Abstract

The whole-cell patch clamp technique was used to study the role of muscarinic receptors in regulating the frequency of giant depolarizing potentials (GDPs) in CA3 hippocampal neurones in slices from postnatal (P) P1-P8 rats.

Atropine (1 μM) reduced the frequency of GDPs by 64·2 ± 2·9%. The acetylcholinesterase inhibitor edrophonium (20 μM) increased the frequency of GDPs in a developmentally regulated way. This effect was antagonized by the M1 muscarinic receptor antagonist pirenzepine.

In the presence of edrophonium, tetanic stimulation of cholinergic fibres induced either an enhancement of GDP frequency (179 ± 79%) or a membrane depolarization (27 ± 16 mV) associated with an increase in synaptic noise. These effects were prevented by atropine.

Application of carbachol (3 μM) produced an increase in GDP frequency that at P5-P6 was associated with a membrane depolarization and an increase in synaptic noise. These effects were prevented by atropine, pirenzepine (3 μM) and bicuculline (10 μM).

In the presence of pirenzepine, carbachol reduced GDP frequency by 50 ± 4%. Conversely, in the presence of methoctramine (3 μM), carbachol enhanced GDP frequency by 117 ± 4%.

It is concluded that endogenous acetylcholine, through the activation of M1 receptors, enhances the release of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), in a developmentally regulated way. On the other hand, carbachol exerts both an up- and downregulation of GABA release through the activation of M1 and M2 receptors, respectively.

Giant depolarizing potentials (GDPs) are network-driven synaptic events, which occur synchronously over the entire hippocampal slice during the first postnatal week and are generated mainly by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) acting on GABAA receptors (Ben-Ari et al. 1989). As in many other brain structures (Wu et al. 1992; Serafini et al. 1995; Chen et al. 1996; Kaneda et al. 1996; Owens et al. 1996), at this early developmental stage GABA is depolarizing and excitatory (for a review see Cherubini et al. 1991). The depolarizing action of GABA ensures elevation of [Ca2+]i following calcium entry through activation of voltage-dependent calcium channels (Leinekugel et al. 1995) and/or N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Leinekugel et al. 1997; Ben-Ari et al. 1997). Thus, calcium fluctuations co-active with GDPs can be detected by optical recordings with Ca2+-sensitive dyes in groups of neighbouring cells (Garaschuk et al. 1998). These highly correlated calcium signals are thought to be essential for consolidation of synaptic connections and development of the adult neuronal circuit (Shatz, 1990). Previous studies from this and other laboratories have shown that a glutamatergic drive is essential for maintaining network synchronization (Ben-Ari et al. 1989; Cherubini et al. 1991; Gaiarsa et al. 1991; Strata et al. 1995; Khazipov et al. 1997), which may occur mainly through the (RS)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA) type of receptor (Bolea et al. 1999).

GDPs could be also modulated by acetylcholine (ACh) acting on nicotinic and muscarinic receptor types. The hippocampus, in fact, receives a large cholinergic innervation from the septo-hippocampal pathway which originates in the basal forebrain from the medial septal nucleus and from the diagonal band of Broca (Kása, 1986). This projection, mainly cholinergic, is of fundamental importance in maintaining higher cognitive functions (Dutar et al. 1995). Combined biochemical and histochemical experiments have demonstrated that cholinergic fibres start to reach their target in the hippocampus at postnatal day (P) P1-P3 and attain the adult pattern towards the end of the second postnatal week (Nyakas et al. 1994). In contrast to the relatively late maturation of cholinergic fibres, in the hippocampus, muscarinic receptors are present and already functional at P2 (Reece & Schwartzkroin, 1991), although a sharp increase occurs between P4 and P10 (Ben-Barak & Dudai, 1979).

The aim of this work was to study how GDPs are modulated by endogenous ACh acting on muscarinic receptors. We found that ACh, through the activation of the M1 muscarinic receptor subtype, enhances the release of GABA, assayed as GDPs, in a developmentally regulated manner. Carbachol, on the other hand, exerts both a potentiating and a depressing effect on GDP frequency through the activation of M1 and M2 receptors, respectively.

METHODS

Slice preparation

Experiments were performed on hippocampal slices obtained from postnatal P1-P8 Wistar rats (P0 is the day of birth) according to the methods already described (Strata et al. 1995). Briefly, animals were decapitated after being anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of urethane (2 g kg−1). This procedure is in accordance with the regulations of the Italian Animal Welfare Act and was approved by the local authority veterinary service. The brain was quickly removed from the skull and the hippocampi were dissected free. Transverse 600 μm thick slices were cut with a tissue chopper and maintained at room temperature (22-24°C) in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (mM): NaCl, 126; KCl, 3.5; NaH2PO4, 1.2; MgCl2, 1.3; CaCl2, 2; NaHCO3, 25; glucose, 11 (pH 7.3), saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. After incubation in ACSF for at least 1 h, an individual slice was transferred to a submerged recording chamber, continuously superfused at 33-34°C with oxygenated ACSF at a rate of 3 ml min−1.

Patch clamp whole-cell recordings

Spontaneous GDPs were recorded in the whole-cell configuration of the patch clamp technique (current clamp mode) with a standard amplifier (Axoclamp-2B; Axon Instruments). Patch electrodes had a resistance of 3-6 MΩ when filled with an intracellular solution containing (mM): KCl, 140; MgCl2, 1; NaCl, 1; EGTA, 1; Hepes, 5; K2ATP, 2; pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH. In order to differentiate GDPs from interictal discharges that sometimes develop after P4 in the presence of bicuculline, an intracellular solution containing 40 mM KCl and 90 mM potassium gluconate (instead of 140 mM KCl) was used. With this solution the reversal of GABA-mediated GDPs should substantially differ from that of interictal bursts which are probably glutamatergic in origin. In some experiments, in order to test the effects of endogenous ACh on GDPs, a 2 s train of pulses (60 μs duration each) was applied at a frequency of 25 Hz through bipolar twisted NiCr-insulated electrodes (50 μm o.d.) placed in the hilus. Membrane input resistance was measured from the amplitude of electrotonic potentials evoked by passing small hyperpolarizing current pulses (300 ms duration) across the cell membrane.

