Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) levels were measured in the corpus cavernosum of urethane-anaesthetized rats by using differential normal pulse voltammetry with carbon fibre microelectrodes coated with a polymeric porphyrin and a cation exchanger (Nafion). A NO oxidation peak could be recorded at 650 mV vs. a Ag-AgCl reference electrode every 100 s.

This NO signal was greatly decreased by the NO synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), given by local and systemic routes, and enhanced by the NO precursor L-arginine. Treatment with L-arginine reversed the effect of L-NAME on the NO peak.

Both the NO signal and the intracavernosal pressure (ICP) were increased by electrical stimulation of cavernosal nerves (ESCN). However, the rise in the NO levels long outlived the rapid return to baseline of the ICP values at the end of nerve stimulation.

The ICP and the NO responses to ESCN were suppressed by local and systemic injections of L-NAME. Subsequent treatment with L-arginine of L-NAME-treated animals restored the NO signal to basal levels and the NO response to ESCN. The ICP response to ESCN was restored only in part by L-arginine.

The observed temporal dissociation between the NO and ICP responses could be accounted for by several factors, including the buffering of NO by the blood filling the cavernosal spaces during erection.

These findings indicate that an increased production of NO in the corpora cavernosa is necessary but not sufficient for maintaining penile erection and suggest a complex modulation of the NO-cGMP-cavernosal smooth muscle relaxation cascade.

Nitric oxide (NO) is thought to play an important regulatory role in penile erection. Several studies have found the enzymatic activity generating NO (NO synthase; NOS) in the penile erectile bodies, located in both nerve fibres and endothelial cells (Burnett et al. 1992; Dail et al. 1995). The relaxation of cavernous smooth muscle, a prime requirement for the initiation and maintenance of penile erection (Saenz de Tejada et al. 1991), is highly susceptible to pharmacological manipulations of NO.

In organ bath experiments, precontracted cavernosal tissue strips from various sources, including man, have been consistently found to relax in response to the addition of NO releasing substances (Ignarro et al. 1990; Rajfer et al. 1992). On the contrary, both the endothelium-dependent and the neurogenic relaxation of cavernosal muscle strips precontracted by α-adrenergic agonists are suppressed by drugs inhibiting the synthesis or actions of NO, such as NOS inhibitors, NO scavengers, and soluble guanylate cyclase inhibitors (Ignarro et al. 1990; Kim et al. 1991; Bush et al. 1992; Holmquist et al. 1992).

In vivo studies on anaesthetized rats and rabbits have also shown that the erectile responses to the electrical stimulation of the cavernous nerves (ESCN) can be prevented by treatments with NOS inhibitors (Holmquist et al. 1991; Burnett et al. 1992; Mills et al. 1992). Furthermore, the intracavernosal infusion of NO donors has been found to induce penile tumescence in dogs (Trigo-Rocha et al. 1993), cats (Wang et al. 1994), monkeys (Hellstrom et al. 1994) and humans (Truss et al. 1994).

However, little is known about the actual levels of NO in the corpora cavernosa and their possible change in the course of penile erection. This crucial information for understanding NO dynamics in the penis and its physiological significance to erectile phenomena has been missing for want of suitable methodologies.

Recent developments in the field of in vivo electrochemistry have made possible the direct assessment of NO levels in living organisms (for review see Malinski & Czuchajowski, 1996). Voltammetry with carbon-based electrodes has long been used for the detection in situ of easily oxidizable neurochemicals, such as the monoamine transmitters and related substances, in the living brain (for reviews see Mas et al. 1995; O'Neill et al. 1998). With some methodological modifications similar principles have been applied to the in vivo assessment of NO levels in various organs such as the brain (Burlet & Cespuglio, 1997), the heart (Pinsky et al. 1997) and the stomach (Mendez et al. 1997).

As shown in the present report, the in vivo voltammetry approach can be adapted for monitoring changes in NO levels in the rat penis in the course of erectile responses to ESCN and treatments with relevant drugs. This animal model has proved to be useful in pharmacological and surgical studies on the neural pathways, transmitters and hormones involved in penile erection and detumescence (e.g. Burnett et al. 1992; Mills et al. 1992; Rampin et al. 1994; Lugg et al. 1996; Reilly et al. 1997a, b).

