Abstract

In order to investigate the possible effect of membrane potential on cytoplasmic Na+ binding to the Na+-K+ pump, we studied Na+-K+ pump current-voltage relationships in single guinea-pig ventricular myocytes whole-cell voltage clamped with pipette solutions containing various concentrations of Na+ ([Na+]pip) and either tetraethylammonium (TEA+) or N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG+) as the main cation. The experiments were conducted at 30 °C under conditions designed to abolish the known voltage dependence of other steps in the pump cycle, i.e. in Na+-free external media containing 20 mM Cs+.

Na+-K+ pump current (Ip) was absent in cells dialysed with Na+-free pipette solutions and was almost voltage independent at 50 mM Na+pip (potential range: −100 to +40 mV). By contrast, the activation of Ip by 0.5–5 mM Na+pip was clearly voltage sensitive and increased with depolarization, independently of the main intracellular cation species.

The apparent affinity of the Na+-K+ pump for cytoplasmic Na+ increased monotonically with depolarization. The [Na+]pip required for half-maximal Ip activation (K0.5 value) amounted to 5.6 mM at −100 mV and to 2.2 mM at +40 mV.

The results suggest that cytoplasmic Na+ binding and/or a subsequent partial reaction in the pump cycle prior to Na+ release is voltage dependent. From the voltage dependence of the K0.5 values the dielectric coefficient for intracellular Na+ binding/translocation was calculated to be ≈0.08. The voltage-dependent mechanism might add to the activation of the cardiac Na+-K+ pump during cardiac excitation.

The Na+-K+ pump of animal cells exchanges three intracellular Na+ (Na+i) for two extracellular K+ (K+o) per ATP molecule hydrolysed and is, therefore, electrogenic. It generates the steady-state pump current, Ip. Under physiological conditions Ip is an outward current exhibiting a characteristic voltage dependence. The current decreases at negative membrane potentials and displays a maximum (Lafaire & Schwarz, 1986) or remains nearly constant (Gadsby et al. 1985) at positive voltages. Na+-free external solution containing physiological [K+]o reduces or abolishes the voltage dependence of Ip at negative potentials (Gadsby & Nakao, 1989; Rakowski et al. 1989, 1991; Bielen et al. 1991). A negative slope of the Ip-V relationship can be observed at low [K+]o, especially in Na+-free media (Bielen et al. 1991, 1993; Rakowski et al. 1991). These and other findings reveal voltage-dependent (re)binding of extracellular Na+ and K+ to the Na+-K+ pump. The voltage dependence of cation binding is probably due to the existence of a ‘high-field, narrow access channel’ (cf. Läuger, 1991) at the bottom of which the interaction between external Na+, K+ and their respective binding sites takes place (review: Rakowski et al. 1997b). Whether a similar access channel to the intracellular cation binding sites of the pump exists is an unsettled question. Data from vesicles (Goldshlegger et al. 1987; Or et al. 1996) and membrane fragments containing Na+-K+ pumps (Stürmer et al. 1991; Heyse et al. 1994; Wuddel & Apell, 1995) suggest a positive answer to this question, whereas whole-cell recordings from cardiac myocytes do not permit an unequivocal conclusion (Nakao & Gadsby, 1989; Kockskämper & Glitsch, 1997). Binding of internal Na+ to the Na+-K+ pump is a mechanism of physiological relevance since, under physiological conditions, the pump activity is predominantly regulated by changes in [Na+]i. The aim of the present work was to find out if the binding of intracellular Na+ to the Na+-K+ pump is voltage dependent. The experiments to be described were carried out on whole-cell voltage-clamped guinea-pig ventricular myocytes under conditions designed to exclude the troublesome effects of simultaneous, voltage-dependent binding of extracellular cations on the steady-state Ip measurements. The results suggest that cytoplasmic Na+ binding and/or another step in the Na+ translocation limb of the pump cycle prior to Na+ release is voltage dependent.

METHODS

Isolation of ventricular myocytes

Ventricular myocytes were isolated essentially as described previously (Kockskämper et al. 1997). Briefly, adult female guinea-pigs (200–450 g) were killed by cervical dislocation. Following thoracotomy, hearts were cannulated via the aorta and quickly excised, then mounted on a Langendorff apparatus and perfused at 37°C with oxygenated Ca2+-free solution containing (mM): sucrose, 204; NaCl, 35; KCl, 5.4; MgCl2, 1.0; EGTA, 2.0; Hepes, 10; pH 7.4 (adjusted with NaOH). After 2 min, perfusion was changed to a medium additionally containing collagenase B (0.4 mg ml−1, Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), protease (type XIV, 0.3 mg ml−1, Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), elastase (10 μl ml−1, Serva, Heidelberg, Germany), DNase (0.15 mg ml−1, Sigma), bovine serum albumin (BSA, 0.5 mg ml−1, Sigma), and 0.1 mM instead of 2.0 mM EGTA. Digested ventricles were cut into small pieces and transferred to nominally Ca2+-free, protease-free solution containing BSA and DNase. Finally, this solution was exchanged for cell culture medium (1.3 mM Ca2+; Hanks' medium 199, PAA, Linz, Austria) supplemented with 105 i.u. l−1 penicillin and 100 mg l−1 streptomycin (both from Sigma). Isolated cardiomyocytes were plated on culture dishes and kept in an incubator (37°C, 3 % CO2) until use on the same day.

