Abstract

In cell-attached patches formed on the apical membrane of fetal alveolar epithelium, terbutaline (a specific β2-adrenergic agonist) increased the open probability (Po) of an amiloride-sensitive Na+-permeable non-selective cation (NSC) channel (control, 0.03 ± 0.04; terbutaline, 0.62 ± 0.18; n = 8, P < 0.00001) by increasing the mean open time 100-fold without any significant change in the mean closed time and without any change in the single channel conductance (control, 27.8 ± 2.3 pS; terbutaline, 28.2 ± 2.1 pS; n = 8).

The Po of the unstimulated channel increased when the apical membrane was depolarized due to a decrease in the closing rate and an increase in the opening rate, while the Po of the terbutaline-stimulated channel did not depend on the membrane potential.

Increased cytosolic [Ca2+] also increased the Po of the channel in a manner consistent with one Ca2+-binding site on the cytosolic surface of the channel. Terbutaline increased the sensitivity of the channel to cytosolic Ca2+ by shifting the concentration of cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c) required for half-maximal activation to a lower [Ca2+]c value, leading to an increase in Po.

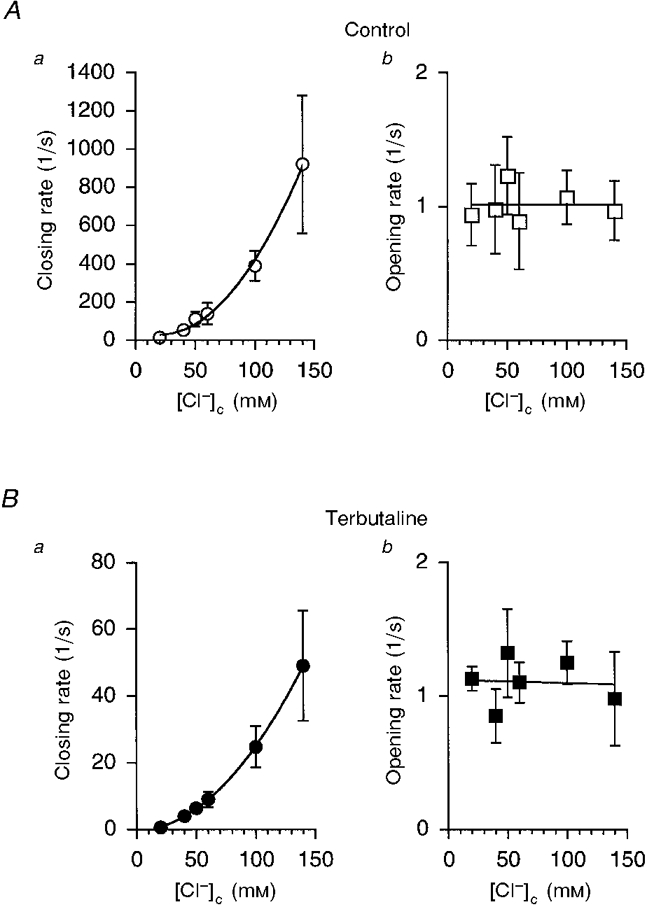

An increase in the cytosolic Cl− concentration ([Cl−]c) decreased the Po of the channel consistent with two Cl−-binding sites by increasing the closing rate without any significant change in the opening rate. Terbutaline increased Po by reducing the effect of cytosolic Cl− to promote channel closing.

Taken together, these observations indicate that terbutaline activates a Ca2+-activated, Cl−-inhibitable, amiloride-sensitive, Na+-permeable NSC channel in fetal rat alveolar epithelium in two ways: first, through an increase in Ca2+ sensitivity, and second, through a reduction in the effect of cytosolic Cl− to promote channel closing.

It is well known that the fetal lung epithelium secretes fluid into the lumen of the lung throughout gestation (for review see O'Brodovich, 1991; Kemp & Olver, 1996). The fetal lung fluid plays an important role in development, differentiation and growth of the fetal lung. On the other hand, this fluid must be cleared from alveolar air spaces immediately after birth to allow normal gas exchange. Fluid clearance at birth appears to be enhanced by β2-adrenergic stimulation of the alveolar epithelium (Brown et al. 1983). β2-Adrenergic agonists promote lung fluid clearance by stimulating amiloride-sensitive Na+ absorption (Olver et al. 1981; O'Brodovich et al. 1990a, b). Epithelial Na+ channels (ENaCs) similar to those first cloned from rat colon (Canessa et al. 1993, 1994) appear to play a critical role in lung liquid clearance at birth (Hummler et al. 1996).

There have been two types of Ca2+-activated, amiloride-blockable Na+-permeable channel described in fetal rat alveolar epithelium; one is a non-selective cation (NSC) channel with a single channel conductance of 28 pS, and the other is a Na+ channel with a single channel conductance of 12 pS (Marunaka, 1996). However, only the 28 pS NSC channel responds to β2-adrenergic stimulation implying that β2-adrenergic agonists stimulate the amiloride-sensitive Na+ absorption by activating the 28 pS NSC channel (Marunaka, 1997a; Marunaka & Niisato, 1999). We have previously reported that cytosolic Ca2+ and terbutaline, a β2-adrenergic agonist, increase the open probability (Po) of the 28 pS NSC channel (Marunaka et al. 1992; Tohda et al. 1994) and that cytosolic Cl− has an inhibitory action on the channel (Tohda et al. 1994). However, the gating mechanism by which β2-adrenergic agonists stimulate the NSC channel is still unknown. Further, how cytosolic Ca2+ and Cl− affect the gating kinetics of the channel is also unknown. Moreover, there is no information as to how the interaction between β2-adrenergic agonists and cytosolic Ca2+ and Cl− affects the gating kinetics of the channel. To provide a complete understanding of the mechanism of β2-adrenergic agonist-induced activation and the roles of cytosolic Ca2+ and Cl− in this activation, it is necessary to study the basic gating kinetics of the channel and the mechanisms by which β2-adrenergic agonists, cytosolic Ca2+ and Cl− affect the gating kinetics. To clarify the gating mechanism by which β2-adrenergic agonists stimulate the NSC channel and cytosolic Ca2+ and Cl− affect gating, we used single channel recording methods, which led us to the conclusion that: (1) the NSC channel has one Ca2+-binding site and two Cl−-binding sites, (2) β2-adrenergic agonists increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of the NSC channel and decrease the sensitivity to cytosolic Cl− that normally inhibits the activity of the NSC channel without any change in the number of Ca2+- or Cl−-binding sites, and (3) cytosolic Cl− decreases Po by promoting channel closing without any effect on the channel's residency in the closed state.

METHODS

Cell culture

Fetal rat type II pneumocytes were isolated from the fetuses of pregnant Wistar rats (gestational age, 20 days (term, 22 days)). The rats were anaesthetized with inhalational ether (overdose) for 15 min. Following anaesthetization, we determined that there was no response to tactile stimulation, that respiration had ceased and that there was no heart beat. When we had confirmed, using these criteria, that the rats were dead, the fetuses were removed from the uterus. Under the above conditions, the fetuses had also been killed, i.e. there were no responses to tactile stimuli, respiration had ceased and no heart beats were observed. Distal lung epithelial cells were harvested from the fetuses and grown in primary culture according to the methods described previously (Marunaka, 1996). In brief, rat lungs were excised from 20 days gestation Wistar rat fetuses and minced into 1 mm3 pieces. The lung fragments were incubated at 37°C with 0.125 % trypsin and 0.002 % DNase and dissociated cells were then passed through a Nitex-100 mesh filter (B. and S. H. Thompson, Scarborough, Ontario, Canada). The cells were then incubated in 0.1 % collagenase and purified using differential adhesion techniques. The majority of these cells are known to have morphological and biochemical characteristics of type II alveolar epithelial cells (Post et al. 1984; Post & Smith, 1988). The harvested epithelial cells were immediately seeded (1 × 106 cells cm−2) onto translucent porous Nunc filter inserts (Nunc Tissue Culture Inserts, Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). All cells were grown in minimum essential medium with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 100 u ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 95 % air-5 % CO2 environment. These epithelia were subsequently used 2 or 3 days after seeding under confluent conditions for patch clamp experiments. Cells plated on permeable supports formed polarized monolayers with their apical surfaces upward (Hagiwara et al. 1992; Ito et al. 1997; Ding et al. 1998).

The procedures used complied with the principles and guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and had institutional ethical approval (Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute).

