Abstract

The effect of 5 μm 4-chloro-m-cresol (4-CmC) on voltage-controlled Ca2+ release was studied in cut muscle fibres of the frog loaded with internal solutions containing 15 mM EGTA. Fibres were voltage clamped using a double Vaseline gap system, and Ca2+ signals were recorded with the fluorescent indicator dye fura-2

Resting intracellular free Ca2+ concentration increased from 61 to 100 nm upon application of 4-CmC.

Both peak rate of release of intracellularly stored Ca2+ and the steady level attained after 50 ms of depolarization increased, but the potentiation of the latter was more pronounced (by a factor of 1.7 versus 1.3). The voltage of half-maximal activation remained unchanged.

Non-linear intramembranous charge movements showed no significant change in voltage dependence while the maximal charge displaced by depolarization increased by 25%.

The dependence of peak release flux on total intramembranous charge was not different in 4-CmC, but for the steady level of release the steepness of the relation increased by a factor of 1.3.

The stimulating effect of 5 μm 4-CmC on depolarization-induced Ca2+ release resembled the potentiation by 0.5 mm caffeine. However, 0.5 mm caffeine increased the peak and steady levels of the release rate by a similar factor and caused no increase in the resting free calcium concentration, indicating different modes of action of the two substances.

Neither 5 μm 4-CmC nor 0.5 mm caffeine led to a loss of voltage control of Ca2+ release during repolarization after short depolarizations, as has been reported previously for caffeine. Potentiated Ca2+ release could be terminated by repolarization as fast as under control conditions both with 15 mm and 0.1 mm internal EGTA.

The effects of 4-CmC may result from a direct opening of the release channel combined with an enhancement of the transduction mechanism that couples channel opening to displacement of voltage sensor charges.

Various agents are known to stimulate Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) in muscle, the best characterized and most frequently used being the methylxanthine drug caffeine (Herrmann-Frank et al. 1999). Caffeine causes Ca2+ release (Shirokova & Rios, 1996a) and corresponding contractures (Lüttgau & Oetliker, 1968) at concentrations in the millimolar range. 4-Chloro-m-cresol (4-CmC), a substance occasionally added as a preservative to drugs, has been reported to cause skeletal muscle contractures at considerably lower concentrations than caffeine (Herrmann-Frank et al. 1996b;Tegazzin et al. 1996). As an additive to preparations of the depolarizing muscle relaxant succinylcholine, 4-CmC has even been implicated (Tegazzin et al. 1996) in triggering malignant hyperthermia (MH), a state of muscle hypermetabolism originating from pathologically increased Ca2+ release in susceptible individuals (MacLennan & Phillips, 1992; Mickelson & Louis, 1996). Like caffeine, 4-CmC can be used on muscle biopsies to distinguish between normal and MH muscle (Herrmann-Frank et al. 1996a,b; Tegazzin et al. 1996). In the latter, the threshold concentration for inducing a contracture is lowered for both drugs. As in the case of caffeine, the action of 4-CmC could be traced to a direct effect on the Ca2+ release channel. Both ryanodine binding and unitary current fluctuations of isolated ryanodine receptors were enhanced by 4-CmC (Herrmann-Frank et al. 1996a,b). The half-maximally activating concentration for ryanodine binding was about 400 μM whereas it was more than 10 mM for caffeine (Herrmann-Frank et al. 1996a).

Caffeine is known to potentiate voltage-controlled Ca2+ release at concentrations below the threshold for inducing a contracture (Lüttgau & Oetliker, 1968; Kovacs & Szücs, 1983; Delay et al. 1986; Konishi & Kurihara, 1987; Simon et al. 1989; Klein et al. 1990). The goal of the present study was to investigate potentiation of excitation-contraction coupling by 4-CmC. For this purpose we studied its effect on depolarization-triggered Ca2+ release and voltage sensor charge movements in cut muscle fibres of the frog.

METHODS

Preparation and solutions

Frogs (R. pipiens) were killed by decapitation, and the brain and spinal cord were rapidly destroyed. The procedures were approved by the university's animal welfare committee. Segments of single muscle fibres were dissected in relaxing solution (see below). The fibre segments were mounted in a double Vaseline gap chamber on a glass coverslip and voltage-clamped as previously described (Kovacs et al. 1983; Feldmeyer et al. 1990).

The following solutions were used for fibre dissection and mounting (relaxing solution) and during the experiment in the external and internal chamber pools, respectively (values in mM).

Relaxing solution:

glutamic acid, 120; tris(hydroximethyl)aminomethane maleate (tris-maleate), 5; EGTA, 0.01; MgCl2, 2; NaOH, 5; pH adjusted with KOH to 7.0.

External solution:

CH3SO3H, 140; Ca(OH)2, 2; Hepes, 2; 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), 2; TTX added at 10−7 g ml−1; pH adjusted with TEA-OH to 7.4.

Internal solution:

glutamic acid, 98; EGTA, 15; Hepes, 10; Ca(OH)2, 0.9; MgATP, 5; disodium creatine phosphate, 5; glucose, 5; pentapotassium fura-2, 0.1; pH adjusted with CsOH to 7.0.

Caffeine and 4-chloro-m-cresol (4-CmC) were added to the external solution from stock solutions of 100 and 25 mM, respectively.

4-CmC, 4-AP and tris-maleate were purchased from Fluka, EGTA, MgATP and TTX from Sigma, CH3SO3H and CsOH from Aldrich, disodium creatine phosphate from Boehringer and pentapotassium fura-2 from Molecular Probes Europe. All other chemicals were from Merck, Baker (Deventer, Netherlands) or Riedel de Haen (Seelze, Germany).

Fluorescence recording and Ca2+ release analysis

The chamber was cooled to 12°C by Peltier elements and mounted on an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Axiovert 135 TV, Zeiss) equipped with a ×40 objective lens (Neofluar 40×, 0.75 W, Zeiss) and a photomultiplier (R268, Hamamatsu). Fluorescence measurements of fura-2 were carried out at 500 nm with excitation wavelengths of 360 nm (F360) and 380 nm (F380), as described previously (Struk et al. 1998).

