Abstract

Colonic afferent fibres were recorded using a novel in vitro preparation. Fibres with endings in the colonic mucosa are described, along with those in muscle and serosa, and their responses to a range of mechanical and chemical luminal stimuli.

Mechanical stimuli were applied to the tissue, which included stretch, blunt probing of the mucosa and stroking of the mucosa with von Frey hairs (10-1000 mg). Chemical stimuli were applied into a ring that was placed over the mechanoreceptive field of the fibre; these were distilled water, 154 and 308 mM NaCl, 100 μM capsaicin, 50 mM HCl, and undiluted and 50 % ferret bile.

Recordings were made from 52 fibres, 12 of which showed characteristics of having endings in the mucosa. Mucosal afferents were sensitive to a 10 mg von Frey hair and were generally chemosensitive to ≥ 1 chemical stimulus.

Ten fibres showed characteristics of having receptive fields in the muscular layer. These fibres responded readily to circumferential stretch, as well as to blunt probing.

Twenty-seven fibres showed characteristics of having endings in the serosal layer. They adapted rapidly to circumferential stretch and responded to blunt probing of the serosa. Fifteen of 19 serosal fibres tested also responded to luminal chemicals.

Three fibres were unresponsive to all mechanical stimuli but were recruited by chemical stimuli.

This is the first characterization of colonic afferent fibres using an in vitro method and the first documentation of afferent fibres with their endings in the mucosa of the colon. These fibres are likely to be important in aspects of colonic sensation and reflex control.

The understanding of sensation in the colon to date has been restricted by the use of too few potential adequate stimuli. Spinal afferent fibres innervating the colon have been characterized previously using the mechanical stimulus of distension (Blumberg et al. 1983; Jänig & Koltzenburg, 1991; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994; Su & Gebhart, 1998). These studies have given rise to a number of different classes of afferent fibres in the spinal nerves based on their responses to colonic distension. The responses of these distension-sensitive fibres to a number of different stimuli, both physiological and noxious, have been well documented.

In contrast to these colonic afferents, in the upper gastrointestinal tract there is a class of afferent fibres that do not respond to distension and show no spontaneous discharge. They respond to mucosal stroking and a number of chemical stimuli in the ferret (Blackshaw & Grundy, 1990), sheep (Cottrell & Iggo, 1984b), cat (Clerc & Mei, 1983) and rat (Clarke & Davison, 1978). It has been shown that there is a close correlation between the function of vagal afferent fibres and the anatomical location of the fibre endings (Grundy, 1988; Berthoud et al. 1995). This class of fibres is therefore considered to have endings in the mucosa. The electrophysiological studies above further demonstrate that the use of distension as the primary stimulus fails to reveal afferent fibres with endings in the mucosa.

Anatomical studies of spinal primary afferent fibres have shown endings in the mucosa of the oesophagogastric junction (Clerc & Mazzia, 1994). No comparable anatomical studies have been performed in the colon. The possibility therefore remains that afferent fibres may innervate the colonic mucosa, but have been overlooked using conventional electrophysiological techniques. A group of afferents, identified only by electrical stimulation, show no spontaneous activity and do not respond to distension of the colon (Jänig & Koltzenburg, 1990, 1991; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994). These afferents are thought to correspond to the ‘silent nociceptors’ reviewed by Cervero (1994) which would be activated only under pathophysiological circumstances. We considered the possibility that at least some of these ‘silent nociceptors’ may, on the contrary, be non-nociceptive, have receptive fields in the mucosa, and respond to physiological stimuli.

The aims of this study were twofold. The first was to establish a novel in vitro model that enables electrophysiological investigation of the functional properties of colonic afferents. The second was to explore the properties of colonic afferents in this model relative to previously documented populations of lumbar colonic afferents. A particular point of interest was whether or not afferents innervate the colonic mucosa and could be subject to the same functional classification as upper gastrointestinal vagal afferent fibres.

METHODS

Animal preparation

All studies were performed within the guidelines of the animal ethics committees of the University of Adelaide and the Institute for Medical and Veterinary Science. Female Sprague-Dawley rats (180-220 g) were sedated with ether and anaesthetized with Nembutal (60 mg kg−1i.p.). After a mid-line laparotomy, 4-5 cm of distal colon lying oral to the rim of the pelvis was removed, along with the lumbar colonic nerves (LCNs) and the neurovascular bundle containing the inferior mesenteric ganglion (IMG), the intermesenteric nerve and the lumbar splanchnic nerves (according to the classification of Baron et al. 1988). The pelvic and hypogastric nerves were not included in the preparation. The tissue was transferred into ice-cold, carbogenated modified Krebs bicarbonate buffer for dissection. Animals were then killed by severance of the abdominal aorta. Composition of the Krebs solution used during dissection was as follows (mM): NaCl, 117.9; KCl, 4.7; NaHCO3, 25; NaH2PO4, 1.3; MgSO4(H2O)7, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.5; sodium butyrate, 1; sodium acetate, 10; glucose, 5.55; and indomethacin (3 μM).

The distal colon was opened longitudinally off-centre to the antimesenteric border in order to orientate LCN insertions along the edge of the opened preparation. The faecal pellets were removed. After this dissection, approximately 1 cm of colon lay below the insertion point most closely related to the IMG and 4 cm lay above this point. Connective tissue was dissected away from the neurovascular bundle. To add support to the preparation, blood vessels were not dissected away from the nerve. The neurovascular bundle was tied and cut at the level of insertion of the artery into the abdominal aorta.

Specific novel features of the preparation

An organ bath was designed specifically to accommodate this preparation. Particular consideration was given to maintaining the viability of the mucosa. For this reason a mixture of short chain fatty acids replaced glucose in the mucosal superfusate (see Scheppach, 1994). Indomethacin (3 μM) was added to regular and modified Krebs solutions to reduce prostaglandin synthesis. Although prostaglandins are thought to reduce colonic epithelial proliferation and thereby to have therapeutic effects in vivo (Craven et al. 1983), effects of local accumulation of prostaglandins, as may occur in vitro, are more incompletely understood. We therefore reduced prostaglandin synthesis with indomethacin as a precautionary measure to avoid possible pro-inflammatory influences often associated with prostaglandins (e.g. Su & Gebhart, 1998). Both surfaces of the tissue were superfused with Krebs solution at a rate of 15 ml min−1. Bath temperature was maintained at 21°C prior to the commencement of the experimental protocol and raised to 32°C only following identification of a viable fibre; this procedure was followed to reduce the rate of deterioration of the mucosa.

