Abstract

GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic innervation of oxytocin neurones in the supraoptic nucleus (SON) was analysed in adult female rats going through their first reproductive cycle by recording the spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) at six stages of female reproduction.

During pregnancy we observed a reduction in the interval between monoquantal sIPSCs. The synaptic current amplitude, current decay and neurosteroid sensitivity of postsynaptic GABAA receptors observed at this stage were not distinguishable from those measured in virgin stage SON.

Upon parturition an increase in monoquantal synaptic current decay occurred, whereas potentiation by the progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone (3α-OH-DHP) was suppressed.

Throughout a substantial part of the lactation period the decay of synaptic currents remained attenuated, whilst the potentiation by 3α-OH-DHP remained suppressed.

Several weeks after the end of lactation sIPSC intervals, their current decay velocity as well as the potentiation by 3α-OH-DHP were restored to pre-pregnancy levels, which is indicative of the cyclical nature of synaptic plasticity in the adult SON.

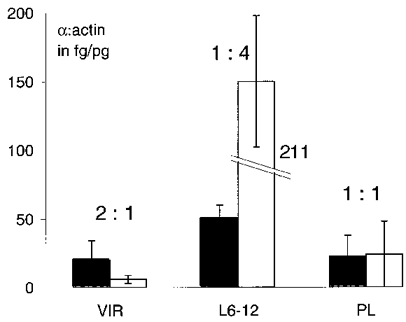

Competitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis showed that virgin animals expressed α1 and α2 GABAA receptor subunit mRNA at a relative ratio of 2 : 1 compared with β-actin. After pregnancy both α1 and α2 subunit mRNA levels were transiently increased, although at a relative ratio of 1 : 4, in line with the hypothesis that α2 plays a large role in postsynaptic receptor functioning. During post-lactation both α subunits were downregulated.

We propose that synaptic remodelling in the SON during pregnancy includes changes in the putative number of GABA release sites per neurone. At parturition, and during the two consecutive weeks of lactation, a subtype of postsynaptic GABAA receptors was observed, distinct from the one being expressed before and during pregnancy. Synaptic current densities, calculated in order to compare the impact of synaptic inhibition, showed that, in particular, the differences in 3α-OH-DHP potentiation of these two distinct GABAA receptor subtypes produce robust shifts in the impact of synaptic inhibition of oxytocin neurones at the different stages of female reproduction.

Magnocellular neurones in the supraoptic nuclei (SON) of the hypothalamus (Rhodes et al. 1981) in female mammalian animals secrete systemic oxytocin during parturition and lactation. One of the key players in the regulation of these cells is their inhibitory input (Van de Pol, 1985), mediated via postsynaptic GABAA receptors. This is evident from whole animal analyses (Voisin et al. 1995), in situ patch-clamp recordings (Brussaard et al. 1996, 1997) and immunohistochemical findings combined with in situ hybridization studies (Fenelon et al. 1995; Fenelon & Herbison, 1995, 1996).

Several phenomena of neuronal plasticity occur in the SON during each cycle of reproductive activity in female rats. Structural changes in lactating female rats include: (a) complex alterations in neurone-glia interactions (Hatton, 1990, 1997; Theodosis & MacVicar, 1996), (b) an increase in the number of GABA release sites (Gies & Theodosis, 1994), (c) the appearance of multiple synapses (Gies & Theodosis, 1994), (d) hypertrophy of the somata and dendrites of oxytocin neurones (Theodosis & Poulain, 1993) and (e) a shift in the cellular mRNA content in oxytocin neurones, encoding the α1 subunit of the GABAA receptor, from higher than normal during late pregnancy to a lower level just before parturition (Fenelon & Herbison, 1996). Recently it was reported that the latter alteration in α1 subunit expression relative to α2 affects the ion channel gating of the GABAA receptor expressed by the dorsomedial SON neurones, and that this change in α subunit expression correlated with a change in GABAA receptor potentiation by 3α-OH-DHP (Brussaard et al. 1997).

The physiological consequences of changes in GABAergic innervation of oxytocin neurones in the female SON during the reproductive cycle are described in this paper. We applied the in situ patch-clamp technique to dorsomedial SONs of female rats going through their first reproductive cycle and measured the properties and neurosteroid regulation of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) at all reproductive stages, including virginity, pregnancy day 20, parturition day 1, lactation days 6, 10-12 and 17, and after a post-lactation period of 6 weeks.

METHODS

Hypothalamic slices and patch-clamp procedure

Female adult Wistar rats were used in this study: all rats were used either before, during or after their first reproductive cycle. Reproductive stages recorded from included virginity (VIR), late pregnancy (day 20, P20), parturition (2-24 h after parturition is referred to as post-parturition day 1, PPD1), several stages of lactation (days 6, 10-12 and 17, or L6, L10-12 and L17) and a post-lactation stage (6 weeks, PL). Rats were killed by decapitation using a guillotine, without the use of anaesthetics (approval of the ethical committee concerning animal experiments was obtained). Coronal hypothalamic slices (400 μm thick) were prepared as previously described (Brussaard et al. 1996, 1997). We always used the midportion of the SON (around 800 μm rostral of the most anterior portion of the SONs) and only recorded from dorsomedial SON neurones in this section. Previously we have shown that around 70 % of these neurones are sensitive to autoregulation by oxytocin (Brussaard et al. 1996). Whole-cell recordings from the SON were performed under visual control using infrared video microscopy (Stuart et al. 1993; see also Brussaard et al. 1996).

In situ patch-clamp recordings

Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) was prepared in sterile water (Baxter, Utrecht, The Netherlands) containing (mM): 125 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 3 KCl, 1·2 NaH2PO4.H2O, 2·4 CaCl2.2H2O, 1·3 MgSO4.7H2O, and 10 D-glucose (304 mosmol, carboxygenated in 5 % CO2 and 95 % O2, pH 7·4). For experiments carried out in nominally zero extracellular Ca2+, the bath solution contained a modified, so-called Ca2+-free ACSF containing (mM): 125 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 3 KCl, 1·2 NaH2PO4.H2O, 1·3 MgSO4.7H2O, 2·4 MgCl2 and 10 D-glucose. Pipette solution was prepared weekly and contained (mM): 141 CsCl, 10 Hepes, 2 MgATP, 0·1 GTP (acid free) and 1 EGTA, adjusted to pH 7·2 using CsOH (296 mosmol). Whole-cell recordings were made at 20-22°C using 2-3 MΩ patch electrodes. Cell-attached gigaohm sealing, switching to the whole-cell mode and selecting recordings were performed as described in detail by Brussaard et al. (1996, 1997). All recordings were undertaken at a holding potential of -70 mV. Whole-cell recordings with an uncompensated series resistance (Rs) > 12 MΩ were rejected and in accepted recordings, Rs was usually compensated by 80 % and not allowed to change more than 20 % of the initial value up to the end of the recordings. In recordings selected according to these criteria, we observed 10-90 % base to peak rise times of the sIPSCs that averaged at < 1 ± 0·5 ms (checked in every recording referred to in this study).

Both glutamatergic as well as GABAergic synaptic currents were observed in recordings made within 2 h after preparation of the slices. For the experiments described here, the GABAergic synaptic currents were pharmacologically isolated using 6, 7-nitro-quinoxaline-2, 3-dione (DNQX; 20 μM) and D-aminophosphonovalerate (AP5; 20 μM) to block glutamatergic synaptic currents (from RBI, Natick, MA, USA; both at 20 μM).

