Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) concentrations were measured in dialysate from healthy human skin, in vivo, both at rest and during the inflammatory response to intradermal histamine or bradykinin. Changes in dialysate NO concentration, measured by electrochemical detection, were related to changes in dermal vascular perfusion, measured using scanning laser Doppler imaging.

Basal NO concentration in dermal microdialysate was 0·60 ± 0·14 μM (mean ± s.e.m.). Following the intradermal injection of histamine, a transient, time-dependent increase in NO concentration was measured in areas of skin incorporating the weal and in others incorporating the flare. The increase in NO concentration was associated with an increase in dialysate cGMP concentration in both the weal and flare areas.

Addition of NG-nitro-l-arginine-methyl ester (L-NAME, 5 mM) to the probe perfusate resulted in an inhibition of the histamine-induced increase in NO and cGMP. Moreover, the reduction in dialysate NO concentration was associated with a reduction in dermal vascular flux, both under basal conditions and within the weal and flare response.

These results demonstrate, by the use of microdialysis, that vasoactive mediators can be measured in healthy human skin in vivo. They provide direct evidence that endogenous concentration of NO increases during the inflammatory weal and flare response to histamine and that the increase in dermal NO concentration is associated with increases in cGMP concentration and dermal vascular perfusion, thus confirming a role for NO in vasoregulation in human skin.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a potent vasodilator implicated in the maintenance of resting vascular tone (Furchgott & Zawadzki, 1980; Palmer et al. 1987). In humans, the calcium-dependent constitutive endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) has been shown to be present in endothelium throughout the body (Moncada & Higgs, 1993), including that of the blood vessels of the papillary and deep dermis of normal skin (Weller, 1997). The participation of NO in the regulation of dermal vascular perfusion has been demonstrated in vivo, by inhibition of its production using competitive L-arginine-analogue inhibitors of NO synthase such as NG-nitro-L-arginine-methyl ester (L-NAME) and NG-monomethyl-L-arginine (L-NMMA) (Goldsmith et al. 1996). Both substances have been shown to reduce skin blood flow when infused intra-arterially (Coffman, 1994) or when administered locally by intradermal injection (Noon et al. 1996) and to inhibit variably the dermal vasodilator responses to body warming (Dietz et al. 1994) and UVB exposure (Warren, 1994a; Bunker et al. 1996).

As well as modulating microvascular tone in skin, NO has been implicated in the modulation of vascular permeability (Kubes, 1995) and in neurogenically mediated vasodilatation, where the response to mediators such as histamine, bradykinin, prostaglandin E2, calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP), substance P and vasoactive intestinal peptide can be reduced by inhibitors of NOS (Hughes & Brain, 1994; Warren et al. 1994b; Benrath et al. 1995; Bull et al. 1996). The aim of the current study was to measure the production of NO in human skin in vivo, both under resting conditions and during the inflammatory weal and flare response to intradermal injection of histamine or bradykinin by assay of nitric oxide and its oxidative products in tissue fluid sampled by dermal microdialysis.

Direct measurement of nitric oxide release from endothelium has proved difficult because of its short biological half-life, estimated to be 4-10 s in vitro (Palmer et al. 1987). In the tissue space the two main oxidative products of NO are nitrite (NO2−) and nitrate (NO3−), oxidation to the latter taking up to a further 20 min. Consequently, measurement of total nitrite (NO2−) and nitrate (NO3−) has been used as an indication of the generation of nitric oxide, both in vitro and in vivo during activation of endothelium by a range of agonists including bradykinin, L-arginine, acetyl choline and A-23187 (Tsukahara et al. 1993; Guo et al. 1996; Andoh & Kuraishi, 1997; Iversen et al. 1997). Inhibition of the release of NO2− and NO3− by L-NAME has been demonstrated in the gut (Iversen et al. 1997) as well as in isolated blood vessels and cultured endothelial cell preparations (Guo et al. 1996). Where NO oxidation products have been successfully measured in vivo, for example in mouse skin (Andoh & Kuraishi, 1997), rat brain (Ohta et al. 1994) and rabbit gastrointestinal tract (Iversen et al. 1997), they have been assayed in tissue fluid collected using microdialysis.

Previously, microdialysis, first developed for use in the brain (Bito et al. 1966), has been used in the skin to measure the release of histamine in allergic reactions (Petersen et al. 1996), to assay protein leakage from the inflamed microcirculation (Schmelz et al. 1997), to study the role of neuropeptides in the skin (Petersen et al. 1997; Schmelz et al. 1997) and to investigate skin metabolism (Lönnroth et al. 1987). In the current study, microdialysis probes implanted within the dermis of healthy human volunteers to lie adjacent to the upper dermal vascular plexus have been used to assay tissue fluid for NO and cGMP. Blood flux in the plexus was monitored using scanning laser Doppler imaging and related to changes in dialysate NO and cGMP concentrations. By assaying the dialysate samples for cGMP as well as NO, it was hoped to explore the importance of the NO-cGMP pathway in the vasodilator response in human skin.

Preliminary studies, in which we demonstrated our ability to detect changing levels of NO in microdialysate from human skin, have been reported previously (Clough et al. 1998b, c).

METHODS

Subjects

Thirty-one healthy volunteers were studied (17 males, 14 females, age range 21-56 years). Ten of these subjects participated in more than one part of this study. Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects and the study, performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the local ethics committee (JEC No. 84/97). Volunteers with dermatological problems, allergic disease, vascular disorders or those on prescribed medication were excluded from the study. All subjects were asked to refrain from taking any medication for 7 days and from smoking for 12 h prior to the time of study. On the study day, subjects were acclimatized to 22-23°C. Experiments were performed with the subject supine and their arms at heart level.

