Abstract

The existence of a non-negligible steady-state (‘window’) component of the low threshold, T-type Ca2+current (IT) and an appropriately large ratio of IT to ILeak conductance (i.e. gT/gLeak) have been shown to underlie a novel form of intrinsic bistability that is present in about 15 % of thalamocortical (TC) neurones.

In the present experiments, the dynamic clamp technique was used to introduce into mammalian TC neurones in vitro either an artificial, i.e. computer-generated, IT in order to enhance endogenous IT, or an artificial inward ILeak to decrease endogenous ILeak. Using this method, we were able to investigate directly whether the majority of TC neurones appear non-bistable because their intrinsic ionic membrane properties are essentially different (i.e. presence of a negligible IT‘window’ component), or simply because they possess a gT or gLeak conductance that is insufficiently large or small, respectively.

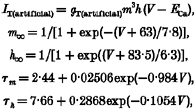

The validity of the dynamic clamp arrangement and the accuracy of artificial IT were confirmed by (i) recreating the low threshold calcium potential (LTCP) with artificial IT following its block by Ni2+ (0.5–1 mM), and (ii) blocking endogenous LTCPs with an artificial outward IT.

Augmentation of endogenous IT by an artificial analog or introduction of an artificial inward ILeak transformed all non-bistable TC neurones to bistable cells that expressed the full array of bistability-mediated behaviours, i.e. input signal amplification, slow oscillatory activity and membrane potential bistability.

These results demonstrate the existence of a non-negligible IT‘window’ component in all TC neurones and suggest that rather than being a novel group of neurones, bistable cells are merely representative of an interesting region of dynamical modes in the (gT, gLeak) parameter space that may be expressed under certain physiological or pathological conditions by all TC neurones and other types of excitable cells that possess an IT‘window’ component with similar biophysical properties.

The primary contribution of the low threshold, transient Ca2+ current, IT (Huguenard, 1996; Perez-Reyes et al. 1998; Bean & McDonough, 1998), to the subthreshold electrical activity of central neurones has long been considered to be the low threshold Ca2+ potential (LTCP) (Llinás & Yarom, 1981; Jahnsen & Llinás, 1984; Deschênes et al. 1984; Friedman & Gutnick, 1987; McCormick & Pape, 1990a; Crunelli & Leresche, 1991; Fraser & MacVicar, 1991; Jeanmonod et al. 1996). In a small group (15 %) of thalamocortical (TC) neurones, however, IT is also responsible for an intrinsic bistability (Williams et al. 1997a; Turner et al. 1997) that is manifest as: (i) input signal amplification, where responses to small current steps or synaptic potentials can be amplified in both the voltage and time domain when neurones are held in a membrane potential region centred around −60 mV, (ii) slow (0.1–1 Hz) oscillations with unusual plateau-like waveforms that differ substantially from conventional δ oscillations, and (iii) in the absence of the hyperpolarization-activated inward current, Ih, membrane potential bistability, where two resting membrane potentials separated by up to 30 mV can exist for the same values of DC current and can be ‘switched’ between by appropriate voltage perturbations (Williams et al. 1997a).

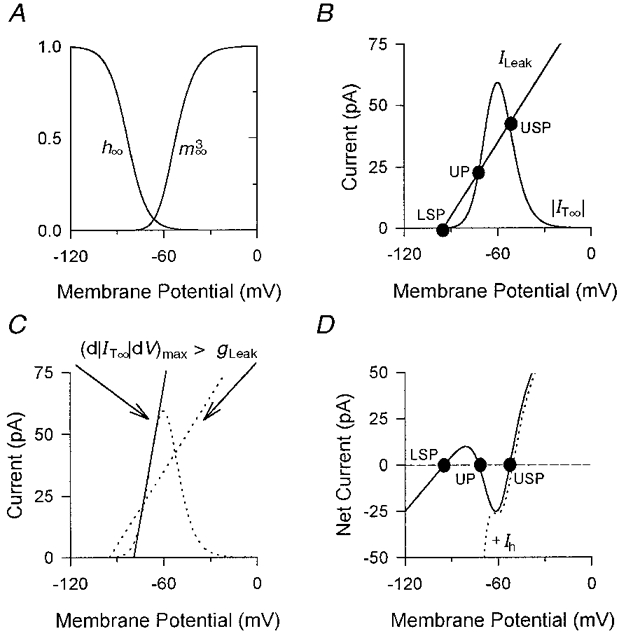

The origin of this intrinsic bistability has been shown to involve an interaction between the steady-state (‘window’) component of IT, IT∞, and the leak current, ILeak (Tóth et al. 1996; Williams et al. 1997a). In particular, bistability can exist for some value of injected DC current if, and only if, the maximal gradient, with respect to membrane potential (V), of the absolute magnitude of IT∞ exceeds the leak conductance, gLeak, i.e. (d|IT∞|/dV)max > gLeak (Fig. 1) (Williams et al. 1997a). In terms of maximal conductances, the above inequality can be written as gT/gLeak > 1/[d(Θ|V- ET|)/dV]max, where gT is the maximal conductance of IT, Θ the product of its steady-state inactivation and the nth power of activation, and ET the reversal potential of IT. Therefore, any neurone that expresses a T-type Ca2+ current that meets this simple condition should exhibit some form of bistability-mediated phenomena as described above. In particular, the reason why the majority of TC neurones do not display such behaviours is clearly due to either the presence of a fundamentally different IT, which exhibits negligible overlap between its steady-state activation and inactivation curves, or simply an insufficiently large gT or excessively large gLeak.

Figure 1. Biophysical mechanism underlying intrinsic bistability.

A, steady-state activation (m∞3) and inactivation (h∞) curves of IT (Tóth et al. 1996; Williams et al. 1997a). IT∞ exists as the result of an area of overlap between the two curves. B, plot of |IT∞| and ILeakvs. membrane potential showing the three points where the net current is zero (USP, upper stable point; LSP, lower stable point; UP, unstable point) (see D for further details). C, same plot as in B showing the tangent (d|IT∞|/dV)max to IT∞ as a continuous line. D, plot of net current (IT∞+ILeak, continuous line; IT∞+ILeak+ Ih, dotted line) vs. membrane potential. If gLeak is smaller than (d|IT∞|/dV)max then in the absence of Ih and for a range of DC currents there will exist three points at which the net current is zero. The upper and lower equilibrium points are stable attractors (USP and LSP) whilst the remaining equilibrium point is unstable (UP). Thus, transient, hyperpolarizing voltage deviations elicited from USP that do not reach UP will return normally to USP, whereas voltage excursions that cross UP will cause a further hyperpolarization towards LSP due to a net outward current. The membrane potential is prevented from remaining at LSP by the activation of Ih (dashed line in D). In D, the dotted line indicating the net current in the presence of Ih has been slightly offset to the right for clarity.