Experimental solutions

The extracellular (superfusion) solution was composed of (mM): N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG) 145; CsCl 20; BaCl2 4.0; MgCl2 1.0; CdCl2 0.2; Hepes 10; pH 7.4 (adjusted with HCl).

Two pipette solutions were used, one based on NMDG and the other based on tetraethylammonium (TEA+). The Na+ concentration of the respective solution was varied by equimolar substitution for NMDG or TEA+. The composition of the NMDG-based solution was (mM): NMDG plus Na+, 160; aspartic acid, 120; HCl, 40; MgCl2, 3; EGTA, 6; Hepes, 10; MgATP, 10; pH 7.3 (adjusted with NMDG). TEA+-based solution contained (mM): TEA-Cl plus NaCl, 135; TEA-OH, 20; MgCl2, 3; EGTA, 6; Hepes, 16; MgATP, 10; pH 7.3 (adjusted with TEA-OH).

The solutions were designed in order to abolish voltage-dependent (re)binding of extracellular Na+ and Cs+ to the Na+-K+ pump (cf. Rakowski et al. 1997b) and to suppress currents via ion channels and electrogenic transporters. Thus, the superfusate was Na+-free and contained a high concentration of Cs+ (20 mM) saturating the external K+/Cs+ binding sites of the cardiac Na+-K+ pump (Bielen et al. 1993). We used Cs+ rather than K+ as the extracellular activator cation of the pump because it also blocks K+ conductances. To avoid any possible competition between Na+ and K+/Cs+ at the internal cation binding sites, the pipette solutions were free of K+ and Cs+. Furthermore, any putative voltage-dependent binding of the latter two cations to cytoplasmic binding sites of the Na+-K+ pump (Hansen et al. 1997) is absent under these conditions. Ip, the outward current generated by the Na+-K+-ATPase, was measured as the inward shift of the membrane current upon application of 0.1 mM ouabain, a specific inhibitor of this enzyme (cf. Fig. 1A). This ouabain concentration completely blocked the Na+-K+ pump current under our experimental conditions since a tenfold higher concentration did not cause any further inward shift of the holding current (n = 2; data not shown). The NMDG-based solutions used resembled those previously described by Dobretsov & Stimers (1997), with slight modifications.

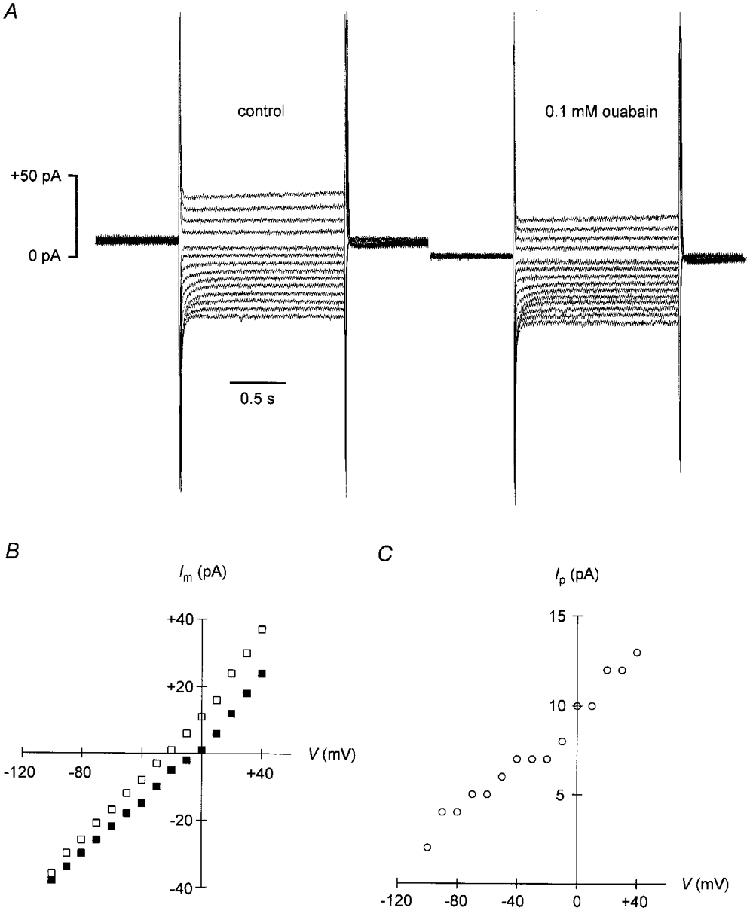

Figure 1. Voltage dependence of Na+-K+ pump current activated by 0.5 mM Na+pip.