Neurosteroids and microperfusion

Allopregnanolone (5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one (or 3α-OH-DHP), obtained from RBI, dissolved in DMSO at 10 mM and diluted in ACSF) was microperfused, using a so-called Y-tube (Brussaard et al. 1996) which allows for long duration applications of substances at the site of slice recording under visual control (coloured with Amaranth, 0·025 %). Control applications of carrier solution (i.e. 0·1 % DMSO) had no effect on the sIPSCs (n= 8; not shown). The effect of two concentrations of 3α-OH-DHP was studied by constant perfusion of 1 and 10 μM, respectively. Extensive rinsing with normal ACSF (30-45 min) at the start of each experiment was performed to wash out endogenous 3α-OH-DHP (that may be present due to pregnancy; Corpéchot et al. 1993). The onset of the effect of 3α-OH-DHP was slow: we never observed acute effects of the allopregnanolone application. The potentiating effect on the decay of sIPSCs was only noticeable after 2-4 min of application. Even after 4 min of allopregnanolone application, the effect was still developing in a progressive manner, indicating that, due to the lipophilicity of the compound, a substantial decrease in the concentration of 3α-OH-DHP will occur in deeper layers under the slice surface. Thus the experimentally applied concentrations may not reflect accurately the concentration of 3α-OH-DHP at the site of action in the slice. For clarity we refer to in vitro studies on single cells, which showed that a maximal effect of 3α-OH-DHP on GABAA receptors occurs at around 100 nM (Twyman & MacDonald, 1992), which is similar to the endogenous 3α-OH-DHP concentration reported in hypothalamus during pregnancy (Corpéchot et al. 1993). The effect of this neurosteroid on sIPSCs was only slowly reversible (> 30 min of washing was required).

Digital detection of IPSCs

The recordings were stored on digital audio recording tapes (at 5 kHz and amplified five times using an Axopatch-200A amplifier) and analysed off-line, after 1 kHz filtering using a Bessel filter and AD conversion at 5-10 kHz sampling rate using a CED 1400 digitizer. For the analysis of spontaneous synaptic currents, the Strathclyde Computer Disk Recorder (CDR) software of John Dempster (University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK) was used. To this end the entire recording was first digitized (up to 10 min of recording). Next, synaptic events were detected in the CDR software package using a so-called ‘software trigger’. We have previously analysed in detail whether sIPSC amplitude or interval measurements obtained, using this method, were dependent on the signal-to-noise ratio of the recordings and found that the smallest events were well above our detection threshold using the CDR software (Brussaard et al. 1996, 1997).

Analysis of average sIPSC amplitude and decay

After detection of the synaptic events, amplitude and decay time constant histograms (using a minimum of 250 events per histogram) were obtained. To this end > 250 individual sIPSCs in each experiment were analysed. The decay of sIPSCs was fitted with both mono- and bi-exponential curves (with and without non-decaying components). Adequate fits were obtained using monoexponential curves, which were forced to 0 nA. IPSC amplitude and decay time constant distributions were fitted with a single lognormal function:

| (1) |

in which Y is the number of events, A is the relative area under the curve, X is the measured amplitude (or decay time constant, respectively), and μ is the mean and σ the standard deviation of the underlying normal distribution. The mean (μ‘) and standard deviation (σ’) of the lognormal distribution were calculated from this by using:

| (2) |

| (3) |

The sIPSC intervals were analysed by fitting a single exponential curve to the linear sIPSC interval histogram (minimum of 250 events per histogram), which gave a single time constant that represents the mean of the distribution.

In the text and figures, unless specified otherwise, means and standard deviations (s.d.) are given. Numbers of experiments are given in the text.

Current density of synaptic inhibition

To determine the impact of the synaptic inhibition mediated by GABAA receptors over longer periods, we derived the average integral of consecutive synaptic currents (minimum of 250 sIPSCs) in each experiment (and per experimental condition). We used an analytical method to describe the integral of the average sIPSC per experiment. The decay of sIPSCs was well described by a monoexponential function:

| (4) |

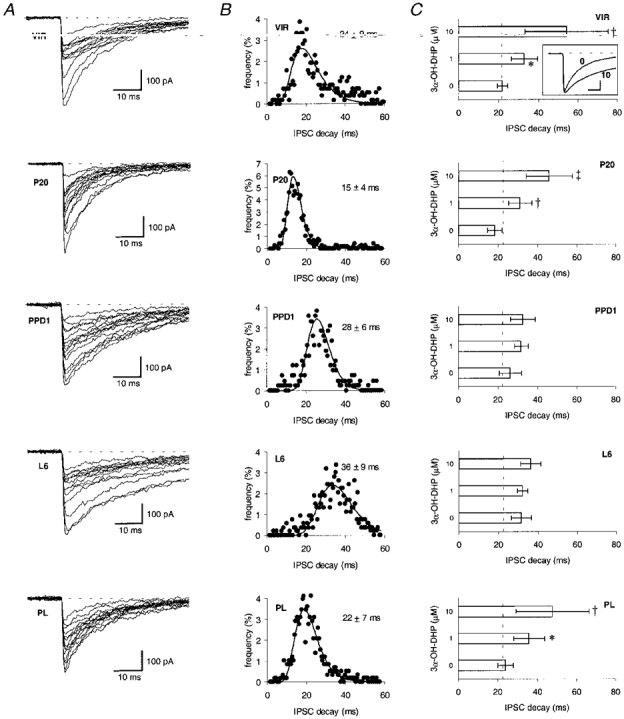

where I (t) is the amplitude of the current at time point t, Imax is the amplitude of the sIPSC at its maximum and τ is the time constant. The integral of the sIPSC is given by:

|

(5) |

For Imax we used the μ value of the lognormal function fitted to sIPSC amplitude histograms, and for τ we used the μ value of the sIPSC decay time constant distribution. The outcome of eqn (5) was divided by the average interval of occurrence of sIPSCs to quantify the overall impact of synaptic inhibition in each reproductive stage, as shown in Fig. 5 (p C s−1). To calculate the current density per cell surface area, the outcome of this analysis was corrected for changes in cell capacity (outcome in pC s−1 pF−1).

Figure 5. Neurosteroid effects dominate the impact of the synaptic inhibition of the dorsomedial SON neurones.

A, estimate of the relative cell size obtained by whole cell capacitance measurements during these recordings. B, synaptic current densities (pC s−1) of sIPSCs before and after application of 3α-OH-DHP (10 μM) at the stages indicated (see legend to Fig. 2). C, synaptic current densities (- and +3α-OH-DHP) plotted relative to the cell capacitance values (pC s−1 pF−1) of the same recordings as in B. Statistics: ANOVA followed by post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A: * and ‡ denote P < 0·05 and P < 0·001, respectively, compared with the VIR stage (control). B : † and ‡ denote P < 0·01 and P < 0·001, respectively, relative to the synaptic current density in the absence of 3α-OH-DHP under each condition; ³ P < 0·01 compared with the P20 in presence of 3α-OH-DHP. (Control bars in all parts of this figure are from n= 19, 21, 21, 5, 12, 5 and 6 different recordings, respectively; all levels in the presence of 3α-OH-DHP are from at least n= 5 different recordings.)

Competitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The levels of GABA α1 and α2 subunit-encoding mRNAs were determined relative to the β-actin mRNA content from rat SON by competitive PCR. SONs were dissected from virgins, lactating or post-lactating females and washed in RNAse-free phosphate-buffered serum. Each SON was homogenized in 150 μl lysis buffer (4 M guanidinium, 20 mM sodium acetate, pH 5·2, 0·1 mM dithiothreitol). After homogenization the lysates were supplemented with 0·5 %N-sarkosyl and incubated for 10 min on ice. After the addition of 20 ng of tRNA, samples were phenol-chloroform extracted, precipitated and treated with RQ1 DNAse (Promega). After a second extraction and precipitation, RNA was reverse transcribed in a 30 μl final volume by 300 U SuperScript (Gibco BRL) in the presence of 40 U RNasin (Promega), 0·5 μg random hexamers (Gibco BRL) and 0·5 mM of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were incubated at 75°C for 15 min to inactivate reverse transcriptase, and diluted ten times. Ten microlitres of the diluted cDNA were amplified in 35 cycles (94°C, 30 s; 50°C, 30 s; 72°C, 45 s) in 50 μl PCR reactions with 0·5 U Taq Polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim) in the presence of 1 μM of sense and antisense primers, 200 μM of each dNTP and 1·5 mM MgCl2. To compete with the natural cDNA templates in the amplification reaction, shorter cDNA constructs in a 1000-0 fg range for α1 or α2 and in a 100-0 pg range for actin were mixed with the samples before amplification. The PCR was carried out in the presence of radioactive deoxyATP. The amplified products were separated from each other and from the unincorporated radioactivity by electrophoresis. DNA bands, visualized with ethidium bromide, were excised and the incorporated radioactivity was quantified in a scintillation counter.

PCR primers

GABAAα1 sense, TGGCAAAAGCGTGGTTCC (sequence position: 1089); GABAAα1 antisense, AGAGGCAGTAAGGCAGAC (1500); GABAAα2 sense, TGGTTTATCGCTGTTTGTTA (886); GABAAα2 antisense, ATGTTTTCTGCCTGTATTTC (1486); β-actin sense, GGAAATCGTGCGTGACAT (618); β-actin antisense, GGAAGG-TGGACAGTGAGG (1040).

Deletion constructs used to compete with the cDNAs of native mRNAs

A 80-120 base pair long sequence was deleted from each cDNA (GABA α1: 1340-1420; GABA α2: 1130-1221; β-actin: 792-910) and the shortened cDNAs were ligated into PCR 2 vector.

RESULTS

Monoquantal sIPSCs of dorsomedial SON neurones

We aimed at recording so-called miniature or monoquantal spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs), which are not dependent on presynaptic sodium channel activity and/or Ca2+ influx (Mody et al. 1994). Each monoquantal sIPSC is believed to be the result of the release of a single vesicle of neurotransmitter, which transiently saturates the synaptic cleft. The intervals between monoquantal sIPSCs are determined by random vesicle fusions occurring at different synapses all impinging on the same cell.

The sIPSCs were recorded from the dorsomedial SON where the majority of magnocellular neurones are oxytocin containing (Rhodes et al. 1981). In the presence of DNQX and AP5, at a holding potential of -70 mV, the sIPSCs were detected as inward currents due to the symmetrical intra- and extracellular chloride concentration. The sIPSCs reversed to outward at potentials above 0 mV (Brussaard et al. 1996) and were completely blocked by bicuculline (20 μM, not shown, n= 15).

At 20-22°C the sIPSC amplitude was 290 ± 100 pA, the interval between sIPSCs was 880 ± 450 ms and the decay time constant of sIPSCs was 22 ± 3 ms (non-reproductive females, n= 31, 10-90 % rise time, < 1 ms). To test whether the sIPSCs were the result of monoquantal release of vesicles, we tested the effect of nominally zero extracellular Ca2+ and application of TTX (2 μM), as well as a combination of zero Ca2+ and TTX in three experimental groups of slices (VIR, P20 and L17). In the VIR group, none of these applications had a significant effect on either the sIPSC amplitude or interval (n > 4 for all types of application, n.s., paired t test). The same is true for the P20 experimental group of recordings (n > 4 for all applications, n.s., paired t test; for L17 data, see below). This is in line with previous reports (Brussaard et al. 1996, 1997). Therefore we conclude that so-called miniature sIPSCs were recorded, which were not dependent either on presynaptic electrical activity or on Ca2+ influx.

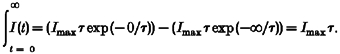

Number of GABAergic release sites

To test in what way previously reported changes in the number of GABAergic synapses (Theodosis & Poulain, 1993; Gies & Theodosis, 1994) may affect the fast synaptic inhibition of oxytocin neurones during a reproductive cycle, we compared the amplitude and intervals of sIPSCs in slices from P20 animals with those obtained in slices from the VIR group. If, at a particular stage, so-called ‘silent’ or novel synapses are being recruited, and one assumes that there is no change in the spontaneous release of GABAergic vesicles, then recordings of miniature or monosynaptic GABA currents at that stage are predicted to reveal an increase in the frequency at which miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents occur. Furthermore, recruitment of novel synapses would involve turnover and/or new insertion of postsynaptic receptors. Hence it is also important to determine whether changes occur in the amplitude of individual sIPSCs. Thus in individual experiments, stretches of consecutive recording including at least 250 sIPSCs (Fig. 1A) were analysed both with respect to the amplitudes of spontaneous events, which were lognormally distributed (Fig. 1B), and with respect to the intervals, which were fitted with a single exponential curve (Fig. 1C). It was observed that the interval - but not the amplitude - of sIPSCs was significantly changed between the two groups of recordings. This is exemplified in individual experiments (Fig. 1A-C) as well as in the averages of many recordings under normal conditions (Fig. 2A and B) and under experimental conditions that permit only monoquantal release of GABA (TTX and/or zero extracellular Ca2+; Fig. 2C). The average interval between sIPSCs in the VIR group was 877 ± 448 ms (n= 19) compared with 477 ± 175 ms in the P20 group (n= 21, 46 % reduction compared to the VIR stage, P < 0·01, Fig. 2A). The mean sIPSC amplitude in the VIR group was 288 ± 101 pA (n= 19) compared with 217 ± 68 pA in the P20 group (n= 21, Fig. 2B), which was not significantly different. The amplitudes and intervals of miniature sIPSCs recorded at both stages in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ and/or the presence of TTX, gave the same result: pregnancy had no significant effect on the amplitude, but did affect the interval between sIPSCs (Fig. 2C).

Figure 1. Pregnancy induces a decrease in the sIPSC interval.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recording of dorsomedial SON neurones before (VIR) and during pregnancy (P20) showing spontaneous IPSCs at a low and high frequency, respectively. A, representative traces at both stages; B, distributions of the sIPSC amplitudes of the same experiments as in A, with lognormal curves fitted to these scatterplots; C, exponentially distributed sIPSC intervals. The values given above the plots in B and C indicate the mean and standard deviation for each distribution.

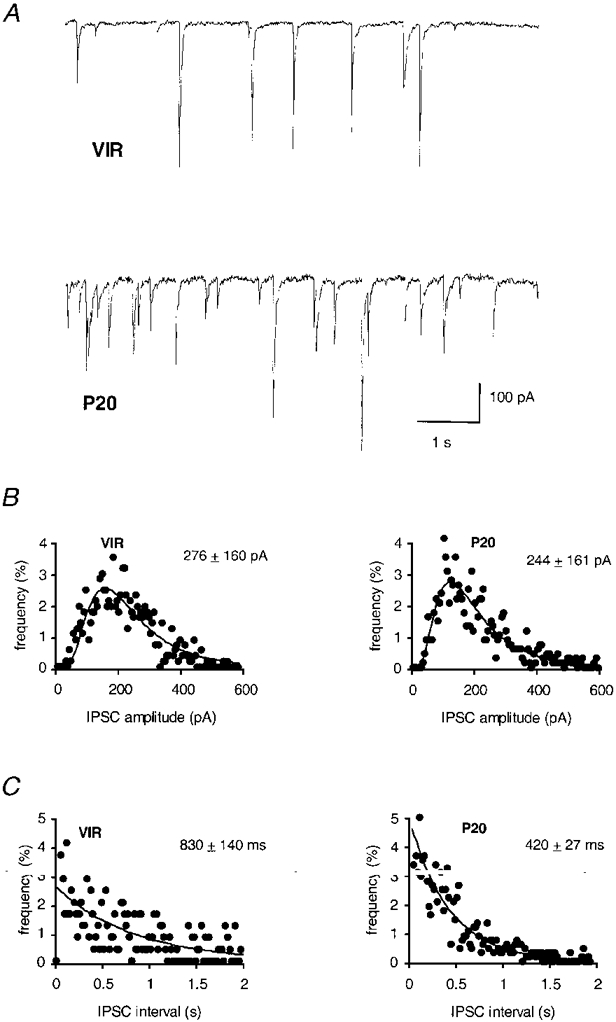

Figure 2. Neuronal plasticity in the SON affects sIPSC intervals and amplitudes at the different stages of female reproduction.