In this study, in order to assess whether normally non-bistable TC neurones are endowed with the basic properties to become bistable, a dynamic clamp system (Sharp et al. 1993) was used to introduce either an artificial IT in order to enhance endogenous IT, or an artificial inward ILeak thus presenting a means to decrease the endogenous ILeak. Using this technique, we have been able to establish that bistability-mediated activities can be unmasked in any TC neurone by solely making adjustments to the ratio gT/gLeak. In conjunction with previous findings (Williams et al. 1997a), this demonstrates in all TC neurones the presence of a non-negligible IT∞ whose functional expression may be brought about by enhancements of IT (cf. Chung et al. 1993; Tsakiridou et al. 1995) or reductions of ILeak (cf. McCormick & Prince, 1987; McCormick & VonKrosigk, 1992; Steriade et al. 1994) that underlie certain physiological and pathological conditions (McCormick, 1992; Jeanmonod et al. 1996). Some of these results have been published in preliminary form (Hughes et al. 1998; Cope et al. 1998).

METHODS

Slice preparation and recording solutions

Male Wistar rats (150–200 g) were deeply anaesthestized (1.5 % halothane) and killed by decapitation. Adult cats of either sex (1–1.5 kg) were deeply anaesthetized with a mixture of O2 and NO2 (2:1) and 1 % halothane. A wide craniotomy was performed and the meninges were removed. The animals were killed by a coronal cut at the level of the inferior colliculus, and, following transection of the optic tracts, the brain was removed. The preparation and maintenance of rat and cat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) slices were as described previously (Williams et al. 1996, 1997a). Slices (400–450 μm) were perfused with a warmed (35 ± 1°C) continuously oxygenated (95 % O2, 5 % CO2) medium containing (mM): NaCl, 134; KCl, 2; KH2PO4, 1.25; MgSO4, 1; CaCl2, 2; NaHCO3, 16; glucose, 10; 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, 0.02; dl-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid, 0.1; bicuculline methiodide, 0.03; and P-(3-aminopropyl)-P-diethoxymethyl-phosphinic acid, 0.5. When NiCl2 (0.5–1 mM) was added to the recording medium, PO43- and SO42- were replaced with Cl−, and in some slices 4-(N-ethyl-N-phenylamino)-1,2-dimethyl-6-(methylamino)-pyrimidinium chloride (ZD 7288) (300 μm) was used to block Ih (Williams et al. 1997b).

Sharp microelectrode recording and data analysis

Impaled neurones were identified as TC neurones by the presence of a robust LTCP on release from hyperpolarization, and strong inward and outward rectification (Williams et al. 1996; Turner et al. 1997). Intracellular recordings, using the current clamp technique, were performed with standard or thin-walled glass microelectrodes filled with 1 M potassium acetate (resistance: 80–120 MΩ and 30–50 MΩ, respectively) and connected to an Axoclamp-2A amplifier (Axon Instruments). Voltage and current records were stored either on a Biologic DAT recorder (IntraCel, Royston, UK) or directly on the hard disk of an IBM compatible personal computer and later analysed using pCLAMP (Axon Instruments). The apparent input resistance (RN) was calculated from small voltage responses evoked at −60 mV. The apparent leak conductance (gLeak) was taken as the reciprocal of RN. Numerical results are expressed in the text as means ±s.e.m. and statistical significance was tested (P = 5 %) using Student's t test.

The dynamic clamp

The dynamic clamp system (Sharp et al. 1993) was implemented using a personal computer connected to a DigiData 1200A interface (Axon Instruments). Membrane potential (V) was sampled, and artificial current was updated, at 10–50 kHz. The equations used to describe artificial IT are:

|

where ECa= 180 mV is the Ca2+ reversal potential and gT(artificial) is the maximal conductance (Tóth et al. 1996; Williams et al. 1997a). The activation and inactivation variables, m and h, obey the differential equation:

where y =m or h. Accordingly, y∞ represents the steady-state values of the activation and inactivation variables (m∞ and h∞), and τy the corresponding time constants (τm and τh). The equation used to describe artificial ILeak is:

where EK (=−95 mV) is the K+ reversal potential and gLeak(artificial) is the maximal conductance.

For experiments with ILeak, gLeak(artificial) was changed until a satisfactory reproduction (see below) of the bistability-related phenomena observed in the naturally bistable TC neurones was achieved. A similar approach was used for gT(artificial). Neither EK and ECa were allowed to change. The ratio of gT(artificial) or gLeak(artificial) to gLeak, in addition to their absolute values, is quoted to aid comparison of the artificial current used in different neurones and experimental conditions. Except for the experiments involving the reproduction and elimination of LTCPs, the values of gT(artificial)/gLeak and gLeak(artificial)/gLeak given in the results indicate the amount of current needed for bistability-mediated behaviours similar to those observed in normally bistable TC neurones to become clearly apparent (i.e. an inflection point in the charging pattern, appearance of two stable membrane potentials, etc.). These values may not represent, therefore, the minimum amount of current needed to bring about bistability.

RESULTS

The experiments presented here are based on a total of 61 neurones recorded in the rat (n = 7) and cat (n = 54) LGN, whose electrophysiological properties (RN= 143 ± 16 MΩ, resting V =−64 ± 1 mV, n = 36) under control conditions were similar to those of morphologically identified TC neurones (Williams et al. 1996, 1997a). The dynamic clamp arrangement was initially tested by either (i) using artificial IT to recreate LTCPs following their block by Ni2+ (0.5–1 mM) (gT(artificial)= 67.14 ± 11.05 nS; gT(artificial)/gLeak= 7.66 ± 1.16, n = 15) (Fig. 2A), or (ii) introducing an artificial outward IT to block LTCPs (gT(artificial)=−90.87 ± 9.20 nS; gT(artificial)/gLeak=−11.08 ± 1.76, n = 23) (Fig. 2B). In both cases, the results confirmed the accuracy of the system.