Drugs

Drugs used were: (+)-3-(2-carboxy-piperazin-4-yl)-propyl-1-phosphonic acid (CPP), 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), 5,11-dihydro-11-[(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl) acetyl] -6H-pyrido [2,3-b][1,4] benzodiazepin-6-one (pirenzepine) and bicuculline, all purchased from Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK; atropine, carbachol, {tracking 1}ethyl[m-hydroxyphenyl]dimethylammonium (edrophonium) chloride{tracking} and tetrodotoxin (TTX) from Sigma; N,N’-bis[6-[[(2-methoxyphenyl)methyl]amino]hexyl]-1,8-octane diamine tetrahydrochloride (methoctramine) from RBI; GYKI 53655 was a gift of Dr E. Sher, Eli Lilly & Co., Windlesham, UK. All drugs except GYKI 53655 and CNQX were dissolved in ACSF and applied in the bath by changing the superfusion solution to one which differed only in its content of drug(s). GYKI 53655 and CNQX were dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) at a final concentration of 20 mM (stock solution). Control experiments using a solution containing 0.25% DMSO did not affect GDP frequency, spontaneous events, membrane potential or input resistance. The ratio of flow rate to bath volume ensured complete exchange within 1 min. If not otherwise stated, data are expressed as means ±s.e.m.; n indicates the number of neurones tested.

Data acquisition and analysis

Data of spontaneous GDPs were stored on magnetic tape and transferred to a computer after digitization with a A/D converter (Digidata 1200). Data acquisition was done using pCLAMP (Axon Instruments) and the amplitude and frequency of GDPs were analysed with Axoscope (Axon Instruments).

RESULTS

Endogenous ACh increases the frequency of GDPs through M1 muscarinic receptor subtypes

Stable whole-cell recordings (in current clamp configuration) lasting more than 30 min were obtained from 110 CA3 hippocampal pyramidal cells in slices from P1-P8 rats, which exhibited spontaneous GDPs. These occurred at a frequency of 0.06 ± 0.005 Hz and consisted of large (30-50 mV) depolarizing potentials lasting 400-700 ms, which triggered action potentials, followed by an after-hyperpolarization. As already reported (Ben-Ari et al. 1989), GDPs are network-driven events generated by a large population of neurones firing synchronously since: (i) their frequency was independent of the membrane potential; (ii) they were synchronous in pair CA3 recordings; and (iii) they were reversibly blocked by a high-magnesium, low-calcium solution and were abolished by TTX.

