Abstract

Non-muscle contraction is widely believed to be mediated through Ca2+-stimulated myosin II regulatory light chain (LC20) phosphorylation, similar to the contractile regulation of smooth muscle. However, this hypothesis lacks conclusive experimental support.

By modulating chicken embryo fibroblast cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), we investigated the putative role of [Ca2+]i in fetal bovine serum (FBS)-stimulated LC20 phosphorylation and force development in these cells.

Eliminating the FBS-stimulated rise in [Ca2+]i with the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA only partially inhibited FBS-stimulated LC20 phosphorylation and did not significantly alter the magnitude of FBS-stimulated isometric contraction.

Ionomycin (1 μm) produced a larger but shorter lasting rise in [Ca2+]i relative to FBS. However, ionomycin only stimulated a small and transient increase in LC20 phosphorylation and did not cause contraction.

We conclude that fibroblasts differ from smooth muscle in that LC20 phosphorylation and contraction are predominantly regulated independently of [Ca2+]i.

Contraction is an essential component of many fundamental processes in non-muscle cells. Fibroblast contraction mediates orientation of collagen fibres in connective tissue (Harris et al. 1981) and contraction of granulation tissue (Majno et al. 1971). More complex cellular behaviours such as chemotaxis and cytokinesis are mediated by localized contractions within cells (Mabuchi & Okuno, 1977; Jay et al. 1995; Post et al. 1995). Among the myosin superfamily of motor proteins, only myosin II forms bipolar filaments, which can contract cytoplasm in a manner analogous to muscle. Non-muscle myosin II, like smooth muscle myosin II, is activated through phosphorylation of LC20, primarily at Ser19 and to a lesser extent at Thr18 (Sellers & Adelstein, 1987). In smooth muscle, LC20 is phosphorylated predominantly by Ca2+-calmodulin-activated myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) (Somlyo & Somlyo, 1994). However, it has remained unclear if this smooth muscle paradigm of [Ca2+]i-regulated myosin II based contractility also applies to non-muscle cells.

Several lines of evidence support the widely held view that non-muscle cell contraction is regulated similarly to the better characterized process of smooth muscle contraction (i.e. through Ca2+-calmodulin stimulated LC20 phosphorylation). First, MLCK activity endogenous to both fibroblasts and endothelial cells is necessary and sufficient to mediate Ca2+-dependent LC20 phosphorylation and contraction in detergent-permeabilized cell models (Cande & Ezzell, 1986; Wysolmerski & Lagunoff, 1991). Second, MLCK inhibitors decrease LC20 phosphorylation and contraction in non-muscle cells (Lamb et al. 1988; Giuliano et al. 1992; Chrzanowska-Wodnicka & Burridge, 1996). Finally, in some cell types, Ca2+ ionophores stimulate structural alterations resembling cell contraction (Winter et al. 1991; Garcia et al. 1997). However, these studies should be interpreted cautiously for several reasons: (1) permeabilization of cells results in the loss of endogenous soluble molecules (Wysolmerski & Lagunoff, 1991) that may have important roles in the regulation of contraction, (2) protein kinase inhibitors thought to have specificity for MLCK may, in fact, exert their effects through inhibition of other kinases, and (3) cell shape reflects a balance between cytoplasmic contraction and resisting forces from cell adhesion and cytoplasmic stiffness (Chicurel et al. 1998). Therefore the morphological alterations caused by Ca2+ ionophores do not necessarily reflect contraction or [Ca2+]i-stimulated activation of myosin.

To investigate whether the smooth muscle paradigm for the regulation of contraction also applies to non-muscle cells, we used a model system in which chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEF) contract in response to fetal bovine serum (FBS) stimulation. FBS, like most agonists for non-muscle or smooth muscle contraction, stimulates (1) a rise in [Ca2+]i (McNeil et al. 1985), (2) phosphorylation of LC20 (Giuliano et al. 1992; Kolodney & Elson, 1993), and (3) generation of contractile force (Kolodney & Elson, 1993). We quantified fibroblast isometric force generation by attaching a population of cells, cultured within a collagen matrix, to an isometric force transducer (Kolodney & Elson, 1995), thereby allowing direct measurement of cellular force generation. We examined the putative role of [Ca2+]i as the primary regulator of contractility in CEF by either buffering [Ca2+]i or selectively permeabilizing cells to extracellular Ca2+ and measuring the effects of these interventions on LC20 phosphorylation and force generation.

