Abstract

We systematically examined the biophysical properties of ω-conotoxin GVIA-sensitive neuronal N-type channels composed of various combinations of the α1B, α2/δ and β1b subunits in Xenopus oocytes.

Whole-cell recordings demonstrated that coexpression of the β1b subunit decelerated inactivation, whereas the α2/δ accelerated both activation and inactivation, and cancelled the kinetic effects of the β1b. The α2/δ and the β1b controlled voltage dependence of activation differently: the β1b significantly shifted the current-voltage relationship towards the hyperpolarizing direction; however, the α2/δ shifted the relationship only slightly in the depolarizing direction. The extent of voltage-dependent inactivation was modified solely by the β1b.

Unitary currents measured using a cell-attached patch showed stable patterns of opening that were markedly different among subunit combinations in their kinetic parameters. The α2/δ and the β1b subunits also acted antagonistically in regulating gating patterns of unitary N-type channels. Open time was shortened by the α2/δ, while the fraction of long opening was enhanced by the β1b. The α2/δ decreased opening probability (Po), while the β1b increased Po. α1Bα2/δβ1b produced unitary activity with an open time distribution value in between those of α1Bα2/δ and α1Bβ1b. However, both the α2/δ and the β1b subunits reduced the number of null traces.

These results suggest that the auxiliary subunits alone and in combination contribute differently in forming gating apparatuses in the N-type channel, raising the possibility that subunit interaction contributes to the generation of functional diversity of N-type channels in native neuronal preparations also.

Neuronal cells are highly diverse in their physiological properties and morphology, being subcellularly compartmentalized for different neuronal processes. Since voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) operate in many of these processes as indispensable signal transducing molecules, VDCCs are highly diverse in functional and structural characteristics. Multiple types of VDCCs have been recognized on the basis of functional differences (for review see Varadi et al. 1995). Each VDCC type, now mainly categorized using pharmacological tools, displays a wide range of biophysical divergence. N-type Ca2+ channels, distinguished from other types in neurones by a combination of pharmacological parameters such as insensitivity to dihydropyridines (DHPs) and susceptibility to irreversible blockade of ω-conotoxin (ω-CgTx) GVIA (see review by Bean, 1989; Tsien et al. 1991), show a wide variety of inactivation properties (Aosaki & Kasai, 1989; Jones & Marks, 1989; Plummer & Hess, 1991), although the decaying component of high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channel current was originally assigned to the N-type channels in neurones (Fox et al. 1987; Bean, 1989; Tsien et al. 1991). Unitary N-type currents recorded in the cell-attached mode show multiple patterns of opening (Delcour & Tsien, 1993; Rittenhouse & Hess, 1994; Lee & Elmslie, 1999). N-type channels are subjected to further functional modification by neurotransmitters and neuropeptides via association of GTP-binding proteins and phosphorylation (for review see Anwyl, 1991; Dolphin, 1998).

Biochemical and molecular biological studies have allowed us to elucidate structural bases for the functional diversification of VDCCs. It is now accepted that high-voltage-activated channel types are expressed as a complex of the main subunit α1, that is both the essential channel moiety and the receptor for Ca2+ channel antagonists including DHPs and ω-CgTx GVIA, and the auxiliary subunits α2/δ, β, and γ (Campbell et al. 1988; Witcher et al. 1993; Catterall, 1995; Letts et al. 1998). Of the seven distinct genes of high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channel α1 subunits, the α1B, α1A and α1E subunit genes are responsible for single DHP-insensitive non-L-type channels, the N-, P/Q-, and R-types, respectively (Varadi et al. 1995). Functional diversity observed for the N-type channel, therefore, should be due to post-transcriptional modification such as alternative RNA splicing and/or post-translational mechanisms including interaction of the main subunit α1B with the auxiliary subunits, which are capable of modifying Ca2+ channel function of α1 subunits, and contribute to the fine-tuning of Ca2+ channel function.

Multiple gating parameters and expression of VDCCs at the plasma membrane are dramatically modulated by the cytoplasmic β subunits (for review see Varadi et al. 1995; Catterall, 1995), when they are combined with the main subunit α1 in recombinant expression systems. Enhancement of Ca2+ channel activity by the transmembrane auxiliary subunit α2/δ has been demonstrated also in previous recombinant studies, where modulatory effects of the α2/δ on functional properties of VDCCs were not as pronounced as those of β subunits (Mikami et al. 1989; Mori et al. 1991; Singer et al. 1991; De Waard & Campbell, 1995; Qin et al. 1998). While the studies have demonstrated that the α2/δ and β subunits exert prominent modulatory actions on the α1 subunit Ca2+ channels, there still lie significant uncertainties about the specific effects of the auxiliary subunits, which vary among different α1 isoforms, and even among studies on the same α1 subunit (Wakamori et al. 1993, 1994; Jones et al. 1998). The differences in observed effects may partly derive from variations in the effects of four β subunit isoforms that differently modulate gating parameters such as inactivation kinetics (Hullin et al. 1992; Sather et al. 1992; Olcese et al. 1996; Patil et al. 1998) or from usage of different expression systems (Jones et al. 1998). Thus, it is of great necessity to undertake comprehensive examination of modulatory actions elicited by the auxiliary subunits on specific isoforms of the α1 subunit. In this respect, the N-type α1B subunit is an interesting research target, since there have been few studies that systematically explored the effects of the auxiliary subunits on the N-type α1B channels, despite the wide recognition that N-type channels show diverse gating properties in the native system.

In this study we have systematically examined the biophysical properties, at whole-cell and unitary levels, of recombinant N-type α1B currents produced by various combinations of the pore-forming subunit α1B and the two auxiliary subunits α2/δ and β1b in Xenopus oocytes. Several important issues have been addressed. Firstly, the effects of the auxiliary subunits α2/δ and β1b, in combination, on the functional properties of α1 Ca2+ channels, have been compared with the effects of α2/δ and β1b alone. In addition, modulatory action of the auxiliary subunits on the α1B channel function at unitary levels has been characterized carefully, since there has previously only been examination of the effects of the β subunits on unitary L-type α1C currents (Wakamori et al. 1993; Neely et al. 1995), and the effect of α2/δ on unitary α1C currents has been examined for limited gating parameters (Shistik et al. 1995). Thirdly, we compared our results with previous studies, revealing striking differences in the action of the auxiliary subunits between the N-type α1B channel and the L-type channel in modulating the number of functional aspects such as activation and inactivation speeds and voltage dependence of activation. The results presented here demonstrate that the auxiliary subunits alone and in combination modulate gating properties of the N-type α1B channel differently.

