Abstract

To investigate mechanisms responsible for the presynaptic inhibitory action mediated by the axonal group II metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) at the mossy fibre-CA3 synapse, we used a quantitative fluorescence measurement of presynaptic Ca2+ in mouse hippocampal slices.

Bath application of the group II mGluR-specific agonist (2S,1′R,2′R,3′R)-2-(2,3-dicarboxycyclopropyl)glycine (DCG-IV, 1 μM) reversibly suppressed the presynaptic Ca2+ influx (to 55·2 ± 4·6 % of control, n= 5) as well as field EPSPs recorded simultaneously (to 3·1 ± 2·0 %). Presynaptic fibre volley was not affected by 1 μM DCG-IV.

A quantitative analysis of the inhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ influx and field EPSP suggested that DCG-IV suppressed the field EPSP to a greater extent than would be expected if the suppression were solely due to a decrease in the presynaptic Ca2+ influx.

DCG-IV at 1 μM suppressed the mean frequency (to 73·8 ± 3·9 % of control, n= 11), but not the mean amplitude (to 97·0 ± 3·5 %), of miniature EPSCs recorded from CA3 neurones using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique.

These results suggest that group II mGluR-mediated suppression is due both to a reduction of presynaptic Ca2+ influx and downregulation of the subsequent exocytotic machinery.

The type 2 metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR2) has been shown to suppress synaptic transmission at the hippocampal mossy fibre-CA3 synapse by presynaptic mechanisms (Yokoi et al. 1996; Kamiya et al. 1996). Presynaptic mGluR2 may play an important role in activity-dependent regulation of synaptic strength, since it has been demonstrated that a use-dependent increase in glutamate concentration activates these receptors (Scanziani et al. 1997) and is responsible for presynaptically induced long-term depression (LTD) at this synapse (Yokoi et al. 1996; Tzounopoulos et al. 1998).

As for mechanisms responsible for the mGluR-mediated presynaptic modulation, two possibilities should be considered: reduction of action potential-induced presynaptic Ca2+ influx and inhibition of the release machinery downstream of Ca2+ influx. Using simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic whole-cell recordings from a calyx synapse in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB), it has been demonstrated that the inhibition of Ca2+ influx accounts solely for the suppression of transmitter release in experiments using the group III mGluR-specific agonist L(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (L-AP4; Takahashi et al. 1996). Similar results were obtained for mGluR-mediated presynaptic inhibitory action in the neonatal hippocampal CA1 synapse (Baskys & Malenka, 1991; Yoshino & Kamiya, 1995).

Recently, electron microscopic analysis using specific antibodies raised against mGluR2 has revealed that immunolabelling of mGluR2, which belongs to the group II mGluRs, is found in preterminal rather than terminal portions of axons, whereas group III receptors (mGluR4/6-8) are located predominantly in presynaptic active zones (Yokoi et al. 1996; Shigemoto et al. 1997). The contrasting localization of group II and group III presynaptic mGluRs (i.e. extrasynaptic vs. synaptic, respectively) raised the question of whether extrasynaptic group II mGluR affects Ca2+ influx at the presynaptic active zones. To elucidate mechanisms underlying the mGluR2-mediated presynaptic inhibitory action, we examined the effect of (2S,1′R,2′R,3′R)-2-(2,3-dicarboxycyclopropyl)glycine (DCG-IV), a selective agonist of group II mGluRs (mGluR2/3), on presynaptic Ca2+ influx at the mossy fibre synapse in hippocampal slice preparations.

Part of the present work has been reported elsewhere in abstract form (Kamiya & Ozawa, 1998b).

METHODS

Slice preparations and field potential recordings

Methods for preparing hippocampal slices and recording field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) induced by mossy fibre stimulation have been reported previously (Kamiya et al. 1996) with the exception that mice, instead of rats, were used in this study. All experiments were carried out according to the guidelines laid down by the Animal Care and Experimentation Committee of the Gunma University, Showa Campus. Briefly, Balb/c mice (10-18 days old) were anaesthetized with ether and decapitated. The brain was quickly removed and immersed in an ice-cold oxygenated standard solution composed of (mM): NaCl, 127; KCl, 1·5; KH2PO4, 1·2; MgSO4, 1·3; CaCl2, 2·4; NaHCO3, 26; and glucose 10. The solution was saturated with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2. Hippocampi were dissected out and transverse sections (0·3-0·4 mm thick) were prepared. These were incubated in standard Ringer solution at 32°C for at least 40 min, and then transferred into an observation chamber which was continuously superfused at a rate of approximately 2 ml min−1 with the standard solution. In some experiments, modified solutions in which the concentration of CaCl2 was decreased and that of MgSO4 was increased were used. Electrical stimuli (100 μs duration, ∼500 μA intensity) were delivered every 5 min through a tungsten concentric bipolar electrode inserted into the stratum granulosum of the dentate gyrus, and field EPSPs were recorded in the stratum lucidum of the CA3 region with a glass microelectrode of about 10 μm tip diameter filled with extracellular solution. All recordings were made at 28-30°C. All values are given as the means ±s.e.m.