A, mean sIPSC interval; B, mean sIPSC amplitude at, respectively, the virgin stage (VIR, n= 19), pregnancy day 20 (P20, n= 21), post-parturition day 1 (PPD1, n= 21), lactation days 6, 10-12 and 17 (L6, L10-12 and L17, n= 5, 12 and 5, respectively) and a post-lactation stage (POST, n= 6). C, in the presence of zero extracellular Ca2+ and/or TTX, the sIPSC interval - but not the sIPSC amplitude - in late pregnant rats was significantly reduced compared with the virgin condition (P < 0·05, n > 4 for all tests). Statistics: * significantly different compared with the VIR group at P <= 0·01; † significantly different compared with the P20 group at P <= 0·05; ³ significantly different compared with L17 at P < 0·01. The interrupted lines indicate the VIR level of each histogram. Statistics were obtained using ANOVA followed by post hoc tests for multiple comparisons. D, application of zero extracellular Ca2+ and TTX during sIPSC recordings at L17 did not significantly affect the interval, nor the amplitude of the synaptic currents (n= 4).

At PPD1 the sIPSC interval was 468 ± 165 ms (Fig. 2A; n= 21; not significantly different from P20, but still different from VIR; P < 0·01). Also, at L6, the sIPSC intervals were still significantly reduced (P < 0·01, n= 5) compared with the VIR group, and thus similar to the P20 stage (Fig. 2A). Concomitant with the progress of lactation, however, the effect on the sIPSC interval gradually disappeared, being intermediate at L10-12 and L17 (n= 12 and n= 5, respectively) to the VIR and the P20 values (not significantly different from VIR or P20). Six weeks after the end of lactation, i.e. during post-lactation (PL, n= 6), the sIPSC interval was restored to the pre-pregnancy level (not significantly different from the VIR stage, but significantly longer than at P20, P < 0·05, Fig. 2A).

Thus during the first half of lactation (PPD1 and L6), the interval between sIPSCs remained reduced compared with virgins (VIR), a phenomenon that was already obvious at late pregnancy (P20). As indicated above, a reduction in the interval between monoquantal sIPSCs may be due to an increase in the total number of detectable GABA release sites per oxytocin neurone that has been reported previously (Gies & Theodosis, 1994). Alternatively, an unknown change in the probability of GABA vesicle release at individual synapses might be induced during pregnancy.

Changes in postsynaptic receptor density

As pointed out above, we hypothesized that during or after pregnancy, alterations in receptor density under individual synaptic boutons may occur. To test this hypothesis, we compared the amplitudes of miniature sIPSCs obtained at various stages of reproduction.

The average sIPSC amplitude at PPD1, L6 and L10-12 was not significantly different from the P20 level (Fig. 2B, n= 21, 5 and 12, respectively). However, at L10-12, the standard deviation of sIPSC amplitudes was significantly larger (P < 0·01, Fmax test) than at the L6 stage, indicating that both smaller and larger sIPSC amplitudes occur at this stage (Fig. 2B). At L17, significantly larger sIPSC amplitudes were observed, amounting to 570 ± 313 (n= 5, P < 0·01 compared with VIR, and P < 0·001 compared with P20, Fig. 2B). To test whether this increase in sIPSC amplitude was not due to presynaptic electrical activity at this stage, we co-applied TTX and zero extracellular Ca2+ in four different experiments at the L17 stage, but found no significant effect of these applications on either the sIPSC amplitude or their interval (Fig. 2D).

The effect on the average sIPSC amplitude at late lactation was restored after 6 weeks of post-lactation period (PL, n= 6, Fig. 2B), to a level no longer significantly different from the pre-pregnancy level.

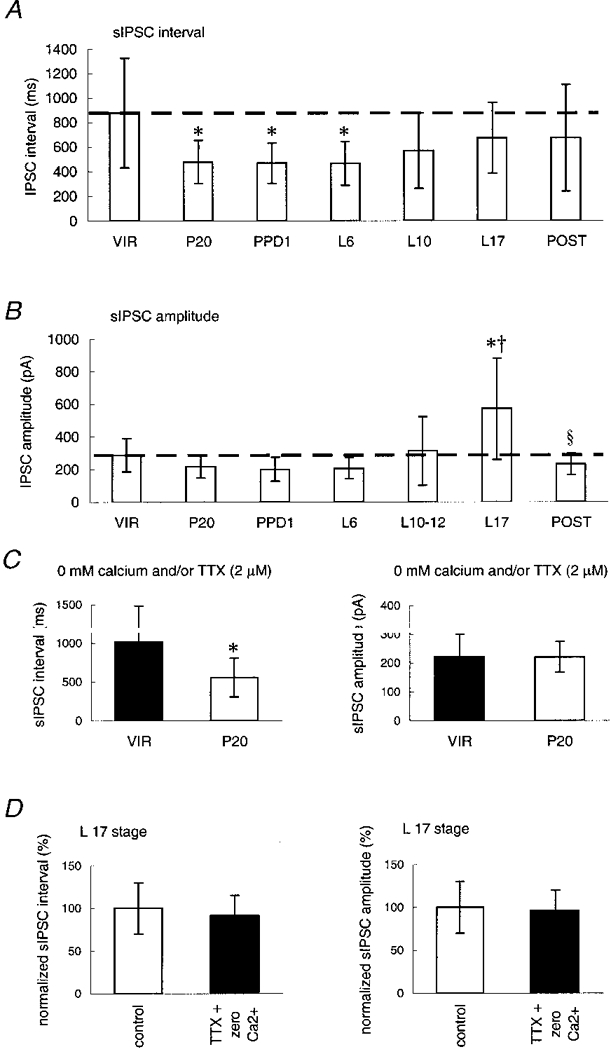

Functional expression of a novel subtype of GABAA receptors

We asked whether the postsynaptic GABAA receptors found at P20 are of a similar subtype to those expressed in the virgin (VIR) stage. To answer this question we analysed the synaptic current decay and neurosteroid potentiation in the P20 group compared with the VIR stage. This revealed that the sIPSC decay during pregnancy (P20), although in some experiments up to 20-40 % faster than the average in the VIR group (Fig. 3A and B), was not significantly altered overall (Fig. 3C; VIR: 22 ± 3 ms vs. P20: 18 ± 4 ms, n= 19 vs. 21, respectively). Moreover, both at the VIR stage and at P20, we observed a very similar, dose-dependent potentiation of sIPSC by 3α-OH-DHP, which was clearly visible as an attenuation of the time course of the decay of individual and averaged sIPSCs (see inset, Fig. 3C, n > 5 for all tests). We did not observe any effect of 3α-OH-DHP on the average sIPSC amplitude in either of the experiments performed (not shown, n > 5 for all tests), which is in line with earlier findings (Brussaard et al. 1997).

Figure 3. Upon parturition and during consecutive lactation stages, spontaneous IPSC waveforms display both changes in current decay kinetics and a suppression in potentiation by 3α-OH-DHP.

