Abstract

The molecular nature of the strong inward rectifier K+ channel in vascular smooth muscle was explored by using isolated cell RT-PCR, cDNA cloning and expression techniques.

RT-PCR of RNA from single smooth muscle cells of rat cerebral (basilar), coronary and mesenteric arteries revealed transcripts for Kir2.1. Transcripts for Kir2.2 and Kir2.3 were not found.

Quantitative PCR analysis revealed significant differences in transcript levels of Kir2.1 between the different vascular preparations (n = 3; P < 0.05). A two-fold difference was detected between Kir2.1 mRNA and β-actin mRNA in coronary arteries when compared with relative levels measured in mesenteric and basilar preparations.

Kir2.1 was cloned from rat mesenteric vascular smooth muscle cells and expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Currents were strongly inwardly rectifying and selective for K+.

The effect of extracellular Ba2+, Ca2+, Mg2+ and Cs2+ ions on cloned Kir2.1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes was examined. Ba2+ and Cs+ block were steeply voltage dependent, whereas block by external Ca2+ and Mg2+ exhibited little voltage dependence. The apparent half-block constants and voltage dependences for Ba2+, Cs+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ were very similar for inward rectifier K+ currents from native cells and cloned Kir2.1 channels expressed in oocytes.

Molecular studies demonstrate that Kir2.1 is the only member of the Kir2 channel subfamily present in vascular arterial smooth muscle cells. Expression of cloned Kir2.1 in Xenopus oocytes resulted in inward rectifier K+ currents that strongly resemble those that are observed in native vascular arterial smooth muscle cells. We conclude that Kir2.1 encodes for inward rectifier K+ channels in arterial smooth muscle.

Small arteries are a major contributor to the control of systemic blood pressure and local blood flow. Metabolic demand in these small arteries is linked to blood flow in part through the release of vasodilating substances such as potassium ions. Extracellular potassium concentrations have been demonstrated to reach >10 mM during ischaemia in both the cerebral (Sieber et al. 1993) and coronary (Kleber, 1983; Weiss et al. 1989) circulation. Unlike many other types of smooth muscle, elevations of extracellular potassium in these arteries do not lead to vasoconstriction, but to vasodilatation and (ultimately) increased blood flow (Katz & Linder, 1938; Bonaccorsi et al. 1977). Elevations in extracellular potassium concentrations occur in the heart and brain under physiological as well as pathophysiological conditions. While evidence suggests that the overall health of the heart and brain is dependent upon the fine regulation of coronary and cerebral blood flow by substances such as potassium ions, the mechanism(s) by which these substances regulate arterial diameter remain to be fully characterized.

A number of different mechanisms have been suggested to be involved in the regulation of arterial diameter by low concentrations of extracellular K+ including Na+-K+-ATPase (Webb & Bohr, 1978; McCarron & Halpern, 1990) and the inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir) conductance (Edwards et al. 1988; McCarron & Halpern, 1990; Knot et al. 1996). The first evidence for inward rectifier K+ channels in arteries was provided by measuring currents in intact voltage-clamped cerebral (Hirst et al. 1986; Edwards et al. 1988) and mesenteric (Edwards & Hirst, 1988) arteries (for review see Hirst & Edwards, 1989). Subsequently, inward rectifier K+ currents were identified in isolated smooth muscle cells from cerebral (Quayle et al. 1993) and coronary arteries (Robertson et al. 1996; Quayle et al. 1996). The Kir channels identified in these isolated arterial smooth muscle cells possess the characteristics of the Kir2 subfamily - strong inward rectification, a conductance dependent upon extracellular potassium concentration, and a voltage- and time-dependent gating process (Quayle et al. 1993, 1996). Inward rectifier K+ channels in isolated cerebral and coronary myocytes also exhibit a distinct quantitative pattern of block by external barium, caesium, calcium and magnesium ions (Quayle et al. 1993; Robertson et al. 1996) (Table 1). Three distinct isoforms of the Kir2 channel subfamily have been identified in the rat brain: Kir2.1 (Kubo et al. 1993), Kir2.2 (Takahashi et al. 1994) and Kir2.3 (Morishige et al. 1994). Recently, a fourth member (Kir2.4) has been identified and differs significantly from the other three members with respect to barium block (Töpert et al. 1998). Members of the Kir2 family also show strong inward rectification and possess consensus sites for phosphorylation by protein kinases A and C (Henry et al. 1996). However, the molecular form(s) of Kir channel expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells has not been identified.

Table 1.

Comparison of the electrophysiological properties for Kir2.1, 2.2 and 2.3 expressed in oocytes and native arterial smooth muscle inward rectifier K+ currents

| Vascular smooth muscle | Kir2.1 | Kir2.2 | Kir2.3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR of isolated arterial smooth muscle cells | Does not apply | + | — | — |

| Ba2+ block | Kd(0) = 38.1 μM (Quayle et al. 1993); Kd(0) = 21.1 μM (Robertson et al. 1996) | Kd(0) = 41.7 μM, μ = 0.51; Kd(0) = 62 μM, μ = 0.54(Shieh et al. 1998) | K1/2˜5 μM at −50 mV (Takahashi et al. 1994) | K1/2˜10 μM at −60 mV (Morishige et al. 1994) |

| Cs+block | Low affinity block; no measurable block with 50 μM at −60 mV; Kd(0) = 19.0 mM (Robertson et al. 1996); 4% reduction with 100 μM at −60 mV (Quayle et al. 1993) | Low affinity block; 0 to < 10% inhibition by 50 μM at −60 mV; Kd(0) = 50.8 mM, μ = 1.95, K1/2 = 457 μM at −60 mV; Kd(0) = 54 mM, μ = 1.57(Abrams et al. 1996), K1/2 = 300 μM to 1 mM (Kubo et al. 1993) | High affinity block; maximal block with 50 μM at −60 mV; K1/2 < 5 μM (Takahashi et al. 1994) | High affinity block; maximal block with 50 μM at −60 mV (Morishige et al. 1994) |

| Ca2+ block | 49.3% reduction with 10 mM Ca2+ at −60 mV (Robertson et al. 1996) | 42.8% reduction with 10 mM Ca2+ at −60 mV | Not done | Not done |

| Mg2+ block | 52.8% reduction with 10 mM Mg2+ at −60 mV (Robertson et al. 1996) | 58.1% reduction with 10 mM Mg2+ at −60 mV | Not done | Not done |

| Inactivation at hyper-polarizing potentials | Minimal | Minimal | Pronounced inactivation (Takahashi et al. 1994) | Minimal |

The purpose of the present study was to test the hypothesis that one or more members of the Kir2 channel subfamily is expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells and that cloned members of this subfamily possess similar pharmacological and electrophysiological characteristics to inward rectifier K+ currents recorded in native cells. We found only one form (Kir2.1) of the inward rectifier potassium channel in single smooth muscle cells from cerebral, coronary and mesenteric arteries, with the highest level being observed in coronary arteries. Cloning and expression of Kir2.1 from arterial smooth muscle in Xenopus oocytes yielded K+ currents that exhibited strong inward rectification. Inward rectifier K+ currents in native arterial myocytes exhibited a very distinct pattern of blocking properties of barium, caesium, calcium and magnesium ions which reflect the nature and positions of ion binding sites in the channel (Quayle et al. 1993; Robertson et al. 1996). Comparison of the blocking properties of these ions on native inward rectifier K+ currents and cloned Kir2.1 current reveals striking quantitative similarities, and is different to what has been previously reported for Kir2.2, 2.3 and 2.4 channels (Koyama et al. 1994; Morishige et al. 1994; Takahashi et al. 1994; Töpert et al. 1998).

