Abstract

The giant presynaptic terminal of chick ciliary ganglion was used to examine how protein kinase C (PKC) modulates neurotransmitter release. Cholinergic excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were recorded under whole-cell voltage clamp.

Although the EPSC was potentiated by phorbol ester (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, PMA; 0.1 μm) in a sustained manner, the nicotine-induced current was unaffected. PMA increased the quantal content to 2.4 ± 0.4 (n = 9) of control without changing the quantal size.

The inactive isoform of PMA, 4α-PMA, showed no significant effect on EPSCs. The PMA-induced potentiation was antagonized by two PKC inhibitors with different modes of action, sphingosine (20 μm) and bisindolylmaleimide I (10 μm).

When stimulated by twin pulses of short interval, the second EPSC was on average larger than the first EPSC (paired-pulse facilitation; PPF). PMA significantly decreased the PPF ratio with a time course similar to that of the potentiation of the first EPSC.

PMA did not affect resting [Ca2+]i or the action potential-induced [Ca2+]i increment in the giant presynaptic terminals.

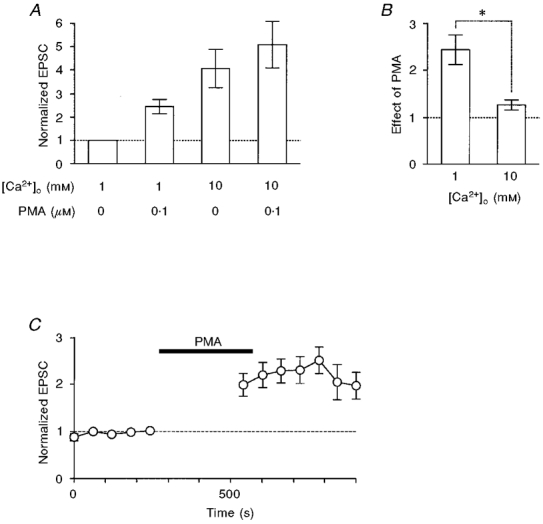

The effect of PMA was less at 10 mm[Ca2+]o than at 1 mm[Ca2+]o.

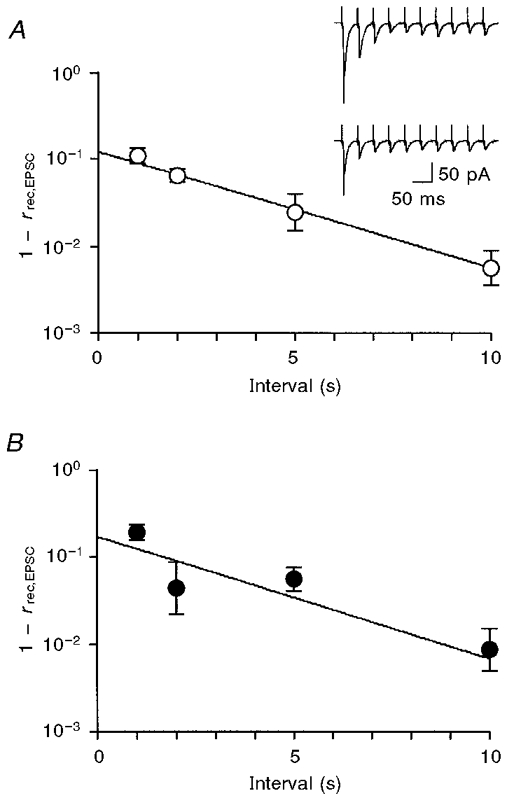

When a train of action potentials was generated with a short interval, the EPSC was eventually depressed and reached a steady-state level. The recovery process followed a simple exponential relation with a rate constant of 0.132 ± 0.029 s−1. PMA did not affect the recovery rate constant of EPSCs from tetanic depression. In addition, PMA did not affect the steady-state EPSC which should be proportional to the refilling rate of the readily releasable pool of vesicles.

These results conflict with the hypothesis that PKC upregulates the size of the readily releasable pool or the number of release sites. PKC appears to upregulate the Ca2+ sensitivity of the process that controls the exocytotic fusion probability.

Protein kinase C (PKC) has been implicated as having pivotal roles in the regulation of signal transduction (Nishizuka, 1992). Activation of PKC has been shown to be involved in the modulation of synaptic transmission by a variety of signals (Tanaka & Nishizuka, 1994). It has been suggested that PKC may enhance synaptic transmission via a presynaptic mechanism. In hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurones, the mossy fibre output is potentiated by phorbol esters in a PKC-dependent manner (Yamamoto et al. 1987; Son & Carpenter, 1996). PKC also potentiates transmitter release from cholinergic nerve terminals of autonomic ganglia and neuromuscular junctions (Minota et al. 1991; Bachoo et al. 1992; Somogyi et al. 1996; Redman et al. 1997). The state- and/or time-dependent facilitation of transmitter release from Aplysia sensory neurones is mediated by PKC (Byrne & Kandel, 1996).

How does PKC potentiate transmitter release from nerve terminals? PKC may increase Ca2+ influx during the action potential either through activation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (Doerner et al. 1990; Schroeder et al. 1990; Swartz, 1993; Zhu & Ikeda, 1994; Stea et al. 1995) or through suppression of K+ channels (Bowlby & Levitan, 1995). This is consistent with the observation that PKC-dependent potentiation is often accompanied by a reduction in paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) (Zalutsky & Nicoll, 1990). Alternatively, PKC may directly modulate the exocytosis of synaptic vesicles downstream of Ca2+ entry (Redman et al. 1997). Phorbol esters increase the frequency of spontaneous miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents in CA3 pyramidal neurones through a Ca2+-independent mechanism (Capogna et al. 1995), whereas in CA1 pyramidal neurones they increase the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) through both Ca2+-dependent and -independent mechanisms (Parfitt & Madison, 1993).

One objective of the present study was to determine whether the PKC-dependent potentiation of nerve-evoked transmitter release is accompanied by an increase in Ca2+ influx in the giant presynaptic terminal of chick ciliary ganglion. To this end, the intraterminal Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) was measured directly (Yawo & Chuhma, 1993, 1994). If PKC activation increases the evoked transmitter release without altering [Ca2+]i, this would indicate that PKC acts on an exocytotic mechanism other than Ca2+ influx, buffering and removal. The results of this paper indicate that this is indeed the case. In order to further elucidate the underlying mechanism of PKC-dependent modulation of exocytosis, the effect of [Ca2+]o on PKC-dependent potentiation, the effect of PKC on the recovery rate of EPSCs from depression after a high frequency train of stimuli, and the correlation between the EPSC potentiation and steady-state EPSC during a train were investigated. The present results exclude the notion that PKC upregulates the size of the readily releasable pool or the number of release sites. It is suggested that PKC upregulates the Ca2+ sensitivity of the process that controls the exocytotic fusion probability.

METHODS

Recordings of excitatory synaptic currents

The methods used here are the same as those described previously (Yawo & Chuhma, 1994). Briefly, chick embryos of day 14 (stage 39-40) were decapitated, and the ciliary ganglion was removed with the oculomotor nerve. The ganglion was superfused with standard saline (mM): NaCl, 132; KCl, 5; CaCl2, 2; MgCl2, 1; Hepes, 10; NaOH, 5; glucose, 11; pH 7.4, adjusted with HCl.