Bath layout

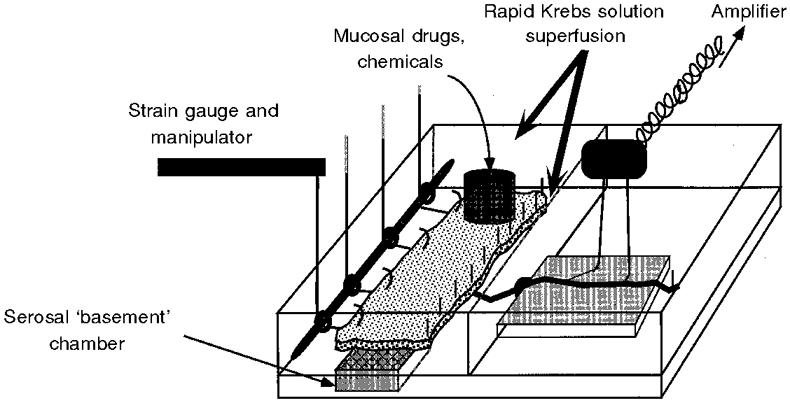

The organ bath was divided laterally into two compartments (Fig. 1). One compartment, superfused with Krebs solution, accommodated the colon. The other, filled with paraffin oil, contained the neurovascular bundle.

Figure 1. Diagram of the organ bath used to record from colonic afferents.

The bath had two compartments. The compartment on the left with two chambers held the colon, which was opened out and placed mucosa side uppermost over the basement chamber. The distal colon was pinned down on the right (mesenteric) side. The left side was attached to a pulley system via silk thread. Modified Krebs solution was superfused over both surfaces of the colon. Drugs were applied locally to the site of the receptive field which was isolated with a metal ring. Single fibre recordings were taken from the intermesenteric-lumbar splanchnic nerve bundle which had been passed through into the right-hand oil-filled compartment.

The colonic compartment was further divided into two chambers, one above the other. The colon was mounted mucosa side up, so that the serosal surface lay directly over the basement chamber. In this position, the insertion points of the LCN lay along the edge of the tissue abutting the wall separating the two compartments of the bath. The smaller basement chamber, over which the colon was pinned, provided superfusion of Krebs solution to the serosal surface of the colon, whilst the chamber above provided superfusion to the mucosal surface of the tissue.

The colon was pinned down along the side closest to the nerves. The opposite edge of the colon was attached at 1 cm intervals to silk threads, which were passed through a pulley system. Each thread could be attached to isometric or isotonic force transducers to measure local motility changes and to apply mechanical stimuli. During baseline conditions the tissue was maintained at approximately in situ longitudinal and circumferential length.

Short chain fatty acids replaced glucose in the mucosal superfusate (2 mM butyrate, 20 mM acetate). Glucose (11.1 mM) was the nutrient in the superfusate of the serosal surface. These superfusates had the following composition in common (mM): NaCl, 117.9; KCl, 4.7; NaHCO3, 25; NaH2PO4, 1.3; MgSO4(H2O)7, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.5; and indomethacin (3 μM).

Nerve recording

The neurovascular bundle was pulled through a hole into the paraffin-filled compartment. The bundle lay over a mirror in a small blister of Krebs solution that was continuous with the solution in the colonic compartment. Under a dissecting microscope, afferent strands were teased away from the neurovascular bundle (which comprised lumbar splanchnic nerves and intermesenteric nerve) and placed on a platinum wire recording electrode (0.25 mm diameter). A reference electrode was positioned in the blister of solution in which the neurovascular bundle lay. Neural activity was differentially amplified (JRAK, Melbourne, Australia), filtered (JRAK, F-1) and displayed on an oscilloscope (Yokogawa DL1300A, Japan). Strands of nerve were discarded or separated into smaller bundles if spontaneous activity of more than three different action potential profiles was observed. Data were not included if the shape and character of two units merged together such that they could not be discriminated confidently by visual inspection of rapid oscilloscope sweeps. Amplified neural recordings were recorded onto hard disk, along with amplified length and/or tension recordings from muscle via a μ1401 interface (CED, Cambridge, UK). Single fibre activity was discriminated off-line for analysis using Spike2 for Macintosh software (CED).

Experimental protocol

Search stimuli for the receptive fields of afferent fibres included three mechanical stimuli. Ungraded circumferential stretch was applied to tissue via the pulley system. The mucosal surface was firmly probed with the blunt end of a glass rod (referred to hereafter as blunt probing). The mucosal surface was also lightly stroked with the end of a fine paint brush. After a receptive field had been identified, the temperature of the bath was increased to 32°C and routine tests were begun. The mechanical sensitivity of fibres was similar at cold and warm temperatures, and no units showed direct thermosensitivity. In earlier experiments, focal electrical stimulation of the colon was used as a search stimulus for afferent endings. This was discontinued because considerable pressure had to be exerted on the tissue by the electrode before an orthodromic action potential could be elicited, which could damage the fragile colonic mucosa. Data on conduction velocity of fibres are therefore unavailable.

Definitions of afferent classifications

The criteria used for classification of afferents were based on those used previously for vagal afferent fibres, particularly those with their endings in the mucosa, and observations already documented for spinal afferent fibres in the colon. All criteria were based on responses to mechanical stimulation.

Mucosal afferents were defined by their ability to respond to stroking with a 10 mg von Frey hair (Page & Blackshaw, 1998), and a lack of response to circumferential stretch or spontaneous activity in the muscle (Blackshaw & Grundy, 1993).

Muscular afferents were defined by their ability to respond readily to circumferential stretch of the tissue with a response that adapted slowly over the duration of the stretch. Traditionally, the activity of muscular afferents has been correlated with the spontaneous activity in the muscle (Cottrell & Iggo, 1984a). As the colonic tissue in this study demonstrated very little spontaneous contractile activity, we were unable to use this criterion in the classification of these afferents.

Serosal afferents were defined by their ability to respond to firm blunt probing on the mucosal surface, but not light mechanical stimuli, and a rapidly adapting (if any) response to circumferential stretch. Another characteristic of these afferents was that they responded at lower mechanical thresholds to stimulation of the reflected serosal surface than stimulation of the mucosal surface. This procedure was, however, not feasible on a routine basis.

Three afferents were recruited in response to locally applied chemicals, but no mechanoreceptive field was identifiable until after recruitment. These afferents are grouped separately.

Other stimuli

Other mechanical stimuli applied manually to the identified receptive field included: change of circumferential length (0-10 mm from tissue resting length) and probing with calibrated von Frey hairs (10-1000 mg).

Chemical stimuli were applied to the site of the receptive field on the mucosal surface by being added into a 1 cm-diameter ring that was placed directly around the receptive field. Chemical stimuli were applied usually for 2 min before being aspirated from the ring. The ring was then lifted and the area of tissue allowed to be superfused with Krebs solution for at least 3 min before re-application of the ring for administration of another stimulus. Chemicals were administered in the following order: distilled water, isotonic NaCl (154 mM), 308 mM NaCl, undiluted or 50 % diluted ferret bile (removed from the gallbladder of anaesthetized ferrets used for other studies in our laboratory), 50 mM HCl and 100 μM capsaicin (Sigma). This order was generally followed so that noxious stimuli were given later in the order to avoid damage or desensitization earlier on in the protocol. Exceptions to this were in 12 fibres where bile was given before 308 mM NaCl. This did not affect the pattern of results when compared with the other protocol. When the same chemical stimuli were administered a second time to the majority of responsive afferents, no desensitization of responses was evident, with the exception of bile (see later). Chemosensitivity was routinely investigated in mucosal and serosal colonic afferents. In order to exclude the possibility that chemically induced responses were secondary to induced muscular activity, sensitive strain gauge recordings of muscular activity were routinely made concurrently with neural recordings. Chemosensitivity in muscular afferents was not as routinely investigated, as our focus in this respect was on mucosal and serosal fibres.