Chemicals and solutions

The bathing and pipette solutions used in experiments in the cell-attached configuration contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes (pH 7.4). In excised inside-out configuration the pipette solution contained (mM): 145 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes (pH 7.4). When the effects of cytosolic Ca2+ and Cl− on channel activity were studied in excised inside-out patches, bathing solutions used contained (mM): 145 K+, 1 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes, with various Ca2+ and Cl− concentrations (pH 7.4). To reduce the cytosolic Cl− concentration ([Cl−]c), Cl− was replaced with gluconate unless otherwise indicated. The Ca2+ (free calcium) concentration was adjusted using known CaCl2 and EGTA (10 mM as pure EGTA) concentrations, calculated using pKd (−log of dissociation constant) values of 10.86 for EGTA4− and 5.25 for HEGTA3−. The free calcium concentration in the solution, which should be equal to or less than 1 μM, was finally determined using the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye fura-2 (Empix Imaging Incorporation, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) with a computer program, Image-1 (Universal Imaging Corporation, West Chester, PA, USA) (Foskett & Melvin, 1989). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise indicated.

Application of terbutaline

In general, 10 μM terbutaline was applied from the basolateral side. In experiments in the cell-attached configuration, channel activity was recorded from the same patch before and 30 min after application of 10 μM terbutaline while the patch was maintained. When the effects of terbutaline on single channel currents were studied in the excised inside-out patch configuration, inside-out patches were made approximately 30 min after application of terbutaline. In addition, in experiments using excised inside-out patches, the channel activity was recorded from different patches, i.e. inside-out patches were made from cells which were not treated with terbutaline for control experiments, while for terbutaline experiments inside-out patches were made from cells 30 min after application of 10 μM terbutaline.

Single channel recordings and data analysis

Single channel recordings and data analysis were performed using the same methods as reported previously (Tohda et al. 1994). Single channel currents were measured at 28–30°C from cell-attached or inside-out patches. Current signals were digitized at a sampling rate of 5000 Hz and the channel kinetics were analysed using a 2000 Hz low-pass Gaussian filter. A 500 Hz low-pass filter using a software Gaussian filter was used to present the actual traces. Single channel conductances were determined from the slope of the current-voltage relationship in cell-attached patches.

Open probability of a single channel

Channel activity was expressed as open probability (Po) as reported previously (Marunaka & Eaton, 1991; Marunaka, 1996):

| (1) |

where N is the number of channels, i is the number of channels being simultaneously open and Pi is the open probability of only i channels being simultaneously open. Also, as reported previously (Marunaka, 1996), the channels studied in the present report were activated by cytosolic Ca2+. Even when the Po of an unstimulated patch was small, we could estimate the number of channels per patch by making an inside-out patch with the cytosolic surface of the channel exposed to a high [Ca2+] (10 mM) leading to high Po, and then either a low [Ca2+] (1 nM) or a high [Cl−] (140 mM) to produce a very low Po. Such treatments allowed us to observe both events with all channels open and all channels closed so we could determine accurately the actual number of channels in a patch. Further, our estimate of the number of channels per patch membrane could be statistically substantiated at the 95 % confidence level using methods that have been described previously (Marunaka & Eaton, 1991; Marunaka & Tohda, 1993).

Mean open and closed times

The mean open (To) and closed (Tc) times were determined from open and closed time interval histograms using the methods reported previously (Marunaka & Eaton, 1990a, b; Eaton & Marunaka, 1990).

Mean closing and opening rates

As shown in Results, the channel studied in the present report had one open and one closed state. Therefore, the mean closing (Rc) and opening (Ro) rates were calculated as follows: Rc= 1/To and Ro= 1/Tc.

Determination of the number of co-operative Ca2+-binding sites and the concentration of cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c) required for half-maximal activation of the channel

The number of co-operative Ca2+-binding sites and the [Ca2+]c required for half-maximal activation were determined by fitting the data to the following equation using a non-linear least-squares fitting algorithm:

|

(2) |

where Po,max is the maximal value of Po, K½(Ca) is the [Ca2+]c required for half Po,max, and m (= Hill coefficient) is the number of co-operative binding sites for cytosolic Ca2+.

Statistical analyses

Results are presented as means ±s.d. Statistical significance was tested with Student's t test or ANOVA as appropriate. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Single channel currents, open probabilities and current-voltage relationships before and after application of terbutaline

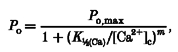

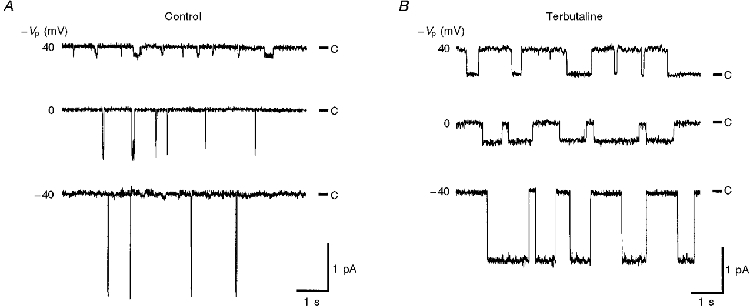

Figure 1 shows traces of single channel currents obtained from a cell-attached patch formed on the apical membrane of a fetal rat alveolar cell before and approximately 30 min after application of 10 μM terbutaline while the patch was maintained. The single channel traces shown in Fig. 1A and B were obtained from the same patch. This channel is sensitive to amiloride with a concentration for half-maximal block of < 1 μM (Marunaka, 1996). As reported previously (Tohda et al. 1994), this channel is equally permeable to Na+ and K+ with little permeability to Cl− (permeability ratio of Na+ to Cl− (PNa/PCl) > 10) and is, therefore, a NSC channel. Terbutaline caused an increase in the Po of the channel with no applied potential in the cell-attached configuration from 0.03 ± 0.04 to 0.62 ± 0.18 (n = 8 patches, P < 0.00001). The channels had a linear current-voltage relationship before and after terbutaline application with reversal potentials of 41.7 ± 2.3 and 19.8 ± 3.3 mV, respectively (n = 8, P < 0.00001), indicating that the apical membrane depolarized by 21.9 ± 4.0 mV after application of terbutaline (Fig. 2A; n = 8, P < 0.00001). The single channel conductance was 27.8 ± 2.3 and 28.2 ± 2.1 pS in terbutaline-untreated and -treated cells, respectively (n = 8, not significant). The Po of the untreated channel increased slightly but significantly with apical membrane depolarization (^; Fig. 2B; 0.42 ± 0.30 V−1; n = 8, significantly larger than zero with P < 0.01). On the other hand, Po of the terbutaline-stimulated channel was not significantly voltage dependent in the range of applied potentials between −60 to +60 mV although a voltage dependence of the size observed in untreated channels would not have been detected due to the increased variability of Po in terbutaline-treated channels (•; Fig. 2B; 0.38 ± 0.65 V−1; n = 8, not significantly different from zero).

Figure 1. Single channel current traces obtained before and after application of terbutaline.

Actual traces of single channel currents obtained from a cell-attached patch formed on the apical membrane of fetal lung alveolar epithelium cultured on a permeable support before (A) and 30 min after (B) basolateral application of 10 μM terbutaline, a β2-adrenergic agonist. Voltage values (−Vp) shown next to individual traces indicate the displacement of the patch membrane potential from the resting membrane potential, i.e. 40 mV indicates that the patch membrane was depolarized by 40 mV from the membrane potential. C denotes the closed channel level. Downward deflections indicate inward current across the patch membrane (current from pipette to cell). Terbutaline activated the channel and decreased the magnitude of the inward current at −Vp= 0 mV (resting apical membrane potential). This patch membrane had only one channel.

Figure 2. Current-voltage relationships of single channels (A) and voltage dependence of channel open probability (B) before and 30 min after application of terbutaline in cell-attached patches.

A, current-voltage relationships before (^) and 30 min after (•) application of terbutaline (10 μM) were linear with reversal potentials of 41.7 ± 2.3 and 19.8 ± 3.3 mV(n = 8, P < 0.00001) more positive than the resting apical membrane potential, respectively. Application of terbutaline caused a change in the reversal potential of 21.9 ± 4.0 mV (n = 8, P < 0.00001). The results were obtained from eight individual cell-attached patches. B, voltage dependence of channel open probability before (^) and 30 min after (•) application of terbutaline in cell-attached patches. At all potentials (−Vp) tested (−60 to 60 mV), the open probability increased after terbutaline application. The open probability in control patches showed a slight dependency on the membrane potential, i.e. depolarization increased the open probability (0.42 ± 0.30 V−1, n = 8, significantly larger than zero with P < 0.01), while in terbutaline-activated channels no voltage dependence was observed (0.38 ± 0.65 V−1, n = 8, not significantly different from zero). The results were obtained from eight individual cell-attached patches. Four out of a total of eight patches contained only one channel per patch, and the other four patches had two channels per patch.