A conventional whole-cell patch clamp recording was made from a postsynaptic ciliary neurone (Yawo & Chuhma, 1994) using an EPC-7 patch clamp amplifier (List Electronic, Darmstadt-Eberstadt, Germany). Patch pipettes were coated with silicon resin (KE106; Shin-Etsu, Tokyo, Japan), and fire polished, reducing the tip diameter to 2 μm. The pipettes had a resistance of 2.5-3 MΩ when filled with internal solution containing (mM): CsCl, 130; MgCl2, 1; Na2EGTA, 10; Hepes, 10; MgATP, 5; pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH. The capacitative transient was minimized by compensating the series conductance and the input capacitance. The series conductance was usually larger than 0.1 μS throughout the experiment and was compensated for by 50-70 %. All the experiments were carried out at room temperature (25°C).

The quantal content (m) was usually calculated from the coefficient of variation (c.v.) based on Poisson statistics (Kuno & Weakly, 1972). When the occurrence of failure transmission was moderate, m calculated from the occurrence of failure was almost identical to that calculated from the c.v. (Yawo & Chuhma, 1994). Therefore, [Ca2+]o and [Mg2+]o were adjusted so that the occurrence of transmission failure was over 10 % of the trials at the beginning of the experiment. Because of the infrequent occurrence of miniature EPSCs, the quantal size (q) was estimated as the mean EPSC divided by m.

Measurement of intraterminal Ca2+ concentration

The method of measuring [Ca2+]i was almost the same as that described previously (Yawo & Chuhma, 1993; Yawo, 1996). The oculomotor nerve was cut at its exit from the orbital bone in Ca2+-free saline containing 1 mM EGTA. Crystals of fura-2-conjugated dextran (fura-dextran, molecular weight 10 000; Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR, USA) were applied to the distal stump. After 30 min of incubation at 10°C, the ganglion was superfused with oxygenated standard saline and incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h. The fluorescence-labelled terminal was focused under the microscope and the Ca2+ concentration was measured by conventional ratiometry (OSP-3; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The signal was integrated for 80 ms and sampled at 12.5 Hz by a computer (PC-9801RS; NEC, Tokyo, Japan) using software for measuring the intracellular [Ca2+] (MiCa; provided by Drs K. Furuya and K. Enomoto, National Institute of Physiological Science, Japan). Twenty records were averaged using the computer-generated stimulating pulse as a trigger.

Reagents

Pharmacological agents were usually bath applied through a perfusion line at a constant flow rate. The solution in the chamber (ca 1 ml) was completely replaced in less than 2 min. Agents used in this study and their sources were as follows: nicotine sulphate (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan); phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma); 4α-phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (4α-PMA; Wako, Osaka, Japan); D-sphingosine (Sigma); bisindolylmaleimide I (BIS; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA). Nicotine was dissolved at a concentration of 10 μM and was puff-applied by a 15 ms pressure pulse from a pipette (tip diameter, 1-2 μm) placed within 10 μm from the recording cell. PMA, 4α-PMA, sphingosine and BIS were dissolved in DMSO, then diluted. The concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1 %, and by itself had no effect on the EPSC.

The values in the text and figures are means ±s.e.m. (number of experiments). Statistically significant differences between various parameters were determined using Student's two-tailed t test, unless specifically noted. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Potentiation of quantal transmitter release by phorbol ester

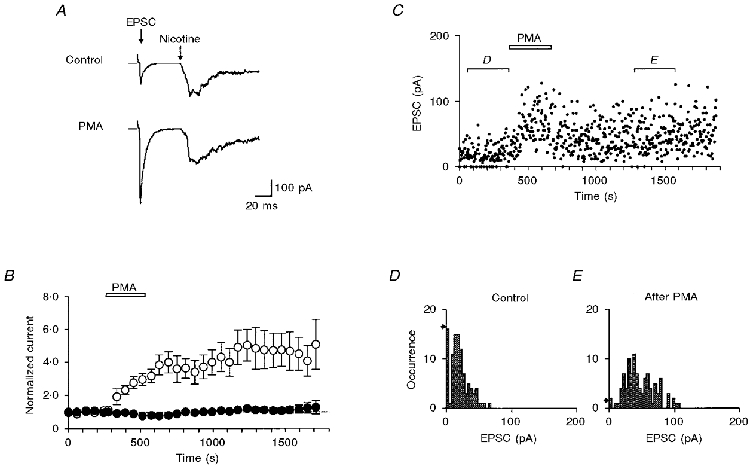

Transmitter release from the giant presynaptic terminal was measured by recording cholinergic EPSCs from the postsynaptic ciliary neurone. The EPSC and the current produced by application of nicotine were recorded sequentially at short intervals (Fig. 1A). Bath application of PMA (0.1 μM) for 5 min potentiated the EPSC amplitude severalfold, an effect that was sustained for 20 min or more after removal of PMA (Fig. 1B), whereas the effects of PMA on the nicotine-induced current were negligible (Fig. 1A and B). For five pairs of experiments, PMA increased the EPSC amplitude to a mean of 3.14 ± 0.39 of its control at the end of 5 min application, yet produced no detectable change in the current evoked by the direct activation of postsynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors (0.82 ± 0.08 of control); this difference was significant (P < 0.01). Occasionally, the EPSC was further potentiated after removal of PMA and distinctly biphasic potentiation was observed in some experiments.

Figure 1. Potentiation of quantal transmitter release by a phorbol ester.

A, simultaneous recordings of the cholinergic postsynaptic current (EPSC) and the nicotine puff-activated current. The oculomotor nerve was stimulated at 0.03 Hz. The top trace is an average of 2 consecutive records just before the application of PMA. The bottom trace is an average of 2 consecutive records 3-4 min after the application of 0.1 μM PMA. B, plots of EPSC (○) and nicotine-induced current (•) against time. Summary of results from 5 experiments similar to those shown in A. Each current was normalized to the mean value before the application of PMA (0.1 μM; open bar). C, time-dependent plots of EPSC amplitudes recorded in a solution containing 0.8 mM Ca2+ and 5 mM Mg2+. PMA (0.1 μM) was perfused during the period indicated. D, EPSC amplitude histogram of 100 consecutive records before the application of PMA, as indicated in C. The quantal content (m) and the quantal size (q) were 1.8 and 10.6 pA, respectively. The arrow on the left indicates the occurrence of failures expected from a Poisson distribution. E, EPSC amplitude histogram of 100 consecutive records after potentiation by PMA, as indicated in C. m and q were 4.1 and 11.2 pA, respectively. The arrow on the left indicates the occurrence of failures expected from a Poisson distribution.