A, whole-cell recording from a guinea-pig ventricular myocyte. The patch pipette contained 0.5 mM Na+ and 159.5 mM NMDG+ as the main cation. Current traces in response to voltage steps from zero potential to potentials between −100 and +40 mV in 10 mV increments are displayed. Left panel: control in Na+-free solution containing 20 mM Cs+. Right panel: currents obtained following application of 0.1 mM ouabain. Note the inward shift of the current traces after inhibition of the Na+-K+ pump by ouabain. Cell capacitance: 111 pF. B, steady-state membrane current (Im)-voltage relationships from the data shown in A. □, control in drug-free medium; ▪, currents measured under 0.1 mM ouabain. C, pump current (Ip)-voltage relationship. Data represent the differences between membrane currents recorded in the absence and in the presence of ouabain (shown in B). Note the steep positive slope of the Ip-V curve.

Experimental procedure and electrical measurements

A culture dish containing isolated ventricular myocytes was placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (Diaphot-TMD, Nikon). The cell under study was positioned in the laminar solution flow (0.4 ml min−1) of a multibarrelled, solenoid-operated pipette that allowed rapid exchange of the superfusate (∼1 s). Experiments were conducted in the whole-cell mode of the patch clamp technique (Hamill et al. 1981). Ventricular myocytes were voltage clamped by means of an EPC-8 patch clamp amplifier (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany) connected to a personal computer (386) via 12 bit AD- and DA-converters, respectively. Commercially available software (ISO2, MFK, Niedernhausen, Germany) was used for generation of the voltage protocols and current recording. Membrane currents were low pass filtered at 200 Hz and digitized at 1 kHz.

Patch pipettes were made from borosilicate glass capillaries (GC150TF-10, Clark Electromedical Instruments, Reading, UK). The resistance of the pipettes amounted to 2–4 MΩ when backfilled with the respective pipette solution. Potential differences between the pipette and superfusion solution were nulled immediately before patch formation. Membrane capacitance (Cm) was estimated at a holding potential of 0 mV by a program routine applying ±10 mV voltage ramps or by integration of the capacitative current transient during a voltage step from 0 to −10 mV. Both estimates were almost identical. Mean Cm of the guinea-pig ventricular myocytes used in this study was 103 ± 5 pF (n = 55).

Drugs

Ouabain (Sigma), a specific inhibitor of the Na+-K+ pump, was prepared as a 10 mM stock solution in 10 % ethanol (v/v). Thus, at 0.1 mM ouabain, the concentration used in most experiments, the superfusate contained 0.1 % ethanol which, by itself, had no effect on the membrane current under the present experimental conditions (n = 2; data not shown).

Statistics

Data are presented as means ±s.e.m. and n indicates the number of cells studied. Error bars are shown only when exceeding the size of the symbol. Differences between data points were checked by Student's unpaired t test and considered significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

