secretion by directly mediating Ca2+ influx as well as by mediating membrane depolarization and activation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Single channel conductance, permeability and gating behaviour of this channel were very similar to that of a histamine-activated Ca2+-permeant non-selective cation channel in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (Yamamoto et al. 1992) and endocardial endothelial cells (Manabe et al. 1995). Channel gating did not require cytosolic Ca2+ in either cell type and consisted of relatively voltage-independent long duration open and closed states. Furthermore, single channel current-voltage (I-V) relationships were non-linear in both glomerulosa and endothelial cell channels, apparently due to voltage-dependent Mg2+ block.

The divalent cation selectivity and permeability of second messenger-operated non-selective cation channels will be important determinants of their contribution to cellular function. Mechanisms that determine divalent cation permeability are largely unknown for this channel class; however, divalent cation permeation has been extensively studied in neurotransmitter- and cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) non-selective cation channels (Changeux et al. 1992; Hollman & Heinemann, 1994; Zagotta & Siegelbaum, 1996) as well as in the highly Ca2+-selective voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCC) (Tsien et al. 1987). Biophysical studies of ion permeation/blockade and site-directed mutagenesis of channel proteins have been utilized to predict the locations and features of pore structures that contribute to divalent cation selectivity and permeation in these channels. These channels are reported to possess multiple divalent cation binding sites within the channel pore that facilitate divalent cation permeation and/or blockade in the presence of much higher concentrations of monovalent cations. All of these channels conduct monovalent cations in the absence of divalent cations, and addition of Ca2+ reduces monovalent cation conductance due to its higher affinity for the binding sites and slower permeation through the channel. In general Mg2+ is much less permeable than Ca2+; this difference has been attributed to its slow dehydration which is necessary for permeation (Hille, 1992). These channels differ widely in their Ca2+ permeability and in their susceptibility to Mg2+ blockade, even within a single channel class (Frings et al. 1995). The high Ca2+ selectivity of VDCC appears to require the presence of only a single high affinity Ca2+ binding site within the pore (Ellinor et al. 1995); neighbouring lower affinity sites together with multi-ion occupancy of the channel are hypothesized to facilitate Ca2+ permeation (Carbone et al. 1997; Dang & McCleskey, 1998).

In the present study divalent cation permeation and blockade of the angiotensin II-regulated non-selective cation channel were examined using permeant Ca2+ and impermeant Mg2+ and Ni2+ cations. The location of divalent cation binding sites was determined from voltage-dependent blockade by Mg2+ and Ni2+. The results of these experiments demonstrated the presence of two divalent cation binding sites within the pore, one near the external mouth of the pore and one deeper within the pore separated from the other by an apparently insurmountable free energy barrier for Mg2+ and Ni2+ permeation. Differences in the characteristics of channel blockade by Ca2+, Mg2+ and Ni2+ suggested that divalent cation association with the external-most site involves partial dehydration of the blocker. These divalent cation binding sites impart ion conductance properties similar to those of the NMDA receptor and CNG channels. Voltage-dependent inhibition of inward conductance is attributable to fast open channel blockade by external Mg2+ binding to the external-most site and inward rectification is attributable to fast open channel blockade at the innermost site by internal Mg2+ and/or other cytosolic cations. These divalent cation binding sites are also postulated to facilitate Ca2+ selectivity and permeation of the channel.

METHODS

Cell culture

Primary cultures of rat adrenal glomerulosa cells were prepared as previously described (Lotshaw & Li, 1986) using female Sprague- Dawley rats weighing 150-200 g (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA). All procedures involving the use and treatment of animals were in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the institutional IACUC committee. Animals were anaesthetized by CO2 inhalation and subsequently killed by decapitation prior to surgical removal of adrenal glands. Isolated glomerulosa cells were plated on fibronectin-treated glass coverslip chips and maintained in culture medium at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2-95 % air. Culture medium consisted of a mixture of Ham's F-12 and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (1:1 by volume) supplemented to contain 2 % fetal calf serum, 8 % horse serum, 0.1 mM ascorbic acid, 1 μg ml−1 insulin, 50 u ml−1 penicillin G and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin, and 1 μm tocopherol. Sera were obtained from Gibco-BRL, collagenase from Worthington Biochemical Corp., and all other reagents from Sigma. Experiments were performed using cells maintained in primary culture from 12 to 48 h.

Patch clamp recording

Single glomerulosa cells were identified by visual appearance under phase-contrast microscopy as previously described (Lotshaw & Li, 1996). Single channel patch clamp recordings were performed in the cell-attached and inside-out patch configurations (Hamill et al. 1981). Glass coverslip chips containing adherent cells were transferred from culture dishes to a recording chamber (0.5 ml volume) and continuously superfused at 1 ml min−1 with a modified Hanks’ saline equilibrated with 100 % O2 (solution 1, Table 1). In cell-attached patch clamp recordings, a high K+ saline was used to zero the resting membrane potential (solution 3, Table 1). All experiments were performed at room temperature (23-26°C). In some inside-out patch experiments, a perfusion pipette was placed in the recording chamber to facilitate rapid changes in the saline on the cytoplasmic face of the patch membrane.

Table 1.

Composition of salines, pipette and bath solutions for cell-attached and inside-out patches

| Salines | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution | NaCl | KCl | CaCl2 | MgCl2 | NaHCO3 | Hepes | Glucose |

| 1 | 140 | 4 | 1.25 | 1.2 | 4.2 | 10 | 5.5 |

| 2 | 140 | 4 | — | 2.45 | 4.2 | 10 | 5.5 |

| 3 | — | 140 | — | 2.45 | 4.2 | 10 | 5.5 |

| Pipette and bath solutions | |||||||

| Solution | NaCl | CaCl2 | MgCl2 | Hepes | EGTA | Glucose | NMDG |

| 4 | 145 | — | — | 10 | 5 | — | — |

| 5 | 150 | 0.1 | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| 6 | 150 | 0.2 | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| 7 | 150 | 1.0 | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| 8 | 146 | 2.5 | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| 9 | 135.5 | 13.75 | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| 10 | 116 | 27.5 | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| 11 | 77 | 55 | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| 12 | — | 110 | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| 13 | 150 | — | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| 14 | 145 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 10 | — | — | — |

| 15 | 145 | — | 2.0 | 10 | — | — | — |

| 16 | 225 | 0.1 | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| 17 | 225 | — | 2.0 | 10 | — | — | — |

| 18 | — | 0.1 | — | 10 | — | 268 | — |

| 19 | — | 0.1 | — | 10 | — | — | 150 |

Solution compositions listed are millimolar. All solutions adjusted to pH 7.4 using NaOH except solutions 3 and 19 which were adjusted using KOH and HCl, respectively.

Patch pipettes were constructed from borosilicate glass capillary tubes (TW 150-4 glass, World Precision Instruments). Pipettes were pulled to give resistances of 5-6 MΩ when filled with 150 mM NaCl pipette saline and were coated with Sylgard (Dow-Corning) to within 100 μm of the pipette tip.

Membrane currents were measured with an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments). Current was low-pass filtered at 2 or 5 kHz (-3 dB) using a four-pole Bessel filter and recorded using a digital audio tape recorder (Sony, Tokyo, Japan) for later analysis. For computer analysis of recorded data, records were sampled at 10 kHz during playback using a TL-1-125 analog-to-digital converter (Axon Instruments) and analysed using pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments).

The compositions of pipette and bath solutions for cell-attached and inside-out patch clamp experiments are listed in Table 1. In most experiments 0.1 mM Ca2+ was included in the external (pipette) solution to block monovalent cation currents through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (Lux et al. 1990). Membrane voltages were corrected for liquid junction potentials caused by the composition of the pipette solution as described (Neher, 1992). Pipette solutions exhibiting liquid junction potentials greater than 2 mV were (normal bath saline with respect to pipette saline): -6.5 mV for 110 mM CaCl2 (solution 12), -3.6 mV for 77 mM NaCl-55 mM CaCl2 (solution 11), -1.9 mV for 116 mM NaCl-27.5 mM CaCl2 (solution 10), 2.8 mV for 75 mM NaCl-134 mM glucose, and 6.0 mV for 37.5 mM NaCl-201 mM glucose. For calculations involving ionic activities, the ionic strengths of the solutions were calculated and appropriate activity coefficients used to convert molarities to activities. Activity coefficients for NaCl were taken from Robinson & Stokes (1960) and CaCl2 activity coefficients were interpolated from Table 1 of Butler (1968). Ca2+ activity coefficients were estimated from that for CaCl2 using the Guggenheim convention: γCa = (γ± CaCl2)2.