Figure 2. Recreation and elimination of LTCPs using artificial IT.

A, dynamic clamp (gT(artificial)= 45 nS) recreation of LTCPs following their block by Ni2+ (0.5 mM) in a cat TC neurone. Tetrodotoxin (1 μm) and ZD7288 (300 μm) were present in the recording medium. B, elimination of LTCPs using an artificial outward IT (gT(artificial)=−25 nS) in a rat TC neurone. In A and B, control and dynamic clamp traces were obtained using identical current steps, respectively. In this and all subsequent figures (i) action potential amplitude has been truncated for clarity; (ii) current traces labelled IT or ILeak show the artificial currents injected by the dynamic clamp system; and (iii) unlabelled current traces indicate the current steps. In B, the current calibration applies to both the current steps and artificial IT.

Input signal amplification

Voltage domain

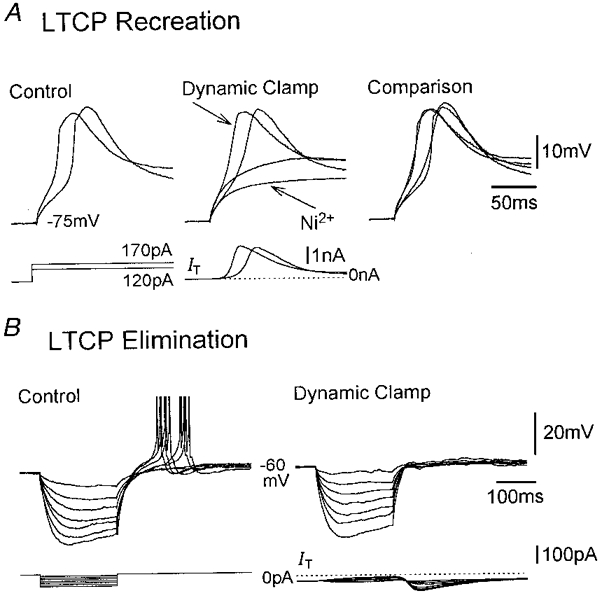

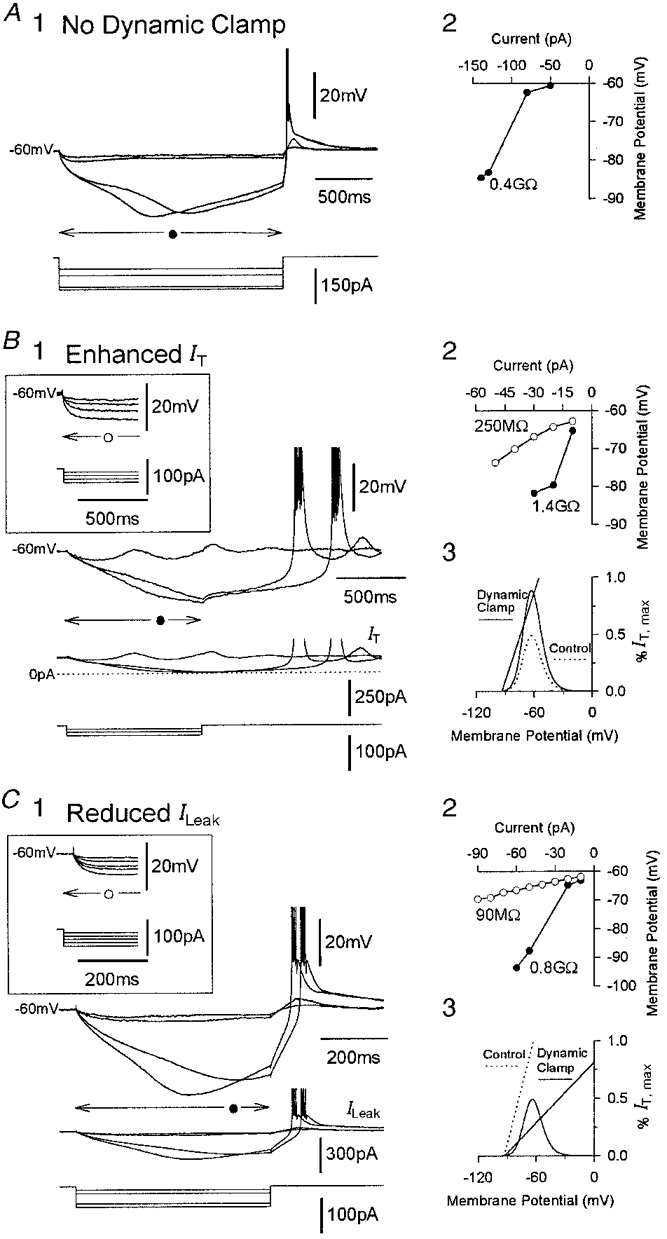

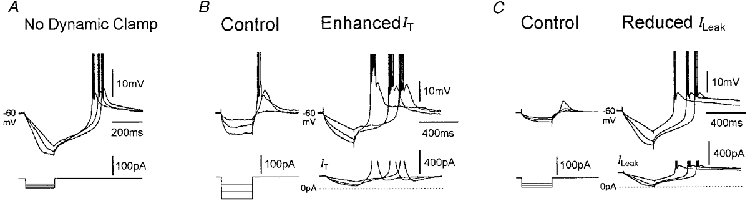

In all TC neurones that under control conditions showed no evidence of any bistability-mediated behaviours, but exhibited a passive response to small negative current steps (< 100 pA) elicited from −60 mV (Fig. 3B 1 and C1, insets), either addition of artificial IT {fontsize ({fontsize gT(artificial)= 53.5 ± 10.48 nS; gT(artificial)/gLeak= 8.87 ± 1.10, n = 10); or artificial inward ILeak (gLeak(artificial)=−5.58 ± 1.08 nS; gLeak(artificial)/gLeak=−0.59 ± 0.06, {fontsize n = 6) led to behaviour characterized by (i) large amplitude voltage deviations in response to small negative current steps, such that their RN was in the gigaohm range, and (ii) an accompanying time-dependent increase in RN and non-exponential charging pattern (Fig. 3B and C). These input signal amplification properties were typical of those observed in a small proportion of previously recorded bistable TC neurones without dynamic clamp (Fig. 3A) (Williams et al. 1997a; Tuner et al. 1997). Note, in particular, how the similarities in membrane charging patterns and LTCP waveforms were closest between neurones with decreased ILeak (Fig. 3C) and control neurones (Fig. 3A), than between this latter group (Fig. 3A) and neurones with enhanced IT (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Input amplification in the voltage domain.

