Abstract

The epithelia that line the airways of the lung exhibit two general functions: (1) airway epithelia in all regions ‘defend’ the lung against infectious and noxious agents; and (2) airway epithelia in the proximal regions replenish water lost from airway surfaces, i.e. the ‘insensible water loss’, consequent to conditioning inspired air. How airway epithelia perform both functions, and co-ordinate them in health and disease, is the subject of this review.

Airway epithelial defence mechanisms

Airway epithelia defend the interstitial compartment with a surface liquid layer and the barriers conferred by the apical cell membranes and the intercellular tight junctions. Because of the scope of the review, the discussion of the tight junctions will focus only on their ion permeability characteristics and not their barrier characteristics for toxins/infectious agents.

Despite the importance of airway surface liquid (ASL) in lung defence, emphasized in studies of the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis (CF), there is no accepted description of ASL physiology at the organ level. This lack of consensus reflects the difficulties in both studying the function of a thin (∼25 μm) watery layer in vivo and generating accurate models to simulate the functions of this layer in vitro. In general, two quite different theories have been advanced to describe ASL physiology in normal human lungs and the dysfunction(s) consequent to mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) in CF.

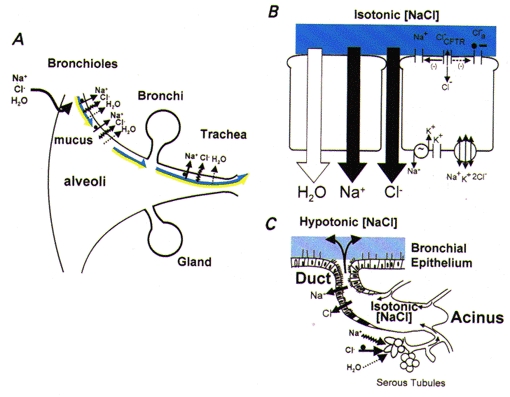

The ‘isotonic volume transport/mucus clearance’ theory (Boucher, 1994; Matsui et al. 1998a) focuses on the role of isotonic volume transport in controlling the volume, and consequently height, of ASL (Fig. 1). From an organ-level viewpoint (Fig. 1A), this theory predicts that both the mucous and periciliary liquid (PCL) layers of ASL are swept up the converging airway surfaces by cilia- and gas-liquid-dependent transport mechanisms. As liquid converges onto narrowed airway surfaces, a fraction of the ASL must be absorbed to control ASL height, thus minimizing air flow resistance and promoting effective mucus clearance.

Figure 1. Isotonic volume transport model.

A, organ-level description. The relative surface areas (not to scale) of the different regions are shown. Both components of ASL are represented as being transported cephalad on pulmonary surfaces (bicoloured arrows: dark blue, isotonic PCL component; yellow, mucous component). In the airways, the mechanisms for absorption from ASL are driven by active Na+ absorption, with Cl− and water accompanying passively. The bronchioles are shown as absorptive. Liquid could be secreted in either very distal bronchiolar regions or, as depicted, on alveolar surfaces. B, model of superficial airway epithelial cells mediating isotonic volume transport. The basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase generates the driving force for Na+ entry across the apical membrane, which is mediated by ENaCs. Both functions of CFTR, as a Cl− channel () and as regulator of ENaC (Na+), and the alternative (Ca2+-activated) Cl− channel (Cl−a) are depicted on the apical membrane. Active Na+ absorption is transcellular, whereas anion flow is, in part, cellular and, in larger part, transcellular. The epithelium is quite permeable to water, permitting isosmotic volume transport. Hence, the ASL is designated as isotonic [NaCl] (depicted in dark blue). C, submucosal gland. Isotonic volume secretion in the acinus is illustrated mediated by active Cl− secretion coupled with passive Na+ and water secretion, which probably reflects a significant contribution from serous tubules expressing CFTR located in the acinar region. The gland ducts are represented as absorbing NaCl, but not water, resulting in a hypotonic secretion (depicted in light blue).