Loading of Ca2+ indicator dye and fluorescence recordings

The relatively low affinity Ca2+ indicator rhod-2 (Minta et al. 1989) instead of the higher affinity dye fura-2 (Regehr & Tank, 1991) was used to load presynaptic structures of the mossy fibre-CA3 synapse (see also Kamiya & Ozawa, 1998a). Axons and presynaptic boutons of the mossy fibre pathway were labelled by pressure-ejecting the membrane-permeable Ca2+ indicator rhod-2 AM into the extracellular space of the stratum lucidum, where the axon bundle is located (Fig. 1A). The labelling solution contained 0·1 mM rhod-2 AM dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) and 2 % Pluronic F-127. The membrane-permeable rhod-2 AM is expected to enter into the axons and diffuse or be transported to the presynaptic terminals after conversion into the membrane-impermeable form of rhod-2 by intracellular esterase. About 2 h after ejection, fluorescence (excited at 510-560 nm and monitored above 580 nm) emerging from an area with a diameter of about 100 μm in the stratum lucidum, approximately 500 μm distal from the ejection site, was detected with a single photodiode. The output of the photodiode was I-V converted, amplified and low-pass filtered (see below). In some experiments, an intensified CCD camera (IC-100, Photon Technology International, South Brunswick, NJ, USA) was used to record fluorescence images of the single mossy fibre terminals. The output of the photodiode was I-V converted and filtered at 200 Hz with an 8-pole Bessel filter (FLA-01, Cygnus Technology, Delaware Water Gap, PA, USA) to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. The fluorescence signals and extracellular field potentials were digitized with a 12-bit A/D converter (Digidata 1200A, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) and acquired at 10 kHz using Axoscope software (Axon Instruments). The video images were digitized with Digidata 2000 Image Lightning and acquired with Axon Imaging Workbench software (Axon Instruments).

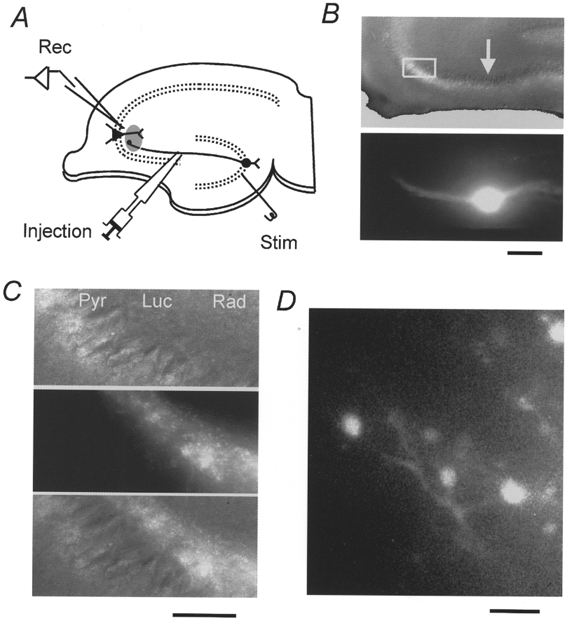

Figure 1. Selective labelling of the mossy fibre pathway with the Ca2+ indicator rhod-2 AM.

A, schematic diagram showing the experimental arrangement. Membrane-permeable rhod-2 AM was pressure-ejected into the stratum lucidum, resulting in selective loading of the presynaptic terminals through the mossy fibre pathway. Fluorescence from the labelled region, which had a diameter of about 100 μm and was about 500 μm away from the ejection site, was measured with a single photodiode. B, transmission (upper) and fluorescence (lower) images of the slice in which the mossy fibres were labelled with the Ca2+ indicator rhod-2 AM. Images were obtained with a × 10 objective. A bright fluorescent band extended bidirectionally away from the ejection site (arrow), reflecting the antero- as well as retrograde labelling of the mossy fibre pathway. C, transmission (upper), fluorescence (middle) and superimposed (bottom) images (× 40 objective) of the area indicated by the box in B. These panels show that fluorescence is localized only in the stratum lucidum (Luc). Pyr, stratum pyramidale. Rad, stratum radiatum. D, fluorescence image obtained with a × 100 objective. Relatively large mossy fibre terminals of approximately 3-5 μm in diameter are seen at the single bouton level. Scale bars represent 200 μm (B), 50 μm (C) and 10 μm (D), respectively.

Recording of miniature EPSCs

Miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) were recorded at -70 mV in the whole-cell configuration in the presence of 0·5 μM tetrodotoxin to block evoked synaptic transmission and 100 μM picrotoxin to suppress miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs). Patch pipettes were filled with an internal solution (pH 7·2) containing (mM): caesium gluconate, 150; EGTA, 0·2; NaCl, 8; Hepes, 10; Mg2+ATP, 2; and lidocaine N-ethyl bromide quaternary salt (QX-314), 5. The membrane currents were filtered at 1 kHz and collected for 120 s in each condition; events were analysed off-line using Mini Analysis Program software (Jaejin Software, Leonia, NJ, USA). An amplitude threshold of 8-10 pA as well as an area threshold (typically 10 fC) were used as criteria to detect events. The amplitude histogram was binned in 2 pA intervals. The effects of DCG-IV on amplitude and inter-event intervals of mEPSCs were assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (Manabe et al. 1992).

Chemicals

Drugs used in this study were: DCG-IV, 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), and D(-)2-aminophosphonopentanoic acid (D-AP5), all from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK); rhod-2 AM (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan); Pluronic F-127 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA); and QX-314 and DMSO from Sigma.