The conclusion that PMA potentiates synaptic transmission presynaptically by increasing the quantal transmitter release was corroborated by an analysis of the fluctuations of the EPSC amplitude recorded in a solution with low Ca2+ and high Mg2+ concentrations (Fig. 1C). Before application of 0.1 μM PMA, presynaptic stimulation frequently did not evoke an EPSC (synaptic failure). The occurrence of failures was 16/100 trials with intervals of 3 s. Figure 1D shows the amplitude distribution of EPSCs, which approximately followed Poisson statistics under these conditions (Martin & Pilar, 1964A; Yawo & Chuhma, 1994). In the control experiment of Fig. 1D, m and q were 1.8 and 10.6 pA, respectively. The expected occurrence of failures was 17/100 trials, which was almost identical to the observed occurrence. In the presence of PMA, no synaptic failures were observed (Fig. 1C). Between 10 and 15 min after removal of PMA, only two failures were observed in 100 trials, while the frequency of the occurrence of large EPSCs was increased (Fig. 1E); m and q were 4.1 and 11.2 pA, respectively. Therefore, PMA increased m of the EPSC to 2.3 of control without changing q. For nine experiments, PMA (0.1 μM) increased m to a mean of 2.4 ± 0.4 of its control. This effect was statistically significant (P < 0.01 between raw data). In contrast, q was 12.9 ± 1.5 pA in the control and 11.8 ± 1.4 pA after potentiation by PMA, the difference being not significant (P > 0.4). Thus, two different technical approaches show that PMA enhances the quantal transmitter release from the presynaptic terminal but has little effect on the sensitivity of the postsynaptic cell to ACh.

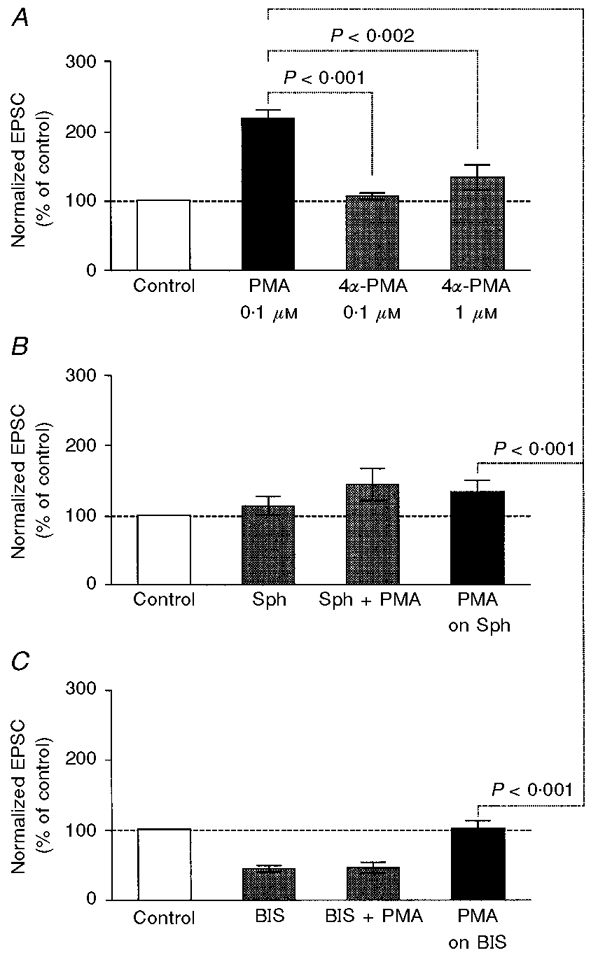

The effects of protein kinase C inhibitors

As summarized in Fig. 2A, the application of 0.1 μM PMA consistently potentiated the EPSC amplitude whereas 4α-PMA, the inactive isoform of PMA, did not at concentrations as high as 1 μM. The possibility that activation of PKC by PMA is the mechanism of EPSC potentiation was tested by investigating the effects of two PKC-selective inhibitors, sphingosine and BIS. Sphingosine selectively inhibits PKC at the C1 domain by competing with diacylglycerol and phorbol esters (Hannun & Bell, 1989). Sphingosine (20 μM) alone potentiated the EPSC in two of seven experiments (to 150-160 % of control). However, on average, the effect was not significant (P > 0.3 between raw data). In the presence of sphingosine, the potentiating effect of PMA was suppressed (P > 0.1; Fig. 2B). BIS is a highly selective cell-permeant PKC inhibitor that is structurally similar to staurosporine and acts as a competitive inhibitor for the kinase domain of PKC (Toullec et al. 1991). BIS (10 μM) alone inhibited the EPSC (to 30-70 % of control; P < 0.01 between raw data). This inhibition was reversible and appeared to be a non-specific inhibition of the postsynaptic ACh receptors because it did not affect the PPF ratio (control, 1.30 ± 0.16; BIS, 1.32 ± 0.18; P > 0.5). In the presence of BIS, the potentiating effect of PMA was completely blocked (P > 0.5; Fig. 2C). Thus, two PKC-selective inhibitors with different modes of action interfered with the PMA-induced potentiation of EPSCs.

Figure 2. Effects of PMA, 4α-PMA and protein kinase C inhibitors.

A, effects of PMA and 4α-PMA on EPSC amplitude. The EPSCs were recorded in a solution containing 1 mM Ca2+ and 1 mM Mg2+. The values were normalized to the mean EPSC amplitude before the application of drugs (Control, □). Other columns show (from left to right): the effects of 0.1 μM PMA (n = 12), 0.1 μM 4α-PMA (n = 7) and 1 μM 4α-PMA (n = 7). Statistical difference is indicated. Note that the effect of 4α-PMA was not significant compared with control (0.1 μM: P > 0.3 between raw data; 1 μM: P > 0.1 between raw data). B, effects of the PKC inhibitor sphingosine (Sph) on PMA-dependent potentiation (n = 7). The EPSCs were recorded in a solution containing 1 mM Ca2+ and 1 mM Mg2+. The columns show (from left to right): control, the effect of 20 μM sphingosine, the simultaneous application of 20 μM sphingosine and 0.1 μM PMA (Sph + PMA) and the effect of 0.1 μM PMA added in the presence of 20 μM sphingosine (PMA on Sph). The effect of PMA was significantly smaller in the presence of sphingosine. The difference between Sph and Sph + PMA was not significant (P > 0.1). C, effects of another PKC inhibitor, bisindolylmaleimide I (BIS), on the PMA-dependent potentiation (n = 7). The EPSCs were recorded in a solution containing 1 mM Ca2+ and 1 mM Mg2+. The columns show (from left to right): control, the effect of 10 μM BIS, the simultaneous application of 10 μM BIS and 0.1 μM PMA (BIS + PMA), and the effect of 0.1 μM PMA added in the presence of 10 μM BIS (PMA on BIS). The effect of PMA was significantly smaller in the presence of BIS. The difference between BIS and BIS + PMA was not significant (P > 0.5).