A, superimposed sIPSC events obtained from dorsomedial SON neurones at five consecutive stages of female rat reproduction: virgins (VIR), late pregnancy (P20), post-parturition day 1 (PPD1), lactation day 6 (L6) and 6 weeks post-lactation (PL). B, scatter histogram of time constants of current decay of the same experiments shown in A, with a single lognormal function fitted to these data in order to obtain the mean (±s.d.) time constants of sIPSC decay per experiment (see values above plots). C, box histograms of the average sIPSC decay time constants (obtained by fitting monoexponential curves to the decaying phase of each individual sIPSC) under control conditions and after application of 3α-OH-DHP at either 1 or 10 μM for 2-4 min (n > 5 for either stage). The interrupted line indicates the sIPSC decay time constant level of the VIR stage in the absence of 3α-OH-DHP. The inset in C shows an example of the attenuation of the decay time course of sIPSCs upon application of 3α-OH-DHP; averaged current traces of 50 sIPSCs are shown before and after application of 3α-OH-DHP (10 μM); calibration of inset, 10 ms and 100 pA. Statistics: ANOVA followed by a post hoc test for multiple comparisons; *, † and ‡ indicate P < 0·05, P < 0·01 and P < 0·001, respectively, compared with control in the absence of 3α-OH-DHP.

Next, we asked whether the postsynaptic GABAA receptor subtype found at PPD1 is also expressed during subsequent lactation. As reported previously, at PPD1 a distinct subtype of GABAA receptor is expressed by the dorsomedial SON neurones, as shown by (a) a change in the time course of the decay of individual sIPSCs upon parturition, and (b) a concomitant suppression in neurosteroid potentiation of sIPSCs (Fig. 3A-C). Thus the sIPSC decay time constant at PPD1 was 26 ± 6 ms (n= 21, Fig. 3C, P < 0·001 compared with P20) and neither 1 nor 10 μM 3α-OH-DHP significantly affected the sIPSC decay at this stage (Fig. 3C, n= 8). Also, at the L6 stage (Fig. 3A-C, n= 5) and at L10-12 (not shown, n= 12) the sIPSC decay was significantly slower than the decay at P20, being 32 ± 5 and 25 ± 5 ms, respectively (P < 0·001 compared with P20 for both, and not significantly different from PPD1). The suppression of the neurosteroid potentiation was evident during these stages of lactation (Fig. 3C, L6, n= 5, not shown; L10-12, n= 5), and similar to the results observed at the PPD1 stage. The sIPSC decay time constant observed at the L17 stage (23 ± 3 ms, not shown, n= 5) was neither significantly different from that of the VIR nor from that of the P20 stage, but it was significantly faster than that observed at L6 (P < 0·01).

Similar results were encountered 6 weeks after the end of lactation (the ‘PL’ stage, Fig. 3A-C, n= 6). Since the time constant of the sIPSC decay at this stage was 24 ± 4 ms (n.s. from VIR or P20, but P < 0·01 compared with L6) and the neurosteroid potentiation of the GABAA receptors both at 1 and at 10 μM was restored to levels that were not different from those of the VIR, we conclude that after 6 weeks of post-lactation period, the same GABAA receptor subtype is expressed as is present prior to pregnancy.

Taken together, these data suggest that the shift towards the expression of a distinct GABAA receptor starts at parturition, displays a peak at around L6, and is retained up to L10-12. Then at L17, the sIPSC decay appears to be restored to pre-pregnancy levels, concomitant with the putative new ‘insertion’ of large numbers of receptors (i.e. increased sIPSC amplitude) at this stage (see data in Fig. 2B). Thus at or directly after parturition and during the subsequent lactation period (at least up to L12), a novel subtype of GABAA receptor is functionally active, which is distinct from the receptor subtype observed before or during pregnancy, both with respect to its biophysical properties and its modulation by 3α-OH-DHP.

Changes in α1 versusα2 GABAA receptor subunit expression in SON neurones

We quantified the α1 and α2 mRNA levels before and after parturition using competitive PCR. For this analysis we chose the VIR stage and the L6-12 stages. At the VIR stage, sIPSCs are not significantly different from those observed at the P20 stage. L6-12 was chosen since at this stage the effect on the decay of the sIPSCs is maximal, compared with the other stages after parturition. The levels of α1 versusα2 mRNA in micropunches of the dorsomedial SON region were determined in relation to the expression of β-actin within the same samples. Deletion-constructs of α1 and α2 (lacking approximately 100 out of a total of 400- 600 base pairs between the sense and the antisense primer sites) were produced to compete with the endogenous amount of α1 and α2 in the experimental samples. The same was done for β-actin. This revealed that before pregnancy the absolute ratio of α1 : α2 relative to β-actin is 2 : 1 (Fig. 4). During lactation (L6-12) both α1 and α2 were significantly upregulated compared with β-actin; however, the increase in α1 mRNA content was 4-fold, whereas α2 expression was increased at least 20-fold. This suggested that the α1 : α2 ratio was shifted to 1 : 4. Data obtained from animals after 6 weeks of post-lactation showed partial recovery to pre-pregnancy levels. Thus upon parturition, the change in the α1 : α2 ratio as observed in competitive PCR was more robust than was previously observed in our in situ hybridization analysis (Brussaard et al. 1997).

Figure 4. Competitive PCR in the dorsomedial region of the SON reveals robust changes in the levels of α1 and α2 mRNA expression.

Both α-subunit mRNAs (▪, α1; □, α2) were measured relative to the amount of mRNA encoding β-actin. In virgins (n= 4) the within-ratio of α1 : α2 was 2 : 1, whereas at L6-12 (n= 4) the within-ratio was reversed (1 : 4). Partial recovery to pre-pregnancy levels was observed at 6 weeks of post-lactation period (n= 3). The α2 subunit in L6-12 was upregulated to 211 fg (pg actin)−1.

Consequences for the impact of synaptic inhibition of SON neurones during female reproduction

To quantify the functional impact of the multiple changes in the GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic inhibition of dorsomedial SON neurones, we used an analytical method to determine the overall effect of the tonic synaptic inhibition. This resulted, for each reproductive stage and each experimental condition (absence or presence of 3α-OH-DHP), in the calculation of the average ‘synaptic current density’ (SCD). Since one of the key observations during studies on neuroplasticity in the SON was a hypertrophy of magnocellular neurones (Hatton, 1997) we also measured this parameter in order to relate the GABAA receptor data to an independent landmark of neuronal plasticity. In Fig. 5A the cell capacitance (electronic equivalent of the cell membrane surface area) of each reproductive stage is plotted. During pregnancy and at all subsequent stages (including the PPD1 stage up to L17), a significantly larger cell capacitance was observed compared with virgins or post-lactation animals (P < 0·05 for PPD1 and L6 and P < 0·001 for L10-12 and L17, n > 5 for all test groups).

During virginity the SCD amounts to 10·1 ± 2 pC s−1. In principle, the impact of synaptic inhibition at this stage is sensitive to 3α-OH-DHP and might increase to 27·3 ± 5·6 pC s−1 (Fig. 5B). During pregnancy (at P20), the SCD in the absence of 3α-OH-DHP was 9·8 ± 1 pC s−1. However, probably due to the high endogenous concentration of 3α-OH-DHP during pregnancy (Corpéchot et al. 1993), the GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition will amount to 24·7 ± 2·5 pC s−1, which is 2·5-fold larger than the SCD of the VIR group under normal conditions (in the absence of endogenous neurosteroid, Fig. 5B).

Upon parturition (PPD1), the SCD was 14·2 ± 4·7 pC s−1 (Fig. 5A). While at P20 the GABAA receptors are endogenously potentiated by elevated levels of 3α-OH-DHP, and the PPD1 subtype of the GABAA receptor is no longer sensitive to 3α-OH-DHP. Thus in fact the SCD at parturition went from 24·7 ± 2·5 to 14·2 ± 4·7 pC s−1, which may disinhibit the postsynaptic cell.