Dermal microdialysis

Microdialysis probes were manufactured from Cuprophane membranes from a renal dialysis capsule (GFE 18, Gambro, Hechingen, Germany) with a 2 kDa molecular mass cut off and external diameter 216 μm. The probes were inserted under topical local anaesthetic (EMLA, Astra, Kings Langley, UK) into the dermis of the volar surface of the forearm as described previously (Petersen et al. 1997). Ultrasound imaging (Dermascan C, version 3, Cortex Technology, Hadsund, Denmark) showed the probes to lie approximately 0·6-0·8 mm below the skin surface, and between 0·5 and 1·0 mm above the upper dermal vascular plexus. The total dialysis length of each probe was 20 mm. After a 2 h recovery period, the probes were perfused with sterile Ringer solution (Fresenius, Basingstoke, UK) containing (g (100 ml)−1): 0·86 NaCl; 0·03 KCl; 0·03225 CaCl2 at a rate of 5 μl min−1, using a microinfusion pump (CMA/100, CMA/Microdialysis, Stockholm, Sweden). In all experiments baseline samples were collected for up to 1 h prior to dermal provocation. Probes in which perfusion was not readily established were not used, as manipulation of the probe has been shown to cause local trauma and changes in dialysate concentration of vasoactive mediators (author's unpublished observation).

Measurement of dermal vascular flux

Dermal vascular perfusion was assessed using scanning laser Doppler imaging (scanning LDI) (Moor UK Ltd, Axminster, Wilts, UK) as described previously (Clough et al. 1998a,b). The scanner was mounted 30 cm from the skin surface and a maximum area of 7·5 cm × 7·5 cm scanned at each experimental site. Each scan comprised > 16 000 data points and took 2 min to collect (Fig. 1). Mean dermal perfusion was calculated from the calibrated scans using the manufacturer's software and expressed as scanning LDI perfusion units (PU). The area of the dermal vascular response was also calculated (Clough et al. 1998a). The effects of probe insertion and perfusion on resting blood flux were also routinely monitored. As in previous studies (Anderson et al. 1994; Clough et al. 1998a) the transient trauma caused by probe insertion was found to have resolved by the end of the 2 h recovery period. Sites where obvious trauma remained or a significant increase in scanning LDI mean blood flux was measured were not used and the probes removed.

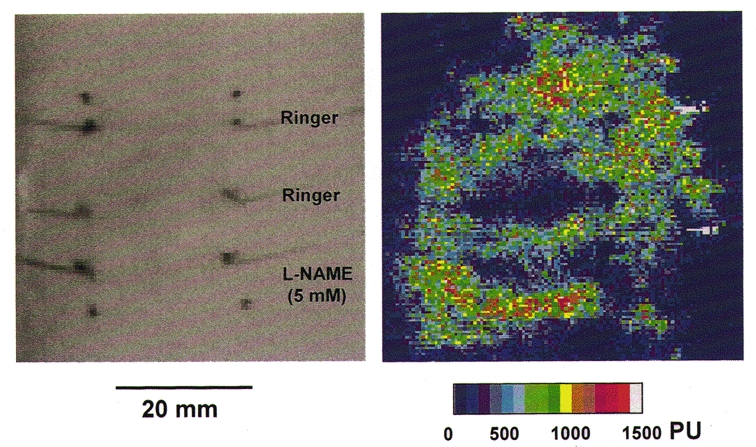

Figure 1. Scanning laser Doppler image of the blood flux 10 min after intradermal injection of histamine.

A high resolution scanning laser Doppler image of dermal blood flux taken 10 min after intradermal injection of histamine (15 μl of 1 μM). The injection was made adjacent to the central of three microdialysis probes inserted into the volar surface of the forearm. The upper two probes were perfused with Ringer solution and the lower one with L-NAME (5 mM). The same image is displayed as a grey scale image for the location of the fibres and as a coloured image used to calculate mean blood flux in a region 4 mm × 20 mm over each probe.

Intradermal provocation

A cutaneous vascular response was initiated by the intradermal injection of either histamine (1 μM in PBS, Sigma Poole, UK) or bradykinin (1 μM; Calbiochem Novabiochem, Nottingham, UK) using a 27 gauge needle U-100 insulin syringe (Myjector, Terumo Europe NV, Leuven, Belgium). Fifteen microlitres of agonist or its vehicle control were injected 1 mm to one side and parallel to one probe half-way along its length such that, on development of the inflammatory response, the probe lay within the area of the developing weal. A second probe, inserted at a separation of 20 mm from the first, lay within the area of the flare. In this study, dialysate samples were collected at 2 min intervals for up to 20 min after intradermal injection. Dermal vascular perfusion within the area of the weal and flare were assessed using scanning laser Doppler imaging before and 10 min following intradermal injection, at which time the weal and flare response had reached a steady state (Clough et al. 1998a).

Inhibition of NO synthase

To investigate the effects of inhibition of NO synthase on NO release and the dermal vascular response, two probes, separated by 20 mm, were inserted into each forearm of five subjects. After a recovery period all the probes were perfused with Ringer solution and baseline levels of dialysate NO and dermal perfusion established. The perfusate in one pair of probes, in one arm, was then switched to one containing 5 mM L-NAME (Sigma, UK) and dialysate samples collected from all the probes for a further 30 min. Dermal vascular perfusion was again measured at both sites. Histamine was then injected at both sites and dialysate collected, as described above. To compare the effects of L-NAME on dialysate NO and cGMP concentrations and local blood flux in the same flare response to intradermal histamine rather than in responses at different sites, three probes were inserted into one arm of an additional two subjects and perfused as shown in Fig. 1. In these experiments, histamine was injected close to the middle probe such that the weal developed over this probe and the flare over one probe perfused with Ringer solution and one with Ringer solution containing L-NAME. Dialysate was then collected as described above.