METHODS

Construction of full length cDNAs encoding VDCC subunits

The recombinant plasmid pSPBIII carrying the entire protein-coding sequence of the BIII cDNA was constructed using the 7.3 kb Hin dIII-Hin dIII fragment from the pKCRB3 (Fujita et al. 1993) and the Hin dIII-cleaved pSP64AS, a derivative of pSP64 poly(A) (Promega), which had the polylinker sites between Pst I and Sac I deleted, with removal of the Eco RI site, and a new Sal I site introduced. The rat brain Ca2+ channel β1b subunit cDNA was obtained by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A sense oligonucleotide, 5′-GGAGGATCCTCTCCATGGTCCAGAA-3′, and an antisense oligonucleotide, 5′-CCAGGAGTTGGGAATGATAACCACCA-3′, which correspond to nucleotides 50–74 and 2028-2003 of the rat brain β1b subunit (Wakamori et al. 1994), respectively, were used to prime a PCR with cDNA made from rat brain poly(A)+ RNA. The PCR was performed for 35 cycles (94°C for 1 min; 62°C for 2 min; 72°C for 3 min). Reaction products were digested with Bam HI and Hin dIII, and ligated with a 2.9 kb Bam HI-Hin dIII fragment from pBluescript KS(−) to yield pBSRBB. The pSP73 recombinant plasmid pSPRBB carrying the entire coding sequence of the β1b subunit cDNA was constructed using the following fragments: Bam HI-Eco RI (linker attached to Hin dIII) from pBRSBB, ∼0.52 kb Eco RI-Xba I from pRII-2A and 2.5 kb Bam HI-Xba I from pSP73. mRNAs specific for the BIII and for the skeletal muscle α2/δ and brain β1b subunits were synthesized in vitro using Sal I-cleaved pSPCBIII, Sal I-cleaved pSPCA1 (Mikami et al. 1989) and Xba I-cleaved pSPRBB, respectively, as templates. GenBank/EMBL accession numbers are D14157 and L06110 for α1B and β1b, respectively.

cDNA expression and electrophysiological characterization

Adult Xenopus laevis frogs were anaesthetized by immersion in a solution containing 1.5 g l−1 of ethyl m-aminobenzoate (methanesulphonate salt, Tricaine; Sigma) and oocytes were removed surgically. The oocytes were then incubated in Barth's solution containing 1 mg ml−1 collagenase (Type IA; Sigma) for 30 min. Dissociated oocytes were carefully rinsed with Barth's solution. While still anaesthetized, the frogs were decapitated, and the brain and spinal cord destroyed. The procedures were approved by institutional animal use committees.

Whole-cell currents were recorded at room temperature (22°C) using a two-microelectrode voltage-clamp amplifier (Axoclamp 2A, Axon Instruments) in a solution of the following composition (mM): 40 Ba2+, 50 N-methyl-D-glucamine, 2 K+ and 5 Hepes (pH was adjusted to 7.3 with methansulphonic acid). The external solution containing 4 mM Ba2+ as charge carrier was made by adding sucrose to maintain osmolarity. Currents were filtered at 1–2 kHz, and sampled at 1–10 kHz. Leakage subtraction was accomplished with a -P/4 protocol.

The amount of cRNAs injected was lowered to give maximal current amplitudes of approximately 1 μA, in order to measure the α1B currents produced by different subunit combinations under better voltage control and to increase the probability of obtaining a single α1B channel in the patch pipette. Xenopus oocytes were injected with 50 nl mixtures of the following combinations of RNAs specific for each subunit, and incubated for 2–3 days as described previously (Mori et al. 1991): α1Bα2/δβ1b; 1 ng μl−1α1B RNA, 1 ng μl−1α2/δ RNA and 0.33 ng μl−1β1 RNA: α1Bβ1b; 1 ng μl−1α1B RNA and 0.33 ng μl−1β1 RNA: α1Bα2/δ; 2 ng μl−1α1B RNA and 2 ng μl−1α2/δ RNA: α1B; 10 ng μl−1α1B RNA. The maximal current amplitudes were 1.36 ± 0.12 μA (n = 21) for α1Bα2/δβ1b, 1.23 ± 0.07 μA (n = 53) for α1Bα2/δ, 1.09 ± 0.09 μA (n = 37) for α1Bβ1b and 0.65 ± 0.06 μA (n = 17) for α1B.

The vitelline membrane of oocytes used in single-channel current measurements was removed as described previously (Wakamori et al. 1993). To zero the membrane potential for the cell-attached patch recording, oocytes were bathed in a depolarizing solution of the following composition (mM): 100 KCl, 10 EGTA and 10 Hepes (pH 7.3 with KOH). The resistance of Sylgard (Dow-Corning)-coated and fire-polished pipettes was 4–8 MΩ when filled with the pipette solution, containing (mM): 110 BaCl2 and 10 Hepes (pH 7.4 with Ba(OH)2). Junction potentials were not corrected in our experiments. Currents were measured with an Axoclamp 200A patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments), filtered at 1 kHz, and sampled at 10 kHz. Voltage steps were given at 3 s intervals. Single-channel records were corrected for linear leakage and capacitive currents by subtracting averaged blank records. Data were analysed with pCLAMP 6.0 software (Axon Instruments). In Fig. 7, single-channel data were analysed only from patches which showed more than 2000 single openings without simultaneous openings, because the probability that these patches contain two or more independent channels is less than 0.0001 even if the open probability is as low as 0.01 (Colquhoun & Hawkes, 1995). Mean open and closed times were calculated by fitting the open and closed time histograms to exponential decay functions using a maximum likelihood estimate. Open probability (Po) was calculated by excluding the first and last shut times.

Figure 7. Kinetic analysis of open and closed times for the N-type channels composed of various subunit combinations.

Open and closed time distributions of the channels for α1B alone (A), α1Bα2/δ (B), α1Bβ1b (C) and α1Bα2/δβ1b (D) were plotted from the single-channel recording in a cell-attached configuration shown in Fig. 6. The open times of each N-type channel are fitted by a single exponential function for α1Bα2/δ and the sum of two exponential functions for the other three subunit combinations. The closed times of each N-type channel are fitted by the sum of two exponential functions. The limitation of the fit is set at 25 ms. Numbers in the histograms represents open or closed times and their relative area is in parentheses. Subscripts o, c, f and s for the time constants represent open, closed, fast and slow, respectively.

ω-CgTx GVIA and ω-Aga IVA were obtained from the Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan). Bay K 8644 was purchased from Research Biochemicals International.