Open and closed time interval histograms before and after application of terbutaline

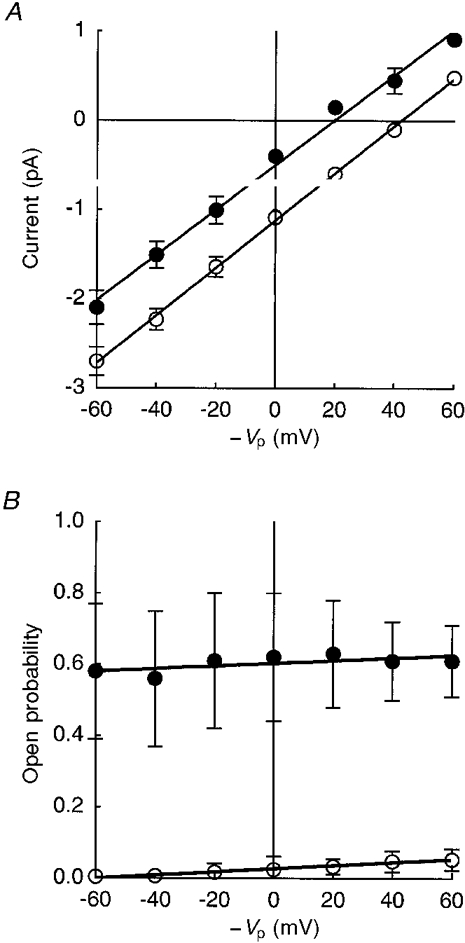

Figure 3 shows typical mean open and closed time interval histograms obtained from a cell-attached patch with no applied potential before and approximately 30 min after application of terbutaline. Before terbutaline application (Fig. 3A), both the open and closed time interval histograms could be well fitted by a single exponential function. The mean open and closed times were 15 and 841 ms, respectively. After terbutaline application (Fig. 3B), the open and closed time interval histograms could also be fitted by a single exponential function with mean open and closed times of 1549 and 1106 ms, respectively. Mean values for open and closed times from five cell-attached patches are shown in Table 1. Only the mean open time increased significantly after application of terbutaline implying that the increase in the open probability was due to an increase in the open time.

Figure 3. Typical open and closed time interval histograms in a cell-attached patch with no applied potential obtained from a cell before (A) and 30 min after (B) application of terbutaline.

In both untreated (A) and treated (B) cells, open (a) and closed (b) time interval histograms could be fitted by one exponential function. These results were obtained from the same patch before and after application of terbutaline (10 μM). This patch contained only one channel. The histograms in A were generated from a 14 min record without application of terbutaline. The results in Aa are shown on an expanded time scale in the inset. The histograms in B were generated from a 20 min record which began 30 min after application of terbutaline.

Table 1.

Mean open and closed times of channels before (Control) and after application of terbutaline obtained from open and closed time interval histograms in the cell-attached configuration

| Condition | Mean open time(ms) | Mean closed time(ms) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 17 ± 5 | 842 ± 179 |

| Terbutaline | 1551 ± 497* | 996 ± 357 |

The values were obtained from five individual cell-attached patches.

P < 0.00001 compared with Control. Each patch contained only one channel.

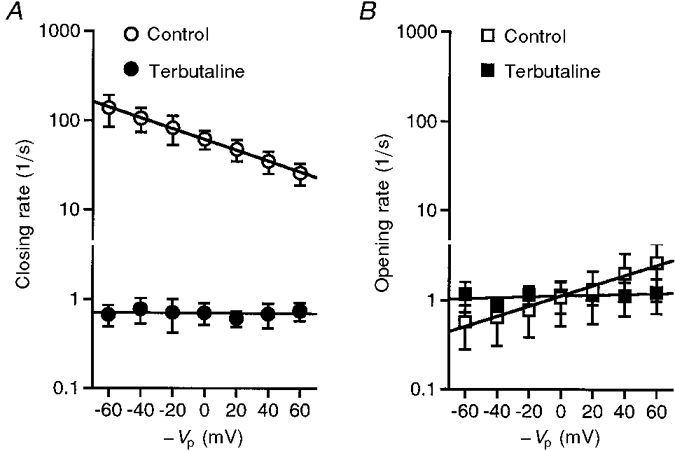

We determined the closing and opening rates at each voltage (Fig. 4). In control (without terbutaline treatment), the closing rate decreased and the opening rate increased as the apical membrane was depolarized (Control in Fig. 4A and B). Changes in the apical membrane potential of 199 ± 94 and 217 ± 83 mV produced 10-fold changes in the closing and opening rates, respectively (Control in Fig. 4A and B; n = 5, significant dependence on voltage, P < 0.01). On the other hand, in the terbutaline-stimulated channel, the closing and opening rates did not show any statistically significant changes for applied potentials between −60 and +60 mV (Terbutaline in Fig. 4A and B). Terbutaline treatment appeared to depolarize the apical membrane by 20 mV from −40 to −20 mV. However, the closing rate of the depolarized untreated channel was quite different from the closing rate of the terbutaline-stimulated channel at any potential between −60 and +60 mV. These observations suggest that the terbutaline-induced decrease in the closing rate can at most only partly be due to depolarization of the apical membrane.

Figure 4. Voltage dependence of the closing (A) and opening (B) rates of the channel before (Control) and after (Terbutaline; 10 μM) application of terbutaline in cell-attached patches.

In the absence of terbutaline, as the membrane depolarized, the closing and opening rates significantly decreased and increased, respectively. The slope of the plot of log [closing rate]vs. voltage was −5.9 ± 2.4 s−1 V−1 (n = 5), which is significantly different from zero (P < 0.01). The slope of the plot of log [opening rate]vs. voltage was 5.3 ± 2.3 s−1 V−1 (n = 5), which is also significantly different from zero (P < 0.01). Changes in the membrane potential of 199 ± 94 and 217 ± 83 mV (n = 5) produced 10-fold changes in the closing and opening rates of the untreated channel, respectively. On the other hand, the closing and opening rates of the channel after application of terbutaline did not show any significant dependence on the membrane potential. The results were obtained from five individual cell-attached patches which contained only one channel per patch.