The cellular basis for isotonic transport is described in Fig. 1B (Boucher, 1994). In this schema, airway epithelia tonically absorb Na+ through a transcellular route, mediated at the apical membrane by the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) and at the basolateral membrane by Na+-K+-ATPase. Passive anion flow, which probably reflects the movement of both Cl− and HCO3−, can occur in part transcellularly, but the major fraction occurs through the paracellular path. Because the epithelium is water permeable, ion transport is isosmotic, leaving ASL nearly isotonic under basal conditions. The model predicts that the epithelium must finely tune PCL height for efficient mucus transport, suggesting that there are sensors that control the rate of Na+ transport and, in certain conditions, initiate Cl− and volume secretion to optimize ASL height/volume.

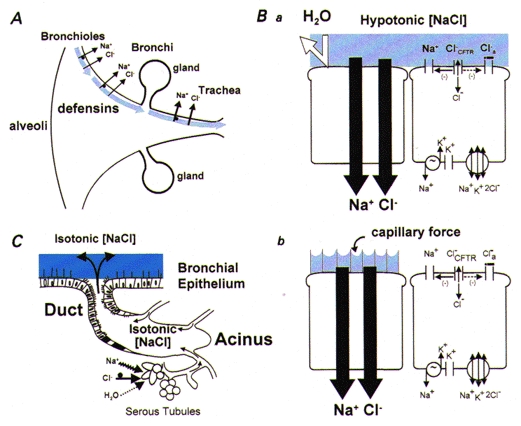

The ‘low salt (hypotonic)/defensin theory’ postulates that the superficial epithelium regulates the ionic composition rather than the volume of ASL (Quinton, 1994; Zabner et al. 1998). In this theory, normal epithelium lowers the ASL Na+ and Cl− concentrations ([NaCl]) to a value of 50 mM l−1 or less to promote the activity of antimicrobial defensin-like molecules. Hence at the organ level (Fig. 2A), according to this theory, there would be no major role for mucus in lung defence; indeed, in one postulated mechanism for generating hypotonic ASL (see Fig. 2Bb) the presence of a mucin blanket on normal airway surfaces cannot be ‘tolerated’ (Widdicombe, 1997). Furthermore, if lung defence is dependent on ASL ion composition, then it would not be essential for ASL to be cleared from airway surfaces; indeed, the other postulated mechanism to generate hypotonic ASL does not permit volume (water) absorption (see Fig. 2Ba).

Figure 2. Hypotonic airway surface liquid physiology.

A, organ-level description. The epithelium lining airway surfaces is represented as absorbing NaCl but not water from ASL (shown as light blue to indicate hypotonicity). Antimicrobial substances (defensins) are shown, which are active in this ‘low salt’ environment. No arrows depicting surface liquid clearance are shown, due to the inability of the cell models (see below) to deal with volume absorption or a mucous layer. B, cell models postulated to explain the production of hypotonic ASL. Ba, the ‘sweat ductal model’. The key elements are the transcellular absorption of Na+ (via ENaC) and Cl− (via CFTR) and epithelial water impermeability (depicted as ‘deflected’ arrow). Bb, the ‘surface forces’ model. Outstretched cilia are depicted on the left cell that generate small radius (< 0.1 μm) menisci at an air-water interface of high surface tension. NaCl is absorbed transcellularly and the osmotic force generated to absorb H2O from the airway surface is balanced by ‘capillary’ forces generated by the menisci, resulting in a low [NaCl] ASL. C, submucosal glands. Based on previous reports (Quinton, 1979), this model might predict isotonic gland secretion. Presumably, this process adds volume to the surface and compositional modification (lowering [NaCl]) is performed by the superficial epithelium.

At least two different cellular mechanisms could theoretically produce low [NaCl] hypotonic ASL in normal subjects (Fig. 2B). In the simplest of these mechanisms, airway epithelia function like sweat ductal epithelia (Fig. 2Ba), with relatively high transcellular transport of both Na+ and Cl−, coupled with low cellular water permeability, so that hyperosmotic absorption is effected. In the second mechanism (Fig. 2Bb), it has been postulated that ‘surface forces’ could develop to counterbalance the osmotic forces generated by salt absorption, perhaps reflecting the generation of small radius menisci with a high surface tension between the tips of outstretched cilia (Widdicombe et al. 1997; Zabner et al. 1998). Finally, it has been suggested that normal ASL exhibits low [NaCl], but is isotonic, reflecting the presence of ∼200 mosmol l−1 or more of ‘unidentified osmotic material’ in normal ASL (Zabner et al. 1998).

