Abstract

Capsaicin activation of the pulmonary C fibre vanilloid receptor (VR1) evokes the pulmonary chemoreflex and reflex bronchoconstriction. Among potential endogenous ligands of C fibre afferents, lactic acid has been suggested as a promising candidate. We tested the hypotheses that (a) lactic acid behaves as a stimulant of C fibre receptors in the newborn dog to cause reflex bronchoconstriction, and (b) lactic acid causes reflex bronchoconstriction via the same pulmonary C fibre receptor mechanism as capsaicin using the competitive capsaicin/VR1 receptor antagonist capsazepine.

Right heart injection of lactic acid caused a significant increase (47 ± 8.0%) in lung resistance (RL) that was atropine sensitive (reduced by 75%; P < 0.05), consistent with reflex activation of muscarinic efferents by stimulation of C fibre afferents.

Infusion of the competitive capsaicin antagonist capsazepine caused an 80% reduction (P < 0.01) in the control bronchoconstrictor response (41 ± 8.5% increase in RL) to right heart injections of capsaicin. The effects of capsazepine are consistent with reversible blockade of the VR1 receptor to abolish C fibre-mediated reflex bronchoconstriction.

Lactic acid-evoked increases in RL were unaffected by VR1 blockade with capsazepine, consistent with a separate lactic acid-induced reflex mechanism.

We conclude that (a) putative stimulation of C fibres with lactic acid causes reflex bronchoconstriction in the newborn dog, (b) capsazepine reversibly antagonizes reflex bronchoconstriction elicited by right heart injection of capsaicin, presumably by attenuating capsaicin-induced activation of the C fibre ‘capsaicin’ receptor (VR1), and (c) capsazepine resistance of lactic acid-induced bronchoconstriction indicates that lactic acid evokes reflex bronchoconstriction by a separate mechanism, possibly via the acid-sensing ionic channel.

Stimulation of non-myelinated pulmonary afferents evokes the pulmonary chemoreflex, a triad of apnoea, bradycardia and hypotension that is accompanied by bronchoconstriction (Paintal, 1973; Coleridge & Coleridge, 1984; Coleridge et al. 1989). Injection of the vanilloid compound capsaicin into the pulmonary circulation of numerous species activates pulmonary C fibres (also termed ‘J-receptors’; Paintal, 1973) and evokes the pulmonary chemoreflex (Paintal, 1973; Coleridge et al. 1989). The recently developed competitive capsaicin antagonist capsazepine abolishes capsaicin-induced apnoea, bradycardia and hypotension in the adult rat in vivo (Lee & Lundberg, 1994), as well as significantly attenuating capsaicin-induced C fibre activity both in vitro and in vivo (Dickenson & Dray, 1991; Belvisi et al. 1992; Lee & Lundberg, 1994; Fox et al. 1995). Furthermore, capsazepine has been shown to reduce capsaicin-induced activation of the recently cloned non-selective cation channel vanilloid receptor subtype 1 (VR1) (Caterina et al. 1997). Although the endogenous VR1 ligand has not been determined, both the metabolic byproducts accompanying the inflammatory process (lactic acid, H+) and inflammatory mediators themselves (histamine, seratonin, prostaglandin E2) have been identified as potential endogenous ligands for the C fibre ‘capsaicin’ receptor (Stahl & Longhurst, 1992; Bevan & Geppetti, 1994; Lee et al. 1996; Hong et al. 1997).

Hydrogen ions (H+) in general and lactic acid in particular have been shown to activate C fibre afferents similar to the effect seen with capsaicin (Stahl & Longhurst, 1992; Bevan & Geppetti, 1994; Fox et al. 1995; Lee et al. 1996; Hong et al. 1997) and evoke the pulmonary chemoreflex (Trenchard, 1986; Lee et al. 1996; Hong et al. 1997). In vitro studies have demonstrated that H+ inhibits the binding of the capsaicin analogue resiniferatoxin to vanilloid receptors, a finding that was attributed to competition for the same binding site (Szallasi et al. 1995). Lactic acid is produced at local sites of tissue ischaemia and inflammation in conditions that are characterized by increased airway reactivity (Lee et al. 1996). As such, lactic acid may act as an endogenous C fibre capsaicin receptor ligand (Stahl & Longhurst, 1992; Lee et al. 1996; Hong et al. 1997) that could reflexly increase airway resistance. The ability of lactic acid to evoke reflex bronchoconstriction appears to be untested in vivo in either the adult or neonate. In support of a role for lactic acid as an endogenous VR1 ligand, studies have shown that the competitive vanilloid receptor antagonist capsazepine attenuates the acid-induced decrease in tidal volume attributed to C fibre stimulation in the isolated perfused guinea-pig lung (Lou & Lundberg, 1992), as well as reducing acid-evoked C fibre activity in vitro (Urban & Dray, 1991; Fox et al. 1995). In contrast, biophysical studies suggest that H+per se is a weak VR1 receptor agonist (Caterina et al. 1997).

The role of lactic acid and H+ is particularly relevant in the newborn, where metabolic acidosis is a normal component of parturition (Koch & Wendel, 1968), as well as being an important constituent of neonatal inflammatory lung disease (Abman & Groothius, 1994). The newborn displays a capsaicin-induced reflex bronchoconstriction attributed to stimulation of pulmonary C fibre afferents (Anderson & Fisher, 1993). However, preliminary studies describing the lung compliance response to lactic acid suggested that it was absent in newborn rabbits (Ducros & Trippenbach, 1991).

On the basis of C fibre recordings, as well as studies of the effects of capsazepine on capsaicin- and lactic acid-induced apnoea, bradycardia and hypotension, we reasoned that capsazepine would abolish capsaicin-evoked bronchoconstrictor reflexes (Lee & Lundberg, 1994; Lee et al. 1996). Capsazepine should also abolish lactic acid-induced reflex bronchoconstriction if lactic acid acts at the capsaicin/VR1 receptor site. In the present study, we tested two hypotheses regarding the action of lactic acid on bronchomotor tone in the newborn. Firstly, that exogenous lactic acid behaves as a physiological C fibre stimulant to evoke cholinergic reflex bronchoconstriction, and secondly, that lactic acid acts via C fibre receptor mechanisms similar to capsaicin to cause reflex bronchoconstriction. To test the latter, we used the capsaicin/VR1 antagonist capsazepine to attempt to block bronchomotor responses to both capsaicin and lactic acid. Our studies demonstrate that lactic acid does behave as a physiological C fibre stimulant to cause reflex bronchoconstriction in the newborn. However, whereas capsaicin-induced increases in lung resistance are significantly attenuated by the competitive antagonist capsazepine, those of lactic acid are not.