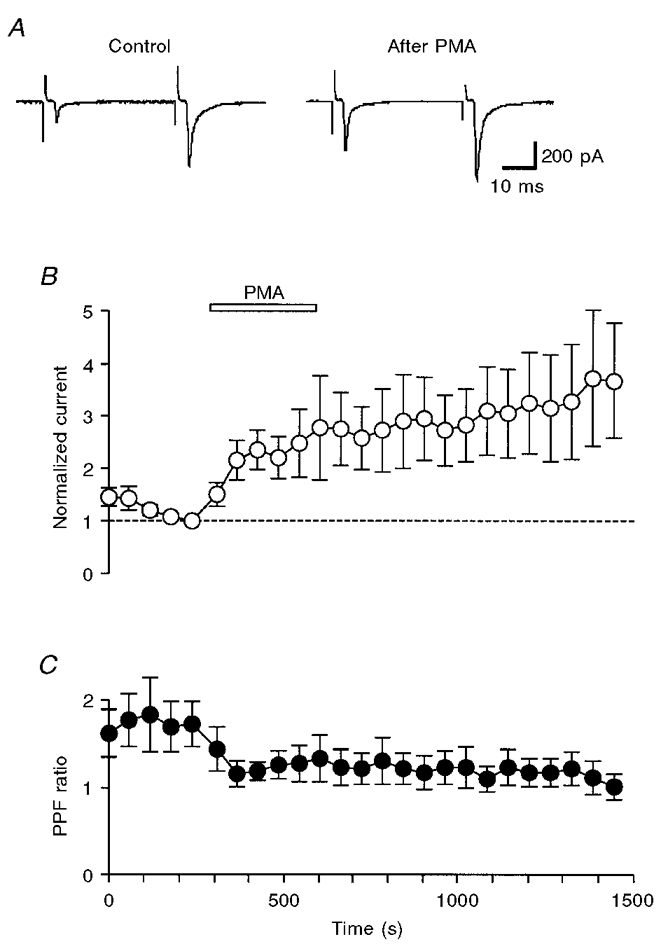

Paired-pulse facilitation

When the presynaptic oculomotor nerve was stimulated by twin pulses at short intervals, the second EPSC was, on average, larger than the first EPSC (Fig. 3A; Martin & Pilar, 1964b). The mechanism of PPF has been attributed to the enhancement of the exocytotic fusion probability as a result of residual Ca2+ in the presynaptic terminal (Katz & Miledi, 1968; Kamiya & Zucker, 1994; Zucker, 1996; Neher, 1998). In the present experiments, the PPF ratio with a pulse interval of 40 ms was 1.72 ± 0.26 (n = 6) when [Ca2+]o and [Mg2+]o were both 1 mM. PPF was accompanied by an increase in m (to 1.7 ± 0.2 of control, n = 6, P < 0.04 between raw data) with no significant change in q (1.0 ± 0.07 of control, n = 6, P > 0.7 between raw data). PMA decreased the PPF ratio to 1.28 ± 0.21 with a time course similar to that of the potentiation of the first EPSC (Fig. 3B and C). Because the size of the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles is limited, manoeuvres that increase the probability of vesicular exocytosis by the first stimulus would deplete the releasable vesicles available for the second EPSC, and thus decrease the PPF ratio (Debanne et al. 1996; Dobrunz & Stevens, 1997; O'Donovan & Rinzel, 1997; Schulz, 1997). PMA might increase the exocytotic fusion probability by increasing the Ca2+ influx during a presynaptic action potential. Alternatively, PMA could increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of the exocytotic fusion probability.

Figure 3. Effects of PMA on paired pulse facilitation.

A, each trace is the average of 10 consecutive paired EPSCs before (left) and after (right) the application of 0.1 μM PMA. EPSCs were recorded in a solution containing 1 mM Ca2+ and 1 mM Mg2+. The oculomotor nerve was stimulated at 0.167 Hz by twin pulses with an interval of 40 ms. B, plots of the first EPSC amplitude (○) against time (n = 6). Each current was normalized to the value just before the application of PMA (0.1 μM; open bar). C, second EPSC/first EPSC ratio (paired-pulse facilitation ratio, PPF ratio, •) for the data shown in B. The PPF ratio decreased significantly after the application of PMA (P < 0.05).

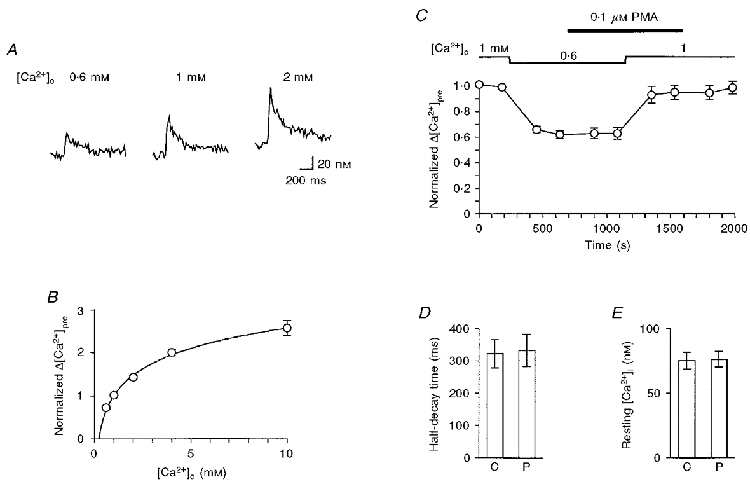

Presynaptic Ca2+ influx

To determine whether PMA potentiates the transmitter release by increasing Ca2+ influx in the presynaptic terminal, [Ca2+]i transients were measured. Upon invasion by a single presynaptic action potential, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels are activated, leading to an increase in [Ca2+]i. Figure 4A shows sample records of the [Ca2+]i transient at various [Ca2+]o. Although [Ca2+]i transients should be much larger and faster in the vicinity of Ca2+ channel clusters (Zucker, 1996; Neher, 1998), the fluorescence of fura-dextran would represent an average of residual [Ca2+]i in a space not far from the Ca2+ channel clusters. This notion was confirmed by examining the dependency of the [Ca2+]i increment on [Ca2+]o (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, the action potential-dependent increment in [Ca2+]i (Δ[Ca2+]pre) was non-linearly dependent on [Ca2+]o; the slope of peak Δ[Ca2+]pre to [Ca2+]o was steeper at low [Ca2+]o than at high [Ca2+]o.

Figure 4. Effects of PMA on presynaptic Ca2+ dynamics.

A, sample records of the intraterminal Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) changes at a [Ca2+]o of 0.6 mM (left), 1 mM (middle) and 2 mM (right) following a single electrical stimulation applied to the oculomotor nerve (stimulation frequency, 0.125 Hz). B, [Ca2+]o dependence of the action potential-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i. Data from 7 experiments are summarized after normalizing the action potential-dependent increment in [Ca2+]i (Δ[Ca2+]pre) to the value at [Ca2+]o = 1 mM. The line was drawn according to the least-squares fit to the empirical equation: Δ[Ca2+]pre = a ln([Ca2+]o) + 1, where a = 0.68. Note that error bars are hidden behind the plotted circles. C, Δ[Ca2+]pre was normalized to the mean value at 1 mM [Ca2+]o before the application of PMA, and plotted against time (n = 5). [Ca2+]o was initially 1 mM, then changed to 0.6 mM and returned to 1 mM again as indicated. PMA (0.1 μM) was perfused during the period indicated by the filled bar. D, the half-decay time of the action potential-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i. Summary of 12 similar experiments in control (C) and in the presence of 0.1 μM PMA (P). The difference was not significant (P > 0.8). E, resting [Ca2+]i. Summary of 9 similar experiments in control (C) and in the presence of 0.1 μM PMA (P). The difference was not significant (P > 0.5).