RESULTS

Presynaptic Ca2+ measurement at the mossy fibre-CA3 synapse

To measure changes in the presynaptic Ca2+ concentration, we selectively loaded presynaptic structures of the mossy fibre synapse with rhod-2 (Minta et al. 1989; see also Kamiya & Ozawa, 1998a), a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator. Following local ejection of the membrane-permeable form of rhod-2, rhod-2 AM, into the stratum lucidum at the edge of the CA3 region (Fig. 1A), a bright fluorescent band extended bi-directionally away from the injection site, and could be seen in parallel with the pyramidal cell layer under low magnification (× 10 objective; Fig. 1B). The fluorescent band was considered to represent labelled mossy fibres, since the labelled structure had the characteristic appearance of mossy fibres (Claiborne et al. 1986; Regehr & Tank, 1991; Yu & Brown, 1994) for the following reasons: first, the fluorescence was restricted to the stratum lucidum, where mossy fibres exist (Fig. 1C) and, in addition, large boutons of 3-5 μm diameter, which were located en passant along the labelled fibres, could be seen under higher magnification (× 100 objective, Fig. 1D). The characteristic morphology and defined anatomical localization indicate the selective presynaptic loading of mossy fibres with the Ca2+ indicator.

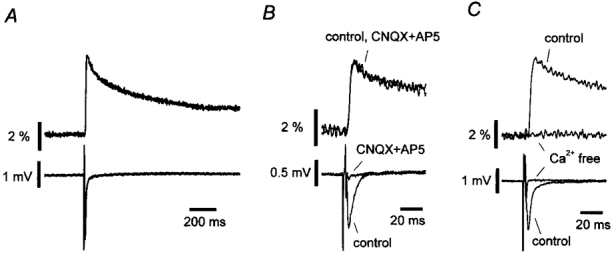

Transient increases in rhod-2 fluorescence and field EPSPs evoked by single electrical stimuli to the mossy fibre pathway were recorded simultaneously. The representative Ca2+ transient and field EPSP are shown in Fig. 2A. To verify the presynaptic origin of the observed Ca2+ transients, we examined the effects of the glutamate receptor antagonists CNQX (10 μM) and D-AP5 (25 μM), which block postsynaptic AMPA and NMDA receptors, respectively. The field EPSPs were blocked completely, whereas Ca2+ transients were not affected (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the Ca2+ transients arose exclusively from the presynaptic structure. Furthermore, the Ca2+ transients were abolished in a Ca2+-free solution containing 1 mM EGTA (Fig. 2C), indicating that the increase in fluorescence intensity results from Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space rather than from Ca2+ release from intracellular stores.

Figure 2. Representative records of the presynaptic Ca2+ transient (pre[Ca2+]t) and field EPSP evoked by a single stimulus to the mossy fibre pathway.

A, time courses of the pre[Ca2+]t (upper trace) and field EPSP recorded simultaneously (lower trace). Ca2+ signals were measured as relative fluorescence changes (ΔF/F), where F is the resting fluorescence level and ΔF is the peak amplitude of fluorescence change caused by the stimulus. B, effects of a mixture of AMPA and NMDA receptor antagonists (10 μM CNQX and 25 μM D-AP5) on the Ca2+ transient (upper trace) and field EPSP (lower trace). C, effects of Ca2+-free solution containing 1 mM EGTA.

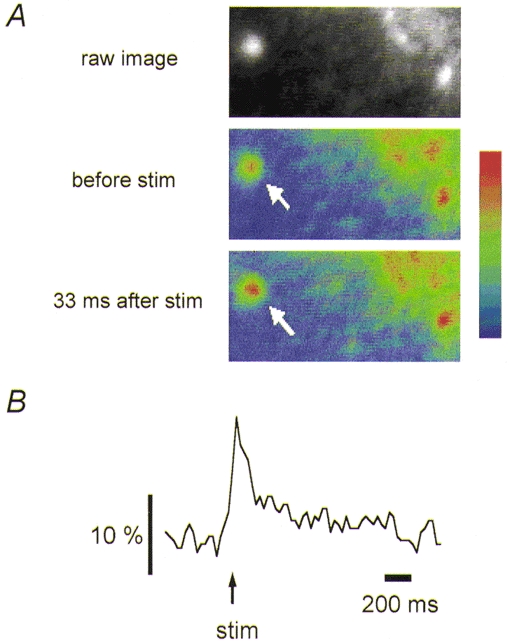

Since this loading technique labels axons as well as presynaptic boutons, we tried to determine the origin of the fluorescent transients using video-rate recording of fluorescence images at the single bouton level. A clear fluorescence increase was detected at single presynaptic boutons (Fig. 3A), although the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio was reduced (Fig. 3B). At high-speed (30 Hz) recording of the images, the axon-like structures were barely resolved, and we could not measure axonal Ca2+ transients with appreciable S/N ratios. For these experiments, we measured the Ca2+ transient from the terminal located on the edge of the fluorescence band to minimize the background fluorescence from the labelled structures staying out of focus.

Figure 3. Representative Ca2+ transient at single mossy fibre terminals evoked by a single electrical stimulation.

A, fluorescence images obtained before and after a single stimulus to the mossy fibres. Pseudo-colour illustration shows an increase in fluorescence at the single bouton level (arrow). B, trace representing the time course of the fluorescence change (ΔF/F) at the single bouton.