METHODS

Surgical preparation

All experimental procedures conformed to the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and were approved by the Queen's University Animal Care Committee. Experiments were performed on 36 newborn mongrel dogs ranging in age from 1 to 9 days (mean ±s.e.m., 5 ± 0.4 days) and ranging in weight from 256 to 1063 g (mean, 569 ± 29.6 g). Animals were anaesthetized with an initial intraperitoneal injection of chloralose (0.05-0.0625 g kg−1) and urethane (0.5-0.625 g kg−1) and supplemental anaesthesia was administered intravenously at approximately 1 h intervals to maintain abolition of the withdrawal reflex and acute changes in blood pressure and heart rate. Animals were killed at the completion of the experiment with an overdose of anaesthetic.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) was monitored via needle electrodes connected to a preamplifier, oscilloscope and audio speaker. Animals were tracheotomized and ventilated with 40% O2/balance N2 at a ventilator frequency of ∼40-45 breaths min−1 and a tidal volume of ∼8-10 ml kg−1 adjusted to provide normal blood gases (pH = 7.41 ± 0.01, arterial partial pressure of CO2 (Pa,CO2) = 32.3 ± 1.2 mmHg, arterial partial pressure of O2 (Pa,O2) = 191.0 ± 12.6 mmHg). A mid-line thoracotomy was performed and an end-expiratory load of ∼2.3 cmH2O was established to provide a normal functional residual capacity (Fisher & Mortola, 1981). Transpulmonary pressure (PTP) was measured via a differential pressure transducer (Validyne MP45, ±50 cmH2O; Northridge, CA, USA) connected to the side port of the tracheal cannula. A femoral arterial line was inserted in most animals for blood gas sampling and arterial blood pressure (BP) measurement. A femoral venous line was established for administration of supplemental anaesthesia and infusion of capsazepine (Harvard Apparatus Syringe Infusion Pump, model 22). The right jugular vein was cannulated and a catheter advanced into the right heart (location confirmed post-mortem) for capsaicin and lactic acid injections. Inspiratory efforts were abolished by bilateral phrenic nerve section or paralysis with doxacurium chloride (0.025 mg kg−1i.v.), a non-depolarizing muscle relaxant with no muscarinic side effects (Okanlami et al. 1996). During paralysis, additional anaesthesia was administered based on the schedule used prior to paralysis (approximately every hour). Core temperature (Tc) was regulated with a heat lamp and a servo-controlled heating blanket (Harvard Apparatus Animal Blanket Control Unit, model no. 50-6956). Animals were placed in a body plethysmograph and respiratory flow (V)was measured with a pneumotachograph (Hans Rudolph, model 8300) connected to a differential pressure transducer (Validyne MP45, ±2 cmH2O). Flow, ECG, BP and PTP were acquired with a computerized chart recorder data acquisition package (CODAS, DATAQ Instruments, Akron, OH, USA).

Analysis of pulmonary mechanics

Transpulmonary pressure and respiratory flow were acquired on-line by an additional computer at a sampling frequency of 100 samples per second per channel for breath-by-breath calculation of inspiratory lung resistance (RL, cmH2O ml−1 s) and dynamic lung compliance (CL,dyn, ml cmH2O−1). Mean inspiratory lung resistance was calculated by dividing the mean pressure required to overcome the flow resistive properties of the lung by the mean inspiratory flow. CL,dyn was calculated by dividing the tidal volume by the transpulmonary pressure swing between points of zero flow during inspiration. Dynamic lung elastance (EL,dyn) was calculated from the reciprocal of CL,dyn.

Protocols

Effect of lactic acid on bronchomotor tone

To determine the effects of lactic acid on neonatal bronchomotor tone, we recorded the breath-by-breath response of pulmonary mechanics to right heart injection of lactic acid. In preliminary experiments we assessed the bronchomotor response to right heart injections of various doses of lactic acid ranging from 0.02 to 2.0 mmol kg−1. On the basis of these results we chose to use 0.4 mmol kg−1 since it was twice the threshold dose of 0.2 mmol kg−1, and it elicited a robust bronchomotor response on which we could test the effects of pharmacological antagonism.

In order to assess the reflex nature of the responses to lactic acid, responses of RL and EL,dyn to right heart injection of lactic acid were measured before and after muscarinic receptor blockade with atropine (2 mg kg−1) in 17 newborn dogs (4 ± 0.6 days old). The protocol consisted of three acquisition periods (5-8 min duration) separated by 15 min. Each acquisition period was preceded by flushing the jugular catheter with 37°C saline and inflating the lungs to ∼20 cmH2O to establish a constant volume history. Two minutes after the inflation, a 5-8 min acquisition period began. The first trial consisted of saline (0.2 or 0.4 ml) and ACh (10 μg) control injections to assess airway smooth muscle responsiveness. In the second trial, we measured the bronchoconstrictor response to right heart injection of lactic acid (0.4 mmol kg−1). To minimize the lactic acid injectate volume, the lactic acid dose was delivered in a volume of 0.2 ml in 11 animals. Due to the elevated osmolality of this stimulus (range, 600-2300 mosmol kg−1 due to different animal weights; mean, 1464 ± 167 mosmol kg−1) an additional six animals were studied in which lactic acid was dissolved in 0.4 ml which reduced osmolality to ∼285-950 mosmol kg−1 (mean, 510 ± 57 mosmol kg−1). Solution osmolalities were measured using the freezing point depression method (Osmette A Automatic Analyser, model no. 5002, Precision Instruments Inc.). The pH of 0.2 and 0.4 ml volume lactic acid injections was 2.04 ± 0.03 and 2.22 ± 0.02, respectively (Accumet model 815MP, Fisher Scientific). A second lactic acid challenge was delivered after atropine to assess the reflex contribution of vagal cholinergic efferents to the bronchomotor response.