METHODS

Animals

The experiments were done on Sprague-Dawley rats (250-300 g) reared at the University of La Laguna (ULL) Animal Facility. The animals were housed three to a cage in a 12 h:12 h light-dark cycle with free access to standard rat chow and tap water. The experimental procedures complied with national regulations for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the local ethics committee.

Surgical procedures

The animals were anaesthetized with urethane (1 g kg−1; i.p.) and placed on a homeothermic blanket to keep body temperature at 37°C. A polyethylene cannula was inserted into the trachea to maintain airway patency. The skin covering the penile glans and shaft was removed and the abdomen was opened by a midline suprapubic incision to allow access to the cavernous bodies and nerves, respectively.

The depth of anaesthesia was checked periodically by absence of the foot withdrawal reflex. No supplementary doses of the anaesthetic were needed in these studies. At the end of the experiments the animals were killed with an anaesthetic overdose.

Pressure recordings

To monitor intracavernosal pressure (ICP) a 23-gauge needle was inserted at mid-length of the penile shaft pointing towards its base. The arterial pressure (AP) was measured through a carotid line. The arterial and cavernosal catheters were connected via PE50 tubing filled with heparinized saline (200 units ml−1) to pressure transducers (Statham, Model P23Db, Hato Rey, PR, USA). The amplified signals were digitalized with an acquisition card model FPC-011 (Flight Tech, Southampton, UK) at a rate of 4 s−1 and stored in a PC compatible computer.

Electrostimulation of the cavernosal nerve (ESCN)

The major pelvic ganglion was identified at one side of the dorsolateral prostate (Quinlan et al. 1989) and used as a landmark for placing the stimulating electrode on the emerging cavernosal nerve. The exposed ends (3 mm in length, 2-3 mm apart) of a bipolar platinum electrode were hooked around the cavernosal nerve. A square wave stimulator (S48, Grass Instrument Co, West Warwick, RI, USA) was used to deliver 1 ms pulses of 6 V at 12 Hz for 1 min. These stimulation parameters, based on previous descriptions (e.g. Burnett et al. 1992; Mills et al. 1992; Rampin et al. 1994; Lugg et al. 1996; Reilly et al. 1997a, b), were found to induce a consistent ICP increase to 40-60 % of the mean arterial pressure levels, thought suitable for assessing experimental manipulations from which both increasing and decreasing effects can be expected. At least 10 min were allowed to elapse between successive stimulations.

Voltammetric recordings

The electrochemical procedure used derives from the approach first described by Malinski & Taha (1992). It is based on the catalytic oxidation of NO on polymeric metalloporphyrins. Differential normal pulse voltammetry (DNPV) with carbon fibre microelectrodes covered with a polymeric porphyrin film and coated with a perfluorinated polyacid with cation exchange properties (Nafion) was performed as previously described (Mendez et al. 1997). The working electrode consisted of a carbon fibre (30 μm in diameter, 500 μm in length) which was covered by electro-deposition, using differential pulse voltammetry, with a polymeric film of tetrakis (3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl) porphyrin containing nickel as the core metal (Interchim, Montluçon, France) and successive dippings (total time 15 s) into a 5 % solution of Nafion (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI, USA). These electrode coatings are aimed, respectively, to enhance the NO signal and to exclude interfering anions such as nitrite (Malinski & Czuchajowski, 1996). The electrodes thus prepared can detect tissue levels of NO in the nanomolar range (Malinski & Czuchajowski, 1996; Mendez et al. 1997).

The working electrode was mounted into a telescopic carrier assembly previously described (see Mas et al. 1995 for construction details) to allow the insertion into the cavernous bodies. An attached polymicro tubing allowed the infusion of drugs at the vicinity of the electrode. The tip of the electrode carrier (0.7 mm in diameter, 2 mm in length) was inserted through the tunica albuginea, near the glans, and the microelectrode was extruded undamaged to the cavernosal space. A standard three-electrode potentiostat circuit, as commonly used for in vivo voltammetry recordings (O'Neill et al. 1998), was completed with a reference electrode (Ag-AgCl) and a counter (or auxiliary) electrode made of stainless steel, which were attached to nearby abdominal muscles and kept wet with saline-soaked pads.