METHODS

Experimental solutions

Ca2+-containing electrolyte solution contained (mM): 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.8 MgCl, 1.2 CaCl2, 0.8 NaH2PO4, 10 Hepes, and 5 glucose. Ca2+-free buffer contained (mM): 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 3 MgCl, 0.8 NaH2PO4, 10 Hepes, 5 glucose, and 2 EGTA.

Cell culture

CEF in primary culture, a gift of Dr E. L. Elson, were grown in Dulbecco's modified essential medium (DMEM, Irvine Scientific) with 10 % FBS at 37°C in a 10 % CO2 incubator, and used between passage 2 and 8.

Intracellular BAPTA loading

CEF were incubated with 10 mM acetoxymethyl BAPTA (BAPTA AM; Molecular Probes) and 0.2 % Pluronic F127 (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at 25°C in Ca2+-containing electrolyte solution. Cells remained in 10 mM BAPTA AM through the remainder of the experiment.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

[Ca2+]i was measured using the Ca2+ indicator dye fura-2 (Molecular Probes). CEF cultured onto coverslips were incubated for 1-2 h at 25°C in 0.25 mM fura-2 AM and 0.2 % Pluronic F127 in the Ca2+-containing electrolyte solution. Coverslips were placed in a flow chamber heated to 37°C on the stage of an epifluorescence microscope and fluorescent light (510 nm) from individual cells was collected at excitation wavelengths of 335 and 405 nm.

Determination of LC20 phosphorylation

LC20 phosphorylation was determined by gel electrophoresis and immunoblot following the procedure of Taylor & Stull (1988).

Measurement of isometric force

Force was measured from CEF cultured in collagen lattices as described previously (Kolodney & Elson, 1995), with modifications. Briefly, CEF were suspended in an ice-cold solution of monomeric collagen in DMEM with 10 % FBS to obtain a final collagen concentration of 2.0 mg ml−1 and cell density of 6 × 105 cells ml−1. One millilitre aliquots of the cell suspension were pipetted into rectangular wells between two strips of Velcro loops glued to glass tubing and separated by a rigid spacer. These preparations were incubated in DMEM with 10 % FBS for 72-96 h. The CEF-containing lattices were mounted to an isometric force transducer, bathed in serum-free Hepes-buffered (25 mM) DMEM and allowed to equilibrate for 1 h prior to each experiment. Force measurements were performed at 37°C in DMEM (containing 1.8 mM Ca2+), except as noted (Fig. 1).

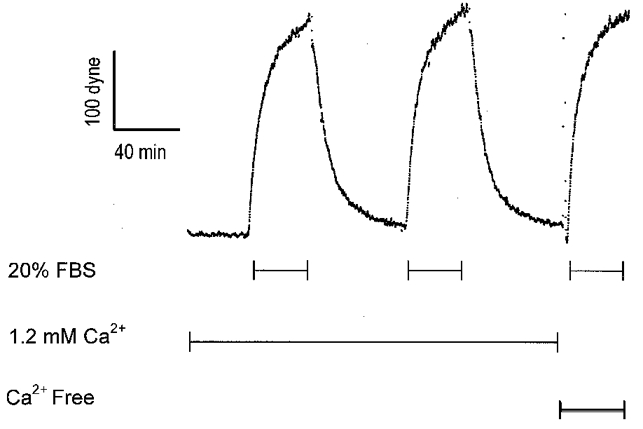

Figure 1. FBS-stimulated force development in the presence and absence of extracellular Ca2+.

Ca2+-free solution contained 2 mM EGTA. The transient rise in force coincident with the change to Ca2+-free solution represents a mechanical artifact resulting from the solution change.