During the first (L6) and the second week of lactation (L10-12), compared with PPD1, no significant changes were observed in either sIPSC amplitude, decay, interval or neurosteroid sensitivity. Thus the SCD for L6-12 stages was not significantly different from that observed at PPD1 (Fig. 5B). Later on during lactation (L17), due to an effect on the sIPSC amplitude under this condition (Fig. 2), the SCD increased to 19 ± 5 pC s−1 (Fig. 5B). Recalculating the SCD per picofarad of cell capacitance showed that the gradual increase in tonic synaptic inhibition during lactation correlated with an increase in cell capacitance (Fig. 5C).

At the PL stage, we observed a reduction in the SCD in the presumed absence of endogenous neurosteroid. Moreover, 3α-OH-DHP sensitivity of the GABAA receptors was restored, rendering the synaptic inhibition of postsynaptic cell membrane again sensitive to neurosteroid modulation (Fig. 5B and C).

DISCUSSION

Magnocellular neurones and their neuronal-glial connections exhibit a substantial degree of plasticity in the adult CNS (Hatton, 1990; Theodosis & Poulain, 1993; Theodosis & MacVicar, 1996; Hatton, 1997). We reported previously that this neuroplasticity is likely to extend to the regulation of postsynaptic GABAA receptor expression and functioning in oxytocin neurones (Brussaard et al. 1997). We show here that in hypothalamic slices from pregnant rats, there is a robust increase in the frequency at which sIPSCs occur, compared with slices from virgins. This phenomenon, which is consistent with an increase in the number of GABA release sites, may have functional significance, and remains unaltered during parturition and the subsequent first half of lactation. We did not observe a difference between the 3α-OH-DHP-sensitive GABAA receptor subtype that is expressed during late pregnancy and the one observed in slices from virgins. However, a distinct, 3α-OH-DHP-insensitive GABAA receptor subtype expressed at parturition predominated throughout the first and second week of the subsequent lactation period. During the third week of lactation, the number of GABA release sites appeared to be reduced, while the receptor density under individual boutons may have been upregulated. Judging by the average synaptic current decay at this stage, which was intermediate between that found during pregnancy and that found after parturition, we postulate that a mixture of GABAA receptor subtypes (either containing α1 or α2) may be expressed around this time. Finally all changes in fast synaptic inhibition were reversed during the post-lactation period to an extent that it was no longer different from the synaptic inhibition observed prior to the reproductive cycle. This shows that the changes in GABAA receptor subtype activity are of a cyclical nature and may parallel the other phenomena of neuronal plasticity that occur during female reproduction (see, for instance, Stern & Armstrong, 1996).

Number of synaptic release sites

During pregnancy, oxytocin neurones do not fire (or fire only slowly and irregularly), but at parturition, an increased firing of these neurones results in the release of oxytocin into the blood, promoting uterine contractility (Poulain & Wakerley, 1982). During subsequent lactation, short, synchronous, high-frequency bursts of action potentials are observed in response to suckling, followed each time by silent intervals. A reduction of the GABA input via a postsynaptic mechanism as suggested previously (Brussaard et al. 1997) may contribute to the electrical activation of oxytocin neurones at parturition. Additional modulation of GABAA receptor functioning in oxytocin neurones by means of an oxytocin autoreceptor (Brussaard et al. 1996) may also be involved in controlling the firing activity of these cells.

Before parturition, changes in the number of synaptic inputs received by these cells have been observed (Gies & Theodosis, 1994). During pregnancy, glial withdrawal from between adjacent SON somata combined with a hypertrophy of the somata occurs, concomitant with the appearance of novel axosomatic synapses, a process that is maintained during lactation. Weaning the pups results in reversal of these effects, and a second pregnancy repeats the process. The increase in synaptic profiles during the female reproductive cycle only appears to involve oxytocin neurones. Newly appearing synapses consist of a single bouton contacting one, two or more postsynaptic elements, which may contribute to functional synchrony among SON neurones.

Our in situ patch-clamp analysis showed that during late pregnancy, compared with virgin or post-lactation animals, there was a 2-fold increase in the probability that a single quantum of GABA is released by the aggregate of presynaptic boutons impinging on the soma and proximal dendrites of the recorded cells. If one assumes that the probability of spontaneous release of vesicles at individual boutons does not change during the reproductive cycle, this would imply that the number of GABA release sites available per dorsomedial SON cell may have been increased during pregnancy. In our studies (Brussaard et al. 1996, 1997 and this paper) we found no effect of TTX and/or low calcium on the frequency of the spontaneous release of GABA vesicles at room temperature. Therefore we would argue that the effect on the sIPSC frequency that we observed during pregnancy is not caused by a change in calcium-dependent release of vesicles. This still leaves the possibility that, during pregnancy, a change in calcium-independent and TTX-resistant release probability may have caused the change in sIPSC frequency. Nevertheless, our data present the first physiological correlation of morphological data on the formation of novel synaptic contacts between GABAergic neurones and oxytocin neurones in the adult SON (Gies & Theodosis, 1994).

Number of GABAA receptors per synaptic bouton

It has been proposed that the availability of postsynaptic receptors under an active synaptic bouton would limit the amplitude of the sIPSCs (Mody et al. 1994; Nusser et al. 1997). Indeed, a very high probability of GABAA receptor channel opening under individual synaptic boutons has been shown to occur in different preparations (Borst et al. 1994). At synaptic boutons with low to average receptor densities, this probability of opening may be as high as > 90 %, whereas at boutons with a large number of postsynaptic receptors, it was estimated to be between 80 and 90 % (Nusser et al. 1997). It is therefore likely that the amplitude of monoquantal sIPSCs is, to a large extent, linearly dependent on the postsynaptic receptor density under individual synaptic boutons.

We did not observe an effect of allopregnanolone on the amplitude of sIPSCs. Since this neurosteroid is known to increase the burst length of GABAA channels, it is to be expected that under conditions of low (i.e. sub-maximal) receptor occupation and open probability, allopregnanolone would increase the open probability and therefore the sIPSC amplitude. Because this was not observed in our recordings, we conclude that the open probability of the GABAA receptors upon GABA vesicle release must be very high. Therefore we assume that in our recordings the hypothesis holds, that the amplitude of spontaneous monosynaptic events reliably reflects the receptor densities at particular stages of the reproductive cycle.

Change in the expression of GABAA receptor subtypes

SON neurones express both α1 and α2 during all stages of rat female reproduction, although at different relative levels, as suggested by in situ hybridization (Fenelon et al. 1996; Brussaard et al. 1997). We reported recently a correlation between the α1 : α2 subunit mRNA ratio of expression in oxytocin neurones and the decay characteristics of their sIPSCs (Brussaard et al. 1997). Furthermore, we demonstrated that antisense oligo-deletion of the α2 subunit in neurones expressing both α1 and α2 subunits results in the loss of slowly decaying sIPSCs, thus indicating that the α subunit in native GABAA receptors plays a role in determining the decay kinetics of the sIPSCs (Brussaard et al. 1997).

We hypothesize that the relatively high α1 subunit mRNA expression of oxytocin neurones before and during pregnancy gives rise to accumulation of the α1 subunit-dominated receptor subtype at the somatic and proximal dendritic sites of spontaneous GABA release and that this, in turn, underlies the occurrence of relatively fast decaying sIPSCs. Indeed, competitive PCR shows that the pre-pregnancy ratio of α1 : α2 is 2 : 1. Previous in situ hybridization analysis suggested that at parturition, the abundance of the α1 subunit falls to unmask the α2-containing receptors, which will become predominant to generate more slowly decaying sIPSCs. After parturition, the ratio of α1 : α2 mRNA levels in the competitive PCR analysis changed to a much larger extent than in previous semi-quantitative studies on these cells (Fenelon & Herbison, 1996; Brussaard et al. 1997). The direction of the shift in α subunit mRNA contribution and the magnitude of this effect in the PCR analysis correlate well with the functional consequences for the receptor proteins being expressed. Thus while qualitatively in line with previous reports (Fenelon et al. 1996; Brussaard et al. 1997), quantitatively the new data set indicates that it is not so much the level of α1 that falls relative to α2, but rather the level of α2 that increases much more than α1.