Data analysis

Data were analysed off-line using Spike2 for Macintosh (CED). On the occasions when multiple unitary action potentials were recorded from the same strand of nerve tissue, the software was set up to discriminate between them and generate an independent histogram of the frequency of activity in each unit. The software was also set up to track the changes in the action potential profile of a unit over the course of a study. Spontaneous discharge was measured as the mean discharge over 1 min as soon as possible after identification of units and equilibration of the bath. Responses to chemicals were counted when a maintained>50 % increase in discharge above basal levels occurred. To be counted, smaller responses than this (> 25 %) had to meet the additional criteria that they were superimposed on a particularly steady level of resting activity and were highly reproducible on repetition of the stimulus. Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m.

RESULTS

General topographical features of colonic afferent fibres

Forty-nine afferents identifiable as single units were recorded that had a single mechanoreceptive field (Table 1). Mechanoreceptive fields were 1-4 mm2 in size, according to mapping with a blunt probe, and were clustered along the mesenteric border of the colon (Fig. 2A). They were found above and below the point of exit of the main neurovascular bundle and therefore ascended or descended in the lumbar colonic nerves before projecting centrally.

Table 1. Summary of responses of individual afferents.

| Unit | Probe | Stretch | Stroke (1000 mg) | Stroke (10 mg) | NaCl (308 mM) | Bile | HCl (50 mM) | Capsaicin (100 μM) | Spontaneous activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serosal | |||||||||

| 72-1 | + | 0 | + | 0 | — | — | — | — | + |

| 82-1 | + | 0 | + | 0 | — | — | — | — | + |

| 96-3 | + | 0 | + | 0 | — | — | — | — | + |

| 100-2 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | + |

| 50-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | + |

| 59-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | + |

| 135-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | + |

| 116-3 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | + |

| 130-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 0 | + |

| 130-3 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 0 | + |

| 123-1 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | — | — | — | + |

| 138-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | — | — | + | + |

| 128-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | — | —- | + | + |

| 125-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | — | — | + | + |

| 114-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | — | — | + |

| 71-4 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | — | + | 0 | + |

| 74-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | — | 0 | + | 0 |

| 69-2 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | + |

| 83-1 | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | + | — | + |

| 87-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | — | 0 | + |

| 48-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | — | + |

| 55-2 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + |

| 61-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| 61-2 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

| 64-1 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + |

| 64-2 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + |

| 68-1 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Muscular | |||||||||

| 15-1 | + | + | — | — | — | — | — | — | + |

| 1-1 | + | + | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| 50-3 | + | + | — | — | — | — | — | — | + |

| 102-2 | + | + | — | — | — | — | — | — | + |

| 59-2 | + | + | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | + |

| 106-4 | + | + | + | 0 | — | — | — | — | + |

| 71-3 | + | + | — | — | 0 | — | + | 0 | + |

| 57-1 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 116-1 | + | + | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| 130-2 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | — | — | 0 | + |

| Mucosal | |||||||||

| 91-1 | + | 0 | + | + | — | — | — | — | 0 |

| 121-2 | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | — | — | — | 0 |

| 137-1 | + | 0 | + | + | + | — | — | — | 0 |

| 106-2 | + | 0 | + | + | + | — | — | — | + |

| 106-3 | + | 0 | + | + | + | — | — | — | + |

| 47-2 | + | — | + | + | + | — | + | — | + |

| 69-1 | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | + |

| 55-1 | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 58-1 | + | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 58-2 | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 76-1 | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 84-1 | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Other chemosensitive afferents | |||||||||

| 114-2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | — | — | + |

| 125-6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | — | — | + | + |

| 121-1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | — | + | + | 0 |

+, response to a stimulus or presence of spontaneous activity; 0, no response or activity; —, stimulus not tested. Afferents are grouped in classifications of serosal, muscular, mucosal and other (see Methods for classification criteria). Mechanical sensitivity is shown as that present at the beginning of studies. Responses to both 50% and undiluted bile are combined.

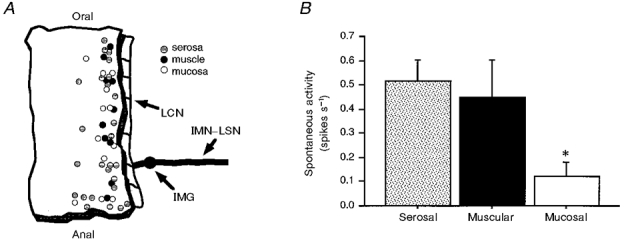

Figure 2. Location of afferent receptive fields and resting discharge rates of afferent fibres.

A, diagram of the location of receptive fields of all afferents in the serosa, mucosa and muscle in the distal colon. Each circle represents the site, not the size of the receptive field. Shaded circles represent serosal receptive fields, filled circles represent muscular receptive fields and open circles represent mucosal receptive fields. Abbreviations: LCN, lumbar colonic nerve; IMG, inferior mesenteric ganglion; IMN-LSN, intermesenteric nerve and lumbar splanchnic nerves. B, resting discharge rate of each category of afferent fibre. Discharge was measured at the beginning of each experiment upon equilibration to experimental conditions. Mucosal afferents had significantly lower rates of resting activity than both serosal and muscular afferents (* P < 0.01 vs. serosal and P < 0.05 vs. muscular).

Mucosal afferents

Twelve of the 49 fibres described above fitted the classification criteria for mucosal afferents. Each afferent had only one receptive field. The size of the receptive fields for mucosal afferent fibres was generally smaller than those for other classes, not exceeding 2 mm2, although precise quantification was not possible using blunt probing. Seven afferents initially showed no resting activity. Three of these did not develop any resting activity over the course of the study, and four showed sporadic resting activity by the end of the study. The other five mucosal afferents were all spontaneously active, but none with a rate exceeding 1 spike s−1 (mean of spontaneously active units, 0.30 ± 0.09 spikes s−1; see Fig. 2B for data on all mucosal afferents).

All mucosal afferents responded to stroking and were sensitive to the full range of von Frey hairs when moved across their receptive field (10, 50, 200 and 1000 mg; e.g. Fig. 3). Responses were of short latency and short duration, not exceeding 4 s. Eleven out of 12 fibres tested responded to blunt probing, but none responded to circumferential stretch of the tissue. Mechanical sensitivity of mucosal afferents was not influenced observably when tested after recovery from responses to chemical stimuli.

