Abstract

Smooth muscle contraction is activated primarily by the Ca2+-calmodulin (CaM)-dependent phosphorylation of the 20 kDa light chains (LC20) of myosin. Activation can also occur in some instances without a change in intracellular free [Ca2+] or indeed in a Ca2+-independent manner. These signalling pathways often involve inhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase and unmasking of basal kinase activity leading to LC20 phosphorylation and contraction.

We have used demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips and isolated chicken gizzard myofilaments in conjunction with the phosphatase inhibitor microcystin-LR to investigate the mechanism of Ca2+-independent phosphorylation of LC20 and contraction.

Treatment of Triton X-100-demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips with microcystin at pCa 9 triggered a concentration-dependent contraction that was slower than that induced by pCa 4.5 or 6 but reached comparable steady-state levels of tension.

This Ca2+-independent, microcystin-induced contraction correlated with phosphorylation of LC20 at serine-19 and threonine-18.

Whereas Ca2+-dependent LC20 phosphorylation and contraction were inhibited by a synthetic peptide (AV25) based on the autoinhibitory domain of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), Ca2+-independent, microcystin-induced LC20 phosphorylation and contraction were resistant to AV25.

Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity was also detected in chicken gizzard smooth muscle myofilaments and catalysed phosphorylation of endogenous myosin LC20 at serine-19 and/or threonine-18. This is in contrast to MLCK which phosphorylates threonine-18 only after prior phosphorylation of serine-19.

Gizzard Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase could be separated from MLCK by differential extraction from myofilaments and by CaM affinity chromatography. Its activity was resistant to AV25.

We conclude that inhibition of smooth muscle myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP) unmasks the activity of a Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase associated with the myofilaments and distinct from MLCK. This kinase, therefore, probably plays a role in Ca2+ sensitization and Ca2+-independent contraction of smooth muscle in response to stimuli that act via Ca2+-independent pathways, leading to inhibition of MLCP.

The principal mechanism of regulation of smooth muscle contraction and relaxation involves myosin phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, respectively (Somlyo & Somlyo, 1994). Contractile stimuli often increase intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) via Ca2+ entry from the extracellular milieu through voltage-gated or receptor-operated Ca2+ channels or Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum through Ca2+ release channels (inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors or ryanodine receptors). The increase in [Ca2+]i (typically from a resting level of ∼80-200 nM to a peak of ∼500-700 nM) saturates the Ca2+-binding sites of calmodulin (CaM). CaM contains four EF-hand Ca2+-binding sites. Recent evidence suggests that the two high-affinity C-terminal sites contain bound Ca2+ at normal resting [Ca2+]i and, in this state, CaM is bound to the target enzyme myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) but does not activate it (Bayley et al. 1996; Johnson et al. 1996). The increase in [Ca2+]i in response to stimulation results in rapid binding of Ca2+ to the low-affinity N-terminal Ca2+-binding sites of CaM leading to activation of MLCK. This occurs via a conformational change in the kinase involving removal of an autoinhibitory domain from the active site, thereby allowing access to the substrate myosin (Pearson et al. 1988). The autoinhibitory domain of MLCK (leucine-774- valine-807 of the chicken gizzard enzyme) overlaps the CaM-binding domain (alanine-796-serine-815). The latter is a 1-8-14 type B CaM-binding motif, having hydrophobic anchoring side chains (tryptophan-800 and leucine-813) at the beginning and end of the CaM-binding sequence separated by 12 amino acids, and a hydrophobic side chain (valine-807) at position 8 (Rhoads & Friedberg, 1997). When bound to CaM this domain of MLCK assumes a basic amphiphilic α-helical structure, the N-terminus of the MLCK CaM-binding domain interacting with the C-terminal lobe of CaM and the C-terminus of the CaM-binding domain with the N-terminal lobe of CaM (Ikura et al. 1992; Meador et al. 1992). Mutagenesis of tryptophan-800 dramatically reduces the affinity of MLCK for CaM, indicating the importance of this side chain in the MLCK-CaM interaction (Matsushima et al. 1994).

The active kinase (-CaM-MLCK) catalyses transfer of the terminal (γ) phosphoryl group of MgATP2- to serine-19 of the two 20 kDa light chain subunits (LC20) of myosin II. This simple phosphorylation reaction activates cross-bridge cycling, i.e. force development or shortening of the muscle (Hoar et al. 1979; Walsh et al. 1982). With few exceptions, MLCK-catalysed LC20 phosphorylation is necessary and sufficient for smooth muscle contraction. Relaxation generally results following a return of [Ca2+]i to resting levels, due to extrusion of Ca2+ from the cell by the sarcolemmal Ca2+-ATPase and the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger or uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane Ca2+-ATPase, resulting in dissociation of Ca2+ from the N-terminal sites of CaM (Bayley et al. 1996; Johnson et al. 1996), inactivation of MLCK and dephosphorylation of myosin catalysed by myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP) (Hartshorne et al. 1998).

MLCK is a very specific protein kinase: its only known substrate in vivo is myosin (Gallagher et al. 1997). At high concentrations in vitro, MLCK can phosphorylate threonine-18 of LC20 in addition to serine-19 (Ikebe et al. 1986), and diphosphorylation at serine-19 and threonine-18 has been described in stimulated intact smooth muscles (e.g. Colburn et al. 1988). MLCK is anchored to the thin filaments in smooth muscle via an N-terminal actin-binding domain (Kanoh et al. 1993). Since MLCK-depleted myofilaments have ∼20-fold higher affinity for MLCK than does F-actin, the interaction of MLCK with thin filaments involves more than simple actin binding (Lin et al. 1997).

MLCP is a type 1 protein serine/threonine phosphatase composed of a 38 kDa catalytic subunit (the δ isoform), a 130 kDa myosin-binding subunit that targets the phosphatase to the thick filaments and a 21 kDa subunit of unknown function (Hartshorne et al. 1998). This phosphatase is commonly referred to as PP1M to indicate its classification as a type 1 phosphatase and its physical association with myosin.

From characterization of these regulatory enzymes, it is now clear that the contractile apparatus of smooth muscle is a multimeric complex of contractile proteins (myosin, actin and tropomyosin) and regulatory proteins (MLCK, CaM, PP1M and probably others such as the actin-binding proteins caldesmon and calponin). Indeed, all these proteins are retained in permeabilized and demembranated smooth muscle tissues and in isolated myofilaments.

It was previously thought that regulation of myosin phosphorylation levels and therefore smooth muscle contraction was effected exclusively via activation and inactivation of MLCK, the phosphatase being constitutively active. This is now clearly not the case. Three independent mechanisms of regulation of PP1M have been described. (1) Phosphorylation of the 130 kDa subunit of PP1M leads to inhibition of the phosphatase (Ichikawa et al. 1996). This may occur via activation of Rho-associated kinase (Kimura et al. 1996), a kinase that is activated by the small GTPase RhoA. (2) The second messenger arachidonic acid interacts directly with PP1M, inducing dissociation of the holoenzyme and a reduction in phosphatase activity towards phosphorylated myosin (Gong et al. 1992b). (3) Activation of protein kinase C (PKC) leads to inhibition of PP1M (Masuo et al. 1994). This may be mediated by a novel heat-stable protein, CPI-17, which becomes a very potent inhibitor of PP1M upon phosphorylation by PKC (Li et al. 1998). The possibility that arachidonic acid may activate an atypical (Ca2+- and diacylglycerol-independent) PKC isoenzyme, leading to PP1M inhibition, has also been proposed (Gailly et al. 1997). These recent advances have largely arisen from studies of Ca2+ sensitization of smooth muscle contraction, i.e. treatment of permeabilized smooth muscles at a fixed, submaximal [Ca2+] with a variety of agents (e.g. α1-adrenergic and muscarinic agonists, GTPγS, diacylglycerol or arachidonic acid) leading to an increase in force concomitant with an increase in LC20 phosphorylation. Ca2+ sensitization via these pathways is interpreted as PP1M inhibition leading to an increase in the MLCK : PP1M activity ratio, LC20 phosphorylation and contraction without a change in [Ca2+]i. Although it is generally assumed that basal activity of MLCK is responsible for the observed increase in LC20 phosphorylation, this has not been established.

Phosphatase inhibitors such as okadaic acid, calyculin A, microcystin and tautomycin have proved to be very useful tools in the study of the regulation of smooth muscle contraction due to their potency and specificity. Several examples have been reported of Ca2+-independent contractions of intact and permeabilized smooth muscles in response to okadaic acid (Shibata et al. 1982; Ozaki et al. 1987; Hartshorne et al. 1989; Hirano et al. 1989; Obara et al. 1989; Gong et al. 1992a), calyculin A (Hartshorne et al. 1989; Ishihara et al. 1989; Suzuki & Itoh, 1993), tautomycin (Hori et al. 1991; Gong et al. 1992a) or microcystin (Gong et al. 1992a; Shirazi et al. 1994; Ikebe & Brozovich, 1996). Where investigated, these contractions correlate with an increase in myosin phosphorylation.

In this study, we investigated the mechanism whereby phosphatase inhibition leads to an increase in myosin phosphorylation. We used demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle, which exhibits a Ca2+-independent contractile response to microcystin. This contraction correlates with an increase in LC20 phosphorylation at serine-19 and threonine-18 catalysed by a kinase distinct from MLCK. Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity was also detected in chicken gizzard smooth muscle myofilaments and could be separated from MLCK. This kinase, therefore, is a candidate LC20 kinase responsible for Ca2+-independent contraction and Ca2+ sensitization of contraction due to PP1M inhibition.

METHODS

Contractility measurements

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (300-500 g) were killed by inhalation of a lethal dose of halothane and decapitated, according to a research protocol consistent with the standards of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by the local Animal Care Committee of the Medical Research Council of Canada. Rat caudal arteries were cleaned and the endothelial cell layer removed mechanically. Helical strips (∼1 mm × 5-7 mm) were cut and tied between a solid support and a force transducer, either horizontally on a bubble plate or vertically in a cuvette. Solution changes were effected rapidly by rotation of the bubble plate or replacement of the solution in the cuvette with a pipette. A resting tension of 50 mg was applied to all strips, which were equilibrated for 30 min in Hepes-Tyrode (HT) buffer (mM: 10 Hepes, 137 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 5.6 glucose, pH 7.4). All buffers were at room temperature (20°C) and those used for intact strips were pre-oxygenated with 100 % O2.