Six weeks into the post-lactation period the sIPSC decay was restored to levels that were not significantly different from those obtained in virgin animals. In parallel with this, a large but not complete reduction in both the α1 and α2 mRNA content was observed, compared with the lactation stage. In particular the α2 mRNA relative to β-actin was variable at this stage, making it difficult to assess the average α1 : α2 ratio.

Classical models (Mody et al. 1994) suggest that the decay of sIPSCs is determined by the kinetic properties of the postsynaptic receptors, which in turn depend on the subunit composition of the postsynaptic receptors. In line with the first part of this hypothesis, the prolongation of the average open time of GABAA receptor openings induced by 3α-OH-DHP (Twyman & MacDonald, 1992) was reflected in a prolonged decay of sIPSCs in our present experiments. The idea that the subunit composition of GABAA receptors may determine the channel gating kinetics comes from studies in which it was shown that the decay time constant(s) of recombinant α1-containing receptor responses are relatively fast, whereas α2 (Lavoie & Twyman, 1996)- or α3 (Verdoorn, 1994)-containing receptor responses decay more slowly.

The monoexponential decay of sIPSCs in our recordings on SON neurones and those of others (Puia et al. 1994; De Koninck & Mody, 1996; Draguhn & Heinemann, 1996), differs from that found in a variety of other model systems, where the sIPSCs decayed with two time constants (Edwards et al. 1990; Jones & Harrison, 1993; Borst et al. 1994). Fast desensitization properties of GABAA receptors may account for bi-exponential sIPSC decay (Jones & Westbrook, 1995). Mono-exponential decay of sIPSCs cannot be forced into a bi-exponential mode by attenuation of the lifetime of GABA in the synaptic cleft (Draguhn & Heinemann, 1997). This strongly supports the idea that the fast desensitization of GABAA receptors (Jones & Westbrook, 1995) is a postsynaptic receptor property. Since both the occurrence of distinct GABAA receptor subunit compositions and the cell-specific differences in post-translational modifications of GABAA receptor may contribute to this, it is reasonable to suggest that bi-exponential decay of sIPSCs may occur in some cell types, but not in others.

Neurosteroid regulation of GABAergic synaptic inhibition of oxytocin neurones

The progesterone metabolite 3α-OH-DHP, which is metabolized endogenously in the CNS by oligodendrocytes (Hu et al. 1987), is well known as an allosteric modulator of native and recombinant GABAA receptors in general (Puia et al. 1990; Shingai et al. 1991; Lambert et al. 1995) and in SON cells in particular (Zhang & Jackson, 1994; Brussaard et al. 1997). Given that the in vivo 3α-OH-DHP concentration in the hypothalamus is at its highest during pregnancy (Corpéchot et al. 1993), as a result of the high plasma concentrations of progesterone during this period, it is of interest that in oxytocin neurones parturition induces a substantial suppression of potentiation of GABAA receptors by this neurosteroid. As argued previously, a shift in the relative contribution of α1 : α2 subunit correlates with the change in the pharmacological behaviour of the GABAA receptor in dorsomedial SON neurones around the time of parturition (Brussaard et al. 1997).

In initial studies, recombinant GABAA receptors containing the α1 subunit were reported to be 10-fold more sensitive to 3α-OH-DHP than those utilizing the α2 subunit (Shingai et al. 1991). Although there is a dispute regarding which GABAA receptor subunit mediates the effect of neurosteroids (Lambert et al. 1995), our data indicate that it is the α1 subunit, rather than α2, that enables native GABAA receptors in the adult rat brain to exhibit 3α-OH-DHP sensitivity. However, we cannot exclude the participation of other receptor subunits that may have caused the observed shift in potentiation by 3α-OH-DHP around the time of parturition. In a previous study by Fenelon & Herbison (1996), it remained unclear whether dorsomedial SON neurones express β2 or β3. This is particularly noteworthy since a recent study (Rick et al. 1998) indicated that the β2 subunit may also be involved in mediating the effect of 3α-OH-DHP. In addition, a new class of GABAA receptor subunit(s), called ε, may bring about insensitivity to 3α-OH-DHP, when co-expressed with an α2 and a β subunit (Davies et al. 1997). In contrast, co-expression of ε with α1 and a β subunit (Whiting et al. 1997) yields GABAA receptors that are sensitive to the neurosteroid.

Another GABAA receptor subunit that might cause insensitivity to neurosteroids is the α4 subunit (Smith et al. 1998). Previous in situ hybridization studies (Fenelon et al. 1995) did not detect α4 in the SON in non-reproductive animals. However, upregulation of α4 expression in the SON during female reproductive activity cannot be excluded as yet.

Impact of synaptic inhibition during a female reproductive cycle

Our recordings indicate that sIPSC decay time constants in the presence of the neurosteroid in P20 rats will be in the order of 40-50 ms, compared with 22 ± 2 ms observed before pregnancy. The physiological significance of this observation lies in the fact that the increase in synaptic inhibition via a postsynaptic mechanism, even without altering the extent of presynaptic release of GABA, would provide dorsomedial SON neurones with a powerful synaptic safety switch to prevent premature release of oxytocin during pregnancy.

In the absence of 3α-OH-DHP, the SCD at P20 is not significantly different from that observed at the VIR stage. This suggests that although the total number of GABA release sites may have doubled during pregnancy, the variation in sIPSC amplitude and/or decay around that time counteracts the expected increase in SCD that one would predict to occur if only a shift in sIPSC interval had occurred.

We showed previously that during late pregnancy, 3α-OH-DHP-potentiated GABAA receptors may restrain the firing activity of oxytocin neurones, whereas upon parturition 3α-OH-DHP no longer affects their activity (Brussaard et al. 1997). The importance of such a mechanism may be further magnified by the known presence of 3α-OH-DHP-sensitive GABAA receptors on magnocellular nerve terminals in the pituitary gland (Zhang & Jackson, 1994). Indeed, intravenous application of bicuculline during late pregnancy increases the basal plasma concentration of oxytocin very effectively (Brussaard et al. 1997).

Thus it is most likely that the loss of GABAA receptor sensitivity to 3α-OH-DHP, coupled with the falling levels of endogenous 3α-OH-DHP, will contribute to the in vivo disinhibition of oxytocin neurones, and thereby enable their electrical activation by other neurotransmitter inputs at the appropriate time (Herbison et al. 1997; Luckman & Larsen, 1997; Moos et al. 1997).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tineke Broers-Vendrig for technical assistance and Theo de Vlieger, Huibert Mansvelder, Paul van Soest and Hind Tol-Steye for their comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. Part of the support for this work was obtained from a Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences grant to A. B. B. In addition, a NATO collaborative grant to A. B. B. and Lorna W. Role (Columbia University, New York, USA) was used in support of the work with P. D.