RESULTS

ω-CgTx GVIA-sensitive N-type Ca2+ channel current produced by the α1B subunit

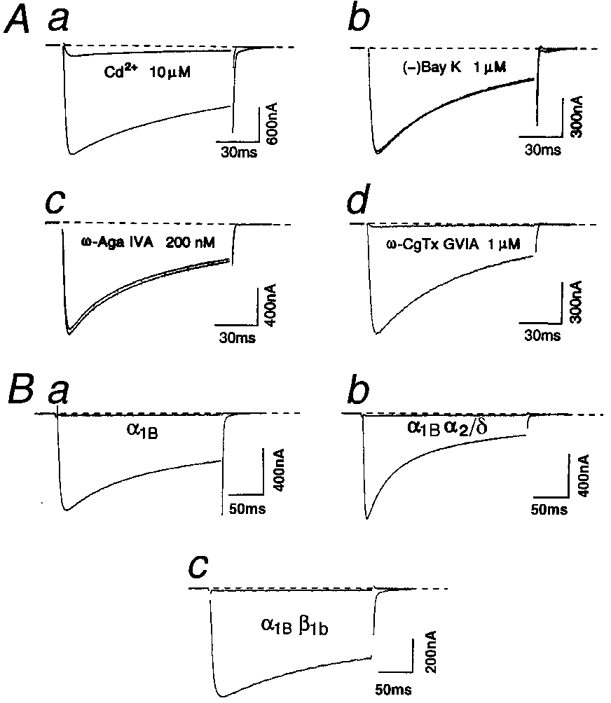

We first established the pharmacological profiles of the recombinant α1B channels. Messenger RNA (mRNA) specific for the α1B subunit was first injected into Xenopus oocytes together with the mRNAs specific for the α2/δ and the β1b subunits. Whole-cell currents in oocytes were measured using the two-microelectrode voltage-clamp method in the external solution containing 4 mM Ba2+ as a charge carrier (or 40 mM Ba2+ for α1B alone), and were tested for the sensitivity to various Ca2+ channel blockers. Ba2+ current induced by step depolarization to 0 mV from a holding potential (Vh) of −100 mV was blocked by 10 μm Cd2+ (Fig. 1Aa). Neither the DHP agonist (−)Bay K 8644 (Fig. 1Ab) nor the antagonist (+)PN200-110 (data not shown) at a concentration of 1 μm altered the α1Bα2/δβ1b current. Further, DHPs caused no apparent shift of the current-voltage (I-V) relationship. Ba2+ currents generated by the human heart L-type α1C channel (Wakamori et al. 1993) were increased several times by 1 μm (−)Bay K 8644 and were inhibited by 1 μm (+)PN200-110 to 38 ± 5 % (n = 4) of control currents (data not shown). ω-Aga IVA (200 nm), which reduced the P/Q-type α1A (BI) current by about 50 % (Sather et al. 1992), had little or no effect on the α1B current (Fig. 1Ac). ω-CgTx GVIA (1 μm), which selectively blocks the N-type channel in native preparations (Bean, 1989; Tsien et al. 1991), irreversibly reduced the α1B Ba2+ current to 4 ± 3 % (n = 10) of the control value (Fig. 1Ad). To determine whether the formation of the ω-CgTx GVIA binding site on the α1B subunit is dependent on the α2/δ and the β1b subunits, we tested the effect of deleting these subunits from the N-type complex on ω-CgTx GVIA sensitivity. Ba2+ currents produced by the combinations of subunits, α1B alone, α1Bα2/δ or α1Bβ1b, were all inhibited irreversibly by ω-CgTx GVIA (Fig. 1B). This indicates that the recombinant α1B channels of possible subunit combinations with the auxiliary subunits can all be categorized as ω-CgTx GVIA-sensitive N-type channels. Deletion of auxiliary subunits did not induce an apparent change in ω-CgTx GVIA sensitivity, retaining the IC50 around 100 nm (data not shown). Taken together, in line with previous results obtained using myotubes from mdg mutant mice (Fujita et al. 1993), the α1B subunit is sufficient and necessary to direct the formation of the ω-CgTx GVIA-sensitive N-type Ca2+ channel in recombinant systems, supporting the finding that the α1B subunit has the ω-CgTx GVIA binding site (Ellinor et al. 1994). In the present experiments, the possibility that the α1B subunit forms functional Ca2+ channels together with the endogenously expressed α2/δ and β subunits in oocytes (Tareilus et al. 1997) cannot be excluded. If this is the case, however, the endogenous α2/δ and β subunits may exert modulatory effects different from the exogenously introduced auxiliary subunits (see below). Also, it cannot be excluded that the exogenous α2/δ and β1b subunits additionally associate with the α1B subunit already complexed with endogenous α2/δ and β subunits.

Figure 1. Pharmacological properties of the recombinant N-type channels.

A, effects of Ca2+ channel antagonists and toxins on recombinant N-type channels expressed with the α1B, the α2/δ and the β1b subunits in Xenopus oocytes. Examples of Ba2+ currents elicited by 115 ms depolarizing pulses to 10 mV from a holding potential (Vh) of −100 mV before and during exposure to 10 μm Cd2+ (a), 1 μm (−)Bay K 8644 (b), 200 nmω-Aga IVA (c) and 1 μmω-CgTx GVIA (d). Ba2+ currents were recorded just before (control) and 3 min after application of each agent. External Ba2+ concentration was 4 mM. Cytochrome C (0.1 mg ml−1), to saturate non-specific peptide binding, was added to the external solution in the experiments of c and d. B, inhibition of N-type channels, composed of various subunit combinations, by ω-CgTx GVIA. a, oocyte was treated with 1 μmω-CgTx GVIA in the external solution containing 4 mM Ba2+ for 3 min between the records measured in 40 mM Ba2+ before application and after washing out of ω-CgTx GVIA. Currents were elicited by 250 ms step pulses to 20 mV from a Vh of −100 mV. b and c, oocyte was treated with 1 μmω-CgTx GVIA in the external solution containing 4 mM Ba2+ for 3 min. Step depolarizations were applied to 10 mV (b) and 0 mV (c) from a Vh of −100 mV in the external solution containing 4 mM Ba2+. Small capacity currents remaining after subtraction have been blanked.

Voltage dependence of activation and inactivation of recombinant N-type currents

Whole-cell currents, generated by the recombinant N-type channels of four different combinations of subunits, α1B alone, α1Bα2/δ, α1Bβ1b and α1Bα2/δβ1b, were measured using 40 mM Ba2+ as a charge carrier. Step depolarization to potentials > −20 mV from a Vh of −100 mV elicited inward Ba2+ currents, which reached maximum around 20 mV (21.2 ± 1.2 mV, n = 17), in oocytes implanted with α1B alone, and a further increase of step depolarization reduced the Ba2+ currents (Fig. 2A). Coexpression of the β1b with the α1B subunit caused a significant shift of the current-voltage (I-V) relationship in a negative direction (by 8 mV) at the peak (13.6 ± 0.9 mV, n = 37, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2C). In contrast, coexpression of the α2/δ subunit shifted the I-V relationship slightly in the positive direction (23.4 ± 0.6 mV at the maximum, n = 53) (Fig. 2B). Even in the presence of the α2/δ subunit, however, the β subunit significantly shifted the voltage, producing a peak inward current in the hyperpolarizing direction (by 5 mV; 16.3 ± 1.1 mV at the maximum, n = 21, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Effects of the α2/δ and the β1b subunits on the macroscopic α1B currents.

The α1B channels were expressed alone (A) or together with the α2/δ subunit (B), the β1b subunit (C), or both the α2/δ and the β1b subunits (D). Ba2+ currents, which were evoked with 40 mM external Ba2+ by step depolarizations to voltages between −20 and 50 mV (A, C and D) and between −10 and 60 mV (B) in 10 mV intervals from a Vh of −100 mV, are shown on slow (left panel) and fast (middle panel) scales. Small capacity currents remaining after subtraction have been blanked. The corresponding peak current-voltage relationships are shown in the right panel. Curves were drawn by an interpolation process.

The effects of the auxiliary subunits on the extent of voltage-dependent inactivation were examined using a conventional double-pulse protocol as indicated in Fig. 3. With respect to the voltage range of inactivation, four different combinations of the α1B subunit with the auxiliary subunits were divided into two groups: α1B alone and α1Bα2/δ, and α1Bβ1b and α1Bα2/δβ1b. Inactivation of N-type channels of the first group was almost fully prevented at a membrane potential of −40 mV. Half-inactivation potentials and slope factors were −11.0 mV and 7.1 mV (n = 5), respectively, for α1B alone, and −13.3 mV and 6.7 mV (n = 5), respectively, for α1Bα2/δ. Voltage-dependent inactivation of the N-type channels of the second group had a much broader range of voltage dependence than the first group. Half-inactivation potentials and slope factors were −36.4 mV and 17.0 mV (n = 5), respectively, for α1Bβ1b, and −33.7 mV and 13.0 mV (n = 5), respectively, for α1Bα2/δβ1b. Qualitatively similar β subunit effects on the extent of voltage dependence of activation and inactivation were observed for β1a and β3 (data not shown). The data indicate that mainly the β subunits modify the extent of the voltage-dependent inactivation of the N-type channel.