Numerical analysis of the raw data was performed off-line with software written in Turbo Pascal 7.0 (Borland, Scotts Valley, USA). After background light subtraction, the ratio R = F380/F360 was converted to the concentration of free myoplasmic calcium ([Ca2+], free calcium) using eqn (1) which takes into account the fact that free Ca2+ is not instantaneously in equilibrium with calcium bound to the indicator (Klein et al. 1988).

| (1) |

where Rmax and Rmin are the limiting values of R at complete and zero dye saturation, respectively, and kon and koff are the on- and off-rate constants. The rate of Ca2+ release was estimated by quantifying Ca2+ binding and transport according to the general procedure of Baylor et al. (1983). This method uses a Ca2+ distribution model and kinetic parameters of the Ca2+ binding components of the myoplasm. The free calcium transient is used to calculate the Ca2+ occupancies of the various compartments of the model which are then summed to derive the total amount of released Ca2+ as a function of time. The time derivative of this release estimate determines the flux of Ca2+ from the SR. For the model equations used see Baylor et al. (1983) and the Appendix by Brum, Rios & Schneider in Brum et al. (1988). Different sets of published values for the model parameters were used and found to change the calculated time course of Ca2+ release only marginally (see Discussion). The kinetic parameter values used for the calculations shown here were as follows:

On- and off-rate constants of fura-2 according to Struk et al. (1998): kon = 1.44 × 108 M−1 s−1, koff = 26 s−1.

On- and off-rate constants and total concentration of troponin C Ca2+ binding sites (values according to model 1 of Pape et al. 1993): kon = 57.5 μM−1 s−1, koff = 115 s−1, [troponin C] = 240 μM.

On- and off-rate constants for Ca2+ and Mg2+ and total concentration of parvalbumin binding sites (values according to model 1 of Pape et al. 1993): kon,Ca = 125 μM−1 s−1, koff,Ca = 0.5 s−1, kon,Mg = 0.033 μM−1 s−1, koff,Mg = 3 s−1, [parvalbumin] = 1500 μM.

On- and off-rate constants for Ca2+ and total concentration of EGTA (values according to Pape et al. 1995): kon = 2.5 μM−1 s−1, koff = 0.94 s−1, [EGTA] = 15 mM.

Sarcoplasmic reticulum pump parameters (values according to Shirokova & Rios, 1996a): pump stoichiomety n = 2, maximal pump rate M = 1 mM s−1, dissociation constant of individual pump site KD = 1 μM, concentration of pump sites = 50 μM.

Charge movement analysis

After each test depolarization (amplitude P), several control pulses of amplitude -P/4 were applied from a subtracting holding potential of -100 mV. The control current responses were averaged, scaled by a factor of 4 and added to the test current to obtain the non-linear membrane current. The non-linear current was normalized by the linear capacitance. The linear capacitance of the fibre was determined at 0 mV holding potential before polarizing and repriming the muscle fibre by determining the integral of the transient current component for 100 ms pulses to +40 mV and dividing this charge by the pulse amplitude. Before polarizing the fibre, most of the linear capacitive transient was electronically compensated with a transient subtractor. Stability of linear capacitance was verified by analysing the negative control pulses. The voltage dependence Y(V) of calcium release and charge movements was fitted with a Boltzmann relation (eqn (2)):

| (2) |

Here Ymax is the maximal value, V0.5 is the voltage of half-maximal activation and k a steepness parameter.

Data acquisition

Command signals to the voltage clamp were generated and analog signals from the voltage clamp and the photomultiplier (see below) were digitized by an AD/DA subsystem (CED 1401+, Cambridge Electronic Design) which was controlled by Turbo Pascal software run on an IBM AT486-compatible personal computer (Mechatronik, Ulm, Germany). Signals were filtered at 500 Hz using an 8-pole Bessel filter and sampled at a rate of 4 kHz.

Unless otherwise stated, averaged data are presented as means ±s.e.m. Differences between mean values were statistically analysed using Student's t test and considered to be significant if P≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Changes in resting Ca2+ concentration

The experiments reported here were carried out with a concentration of 5 μM 4-CmC which was well below the threshold for the induction of spontaneous contracture in experiments on human muscle fibre bundles (Herrmann-Frank et al. 1996b) and produced a similar effect in potentiating voltage-controlled Ca2+ release in frog muscle to 0.5 mM caffeine (see below).

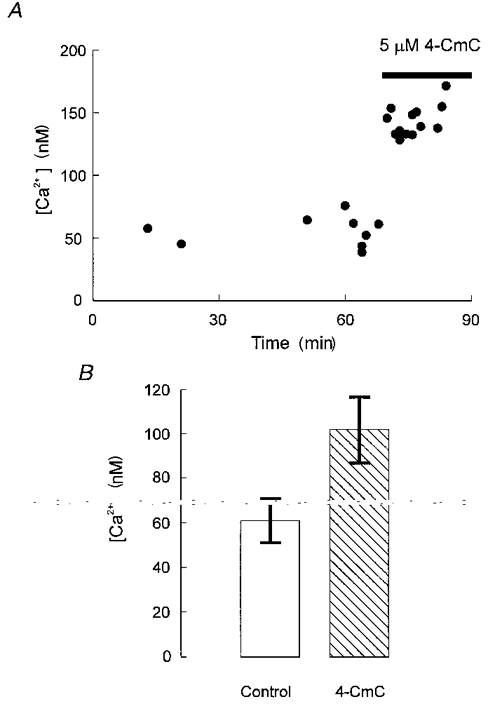

Figure 1A shows the effect of 5 μM 4-CmC on the free calcium concentration in a resting cut fibre (hereafter called ‘resting calcium’) equilibrated with an internal solution containing 100 μM fura-2. The bar indicates the time interval during which the drug was applied to the external pool of the Vaseline gap chamber. The resting fluorescence at 380 nm excitation dropped immediately after application of the solution. The calculated increase in resting Ca2+ in this case was from about 50 nM to about 150 nM. In control experiments carried out in a quartz microcapillary of 100 μm internal diameter (Vitro Dynamics, Rockaway, USA) even 200 μM 4-CmC had no effect on fluorescence. Figure 1B shows the mean resting Ca2+ from eight similar experiments shortly before and immediately after the application of 5 μM 4-CmC. The result indicates an increase from 61 ± 10 to 100 ± 20 nM, which is a significant difference according to the t test for paired data (P = 0.05).