Effect of capsazepine infusion on capsaicin- and lactic acid-induced reflex bronchoconstriction in the newborn

We first determined whether the putative action of capsazepine at VR1 was capable of abolishing capsaicin-induced reflex bronchoconstriction. Experiments were performed on 11 newborn dogs (mean age, 5.4 ± 0.9 days) in which the bronchomotor responses to right heart injections of capsaicin were measured before, during and after capsazepine infusion. The infusion dosage (500 μg kg−1 min) was derived from previously documented differences in sensitivity to capsaicin-induced bronchoconstriction in the newborn and adult (Anderson & Fisher, 1993), the studies of Lee et al. (1994), and preliminary experiments in our laboratory comparing bolus (3.5-5.0 mg kg−1) injections and infusions of capsazepine (data not shown).

Once we had determined that capsazepine blocked capsaicin-induced bronchoconstriction we tested the hypothesis that lactic acid and capsaicin activate the same vanilloid receptor mechanism in a separate set of experiments (n = 8; mean age, 5 ± 0.4 days). The protocol consisted of five acquisition periods separated by 15 min. The first trial was the same as that described above for the muscarinic blockade study. The second trial measured the response to right heart injection of 25 μg kg−1 capsaicin (8.2 × 10−5 mmol kg−1) or lactic acid (0.4 mmol kg−1 in 0.4 ml). The third trial measured RL and EL,dyn prior to the onset of and during capsazepine infusion (500 μg kg−1 min) into the femoral vein. The fourth trial assessed the response of the lung mechanics to capsaicin and lactic acid 10 min after initiation of the capsazepine infusion. The fifth trial was performed 15-20 min post-capsazepine infusion to assess the reversibility of the capsazepine blockade.

Drugs

The following drugs were used. Chloralose (ICN Biochemicals, Costa Mesa, CA, USA) and urethane (Sigma) dissolved as a mixture (0.25 g chloralose, 2.5 g urethane) in 10 ml heated saline, administered at doses of 2-2.5 ml kg−1 with supplemental injections of 0.5 ml kg−1 to induce and maintain anaesthesia, respectively. A stock solution of capsaicin (Sigma) was prepared by dissolving 10 mg capsaicin in 1 ml ethanol, two drops of Tween 80 and 9 ml saline to arrive at a final concentration of 1 mg ml−1. The stock was diluted further with saline to the required concentration for injection. A stock solution of 3.3 M lactic acid (L(+)lactic acid, Sigma) was diluted with distilled H2O to the required concentration for injection. Acetylcholine chloride (Sigma) was dissolved in saline to a concentration of 50 μg ml−1. Atropine (Sigma) was prepared as a 10 mg ml−1 stock solution and diluted with saline to the required concentration for injection. Capsazepine (RBI) was prepared as a 2.5 mg ml−1 stock solution by dissolving 25 mg in DMSO and diluting it in a solution of 1 ml Tween 80, 1 ml ethanol and 8 ml saline. Injection volumes for capsaicin and ACh were 0.2 ml. Injection volumes for saline were 0.2 or 0.4 ml. Injection volumes for lactic acid were 0.2 or 0.4 ml in the lactic acid/atropine study but 0.4 ml in the capsazepine protocols. Saline, ACh, capsaicin and lactic acid were injected into the jugular catheter dead space then rapidly flushed with saline. Chloralose/urethane and capsazepine were administered via the femoral venous catheter and flushed with saline. All solutions were warmed to 37°C.

Statistical comparisons

Baseline RL and EL,dyn were calculated from the mean of the 10 breaths prior to injection. The peak response for each animal was defined as the mean resistance and elastance calculated for the two largest consecutive values following challenge. RL response latency was defined as the time from jugular line injection to the onset of a maintained or continued increase in RL above baseline. The time to peak was calculated as the time from jugular line injection to the first breath of the maximal response. Heart rate baselines were calculated as the mean values over the 10 s preceding injection. Bradycardia was calculated as the lowest instantaneous heart rate following injection. Statistical comparisons between responses were based on one-way ANOVA, Mann-Whitney rank-sum or Student's t test. Tukey post hoc analyses were performed if the ANOVA was significant. A significant difference was defined as P < 0.05. All values are expressed as means ±s.e.m.

RESULTS

Response of lung mechanics to lactic acid

Baseline mechanics (RL and EL,dyn) values for capsazepine blockade trials are summarized in Table 1. The mean breath-by-breath response of RL and EL,dyn to 0.4 mmol kg−1 lactic acid is shown in Fig. 1 (•). The 0.2 ml lactic acid injectate resulted in a peak increase in RL of 52 ± 6.7% (P < 0.01, Table 2) and the 0.4 ml lactic acid injectate caused a peak increase in RL of 49 ± 10.9% (Table 2). Peak lactic acid-evoked RL increases were not significantly different for 0.2 and 0.4 ml injectate volumes (P > 0.05). Latency and time to peak values for the response of RL to lactic acid are presented in Table 3.

Table 1. Baseline values of lung mechanics.

| Protocol | RL(cmH2O ml−1 s) | EL,dyn(cmH2O ml−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Capsaicin | ||

| Saline | 0.0697 ± 0.005 | 0.9118 ± 0.133 |

| CAPS 1 | 0.0645 ± 0.005 | 0.9530 ± 0.147 |

| CAZP | 0.0774 ± 0.007 | 0.9826 ± 0.143 |

| CAPS 2 | 0.0988 ± 0.009*† | 1.2158 ± 0.174 |

| CAPS 3 | 0.0879 ± 0.006 | 1.0761 ± 0.134 |

| Lactic acid | ||

| Saline | 0.0837 ± 0.008 | 0.7249 ± 0.041 |

| LA 1 | 0.0853 ± 0.005 | 0.7694 ± 0.075 |

| CAZP | 0.0911 ± 0.006 | 0.8086 ± 0.088 |

| LA 2 | 0.0965 ± 0.005 | 0.8788 ± 0.076 |

| LA 3 | 0.1059 ± 0.010 | 0.8329 ± 0.080 |

RL, inspiratory lung resistance; EL,dyn, dynamic lung elastance; CAPS, capsaicin; CAZP, capsazepine; LA, lactic acid.

Significantly different from saline (P < 0.05)

significantly different from CAPS 1 (P < 0.05). Values are means ± S.E.M.

Figure 1. Breath-by-breath response of pulmonary mechanics to lactic acid pre- and post-atropine.