Figure 3. The β1b but not the α2/δ subunit changes the voltage-dependent inactivation properties of the α1B channels.

Voltage-dependent inactivation of the α1B channels expressed alone or together with the α2/δ subunit and/or the β1b subunit is compared. A, voltage-dependent inactivation was studied using a conventional double-pulse protocol. a, inactivation was induced by 5 s potential displacements (conditioning pulse) from −100 to 40 mV with increments of 10 mV immediately before 200 ms test pulses to 20 mV. b and c, Ba2+ currents were evoked by test pulses to 20 mV followed by 5 s conditioning pulses at the indicated potential in oocytes injected with α1Bα2/δ (b) and α1Bβ1b (c). B, the amplitudes of Ba2+ currents elicited by test pulses after conditioning pulses were normalized to the amplitude at a conditioning pulse potential of −100 mV and plotted against the conditioning potential. Data points were fitted with a smooth curve derived from the Boltzmann equation I/Imax= (1 + exp(Vm - V0.5)/k)−1 where Vm is prepulse potential, V0.5 is half-inactivation potential, and k is a slope factor. The values of V0.5 and k are −10.9 mV and 7.34 mV for α1B alone (○), −13.4 mV and 6.74 mV for α1Bα2/δ (•), −35.2 mV and 15.86 mV for α1Bβ1b (▵), and −33.4 mV and 12.44 mV for α1Bα2/δβ1b (▴), respectively. Vertical bars show means ±s.e.m. of 5 measurements if they are larger than symbols.

Kinetic analysis of the N-type α1B channels

In a previous study (Wakamori et al. 1994), we have shown that the kinetics of the α1E (BII α1) subunit is quite differently modulated by the α2/δ and the β1b subunits, compared with the L-type α1C subunits. To investigate whether variation in subunit combination generates the kinetic diversity in another non-L-type, N-type α1B, currents, we quantified time dependence of activation and inactivation by measuring the time to peak (tp) and decay time constants (τd) at various test potentials. tp was potential dependent so that the current onset became faster as the test depolarization was increased over the voltage range between −10 and 40 mV (Fig. 4A). The differences among activation rates of Ba2+ currents produced by different subunit combinations were more prominent at lower voltages. Throughout the voltages tested, addition of the α2/δ subunit to the combinations accelerated activation, and tp values for both subunit combinations of α1Bα2/δ and α1Bα2/δβ1b were significantly smaller than those for α1B alone and α1Bβ1b. However, the effect of the β1b subunit was clear only at the test potential of 0 mV.

Figure 4. Influence of the α2/δ and the β1b subunits on activation (time to peak) (A) and inactivation (time constant) (B) kinetics.

The α1B channels were expressed alone or together with the α2/δ subunit and/or β1b subunit as indicated. The experimental conditions used were the same as in Fig. 2. Data points represent means ±s.e.m. of 6–17 measurements. ○, α1B alone; •, α1Bα2/δ; ▵, α1Bβ1b; and ▴, α1Bα2/δβ1b. Vertical bars show means ±s.e.m. if they are larger than symbols.

Inactivation kinetics has been proposed as an important biophysical criterion in distinguishing multiple types of VDCCs coexisting in single neurones (Bean, 1989), although it is now widely acknowledged that N-type currents are composed of both decaying and sustained components (Plummer & Hess, 1991; Fujita et al. 1993). Since some of the 1.2 s traces of α1Bα2/δ currents were unable to be fitted by a single exponential function, the current decay during 300 ms from the onset of the step pulses was fitted by a single exponential function. The time constants > 300 ms therefore may not be accurate for α1B, α1Bα2/δ and α1Bα2/δβ1b currents, while the time constants for α1Bβ1b currents calculated from the 300 ms decay are similar to those from 1.2 s current traces, since the decay was always well fitted by a single exponential function. Average values of inactivation time constants were plotted against membrane potentials between −20 and 40 mV. The recombinant N-type channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes showed a U-shape voltage dependence of inactivation rates. The current decay first became rapid with increasing depolarization, and slowed at more depolarized potentials, after reaching a minimum in the voltage ranges between 0 and 20 mV, where the Ba2+ currents gained maximum amplitude. Although the phenomenon often reflects a Ca2+-dependent inactivation mechanism, this is not the case with the present study. We used Ba2+, which is known to be less effective than Ca2+ in producing inactivation. Furthermore, inactivation did not change or even became slightly faster, when the amplitude of the current was reduced to half by changing the Ba2+ concentration to 4 mM (data not shown). The U-shape voltage dependence of inactivation has been reported for the native N-type channel (Fox et al. 1987; Jones & Marks, 1989) and recombinant N-type channel expressed in mammalian cell lines (Patil et al. 1998; Wakamori et al. 1998).

As shown in Fig. 4, coexpression of the β1b subunit decelerated inactivation kinetics of the α1B currents at potentials > 0 mV. This is in contrast to the previous findings that the β subunit accelerates inactivation of the L-type α1C and α1S channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Castellano et al. 1993; Wakamori et al. 1993) and mammalian cultured cells (Varadi et al. 1991; Welling et al. 1993). On the other hand, the α2/δ subunit accelerated inactivation of the α1B channel for the membrane potentials tested. The modulatory effects of the coexpression of both the α2/δ and the β1b subunits are more complicated. The combination of the α2/δ and the β1b subunits affects the inactivation rate towards the direction of acceleration more than the coexpression of the α2/δ subunit alone at membrane potentials of < 10 mV. Similar action of the β subunits, enhancing the effect of the α2/δ subunit, was observed in the rabbit brain α1E (BII) channel (Wakamori et al. 1994). However, the two auxiliary subunits function antagonistically at potentials > 10 mV, and α1Bα2/δβ1b shows voltage dependence of inactivation similar to that of α1B alone. At a membrane potential of 20 mV, inactivation time constants were 214.5 ± 14.1 ms (n = 14), 143.9 ± 8.6 ms (n = 26), 477.3 ± 25.5 ms (n = 20) and 247.9 ± 19.2 ms (n = 21) for α1B alone, α1Bα2/δ, α1Bβ1b and α1Bα2/δβ1b, respectively.