Data analysis

The effects of permeant and impermeant divalent ions were measured on unitary Na+ currents conducted through the Ca2+-permeant non-selective cation channels. Single channel events were detected for analysis using the 50 % of threshold criterion. Ca2+ permeation was characterized by measuring the effects of increasing external Ca2+ concentration on single channel conductance and reversal potential (Vrev). The predicted effect of increasing extracellular Ca2+ concentration on the reversal potential of unitary currents was calculated using the Goldman-Hodgkin- Katz (GHK) equation modified for mixtures of monovalent and divalent ions (extracellular Na+ and Ca2+:cytosolic Na+) (Iino et al. 1997):

| (1) |

where ao and ai represent the extracellular and intracellular activities of the indicated ions, PCa and PNa represent the ionic permeabilities of Ca2+ and Na+, respectively, and R, T and F have their usual thermodynamic meanings. The cytosolic Ca2+ concentration was assumed to be zero for this calculation although the experimental cytosolic solution was only nominally Ca2+ free (solution 15, Table 1).

Voltage-dependent inhibition of unitary Na+ currents by Mg2+ and Ni2+ was modelled as a simple open channel block mechanism (Scheme 1). Transitions between the closed (C) and open (O) channel states are described by the opening and closing rate constants β and α, respectively. Transitions between the open and blocked states (B) are described by the association and dissociation rate constants, k1 and k-1, respectively. Unitary current amplitude is assumed to be zero in the blocked state.

Scheme 1.

Open channel blockade by Mg2+ was described in terms of a fast block mechanism in which blocking events were too fast to resolve by the recording system and resulted in a decrease in average open channel current amplitude (Hille, 1992). The location of the blocker binding site within the transmembrane electric field and its affinity for Mg2+ were calculated by fitting the voltage-dependent inhibition of current amplitude to a linearized Langmuir isotherm which incorporated a Boltzmann relationship to account for the effect of voltage on blocker concentration (Woodhull, 1973; Coronado & Miller, 1979; Moczydlowski, 1992):

| (2) |

where io is the unitary current amplitude in the absence of blocking ion, i is the unitary current amplitude in the presence of blocker, [B] is the blocker concentration, Kd(0) is the apparent dissociation constant for blocker binding at 0 mV membrane potential, z is the valence of the blocking ion, δ is the fractional distance across the transmembrane electric field to the blocking site, V is the membrane potential, and F, R and T have their usual thermodynamic meanings. The fractional electrical distance (δ) and Kd(0) were determined from the slope and Y-axis intercept of the linear regression fit to the data, respectively.

Open channel blockade by Ni2+ was analysed in terms of a slow block mechanism in which blocking events were sufficiently long to be resolved and measured (Hille, 1992). In order to distinguish blocking events from open channel current noise and transitions to subconductance substates, a 75 % threshold criterion was adopted for detection of transitions from the open to closed state. The 50 % threshold criterion was retained for detection of channel openings (Colquhoun & Sigworth, 1995). The mean blocked and open times were determined from exponential fits of open and closed dwell time distributions using the method of maximum likelihood. Mean blocked times approached the resolution of the recording system and therefore mean open times were biased by missed blocking events due to the limited bandwidth of the recording system. Mean open times, τo, were adjusted for missed blocking events using a one step correction procedure previously described (Kuo & Hess, 1993a). The dead time of the recording system was approximately 0.15 ms at a cut-off filter setting of 2 kHz.

Analysis of slow open channel blockade required that blocked states be distinguishable from closed states. Current amplitude is zero in both states requiring that states be distinguished by dwell time analysis. At high blocker concentrations, blocking events were much more frequent than closing events, and the distribution of shut (closed and blocked state) dwell time became dominated by the blocker dissociation rate constant (k-1) (Neher & Steinbach, 1978; Lansman et al. 1986). Ni2+ was found to induce a blocked state of much shorter mean duration than the closed state observed in the absence of Ni2+ (Lotshaw & Li, 1996), thus blocked and closed states were readily separated on the basis of shut dwell time.

The voltage-dependent dissociation constant for Ni2+, Kd(V), was calculated as the voltage-dependent dissociation rate constant, k-1(V), divided by the association rate constant, k1(V), after correction for missed blocking events (Neher & Steinbach, 1978). The Ni2+ dissociation constant was used to calculate the fractional distance (δ) across the transmembrane electric field to the blocking site based on a Boltzmann distribution for the concentration of a charged blocker within the transmembrane electric field (Woodhull, 1973; Neher & Steinbach, 1978; Moczydlowski, 1992):

| (3) |

where Kd(0) is the dissociation constant for blocker binding at 0 mV membrane potential, and the remaining variables are as defined above.

The expected shift in Kd(0) for Ni2+ binding caused by the presence of a competitive inhibitor, Mg2+, was predicted by:

| (4) |

where Kapp is the Kd(0) for Ni2+ in the presence of a competitive inhibitor, KdNi is the Kd(0) for Ni2+ in the absence of the competitive inhibitor, [I] is the concentration of the competitive inhibitor, and Ki the dissociation constant of the competitive inhibitor.

RESULTS

Ca2+ permeation and blockade

The effects of extracellular Ca2+ on unitary Na+ currents through non-selective cation channels were studied using inside-out patches. Spontaneously active channels were identified on the basis of their characteristic long open and closed times, relatively voltage-independent gating, single channel conductance, large open channel current noise, and inward rectification in the presence of cytosolic Mg2+ (Lotshaw & Li, 1996). Omission of external (pipette) divalent cations, Mg2+ and Ca2+ (pipette solution 4 and bath solution 15, Table 1) substantially increased inward current amplitude relative to that previously reported with 2 mM Mg2+ and 0.1 mM Ca2+ in the pipette solution (Lotshaw & Li, 1996). The observed increase in current amplitude was primarily attributable to removal of voltage-dependent inhibition by Mg2+ (see Mg2+ block below). Other channel characteristics such as the large open channel current noise, Vrev and inward rectification were unchanged by omission of extracellular divalent cations.

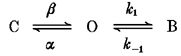

Increasing external Ca2+ caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of inward conductance (Fig. 1). Inhibition appeared to be voltage independent as illustrated by the nearly linear I-V relationships obtained below -20 mV (Fig. 1B). In the absence of external Ca2+ and Mg2+ (solution 4), the I-V relationship for inward current exhibited a nearly linear slope conductance of 37.9 ± 4.5 pS (mean ±s.d., n= 3). Inhibition by external Ca2+ became apparent at concentrations above 0.2 mM and was nearly maximal at 13.75 mM Ca2+. Inward slope conductance was reduced to 10.5 ± 2.6 pS (n= 3, where n is the number of patches) at 13.75 mM Ca2+ compared with 7.5 ± 0.8 pS (n= 3) with 110 mM Ca2+. Plotting the concentration-dependent Ca2+ inhibition of slope conductance as a fraction of maximal conductance and fitting the data to a Langmuir isotherm between the maximum (1.0) and minimum (0.2) fractional conductances yielded an IC50 of 1.4 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Effects of extracellular Ca2+ on unitary Na+ currents.

A, current traces illustrating representative single channel events measured at -80 mV for several Ca2+ concentrations (indicated at the left of each trace). The closed channel current level is indicated by c at the left of the traces; each trace was taken from a different patch. The external (pipette) solution composition for each Ca2+ concentration is described in Table 1; the bath (cytosolic face) saline was nominally Ca2+ free (solution 15). Current records were low-pass filtered at 500 Hz for display. B, I-V relationships are plotted from data obtained with 0.1 mM Ca2+ (▴, n= 5), 1.0 mM Ca2+ (•, n= 5) and 27 mM Ca2+ (▪, n= 3) pipette solutions. Symbols indicate the mean (±s.e.m.) unitary current amplitude; error bars are not shown for errors less than symbol size. Smooth curves represent polynomial regression fits to each data set. C, fractional inward slope conductance is plotted as a function of Ca2+ concentration: γB represents mean conductance at each Ca2+ concentration and γ the mean maximal conductance in the absence of external Ca2+. The smooth curve represents the best fit to a Langmuir isotherm, indicating an IC50 of 1.4 mM for Ca2+ inhibition. D, Vrev of unitary currents is plotted as a function of external Ca2+ activity. Symbols represent the mean (±s.e.m.) of 3-5 determinations at each concentration; symbols lacking error bars represent the means of 2 determinations. The smooth curve represents the change in Vrev predicted from the modified GHK equation (eqn (1)) assuming a constant Ca2+:Na+ permeability ratio of 4.