RESULTS

To measure non-muscle cell contraction, a population of fibroblasts cultured within a collagen matrix was attached to an isometric force transducer. FBS (20 %) stimulated an isometric contraction of 150-300 dynes. Washout of FBS resulted in nearly complete relaxation and contraction was reproducible for serial stimulations of the same preparation (Fig. 1).

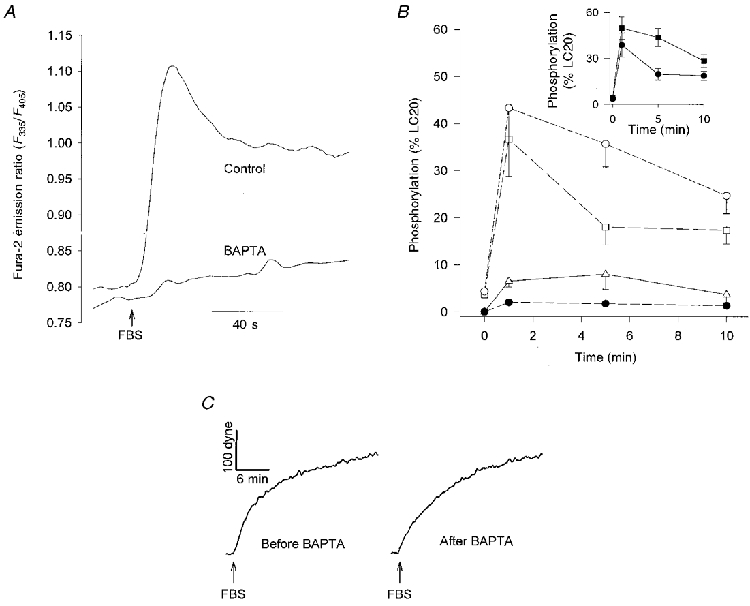

Figure 2A demonstrates that the [Ca2+]i response to FBS was blocked by the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA. In control cells, 20 % FBS simulated a rapid increase followed by a slower decline in [Ca2+]i. This FBS-stimulated [Ca2+]i transient was abolished after the cells were loaded with BAPTA by incubation for 1 h with its cell-permeant acetoxymethyl ester (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Effect of BAPTA on LC20 phosphorylation and force.

A, FBS-stimulated [Ca2+]i response, expressed as the fura-2 emission ratio (F335/F405), in BAPTA-loaded CEF or sham-loaded cells. Each curve is averaged from 50 cells. B, LC20 phosphorylation (as a percentage of total LC20) following stimulation with 20 % FBS at 0 min in control or BAPTA-loaded CEF. ○, mono-phosphorylated LC20 in control CEF; □, mono-phosphorylated LC20 in BAPTA-loaded CEF; ▵, di-phosphorylated LC20 in control CEF; •, di-phosphorylated LC20 in BAPTA-loaded CEF. Each point represents the mean ±s.e.m. (N = 3). Inset displays same data as total phosphorylated LC20 (sum of mono and di-phosphorylated): ▪, control; •, BAPTA. C, FBS-stimulated force development before and after loading with BAPTA. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

The effects of eliminating the [Ca2+]i component of FBS signalling on LC20 phosphorylation are illustrated in Fig. 2B. In control cells, 20 % FBS caused a rise in LC20 phosphorylation that peaked between 1 and 3 min post stimulation and usually began to decrease by 5 min. However, in some experiments, LC20 phosphorylation remained near maximal levels for 10 min. Although BAPTA nearly completely inhibited the FBS-stimulated [Ca2+]i increase, FBS-stimulated LC20 phosphorylation was only partially inhibited by BAPTA. Basal levels of LC20 phosphorylation were similar in cells loaded with BAPTA and control cells. One minute after addition of FBS, total levels of LC20 phosphorylation (sum of mono- and di-phosphorylated) were similar in control and BAPTA-loaded cells; however, di-phosphorylated LC20 was decreased in BAPTA-loaded cells. BAPTA produced its most significant effect on LC20 phosphorylation at 5 min and caused a smaller decrease in total LC20 phosphorylation at 10 min after addition of FBS.