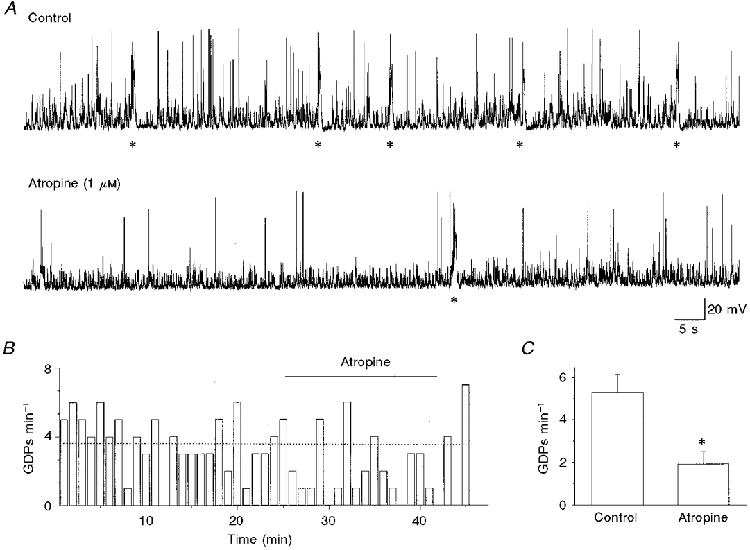

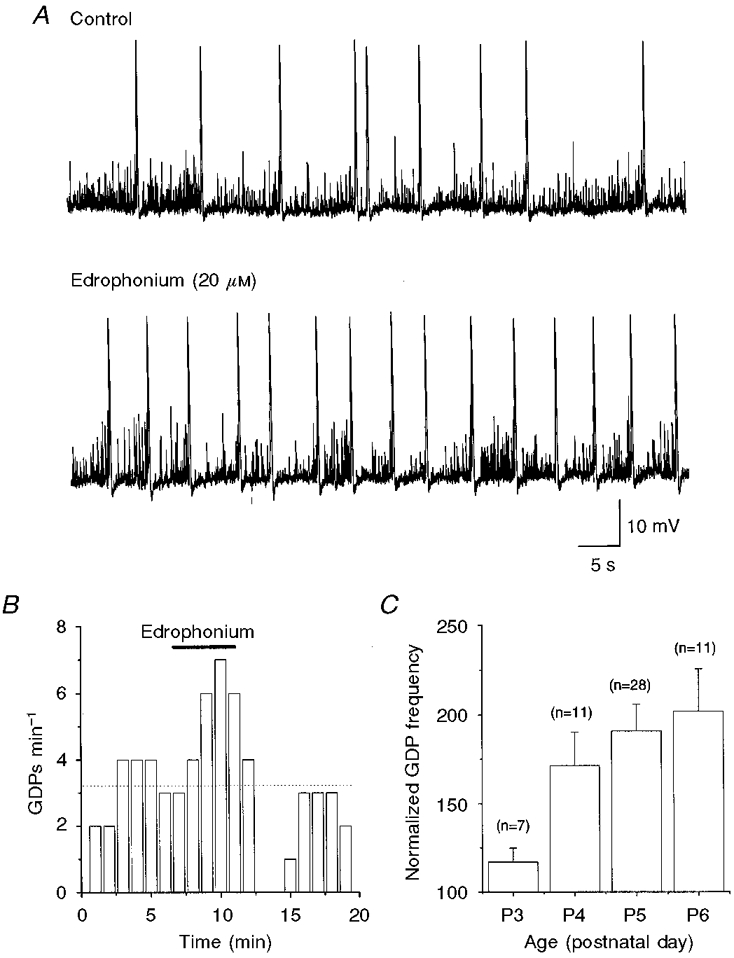

In a first set of experiments, in order to see whether endogenous ACh was able to modulate GDPs, the muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine (1 μM) was applied in six slices obtained from P3-P6 rats. In five of six neurones, atropine (in the absence of any change in membrane potential or input resistance) induced a significant (P < 0.001, Student's paired t test) decrease in frequency of GDPs of 64.2 ± 2.9% (Fig. 1), which in four cases lasted for 4-7 min. In the continued presence of the antagonist, GDP frequency tended to return towards control values. Since ACh is rapidly hydrolysed by acetylcholinesterase (AChE), the following experiments were done in the presence of the AChE inhibitor edrophonium (20 μM). This compound caused an increase in frequency of GDPs in almost all neurones tested (50/57; Fig. 2), in the absence of any change in membrane potential or membrane input resistance. The mean frequency of GDPs was 0.057 ± 0.004 Hz in control and 0.096 ± 0.007 Hz in the presence of edrophonium. These values were significantly different (P < 0.0001, paired t test). No changes in GDP shape were observed. Sometimes, as shown in the graph of Fig. 2B, the potentiating effect of edrophonium was followed by a temporary reduction or block of GDPs after removal of the drug. This effect may be due to receptor desensitization following AChE inhibition and secondary accumulation of ACh in the tissue. To see whether this hypothesis was correct, in four slices edrophonium was maintained in the bath for prolonged (12-18 min) periods of time. In these cases, edrophonium produced a persistent potentiating effect for the entire period of application. The effects of edrophonium were reproducible: two consecutive applications of the drug, with a 15 min interval, induced similar effects. When the second application was made in the presence of atropine (1 μM), the muscarinic antagonist was able to prevent the potentiating action of edrophonium, suggesting that the effects of this drug on GDPs were mediated by ACh acting on muscarinic receptors (n = 3; data not shown).

Figure 1. Atropine reduces GDP frequency.

A, continuous recording from a P4 CA3 pyramidal neurone (at -75 mV) under control conditions (upper trace) and during bath application of atropine (lower trace). GDPs are indicated by asterisks. B, GDP frequency (cell shown in A) before, during and after atropine application (bar) as a function of time. Each column represents the number of GDPs recorded in 1 min. The dotted line represents the mean GDP frequency under control conditions. C, each column represents the mean frequency of GDPs calculated in five cells (over a set period of 5 min) before (Control) and during atropine application. Error bars represent s.e.m.; *P < 0.001, Student's paired t test.

Figure 2. Edrophonium enhances GDP frequency in a developmentally regulated way.

A, representative traces from a P5 CA3 pyramidal cell (at -55 mV), under control conditions (upper trace) and during superfusion of edrophonium (lower trace). B, GDP frequency (cell shown in A) before, during and after edrophonium application (bar) as a function of time. Each column represents the number of GDPs recorded in 1 min. The dotted line represents the mean GDP frequency under control conditions. C, mean GDP frequency in edrophonium, normalized to control values and expressed as a percentage, at different postnatal ages. Error bars represent s.e.m. values for the number of cells tested (n).

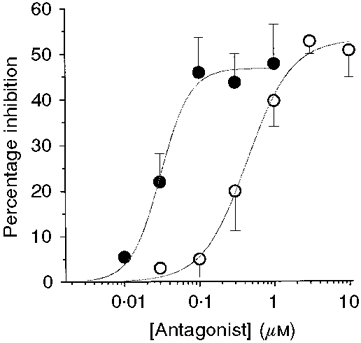

The effect of endogenous ACh on GDP frequency was developmentally regulated as shown by the fact that, in the presence of edrophonium, the percentage increase in frequency of GDPs varied from 17 ± 8% at P3 to 102 ± 23% at P6 (Fig. 2C). This suggests that an increase in cholinergic fibres and/or muscarinic receptors occurs with age. In a second series of experiments, the ability of the M1 and M2 receptor antagonists pirenzepine and methoctramine, respectively, to block the effects of edrophonium was tested (n = 23). Both drugs reduced the frequency of GDPs by up to about 50%. The concentrations of pirenzepine and methoctramine that gave 50% of maximum effect (EC50) were 30 and 430 nM, respectively (Fig. 3). The higher potency of pirenzepine in antagonizing the effects of edrophonium on GDP frequency, in comparison with methoctramine, strongly suggests that the M1 subtype of muscarinic receptor is involved in the edrophonium action.

Figure 3. The potentiating effect of edrophonium on GDP frequency is mediated by the M1 muscarinic receptor subtype.

Percentage inhibition of GDP frequency (in edrophonium) induced by increasing concentrations of pirenzepine (•) and methoctramine (○). Each point represents the mean of 3-6 experiments. Error bars are s.e.m. Data points are fitted with the Hill equation: I(C) =Imax/[1 + (EC50/C)nH], where I is percentage inhibition, C is antagonist concentration, Imax is maximal inhibition, EC50 is the effective concentration producing half-maximum inhibition and nH is the Hill coefficient.

Electrical stimulation of cholinergic fibres mimics the muscarinic action of ACh on GDPs

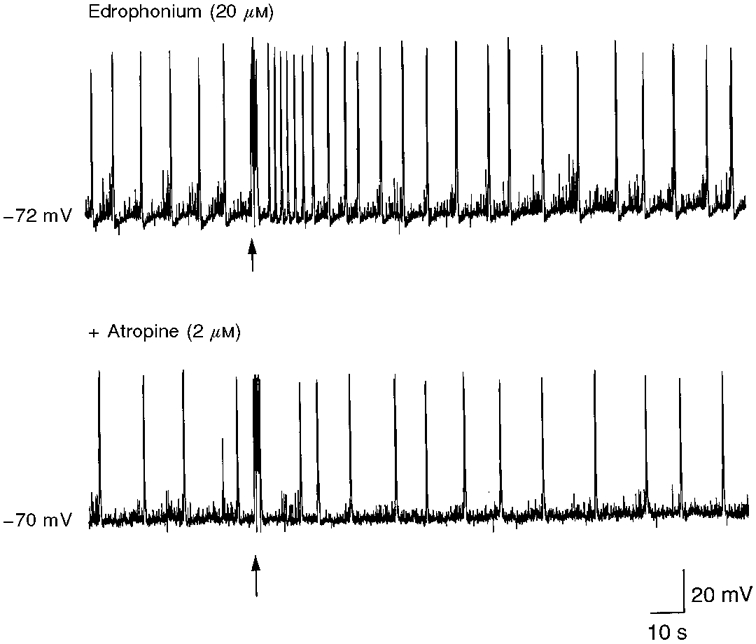

It is known that cholinergic fibres enter the hippocampus mainly through the fimbria and terminate in all the fields of the hippocampal formation (Kása, 1986). In an attempt to reproduce the muscarinic effect of ACh on GDP frequency, hippocampal slices from P4-P6 rats were repetitively stimulated in the hilus with a train of stimuli at 25 Hz. In these experiments, to increase the sensitivity of the system to ACh, edrophonium was routinely applied at a concentration of 20 μM. In four cells, the tetanic stimulation produced a significant (P < 0.05, paired t test) increase in GDP frequency (179 ± 79%) that lasted 10-20 s; in an additional five neurones, the stimulation train induced a membrane depolarization (27 ± 16 mV) associated with an increase in synaptic noise. These effects were prevented by atropine (2 μM; n = 3; Fig. 4). It is interesting to note that, under our experimental conditions (whole-cell patch clamp recordings), we failed to observe any direct postsynaptic effects of ACh on principal cells. Thus, slow cholinergic EPSPs were never detected following a train of stimuli.