Validation of microdialysis technique

To investigate the ability of microdialysis to detect changes in dermal NO and to explore further the effects of NO on the dermal circulation, exogenous NO was delivered to the skin, transdermally, using a glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) patch (Transderm Nitro, 5 patches, Ciba Ltd, Camberley, UK). The patch was applied to the surface of the skin over two probes placed 20 mm apart after collection of 3 × 10 min 50 μl baseline samples. Collections of dialysate were made every 10 min for 1 h after patch application. Dermal perfusion was measured before and immediately after removal of the GTN patch.

Assays

Nitric oxide

The concentration of NO in dialysate was assayed using an amperometric NO sensor (IsoNO II meter, WPI, Stevenage, Herts, UK) sensitive to 1 nM NO. Five microlitre samples of either fresh or previously frozen dialysate were reduced using an acidic KI solution and the concentration of NO generated from nitrite in the dialysate measured. NO concentration in the samples was taken as peak signal values. Further reduction of the sample using a nitrate reductase (Nitralyser, WPI) showed the concentration of nitrate in the dialysate to be less than 10 % (6·6 ± 1·5 % nitrate measured in 78 basal samples). Accordingly, no allowance has been made for this in the final calculations of NO concentration in the dialysate. Analysis of samples stored at -20°C for up to14 days showed no significant change in nitrite levels.

Cyclic GMP

The concentration of cGMP in dialysate was assayed, following acetylation, using a commercially available competitive enzyme immunoassay with a detection limit of 2·97 fmol ml−1 (TiterZyme®, Perseptive Biosystems Inc., Framingham, MA, USA)

Evaluation of dialysis probe efficiency in vitro

The dialysis efficiency of the 2 kDa probes was measured in vitro, as described previously (Petersen et al. 1997). Essentially, dialysis probes were immersed in a bath containing either potassium nitrite or cGMP at a known concentration. The probes were perfused with solutions containing the same solute at a range of concentrations spanning the concentration in the bath. The effective loss from or recovery into the dialysis probe was calculated from the difference in the inflow and outflow solute concentrations. The recovery of nitrite-nitrate in vitro was estimated to be 89·5 ± 2·0 % at 25°C over a dialysis length of 20 mm at a flow rate of 5 μl min−1. For cGMP the efficiency of dialysis was 25 ± 5 %.

Statistical analysis

Dialysate NO and cGMP are expressed as concentrations measured in dialysate collected over each sampling period. Values are expressed as means ±s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test for paired data from each subject.

RESULTS

Basal NO concentration

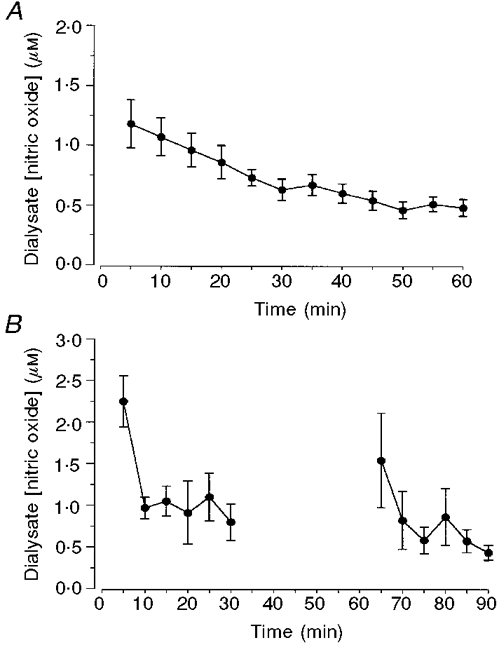

The basal concentration of NO in human skin in vivo, assayed as dialysable nitrite, showed marked inter- and intrasubject variability, with values ranging from 0·27 to 4·3 μM measured in 24 probes in 14 subjects. The mean value of NO in the first 5 min collection was 1·24 ± 0·19 μM. Continued dialysis of the tissue space resulted in a fall in dialysate NO concentration over the first 30 min of perfusion to 0·63 ± 0·09 μM in the 25-30 min dialysate sample (Fig. 2A). No further fall in dialysate NO was seen when perfusion was continued for up to 60 min. Consequently, changes in mediator concentration following dermal provocation were calculated from a resting value of NO concentration measured in the final (25-30 min) baseline dialysate sample. In four experiments where perfusion was stopped after an initial 30 min and then restarted 30 min later, NO concentration in the subsequent dialysate sample (1·10 ± 0·04 μM, 8 probes, 4 subjects) increased towards its value in the initial dialysate sample (1·24 ± 0·19 μM) before falling for a second time (Fig. 2B). The rate of fall in dialysate NO concentration during the second period of perfusion was similar to that during the first.

Figure 2. Effect of continued probe perfusion on dialysate NO concentration.

A, dialysate concentration of NO was measured in 25 μl (5 min) samples collected during continuous perfusion of probes with Ringer solution (5 μl min−1). Data are means ±s.e.m. from 12 probes in 6 subjects. B, dialysate NO concentration was measured in 25 μl (6 × 5 min) samples collected during a 30 min period of continuous probe perfusion. Perfusion was then stopped and restarted 30 min later. Dialysate was collected for a further 30 min (6 × 5 min). Data are means ±s.e.m. of 4 probes in 1 subject.

Dialysis of exogenous NO

NO concentration, measured as the concentration of nitrite in the dialysate collected from beneath a GTN patch, increased between four- and tenfold from baseline values of 0·64 ± 0·04 μM to a mean peak value of 4·58 ± 0·44 μM (range 2·3-6·6 μM) at 40-50 min (P < 0·001, 7 subjects). To assess to what extent GTN was bio-activated in the skin dialysate, samples were assayed for nitrate as well as nitrite. The concentration of nitrate in the dialysate samples collected during patch application, relative to that of nitrite, was not significantly different from that in the baseline samples collected prior to application of the patch. Vascular perfusion beneath the patch increased threefold, from a resting value of 158 ± 21 to 433 ± 54 PU measured immediately after removal of the patch. The area of vasodilatation was restricted to the site of application of GTN and did not extend beyond the patch margin.