To determine the role of [Ca2+]i in FBS-stimulated force generation, serial recordings of isometric contraction were performed on a population of CEF cultured in a collagen matrix before and after removal of extracellular [Ca2+] (Fig. 1), or before and after loading the cells with BAPTA (Fig. 2C). FBS-stimulated contraction was not affected by removal of extracellular Ca2+. The contractions caused by FBS were similar before and after loading cells with BAPTA, although the BAPTA-loaded preparations appeared to have a slightly slower rate of force development. As expected, control preparations serially stimulated with FBS, but without BAPTA loading between the two contractions, also exhibited similar isometric force responses to each of the two sequential FBS stimulations (data not shown).

In a separate set of experiments, force development in response to FBS was measured from six matched pairs of CEF preparations. Each pair consisted of one BAPTA-loaded preparation and one sham-loaded preparation. The magnitude of force at 20 min after FBS stimulation, was not significantly affected by BAPTA. However, when the responses were fitted to a first-order kinetic model, the rate constant of FBS-stimulated force development was decreased by 35 % in BAPTA-loaded cells (mean ±s.e.m.; control, 0.028 ± 0.003 s−1; BAPTA, 0.018 ± 0.003 s−1; Student's paired t test (d.f. = 6) = 3.303, P < 0.05).

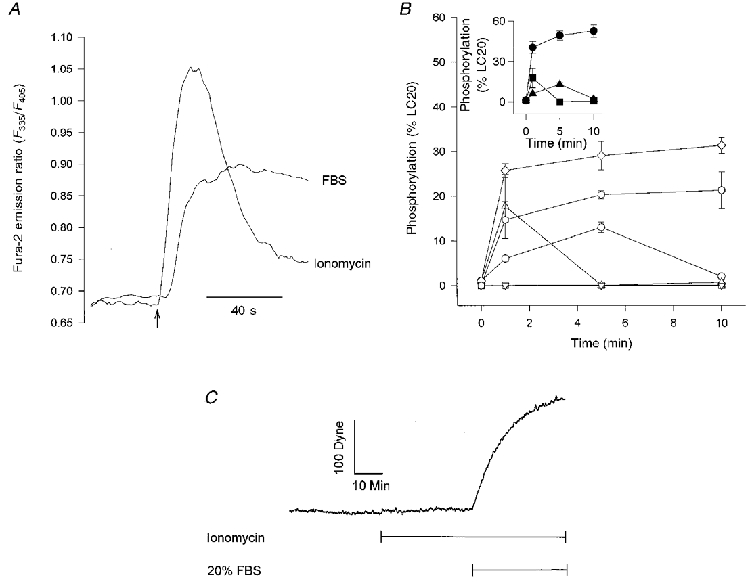

To assess whether elevation of [Ca2+]i was sufficient to stimulate LC20 phosphorylation and contraction, we directly increased [Ca2+]i, with ionomycin, and measured the effects on LC20 phosphorylation and force development. Ionomycin (1 μM) caused an increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3A) greater in magnitude but with a more transient time course than the increase stimulated by FBS (Fig. 1). In spite of the large [Ca2+]i response invoked by ionomycin, phosphorylation of LC20 was much less and more transient after ionomycin than after FBS (Fig. 3B). Ionomycin (1 μM) caused an increase in total LC20 phosphorylation that peaked at 5 min, reaching only 26 % of the FBS response. A higher concentration of ionomycin (5 μM) resulted in a more rapid but also a more transient increase in LC20 phosphorylation. In contrast to FBS, ionomycin (1 μM) did not cause di-phosphorylation of LC20.

Figure 3. Effect of ionomycin on LC20 phosphorylation and force.

A, the ionomycin (1 μM)- or FBS (20 %)-induced [Ca2+]i responses expressed as the fura-2 emission ratio (F335/F405) averaged from 7 cells. FBS or ionomycin was added at the time indicated by the arrow. B, LC20 phosphorylation after addition of ionomycin or 20 % FBS at 0 min. Each data point represents the mean ±s.e.m. (n = 3). ⋄, FBS mono-phosphorylated; ○, 1 μM ionomycin mono-phosphorylated; ▵, 5 μM ionomycin mono-phosphorylated; ○, FBS di-phosphorylated; ▿, 1 μM ionomycin di-phosphorylated; □, 5 μM ionomycin di-phosphorylated. Inset contains the same data displayed as total phosphorylated LC20 (sum of mono- and di-phosphorylated): •, FBS; ▴, 1 μM ionomycin; ▪, 5 μM ionomycin. C, force development by CEF exposed to 1 μM ionomycin followed by the addition of 20 % FBS. Similar tracings were obtained with 0.1 and 5 μM ionomycin (n = 5).