Figure 4. Electrical stimulation of the hilus mimics the muscarinic action of ACh on GDPs.

GDPs recorded from a P5 CA3 pyramidal neurone in the presence of edrophonium (upper trace) and edrophonium plus atropine (lower trace). Brief (60 μs, for 2 ms) trains of stimuli at 25 Hz to the hilus (arrows) induced an increase in frequency of GDPs only in the absence of atropine, suggesting that the observed effect was due to the action of ACh (released from cholinergic fibres) on muscarinic receptors.

Carbachol regulates the release of GABA from GABAergic interneurones

Carbachol was applied to 37 CA3 pyramidal neurones (at membrane potentials ranging from -65 to -75 mV) in slices obtained from P1-P8 rats. The minimum dose of carbachol required to produce an effect was 1 μM. However, this concentration of carbachol often failed to induce any clear effect in slices obtained from very young animals. Therefore a concentration of 3 μM was routinely used. At this concentration, the effects of the drug changed markedly during development. At P1-P4, superfusion of carbachol produced a 5.9 ± 0.8-fold increase in frequency of GDPs with small (1.7 ± 0.9 mV) or no changes in membrane potential (Fig. 5). The effect of carbachol was rapid in onset (1 min after carbachol reached the tissue) and complete recovery was obtained several (5-10) minutes after washout. Sometimes, this effect was associated with an increase in frequency of spontaneous ongoing synaptic potentials that at this early postnatal period are mainly GABA mediated (Hosokawa et al. 1994). After P5, carbachol caused only a transient increase in GDP frequency, followed by a membrane depolarization (15.3 ± 2.1 mV) that was associated with an increase in synaptic noise. This often gave rise to high frequency action potentials (Fig. 5). Upon washout of the drug, the membrane potential returned to the resting value, but the increase in synaptic noise persisted for a prolonged period of time (from 1 to 4 min). GDPs started to reappear 2-5 min after washout. The carbachol-induced increase in frequency of GDPs and spontaneous synaptic potentials as well as the membrane depolarization were prevented by atropine (2 μM, n = 3; data not shown). Bath application of bicuculline (10 μM; n = 12) blocked GDPs, drastically reduced the synaptic noise as well as the effects of carbachol on the membrane potential (Fig. 6). It should be stressed that, towards the end of the first postnatal week (between P4 and P6), bicuculline often (n = 5/7) induced the appearance of interictal bursts, which occurred at very low frequency (ranging from 0.003 to 0.012 Hz). Interictal discharges differed from GDPs in the following points: (i) they developed slowly, only 5-8 min after GDPs were completely blocked by bicuculline; (ii) they had a faster rising phase and lasted longer (see Fig. 6); and (iii) in two experiments performed with an intrapipette solution containing 90 mM potassium gluconate and 40 mM KCl (instead of 140 mM KCl; see Methods), they reversed at +7 and +5 mV (see also Ben-Ari et al. 1989) whereas GDPs reversed at -30 mV. In agreement with previous reports (Williams & Kauer, 1997; Psarropoulou & Dallaire, 1998), carbachol (1-3 μM) increased the frequency of interictal bursts (Fig. 6). Interictal bursts, as well as the potentiating effect of carbachol, were blocked by CNQX (10 μM; data not shown), indicating that muscarinic activation was presumably affecting both the pre- and postsynaptic AMPA/kainate type of glutamate receptor.

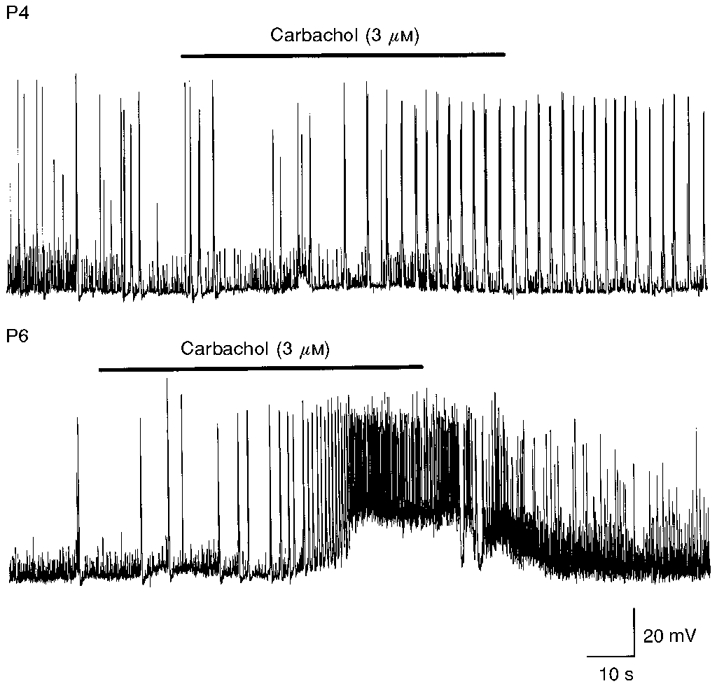

Figure 5. Distinct effects of carbachol at different postnatal ages.

Upper trace, application of carbachol (bar) to a P4 neurone (at -74 mV) induced an increase in frequency of GDPs, in the absence of any change in membrane potential. Lower trace, the same concentration of carbachol (bar) applied at P6 to a CA3 pyramidal cell (at -75 mV) induced a transient increase in GDP frequency followed by a membrane depolarization and an increase in synaptic noise.