Muscle strips were repeatedly contracted with 117 mM excess KCl in HT buffer (with equimolar NaCl removed) while still intact until stable responses were obtained. The strips were demembranated with 1 % (v/v) Triton X-100 in (mM): 30 Tes, 50 KCl, 5 K2EGTA, 150 sucrose, 0.5 dithioerythritol, pH 7.4 for 2 h at 20°C. Experimental solutions contained (mM): 3.2 MgATP, 2 free Mg2+, 12 phosphocreatine, 0.5 sodium azide, 30 Tes and 15 U ml−1 creatine phosphokinase, 1 μM CaM, pH 6.9, with ionic strength adjusted to 150 mM with potassium propionate. Desired free Ca2+ levels (expressed as pCa) were obtained by mixing stock solutions containing K2EGTA and K2CaEGTA. We did not routinely include protease inhibitors in the demembranating or subsequent contraction solutions since this was found to be unnecessary. No difference in the time course of contraction or steady-state tension in response to pCa 4.5 or 10 μM microcystin at pCa 9 was observed in the absence or presence of a cocktail of protease inhibitors (1 μM leupeptin, 0.1 mg ml−1 soybean trypsin inhibitor, 1 μM pepstatin and 1 μg ml−1 aprotinin). There was no evidence of proteolysis since the Coomassie Blue-stained SDS gel patterns of muscle strips demembranated in the absence or presence of protease inhibitors were identical. Furthermore, there was no evidence of MLCK degradation by Western blotting.

Analysis of protein phosphorylation in demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips using [γ-32P]ATP

Muscle strips were demembranated as described above and incubated in either pCa 9 or pCa 6 solution containing 3.2 mM [γ-32P]ATP (specific activity ∼70 c.p.m. pmol−1) without an ATP regenerating system (i.e. without phosphocreatine and creatine phosphokinase). Contractions were induced at pCa 9 by addition of microcystin (1 μM); control muscle strips were maintained at pCa 9 until the Ca2+- or microcystin-induced contractions were maximal (∼45- 60 min). Tissues were frozen at selected times by immersion in a slurry of dry ice with 10 % (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) in acetone, washed eight times (3 min each) with 0.5 ml of 10 mM DTT in acetone and lyophilized overnight. Dried muscle strips were homogenized in 0.1 ml of 2 × SDS gel sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) containing 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 100 μg ml−1 pepstatin A in a 0.2 ml Wheaton glass-glass hand-operated homogenizer. Samples were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and the homogenizer was rinsed with 4 × 25 μl of buffer. Protein extraction was completed by constant rotation of the Eppendorf tubes at 4°C for 2 h. Extracted protein was separated from cell debris by centrifugation in a microfuge at maximum speed (∼10 000 g) for 30 min at 4°C. The radioactivity in the supernatant and pellet was quantified by Cerenkov counting in a Beckman LS 6000 scintillation counter to enable calculation of the efficiency of protein extraction: the amount of radioactivity recovered in the supernatant was 95.6 ± 2.2 % (n = 5) for control strips incubated at pCa 9, 94.1 ± 2.8 % (n = 5) for muscle strips treated with microcystin at pCa 9 and 95.5 ± 2.1 % (n = 4) for muscle strips treated at pCa 6. Each supernatant was subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and autoradiography (Winder & Walsh, 1990). In some cases, Western blotting was carried out using antibodies to myosin LC20 (see below).

Quantification of LC20 phosphorylation in muscle strips

LC20 phosphorylation was analysed by Western blotting. Muscle strips were frozen by immersion in a slurry of dry ice with 10 % (w/v) TCA and 10 mM DTT in acetone for 1 min initially, then for another 10 min after removal from the force transducer and support. Strips were washed in 10 mM DTT in acetone, lyophilized overnight and stored at -80°C. Proteins were extracted from tissue strips in 0.1 ml per strip of (mM): 200 Tris, 220 glycine, 10 DTT, 10 EGTA, 1 EDTA, 1 PMSF and 6 M deionized urea, 0.6 M KI and 0.1 % (w/v) Bromophenol Blue by constant rotation in a microcentrifuge tube for 3h at 20°C. After filtration through a 0.45 μm Centricon filter (Millipore), the unphosphorylated and phosphorylated forms of LC20 extracted from the frozen strips were separated by urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis. LC20 phosphorylation was quantified by densitometric scanning using a Pharmacia Image Master desktop scanning system (Uppsala, Sweden). In separate experiments we established the linear range for the relationship between LC20 signal intensity (optical density × mm2) and protein amount.

Urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis

Unphosphorylated (LC20), monophosphorylated (P1-LC20) and diphosphorylated (P2-LC20) forms of LC20 were separated by urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis using a modification of the method of Sobieszek & Jertschin (1986) with 0.75 mm thickness mini slab gels. The separating gel contained 10 % (w/v) acrylamide, 0.27 % (w/v) N,N’-methylene bisacrylamide (Bis), 0.375 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 40 % (v/v) glycerol, 0.5 % (w/v) ammonium persulphate and 0.044 % (w/v) N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) and the stacking gel contained 2.25 % (w/v) acrylamide, 0.12 % (w/v) Bis, 0.12 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 8.5 M urea, 0.6 % (w/v) ammonium persulphate and 0.2 % (w/v) TEMED. The running buffer was 50 mM Trizma base, 0.1 M glycine (pH 8.8) and electrophoresis was carried out at 6 mA per gel for 5 h.

Western blotting

Proteins separated by urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (0.2 μm) in 10 mM sodium cyclohexylaminopropane sulphonic acid, pH 11, in a large transblot cell (Bio-Rad) at 20 V and 4°C for 16 h. After air drying, the membrane was blocked with 5 % (w/v) skimmed milk in TBST (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.5 M NaCl and 0.05 % (v/v) Tween-20) for 2 h at 20°C and incubated in primary antibody in 1 % (w/v) skimmed milk in TBST for 1 h at 20°C. Three 10 min washes with TBST removed excess primary antibody. The membrane was then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-rabbit or anti-mouse, both purchased from Boehringer-Mannheim and used at 1 : 5000 dilution) in 1 % (w/v) skimmed milk in TBST for 1 h at 20°C, washed three times (10 min each) with TBST and once (10 min) with TBS prior to developing with the Supersignal CL-HRP Substrate System (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL, USA) as described by the manufacturer. Western blotting of urea/glycerol gels with enhanced chemiluminescence detection was performed using three different antibodies: the ‘general LC20 antibody’, a polyclonal antibody raised in rabbits, which recognizes all phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of LC20 and was used at 1 : 5000 dilution (Mita & Walsh, 1997); the pLC1 antibody, a monoclonal antibody, which specifically recognizes LC20 phosphorylated only at serine-19 and was used at 1:200 dilution; and the pLC2 antibody, a peptide-directed polyclonal antibody raised in rabbits, which specifically recognizes LC20 phosphorylated at both serine-19 and threonine-18 and was used at 1 : 5000 dilution (Sakurada et al. 1998). pLC1 and pLC2 antibodies were generously provided by Drs Y. Sasaki and M. Seto, Asahi Chemical Industry Company, Ltd, Shizuoka, Japan.

Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (0.2 μm) in 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20 % (v/v) methanol, 0.1 % (w/v) SDS, pH 8.3 at 40 V and 4°C for 16 h. Subsequent procedures were as described above with the exception that the primary antibodies were pLC1, pLC2, 1.0 μg ml−1 monoclonal anti-(chicken gizzard MLCK) (Adachi et al. 1983) or 0.25 μg ml−1 polyclonal anti-(chicken gizzard MLCK) (Paul et al. 1995).

Kinase assays: purified MLCK

MLCK was incubated at 30°C in (mM): 25 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 60 KCl, 10 MgCl2, 10 DTT, 0.1 CaCl2 or 10 EGTA, and 0.1 % (v/v) Tween-80, 10 μM microcystin, 0.2 mM [γ-32P]ATP (150- 380 c.p.m. pmol−1) with 10 μg ml−1 CaM and either MLC11-23, LC20 or myosin at concentrations indicated in the figure legends. Reactions were started by addition of radiolabelled ATP. In some cases, reactions were stopped by spotting 20 μl of reaction mixture onto squares (1 cm × 1 cm) of P81 phosphocellulose paper (Whatman) and immersing in a beaker containing 0.5 % (v/v) H3PO4. Papers were washed with 3 × 500 ml of 0.5 % (v/v) H3PO4 (5 min each) and once with 500 ml of acetone (5 min) and air dried, then 32P was quantified by Cerenkov counting. In other cases, reactions were stopped by adding samples (60 μl) to an equal volume of SDS gel sample buffer and boiling prior to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. LC20 and MLCK bands (identified by autoradiography) were cut out of the gel and 32P incorporation was quantified by Cerenkov counting.

Production of constitutively active MLCK

MLCK was digested with trypsin by a modification of the method of Ikebe et al. (1987) as follows. Purified MLCK (0.13 mg ml−1) was incubated for 10 min at 25°C in (mM): 30 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 KCl, 1 EGTA and 0.1 % (v/v) Tween-80 with 2.6 μg ml−1p-tosylphenylalanylchloromethylketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin. Digestion was stopped by addition of 0.1 mg ml−1 soybean trypsin inhibitor. Undigested MLCK had a specific activity in the presence of Ca2+ of 193.5 mol Pi min−1 (mol MLCK)−1 and no significant activity in the absence of Ca2+; trypsin-digested MLCK had a specific activity in the presence of Ca2+ of 172.0 mol Pi min−1 (mol MLCK)−1 and in the absence of Ca2+ of 161.3 mol Pi min−1 (mol MLCK)−1. Western blotting of undigested and digested MLCK confirmed production of the 61 kDa constitutively active MLCK fragment from the 130 kDa intact kinase following trypsin treatment (both the monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies to MLCK recognize the constitutively active fragment). Time course experiments established that a digestion time of 10 min was optimal for generation of constitutively active MLCK.

Preparation of chicken gizzard myofilaments

Myofilaments were prepared using a procedure similar to that described by Sobieszek & Bremel (1975). Fresh chicken gizzards (200 g) obtained from Lilydale Poultry Co. (Calgary, Canada) were transported to the laboratory on ice, trimmed, minced and homogenized with a Brinkmann Polytron in 5 volumes of Buffer A (mM: 20 imidazole-HCl (pH 6.9), 60 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 1 DTT, 0.5 PMSF and 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin) then centrifuged at 20 000 g for 15 min. The pellet was washed 3 times by resuspending in 5 volumes of Buffer A containing 0.5 % (v/v) Triton X-100 or 0.3 % (v/v) Triton X-100 (final wash) and centrifuging as previously. The final myofilament pellet was resuspended in 5 volumes of Buffer A and stored at -80°C.