METHODS

Isolation and collection of vascular smooth muscle tissues and cells

Sprague-Dawley rats (12–14 weeks, approximately 300 g) were overdosed with pentobarbitone (150 mg kg−1 administered by intraperitoneal injection) and the heart, brain and mesenteric artery were removed after exsanguination. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the animal care committees of the Universities of Nevada and Vermont. Samples were placed in ice-cold extracellular solution containing 55 mM NaCl, 80 mM sodium glutamate, 6 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose and 100 μM CaCl2 (pH 7.3). Coronary arteries were isolated from the right side of the ventricular septum. After dissection of basilar, coronary and mesenteric arteries, connective tissue was removed. The endothelium was removed on a portion of the artery samples by inverting the artery and scraping the lumenal surface with a glass slide.

Vascular smooth muscle cells were isolated by a procedure previously described (Robertson et al. 1996). Briefly, intact arteries were placed into the above-mentioned extracellular solution which included 1 mg ml−1 papain, 1 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 1 mg ml−1 dithioerythritol, and incubated for various time periods (20 min for coronary arteries; 30 min for basilar arteries; 35 min for mesenteric arteries) at 37°C. Samples were then transferred to a second vial containing saline with 1 mg ml−1 collagenase (30 % collagenase H and 70 % collagenase F; Sigma) and 1 mg ml−1 BSA and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. The tissue was washed 5 times with ice-cold extracellular solution to remove any enzymes. Arteries were then triturated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette to yield single smooth muscle cells. Cells were transferred to an experimental chamber and allowed to adhere to a glass coverslip for 10 min prior to perfusion of the bath with sterile extracellular solution (to remove any cellular debris). Microelectrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) using a vertical pipette puller yielding 40–50 μm tip diameters. After positioning the tip of the electrode over individual single smooth muscle cells, negative pressure was applied and individual cells were collected; approximately 60 myocytes were collected for each RNA preparation. Only spindle-shaped cells (length 100–150 μm; diameter 5–10 μm) were selected to ensure that samples were not contaminated by other cell types. Cells were expelled from the pipette tip into an RNase-free microcentrifuge tube after which the electrode was rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered saline solution to ensure that all cells were recovered. Cells and tissue samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for future use.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was prepared from rat vascular smooth muscle tissues, brain and cells isolated from basilar, coronary, and mesenteric arteries using the SNAP Total RNA Isolation kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Polyinosinic acid (an RNA carrier; 20 μg) was added to the vascular smooth muscle cell lysates. First strand cDNA was synthesized from the RNA preparations using the Superscript II RNase H Reverse Transcriptase kit (Gibco BRL); RNA (1 μg) was reversed transcribed using an oligo (dT)12–18 primer (500 μg μl−1). To perform PCR the following sets of primers were used: Kir2.1 sense, nucleotides (nt) 864–883, and anti-sense, nt 1170–1189 (gene accession no. GA L48490); Kir2.1 sense, nt 335–356, and anti-sense, nt 1613–1632 (gene accession no. GA X73052). Kir2.2 sense, nt 419–438, and anti-sense, nt 1235–1254 (GA X78461); and Kir2.3 sense, nt 407–426, and anti-sense, nt 1303–1322 (GA S71382); and β-actin sense, nt 2383–2402 and anti-sense, nt 3071–3091 (GA V01217). PCR primers for β-actin were used to assess the viability of RNA samples as well as to detect genomic DNA contamination whereby the primers were designed to span an intron in addition to two exons. Brain tissue-derived RNA is included as a species control for the Kir specific primers as all three forms of Kir are expressed in brain neuronal tissue. Complimentary DNA (20 % of the first strand reaction) was combined with sense and anti-sense primers (20 μM), 1 mM dNTPs, 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 100 mM KCl, 3 units of TAQ (Promega), 1 Ampliwax Gem 100 (Perkin Elmer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and RNase-free water to a final volume of 50 μl. PCR was performed in a COY II Thermal Cycler under the following conditions: 32 cycles at 94°C, 1 min; 57°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min; and then, incubated at 72°C, 10 min. A second round of PCR (5 μl of 1st PCR reaction in lieu of cDNA) was performed under the same conditions. PCR products were separated by 2 % agarose gel electrophoresis, directly ligated into pCR2.1 vector constructs (Invitrogen), and transformed using the TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen). DNA sequences were determined using an automatic nucleotide sequencer (Model 310, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR)

Q-PCR was performed using the PCR MIMIC Construction Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) which is based upon a competitive PCR approach - non-homologous engineered DNA standards (referred to as PCR MIMICs) compete with target DNA for the same gene-specific primers. PCR MIMICs were constructed for Kir2.1 and β-actin and competitive PCR was carried out by titration of sample cDNA with known amounts of the desired non-homologous PCR MIMIC constructs; serial dilutions (tenfold and then, twofold) of these constructs were then added to PCR amplification reactions. Following PCR, products were separated by 2 % agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified using Molecular Analyst (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Data analysis and statistical treatments for molecular studies

Qualitative PCR was performed on 60-cell preparations isolated from basilar, coronary and mesenteric arteries from four different rats. For quantitative PCR studies, arteries from two to four different rats were pooled for each RNA isolation; at least four different RNA isolations were performed. The concentrations of the target DNA and β-actin were determined for each sample; the target DNA concentration was then normalized to β-actin expression. All results are expressed as means ±s.e.m. Data for quantitative PCR were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and differences between tissues were illustrated by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison tests; P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Cloning and in vitro transcription of vascular Kir2.1

Kir2.1 was cloned from rat mesenteric smooth muscle cells by first performing PCR in the presence of gene-specific Kir2.1 sense (nt 335–356; GA X73052) and anti-sense (nt 1613–1632; GA X73052) primers. Full-length cDNA fragments were ligated into pCR2.1 vector constructs (Invitrogen) and transformed using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Clones were then sequenced using an automated nucleotide sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Model 310). Capped RNA (cRNA) was in vitro transcribed from pCR2.1 plasmids containing full-length Kir2.1 cDNA using the Ambion mMessage mMachine transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Briefly, reactions contained 2–5 μg of linearized template DNA, 500 μM ribonucleotides, 1 × transcription buffer and 40 units of T7 RNA polymerase; the concentration of the final cRNA was adjusted to 1 ng μl−1.

Xenopus oocyte preparation and Kir2.1 RNA injection

Female Xenopus laevis frogs were anaesthetized by immersion in 0.2 % tricaine (pH 7.5) for 3–5 min. Stage V-VI oocytes were obtained by partial ovarectomy and washed in ND96 solution, comprising (mM): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl; 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes, pH 7.5. Oocytes were defolliculated by rotation in Ca2+-free ND96 containing 2 mg ml−1 collagenase (Type 1A, Sigma) for 45 min at room temperature (22°C). Collagenase was removed and the follicular layer of individual oocytes was then carefully removed using fine-tipped forceps while the oocytes were immersed in ND96 solution. Oocytes were then stored at 16°C for 24 h in ND96 solution supplemented with 0.55 mg ml−1 pyruvate and 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin after which they were injected (Nanoject, Drummond, PA, USA) with water (control) or 40–50 ng of cRNA (final volume 50 nl). Oocytes were maintained following injection at 16°C in ND96 supplemented solution for 3–6 days prior to electrophysiological recording.

Double electrode voltage clamp

Experiments were performed at room temperature (22°C) using the two-electrode voltage clamp setup of Dr Alan Segal (Ion Channel Group, University of Vermont). Microelectrodes, pulled from borosilicate glass, were bevelled to ensure clean impalement (1–5 MΩ), and filled with 1 M KCl for recording. Currents were recorded using a two-electrode voltage clamp amplifier (Warner Instrument Corp.) and filtered at 400 Hz using a low-pass Bessel filter (Frequency Devices). Data were acquired and analysed using pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments,) on PC-compatible computers.