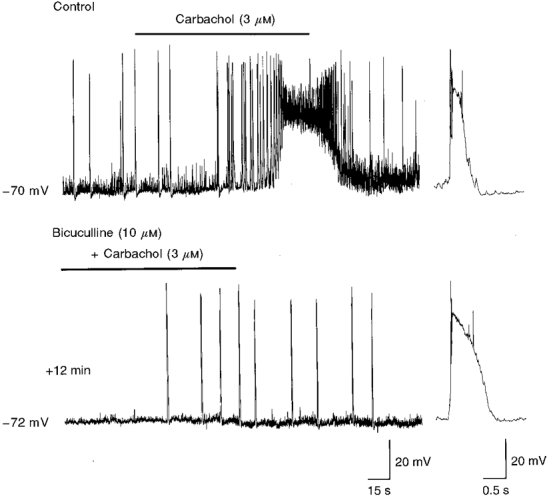

Figure 6. The effects of carbachol on GDP frequency, membrane depolarization and increase in synaptic noise are prevented by bicuculline.

Upper trace, bath application of carbachol (bar) to a P6 CA3 pyramidal cell induced a transient increase in GDP frequency followed by a membrane depolarization and an increase in synaptic noise. Superfusion of bicuculline to the same cell (lower trace) blocked GDPs and reduced spontaneous GABA-mediated synaptic potentials. In bicuculline, carbachol induced the appearance of interictal discharges. The traces to the right show a GDP (upper trace) and an interictal discharge (lower trace), on an expanded time scale.

The effects of carbachol on GABA release are mediated by at least two different muscarinic receptor subtypes

To see whether the potentiating and depressing effects of carbachol on GDP frequency were mediated by distinct muscarinic receptors, additional experiments were performed using the selective muscarinic receptor antagonists pirenzepine and methoctramine, known to act on M1 and M2 receptors, respectively (Auerbach & Segal, 1996). As shown in the representative example of Fig. 7, bath application of pirenzepine (3 μM) prevented the effects of carbachol on membrane depolarization and synaptic noise. Furthermore, in the presence of pirenzepine, carbachol reduced GDP frequency by 50 ± 4% (n = 4). In contrast, in the same cells, the M2 receptor antagonist methoctramine (3 μM) enhanced the effects of carbachol on the frequency of GDPs (by 117 ± 4%; n = 4), which often occurred in clusters (Fig. 7). These values were significantly (P < 0.01) different from those obtained before treatment with the respective drugs. The effect of carbachol was measured as the ratio of GDP frequency during and before drug application. Both the effects of pirenzepine and methoctramine were fully reversible upon washout. Since the effects of carbachol were quite variable at different postnatal ages, and from cell to cell in slices from the same postnatal age, it was impossible to determine the relative EC50 values for these drugs. These experiments indicate that carbachol exerts two different effects on GDPs: it increases their frequency through an M1 receptor subtype while it exerts an inhibitory action via a non-M1, presumably an M2, receptor subtype.

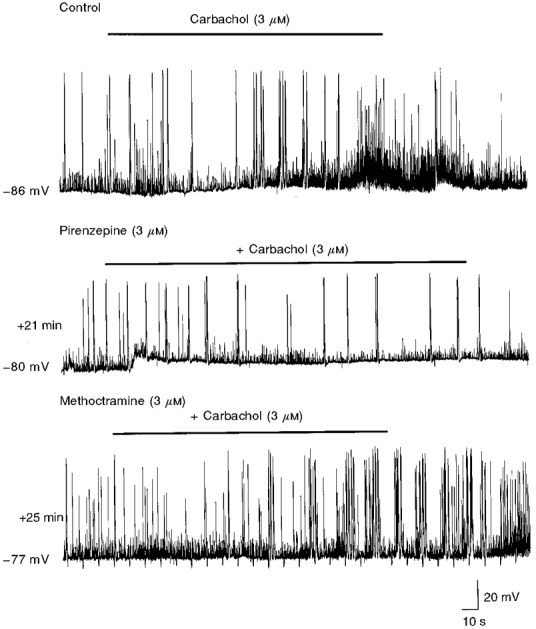

Figure 7. Pirenzepine and methoctramine depress and enhance the action of carbachol, respectively.

Representative tracings recorded from the same neurone at P4, under control conditions and during superfusion of pirenzepine and methoctramine. Note that, in the presence of pirenzepine, the effects of carbachol (bar) on GDPs and on ongoing GABA-mediated synaptic potentials, observed under control conditions, were blocked. In constrast, in the presence of methoctramine, the effects of carbachol were potentiated (GDPs occurred in clusters at higher frequency).

On the other hand, in agreement with previously reported data (Williams & Kauer, 1997; Psarropoulou & Dallaire, 1998), the potentiating effects of carbachol on interictal bursts triggered at P5-P8 by bicuculline were reduced by pirenzepine, indicating an action on the M1 receptor subtype (n = 2; data not shown).

It should be stressed that, as for endogenous ACh, we also failed to observe any direct postsynaptic effect of carbachol on CA3 pyramidal cells. Thus carbachol (1-3 μM) neither induced a membrane depolarization (in the presence of TTX; 1 μM) nor endogenous bursts (in the presence of GABA and ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists; MacVicar & Tse, 1989; Bianchi & Wong, 1994; Williams & Kauer, 1997). This may be due to the loss of some intracellular factor during cell dialysis, after breaking into the whole-cell configuration. In age-matched experiments (n = 6), using conventional intracellular microelectrodes, bath application of carbachol (3 μM) in the presence of TTX (1 μM) induced a 4-12 mV membrane depolarization associated with a 22 ± 6% decrease in membrane conductance (Avignone et al. 1998).

Carbachol enhances the release of GABA from GABAergic interneurones either directly or indirectly through an action on glutamatergic cells

As already mentioned (Bolea et al. 1999), GDPs are generated by the synergistic action of GABA and glutamate acting mainly on the AMPA type of receptor. To see whether the increase in GABA release by carbachol is triggered by glutamate acting on ionotropic types of receptor, carbachol was superfused in the presence of NMDA and/or non-NMDA ionotropic glutamatergic receptor antagonists. Superfusion of CPP (20 μM), an NMDA receptor antagonist, did not modify the effects of carbachol on GDPs, membrane depolarization and increase in synaptic noise (n = 4; data not shown). However, when GYKI 53655 (50 μM), a selective and potent AMPA receptor antagonist (Lerma et al. 1997), was added with CPP, carbachol failed to depolarize the membrane and to increase GDP frequency, and caused only an increase in synaptic noise that often reached the threshold for action potential generation (n = 3; Fig. 8). These data indicate that carbachol controls GABA release mainly by affecting the glutamatergic drive to interneurones. However, the increase in frequency of spontaneous synaptic events produced by carbachol in the presence of CPP and GYKI 53655 strongly suggests that this drug also exerts a direct effect on GABAergic interneurones.