It has been shown that a number of calretinin-immunoreactive interneurones exist throughout the stratum lucidum of the CA3 region (Gulyás et al. 1992), and that Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors are expressed in some of these neurones (Tóth & McBain, 1998). Therefore one can argue that the Ca2+ signal detected in Fig. 3 is derived from such interneurones. However, this possibility is ruled out, since the diameter of the round Ca2+ spot was 3-5 μm, whereas that of the soma of the calretinin-immunoreactive interneurone was 12-16 μm (Gulyás et al. 1992).

Suppression of presynaptic Ca2+ influx by the group II mGluR agonist DCG-IV

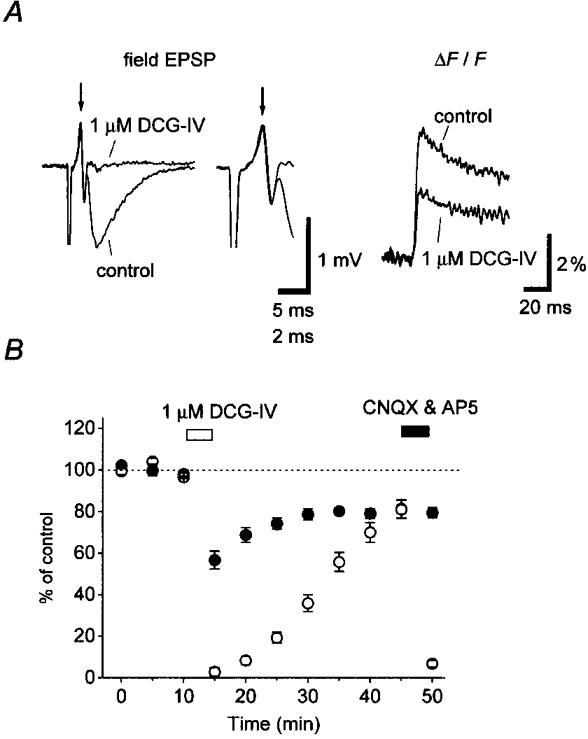

We next examined the effect of DCG-IV, a selective agonist of group II mGluRs, on the presynaptic Ca2+ transient (pre[Ca2+]t) and field EPSP. As reported previously (Yokoi et al. 1996; Kamiya et al. 1996), DCG-IV at 1 μM almost completely suppressed field EPSPs (to 3·1 ± 2·0 %, n= 5) without affecting presynaptic volley (Fig. 4A and B). Pre[Ca2+]t recorded simultaneously was also suppressed by 1 μM DCG-IV. However, the extent of suppression was only to 55·2 ± 4·6 % of control.

Figure 4. Effects of DCG-IV, a group II-selective mGluR agonist, on field EPSP and pre[Ca2+]t.

A, representative records of field EPSP (left) and pre[Ca2+]t (right) obtained before and during application of 1 μM DCG-IV. Note that the presynaptic fibre volley potential (arrow) was not affected by DCG-IV application. This is clearly shown in the inset, which represents an expanded view of the traces in the left panel. B, time course of DCG-IV effect. The relative amplitudes of pre[Ca2+]t (ΔF/F, •) and field EPSP (○) were plotted as a function of time (mean ±s.e.m., n= 5). Field EPSPs were abolished by application of CNQX and D-AP5.