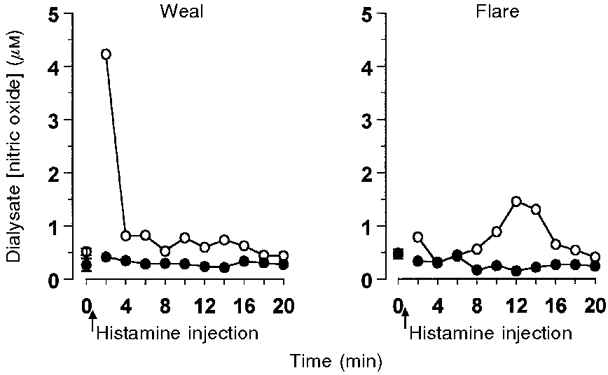

Time course of NO release in the weal and flare response to intradermal histamine or bradykinin

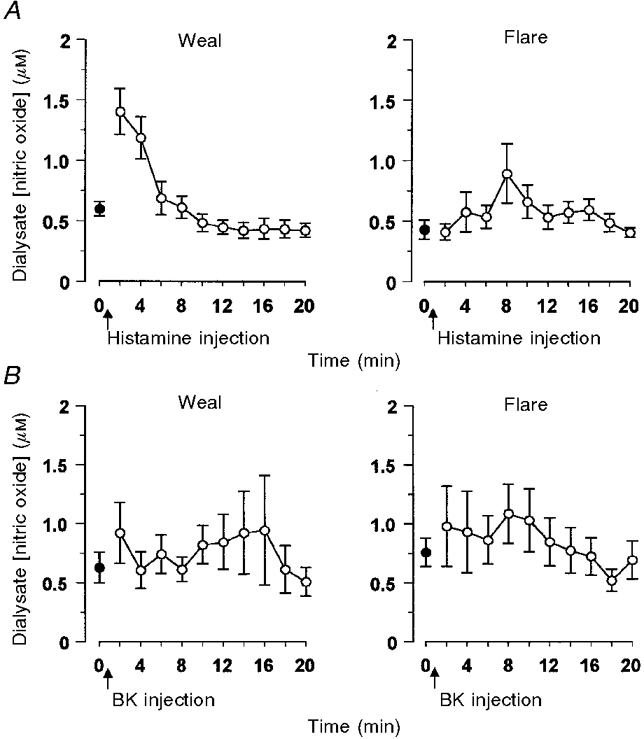

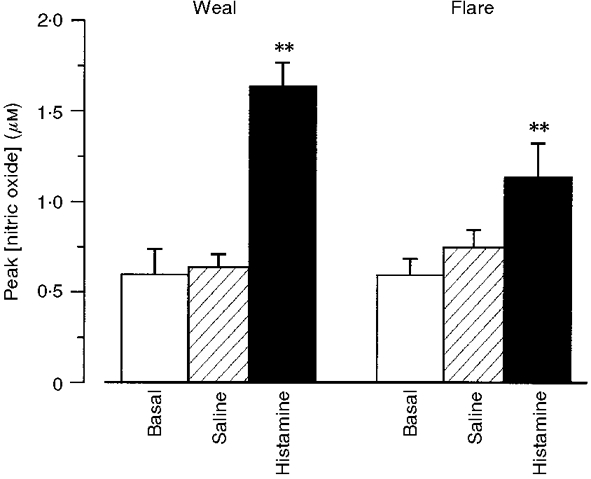

Intradermal injection of histamine caused a short-lived weal and flare response. Vasodilatation and oedema within the weal at the site of injection were detectable within 2 min using scanning LDI, whilst the flare area reached a maximum (25 ± 2 cm2) in 8-10 min. In all 9 subjects, transient increases in NO concentrations were seen in dialysate collected from both the weal and the flare areas. Within the weal, the NO concentration in the dialysate more than doubled within 2 min of histamine injection, returning towards baseline values by 10 min (Fig. 3A). In the flare area, the increase in NO was more variable, the peak at 6-8 min after histamine injection coincided with the visible flare front crossing the dialysis probe (Fig. 3A). Maximum dialysate NO concentration in both the weal (1·68 ± 0·16 μM) and the flare (1·19 ± 0·26 μM) were significantly greater than those following intradermal injection of vehicle (0·66 ± 0·09 μM, P < 0·001 and P < 0·01, respectively; Fig. 4). The injection of vehicle caused a small (< 0·5 cm2), but not sustained, increase in vascular flux at the site of injection.

Figure 3. NO release during the dermal vascular response to histamine or bradykinin.

NO concentration in dialysate from Ringer solution-perfused probes inserted into the volar surface of the forearm of healthy volunteers. Agonists were injected close to 1 fibre, such that the weal developed over this fibre and the flare over a second inserted at a distance of 20 mm from the first. Dialysate samples (2 min, 10 μl) were collected before (•) and after (^) the intradermal injection of (A) histamine (15 μl of 1 μM) or (B) bradykinin (15 μl of 1 μM). All data represent the means ±s.e.m. from 9 subjects.

Figure 4. Peak NO release in response to intradermal histamine or vehicle control.

Maximum values of dialysate NO concentration measured before (5) and after the injection of either histamine (15 μl of 1 μM) (▪) or vehicle control ( ). Dialysate was collected from both the weal and flare areas of the histamine response. Maximum values in the weal occurred 2-4 min (P < 0·001) after provocation with histamine and that in the flare 6-8 min (P < 0·01). All columns represent the means +s.e.m. from 9 subjects.

). Dialysate was collected from both the weal and flare areas of the histamine response. Maximum values in the weal occurred 2-4 min (P < 0·001) after provocation with histamine and that in the flare 6-8 min (P < 0·01). All columns represent the means +s.e.m. from 9 subjects.