Voltammetric recordings were made with a microprocessor-controlled potentiostat system (Bioelectrochemical Analyser, ULL, Tenerife, Spain). The following DNPV parameters were used: potential range, -100 to 1000 mV; scan rate, 10 mV s−1; pulse amplitude, 40 mV; pulse duration, 40 ms; and prepulse duration, 50-120 ms. In these conditions, NO solutions show an oxidation peak at approximately 650 mV. This signal increases linearly following the addition of NO. Nitrite, the main metabolite of NO, has no effect on the voltammogram at concentrations below 0.2 mM, i.e. well over the physiological range. Likewise, no interference was found from other relevant substances such as nitrates or hydrogen peroxide. Freshly prepared solutions of S-nitrosothiols (such as S-nitroso-N-acetyl-D,L-penicillamine; SNAP) have no effects in the NO voltammogram initially, although a progressive development of the 650 mV peak can be observed eventually, indicating the well-known chemical hydrolysis which these compounds undergo to release NO. Peroxynitrite does not seem to interfere with the NO voltammograms either. This is supported by the observation that 3-morpholinosydnonimine N-ethylcarbamide (SIN-1) solutions show no appreciable NO signal. This compound is known to release both NO and superoxide which react to form peroxynitrite so rapidly that NO is consumed (Christodoulou et al. 1996).

NO solutions

Solutions of NO for calibrating the electrodes and in vivo infusion were freshly prepared before the experiments. Briefly, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was bubbled with pure nitrogen for 30 min in a septum-sealed vial and the head space was replaced with nitrogen. This deoxygenated PBS was then bubbled for 20 min with gaseous nitric oxide (Air Liquide, Paris) that had been scrubbed through 5 M NaOH and distilled water. The NO concentration in this solution was 0.17 mmol l−1, as determined by chemiluminescence assay, and remained stable for at least 4 h in sealed vials. The stock NO solution was serially diluted with nitrogen-purged PBS in sealed test tubes to the working concentrations.

Drugs

L-Arginine and NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (Sigma Chemical Co) were dissolved in saline. They were injected systemically (femoral vein) at doses of 25 and 3 mg kg−1, respectively, or given in the corpus cavernosum as a 60 μl infusion containing 40 μM L-arginine or 30 μM L-NAME. None of these compounds had effects on the voltammogram when tested in vitro at the concentrations used in the present study.

Data analysis

Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as means ±s.e.m. The statistical significance of the changes in the electrochemical or pressure signals was assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures. When F values were found to be significant at the P < 0.05 level, post hoc comparisons were made by Dunnett's test, using the mean value of the five baseline recordings immediately preceding the experimental manipulation as the control group. Comparisons between different treatments were made by one- or two-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test.

RESULTS

Voltammetric signal

Following the insertion of the microelectrode in the corpus cavernosum, a small oxidation current could be detected at approximately 650 mV (range 600-700 mV) (Fig. 1). This voltage coincides with the oxidation peak found when placing the electrode in NO solutions. The intracavernosal infusion of NO solutions in the vicinity of the electrode increased the NO signal in a dose-related manner (Fig. 1A). Similar changes were observed by stimulating the cavernous nerve (Fig. 1A). As can be noticed by comparing these figures, the half-wave potentials (i.e. the voltage value at which the maximum peak height is observed) showed some variation between the different animals. That can be accounted for by several factors including small differences in the electrode characteristics, pH, temperature, etc. However, their stability within the same preparation is remarkable.

Figure 1. Voltammograms recorded in the corpus cavernosum of two urethane-anaesthetized rats before (BL) and after infusion of different NO solutions in the vicinity of the electrode (A) and electrical stimulation of the cavernous nerve (ESCN) (B).

Traces 1-3 in B are consecutive recordings in the same animal, at 100 s intervals, following ESCN. It usually takes 2-3 scans after nerve stimulation for the NO signal to reach maximal values (in this example, in the second scan, trace 2); it then decays slowly (trace 3).