Figure 1. Effect of 5 μM 4-CmC on the free myoplasmic calcium concentration in resting muscle fibres polarized to -80 mV.

A, measurements of resting Ca2+ over a time range of more than an hour. During the time indicated by the horizontal bar, 4-CmC was applied by perfusion of the external chamber pool. B, increase in the free calcium concentration stimulated by 5 μM 4-CmC at a potential of -80 mV determined from 8 experiments of the kind shown in A.

Potentiation of Ca2+ release

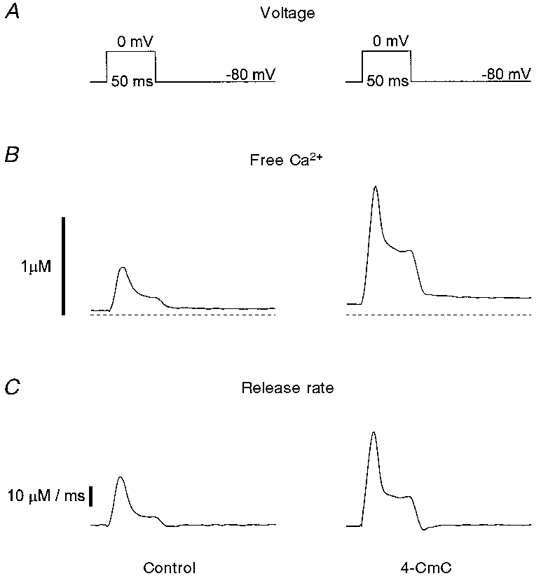

Figure 2B shows the effect of 0.5 μM 4-CmC on free calcium transients. Pulses of 50 ms duration depolarizing the fibre membrane from -80 to 0 mV were applied before (left) and after (right) the application of 4-CmC to the external pool. Clearly, in addition to the rise in resting Ca2+, the size of the depolarization-induced Ca2+ transient increased significantly. Figure 2C shows the release rate estimated from the free calcium transient as outlined in Methods. The peak attained at 12.0 ms (control) and 13.6 ms (4-CmC) after the start of the stimulus increased from 24.4 to 47.0 μM ms−1, while the steady level reached at the end of the pulse increased from 4.1 to 14.0 μM ms−1.

Figure 2. Potentiation of voltage-controlled Ca2+ release by 4-CmC.

A, a cut muscle fibre was stimulated by rectangular voltage pulses depolarizing the membrane from -80 to 0 mV. B, free calcium transient3s calculated from fura-2 fluorescence ratio signals before (left) and after (right) the application of 5 μM 4-CmC. C, rate of release calculated from the Ca2+ transients shown in B.

Voltage dependence of Ca2+ release

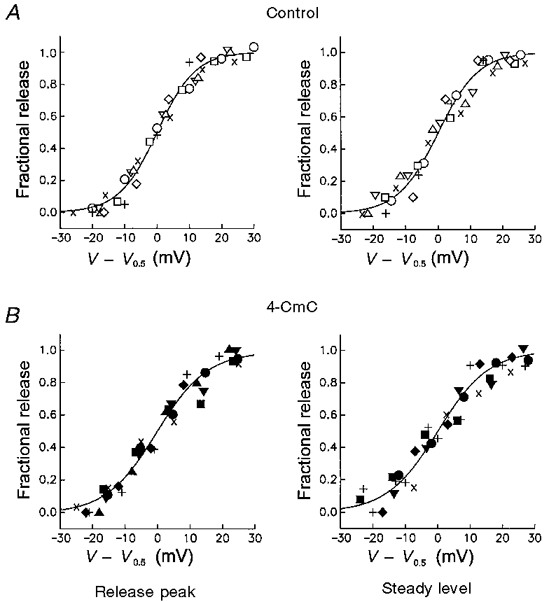

Figure 3 shows both the peak and steady level of the release rate compiled from eight experiments as a function of voltage. Each release-voltage relation was separately fitted with a single Boltzmann function (eqn (2)). The continuous lines in Fig. 3 were constructed using the mean values of the free parameters of the fit, which are summarized in Table 1. The fitted maximal release rates were significantly larger in 4-CmC compared with controls both for the peak and the steady level (by a factor of 1.3 and 1.7, respectively). The voltage of half-maximal activation was unchanged while the steepness parameter k increased by a factor of about 1.3. This increase was statistically significant only in the case of the peak release. Even though the effects of 4-CmC could not be reversed within 20 min after reperfusing with the control solution, the changes were definitely specific to the application of the drug since they were not observed in the absence 4-CmC. The fibres remained electrically stable in these experiments after the solution change, as evidenced by negligible changes in linear capacitance (see below).

Figure 3. Effect of 4-CmC on the voltage dependence of Ca2+ release.

Normalized peak rate of release (left) and release flux at 50 ms of depolarization (right) as a function of deviation from the voltage of half-maximal activation. Continuous lines are Boltzmann functions constructed with the mean best-fit parameters obtained from individual experiments. Parameters are summarized in Table 1 A, control conditions. B, measurements in 5 μM 4-CmC. Same experiments as in Fig. 1B.

Table 1.