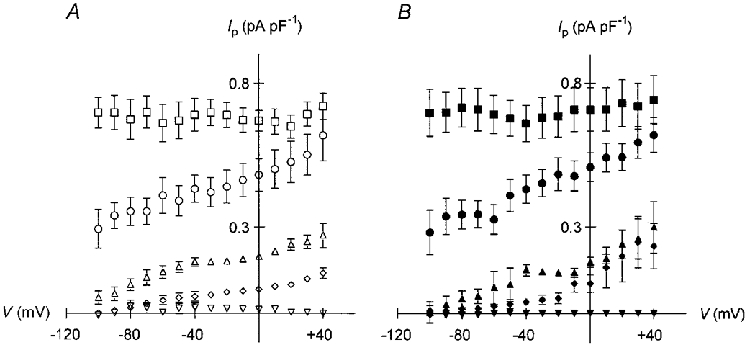

In order to investigate the possible effects of membrane voltage on cytoplasmic Na+ binding to the Na+-K+ pump, experimental conditions were designed to eliminate the voltage dependence of other partial reactions in the pump cycle (cf. Methods for details). Figure 1 illustrates the experimental protocol for the measurement of Ip and the Ip-V relationship. A ventricular myocyte was voltage clamped at 0 mV and internally perfused with a pipette solution containing 0.5 mM Na+ and 159.5 mM NMDG+. When the holding current remained constant, the cell was subjected to 1.5 s voltage steps to potentials between +40 and −100 mV in 10 mV increments at a rate of 0.25 Hz (Fig. 1A, left panel). Afterwards, 0.1 mM ouabain was applied and the same voltage protocol was repeated in the presence of the drug (Fig. 1A, right panel). The steady-state membrane currents in the absence (□) and in the presence (▪) of the cardiac glycoside are plotted as a function of clamp potential in Fig. 1B. The respective difference currents, i.e. the Na+-K+ pump currents, are displayed in Fig. 1C. It is evident from these data that Ip is voltage dependent: its amplitude is small at negative membrane potentials and increasingly larger upon depolarization. The monotonic increase of the Ip-V curve argues for only one voltage-dependent partial reaction in the pump cycle under the chosen experimental conditions (cf. De Weer et al. 1988). Because effects of membrane potential on extracellular ion binding are very unlikely under these conditions, intracellular Na+ binding remains a possible candidate for the voltage-dependent step. Hence, we recorded Ip-V relationships at various concentrations of Na+pip. Figure 2A summarizes data obtained with NMDG-based pipette solution containing 50 mM (□), 5 mM (○), 2 mM (▵), 0.5 mM (⋄) or 0 mM (▿) Na+pip, respectively (n = 4–8). Na+-K+ pump current densities are plotted versus membrane potential. No pump current was observed at zero Na+pip, demonstrating that the cells were reasonably well dialysed via the patch pipette. Increasing [Na+]pip resulted in progressively larger pump currents. At low (≤ 5 mM) [Na+]pipIp was voltage dependent: the pump currents were small at negative membrane potentials and increased with depolarization. The relative Ip activation was clearly stronger at more positive potentials. The voltage dependence of Ip was almost entirely abolished at 50 mM Na+pip, a concentration saturating the internal Na+ binding sites of the cardiac Na+-K+ pump (Nakao & Gadsby, 1989). Analogous experiments with TEA+-based pipette solution produced very similar results, as shown in Fig. 2B (n = 4–7; symbols have the same meaning as in Fig. 2A). Again, there was no Na+-K+ pump current in the absence of Na+pip. Increasing [Na+]pip evoked increasingly larger pump currents. Ip was voltage dependent at 0.5–5 mM Na+pip and voltage independent at 50 mM Na+pip. Once more, the relative activation of Ip by low [Na+]pip became stronger with depolarization.

Figure 2. Ip-V relationships at various [Na+]pip.

Na+-K+ pump currents normalized to cell capacitance are plotted versus membrane potential. A, Ip-V relationships at 0 mM (▿), 0.5 mM (⋄), 2 mM (▵), 5 mM (○), and 50 mM (□) Na+pip in cells dialysed with NMDG+-containing pipette solution (n = 4–8). B, corresponding Ip-V curves for myocytes containing TEA+ as the main cation (n = 4–7). Symbols have the same meaning as in A. Note the absence of Ip in Na+-free pipette solutions and the voltage dependence of Ip at low (< = 5 mM) Na+pip. In contrast, Ip activated by 50 mM Na+pip is voltage insensitive.

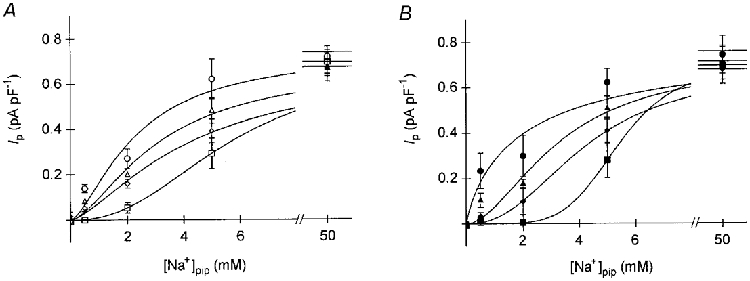

Figure 3A displays the activation of Ip by various [Na+]pip at +40 mV (○), 0 mV (▵), −50 mV (⋄), and −100 mV (□) (n = 4–8). The patch pipette solution contained NMDG+ as the main cation. As can be seen from the figure the Ip density increased with increasing [Na+]pip. At a distinct [Na+]pip depolarization caused a stronger activation of Ip, except at 50 mM Na+pip. The curves fitted to the data obeyed the Hill equation:

| (1) |

where Ip(max) denotes the maximal pump current density, K0.5 represents the [Na+]pip required for half-maximal Ip activation (K0.5 value), and nH is the Hill coefficient. Ip(max) fluctuated between 0.68 and 0.75 pA pF−1. nHvaried between 1.4 and 2.3 and increased with hyperpolarization. The K0.5 value amounted to 5.8 mM Na+pip at −100 mV and decreased to 2.3 mM Na+pip at +40 mV. Thus, the apparent affinity of the cardiac Na+-K+ pump to Na+pip increases with depolarization. Figure 3B shows corresponding data from cells internally perfused with a solution containing TEA+ as the major cation (n = 4–7, symbols have the same meaning as in Fig. 3A). Again, the Ip density increased with larger [Na+]pip and the Ip activation at a distinct [Na+]pip became stronger with depolarization. Ip(max) varied between 0.68 and 0.81 pA pF−1. The Hill coefficient amounted to 0.8 at +40 mV and increased with hyperpolarization to 5.2 at −100 mV. The K0.5 value decreased with depolarization from 5.4 mM Na+pip at −100 mV to 2.1 mM Na+pip at +40 mV. As in cells dialysed with NMDG+, the apparent affinity of the pump towards intracellular Na+ decreased with hyperpolarization, whereas the Hill coefficient increased. The latter finding confirms earlier observations by Goldshlegger et al. (1987) and Or et al. (1996) on proteoliposomes containing Na+-K+-ATPase suggesting that the binding sites of the pump for cytosolic Na+ are differently affected by the membrane potential. However, it is likewise possible to fit the data in Fig. 3A or B by assuming a common Ip(max) value and Hill coefficient for each series of experiments, although the fit is less good.