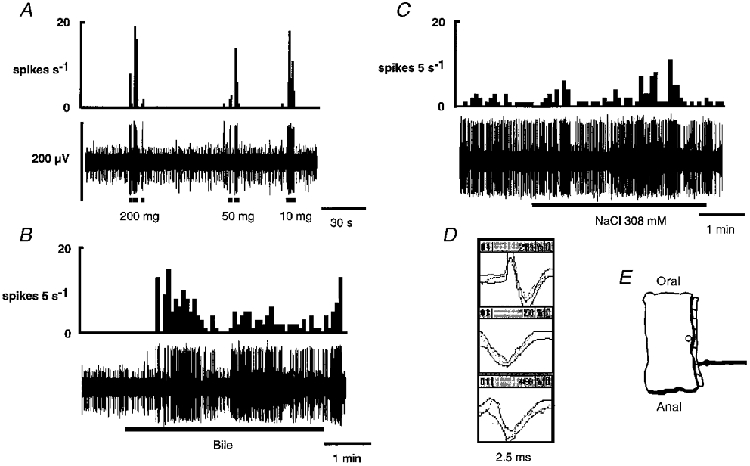

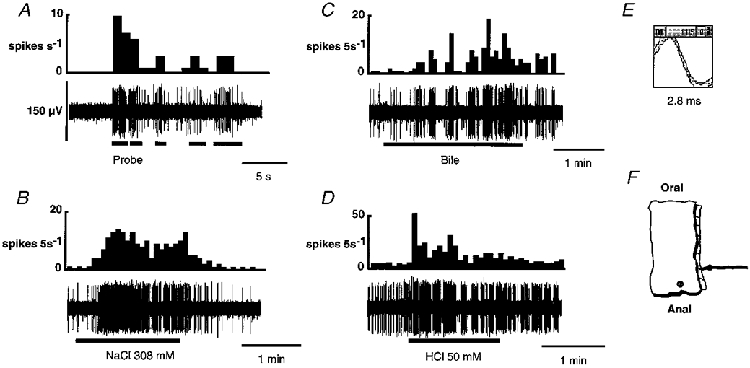

Figure 3. Response of a mucosal afferent to calibrated von Frey hairs and two chemical stimuli: 308 mM NaCl and undiluted ferret bile.

In A-C, the integrated discharge of the fibre of interest is shown directly above the raw record of activity in the nerve strand. Three fibres were active in this strand, the discriminator templates for which are shown in D. The fibre of interest (top template) had the largest amplitude (175-200 μV). One other fibre (middle template) was subsequently investigated and included in the serosal fibre data. The last fibre (bottom template) was not investigated. A, a brief, rapidly adapting response occurred with each application of the von Frey probe. The fibre had no spontaneous activity at this stage. B, the fibre responded to the application of bile with a latency of 40 s. The response was slowly adapting and was maintained after reintroduction of the normal superfusate. C, hypertonic NaCl (308 mM) was applied to the tissue 32 min after application of bile. Basal resting discharge had increased after the application of bile upon which the response to hypertonic NaCl was superimposed. Hypertonic NaCl evoked a slowly adapting response with a latency of 10 s. This fibre was also investigated with 50 mM HCl and 100 μM capsaicin, but did not respond to these stimuli (data not shown). An illustration of the precise location of the receptive field of this fibre is shown in E. In this and subsequent figures, the calibration bar for the raw record of activity in A also applies to the other continuous raw records shown.

Nine out of 11 mucosal afferents responded to at least one chemical stimulus. There were no responses to distilled water or normal saline (154 mM). Nine fibres responded to hypertonic saline (308 mM), with a mean latency of 43 ± 12 s. Three out of seven fibres responded to 50 mM HCl. The latencies for these responses varied considerably (4, 20 and 60 s). Three of six afferents tested responded to ferret bile: two responded to 50 % diluted bile (osmolarity not exceeding 300 mosmol l−1), and one responded to undiluted bile. These responses were not reproducible, indicating desensitization. One of six fibres responded to 100 μM capsaicin, after a latency of 40 s. There was no apparent pattern in the combinations of chemicals that evoked responses in mucosal fibres. For the combinations of chemicals that activated individual fibres, see Table 1.

Serosal afferents

Twenty-seven fibres fitted the criteria for classification as serosal afferents. Three of these were initially silent but developed activity after application of one or more chemical stimuli. All other afferents had resting activity, of which approximately equal numbers increased, decreased and maintained their initial level of activity during the remainder of the study. The rate of resting activity in active fibres was 0.58 ± 0.09 spikes s−1 (see Fig. 2B for data on all serosal afferents).

Blunt probing was the most effective mechanical stimulus and all fibres demonstrated high threshold responses (e.g. Fig. 4). Where feasible, the sensitivity of these fibres to tactile stimulation on the serosal surface rather than the mucosal surface was tested as a confirming variable and was found to show greater sensitivity. This also revealed a small (2-4 mm2) punctate receptive field. One afferent responded to ungraded circumferential stretch with a short initial burst of action potentials which was not sustained for the duration of the stretch. Of 27 fibres tested, six responded to a 1000 mg von Frey hair applied to the mucosal surface and one of these to a 200 mg von Frey hair. There were no responses to mucosally applied 50 or 10 mg von Frey hairs.

Figure 4. Response of a serosal fibre to circumferential stretch and blunt probing.

In A and B, the integrated record of the activity of the fibre is shown directly above the raw record. Three fibres were active in this strand; the unit of interest is the one with the largest amplitude (140-150 μV) (C). A single action potential was all that was evoked by circumferential stretch (A), whereas a robust discharge was seen during probing (B). An illustration of the precise location of the receptive field of this fibre is shown in D.

Of 19 serosal afferents tested with mucosally applied chemical stimuli, 15 responded (e.g. Fig. 5). Eleven of these responded to more than one chemical stimulus. Distilled water and normal saline (154 mM) were without effect. Thirteen fibres responded to hypertonic saline (308 mM), with a mean latency of 43 ± 2 s. Four serosal afferents responded to 50 % ferret bile, two responded to undiluted bile, and five responded to neither. In all cases, after the initial response to bile at either concentration, no further response to bile could be elicited even when the concentration was increased, indicating desensitization. However, desensitization was not seen to other stimuli. Three out of 10 fibres responded to 50 mM HCl, with latencies of 3, 3 and 60 s. Six of 15 fibres responded to capsaicin (100 μM). The latency of response for these fibres was 37 ± 13 s.

Figure 5. Response of a serosal afferent to one mechanical and three chemical stimuli.

In A-D, the integrated record of the activity of the fibre is shown directly above the raw record. Only the unit of interest was active in this strand. A, the unit responded to probing with a burst of firing that resolved when the stimulus was removed. Subsequent responses to probing were of lower intensity than the initial response. Moving the probe in and out of the bathing solution regularly produced artefacts. This can be observed where the raw record appears not to correspond with the integrated record. B, the fibre had a slowly adapting response to hypertonic NaCl (308 mM) with a latency of 22 s. The response was not sustained after washout with Krebs solution and the firing rate quickly returned to resting activity. C, the onset of the response to bile had a long latency of 52 s whereupon the firing pattern changed to short intense bursts of activity that had not been observed until this time. Washing the tissue with Krebs solution caused a prompt decrease in the intensity of the firing, but the bursting pattern was maintained for a further 60 s. D, the short latency (4 s) response to 50 mM HCl began with an intense burst of activity that was not sustained for the duration of the stimulus. Rather, a series of rapid, discrete bursts of firing was initiated that was sustained for the remaining 8 min of the recording period (not shown). E shows the template for this unit. F, an illustration of the location of the receptive field.