Effects of 4-CmC on parameters describing the voltage dependence of Ca2+ release and intramembranous charge movement

| Control | 4-CmC | |

|---|---|---|

| Peak release | ||

| Maximum rate (μm ms−1) | 22.0 ± 1.9 | 27.5 ± 1.6* |

| Half-maximal activation (V0.5) (mV) | −17.1 ± 0.9 | −18.1 ± 0.9 |

| Steepness parameter (k) (mV) | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 0.3* |

| Steady level release | ||

| Maximum rate (μm ms−1) | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 6.7 ± 1.1* |

| Half-maximal activation (V0.5) (mV) | −18.8 ± 0.8 | −18.9 ± 0.6 |

| Steepness parameter (k) (mV) | 6.2 ± 0.4 | 7.8 ± 0.4 |

| Charge movements | ||

| Maximum rate (pC nF−1) | 28.4 ± 0.4 | 35.4 ± 0.3* |

| Half-maximal activation (V0.5) (mV) | −25.5 ± 0.5 | −23.9 ± 0.3 |

| Steepness parameter (k) (mV) | 12.0 ± 0.3 | 13.4 ± 0.2 |

See Methods for definition of parameters.

Significant differences at P = 0.05. Differences in parameters were tested for significance using the t test for paired data.

Intramembranous charge movements

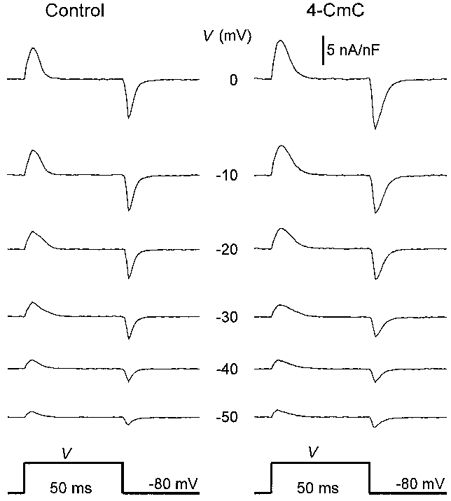

To decide whether 4-CmC affected the voltage sensor for Ca2+ release, intramembrane charge movements were analysed from the current records obtained in parallel with the Ca2+ signals (see Methods). Figure 4 shows the non-linear current of a fibre at different pulse potentials before and after application of 4-CmC. The signals were identified as intramembrane charge movements by comparing their integrals at the beginning and at the end of the pulse. Figure 5A shows that on-off equality was maintained up to a potential of 0 mV. The deviation above this potential (i.e. at +10 mV) probably results from a contribution of the Ca2+ inward current (Horowicz & Schneider, 1981), which, even though slow, is partially activated at this potential within the 50 ms depolarization of the pulse.

Figure 4. Intramembrane charge movements.

Non-linear capacitive currents at different depolarizations in a cut fibre before (left) and after (right) application of 5 μM 4-CmC. Linear capacitance, 7.0 nF.

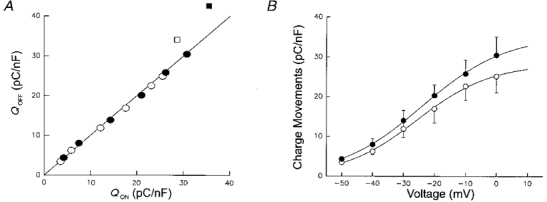

Figure 5. Voltage dependence of intramembrane charge movements.

A, non-linear charge moved during repolarization (Qoff) plotted versus the charge moved during depolarization (Qon). The continuous line indicates equality of Qon and Qoff. Both in controls (open symbols) and after application of 5 μM 4-CmC (filled symbols) on-off charge equality was maintained up to a depolarization of 0 mV (circles). A deviation from the line occurred at the potential of +10 mV (squares). B, charge density as a function of membrane potential. Integrals of ‘on’ and ‘off’ non-linear currents were averaged. ○, controls; •, after application of 4-CmC. Averaged data from 8 experiments.

The non-linear charge moved by the pulse normalized to the linear capacitance of the fibre is plotted in Fig. 5B as a function of voltage. Only the voltages from -50 to 0 mV, for which on-off equality of the charge was found, were used. The data represent mean values from eight experiments. The individual voltage dependences were fitted by Boltzmann relations. The means of the resulting free parameter values are tabulated in Table 1. They were used to construct the continuous lines in Fig. 5B. While the parameters characterizing the voltage dependence (V0.5 and k) were not significantly different, the amplitude parameter Qmax was increased by 25 % in the presence of 4-CmC. Linear capacitance was not altered by the solution change to 4-CmC in these experiments as determined by integrating the capacitive current of hyperpolarizing control pulses. Thus, apparently the amplitude changes in the rate of release paralleled a small but not negligible change in the amount of mobile charge displaced during depolarization.