Mean (±s.e.m.) breath-by-breath values of percentage change in lung resistance (RL, upper panels) and elastance (EL,dyn, lower panels) in response to right heart injections of lactic acid (0.4 mmol kg−1) in 0.2 ml (high osmolality; left panels) or 0.4 ml (low osmolality; right panels) injectate volumes before (•) and after (○) atropine (2 mg kg−1). Note that atropine abolished the response to the 0.4 ml injectate whereas the 0.2 ml injectate was atropine resistant. Arrows indicate injection of lactic acid. Mean ventilator frequency was approximately 45 breaths min−1.

Table 2. Lung mechanics: lactic acid/atropine study.

| Raw baseline values | Maximum response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic acid(0.4 mmol kg−1) | RL(cmH2O ml−1 s) | EL,dyn(cmH2O ml−1 s) | RL(% change) | EL,dyn(% change) |

| 0.2 ml injectate | ||||

| Saline | 0.093 ± 0.010 | 0.821 ± 0.08 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| Intact | 0.097 ± 0.0003 | 1.353 ± 0.002 | 51.6 ± 6.7* | 31.7 ± 2.6* |

| Post-atropine | 0.084 ± 0.001 | 1.398 ± 0.002 | 30.9 ± 3.9† | 26.4 ± 4.6 |

| 0.4 ml injectate | ||||

| Saline | 0.101 ± 0.008 | 0.779 ± 0.117 | 3.2 ± 2.0 | 0.1 ± 0.2 |

| Intact | 0.100 ± 0.001 | 1.171 ± 0.004 | 49.2 ± 10.9* | 25.0 ± 4.5* |

| Post-atropine | 0.091 ± 0.001 | 1.210 ± 0.004 | 10.6 ± 4.0† | 13.9 ± 4.0 |

RL, inspiratory lung resistance; EL,dyn, dynamic lung elastance.

Significantly different from saline (P < 0.05)

significantly different from intact (P < 0.05). Values are means ± S.E.M.

Table 3. Latency of lung resistance response to lactic acid.

| Intact | Atropine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic acid | Latency(s) | Time to peak(s) | Latency(s) | Time to peak(s) |

| 0.2 ml injectate | 6.8 ± 1.2 | 18.7 ± 2.7 | 9.5 ± 1.6 | 21.9 ± 2.0 |

| 0.4 ml injectate | 8.4 ± 2.1 | 26.3 ± 6.0* | n. a. | n. a. |

Significantly different from 0.2 ml injectate time to peak (P < 0.05); n.a. not applicable. Values are means ± S.E.M.

The mean breath-by-breath response of RL and EL,dyn to lactic acid during muscarinic blockade with atropine is shown in Fig. 1 (○). The maximal response of RL to the 0.2 ml lactic acid injectate was relatively atropine resistant (Table 2), displaying a reduction of only 33 ± 13.5% from the control value (P < 0.05). In contrast, the maximal RL responses associated with the 0.4 ml lactic acid injectate (Table 2) were atropine sensitive and were reduced by 80 ± 10.9% compared with intact (P < 0.01). The effect of atropine antagonism on the response of RL was significantly different (P < 0.01) between the 0.2 and 0.4 ml lactic acid injectate volumes.

In a few animals (n = 3) we measured the reduction in pH in a single arterial blood sample obtained within 30 s of lactic acid injection. Lactic acid decreased arterial pH to 7.30 ± 0.02.

Response of lung mechanics during capsazepine infusion

Capsazepine infusion alone was associated with an increase in RL of 23 ± 6.7% at 8 min (Fig. 2). At this time, inflation to ∼20 cmH2O did reduce the peak transpulmonary pressure (PTP) swings. However, by 2 min after inflation RL was again significantly elevated above the pre-capsazepine infusion value (18 ± 0.6%, P < 0.05). By comparison, 8 min of tidal breathing following inflation, without any intervention, was associated with an increase in RL of ∼11% relative to control. Additionally we found in preliminary studies that infusion of capsazepine vehicle alone did not alter the RL response to lactic acid (RL = 68 and 61% prior to and following capsazepine vehicle, respectively). Thus, capsazepine appeared to have a partial agonist effect.

Figure 2. Acute breath-by-breath response of mean lung resistance to capsazepine infusion.

Mean lung resistance response to capsazepine (500 μg kg−1 min i.v.) in 17 newborn dogs. Infusion of capsazepine caused an increase in inspiratory lung resistance (RL) that was only transiently reduced by inflation to 20 cmH2O. Arrow indicates onset of capsazepine infusion.

Figure 3 shows raw tracings from a typical animal in which capsaicin-induced increases in PTP were abolished by capsazepine infusion. The mean breath-by-breath response of RL to right heart injection of capsaicin for 11 animals is shown in Fig. 4. Capsaicin caused a maximal increase of 41 ± 8.5% in RL (Fig. 5). During capsazepine infusion, the maximal response of RL to capsaicin was inhibited by 83 ± 4.7% (P < 0.01), indicating that competitive antagonism of the capsaicin/VR1 receptor effectively blocks reflex bronchoconstriction. Fifteen minutes following capsazepine infusion the response of RL to capsaicin had recovered to 71 ± 21.9% of the intact response (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5).

Figure 3. Cardiopulmonary response to capsaicin pre- and post-capsazepine.

Typical cardiopulmonary response in a single animal (4 days old) illustrating the antagonistic effect of capsazepine (500 μg kg−1 min i.v.) on reflex responses to right heart injection of capsaicin (CAPS, 25 μg kg−1). Transpulmonary pressure (PTP), flow (V̇), tidal volume (VT) and arterial blood pressure (BP) before (upper panels) and during (lower panels) capsazepine infusion. The bronchoconstrictor response is indicated by the increase in PTP and is accompanied by hypotension and bradycardia. Single cardiac arrhythmias associated with capsaicin injection and flush probably indicate an acute effect of bolus injection on the myocardium. During capsazepine infusion the PTP and cardiovascular responses were abolished.

Figure 4. Breath-by-breath response of pulmonary mechanics to capsaicin.

Mean (±s.e.m.) breath-by-breath values of percentage change in inspiratory lung resistance (RL) and dynamic lung elastance (EL,dyn) in response to right heart injections of capsaicin (arrows) in 11 newborn dogs for three separate conditions: Intact (left panels), right heart injection of capsaicin caused a brisk bronchoconstrictor response; Capsazepine (middle panels), capsaicin response blocked by capsazepine infusion; Recovery (right panels), partial recovery of the capsaicin response 15-20 min after termination of capsazepine infusion.