Because the slope of Δ[Ca2+]pre to [Ca2+]o was steepest between 0.6 and 1 mM, the effects of PMA on Δ[Ca2+]pre were examined by the protocol shown in Fig. 4C. When [Ca2+]o was changed from 1 to 0.6 mM, Δ[Ca2+]pre decreased to about 60 % of control. By decreasing [Ca2+]o from 1 to 0.6 mM, the EPSC was reduced to 0.23 ± 0.02 of control (n = 8, P < 0.001 between raw data). The EPSC at 0.6 mM [Ca2+]o was potentiated by PMA to 1.97 ± 0.15 (n = 8, P < 0.001 between raw data) of control. Therefore, if PMA increases the exocytotic fusion probability by increasing the Ca2+ influx during a presynaptic action potential, Δ[Ca2+]pre can be expected to increase to a value between those at 0.6 and 1 mM [Ca2+]o. However, the addition of 0.1 μM PMA had no effect on Δ[Ca2+]pre. When [Ca2+]o returned to 1 mM, the effects of PMA on Δ[Ca2+]pre were also negligible. [Ca2+]i decayed to the baseline with a half-decay time of 322 ± 44 ms (n = 12), which was not affected by PMA (Fig. 4D). The effect of PMA on the resting [Ca2+]i was also negligible (Fig. 4E). Therefore, the PMA-induced potentiation was accompanied by no detectable changes in net Ca2+ influx, buffering or removal.

Ca2+ dependency of PMA-induced potentiation

The transmitter release mechanism consists of several steps (Burgoyne & Morgan, 1995; Calakos & Scheller, 1996), some of which are dependent on intracellular Ca2+. In order to elucidate the intracellular mechanism of potentiation, the Ca2+ sensitivity of transmitter release was investigated. As observed for other synapses (Dodge & Rahamimoff, 1967), the EPSC amplitude in chick ciliary ganglion was a non-linear function of [Ca2+]o, eventually saturating at high concentrations (Yawo & Chuhma, 1994; Yawo, 1996). This can be attributed to the saturation of Ca2+-sensing molecules for transmitter release at high [Ca2+]i (Dodge & Rahamimoff, 1967). Therefore, if the effects of PKC on exocytosis involve a Ca2+-dependent mechanism, it would be expected that, at high [Ca2+]o, the PMA-induced potentiation would be less than that at low [Ca2+]o (Yawo, 1996).

When [Ca2+]o was ≤ 1 mM, 0.1 μM PMA consistently potentiated the EPSC (range, to 1.43-6.53 of control; n = 26), e.g. the magnitude of potentiation was 2.43 ± 0.31 (n = 14) at 1 mM [Ca2+]o (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, at 10 mM [Ca2+]o, the magnitude of potentiation was only 1.27 ± 0.11 (n = 7; Fig. 5A and B), which was significantly less than that at 1 mM [Ca2+]o (P < 0.004; Fig. 5B). This suggests that PMA modulates the transmitter release predominantly by enhancing [Ca2+]i-dependent mechanisms.

Figure 5. Ca2+ dependency of PMA-induced potentiation.

A, the PMA-induced potentiation of EPSCs was dependent on [Ca2+]o. EPSC amplitudes were normalized to the value at 1 mM [Ca2+]o without PMA. The columns represent (from left to right): control at 1 mM [Ca2+]o (n = 14), 0.1 μM PMA at 1 mM [Ca2+]o (n = 14), 10 mM [Ca2+]o without PMA (n = 7), and 0.1 μM PMA at 10 mM [Ca2+]o (n = 7). B, comparison of the effect of 0.1 μM PMA at 1 mM [Ca2+]o (left column, same as the second column in A) and 10 mM [Ca2+]o (n = 7; right column). The asterisk indicates that the difference was significant (P < 0.004). The effect of PMA was not significant at 10 mM [Ca2+]o (P > 0.07 between raw data). C, investigation of whether the residual[Ca2+]i increase by previous stimuli is a prerequisite for the PMA-induced potentiation. The experiments were similar to those in Figs 1 and 2, but the presynaptic terminal was not stimulated for 5 min during the application of 0.1 μM PMA. Time plots of EPSCs evoked at 1 min intervals in a solution containing 1 mM Ca2+ and 1 mM Mg2+ (n = 6). Currents were normalized to the value just before the application of PMA (0.1 μM; filled bar).

The following two possibilities must then be resolved. (1) PMA might enhance the exocytotic fusion probability of docked/primed vesicles, which is regulated by instantaneous[Ca2+]i dynamics, or (2) PMA might enlarge the size of the readily releasable pool of vesicles or increase the number of release sites through residual[Ca2+]i-dependent mechanisms. These possibilities can be discriminated by examining whether the first EPSC was potentiated after 5 min without stimulation during the application of PMA. If the residual[Ca2+]i-dependent mechanisms are upregulated by PKC, the effects of PMA should be negligible for the EPSC evoked by the first stimulus after the long rest period. As shown in Fig. 5C, PMA potentiated the first EPSC by 1.26-2.84 of control (n = 6), values comparable to those observed when the stimulation was not interrupted. This means that PKC mainly upregulates an exocytotic mechanism tightly coupled with the increase in instantaneous[Ca2+]i.

Analysis of recovery rate

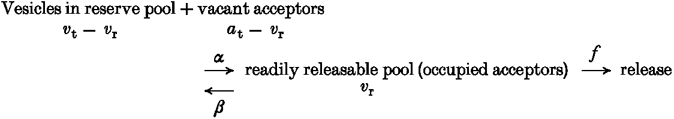

According to the vesicle hypothesis, depolarization of the nerve terminal activates voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, leading to a local increase in [Ca2+]i which triggers the exocytosis of synaptic vesicles (Augustine et al. 1987). The release probability at a release site is dependent on the product of the number of docked/primed vesicles which are readily releasable (readily releasable pool) and the fusion probability (Rosenmund & Stevens, 1996). Therefore, one can assume that the number of vesicles released from a giant presynaptic terminal by an action potential, m, can be expressed by the following equation:

| (1) |

where vr is the sum of the readily releasable pool for all release sites at the synapse and f represents the average fusion probability of vesicles. The size of the readily releasable pool of vesicles should be regulated by a balance between vacant and occupied acceptors which dock vesicles to their release sites (Scheme 1) (see Maeno, 1969). In Scheme 1, vt and at are the total number of vesicles and acceptors, respectively, and α and β are rate constants as indicated. Scheme 1 gives the following relation, provided that one vesicle would bind to only one acceptor:

| (2) |

Since the size of the readily releasable pool of vesicles is very small compared with the total number of vesicles (Neher, 1998), (vt - vr) could be replaced by vt. Because spontaneous transmitter release is very infrequent from the calyx-shaped terminal of chick ciliary ganglion, f should be zero during the resting period between nerve stimuli. Under these assumptions, vr can be expressed by the following simple equation:

| (3) |

where

| (4) |

Scheme 1.