A1, bistability-mediated input amplification in a cat TC neurone in control conditions. The two smaller current steps are insufficient to drive the membrane potential beyond UP (see Fig. 1), wheras the two larger ones enable the neurone to reach this threshold causing the membrane potential to move toward LSP before being repolarized by Ih. A2, the voltage-current (V-I) relationship for the neurone in A1 reveals a large RN. In this and all other V-I relationships in this figure, the voltage responses were measured at their peak deflection (arrow under the voltage records in A1, B1 and C1) during the current steps. B1, voltage amplification in a different cat TC neurone following the addition of artificial IT (gT(artificial)= 55 nS). The inset shows the response of the neurone without dynamic clamp. B2, V-I relationships for the neurone in B1 illustrates the increase in RN following the addition of artificial IT (○ control; • enhanced IT). B3, schematic representation of the transformation to a bistable system that underlies the response shown in B3. C1, voltage amplification in a rat TC neurone following a reduction in ILeak using artificial inward ILeak (gLeak(artificial)=−7 nS). The inset shows the response of the neurone without dynamic clamp. C2, V-I relationships for the neurone in C1 (○ control; • reduced ILeak). C3, schematic representation of the biophysical changes underlying the response shown in C2.

Time domain

In neurones displaying voltage amplification properties following either the addition of artificial IT {fontsize (gT(artificial)= 106.67 ± 8.16 nS; gT(artificial)/gLeak= 10.00 ± 1.15, n = 5), or reduction in ILeak (gLeak(artificial)=−5.58 ± 1.08 nS; gLeak(artificial)/gLeak=−0.59 ± 0.06, n = 6), it was also observed that the response to relatively short (50–500 ms), negative current steps could often outlast the duration of the input current step by up to 2 or 3 times (Fig. 4B and C). Again, this modified behaviour was characteristic of bistable TC neurones recorded in control conditions (Fig. 4A) (Williams et al. 1997a), with the closest similarities being observed between neurones recorded without dynamic clamp and those with artificial inward ILeak (Fig. 4A and C). It is worth noting that amplification in the voltage and time domain (or membrane potential bistability; see below) could be obtained in the same five neurones by adding artificial IT or artificial inward ILeak in two subsequent dynamic clamp tests (see Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Input amplification in the time domain.

A, example of bistability-mediated input signal amplification in both voltage and time domain recorded in a cat TC neurone in control conditions. This behaviour is due to the fact that subsequent to voltage responses reaching LSP (see Fig. 1), the net current becomes dominated by Ih, and therefore if the time taken for Ih to depolarize the membrane potential beyond UP is longer than the time remaining of the current step, the response will outlast the input. B, the voltage response of another cat TC neurone following an artificial enhancement of IT (gT(artificial)= 120 nS) exhibits amplification properties similar to those shown in A. C, the input amplification in the time domain obtained in a rat TC neurone by addition of artificial inward ILeak (gLeak(artificial)=−7 nS) is remarkably similar to that shown in A. In B and C, identical current steps were used in control and during dynamic clamp, respectively.

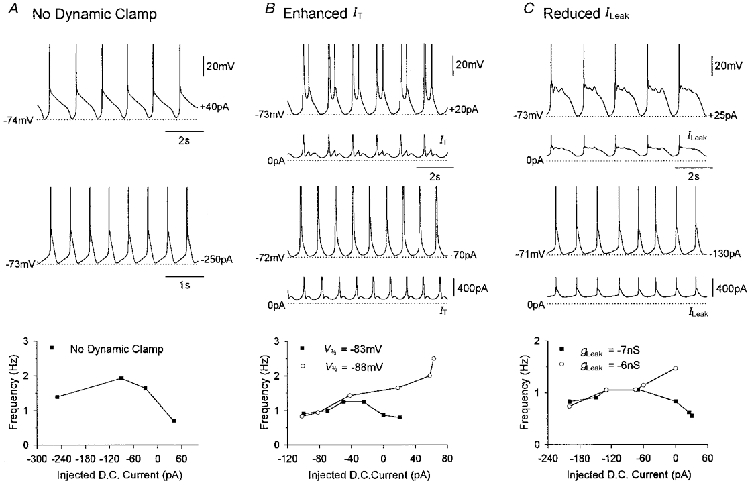

Figure 5. Slow oscillatory activity.

A, bistability-mediated oscillatory activity recorded in a cat TC neurone under control conditions. Note the shoulder following the burst of action potentials in the upper trace and the uncharacteristic form of the frequency-current relationship. At lower values of injected DC current, the existence of the oscillation is dominated by the kinetic and steady-state properties of IT and Ih. At higher values of injected DC current however, the slow activity is largely controlled by equilibrium points formed between IT∞ and ILeak. B, slow oscillatory behaviour induced following an artificial enhancement of IT (gT(artificial)= 100 nS) in another cat TC neurone. This atypical form of the frequency-current relationship can be transformed to the conventional pattern for δ oscillations (10) by reducing IT∞ via a small negative shift (−5 mV) in the half-inactivation voltage (V½) of artificial IT. C, similar activity unveiled in the same TC neurone shown in B following addition of artificial inward ILeak (gLeak(artificial)=−7 nS). Following injection of a smaller amount of artificial inward ILeak (gLeak(artificial)=−6 nS) the neurone displayed δ oscillations and their characteristic frequency-current relationship. In A, B and C, values of injected DC current are indicated on the right of each voltage trace.