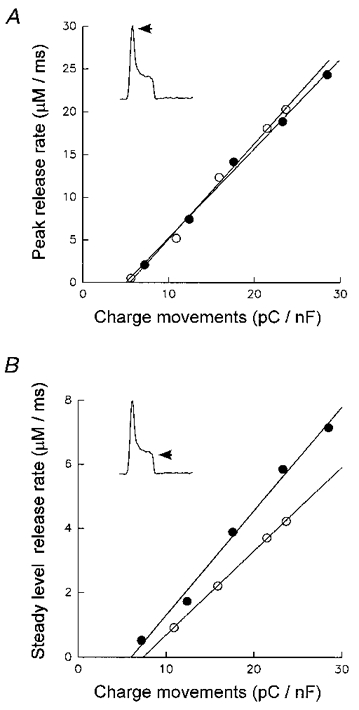

Release flux as a function of mobile charge

To decide whether the observed increase in intramembrane charge movement could fully account for the potentiation of release we constructed release-charge relations, termed ‘transfer functions’ by Shirokova & Rios (1996b). Figure 6A and B show the charge dependence of the peak and the steady level of release in the absence (○) and in the presence (•) of 4-CmC (data from 8 fibres). The data were obtained from Figs 3 and 5B using the voltage range from -40 to 0 mV. The release-charge relations could be well described by straight lines (Melzer et al. 1986). Using power functions of charge produced less satisfactory fits. In particular, a function proportional to the fourth power of charge (Simon & Hill, 1992) did not describe the data well due to its high curvature. Figure 6A shows that the release- charge relations for the peak of release virtually superimpose, indicating that the increase in peak can be explained by the additional charge movement (or vice versa) measured in the presence of 4-CmC. The linear fit to the data produced slope and threshold charge values of 1.12 ± 0.05 MF s−1 C−1 and 5.45 ± 0.73 pC nF−1, respectively, for controls and of 1.04 ± 0.04 MF s−1 C−1 and 5.00 ± 0.74 pC nF−1, respectively, for fibres with 4-CmC. On the other hand, the corresponding relation for the steady level (Fig. 6B) differed in measurements with and without 4-CmC. The slope of the straight lines fitted to the data increased from 0.261 ± 0.003 to 0.325 ± 0.016 MF s−1 C−1, while the threshold charge extrapolated from the linear fit was not significantly different (7.39 ± 0.21 pC nF−1 in control versus 6.02 ± 1.03 pC nF−1 with 4-CmC). A comparable result was obtained when fitting individually the release-charge relations of the subset of experiments (n = 6) in which both signals were measured simultaneously. Again, the only significant difference in the averaged fit parameters was an increase of the slope of the curves relating steady level release to charge density (t test for paired data, P = 0.05). The slope increased from 0.27 ± 0.03 to 0.34 ± 0.03 MF s−1 C−1. The threshold charge values were 8.4 ± 1.8 pC nF−1 (control) and 6.2 ± 0.9 pC nF−1 (4-CmC). The corresponding values of slope and threshold charge for the peak rate of release were 1.5 ± 0.2 MF s−1 C−1 and 8.0 ± 1.1 pC nF−1, respectively, for controls and 1.6 ± 0.2 MF s−1 C−1 and 6.7 ± 1.0 pC nF−1, respectively, after applying 4-CmC.

Figure 6. Dependence of release rate on intramembrane charge movement.

Peak (A) and steady level (B) of rate of release plotted as a function of non-linear charge at potentials -40, -30, -20, -10 and 0 mV. ○, control; •, 5 μM 4-CmC. In B, the control steady level at -40 mV was indistinguishable from zero and has been omitted. Data from experiments of Figs 3 and 5B.

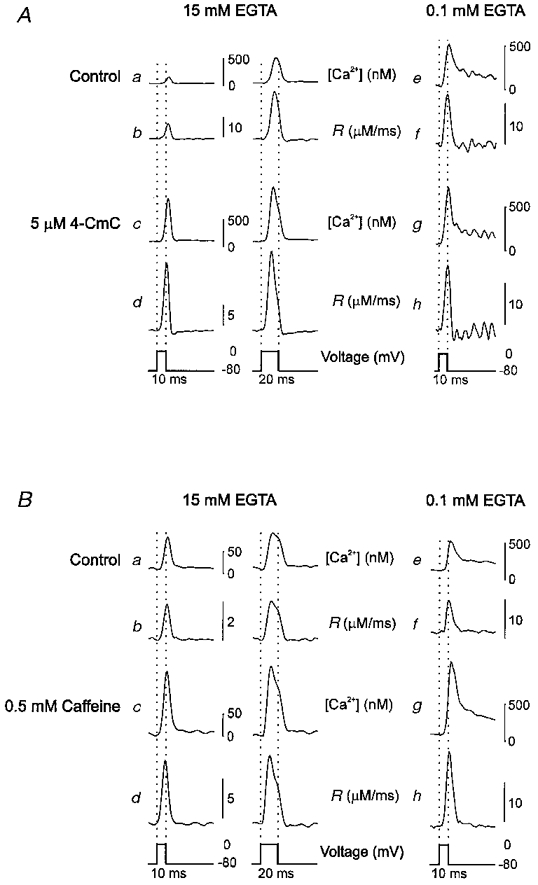

Comparison of 4-CmC and caffeine

4-CmC has been shown to affect the ryanodine receptor at concentrations almost two orders of magnitude lower than the classical Ca2+ releasing agent caffeine (Herrmann-Frank et al. 1996a). Subthreshold caffeine concentrations (often 0.5 mM) have been used in a number of previous studies to investigate potentiation of voltage-controlled Ca2+ release (Lüttgau & Oetliker, 1968; Kovacs & Szücs, 1983; Delay et al. 1986; Konishi & Kurikara, 1987; Simon et al. 1989; Klein et al. 1990). The experiments described in this final section were carried out to look for possible differences in the mode of action of the two drugs by comparing the effects of 0.5 mM caffeine with those of 5 μM 4-CmC.

Like 4-CmC, caffeine increased the amplitude of depolarization-induced Ca2+ release in our experiments. However, while 4-CmC predominantly increased the steady level component, caffeine increased both peak and steady level to approximately the same extent. In eight experiments with depolarizations to 0 mV of 50 ms duration, peak release changed by a factor of 1.3 ± 0.2 from 19.5 ± 2.51 to 26.2 ± 2.23 μM ms−1 after application of 4-CmC and in four corresponding experiments with 0.5 mM caffeine by a factor of 2.2 ± 0.3 (from 13.4 ± 5.60 to 30.1 ± 4.25 μM ms−1), while the steady level increased by factors of 2.0 ± 0.2 (from 3.9 ± 0.53 to 7.9 ± 0.74 μM ms−1) and 2.3 ± 0.7 (from 2.6 ± 0.85 to 6.1 ± 1.10 μM ms−1), respectively. According to the t test for paired data all potentiation factors were significantly larger than 1 (P = 0.05). Even though the overall potentiation was somewhat stronger in caffeine, the resting Ca2+ level did not change significantly. It was 41 ± 6 nM before and 44 ± 7 nM after the application of 0.5 mM caffeine, but 61 ± 10 nM before and 100 ± 20 nM after the application of 5 μM 4-CmC (see Fig. 1).