Membrane currents were recorded using either voltage ramps or voltage pulses. Voltage ramps of 480 ms duration from −100 to +60 mV (0.3 mV ms−1) were performed by initially holding the membrane potential at 0 mV and stepping to −100 mV for 15 ms prior to the start of the ramp. During voltage pulses (1, 5 or 10 s duration), cells were held at −10 mV and stepped from +60 to −120 mV in −20 mV increments.

The standard bath solution contained the following (mM): 90 KCl, 5 Hepes, 0.1 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2. KCl was replaced with an equimolar concentration of NaCl to test the effect of [K+]o. MgCl2 was not added to the bathing solution when testing inhibition by Ca2+ and Mg2+. Ca2+ (100 μM) was present in all experiments.

Currents other than those through inward rectifier K+ channels were measured by performing voltage protocols in the presence of high concentrations (10 times the half-block constant at 0 mV for inward rectifier currents) of Ba2+ (300 or 500 μM). Unless indicated, the Ba2+-insensitive current was subtracted from test currents to reveal the Ba2+-sensitive current (Robertson et al. 1996). Current at the end of voltage pulses, where inhibition was observed to have reached a steady level (10 s for Ba2+; 5 s for Ca2+ and Mg2+; and 1 s for Cs+), was measured to determine current levels and calculate fractional inhibition.

Patch clamp electrophysiology

The whole-cell configuration of the patch clamp technique (Hamill et al. 1981) was used on vascular smooth muscle cells isolated from rat coronary arteries. The standard pipette (internal) solution contained the following (mM): 107 KCl, 33 KOH, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2 (∼20 nM free Ca2+), 3 Na2ATP, 0.1 NaADP, and 0.2 Na3GTP (pH 7.2). The bath solution contained 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes and 100 μM CaCl2 (pH 7.4). All experiments were performed at room temperature (22°C). Pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (Sutter Instruments) using a Narishige puller (PP-83) to a resistance of 3–5 MΩ. Tips were coated with sticky dental wax and fire polished (Narishige MF-83). Whole-cell currents were acquired using an Axopatch 200 amplifier (Axon Instruments) and an 8-pole Bessel filter. Currents were filtered at 1 kHz. Data were acquired and analysed using pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments). All results are expressed as means ±s.e.m. of n cells.

To eliminate other K+ currents, the membrane potential was measured generally negative to −20 mV (which would limit the activation of Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) channels and voltage-activated K+ channels; Nelson & Quayle, 1995). In addition, the pipette solution contained low concentrations of Ca2+ (to minimize the activity of KCa channels) and 3 mM ATP (to inhibit ATP-sensitive K+ channel activity). To determine the Ba2+-sensitive current a protocol similar to that described above was used to subtract currents other than those through inward rectifier channels.

Data fitting

Fractional inhibition of inward currents by ionic block (Ba2+ and Cs+) were fitted by the following equation (eqn (1)) (e.g. for Ba2+):

| (1) |

where IBa is the Kir current in Ba2+, Icon is the Kir current in the control solution, [Ba2+] is the Ba2+ concentration, and Kd is the apparent dissociation constant for Ba2+.

To determine the voltage dependence of the dissociation constants the following equation (eqn (2)) was used to fit the data:

| (2) |

where Kd(0) is the dissociation constant at 0 mV, V is the voltage, z is the valency of the ion, F is Faradays constant, μ is the slope constant (indicating the sensitivity of the Kd to the applied voltage), R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature in Kelvin.

To determine the kinetics of Ba2+ block, the onset of Ba2+ block was fitted with a single exponential. The time constant (τ) is related to the blocking (kb) and unblocking (k−b) rate constants and the Ba2+ concentration by the following equation (eqn (3)):

| (3) |

RESULTS

Identification of the Kir2 channel subfamily members

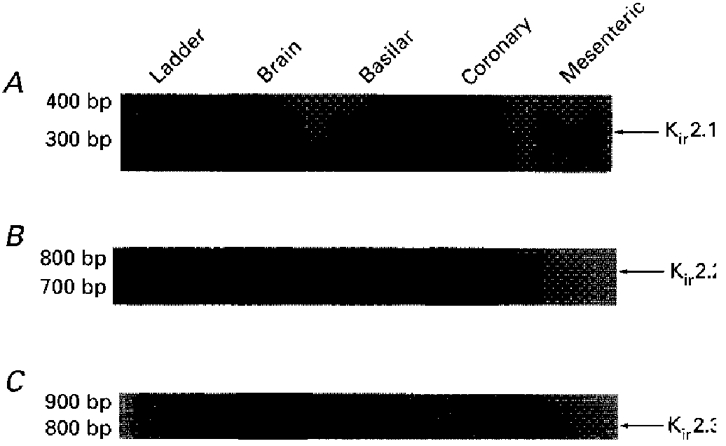

The molecular species of Kir2 channel subfamily members expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells was determined by isolating total RNA from basilar, coronary and mesenteric smooth muscle cell preparations. Qualitative analysis of transcriptional expression in dispersed and selected smooth muscle cells minimizes the possibility of contaminating expression from non-smooth muscle cell types. First strand cDNA was synthesized and then amplified by PCR. As indicated in Fig. 1A, RT-PCR yielded visible amplified products of Kir2.1 in mRNA isolated from basilar, coronary and mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells. In contrast, transcripts for Kir2.2 or 2.3 subfamily members were not found within these same cell preparations (Fig. 1B and C, respectively). Amplification products corresponding to Kir2.2 and 2.3 were detected in mRNA isolated from rat cerebellum (neuronal) (lane 2, B and C, respectively), indicating that the primers were capable of amplifying the gene specific products in rat. Two amplifications were performed for detection of Kir2.2 and 2.3 expression. Therefore, at this level of detection, these Kir family members could not be detected. We further tested mRNA preparations derived from intact, denuded arteries to test whether the detection level of isolated cells was too low to detect transcriptional expression of these Kir forms. Neither Kir2.2 nor 2.3 expression could be detected from these preparations. The Kir2.1 fragment sequences were determined to be 100 % homologous to rat tumour mast cell line Kir2.1 mRNA (Wischmeyer et al. 1995).

Figure 1. RT-PCR detection of Kir2.1 in anatomically different vascular smooth muscle cell preparations.

Amplified PCR products generated using gene-specific primers for Kir2.1 (A), Kir2.2 (B), or Kir2.3 (C) were fractionated on 2 % agarose gels and size markers were used to indicate the size of the experimental fragments (lane 1). Transcriptional expression for Kir2.1 was detected in basilar, coronary and mesenteric arteries, whereas no expression for Kir2.2 and Kir2.3 was observed. Rat cerebellum was used as a positive control for the Kir2 primers.