Kinase assays: chicken gizzard myofilaments

Chicken gizzard myofilaments (0.64 mg protein ml−1) were incubated at 30°C in (mM): 25 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 60 KCl, 10 MgCl2, 10 DTT, 0.1 CaCl2 or 10 EGTA and 10 μM microcystin, 10 μg ml−1 CaM and 1 mM [γ32P]ATP (60-70 c.p.m. pmol−1) or unlabelled ATP for selected times. Reactions were started by addition of ATP and incubated at 30°C. Reactions were terminated at selected times by addition of an equal volume (60 μl) of SDS gel sample buffer and boiling. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, stained with Coomassie Blue and exposed to X-ray film. Relative levels of LC20 phosphorylation were determined by Cerenkov counting of gel slices. To correct for slight variations in protein loading, counts were normalized for LC20 protein content as determined by gel scanning densitometry. Stoichiometry of phosphorylation was calculated with reference to LC20 phosphorylated to exactly 1.0 mol Pi (mol LC20)−1 at 2.5 min in the presence of Ca2+, determined by urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis. MLCK concentration in these reactions was 10 μg ml−1 as determined by Western blot analysis using known amounts of purified MLCK as a standard. Myosin concentration was 0.15 mg ml−1 as determined by SDS-PAGE analysis in comparison with purified myosin.

For identification of the sites of phosphorylation in LC20 using antibodies, reactions were stopped with TCA, centrifuged and the pellet was washed with acetone, lyophilized in ammonium bicarbonate, resuspended in 120 μl of urea/glycerol gel sample buffer and filtered through a 0.45 μm Centricon filter. Samples of 30 μl were applied per gel lane and subjected to urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis and Western blotting as described above.

Myofilament extraction

Fresh myofilaments were recovered by centrifugation and the pellet resuspended in 2.5 volumes of Buffer B (mM: 20 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 80 KCl, 30 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 1 DTT, 0.5 PMSF and 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin) with gentle stirring for 30 min. After centrifugation at 20 000 g for 30 min, the extraction was repeated and the supernatants combined (E1) and stored at -80°C. The pellet was resuspended in 2.5 volumes of Buffer B. An equal volume of Buffer B containing 4 M NaCl was added slowly while stirring and mixed for 30 min. After centrifugation as above, the supernatant (E2) was stored at -80°C. The extracted myofilaments (P) were washed and resuspended in 5 volumes of Buffer A and stored at -80°C.

Quantification of LC20 kinase activity in myofilament extracts

Extracts were incubated at 30°C in (mM): 20 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 60 KCl, 10 MgCl2, 10 DTT, 0.1 CaCl2 or 10 EGTA, and 0.1 % (v/v) Tween-80, 10 μg ml−1 CaM, 0.5 mg ml−1 myosin, 10 μM microcystin and 0.2 mM [γ-32P]ATP (50-100 c.p.m. pmol−1) in the absence or presence of 50 μM AV25. Reactions containing Ca2+ used E1 at 1 : 5000 dilution and E2 at 1 : 500 dilution. Reactions containing EGTA used E1 or E2 at 1 : 20 dilution. Myosin phosphorylation was assayed using the P81 paper assay for Ca2+ reactions or by quantification of LC20 in gel slices after SDS-PAGE/autoradiography for EGTA reactions. Activities were calculated from the initial rates of phosphorylation.

Phosphopeptide mapping and phosphoamino acid analysis

Monophosphorylated LC20 (P1-LC20) in urea/glycerol gel slices was digested with TPCK-trypsin and the peptides were separated by two-dimensional thin layer electrophoresis/chromatography as described by Colburn et al. (1988). Phosphopeptides were detected by autoradiography and this region of the plate was scraped off. The phosphopeptide was extracted and subjected to acid hydrolysis and two-dimensional phosphoamino acid analysis as described by Colburn et al. (1988), except that hydrolysis was effected in 250 μl of 6 M HCl at 110°C for 2 h, and first-dimension electrophoresis was carried out for 80 min and second-dimension electrophoresis for 70 min. Unlabelled phosphoamino acid standards were added to the hydrolysate prior to two-dimensional electrophoresis and were detected by ninhydrin staining. Radiolabelled phosphoamino acids were detected by autoradiography.

Phosphorylation of LC20 by PKC

Isolated LC20 (0.1 mg ml−1) was incubated at 30°C for 10 min in (mM): 20 Hepes (pH 7.5), 10 MgCl2, 10 DTT, 0.1 CaCl2 and 0.3 mg ml−1 phosphatidylserine, 62 μg ml−1 1,2-diolein, 0.03 % (v/v) Triton X-100 and 2 mM [γ-32P]ATP (2500 c.p.m. pmol−1) containing 0.1 μg ml−1 PKC. Phosphorylated LC20 was subjected to urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis, phosphopeptide mapping and phosphoamino acid analysis as described above.

Separation of MLCK and Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase by CaM affinity chromatography

The 2 M NaCl extract of chicken gizzard myofilaments (E2) was filtered through glass wool and dialysed against 5 × 8 l of Buffer C (mM: 20 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 1 DTT). The dialysate was applied to a column (1.5 cm × 10 cm) of Q-Sepharose fast-flow (Pharmacia) previously equilibrated with Buffer C and unbound proteins were washed off the column with Buffer C. Bound proteins were eluted with a 200 ml linear salt gradient (0-0.5 M NaCl) at a flow rate of 120 ml h−1 collecting 2.6 ml fractions. Fractions were assayed for their ability to phosphorylate myosin under the following conditions (mM): 25 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 60 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 1 DTT, 0.1 CaCl2 or 10 EGTA and 0.1 % (v/v) Tween-80, 10 μM microcystin, 10 μg ml−1 CaM, 0.5 mg ml−1 myosin, 0.2 mM [γ-32P]ATP (∼240 c.p.m. pmol−1) and 1 μl column fraction in a total volume of 30 μl. Reaction time was 1.25 min (+Ca2+) or 30 min (+EGTA) at a temperature of 30°C. 32P incorporation into myosin was quantified by the P81 paper assay (see above). Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity eluted in fractions 46-64 and MLCK in fractions 40-80. Fractions 46-64 were pooled, concentrated ∼2-fold by dialysis against Aquacide II (MW 500 000; Calbiochem) and dialysed against 2 × 2 l of Buffer D (mM: 20 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 EGTA, 5 MgCl2, 1 DTT and 0.2 M NaCl). The dialysate was adjusted to 1 mM free CaCl2 and applied to a column (1 cm × 13 cm) of CaM-Affi-Gel, prepared according to the Affi-Gel 15 manufacturer's instructions and previously equilibrated with Buffer E (mM: 20 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 MgCl2, 1 DTT, 1 CaCl2 and 0.2 M NaCl). Unbound proteins were washed off the column with Buffer E and proteins bound in a Ca2+-dependent manner were eluted with Buffer F (mM: 20 Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 MgCl2, 1 DTT, 10 EGTA and 0.2 M NaCl) at a flow rate of 30 ml h−1 collecting 1 ml fractions. Fractions containing Ca2+ were adjusted to 10 mM EGTA to inactivate any Ca2+-activated protease. Fractions were assayed for their ability to phosphorylate myosin in the presence of Ca2+ as described above for the Q-Sepharose column chromatography using 3 μl of column fractions per 30 μl reaction mixture. Assay mixtures in the absence of Ca2+ (containing 3 μl of column fraction per 30 μl reaction volume) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography; in this case, reactions were stopped after 30 min by addition of SDS gel sample buffer and boiling, and LC20 phosphorylation was quantified by cutting the LC20 band (identified by autoradiography) from the gel and Cerenkov counting. It was necessary to use this gel method to quantify LC20 phosphorylation in the absence of Ca2+ since significant levels of phosphorylation of other proteins occurred under these conditions (see Fig. 18); in the presence of Ca2+, only LC20 phosphorylation occurred.

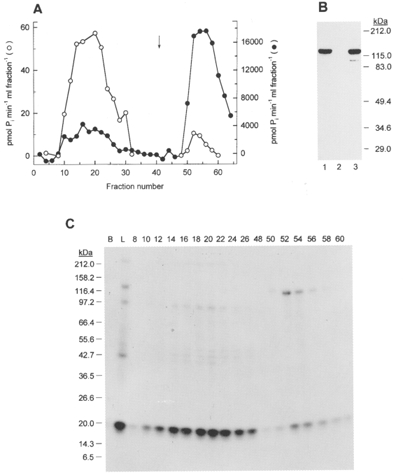

Figure 18. Separation of MLCK and Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase by CaM affinity chromatography.

A, the 2 M NaCl extract of chicken gizzard myofilaments (E2) was subjected to CaM affinity chromatography following partial purification by Q-Sepharose anion-exchange chromatography as described in Methods. Proteins bound in the presence of Ca2+ were eluted from the affinity column by application of EGTA-containing buffer (indicated by the arrow). Fractions were assayed for their ability to phosphorylate myosin in the absence (○) and presence of Ca2+ (•). B, Western blot with anti-MLCK of 10 μl of the column load (lane 1), the pooled flow-through fractions (lane 2) and the pooled EGTA eluate (lane 3). C, autoradiograph of reaction mixtures assayed in the absence of Ca2+ (see A) and subjected to SDS-PAGE. B, blank (no column fraction); L, column load; fractions indicated by number. The sizes of Mr marker proteins are shown on the left in kDa.

Protein concentration determinations

Chicken gizzard myofilament protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce). PKC concentration was determined by quantitative amino acid analysis in the Protein Sequencing Core Facility at the University of Calgary, Canada. Other proteins were quantified using the following values for the absorbance of a 1 % solution with a path length of 1 cm: myosin, 4.5 at 280 nm; CaM, 1.95 at 277 nm; MLCK, 11.4 at 280 nm; LC20, 3.37 at 280 nm.