Comparison of isotonic versus hypotonic theories

A variety of approaches have been used to compare these theories, including molecular techniques and novel cell culture models. A key discriminator between these two theories is the function of CFTR. With respect to the isotonic theory, a role for CFTR in regulating other channels, particularly the ENaC, has been postulated. In contrast, the hypotonic theory postulates that CFTR functions in airway epithelial cells solely as a Cl− channel. Thus, the comparison of the activities of normal and mutated CFTR in a variety of functional systems has proved to be one useful strategy to test these theories.

Heterologous expression of CFTR

A vast number of studies have been performed expressing CFTR cDNAs in heterologous cells. The initial series of reports established a role for CFTR as a cAMP-regulated Cl− channel (Bear et al. 1992; Anderson et al. 1991). However, subsequent studies revealed a role for CFTR in regulating other ion channels. Perhaps the first data were those of Guggino and colleagues, which established that CFTR could regulate an outward rectifying Cl− channel (Egan et al. 1992). More recently, it has become clear that CFTR can regulate the activity of the ENaC (Stutts et al. 1995). Interestingly, some heterologous cell expression systems detect such regulatory interactions, whereas others do not. These findings are congruent with studies from CF patients in vivo and with freshly excised tissues that reveal CFTR regulation of ENaC is expressed in some epithelia, e.g. airway epithelia, but not others, e.g. sweat duct. These data demonstrate the importance of the ‘context’ of the epithelial cell, suggesting that cell-specific protein-protein interactions are important components of these regulatory phenomena. Thus, these studies have verified that CFTR functions both as a Cl− channel, as emphasized in the hypotonic theory, and as an ENaC regulator, as postulated in the isotonic theory.

Epithelial cell culture models

A major advance in the field of airway epithelial biology has been the advent of air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures. In general, airway epithelial cell cultures grown under ALI conditions exhibit a striking degree of morphological differentiation. However, despite the congruence of morphological differentiation produced in a number of laboratories using quite different ALI techniques, the functional properties of these cultures are quite different. For example, Zabner et al. (1998) recently reported that normal airway epithelia grown under ALI conditions generate a low [NaCl] solution on airway surfaces. Key functional features of the Zabner et al. (1998) model have been its relatively high transepithelial resistance (Rt) and potential difference. In contrast, Matsui et al. (1998a) have presented data on an ALI airway epithelial model that exhibit lower Rt values and surface (rotational) mucus transport as major functional properties. Labelling the ASL of these cultures with fluorophores allowed visualization of both the mucous and PCL layers with confocal microscopy. This technique demonstrated that mucus transport rates are sensitive to the rates of transepithelial volume transport and regulation of PCL depth. Importantly, direct measurements in this system demonstrated that ASL is isosmolar, the [NaCl] is similar to that of plasma (> 100 mM NaCl), and there is little ‘unidentified’ osmotic material. These measurements were confirmed in a novel hollow biofibre system, in which the cylindrical geometry of airway epithelia is simulated in culture (Matsui et al. 1998a).

The divergent results from the ALI culture systems emphasize that morphology cannot be the sole criterion for model relevance. A critical variable sensitive to culture conditions is the Rt, which reflects the ionic conductance of both the cellular and paracellular paths. Rt in freshly excised airway tissues is relatively low (∼100-200 Ω cm2), reflecting the high permeability of the paracellular path as estimated from mannitol permeability (Pmannitol, 20 × 10−7 cm s−1) (Boucher, 1994). In contrast, in some cell culture models (Zabner et al. 1998), Rt is perhaps an order of magnitude higher than in freshly excised epithelia, which suggests that paracellular and cellular ionic conductances do not mimic airway epithelia in vivo. Such considerations emphasize the need to make comparisons of transport parameters common to the in vivo and in vitro situations to test the relevance of culture models.