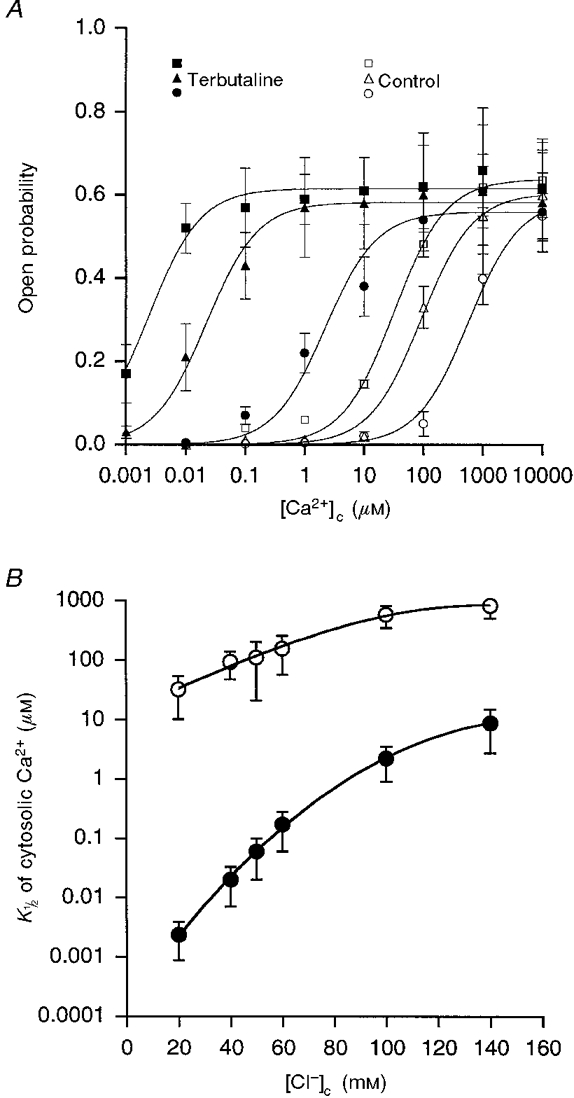

Relationship between Po, [Ca2+]c and [Cl−]c

We next studied the effects of [Ca2+]c on the Po of untreated (control) and terbutaline-treated channels at varying [Cl−]c (20, 40 and 100 mM; Fig. 5A). Using eqn (2), we fitted the dose-response of the channel to obtain the number of Ca2+-binding sites. The value was not significantly different from 1 (Table 2). Therefore, we obtained the best fit curve using eqn (2) with the number of Ca2+-binding sites set to 1 (m = 1). An increase in [Ca2+]c elevated Po in both treated and untreated cells. However, the [Ca2+]c which produced a half-maximal increase in Po (K½(Ca)) depended upon [Cl−]c and terbutaline. In untreated channels, K½(Ca) was 572 ± 230 μM at 100 mM [Cl−]c and 32 ± 22 μM at 20 mM [Cl−]c (n = 5, P < 0.001). In the terbutaline-treated channels, K½(Ca) was 2.2 ± 1.3 μM at 100 mM [Cl−]c and 2.4 ± 1.5 nM at 20 mM [Cl−]c (n = 5, P < 0.005). In other words, terbutaline increased the sensitivity of the channel to cytosolic Ca2+ by 260-fold at 100 mM [Cl−]c and by 13 000-fold at 20 mM [Cl−]c. The dependence of K½(Ca) on [Cl−]c in control vs. terbutaline-treated channels is plotted in Fig. 5B. Terbutaline decreased the K½(Ca) at all [Cl−]c tested in the present study (20–140 mM); however, a larger effect of terbutaline on K½(Ca) was observed at lower [Cl−]c (Fig. 5B). These observations show that the effects of terbutaline on the cytosolic Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel are enhanced by a decrease in [Cl−]c.

Figure 5. Ca2+ dependence of open probability at various [Cl−]c.

A, Ca2+ dependence of the open probability of untreated (Control, open symbols) and terbutaline-treated (Terbutaline, closed symbols; 10 μM) channels in inside-out patches with bathing solutions containing either 20 mM (squares), 40 mM (triangles) or 100 mM (circles) Cl−. The continuous lines were obtained from eqn (2) with one binding site for cytosolic Ca2+ (m = 1, Hill coefficient = 1), since the value of m in eqn (2) was not significantly different from 1 (as shown in Table 2). The relationship between the open probability and [Ca2+]c was shifted by terbutaline application at each [Cl−]c (20, 40 and 100 mM). However, the magnitude of the shift was dependent on [Cl−]c, i.e. the magnitude of the shift increased as [Cl−]c decreased. B, values of [Ca2+]c producing a half-maximal increase in open probability (K½(Ca)) of the untreated (^) and terbutaline-treated (•) channels at various [Cl−]c. Terbutaline decreased the K½(Ca) at all [Cl−]c tested in the present study (20–140 mM); however, a larger effect of terbutaline on K½(Ca) was observed at lower [Cl−]c. These observations show that the effects of terbutaline on the cytosolic Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel are enhanced by a decrease in [Cl−]c. The results were obtained from five individual inside-out patches. In control, three out of a total of five patches contained only one channel per patch, and the other two patches had two channels per patch. In terbutaline-treated channels, two out of a total of five patches contained only one channel per patch, and the other three patches had two channels per patch. In the case of terbutaline-treated channels, inside-out patches were made approximately 30 min after application of terbutaline.

Table 2.

| [Cl−]c(mM) | Control | Terbutaline |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| 40 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.3 |

| 50 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| 60 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 |

| 100 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.3 |

| 140 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

The values were obtained from five individual excised inside-out patches. All values are not significantly different from 1.0.

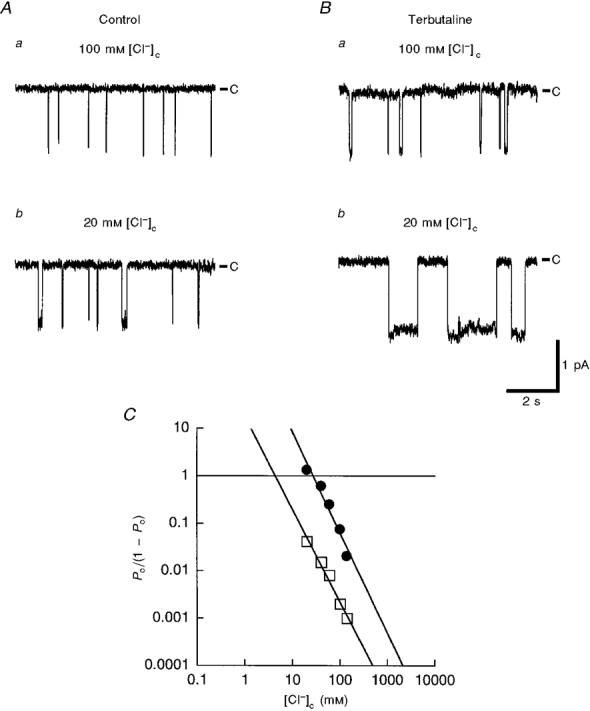

We further analysed the relationship between [Cl−]c and Po of untreated and terbutaline-treated channels. Figure 6 shows typical traces of single channel currents (Fig. 6A and B) and a typical Hill plot of the chloride dependence of Po (Fig. 6C) in inside-out patches obtained from terbutaline-untreated and -treated cells. The Hill coefficient obtained from five experiments on untreated cells was 2.0 ± 0.3 and that from five experiments on terbutaline-treated cells was 2.1 ± 0.4 (difference not significant) in 100 nM [Ca2+]c, close to normal [Ca2+]c (Tohda et al. 1994; Niisato et al. 1997), suggesting that the channel has two co-operative Cl−-binding sites. The [Cl−]c producing half-maximal inhibition of channel Po (K½(Cl)) was 4.3 ± 2.2 and 26.0 ± 7.9 mM (n = 5, P < 0.0005) in the terbutaline-untreated and -treated channels, respectively. Since the channel has two Cl−-binding sites, the value of (K½(Cl))2 indicates the affinity of the channel for cytosolic Cl− per two Cl− ions; the values were 22.1 ± 20.0 and 726.0 ± 395.0 mM2 (n = 5, P < 0.005) in the terbutaline-untreated and -treated channels, respectively. These observations suggest that terbutaline diminishes the inhibitory action of cytosolic Cl− by decreasing the Cl− affinity of channels per two Cl− ions by about 33-fold (726.0/22.1) without changing the number of Cl−-binding sites. In addition to its action on the sensitivity of the NSC channel to cytosolic Cl−, terbutaline also directly affected [Cl−]c; [Cl−]c decreased from 45 to 27 mM after terbutaline treatment, as we have reported previously (Tohda et al. 1994). Both the decreases in [Cl−]c and the sensitivity to cytosolic Cl− are responsible for the terbutaline-induced increase in the activity of the NSC channel.

Figure 6. Typical traces of single channel currents and a typical Hill plot (Po/(1 - Po) vs.[Cl−]c) in inside-out patches at 100 nM [Ca2+]c.

A, single channel currents at 100 mM (a) and 20 mM (b) [Cl−]c in an inside-out patch obtained from an unstimulated cell. B, single channel currents at 100 mM (a) and 20 mM (b) [Cl−]c in an inside-out patch obtained from a terbutaline (10 μM)-stimulated cell. C, in the presence or absence of terbutaline, the Hill coefficient was 2: 2.0 ± 0.3 in control channels and 2.1 ± 0.4 in terbutaline-treated channels (n = 5, not significant). The [Cl−]c producing a Po of 0.5 (i.e. Po/(1 - Po) = 1; K½(Cl)) was 4.3 ± 2.2 and 26.0 ± 7.9 mM in untreated (□) and terbutaline-treated (•) channels, respectively (n = 5, P < 0.0005). Since the channel has two Cl−-binding sites, the value of (K½(Cl))2 indicates the affinity of the channel for cytosolic Cl− per two Cl− ions: 22.1 ± 20.0 and 726.0 ± 395.0 mM (n = 5, P < 0.005) in the untreated and terbutaline-treated channels, respectively. This means that terbutaline decreased the affinity of the cytosolic Cl−-binding sites per two Cl− ions by about 33-fold from control without any change in the number of the Cl−-binding sites. The results were obtained from five individual inside-out patches. In control, three out of a total of five patches contained only one channel per patch, and the other two patches had two channels per patch. In terbutaline-treated channels, two out of a total of five patches contained only one channel per patch, and the other three patches had two channels per patch. In the case of terbutaline-treated channels, inside-out patches were made approximately 30 min after application of terbutaline. In A and B, C indicates the closed channel level.