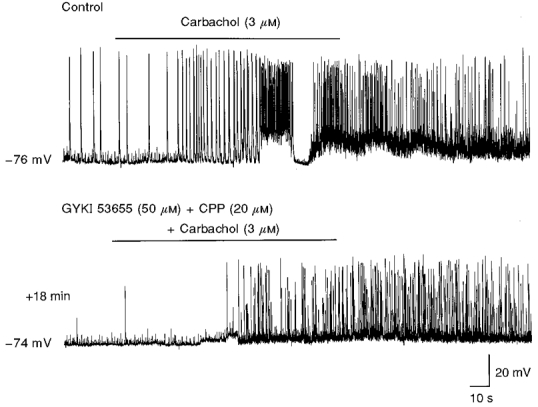

Figure 8. The effects of carbachol on GDPs and membrane depolarization are prevented by GYKI 53655 and CPP.

Recordings from a CA3 pyramidal neurone at P6 in the absence (upper trace) or presence (lower trace) of GYKI 53655 and CPP. NMDA and AMPA receptor antagonists blocked the effects of carbachol (bars) on GDPs and on the membrane depolarization, while they failed to block the effect of this drug on the synaptic noise.

DISCUSSION

Endogenous ACh increases the frequency of GDPs through M1 muscarinic receptor subtypes

The present data clearly show that during the first postnatal week, endogenous ACh, through the activation of muscarinic receptors, is able to modulate the release of GABA, and therefore GDP frequency, in a developmentally regulated way. Evidence in favour of an upregulation of GDP frequency by muscarinic receptor activation is given by the observation that atropine was able to reduce GDP frequency. Also, the experiments with edrophonium strongly suggest that endogenous ACh modulates GABA release, assessed as GDPs. This compound in fact, by blocking AChE, increases the levels of endogenous ACh and enhanced GDP frequency. The observation that, in the presence of edrophonium, tetanic stimulation of cholinergic fibres in the hilus was able to increase GDP frequency or induce a membrane depolarization associated with an increase in synaptic noise, effects prevented by atropine, further supports the role of endogenous ACh in potentiating GABA release. Interestingly, the enhancement of GDP frequency by edrophonium was developmentally regulated, as shown by the increased efficacy of the effects of this drug with age. An increased number of cholinergic fibres and/or muscarinic receptors during the first postnatal week may account for these results. According to Nyakas et al. (1994), at P1, the density of AChE-positive fibres is extremely low; cholinergic fibres undergo a rapid increment during the first postnatal week until they reach a pattern closely resembling the adult age conditions by P10. Conversely, muscarinic receptors are already present at birth, but their number increases sharply from P4 to P15 (Ben-Barak & Dudai, 1979).

The potentiating effect of endogenous ACh on GDP frequency was mediated by M1 muscarinic receptors, as suggested by the ability of low concentrations of pirenzepine to antagonize the effects of edrophonium. This drug in fact reduced the effects of edrophonium with an EC50 value lower than that for methoctramine. M1 receptors have been shown to be preferentially localized on somata and dendrites of pyramidal neurones (Levey et al. 1995). Therefore, activation of M1 receptors would increase the excitability of principal cells probably by suppressing several potassium conductances. These would cause an increase in glutamatergic drive to GABAergic interneurones leading to an enhancement of GDP frequency.

Carbachol enhances and reduces GDP frequency by acting on M1 and M2 receptors, respectively

Similar to edrophonium, the effects of carbachol on principal cells were also developmentally regulated. Carbachol was able to increase GDP frequency, an effect that towards the end of the first postnatal week was associated with an increase in synaptic noise and with a membrane depolarization. These effects were presynaptic as assessed by the fact that: (i) the action of carbachol was not associated with any change in membrane input resistance; and (ii) the membrane depolarization associated sometimes with the increase in GDP frequency was blocked by GYKI 53655 or bicuculline, implying that it was due to the release of glutamate and GABA, following activation of muscarinic receptors localized on principal cells. As for ACh, carbachol would activate muscarinic receptors localized on pyramidal cells or interneurones. An increase in pyramidal cell excitability would enhance the glutamatergic drive to interneurones and this would be ultimately responsible for the increased GABA release. Glutamate released from pyramidal cells would activate AMPA receptors as demonstrated by the ability of GYKI 53655 to block the potentiating effect of carbachol on GDPs. As already reported in adult animals (Pitler & Alger, 1992; Behrends & ten Bruggencate, 1993), carbachol also exerted a direct excitatory action on muscarinic receptors localized on GABAergic interneurones. Thus, although direct recordings from interneurones would be crucial in elucidating this issue, the fact that, in the presence of GYKI 53655, carbachol was still able to increase the frequency of spontaneously occurring GABA-mediated synaptic potentials, strongly suggests a direct effect of this drug on GABAergic interneurones.

In contrast to the present findings, in juvenile (Postlethwaite et al. 1998) or adult rats (Williams & Kauer, 1997), carbachol was shown to produce an oscillatory behaviour that closely resembled epileptic-like phenomena (Traub et al. 1996), which were only disrupted by application of bicuculline. In the present experiments, bicuculline completely abolished GDPs and only towards the end of the first postnatal week was it able to produce sporadic interictal discharges, whose frequency was enhanced by carbachol as in juvenile animals (Psarropoulou & Dallaire, 1998).

As for endogenous ACh, the potentiating effect of carbachol on GDP frequency was mediated by M1 muscarinic receptors as suggested by the ability of pirenzepine to prevent its action. Interestingly, in adult neurones carbachol-induced oscillations were blocked by pirenzepine, but not methoctramine, indicating that in this case also, M1 receptor subtypes were involved (Williams & Kauer, 1997).