Mouse models

A variety of CF mouse models have been generated by gene targeting (Grubb & Boucher, 1999). The phenotypes of the mouse models have been informative with respect to the differences in organ-level CF pathogenesis among, for example, the pancreas, vas deferens, and lung as compared with the gut, but unfortunately do not differentiate between the isotonic versus hypotonic theories. In particular, little CFTR protein is expressed in the mouse lung, and it appears that the murine lung performs anion transport predominantly by a Ca2+-activated ‘alternative’ Cl− channel (Cl−a). Furthermore, Na+ transport rates are not greatly increased in the CF mouse lung, suggesting a mechanism for ENaC regulation independent of CFTR. Thus, to distinguish between these two theories it will be important to both identify and target Cl−a and develop transgenic animals that overexpress Na+ transport.

Human diseases - in vivo studies

The obvious genetic disease to help discriminate between these theories is CF. There have been no direct studies of airway epithelial volume absorption in vivo. Studies of ASL ion composition in normal and CF subjects have been performed with a spectrum of techniques and the results have been variable. Recently, studies have focused on comparison of normal and CF subjects prior to infection and the results are more uniform (Knowles et al. 1997; Hull et al. 1998). These data indicate that under basal conditions, the nasal epithelia of both normal and CF subjects are lined with isotonic ASL, but that stimulation of glands can produce transiently hypotonic ASL that is similar in volume and composition in CF and normal subjects (see Fig. 1). In the bronchi, these measurements are less complete and more difficult to make. The data suggest that after application of filter papers or electrodes, bronchial ASL is modestly hypotonic (∼240 mosmol l−1), and again does not differ between normal and uninfected CF subjects. It has been speculated that instrumentation produces sufficient local irritation in the bronchi to induce reflex gland secretion. Because gland secretion in the lower airways is mediated by both cholinergic and tachykinin receptors, it is difficult to block both receptors in vivo to test this notion. Despite this, on balance, studies of ASL composition in vivo tend to support the isotonic rather than hypotonic theory and clearly show no differences in ASL ion composition between uninfected CF patients and normal subjects.

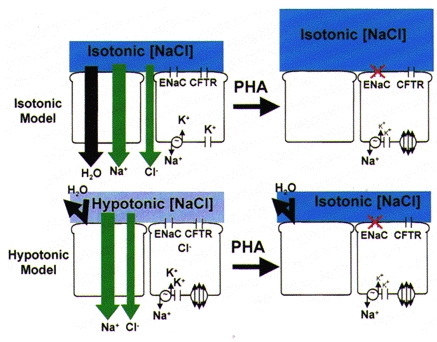

A genetic disease reflecting loss-of-function mutations in the ENaC, pseudohypoaldosteronism (PHA), has been particularly valuable in discriminating between the isotonic and hypotonic ASL theories (see Fig. 3). Based on the predicted loss of airway epithelial Na+ transport in PHA, the isotonic volume theory (Fig. 3, upper panel) predicts that ASL volume, but not tonicity, will be perturbed, whereas the hypotonic theory (Fig. 3, lower panel) predicts that ASL composition, not volume, will be deranged. A corollary of the hypotonic ASL theory is that the predicted raised [NaCl] will inactivate defensins and produce a chronic infectious lung syndrome like CF. Studies of nine PHA patients revealed that airway epithelial electrogenic Na+ transport was indeed abolished, as evidenced by a reduction (∼70 %) in the basal potential difference (PD) and an absence of amiloride effects (Kerem et al. 1999). Measurements of ASL revealed that: (1) the ASL was isotonic; (2) there were modest changes in the ratio of the major solution cations, i.e. Na+ was higher and K+ lower than in normal ASL, consistent with the absence of electrogenic Na+ transport; and (3) ASL volume measured semi-quantitatively by filter paper or by direct visual inspection was strikingly increased. Thus, these functional data in PHA patients strongly favour the isotonic rather than the hypotonic hypothesis.

Figure 3. Predicted airway surface liquid ‘phenotypes’ as a consequence of loss-of-function mutations in ENaC associated with pseudohypoaldosteronism (PHA).