Modulation of intrinsic oscillatory activity

In neurones unable to exhibit any intrinsic oscillatory activity in control conditions, either the addition of artificial IT (gT(artificial)= 90.0 ± 33.33 nS; gT(artificial)/gLeak= 8.25 ± 3.26, n = 4), or reduction in ILeak (gLeak(artificial)=−7.17 ± 0.2 nS; gLeak(artificial)/gLeak=−0.69 ± 0.04, n = 3) resulted in the generation of slow (0.1–1 Hz) oscillatory activity. These oscillations differed considerably from conventional δ oscillations (Leresche et al. 1991; Steriade et al. 1991; Pirchio et al. 1997) in that typical increases in frequency in response to increasing DC current were replaced for higher values of DC current by an uncharacteristic decline (Fig. 5B and C). The slow oscillatory activity obtained following either an artificial enhancement of IT, or a reduction in ILeak was once again equivalent to that observed in control conditions in a small group of bistable TC neurones (Fig. 5A) (Williams et al. 1997a; Turner et al. 1997). Notably, in neurones recorded following a reduction in ILeak, or in control conditions, the slow oscillations generated in response to higher values of injected current were characterized by a pronounced plateau or ‘shoulder’ and a subsequent large hyperpolarization (Fig. 5A and C). However, in neurones possessing an artificially enhanced IT, the behaviour was, unsurprisingly, less damped and the plateau replaced by further LTCPs (Fig. 5B).

In both cases, the slow oscillation is the result of what would normally be small, short duration, hyperpolarizing phases in the oscillation being amplified in both the time and voltage domain, leading to an activity largely controlled by the equilibrium points formed between IT∞ and ILeak (see Figs 1 and 5). To further illustrate this point, in two out of the four neurones that were exhibiting slow oscillations following an enhancement of IT, we investigated the effect of a subsequent reduction in IT∞ (and thus a removal of the underlying bistability) by shifting the inactivation curve of artificial IT by −5 mV. In both neurones, this action brought about conventional δ oscillations which displayed a characteristic current-frequency relationship (Fig. 5B) (cf. Fig. 7 in Williams et al. 1997a; Pirchio et al. 1997). Conventional δ oscillations could also be obtained by reducing the amount of artificial inward ILeak (gLeak(artificial)=−5.67 ± 0.41 nS; gLeak(artificial)/gLeak=−0.55 ± 0.04, n = 3) (Fig. 5C).

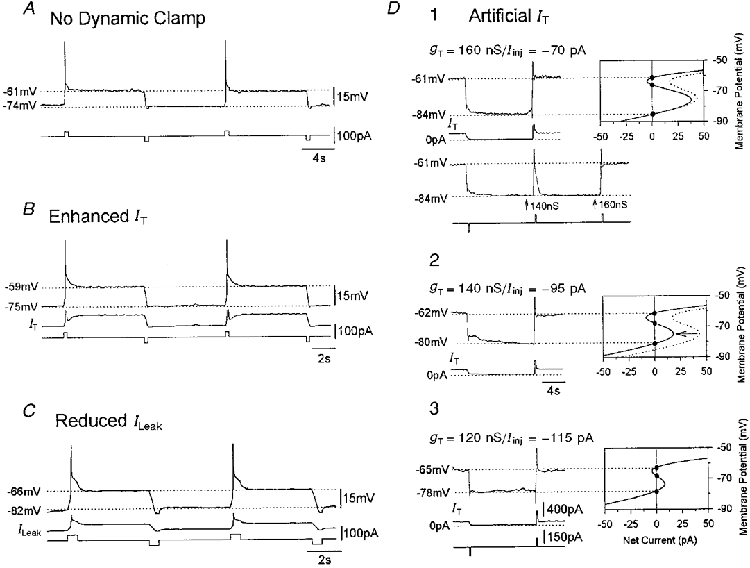

Membrane potential bistability

Following pharmacological blockade of Ih with ZD7288 (300 μm) (Williams et al. 1997b) and either the addition of artificial IT (gT(artificial)= 80.0 ± 24.94 nS; gT(artificial)/gLeak= 7.55 ± 2.54, n = 4) or artificial inward ILeak(gT(artificial)=−4.75 ± 1.52 nS; gLeak(artificial)/gLeak=−0.54 ± 0.07, n = 4), membrane potential bistability became apparent in previously non-bistable neurones whereby two stable voltage levels separated by 14–25 mV co-existed for the same value of injected DC current, and could be ‘switched’ between by appropriate membrane potential perturbations (Fig. 6B and C). This phenomenon was identical to that observed in bistable TC neurones recorded in the presence of ZD7288 (300 μm) without dynamic clamp (Fig. 6A) (Williams et al. 1997a), and re-enforces the point that whilst in the absence of Ih intrinsic bistability is clearly apparent as two separate, steady-state membrane potentials, in the presence of Ih this behaviour is transformed into input signal amplification and slow oscillations.

Figure 6. Membrane potential bistability.

A, membrane potential bistability observed in a cat TC neurone in the presence of ZD7288 (300 μm). The two stable membrane potentials, corresponding to USP and LSP, can be ‘switched’ between if the membrane potential is perturbed beyond UP (see Fig. 1). B and C, membrane potential bistability induced in two different cat TC neurones in the presence of ZD7288 (300 μm) following the addition of artificial IT (gT(artificial)= 100 nS), and artificial inward ILeak (gLeak(artificial)=−7 nS), respectively. D, in another cat TC neurone (D1), traces recorded in the presence of Ni2+ (0.5 mM) and ZD7288 (300 μm) show the two resting membrane potentials to match accurately the points of current balance in the voltage vs. net current plot, constructed using this neurone's gLeak and the indicated artificial IT and injected DC current (Iinj) used in this experiment (continuous line in plot). Note how the decrease in artificial IT from 160 to 140 nS without an accompanying change in Iinj failed to elicit bistability (left arrow in bottom voltage record) since only one equilibrium point was present for this combination of gLeak, artificial IT and Iinj (dotted line in plots in D1 and 2). Membrane potential bistability could be re-instated for an artificial IT of 140 nS when Iinj was changed from −70 to −95 pA (continuous line in D2), or for an even smaller IT and a larger ILeak (D3). Current calibrations in D3 also apply to D1 and 2 and time calibration in D2 applies to D1 and 3.

Since the two stable voltage levels exhibited during membrane potential bistability correspond directly to the upper and lower stable equilibrium points (Fig. 1C), it should be possible to change and predict these values by varying the amounts of either artificial IT (or ILeak) and/or the injected DC current. Indeed, when artificial IT was used to replace entirely the endogenous IT that had been blocked by Ni2+ (0.5–1 mM), it was found that the voltage difference between the two resting membrane potentials exactly matched the one predicted by the amount of artificial IT and DC current (Fig. 6D). The accuracy of these predictions further endorses the suggestion that the behaviours observed in this study following either an enhancement of IT or reduction of ILeak are indeed the result of an intrinsic bistability as described previously (Tóth et al. 1996; Williams et al. 1997a).