Therefore, the recovery ratio of the readily releasable pool at time t from the last stimulus, rrec(t) = vr(t)/vr(∞), follows the relation:

| (5) |

The presynaptic oculomotor nerve was stimulated with a train of ten pulses at 25 Hz, and the recovery ratio of the first EPSC (EPSC1) in a train, rrec,EPSC, was measured after a certain interval of 1, 2, 5 or 10 s (Fig. 6A, inset). Provided that the vesicle fusion probability is the same for each EPSC1 in a train, the recovery ratio of EPSC, rrec,EPSC, can be expected to follow eqn (5). Actually, as shown in Fig. 6A, (1 - rrec,EPSC) declined exponentially with time after each train with a slope of 0.132 ± 0.029 s−1 (n = 10), which should be equivalent to the denominator of eqn (4), (αvt+β).

Figure 6. Effects of PMA on the recovery rate of EPSCs from tetanic exhaustion of the readily releasable pool of vesicles.

If PMA increases vr by reducing the dissociation rate of the acceptor-vesicle complex (β), the EPSC would be expected to recover more slowly after the PMA-induced potentiation. On the other hand, if PMA increases vr by enhancing the acceptor-vesicle association rate, α, the EPSC would be expected to recover more rapidly after the PMA-induced potentiation. Again, (1 - rrec,EPSC) decreased exponentially with time after PMA-induced potentiation (Fig. 6B). Although PMA potentiated the EPSC by 1.92 ± 0.31 (n = 6), the slope was 0.141 ± 0.032 s−1 (n = 6), which was the same as the control (P > 0.8). Since PMA did not affect the steady-state EPSC (EPSCss; see later section), no evidence was obtained that PMA increases vr by either reducing β or enhancing α.

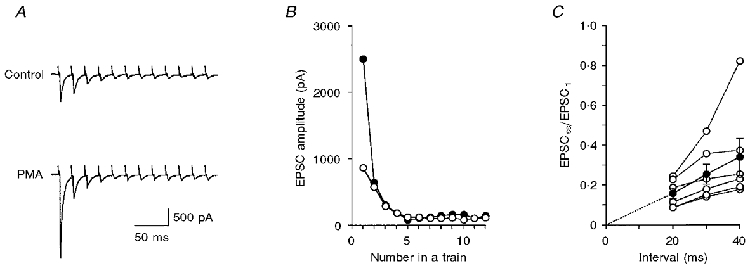

Analysis of synaptic depression

At any particular synapse, the effects of prior stimulation on the postsynaptic response depend on a balance between facilitation and depression. When a train of stimulating pulses was applied to the oculomotor nerve at short intervals, the EPSC was eventually depressed and reached a steady-state level (Figs 6A, inset, and 7A and B). Since f should be zero during the pulse interval (Δt) and vr should be very small compared with vt and at at steady state, eqn (2) could be rewritten as:

| (6) |

Figure 7. PMA induced a potentiation of the first EPSC (EPSC1) in a train but had no effect on the steady-state EPSC (EPSCss).

A, average of 5 consecutive records of EPSCs in response to a train of 12 pulses at 50 Hz during the control period (top trace) and after potentiation by 0.1 μM PMA (bottom trace). B, EPSC amplitudes in A were measured from the current immediately before the onset of the EPSC to the peak of the EPSC, and plotted against the pulse number in a train, during the control period (○) and after potentiation by PMA (•). The mean amplitude of the last 4 EPSCs was adopted as EPSCss. C, relation between normalized EPSCss (EPSCss/EPSC1) and the interpulse interval. Filled circles and error bars summarize the mean ±s.e.m. of 6 similar experiments (open circles).

At the steady state the number of released vesicles should be balanced by the number of vesicles added to the readily releasable pool during Δt (Markram & Tsodyks, 1996). EPSCss should thus be proportional to the numerator of eqn (4) (Tsodyks & Markram, 1997; O'Donovan & Rinzel, 1997):

| (7) |

where qss is the quantal size at steady state.

Figure 7C shows the experimental results with variable Δt between 20 and 40 ms. Since the EPSCss was consistently proportional to Δt, particularly between 20 and 30 ms, the slope at 20 ms was used as the estimate of qssαvtat. If the transmitter release is potentiated through a mechanism which increases α, the EPSCss would be expected to be enhanced. The effects on the EPSC of increasing [Ca2+]o from 2 to 4 mM were tested. Although the first EPSC in a train (EPSC1) was potentiated to 2.38 ± 0.36 of control (n = 7, P < 0.02 between raw data), the change in EPSCss was negligible (1.15 ± 0.11, P > 0.3 between raw data). This is consistent with the notion that increasing [Ca2+]o would enhance the fusion probability with little change in the size of the readily releasable pool of vesicles.

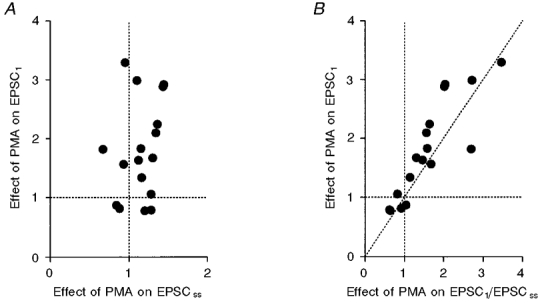

Figure 7A shows a sample record where EPSC1 was potentiated by PMA (0.1 μM). As was the case after increasing [Ca2+]o, EPSCss was not potentiated by PMA (Fig. 7B). Figure 8A is a summary of 17 similar experiments where the potentiation of EPSC1 was plotted against the effect of PMA on EPSCss. There was no apparent correlation between these values (correlation coefficient = 0.24). When the potentiation of EPSC1 was compared between the group in which the effect of PMA on EPSCss was less than control and the group in which the effect of PMA on EPSCss was greater than control, the difference was not significant (P > 0.7; 1.67 ± 0.40, n = 5, for the former group vs. 1.85 ± 0.22, n = 12, for the latter group). In four of 17 experiments, EPSC1 increased during washout of PMA whereas EPSCss decreased.

Figure 8. Effects of PMA on EPSC1 and EPSCss and their comparison.

A, correlation between the PMA-induced potentiation of EPSC1 and the change in EPSCss. The correlation coefficient was 0.24 (n = 17). B, re-plot of the data in A against the PMA-dependent change in EPSC1/EPSCss. The correlation coefficient was 0.87.

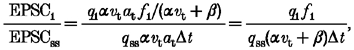

From eqn (4) the value EPSC1/EPSCss would be expressed by the following equation:

|

(8) |

where q1 is the quantal size of EPSC1, and f1 is the fusion probability for EPSC1. The effect of PMA on f1 should be proportional to that on EPSC1/EPSCss, because the effects of PMA were negligible on the quantal size and (αvt+β). Figure 8B shows a plot of the potentiation of EPSC1 against the potentiation of EPSC1/EPSCss. As expected from Fig. 8A, a good correlation was observed between these values (correlation coefficient = 0.87, n = 17). When the potentiation of EPSC1 was compared between the group in which the effect of PMA on EPSC1/EPSCss was < 1.0 and the group in which EPSC1/EPSCss was > 1.0, the difference was significant (P < 0.001; 0.86 ± 0.06, n = 4, for the former group vs. 2.09 ± 0.20, n = 13, for the latter group). Since PMA did not influence either the numerator, αvtat, or the denominator, (αvt+β), of eqn (4), the results of Fig. 8 strongly suggest that the PMA-induced potentiation of EPSC1 was caused by the increase in f1 rather than by the increase in vr.