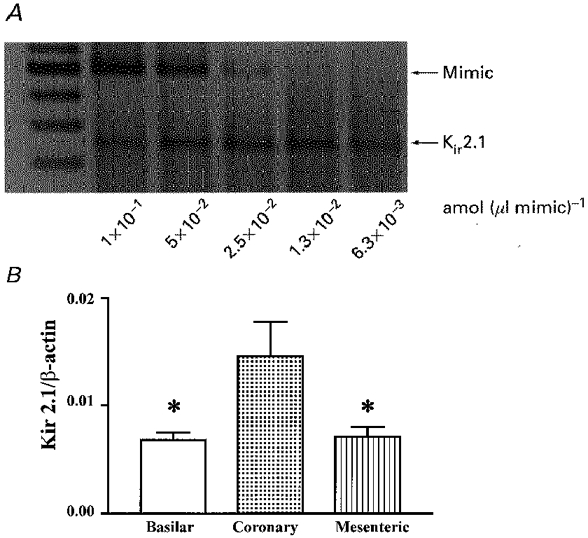

While qualitative RT-PCR demonstrated the molecular species of Kir2 channel subfamily members present in vascular smooth muscle cells, differences in expression levels of these transcripts in the different arterial preparations were detected by quantitative RT-PCR. Studies using quantitative competitive PCR were performed by including gene-specific primers for Kir2.1 or β-actin in the PCR reaction. A constant volume of the target cDNA was used and varying concentrations of a specific non-homologous engineered DNA fragment was included in the reaction. A representative competitive PCR gel is shown in Fig. 2A. Actual concentrations of the Kir2.1 cDNA and, in turn, mRNA in the various arteries are expressed relative to β-actin RNA concentration (Fig. 2B). Transcriptional levels of Kir2.1 in coronary arteries (0.0146 ± 0.0032) were significantly greater than those detected in mesenteric (0.0071 ± 0.001) or basilar (0.0068 ± 0.001) preparations (n = 3, P < 0.05). These results indicate that arterial smooth muscle cells express Kir2.1 transcripts.

Figure 2. Differential transcriptional expression of Kir2.1 in rat arteries.

Competitive PCR products were resolved on 2 % ethidium bromide agarose gels. A representative gel of quantitative RT-PCR for Kir2.1 in rat basilar, coronary and mesenteric arteries is shown in A; two-fold serial dilutions of mimic DNA were included in the PCR reactions while the target cDNA (Kir2.1) concentration remained constant. The actual concentrations of target cDNA were calculated and expressed relative to β-actin cDNA concentration (B). Results are expressed as means ±s.e.m.; *significant difference when compared with transcript levels detected in coronary artery.

Characterization of cloned Kir2.1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes and comparison with native Kir channel currents

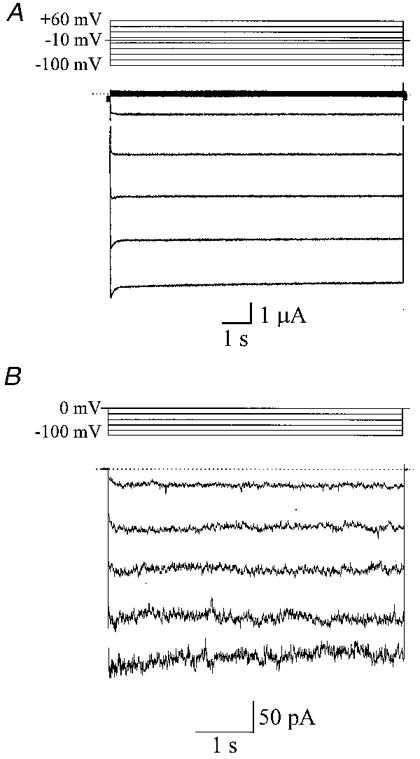

To test the hypothesis that Kir2.1 encodes inward rectifier potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle, currents were recorded from cloned Kir2.1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes and were compared with Kir channels recorded from native vascular smooth muscle cells. Two-electrode voltage clamp was performed on Xenopus oocytes 3–6 days after injection with RNA encoding the Kir2.1 channel protein. In a bathing solution containing 90 mM K+ (i.e. EK = 0 mV), voltage steps of 10 s duration from +60 to −100 mV (from a holding potential of −10 mV) evoked a strong, inwardly rectifying current which was selective for K+ ions (Fig. 3A). These currents were not observed in control oocytes injected with 50 nl of H2O (data not shown). Figure 3B demonstrates the Ba2+-sensitive (500 μM) currents observed in an isolated coronary (septal) artery smooth muscle cell in a bathing solution containing 140 mM K+ (i.e. EK = 0 mV). This cell was held at a membrane potential of 0 mV with voltage pulses between −20 and −100 mV applied every 10 s in 20 mV increments.

Figure 3. Arterial smooth muscle inward rectifier currents.

A, inwardly rectifying potassium currents recorded from a Xenopus oocyte injected with RNA encoding a Kir2.1 channel protein cloned from vascular smooth muscle. The oocyte was held at a membrane potential of −10 mV and voltage pulses (of 10 s duration), from +60 to −100 mV were applied every 4 s in 20 mV increments. The bathing solution contained 90 mM K+. B, Ba2+-sensitive (500 μM) currents in an isolated coronary (septal) artery smooth muscle cell in a bathing solution containing 140 mM K+ (i.e. EK = 0 mV). The cell was held at a membrane potential of 0 mV with voltage pulses of between −20 and −100 mV applied every 10 s in 20 mV increments.

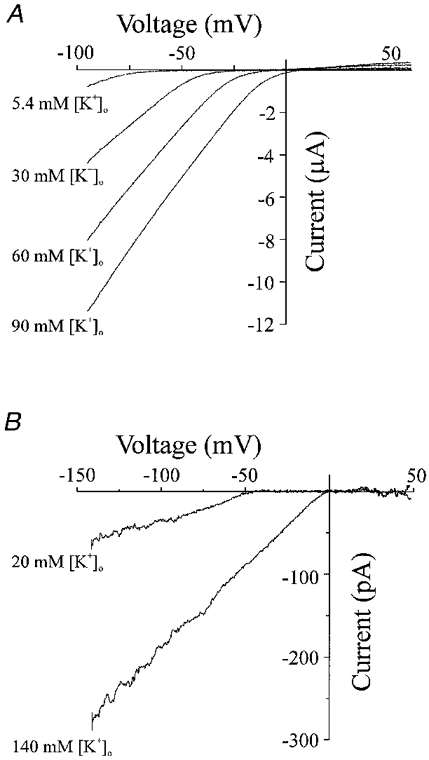

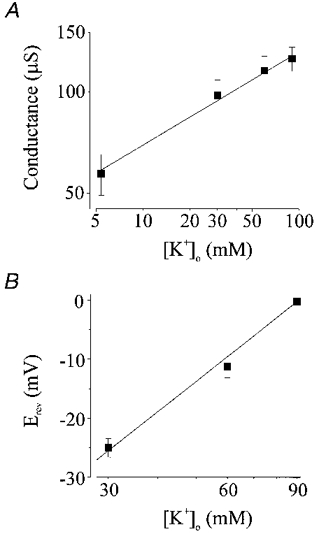

K+ selectivity of cloned Kir2.1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes

We investigated the effect of changing external K+ concentrations (5.4, 30, 60 and 90 mM K+) on the properties of Kir2.1 currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Fig. 4A). The slope conductance of the current (measured from the straight portion of the I-V relationship) increased with external K+ (Fig. 4A). A similar change in the slope conductance and reversal potential (Erev) was also observed in Fig. 4B, which demonstrates the Ba2+-sensitive currents (average of five voltage ramps from −140 to +50 mV) observed in an isolated coronary (septal) artery smooth muscle cell when external (bathing) K+ was changed. The slope conductances and Erev values for this cell were 0.77 and 1.99 nS, and −47.3 mV (EK =−49.5 mV) and −3.4 mV (Ek= 0 mV) with 20 and 140 mM external K+, respectively. Slope conductances for Xenopus oocytes injected with Kir2.1 cRNA were 57.2 ± 7.9, 97.6 ± 10.7, 115.9 ± 11.6 and 125.5 ± 10.4 μS with 5.4, 30, 60 and 90 mM K+, respectively (n = 8) (Fig. 5A). The slope conductance was equal to ([K+]o)0.28 (Fig. 5A). The Erev became more positive with an increase in external K+, consistent with the potassium-selective nature of the expressed Kir2.1 channels (Fig. 5B).

Figure 4. Inward rectification shifts with a change in external [K+].