Figure 5. Mean peak change in response of pulmonary mechanics to capsaicin.

Mean peak responses (±s.e.m.) of inspiratory lung resistance (RL, top panel) and dynamic lung elastance (EL,dyn, bottom panel) plotted as percentage change from baseline for saline and three different capsaicin injections (Intact, Block (capsazepine) and Recovery). Peak response values are slightly greater than the breath-by-breath data due to variability for the ventilator cycle at which the maximal response occurred. † Significantly different from Intact capsaicin response; * significant difference from Saline control. P < 0.05 (ANOVA and Tukey post hoc).

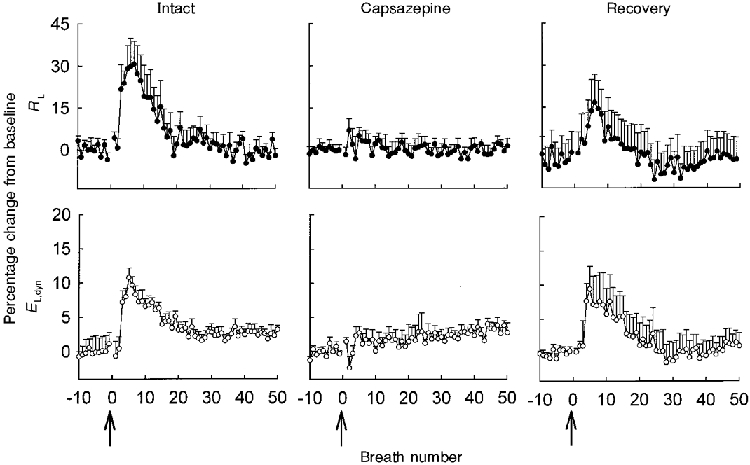

The mean breath-by-breath response of RL and EL,dyn to 0.4 ml lactic acid injectate (low osmolality) before, during and after capsazepine is shown in Fig. 6. Lactic acid caused a maximal increase of 50 ± 7.0% in RL (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7) but, in contrast to capsaicin (see above), the lactic acid-induced increase in RL was unaffected by capsazepine infusion (39 ± 5.7%, P > 0.05; Fig. 6 and Fig. 7). At 15 min following capsazepine infusion the response of RL to lactic acid was 95 ± 13.7% of the intact response. RL response latencies and times to peak for capsaicin and lactic acid are summarized in Table 4. Heart rate responses are summarized in Table 5.

Figure 6. Breath-by-breath response of pulmonary mechanics to lactic acid.

Mean response of lung mechanics to lactic acid (0.4 mmol kg−1) in 8 newborn dogs. Mean (±s.e.m.) breath-by-breath values of percentage change in inspiratory lung resistance (RL, upper panels) and dynamic lung elastance (EL,dyn, lower panels) in response to right heart injections of lactic acid (arrows) for three separate conditions. Right heart injection of lactic acid caused a robust bronchoconstrictor response (Intact, left panels) that was maintained during capsazepine infusion (500 μg kg−1 min; Capsazepine, middle panels) and post-capsazepine (Recovery, right panels).

Figure 7. Mean peak response of pulmonary mechanics to lactic acid.

Mean peak response (±s.e.m.) of inspiratory lung resistance (RL, top panel) and dynamic lung elastance (EL,dyn, bottom panel) plotted as percentage change from baseline for saline and three different lactic acid responses (Intact, Block (capsazepine) and Recovery). Responses to lactic acid were all significantly different from response to saline (P < 0.05) but not from each other (P > 0.05). * Significant difference from Saline control (P < 0.05).

Table 4. Latency and time to peak for lung resistance response.

| Intact | Capsazepine | Recovery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol | Latency(s) | Time to peak(s) | Latency(s) | Time to peak(s) | Latency(s) | Time to peak(s) |

| CAPS | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 6.4 ± 1.0 | n. a. | n. a. | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 6.2 ± 1.0 |

| ACh | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 10.5 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 12.5 ± 2.2 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 9.7 ± 0.9 |

| LA | 5.2 ± 1.7 | 17.8 ± 3.1*† | 8.2 ± 1.8 | 21.6 ± 3.7† | 4.8 ± 1.8 | 19.2 ± 4.5*† |

Significantly different from CAPS (P < 0.05)

significantly different from ACh (P < 0.05); n.a., not applicable. Values are means ± S.E.M.

Table 5. Heart rate summary: capsazepine protocol.

| Intact | Capsazepine | Recovery | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Challenge | Baseline(bpm) | Decrease(%) | Latency(s) | Baseline(bpm) | Decrease(%) | Latency(s) | Baseline(bpm) | Decrease(%) | Latency(s) |

| Saline | 185.2 ± 4.4 | 4.3 ± 1.1* | 4.0 ± 0.3 | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. |

| CAPS | 205.6 ± 6.3 | 8.0 ± 2.9*‡ | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 207.7 ± 5.8 | 6.4 ± 2.4* | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 214.6 ± 9.3 | 5.4 ± 3.1* | 4.6 ± 1.9 |

| LA | 180.6 ± 5.6 | 31.1 ± 7.8*†‡ | 6.8 ± 2.8 | 207.4 ± 5.5 | 33.3 ± 10.4*† | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 212.9 ± 11.9 | 36.1 ± 8.5*† | 8.6 ± 3.8 |

bpm, beats per minute.

Significantly different from baseline value (P < 0.05)

significantly different from capsaicin (P < 0.05)

significantly different from saline (P < 0.05); n. a., not applicable. Values are means ± S.E.M.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that lactic acid evokes an atropine-sensitive increase in bronchomotor tone that is consistent with that described for other stimulants of C fibre afferents (Coleridge et al. 1989). Our study also found that capsazepine, the competitive capsaicin/VR1 receptor antagonist, significantly attenuates the bronchomotor reflex response to capsaicin, but not the response to lactic acid. Taken together these results indicate that lactic acid does not act as an endogenous VR1 ligand, but suggest that lactic acid and capsaicin stimulate reflex bronchoconstriction via different receptor signal transduction mechanisms.