Figure 3. Activation of Ip by [Na+]pip at various membrane potentials.

Ip activation as a function of [Na+]pip in cardiomyocytes dialysed with NMDG+-containing (A) or TEA+-containing (B) pipette solutions. Activation was measured at +40 mV (circles), 0 mV (triangles), −50 mV (diamonds), and −100 mV (squares) (n = 4–8). The curves fitted to the data points obey the Hill equation (eqn (1)) with the following parameters (for A and B): + 40 mV: K0.5= 2.3 and 2.1 mM Na+pip, Ip(max)= 0.75 and 0.81 pA pF−1, nH= 1.5 and 0.8; 0 mV: K0.5= 3.1 and 3.3 mM Na+pip, Ip(max)= 0.68 and 0.72 pA pF−1, nH= 1.6 and 1.8; −50 mV: K0.5= 4.3 and 4.2 mM Na+pip, Ip(max)= 0.70 and 0.68 pA pF−1, nH= 1.4 and 2.3; −100 mV: K0.5= 5.8 and 5.4 mM Na+pip, Ip(max)= 0.70 and 0.70 pA pF−1, nH= 2.3 and 5.2. r2= 0.984–1.000. Note that K0.5 values increase with hyperpolarization, whereas Ip(max) remains constant.

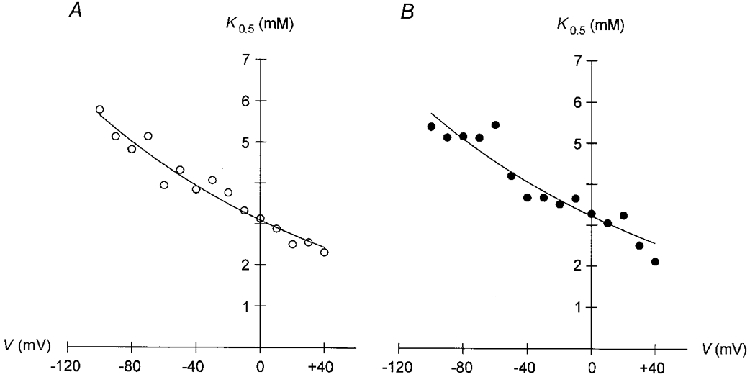

Figure 4 depicts the voltage dependence of the K0.5 values for Ip activation by internal Na+ for myocytes containing either NMDG+ (A) or TEA+ (B) as the main cation. Under both conditions the K0.5 values declined by a factor of ∼2.5 with depolarization from −100 to +40 mV. Correspondingly, the apparent Na+ affinity of the Na+-K+ pump increased by the same factor within this range of membrane potentials. The data in Fig. 4A and B are fitted by the Boltzmann function (cf. Apell, 1989):

| (2) |

where K0.5(V) is the K0.5 value at the membrane potential V and K0.5(V = 0) the K0.5 value at zero potential. F, R and T have their usual meanings. α is a steepness factor and represents the fraction of an elementary charge moving through the membrane dielectric during binding/ translocation of intracellular Na+ ions. α amounted to 0.16 in myocytes internally perfused with NMDG+-containing pipette solution (Fig. 4A) and to 0.15 in cells dialysed with TEA+-containing medium (Fig. 4B). According to Sagar & Rakowski (1994)α is related to δ, the dielectric coefficient, by:

| (3) |

where nHis the Hill coefficient. The dielectric coefficient indicates the mean fraction of membrane potential dissipated between the inner side of the sarcolemma and the Na+ binding sites of the Na+-K+ pump within the membrane. In order to calculate δ a mean Hill coefficient for Na+ binding of 1.7 (the mean value for cells containing NMDG+) or 2.1 (the mean value for myocytes containing TEA+) was used. Thus, δ values amounted to 0.09 and 0.07 for NMDG+- and TEA+-containing cells, respectively.

Figure 4. K0.5 values for Ip activation by Na+pip are voltage dependent.