A, current-voltage relationship from the same Xenopus oocyte in a bathing solution containing 90, 60, 30 or 5.4 mM K+. I-V relationships were obtained by performing voltage ramps initially by holding at a membrane potential of 0 mV, followed by a pulse to −100 mV for 15 ms before a voltage ramp of 480 ms duration from −100 to +60 mV (0.3 mV ms−1). B, Ba2+-sensitive currents (average of 5 voltage ramps from −140 to +50 mV) observed in an isolated coronary (septal) artery smooth muscle cell with 20 and 140 mM external (bathing) K+. The slope conductance and Erev for this cell were 0.77 and 1.99 nS, and −47.3 mV (EK =−49.5 mV) and −3.4 mV (EK = 0 mV) with 20 and 140 mM external K+, respectively.

Figure 5. Elevation of external [K+] increases the conductance of inward rectifier potassium currents and shifts the reversal potential.

A, the slope conductance of the inward rectifier current increased with external [K+] (n = 8 oocytes). Slope conductance (C) was fitted with (C)([K+]o)n, giving C = 36.7μS and n = 0.28. B, changing the concentration of K+ in the bathing solution shifted the reversal potential (30 mM K+, n = 8 oocytes; 60 mM K+, n = 8 oocytes; 90 mM K+, n = 24 oocytes). The line represents the best fit to the relationship between external K+ and the reversal potential, with a slope corresponding to 53.1 mV shift in Erev for a 10-fold change in [K+].

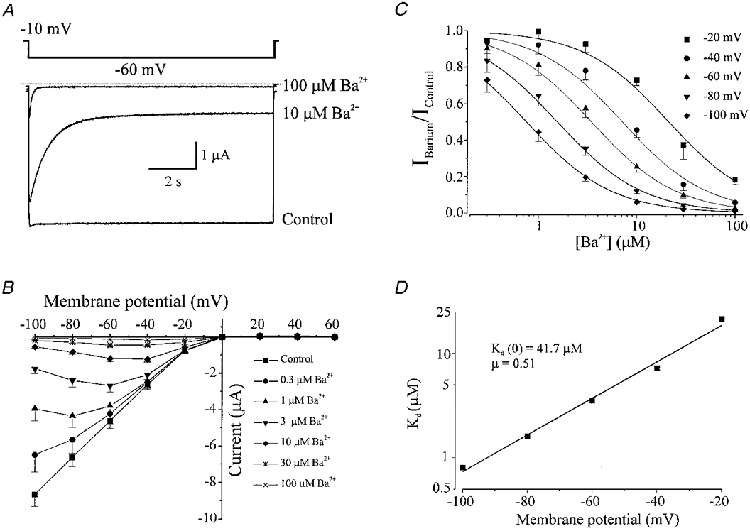

External Ba2+ inhibition of Kir2.1 currents in Xenopus oocytes

An important feature of native Kir channels is high affinity block by external barium ions. The effect of external Ba2+ concentrations on Kir2.1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes was determined. Figure 6A illustrates currents evoked from a holding potential of −10 mV to −60 mV under control conditions and in the presence of 10 and 100 μM Ba2+ in the bathing solution. Kir2.1 currents was inhibited by external Ba2+ in a concentration-dependent manner. The rate of onset and the degree of Ba2+ block increased with the concentration of Ba2+. Figure 6B and C shows the voltage- and concentration-dependent inhibition of Kir current at the end of the 10 s voltage pulse when block had reached a steady-state level. We compared the Ba2+ sensitivity of Kir2.1 with that of native inward rectifier currents from vascular tissues. The fractional inhibition of Kir2.1 currents (expressed as the Ba2+-sensitive current measured at different voltages and concentrations of Ba2+ divided by the Ba2+-sensitive current in control) was then plotted against the concentration of Ba2+ (Fig. 6C; n = 5). The data presented in Fig. 6C were fitted by eqn (1) (refer to Methods) to determine the apparent dissociation constant (Kd) at each potential. The following Kd values were obtained: 21.4 μM at −20 mV, 7.2 μM at −40 mV, 3.5 μM at −60 mV, 1.6 μM at −80 mV, and 0.8 μM at −100 mV (Table 1). Figure 6D demonstrates that the Kd decreased e-fold per 25 mV hyperpolarization; these data were fitted with eqn (2) (refer to Methods) with a Kd(0) of 41.7 μM and a slope (μ) of 0.51.

Figure 6. Ba2+ inhibition of inward rectifier potassium currents in Xenopus oocytes injected with RNA encoding Kir2.1 cloned from vascular smooth muscle cells.

Membrane current recorded from the same oocyte with voltage steps from a holding potential of −10 mV to −60 mV in the presence of 0 (control), 10 and 100 μM Ba2+. External K+ was 90 mM. Dotted line indicates zero current level. B, current-voltage relationship demonstrating the effect of applying 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30 and 100 μM Ba2+ on membrane currents recorded at the end of 10 s voltage pulses (n = 5). Bathing K+ was 90 mM. C, relationship between external Ba2+ concentration and the fractional inhibition of inward current at −20, −40, −60, −80 and −100 mV. Data were fitted with eqn (1), to give Kd values of (μm): 21.4, 7.2, 3.5, 1.6 and 0.8 at −20, −40, −60, −80 and −100 mV, respectively. D, voltage dependence of the dissociation constants (Kd) from C. Data were fitted with eqn (2) with a Kd at 0 mV of 41.7 μM, and a slope (μ) of 0.51.

Immediately upon membrane hyperpolarization Ba2+ block increases at a rate which depends upon the voltage applied and the concentration of Ba2+ present. Assuming that the blocking reaction is a simple bimolecular reaction, the reduction in Kir current by Ba2+ can be fitted by a single exponential decay function with time constant τ. At a given membrane potential, τ decreased with increasing Ba2+ concentration: e.g. with 10 μM Ba2+, at −20 mV, τ= 2814 ± 356 ms; at −40 mV, τ= 1647 ± 151 ms; at −60 mV, τ= 1159 ± 137 ms; at −80 mV, τ= 688 ± 91 ms; and at −100 mV, τ= 387 ± 55 ms (n = 5). Also, at a given membrane potential τ decreased with increasing Ba2+ concentration: e.g. at −60 mV, with 1 μM Ba2+, τ= 2810 ± 94 ms; with 3 μM Ba2+, τ= 2151 ± 149 ms; with 10 μM Ba2+, τ= 1159 ± 137 ms; with 30 μM Ba2+, τ= 496 ± 62 ms (n = 5). The time constant is related to the blocking (kb) and unblocking (k−b) rate constants, and the Ba2+ concentration as described in eqn (3) (refer to Methods). The reciprocal of τ plotted against [Ba2+] gives a straight line with slope equal to kb, and intercept equal to k−b (Fig. 7A). The kb was an exponential function of membrane potential, indicating that kb increases with membrane hyperpolarization, while k−b changed relatively little (Fig. 7B). Fitting kb values with an equation analogous to eqn (2) (refer to Methods) demonstrated a kb at 0 mV of 7.4 M−1 ms−1, and a μ value of −0.43. k−b changed only slightly over the membrane potential range, demonstrating a value of 0.26 s−1 at 0 mV, and a μ value of −1.02, indicating that the majority of the voltage dependence of the Kd comes from the voltage dependence of the blocking rate constant, kb. Since the Kd is a function of kb and k−b, such that Kd=k−b/kb, the rate constants allow an alternative estimate of the Kd at different membrane potentials. Using this procedure, the calculated Kd values were 16.4 μM at −20 mV, 10.3 μM at −40 mV, 4.9 μM at −60 mV, 1.9 μM at −80 mV, and 1.3 μM at −100 mV (see Table 1). Since k−b=Kd× kb, k−b can also be determined using the Kd and the kb calculated above, and is 0.31 s−1 at 0 mV.