In both the adult and neonate, activation of pulmonary C fibres by the vanilloid excitotoxin capsaicin evokes reflex bronchoconstriction (Coleridge et al. 1989; Anderson & Fisher, 1993), which is variably accompanied by mucus hypersecretion, vascular exudation and airway oedema (Lundberg & Saria, 1982; Coleridge et al. 1989). Physiological stimulation of pulmonary C fibres initiates airway reflexes aimed at limiting exposure of the airways to noxious stimuli (as reviewed in Coleridge & Coleridge, 1994; Paintal, 1973; Karlsson et al. 1988); however, activation of pulmonary C fibres has also been implicated in the airway hyper-reactivity accompanying inflammatory lung diseases such as asthma or, in the newborn, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (Barnes, 1986). The magnitude of the bronchoconstriction we observed to both capsaicin and lactic acid is submaximal (Fisher et al. 1990) and may reflect a mechanism to enhance gas exchange by reducing dead space volume (Widdicombe, 1963) or a mechanism to protect the highly compliant airways of the newborn from dynamic compression (Bhutani et al. 1986).

Despite characterization of the in vivo reflex effects of capsaicin, the effects of capsaicin on pulmonary C fibres and elucidation of the molecular mechanism of action of the putative C fibre ‘capsaicin’ receptor (i.e. VR1), the endogenous VR1 ligand remains to be identified. The probable activation of pulmonary C fibres during inflammatory conditions has led to the proposal that biological compounds released in the inflammatory process, including lactic acid, may represent endogenous agonists for the capsaicin receptor (Bevan & Geppetti, 1994; Franco-Cereceda et al. 1994). Acidic pH has been shown to evoke a capsazepine-sensitive decrease in tidal volume in the isolated perfused guinea-pig lung, presumably by acting directly on C fibre endings to cause release of tachykinins (Lou & Lundberg, 1992). The ability of lactic acid to act as a physiological stimulant of reflex bronchoconstriction in vivo, however, had not been tested despite its excitatory actions on C fibres and its ability to elicit changes in the pattern of breathing (Trenchard, 1986; Lee et al. 1996).

The newborn is particularly interesting with respect to the potential actions of H+ on C fibres since metabolic and respiratory acidosis are routinely seen at parturition as well as in certain pathological complications of birth (Koch & Wendel, 1968). Initial studies in the newborn led to the conclusion that lactic acid (0.25 mmol kg−1) does not evoke a bronchoconstrictor response in 1-6 day old rabbit kittens (Ducros & Trippenbach, 1991). In our study we directly measured total pulmonary resistance following presumptive C fibre stimulation with doses of lactic acid that were comparable to those of Ducros & Trippenbach (1991) and found that lactic acid caused a robust, cholinergic, reflex bronchoconstriction in the newborn dog. While the discrepancy between the findings of Ducros & Trippenbach (1991) and those described in this paper could be attributable to species differences, other factors are equally possible. Ducros & Trippenbach (1991) used the ratio of tidal volume to oesophageal pressure swing (i.e. dynamic lung compliance, CL,dyn) to monitor changes in bronchomotor tone. CL,dyn is a reasonable index of bronchoconstriction but it may be insensitive to small changes in airway smooth muscle tone or resistance (Widdicombe, 1963). Furthermore, CL,dyn is constrained in its relative response since it can decrease only in the range of 100-0% of the control value, whereas RL can increase severalfold above control. Indeed, this was why we calculated EL,dyn. In preliminary experiments we found that right heart injection of 0.2 mmol kg−1 lactic acid evoked modest but distinct and quantifiable bronchoconstrictor responses in the newborn dog (8% increase in RLversus a 5% decrease in CL,dyn). The small CL,dyn response associated with 0.25 mmol kg−1 lactic acid may have made bronchoconstriction more difficult to detect with the dynamic compliance measurements of previous studies. Alternatively, 0.2-0.25 mmol kg−1 may be inadequate to stimulate C fibres in the newborn rabbit sufficiently, which is more immature at birth than the dog.

The atropine resistance of the bronchoconstriction evoked by the 0.2 ml lactic acid injectate suggests a non-cholinergic component to this response. The atropine-resistant bronchoconstrictor effects of the high osmolality lactic acid injectate were not likely to be due to C fibre stimulation since hypertonic saline solutions (2400–4800 mmol l−1 saline) injected into the pulmonary circulation of adult dogs cause pulmonary C fibre-induced reflex bronchoconstriction via cholinergic mechanisms (Pisarri et al. 1991). Furthermore, in preliminary experiments, injection of saline at twice our highest lactic acid osmolality (5000 mosmol kg−1) had no bronchoconstrictor action in 12-14 day old dogs. Thus, it appears that high osmolality per se has an as yet undetermined non-muscarinic mechanism of increasing airway tone in the newborn dog.

Release of tachykinins from C fibre terminals mediates potent bronchoconstriction in certain species (e.g. guinea-pig) (Coleridge et al. 1989). Tachykinins also stimulate pulmonary rapidly adapting receptors (RARs) (Matsumoto et al. 1997), which can in turn evoke reflex bronchoconstriction (Coleridge et al. 1989). This mechanism is precluded in our study due to the apparent absence of tachykinins in canine C fibre terminals (Russell, 1980; Fisher et al. 1990). Additionally, spontaneous RAR activity in the newborn dog is very sparse, suggesting that reflex responses may also be limited (Fisher & Sant'Ambrogio, 1982).

Development of the competitive C fibre receptor antagonist capsazepine allowed us specifically to investigate the putative mechanism of C fibre activation with lactic acid. Despite several encouraging studies (Bevan et al. 1992; Lee & Lundberg, 1994; Fox et al. 1995; Lee et al. 1996), to our knowledge the effect of capsazepine on capsaicin-evoked reflex bronchoconstriction had not been investigated prior to our study. The capsazepine sensitivity of the capsaicin-evoked bronchoconstriction in vivo (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5) supports the notion that therapeutic targeting of sensory afferents in the newborn may be a beneficial strategy for reducing the cholinergic reflex component accompanying inflammatory lung disease. This would leave beneficial actions of cholinergic efferents, such as protection of the airways from collapse during cough, intact while removing detrimental actions of C fibre stimulation. Others have suggested targeting of C fibre afferents would be beneficial for reducing potential tachykinin components of the bronchomotor response, as seen in some species with C fibre activation (Barnes, 1986; Spina & Page, 1996; Szallasi & Blumberg, 1996).