Upper panel, the isotonic model predicts that loss of transepithelial Na+ absorption will abolish most volume absorption and increase the volume of isotonic liquid (shown in dark blue) on epithelial surfaces. Lower panel, the hypotonic model predicts that NaCl absorption but not volume (H2O) absorption will be perturbed in PHA, resulting in conversion of ASL from hypotonic (‘low salt’, shown in light blue) to isotonic (‘high salt’, shown in dark blue) ASL with no change in volume.

A key observation emanating from this study was the effect of this physiological dysfunction on the lung. In contrast to hypotonic theory predictions, there was no evidence of ‘defensin’ inactivation manifested as chronic suppurative lung disease. In brief, PHA patients did not exhibit sinus disease, lower airway bronchiectatic disease, or pseudomonal or staphylococcal infections. In contrast, PHA patients did exhibit a syndrome in early life (0-4 years old), characterized by methacholine hyper-reactivity and wheezing associated with intermittent viral infections, that is consistent with a narrowing of airway lumens by excess liquid.

The isotonic hypothesis has predicted that if volume absorption did not occur as ASL was transported along convergent airway surfaces, intrapulmonary ‘drowning’ in proximal airways would result (Kilburn, 1968). Such was not the case in patients with PHA. Further study of ASL physiology in PHA patients revealed that they exhibited an astonishing increase in the rate of clearance of liquid from airway surfaces by mucociliary transport, which acts as a ‘compensatory’ mechanism to offset the absence of transepithelial volume absorption. Furthermore, these data suggest that the additional liquid on PHA airway surfaces does not ‘float off’ the mucus layer from the tips of the cilia, slowing mucus transport, as had previously been predicted (Kilburn, 1968). Rather, the excess liquid is added to the mucous layer, which acts a reservoir and mediates the efficient clearance of ASL that avoids intrapulmonary ‘drowning’.

‘Score card’ comparing isotonic and hypotonic theories

A tabular comparison of the predictions for the isotonic versus hypotonic theories and relevant data/citations are shown in Table 1. Many of these predictions have been discussed and will not be reiterated here, and the reader is referred to the references in Table 1 describing the relevant data set. Some observations discriminate predominantly between predictions of the isotonic theory and specific cellular models (Fig. 2B) for the hypotonic theory. For example, the presence of a mucin layer is compatible with the sweat ductal model and the isotonic theory, but is incompatible with the surface forces model.

Table 1.

Predictions for the isotonic versus hypotonic theories of airway surface liquid physiology - comparison with reported data

| Hypotonic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isotonic | Sweat duct | Capillary forces | Data/Citation | |

| Mucous layer present | Yes | No | No | Mucous layer identified (Sims & Horne, 1997) |

| Axial surface liquid movement | Yes | No | No | Mucous and PCL layers move (Matsui et al. 1998b) |

| Water permeability | High | Low | High | Relatively high (Farinas et al. 1997; Matsui et al. 1999) |

| Volume absorption | Yes | No | Yes/Stops | Yes (Jiang et al. 1993; Matsui et al. 1998a) |

| Cl−1 absorption | Paracellular | Transcellular | Transcellular | Not yet reported |

| Functional effects of capillary forces | Small | Small | ‘Large’ | Small (Matsui et al. 1998a) |

| Na+–K+-ATPase activity | Upregulated | Downregulated | Downregulated | Upregulated (Stutts et al. 1986; Peckham et al. 1997) |

One key function that discriminates between the two theories in general terms is the movement of the PCL along airway surfaces, which is integral to the isotonic theory but cannot easily be tolerated by the hypotonic theory. Another critical discriminator is the route(s) of Cl− transport across the airway epithelium. The isotonic model predicts that Cl− largely moves through the paracellular path (Boucher, 1994). Importantly, this path is probably relatively non-selective for cations versus anions, as might be optimal for an epithelium that at times absorbs or secretes, but the key parameter is the magnitude of the conductance available for paracellular anion flow, not the relative permselectivity. The observation that the Na+-K+-ATPase activity is increased in CF is more consistent with the increased net Na+ transport predicted by the isotonic theory than the depressed transport predicted by the hypotonic theory. On balance, the ‘score card’ appears to heavily favour the isotonic theory.