Unlike endogenous ACh, carbachol also exerted a clear depressant action on GABA release. This was revealed after blockade of the excitatory effect with pirenzepine. While in juvenile and adult rats, the depressant effect of carbachol on excitatory transmitter release has been well documented (Hounsgaard, 1978; Valentino & Dingledine, 1981; Dutar & Nicoll, 1988; Psarropoulou & Dallaire, 1998), only a modest depressant effect of carbachol on the field EPSP has been observed in the CA1 region of the neonatal hippocampus (Vaknin & Teyler, 1991; Milburn & Prince, 1993). However, the question of which muscarinic receptor type mediates this effect is still controversial (for a review see McKinney, 1993). M1 (Sheridan & Sutor, 1990), M2 (Dutar & Nicoll, 1988; Marchi & Raiteri, 1989), M3 (Hsu et al. 1995) and M4 receptor subtypes (McKinney, 1993) have been suggested. In our case, a non-M1, most probably an M2 receptor subtype, seems to be involved as demonstrated by the experiments in which methoctramine, an M2 antagonist, was able to potentiate the excitatory effect of carbachol, presumably by blocking the inhibitory effect of carbachol on GABA and/or glutamate release (and therefore on the glutamatergic drive to interneurones). The precise mechanism by which the muscarinic agonist diminishes glutamate release from presynaptic nerve endings is not certain. Several mechanisms can be put forward. These include: opening of potassium channels either directly (Egan & North, 1986) or indirectly through an increase in intracellular calcium (Fukuda et al. 1988), inhibition of calcium fluxes through voltage-activated calcium channels (Gähwiler & Brown, 1987; Higashida et al. 1990) and direct depolarization of the terminals. Interestingly, the direct effect of ACh on potassium and calcium channels is mediated by both M2 and M4 receptor subtypes (McKinney, 1993).

It remains to be clarified why carbachol exerts both an excitatory and a depressant action on GABA release whereas only excitatory effects can be detected following activation of muscarinic receptors by endogenous ACh. It is conceivable that carbachol activates both synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors and that the physiological properties of the latter would be different from those of the former.

Physiological relevance

In spite of an early maturation of muscarinic receptors in the hippocampus, compatible with the crucial role played by these receptors in learning and memory processes (Dutar et al. 1995), the action of ACh at the network level is still poorly understood. In the adult hippocampus, carbachol is able to induce a fast (40 Hz) oscillatory activity often nested in theta frequency oscillations (Fisahn et al. 1998; but see also Williams & Kauer, 1997). Like GDPs, this activity is generated by the interplay between GABA and glutamate (Fisahn et al. 1998). GABA released from interneurones would be responsible for network synchronization and for phase locking the oscillatory activity to principal cells (Cobb et al. 1995). Moreover, as for GDPs, non-NMDA ionotropic glutamate receptors would be required for network synchronization (Fisahn et al. 1998). However, while in adults, the activity between pyramidal cells and interneurones is paced by precise temporal patterns of firing of principal neurones and interneurones (Fisahn et al. 1998), in neonates the frequency of oscillations is much slower and is set by intrinsic membrane conductances (Ben-Ari et al. 1989) and electrical coupling between pyramidal cells and interneurones (Strata et al. 1997).

It could be possible therefore, that during a period in which the theta rhythm is not yet developed (Leblanc & Bland, 1979), slow oscillatory activity such as GDPs may play a crucial role in promoting the maturation of glutamatergic synapses (Konnerth et al. 1998). ACh, by activating muscarinic receptors, would further strengthen the action of GABA and would contribute to the fine tuning of hippocampal neural circuitry during early postnatal development.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr E. Sher, Eli Lilly & Co., Windlesham, UK, for the generous gift of GYKI 53655. This work was supported by a grant from Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR) and Ministero dell'Università e Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (MURST).