Intradermal injection of bradykinin also caused a weal and flare response similar to that of histamine in size (12 ± 3 cm2, n= 9) and duration. However, comparison with the histamine response showed the bradykinin response to be somewhat different, with the area of bradykinin-induced flare relatively smaller than that of the weal (Clough et al. 1998a). Changes in dialysate NO concentration following intradermal injection of bradykinin were very variable, showing an increase in some subjects but not in others. Mean values of dialysate NO, calculated from measurements on 9 subjects, were not significantly different from baseline at any time in either the weal or the flare (Fig. 3B).

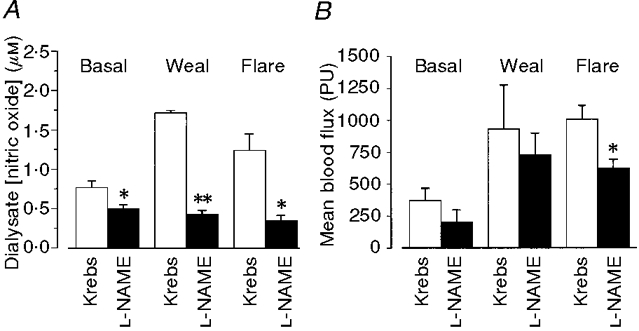

Effects of inhibition of NO synthesis by L-NAME

Addition of L-NAME to the probe perfusate caused a fall in both the concentration of NO in dialysate from resting skin and in dermal blood flux. L-NAME also inhibited the transient increase in NO measured in both the weal and the flare response to intradermal histamine (Fig. 5). In five subjects, the fall in basal NO (36 ± 12 %) and in resting blood flux (41 ± 10 %) were comparable (Fig. 6). Maximum concentrations of dialysate NO fell by up to 74 ± 6 % in the weal (P < 0·007) and 69 ± 8 % in the flare (P < 0·05) (Fig. 6A). The effect of L-NAME on the increased blood flow within the weal and flare was less clear (Fig. 6B). In the flare, a visible area of pallor was seen extending approximately 1-2 mm either side of the L-NAME perfused probe (Fig. 1). Mean blood flux within an area 20 mm × 4 mm above the probe was significantly lower than that in the same area immediately adjacent to Ringer solution-perfused probes (Fig. 6B). The percentage reduction by L-NAME of blood flux within the flare (37 ± 5 %) was similar to its effects on resting blood flow in unprovoked skin. The effect of L-NAME on vasodilatation within the weal was less easy to assess and did not reach significance in this study. This is possibly due to local tissue swelling which limits the accuracy of assessment of blood flow using scanning LDI.

Figure 5. Time course of the inhibition of histamine induced NO release by L-NAME.

Data obtained from one subject from two pairs of dialysis probes inserted into the volar surface of one forearm (see Methods). Probes were perfused with either Ringer's solution (^) or Ringer's solution containing L-NAME (5 mM) (•) for 30 min prior to the injection of histamine (15 μl of 1 μM) close to one probe of each pair, such that the weal developed over one probe and the flare over the second. Dialysate was collected at 2 min intervals.

Figure 6. Effects of L-NAME on dialysate NO concentration and dermal vascular perfusion.

A, L-NAME (5 mM) added to the microdialysis probe perfusate resulted in a fall in basal levels of NO (P < 0·03) (10 probes, 5 subjects). It reduced peak dialysate NO concentration following intradermal injection of histamine (15 μl of 1 μM) in both the weal (P < 0·007) and the flare response (P < 0·05). B, mean blood flux (in Moor LDI perfusion units, PU) measured in the region of the probe (see Fig. 1) was reduced by L-NAME in both resting skin (41 ± 10 %) and within the weal (17 ± 12 %) and flare (37 ± 5 %) response to histamine. The reduction only reached significance in the flare (P < 0·01). All columns represent means +s.e.m. from 5 subjects.

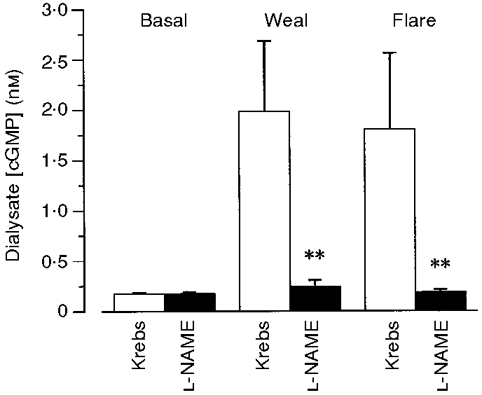

Dialysis of tissue cGMP

The initial concentration of cGMP in dialysis fluid from nine probes in seven subjects was 0·18 ± 0·01 nM. Continued probe perfusion and dialysis resulted in a fall in dialysate cGMP. The fall in cGMP concentration over 30 min of perfusion (30 %) was less marked than was seen with NO (60 %). However, as with NO measurement, histamine-induced changes in dialysate cGMP concentration were calculated from a baseline value measured in the dialysate sample collected immediately prior to dermal provocation. Following intradermal injection of histamine, dialysate cGMP concentration increased more than eightfold in both the weal and flare response. The increases were very variable but in all subjects were significantly greater than baseline (Fig. 7). In the weal, cGMP concentration rose within 2-6 min of intradermal injection to a maximum of 1·98 ± 0·70 nM (range 0·61-2·88 nM, 7 subjects). It remained elevated for up to 10 min before returning towards baseline. In the flare, dialysate cGMP increased to a maximum of 1·81 ± 0·76 nM (range 0·3-2·6 nM, P < 0·001). It remained elevated for up to 20 min.

Figure 7. Effect of L-NAME on dialysate cGMP concentration following intradermal histamine.