Ca2+ inhibition of inward Na+ current may be attributed to multiple effects, such as blockade of the pore during Ca2+ permeation and/or surface charge screening. This channel was previously reported to be Ca2+ permeable based on Vrev measurements from inside-out patches under biionic conditions (Lotshaw & Li, 1996). The effect of increasing extracellular Ca2+ concentration (activity) on Vrev is shown in Fig. 1D. Vrev was determined from the voltage axis intercept of either a straight line drawn between the nearest inward and outward mean current amplitude or from polynomial regression fits of the I-V relationship from each patch examined. Vrev shifted in a positive direction as external Ca2+ concentration was increased. These data could be approximated by the GHK equation (eqn (1)) for a channel exhibiting a constant Ca2+:Na+ permeability ratio of 4, in agreement with our previous data (Lotshaw & Li, 1996). These results provide further documentation of the permeability of the channel to Ca2+ and indicate that Ca2+ inhibited Na+ conductance by binding to one or more sites in the pore during permeation. The IC50 for Ca2+ inhibition is within the physiological range of Ca2+ concentrations, indicating that Ca2+ permeation is expected to occur under physiological ionic conditions. These data further suggested the absence of substantial negative surface charge at the external mouth of the pore. If a significant surface charge existed then low Ca2+ concentrations may have been expected to screen surface charge, reducing Na+ concentration at the mouth of the pore, and shifting Vrev as previously described for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (Lewis, 1979).

Mg2+ blockade

Cytosolic Mg2+ was previously shown to block outward unitary Na+ current, resulting in inward rectification of the I-V relationship (Lotshaw and Li, 1996). In that study it was further suggested that external Mg2+ was responsible for the observed voltage-dependent inhibition of inward Na+ currents as had been reported for histamine-activated Ca2+-permeant non-selective cation channels in endothelial cells (Yamamoto et al. 1992). This suggestion was confirmed in the present study. Omission of external Mg2+ linearized the I-V relationship for inward Na+ current, increasing slope conductance from 17.8 pS in the presence of 2 mM external Mg2+ (Lotshaw & Li, 1996) to 37.9 pS in its absence without affecting Vrev (Fig. 1B).

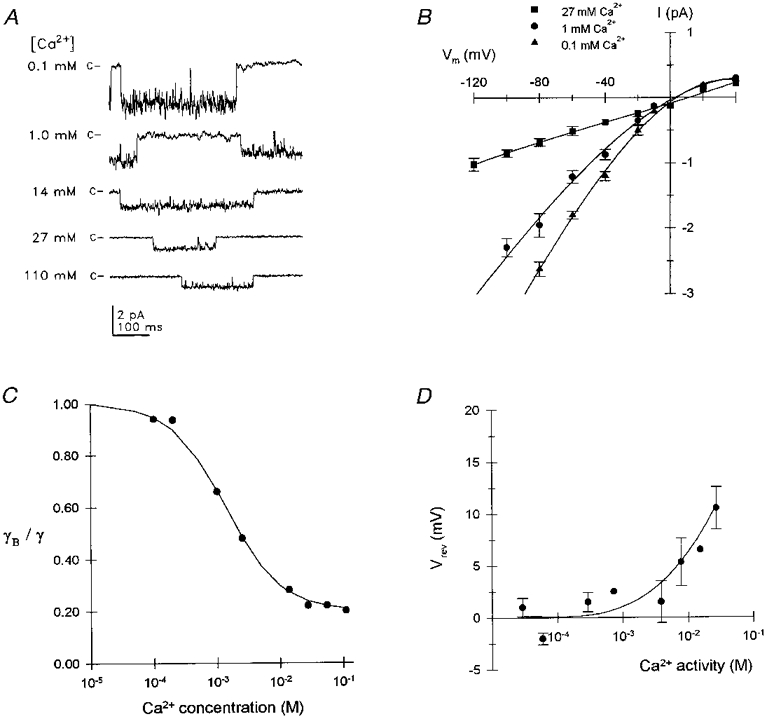

The effects of Mg2+ on unitary Na+ currents were further examined by comparing the I-V relationships obtained in the presence of external or internal 2 mM Mg2+ to that obtained in the absence of both external and internal Mg2+ (Fig. 2). In the absence of external and internal Mg2+, the I-V relationship for inward and outward Na+ current was nearly linear, exhibiting a mean slope conductance of 42.5 pS and a Vrev of 0 mV (Fig. 2B). Addition of 2 mM Mg2+ to the internal (bath) saline caused strong voltage-dependent inhibition of outward Na+ current with little effect on inward current. Addition of 2 mM Mg2+ to the external (pipette) solution, in the absence of cytosolic Mg2+, caused voltage-dependent inhibition of inward current that was much weaker than internal Mg2+ inhibition of outward current. External Mg2+ also inhibited outward Na+ current to some extent (Fig. 2A and B). Vrev was not significantly affected by either cytosolic or extracellular 2 mM Mg2+. The voltage dependence of Mg2+ inhibition and relief of inhibition by oppositely directed Na+ current suggested that Mg2+ inhibited open channel Na2+ current by reversibly blocking the pore at a site(s) within the transmembrane electric field.

Figure 2. Voltage-dependent inhibition of unitary Na+ currents by external and internal 2 mM Mg2+.

A, current traces illustrating representative single channel events obtained from inside-out patches at membrane potentials of 60 and -60 mV in the absence of both external and internal Mg2+ (left traces), with 2 mM internal Mg2+ (middle traces), and with 2 mM external Mg2+ (right traces). The patch recording for 2 mM external Mg2+ exhibited two open channel current levels. The closed channel current level is indicated by c at the left of each trace. Subscripts o and i designate external and internal Mg2+, respectively. Pipettes contained either solution 5 (0 Mg2+) or solution 14 (2 mM Mg2+) and the bath contained either solution 13 (0 Mg2+) or solution 15 (2 mM Mg2+) (Table 1). Current traces were low-pass filtered at 500 Hz for display. B, I-V relationship for single channel currents measured for each Mg2+ condition described in A. Symbols represent the mean (±s.e.m.) of unitary current amplitude from 3 or 4 separate patches in each configuration; error bars were omitted when error was less than symbol size. Lines represent polynomial least-squares regression fits to each data set. C, linearized logarithmic plot (eqn (2)) of voltage-dependent inhibition of unitary Na+ curent amplitude by extracellular and cytoplasmic 2 mM Mg2+. Symbols represent the reduction in current (io/i) - 1, where io represents the mean maximal current in the absence of Mg2+ and i represents the mean current recorded with 2 mM Mg2+o/0 mM Mg2+i (▪) or 0 mM Mg2+o/2 mM Mg2+i (▴); data from B. Curves represent the linear regression fit to the data.

Mg2+ inhibition of unitary Na+ current was modelled as a fast open channel block mechanism. Graphical analysis of a linearized logarithmic plot of the Mg2+ inhibition data (eqn (2)) was used to calculate the apparent affinity and location of Mg2+ binding sites (Fig. 2C). The slope and intercept from regression fits over the linear range of the data were used to calculate the fractional transmembrane electrical distance to the binding sites and the Kd(0) for Mg2+ binding. This analysis indicated that external Mg2+ blocked inward Na+ current by binding to a site exhibiting a Kd(0) of 5.1 mM for Mg2+ and located 19 % (δ= -0.19) of the distance through the transmembrane electrical field from the external surface. The slope of the curve for internal Mg2+ blockade was steeper than for external Mg2+ blockade and indicated that internal Mg2+ blocked the channel by binding to a site exhibiting a Kd(0) of 1.7 mM for Mg2+ and located 36 % (δ= 0.36) of the distance through the transmembrane electrical field from the internal surface. The data could not be approximated by assuming that extracellular and cytosolic Mg2+ acted by binding to the same site. The linearity of the inhibition curves with increasing membrane polarization indicated that Mg2+ was not measurably permeant. If Mg2+ was permeant, increasing membrane polarization would have been expected to facilitate permeation, reducing inhibition. This is consistent with the presence of distinct binding sites for external and internal Mg2+.