DISCUSSION

Potentiation of transmitter release by activation of PKC

The data presented here show that a phorbol ester, PMA, potentiated the EPSC with little effect on the postsynaptic nicotinic ACh receptors. PMA increased m without changing q of the quantal transmitter release. The effect of PMA was not mimicked by 4α-PMA, an inactive isoform of PMA, and was blocked by two PKC inhibitors of different mechanisms of action, sphingosine and BIS. These results indicate that PKC activation potentiates the transmitter release from the giant presynaptic terminal of chick ciliary ganglion, as at other synapses of central and peripheral nervous systems (Yamamoto et al. 1987; Bachoo et al. 1992; Somogyi et al. 1996; Son & Carpenter, 1996; Redman et al. 1997). Since BIS is ineffective on MUNC-13, another phorbol ester receptor (Betz et al. 1998), the PKC-dependent phosphorylation should be the main mechanism of the potentiation.

Is the Ca2+ influx modulated by PKC?

In the present study, as shown in Fig. 4C, Δ[Ca2+]pre was unchanged by PMA. The results thus exclude the possibility that PKC upregulates Ca2+ channels or downregulates K+ channels. It is suggested that PMA directly modulates the exocytotic machinery. A similar conclusion was made concerning the frog neuromuscular junction (Redman et al. 1997) and rat hippocampal synapses (Capogna et al. 1995).

PKC upregulates N-type Ca2+ channels in many central and peripheral neurones (Swartz, 1993; Yang & Tsien, 1993; Zhu & Ikeda, 1994). The I-II cytoplasmic linkage of the α1B subunit of N-type Ca2+ channels is a prerequisite for the action of PKC (Stea et al. 1995). The Ca2+ channels in the giant presynaptic terminal of chick ciliary ganglion are mostly ω-conotoxin GVIA sensitive (N-type; Yawo & Momiyama, 1993). It is unclear why these N-type Ca2+ channels were insensitive to PKC.

Mechanism of PKC-dependent potentiation

Equation (1) predicts two modulation sites for transmitter release in a given presynaptic terminal: the sum of the readily releasable pool for all release sites and the exocytotic fusion probability. The results of the present study showed first that the PMA-induced potentiation of transmitter release was dependent on [Ca2+]o and that no significant potentiation was observed at 10 mM (Fig. 5A and B). Second, the PMA-induced potentiation was not dependent on the preceding increase in residual[Ca2+]i (Fig. 5C). Therefore, it is unlikely that PMA would upregulate either the instantaneous[Ca2+]i-independent or the residual[Ca2+]i-dependent mechanisms that regulate the number of release sites or the size of the readily releasable pool of vesicles.

Since vr might be regulated by a balance between the association and dissociation of the acceptor-vesicle complex, the effects of PMA on the acceptor-vesicle association rate, α, and the acceptor-vesicle dissociation rate, β, were studied. However, the recovery rate of the EPSC was not affected by PMA (Fig. 6B), and the PMA-induced potentiation of EPSC1 was observed without potentiation of EPSCss (Fig. 8A). In summary, no evidence was observed that implies the upregulation of α or the downregulation of β in the present preparation. This is consistent with the above notion that PMA would upregulate a mechanism other than vr. The result in Fig. 8A also excludes the possibility that PMA would upregulate at. On the other hand, the PMA-induced potentiation of EPSC1 was accompanied by the potentiation of EPSC1/EPSCss, which would be proportional to f1 (eqn (8) and Fig. 8B). The results of the PPF experiments (Fig. 3) are consistent with the notion that PKC activation enhances the Ca2+ sensitivity of f since it does not increase the Ca2+ influx.

These results were all in conflict with the notion that PKC upregulates the number of release sites or the size of the readily releasable pool of vesicles. Instead, PKC appears to increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of f through either upregulating the Ca2+ sensitivity of the Ca2+-sensor molecule, increasing the local [Ca2+]i in the vicinity of the Ca2+ sensor, or upregulating the linkage between the Ca2+ sensor and the fusion machinery. This conclusion is in contrast to that from studies of the adrenal chromaffin cell in which the size of the releasable pool of secretory granules is upregulated by PMA (Gillis et al. 1996), but rather is consistent with the observation that phorbol ester upregulates the Ca2+ sensitivity of catecholamine secretion from adrenal medullary cells (Knight & Baker, 1983). At the frog neuromuscular junction, the maximum synaptic potential at high [Ca2+]o was also potentiated by phorbol ester (Redman et al. 1997), suggesting the upregulation of vr.

The rate-limiting sites of transmitter release

Neurotransmitter release is composed of a complex of biochemical reactions that are triggered by Ca2+ influx. In the chick ciliary giant presynaptic terminal, the N-type Ca2+ channel might be the molecule involved in one of the rate-limiting steps, and it is modulated by presynaptic receptors, including A1 adenosine autoreceptors (Yawo & Chuhma, 1993), μ-opioid receptors (H. Yawo & K. Endo, unpublished observation) and α2-adrenergic receptors (Yawo, 1996). That is, at least three receptors convergently regulate the N-type Ca2+ channel. These responses are thought to depend on the membrane-delimited action of G-proteins, and are all rapid and readily reversible. Similar mechanisms work for other Ca2+ channel subtypes at various synapses (Umemiya & Berger, 1994; Takahashi et al. 1996; Wu & Saggau, 1997). Another candidate for the rate-limiting step could be the Ca2+ sensitivity of f, e.g. the mechanism of noradrenaline-dependent potentiation in chick ciliary presynaptic terminals (Yawo, 1996). The same mechanism appears to be the target of PKC in the present study. Both mechanisms are suggested to be dependent on the phosphorylation of molecules involved in the exocytotic machinery (for noradrenaline: H. Yawo, unpublished observation), and the effects are sustained. Differential modulation of these two sites, the Ca2+ channel and the Ca2+ sensitivity of f, would enable the fine manipulation of the efficacy of transmitter release.

Acknowledgments

I thank S. Sai for technical support, Drs T. Abe, K. Kawa and M. Umemiya for comments on the manuscript and Mr B. Bell for reading the revised manuscript. Reviews by Drs E. M. McLachlan and K. Kuba are gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan, the Yamanouchi Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders and the Gonryou Medical Foundation.