Dialysate cGMP concentration before and after the intradermal injection of histamine (15 μl of 1 μM) in the presence and absence of L-NAME (5 mM) added to the probe perfusate. The mean basal level of cGMP in the absence of L-NAME (0·18 ± 0·01 nM, 9 probes, 7 subjects) was not significantly different from that in its presence (0·17 ± 0·02 nM, 11 probes, 7 subjects). Addition of L-NAME to the perfusate significantly reduced the histamine-induced increase in cGMP concentration in both the weal and flare response (**P < 0·001) measured in adjacent sites on the forearms of 8 subjects.

Addition of L-NAME to the probe perfusate, caused little change in basal levels of cGMP in the dialysate (0·17 ± 0·02 nM, 11 lines, 7 subjects). It did however, inhibit the increase in dialysate cGMP measured following the intradermal injection of histamine injection. Maximum values in the weal and flare response in the presence of L-NAME were 0·24 ± 0·07 and 0·19 ± 0·03 nM, respectively (Fig. 7).

DISCUSSION

In this study it has been demonstrated that it is possible to measure NO release in human skin in vivo. The data provide definitive evidence that NO levels increase following intradermal provocation with histamine, used as a model of acute dermal inflammation, and that the generation of NO is accompanied by an increase in extracellular levels of cGMP within the vasodilator response. It was not possible to measure a significant release of NO following intradermal injection of bradykinin which also causes an acute inflammatory response in skin. Continuous delivery of the NOS inhibitor L-NAME, to the cutaneous tissue space by microdialysis reduced tissue NO and increased microvascular tone in resting skin. It also inhibited the increased NO and cGMP release and subsequent vasodilatation of the histamine-induced weal and flare. While these observations offer further evidence that, in human skin, NO plays an important role in both maintaining resting vascular tone and modulating the vasodilator response to histamine, they are also indicative of the involvement of mediators other than NO in the regulation of microvascular tone in the skin.

Assay of NO

As NO is rapidly oxidized to nitrite and nitrate in aqueous biological solutions, quantitative assay of these oxidative products of NO has been used extensively as an indirect measure of endogenous production of NO. In this study small, time-dependent changes in tissue levels of NO and its oxidative products have been assayed by electrochemical detection, using a 200 μm diameter amperometric NO sensor. The technique was adapted to assay 5 μl volumes of microdialysate, giving highly reproducible measurements of total nitrite (± 5 %) in both in vitro and in vivo samples. This method, which takes only 5-10 s to measure the concentration of NO generated by the reduction of nitrite in the sample, has been used previously to measure the time course of the release of NO into the bathing medium of cultured human umbilical vein endothelium, rat aortic endothelium and isolated blood vessels (Tsukahara et al. 1993; Guo et al. 1996). The present results confirm that this technique can also be used to assay NO in tissue fluid collected by dialysis. Assay of NO in dialysate has several additional advantages. First, because of the probe characteristics, the oxidative products of NO, once dialysed, are protected from degradation by large molecules such as enzymes and proteins which are excluded from the dialysate by the probe membrane. Second, as the proportion of nitrate relative to nitrite in dialysate is small, it is likely that the assay measures ongoing NO production within the tissue rather than accumulation of NO converted to nitrate as the final oxidative step. Finally, because of the high efficiency of dialysis of nitrite, the concentration of NO in dialysate reflects dynamic changes in tissue NO and represents a significant fraction of the NO/nitrite available for dialysis within the tissue space allowing time-dependent changes in NO to be measured.

Dialysis of endogenous NO

The initial concentration of NO measured in dialysate from human skin is similar to that measured in mouse skin using a similar microdialysis technique (Andoh & Kuraishi, 1997). It is present in quantities which have been shown to be sufficient to activate guanylate cyclase in vitro, to cause smooth muscle relaxation (Trottier et al. 1998). However, the source of the dialysable NO/nitrite in the tissue space remains undefined. Whilst it most probably originates from the endothelium of the upper dermal vascular plexus close to which the probes are implanted, there are other potential cellular sources of NO in the skin. These include keratinocytes, melanocytes, Langerhans' cells, fibroblasts (Bruch-Gerharz et al. 1998) and nerves (Iversen et al. 1997). The contribution that these other cellular sources make to basal levels of NO in skin has yet to be fully explored.

The apparent fall in NO observed during continued perfusion and dialysis of the tissue space has not been reported previously. There are several possible explanations for this fall. Firstly, probe insertion and perfusion may lead to changes in microvascular blood flow or alterations in the interstitial environment resulting in a reduction of NO production and release. While insertion and perfusion of these fibres does cause some initial trauma, the associated hyperaemia has been shown to resolve fully within 2 h of probe insertion (Lindén et al. 1998). This was confirmed in the present study. Secondly, the dialysis characteristics of the probe membrane may alter with time and limit exchange. The probes used in this study were similar to those used in a number of laboratories. As no change in the filtration characteristics of these membranes has been reported previously in dialysis experiments lasting up to 12 h (Clough et al. 1998d) it is probable that the fall in dialysate NO is not a result of changes in the physical properties of the membrane. The most likely explanation for the fall in dialysate NO is that it results from dialysis itself depleting the interstitial space of NO/nitrite. A similar explanation has been proposed for protein measurements using larger pore plasmapheresis membranes (Schmelz et al. 1997).