Figure 7. Concentration and voltage dependence of blocking kinetics of Ba2+ on inward rectifier K+ currents from vascular smooth muscle expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

A, the onset of Ba2+ block was fitted with a single exponential after which the mean reciprocal values (±s.e.m.) of the time constant (τ) of current decay was plotted against Ba2+ concentration (n = 5 oocytes). These data were fitted by eqn (3) to determine the kb, the slope of the line, and k−b, the intercept (see Table 1). B, voltage dependence of the blocking rate, kb, and unblocking rate k−b, obtained from the slope and intercept of lines fitted in A. Data were fitted with an equation equivalent to eqn (2) with kb values of 7.4 m−1 s−1 at 0 mV and slope (μ) of −0.43, and k−b values of 0.26 s−1 at 0 mV and μ of −1.02.

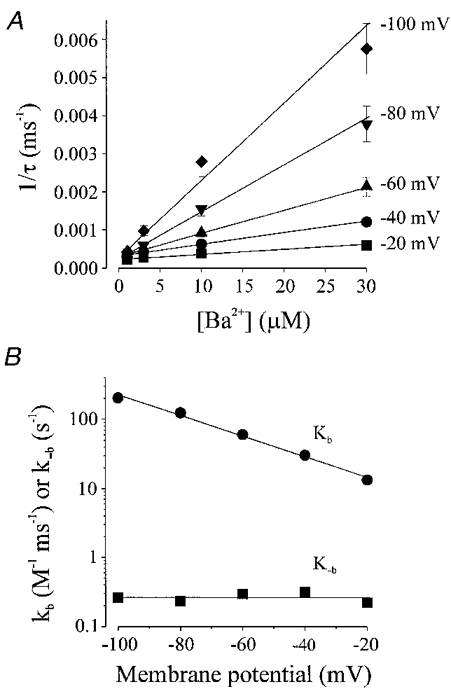

External caesium inhibition of inward rectifier K+ currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes

Another important characteristic of native Kir channels in arterial smooth muscle is the steep voltage dependence of block by caesium ions. To determine the effect of external Cs+ on Kir2.1 channel activity, we examined the effect of different concentrations of Cs+ on currents evoked by 1 s voltage pulses to membrane potentials between +40 and −120 mV, in 90 mM [K+]o. External Cs+ blocked Kir2.1 currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Inhibition of the current increased with both Cs+ concentration and hyperpolarization (Fig. 8A-C). Note in Fig. 8A that the current recorded at −100 mV in the presence of 1 mM Cs+ is smaller than that observed at −10 mV (holding potential) in control, demonstrating the voltage dependence of block. Figure 8B demonstrates that as the membrane potential becomes more hyperpolarized the current inhibition with Cs+ increases, even at the same concentration (n = 8 oocytes). Data were fitted by using eqn (1) (refer to Methods). The Kd values for Cs+ at each membrane potential were calculated as follows: 2911.7 μM at −40 mV; 458.3 μM at −60 mV; 91.6 μM at −80 mV; 19.9 μM at −100 mV; and 6.5 μM at −120 mV (Fig. 8C). The Kd decreased e-fold per 13 mV (Fig. 8D), with an estimated Kd(0) of 50.8 mM, and a slope (μ) of 1.95. The expressed channels exhibited the characteristic steep voltage dependence of caesium ion block observed in inward rectifier channels from arterial smooth muscle.

Figure 8. External Cs+ block of inward rectifier potassium currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes by injection with RNA encoding Kir2.1 cloned from vascular smooth muscle.

A, membrane current recorded from the same oocyte with voltage steps from a holding potential of −10 to −100 mV in the presence of 0 (control), 10, 100 and 1000 μM Cs+. Note that the current recorded at −100 mV in the presence of 1 mM Cs+ is smaller than that observed at −10 mV in control, demonstrating the voltage dependence of block. External K+ was 90 mM. B, current-voltage relationship demonstrating the voltage dependence of block of Cs+ at different membrane potentials (n = 8 oocytes). Currents were measured at the end of 1 s voltage pulses. C, relationship between Cs+ concentration and fractional inhibition of inward current at −40, −60, −80, −100 and −120 mV. Data were fitted using eqn (1) demonstrating Kd values of (μm): 2911.7, 458.3, 91.6, 19.9 and 6.5 at −40, −60, −80, −100 and −120 mV, respectively. D, voltage dependence of Kd. Data were fitted using eqn (2) with a Kd (0) of 50.8 mM and μ of 1.95.

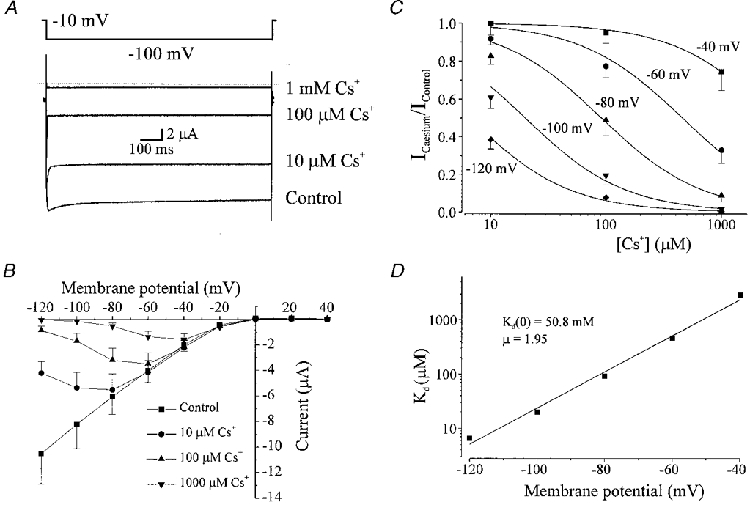

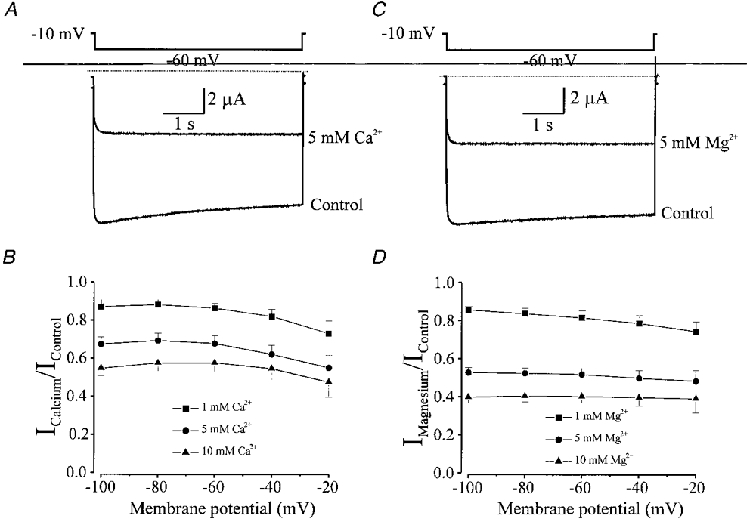

External Ca2+ and Mg2+ inhibition of inward rectifier K+ currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes

External calcium and magnesium ions block Kir channel currents in native coronary myocytes at physiological concentrations. We therefore examined the effects of external Ca2+ and Mg2+ on Kir2.1 channel activity were determined by using 5 s voltage steps from a holding potential of −10 mV to −60 mV with 90 mM [K+]o. The effects of adding 1, 5 and 10 mM Ca2+ or Mg2+ were compared with currents evoked in control (100 μM Ca2+ and nominal Mg2+ present). At −60 mV addition of 1, 5 or 10 mM Ca2+ reduced inward currents by 13.3, 31.9 and 42.8 % (n = 8), respectively (Fig. 9A and B); Fig. 9B also demonstrates that the Ca2+ block is relatively unaffected by voltage. Kir2.1 currents were also inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by Mg2+, with 1, 5 and 10 mM Mg2+ inhibiting the current by 18.1, 47.5 and 58.1 % (n = 8), respectively, at −60 mV. Inhibition of currents by Mg2+ was also independent of voltage (Fig. 9C and D).