Humidification functions of airway epithelia

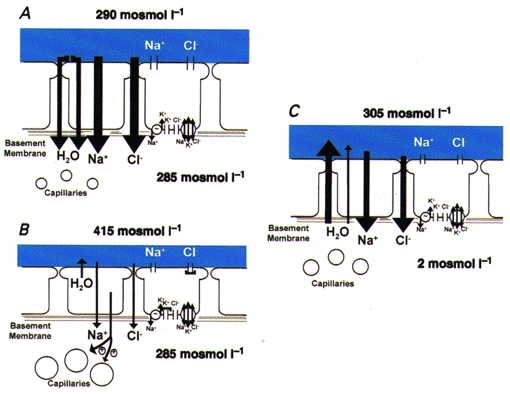

The lung loses approximately 700 ml of water per day from its proximal airway surfaces and a key physiological question is: how are these losses efficiently replenished? The model shown in Fig. 4 describes one mechanism.

Figure 4. Restoration of water balance in ASL in response to accelerated evaporative water loss.

A, airway epithelium under basal conditions (osmolarity of the ASL slightly exceeds that of the interstitium). B, consequent to accelerated evaporative water loss, the volume of ASL is reduced and NaCl becomes concentrated, which provides the osmotic driving force (depicted as osmolarity raised to 415 mosmol l−1) that leads to (1) epithelial shrinkage, (2) slowing of active ion absorption (depicted as smaller vectors) consequent to inhibition of apical Cl− channels and basolateral K+ channels (depicted as ‘caps’ on channel pores), and (3) signalling, via a nitric oxide synthase-mediated system to the submucosal microvasculature to promote dilatation. C, restoration of water to airway surface. Water moves from the interstitium across the epithelium via cellular and perhaps paracellular routes in response to the luminal solution osmolar gradient to replenish the volume of ASL.

In vivo studies of ASL composition in dogs demonstrated that transient increases in tracheal ASL osmolarity were generated by exposure to poorly conditioned air, as measured by both nylon screen and filter paper sampling techniques (Man et al. 1979; Boucher et al. 1981). This change was rapidly reversed upon breathing fully humidified air. Optical and intracellular microelectrode studies of culture preparations revealed that airway epithelia behaved (‘shrank’) as almost perfect osmometers in response to increases in ASL osmolarity (Willumsen et al. 1994). Subsequent studies using confocal microscopy revealed that: (1) the apical membrane osmotic water permeability (Pf,A) exceeded that of the basolateral membrane (Pf,B), consistent with the epithelium functioning as a sensor of ASL osmolarity (Matsui et al. 1999); and (2) water moved rapidly onto airway surfaces in response to osmolar gradients, indicating that airway transepithelial osmotic water permeability (Pf,T) is relatively high. Optical studies in vivo in rats indicated that the shrinkage of airway epithelia in response to hyperosmolar ASL signalled the microvasculature to dilate, which provides the ultimate source of water to replenish airway surfaces (Prazma et al. 1994).

Molecular studies have focused on the role of cloned aquaporins as mediators of transepithelial water flow in the airways. Studies of airway aquaporin localization have revealed that aquaporin IV is located on the basolateral membranes of columnar airway epithelial cells and aquaporin III is located on airway basal cells, but the aquaporin that lines the luminal membrane of airway epithelial cells has not been identified (Lee et al. 1997). Gene targeting studies have produced aquaporin IV-deficient mice that do not express a detectable airway phenotype (Ma et al. 1997); the results from the aquaporin III targeted mice are pending.

In summary, airway epithelia appear to replenish water loss from proximal airway surfaces by using the osmolar gradients generated by evaporative water loss to generate transepithelial water flux. Note that the model proposed in Fig. 4 describes the response to acute evaporative water loss. A similar mechanism will account for basal water losses associated with lower evaporation rates and smaller osmolar gradients. The presence of a hypotonic (low salt) ASL (50 mM NaCl, i.e. 100 mosmol l−1) is inconsistent with this mechanism because interstitial osmolarity (∼285 mosmol l−1) would provide a driving force for water flow in a direction opposite to that needed to replenish water on airway surfaces. This consideration, coupled with the high Pf,T (Table 1), favours the isotonic theory in explaining humidification functions of airway epithelia.