References

- Augustine GJ, Charlton MP, Smith SJ. Calcium action in synaptic transmitter release. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1987;10:633–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.10.030187.003221. 10.1146/annurev.ne.10.030187.003221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachoo M, Heppner T, Fiekers J, Polosa C. A role for protein kinase C in long term potentiation of nicotinic transmission in the superior cervical ganglion of the rat. Brain Research. 1992;585:299–302. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz A, Ashery U, Rickmann M, Augustin I, Neher E, Südhof TC, Rettig J, Brose N. Munc13–1 is a presynaptic phorbol ester receptor that enhances neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;21:123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby MR, Levitan IB. Block of cloned voltage-gated potassium channels by the second messenger diacylglycerol independent of protein kinase C. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;73:2221–2229. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.6.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD, Morgan A. Ca2+ and secretory-vesicle dynamics. Trends in Neurosciences. 1995;18:191–196. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93900-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne JH, Kandel ER. Presynaptic facilitation revised: state and time dependence. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;15:425–435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00425.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calakos N, Scheller RH. Synaptic vesicle biogenesis, docking, and fusion: a molecular description. Physiological Reviews. 1996;76:1–29. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Presynaptic enhancement of inhibitory synaptic transmission by protein kinases A and C in the rat hippocampus in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:1249–1260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01249.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Guérineau NC, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Paired-pulse facilitation and depression at unitary synapses in rat hippocampus: quantal fluctuation affects subsequent release. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;491:163–176. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrunz LE, Stevens CF. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron. 1997;18:995–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80338-4. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge FA, Jr, Rahamimoff R. Co-operative action of calcium ions in transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. The Journal of Physiology. 1967;193:419–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerner D, Abdel-Latif M, Rogers TB, Alger BE. Protein kinase C-dependent and -independent effects of phorbol esters on hippocampal calcium current. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:1699–1706. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-05-01699.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis KD, Mössner R, Neher E. Protein kinase C enhances exocytosis from chromaffin cells by increasing the size of the readily releasable pool of secretory granules. Neuron. 1996;16:1209–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80147-6. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannun YA, Bell RM. Functions of sphingolipids and sphingolipid breakdown products in cellular regulation. Science. 1989;243:500–507. doi: 10.1126/science.2643164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Zucker RS. Residual Ca2+ and short-term synaptic plasticity. Nature. 1994;371:603–606. doi: 10.1038/371603a0. 10.1038/371603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. The role of calcium in neuromuscular facilitation. The Journal of Physiology. 1968;195:481–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DE, Baker PF. The phorbol ester TPA increases the affinity of exocytosis for calcium in ‘leaky’ adrenal medullary cells. FEBS Letters. 1983;160:98–100. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80944-2. 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80944-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno M, Weakly JN. Quantal components of the inhibitory synaptic potential in spinal motoneurones of the cat. The Journal of Physiology. 1972;224:287–303. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeno T. Analysis of mobilization and demobilization processes in neuromuscular transmission in the frog. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1969;32:793–800. doi: 10.1152/jn.1969.32.5.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Tsodyks M. Redistribution of synaptic efficacy between neocortical pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1996;382:807–810. doi: 10.1038/382807a0. 10.1038/382807a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AR, Pilar G. Quantal components of the synaptic potential in the ciliary ganglion of the chick. The Journal of Physiology. 1964a;175:1–16. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AR, Pilar G. Presynaptic and postsynaptic events during post-tetanic potentiation and facilitation in the avian ciliary ganglion. The Journal of Physiology. 1964b;175:17–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minota S, Kumamoto E, Kitakoga O, Kuba K. Long-term potentiation induced by a sustained rise in the intraterminal Ca2+ in bull-frog sympathetic ganglia. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;435:421–438. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: new tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80983-6. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donovan MJ, Rinzel J. Synaptic depression: a dynamic regulation of synaptic communication with varied functional roles. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:431–433. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01124-7. 10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt KD, Madison DV. Phorbol esters enhance synaptic transmission by a presynaptic, calcium-dependent mechanism in rat hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;471:245–268. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman RS, Searl TJ, Hirsh JK, Silinsky EM. Opposing effects of phorbol esters on transmitter release and calcium currents at frog motor nerve endings. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;501:41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.041bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Stevens CF. Definition of the readily releasable pool of vesicles at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80146-4. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JE, Fischbach PS, McCleskey EW. T-type calcium channels: heterogeneous expression in rat sensory neurons and selective modulation by phorbol esters. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:947–951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-03-00947.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz PE. Long-term potentiation involves increases in the probability of neurotransmitter release. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:5888–5893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5888. 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi GT, Tanowitz M, Zernova G, de Groat WC. M1 muscarinic receptor-induced facilitation of ACh and noradrenaline release in the rat bladder is mediated by protein kinase C. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:245–254. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son H, Carpenter DO. Protein kinase C activation is necessary but not sufficient for induction of long-term potentiation at the synapse of mossy fiber-CA3 in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1996;72:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00532-3. 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea A, Soong TW, Snutch TP. Determinants of PKC-dependent modulation of a family of neuronal calcium channels. Neuron. 1995;15:929–940. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90183-3. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz KJ. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by protein kinase C in rat central and peripheral neurons: disruption of G protein-mediated inhibition. Neuron. 1993;11:305–320. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90186-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Onodera K. Presynaptic calcium current modulation by a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Science. 1996;274:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.594. 10.1126/science.274.5287.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka C, Nishizuka Y. The protein kinase C family for neuronal signaling. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1994;17:551–567. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003003. 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toullec D, Pianetti P, Coste H, Bellevergue P, Grand-Perret T, Ajakane M, Baudet V, Boissin P, Boursier E, Loriolle F, Duhamel L, Charon D, Kirilovsky J. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:15771–15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsodyks MV, Markram H. The neural code between neocortical pyramidal neurons depends on neurotransmitter release probability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:719–723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.719. 10.1073/pnas.94.2.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemiya M, Berger AJ. Activation of adenosine A1 and A2 receptors differentially modulates calcium channels and glycinergic synaptic transmission in rat brainstem. Neuron. 1994;13:1439–1446. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90429-4. 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-G, Saggau P. Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01015-6. 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)01015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto C, Higashima M, Sawada S. Quantal analysis of potentiating action of phorbol ester on synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Neuroscience Research. 1987;5:28–38. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(87)90021-6. 10.1016/0168-0102(87)90021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Tsien RW. Enhancement of N- and L-type calcium channel currents by protein kinase C in frog sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1993;10:127–136. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90305-b. 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90305-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawo H. Noradrenaline modulates transmitter release by enhancing the Ca2+ sensitivity of exocytosis in the chick ciliary presynaptic terminal. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;493:385–391. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawo H, Chuhma N. Preferential inhibition of ω-conotoxin-sensitive presynaptic Ca2+ channels by adenosine autoreceptors. Nature. 1993;365:256–258. doi: 10.1038/365256a0. 10.1038/365256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawo H, Chuhma N. ω-Conotoxin-sensitive and -resistant transmitter release from the chick ciliary presynaptic terminal. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;477:437–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawo H, Momiyama A. Re-evaluation of calcium currents in pre- and postsynaptic neurons of the chick ciliary ganglion. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;460:153–172. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. Comparison of two forms of long-term potentiation in single hippocampal neurons. Science. 1990;248:1619–1624. doi: 10.1126/science.2114039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Ikeda SR. Modulation of Ca2+-channel currents by protein kinase C in adult rat sympathetic neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72:1549–1560. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS. Exocytosis: a molecular and physiological perspective. Neuron. 1996;17:1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80238-x. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80238-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]