Single-channel analyses of the N-type α1B channels

To further resolve the functional differences among the N-type VDCC complexes with distinct subunit compositions, we also examined unitary currents in cell-attached patches containing single N-type channels using 110 mM Ba2+ as a charge carrier. Figure 5A shows the representative unitary activity of N-type channels with various subunit combinations, in response to 150 ms test depolarizations to 10 and 30 mV from a Vh of −100 mV. Single-channel openings were observed at membrane potentials > −10 mV but were relatively rare at a membrane potential of 10 mV. However, the channel openings became more frequent at 30 mV. Channel openings were more clustered near the beginning of the test pulse at 30 mV than at 10 mV, indicating that unitary N-type activity is dominated by inactivation with the increase in membrane potential. This observation is consistent with the voltage-dependent acceleration of inactivation at membrane potentials < 20 mV in the whole-cell experiments (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4, the α2/δ subunit accelerated activation of the N-type Ca2+ channel. However, since we must take into account that, for whole-cell currents, the activation speed is affected by inactivation, we analysed the distribution of latencies to first channel opening in a cell-attached mode. The first latencies at 20 mV were fitted by a single exponential function with a time constant of 17.7 ± 3.8 ms (n = 4) for α1B alone, 10.7 ± 2.0 ms (n = 7) for α1Bα2/δ, 10.5 ± 2.8 ms (n = 7) for α1Bβ1b and 5.5 ± 1.1 ms (n = 5) for α1Bα2/δβ1b. A significant effect on activation rate was observed in α1Bα2/δβ1b. At a membrane potential of 20 mV, the mean current amplitude was −0.63 ± 0.03 pA (n = 5), −0.63 ± 0.02 pA (n = 8), −0.64 ± 0.06 pA (n = 5) and −0.60 ± 0.04 pA (n = 6) for α1B alone, α1Bα2/δ, α1Bβ1b and α1Bα2/δβ1b, respectively. The difference of unitary current amplitude at each membrane potential is not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Plots of unitary current amplitude against test potentials yielded unitary conductance of 16.3 ± 0.2 pS (n = 5), 16.6 ± 1.2 pS (n = 8), 15.6 ± 0.7 pS (n = 5) and 17.3 ± 0.7 pS (n = 6) for α1B alone, α1Bα2/δ, α1Bβ1b and α1Bα2/δβ1b, respectively. This single channel conductance is compatible with the previously published values obtained from native preparations (Aosaki & Kasai, 1989; Elmslie, 1997) and recombinant expression systems (Fujita et al. 1993; Wakamori et al. 1998). Thus, the ion permeation pathway of N-type channels is not susceptible to influence by the auxiliary subunits.

Figure 5. Unitary current-voltage relationship for the recombinant N-type channel expressed with the α1B, the α2/δ and the β1b subunits in Xenopus oocytes.

A, three consecutive representative sweeps, recorded in a cell-attached configuration from oocytes injected with cRNA specific to α1B alone (a), α1Bα2/δ (b), α1Bβ1b (c) or α1Bα2/δβ1b (d), are shown. The indicated test depolarization of 150 ms duration was applied every 3 s from a Vh of −100 mV. The pipette solution contained 110 mM Ba2+. Arrowheads indicate when the test depolarizations began and ended. B, unitary current-voltage relationship. Each point represents mean ±s.e.m. of 5–7 patches. Data were fitted by a linear regression with slopes of 16.3, 16.6, 15.6 and 17.3 pS for α1B alone (○), α1Bα2/δ (•), α1Bβ1b (▵) and α1Bα2/δβ1b (▴), respectively. Data points represent the mean of 5–8 measurements. The inset shows the amplitude histogram for the data illustrated in Ad. The test depolarization was 10 mV.

Examples of unitary currents in consecutive sweeps recorded at 20 mV from patches containing a single N-type channel are shown in Fig. 6. Recombinant N-type channels of four different subunit combinations displayed distinct patterns of unitary activities in oocytes. Unitary currents produced by α1B alone were characterized by infrequent openings separated by long closures. Opening probability (Po) was 0.24 ± 0.06 (n = 5). The null pattern that extends for more than 10 consecutive sweeps was not exceptional for this subunit combination, and was found in 39 ± 5 % (n = 5) of total sweeps at 20 mV. Coexpression of the α2/δ subunit (α1Bα2/δ) decreased the null sweeps (18 ± 3 %, n = 5). α2/δ dramatically increased the event number, but short openings were generated characteristically. In consequence, Po was 0.12 ± 0.02 (n = 5). The effect of combining the β1b subunit with the α1B subunit (α1Bβ1b) on Po was more prominent than the combination with the α2/δ subunit. α1Bβ1b showed strikingly prolonged open times and increased Po (0.41 ± 0.08, n = 5). The β1b subunit slightly decreased the fraction of null sweeps (28 ± 3 %, n = 5). The auxiliary subunits (α1Bα2/δβ1b) antagonized each other with respect to Po (0.25 ± 0.04, n = 5), but they co-operated with each other in decreasing the occurrence of null sweeps during the single-channel measurements (9 ± 2 %, n = 5).

Figure 6. Different unitary activity of the recombinant N-type channel expressed with the α1B, the α2/δ and the β1b subunits.

Unitary activity of the N-type channel, expressed with α1B subunit alone (A), α1Bα2/δ (B), α1Bβ1b (C) and α1Bα2/δβ1b (D), were recorded in a cell-attached configuration. The step pulses to 20 mV for 150 ms were applied every 3 s from a Vh of −100 mV. Sixteen consecutive, leak-subtracted current traces are shown. The experimental conditions used were the same as in Fig. 5 unless specified otherwise.

To quantitatively demonstrate these striking kinetic differences among the unitary currents produced by N-type channels of different subunit combinations, the open time and closed time histograms (Fig. 7) were calculated from the recordings in Fig. 6 and summarized in Table 1. The auxiliary subunits transformed gating patterns of unitary N-type currents. Coexpression of the α2/δ subunit converted the open time distribution best fitted by two exponential functions (Fig. 7A, α1B alone) into one that is best fitted by a single exponential function (Fig. 7B, α1Bα2/δ). However, unitary N-type currents generated by α1B alone and α1Bα2/δ have similar closed time constants. The relative areas of the closed time constants were different between the two subunit combinations. In contrast to the α2/δ subunit, the relative area of τos was increased by the β1b subunit (Fig. 7C). Comparison of the open and closed time distributions of α1Bα2/δβ1b with those of α1Bα2/δ or α1Bβ1b revealed that effects of the α2/δ and the β1b subunits were more dramatic as the third subunit was added to the combination. When the β1b subunit was regarded as the third subunit, the second long openings appeared. This influence of the β1b on the unitary N-type current was different from that exerted in the absence of the α2/δ subunit, in which the two open time constants themselves were not as affected. On the other hand, the presence of the α2/δ subunit as the third subunit decreased τos with no change in the relative area. Thus, the α2/δ and the β1b alone and together converted unitary N-type currents into different forms of gating, defined by different open time constants.

Table 1.

Regulation of open and closed times by auxiliary subunits

| Open | Closed | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel | No. of cells | τof (ms) | (%) | τos (ms) | (%) | τcf (ms) | (%) | τcs (ms) | (%) |

| α1B | 6 | 0.62 ± 0.11 | 81 ± 6 | 2.13 ± 0.52 | 19 ± 6 | 0.69 ± 0.16 | 50 ± 6 | 7.68 ± 1.27 | 50 ± 6 |

| α1Bα2/δ | 7 | 0.59 ± 0.08 | – | – | – | 1.01 ± 0.09 | 39 ± 3* | 6.25 ± 0.72 | 61 ± 3* |

| α1Bα1b | 6 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 52 ± 9* | 2.79 ± 0.25 | 48 ± 9* | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 63 ± 4 | 4.77 ± 1.20 | 37 ± 4 |

| α1Bα2/δβ1b | 11 | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 58 ± 4* | 1.38 ± 0.14 | 42 ± 4* | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 64 ± 4 | 3.90 ± 0.36* | 36 ± 4 |

Test potential was 20 mV. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m.

P < 0.01 vs.α1B, Student's t test.