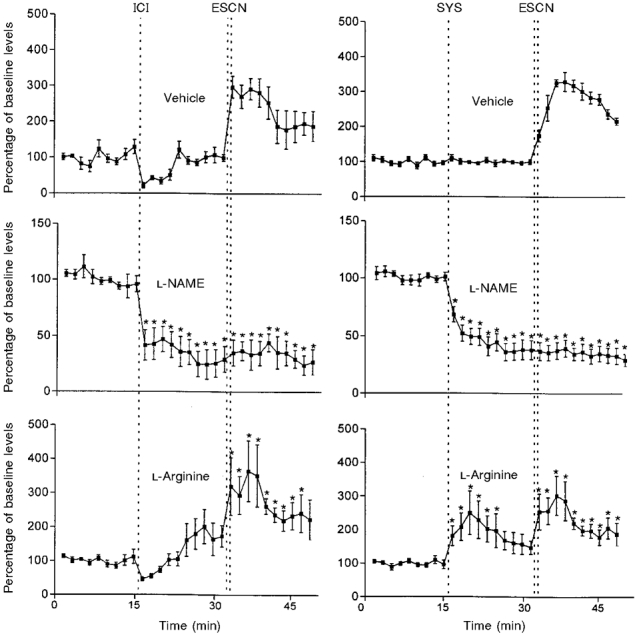

Effects of NO related drugs on the basal signals

The size of the basal NO signal was increased by the local or systemic injection of the NO precursor L-arginine and decreased by the NOS inhibitor L-NAME (Fig. 2). The intracavernosal injections of vehicle and L-arginine were followed by a transient decrease in the NO peak lasting 7 min approximately, then recovering to basal levels in the vehicle-treated group and above them in the animals given L-arginine. Such a phenomenon, probably reflecting a dilution effect, was not observed when these treatments were given systemically. In the animals treated with L-NAME by either route there was a fall of the NO signal, sharper in those given intracavernous injections, remaining low thereafter. The suppression of the NO signal induced by L-NAME was reversed by L-arginine (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Effects of intracavernosal (ICI) or intravenous (SYS) injections (dotted lines) of the NO precursor L-arginine and the NOS inhibitor L-NAME, alone or in combination, on the size of the NO signal recorded in the corpus cavernosum.

Data are means ±s.e.m.; 7-11 animals per group; * P < 0.05 vs. baseline levels. The doses used were as follows: ICI, a 60 μl infusion of 40 μM L-arginine or 30 μM L-NAME; SYS, L-arginine, 25 mg kg−1; SYS, L-NAME, 3 mg kg−1. The initial drop in the voltammetric signal following the ICI of vehicle denotes a transient dilution effect.

Effects of ESCN

When ESCN was applied to non-treated animals ICP rose from baseline values of 4 ± 1 mmHg up to 49 ± 1 mmHg, falling rapidly to basal levels when the stimulation was terminated (see example in Fig. 3A). The simultaneous recording of the NO electrochemical signal showed a clear increase in the first scan obtained after the ESCN, usually reaching its maximal height in the ensuing 2-3 scans, followed by a slow decline (Fig. 3A, see also Fig. 1A).

Figure 3. Effects of cavernous nerve stimulation (ESCN).

A, changes in the NO electrochemical signals recorded in the corpus cavernosum. Data are means ±s.e.m.; n = 12

Drug effects on the NO and ICP responses to ESCN

The changes in the basal NO signal induced by L-NAME or L-arginine treatments given prior to nerve stimulation (Fig. 4) were similar to those shown in Fig. 2. The response of the NO signal to ESCN was prevented by intracavernosal and systemic injections of L-NAME (Fig. 4), which also suppressed the pressure response. The maximal ICP values found during the stimulation of L-NAME treated animals were 7 ± 1 mmHg for both the intracavernosal and the systemic routes.

Figure 4. Effects of pretreatments with L-arginine or L-NAME on the response of the NO voltammetric signal to ESCN.

Data are means ±s.e.m.; 6-9 animals per group; *P < 0.05 vs. baseline preinjection levels. See legends to Figs 2 and 3 for further details.

Pretreatment with L-arginine alone had little influence on both the NO and ICP responses to ESCN. Thus, the changes in NO following ESCN were not significantly different from those observed in the vehicle-injected groups (Fig. 4). Likewise, the maximal ICP values (mmHg) found after ESCN were 42 ± 3 (intracavernosal vehicle), 40 ± 4 (intracavernosal L-arginine), 46 ± 4 (intravenous vehicle) and 48 ± 3 (intravenous L-arginine).

However, L-arginine treatment reversed to a large extent the inhibitory effects of L-NAME given by the same routes on the NO and the ICP responses to nerve stimulation. The changes in size of the NO peaks recorded after ESCN in the L-NAME treated animals given additional L-arginine (Fig. 5) were fairly similar to those observed in the absence of L-NAME (Fig. 4). A two-way ANOVA showed no significant differences between these responses. On the contrary, the ICP response to ESCN was restored only in part by L-arginine injections. Thus, the maximal ICP values found after ESCN in L-NAME + L-arginine treated animals were 22 ± 5 mmHg and 25 ± 5 mmHg for the intracavernosal and systemic routes respectively. They were significantly different (P < 0.01) from those found in the animals given either vehicle or L-NAME alone by the same routes (described above).