References

- Borst JGG, Lodder JC, Kits KS. Large amplitude variability of GABAergic IPSCs in melanotrophs from Xenopus laevis: evidence that quantal size differs between synapses. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;71:639–655. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brussaard AB, Kits KS, Baker RE, Willems WPA, Leyting-Vermeulen JW, Voorn P, Smit AB, Herbison AE. Plasticity in fast synaptic inhibition of adult oxytocin neurones caused by switch in GABAA receptor subunit expression. Neuron. 1997;19:1103–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brussaard AB, Kits KS, de Vlieger TA. Postsynaptic mechanism of depression of GABAergic synapses by oxytocin in the supraoptic nucleus of immature rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:495–507. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpéchot C, Young J, Calcel M, Wehrey C, Veltx JN, Touyer G, Mouren M, Prasad VVK, Banner C, Sjovall J, Baulieu EE, Robel P. Neurosteroid 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one and its precursors in the brain, plasma, and steroidogenic glands of male and female rats. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1003–1009. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.3.8365352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PA, Hanna MC, Hales TG, Kirkness EF. Insensitivity to anaesthetic agents conferred by a class of GABAA receptor subunit. Nature. 1997;385:820–823. doi: 10.1038/385820a0. 10.1038/385820a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koninck Y, Mody I. The effects of raising intracellular calcium on synaptic GABAA receptor channels. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1365–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00063-9. 10.1016/S0028-3908(96)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draguhn A, Heinemann U. Different mechanisms regulate IPSC kinetics in early postnatal and juvenile hippocampal granule cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:3983–3993. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA, Konnerth A, Sakmann B. Quantal analysis of inhibitory synaptic transmission in the dentate gyrus of rat hippocampal slices: a patch-clamp study. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;430:213–249. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenelon VS, Herbison AE. Characterisation of GABAA receptor γ-subunit expression by magnocellular neurones in rat hypothalamus. Molecular Brain Research. 1995;34:45–56. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00130-k. 10.1016/0169-328X(95)00130-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenelon VS, Herbison AE. Plasticity in GABAA receptor subunit mRNA expression by hypothalamic magnocellular neurones in the adult rat. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:4872–4880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-04872.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenelon VS, Sieghart W, Herbison AE. Cellular localisation and differential distribution of GABAA receptor subunit proteins and messenger RNAs within hypothalamic magnocellular neurones. Neuroscience. 1995;64:1129–1143. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00402-q. 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00402-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gies U, Theodosis DT. Synaptic plasticity in the rat supraoptic nucleus during lactation involves GABA innervation and oxytocin neurones: a quantitative immunocytochemical analysis. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:2861–2869. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02861.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton GI. Emerging concepts of structure-function dynamics in adult brain: the hypothalamo-neurohypophysial system. Progress in Neurobiology. 1990;34:437–504. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(90)90017-b. 10.1016/0301-0082(90)90017-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton GI. Function-related plasticity in hypothalamus. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1997;20:375–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.375. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE, Voisin DV, Douglas AJ, Chapman C. Profile of monoamine and excitatory amino acid release in rat supraoptic nucleus over parturition. Endocrinology. 1997;138:33–40. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.1.4859. 10.1210/en.138.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu ZY, Bourreau E, Jung-Testas I, Robel P, Baulieu E-E. Neurosteroids: oligodendrocyte mitochondria convert cholesterol to pregnenolone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1987;84:8215–8219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MV, Harrison NL. Effects of volatile anesthetics on the kinetics of inhibitory postsynaptic currents in cultured rat hippocampal neurones. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70:1339–1349. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MV, Westbrook GL. Desensitized states prolong GABAA channel responses to brief agonist pulses. Neuron. 1995;15:181–191. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90075-6. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JJ, Belelli D, Hill-Venning C, Peters JA. Neurosteroids and GABAA receptor function. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1995;16:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89058-6. 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)89058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie AM, Twyman RE. Direct evidence for diazepam modulation of GABAA receptor microscopic affinity. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1383–1392. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00077-9. 10.1016/S0028-3908(96)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckman SM, Larsen PJ. Evidence for the involvement of histaminergic neurones in the regulation of the rat oxytocinergic system during pregnancy and parturition. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;501:649–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.649bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I, De Koninck Y, Otis TS, Soltesz I. Bridging the cleft at GABA synapses in the brain. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:517–524. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90155-4. 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos FC, Rossi K, Richard Ph R. Activation of NMDA receptors regulates basal electrical activity of oxytocin and vasopressin neurones in lactating rats. Neuroscience. 1997;77:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00536-2. 10.1016/S0306-4522(96)00536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Cull-Candy S, Farrant M. Differences in synaptic GABAA receptor number underlie variation in GABA mini amplitude. Neuron. 1997;19:697–709. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80382-7. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulain PA, Wakerley JB. Electrophysiology of hypothalamic magnocellular neurones secreting oxytocin and vasopressin. Neuroscience. 1982;7:773–808. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90044-6. 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puia G, Costa E, Vicini S. Functional diversity of GABA-activated Cl−currents in Purkinje versus granula neurones in rat cellebellar slices. Neuron. 1994;12:117–126. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90157-0. 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puia G, Santi M-R, Vicini S, Pritchett DB, Purdy R, Paul SM, Seeburg PH, Costa E. Neurosteroids act on recombinant human GABAA receptors. Neuron. 1990;4:759–765. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90202-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes CH, Morrell JI, Pfaff DW. Immunohistochemical analysis of magnocellular elements in rat hypothalamus: distribution and numbers of cells containing neurophysin, oxytocin, and vasopressin. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1981;198:45–64. doi: 10.1002/cne.901980106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rick CE, Ye Q, Finn SE, Harrison NL. Neurosteroid act on the GABAA receptor at sites on the N-terminal side of the middle of TM2. NeuroReport. 1998;9:379–383. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingai R, Sutherland ML, Barnard EA. Effects of subunit types of the cloned GABAA receptor on response to a neurosteroid. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1991;206:77–80. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(91)90149-c. 10.1016/0922-4106(91)90149-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS, Gong QH, Hsu F-C, Markowitz RS, Ffrench-Mullen JMH, Li X. GABAA receptor α4 subunit suppression prevents withdrawal properties of an endogenous steroid. Nature. 1998;392:926–930. doi: 10.1038/31948. 10.1038/31948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern JE, Armstrong WE. Changes in the electrical properties of supraoptic oxytocin and vasopressin neurones during lactation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:4861–4871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-04861.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GJ, Dodt H-U, Sakmann B. Patch clamp recordings from the soma and dendrites of neurones in brain slices using infrared video microscopy. Pflügers Archiv. 1993;423:511–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00374949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodosis DT, MacVicar B. Neurone-glia interactions in the hypothalamus and pituitary. Trends in Neurosciences. 1996;19:363–367. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodosis DT, Poulain DA. Activity-dependent neuronal-glial and synaptic plasticity in the adult mammalian hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 1993;57:501–535. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90002-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twyman RE, MacDonald RL. Neurosteroid regulation of GABAA receptor single-channel kinetic properties of mouse spinal cord neurones in culture. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;456:215–245. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Pol AN. Dual ultrastructural localization of two neurotransmitter related antigens: colloidal gold labelled neurophysin immunoreactive supraoptic nucleus receive peroxidase labelled glutamate decarboxylase or gold labelled GABA immunoreactive synapses. Journal of Neuroscience. 1985;5:2940–2945. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-11-02940.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoorn TA. Formation of heteromeric GABAA receptors containing two different α subunits. Molecular Pharmacology. 1994;45:475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DL, Herbison AE, Poulain DA. Central inhibitory effects of muscimol and bicuculline on the milk ejection reflex in the anaesthetized rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;483:211–224. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting PJ, McAllister G, Vasilatis D, Bonnert TP, Heavens RP, Smit DW, Hewson L, O'Donnel R, Rigby MR, Sirinathsinghji DJS, Marshall G, Thompson SA, Wafford KA. Neuronally restricted RNA splicing regulates the expression of a novel GABAA receptor subunit conferring atypical functional properties. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:5027–5037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05027.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SJ, Jackson MB. Neuroactive steroids modulate GABAA receptors in peptidergic nerve terminals. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 1994;6:533–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]