Ni2+ blockade

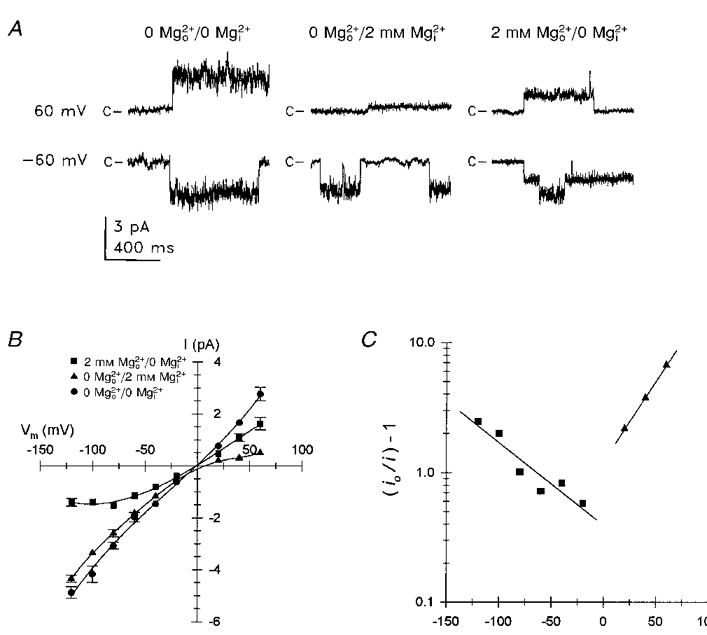

Further evidence supporting the hypothesis that external Ca2+ and Mg2+ inhibited unitary Na+ currents by blocking the open channel pore was provided by the observation that external Ni2+ caused discrete fluctuations in open channel Na+ currents. The effect of external Ni2+ on single channel currents is illustrated in cell-attached patch recordings (Fig. 3). Cell-attached patches were utilized for these experiments due to channel run-down in the inside-out configuration. However, no differences were observed between the effects of Ni2+ on cell-attached patches and the limited data obtained from inside-out patches. In the absence of Ni2+, single channel events exhibited long open and closed times which lasted up to several seconds but occasionally exhibited short open and closed times (Lotshaw & Li, 1996). Addition of Ni2+ induced rapid fluctuations between the open and closed channel current levels attributable to short-lived blockade of the open channel current. The frequency of blocking events increased with Ni2+ concentration and membrane hyperpolarization. At a Ni2+ concentration of 0.5 mM and membrane potential of -120 mV, open channel current amplitude was suppressed due to the high frequency of blocking events (Fig. 3). Ni2+ did not appear to affect channel gating; however, it was not possible quantitatively to assess Ni2+ effects on burst and interburst durations due to the high variability of these parameters and the small number of burst and interburst intervals actually recorded.

Figure 3. External Ni2+-induced fluctuations in unitary Na+ currents.

Current traces illustrating representative single channel events recorded from cell-attached patches at -60 mV (upper traces) and -120 mV (lower traces) in the absence of Ni2+ (control traces, left), in 0.05 mM Ni2+ (middle traces), and in 0.5 mM Ni2+ (right traces). The pipettes contained solution 5 (Table 1) with Ni2+ added hyperosmotically. Resting membrane potential was set to 0 mV with a high K+ saline (solution 3). Expanded time scale segments of current traces recorded at -120 mV are shown to illustrate Ni2+-induced blocking events. The closed and blocked channel current levels are indicated by c at the left of each trace. Current traces were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz.

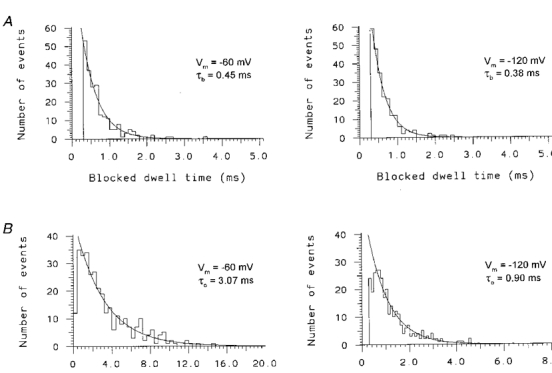

Ni2+ blockade was modelled as a slow open channel block mechanism. Characterization of Ni2+ blockade required distinguishing the closed state from the blocked state, both of which are non-conducting states. In the absence of Ni2+ the channel was previously reported to exhibit multiple exponential components in the open and closed dwell time histograms during periods of active gating (Lotshaw & Li, 1996). Mean open times ranged from 33 to 491 ms and mean closed times ranged between 3.3 and 788 ms at the resting membrane potential (near -80 mV). Channel gating was weakly voltage dependent, which was manifested as a decrease in the long open state duration with membrane hyperpolarization. The short-lived closed state (mean closed time of 3.3 ms) could potentially bias measurement of the blocked state; however, channels did not typically exhibit this state. Furthermore, the frequency of Ni2+-induced blocking events greatly exceeded the frequency of normal channel closures and the mean duration of the closed/blocked state in the presence of Ni2+ was nearly 7-fold less than the short-lived closed state. Thus Ni2+ blocking events could be readily separated from closed states and quantitatively analysed from the intraburst open and closed state dwell time distributions.

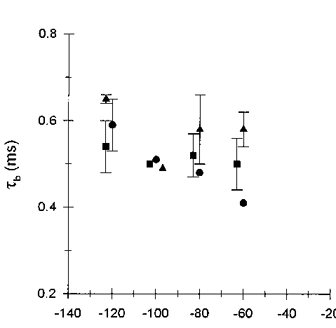

Representative dwell time histograms for intraburst open and closed (blocked) states obtained from a single patch with 0.1 mM Ni2+ in the pipette solution are shown in Fig. 4. The dwell time distributions for both blocked and open states were best described by single exponential relaxations at all membrane potentials and Ni2+ concentrations examined. The voltage and concentration dependence of the mean blocked times (τb) are shown in Fig. 5. The relatively large variability in the time constants primarily reflects variability in the number of blocking events recorded from a given patch at each membrane potential. Each time constant measurement was based on at least 100, and as many as 900, blocking events. Mean blocked time was independent of Ni2+ concentration as required by the open channel blockade model and was not significantly voltage dependent at any Ni2+ concentration examined. In this regard the blocked state dwell times approached the temporal resolution of the recording when filtered at a cut-off frequency of 2 kHz. In favourable patches, the cut-off filter frequency was increased to 5 kHz; this did not alter the estimate of τb nor reveal a voltage dependence for τb. Mean blocked times could not usually be determined at membrane potentials below -60 mV due to interference from K+ channel currents. At high Ni2+ concentrations (0.5 mM) τb may have been artificially lengthened due to missed channel openings as mean open time (τo) progressively decreased with increasing Ni2+ concentration and hyperpolarization (Fig. 3).

Figure 4. Open and blocked state dwell time histograms for 0.1 mM Ni2+ blockade of unitary Na+ currents.

A, blocked state dwell time histograms measured at -60 mV (left graph) and -120 mV (right graph) from a single cell-attached patch with 0.1 mM Ni2+ in the pipette solution (solution 5, Table 1). B, open state dwell time histograms measured at -60 mV (left graph) and -120 mV (right graph) from the same patch as in A. The resting membrane potential was set to 0 mV with a high extracellular K+ saline (solution 3). The smooth curves in each graph represent the maximum likelihood fit of the data to a single exponential relaxation. The time constants of the fitted exponential relaxations for τb (A) and τo (B), and membrane potentials (Vm) are indicated in the inset of each histogram.

Figure 5. Effects of membrane potential and Ni2+ concentration on τb.

Mean blocked times measured in the presence of 0.05 mM (•), 0.2 mM (▪) and 0.5 mM (▴) Ni2+ at -60, -80, -100 and -120 mV; symbols are offset to illustrate clearly standard deviations of the data. Symbols represent the mean (±s.d.) of 3-4 separate patches at each voltage and Ni2+ concentration; symbols lacking error bars represent the mean value from two separate patches.