In contrast to capsaicin-evoked bronchoconstriction, lactic acid-induced bronchomotor reflexes were essentially unchanged by capsazepine (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7). The capsazepine resistance of the lactic acid-evoked bronchomotor response indicates that lactic acid and capsaicin stimulate reflex bronchoconstriction either via different signal transduction mechanisms within the same pulmonary C fibre afferent, or via different pulmonary C fibre subpopulations. The signal transduction mechanisms causing these effects are presumably mediated by VR1 for capsaicin (Caterina et al. 1997) and by a separate mechanism for lactic acid (Akaike et al. 1990; Bevan & Yeats, 1991), possibly an acid-sensing ionic channel (ASIC) (Waldmann et al. 1997). Evidence is available to support either polymodal or distinct C fibre responses; the same C fibres are stimulated by capsaicin and lactic acid in adult rat (Lee et al. 1996; Hong et al. 1997). In contrast, Pedersen et al. (1998) have suggested that C fibres may have separate sensory modalities that may also be anatomically segregated in terms of their cell body location. VR1 has also been demonstrated to be sensitive to both capsaicin and H+ when the receptor is expressed in mammalian cells (Tominaga et al. 1998) but not Xenopus oocytes (Caterina et al. 1997). Acidic extracellular pH below the threshold required to activate VR1 facilitates capsaicin-induced cation current in both cell types (Caterina et al. 1997; Vyklicky et al. 1998; Tominaga et al. 1998).

Others have alluded to the potential role of additional inflammatory compounds as endogenous stimulants of VR1 (Shams et al. 1988; Vyklicky et al. 1998). The capsazepine insensitivity of the lactic acid response, combined with the long latency and time to peak of the bronchomotor response to lactic acid (Table 3 and Table 4), could reflect a lactic acid-induced metabolic intermediary that activates pulmonary C fibre receptors. Possible intermediaries include products of the cyclo-oxygenase pathway of arachadonic acid metabolism such as thromboxane A2 and prostaglandin E2 (Shams et al. 1988; Coleridge et al. 1989; Lee & Morton, 1995; Steen et al. 1996). Whether cyclo-oxygenase products play a role in the newborn dog's response to lactic acid is untested, although it appears unlikely. For example, Lee et al. (1996) concluded that cyclo-oxygenase intermediaries were not involved in the lactic acid-induced pulmonary chemoreflex in the rat as lactic acid-evoked apnoea, bradycardia and hypotension were unaffected by pretreatment with indomethacin (Lee & Morton, 1995; Lee et al. 1996). In a single animal, we assessed the effect of indomethacin (15 mg kg−1) and found that it did not attenuate the bronchomotor response to lactic acid (data not shown), supporting the conclusion of Lee et al. (1996).

In summary, our findings show a clear separation of the mechanisms with respect to capsaicin- and lactic acid-evoked bronchoconstrictor reflexes in vivo (Fig. 8). We conclude that lactic acid behaves as a physiological C fibre stimulant to cause reflex bronchoconstriction. Further, capsazepine reversibly antagonizes the reflex bronchoconstriction elicited by right heart injections of capsaicin, presumably by acting at the C fibre capsaicin/VR1 receptor, whereas the capsazepine resistance of the lactic acid-induced airway response indicates that lactic acid acts via an independent mechanism to evoke reflex bronchoconstriction.

Figure 8. Possible mechanisms of activation of C fibre receptors by H+.

Hypotheses for the activation of pulmonary C fibres with capsaicin and lactic acid. Capsazepine was effective in abolishing the VR1 receptor-mediated response to capsaicin but did not affect the lactic acid-evoked response. Our data suggest that C fibres are stimulated by at least two parallel receptor transduction mechanisms. The first, VR1, binds vanilloid compounds (i.e. capsaicin, resiniferatoxin), and has been suggested to display a secondary putative recognition site for H+ that facilitates or amplifies the response to capsaicin (Caterina et al. 1997; Vyklicky et al. 1998). H+ alone appears to be only a weak stimulant of this receptor when it is expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Caterina et al. 1997) but potentiates the response evoked by both vanilloids (Caterina et al. 1997; Tominaga et al. 1998) and inflammatory mediators (specifically prostaglandin E2) (Vyklicky et al. 1998). H+ does cause activation of VR1 expressed in human embryonic kidney cells (Tominaga et al. 1998) but our data suggest that this may not be so for pulmonary C fibres. The second receptor transduction mechanism, ASIC (acid-sensing ionic channel), is a H+-gated channel (Waldmann et al. 1997) possibly with a secondary recognition site for the lactate anion that reflects the reported ability of the lactate anion to enhance the H+ response (Hong et al. 1997). ASM, airway smooth muscle; BV, blood vessel; CAPS, capsaicin; CAZP, capsazepine; LA, lactic acid.

Acknowledgments

Supported by an operating grant from the Medical Research Council of Canada and the Ontario Thoracic Society (OTS). M. A. N. was supported by an OTS Graduate Studentship and a Queen's Graduate Award.