Interesting with regard to the mechanism of caffeine was the observation reported by Simon et al. (1989) and Klein et al. (1990) that 0.5 mM caffeine caused a loss of voltage control on repolarization. Instead of rapidly terminating release, repolarization to the holding potential after a short depolarization led to a considerably slower decline of the release rate. The turn-off kinetics became similar to the spontaneous decline seen during longer depolarizations (Melzer et al. 1984, 1987) which is attributed to calcium-dependent inactivation (Schneider & Simon, 1988). Figure 7 compares the stimulating effect of 5 μM 4-CmC (Aa-d) and 0.5 mM caffeine (Ba-d) on short (10 and 20 ms) depolarizations. In neither case could a slowing of release kinetics at repolarization be observed (for details see the figure legend). It must be noted that the experimental conditions differed from those of Simon et al. (1989). Our intracellular solution contained 15 mM EGTA instead of 0.1 mM. We, therefore, repeated the comparison with an intracellular solution containing 0.1 mM EGTA (10 ms pulses). The result is shown in Fig. 7Ae-h and Be-h. Caffeine and 4-CmC produced a significant increase in free calcium signal and Ca2+ release rate but the turn-off kinetics remained fast in both cases.

Figure 7. Effect of caffeine and 4-CmC on the time course of free calcium and the rate of release.

A, free calcium concentration (a, c, e and g) and calculated rate of release R (b, d, f and h) in a cut muscle fibre depolarized to 0 mV for 10 or 20 ms (see pulse scheme at the bottom) before and after application of 5 μM 4-CmC. B, free calcium concentration (a, c, e and g) and calculated rate of release R (b, d, f, and h) before and after application of 0.5 mM caffeine. In both A and B, traces a-d are from one experiment with 15 mM internal EGTA

DISCUSSION

Effects of 4-CmC on Ca2+ turnover

In this study we characterized enhancement of E-C coupling by 4-chloro-m-cresol (4-CmC), which is known as a potent intracellular Ca2+ releasing agent. 4-CmC has previously been shown to stimulate the release of Ca2+ from heavy sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles and to deplete a caffeine- but not an IP3-sensitive store in PC12 cells (Zorzato et al. 1993). The idea that the drug acts on ryanodine receptors was confirmed by experiments demonstrating that the degree of ryanodine binding (an indirect measure of ryanodine receptor activation) was enhanced by 4-CmC and that the open probability of the isolated ryanodine receptor in artificial lipid bilayers was increased (Herrmann-Frank et al. 1996a,b). The present study is the first one to explore the effects of 4-CmC on Ca2+ release in the presence of functional voltage sensor control.

For caffeine it is known that concentrations well below the threshold for inducing a contracture potentiate E-C coupling, i.e. enhance Ca2+ release triggered by action potential or voltage clamp depolarization (Lüttgau & Oetliker, 1968; Kovacs & Szücs, 1983; Delay et al. 1986; Konishi & Kurihara, 1987; Simon et al. 1989; Klein et al. 1990). Here we show that 4-CmC at a concentration even lower than those found to activate Ca2+ flux through purified ryanodine receptors (Herrmann-Frank et al. 1996a,b) produced clearly detectable changes in Ca2+ turnover in voltage-clamped muscle fibres. The resting free Ca2+ concentration increased upon application of 5 μM 4-CmC (despite heavy EGTA buffering) and so did the depolarization-induced Ca2+ release rate.

As reported previously (Struk et al. 1998), the time course of the calculated rate of release under the conditions used here was quite invariant in response to changes in the parameter values of the model used for the calculations. We compared the result obtained with four different sets of kinetic parameters for fibre-intrinsic binding sites adopted from Jaquemond et al. (1991), Pape et al. (1993) and Shirokova & Rios (1996a). The different parameter values were combined with two alternative sets of rate constants for Ca2+ binding to EGTA (Smith et al. 1984, and means of values empirically determined in cut fibres by Shirokova & Rios, 1996a). All calculations were carried out with the on-rate constant of fura-2 estimated in Struk et al. (1998; see Methods) and a fivefold smaller value, corresponding to the lowest estimates reported by other groups (Baylor & Hollingworth, 1988; Hollingworth et al. 1992; Pape et al. 1993). Despite changes by a maximal factor of about 10 in absolute scale, the time course showed only minor deviations from the one displayed in Fig. 2. Therefore, we are confident that the choice of parameters used to calculate release has not influenced the results reported here.

The increase in the Ca2+ release rate caused by 4-CmC was more marked during the steady level phase, i.e. in the component that has been suggested to be controlled primarily by voltage. The release process is also known to be modulated by intracellular Ca2+. Modulation has been found both at the voltage sensor and at the ryanodine receptor. A local change of membrane surface potential by Ca2+ binding and direct effects of Ca2+ on voltage sensor charge movements have been suggested (Pizarro et al. 1991; Jong et al. 1995b; Pape, Jong & Chandler, 1996; Stroffekova & Heiny, 1997a,b). On the other hand, calcium-dependent activation and inactivation are characteristics of the isolated ryanodine receptor (Smith et al. 1986; Hermann-Frank & Lehmann-Horn, 1996) and corresponding mechanisms have been described for intact fibres (Schneider & Simon, 1988; Jaquemond et al. 1991; Csernoch et al. 1993; Jong et al. 1995a; Pape et al. 1998). The stronger effect of 4-CmC on the steady level of release may be due to the higher contribution of Ca2+- rather than voltage-dependent processes during peak release (Csernoch et al. 1993). Alternatively, the rapid inactivation (especially if it is coupled to activation) might have concealed some of the effect on peak amplitude.