As shown in Fig. 4, the open state dwell time histograms were well described by single exponential functions. At all Ni2+ concentrations examined, τo determined from the exponential fit was severalfold less than the minimum τo measured in the absence of Ni2+ (33 ms; Lotshaw & Li, 1996). Thus the rate constant for channel closing, α, did not significantly affect the open state dwell time distributions obtained from analysis of intraburst open times in the presence of Ni2+. Patch-to-patch variation in τo, measured at each voltage and Ni2+ concentration, was similar to that shown for τb (data not shown). Again, the variability primarily reflected the number of events recorded from each patch at any given membrane potential.

In contrast to τb, τo was highly voltage and concentration dependent in the presence of Ni2+ (Fig. 6, see below). These data indicated that Ni2+ blocked the channel by binding to a single site located within the transmembrane electric field. Further experiments indicated that the Ni2+ binding site was located in the channel pore. As observed for Mg2+ blockade, if external Ni2+ blocked the channel by occluding the pore then blockade may be opposed by outwardly directed currents due to electrostatic repulsion between Ni2+ and permeating Na+. This effect was observed in inside-out patches bathed in Mg2+-free NaCl solutions on both sides of the patch (data not shown). High concentrations of external Ni2+ (2 mM) reduced inward open channel current to spike-like, small amplitude events as expected for high concentrations of a slow blocker, but had little effect on outward currents even at small positive membrane potentials (20-40 mV). Whereas the concentration of external Ni2+ at a site located within the transmembrane electric field is expected to decrease at positive potentials due to the effects of the electric field, this effect could not account for the observed decrease in channel block.

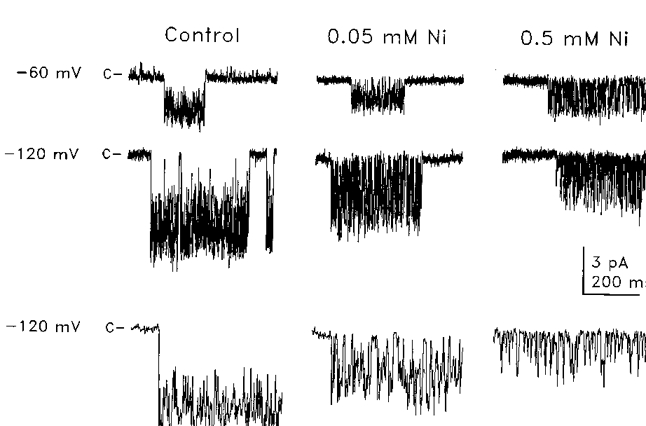

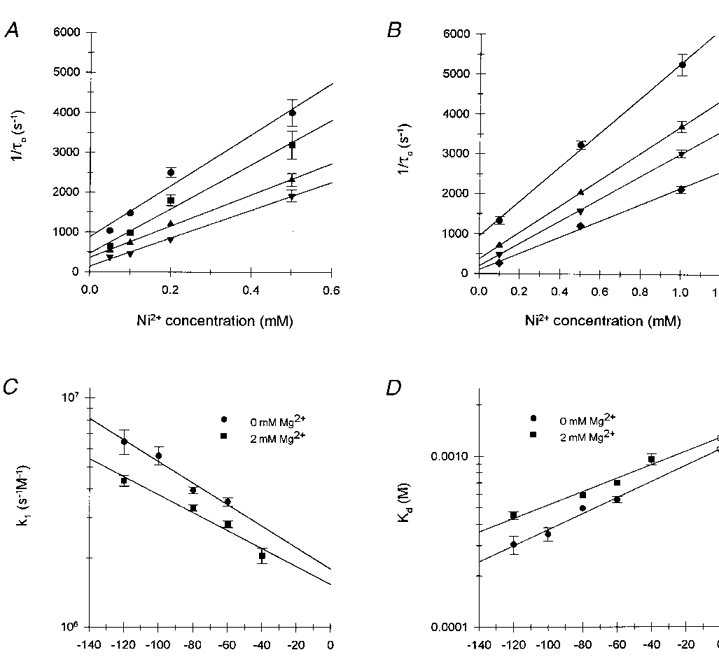

Figure 6. Determination of Kd(0) and location (δ) of the Ni2+ binding site in the absence and presence of external Mg2+.

A, the reciprocal of τo for Ni2+ blockade in the absence of external Mg2+ (pipette solution 5) is plotted as a function of external Ni2+ concentration. Data are shown for membrane potentials of -120 mV (•), -100 mV (▪), -80 mV (▴) and -60 mV (▾). Values of τo represent single exponential maximum likelihood fits to pooled data from 2-4 patches at each voltage and Ni2+ concentration; the number of pooled blocking events for each τo ranged between 300 and 1400. Values of τo were corrected for missed blocking events. Error bars indicate the standard deviation and are not shown for values less than symbol size. B, reciprocal τo values for Ni2+ blockade, measured in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ (solution 14), are plotted as a function of Ni2+ concentration. Data are shown for membrane potentials of -120 mV (•), -80 mV (▴), -60 mV (▾) and -40 mV (♦). Values of τo and error bars are as described in A; each value represents fits to pooled data from 2-4 patches containing 500-700 blocking events. C, voltage-dependent association rate constants, k1(V), determined from the slope of the regression lines in A and B for Ni2+ blockade in the absence (•) and presence (▪) of 2 mM external Mg2+, respectively. Error bars represent the standard error of the regression coefficients. D, the voltage dependence of the dissociation constant, Kd, for Ni2+ binding in the absence and presence of 2 mM Mg2+. Open symbols represent Kd(0) determined from extrapolation of the linear regression fits to each data set (continuous curves). Error bars represent the error extrapolated from the standard errors for k1(V). For all figures, smooth curves represent the linear regression fits to the data.

The dissociation constant (Kd) for Ni2+ binding and the location (δ) of the binding site in the transmembrane electric field were calculated from eqn (3). For these calculations τo was determined from single exponential fits of the pooled data from all patches at each Ni2+ concentration and membrane potential; τo was then corrected for missed blocking events using the voltage-independent τb obtained from all experiments (0.51 ± 0.02 ms, mean ±s.e.m.). Voltage-dependent Ni2+ association rate constants, k1(V), shown in Fig. 6C, were determined from the slope of linear regression fits to 1/τo (Fig. 6A). Voltage-dependent dissociation constants, Kd(V), were calculated from k1(V) and the voltage-independent dissociation rate constant (k-1) determined from the reciprocal of the voltage-independent τb (0.51 ms). Linear regression analysis of the semilogarithmic plot of Kd(V) as a function of membrane potential (Fig. 6D) yielded a site exhibiting a zero voltage dissociation constant, Kd(0), of 1.09 mM for Ni2+ binding and located 13.7 % (δ= -0.137) of the distance through the transmembrane electric field from the extracellular surface.

Effect of Mg2+ on Ni2+ block

The similarity in δ values for channel blockade by external Ni2+ and Mg2+ suggested that the two ions blocked the channel by binding at the same site. If the two ions compete for binding then the apparent Kd for Ni2+ binding is expected to increase in the presence of Mg2+. This hypothesis was tested by repeating the measurement of Kd(0) and δ for external Ni2+ binding in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+. At this Mg2+ concentration unitary Na+ current amplitude remained large enough to allow measurement of Ni2+ blocking events. In the presence of Mg2+, Ni2+ again caused voltage- and concentration-dependent slow blockade of inward Na+ currents with open and blocked dwell time distributions best described by single exponential relaxations (data not shown). External 2 mM Mg2+ increased τo for Ni2+ blockade relative to values for the same Ni2+ concentration and voltage obtained in the absence of Mg2+. The voltage-dependent Ni2+ association rate constants, k1(V), calculated as the regression coefficients of the data in Fig. 6A and B were significantly decreased by Mg2+ when measured at the same voltage (P < 0.05, analysis of covariance; Fig. 6C). External Mg2+ did not affect τb for Ni2+ blockade, which was again found to be independent of Ni2+ concentration and voltage (data not shown); τb was 0.51 ± 0.02 ms (mean ±s.e.m.) in the presence of Mg2+.