In contrast to unitary N-type activity in frog sympathetic neurones (Delcour & Tsien, 1993; Lee & Elmslie, 1999) and rat superior cervical ganglion (SCG) neurones (Rittenhouse & Hess, 1994), transition between different patterns of openings was so extremely rare that no abrupt transition occurred within the sweep and only a type of switch which occurred during intervals between test pulses was observed. As shown in Fig. 6D, we found in a patch from an oocyte expressing the α1B, the α2/δ and the β1b subunits that a pattern with frequent opening may switch to a pattern with only a few scattered events (the seventh trace from the top) and again back to the original pattern. This was the sole apparent conversion of opening pattern of the 600 sweeps recorded from the patch. In an oocyte coexpressing the α1B and the β1b subunits, the ‘long’ opening pattern that is typical for α1Bβ1b was also converted into an opening pattern with much fewer events. On a single occasion, stable unitary activity with the ‘long’ opening pattern was observed in the oocyte coinjected with mRNAs specific to the α1B, the α2/δ and the β1b subunits, which suggests that the patch probably contained a α1Bβ1b complex.

The ensemble averages of unitary N-type currents produced by different subunit combinations showed time dependence of inactivation qualitatively similar to those of whole-cell N-type currents (Fig. 8). This excludes the possibility that alternation in N-type current kinetics at the whole-cell level by coexpression of the auxiliary subunits results from the contamination of currents via other types of channels such as Ca2+-activated Cl− channel. We observed that β1a and β3 elicit qualitatively similar effects on the N-type α1B current also at the single-channel level (data not shown).

Figure 8. Ensemble average currents of the unitary N-type channels and their curve fitting.

Ensemble currents, which were evoked every 5 s by 450 ms step depolarization to 40 mV from a Vh of −100 mV, are the average of 100 for α1B alone (A), 100 for α1Bα2/δ (B), 75 for α1Bβ1b (C) and 50 individual sweeps for α1Bα2/δβ1b (D). Recording electrodes contained at least 2, 4, 3 and 3 channels for α1B alone, α1Bα2/δ, α1Bβ1b and α1Bα2/δβ1b, respectively. Decay components of the ensemble average current are fitted by a single exponential function with a time constant of 146.1 ms (A), 96.9 ms (B), 335.4 ms (C) and 140.0 ms (D).

DISCUSSION

The auxiliary subunits α2/δ and β1b differently modulate N-type Ca2+ channel function: comparisons of modulation of α1B channel with that of other α1 isoforms

In the present investigation, we have demonstrated functional divergence among N-type Ca2+ channels of various subunit combinations due to the difference between the auxiliary subunits, in functional effects. In both whole-cell and single-channel recordings, antagonistic relationships between the α2/δ and the β1b subunits were revealed in regulating multiple gating parameters of the N-type Ca2+ channel. Similar effects on the α1B channels were observed for the β1a and the β3 subunits expressed in oocytes (Y. Mori & M. Wakmori, unpublished results). Thus, the auxiliary subunits alone and in combination affect differently the gating apparatuses in the N-type channel complex, which suggests a possible involvement of auxiliary subunit association in generating functional diversity of N-type channels in native neuronal preparations.

From the multiplicity of time constants of gating parameters, it can be easily recognized that an activation cascade of N-type channels is composed of multiple closed, open, and/or inactivated states. In addition, our results suggest that respective states and transitions among the states in the cascade are affected differently by the auxiliary subunits. Since we observed prominent effects of the α2/δ and the β1b alone on open and closed time distributions at certain voltages but only marginal effects on activation kinetics of N-type currents elicited by voltage steps from hyperpolarizing hold potentials to depolarizing test potentials, it is possible that the final transition prior to opening of the channel is more profoundly affected by the α2/δ and the β1b than the initial rate-limiting voltage-dependent transition between closed states in the activation cascade. More interestingly, the fraction of null traces is reduced in unitary recordings from oocytes expressing α1Bα2/δ, α1Bβ1b and α1Bα2/δβ1b compared with those expressing α1B alone. This observation is consistent with the idea that the auxiliary subunits shift equilibrium towards active states (modes) from inactive null states (modes) by stabilizing the former relative to the latter states. Alternatively, association of the auxiliary subunits may destabilize the formation of the N-type α1B channel-G-protein complex so that the channel leaves the ‘reluctant’ mode to sojourns in the ‘willing’ mode for a longer period (Anwyl, 1991).

The present study allows an interesting comparison between the effects of the auxiliary subunits on the gating of the N-type α1B channel and on gating of other classes of α1 channels, particularly L-types. The action of auxiliary subunits on the kinetics of the α1B current is particularly different from that observed for the L-type α1S and α1C currents expressed heterologously in Xenopus oocytes or in mammalian cultured cells. Both activation and inactivation of α1S- and α1C-type currents were in general accelerated by the β subunits (Varadi et al. 1991; Castellano et al. 1993; Wakamori et al. 1993; Welling et al. 1993; Neely et al. 1995), while inactivation of the α1B current was decelerated by the coexpression of the β1b subunit. The kinetic slowing of inactivation by the β1b subunit was observed also for the P/Q-type α1A and R-type α1E channels, which belong to the same non-L-type gene subfamily as α1B, in Xenopus oocytes (Wakamori et al. 1994; De Waard & Campbell, 1995) and in COS-7 cells (Stephens et al. 1997), whereas inactivation of the α1E channel expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK 293) cells was accelerated by β1b (Jones et al. 1998). Lack of major effects on activation kinetics by the β1b subunit at the whole-cell level was also demonstrated for the α1E subunit (Olcese et al. 1996; Jones et al. 1998). On the other hand, the shift of voltage dependence of activation and inactivation towards hyperpolarizing potentials is a modulatory effect of the β subunit that is general among the α1 isoforms.

Compared with the β subunit, little attention has been paid to the modulatory effects of the α2/δ subunit on α1 subunit channels, and effects of α2/δ were not found to be as extensive (De Waard & Campbell, 1995). Furthermore, reported effects of α2/δ vary widely. Previous studies on α1E channels showed shifts of voltage dependence of inactivation and activation by α2/δ towards depolarizing potentials (Wakamori et al. 1994; Stephens et al. 1997), whereas the shift was towards the opposite, hyperpolarizing direction in α1C channels (Felix et al. 1997). The α2/δ subunit accelerates both current activation and decay of the α1C and α1E channels in the Xenopus oocyte system (Singer et al. 1991; Wakamori et al. 1994; Qin et al. 1998) and those of α1E in COS-7 cells (Stephens et al. 1997), as was seen in the N-type α1B channels in our studies using oocytes. However, the α2/δ subunit showed no significant effects on kinetic properties of the same α1B and α1E channels expressed in the different expression system, HEK cells (Brust et al. 1993; Jones et al. 1998). The accelerating effect of α2/δ on inactivation of the α1A channel in oocyte (Felix et al. 1997), and α1C channels in CHO cells (Welling et al. 1993) and oocytes (Tomlinson et al. 1993), showed dependence on coexpression of β. Co-operative action of α2/δ and β was observed in the acceleration of inactivation of α1E (Qin et al. 1998) and α1C channels (Singer et al. 1991), similar to that of the α1B channel at membrane potentials of < 10 mV. By contrast, in determining voltage dependence of activation of non-L-type α1B and α1E channels, α2/δ and β acted antagonistically (Wakamori et al. 1994; Qin et al. 1998).