References

- Auerbach JM, Segal M. Muscarinic receptors mediating depression and long-term potentiation in rat hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:479–493. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avignone E, Molnar M, Berretta N, Casamenti F, Prosperi C, Ruberti F, Cattaneo A, Cherubini E. Cholinergic function in the hippocampus of juvenile rats chronically deprived of NGF. Developmental Brain Research. 1998;109:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00072-8. 10.1016/S0165-3806(98)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrends JC, ten Bruggencate G. Cholinergic modulation of synaptic inhibition in the guinea pig hippocampus in vitro: excitation of GABAergic interneurons and inhibition of GABA-release. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;69:626–629. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.2.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Cherubini E, Corradetti R, Gaiarsa J-L. Giant synaptic potentials in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;416:303–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Khazipov R, Leinekugel X, Caillard O, Gaiarsa J-L. GABAA, NMDA and AMPA receptors: a developmentally regulated ‘ménage à trois. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:523–529. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Barak J, Dudai Y. Cholinergic binding sites in rat hippocampal formation: properties and ontogenesis. Brain Research. 1979;166:245–257. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi R, Wong RKS. Carbachol-induced synchronized rhythmic bursts in CA3 neurons of guinea pig hippocampus in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72:131–138. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolea S, Avignone E, Berretta N, Sanchez-Andres JV, Cherubini E. Glutamate controls the induction of GABA-mediated giant depolarizing potentials through AMPA receptors in neonatal rat hippocampal slices. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999 doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2095. in the Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Trombley P, van den Pol AN. Excitatory actions of GABA in developing hypothalamic neurons. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:451–464. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherubini E, Gaiarsa J-L, Ben-Ari Y. GABA: an excitatory transmitter in early postnatal life. Trends in Neurosciences. 1991;14:515–519. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90003-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb SR, Buhl EH, Halasy K, Paulsen O, Somogyi P. Synchronization of neuronal activity in hippocampus by individual GABAergic interneurons. Nature. 1995;378:75–78. doi: 10.1038/378075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutar P, Bassant MH, Senut MC, Lamour Y. The septohippocampal pathway: structure and function of a central cholinergic system. Physiological Reviews. 1995;75:393–427. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutar P, Nicoll RA. Classification of muscarinic responses in hippocampus in terms of receptor subtypes and second messenger systems: electrophysiological studies in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:4214–4224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04214.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan TM, North RA. Acetylcholine hyperpolarizes cortical neurones by acting on an M2 muscarinic receptor. Nature. 1986;319:405–407. doi: 10.1038/319405a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisahn A, Pike FG, Buhl EH, Paulsen O. Cholinergic induction of network oscillations at 40 Hz in the hippocampus in vitro. Nature. 1998;394:186–189. doi: 10.1038/28179. 10.1038/28179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K, Higashida H, Kubo T, Akiba I, Bujo H, Mishina M, Numa S. Selective coupling with K+ currents of muscarine acetylcholine receptor types in NG 108-15 cells. Nature. 1988;335:355–358. doi: 10.1038/335355a0. 10.1038/335355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gähwiler BH, Brown DA. Muscarine affects calcium-currents in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells in vitro. Neuroscience Letters. 1987;76:301–306. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90419-8. 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90419-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaiarsa J-L, Corradetti R, Cherubini E, Ben-Ari Y. Modulation of GABA-mediated synaptic potentials by glutamatergic agonists in neonatal CA3 rat hippocampal neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;3:301–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaschuk O, Hanse E, Konnerth A. Developmental profile and synaptic origin of early network oscillations in the CA1 region of rat neonatal hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:219–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.219bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashida H, Hashii M, Fukuda K, Caulfield MP, Numa S, Brown DA. Selective coupling of different muscarinic acetylcholine receptors to neuronal calcium currents in DNA-transfected cells. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1990;242:68–74. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1990.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa Y, Sciancalepore M, Stratta F, Martina M, Cherubini E. Developmental changes in spontaneous GABAA-mediated synaptic events in rat hippocampal CA3 neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;6:805–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hounsgaard J. Presynaptic inhibitory action of acetylcholine in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Experimental Neurology. 1978;62:787–797. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(78)90284-4. 10.1016/0014-4886(78)90284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu KS, Huang CC, Gean PW. Muscarinic depression of excitatory transmission mediated by the presynaptic M3 receptors in the rat neostriatum. Neuroscience Letters. 1995;197:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11915-j. 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11915-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda M, Farrant M, Cull-Candy SG. Whole-cell and single channel currents activated by GABA and glycine in granule cells of the rat cerebellum. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;485:419–435. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kása P. The cholinergic systems in brain and spinal cord. Progress in Neurobiology. 1986;26:211–272. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(86)90016-x. 10.1016/0301-0082(86)90016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazipov R, Leinekugel X, Khalilov I, Gaiarsa J-L, Ben-Ari Y. Synchronization of GABAergic interneuronal network in CA3 subfield of neonatal rat hippocampal slices. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;498:763–772. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konnerth A, Durand G, Garaschuk O, Kovalchuk Y. Acivity-dependent maturation of glutamatergic synapses. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;(suppl. 10):1P. [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc OM, Bland BH. Developmental aspects of hippocampal electrical activity and motor behavior in the rat. Experimental Neurology. 1979;66:220–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(79)90076-1. 10.1016/0014-4886(79)90076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinekugel X, Medina I, Khalilov I, Ben-Ari Y, Khazipov R. Ca2+ oscillations mediated by the synergistic excitatory actions of GABAA and NMDA receptors in the neonatal hippocampus. Neuron. 1997;18:243–255. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinekugel X, Tseeb V, Ben-Ari Y, Bregestovski P. Synaptic GABAA activation induces Ca2+ rise in pyramidal cells and interneurons from rat neonatal hippocampal slices. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;487:319–329. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerma J, Morales M, Vicente MA. Glutamate receptors of the kainate type and synaptic transmission. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:9–12. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)20055-4. 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)20055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Edmunds SM, Koliatsos V, Wiley RG, Heiman CJ. Expression of m1-m4 muscarinic receptor proteins in rat hippocampus and regulation by cholinergic innervation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:4077–4092. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-04077.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney M. Muscarinic receptor subtype-specific coupling to second messengers in neuronal systems. In: Cuello AC, editor. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 98. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1993. pp. 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacVicar BA, Tse FWY. Local neural circuitry underlying cholinergic rhythmical slow activity in CA3 area of rat hippocampal slices. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;417:197–212. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi M, Raiteri M. Interaction acetylcholine-glutamate in rat hippocampus: involvement of two subtypes of M-2 muscarinic receptors. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1989;248:1255–1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milburn CM, Prince DA. Postnatal development of cholinergic presynaptic inhibition in the rat hippocampus. Developmental Brain Research. 1993;74:133–137. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90093-p. 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90093-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyakas C, Buwalda B, Kramers RJK, Traber J, Luiten PGM. Postnatal development of hippocampal and neocortical cholinergic and serotoninergic innervation in rat: effects of nitrite-induced prenatal hypoxia and nimodipine treatment. Neuroscience. 1994;59:541–559. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90176-7. 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DF, Boyce LH, Davis MBE, Kriegstein AR. Excitatory GABA responses in embryonic and neonatal cortical slices demonstrated by gramicidin perforated-patch recordings and calcium imaging. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:6414–6423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06414.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitler TA, Alger BE. Cholinergic excitation of GABAergic interneurons in the rat hippocampal slice. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;450:127–142. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwaite M, Constanti A, Libri V. Muscarinic agonist-induced burst firing in immature rat olfactory cortex neurons in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:2003–2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psarropoulou C, Dallaire F. Activation of muscarinic receptors during blockade of GABAA-mediated inhibition induces synchronous epileptiform activity in immature rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1998;82:1067–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00338-2. 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece LJ, Schwartzkroin PA. Effects of cholinergic agonists on immature rat hippocampal neurons. Developmental Brain Research. 1991;60:29–42. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90152-9. 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini R, Valeyev AY, Barker JL, Poulter MO. Depolarizing GABA-activated Cl− channels in embryonic rat spinal and olfactory bulb cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;488:371–386. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatz CJ. Impulse activity and the patterning of connections during CNS development. Neuron. 1990;5:745–756. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90333-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan R, Sutor B. Presynaptic M1 muscarinic cholinoreceptors mediate inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus in vitro. Neuroscience Letters. 1990;108:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90653-q. 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90653-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strata F, Atzori M, Molnar M, Ugolini G, Tempia F, Cherubini E. A pacemaker current in dye-coupled hilar interneurons contributes to the generation of giant GABAergic potentials in developing hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:1435–1446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01435.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strata F, Sciancalepore M, Cherubini E. cAMP-dependent modulation of giant depolarizing potentials by metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;489:115–125. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Whittington MA, Stanford IM, Jefferys JGR. A mechanism for generation of long-range synchronous fast oscillations in the cortex. Nature. 1996;383:621–624. doi: 10.1038/383621a0. 10.1038/383621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaknin G, Teyler TJ. Ontogenesis of the depressant activity of carbachol on synaptic activity in rat visual cortex. Brain Research Bulletin. 1991;26:211–214. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90228-c. 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90228-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino R, Dingledine R. Presynaptic inhibitory effect of acetylcholine in the hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1981;1:784–792. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-07-00784.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH, Kauer JA. Properties of carbachol-induced oscillatory activity in rat hippocampus. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;78:2631–2640. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Ziskind-Conhaim L, Sweet MA. Early development of glycine- and GABA-mediated synapses in rat spinal cord. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:3935–3945. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-03935.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]