Kd(0) and δ for Ni2+ binding in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ were again calculated using eqn (3) as described above (Fig. 6D). The Mg2+-induced decrease in k1(V) increased the corresponding Kd(V) and Kd(0) determined by extrapolation of the regression fit to Kd(V). In the presence of 2 mM external Mg2+, Kd(0) for Ni2+ binding increased from 1.09 mM in the absence of Mg2+ to 1.27 mM. Although this increase was not statistically significant due to uncertainty in the slope of the regression lines, it was consistent with the hypothesis that external Mg2+ and Ni2+ compete for binding at a single site in the pore. If Mg2+ affected Ni2+ binding purely through competition for a single binding site then, from eqn (4), 2 mM Mg2+ would have been predicted to increase the Kd(0) for Ni2+ binding to 1.5 mM, slightly greater than the measured increase.

External Mg2+ also appeared slightly to decrease the voltage dependence of the Kd for Ni2+, shifting the calculated location of the Ni2+ binding site outwards to 11.5 % (δ= -0.115) of the transmembrane electric field. If Mg2+ was acting purely through competition for binding then the voltage dependence of the Kd for Ni2+ binding should not have been affected. This effect was small and not statistically significant but suggested that external Mg2+ may affect Ni2+ binding by surface charge screening as well as by competition for binding.

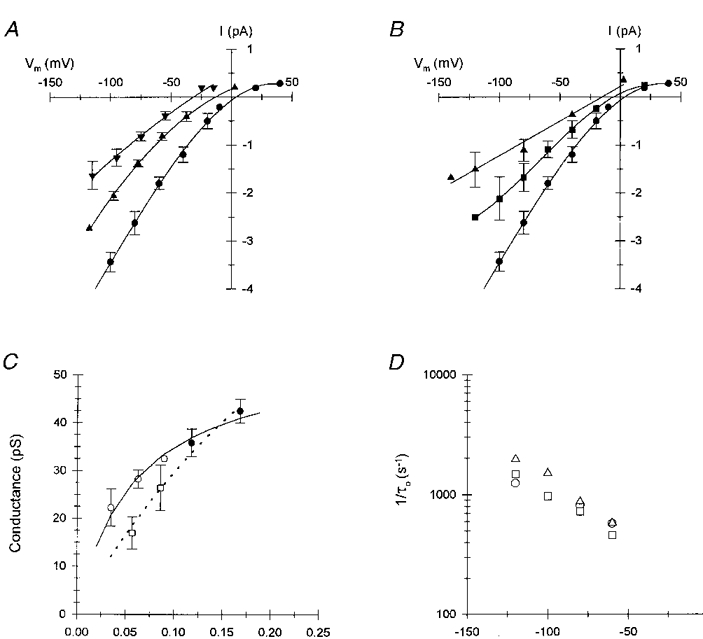

Surface charge effects

The presence of a negative surface potential affecting cation concentrations at the mouth of the pore was investigated in two ways: measuring Na+ conductance at fixed and varied ionic strengths (Green & Andersen, 1991), and measuring the effect of ionic strength on Ni2+ blockade (Kuo & Hess, 1992). The effect of decreasing external Na+ concentration on the single channel I-V relationship is shown in Fig. 7. When NaCl was decreased by replacement with glucose, allowing ionic strength to decrease, inward slope conductance decreased non-linearly with the external NaCl concentration (Fig. 7A and C) and Vrev shifted in accordance with changes in the Na+ equilibrium potential, ENa (Fig. 7A). When ionic strength was maintained by substitution of NMDG+ for Na+ (Fig. 7B), Vrev again shifted with Na+ concentration but inward slope conductance decreased more strongly for a given change in external NaCl concentration (Fig. 7B and C). Single channel conductance is also shown for 225 mM NaCl concentration in the pipette and bath solutions (Fig. 7C); higher NaCl concentrations could not be examined due to instability of the patch seal under such conditions. Single channel conductance data for both glucose and NMDG substitutions could be approximated using the Michaelis-Menton equation although the fits were not very good and this equation is strictly applicable to a one-site single occupancy channel exhibiting a constant surface potential (Coronado & Affolter, 1986). The curve approximating the glucose substitution data assumed a maximum conductance of 55.2 pS and a Km of 58 mM (continuous curve in Fig. 7C). When ionic strength was maintained by substitution of NMDG for NaCl, the data could be approximated by assuming a maximum conductance of 140 pS and a Km of 370 mM (dashed curve in Fig. 7C). The greater conductance in lowered ionic strength saline suggested the presence of negative surface charge acting to increase the Na+ concentration at the mouth of the pore and, consequently, channel conductance. However, the decrease in channel conductance in the presence of NMDG may have been caused by NMDG blockade and/or permeability of the channel. In a separate experiment, channel permeability to NMDG was estimated from Vrev measurements from inside-out patches under biionic conditions (data not shown). In this experiment the pipette saline contained 150 mM NaCl (solution 5) and the bath saline contained 150 mM NMDG (solution 19). The mean Vrev was 72.5 ± 10.6 mV (mean ±s.d., n= 2), indicating a permeability ratio (PNa:PNMDG) of 17.7. Thus NMDG was weakly permeant and the reduction in channel conductance may be attributable to inhibition of Na+ current by NMDG binding and permeation.

Figure 7. Effects of ionic strength on Na+ conductance and Ni2+ blockade.

A, effect of decreasing external NaCl concentration and ionic strength on the I-V relationships of unitary currents obtained from inside-out patches; pipette contained 150 mM NaCl (•), 75 mM NaCl (▴) and 37.5 mM NaCl (▾). Ionic strength was decreased by substitution of glucose for NaCl (mixing solutions 5 and 18, Table 1); the bath contained solution 15. Symbols represent the mean (±s.d.) current amplitude from 3-5 patches at each NaCl concentration; errors less than symbol size are not shown. Smooth curves represent 3rd order or 2nd order (75 and 37.5 mM NaCl) regression fits to the data. B, effect of decreasing external NaCl concentration at constant ionic strength on the I-V relationship; pipette contained 150 mM NaCl (•), 112.5 mM NaCl (▪) and 75 mM NaCl (▴). Ionic strength was maintained by substitution of NMDG for NaCl (mixing of solutions 5 and 19); the bath contained solution 15. Symbols represent the mean (±s.d.) from 3-6 patches at each NaCl concentration. Smooth curves represent 3rd order or linear (75 mM NaCl) regression fits to the data. C, Na+ concentration dependence of inward slope conductance for variable ionic strength (glucose substitution, ○) and constant ionic strength (NMDG substitution, □) data from A and B. Filled circles represent channel conductance in 150 and 225 mM NaCl (pipette solution 16/bath solution 17). Symbols represent the mean (±s.d.) from 3-6 patches for each ionic condition. Continuous and dashed curves represent fits to the Michaelis-Menton equation for the glucose-substituted and NMDG-substituted data, respectively. D, effect of ionic strength on the voltage dependence of reciprocal τo for 0.1 mM Ni2+ blockade of unitary Na+ currents in cell-attached patches: 225 mM NaCl (pipette solution 16, ○), 150 mM NaCl (solution 5, □), or 112.5 mM NaCl (mixing solutions 5 and 18, ▵). Symbols represent reciprocal of corrected τo values determined from data pooled from 3 separate patches containing between 400 and 1500 blocking events at each ionic strength and membrane potential. Standard deviations were less than symbol size.

As described by Kuo & Hess (1992), Ni2+ blockade of Na+ current should provide a more sensitive assay for a surface potential affecting divalent cation concentrations near the mouth of the pore. The τo for Ni2+ blockade is steeply dependent on Ni2+ concentration (Fig. 6A) and should be sensitive to ionic strength if a significant surface potential exists near the mouth of the pore. The effect of ionic strength on the voltage dependence of reciprocal τo values measured in the presence of 0.1 mM Ni2+ is shown in Fig. 7D; the substitution of glucose for NaCl was used to maintain osmolarity of the external solution. As described previously, τo was determined from single exponential fits to data pooled from two to four patches at each potential and ionic strength and corrected for missed blocking events using the mean value for τb. Mean blocked time was not affected by increasing or decreasing ionic strength (data not shown). The Ni2+ association rate was not substantially affected by either increasing external ionic strength to 225 mM NaCl or decreasing ionic strength to 112.5 mM NaCl, although the association rate appeared to increase slightly at the reduced NaCl concentration. These results provided evidence against the presence of a significant negative surface potential affecting cation concentrations at the mouth of the pore under physiological ionic conditions.