Validation of results obtained with artificial IT

To exclude the possibility that attainment of bistability-mediated behaviours through the enhancement of IT was not merely due to the interaction of artificial IT and endogenous ILeak, we compared the values of gLeak with that of (d|IT∞|/dV)max for artificial IT. It was found that (d|IT∞(artificial)|/dV)max (3.81 ± 1.14 nS) was significantly smaller than gLeak (6.44 ± 1.31 nS) (P < 0.05; n = 8), and thus the properties induced by the dynamic clamp were indeed a product of the interaction of ILeak and an effective IT, formed by the superposition of endogenous and artificial IT. It is also important to note: (i) the similarity in the amount of gT(artificial) (or gLeak(artificial)) relative to gLeak (i.e. gT(artificial)/gLeak or gLeak(artificial)/gLeak) required to induce input amplification, slow oscillatory activity and membrane potential bistability, and their small variability (i.e. standard errors) amongst neurones; and (ii) that all these phenomena could be reproduced entirely by the addition of artificial IT following an almost complete removal of endogenous IT by Ni2+ (0.5–1 mM) (gT(artificial)= 147.5 ± 28.82 nS; gT(artificial)/gLeak= 17.65 ± 1.19, n = 4) (cf. Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that any TC neurone in two species can be transformed to a bistable neurone exhibiting input signal amplification, slow oscillations and membrane potential bistability following either an enhancement of endogenous IT or a reduction in endogenous ILeak. These results, therefore, demonstrate the existence of a non-neglible, physiologically relevant IT∞ in all rat and cat TC neurones which may enable them to be bistable under certain physiological and pathological conditions.

Dynamic clamp

The use of the dynamic clamp allowed us to finely control the properties of both IT and ILeak in a manner more flexible than pharmacological manipulations, and more realistic than computer simulations. It is unlikely that the limitations of this technique (e.g. single point current source, lack of emulation of [Ca2+]i dynamics, etc.) will have strongly affected these results since (i) when endogenous IT channels were blocked, the introduction of artificial IT yielded an accurate reproduction of LTCPs, (ii) in experiments involving the enhancement of endogenous IT, this current continued to function normally alongside the artificial current, (iii) there was a good agreement between artificially induced phenomena and those recorded previously without dynamic clamp in a small number of TC neurones (Williams et al. 1997a; Turner et al. 1997), and (iv) the magnitude of the artificial IT required to induce all bistability-related phenomena was comparable amongst different experiments/neurones.

Existence of IT∞

All the results obtained in this study are consistent with our biophysical description of intrinsic bistability. In particular, the agreement between the values of the stable membrane potentials following the complete replacement of endogenous IT with artificial IT and those predicted theoretically confirms that IT∞ and ILeak combine in the manner set out in our biophysical hypothesis to produce certain non-linear phenomena in TC neurones. Previous experimental evidence has shown that intrinsic bistability does not depend on Na+, K+ and high threshold Ca2+ currents (Williams et al. 1997a). Therefore, since (i) in this study all neurones that were tested only with a reduction of ILeak displayed bistability-mediated phenomena, (ii) in experiments involving an enhancement of IT, artificial IT∞ alone was too small to account for bistable behaviour, and (iii) apart from the unique interaction between IT∞ and ILeak, we are unaware of any other possible ionic mechanism for generating subthreshold bistable behaviour with similar properties to those exhibited here, we can conclude that, contrary to findings in previous studies (see review by Huguenard, 1996), a non-negligible, physiologically relevant IT∞ exists in all TC neurones. This also firmly suggests that the reason why not all TC neurones are intrinsically bistable under control conditions is due to differing ratios of gT to gLeak rather than to fundamentally different biophysical properties of IT within the TC neuronal population (Tarasenko et al. 1997; see also Avery & Johnston, 1996; Bean & McDonough, 1998; Meir & Dolphin, 1998).

Source of intrinsic bistability in control conditions

Although it is impossible from the present experiments to determine the precise magnitude of gT/gLeak required to bring about bistability-mediated behaviours, it is worth stressing that the absolute value of gT(artificial)/gLeak necessary for the expression of these phenomena in the presence of endogenous IT was almost half of that required in the absence of endogenous IT, and comparable to that needed to either reproduce or eliminate LTCPs. Together with the finding that a value of around −0.5 for gLeak(artificial)/gLeak is necessary to obtain intrinsic bistability, this result suggests that TC neurones exhibiting bistability-related phenomena in control conditions (i.e. in the absence of dynamic clamp) possess either a gLeak 50 % smaller, or a gT 100 % larger than normal. In other words, the value of gT/gLeak required to bring about intrinsic bistability is probably about twice that typically observed in vitro.

The putative 50 % decrease in gLeak observed in this study is in close agreement with investigations on somal shunt (Rall et al. 1992) and distributed injury conductances (Spruston & Johnston, 1992; Staley et al. 1992). Furthermore, bistability- related phenomena can be more easily observed in TC neurones with a relatively larger gLeak or in the presence of Ba2+ (Williams et al. 1997a; Turner et al. 1997), and in this study there was a clear and consistently greater degree of similarity between behaviours observed in neurones with an artificially reduced ILeak and those without dynamic clamp, compared with that between this latter group of neurones and those with an enhanced IT. Therefore, although we cannot exclude the possibility that a small group of TC neurones possessing a larger than usual gT has remained undetected in the large number of studies on IT (Huguenard, 1996), the available experimental and theoretical evidence favours a reduced gLeak as responsible for only a minority of these neurones being able to show bistability-related phenomena under control conditions. In particular, in vitro, this reduced gLeak may be due to either normal variations, minimized somal shunt or, appealingly, the presence of differing amounts of neurotransmitters that are known to affect ILeak in TC neurones (McCormick & Pape 1990b; McCormick & VonKrosigk, 1992; Steriade et al. 1994).

Bistability in normal and pathological thalamic processes

Although it may be argued that the bistability-mediated phenomena described here are unlikely to occur in vivo due to the intense and constant synaptic actvity causing a substantial increase in apparent input conductance (Bernander et al. 1991; Rall et al. 1992), it should be noted that a number of pathways exist which may potentially lead to the unmasking of bistability in TC neurones.