A representative isometric force measurement for CEF treated with ionomycin is displayed in Fig. 3C. Ionomycin did not measurably affect contractile force. The absence of a significant effect of ionomycin on contractility was not due to toxicity from elevated [Ca2+]i since cells contracted normally if stimulated by FBS during ionomycin treatment. Varying the ionomycin concentration (0.1 and 5 μM) also failed to elicit measurable contraction (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that a substantial fraction of the LC20 phosphorylation stimulated by FBS is not mediated by an increase in [Ca2+]i. Several recently elucidated mechanisms could potentially provide Ca2+-independent pathways for LC20 phosphorylation in non-muscle cells. For example, kinases other than MLCK, such as rho-kinase (Amano et al. 1996) or gamma p21-activated kinase (Ramos et al. 1997) can directly phosphorylate LC20 at its activating sites. Moreover, MLCK activity can be modified though phosphorylation by multifunctional protein kinases such as cAMP-dependent kinase (Garcia et al. 1997), mitogen-activated protein kinase or cyclin-dependent kinase-1 (Morrison et al. 1996). Another Ca2+-independent mechanism for regulation of LC20 phosphorylation involves modulation of myosin light chain phosphatase activity (Kimura et al. 1996; Shasby et al. 1997).

Rho, a small monomeric GTPase, has recently been shown to cause Ca2+-independent LC20 phosphorylation through activation of the rho-associated kinase (Amano et al. 1996). In addition to directly phosphorylating LC20, rho-associated kinase further enhances LC20 phosphorylation through inhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase (Kimura et al. 1996). Several recent studies have demonstrated that activation of rho mediates many morphological correlates of non-muscle contractility, such as formation of stress fibres (Chrzanowska-Wodnicka & Burridge, 1996; Amano et al. 1997; Yee, 1998), purse-string closure of wounds (Brock et al. 1996), and TNF-α-stimulated endothelial retraction (Wójciak-Stothard et al. 1998). Moreover, preliminary results from our laboratory suggest that inhibition of rho blocks both CEF contraction and LC20 phosphorylation (M. S. Kolodney, M. S. Thimgan, and H. F. Yee Jr, unpublished observations). Thus, our results are consistent with an emerging paradigm in which non-muscle contractile events formerly thought to require Ca2+ activation of MLCK might instead be mediated through alternative signalling pathways, such as rho.

In intact smooth muscle and cultured smooth muscle cells, Ca2+ ionophores are potent stimulators of LC20 phosphorylation (Taylor & Stull, 1988). In fibroblasts, we have demonstrated that ionomycin produces a relatively small and transient increase in LC20 phosphorylation. Measurements of endothelial cell LC20 phosphorylation have also demonstrated a weak or negative response to Ca2+ ionophores. Shasby and coworkers (1997) found a transient increase in LC20 phosphorylation despite a sustained [Ca2+]i elevation in α-toxin-permeabilized endothelial cells. Moreover, Garcia and coworkers (1997) showed that ionomycin decreases endothelial LC20 phosphorylation to below baseline levels. Both studies included evidence suggesting that enhancement of myosin light chain phosphatase activity by [Ca2+]i contributed to the lack of a sustained increase in LC20 phosphorylation. The transient nature and small magnitude of the LC20 phosphorylation that we measured after ionomycin might also have resulted from activation of a myosin light chain phosphatase by [Ca2+]i.