DISCUSSION

As with many cation channels, external Ca2+ was found to inhibit monovalent cation conductance of the angiotensin II-regulated non-selective cation channel in rat adrenal glomerulosa cells. Ca2+ inhibition exhibited an IC50 of 1.4 mM, demonstrating that this effect may occur under physiological conditions. Inhibition was attributable to slow Ca2+ permeation, binding of divalent cation-selective sites in the pore and blocking of the single-file flux of Na+ while bound. This type of mechanism has been widely invoked to explain Ca2+ inhibition of monovalent cation conductance in other Ca2+-permeant non-selective channels as well as in the highly Ca2+-selective voltage-dependent channels (for reviews see Tsien et al. 1987; Hollman & Heineman, 1994; Zagotta & Siegelbaum, 1996). If external Ca2+ inhibited inward Na+ current by binding within the pore then inhibition may be expected to exhibit a voltage dependence proportional to the location of the binding site within the transmembrane electric field. However, Ca2+ inhibition was voltage independent in these channels. Voltage-independent blockade by Ca2+ has been described previously in high threshold Ca2+ channels (Lansman et al. 1986; Kuo & Hess, 1993a). In these channels voltage-independent inhibition was attributed to the rapid, approximately diffusion-limited, association rate between Ca2+ and a readily accessible pore site located near the external mouth of the pore. This initial Ca2+ binding is postulated to occur much faster than overall ion translocation, resulting in voltage-independent inhibition. The present study also indicated the presence of a divalent cation binding site near the external mouth of the non-selective cation channel pore. This site may contribute to the rapid, voltage-independent association of Ca2+ with the channel pore. In this regard Ca2+ inhibition of Na+ current resembled fast open channel blockade characteristic of a low affinity pore binding site. The measured IC50 for Ca2+ inhibition of Na+ current (1.4 mM) may then approximate the Ca2+ binding affinity of this site. In other Ca2+-permeant non-selective cation channels exhibiting approximately similar PCa:PNa ratios the Ca2+ affinity of pore binding sites has been estimated to be much higher: 1 μm in CNG channels (Root & MacKinnon, 1993) and 77 μm in NMDA receptor channels (Iino et al. 1997). Thus the structure of Ca2+ binding sites in the glomerulosa cell channel may be expected to differ from those mediating Ca2+ binding in CNG channels and NMDA receptors.

This glomerulosa cell non-selective cation channel was previously reported to be Ca2+ permeant based on Vrev measurements from inside-out patches under biionic conditions (Lotshaw & Li, 1996). The shift in Vrev with increasing external Ca2+ concentration observed in the present study was consistent with that predicted by the GHK equation for a channel exhibiting a constant PCa:PNa ratio of approximately 4. Estimates of the fractional Ca2+ current through other non-selective cation channels based on the GHK equation have not been well substantiated by cytosolic Ca2+ imaging methods (Schneggenburger et al. 1993; Frings et al. 1995). Nevertheless, such studies have demonstrated that channels exhibiting even low PCa:PNa ratios may be expected to provide significant Ca2+ influx under physiological conditions. The IC50 for Ca2+ inhibition of Na+ current demonstrated that this channel interacts with Ca2+ at physiologically relevant Ca2+ concentrations. Surface charge screening by external Ca2+ did not appear to contribute to inhibition of Na+ current. Two lines of evidence indicated that the mouth of the channel pore did not exhibit a significant negative surface potential under physiological ionic conditions: Ni2+ association rates were relatively insensitive to changes in ionic strength (Kuo & Hess, 1992), and low concentrations of Ca2+ or Mg2+ in the external saline did not affect Vrev (Lewis, 1979).

Divalent cation binding sites

The presence of two divalent cation binding sites within the channel pore was demonstrated by voltage-dependent blockade of Na+ current by Mg2+ and Ni2+. The voltage dependence of channel blockade suggested that blockers bound channel sites located within the transmembrane electric field (Woodhull, 1973). The location of these binding sites within the channel pore was indicated by the ability of oppositely directed Na+ current to oppose both Mg2+ and Ni2+ blockade, presumably by electrostatic repulsion between the permeating ion and the blocker. Thus Mg2+ and Ni2+, like Ca2+, are postulated to enter the open channel pore and block single-file ion flux by binding specific sites in the pore. Unlike Ca2+, these blockers appeared unable to permeate the selectivity filter and must exit from the same side as they entered, occluding ion flux as long as they remained bound. The impermeability of the channel to Mg2+ was indicated by the linear relationship between current inhibition and membrane potential (Fig. 2C). If Mg2+ was measurably permeant then increasingly negative (or positive) membrane potentials would have been expected to facilitate permeation, decreasing inhibition of Na+ current with increasingly large positive or negative membrane potential. Mg2+ was also reported to be impermeant to the endothelial histamine-activated non-selective cation channels based on the absence of measurable unitary currents using Mg2+-filled pipettes (Yamamoto et al. 1992). The impermeability of the glomerulosa cell channel to Ni2+ was indicated by the voltage independence of τb for Ni2+ blockade. If Ni2+ was measurably permeant then membrane hyperpolarization would have been expected to facilitate permeation, decreasing τb. Additionally, increasing the permeant ion concentration would have been expected to facilitate Ni2+ permeation and decrease τb as described for weakly permeant divalent blockers of L-type Ca2+ channels (Kuo & Hess, 1993b). However, τb for Ni2+ was insensitive to Na+ concentration.

The apparent impermeability of Mg2+ and Ni2+ is consistent with the asymmetric blockade of Na+ current by external and internal Mg2+. Analysis of these data indicated that external and internal Mg2+ blocked the channel by binding to different sites in the pore. We may further postulate that these binding sites are separated by the selectivity filter, which represents the major free energy barrier to ion permeation. Thus, Mg2+ blockade of the glomerulosa cell non-selective cation channel was similar to that of the histamine-activated Ca2+-permeant non-selective cation channel in endothelial cells (Yamamoto et al. 1992). In the endothelial channel Mg2+ was reported to be impermeant and blockade by external and internal Mg2+ asymmetric; blockade by internal Mg2+ was more effective than external Mg2+.

The hypothesis that external Mg2+ and Ni2+ blocked the channel by binding to the same site located near the external mouth of the pore was supported by data indicating that each blocker acted by binding a single site and by the apparent competition between these ions for binding. External Mg2+ inhibition of inward current yielded a straight line when plotted logarithmically as a function of voltage (Fig. 2C), as expected for a single binding site (Moczydlowski, 1992). Similarly, τb and τo for external Ni2+ blockade were well described by single exponential relaxations, and τo was linearly dependent on Ni2+ concentration, as expected for a single binding site. Competition between Mg2+ and Ni2+ was indicated by the increase in the apparent Kd(0) for Ni2+ in the presence of Mg2+ as expected for a competitive inhibitor. The increase in the apparent Ni2+Kd(0) from 1.09 to 1.27 mM was slightly less than predicted (1.5 mM) from eqn (4), which assumed a dissociation constant for Mg2+ at 0 mV (Ki(0)) of 5.1 mM. This discrepancy may be attributed to the determination of the apparent Mg2+Kd(0) based on data for a single Mg2+ concentration. The absence of a surface charge effect on Ni2+ binding (Fig. 7D) indicated that Mg2+ effects were not caused by surface charge screening.

The present study did not directly address the issue of whether the channel may be simultaneously occupied by two or more ions. The data collected are ambiguous on this point. The monotonic decrease in channel conductance with increasing external Ca2+ concentration would suggest the channel behaves as expected for single-ion occupancy. Similarly, the association rate for Ni2+ blockade exhibited a small increase with decreasing permeant ion concentration as expected for a single-ion pore (Zarei & Dani, 1994). On the other hand, oppositely directed Na+ current very effectively opposed blockade by Mg2+ or Ni2+. It remains to be determined whether this effect was due to simple competition for the external-most binding site or ion-ion interactions within a multi-ion pore.