Muscular afferents

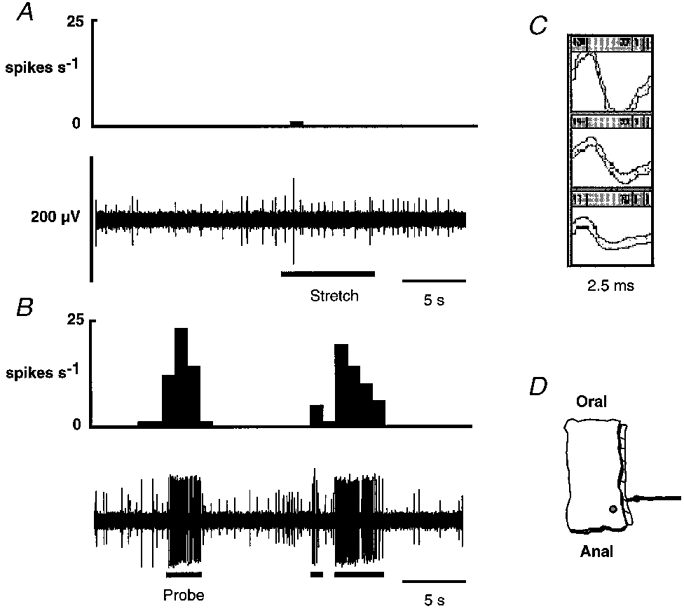

Ten fibres were classified as muscular afferents. Seven of these had spontaneous activity (see Fig. 2B for group data) and responded readily to ungraded circumferential stretch (e.g. Fig. 6). The response was maintained for the duration of the stimulus but ceased as the stimulus was removed. This activity could not be correlated with muscular contractions as little or no spontaneous muscular activity was seen in this tissue. On two occasions responses to chemical stimuli were observed in muscular fibres which were unaccompanied by increases in muscular activity, and would therefore appear to be direct. In one of these cases, the fibre responded to 50 mM HCl after a latency of 30 s, and the other fibre responded to 308 mM NaCl after a latency of 73 s. Chemical sensitivity was not, however, routinely investigated in the remainder of the muscular afferents.

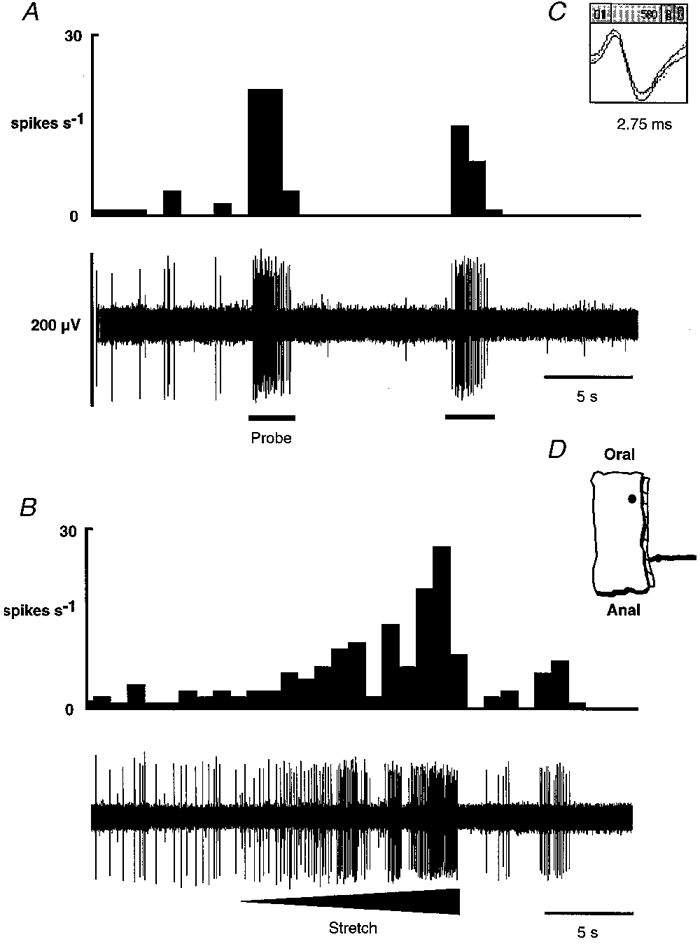

Figure 6. Response of a muscular afferent to blunt probing and circumferential stretch.

In A and B, the integrated record of the activity of the fibre is shown directly above the raw record. Only the unit of interest was active in this strand. This unit had a low level of spontaneous activity. It responded to probing (A) with a burst of firing that stopped abruptly when the stimulus was removed. There was a subsequent reduction in the spontaneous activity. This fibre had a slowly adapting response to circumferential stretch (B). The degree of distortion was gradually increased throughout the stimulus, resulting in a gradual increase in the rate of firing. When the stretch was released, a brief reduction in activity below resting level occurred. The shape of the action potential is shown in C. The location of the receptive field is illustrated in D.

Other chemosensitive afferents

Three afferent fibres initially had no mechanoreceptive fields and were not spontaneously active, but were recruited during application of chemicals to the receptive field and surrounding tissue of another fibre under investigation. Subsequent reinvestigation of mechanical sensitivity revealed responses to probing in all cases, and in one afferent a 10 mg von Frey hair was tested and a response evoked. Chemical sensitivity of these afferents is shown in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

This study provides the first description of primary afferent fibres with receptive fields in the colonic mucosa. These were found along with muscular and serosal afferents in the lumbar splanchnic and intermesenteric nerves of female Sprague-Dawley rats. This study is also the first to investigate the functional properties of afferents following this pathway in the rat. These findings were made using a novel in vitro technique which allowed improved access to the colon over traditional in vivo techniques. In small mammals, in vitro techniques have proved invaluable in improving understanding of the functional properties of afferents in the rat stomach (Wei et al. 1995) and small intestine (Cervero & Sharkey, 1988), guinea-pig ureter (Cervero & Sann, 1989) and airways (Fox et al. 1993), ferret oesophagus and stomach (Page & Blackshaw, 1998), and mouse skin (Koltzenburg et al. 1997) and colon (L. A. Blackshaw, A. J. Page & P. A. Lynn, unpublished observations). In addition to substantiating findings made in vivo, in vitro studies have revealed previously unidentified properties or even populations of afferents, as was the case in the present study.

Mucosal afferents

The delicate colonic mucosa is prone to rapid deterioration in vitro. It has specialized nutrient needs often neglected in traditional whole-mount in vitro preparations. Considerable care was taken in the current study to prolong mucosal viability, encouraging an environment conducive to recording from intact mucosal afferents. This may have contributed to our discovery of colonic mucosal afferents.