References

- Abman SH, Groothius JR. Pathophysiology and treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Respiratory Medicine. 1994;41:277–295. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38726-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaike N, Krishtal OA, Maruyama T. Proton-induced sodium current in frog isolated dorsal root ganglion cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1990;63:805–813. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.4.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JW, Fisher JT. Capsaicin-induced reflex bronchoconstriction in the newborn. Respiration Physiology. 1993;93:13–27. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(93)90064-h. 10.1016/0034-5687(93)90064-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Asthma as an axon reflex. Lancet i (8475) 1986:242–245. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvisi MG, Miura M, Stretton D, Barnes PJ. Capsazepine as a selective antagonist of capsaicin-induced activation of C-fibres in guinea-pig bronchi. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;215:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan S, Geppetti P. Protons: small stimulants of capsaicin-sensitive sensory nerves. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:509–512. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan S, Hothi S, Hughes G, James IF, Rang HP, Shah K, Walpole CSJ, Yeats JC. Capsazepine: a competitive antagonist of the sensory neurone excitant capsaicin. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;107:544–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb12781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan S, Yeats J. Protons activate a cation conductance in a sub-population of rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;433:145–161. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutani VK, Koslo RJ, Shaffer TH. The effects of tracheal smooth muscle tone on neonatal airway collapsibility. Pediatric Research. 1986;20:492–495. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198606000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The CAPS receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge HM, Coleridge JCG. Pulmonary reflexes: neural mechanisms of pulmonary defense. Annual Review of Physiology. 1994;56:69–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge HM, Coleridge JCG, Schultz HD. Afferent pathways involved in reflex regulation of airway smooth muscle. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1989;42:1–63. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(89)90021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge JC, Coleridge HM. Afferent vagal C fibre innervation of the lungs and airways and its functional significance. Reviews of Physiology Biochemistry and Pharmacology. 1984;99:1–110. doi: 10.1007/BFb0027715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickenson AH, Dray A. Selective antagonism of CAPS by capsazepine: evidence for a spinal receptor site in capsaicin-induced antinociception. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1991;104:1045–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducros G, Trippenbach T. Respiratory effects of lactic acid injected into the jugular vein of newborn rabbits. Pediatric Research. 1991;29:548–552. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199106010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JT, Brundage KL, Waldron MA, Connelly BJ. Vagal cholinergic innervation of the airways in newborn cat and dog. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1990;69:1525–1531. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.4.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JT, Mortola JP. Statics of the respiratory system and growth: an experimental and allometric approach. American Journal of Physiology. 1981;241:R336–341. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1981.241.5.R336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JT, Sant'Ambrogio G. Location and discharge properties of respiratory vagal afferents in the newborn dog. Respiration Physiology. 1982;50:209–220. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(82)90019-6. 10.1016/0034-5687(82)90019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AJ, Urban L, Barnes PJ, Dray A. Effects of capsazepine against capsaicin- and proton-evoked excitation of single airway C-fibres and vagus nerve from the guinea-pig. Neuroscience. 1995;67:741–752. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00115-y. 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00115-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Cereceda A, Kallner G, Lundberg JM. Cyclo-oxygenase products released by low pH have capsaicin-like actions on sensory nerves in the isolated guinea pig heart. Cardiovascular Research. 1994;28:365–369. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JL, Kwong K, Lee LY. Stimulation of pulmonary C fibres by lactic acid in rats: contributions of H+ and lactate ions. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:319–329. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J-A, Sant'Ambrogio G, Widdicombe JG. Afferent neural pathways in cough and reflex bronchoconstriction. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1988;65:1007–1023. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.3.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G, Wendel H. Adjustment of arterial blood gases and acid base balance in the normal newborn infant during the first week of life. Biology of the Neonate. 1968;12:136–161. doi: 10.1159/000240100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L-Y, Lundberg JM. Capsazepine abolishes pulmonary chemoreflexes induced by CAPS in anesthetized rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994;76:1848–1855. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.5.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L-Y, Morton RF. Pulmonary chemoreflex sensitivity is enhanced by prostaglandin E2 in anesthetized rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1995;79:1679–1686. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.5.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LY, Morton RF, Lundberg JM. Pulmonary chemoreflexes elicited by intravenous injection of lactic acid in anesthetized rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1996;81:2349–2357. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.6.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y-P, Lundberg JM. Inhibition of low pH evoked activation of airway sensory nerves by capsazepine, a novel capsaicin-receptor antagonist. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1992;189:537–544. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91591-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg JM, Saria A. Bronchial smooth muscle contraction induced by stimulation of capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1982;116:473–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1982.tb07170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S, Takeda M, Saiki C, Takahashi T, Ojima K. Effects of tachykinins on rapidly adapting pulmonary stretch receptors and total lung resistance in anesthetized, artificially ventilated rabbits. Journal of Pharmacological and Experimental Therapeutics. 1997;283:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okanlami OA, Fryer AD, Hirshman CA. Interaction of nondepolarizing muscle relaxants with M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in guinea pig heart and lung. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:155–161. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199601000-00018. 10.1097/00000542-199601000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paintal AS. Vagal sensory receptors and their reflex effects. Physiological Reviews. 1973;53:159. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1973.53.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen KE, Meeker SN, Riccio MM, Undem BJ. Selective stimulation of jugular ganglion afferent neurons in guinea pig airways by hypertonic saline. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1998;84:499–506. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisarri TE, Jonzon A, Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC. Intravenous injection of hypertonic NaCl solution stimulates pulmonary C-fibres in dogs. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:H1522–1530. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.5.H1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA. Innervation of airway smooth muscle in the dog. Bulletin European de Physiopathologie Respiratoire. 1980;16:671–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shams H, Peskar BA, Scheid P. Acid infusion elicits thromboxane A2-mediated effects on respiration and pulmonary hemodynamics in the cat. Respiration Physiology. 1988;71:169–183. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(88)90014-x. 10.1016/0034-5687(88)90014-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina D, Page CP. Airway sensory nerves in asthma - targets for therapy? Pulmonary Pharmacology. 1996;9:1–18. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1996.0001. 10.1006/pulp.1996.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl GL, Longhurst JC. Ischemically sensitive visceral afferents: importance of H+ derived from lactic acid and hypercapnia. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:H748–753. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.3.H748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen KH, Steen AE, Kreysel HW, Reeh PW. Inflammatory mediators potentiate pain induced by experimental tissue acidosis. Pain. 1996;66:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03034-5. 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid receptors: new insights enhance potential as a therapeutic target. Pain. 1996;68:195–208. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03202-2. 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Blumberg PM, Lundberg JM. Proton inhibition of [3H]resiniferatoxin binding to vanilloid (capsaicin) receptors in rat spinal cord. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;289:181–187. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(95)90093-4. 10.1016/0922-4106(95)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenchard D. CO2/H+ receptors in the lungs of anaesthetized rabbits. Respiration Physiology. 1986;63:227–240. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(86)90116-7. 10.1016/0034-5687(86)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban L, Dray A. Capsazepine, a novel CAPS antagonist, selectively antagonises the effects of CAPS in the mouse spinal cord in vitro. Neuroscience Letters. 1991;134:9–11. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90496-g. 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90496-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyklicky L, Knotkova-Urbancova H, Vitaskova Z, Vlachova V, Kress M, Reeh PW. Inflammatory mediators at acidic pH activate capsaicin receptors in cultured sensory neurons from newborn rats. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:670–676. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Champigny G, Bassilana F, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. A proton-gated cation channel involved in acid-sensing. Nature. 1997;386:173–177. doi: 10.1038/386173a0. 10.1038/386173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe JG. Regulation of tracheobronchial smooth muscle. Physiological Reviews. 1963;43:1–37. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1963.43.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]