When we studied the effect of [Cl−]c on the channel activity, we replaced Cl− with gluconate. To study whether other anions have an inhibitory effect similar to that of Cl−, we replaced Cl− with bromide or acetate. When Cl− was replaced with bromide or acetate, the Po of the NSC channel increased in a manner similar to that observed with gluconate substitution: 0.56 ± 0.03 in 120 mM bromide with 20 mM chloride; 0.66 ± 0.06 in 120 mM acetate with 20 mM chloride; 0.63 ± 0.03 in 120 mM gluconate with 20 mM chloride (n = 5; differences not significant); these values were significantly larger than that in 140 mM chloride (0.02 ± 0.01; n = 5, P < 0.00001). These results indicate that at least among bromide, acetate, gluconate and Cl−, the inhibitory action is Cl− specific.

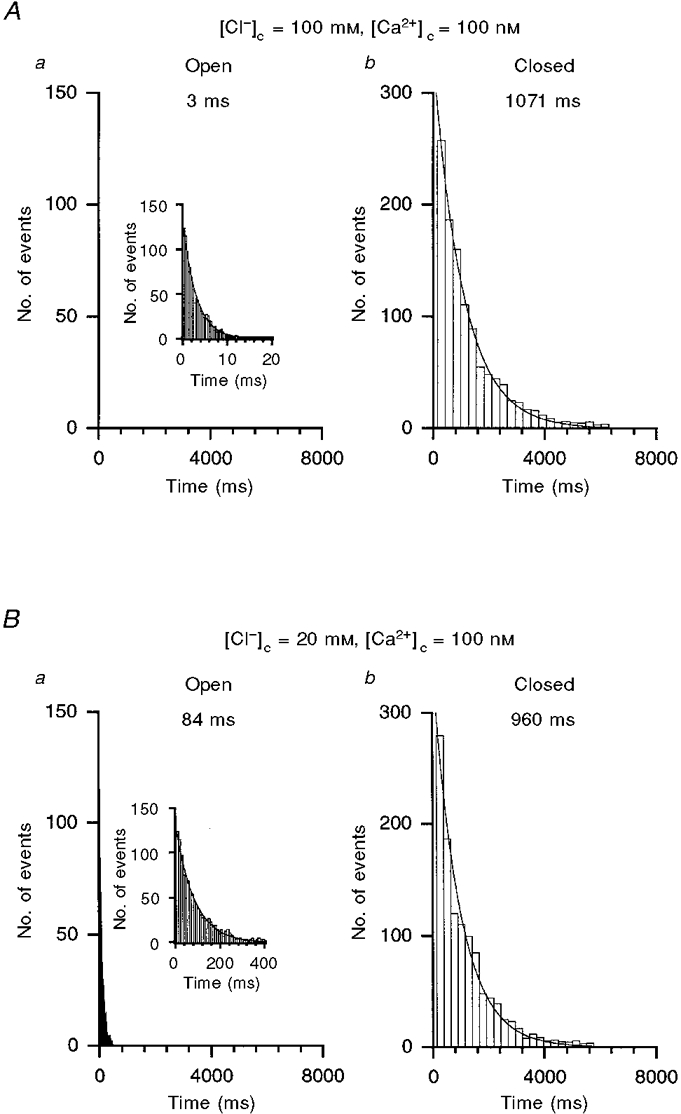

Effects of [Cl−]c on the channel kinetics

As shown above, cytosolic Cl− has an inhibitory effect on channel activity. To clarify the mechanism, we analysed channel open and closed events at different concentrations of cytosolic Cl− (20–140 mM) with 100 nM [Ca2+]c. Figure 7 shows typical open and closed time interval histograms at 20 and 100 mM [Cl−]c in an excised inside-out patch without terbutaline treatment. The open and closed time interval histograms could be fitted with a single exponential function at both Cl− concentrations (Fig. 7). The mean open time at 20 mM [Cl−]c (Fig. 7Ba) was much larger than that at 100 mM [Cl−]c (Fig. 7Aa), while the mean closed times at 20 and 100 mM [Cl−]c were almost identical (Fig. 7Ab and Bb). These observations suggest that cytosolic Cl− reduces the channel activity by decreasing the open time. We further studied the effect of [Cl−]c on the open and closed times of the terbutaline-activated channel.

Figure 7. The effect of [Cl−]c on the mean open and closed times of an untreated channel in an inside-out patch at 100 nM [Ca2+]c.

The open (a) and closed (b) time interval histograms could be fitted by one exponential function for channels exposed to either 100 (A) or 20 mM (B) [Cl−]c. The mean open time increased as [Cl−]c decreased with little change in the closed time. This patch contained only one channel. These histograms were generated from 20 min records. Results in Aa and Ba are shown on an expanded time scale in the insets.

Terbutaline-treated channels had gating kinetics similar to those of the untreated channels, although the mean open time of a treated channel was much larger than that of an untreated channel (Fig 7 and Fig 8), i.e. the open time was increased when [Cl−]c was reduced. Figure 9 shows the mean closing and opening rates of the terbutaline-untreated and -treated channels. The closing rate increased when [Cl−]c increased without any significant change in the opening rate. Since the channel has two binding sites for cytosolic Cl− (based on the Hill plots), the closing rate is expressed as a function of [Cl−]c, i.e. kc ([Cl−]c)2+k, where kc is the coefficient of the Cl− dependency of the closing rate and k is the Cl−-independent constant of the closing rate. Fitting the equation (kc ([Cl−]c)2+k) to the closing rates at various [Cl−]c in untreated (Fig. 9Aa) and terbutaline-treated (Fig. 9B a) channels, we calculated the Cl− dependency (kc) of the closing rate of terbutaline-untreated and -treated channels, i.e. kc was 46 700 ± 10 300 s−1 M−2 in terbutaline-untreated channels and 2500 ± 800 s−1 M−2 in terbutaline-treated channels; k was 0 ± 0 s−1 in both terbutaline-untreated and -treated channels. The results of these calculations indicate that terbutaline reduces the Cl− affinity of the two binding sites regulating channel closing by 19-fold per two Cl−-binding site ions (i.e. 46 700/2500). This value of 19-fold per two Cl− ions is not very different from that of the terbutaline-induced change in (K½(Cl))2 (33-fold; see Fig. 6).

Figure 8. The effect of [Cl−]c on the mean open and closed times of a terbutaline-treated channel in an inside-out patch at 100 nM [Ca2+]c.

The open (a) and closed (b) time interval histograms could be fitted by one exponential function when the bath solution contained either 100 (A) or 20 mM (B) [Cl−]c. The mean open time increased as [Cl−]c decreased with little change in the closed time. This patch contained only one channel. These histograms were generated from 10 and 28 min records at 100 and 20 mM [Cl−]c, respectively. Inside-out patches were made approximately 30 min after application of terbutaline (10 μM). Results in Aa are shown on an expanded time scale in the inset.

Figure 9. The mean closing and opening rates of untreated (A) and terbutaline-treated (B) channels in inside-out patches.

Although the mean closing rate in untreated channels (Aa) was much larger than that in terbutaline-treated channels (Ba), elevation of [Cl−]c increased the mean closing rate in both cases. On the other hand, the mean opening rate did not change significantly in response to changes in [Cl−]c, regardless of terbutaline (10 μM) application (Ab and Bb). The results were obtained from five individual inside-out patches. Each patch membrane contained only one channel per patch. In the case of the terbutaline-treated channels, inside-out patches were made approximately 30 min after application of terbutaline.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we report that terbutaline stimulates an amiloride-sensitive, Ca2+-activated, Cl−-inhibitable NSC channel with a single channel conductance of 28 pS by modulating the sensitivity of the channel to cytosolic Ca2+ and Cl−.