Figure 5. Effects of L-arginine on the NO signal recorded before and after ESCN in L-NAME pretreated rats.

Data are means ±s.e.m.; 5 animals per group; *P < 0.05 vs. baseline preinjection levels. See legends to Figs 2 and 3 for further details.

DISCUSSION

The present data show that an oxidation current similar to that found in NO solutions, both in vitro and infused into the penis, can be monitored at relatively short intervals in the corpora cavernosa of living animals. The electrochemical signal also responded in a predictable manner to pharmacological interventions having well-known stimulatory (L-arginine) and inhibitory (L-NAME) effects on NO production. Furthermore, this signal increased following stimulation of the cavernous nerve concurrently with the ICP rise, even though there were differences in the duration of these responses (discussed below). As pointed out in the Methods section, other relevant compounds such as nitrite, nitrate, hydrogen peroxide, peroxynitrites or S-nitrosothiols do not seem to interfere significantly with the NO oxidation current measured at 650 mV. Therefore, by meeting many of the criteria commonly accepted for the identification of in vivo voltammetry signals (e.g. Stamford, 1991; O'Neill et al. 1998) it can be reasonably concluded that the 650 mV oxidation peak found in the rat corpus cavernosum corresponds to NO.

The findings on ICP changes induced by ESCN agree generally with previous reports using comparable protocols (e.g. Burnett et al. 1992; Mills et al. 1992; Rampin et al. 1994; Reilly et al. 1997a). In the present study they were associated with similar effects on the NO signal, although with a different time course. Whereas the change in ICP followed closely the nerve stimulation, the NO electrochemical signal reached maximum values after ESCN had ended and remained elevated for several minutes afterwards. According to the concept of NO as a main mediator of the cavernous smooth muscle relaxation underlying penile erection, an increase in NO levels could be expected before the ICP change. In fact, the present findings do not necessarily contradict that view. Since NO is rapidly and irreversibly ‘trapped’ by haemoglobin (Archer, 1993; Gow & Stamler, 1998), an initial NO rise would be buffered by the blood entering the cavernous lacunar spaces during erection. This phenomenon is illustrated by the substantial decrease in the voltammetric signals observed when NO solutions are added to blood as compared with PBS (Fig. 6). It is therefore plausible that the NO levels at which the target smooth muscle cells are exposed during nerve stimulation are much higher than those measured with the intracavernosal sensor. The dilution of NO in the expanded erectile tissue could also limit the rise of its electrochemical signal. Probably, when the blood is drained out of the corpora at detumescence, the NO signal is no longer attenuated by the above factors and can reach maximum levels.

Figure 6. Size of the NO voltametric signal recorded in PBS or rat arterial blood immediately after adding NO to a final concentration of either 2 or 10 μmol l−1.

Data are means ±s.e.m. of 3 electrodes; * P < 0.01 vs. PBS. Note the change in scale.

The half-life of NO in biological systems is not known precisely, but according to most estimates is in the order of seconds (see Wood & Garthwaite, 1994 and references therein). Thus, the persistence of high NO electrochemical signals for more than 10 min after finishing the ESCN, when the concomitant rise in ICP had long vanished, suggests an increased release of NO outliving the neural erectogenic signals. One possibility is that the activation of NOS enzyme activity could extend beyond the end of nerve stimulation. This interpretation is consistent with the observations by Lugg et al. (1996) in castrated rats. These authors reported increased NOS activity in the penises excised at the peak of the erectile response to nerve stimulation as well as 5 min after its termination. It is also possible that some of the post-erection rise in NO levels could be due to its release from protein S-nitrosothiols formed during the stimulation-induced increase in NO levels. It has been proposed that NO can be ‘stabilized’ by attaching to these molecules as S-nitrosothiol groups, and it is believed that they can mediate some of the vascular actions of NO (Stamler et al. 1992), although whether that involves the release of NO is controversial. As pointed out in the Methods section, in vitro testing of low-molecular weight S-nitrosothiols, such as SNAP, shows an initial absence of electrochemical signals followed some minutes later by an increasing NO peak. This phenomenon, indicative of the release of NO from S-nitrosothiols, is accelerated in vivo.