In smooth muscle, force development (in response to agonist stimulation) is typically mediated by release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores while maintenance of tone is more dependent on extracellular Ca2+ influx (Nelson et al. 1990). In fibroblasts, we found that FBS-stimulated contraction was not altered by removal of extracellular Ca2+. This finding alone does not preclude a role for Ca2+, since release from intracellular stores may be sufficient to fully mediate contraction. However, BAPTA eliminated the [Ca2+]i response to FBS without altering the magnitude of contraction, demonstrating that the FBS-stimulated rise in [Ca2+]i is unnecessary for contraction.

Ionomycin did not cause significant contraction, which is somewhat surprising since this ionophore did stimulate a modest but significant increase in LC20 phosphorylation. However, force resulting from this small amount of LC20 phosphorylation might not be effectively transmitted to the cell surface and therefore might not affect the mechanical output of the cell. Another possible explanation for the absence of contraction after ionomycin is that processes other than LC20 phosphorylation, such as the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, or the regulation of thin filament associated proteins (e.g. by protein kinase C) (Walsh et al. 1996), may be critical determinants of fibroblast contraction.

Ca2+ plays a central role in stimulus-contraction coupling in both smooth and striated muscle, and has been thought to play a similar role in non-muscle cells (Sellers & Adelstein, 1987). In this study we used methodology, previously applied to the physiological characterization of smooth muscle, to demonstrate Ca2+-independent contraction in a non-muscle cell type. Our results suggest that despite the in vitro similarities between non-muscle and smooth muscle myosins, non-muscle cells contract through a signalling pathway different from that utilized in smooth muscle. Ca2+ is an ideal signal for the rapid and precise temporal control of contraction required in muscle because the large Ca2+ concentration gradient across cell membranes facilitates rapid changes in [Ca2+]i. However, in contrast to muscle cells, which contract uni-axially, non-muscle cells require more exact spatial control of contractility. Given these considerations, we speculate that the [Ca2+]i-independent signalling pathways that control fibroblast contraction may be better suited to direct the highly localized but relatively slow changes in cell shape characteristic of non-muscle cell behaviour.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. T. Stull for antibody to LC20, E. L. Elson for CEF and comments on the manuscript, K. L. Altemus and J. Monck for comments on the manuscript, and A. Garfinkel and J. Vergara for helpful suggestions. This work was supported in part by awards to H.F.Y. from the NIH (NIDDK), the CURE Digestive Diseases Research Center, the Glaxo-Wellcome Institute for Digestive Health, and the United Liver Association.