Comparison with other amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels

Amiloride-sensitive Na+-permeable channels are classified into three types: (1) a highly Na+-selective (PNa/PK ≡ 10–20) channel, with a small single channel conductance of ∼4 pS; (2) a moderately Na+-selective (PNa/PK ≡ 4) channel, with an intermediate single channel conductance of 7–15 pS; and (3) a non-selective cation channel (PNa/PK ≡ 1), with a relatively large single channel conductance of 23–30 pS (Orser et al. 1991; Palmer, 1992; Marunaka et al. 1994; Tohda et al. 1994; Marunaka, 1996; Marunaka et al. 1997; Jain et al. 1998). The characterization of these amiloride-sensitive channels indicates an interesting relationship between Na+ selectivity and single channel conductance: the single channel conductance increases as the Na+ selectivity decreases. However, the molecular mechanisms regulating ion selectivity and single channel conductance are still unclear.

Recently, an epithelial amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel (ENaC) has been cloned from rat distal colon by the functional expression of amiloride-sensitive Na+ currents in Xenopus oocytes (Canessa et al. 1993, 1994) with a single channel conductance of 5 pS, slow gating kinetics (mean open and closed times of second order) and high Na+ selectivity (Canessa et al. 1994; Ishikawa et al. 1998). The single channel properties of an amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel have been reported in renal epithelial A6 cells: the channel has a single channel conductance of 4 pS, high Na+ selectivity (PNa/PK gt; 20) and high sensitivity to amiloride, the concentration of half-maximal block being less than 1 μM (Hamilton & Eaton, 1986; Eaton & Marunaka, 1990; Blazer-Yost & Helman, 1997). The single channel conductance and kinetics are very similar to those of cloned ENaC from A6 cells expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Puoti et al. 1995). This indicates that the 4 pS amiloride-sensitive highly Na+-selective channel is ENaC. Unfortunately, in fetal rat lung alveolar epithelium, it is still unclear whether the NSC channel described in the present study is a member of the ENaC family because the single channel characteristics are so different from those obtained from ENaCs expressed in oocytes or observed in A6 cells. However, one study (Hummler et al. 1996) reported that perinatal death occurs in ENaC-knockout mice due to defective neonatal lung liquid clearance, indicating that ENaC contributes to lung fluid clearance. In fetal rat lung alveolar epithelium, the NSC channel described in the present study is the predominant Na+-permeable channel with high sensitivity to amiloride, the concentration of half-maximal block being < 1 μM (Marunaka, 1996), and responds to β2-adrenergic agonists which trigger clearance of fetal lung fluid, although another type of amiloride-sensitive Na+-permeable channel with a single channel conductance of 11 pS (PNa/PK= 1.8) has been found to be regulated by GTP-binding proteins in fetal guinea-pig alveolar epithelium (MacGregor et al. 1994; Mukhopadhyay et al. 1998) and might be stimulated by β2-adrenergic agonists. These reports (Hummler et al. 1996; Marunaka, 1996) suggest that the NSC channel, the predominant channel found in fetal rat alveolar epithelium, contributes to the clearance of fetal lung fluid. However, the single channel characteristics of the NSC channel such as the single channel conductance, the ion selectivity and the dependency on cytosolic Ca2+ are very different from ENaCs (Palmer & Frindt, 1987; Ling & Eaton, 1989; Marunaka et al. 1997; Garty & Palmer, 1997; Ishikawa et al. 1998). On the other hand, another report (Kizer et al. 1997) showed that expression of the α-subunit of ENaC alone in a null cell line (LM (TK−)) results in a channel with identical selectivity for Na+ and K+ (i.e. NSC channel) and a single channel conductance of 24 pS. Further, it has been reported that in the alveolar epithelium of rats, the α-subunit of ENaC is expressed, while β- and γ-subunits of ENaC are expressed mainly in the bronchial and bronchiolar epithelia but at very low levels in the alveolar epithelium (Matsushita et al. 1996). Taken together, these reports suggest that in the fetal rat alveolar epithelium the α-subunit of ENaC is mainly expressed, resulting in the expression of the NSC channel shown in the present report, although the first report of the α-subunit of ENaC (Canessa et al. 1993) indicated that the α-subunit of ENaC alone expressed in Xenopus oocytes induces a highly Na+-selective channel, rather than a NSC channel.

The effect of terbutaline on channel activity and its stability in inside-out patches

We used excised, inside-out patches to study the effects of cytosolic ionic conditions on untreated and terbutaline-treated channels. In the case of control (no terbutaline treatment), the channel activity was stable without any significant decrease in activity even after excised inside-out patches were formed. On the other hand, in cases of terbutaline-treated channels, the channel activity sometimes decreased after excised inside-out patches were made. However, in other cases, the channels obtained from cells treated with terbutaline showed stable activity even after the patch membrane containing the channel was excised from the cell to form an inside-out patch. For studies on the action of terbutaline and its relationship to cytosolic ionic conditions, we selected channels with stable activity even in excised inside-out patches. Since the regulatory pathway by which terbutaline stimulates NSC channels is still unknown, we cannot conclusively suggest a reason why in some cases the channel activity decreases but in other cases does not. However, one possible mechanism of terbutaline action on the channel is through phosphorylation by a protein kinase, in particular, cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), since the intracellular second messenger of terbutaline, a β2-adrenergic agonist, is usually considered to be cAMP. Therefore, the terbutaline action on the channel might be mediated through phosphorylation of the channel by PKA which is activated by terbutaline. If so, the terbutaline action should be reversible by a protein phosphatase. In cases when channel activity decreased in excised inside-out patches, a membrane-bound protein phosphatase might be close to the channel in a patch membrane and dephosphorylate the phosphorylated channel, resulting in a decrease in activity. In cases when channel activity was stable in excised inside-out patches, there are likely to be no membrane-bound protein phosphatases associated with the channel, so that the phosphorylated channel will not be dephosphorylated and will stably maintain its activity even in excised inside-out patches. However, while this picture of channel activity is consistent with our previous work, more experiments are needed to examine the mechanism by which terbutaline regulates the channel before reaching this conclusion.

The role of [Cl−]c in modulating the activity of ion channels

Cytosolic Cl− has been reported to regulate the amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel (Dinudom et al. 1993): lowering cytosolic Cl− regulates the amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel in salivary gland. In some other tissues, cytosolic Cl− has also been reported to regulate ion conductances (Pantoja et al. 1992; Chan & Nelson, 1992; Nakajima et al. 1992; Grinstein et al. 1992). Although these reports indicated that cytosolic Cl− can regulate ionic conductances, none of the reports indicated whether there are actual physiologically relevant changes in [Cl−]c. In fetal ratlung alveolar epithelium, we have reported that, in response to β2-adrenergic stimulation, there is a decrease in [Cl−]c (Tohda et al. 1994) which is due to cell shrinkage caused by KCl release and water movement after activation of K+ and Cl− channels (Nakahari & Marunaka, 1996, 1997). Thus, in fetal rat lung alveolar epithelium where a decrease in [Cl−]c has been reported in a previous study (Tohda et al. 1994) and modification of the sensitivity to cytosolic Cl− was also observed in the present study, the regulation by cytosolic Cl− could have a physiological role in the regulation of the amiloride-sensitive channel.

Although we suggest that cytosolic Cl− has a direct action on channel activity based on our experiments in excised inside-out patches, there are some alternative explanations for the effects of cytosolic Cl− on the channel activity. For example, GTP-binding proteins are regulated by cytosolic Cl− (see e.g. Higashijima et al. 1987), and recent studies (MacGregor et al. 1994; Kemp & Olver, 1996; Komwatana et al. 1996; Mukhopadhyay et al. 1998) show that amiloride-sensitive channels are regulated by GTP-binding proteins. Therefore, the cytosolic Cl− might regulate the amiloride-sensitive NSC channel reported in the present study via a GTP-binding protein-dependent pathway. More experiments would be required to determine whether modulation of a GTP- binding protein by cytosolic Cl− plays a role in the regulation of NSC channels in fetal rat alveolar epithelium.

Role of [Ca2+]c in regulating the activity of NSC channels

In the present report, we show that NSC channels are activated by cytosolic Ca2+, and that a β2-adrenergic agonist increases the sensitivity of NSC channels to cytosolic Ca2+. However, a previous report (Niisato et al. 1997) showed that [Ca2+]c was only increased transiently by a β2-adrenergic agonist. Therefore, it is possible that the transient increase in [Ca2+]c is of too short a duration to have a significant physiological role in the activation of the NSC channel. Nonetheless, adrenergic stimulation may still play an important role by increasing the sensitivity of NSC channels to cytosolic Ca2+ so that levels normally present in the cells can alter channel activity even though prior to adrenergic stimulation the same levels would not affect the channels.