Figure 9. External Ca2+ and Mg+ block of inward rectifier currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes by injection of RNA encoding Kir2.1 cloned from vascular smooth muscle.

A, membrane current recorded from an oocyte in response to a 5 s voltage step from −10 to −60 mV in control (100 μM Ca2+) and after addition of 5 mM Ca2+. The bathing solution contained 90 mM K+ and nominal Mg2+. B, fractional inhibition of inward rectifier currents by addition of 1, 5 and 10 mM Ca2+ at different voltages (n = 8 oocytes). Inhibition of currents by Ca2+ is not voltage dependent. C, membrane current recorded from an oocyte in response to a 5 s voltage step from −10 to −60 mV in control (0 Mg2+) and in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+. The bathing solution contained 90 mM K+ and nominal Mg2+. D, fractional inhibition of inward rectifier currents by 1, 5 and 10 mM Mg2+ at different voltages (n = 8 oocytes). Inhibition of currents by Mg2+ is not voltage dependent.

DISCUSSION

Molecular identification of Kir2 channel subfamily members

The current study indicates that transcripts for Kir2.1 are expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells. While transcripts for Kir2.1 were identified in the various arterial cell preparations, transcripts for the other members of the Kir2 subfamily (Kir2.2 and 2.3) were not. Transcripts for an inward rectifier channel, Kir2.4, recently cloned from rat brain were not examined, since it is unlikely this molecular species is responsible for K+-induced dilatations of arteries due to the low sensitivity of the currents to Ba2+ ([K+]i= 390 μM) (Töpert et al. 1998). There was significantly more Kir2.1 transcript expressed in coronary arteries than either basilar or mesenteric arteries. If these differences were translated into significantly more current in coronary artery myocytes, this could lead an increased effect of K+-induced dilatations in these vessels. Inward rectifier K+ current density is higher in myocytes from smaller than larger diameter porcine coronary arteries (Quayle et al. 1996). Consistent with this finding, we show that myocytes from the smallest diameter artery (coronary) which we tested had the highest level of Kir transcript. These coronary arteries also exhibit pronounced barium-sensitive K+-induced dilatations (Knot et al. 1996). However, smooth muscle cells of small (arcuate) arteries from the renal vasculature have a relatively low inward rectifier K+ current density and, consistent with this, do not exhibit Ba2+-sensitive K+ dilatations (Prior et al. 1998).

Characterization of cloned Kir2.1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes

Following the molecular characterization studies, we determined whether the RNA encoding the Kir2.1 channel protein cloned from isolated vascular smooth muscle cells demonstrated the same inwardly rectifying K+ currents as those observed in native vascular smooth muscle cells (Table 1). Previous studies have demonstrated that strong, inwardly rectifying K+ currents in native vascular smooth muscle cells are sensitive to extracellular K+ and low (μM) concentrations of Ba2+(Quayle et al. 1993; Robertson et al. 1996). It has previously been shown that a change in external K+ had a number of effects on Kir currents: (1) inward rectification shifted with EK; (2) Erev for the current was a function of the EK; and (3) inward conductance increased with external K+ concentration. Extracellular Ba2+ block has been characterized as being voltage and concentration dependent and due to the binding of Ba2+ ions within the membrane voltage field of the channel pore (Quayle et al. 1993; Robertson et al. 1996). Due to the relative specificity of Ba2+ for inward rectifier channels over other K+ channels in smooth muscle (such as KATP channels or KV channels) (Nelson & Quayle, 1995), Ba2+ has become a useful probe for investigating the functional role of Kir currents in the regulation of arterial (myogenic) tone (McCarron & Halpern, 1990; Knot et al. 1996; Prior et al. 1998; Johnson et al. 1998). Thus, if Kir2.1 is the molecular structure responsible for generating the strong, inwardly rectifying current in native vascular smooth muscle cells it should possess the above-mentioned characteristics when expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

Our studies demonstrate that expression of arterial Kir2.1 vascular in Xenopus oocytes does indeed result in a strong, inwardly rectifying K+ current which is inhibited by micromolar concentrations of extracellular Ba2+. The half-block constant for Ba2+ at −60 mV in our experiments was 3.5 μM which compares well with those of 2.2 or 2.1 μM reported previously for inward rectifier currents from cerebral and coronary myocytes, respectively (Quayle et al. 1993; Robertson et al. 1996). As expected for an ion binding within the membrane voltage field (Woodhull, 1973), the Kd for Ba2+ was an exponential function of the voltage (Fig. 6D). The Kd decreased e-fold per 25 mV hyperpolarization, which is similar to that reported in myocytes from rat cerebral (e-fold per 23 mV; Quayle et al. 1993) and coronary (e-fold per 25 mV; Robertson et al. 1996) arteries. The Kd(0) for Ba2+ was determined to be 41.7 μM, which again is similar to values previously reported in native cerebral (Kd(0) = 38.1 μM; Quayle et al. 1993) and coronary (Kd(0) = 21.1 μM; Robertson et al. 1996) smooth muscle cells, and similar to the Kd(0) reported for murine Kir2.1 (Kd(0) = 62 μM; Shieh et al. 1998). The slope of Ba2+ inhibition in Xenopus oocytes expressing Kir2.1 is identical (0.51) to that measured previously in native coronary myocytes (0.51; Robertson et al. 1996), and similar to that reported for murine Kir2.1 (μ= 0.54; Shieh et al. 1998), consistent with Ba2+ binding halfway down the channel pore.

In addition to block by Ba2+, inward rectifier currents in vascular smooth muscle cells have also been reported to be sensitive to external Cs+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations (Quayle et al. 1993; Robertson et al. 1996). External Cs+ inhibition of inward rectifier K+ currents in native vascular smooth muscle cells has been determined to be voltage dependent whereas Ca2+ and Mg2+ block were relatively voltage independent. In fact, the effect of Ca2+ and Mg2+ on Kir2.1 channel properties has also not been examined. External Cs+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ inhibited Kir2.1 currents in Xenopus oocytes (Figs 8 and 9). Inhibition by Cs+ was highly sensitive to voltage whereby block increased e-fold per 13 mV of membrane hyperpolarization. Also, the slope of Cs+ block in Xenopus oocytes expressing Kir2.1 was 1.95 (Fig. 8), similar to that previously described (μ= 1.57) by Abrams and colleagues (1996) for murine Kir2.1. These findings are consistent with those previously reported by Robertson et al. (1996) in coronary myocytes (Cs+ block increased e-fold per 17 mV and the slope was 1.51). In contrast to Cs+ block, external Ca2+ and Mg2+ block of cloned Kir2.1 currents were was relatively unaffected by voltage (Fig. 9). External Ca2+ or Mg2+ (5 mM) reduced Kir2.1 currents in Xenopus oocytes by 32 or 47.5 % (at −60 mV), while similar conditions have been reported to inhibit 47 or 41 % of inward rectifier current in native coronary myocytes. The lack of voltage dependence of Ca2+ and Mg2+ block suggests that the Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding sites are superficial. These results suggest that the cloned Kir2.1 possesses the same low-affinity blocking site(s) for Ca2+ and Mg2+ as the strong, inwardly rectifying K+ currents present in native vascular myocytes.