Materials

[γ-32P]ATP (> 5000 Ci mmol−1) was purchased from Amersham. Microcystin-LR from Microcystis aeruginosa, staurosporine, chelerythrine, HA 1077 (1-(5-isoquinolinesulphonyl)-homopiperazine), ML-9 (1-(5-chloronaphthalene-1-sulphonyl)-1H-hexahydro-1,4-diazepine), wortmannin and calphostin C were purchased from Calbiochem. Affi-Gel 15 was purchased from Bio-Rad. Triton X-100 (peroxide-free) was purchased from Boehringer-Mannheim and deionized over AG501-X8 resin (BDH). Hepes, Mops, Tes and PMSF were purchased from Sigma. L-α-Phosphatidylserine and 1,2-diolein were purchased from Serdary Research Laboratories (London, Canada). Tween-20 (polyoxyethylene sorbitan mono-oleate) was purchased from Bio-Rad and Tween-80 (polyoxyethylene sorbitan monolaurate) from Fisher. TPCK-trypsin was purchased from United States Biochemical Corp. (Cleveland, OH, USA), leupeptin, pepstatin A and DTT from ICN Biomedicals, Inc. (Aurora, OH, USA) and soybean trypsin inhibitor from Amersham. Relative molecular mass (Mr) marker proteins (myosin 212 kDa, MBP-β-galactosidase 158.2 kDa, β-galactosidase 116.4 kDa, phosphorylase b 97.2 kDa, bovine serum albumin 66.4 kDa, glutamic dehydrogenase 55.6 kDa, MBP2 42.7 kDa, lactate dehydrogenase 36.5 kDa, triosephosphate isomerase 26.6 kDa, soybean trypsin inhibitor 20 kDa, lysozyme 14.3 kDa, aprotinin 6.5 kDa, insulin B chain 3.4 kDa) were purchased from New England Biolabs and prestained Mr marker proteins (myosin 203 kDa, β-galactosidase 115 kDa, bovine serum albumin 83 kDa, ovalbumin 49.4 kDa, carbonic anhydrase 34.6 kDa, soybean trypsin inhibitor 29 kDa, lysozyme 20.4 kDa, aprotinin 7 kDa) from Bio-Rad. MLCK inhibitor peptides SM-1 (AKKLSKDRMKKYMARRKWQKTG) and AV25 (AKKLAKDRMKKYMARRKLQKAGHAV) and MLCK substrate peptide MLC11-23 (KKRPQRATSNVFA) were synthesized in the Peptide Synthesis Core Facility at the University of Calgary. The purity of the peptides (> 95 %) was confirmed by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography and amino acid analysis. [Ala9]autocamtide 2, a peptide inhibitor of CaM kinase II (KKALRRQEAVDAL), was purchased from American Peptide Co. (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). All other reagents were analytical grade or better and were purchased from VWR Canlab (Edmonton, Canada) or Sigma. The following proteins were purified as described previously: chicken gizzard myosin II (Persechini & Hartshorne, 1981), MLCK (Ngai et al. 1984), Ca2+-CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaM kinase II) with caldesmon (Scott-Woo & Walsh, 1988) and CaM (Walsh et al. 1984), and rat brain protein kinase C (PKC; a mixture of Ca2+-dependent α, β and γ isoforms) (Allen et al. 1994). LC20 was prepared from purified myosin isolated from 200 g of chicken gizzard using a modification of the procedure of Hathaway & Haeberle (1983).

Statistics

Where applicable, values are presented as means ±s.e.m. Data were compared by Student's t test. A level of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. n indicates the number of experiments.

RESULTS

Ca2+-independent contraction of demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle

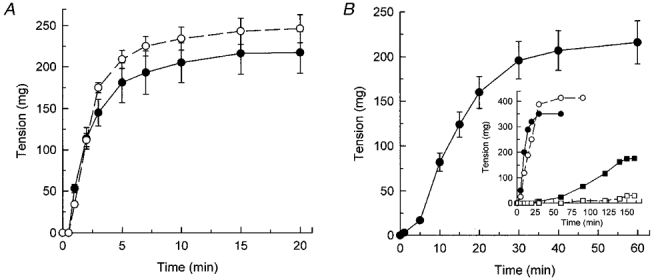

Figure 1 compares the contractile responses of Triton X-100-demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips to pCa 6 and 4.5 (Fig. 1A) and the phosphatase inhibitor microcystin at pCa 9 (Fig. 1B). Comparable steady-state levels of tension were achieved in each case: 246 ± 17 mg (n = 5) at pCa 6, 217 ± 25 mg (n = 5) at pCa 4.5 and 221 ± 21 mg (n = 7) at pCa 9 with microcystin. These values are similar to that of a maximal K+-induced contraction of the same muscle strips before demembranating (255 ± 26 mg, n = 7). The contractile response to microcystin was significantly slower, however: the time to half-maximal tension was 1.9 ± 0.2 min (n = 5) for pCa 6-induced contraction, 1.3 ± 0.1 min (n = 5) for pCa 4.5-induced contraction and 12.8 ± 0.7 min (n = 7) for microcystin-induced contraction. The time to half-maximal contraction of intact strips in response to 117 mM KCl was 0.12 ± 0.01 min (n = 6). Addition of pCa 4.5 at the plateau of a microcystin-induced contraction at pCa 9 caused only a slight further increase in tension (results not shown). The inset in Fig. 1B shows the dependence of contraction at pCa 9 on the concentration of microcystin. Subsequent experiments were carried out at 1 or 10 μM microcystin. Following microcystin-induced contraction at pCa 9, the muscle did not relax upon return to pCa 9 solution without microcystin (results not shown), consistent with the fact that microcystin binds covalently to the catalytic subunit of PP1M causing irreversible inhibition of the phosphatase (Mackintosh et al. 1995).

Figure 1. Ca2+-dependent and -independent contraction of demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle.

Triton X-100-demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips were stimulated to contract at time zero by increasing the free [Ca2+] to 1 μM (pCa 6) (○) or 30 μM (pCa 4.5) (•) (A) or by addition of 10 μM microcystin at pCa 9 (•) (B). Tension was recorded until steady-state levels were attained. B, inset: the contractile response at pCa 9 to 0.01 (□), 0.1 (▪), 1 (○) and 10 μM microcystin (•).

The MLCK-selective inhibitors ML-9 and wortmannin, and the PKC-selective inhibitors chelerythrine and calphostin C had no significant effect (P > 0.05) on the contractile response of demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips to 10 μM microcystin at pCa 9: steady-state tension (mean ±s.d.) in response to microcystin at pCa 9 was 207.2 ± 43.2 mg (n = 6) under control conditions, 160.3 ± 34.4 mg (n = 6) in the presence of ML-9 (300 μM), 155.8 ± 30.8 mg (n = 6) in the presence of wortmannin (10 μM), 186.4 ± 53.6 mg (n = 7) in the presence of chelerythrine (10 μM) and 210.8 ± 22.9 mg (n = 5) in the presence of calphostin C (1 μM).

Correlation between Ca2+-independent, microcystin-induced contraction and LC20 phosphorylation

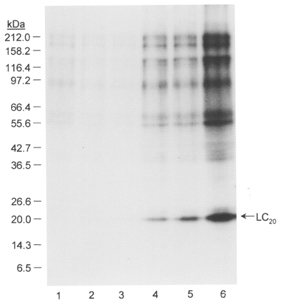

The profile of protein phosphorylation in response to microcystin treatment was investigated using [γ-32P]ATP. Triton X-100-demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips, incubated with [γ-32P]ATP, were treated with 1 μM microcystin at pCa 9 for 60 min, i.e. until maximal tension was attained. Control muscle strips were incubated for 60 min under identical conditions without microcystin. Muscle strips were then quick-frozen, proteins separated by SDS-PAGE and phosphorylated proteins detected by autoradiography. Figure 2 (lanes 2 and 3) shows the resultant Coomassie Blue-stained gel, indicating that comparable amounts of protein from control (lane 2) and microcystin-treated tissue (lane 3) were applied to the gel. The corresponding autoradiogram (Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 5) reveals low levels of phosphorylation of several proteins in the size range of 40-200 kDa in the control muscle strips incubated at pCa 9 (lane 4). In microcystin-treated muscle strips (lane 5), the level of phosphorylation of all these proteins was increased, but most striking was the appearance of a major phosphoprotein of 20 kDa, which was phosphorylated to a stoichiometry of 0.76 ± 0.05 mol Pi mol−1 (n = 7). This phosphoprotein co-migrates with the 20 kDa light chain of myosin which is known to be phosphorylated at pCa 6 (compare lanes 2 and 3 in Fig. 3A). Its identity was confirmed with the aid of antibodies to LC20 (Fig. 3B). Given the specificity of these antibodies for LC20 phosphorylated at serine-19 and at both serine-19 and threonine-18 (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 2, respectively), these results also indicate that Ca2+-independent, microcystin-induced contraction involves LC20 phosphorylation at both serine-19 and threonine-18.

Figure 2. Ca2+-independent LC20 phosphorylation in demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle.

Triton X-100-demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips were incubated for 60 min with [γ-32P]ATP at pCa 9 without (lanes 2 and 4) or with (lanes 3 and 5) 1 μM microcystin. Tissue strips were processed for SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as described in Methods. Lanes 1-3: Coomassie Blue-stained gels of Mr marker proteins, control muscle strip and muscle strip treated with microcystin, respectively. Lanes 4 and 5: autoradiogram showing phosphoproteins in control and microcystin-treated muscle strips, respectively. The sizes of Mr markers are shown on the left in kDa. The position of LC20 is indicated at the right. Results are representative of five similar experiments. From densitometric scanning of the actin bands in lanes 2 and 3, similar amounts of tissue protein were loaded: (optical density × mm2) values for the actin band were 34.7 and 38.1 in lanes 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 3. Identification of the 20 kDa phosphoprotein as LC20.

Triton X-100-demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips were incubated for 60 min with [γ-32P]ATP at pCa 9 (A, lane 1), pCa 6 (A, lane 2) or pCa 9 + microcystin (A, lane 3 and B, lanes 1 and 2) and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. A, phosphoproteins were detected by autoradiography. B, Western blots of a tissue sample identical to that in lane 3 (A) using antibody pLC1 that specifically recognizes LC20 phosphorylated at serine-19 (lane 1) or antibody pLC2 that specifically recognizes LC20 phosphorylated at both serine-19 and threonine-18 (lane 2).

The time course of LC20 phosphorylation in response to microcystin treatment at pCa 9 is shown in Fig. 4. There was a good correlation between LC20 phosphorylation and tension development (cf. Fig. 1B). The most likely explanation for the Ca2+-independent, microcystin-induced contraction, therefore, is that inhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase by microcystin unmasks a kinase activity that catalyses phosphorylation of the 20 kDa light chain of myosin at serine-19 and threonine-18, triggering contraction. We verified that microcystin (10 μM) has no effect on the activity of purified MLCK (results not shown).

Figure 4. Time course of LC20 phosphorylation in response to microcystin treatment at pCa 9.