Previous studies have shown that dialysis efficiency in vivo is very close to that measured in vitro if probe perfusion rate and dialysis length remain constant (Zhao et al. 1995). The dialysis efficiency of the membranes for nitrite-nitrate, measured in vitro, in this study was around 90 %. The tissue space surrounding the probe available for dialysis of NO has a volume of approximate 60 μl, assuming the probe to dialyse a cylinder of tissue of diameter 2 mm over its total effective dialysis length of 20 mm. As the diffusion of NO within tissues is very limited, (Vaughn et al. 1998) continued, rapid removal of NO/nitrite by dialysis from this small space may exceed its production and diffusion from the surrounding tissue. If NO production by the tissue is constant, the amount of NO/nitrite in the dialysate will fall. This argument is supported by the observation that dialysate NO returns towards its initial value when perfusion of the dialysis probe is stopped and then restarted. For larger molecules such as cGMP with a lower in vitro dialysis efficiency this appears to be less of a problem, the exponential fall in dialysate cGMP during continued dialysis being less marked. Although not possible in this study, microdialysis may be used in the future to estimate the rate of synthesis of endogenous mediators such as NO and cGMP in vivo and to assess enzyme activity from in vitro observations.

Dialysis of exogenous NO

Organic nitrates have been recognized as a therapeutic source of NO for a number of years (Feelisch et al. 1995). In this study they were used to provide an exogenous source of NO as a positive control to test our ability to dialyse NO/nitrite in the skin. The increase in dermal NO measured beneath the GTN patches confirms not only that changes in dermal NO/nitrite can be detected in the skin but also that endothelial cells do bioactivate organic nitrates, in vivo. That the level of nitrate in the dialysate samples was not significantly greater than in baseline samples lends weight to the argument of Feelisch et al. (1995) that the nitroso-vasodilator is fully activated during its passage through the skin. Imaging of the site of application of GTN also demonstrated that the NO generated was in sufficient quantities to increase local blood flow.

Agonist-induced responses

The increases in NO measured within both the weal and flare response to intradermal injection of histamine were of a similar magnitude and time course to those measured in vitro from human umbilical vein and rat aortic endothelial cells (Tsukahara et al. 1993; Guo et al. 1996) and in vivo in mouse skin (Andoh & Kuraishi, 1997) in response to a variety of agonists. In the latter study, provocation with bradykinin caused a dose-dependent increase in NO, which was inhibited by the NO synthase inhibitor L-NAME. Whilst similar results were obtained in human skin in response to histamine, the bradykinin-induced NO release that was measured was somewhat more variable and will require further investigation. It seems likely however, that in human skin endothelial derived dilator factors other than NO may be involved in the vascular response to bradykinin.

To explore the relationship between NO production and local vasodilatation, scanning laser Doppler imaging of blood flux was combined with microdialysis. In a previous study Clough et al. (1998a) showed an increase in vascular flux in the area of the weal within 30 s of histamine or bradykinin injection. Changes in the region of the flare occurred more slowly but there was always a measurable increase in blood flux within 4 min. The steady-state changes induced by the agonists were similar in both the present and previous study. In the weal area, both NO and cGMP concentrations were maximal in the first dialysate sample collected after provocation. This is consistent with an agonist-induced increase in NO having a direct effect on guanylate cyclase to stimulate cGMP production and thence vasorelaxation. In the flare, where vasodilatation may be mediated by NO derived from the neurogenic activation of eNOS (Bull et al. 1996), there was also a close relationship between NO and cGMP release and the development of the vascular response. That the increases in dialysate NO and cGMP in both the weal and flare were abrogated by the addition of L-NAME to the probe perfusate is consistent with the responses being mediated via the NO-cGMP pathway.

Addition of L-NAME to the dialysis fluid also caused a reduction in resting tissue NO and blood flow, confirming a role for NO in the regulation of normal vascular tone in human skin. The inhibition of NO synthesis by L-NAME was rapid, dialysate NO falling significantly within 30 min. The time course of the reduction in blood flux was similar and consistent with that reported by (Goldsmith et al. 1996) who demonstrated a reduction in local blood flux of up to 60 %, 40 min after intradermal injection of L-NAME. In these experiments blood flux was determined using single point laser Doppler fluximetry at the injection site only. In the present experiments, to increase delivery of L-NAME to the tissue via the dialysis probe, the concentration of L-NAME used was much higher than that used by Goldsmith et al. (1996). Despite this, the area over which a change in blood flow was visible extended only 1-2 mm either side of the probe, further indicating that diffusion within the dermal interstitial space is limited.

Conclusion

This study has focused upon the release of NO in healthy human skin and has demonstrated a close association between tissue levels of NO and cGMP and local blood flow. The source of that NO remains equivocal and in the skin may be derived from a number of cellular sources other than endothelium. Further characterization of these sources, which include keratinocytes, melanocytes, Langerhans' cells and fibroblasts, will be important to our future understanding of the modulation of the dermal vasculature by NO in both healthy skin and in inflammatory, hyperproliferative and autoimmune skin disease in which many of these cells play an important part (Rowe et al. 1997).

Acknowledgments

Miss Amanda Bennett is acknowledged for her excellent technical help in the analysis of the dialysate samples. The author would like to thank Professors M. K. Church and P. S. Friedmann for their generous help both during the project and in the preparation of this manuscript. G. F. C. is supported by The Wellcome Trust grant no. 050164/Z/97.