K0.5 values for activation of Ip by Na+pip in cells containing either NMDG+ (A) or TEA+ (B) are plotted versus membrane potential. In both cases K0.5 values decrease monotonically with depolarization. The fitted curves obey a Boltzmann equation (eqn (2)) with α values of 0.16 for NMDG+ (A) and 0.15 for TEA+ (B). r2= 0.948 (A) and 0.895 (B).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of the present study is that the apparent affinity of the cardiac Na+-K+ pump towards intracellular Na+ is voltage dependent. The observation is in agreement with a preliminary report by Kockskämper & Glitsch (1997) suggesting voltage-dependent binding of cytoplasmic Na+ to the Na+-K+ pump of cultured guinea-pig atrial myocytes. It is, however, in contrast to the conclusion drawn by Nakao & Gadsby (1989) that in Na+-free external media Na+i binding to the Na+-K+ pump of guinea-pig ventricular myocytes is independent of membrane potential. The discrepancy between their findings and ours might be caused by the different composition of the pipette solutions used. While Nakao & Gadsby (1989) employed Cs+-containing internal solutions, ours were devoid of any Cs+ (and K+). Cs+ is known to act as a K+ congener. Both intracellular Cs+ and K+ change the kinetics of the cardiac Na+-K+ pump, for instance by reducing maximal Ip (Kinard & Stimers, 1992) and by decreasing the apparent affinity to cytoplasmic Na+ (Hilgemann et al. 1991; this work, see below). It is conceivable, therefore, that the apparent lack of voltage effects on intracellular Na+ binding to the pump reported by Nakao & Gadsby (1989) may be due to the use of (varying concentrations of) cytoplasmic Cs+. Furthermore, in our opinion, the experimental data presented in their Fig. 7A and C do not exclude a weak voltage dependence of Na+i binding at low [Na+]pip. Using giant membrane patches from guinea-pig ventricular myocytes and experimental conditions not directly comparable to ours (Na+-containing external media; pump currents obtained as difference currents in the presence or absence, respectively, of internal Na+ or ATP), Hilgemann (1994) noted that cytoplasmic Na+ binding to the pump is not strongly electrogenic. As to cell-free Na+-K+-ATPase systems, several earlier reports suggest that binding of Na+ to the (internal) Na+-binding sites of the enzyme might depend on voltage (Goldshlegger et al. 1987; Stürmer et al. 1991; Heyse et al. 1994; Or et al. 1996; for further references, see Rakowski et al. 1997b). Most recently Pintschovius et al. (1999) demonstrated, by direct electrical measurements, electrogenic Na+ binding on the cytoplasmic side of solid-supported membrane fragments containing pig kidney Na+-K+-ATPase.

The solutions used in the experiments described above were designed to avoid possible interference resulting from competition of K+/Cs+ with Na+ for internal cation binding sites of the Na+-K+ pump. In addition, they guaranteed that the known voltage dependence of two steps in the pump cycle did not affect the measurements. These steps are rebinding of extracellular Na+, which affects Na+ release by the pump to the exterior, and binding of extracellular K+ (for further details see Rakowski et al. 1997a,b). In order to prevent voltage-sensitive Na+ release/rebinding the experiments were carried out in Na+-free superfusion media. In addition, the media contained 20 mM Cs+ to saturate the external Cs+/K+-binding sites of the Na+-K+ pump (K0.5 value for Cs+o in Na+-free media at 0 mV ≈ 1.5 mM; cf. Bielen et al. 1993). Using these solutions Ip-V curves at low [Na+]pip increased monotonically with depolarization, indicative of a single voltage-dependent step in the pump cycle (De Weer et al. 1988). Saturation of internal Na+ binding sites at 50 mM Na+pip abolished the voltage dependence of this partial reaction, suggesting that it is located in the Na+ translocation limb. Furthermore, the partial reaction is supposed to occur prior to Na+ release to the exterior which is voltage independent under our experimental conditions. We observed a decrease of the K0.5 value for Ip activation by intracellular Na+ upon depolarization in the entire potential range studied, irrespective of the main internal cation used, NMDG+ or TEA+. The K0.5 value dropped by a factor of ∼2.5 for a 140 mV depolarization. According to Läuger (1991), the voltage dependence of the apparent affinity of the Na+-K+ pump to cytoplasmic Na+ may indicate the existence of a high-field, narrow access channel (ion well) connecting the cytosol with the pump's Na+-binding sites buried in the membrane. Thus, hyperpolarization of the sarcolemma would reduce the local [Na+] at the sites, whereas depolarization would increase local [Na+]. The calculated dielectric coefficients of 0.07–0.09 are similar to the values reported from membrane fragments and proteoliposomes containing Na+-K+-ATPase (Goldshlegger et al. 1987; Wuddel & Apell, 1995; Or et al. 1996) but lower than the corresponding numbers for Na+o rebinding and K+o binding to the pump (see Sagar & Rakowski, 1994). This agrees with the hypothesis that the putative ion well for internal Na+ binding is shallower than those for external Na+ and K+ binding. However, as emphasized by Gadsby and colleagues (Gadsby et al. 1992; Rakowski et al. 1997b), voltage dependence of the apparent affinity of a transporter to a transported ion species does not prove the existence of a high-field, narrow access channel; it can also be explained by the voltage dependence of any other partial reaction in the transport cycle. Still, it seems possible to localize the voltage-dependent step observed in the present study to the Na+ translocation limb of the pump cycle since there is strong evidence that the partial reactions in the K+ limb subsequent to K+o binding are most probably voltage independent (Goldshlegger et al. 1987; Bahinski et al. 1988; Peluffo & Berlin, 1997; see also Rakowski et al. 1997a). Furthermore, earlier studies on cell-free Na+-K+-ATPase systems have also shown that occlusion of internal Na+ is potential independent (Apell et al. 1987; Borlinghaus et al. 1987), whereas the change from the E1 conformation to the E2 conformation of the pump is weakly voltage sensitive (Wuddel & Apell, 1995). Thus our data do not allow us to differentiate between internal Na+ binding to the pump and the E1 → E2 conformational change as the reaction underlying the apparent voltage dependence of cytoplasmic Na+ binding to the pump. They demonstrate, however, that the membrane potential affects a partial reaction prior to Na+ release in the Na+ limb of the Na+-K+ pump cycle.