Integrated activities of airway epithelia

An accurate description of ASL physiology requires an integration of the activities that regulate ASL volume by active ion transport and the continual requirement to replenish evaporative water loss. Such an integration can be envisioned in the context of the isotonic hypothesis as follows.

First, a key concept is that the mass of salt on airway surfaces determines the ASL height/volume. This result follows from the Pf,T of airway epithelia, which will, under most circumstances, maintain isotonic solutions on airway surfaces.

Second, the mass of salt on airway surfaces is determined by active ion transport processes that are energy dependent. Na+ absorption is the major tonic transport activity under ‘thin film’ ASL conditions. However, the rate and even direction of net ion transport may be modulated by unknown ‘sensors’ that sense ASL height and adjust the rates of Na+ absorption and perhaps Cl− secretion to finely regulate the mass of salt and consequently liquid on airway surfaces.

Third, evaporative water loss occurs from ASL but is replenished by a feedback system that is energy independent. The driving force that promotes the net flux of water onto airway surfaces is the increase in ASL osmolarity generated by evaporation.

Fourth, the critical link between these two functions, i.e. the active salt transport as a determinant of ASL height, and the replenishment of water loss from epithelial surfaces due to evaporation, is an epithelium with a relatively high Pf,T.

It is difficult to envision how this type of unified physiology could occur in an epithelium that functions to generate hypotonic (low salt) ASL, because such a model accounts for neither ASL volume regulation nor water replenishment on airway surfaces via evaporation-induced osmotic forces.

Future

Important studies for the future include those that directly measure both ASL composition and volume in vivo. Because virtually all invasive techniques will perturb ASL, e.g. induce reflex gland secretion, it will be important to develop indicators that measure ASL composition and volume absorption, if it exists, externally after aerosolized probe delivery. At the cellular level, it will be important to identify the ‘sensors’ that maintain the ASL height (volume) as ‘thin films’, which ‘effectors’ are regulated by sensors, e.g. Na+ transport and Cl− secretion, and how these processes are perturbed in disease. It will be important to understand how the overlying mucous layers are organized and whether mucous layers act as ‘reservoirs’ for water on airway surfaces that buffer changes in ASL volume to maintain efficient mucus clearance. Finally, therapies directed at modulating ASL volume and composition will be important. Indeed, if certain diseases result in too little volume on airway surfaces, e.g. CF, then ways must be developed to add salt to airway surfaces, which will obligate the necessary rehydration to restore ASL volume (Matsui et al. 1998a).