The distinct differences between channel blockade by external Mg2+ and Ni2+ are postulated to reflect differences in their rates of entry into the pore and binding affinities as opposed to different binding sites for each ion. The observed inhibition of average Na+ current amplitude by Mg2+ is consistent with a fast block mechanism in which the Mg2+ association and dissociation rates are sufficiently fast that average open channel current amplitude is decreased without a measurable change in open channel current fluctuations. Fast blockade is generally considered to be characteristic of low affinity blockers. However, Ni2+ exhibited a Kd(0) of only 1 mM, not much less than that for external Mg2+ (approximately 5 mM), and a comparatively slow voltage-dependent association rate coefficient of 6.4 × 106 M−1 s−1 at -120 mV, measured as the slope of the Ni2+ concentration dependence of 1/τo (Fig. 6A). The slow association rate for Ni2+ suggests that association with the binding site involved partial dehydration of the ion as postulated for Ni2+ blockade of Ca2+ channels (Winegar et al. 1991). The dehydration rate for Ni2+ is approximately 10-fold slower than for Mg2+, which is nearly 1000-fold slower than Ca2+ (Hille, 1992). Ni2+ also exhibited a slow voltage-independent first order dissociation rate of approximately 2000 s−1 indicating a greater stabilization energy for Ni2+ binding than for Mg2+ binding. Similar binding energy differences among divalent cations have been described for other channels and indicate that non-coulombic properties such as co-ordination number and geometry are important determinants of divalent cation binding stability at the external-most binding site (Winegar et al. 1992).

Functional roles of divalent binding sites

The results of the present study indicate that at least two divalent cation binding sites are present within the pore structure of these non-selective cation channels. These sites mediate channel blockade by external and internal Mg2+ and external Ni2+, and may be involved in facilitating Ca2+ selectivity and permeation. The low PCa:PNa ratio and fast block characteristic of Ca2+ suggest that divalent binding sites within the pore exhibit a low affinity for Ca2+, possibly near the IC50 for Ca2+ inhibition of Na+ conductance. The external-most divalent binding site will mediate fast channel block by external Mg2+ under physiological conditions and this effect may have consequences for membrane potential responses and Ca2+ influx during channel activation by angiotensin II. Internal Mg2+ and possibly other cytosolic cations will block outward current through this channel by binding the internal-most binding site. However the physiological relevance of this inward rectification is uncertain in the adrenal glomerulosa cell since the membrane potential has not been reported to attain such depolarized values in this cell type.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the American Heart Association, Illinois Affiliate.

References

- Butler JN. The thermodynamic activity of calcium ion in sodium chloride-calcium chloride electrolytes. Biophysical Journal. 1968;8:1426–1433. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(68)86564-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone E, Lux HD, Carabelli V, Aicardi G, Zucker H. Ca2+ and Na+ permeability of high-threshold Ca2+ channels and their voltage-dependent block by Mg2+ ions in chick sensory neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;504:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.001bf.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux JP, Galzi JL, Devillers-Thiéry A, Bertrand D. The functional architecture of the acetylcholine nicotinic receptor explored by affinity labeling and site-directed mutagenesis. Quarterly Review of Biophysics. 1992;25:395–432. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500004352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Sigworth FJ. Single Channel Recording. New York and London: Plenum Press; 1995. Fitting and statistical analysis of single-channel records; pp. 483–585. [Google Scholar]

- Coronado R, Affolter H. Insulation of the conduction pathway of muscle transverse tubule calcium channels from the surface charge of the bilayer phospholipid. Journal of General Physiology. 1986;87:933–953. doi: 10.1085/jgp.87.6.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronado R, Miller C. Voltage-dependent caesium blockade of a cation channel from fragmented sarcoplasmic reticulum. Nature. 1979;280:807–810. [Google Scholar]

- Dang TX, McCleskey EW. Ion channel selectivity through stepwise changes in binding affinity. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:185–193. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.2.185. 10.1085/jgp.111.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinor PT, Yang J, Sather WA, Zhang J-F, Tsien RW. Ca2+ channel selectivity at a single locus for high-affinity Ca2+ interactions. Neuron. 1995;15:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90100-0. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasolato C, Innocenti B, Pozzan T. Receptor-activated Ca2+ influx: how many mechanisms for how many channels? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1994;15:77–83. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90282-8. 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frings S, Seifert R, Godde M, Kaupp UB. Profoundly different calcium permeation and blockage determine the specific function of distinct cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron. 1995;15:169–179. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90074-8. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A, Davis JS. Role of calcium and other mediators in aldosterone secretion from the adrenal glomerulosa cells. Pharmacological Reviews. 1994;46:417–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green WN, Andersen OS. Surface charges and ion channel function. Annual Review of Physiology. 1991;53:341–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.002013. 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hollman M, Heinemann S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iino M, Ciani K, Tsuzuki K, Ozawa S, Kidokora Y. Permeation properties of Na+ and Ca2+ ions through the mouse NMDA receptor channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1997;155:143–156. doi: 10.1007/s002329900166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C-C, Hess P. A functional view of the entrances of L-type Ca2+ channels: estimates of the size and surface potential at the pore mouths. Neuron. 1992;9:515–526. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90189-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C-C, Hess P. Ion permeation through the L-type Ca2+ channel in rat phaeochromocytoma cells: two sets of ion binding sites in the pore. The Journal of Physiology. 1993a;466:629–655. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C-C, Hess P. Block of the L-type Ca2+ channel pore by external and internal Mg2+ in rat phaeochromocytoma cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1993b;466:683–706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansman JB, Hess P, Tsien RW. Blockade of current through single calcium channels by Cd2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ Journal of General Physiology. 1986;88:321–347. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.3.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CA. Ion-concentration dependence of the reversal potential and the single channel conductance of ion channels at the frog neuromuscular junction. The Journal of Physiology. 1979;286:417–445. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotshaw D, Li F. Angiotensin II activation of Ca2+-permeant nonselective cation channels in rat adrenal glomerulosa cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:C1705–1715. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lux HD, Carbone E, Zucker H. Na+ currents through low-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels of chick sensory neurons: block by external Ca2+ and Mg2+ The Journal of Physiology. 1990;430:159–188. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe K, Ito H, Matsuda H, Noma A, Shibata Y. Classification of ion channels in the luminal and abluminal membranes of guinea-pig endocardial endothelial cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;484:41–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moczydlowski E. Analysis of drug action at single-channel level. Methods in Enzymology. 1992;207:791–806. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07056-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Correction for liquid junction potentials in patch clamp experiments. Methods in Enzymology. 1992;207:123–131. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Steinbach JH. Local anaesthetics transiently block currents through single acetylcholine-receptor channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1978;277:153–176. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB, Penner R. Store depletion and calcium influx. Physiological Reviews. 1997;77:901–930. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JW., Jr A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium. 1986;7:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RA, Stokes RH. Electrolyte Solutions. London: Butterworths; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Root MJ, MacKinnon R. Identification of an external divalent cation-binding site in the pore of a cGMP-activated channel. Neuron. 1993;11:459–466. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90150-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Zhou Z, Konnerth A, Neher E. Fractional contribution of calcium to the cation current through glutamate receptor channels. Neuron. 1993;11:133–143. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90277-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seimen D. Nonselective cation channels. In: Seimen D, Heschler J, editors. Nonselective Cation Channels: Pharmacology, Physiology and Biophysics. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhuser Verlag; 1993. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RW, Hess P, McCleskey EW, Rosenberg RL. Calcium channels: mechanisms of selectivity, permeation and block. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biophysical Chemistry. 1987;16:265–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.16.060187.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RW, Tsien RY. Calcium channels, stores and oscillations. Annual Review of Cell Biology. 1990;6:715–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winegar BD, Kelly R, Lansman JB. Block of current through single calcium channels by Fe, Co, and Ni. Journal of General Physiology. 1991;97:351–367. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.2.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhull AM. Ionic blockage of sodium channels in nerve. Journal of General Physiology. 1973;61:687–708. doi: 10.1085/jgp.61.6.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Chen G, Miwa K, Suzuki H. Permeability and Mg2+ blockade of a histamine-operated cation channel in endothelial cells of rat intrapulmonary artery. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;450:395–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagotta WN, Siegelbaum SA. Structure and function of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1996;19:235–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarei MM, Dani JA. Ionic permeability characteristics of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channel. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;103:231–248. doi: 10.1085/jgp.103.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]