There are two other points worth noting. First, the maximal Ip densities (at zero potential) measured in the present study under conditions maximally activating Ip are somewhat lower (∼0.75 pA pF−1) than those reported earlier for cardiac cells (≥ 1 pA pF−1; Gadsby et al. 1985; Glitsch et al. 1989). A possible reason is that the latter investigators used K+ or Rb+ as an equipotent external activator of the Na+-K+ pump whereas in the experiments described above the myocytes were superfused with Cs+-containing media. Hermans (1997, pp. 19–20) demonstrated that the maximal Ip density of guinea-pig ventricular cells declines with a decrease in the apparent affinity of the external activator cation species. Since Cs+o is a weaker activator than K+o or Rb+o our data are clearly in line with her observation. Second, our K0.5 values for Ip activation by internal Na+ are lower by a factor of 2–3 than previous estimates (e.g. Nakao & Gadsby, 1989). A possible explanation for this finding is that we used K+/Cs+-free pipette solutions. In contrast, most earlier investigations were conducted in the presence of intracellular K+/Cs+. Since intracellular K+/Cs+ not only inhibits the forward running Na+-K+ pump (Kinard & Stimers, 1992), but also appears to compete with Na+ for cytoplasmic binding sites (Hilgemann et al. 1991; Hermans, 1997, p. 121), the apparent affinity of the pump for intracellular Na+ is expected to increase in the absence of intracellular K+/Cs+. Our results thus underline the importance of an appropriate (ionic) composition of intra- and extracellular solutions, especially with respect to the transported cations, if one aims to investigate a distinct step in the pump cycle. In this regard it is important that the main intracellular cations used in this study, NMDG+ and TEA+, do not markedly interact with the Na+-K+ pump at cytoplasmic sites. There is evidence that TEA+ weakly reduces extracellular K+ binding to the pump by inhibiting K+ entry into the access channel. However, intracellular TEA+ only marginally inhibits Ip (Eckstein-Ludwig et al. 1998). Clearly, because of the rather large ionic diameters of both NMDG+ and TEA+ compared with Na+, K+ or Cs+, competition between these groups of cations for binding to cytoplasmic sites of the pump appears unlikely. Furthermore, since the results presented above are almost identical for NMDG+- and TEA+-containing myocytes, both cation species, although quite different in structure, would have to exert identical effects on the Na+-K+ pump. Thus, it seems reasonable to assume that intracellular NMDG+ and TEA+ do not substantially affect the pump and, consequently, are much better K+ substitutes than Cs+ for our purposes.

In conclusion, we have presented, for the first time in animal cells, conclusive evidence that cytoplasmic Na+ binding to the Na+-K+ pump and/or a subsequent partial reaction prior to Na+ release is voltage dependent. This mechanism may be of physiological relevance for the clearance of Na+ loads during cardiac excitation.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Balzer-Ferrai and U. Müller for their technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, Gl 72/7–1).