Triton X-100-demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips were incubated for 0-40 min with [γ-32P]ATP in pCa 9 solution containing 1 μM microcystin. LC20 phosphorylation was analysed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Incubation times were: 0 (lane 1), 2 min (lane 2), 5 min (lane 3), 10 min (lane 4), 20 min (lane 5) and 40 min (lane 6). The sizes of Mr markers are shown on the left in kDa.

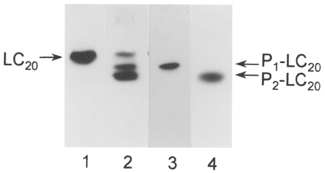

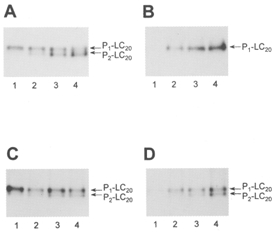

To confirm the sites of phosphorylation in LC20, demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips treated with microcystin at pCa 9 were subjected to urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis which separates unphosphorylated and phosphorylated forms of the light chain. Following transfer to nitrocellulose, LC20 was detected with antibodies that recognize: (1) all species (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) of LC20 (general LC20 antibody); (2) LC20 phosphorylated at serine-19 (antibody pLC1); and (3) LC20 phosphorylated at both serine-19 and threonine-18 (antibody pLC2). As shown in Fig. 5, the general LC20 antibody recognized a single band in control tissue incubated at pCa 9 without microcystin (lane 1), but three bands following treatment of the demembranated muscle strips with microcystin (lane 2). The slowest-migrating band corresponded to unphosphorylated LC20 (lane 2), which is the exclusive LC20 species detected in control muscle strips (lane 1). The middle band corresponded to LC20 phosphorylated exclusively at serine-19 (lane 3) and the fastest-migrating band to LC20 phosphorylated at both serine-19 and threonine-18 (lane 4). Ca2+-independent, microcystin-induced contraction, therefore, correlated with LC20 phosphorylation at serine-19 and threonine-18.

Figure 5. Ca2+-independent LC20 phosphorylation in response to microcystin treatment occurs at serine-19 and threonine-18.

Triton X-100-demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips were incubated for 60 min at pCa 9 (lane 1) or pCa 9 with 10 μM microcystin (lanes 2-4). Unphosphorylated (LC20) and phosphorylated forms of LC20 (P1-LC20 and P2-LC20) were separated by urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis and identified by Western blotting using a general antibody to LC20 (lanes 1 and 2) or antibodies specific for LC20 phosphorylated exclusively at serine-19 (pLC1; lane 3) or both serine-19 and threonine-18 (pLC2; lane 4). Samples of 30 μl were applied per lane.

Is the kinase responsible for Ca2+-independent phosphorylation of LC20 myosin light chain kinase itself?

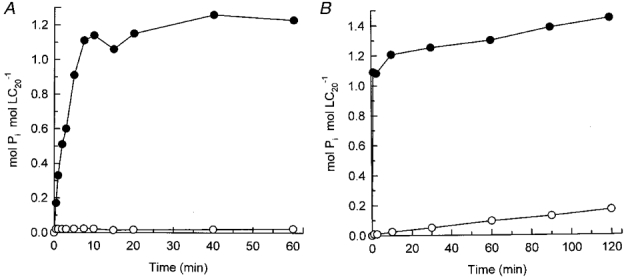

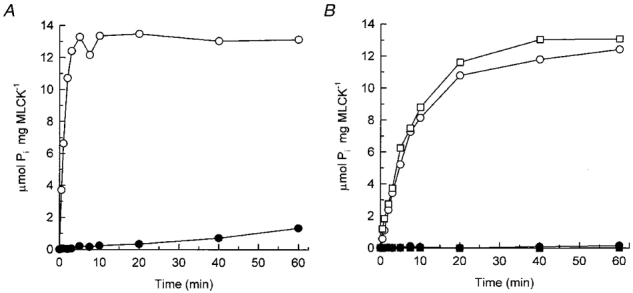

This would require that MLCKs have a significant level of activity in the absence of Ca2+. However, we found this not to be the case. MLCK is essentially inactive in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 6A) unless assayed at high concentrations (Fig. 6B). From the initial rates of phosphorylation in the presence of Ca2+ at 0.25 μg ml−1 MLCK (Fig. 6A) and in the absence of Ca2+ at 10 μg ml−1 MLCK (Fig. 6B), we calculated that the Ca2+-independent specific activity was equivalent to only 0.0015 % of maximal Ca2+-activated MLCK specific activity. At a 10-fold higher MLCK concentration (0.1 mg ml−1), close to the in vivo concentration of MLCK (3-4 μM), the Ca2+-independent specific activity was 3-fold lower, at 0.0005 % of maximal Ca2+-activated MLCK specific activity. This low Ca2+-independent activity in fact correlates with autophosphorylation of MLCK that occurs only in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 7). This is in agreement with the results of Tokui et al. (1995) who showed that autophosphorylation at threonine-803 (within the autoinhibitory domain of MLCK) elicited constitutive activity.

Figure 6. Myosin light chain kinase is inactive in the absence of Ca2+.

Purified MLCK was incubated in the absence (○) and presence of Ca2+ (•) at a kinase concentration of 0.25 μg ml−1 (A) or 10 μg ml−1 (B), using LC20 (0.2 mg ml−1) as substrate. Samples (20 μl) of reaction mixtures were spotted onto P81 phosphocellulose paper at the indicated times for quantification of LC20 phosphorylation.

Figure 7. Autophosphorylation of MLCK correlates with LC20 phosphorylation in the absence of Ca2+.

A, correlation between MLCK autophosphorylation (○) and Ca2+-independent phosphorylation of isolated LC20 at 15 μg ml−1 (•). B, correlation between MLCK autophosphorylation (○) and Ca2+-independent phosphorylation of intact myosin at 0.15 mg ml−1 (•). Assays were carried out at 10 μg ml−1 MLCK in the absence of Ca2+. Insets: autoradiographs of reaction mixtures in the presence of Ca2+ (lanes 1) or absence of Ca2+ (lanes 2) after 120 min. A, isolated LC20 substrate; B, intact myosin substrate. Note that autophosphorylation of MLCK occurs only in the absence of Ca2+ (compare lanes 1 and 2 in each panel).

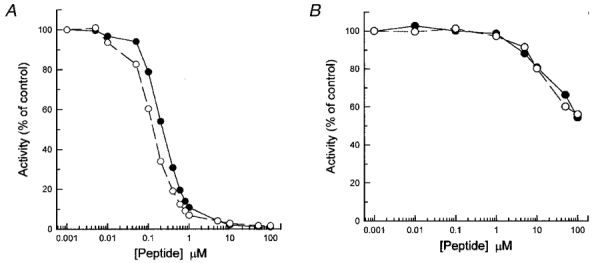

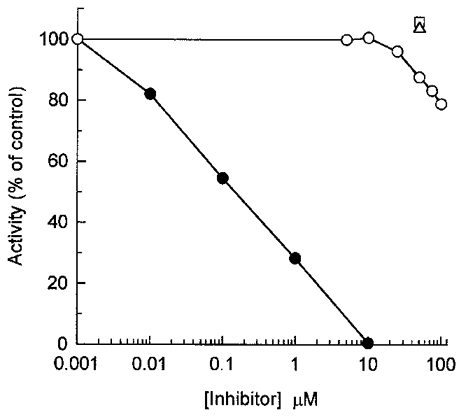

To address the relationship of the Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity to MLCK more directly, we compared the effects of AV25, a synthetic peptide inhibitor of MLCK based on the autoinhibitory domain of the kinase, on Ca2+- and microcystin-induced contractions of demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips. It was necessary first, however, to characterize the inhibition of MLCK by this peptide. AV25 (denoting the first and last residues and the length of the peptide) has the sequence AKKLAKDRMKKYMARRKLQKAGHAV and corresponds to residues 783-807 of chicken gizzard MLCK with three substitutions (in bold): tryptophan-800 was replaced by leucine to effectively eliminate interaction of the peptide with CaM; and serine-787 and threonine-803 were replaced by alanine to avoid confusion due to peptide phosphorylation, since we found in preliminary experiments that these sites were phosphorylated by CaM kinase II when the peptide was added to chicken gizzard myofilaments (results not shown). These modifications did not significantly alter the potency of inhibition of MLCK (Fig. 8A): the IC50 for the parent peptide, SM-1, was 0.1 μM and for AV25 it was 0.2 μM. Interestingly, the constitutive activity of autophosphorylated MLCK was much more resistant to inhibition by SM-1 and AV25: at 75 μM peptide, only 40 % inhibition of the Ca2+-independent activity of autophosphorylated MLCK was observed (Fig. 8B). Autoradiography showed that autophosphorylation of MLCK was unaffected by SM-1 or AV25 (Fig. 9).

Figure 8. Inhibition of MLCK by synthetic peptides based on the autoinhibitory domain.

MLCK (10 μg ml−1) was incubated with the indicated concentrations of SM-1 (○) or AV25 (•) in the presence (A) or absence (B) of Ca2+. At 5 min (A) or 2 h (B,) samples (20 μl) of reaction mixtures were spotted onto P81 phosphocellulose paper for quantification of substrate (0.1 mM MLC11-23) phosphorylation. Activities are expressed as a percentage of the activity in the absence of peptide inhibitors (65.2 mol Pi min−1 (mol MLCK)−1 in the presence of Ca2+ and 0.21 mol Pi min−1 (mol MLCK)−1 in the absence of Ca2+).

Figure 9. Lack of effect of SM-1 or AV25 on MLCK autophosphorylation.

MLCK (10 μg ml−1) was incubated for 2 h under phosphorylating conditions with LC20 (0.1 mg ml−1) and various concentrations of SM-1 or AV25 in the absence of Ca2+. Samples (30 μl) of reaction mixtures were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. A, Coomassie Blue-stained gel; B, autoradiograph. Lane 1: Mr marker proteins; lanes 2-6: 0, 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 μM SM-1, respectively; lanes 7-10: 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 μM AV25, respectively. Scintillation counting of MLCK bands indicated no effect of SM-1 or AV25 on autophosphorylation. Scintillation counting of LC20 bands indicated 42 % inhibition of phosphorylation at 100 μM SM-1 and 49 % inhibition at 100 μM AV25.

As shown in Table 1, AV25 (75 μM) caused a marked inhibition of tension and LC20 phosphorylation in demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips stimulated at pCa 6, but had no significant effect on force or LC20 mono- or diphosphorylation induced by microcystin at pCa 9.

Table 1.