References

- Anderson C, Andersson T, Wårdell K. Changes in skin circulation after insertion of a microdialysis probe visualized by laser Doppler perfusion imaging. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1994;102:807–811. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12378630. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12378630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andoh T, Kuraishi Y. Quantitative determination of endogenous nitric oxide in the mouse skin in vivo by microdialysis. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;332:279–282. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01114-x. 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01114-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benrath J, Eschenfelder C, Zimmerman M, Gillardon F. Calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P and nitric oxide are involved in cutaneous inflammation following ultraviolet irradiation. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;293:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0926-6917(95)90022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bito L, Dawson H, Levin E, Murray M, Snider N. The concentrations of free amino acids and other electrolytes in cerebral spinal fluid, in vivo dialysate of brain, and blood plasma of the dog. Journal of Neurological Chemistry. 1966;13:1057–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1966.tb04265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruch-Gerharz D, Ruzicka T, Kolb-Bachofen V. Nitric oxide in human skin: current status and future prospects. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1998;110:1–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull HA, Hothersall J, Chowdhury N, Cohen J, Dowd P. Neuropeptides induce release of nitric oxide from human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1996;106:655–660. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12345471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunker CB, Goldsmith PC, Leslie TA, Hayes N, Foreman JC, Dowd PM. Calcitonin-gene-related peptide, endothelin-1, the cutaneous microvasculature and Raynaud's-phenomenon. British Journal of Dermatology. 1996;134:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough GF, Bennett AR, Church MK. Effects of H-1 antagonists on the cutaneous vascular response to histamine and bradykinin: a study using scanning laser Doppler imaging. British Journal of Dermatology. 1998a;138:806–814. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough GF, Bennett AR, Church MK. Measurement of nitric oxide concentration in human skin in vivo using dermal microdialysis. Experimental Physiology. 1998b;83:431–434. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1998.sp004126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough GF, Bennett AR, Church MK. Relationship between nitric oxide, cyclic GMP and vasodilatation in human skin, in vivo. The Journal of Physiology. 1998c;515.P:153–154. P. [Google Scholar]

- Clough GF, Jeffery S, Griffiths T, Church MK. Mediator release during the allergic response in human skin in vivo, measured using dermal microdialysis. The Journal of Physiology. 1998d;515.P:148. P. [Google Scholar]

- Coffman JD. Effects of endothelium-derived nitric oxide on skin and digital blood flow in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:H2087–2090. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.6.H2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz NM, Rivera JM, Warner DO, Joyner MJ. Is nitric oxide involved in cutaneous vasodilatation during body heating in humans? Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994;76:2047–2053. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.5.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feelisch M, Brands F, Kelm M. Human endothelial cells bioactivate organic nitrates to nitric oxide: implications for the reinforcement of endothelial defense mechanisms. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;25:737–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1995.tb01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;288:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith P, Leslie T, Hayes NA. Inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase in human skin. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1996;106:113–118. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12328204. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12328204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J-P, Murhara T, Buerke M, Scalia R, Lefer AM. Direct measurement of nitric oxide release from vascular endothelial cells. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1996;81:774–779. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S, Brain S. Nitric oxide-dependent release of vasodilator quantities of calcitonin gene-related peptide from capsaicin-sensitive nerves in rabbit skin. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1994;111:425–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen HH, Celsing F, Leone AM, Gustafsson LE, Wiklund NP. Nerve induced release of nitric oxide in the rabbit gastrointestinal tract as measured by in vivo microdialysis. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;120:702–706. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubes P. Nitric oxide affects microvascular permeability in the intact and inflamed vasculature. Microcirculation. 1995;2:235–244. doi: 10.3109/10739689509146769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindén M, Wårdell K, Andersson T, Anderson C. High resolution laser Doppler perfusion imaging for the investigation of blood circulatory changes after microdialysis probe insertion. Skin Research and Technology. 1998;3:227–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.1997.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnroth P, Jansson PA, Smith U. A microdialysis method allowing characterization of intercellular water space in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:E228–231. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1987.253.2.E228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S, Higgs A. The L-arginine: nitric oxide pathway. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noon JP, Haynes WG, Webb DJ, Shore AC. Local inhibition of nitric oxide generation in man reduces blood flow in finger pulp but not in hand dorsum skin. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;490:501–508. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta K, Araki N, Shibata M, Hamada J, Komatsumoto S, Shimazu K, Fukuuchi Y. A novel in vivo assay system for consecutive measurement of brain nitric oxide production with the microdialysis technique. Neuroscience Letters. 1994;176:165–168. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90073-6. 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RM J, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen LJ, Church MK, Skov PS. Histamine is released in the weal but not the flare following challenge of human skin in vivo: A microdialysis study. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 1997;27:284–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1997.d01-502.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1997.d01-502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen LJ, Mosbech H, Skov PS. Allergen-induced histamine-release in intact human skin in vivo assessed by skin microdialysis technique - characterization of factors influencing histamine releasability. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1996;97:672–679. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)70313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen LJ, Winge K, Brodin E, Skov PS. No release of histamine and substance P in capsaicin-induced neurogenic inflammation in intact skin in vivo: a microdialysis study. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 1997;27:957–965. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1997.950911.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe A, Farrell AM, Bunker CB. Constitutive endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthase in inflammatory dermatoses. British Journal of Dermatology. 1997;136:18–23. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.d01-1136.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz M, Luz O, Averbeck B, Bickel A. Plasma extravasation and neuropeptide release in human skin as measured by intradermal microdialysis. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;230:117–120. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00494-1. 10.1016/S0304-3940(97)00494-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trottier G, Triggle CR, O'Neill SK, Loutzenhiser R. Cyclic GMP-dependent and cyclic GMP-independent actions of nitric oxide on the renal afferent arteriole. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;125:563–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara H, Gordienko DV, Goligorsky MS. Continuous monitoring of nitric oxide release from human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochemistry and Biophysics Research Communications. 1993;193:722–729. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1685. 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn MW, Kuo L, Liao JC. Effective diffusion distance of nitric oxide in the microcirculation. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:H1705–1714. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.5.H1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JB. Nitric oxide and human skin blood flow responses to acetylcholine and ultraviolet light. FASEB Journal. 1994a;8:247–251. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.7509761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JB, Loi JB, Wilson AJ. PGD2 is an intermediate in agonist-stimulated nitric oxide release in rabbit skin microcirculation. American Journal of Physiology. 1994b;266:H1846–1853. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.5.H1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller R. Nitric oxide and the skin. British Journal of Dermatology. 1997;137:665–672. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.19332063.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Liang X, Lunte CE. Comparison of recovery and delivery in vitro for calibration of microdialysis probes. Analytica Chimica Acta. 1995;316:403–410. 10.1016/0003-2670(95)00379-E. [Google Scholar]