In our single-channel studies, the auxiliary subunits α2/δ and β1b alone and in combination converted N-type α1B channels into different forms of unitary gating with distinct τo values. The α2/δ subunit eliminated τos and increased the relative area of τcs, and thereby decreased Po. By contrast, the β1b subunit increased the relative area of τos, and thereby augmented Po. Similar effects of β1b and β2a on unitary L-type α1C currents were demonstrated in previous reports (Wakamori et al. 1993; Neely et al. 1995; Shistik et al. 1995). α2/δ and β1b are antagonistic in regulating τos. τos of α1Bα2/δβ1b is significantly less than that of α1Bβ1b. The results suggest that modes of gating are encoded in the interaction with auxiliary subunits but not only intrinsically in the N-type α1B subunit. Moreover, significant diversity in opening patterns of single N-type channels in native tissues may partly derive from the ability of α2/δ and β1b alone and together creating totally different gating modes in the α1B subunit.

Thus, the L-type and non-L-type channels are distinct in responding to multiple aspects of the α2/δ and β action, including modulation of activation and inactivation speeds by the subunit and shift of voltage dependence of activities by the α2/δ subunit. These differences in the α2/δ and the β subunit effects can be proposed as important parameters other than DHP sensitivity to functionally differentiate the two main subfamilies of high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels.

Subunit composition and functional diversity of native N-type channels

Recent biochemical studies revealed that the N-type VDCC complexes in native neuronal tissues (McEnery et al. 1991; Witcher et al. 1993) are similar but distinct from the skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel/DHP receptor, which is known to be a complex of α1, α2/δ, β, and γ subunits with a stoichiometry ratio of 1 : 1 : 1 : 1 (Campbell et al. 1988). A different isoform of the γ subunit (γ2: encoded by the stargazer gene) interacts with brain Ca2+ channels (Letts et al. 1998). In addition, purification of the N-type channels with an α1B subunit-specific monoclonal antibody showed the association of β1b, β3 and β4 subunits, whereas the α1S subunit of the skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel appears to associate exclusively with the β1a subunit (Scott et al. 1996). Interestingly, it has been reported by Ahlijanian et al. (1990) that monoclonal antibodies raised to the skeletal muscle α2 immunoprecipitated only 6–13 % of the brain ω-CgTx GVIA binding sites in the rabbit brain. This suggests that part of N-type channels may contain brain-specific α2 subunit isoforms that are not recognized by the monoclonal antibodies to the skeletal muscle isoform. In fact, there are clear differences in the immunohistochemical localization among the constituent subunits of the N-type channels in the brain. The immunoreactivity of the α1B-specific antibody is predominantly located in both apical and basal dendrite shafts and punctuates synaptic structures upon dendrites, the staining having an uneven and patchy appearance (Westenbroek et al. 1992). On the other hand, the density of the α2 subunit is greatest near the base of major dendrites and soma, and the staining does not have a punctate appearance expected for presynaptic terminals (Ahlijanian et al. 1990). These differences altogether impose a complex structural view on the N-type channel that is distinct from what has been conceived through the biochemical analyses of the skeletal muscle L-type channel; the N-type complex is constituted from subpopulations that are heterogeneous in the subunit composition rather than a homogeneous population. Respective isoforms of the auxiliary subunits complexed with the α1B may affect gating parameters differently, as demonstrated in the previous studies for the β subunit with other α1 subunits (Hullin et al. 1992; Sather et al. 1992; Olcese et al. 1996; Patil et al. 1998). Thus, diversity in gating behaviour of N-type channels may represent a heterogeneous population of the N-type channel complexes.

Distinct gating patterns of single N-type channels have been reported in frog sympathetic neurones (Delcour & Tsien, 1993) and in rat SCG neurones (Rittenhouse & Hess, 1994), where three gating modes with Po≈ 0.05, 0.3 and 0.6, and two modes with Po < 0.3 and ≈ 0.4 have been respectively described. However, Elmslie (1997) has raised a possibility that other DHP-insensitive types such as ‘novel’ frog E-class (Ef) channels were misidentified as N-types in the earlier single-channel studies using frog sympathetic neurones (Delcour & Tsien, 1993), while unitary activity of re-evaluated N-type channels in the same preparation also showed a wide variety of Po ranging from 0.1 to 0.8 at 40 mV (Lee & Elmslie, 1999). In the present study, we observed that the unitary N-type currents in the same patch showed characteristic kinetic properties without apparent mode shifts, for more than 30 min (600 stimulations) in the oocyte system. Furthermore, neither a statistically significant difference in unitary current amplitude among the four subunit combinations at a given membrane potential between −10 and 40 mV, nor a sudden amplitude change was observed in any subunit combination, in contrast to the change of unitary current amplitude that accompanies mode shifts in the native preparations (Delcour & Tsien, 1993; Rittenhouse & Hess, 1994). It is therefore unlikely that different gating modes observed in native preparations represent distinct subunit combinations: α1B alone, α1Bα2/δ, α1Bβ1b and α1Bα2/δβ1b subunits, the Po values of which are 0.24, 0.12, 0.41 and 0.25, respectively. In fact, the association of the β subunit with the α1 subunit is so tight as to resist being washed off from the α1 attached to the hybridization membrane during epitope mapping of the β subunit-binding site (Pragnell et al. 1994), although on the assumption of such a model, mode shifts should occur through the association and dissociation of α1B and the auxiliary subunits. Association/dissociation of G-proteins is unlikely to convert gating modes of unitary activity, since it has recently been reported that G-protein modulation of N-type Ca2+ channels may not involve mode shifts (Carabelli et al. 1996; Patil et al. 1996; Elmslie, 1997). Thus, evidence that supports the modal conversion of single N-type channel gating from the molecular point of view has yet to be presented.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Professor Keiji Imoto and Professor Arnold Schwartz for their support and encouragement. This work was supported by research grants to M. W. and Y. M. from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, and in part by research grants from the Yamanouchi Foundation and the Uehara Memorial Foundation. G. M. is currently the recipient of the J. Bolyai Fellowship.

References

- Ahlijanian MK, Westenbroek RE, Catterall WA. Subunit structure and localization of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels in mammalian brain, spinal cord and retina. Neuron. 1990;4:819–832. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90135-3. 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwyl R. Modulation of vertebrate neuronal calcium channels by transmitters. Brain Research Reviews. 1991;16:265–281. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(91)90010-6. 10.1016/0165-0173(91)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aosaki T, Kasai H. Characterization of two kinds of high-voltage-activated Ca-channel currents in chick sensory neurons. Differential sensitivity to dihydropyridines and ω-conotoxin GVIA. Pflügers Archiv. 1989;414:150–156. doi: 10.1007/BF00580957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP. Classes of calcium channels in vertebrate cells. Annual Review of Physiology. 1989;51:367–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brust PF, Simerson S, McCue AF, Deal CR, Schoonmaker S, Williams ME, Velicelebi G, Johnson EC, Harpold MM, Ellis SB. Human neuronal voltage-dependent calcium channels: studies on subunit structure and role in channel assembly. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1089–1102. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90004-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KP, Leung AT, Sharp AH. The biochemistry and molecular biology of the dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel. Trends in Neurosciences. 1988;11:425–430. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabelli V, Lovallo M, Magnelli V, Zucker H, Carbone E. Voltage-dependent modulation of single N-type Ca2+ channel kinetics by receptor agonists in IMR32 cells. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:2144–2154. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79780-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano A, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Perez-Reyes E. Cloning and expression of a third calcium channel β subunit. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:3450–3455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Structure and function of voltage-gated ion channels. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1995;64:493–531. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Hawkes AG. The principles of the stochastic interpretation of ion-channel mechanisms. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single Channel Recording. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 397–482. [Google Scholar]