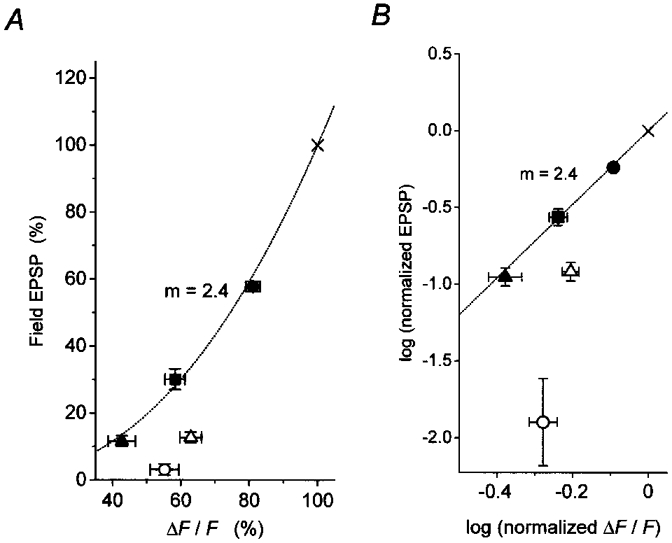

This quantitative difference in the effects of DCG-IV on EPSP and pre[Ca2+]t may be due to the non-linear relationship between presynaptic Ca2+ influx and transmitter release (Dodge & Rahamimoff, 1967; Landò & Zucker, 1994) and/or additional modulation on the exocytotic machinery downstream of Ca2+ influx (Dittman & Regehr, 1994; see also Wu & Saggau, 1997). To determine whether the suppression of pre[Ca2+]t could account for the reduction of EPSP, we examined the effects of low-Ca2+ solutions which would suppress synaptic transmission exclusively by reducing presynaptic Ca2+ influx. Application of low-Ca2+ solution containing 0·6 mM Ca2+ and 3·1 mM Mg2+ for 5 min reduced field EPSP and pre[Ca2+]t to 11·6 ± 1·6 % and 42·7 ± 4·0 % (n= 4) of those recorded in the normal solution (containing 2·4 mM Ca2+ and 1·3 mM Mg2+), respectively. In the solution containing 1·2 mM Ca2+ and 2·5 mM Mg2+, field EPSP and pre[Ca2+]t were suppressed to 29·0 ± 3·2 % and 58·3 ± 3·3 % (n= 5), respectively. In the solution containing 1·8 mM Ca2+ and 1·9 mM Mg2+, field EPSP and pre[Ca2+]t were reduced to 57·8 ± 1·5 % and 81·1 ± 2·1 % (n= 4), respectively. The relationship between field EPSP and pre[Ca2+]t was non-linear, and could be approximated by a power function: EPSP ∞[Ca2+]m (Mintz et al. 1995; Wu & Saggau, 1997). The data were plotted on the double logarithmic scale in Fig. 5B, and the slope (m) was estimated to be 2·4. When the relations between field EPSP and pre[Ca2+]t during application of DCG-IV were plotted on the same graphs in Fig. 5, they deviated markedly from those obtained by changing Ca2+ concentrations of the external solution (Fig. 5A and B). The field EPSP was suppressed by DCG-IV to a greater extent than would be expected if its effect were due solely to a decrease in Ca2+ influx. These results suggest that DCG-IV might also suppress the exocytotic machinery downstream of Ca2+ influx (Dittman & Regehr, 1994; Wu & Saggau, 1997).

Figure 5. Relationship between pre[Ca2+]t and EPSPs during application of DCG-IV, or during reduction in [Ca2+]o.

A, data obtained during application of 0·3 μM (▵, n= 6) and 1 μM DCG-IV (○, n= 5) were compared with those obtained during replacement of the control saline (2·4 mM Ca2+, ×) with low [Ca2+]o solution containing either 0·6 mM Ca2+ (▴, n= 4), 1·2 mM Ca2+ (▪, n= 5) or 1·8 mM Ca2+ (•, n= 4). B, double logarithmic plot of the data in A. The linear regression line for low [Ca2+]o data (filled symbols) was drawn as a dotted line, and the slope (m) was estimated to be 2·4. The corresponding power-law fit is also shown in A as a dotted curve. Each plot is expressed as the mean ±s.e.m.

Suppression of mEPSC frequency by DCG-IV

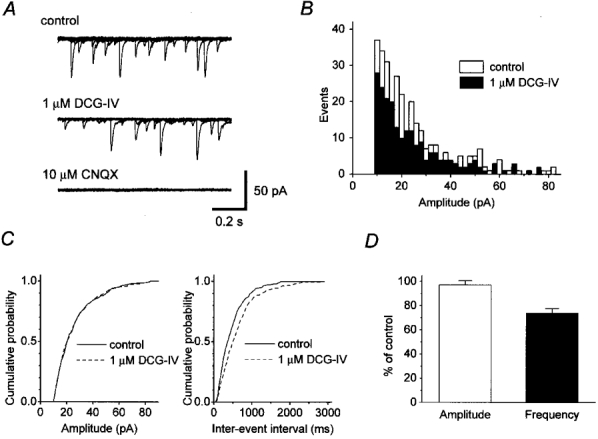

To test directly if the exocytotic machinery is also downregulated by DCG-IV, we examined the effect of this drug on mEPSCs recorded from visually identified CA3 neurones in the stratum pyramidale using a whole-cell patch-clamp technique (Jonas et al. 1993). Typical spontaneous events were recorded at a holding potential of -70 mV in the presence of tetrodotoxin (0·5 μM) and picrotoxin (100 μM), which block Na+ channel-dependent action potentials and GABAA receptor-mediated events, respectively (Fig. 6A, top trace). The events detected under these conditions were regarded as mEPSCs mediated by spontaneously released glutamate, because the non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist CNQX (10 μM), which completely blocked evoked mossy fibre EPSCs, abolished these events (Fig. 6A, bottom trace). Application of 1 μM DCG-IV reduced the frequency of mEPSCs (Fig. 6A, middle trace), while the amplitudes of the mEPSCs were little affected. The amplitude histogram (Fig. 6B) shows that DCG-IV reduced the frequency of mEPSCs without much affecting the amplitude distribution. This conclusion was also supported by a cumulative amplitude histogram (Fig. 6C, left panel), which shows no clear difference between control and DCG-IV data. These results suggest that postsynaptic responsiveness is not significantly affected by DCG-IV (Kamiya et al. 1996). On the other hand, a cumulative plot of inter-event intervals (Fig. 6C, right panel) shows a significant difference between control and DCG-IV data (P < 0·05, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). On average, the mean frequency decreased during 1 μM DCG-IV application to 73·8 ± 3·9 % of the control frequency, whereas the mean amplitude was little affected (97·0 ± 3·5 % of control, n= 11, Fig. 6D). These results suggest that mGluR activation downregulates the release machinery subsequent to Ca2+ influx.

Figure 6. Effect of DCG-IV on miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) recorded from CA3 neurones.