In addition, as mentioned above, β2-adrenergic agonists cause cell shrinkage (Nakahari & Marunaka, 1996, 1997) which occurs biphasically: an initial rapid cell shrinkage followed by a slower shrinkage. The initial rapid cell shrinkage is due to activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels which cause K+ efflux, and the slower cell shrinkage is caused by activation of a cAMP-activated Cl− conductance (Nakahari & Marunaka, 1995, 1996, 1997). If experimental conditions are manipulated so that the β2-adrenergic agonist-induced transient increase in [Ca2+]c does not occur in fetal rat lung alveolar epithelium, the time course of the β2-adrenergic agonist-induced cell shrinkage is much slower than if there is a normal transient increase in [Ca2+]c (Nakahari & Marunaka, 1996, 1997). Thus, the transient increase in [Ca2+]c is important to both the magnitude and the time course of regulatory volume decrease. Further, cell shrinkage occurring under isosmotic conditions leads to a decrease in [Cl−]c (for a review see Marunaka, 1997b). Therefore, in a situation in which there is no β2-adrenergic-induced transient increase in [Ca2+]c, the shrinkage-induced decrease in [Cl−]c would occur slowly compared with the decrease in [Cl−]c that would occur in the presence of a normal transient increase in [Ca2+]c. This suggests that the transient increase in [Ca2+]c caused by β2-adrenergic stimulation enhances the activation of NSC channels not by activating the channels directly, but rather by causing a decrease in [Cl−]c, which is one of the factors that activate NSC channels.

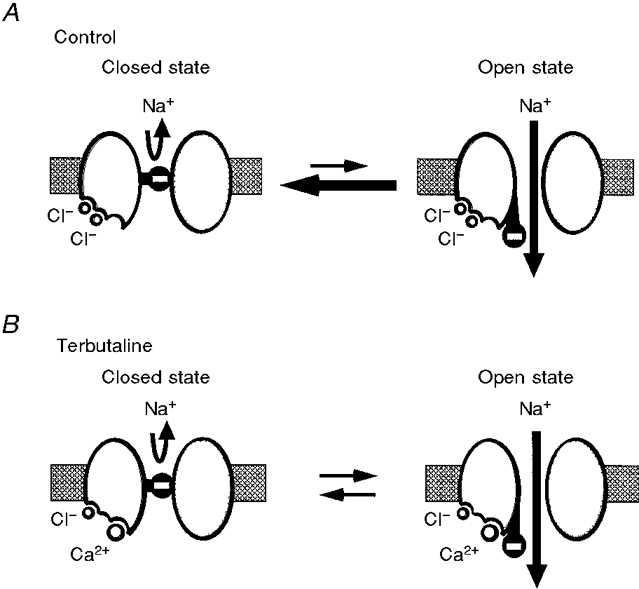

A hypothetical schematic representation of channel gating kinetics

From the observations in the present study, we propose a possible conceptual model of NSC channel gating (Fig. 10). In this hypothetical model, the channel has one binding site for cytosolic Ca2+ and two binding sites for cytosolic Cl−. For untreated channels (control), [Cl−]c is 45 mM (Tohda et al. 1994), which is 10 times larger than the K½(Cl) for inhibition of Po by cytosolic Cl− (4.3 mM), implying that the cytosolic Cl−-binding sites are almost always occupied by Cl− (Fig. 10A). The [Ca2+]c of control cells is about 50 nM (Niisato et al. 1997), which is 2200 times smaller than the K½(Ca) for stimulation of Po by cytosolic Ca2+ (110 μM at 50 mM [Cl−]c) so that the cytosolic Ca2+-binding site is almost never occupied by Ca2+ (Fig. 10A). On the other hand, after terbutaline application, [Cl−]c decreases to 27 mM (Tohda et al. 1994), which is approximately the same as the K½(Cl) for Cl− inhibition (26 mM) so that on average the binding sites for cytosolic Cl− are occupied by cytosolic Cl− for only about half of the time, i.e. on average only one binding site is occupied by cytosolic Cl− (see Fig. 10B). [Ca2+]c in terbutaline-stimulated cells is about 100 nM (Niisato et al. 1997), which is at least 40 times larger than the K½(Ca) for activation by cytosolic Ca2+ (2.4 nM in 20 mM [Cl−]c) so that the cytosolic Ca2+-binding site is almost always occupied by Ca2+ (see Fig. 10B). If the channel gate has a negative charge, two Cl− ions, with their negative charges, bound to the channel would facilitate channel closing (Fig. 10A). On the other hand, in the terbutaline-stimulated case, one Cl− ion and one Ca2+ ion, with a net positive charge of 1, bound to the channel prolong the time of the channel remaining in the open state (i.e. a decrease in the closing rate; Fig. 10B). Thus, the terbutaline-induced decrease in the closing rate shown in Fig. 9 is explained by this hypothetical model. The temperature during measurement of single channel characteristics in the present study was 28–30°C, which is somewhat below the normal physiological temperature for mammalian cells. In general, for ion channels, the primary effect of increases in temperature is to increase the opening and closing rates although, except in a few cases, this effect is usually not profound (Q10 values less than 2). Therefore, even at 37°C we would expect that the qualitative aspects of our hypothetical model would remain the same. Nonetheless, to determine the quantitative effects of temperature on the NSC channel and its regulation by intracellular chloride and calcium will require additional experiments. Although more experimental results are required to confirm details of this hypothetical model, this relatively simple kinetic picture is sufficient to explain qualitatively our results.

Figure 10. A hypothetical schematic model of channel gating kinetics of the NSC channel for untreated (A) and terbutaline-treated (B) conditions.

The channel has two Cl−-binding sites and one Ca2+-binding site which regulate the channel activity. A, the cytosolic Cl−-binding sites are almost always occupied by Cl− in untreated channels. The cytosolic Ca2+-binding site is almost never occupied by Ca2+. If the channel gate has a negative charge, two Cl− ions, with their negative charges, bound to the channel promote channel closing. B, on average, the two binding sites for cytosolic Cl− are usually occupied by cytosolic Cl− for only about half the time in terbutaline-treated channels, i.e. on average only one of the two binding sites for cytosolic Cl− is occupied by cytosolic Cl− in terbutaline-treated channels. The cytosolic Ca2+-binding site is almost always occupied by Ca2+. In the terbutaline-stimulated case, one Cl− ion and one Ca2+ ion, with one net positive charge, bound to the channel cause the channel to remain in the open state for a longer time, leading to a decrease in the closing rate.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to Mr B. Rafii for his technical assistance with the cell harvest and culture. This work was supported by a Group Grant from the Medical Research Council of Canada (project no. 9) and partly by the Kidney Foundation of Canada and the Ontario Thoracic Society (Block Term Grant) to Y. Marunaka, a Group Grant from the Medical Research Council of Canada (project no. 8) to H. O'Brodovich and by an NIH grant DK37963 to D. C. Eaton. N. Niisato is a Research Fellow and is supported by a stipend from The Research Training Centre, The Hospital for Sick Children. Y. Marunaka was a recipient of Scholar of the Medical Research Council of Canada.

References

- Blazer-Yost BL, Helman SI. The amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel: binding sites and channel densities. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C761–769. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.3.C761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MJ, Olver RE, Ramsden CA, Strang LB, Walters DV. Effects of adrenaline and of spontaneous labour on the secretion and absorption of lung liquid in the fetal lamb. The Journal of Physiology. 1983;344:137–152. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa CM, Horisberger J-D, Rossier BC. Epithelial sodium channel related to proteins involved in neurodegeneration. Nature. 1993;361:467–470. doi: 10.1038/361467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa CM, Schild L, Buell G, Thorens B, Gautschi I, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC. Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature. 1994;367:463–467. doi: 10.1038/367463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HC, Nelson DJ. Chloride-dependent cation conductance activated during cellular shrinkage. Science. 1992;257:669–671. doi: 10.1126/science.1379742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding JW, Dickie J, O'Brodovich H, Shintani Y, Rafii B, Hackam D, Marunaka Y, Rotstein OD. Inhibition of amiloride-sensitive sodium-channel activity in distal lung epithelial cells by nitric oxide. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:L378–387. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.3.L378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinudom A, Young JA, Cook DI. Na+ and Cl− conductances are controlled by cytosolic Cl− concentration in the intralobular duct cells of mouse mandibular gland. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1993;135:289–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00211100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DC, Marunaka Y. Ion channel fluctuation: ‘Noise’ and single-channel measurements. In: Helman SI, Van Driessche W, editors. Channel and Noise in Epithelial Tissues. Current Topics in Membranes and Transport. Vol. 37. San Diego, USA: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 61–114. [Google Scholar]