- Delcour AH, Tsien RW. Altered prevalence of gating modes in neurotransmitter inhibition of N-type calcium channels. Science. 1993;259:980–984. doi: 10.1126/science.8094902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waard M, Campbell KP. Subunit regulation of the neuronal α1A Ca2+ channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;485:619–634. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC. Mechanisms of modulation of voltage-dependent calcium channels by G proteins. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;506:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.003bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinor PT, Zhang J-F, Randall AD, Horne WA, Tsien RW. Structural determinants of the blockade of N-type calcium channels by a peptide neurotoxin. Nature. 1994;372:272–275. doi: 10.1038/372272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS. Identification of the single channels that underlie the N-type and L-type calcium currents in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:2658–2668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02658.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix R, Gurnett CA, De Waard M, Campbell KP. Dissection of functional domains of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel α2δ subunit. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:6884–6891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-06884.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AP, Nowycky MC, Tsien RW. Kinetic and pharmacological properties distinguishing three types of calcium currents in chick sensory neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;394:149–172. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Mynlieff M, Dirksen RT, Kim MS, Niidome T, Nakai J, Friedrich T, Iwabe N, Miyata T, Furuichi T, Furutama D, Mikoshiba K, Mori Y, Beam KG. Primary structure and functional expression of the ω-conotoxin-sensitive N-type calcium channel from rabbit brain. Neuron. 1993;10:585–598. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90162-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hullin R, Singer-Lahat D, Freichel M, Biel M, Dascal N, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V. Calcium channel β subunit heterogeneity: functional expression of cloned cDNA from heart, aorta and brain. EMBO Journal. 1992;11:885–890. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LP, Wei SK, Yue DT. Mechanism of auxiliary subunit modulation of neuronal α1E calcium channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;112:125–143. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SW, Marks TN. Calcium currents in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. II. Inactivation. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;94:160–182. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Elmslie KS. Gating of single N-type calcium channels recorded from bullfrog sympathetic neurons. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:111–124. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letts VA, Felix R, Biddlecome GH, Arikkath J, Mahaffey CL, Valenzuela A, Bartlett FS, II, Mori Y, Campbell KP. The mouse stargazer gene encodes a neuronal Ca2+-channel γ subunit. Nature Genetics. 1998;19:340–347. doi: 10.1038/1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEnery MW, Snowman AM, Sharp AH, Adams ME, Snyder SH. Purified ω-conotoxin GVIA receptor of rat brain resembles a dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type calcium channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:11095–11099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami A, Imoto K, Tanabe T, Niidome T, Mori Y, Takeshima H, Narumiya S, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression of the cardiac dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel. Nature. 1989;340:230–233. doi: 10.1038/340230a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y, Friedrich T, Kim MS, Mikami A, Nakai J, Ruth P, Bosse E, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K, Imoto K, Tanabe T, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression from complementary DNA of a brain calcium channel. Nature. 1991;350:398–402. doi: 10.1038/350398a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely A, Olcese R, Baldelli P, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Stefani E. Dual activation of the cardiac Ca2+ channel α1C-subunit and its modulation by the β-subunit. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:C732–740. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.3.C732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcese R, Neely A, Qin N, Wei X, Birnbaumer L, Stefani E. Coupling between charge movement and pore opening in vertebrate neuronal α1E calcium channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:675–686. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil PG, Brody DL, Yue DT. Preferential closed-state inactivation of neuronal calcium channels. Neuron. 1998;20:1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil PG, de Leon M, Reed RR, Dubel S, Snutch TP, Yue DT. Elementary events underlying voltage-dependent G-protein inhibition of N-type calcium channels. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:2509–2521. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79444-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer MR, Hess P. Reversible uncoupling of inactivation in N-type calcium channels. Nature. 1991;351:657–659. doi: 10.1038/351657a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pragnell M, De Waard M, Mori Y, Tanabe T, Snutch TP, Campbell KP. Calcium channel β-subunit binds to a conserved motif in the I-II cytoplasmic linker of the α1-subunit. Nature. 1994;368:67–70. doi: 10.1038/368067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin N, Olcese R, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Modulation of human neuronal α1E-type calcium channel by α2δ-subunit. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C1324–1331. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.5.C1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittenhouse AR, Hess P. Microscopic heterogeneity in unitary N-type calcium currents in rat sympathetic neurons. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;474:87–99. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather WA, Tanabe T, Zhang J-F, Mori Y, Adams ME, Tsien RW. Distinctive biophysical and pharmacological properties of class A (BI) calcium channel α1 subunits. Neuron. 1992;11:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90185-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott VE, De Waard M, Liu H, Gurnett CA, Venzke DP, Lennon VA, Campbell KP. β subunit heterogeneity in N-type Ca2+ channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:3207–3212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shistik E, Ivanina T, Puri T, Hosey M, Dascal N. Ca2+ current enhancement by α2/δ and β subunits in Xenopus oocytes: contribution of changes in channel gating and α1 protein level. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;489:55–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer D, Biel M, Lotan I, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F, Dascal N. The roles of the subunits in the function of the calcium channel. Science. 1991;253:1553–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1716787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens GJ, Page KM, Burley JR, Berrow NS, Dolphin AC. Functional expression of rat brain cloned α1E calcium channels in COS-7 cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1997;433:523–53. doi: 10.1007/s004240050308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tareilus E, Roux M, Qin N, Olcese R, Zhou J, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. A Xenopus oocyte β subunit: evidence for a role in the assembly/expression of voltage-gated calcium channels that is separate from its role as a regulatory subunit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:1703–1708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson WJ, Stea A, Bourinet E, Charnet P, Nargeot J, Snutch TP. Functional properties of a neuronal class C L-type calcium channel. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1117–1126. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90006-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RW, Ellinor PT, Horne WA. Molecular diversity of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1991;12:349–354. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90595-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadi G, Lory P, Schultz D, Varadi M, Schwartz A. Acceleration of activation and inactivation by the β subunit of the skeletal muscle calcium channel. Nature. 1991;352:159–162. doi: 10.1038/352159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadi G, Mori Y, Mikala G, Schwartz A. Molecular determinants of Ca2+ channel function and drug action. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1995;16:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88977-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamori M, Mikala G, Schwartz A, Yatani A. Single-channel analysis of a cloned human heart L-type Ca2+ channel α1 subunit and the effects of a cardiac β subunit. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1993;196:1170–1176. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamori M, Niidome T, Furutama D, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K, Fujita Y, Tanaka I, Katayama K, Yatani A, Schwartz A, Mori Y. Distinctive functional properties of the neuronal BII (class E) calcium channel. Receptors and Channels. 1994;2:303–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamori M, Strobeck M, Niidome T, Teramoto T, Imoto K, Mori Y. Functional characterization of ion permeation pathway in the N-type Ca2+ channel. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:622–634. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welling A, Bosse E, Cavaliè A, Bottlender R, Ludwig A, Nastainczyk W, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F. Stable co-expression of calcium channel α1, β and α2/δ subunits in a somatic cell line. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;471:749–765. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenbroek RE, Hell JW, Warner C, Dubel SJ, Snutch TP, Catterall WA. Biochemical properties and subcellular distribution of an N-type calcium channel α1 subunit. Neuron. 1992;9:1099–1115. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90069-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witcher DR, De Waard M, Sakamoto J, Franzini-Armstrong C, Pragnell M, Kahl SD, Campbell KP. Subunit identification and reconstitution of the N-type Ca2+ channel complex purified from brain. Science. 1993;261:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.8392754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]