References

- Anderson MP, Gregory RJ, Thompson S, Souza DW, Paul S, Mulligan RC, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Demonstration that CFTR is a chloride channel by alteration of its anion selectivity. Science. 1991;253:202–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1712984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear CE, Li C, Kartner N, Bridges RJ, Jensen TJ, Ramjeesingh M, Riordan JR. Purification and functional reconstitution of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cell. 1992;68:809–818. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher RC. Human airway ion transport (Part 1) American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1994;150:271–281. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher RC, Stutts MJ, Bromberg PA, Gatzy JT. Regional differences in airway surface liquid composition. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1981;50:613–620. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.50.3.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan M, Flotte T, Afione S, Solow R, Zeitlin PL, Carter BJ, Guggino WB. Defective regulation of outwardly rectifying Cl− channels by protein kinase A corrected by insertion of CFTR. Nature. 1992;358:581–584. doi: 10.1038/358581a0. 10.1038/358581a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinas J, Kneen M, Moore M, Verkman AS. Plasma membrane water permeability of cultured cells and epithelia measured by light microscopy with spatial filtering. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:283–296. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.3.283. 10.1085/jgp.110.3.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb BR, Boucher RC. Pathophysiology of gene-targeted mouse models for cystic fibrosis. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79:S193–214. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull J, Skinner W, Robertson C, Phelan P. Elemental content of airway surface liquid from infants with cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;157:10–14. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9703045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Finkbeiner WE, Widdicombe JH, McCray PB, Jr, Miller SS. Altered fluid transport across airway epithelium in cystic fibrosis. Science. 1993;262:424–427. doi: 10.1126/science.8211164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem E, Bistritzer T, Hanukoglu A, Hofmann T, Zhou Z, Bennett W, MacLaughlin E, Barker P, Nash M, Quittell L, Boucher R, Knowles MR. Respiratory disease in pseudohypoaldosteronism: epithelial sodium channel dysfunction with excess airway surface liquid. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999 doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410304. in the Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilburn KH. A hypothesis for pulmonary clearance and its implications. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1968;98:449–463. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1968.98.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles MR, Robinson JM, Wood RE, Pue CA, Mentz WM, Wager GC, Gatzy JT, Boucher RC. Ion composition of airway surface liquid of patients with cystic fibrosis as compared to normal and disease-control subjects. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;100:2588–2595. doi: 10.1172/JCI119802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MD, King LS, Agre P. The aquaporin family of water channel proteins in clinical medicine. Medicine (Baltimore) 1997;76:141–156. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199705000-00001. 10.1097/00005792-199705000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS. Generation and phenotype of a transgenic knockout mouse lacking the mercurial-insensitive water channel aquaporin-4. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;100:957–962. doi: 10.1172/JCI231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man SFP, Adams GK, III, Proctor DF. Effects of temperature, relative humidity, and mode of breathing on canine airway secretions. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1979;46:205–210. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.46.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui H, Davis CW, Tarran R, Boucher RC. Osmotic water permeabilities of cultured, well-differentiated normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999 doi: 10.1172/JCI4546. in the Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui H, Grubb BR, Tarran R, Randell SH, Gatzy JT, Davis CW, Boucher RC. Evidence for periciliary liquid layer depletion, not abnormal ion composition, in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis airways disease. Cell. 1998a;95:1005–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui H, Randell SH, Peretti SW, Davis CW, Boucher RC. Coordinated clearance of periciliary liquid and mucus from airway surfaces. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998b;102:1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckham D, Holland E, Range S, Knox AJ. Na+/K+ ATPase in lower airway epithelium from cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis lung. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;232:464–468. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6200. 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prazma J, Coleman CC, Schockley WW, Boucher RC. Tracheal vascular response to hypertonic and hypotonic solutions. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994;76:2275–2280. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.6.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton PM. Composition and control of secretions from tracheal bronchial submucosal glands. Nature. 1979;279:551–552. doi: 10.1038/279551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton PM. Viscosity versus composition in airway pathology. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1994;149:6–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.1.8111599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims DE, Horne MM. Heterogeneity of the composition and thickness of tracheal mucus in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:L1036–1041. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.5.L1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutts MJ, Canessa CM, Olsen JC, Hamrick M, Cohn JA, Rossier BC, Boucher RC. CFTR as a cAMP-dependent regulator of sodium channels. Science. 1995;269:847–850. doi: 10.1126/science.7543698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutts MJ, Knowles MR, Gatzy JT, Boucher RC. Oxygen consumption and ouabain binding sites in cystic fibrosis nasal epithelium. Pediatric Research. 1986;20:1316–1320. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198612000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe JG. Airway surface liquid: concepts and measurements. In: Rogers DF, Lethem MI, editors. Airway Mucus: Basic Mechanisms and Clinical Perspectives. Birkhauser, Basel: 1997. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe JH, Bastacky SJ, Wu DX, Lee CY. Regulation of depth and composition of airway surface liquid. European Respiratory Journal. 1997;10:2892–2897. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10122892. 10.1183/09031936.97.10122892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willumsen NJ, Davis CW, Boucher RC. Selective response of human airway epithelia to luminal but not serosal solution hypertonicity: possible role for proximal airway epithelia as an osmolality transducer. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1994;94:779–787. doi: 10.1172/JCI117397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabner J, Smith JJ, Karp PH, Widdicombe JH, Welsh MJ. Loss of CFTR chloride channels alters salt absorption by cystic fibrosis airway epithelia in vitro. Molecular Cell. 1998;2:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80284-1. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]