A (top panel), representative traces of mEPSCs recorded at a holding potential of -70 mV in the presence of 0·5 μM tetrodotoxin and 100 μM picrotoxin. Six 1 s traces were superimposed. Middle panel, traces during exposure to 1 μM DCG-IV. Bottom panel, traces during application of 10 μM CNQX. B, amplitude histograms for recordings under control conditions (□) and in the presence of 1 μM DCG-IV (▪). Under each condition, data were collected for 120 s, events were detected with a threshold of 10 pA and binned in 2 pA intervals. C, cumulative probability plots of mEPSC amplitudes (left) and inter-event intervals (right) for control (continuous line) and DCG-IV (dotted line) data. The difference in inter-event intervals was significant (P < 0·05, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). D, pooled data from 11 experiments for relative changes in mean amplitude (□) and mean frequency (▪).

Differential inhibition of multiple subtypes of presynaptic calcium channels by DCG-IV

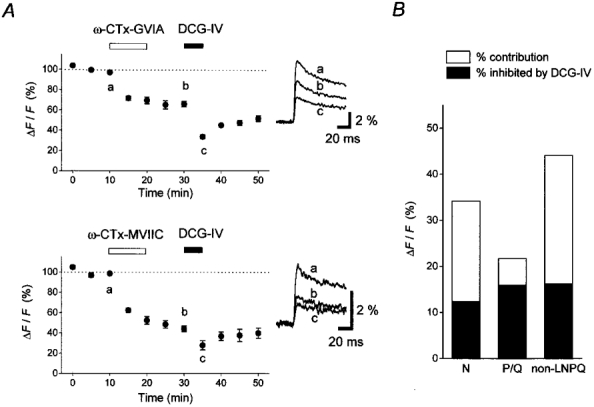

Finally, we examined whether presynaptic mGluR2 couples with specific Ca2+ channel subtypes, using subtype-specific toxins. Since N-type and P/Q-type, but not L-type, Ca2+ channels have been demonstrated to be involved in transmitter release from mossy fibre terminals (Kamiya et al. 1988; Castillo et al. 1994; Yamamoto et al. 1994), we tried to determine the relative contribution of each Ca2+ channel subtype to the DCG-IV effects. To determine the relative involvement of N-, P/Q- and other (non-LNPQ)-type channels in pre[Ca2+]t, we examined the effect of ω-conotoxin GVIA (ω-CTx-GVIA), an N-type channel specific blocker (Takahashi & Momiyama, 1993), and ω-conotoxin MVIIC (ω-CTx-MVIIC), which blocks N- and P/Q-type channels but not non-LNPQ-type channels (Wheeler et al. 1994). As shown in Fig. 7A, application of 1 μM ω-CTx-GVIA reduced pre[Ca2+]t to 65·8 ± 2·7 % of the control level (n= 5, Fig. 7A, upper panel). Subsequent application of 1 μM DCG-IV further reduced pre[Ca2+]t, to 33·5 ± 1·8 % of the control level. In another set of experiments, 1·5 μM ω-CTx-MVIIC reduced pre[Ca2+]t to 44·1 ± 2·7 % of the control level, and subsequent DCG-IV application further inhibited it to 27·8 ± 4·6 % of the control level (n= 5, Fig. 7A, lower panel). From these data, we estimated that N-type channels (ω-CTx-GVIA-sensitive component) carried 34·2 % of the total Ca2+ increase. Accordingly, P/Q-type (ω-CTx-GVIA insensitive but ω-CTx-MVIIC sensitive) and non-LNPQ-type channels (ω-CTx-MVIIC insensitive) were estimated to carry 21·7 % and 44·1 % of the total Ca2+ increase, respectively (Fig. 7B, □) (Wu & Saggau, 1994; Mintz et al. 1995).

Figure 7. Effect of DCG-IV after blocking different subtypes of presynaptic Ca2+ channels with type-specific blockers.

A, time courses of the relative amplitudes of pre[Ca2+]t (ΔF/F). Upper panel, N-type channel specific blocker ω-CTx-GVIA (1 μM) and DCG-IV (1 μM) were applied during the period as indicated (n= 5). Lower panel, ω-CTx-MVIIC (1·5 μM), which blocks N- and P/Q-type but not non-LNPQ-type channels and DCG-IV (1 μM) were added in succession (n= 5). Insets are representative traces recorded at the time indicated in the graph. B, relative contributions of three pharmacologically distinct subtypes of Ca2+ channels to the pre[Ca2+]t are shown by □. The fraction inhibited by DCG-IV in each subtype of Ca2+ channel was calculated and is indicated by ▪.

On the basis of the above estimates, we calculated the fraction of each subtype component inhibited by 1 μM DCG-IV, according to the method described by Wu & Saggau (1994). We assumed that 1 μM DCG-IV inhibited a fraction α of N-type, a fraction β of P/Q-type and a fraction γ of non-LNPQ-type Ca2+ channels. Since application of DCG-IV alone suppressed pre[Ca2+]t by 44·8 % (100 % - 55·2 %, Fig. 4B), we have:

| (1) |

DCG-IV suppressed pre[Ca2+]t by 32·3 % (65·8 % - 33·5 %) after blocking N-type channels with ω-CTx-GVIA. This leads to:

| (2) |

After blocking N-type and P/Q-type channels with ω-CTx-MVIIC, DCG-IV suppressed pre[Ca2+]t by 16·3 % of control (44·1 % - 27·8 %). Therefore we have:

| (3) |

Solving eqns (1) to (3), we obtained α= 0·365, β= 0·737 and γ= 0·370. Thus, it was calculated that 1 μM DCG-IV inhibited N-, P/Q- and non-LNPQ-types by 36·5 %, 73·7 % and 37·0 %, respectively (Fig. 7B, ▪). The differential inhibition of pharmacologically distinct Ca2+ channel components suggests that DCG-IV-induced suppression of pre[Ca2+]t is not due to modulation of the action potential waveform by activation of K+ channels (Cochilla & Alford, 1998), but rather to specific metabotropic inhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ channels (Swartz & Bean, 1992; Ikeda et al. 1995).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated mechanisms underlying the presynaptic inhibitory action at the hippocampal mossy fibre synapse by group II mGluRs selectively expressed on the axonal membrane (Yokoi et al. 1996; Shigemoto et al. 1997). Combining a quantitative fluorescence measurement of Ca2+ in the presynaptic terminals with simultaneous recording of field EPSPs, we have demonstrated that at least two distinct mechanisms, i.e. reduction of the presynaptic Ca2+ influx and downregulation of the subsequent release machinery, are involved. Furthermore, differential inhibition of multiple subtypes of presynaptic Ca2+ channels by mGluR activation has been demonstrated pharmacologically using toxins which interact specifically with distinct Ca2+ channel subtypes.

Unique axonal localization of presynaptic mGluR2 at the mossy fibre-CA3 synapse raises the question of how such extrasynaptic receptors regulate transmitter release at ‘distant’ active zones. Previous studies have suggested that inhibition of release machinery might be involved, at least in part. The relatively non-specific mGluR agonist trans-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (t-ACPD) reversibly suppressed the frequency of mEPSCs recorded from CA3 pyramidal cells in slice cultures, without affecting their amplitude (Scanziani et al. 1995). DCG-IV also suppressed the frequency of mIPSCs without affecting their amplitudes in the accessory olfactory bulb (Hayashi et al. 1993) as well as in the cerebellum (Llano & Marty, 1995) and the hippocampal CA3 region (Poncer et al. 1995). Our results (Fig. 6) support the idea that activation of mGluR2 inhibits the transmitter release machinery downstream of Ca2+ entry. Although we could not determine the origin of the observed mEPSCs (i.e. mossy fibre terminals vs. other inputs), it seems likely that the reduction in the frequency of mEPSCs resulted mainly from the reduction in spontaneous transmitter release from mossy fibre terminals, since DCG-IV selectively suppresses mossy fibre-evoked EPSPs without affecting other excitatory inputs to CA3 neurones (e.g. commissural/associational inputs and CA3 recurrent collaterals; Kamiya et al. 1996). The relative degree of reduction in frequency of mEPSCs may be somewhat underestimated given that these remaining mEPSCs are not originated from mossy fibre terminals.

On the other hand, there are several indications that mGluR2 activation leads to inhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ channels. Experiments in a neuronal heterologous expression system (Ikeda et al. 1995) have shown that mGluR2 activation specifically inhibits N-type Ca2+ channels. N-type Ca2+ channels in dissociated CA3 pyramidal neurones were also inhibited by the mGluR agonist ACPD (Swartz & Bean, 1992). In line with these results, the present study clearly demonstrated that the presynaptic Ca2+ channels are potently and specifically regulated by activation of presynaptic mGluR2.

Using subtype-specific toxins, we have demonstrated that multiple Ca2+ channel subtypes are involved in the presynaptic Ca2+ transients at the mossy fibre terminals. Previous studies have also suggested that multiple Ca2+ channel subtypes are involved in transmitter release from the mossy fibre terminals (Kamiya et al. 1988; Castillo et al. 1994; Yamamoto et al. 1994), on the basis of measurement of EPSP or EPSC. Therefore, it is tempting to make a comparison between the contribution of different Ca2+ channel subtypes to the EPSC/EPSP reported in the previous studies and that to presynaptic Ca2+ transients defined in this study. However, this comparison would not be very informative, as multiple presynaptic Ca2+ channel subtypes have been shown to couple differentially to transmitter release at both cerebellar (Mintz et al. 1995) and MNTB synapses (Wu et al. 1999).

The limitation of the fluorescence recording adopted in this study was the deterioration of the Ca2+ signals over the recording period (up to 50 min). The ΔF/F values ran down to 80-90 % of control after 50 min of recording without drug application (data not shown). To evaluate how this run-down affects our conclusions, we have re-estimated the extent of inhibition by DCG-IV or Ca2+ channel blockers under the assumption that the ΔF/F value would recover to the baseline after washout of DCG-IV. Although the extent of inhibition was decreased slightly by this correction, we still reached the same conclusions in Figs 4, 5 and 7. For example, DCG-IV at 1 μM was re-estimated to suppress ΔF/F to 59·2 % of control, whereas it was suppressed to 55·2 % of control values before this correction in Fig. 4. This small reduction in the extent of inhibition by DCG-IV did not affect the conclusion in Fig. 5 that the suppression of field EPSPs was greater than would be expected if the suppression were due solely to a decrease in the presynaptic Ca2+ influx. The differential inhibition of pharmacologically distinct Ca2+ channel components by DCG-IV shown in Fig. 7 was also tenable. The involvement of N, P/Q and non-LNPQ types was re-estimated to be 24·2, 21·7 and 54·1 % (before correction, 34·2, 21·7 and 44·1 %), respectively, and DCG-IV inhibited N-, P/Q- and non-LNPQ-type channels by 37·2, 73·7 and 26·4 % (before correction, by 36·5, 73·7 and 37·0 %), respectively. Thus, the P/Q type was most strongly inhibited by DCG-IV even after this correction.