Effects on intramembrane charge movements

In addition to the effects on the rate of release, we observed a 25 % increase in the total intramembraneous charge movements (Fig. 5B), which might have resulted from a direct effect of the drug on the voltage sensor but might also be a consequence of the elevated free calcium concentration. An increase in charge movement on raising the myoplasmic free calcium concentration to up to about 1 μM by application of 10 mM caffeine was reported by Shirokova & Rios (1996b). The mechanism suggested by the authors (depolarization of the transverse tubular membrane by binding of released calcium) predicts a shift in the voltage dependence and no increase in Qmax as found here (Fig. 5B). In that study, only charges displaced by small depolarizations could be investigated and information on any change in Qmax was not available. Stroffekova & Heiny (1997a,b), on the other hand, reported a quite dramatic increase in Qmax when increasing the resting free calcium concentration. They buffered the intracellular space at pCa values of 9, 7 and 6.5 and found Qmax values of 34, 39 and 52 nC μF−1, respectively, i.e. an increase almost proportional to the calculated free Ca2+ concentration. The authors suggest that raising the intracellular free Ca2+ concentration leads to restoration of previously unavailable voltage sensors. Using their data, a change of 2.3 nC μF−1 would be predicted for the 39 nM change in resting Ca2+ determined here. Considering the different experimental approaches and possible errors in establishing or determining the free concentration of Ca2+ in the myoplasm, this value is not far from the 7 nC μF−1 estimated in our experiments. The measured charge difference would for instance result, if the on-rate constant of fura-2, a parameter not very precisely known for the intracellular environment (see above), was in fact threefold less than the one used here.

Possible mechanisms of potentiation

Studying voltage-clamped cut muscle fibres exposed to 0.5 mM external caffeine, Simon et al. (1989) found a loss of control of release by the membrane voltage indicated by the observation that repolarization failed to turn off Ca2+ release after short depolarizing pulses (see also Klein et al. 1990). A slowing of the kinetics of release termination after short pulse repolarization could not be seen in our experiments, either with 4-CmC or with caffeine. Since our high internal EGTA concentration might have interfered with a calcium-dependent feedback mechanism, we also used low internal EGTA (0.1 mM), but with a similar result. In experiments with high internal EGTA and caffeine concentrations Shirokova & Rios (1996a) could likewise not detect any slowing of release rate turn-off kinetics. Possibly a still-unknown modulatory condition is additionally required to weaken the control of Ca2+ release by membrane voltage in the presence of caffeine. This condition, however, seems not to be necessary for the release potentiation by caffeine or 4-CmC.

Slope and threshold of the peak release-charge relation in controls were close to the values of 1.5 μM ms−1 nC−1μF and 8.1 nC μF−1 reported by Melzer et al. (1986) and remained essentially unchanged by 4-CmC. On the other hand, 4-CmC caused a steepening of the dependence of steady level release on intramembrane charge movement. This indicates that the increase in Qmax is not sufficient to explain the potentiation and points to an increased sensitivity of the ryanodine receptor to its voltage sensor input. The finding may be explained by a modulation of the voltage-dependent transduction process, perhaps through a sensitization of the release channel to the voltage-sensor effector signal, which is thought to involve the II-III loop of the DHP receptor α1 subunit (Tanabe et al. 1990; Lu et al. 1994; for review see Melzer et al. 1995). A similar sensitization, i.e. ‘enhanced propensity of release channels to open under control of voltage sensors’, has been suggested for caffeine (10 mM) by Shirokova & Rios (1996b).

Even though potentiation of voltage-triggered release was similar with 5 μM 4-CmC and 0.5 mM caffeine, the response profile differed in detail. While enhancement of release by 4-CmC paralleled increased resting Ca2+, even at this low concentration, this was not the case for caffeine. Furthermore, both peak and steady level release were increased in caffeine while 4-CmC potentiated the steady level release more strongly. This indicates different mechanisms, and therefore sites of action, for the two drugs and is consistent with experiments by Herrmann-Frank et al. (1996b), who found a stronger effect of 4-CmC on the luminal side of the ryanodine receptor. However, despite probably affecting different sites and exhibiting their effects at strikingly different concentrations, both caffeine (Shirokova & Rios, 1996a,b) and 4-CmC seem to act by enhancing voltage-dependent transduction in addition to depolarization-independent opening of the ryanodine receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr F. Lehmann-Horn for support and encouragement, Dr G. Szücs for help and valuable discussions in the initial phase of the work, Drs A. Herrmann-Frank, H. C. Lüttgau, and D. G. Stephenson for providing unpublished material, W. Grabowski and E. Schoch for constructing experimental equipment, and U. Richter for technical help. This work was supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to W. Melzer (Me-713/10-1).