All of the mucosal afferents in this study responded to fine mechanical stimulation with a 10 mg von Frey hair. They did not respond to circumferential stretch of the tissue - the adequate stimulus for colonic mechanosensitive afferent fibres in all previous studies, in which circumferential stretch was achieved by distension with fluid or a balloon (Blumberg et al. 1983; Haupt et al. 1983; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994; Su & Gebhart, 1998). Upper gastrointestinal mucosal afferent fibres recorded in vitro (Page & Blackshaw, 1998) have a comparable response to von Frey hairs to that of the colonic mucosal afferent fibres described in the present study and similarly show no response to circumferential stretch. Colonic mucosal afferent fibres had either no resting discharge or a low rate of resting discharge (< 0.5 Hz), similar to the findings of Page & Blackshaw (1998) and those of in vivo studies of gastroduodenal mucosal afferents (Clarke & Davison, 1978; Cottrell & Iggo, 1984b; Blackshaw & Grundy, 1990, 1993). There is also agreement with regard to the finding that mucosal afferents show no initial spontaneous discharge but develop spontaneous activity over the course of the study. These dissimilarities with previously described colonic afferent fibres and similarities with upper gastrointestinal mucosal vagal afferent fibres support the classification of the new group of colonic afferent fibres described here as mucosal afferent fibres.

With the exception of one fibre, all colonic mucosal afferents showed some chemosensitivity when tested, usually to a range of different stimuli. The prevalence of chemosensitivity amongst colonic mucosal afferents contrasts with that of vagal mucosal afferents recorded by our group in the ferret oesophagus in vitro (Page & Blackshaw, 1998), where only a small proportion of the mucosal fibres responded to luminally applied stimuli. Differences between the choice of stimuli for the present rat study and the previous ferret study may account for the differences observed, in addition to species and site along the gut. There are very little in vitro data from other studies with which to compare the chemosensitivity of mucosal afferent fibres. No pattern emerges from the combinations of chemical stimuli which evoked responses in mucosal afferents in this study, and therefore there are no apparent distinct subpopulations of mucosal afferent fibres. It may be concluded at this stage that chemosensitivity in colonic mucosal afferents is heterogeneous. Our choice of the range of chemical stimuli used to investigate mucosal afferents was made in order to deliver stimuli that may be encountered in the colonic lumen during physiological or mildly pathophysiological circumstances; bile is normally reabsorbed in the small intestine, but in diarrhoea it reaches most of the colon (Edwards et al. 1989); acidic conditions are generated by bacterial fermentation, and hyperosmotic conditions by fluid absorption. Capsaicin was used in order to determine whether subpopulations of afferents could be coded according to their capsaicin sensitivity, which was not evident from the data gathered.

Mucosal afferents described in the present study share many features with a population of afferents found in the urinary bladder (Häbler et al. 1990, 1993) and colon (see Sengupta & Gebhart, 1998), referred to as ‘silent nociceptors’ (McMahon & Koltzenburg, 1990) and reviewed by Cervero (1994); they are normally insensitive to distension, show no resting activity, respond to chemical stimuli and may develop spontaneous firing after exposure to chemical stimuli during a study. We are unable to show at this stage whether these two names actually refer to the same population of afferents, because we did not include the range of physiological and pathophysiological stimuli necessary for accurate classification. However, the possibility that mucosal afferents and visceral silent nociceptors are functionally analogous cannot be excluded. Ironically, direct evidence for a role for silent nociceptors in visceral nociception is currently lacking, and recent reviews have used the more descriptive term ‘mechanically insensitive’ to classify them (McMahon et al. 1995). Certainly, our data would indicate a non-nociceptive role for mucosal afferents due to their responsiveness to non-noxious stimuli, but we would challenge the use of the term ‘mechanically insensitive’ because mucosal stroking is a hitherto untested yet adequate mechanical stimulus and should therefore be included in future visceral afferent classifications.

Mucosal afferents from the colon have not been reported previously, although those further down the gut in the rectal and anal canal have been demonstrated where somatic and visceral domains meet (Clifton et al. 1976; Koley et al. 1984; Jänig & Koltzenburg, 1991; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994). Colonic mucosal afferents have probably been encountered before, but their adequate stimulus not found. In reports of the rat (Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994) and cat (Jänig & Koltzenburg, 1991) pelvic nerve and cat lumbar splanchnic nerves (Blumberg et al. 1983), from 33 to 95 % of afferents identified by nerve stimulation that were otherwise silent were insensitive to colonic distension or extraluminal mechanical stimuli. In most cases these were believed to end in the colon, and it was speculated that they correspond to either the silent nociceptors described above, or with antidromically activated postganglionic sympathetic motoneurones. We found that approximately a quarter of the afferents in the present study were insensitive to distension and had receptive fields in the mucosa, and we therefore suggest that many of the distension-insensitive afferents described previously may also belong to this class.

The role of colonic mucosal afferents in sensation has not been studied extensively in humans, probably because until now there was no evidence for their existence. Nevertheless, the sensation of chemical and tactile stimulation of the colon and rectum is apparent from the studies of Edwards et al. (1989) and Ritchie (1973), although this may be normally below threshold for conscious perception unless accompanied by a distension stimulus (Edwards et al. 1989) or disease involving visceral hypersensitivity (Ritchie, 1973). These findings are substantiated by preliminary data from our laboratory showing potentiation of rat lumbar dorsal horn neuronal responses to colonic distension following intraluminal bile infusion (L. K. Andrew & L. A. Blackshaw, unpublished observations).

Serosal afferents

Our findings on serosal afferents concur with descriptions of lumbar spinal serosal afferents in the literature (Blumberg et al. 1983; Haupt et al. 1983), in which the response to circumferential stretch was either absent or seen only at the onset of the stretch, whereupon it showed no relationship to tension or length of the muscle. This short burst of firing was consistent with the initial movement of the tissue either shifting the mesentery or rubbing the receptive field against the basement mesh of the bath. The serosal fibres described in this study responded to firm probing of the luminal surface and responded at a lower threshold to probing of the reflected serosal surface, although this was not always possible to confirm and depended on the location of the receptive field being at either end of the preparation. This problem is similar to that encountered by Blumberg et al. (1983) in locating serosal receptive fields on the posterior aspect of the cat colon in vivo.

Many serosal afferents showed some chemosensitivity to stimuli applied to the luminal surface at the location of the receptive field. These responses were initiated across the wall of the tissue rather than by leakage around the sides of the preparation, which was prevented by the effective seal between compartments (confirmed using dye). It is possible that responses of serosal afferents may be due to secondary effects on the tissue beyond our control such as release of inflammatory mediators. This is on the whole unlikely because our emphasis was biased towards using stimuli that could occur naturally in the lumen in the intact animal under both physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Chemosensitivity of serosal afferents has been established previously in vivo to bradykinin, capsaicin, ischaemia and hypertonic saline administered extraluminally (Haupt et al. 1983; Longhurst et al. 1984), indicating a role for these afferents in transmission of signals related to noxious and inflammatory events. The finding that intraluminal stimuli such as bile and low concentrations of HCl and NaCl stimulated serosal afferents suggests that there may be a hitherto unexplored role for serosal afferents in the sensing of the chemical composition of the luminal contents.