References

- Apell H-J. Electrogenic properties of the Na, K pump. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1989;110:103–114. doi: 10.1007/BF01869466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apell H-J, Borlinghaus R, Läuger P. Fast charge translocations associated with partial reactions of the Na, K-pump: II. Microscopic analysis of transient currents. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1987;97:179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF01869221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahinski A, Nakao M, Gadsby DC. Potassium translocation by the Na+/K+ pump is voltage insensitive. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1988;85:3412–3416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielen FV, Glitsch HG, Verdonck F. Dependence of Na+ pump current on external monovalent cations and membrane potential in rabbit cardiac Purkinje cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;442:169–189. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielen FV, Glitsch HG, Verdonck F. Na+ pump current-voltage relationships of rabbit cardiac Purkinje cells in Na+-free solution. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;465:699–714. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlinghaus R, Apell H-J, Läuger P. Fast charge translocations associated with partial reactions of the Na, K-pump: I. Current and voltage transients after photochemical release of ATP. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1987;97:161–178. doi: 10.1007/BF01869220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Weer P, Gadsby DC, Rakowski RF. Voltage dependence of the Na-K pump. Annual Review of Physiology. 1988;50:225–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobretsov M, Stimers JR. Na/K pump current in guinea pig cardiac myocytes and the effect of Na leak. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 1997;8:758–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1997.tb00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein-Ludwig U, Rettinger J, Vasilets LA, Schwarz W. Voltage-dependent inhibition of the Na+, K+ pump by tetraethylammonium. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998;1372:289–300. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Kimura J, Noma A. Voltage dependence of Na/K pump current in isolated heart cells. Nature. 1985;315:63–65. doi: 10.1038/315063a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Nakao M. Steady-state current-voltage relationship of the Na/K pump in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;94:511–537. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.3.511. 10.1085/jgp.94.3.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Nakao M, Bahinski A, Nagel G, Suenson M. Charge movements via the cardiac Na, K-ATPase. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1992;146:111–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glitsch HG, Krahn T, Pusch H. The dependence of sodium pump current on internal Na concentration and membrane potential in cardioballs from sheep Purkinje fibres. Pflügers Archiv. 1989;414:52–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00585626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldshlegger R, Karlish SJD, Rephaeli A, Stein WD. The effect of membrane potential on the mammalian sodium-potassium pump reconstituted into phospholipid vesicles. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;387:331–355. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth F. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen PS, Gray DF, Buhagiar KA, Rasmussen HH. Voltage-dependent inhibition of the Na+-K+ pump by intracellular potassium in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;834:347–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans AN. Ion translocation by the Na+/K+ pump: influence of membrane potential and cardiac glycosides. Acta Biomedica Lovaniensia. 1997;143:1–140. [Google Scholar]

- Heyse S, Wuddel I, Apell H-J, Stürmer W. Partial reactions of the Na, K-ATPase: determination of rate constants. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;104:197–240. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW. Channel-like function of the Na, K pump probed at microsecond resolution in giant membrane patches. Science. 1994;263:1429–1432. doi: 10.1126/science.8128223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Nagel GA, Gadsby DC. Na/K pump current in giant membrane patches excised from ventricular myocytes. In: Kaplan JH, De Weer P, editors. The Sodium Pump: Recent Developments. New York: Rockefeller University Press; 1991. pp. 543–547. [Google Scholar]

- Kinard TA, Stimers JR. Effect of Ki on the Ko dependence of Na/K pump current in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1992;671:458–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb43829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kockskämper J, Glitsch HG. Sodium pump of cultured guinea pig atrial myocytes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;834:354–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kockskämper J, Glitsch HG, Gisselmann G. Comparison of ouabain-sensitive and -insensitive Na/K pumps in HEK293 cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1997;1325:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(96)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafaire AV, Schwarz W. Voltage dependence of the rheogenic Na+/K+ ATPase in the membrane of oocytes of Xenopus laevis. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1986;91:43–51. doi: 10.1007/BF01870213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Läuger P. Electrogenic Ion Pumps. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao M, Gadsby DC. [Na] and [K] dependence of the Na/K pump current-voltage relationship in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;94:539–565. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.3.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Or E, Goldshleger R, Karlish SJD. An effect of voltage on binding of Na+ at the cytoplasmic surface of the Na+-K+ pump. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:2470–2477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluffo RD, Berlin JR. Electrogenic K+ transport by the Na+-K+ pump in rat cardiac ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;501:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.033bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintschovius J, Fendler K, Bamberg E. Charge translocation by the Na+/K+-ATPase investigated on solid supported membranes: cytoplasmic cation binding and release. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:827–836. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski RF, Bezanilla F, De Weer P, Gadsby DC, Holmgren M, Wagg J. Charge translocation by the Na/K pump. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997a;834:231–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski RF, Gadsby DC, De Weer P. Stoichiometry and voltage dependence of the sodium pump in voltage-clamped, internally dialyzed squid giant axon. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;93:903–941. doi: 10.1085/jgp.93.5.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski RF, Gadsby DC, De Weer P. Voltage dependence of the Na/K pump. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1997b;155:105–112. doi: 10.1007/s002329900162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski RF, Vasilets LA, La Tona J, Schwarz W. A negative slope in the current-voltage relationship of the Na+/K+ pump in Xenopus oocytes produced by reduction of external [K+] Journal of Membrane Biology. 1991;121:171–187. doi: 10.1007/BF01870531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar A, Rakowski RF. Access channel model for the voltage dependence of the forward running Na+/K+ pump. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;103:869–893. doi: 10.1085/jgp.103.5.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stürmer W, Bühler R, Apell H-J, Läuger P. Charge translocation by the Na, K-pump: II. Ion binding and release at the extracellular face. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1991;121:163–176. doi: 10.1007/BF01870530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuddel I, Apell H-J. Electrogenicity of the sodium transport pathway in the Na, K-ATPase probed by charge-pulse experiments. Biophysical Journal. 1995;69:909–921. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79965-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]