Firstly, during periods of wakefulness, acetylcholine-containing neurones of the mesopontine nuclei and noradrenaline-containing neurones of the locus coeruleus, both of which project onto TC neurones, exhibit a pronounced increase in firing rate (Aston-Jones & Bloomfield, 1981; Steriade et al. 1990). Moreover, noradrenaline and acetylcholine have both been shown to cause reductions of ILeak in TC neurones (McCormick & Prince, 1987; McCormick & Pape, 1990b). Thus, it appears feasible that in addition to causing membrane potential depolarization and a shift from burst to tonic firing (McCormick & Prince, 1987; McCormick & Pape, 1990b), activity in certain brainstem nuclei may cause the dynamics of some TC neurones to undergo a state-dependent transformation from a monostable to a bistable nature. Such a change in the properties of TC neurones could have important consequences for the processing of sensory information in the thalamus. For example, both excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials evoked in bistable TC neurones via stimulation of sensory afferents can cause large, long-lasting amplified hyperpolarizations (Williams et al. 1997a). During these hyperpolarizations, TC neurones will be less likely to fire single action potentials in response to further sensory input and so their ability to be involved in the relay of peripheral information to the cerebral cortex may be transiently reduced via a self-limiting mechanism. However, the instigation of a large hyperpolarization by afferent stimuli may be indicative of a scenario whereby TC neurones can be primed to generate LTCP-mediated burst firing as a more specific signal in response to subsequent sensory input (Guido & Weyland, 1995). Secondly, activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors, either via stimulation of corticothalamic fibres (McCormick & VonKrosigk, 1992) or not (Turner & Salt, 1998), has also been shown to cause a reduction of ILeak. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to suggest that activity in layer VI cortical neurones, or other fibres presynaptic to metabotropic glutamate receptors, may also lead to the formation of bistable behaviour in TC neurones causing their information transfer properties to be radically altered via a novel feedback mechanism. Additionally, the region of negative slope conductance known to accompany the slow response of central neurones to NMDA (Nowak et al. 1984; Crunelli & Mayer, 1984) may act to facilitate bistability in both of the above scenarios.

Alternatively, intrinsic bistability might be envisaged to accompany the transition from a high to a low conductance state that is associated with a reduction in synaptic input as would be expected during the onset of periods of decreased arousal. In this condition, synaptic activity, via periodic activation of NMDA (Leresche et al. 1991), non-NMDA (Soltesz & Crunelli, 1992a), GABAA (von Krosigk et al. 1993; Bal et al. 1995) and GABAB (Crunelli & Leresche, 1991; Soltesz & Crunelli, 1992b; von Krosigk et al. 1993; Bal et al. 1995) receptors, takes on a largely discrete, synchronized form. As such, synaptic signals appear as well defined, isolated stimuli (Bernander et al. 1991) and, therefore, rather than preventing bistability would become subject to bistability-mediated amplification (Williams et al. 1997a). This in turn would increase the propensity of TC neurones to produce both intrinsic (Leresche et al. 1991; Curró-Dossi et al. 1992; Williams et al. 1997a), and network (Steriade et al. 1993; von Krosigk et al. 1993; Bal et al. 1995) oscillations.

Apart from a reduction of ILeak, bistable behaviour could emerge as a result of a large gT such as that suggested (Jeanmonod et al. 1996), or shown (Chung et al. 1993; Tsakiridou et al. 1995) to correspond to certain pathological conditions. Thus, the appearance of bistable TC neurones may play an incisive role in initiating and controlling both physiological (Steriade et al. 1993; von Krosigk et al. 1993; Bal et al. 1995) and pathological (von Krosigk et al. 1993; Steriade et al. 1994; Bal et al. 1995; Pinault et al. 1998) rhythms in the thalamus. In conclusion, IT∞-dependent bistability is an integral part of the electroresponsiveness of TC neurones that may also underlie crucial components in a variety of neuronal mechanisms in other excitable cells that possess an IT with similar biophysical properties (Huguenard, 1996; Perez-Reyes et al. 1998).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr H. R. Parri for critical comments on the manuscript and Mr T. Gould for technical assistance. This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust (grant 37089-98). S. W.H. and S. R. W. were Wellcome Prize Students.

References

- Aston-Jones G, Bloomfield FE. Norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats exhibit pronounced responses to non-noxious environmental stimuli. Journal of Neuroscience. 1981;1:887–900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00887.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery RB, Johnston D. Multiple channel types contribute to the low-voltage-activated calcium current in hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:5567–5582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05567.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal T, von Krosigk M, McCormick DA. Synaptic and membrane mechanisms underlying synchronized oscillations in the ferret lateral geniculate nucleus. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;483:641–663. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP, McDonough SI. Two for T. Neuron. 1998;20:825–828. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernander O, Douglas RJ, Martin KAC, Koch C. Synaptic background activity influences spatiotemporal integration in single pyramidal cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:11569–11573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JM, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Transient enhancement of low-threshold calcium current in thalamic relay neurons after corticectomy. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70:20–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope DW, Hughes SW, Tóth TI, Williams SR, Crunelli V. All thalamocortical neurones possess an IT‘window’ current that allows the expression of bistability-mediated behaviours. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1998;24:644.10. [Google Scholar]