Effects of AV25 on tension and myosin phosphorylation induced in demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips by pCa 6 or pCa 9 + microcystin

| Conditions | n | Tension (mg) | t1/2 (min) | P1-LC20 (%) | P2-LC20 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pCa 6 | 5 | 246 ± 17 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 19.4 ± 5.2 | 2.8 ± 1.5 |

| pCa 6 + AV25 | 4 | 32 ± 5* | 9.0 ± 1.6* | 5.0 ± 0.9* | 0.8 ± 0.5* |

| pCa 9 + microcystin | 7 | 221 ± 21 | 12.8 ± 0.7 | 27.9 ± 1.3 | 48.1 ± 4.8 |

| pCa 9 + microcystin + AV25 | 7 | 180 ± 28 | 12.4 ± 1.8 | 22.1 ± 4.4 | 52.9 ± 6.7 |

Tension, maximal tension achieved at steady-state; t1/2, time to half-maximal tension; P1-LC20, monophosphorylated LC20 as a percentage of total LC20;P2-LC20, diphosphorylated LC20 as a percentage of total LC20. Values represent means ± S.E.M.

Significantly different from corresponding response in the absence of AV25 (P < 0.05; Student's t test).

The possibility that Ca2+-independent, microcystin-induced LC20 phosphorylation and contraction may be due to a small amount of constitutively active MLCK, generated by partial proteolysis of MLCK in the demembranated muscle strips, was also investigated. The 61 kDa constitutively active fragment of MLCK was generated by trypsin digestion. As shown in Fig. 10, the constitutively active MLCK (Fig. 10B), like the intact, Ca2+-CaM-activated enzyme (Fig. 10A), was inhibited by AV25, and inhibition of the constitutively active kinase was complete in the absence as well as in the presence of Ca2+.

Figure 10. Effect of AV25 on intact and constitutively active MLCK.

A, the activity of intact MLCK (5 μg ml−1; 47 nM) was assayed in the presence of Ca2+ without (○) or with 75 μM AV25 (•). B, the activity of constitutively active (trypsin-digested) MLCK (47 nM) was assayed in the absence (□, ▪) and presence of Ca2+ (○, •) without (○, □) or with 75 μM AV25 (•, ▪). LC20 (0.1 mg ml−1) was used as substrate.

We conclude, therefore, that the kinase responsible for Ca2+-independent, microcystin-induced LC20 phosphorylation and contraction is neither intact (unphosphorylated or autophosphorylated) MLCK nor a constitutively active, proteolytic fragment of MLCK.

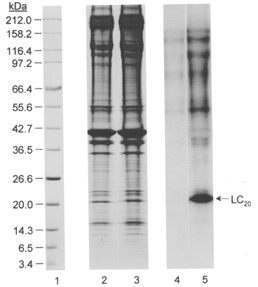

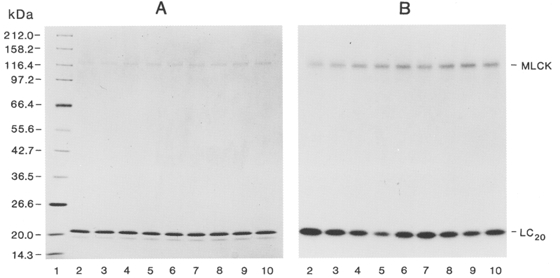

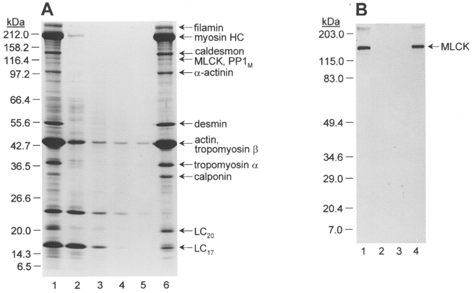

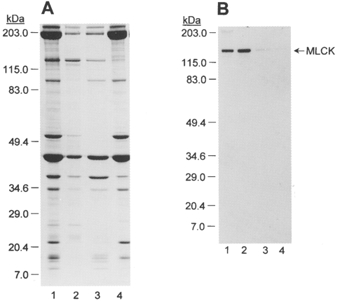

To further investigate the relationship between MLCK and the Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase, we turned to chicken gizzard smooth muscle, which has been widely used for biochemical studies of the regulation of smooth muscle contraction due to its ready availability in large quantities. We reasoned that the Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase, like MLCK, is likely to be associated with the contractile machinery and therefore should be retained in myofilament preparations. The preparation of choice for these studies, therefore, was a myofilament preparation obtained by homogenization of the tissue, followed by removal of cytosolic proteins by centrifugation and of membrane proteins by extensive washing of the particulate fraction with buffer containing Triton X-100. The preparation of myofilaments is shown in Fig. 11A. The major protein components were identified with antibodies and consist of contractile and regulatory proteins (actin, myosin, tropomyosin, calponin, caldesmon, MLCK, PP1M) and cytoskeletal proteins (filamin, α-actinin and desmin). The identification of MLCK is shown by Western blotting (Fig. 11B); the kinase is quantitatively retained in the myofilaments due to its physical association with the thin filaments (Lin et al. 1997).

Figure 11. Preparation of chicken gizzard myofilaments.

A, chicken gizzard myofilaments were prepared as described in Methods. Samples (3 μl each) of fractions obtained during the preparation were analysed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. Lane 1, chicken gizzard homogenate; lane 2, supernatant after first centrifugation; lane 3, first wash of pellet; lane 4, second wash of pellet; lane 5, third wash of pellet; lane 6, myofilaments. The sizes of Mr markers are indicated on the left in kDa. The major proteins in the myofilament preparation are identified at the right. B, Western blot with anti-MLCK. Lane 1, chicken gizzard homogenate; lane 2, supernatant after first centrifugation; lane 3, first wash of pellet; lane 4, myofilaments. The sizes of prestained Mr markers are shown on the left in kDa.

We compared the endogenous Ca2+-dependent and -independent LC20 kinase activities in the chicken gizzard myofilaments and the effect of microcystin on these activities. The time course of LC20 phosphorylation was quantified following SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as described in Methods (Fig. 12A-C). In the presence of Ca2+ and microcystin, LC20 was phosphorylated to 1.0 mol Pi (mol LC20)−1 within 2.5 min, with an additional increase to 1.3 mol Pi (mol LC20)−1 after 2 h (Fig. 12A). In the absence of microcystin, only submaximal levels of phosphorylation were achieved (Fig. 12A), indicating a high level of competing phosphatase activity in the myofilaments. In the absence of Ca2+, LC20 was slowly phosphorylated over 2 h to a stoichiometry of 0.25 mol Pi (mol LC20)−1 in the presence of microcystin (Fig. 12B). As with Ca2+, the stoichiometry was reduced in the absence of microcystin. In both the absence and presence of Ca2+, LC20 was the major phosphoprotein (Fig. 12C). In the absence of Ca2+, phosphorylation of a 130 kDa protein was also clearly detected. This phosphoprotein presumably corresponds to autophosphorylated MLCK as it co-migrates with purified autophosphorylated MLCK on SDS-PAGE. The time courses of phosphorylation of the 130 kDa protein and LC20 were similar (results not shown).

Figure 12. Identification of Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity in chicken gizzard myofilaments.

Myosin phosphorylation in chicken gizzard myofilaments was quantified following SDS-PAGE and autoradiography of reaction mixtures in the presence of Ca2+ (A) or EGTA (B). The stoichiometry of LC20 phosphorylation was determined by cutting the radiolabelled LC20 band out of the gel and scintillation counting. LC20 phosphorylated to exactly 1.0 mol Pi (mol LC20)−1 was used as a reference to calculate the stoichiometry of LC20 phosphorylation. Reactions were carried out in the absence (○) or presence of 10 μM microcystin (•). C, SDS-PAGE and autoradiography of the reaction mixtures containing microcystin and either Ca2+ (2.5 min) (lanes 1 and 3) or EGTA (120 min) (lanes 2 and 4). Lanes 1 and 2, Coomassie Blue-stained gels; lanes 3 and 4, autoradiographs. D, urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis and Western blotting with the general LC20 antibody (a), pLC1 (b) or pLC2 (c). Lane 1, untreated myofilaments; lanes 2 and 3, incubated with Ca2+ and microcystin for 5 and 120 min, respectively; lanes 4 and 5, incubated with EGTA and microcystin for 30 and 120 min, respectively.

The phosphorylation patterns of myofilament LC20 in the absence and presence of Ca2+ were also examined by urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis and Western blotting with the general LC20 antibody, and antibodies pLC1 and pLC2 (Fig. 12D). In the presence of Ca2+, LC20 was entirely monophosphorylated within 5 min, with additional diphosphorylation occurring with longer reaction times. In the absence of Ca2+, both mono- and diphosphorylation were detected within 2 h. In all cases, the monophosphorylated band was recognized by the serine-19-specific antibody (pLC1) and the diphosphorylated band by the serine-19/threonine-18-specific antibody (pLC2).

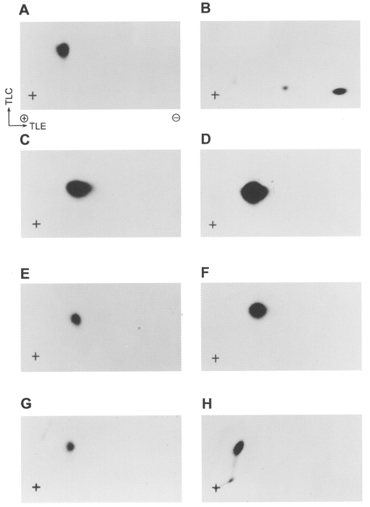

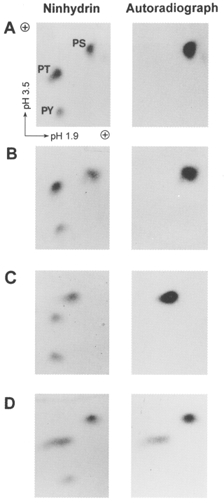

The phosphorylation patterns of LC20 in the myofilaments were also examined by autoradiography following urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis and compared with isolated LC20 phosphorylated by purified MLCK at the same concentration as in the myofilament assay (10 μg ml−1) (Fig. 13). Phosphorylation of isolated LC20 in the absence of Ca2+ (due to autophosphorylated MLCK; see above) occurred at a single site (Fig. 13B), whereas phosphorylation of myofilament LC20 by endogenous Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase occurred at two sites (Fig. 13D). For comparison, Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation of isolated LC20 by MLCK and of myofilament LC20 by endogenous MLCK occurred at two sites in each case (Fig. 13A and C, respectively). Figure 14 shows that a phosphopeptide of the same mobility is generated following digestion of all P1-LC20 species observed in Fig. 13 (Fig. 14A, C, E and G). This peptide (17ATSNVFAMFDQSQIQEFK34) contains serine-19 and threonine-18 (Colburn et al. 1988) and has a very distinct mobility from peptides phosphorylated at PKC sites (serine-1, serine-2 and threonine-9) (Fig. 14B). Co-migration of phosphopeptides was confirmed in mixing experiments (Fig. 14D, F and H). Phosphoamino acid analysis of the phosphopeptides in Fig. 14A, C, E and G indicated that P1-LC20, produced by phosphorylation of isolated LC20 by MLCK in the absence or presence of Ca2+ or by phosphorylation of myofilament LC20 by endogenous MLCK in the presence of Ca2+, contained exclusively phosphoserine (Fig. 15A-C). Serine-19, is, therefore, the sole site of phosphorylation in these examples. Most interestingly, P1-LC20 produced by phosphorylation of myofilament LC20 by endogenous kinase activity in the absence of Ca2+ contained both phosphoserine and phosphothreonine (Fig. 15D). In this case, therefore, P1-LC20 must consist of a mixture of LC20 phosphorylated only at serine-19 or only at threonine-18. The Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase, therefore, can phosphorylate LC20 at either serine-19 or threonine-18 or at both sites. MLCK, on the other hand, cannot phosphorylate LC20 at threonine-18 without prior phosphorylation at serine-19.