Whatever the mechanism(s) underlying the observed post-ESCN increase in NO levels in the cavernous bodies, the present data show that they remained elevated when the erectile responses had subsided. These finding suggests that simply a high concentration of NO in the cavernosal tissue is not sufficient for sustaining the erectile response.

The above interpretation is also supported by pharmacological evidence from in vivo rat preparations fairly similar to the one used in the present study. Thus, whereas NOS inhibitors have been consistently found to block the ICP response to cavernosal nerve stimulation (e.g. Burnett et al. 1992; Reilly et al. 1997b; and the present data), the infusion of NO donors such as nitroglycerine (Mills et al. 1992), sodium nitroprusside (Reilly et al. 1997a, b) or L-arginine (Reilly et al. 1997b; this study) does not increase or prolong it substantially. Likewise, in the treatment of erectile dysfunction in humans, the intracavernosal injection of NO donors has shown poorer results than other vasoactive substances such as prostaglandin E1 (Porst, 1993; Wegner et al. 1995).

Therefore, whereas an overwhelming body of pharmacological evidence indicates that the production of NO in the erectile bodies is needed for the development of penile erection, it does not seem so clear that the persistence of elevated NO levels would suffice for maintaining it. There are several possible explanations for this discrepancy. One comes from the fact that NO, even if essential for erection, is not the only transmitter in the erectile nerves (for review see Sjöstrand & Klinge, 1995). Thus, it could be that the observed erectile response to nerve stimulation involves some additional co-mediator(s) being rapidly cleared upon termination of ESCN. Another possibility is that the nitrergic system in the present studies and those cited in the preceding paragraph was supramaximally stimulated. In such case, neither the persistently elevated NO levels derived from endogenous sources following nerve stimulation nor the administration of exogenous NO donors would enhance the response of the effector smooth muscle. It should be noted that the nerve stimulation parameters used in this and the preceding studies were chosen on the basis of eliciting consistent ICP responses in the anaesthetized rat. However, the physiological firing pattern of the erectile nerves is not known (Sjöstrand & Klinge, 1995).

The main mechanism for the erectogenic action of NO is thought to involve the stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase in the target smooth muscle cells. The resulting increase in cGMP levels would relax the muscle fibres via the decrease in intracellular Ca2+ (see Burnett, 1995, for review). The success of type 5 phosphodiesterase inhibitors, which extend the life of cGMP, in enhancing penile erection (Boolell et al. 1996) lends further support to this concept. Nevertheless, it should be kept in mind that there are cGMP-mediated vasodilation mechanisms not requiring NO (e.g. Rapoport, 1986). They also can be present in the penis; recent pharmacological studies using a rat preparation similar to the present work have suggested an additional pathway for the erectile response involving cGMP but independent of NO (Reilly et al. 1997a). Furthermore, changes in cGMP levels have been found dissociated from the vasodilatation responses in some experiments (Ignarro et al. 1984). All these data indicate complex relationships between the levels of NO and cGMP and the relaxation of smooth muscle in blood vessels and the cavernosal trabeculae. Probably, a variety of modulatory mechanisms operate at different steps of the NO-cGMP-smooth muscle relaxation cascade. This could explain that an increased level of NO is not necessarily accompanied by a relaxation (i.e. erection) response.

The assessment of NO levels in the penis in vivo has been previously attempted by indirect means. Thus, nitrite and nitrate levels have been measured in the blood drawn from the cavernous bodies of human subjects undergoing erections, although no changes were found in these metabolites (Moriel et al. 1993). This is not surprising considering that the nitrites and nitrates found in biological fluids derive from a wide variety of sources, and can easily mask the contribution of locally produced NO.

The present report is the first demonstration of a direct assessment of NO levels in the penis of animals undergoing changes in ICP thought to mimic physiological erections. The voltammetric technique used in this study (DNPV) was chosen because it allows a clearer identification of electrochemical signals (O'Neill et al. 1998), even at the cost of a relatively slow sampling rate. It is unlikely that with such wide-range scanning techniques the recording speed will be increased far beyond the 100 s interval used in these experiments. That could be improved by using the much faster chronoamperometric approach which requires, however, a most accurate characterization of the electrochemical signals. Ongoing studies in our laboratory indicate that both techniques can be combined advantageously.