- Foskett JK, Melvin JE. Activation of salivary secretion: coupling of cell volume and [Ca2+]i in single cells. Science. 1989;244:1582–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.2500708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garty H, Palmer LG. Epithelial sodium channels: function, structure, and regulation. Physiological Reviews. 1997;77:359–396. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinstein S, Furuya W, Downey GP. Activation of permeabilized neutrophils: role of anions. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263:C78–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.1.C78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N, Tohda H, Doi Y, O'Brodovich H, Marunaka Y. Effects of insulin and tyrosine kinase inhibitor on ion transport in the alveolar cell of the fetal lung. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1992;187:802–808. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91267-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton KL, Eaton DC. Single-channel recordings from two types of amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channels. Membrane Biochemistry. 1986;6:149–171. doi: 10.3109/09687688609065447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashijima T, Ferguson KM, Sternweis PC. Regulation of hormone-sensitive GTP-dependent regulatory proteins by chloride. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262:3597–3602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummler E, Barker P, Gatzy J, Beermann F, Verdumo C, Schmidt A, Boucher R, Rossier BC. Early death due to defective neonatal lung liquid clearance in αENaC-deficient mice. Nature Genetics. 1996;12:325–328. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-325. 10.1038/ng0396-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Marunaka Y, Rotin D. Electrophysiological characterization of the rat epithelial Na+ channel (rENaC) expressed in Madian-Darby canine kidney cells. Effects of Na+ and Ca2+ Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:825–846. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.6.825. 10.1085/jgp.111.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Niisato N, O'Brodovich H, Marunaka Y. The effect of brefeldin A on terbutaline-induced sodium absorption in fetal rat distal lung epithelium. Pflügers Archiv. 1997;434:492–494. doi: 10.1007/s004240050425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain L, Chen X-J, Brown LAS, Eaton DC. Nitric oxide inhibits lung sodium transport through a cGMP-mediated inhibition of epithelial cation channels. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:L475–484. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.4.L475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp PJ, Olver RE. G protein regulation of alveolar ion channels: implications for lung fluid transport. Experimental Physiology. 1996;81:493–504. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1996.sp003952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizer N, Guo XL, Hruska K. Reconstitution of stretch-activated cation channels by expression of the α-subunit of the epithelial sodium channel cloned from osteoblasts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:1013–1018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komwatana P, Dinudom A, Young JA, Cook DI. Cytosolic Na+ controls an epithelial Na+ channel via the Go guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:8107–8111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling BN, Eaton DC. Effects of luminal Na on single Na channels in A6 cells, a regulatory role for protein kinase C. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:F1094–1103. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.6.F1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor GG, Olver RE, Kemp PJ. Amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels in fetal type II pneumocytes are regulated by G proteins. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:L1–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.1.L1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y. Amiloride-blockable Ca2+-activated Na+-permeant channels in the fetal distal lung epithelium. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;431:748–756. doi: 10.1007/BF02253839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y. Regulatory mechanisms of amiloride-blockable Na+-permeable channels in rat distal lung epithelium. Physiologist. 1997a;40:A22. [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y. Hormonal and osmotic regulation of NaCl transport in renal distal nephron epithelium. Japanese The Journal of Physiology. 1997b;47:499–511. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.47.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y, Eaton DC. Effects of insulin and phosphatase on a Ca2+ dependent Cl− channel in a distal nephron cell line (A6) Journal of General Physiology. 1990a;95:773–789. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.5.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y, Eaton DC. Chloride channels in the apical membrane of a distal nephron A6 cell line. American Journal of Physiology. 1990b;258:C352–368. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.2.C352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y, Eaton DC. Effects of vasopressin and cAMP on single amiloride-blockable Na channels. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:C1071–1084. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.5.C1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y, Niisato N. Catecholamine regulation of amiloride-sensitive Na+ transport in the fetal rat alveolar epithelium. In: Benos DJ, editor. The Physiology and Functional Diversity of Amiloride-Sensitive Na+ Channels: a New Gene Superfamily. Current Topics in Membranes. San Diego, USA: Academic Press; 1999. in the Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y, Shintani Y, Downey GP, Niisato N. Activation of Na+-permeant cation channel by stretch and cAMP-dependent phosphorylation in renal epithelial A6 cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:327–336. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y, Tohda H. Effects of vasopressin on single Cl− channels in the apical membrane of distal nephron epithelium (A6) Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1993;1153:105–110. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y, Tohda H, Hagiwara N, Nakahari T. Antidiuretic hormone-responding non-selective cation channel in distal nephron epithelium (A6) American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:C1513–1522. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.6.C1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y, Tohda H, Hagiwara N, O'Brodovich H. Cytosolic Ca2+-induced modulation of ion selectivity and amiloride sensitivity of a cation channel and beta agonist action in fetal lung epithelium. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1992;187:648–656. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91244-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita K, McCray PB, Jr, Sigmund RD, Welsh MJ, Stokes JB. Localization of epithelial sodium channel subunit mRNAs in adult rat lung by in situ hybridization. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:L332–339. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.2.L332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S, Dutta-Roy AK, Fyfe GK, Olver RE, Kemp PJ. G-protein-coupled prostaglandin receptor modulates conductive Na+ uptake in lung apical membrane vesicles. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:L567–572. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.4.L567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahari T, Marunaka Y. Regulation of whole cell currents by cytosolic cAMP, Ca2+, and Cl− in rat fetal distal lung epithelium. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:C156–162. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.1.C156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahari T, Marunaka Y. Regulation of cell volume by β2-adrenergic stimulation in rat fetal distal lung epithelial cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1996;151:91–100. doi: 10.1007/s002329900060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahari T, Marunaka Y. β-Agonist-induced activation of Na+ absorption and KCl release in rat fetal distal lung epithelium: a study of cell volume regulation. Experimental Physiology. 1997;82:521–536. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Sugimoto T, Kurachi Y. Effects of anions on the G protein-mediated activation of the muscarinic K+ channel in the cardiac atrial cell membrane. Journal of General Physiology. 1992;99:665–682. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.5.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niisato N, Nakahari T, Tanswell K, Marunaka Y. β2-Agonist regulation of cell volume in fetal distal lung epithelium by cAMP-independent Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1997;75:1030–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brodovich H. Epithelial ion transport in the fetal and perinatal lung. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:C555–564. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.4.C555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brodovich H, Hannam V, Rafii B. Benzamil induced sodium channel blockade impairs lung liquid clearance at birth and bioelectric properties of fetal type II alveolar epithelium. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1990a;141:164a. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brodovich H, Hannam V, Seear M, Mullen JBM. Amiloride impairs lung water clearance in newborn guinea pigs. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1990b;68:1758–1762. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.4.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olver RE, Schneeberger EE, Walters DV. Epithelial solute permeability, ion transport and tight junction morphology in the developing lung of the fetal lamb. The Journal of Physiology. 1981;315:395–412. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orser BA, Bertlik M, Fedorko L, O'Brodovich H. Cation channel in fetal alveolar type II epithelium. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1991;1094:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(91)90021-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LG. Epithelial Na channels: function and diversity. Annual Review of Physiology. 1992;54:51–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.54.030192.000411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LG, Frindt G. Effects of cell Ca and pH on Na channels from rat cortical collecting tubule. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:F333–339. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.253.2.F333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoja O, Dainty J, Blumwald E. Cytoplasmic chloride regulates cation channels in the vacuolar membrane of plant cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1992;125:219–229. doi: 10.1007/BF00236435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post M, Smith BT. Histochemical and immunocytochemical identification of alveolar type II epithelial cells isolated from fetal rat lung. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1988;137:525–530. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post M, Torday JS, Smith BT. Alveolar type II cells isolated from fetal rat lung organotypic cultures synthesize and secrete surfactant-associated phospholipids and respond to fibroblast-pneumonocyte factor. Experimental Lung Research. 1984;7:53–65. doi: 10.3109/01902148409087908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puoti A, May A, Canessa CM, Horisberger J-D, Schild L, Rossier BC. The highly selective low-conductance epithelial Na channel of Xenopus laevis A6 kidney cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:C188–197. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.1.C188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohda H, Foskett JK, O'Brodovich H, Marunaka Y. Cl− regulation of a Ca2+-activated nonselective cation channel in β agonist treated fetal lung alveolar epithelium. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:C104–109. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.1.C104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]