Electrophysiological evidence that Kir2.1 (and not Kir2.2 or 2.3) encodes for the inward rectifier potassium channel in vascular smooth muscle

RT-PCR on isolated smooth muscle cells provided molecular evidence for Kir2.1 in arterial smooth muscle (Figs 1 and 2). Transcripts for the other known members of the Kir2 family (2.2 and 2.3) were not present (Fig. 1; Table 1). Barium, caesium, calcium and magnesium block of inward rectifier potassium currents in native arterial myocytes and the expressed Kir2.1 currents in oocytes were quantitatively very similar (Table 1), consistent with the idea that Kir2.1 encodes the inward rectifier in arterial myocytes. In further support of this idea, caesium blocked expressed Kir2.2 and Kir2.3 currents with at least 100-fold higher affinity than it blocked Kir2.1 currents or native arterial smooth muscle currents (Morishige et al. 1994; Takahashi et al. 1994). In addition Kir2.2 currents exhibited pronounced inactivation at negative voltages, unlike native inward rectifier currents, and Kir2.1 and Kir2.3 currents (Table 1). Our study also provides the first measurements of external calcium and magnesium block of cloned Kir2.1 channels (Fig. 9). Barium block appears to be similar for all three subtypes, although it has not been quantitatively examined for Kir2.2 and 2.3 currents. Therefore, the electrophysiological profile (barium, caesium, magnesium and calcium block as well as inactivation) of inward rectifier potassium currents in arterial myocytes is consistent with the properties of Kir2.1 channels and does not correspond to either Kir2.2 or 2.3 currents (Table 1).

In conclusion, the molecular biological results coupled with the electrophysiological and pharmacological studies performed on native cells and oocytes expressing Kir2.1 channels suggest that the molecular structure of the channel responsible for generating strong inwardly rectifying potassium currents in vascular smooth muscle cells consists of Kir2.1 subunits. With the molecular target now identified, future studies will focus on the relationship of transmitter regulation on Kir2.1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes and Kir current in native cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rebecca Walker for technical assistance, Dr Alan Segal for assistance in setting up the oocyte system, and Dr Del Eckman for collection of arteries. This work was supported by NIH grants (HL44455, HL51728 and DK41315) to B.H. and M.T.N. K.K.B. and J.H.J. are postdoctoral fellows of the American Heart Association, Western States Affiliate and Vermont/New Hampshire Affiliate, respectively.

References

- Abrams CJ, Davies NW, Shelton PA, Stanfield PR. The role of a single aspartate residue in ionic selectivity and block of a murine inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.1. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;493:643–649. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccorsi A, Hermsmeyer K, Aprigliano O, Smith CB, Bohr DF. Mechanism of potassium-induced relaxation in arterial smooth muscle. Blood Vessels. 1977;14:261–276. doi: 10.1159/000158133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FR, Hirst GD. Inward rectification in submucosal arterioles of guinea-pig ileum. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;404:437–454. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FR, Hirst GD, Silverberg GD. Inward rectification in rat cerebral arterioles; involvement of potassium ions in autoregulation. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;404:455–466. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry P, Pearson WL, Nichols CG. Protein kinase C inhibition of cloned inward rectifier (HRK1/KIR2.3) K+ channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;495:681–688. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst GDS, Edwards FR. Sympathetic neuroeffector transmission in arteries and arterioles. Physiological Reviews. 1989;69:546–604. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.2.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst GDS, Silverberg GD, Van Helden DF. The action potential and underlying ionic currents in proximal rat middle cerebral arterioles. The Journal of Physiology. 1986;371:289–304. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TD, Marrelli SP, Steenberg ML, Childres WF, Bryan RM., Jr Inward rectifier potassium channels in the rat middle cerebral artery. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:R541–547. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.2.R541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LN, Linder E. The action of excess Na, Ca and K on the coronary vessels. American Journal of Physiology. 1938;124:155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kleber AG. Resting membrane potential, extracellular potassium activity, and intracellular sodium activity during acute global ischemia in isolated perfused guinea pig hearts. Circulation Research. 1983;52:442–450. doi: 10.1161/01.res.52.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knot HJ, Zimmermann PA, Nelson MT. Extracellular K+-induced hyperpolarizations and dilatations of rat coronary and cerebral arteries involve inward rectifier K+ channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:419–430. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama H, Morishige K-I, Takahashi N, Zanelli JS, Fass DN, Kurachi Y. Molecular cloning, functional expression and localization of a novel inward rectifier potassium channel in the rat brain. FEBS Letters. 1994;341:303–307. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo Y, Baldwin TJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Primary structure and functional expression of a mouse inward rectifier potassium channel. Nature. 1993;362:127–133. doi: 10.1038/362127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron JG, Halpern W. Potassium dilates rat cerebral arteries by two independent mechanisms. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;259:H902–908. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.3.H902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishige K-I, Takahashi N, Findlay I, Koyama H, Zanelli JS, Peterson C, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Mori N, Kurachi Y. Molecular cloning, functional expression and localization of an inward rectifier potassium channel in the mouse brain. FEBS Letters. 1993;336:375–380. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80840-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishige KI, Takahashi N, Jahangir A, Yamada M, Koyama H, Zanelli JS, Kurachi Y. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a novel brain-specific inward rectifier potassium channel. FEBS Letters. 1994;346:251–256. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:C799–822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior HM, Webster N, Quinn K, Beech DJ, Yates MS. K(+)-induced dilation of a small renal artery: no role for inward rectifier K+ channels. Cardiovascular Research. 1998;37:780–790. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00237-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quayle JM, Dart C, Standen NB. The properties and distribution of inward rectifier potassium currents in pig coronary arterial smooth muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:715–726. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quayle JM, McCarron JG, Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Inward rectifier K+ currents in smooth muscle cells from rat resistance-sized cerebral arteries. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;265:C1363–1370. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.5.C1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson BE, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Inward rectifier K+ currents in smooth muscle cells from rat coronary arteries: Block by Mg2+, Ca2+, and Ba2+ American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:H696–705. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.2.H696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh R-C, Chang J-C, Arreola J. Interaction of Ba2+ with the pores of the cloned inward rectifier K+ channels Kir2.1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1998;75:2313–2322. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77675-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber FE, Wilson DA, Hanley DF, Traystman RJ. Extracellular potassium activity and cerebral blood flow during moderate hypoglycemia in anesthetized dogs. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;256:H1774–1780. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.6.H1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Morishige K-I, Jahangir A, Yamada M, Findlay I, Koyama H, Kurachi Y. Molecular cloning and functional expression of cDNA encoding a second class of inward rectifier potassium channels in the mouse brain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:23274–23279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Töpert C, Doring F, Wischmeyer E, Karschin C, Brockhaus J, Ballanyi K, Derst C, Karschin A. Kir2.4: a novel K+ inward rectifier channel associated with motoneurons of cranial nerve nuclei. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:4096–4105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-11-04096.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb RC, Bohr DF. Potassium-induced relaxation as an indicator of Na+, K+-ATPase activity in vascular smooth muscle. Blood Vessels. 1978;15:198–207. doi: 10.1159/000158166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JN, Lamp ST, Shine KI. Cellular potassium loss and anion efflux during myocardial ischaemia and metabolic inhibition. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:H1165–1175. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wischmeyer E, Lentes KU, Karschin A. Physiological and molecular characterization of an IRK-type inward rectifier potassium channel in a tumour mast cell line. Pflügers Archiv. 1995;429:809–819. doi: 10.1007/BF00374805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhull AM. Ionic blockage of sodium channels in nerve. Journal of General Physiology. 1973;61:687–708. doi: 10.1085/jgp.61.6.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]