Figure 13. Ca2+-dependent and -independent phosphorylation of isolated LC20 by MLCK and of myofilament LC20 by endogenous kinases.

Time courses of LC20 phosphorylation were analysed by urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis and autoradiography: A, phosphorylation of isolated LC20 by MLCK in the presence of Ca2+; B, phosphorylation of isolated LC20 by MLCK in the absence of Ca2+; C, phosphorylation of LC20 in myofilaments by endogenous MLCK in the presence of Ca2+; D, phosphorylation of LC20 in myofilaments by endogenous Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase in the absence of Ca2+. Lane 1, 5 min; lane 2, 30 min; lane 3, 60 min; lane 4, 120 min. Exposure times were varied to give similar signal intensities.

Figure 14. Phosphopeptide mapping of isolated LC20 phosphorylated by MLCK and of myofilament P1-LC20 phosphorylated by endogenous kinases.

P1-LC20, separated by urea/glycerol gel electrophoresis, was digested with TPCK-trypsin in the gel slice and peptides were separated by two-dimensional thin-layer electrophoresis/chromatography. Phosphopeptides were identified by autoradiography. A, isolated LC20 phosphorylated by MLCK in the presence of Ca2+ (see P1-LC20 in Fig. 13A). B, isolated LC20 phosphorylated by PKC; C, isolated LC20 phosphorylated by MLCK in the absence of Ca2+ (see P1-LC20 in Fig. 13B). D, a mixture of A and C.E, myofilament LC20 phosphorylated in the presence of Ca2+ (see P1-LC20 in Fig. 13C). F, a mixture of A and E.G, myofilament LC20 phosphorylated in the absence of Ca2+ (see P1-LC20 in Fig. 13D). H, a mixture of A and G. Exposure times were longer than in the experiment of Fig. 13 to obtain clear signals.

Figure 15. Phosphoamino acid analysis of LC20 phosphopeptides.

The phosphopeptides from Fig. 14 were hydrolysed to their constituent amino acids and phosphoserine (PS), phosphothreonine (PT) and phosphotyrosine (PY) were separated by two-dimensional electrophoresis. Added unlabelled phosphoamino acid standards were detected by ninhydrin staining (left panels) and radiolabelled phosphoamino acids derived from phosphorylated LC20 were detected by autoradiography (right panels). A, isolated LC20 phosphorylated by MLCK in the presence of Ca2+ (see P1-LC20 in Fig. 13A);B, isolated LC20 phosphorylated by MLCK in the absence of Ca2+ (see P1-LC20 in Fig. 13B); C, myofilament LC20 phosphorylated in the presence of Ca2+ (see P1-LC20 in Fig. 13C); D, myofilament LC20 phosphorylated in the absence of Ca2+ (see P1-LC20 in Fig. 13D).

Ca2+-independent phosphorylation of myofilament LC20 by endogenous Ca2+-independent kinase was resistant to inhibition by AV25 and [Ala9]autocamtide 2 (a CaM kinase II inhibitor peptide) but was completely inhibited by the non-specific kinase inhibitor staurosporine (Fig. 16). We verified that [Ala9]autocamtide 2 (0.05 μM) completely inhibited the phosphorylation of caldesmon by CaM kinase II. Staurosporine (10 μM) also blocked contraction of demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle induced by microcystin at pCa 9. Myofilament-associated Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity was unaffected by the PKC-selective inhibitor chelerythrine (10 or 50 μM) or the Rho-associated kinase-selective inhibitor HA 1077 (30 μM) (results not shown).

Figure 16. Effect of kinase inhibitors on Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity in myofilaments.

Myofilament Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity was assayed in the absence of Ca2+ for 120 min at the indicated concentrations of staurosporine (•), AV25 (○) or [Ala9]autocamtide 2, either alone (□) or with 50 μM AV25 (▵).

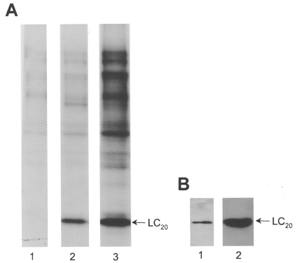

Different extraction conditions were used to separate myofilament-associated MLCK from the Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase. Treatment of the myofilaments with 30 mM Mg2+ extracted ∼90 % of the MLCK (Table 2 and Fig. 17) but left most (∼70 %) of the Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase associated with the myofilaments (Table 2). This Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase could then be extracted with 2 M NaCl. The extracted Ca2+-CaM-activated MLCK was completely inhibited by AV25 (50 μM), but the extracted Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase was unaffected by this peptide (Table 2). The extracted Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase contained ∼10 % of total MLCK (Fig. 17B, lane 3 and Table 2), which could be separated by CaM affinity chromatography (Fig. 18). Most of the Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity did not bind to the affinity column (Fig. 18A) and was devoid of MLCK, as shown by Western blotting (Fig. 18B, lane 2). MLCK, on the other hand, bound to the affinity column and was eluted by chelation of Ca2+ with EGTA (Fig. 18A and B, lane 3). As shown by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography of reaction mixtures from Fig. 18A incubated in the absence of Ca2+, the low level of Ca2+-independent LC20 phosphorylation associated with MLCK (fractions 50-56) was due to autophosphorylated MLCK (Fig. 18C).

Table 2.

Effects of AV25 on myosin phosphorylation by extracts of chicken gizzard myofilaments

| LC20 kinase activity (nmol P1 min−1 (ml extract)−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +Ca2+ | +EGTA | |||

| Extract | −AV25 | +AV25 | −AV25 | +AV25 |

| E1 | 819.4 | 0 | 0.0524 | 0.0492 |

| E2 | 96.9 | 0 | 0.113 | 0.118 |

Figure 17. Extraction of MLCK and Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase from myofilaments under different conditions.

A, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE of chicken gizzard myofilaments (lane 1), the 30 mM Mg2+ extract (E1; lane 2), the 2 M NaCl extract (E2; lane 3) and the final pellet after the two extractions (lane 4). Loading level, 3 μl of protein sample per lane. Prestained Mr markers are indicated on the left. B, Western blot with anti-MLCK. Lanes 1-4 as in A. Prestained Mr markers are again indicated on the left.

DISCUSSION

A great deal of attention has been devoted recently to the mechanisms underlying smooth muscle contraction that do not involve an increase in [Ca2+]i and activation of MLCK, i.e. Ca2+ sensitization (the signal transduction pathways that elicit a contractile response without a change in [Ca2+]i) and Ca2+-independent contraction. In several instances, these mechanisms involve inhibition of PP1M and an increase in myosin LC20 phosphorylation. Since the level of myosin phosphorylation is dictated by the kinase : phosphatase activity ratio, this implies that inhibition of the phosphatase unmasks kinase activity resulting in phosphorylation of LC20 at serine-19. While it has been generally assumed that the Ca2+-independent activity is due to basal activity of MLCK itself, there is little direct evidence to support this hypothesis. Suzuki & Itoh (1993) showed that the phosphatase inhibitor calyculin A induced Ca2+-independent contraction of β-escin-permeabilized rabbit mesenteric artery and demonstrated mono- and diphosphorylation of LC20. SM-1 and ML-9 (MLCK inhibitors) inhibited both calyculin A-induced tension and LC20 phosphorylation, implicating MLCK in the Ca2+-independent contraction. We have used a combination of physiological and biochemical approaches, using demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips and chicken gizzard smooth muscle myofilament preparation to address this issue. Our starting point was the observation that a contractile response could be elicited in Triton X-100-demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle strips clamped at pCa 9 by addition of microcystin-LR. Microcystins are hepatotoxic cyclic heptapeptides produced by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae); they inhibit PP1 and PP2A with Ki values < 0.1 nM but have no effect on a variety of protein kinases (Mackintosh et al. 1990).