Regardless of their sampling rate, the in vivo electrochemistry procedures for monitoring NO levels share the constraint that the recordings must be interrupted at the time of the electrical field stimulation, since the applied current will mask the relatively weak electrochemical signals. That could be avoided by using alternative methods based on different principles. At present, NO can be measured in vitro by a variety of methodologies such as electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, chemiluminescence assay, and methaemoglobin spectrophotometry (Archer, 1993). It is likely that some of these approaches, especially the last one, could be adapted in the future for the detection of this important, yet elusive, messenger molecule in tissues of living animals. Such methodological developments, as with the in vivo voltammetry approach shown by the present report, could provide valuable tools for elucidating the physiological role of NO in various aspects of reproductive behaviour.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant FIS 96/0294 from the Spanish Ministry of Health.

References

- Archer S. Measurement of nitric oxide in biological models. FASEB Journal. 1993;7:349–360. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.2.8440411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boolell M, Allan MJ, Ballard SA, Gepi-Attee S, Muirhead GJ, Naylor AM, Osterloh IH, Gingel C. Sildenafil: an oral active type 5 cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor for the treatment of penile erectile dysfunction. International Journal of Impotence Research. 1996;8:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlet S, Cespuglio R. Voltammetric detection of nitric oxide (NO) in the rat brain: its variations throughout the sleep-wake cycle. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;226:131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett AL. Role of nitric oxide in the physiology of erection. Biology of Reproduction. 1995;52:485–489. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett AL, Lowenstein CJ, Bredt DS, Chang TSK, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: a physiologic mediator of penile erection. Science. 1992;257:401–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1378650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush PA, Aronson WJ, Buga GM, Rajfer J, Ignarro LJ. Nitric oxide is a potent relaxant of human and rabbit corpus cavernosum. Journal of Urology. 1992;147:1650–1655. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37671-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou D, Kudo S, Cook JA, Krishna MC, Miles A, Grisham MB, Murugesan R, Ford PC, Wink DA. Electrochemical methods for detection of nitric oxide. In: Packer L, editor. Methods in Enzymology, Nitric Oxide, part A, Sources and Detection of NO; NO Synthase. Vol. 268. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dail WG, Barba V, Leyba L, Galindo R. Neural and endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity in rat penile erectile tissue. Cell and Tissue Research. 1995;282:109–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00319137. 10.1007/s004410050463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow AJ, Stamler JS. Reactions between nitric oxide and haemoglobin under physiological conditions. Nature. 1998;391:169–173. doi: 10.1038/34402. 10.1038/34402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom WJG, Monga M, Wang R, Domer FR, Kadowitz PJ, Roberts JA. Penile erection in the primate: induction with nitric oxide donors. Journal of Urology. 1994;151:1723–1727. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmquist F, Hedlund H, Andersson KE. Characterization of inhibitory neurotransmission in the isolated corpus cavernosum from rabbit and man. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;449:295–311. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmquist F, Stief CG, Jonas U, Andersson KE. Effects of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-L- arginine on the erectile response to cavernous nerve stimulation in the rabbit. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1991;143:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1991.tb09236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro LJ, Burke TM, Wood KS, Wolin MS, Kadowictz PJ. Association between cyclic GMP accumulation and acetylcholine-elicited relaxation of bovine intrapulmonary artery. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1984;228:682–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro LJ, Bush PA, Buga GM, Wood KS, Fukuto JM, Rajfer J. Nitric oxide and cyclic GMP formation upon electric field stimulation causes relaxation of corpus cavernosum smooth muscle. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1990;170:843–850. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)92168-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N, Azadoi KM, Goldstein I, Saenz de Tejada I. A nitric oxide-like factor mediates nonadrenergic noncholinergic neurogenic relaxation of penile corpus cavernosum smooth muscle. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1991;88:112–118. doi: 10.1172/JCI115266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugg JA, Ng C, Rajfer J, González-Cadavid NF. Cavernosal nerve stimulation in the rat reverses castration-induced decrease in penile NOS activity. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:E354–361. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.2.E354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinski T, Czuchajowski L. Nitric oxide measurement by electrochemical methods. In: Feelisch M, Stamler JS, editors. Methods in Nitric Oxide Research. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. pp. 319–339. [Google Scholar]