Muscular afferents

Low-threshold lumbar colonic afferent fibres sensitive to small changes in intraluminal pressure are well documented (Blumberg et al. 1983; Haupt et al. 1983). The muscular afferents recorded here showed similar properties in that they consistently responded to circumferential distortion of the colon. However, we have preliminary evidence that they do not respond to graded increases in circumferential strain (P. A. Lynn, unpublished observation), which is the stimulus that should most closely correlate with increased intraluminal pressure. Therefore, whilst these fibres were obviously sensitive to changing length, how this relates to changes in tension is unresolved. An interesting precedent may be in guinea-pig colon from which the mechanosensory input to prevertebral ganglia may be proportional to volume rather than intraluminal pressure (Anthony & Kreulen, 1990). We have undertaken a further study of these fibres with respect to the stretch response and its relationship to length and tension.

Distribution of receptive fields

Receptive fields of all three types of afferent were clustered along the mesenteric border of the colon. This was partly the result of technical features of the preparation, because the colon was opened longitudinally off-centre. This procedure would inevitably sever the peripheral processes of afferent fibres as they projected circumferentially around the colon to the anterior aspect (the far left in Fig. 2A). This does not, however, account for the relatively small numbers of receptive fields found in the centre (corresponding to the antimesenteric side) of the preparation. Thus we must conclude that there is a natural bias to the innervation of the colon by these types of fibre. This confirms an observation made by Blumberg et al. (1983) on muscular and serosal/mesenteric afferents in the cat colon. We observed only one receptive field per afferent fibre. This is in agreement with some previous studies (e.g. Blumberg et al. 1983; Haupt et al. 1983), but not others (e.g. Morrison, 1973). Because our preparation included only the distal colon with little attached mesentery, it is not possible to make direct comparison because connections to other receptive fields on adjacent organs may have been severed.

Origins of fibres recorded

The extrinsic afferent innervation of the distal colon arises from the pelvic and splanchnic nerves, with central endings in the spinal cord, and from the vagal nerves with central endings in the dorsal medulla. Our recordings were from fibres in the intermesenteric and lumbar splanchnic nerves, which together contain predominantly lumbar spinal afferents (Baron et al. 1988). Sacral afferents follow a separate anatomical pathway in the pelvic nerves (Baron & Jänig, 1991; Jänig & Koltzenburg, 1991), and vagal fibres are relatively sparse at the level of the colon (Berthoud et al. 1991, 1997; Altschuler et al. 1993). The pathway taken by vagal fibres is not known. Therefore, in addition to the most likely event that our recordings are from lumbar spinal afferents, other possible extrinsic origins are apparent. As well as extrinsic fibres, our recordings may have been from axons originating from second-order enteric neurones projecting out of the gut (intestinofugal fibres). Intestinofugal fibres are believed to project as far as the IMG (Weems & Szurszewski, 1977; Keef & Kreulen, 1990), but not as far as our recording site. Enteric neurones projecting through the IMG to the spinal cord were thought to exist in the rectum but not in the colon (Doerffler-Melly & Neuhuber, 1988; Neuhuber et al. 1993). However, more recently there has been evidence that, in the rat, a small number (approximately 20 per 5 mm length of colon) of intestinofugal fibres pass through the IMG and project into the intermesenteric nerves, particularly those arising from the distal colon (Luckensmeyer & Keast, 1995). Therefore, the possibility that some of our recordings are from intestinofugal fibres cannot be excluded, but proportionally these would be a small minority.

Basic properties of colonic afferents

Spontaneous activity was present in a subgroup of each category of afferents in this study. Where spontaneous activity was present, it was of low frequency. Analysis of group data on the three categories we encountered showed that mucosal afferents had significantly lower rates of resting discharge. This is similar to differences previously reported between mucosal and other classes of fibres in the vagal innervation (Cottrell & Iggo, 1984a, b; Blackshaw & Grundy, 1990, 1993; Page & Blackshaw, 1998). Muscular and serosal afferents had similar resting discharge rates to those previously reported in the cat lumbar splanchnic innervation (Blumberg et al. 1983). Spontaneous activity in some mucosal and serosal afferents increased over the course of the study, and this was generally associated with application of chemical stimuli. A previous study of spontaneous activity that developed in this way (Blackshaw & Grundy, 1993) showed that it could be abolished by administration of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, indicating a role for endogenous release of 5-hydroxytryptamine in influencing mucosal afferent excitability. What causes development of increased spontaneous activity in rat colon in vitro is the subject of a further study in our laboratory.

For methodological reasons we did not determine the conduction velocity of afferents in this study. Although these data would have provided an additional classification criterion for future studies, it is unlikely to be of functional significance to the type of sensory information encoded. Previous studies of lumbar spinal afferents in the cat have shown no correlation between conduction velocity, resting discharge and distension threshold (Blumberg et al. 1983). Prior studies on lumbar colonic afferents in the rat are lacking, but a detailed investigation of rat sacral colonic afferents similarly showed no correlation between conduction velocity and functional properties (Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994). These authors did find an increased proportion of Aδ fibres in the afferent innervation of the anal mucosa compared with the colon, but these presumably belonged to the somatic sensory supply. Otherwise, 81 % of colonic afferents in the study of Sengupta & Gebhart (1994) were unmyelinated.

In conclusion, the development of an in vitro technique for the study of colonic afferents has led to the first demonstration of mucosal endings in the colon. The mucosal afferents described in the present study closely resemble their counterparts in the upper gastrointestinal vagal innervation. The existence of mucosal afferent fibres in the colon suggests a complexity in sensation from the colon that is as yet unexplored. The precise physiological roles of these mucosal fibres in visceral sensation and reflexes are subjects for further study in our laboratory. Serosal afferents with high mechanical thresholds were recorded that showed chemosensitivity to luminally applied stimuli. Muscular afferents had similar properties to those previously described in the colon.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. P. A. Lynn is a recipient of a Royal Adelaide Hospital Dawes Post-Graduate Scholarship.