The microcystin-induced contraction of demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle at pCa 9 was slow compared with Ca2+-induced contractions of demembranated strips or K+-induced contraction of intact muscle strips: the time to half-maximal contraction induced by microcystin at pCa 9 was 12.8 ± 0.7 min compared with 1.9 ± 0.2 min for pCa 6-induced contraction, 1.3 ± 0.1 min for pCa 4.5-induced contraction and 0.12 ± 0.01 min for K+-induced contraction. Nevertheless, comparable steady-state tension levels were attained in each case: 221 ± 21 mg for microcystin-induced contraction at pCa 9, 246 ± 17 mg for pCa 6-induced contraction, 217 ± 25 mg for pCa 4.5-induced contraction and 255 ± 26 mg for K+-induced contraction. Ca2+-independent, microcystin-induced contraction correlated with slow phosphorylation of myosin LC20. At maximal force in response to microcystin at pCa 9, the stoichiometry of myosin phosphorylation was 1.24 mol Pi (mol LC20)−1 and consisted of 27.9 ± 1.3 % monophosphorylated LC20 and 48.1 ± 4.8 % diphosphorylated LC20. Using phosphorylation site-specific antibodies, LC20 phosphorylation was shown to occur at serine-19 and threonine-18. The level of LC20 phosphorylation at maximal pCa 6-induced force, by comparison, was significantly lower (0.25 mol Pi (mol LC20)−1) and consisted of 19.4 ± 5.2 % monophosphorylated LC20 and 2.8 ± 1.5 % diphosphorylated LC20. Many examples have been reported in the literature of maximal force at low levels of LC20 phosphorylation (originally demonstrated by Hoar et al. 1979). In Triton X-100-demembranated chicken gizzard, Schmidt et al. (1995) observed that the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid shifted the force-LC20 phosphorylation relationship significantly to the right, i.e. the same level of force in the presence of okadaic acid required higher levels of LC20 phosphorylation than in the absence of okadaic acid, with maximal force at ∼40 % LC20 phosphorylation. With rat caudal arterial smooth muscle, we have observed a similar, but more pronounced effect of microcystin on the force-LC20 phosphorylation relationship (L. P. Weber, M. Seto, Y. Sasaki and M. P. Walsh, unpublished observations). On the other hand, Siegman et al. (1989), using demembranated rabbit portal vein, observed no significant effect of okadaic acid on the force-LC20 phosphorylation relationship, with maximal force at ∼50 % LC20 phosphorylation. Our results, and those of Schmidt et al. (1995), are consistent with those of Kenney et al. (1990) who compared the relationships between LC20 phosphorylation or thiophosphorylation and tension in demembranated chicken gizzard smooth muscle strips: much higher levels of LC20 thiophosphorylation than phosphorylation were required for maximal force. Since thiophosphorylated LC20 is resistant to phosphatase, the phosphatase : kinase activity ratio would be low, as in our experiments with microcystin. According to the latch-bridge hypothesis of Hai & Murphy (1988), the formation of latch bridges is dependent upon dephosphorylation of phosphorylated cross-bridges which then slowly detach. In the presence of microcystin (or thiophosphorylated LC20), latch bridge formation will, therefore, be prevented. A higher level of LC20 phosphorylation would be required to generate the same amount of force in the presence of microcystin since there would be no contribution of latch bridges.

Since myofilaments contain contractile proteins in the ratios found in tissues, they are ideal for biochemical studies of the mechanisms involved in smooth muscle contraction. Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity was detected in myofilaments isolated from chicken gizzard smooth muscle (Fig. 12B-D). As with the rat caudal artery, the endogenous Ca2+-independent kinase in the myofilaments generated both mono- and diphosphorylated LC20, with phosphorylation occurring at serine-19 and threonine-18 (Figs 12 and 13). In contrast, using a similar concentration of purified MLCK as in the myofilament assay, Ca2+-independent LC20 monophosphorylation occurred exclusively at serine-19 (Figs 13-15). In addition, phosphopeptide mapping and phosphoamino acid analysis revealed that the myofilament kinase monophosphorylates LC20 at either serine-19 or threonine-18 (Figs 14 and 15). This is the first demonstration that LC20 can be phosphorylated exclusively at threonine-18 and indicates that a kinase distinct from MLCK is involved in Ca2+-independent LC20 phosphorylation during contraction. The functional effects of threonine-18 phosphorylation are not entirely clear. Using myosin in which LC20 was replaced by a mutant LC20 containing alanine in place of serine-19, Bresnick et al. (1995) showed that the actin-activated ATPase activity of myosin phosphorylated only at threonine-18 is ∼15-fold lower than that of myosin phosphorylated at serine-19, yet it moved actin filaments at velocities similar to myosin phosphorylated at serine-19 in the in vitro motility assay. Myosin phosphorylated at both serine-19 and threonine-18 exhibited an actin-activated ATPase activity ∼3-fold greater than that of myosin phosphorylated only at serine-19 (Ikebe & Hartshorne, 1985) but diphosphorylated myosin was indistinguishable from monophosphorylated myosin in the in vitro motility assay (Umemoto et al. 1989).

The Ca2+-independent kinase that catalyses LC20 phosphorylation during microcystin-induced contraction of demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle and in chicken gizzard myofilaments could be MLCK itself or a distinct kinase with similar substrate specificity. With regard to MLCK there are three possibilities: Ca2+-independent activity of the native enzyme, autophosphorylated MLCK or proteolysed MLCK. Purified MLCK had no detectable activity in the absence of Ca2+ unless assayed at high concentrations at which autophosphorylation occurred. The specific activity of autophosphorylated MLCK at close to the in vivo concentration is only 0.0005 % of maximal Ca2+-activated activity. We have presented several lines of evidence indicating that Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity is not due to autophosphorylated MLCK. (1) ∼90 % of myofilament-associated MLCK is extracted with 30 mM Mg2+ (fraction E1), but > 70 % of the Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase remains bound to the myofilaments and is extracted with 2 M NaCl (fraction E2) (Fig. 17 and Table 2). Some of the Ca2+-independent activity in E1 is attributable to autophosphorylated MLCK. (2) Residual MLCK in E2 is completely separated from the majority of Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity by CaM affinity chromatography (Fig. 18). (3) Ca2+-independent activity of autophosphorylated MLCK is inhibited by 40-50 % with 75 μM AV25 (a peptide inhibitor corresponding to the autoinhibitory domain of MLCK), but this peptide concentration has no significant effect on the myofilament Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase (Table 2 and Fig. 16) or microcystin-induced Ca2+-independent contraction (Table 1). On the other hand, Ca2+-induced LC20 phosphorylation and contraction were inhibited by AV25, similar to the ability of the related peptide SM-1 to block Ca2+-dependent contraction (Itoh et al. 1989). (4) The extremely low specific activity of autophosphorylated MLCK cannot account for the rate of LC20 phosphorylation and force development in demembranated rat caudal arterial smooth muscle treated with microcystin at pCa 9 (Figs 1 and 4 and Table 1).

We also ruled out the possibility that Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity is due to constitutive MLCK activity produced by partial proteolysis of the kinase by an endogenous protease, with removal of the autoinhibitory domain but retention of the catalytic domain (Walsh et al. 1982). (1) We could detect no proteolysis of MLCK in demembranated rat caudal arteries or chicken gizzard myofilaments by Western blotting, and inclusion of a cocktail of protease inhibitors had no effect on Ca2+-independent, microcystin-induced contraction. (2) MLCK and constitutively active MLCK generated by tryptic digestion were both inhibited by AV25 in vitro (Fig. 10), but Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase activity associated with chicken gizzard myofilaments (Fig. 16 and Table 2) and microcystin-induced contraction and LC20 phosphorylation in rat caudal arterial smooth muscle were unaffected by AV25 (Table 1). Furthermore, the MLCK inhibitory peptide SM-1 inhibits contraction elicited by exogenous constitutively active MLCK (Kargacin et al. 1990).

In conclusion, we have identified a Ca2+-independent kinase activity associated with the contractile apparatus in rat caudal artery and chicken gizzard that catalyses phosphorylation of myosin at serine-19 and threonine-18 of the 20 kDa light chains leading to contraction. This kinase is clearly distinct from MLCK. The possibility remains, however, that the kinase could be further activated via a second messenger pathway. This kinase is likely to be responsible, in part, for myosin phosphorylation that occurs in response to Ca2+-sensitizing signals that lead to inhibition of PP1M. Clearly, if the [Ca2+]i is sufficient to partially activate MLCK, it will also be involved in Ca2+ sensitization. At [Ca2+]i below the threshold for MLCK activation, only the Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase would be involved.

The only kinases apart from MLCK that have been shown to phosphorylate intact myosin in vitro are CaM kinase II (Edelman et al. 1990), protein kinase C (Ikebe et al. 1987), mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein (MAPKAP) kinase-2 (Komatsu & Hosoya, 1996) and Rho-associated kinase (Amano et al. 1996). The Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase is unlikely to be CaM kinase II due to its insensitivity to the CaM kinase II inhibitor peptide [Ala9]autocamtide 2 (Fig. 16) and the lack of phosphorylation by CaM kinase II at threonine-18. It cannot be PKC since this kinase phosphorylates LC20 at serine-1, serine-2 and threonine-9 (Ikebe et al. 1987 and Fig. 14B) and the Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase and microcystin-induced contraction at pCa 9 are resistant to PKC-selective inhibitors. It is also unlikely to be MAPKAP kinase-2 since this enzyme requires phosphorylation by MAP kinase for activation and exclusively phosphorylates serine-19, but not threonine-18, of LC20. Finally, it is unlikely to be Rho-associated kinase since the Ca2+-independent LC20 kinase was unaffected by 30 μM HA 1077 whereas Rho-associated kinase is inhibited by this isoquinolinesulphonamide derivative with a Ki of 0.33 μM (Uehata et al. 1997).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (MT-13101) to M. P. W. from the Medical Research Council of Canada. L. P. W. is recipient of a Fellowship from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. M. P. W. is a Medical Scientist of the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. The authors are very grateful to Drs Yasuharu Sasaki and Minoru Seto for generously providing antibodies pLC1 and pLC2, to Dr Bruce Kemp for advice concerning the design of peptide AV25, to Dr Karl Swärd and Cindy Sutherland for assistance with some experiments, and to Lenore Youngberg for expert secretarial assistance.

References

- Adachi K, Carruthers CA, Walsh MP. Identification of the native form of chicken gizzard myosin light chain kinase with the aid of monoclonal antibodies. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1983;115:855–863. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(83)80013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen BG, Andrea JE, Walsh MP. Identification and characterization of protein kinase Cζ-immunoreactive proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:29288–29298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M, Ito M, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Chihara K, Nakano T, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. Phosphorylation and activation of myosin by Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:20246–20249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley PM, Findlay WA, Martin SR. Target recognition by calmodulin: Dissecting the kinetics and affinity of interaction using short peptide sequences. Protein Science. 1996;5:1215–1228. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnick AR, Wolff-Long VL, Baumann O, Pollard TD. Phosphorylation on threonine-18 of the regulatory light chain dissociates the ATPase and motor properties of smooth muscle myosin II. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12576–12583. doi: 10.1021/bi00039a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colburn JC, Michnoff CH, Hsu L-C, Slaughter CA, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Sites phosphorylated in myosin light chain in contracting smooth muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:19166–19173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman AM, Lin W-H, Osterhout DJ, Bennett MK, Kennedy MB, Krebs EG. Phosphorylation of smooth muscle myosin by type II Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1990;97:87–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00231704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gailly P, Gong MC, Somlyo AV, Somlyo AP. Possible role of atypical protein kinase C activated by arachidonic acid in Ca2+ sensitization of rabbit smooth muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:95–109. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]