- Malinski T, Taha Z. Nitric oxide release from a single cell measured in situ by a porphyrinic-based microsensor. Nature. 1992;358:676–678. doi: 10.1038/358676a0. 10.1038/358676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas M, Fumero B, Gonzalez-Mora JL. Voltammetric and microdialysis monitoring of brain monoamine neurotransmitter release during sociosexual interactions. Behavioural Brain Research. 1995;71:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00043-7. 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez A, Fernandez M, Barrios Y, Lopez-Coviella I, Gonzalez-Mora JL, Salido E, Bosch J, Quintero E. Constitutive NOS isoforms account for gastrical mucosa overproduction in uremic rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:G894–901. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.4.G894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills TM, Wiedmeier VT, Stopper VS. Androgen maintenance of erectile function in the rat penis. Biology of Reproduction. 1992;46:342–348. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriel EZ, Gonzalez-Cadavid N, Ignarro LG, Byrns R, Rajfer J. Levels of nitric oxide metabolites do not increase during penile erection. Urology. 1993;42:551–553. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90271-b. 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90271-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill RD, Lowry JP, Mas M. Monitoring brain chemistry in vivo: voltammetric techniques, sensors and behavioral applications. Critical Reviews in Neurobiology. 1998;12:69–72. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v12.i1-2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky DJ, Patton S, Mesaros S, Brovkovych V, Kubaszewski E, Grunfeld S, Malinski T. Mechanical transduction of nitric oxide synthesis in the beating heart. Circulation Research. 1997;81:372–379. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porst H. Prostaglandin E1 and the nitric oxide donor linsidomine for erectile failure: a diagnostic comparative study of 40 patients. Journal of Urology. 1993;149:1280–1283. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36367-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan DM, Nelson RJ, Partin AW, Mostwin JL, Walsh PC. The rat as a model for the study of penile erection. Journal of Urology. 1989;141:656–661. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40926-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajfer J, Aronson WJ, Bush P, Dorey FJ, Ignarro LJ. Nitric oxide as a mediator of relaxation of the corpus cavernosum in response to nonadrenergic, noncholinergic neurotransmission. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326:90–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201093260203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampin O, Giuliano F, Dompeyre P, Rousseau J-P. Physiological evidence of neural pathways involved in reflexogenic penile erection in the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1994;180:138–142. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90506-1. 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport R. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate inhibition of contraction may be mediated through inhibition of phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis in rat aorta. Circulation Research. 1986;58:407–410. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CM, Lewis RW, Stopper VS, Mills TM. Androgenic maintenance of the rat erectile response via a non-nitric-oxide-dependent pathway. Journal of Andrology. 1997a;18:588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CM, Zamorano P, Stopper VS, Mills TM. Androgenic regulation of NO availability in rat penile erection. Journal of Andrology. 1997b;18:110–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenz de Tejada I, Moroukian P, Tessier J, Kim JJ, Goldstein I, Frohrib D. The trabecular smooth muscle modulates the capacitor function of the penis. Studies on a rabbit model. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:H1590–1595. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.5.H1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöstrand NO, Klings E. Nitric oxide and the neural regulation of the penis. In: Vincent S, editor. Nitric Oxide in the Nervous System. London: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Stamford JA. In vivo voltammetry. In: Conn PM, editor. Methods in Neuroscience, Electrophysiology and Microinjection. Vol. 4. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 127–154. [Google Scholar]

- Stamler JS, Simon DI, Osborne JA, Mullins ME, Jaraki O, Michel T, Singel DJ, Loscalzo J. S-Nitrosylation of proteins with nitric oxide: synthesis and characterization of biologically active compounds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:444–448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigo-Rocha F, Aronson WJ, Hohenfellner M, Ignarro LJ, Rajfer J, Lue TF. Nitric oxide and cGMP: mediators of pelvic nerve-stimulated erection in dogs. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264:H419–422. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.2.H419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truss MC, Becker AJ, Djamillan MH, Stief CG, Jonas U. Role of the nitric oxide donor linsidomine chlorhydrate (SIN-1) in the diagnosis and treatment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1994;44:553–556. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(94)80058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Domer FR, Sikka SC, Kadowitz PJ, Hellstrom WJG. Nitric oxide mediates penile erection in cats. Journal of Urology. 1994;151:234–237. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34923-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner HEH, Knispel HH, Klän R, Miller K. Efficacy of linsidomine chlorhydrate, a direct nitric oxide donor, in the treatment of human erectile dysfunction: results of a double-blind cross over trial. International Journal of Impotence Research. 1995;7:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J, Garthwaite J. Models of the diffusional spread of nitric oxide: implications for neural nitric oxide signalling and its pharmacological properties. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90022-1. 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]