- Crunelli V, Leresche N. A role for GABAB receptors in excitation and inhibition of thalamocortical cells. Trends in Neurosciences. 1991;14:16–21. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90178-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunelli V, Mayer ML. Mg2+ dependence of membrane resistance increases evoked by NMDA in hippocampal neurones. Brain Research. 1984;311:392–396. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curró-Dossi R, Nunez A, Steriade M. Electrophysiology of a slow (0.5–4 Hz) intrinsic oscillation of cat thalamocortical neurones in vivo. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;447:215–234. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes M, Paradis M, Roy JP, Steriade M. Electrophysiology of neurons of lateral thalamic nuclei in cat: resting properties and burst discharges. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1984;51:1196–1219. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.6.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DD, MacVicar BA. Low-threshold transient calcium current in rat hippocampal lacunosum-moleculare interneurons - kinetics and modulation by neurotransmitters. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:2812–2820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-09-02812.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A, Gutnick MJ. Low threshold calcium electrogenesis in neocortical neurones. Neuroscience Letters. 1987;81:117–122. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90350-8. 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guido W, Weyland T. Burst responses in thalamic relay cells in the awake behaving cat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;74:1782–1786. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.4.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SW, Cope DW, Tóth TI, Williams SR, Crunelli V. Dynamic clamp study of input signal amplification and bistability in thalamocortical neurones in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;506.P:151P. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.689ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguenard JR. Low threshold calcium currents in central nervous system neurons. Annual Review of Physiology. 1996;58:329–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.001553. 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.001553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnsen H, Llinás R. Electrophysiological properties of guinea-pig thalamic neurones: an in vitro study. The Journal of Physiology. 1984;349:205–226. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanmonod D, Magini M, Morel A. Low-threshold calcium spike bursts in the human thalamus. Common physiopathology for sensory, motor and limbic positive symptoms. Brain. 1996;119:363–375. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.2.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leresche N, Lightowler S, Soltesz I, Jassik-Gerschenfeld D, Crunelli V. Low-frequency oscillatory activities intrinsic to rat and cat thalamocortical cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;441:155–174. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Yarom Y. Properties and distribution of ionic conductances generating electroresponsiveness of mammalian inferior olivary neurones in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1981;315:549–567. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA. Neurotransmitter actions in the thalamus and cerebral cortex and their role in neuromodulation of thalamocortical activity. Progress in Neurobiology. 1992;39:337–388. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90012-4. 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Pape H-C. Properties of a hyperpolarization-activated cation current and its role in rhythmic oscillation in thalamic relay neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1990a;431:291–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Pape H-C. Noradrenergic and serotonergic modulation of a hyperpolarization-activated cation current in thalamic relay neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1990b;431:319–342. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Prince DA. Actions of acetylcholine in the guinea-pig and cat medial and lateral geniculate nuclei, in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;392:147–165. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, VonKrosigk M. Corticothalamic activation modulates thalamic firing through glutamate ‘metabotropic’ receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:2774–2778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meir A, Dolphin AC. Known calcium channel α1 subunits can form low threshold small conductance channels with similarities to native T-type channels. Neuron. 1998;20:341–351. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80461-4. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak L, Bregestovski P, Ascher P, Herbet A, Prochiantz A. Magnesium gates glutamate-activated channels in mouse central neurones. Nature. 1984;307:462–465. doi: 10.1038/307462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E, Cribbs LL, Daud A, Lacerda AE, Barclay J, Williamson MP, Fox M, Rees M, Lee J-H. Molecular characterization of a neuronal low-voltage-activated T-type calcium channel. Nature. 1998;391:896–900. doi: 10.1038/36110. 10.1038/36110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinault D, Leresche N, Charpier S, Deniau JM, Marescaux C, Vergnes M, Crunelli V. Intracellular recordings in thalamic neurones during spontaneous spike and wave discharges in rats with absence epilepsy. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;509:449–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.449bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirchio M, Turner JP, Williams SR, Asprodini E, Crunelli V. Postnatal development of membrane properties and δ oscillations in thalamocortical neurons of the cat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:5428–5444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05428.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall W, Burke RE, Holmes WR, Jack JJB, Redman S, Segev I. Matching dendritic neurone models to experimental data. Physiological Reviews. 1992;72:159–186. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.suppl_4.S159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp AA, O'Neil MB, Abbott LF, Marder E. Dynamic clamp: computer-generated conductances in real neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;69:992–995. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.3.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltesz I, Crunelli V. A role for low-frequency, rhythmic synaptic potentials in the synchronization of cat thalamocortical cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1992a;457:257–276. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltesz I, Crunelli V. GABAA and pre-and post-synaptic GABAB receptor-mediated responses in the lateral geniculate nucleus. Progress in Brain Research. 1992b;90:151–169. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruston N, Johnston D. Perforated patch-clamp analysis of the passive membrane-properties of 3 classes of hippocampal-neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;67:508–529. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.3.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley KJ, Otis TS, Mody I. Membrane-properties of dentate gyrus granule cells - comparison of sharp microelectrode and whole-cell recordings. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;67:1346–1358. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.5.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Datta S, Pare D, Oakson G, Curró-Dossi R. Neuronal activities in brainstem cholinergic nuclei related to tonic activation processes in thalamocortical systems. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:2541–2559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-08-02541.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Contreras C, Amzica F. Synchronized sleep oscillations and their paroxysmal developments. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90105-8. 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90104-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Curró Dossi R, Nuñez A. Network modulation of a slow intrinsic oscillation of cat thalamocortical neurons implicated in sleep delta-waves - cortically induced synchronization and brain-stem cholinergic suppression. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:3200–3217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03200.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, McCormick DA, Sejnowski TJ. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science. 1993;262:679–685. doi: 10.1126/science.8235588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasenko AN, Kostyuk PG, Eremin AV, Isaev DS. Two types of low-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in neurones of rat laterodorsal thalamic nucleus. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;499:77–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth TI, Williams SR, Crunelli V. In: Cybernetics and Systems ‘96. Trapl R, editor. Vienna: Austrian Society for Cybernetic Studies; 1996. pp. 530–535. [Google Scholar]

- Tsakiridou E, Bertollini L, de Curtis M, Avanzini G, Pape H-C. Selective increase in T-type calcium conductance of reticular thalamic neurons in a rat model of absence epilepsy. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:3110–3117. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-03110.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JP, Anderson CM, Williams SR, Crunelli V. Morphology and membrane properties of neurones in the cat ventrobasal thalamus in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;505:707–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.707ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JP, Salt TE. Characterization of sensory and corticothalamic excitatory inputs to rat thalamocortical neurones in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:829–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.829bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Krosigk M, Bal T, McCormick DA. Cellular mechanisms of a synchronized oscillation in the thalamus. Science. 1993;261:361–364. doi: 10.1126/science.8392750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SR, Tóth TI, Turner JP, Hughes SW, Crunelli V. The ‘window’ component of the low threshold Ca2+ current produces input signal amplification and bistability in cat and rat thalamocortical neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1997a;505:689–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.689ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SR, Turner JP, Anderson CM, Crunelli V. Electrophysiological and morphological properties of interneurones in the rat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;490:129–147. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SR, Turner JP, Hughes SW, Crunelli V. On the nature of anomalous rectification in thalamocortical neurones of the cat ventrobasal thalamus in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1997b;505:727–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.727ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]