References

- Amano M, Chihara K, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Nakamura N, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi KM. Formation of actin stress fibrils and focal adhesions enhanced by Rho-kinase. Science. 1997;275:1308–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1308. 10.1126/science.275.5304.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M, Ito M, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Chihara K, Nakano T, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. Phosphorylation and activation of myosin by Rho-associated kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:20246–20249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock J, Midwinter K, Lewis J, Martin PJ. Healing of incisional wounds in the embryonic chick wing bud: characterization of the actin purse-string and demonstration of a requirement for Rho activation. Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;135:1097–1107. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.4.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cande WZ, Ezzell RM. Evidence for regulation of lamellipodial and tail contraction of glycerinated chicken embryonic fibroblasts by myosin light chain kinase. Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 1986;6:640–648. doi: 10.1002/cm.970060612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicurel ME, Chen CS, Ingber DE. Cellular control lies in the balance of forces. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 1998;10:232–239. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Burridge K. Rho-stimulated contractility drives the formation of stress fibres and focal adhesions. Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;133:1403–1145. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JG, Schaphorst KL, Shi S, Verin AD, Hart CM, Callahan KS, Patterson CE. Mechanisms of ionomycin-induced endothelial cell barrier dysfunction. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:L172–184. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.1.L172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano KA, Kolega J, De Biasio RL, Taylor DL. Myosin II phosphorylation and the dynamics of stress fibers in serum deprived and stimulated fibroblasts. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1992;3:1037–1048. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.9.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AK, Stopak D, Wild P. Fibroblasts traction as a mechanism for collagen morphogenesis. Nature. 1981;290:249–251. doi: 10.1038/290249a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay PY, Pham PA, Wong SA, Elson EL. A mechanical function of myosin II in cell motility. Journal of Cell Science. 1995;108:387–393. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.1.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Ito M, Amano M, Chihara K, Fukata Y, Nakafuku M, Yamamori B, Feng J, Nakano T, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. Regulation of myosin phosphatase by Rho and Rho-associated kinase. Science. 1996;273:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodney MS, Elson EL. Correlation of myosin light chain phosphorylation with isometric contraction of fibroblasts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:23850–23855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodney MS, Elson EL. Contraction due to microtubule disruption is associated with increased phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:10252–10256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb NJ, Fernandez A, Conti MA, Adelstein R, Glass DB, Welch WJ, Feramisco JR. Regulation of actin microfilament integrity in living non-muscle cells by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase and the myosin light chain kinase. Journal of Cell Biology. 1988;106:1955–1971. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.6.1955. 10.1083/jcb.106.6.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabuchi I, Okuno MJ. The effect of myosin antibody on the division of starfish blastomeres. Journal of Cell Biology. 1977;74:251–263. doi: 10.1083/jcb.74.1.251. 10.1083/jcb.74.1.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil PL, Mckenna MP, Taylor DL. A transient rise in cytosolic calcium follows stimulation of quiescent cells with growth factors and is inhibitable with phorbol myristate acetate. Journal of Cell Biology. 1985;101:372–379. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.2.372. 10.1083/jcb.101.2.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majno G, Gabbiani G, Hirschel BJ, Ryan GB, Statkov PR. Contraction of granulation tissue in vitro: similarity to smooth muscle. Science. 1971;173:548–550. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3996.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DL, Sanghera JS, Stewart J, Sutherland C, Walsh MP, Pelech SL. Phosphorylation and activation of smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase by MAP kinase and cyclin-dependent kinase-1. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 1996;74:549–57. doi: 10.1139/o96-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Patlak JB, Worley JF, Standen NB. Calcium channel, potassium channel, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;259:C3–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.1.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post PL, DeBiasio RL, Taylor DL. A fluorescent protein biosensor of myosin II regulatory light chain phosphorylation reports a gradient of phosphorylated myosin II in migrating cells. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1995;6:1755–1768. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.12.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos E, Wysolmerski RB, Masaracchia RA. Myosin phosphorylation by human cdc42-dependent S6/H4kinase/gammaPAK from placenta and lymphoid cells. Receptors and Signal Transduction. 1997;7:99–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers JR, Adelstein RS. Regulation of Contractile Activity. In: Boyer PD, Krebs EG, editors. The Enzymes. Vol. 18. Orlando, FL, USA: Academic Press Inc.; 1987. pp. 381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Shasby DM, Stevens T, Ries D, Moy AB, Kamath JM, Kamath AM, Shasby SS. Thrombin inhibits myosin light chain dephosphorylation in endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:L311–319. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.2.L311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Signal transduction and regulation in smooth muscle. Nature. 1994;372:231–236. doi: 10.1038/372231a0. 10.1038/372231a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DA, Stull JT. Calcium dependence of myosin light chain phosphorylation in smooth muscle cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:14456–14462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh MP, Horowitz A, Clément-Chomienne O, Andrea JE, Allen BG, Morgan KG. Protein kinase C mediation of Ca2+-independent contraction of vascular smooth muscle. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 1996;74:485–502. doi: 10.1139/o96-053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter MC, Peterson MW, Shasby DM. Synergistic effects of a calcium ionophore and activators of protein kinase C on epithelial paracellular permeability. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 1991;4:470–477. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/4.5.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wójciak-Stothard B, Entwistle A, Garg R, Ridley AJ. Regulation of TNF-alpha-induced reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and cell-cell junctions by Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 in human endothelial cells. Journal of Cell Physiology. 1998;17:150–165. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199807)176:1<150::AID-JCP17>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysolmerski RB, Lagunoff D. Regulation of permeabilized endothelial cell retraction by myosin phosphorylation. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:C32–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.1.C32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee HF., Jr Rho directs activation-associated changes in rat hepatic stellate cell morphology via regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Hepatology. 1998;28:843–850. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280336. 10.1002/hep.510280336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]