References

- Altschuler SM, Escardo J, Lynn RB, Miselis RR. The central organization of the vagus nerve innervating the colon of the rat. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:502–509. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90419-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony TL, Kreulen DL. Volume-sensitive synaptic input to neurons in guinea pig inferior mesenteric ganglion. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;259:G490–497. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.3.G490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Jänig W. Afferent and sympathetic neurons projecting into lumbar visceral nerves of the male rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1991;314:429–436. doi: 10.1002/cne.903140302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Jänig W, Kollmann W. Sympathetic and afferent somata projecting in hindlimb nerves and the anatomical organization of the lumbar sympathetic nervous system of the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1988;275:460–468. doi: 10.1002/cne.902750310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Carlson NR, Powley TL. Topography of efferent vagal innervation of the rat gastrointestinal tract. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:R200–207. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.1.R200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Kressel M, Raybould HE, Neuhuber WL. Vagal sensors in the rat duodenal mucosa: distribution and structure as revealed by in vivo DiI-tracing. Anatomy and Embryology. 1995;191:203–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00187819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Patterson LM, Willing AE, Mueller K, Neuhuber WL. Capsaicin-resistant vagal afferent fibers in the rat gastrointestinal tract: anatomical identification and functional integrity. Brain Research. 1997;746:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshaw LA, Grundy D. Effects of cholecystokinin (CCK-8) on two classes of gastroduodenal vagal afferent fibre. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1990;31:191–202. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(90)90185-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshaw LA, Grundy D. Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine on discharge of vagal mucosal afferent fibres from the upper gastrointestinal tract of the ferret. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1993;45:41–50. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg H, Haupt P, Jänig W, Kohler W. Encoding of visceral noxious stimuli in the discharge patterns of visceral afferent fibres from the colon. Pflügers Archiv. 1983;398:33–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00584710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero F. Sensory innervation of the viscera: peripheral basis of visceral pain. Physiological Reviews. 1994;74:95–138. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero F, Sann H. Mechanically evoked responses of afferent fibres innervating the guinea-pig's ureter: an in vitro study. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;412:245–266. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero F, Sharkey KA. An electrophysiological and anatomical study of intestinal afferent fibres in the rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;401:381–397. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GD, Davison JS. Mucosal receptors in the gastric antrum and small intestine of the rat with afferent fibres in the cervical vagus. The Journal of Physiology. 1978;284:55–67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc N, Mazzia C. Morphological relationships of choleragenoid horseradish peroxidase-labeled spinal primary afferents with myenteric ganglia and mucosal associated lymphoid tissue in the cat esophagogastric junction. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1994;347:171–186. doi: 10.1002/cne.903470203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc N, Mei N. Vagal mechanoreceptors located in the lower oesophageal sphincter of the cat. The Journal of Physiology. 1983;336:487–498. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton GL, Coggeshall RE, Vance WH, Willis WD. Receptive fields of unmyelinated ventral root afferent fibres in the cat. The Journal of Physiology. 1976;256:573–600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell DF, Iggo A. Tension receptors with vagal afferent fibres in the proximal duodenum and pyloric sphincter of sheep. The Journal of Physiology. 1984a;354:457–475. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell DF, Iggo A. Mucosal enteroceptors with vagal afferent fibres in the proximal duodenum of sheep. The Journal of Physiology. 1984b;354:497–522. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven PA, Saito R, DeRubertis FR. Role of local prostaglandin synthesis in the modulation of proliferative activity of rat colonic epithelium. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1983;72:1365–1375. doi: 10.1172/JCI111093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerffler-Melly J, Neuhuber WL. Rectospinal neurons: evidence for a direct projection from the enteric to the central nervous system in the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1988;92:121–125. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CA, Brown S, Baxter AJ, Bannister JJ, Read NW. Effect of bile acid on anorectal function in man. Gut. 1989;30:383–386. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.3.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AJ, Barnes PJ, Urban L, Dray A. An in vitro study of the properties of single vagal afferents innervating guinea-pig airways. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;469:21–35. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy D. Speculations of the structure/function relationship for vagal and splanchnic afferent endings supplying the gastrointestinal tract. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1988;22:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(88)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häbler HJ, Jänig W, Koltzenburg M. Activation of unmyelinated afferent fibres by mechanical stimuli and inflammation of the urinary bladder in the cat. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;425:545–562. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häbler HJ, Jänig W, Koltzenburg M. Receptive properties of myelinated primary afferents innervating the inflamed urinary bladder of the cat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;69:395–405. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt P, Jänig W, Kohler W. Response pattern of visceral afferent fibres, supplying the colon, upon chemical and mechanical stimulation. Pflügers Archiv. 1983;398:41–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00584711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänig W, Koltzenburg M. On the function of spinal primary afferent fibres supplying colon and urinary bladder. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1990;30:S89–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(90)90108-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänig W, Koltzenburg M. Receptive properties of sacral primary afferent neurons supplying the colon. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1991;65:1067–1077. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.5.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keef KD, Kreulen DL. Peripheral nerve pathways to neurons in the guinea pig inferior mesenteric ganglion determined electrophysiologically after chronic nerve section. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1990;29:113–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(90)90177-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koley J, Sen Gupta J, Koley BN. Sensory receptors and their afferents in the caudal sympathetic nerve of the domestic duck. British Poultry Science. 1984;25:173–186. doi: 10.1080/00071668408454856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltzenburg M, Stucky CL, Lewin GR. Receptive properties of mouse sensory neurons innervating hairy skin. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;78:1841–1850. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst JC, Kaufman MP, Ordway GA, Musch TI. Effects of bradykinin and capsaicin on endings of afferent fibers from abdominal visceral organs. American Journal of Physiology. 1984;247:R552–559. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.247.3.R552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckensmeyer GB, Keast JR. Distribution and morphological characterization of viscerofugal projections from the large intestine to the inferior mesenteric and pelvic ganglia of the male rat. Neuroscience. 1995;66:663–671. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00599-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon SB, Dmitrieva N, Koltzenburg M. Visceral pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1995;75:132–144. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M. Novel classes of nociceptors: beyond Sherrington. Trends in Neurosciences. 1990;13:199–201. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JFB. Splanchnic slowly adapting mechanoreceptors with punctate receptive fields in the mesentery and gastrointestinal tract of the cat. The Journal of Physiology. 1973;233:349–361. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhuber WL, Appelt M, Polak JM, Baier-Kustermann W, Abelli L, Ferri GL. Rectospinal neurons: cell bodies, pathways, immunocytochemistry and ultrastructure. Neuroscience. 1993;56:367–378. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90338-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page AJ, Blackshaw LA. An in vitro study of the properties of vagal afferent fibres innervating the ferret oesophagus and stomach. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;512:907–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.907bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J. Pain from distension of the pelvic colon by inflating a balloon in the irritable colon syndrome. Gut. 1973;14:125–132. doi: 10.1136/gut.14.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheppach W. Effects of short chain fatty acids on gut morphology and function. Gut. 1994;35:S35–38. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.1_suppl.s35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Characterization of mechanosensitive pelvic nerve afferent fibers innervating the colon of the rat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;71:2046–2060. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. The sensory innervation of the colon and its modulation. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 1998;14:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Su X, Gebhart GF. Mechanosensitive pelvic nerve afferent fibers innervating the colon of the rat are polymodal in character. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:2632–2644. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.5.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weems WA, Szurszewski JH. Modulation of colonic motility by peripheral neural inputs to neurons of the inferior mesenteric ganglion. Gastroenterology. 1977;73:273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei JY, Adelson DW, Tache Y, Go VLW. Centrifugal gastric vagal afferent unit activities: another source of gastric ‘efferent’ control. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1995;52:83–97. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)00146-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]