References

- Baylor SM, Chandler WK, Marshall MW. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release in frog skeletal muscle fibres estimated from Arsenazo III calcium transients. The Journal of Physiology. 1983;344:625–666. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor SM, Hollingworth S. Fura-2 calcium transients in frog skeletal muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;403:151–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brum G, Ríos E, Stéfani E. Effects of extracellular calcium on calcium movements for excitation-contraction coupling in frog skeletal muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;398:441–473. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csernoch L, Jaquemond V, Schneider MF. Microinjection of strong calcium buffers suppresses the peak of calcium release during depolarization in frog skeletal muscle fibres. Journal of General Physiology. 1993;101:297–333. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delay M, Ribalet B, Vergara J. Caffeine potentiation of calcium release in frog skeletal muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology. 1986;375:535–559. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeyer D, Melzer W, Pohl B. Effects of gallopamil on calcium release and intramembrane charge movements in frog skeletal muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;421:343–362. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann-Frank A, Lehmann-Horn F. Regulation of the purified Ca2+ release channel/ryanodine receptor complex of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum by luminal calcium. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;432:155–157. doi: 10.1007/s004240050117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann-Frank A, Lüttgau HC, Stephenson DG. Caffeine and excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle: A stimulating story. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1999. in the Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Herrmann-Frank A, Richter M, Lehmann-Horn F. 4-Chloro-m-cresol: A specific tool to distinguish between malignant hyperthermia-susceptible and normal muscle. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1996a;52:149–155. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann-Frank A, Richter M, Sarközi S, Mohr U, Lehmann-Horn F. 4-Chloro-m-cresol, a potent and specific activator of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1996b;1289:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(95)00131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth S, Harkins AB, Kurebayashi N, Konishi M, Baylor SM. Excitation-contraction coupling in intact frog skeletal muscle fibers injected with millimolar concentrations of fura-2. Biophysical Journal. 1992;63:224–234. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81599-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowicz P, Schneider MF. Membrane charge movement in contracting and non-contracting skeletal muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology. 1981;314:565–593. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemond V, Csernoch L, Klein MG, Schneider MF. Voltage-gated and calcium-gated calcium release during depolarization of skeletal muscle fibers. Biophysical Journal. 1991;60:867–873. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82120-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong D-S, Pape PC, Baylor SM, Chandler WK. Calcium inactivation of calcium release in frog cut muscle fibres that contain millimolar EGTA or Fura-2. Journal of General Physiology. 1995a;106:337–338. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong D-S, Pape PC, Chandler WK. Effect of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium depletion on intramembranous charge movement in frog cut muscle fibers. Journal of General Physiology. 1995b;106:659–704. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.4.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MG, Simon BJ, Schneider MF. Effects of caffeine release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in frog skeletal muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;425:599–626. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MG, Simon BJ, Szücs G, Schneider MF. Simultaneous recording of calcium transients in skeletal muscle using high and low affinity calcium indicators. Biophysical Journal. 1988;53:971–988. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83178-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M, Kurihara S. Effects of caffeine on intracellular calcium concentration in frog skeletal muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;383:269–283. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs L, Rios E, Schneider MF. Measurement and modification of free calcium transients in frog skeletal muscle fibres by a metallochromic indicator dye. The Journal of Physiology. 1983;341:559–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs L, Szücs G. Effect of caffeine on intramembrane charge movement and calcium transients in cut skleletal muscle fibres of the frog. The Journal of Physiology. 1983;343:161–196. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Xu L, Meissner G. Activation of the skeletal muscle calcium release channel by a cytoplasmic loop of the dihydropyridine receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:6511–6516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüttgau HC, Oetliker H. The action of caffeine on the activation of the contractile mechanism in striated muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology. 1968;194:51–74. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan DH, Phillips M. Malignant hyperthermia. Science. 1992;256:789–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1589759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer W, Herrmann-Frank A, Lüttgau HC. The role of Ca2+ ions in excitation-contraction coupling of skeletal muscle fibres. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1241:59–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(94)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer W, Rios E, Schneider MF. Time course of calcium release and removal in skeletal muscle fibers. Biophysical Journal. 1984;45:637–641. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84203-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer W, Rios E, Schneider MF. A general procedure for determining calcium release in frog skeletal muscle. Biophysical Journal. 1987;51:849–864. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83413-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer W, Schneider MF, Simon BJ, Szücs G. Intramembrane charge movements and calcium release in frog skeletal muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1986;373:481–511. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson JR, Louis CF. Malignant hyperthermia: excitation-contraction coupling, Ca2+ release channel, and cell Ca2+ regulation defects. Physiological Reviews. 1996;76:537–592. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Jong D-S, Chandler WK. Effect of Fura-2 on action potential-stimulated calcium release in cut twitch fibers from frog muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 1993;102:295–332. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Jong D-S, Chandler WK. Calcium release and its voltage dependence in frog cut muscle fibers equilibrated with 20 mM EGTA. Journal of General Physiology. 1995;106:259–336. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Jong D-S, Chandler WK. A slow component of intramembranous charge movement during sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release in frog cut muscle fibres. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;107:79–101. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Jong D-S, Chandler WK. Effects of partial sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium depletion on calcium release in frog cut muscle fibers equilibrated with 20 mM EGTA. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;112:263–295. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro G, Csernoch L, Uribe I, Rodriguez M, Rios E. The relationship between Qγ and Ca release from sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 1991;97:913–947. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.5.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MF, Simon BJ. Inactivation of calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in frog skeletal muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;405:727–745. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirokova N, Rios E. Activation of Ca2+ release by caffeine and voltage in frog skeletal muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 1996a;493:317–339. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirokova N, Rios E. Caffeine enhances intramembranous charge movement in frog skeletal muscle by increasing cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration. Journal of General Physiology. 1996b;493:341–356. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon BJ, Hill DA. Charge movement and SR calcium release in frog skeletal muscle can be related by a Hodgkin-Huxley model with four gating particles. Biophysical Journal. 1992;61:1109–1116. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81920-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon BJ, Klein MG, Schneider MF. Caffeine slows turn-off of calcium release in voltage clamped skeletal muscle fibres. Biophysical Journal. 1989;55:793–797. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82878-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JS, Coronado R, Meissner G. Single channel measurements of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Activation by Ca2+ and ATP and modulation by Mg2+ Journal of General Physiology. 1986;88:573–588. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.5.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PD, Liesegang GW, Berger RL, Czerlinski G, Podolsky RJ. A stopped-flow investigation of calcium ion binding by ethylene glycol bis(β-aminoethyl)-N,Nv′-tetraacetic acid. Analytical Biochemistry. 1984;143:188–195. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroffekova K, Heiny JA. Triadic Ca2+ modulates charge movement in skeletal muscle. General Physiology and Biophysics. 1997a;16:59–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroffekova K, Heiny JA. Stimulation-dependent redistribution of charge movement between unavailable and available states. General Physiology and Biophysics. 1997b;16:79–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struk A, Szücs G, Kemmer H, Melzer W. Fura-2 calcium signals in skeletal muscle fibres loaded with high concentrations of EGTA. Cell Calcium. 1998;23:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe T, Beam KB, Adams A, Niidome T, Numa S. Regions of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor critical for excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 1990;346:567–569. doi: 10.1038/346567a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegazzin V, Scutari E, Treves S, Zorzato F. Chlorocresol, an additive to commercial succinylcholine, induces contracture of human malignant hyperthermia-susceptible muscles via activation of the ryanodine receptor Ca2+ channel. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:1380–1385. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199606000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorzato F, Scutari E, Tegazzin V, Clementi E, Treves S. Chlorocresol: An activator of ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca2+ release. Molecular Pharmacology. 1993;44:1192–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]