What kind of intracellular messenger transmits the signal from extrasynaptic mGluR2 to distant active zones? Previous studies suggest that a reduction in cAMP concentration within mossy fibre terminals might be involved in the presynaptic inhibitory action of DCG-IV. Firstly, cloned mGluR2 expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells was shown to be negatively coupled to forskolin-stimulated cAMP formation (Hayashi et al. 1993). Secondly, forskolin application enhanced mossy fibre transmission by presynaptic mechanisms (Weisskopf et al. 1994) and thirdly, DCG-IV-induced suppression was reduced markedly during forskolin-induced enhancement (Kamiya & Yamamoto, 1997; Maccaferri et al. 1998). These results suggest the possible involvement of cAMP-dependent mechanisms in the effects of DCG-IV. In line with this hypothesis, cAMP is proposed to act as a ‘long-distance’ diffusible messenger in polarized cells, such as pancreatic exocrine cells, as well as in neuronal cells (Kasai & Petersen, 1994). On the other hand, transmission between mossy fibre terminals and interneurones within the stratum lucidum was not potentiated by the application of forskolin, while DCG-IV also suppressed the transmission (Maccaferri et al. 1998). Therefore, it has been suggested that DCG-IV effect at this synapse does not involve cAMP-dependent pathways but requires an alternative signal. Thus, the issue of the intracellular messenger that transmits the signal from the extrasynaptic mGluR2 remains to be elucidated.

This study has demonstrated that the mechanisms responsible for group II mGluR-mediated presynaptic modulation at hippocampal mossy fibre synapses are different from those involved in group III-mediated effects in the calyx synapse of the MNTB (Takahashi et al. 1996). Contrasting localization of group II and III mGluRs (extrasynaptic vs. synaptic; Shigemoto et al. 1997) also suggests that these presynaptic receptors play different roles in regulating excitatory transmission. Extrasynaptic localization of group II mGluRs at mossy fibre-CA3 synapses might be favourable to frequency-dependent activation of these presynaptic receptors. In fact, it has been demonstrated that mGluR2 autoreceptors at this synapse are not activated during low-frequency activity, but become activated when the glutamate concentration is increased by higher-frequency activity or by blocking glutamate uptake (Scanziani et al. 1997). The diversity of presynaptic autoreceptors at glutamatergic synapses may make it possible to regulate specifically the efficacy of synaptic transmission depending on neural activities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CREST (Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology) of the Japan Science and Technology Corporation (JST) and by Grants-in-Aid No. 10156207 for Scientific Research on Priority areas on ‘Functional Development of Neural Circuits’ and Nos 09780761 and 10169208 from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

References

- Baskys A, Malenka RC. Agonists at metabotropic glutamate receptors presynaptically inhibit EPSCs in neonatal rat hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;444:687–701. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo PE, Weisskopf MG, Nicoll RA. The role of Ca2+ channels in hippocampal mossy fiber synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1994;12:261–269. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claiborne BJ, Amaral DG, Cowan WM. A light and electron microscopic analysis of the mossy fibres of the rat dentate gyrus. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1986;246:435–458. doi: 10.1002/cne.902460403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochilla AJ, Alford S. Metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated control of neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80481-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Regehr WG. Contributions of calcium-dependent and calcium-independent mechanisms to presynaptic inhibition at cerebellar synapse. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;16:1623–1633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01623.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge FA, Rahamimoff R. Co-operative action of calcium ions in transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. The Journal of Physiology. 1967;193:419–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulyás AI, Miettinen R, Jacobowitz DM, Freund TF. Calretinin is present in non-pyramidal cells of the rat hippocampus. I. A new type of neuron specifically associated with the mossy fibre system. Neuroscience. 1992;48:1–27. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Momiyama A, Takahashi T, Ohishi H, Ogawa-Meguro R, Shigemoto R, Mizuno N, Nakanishi S. Role of a metabotropic glutamate receptor in synaptic modulation in the accessory olfactory bulb. Nature. 1993;366:687–690. doi: 10.1038/366687a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda SR, Lovinger DM, McCool BA, Lewis DL. Heterologous expression of metabotropic glutamate receptors in adult rat sympathetic neurons: subtype-specific coupling to ion channels. Neuron. 1995;14:1029–1038. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas P, Major J, Sakmann B. Quantal components of unitary EPSCs at the mossy fibre synapse on CA3 pyramidal cells of rat hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;472:615–663. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Ozawa S. Kainate receptor-mediated inhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ influx and field EPSP in area CA1 of the rat hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 1998a;509:833–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.833bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Ozawa S. Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated suppression of presynaptic calcium influx at mossy fibre-CA3 synapse. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1998b;24:822. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Sawada S, Yamamoto C. Synthetic ω-conotoxin blocks synaptic transmission in the hippocampus in vitro. Neuroscience Letters. 1988;91:84–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Shinozaki H, Yamamoto C. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor type 2/3 suppresses transmission at rat hippocampal mossy fibre synapses. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;493:447–455. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Yamamoto C. Phorbol ester and forskolin suppress the presynaptic inhibitory action of group-II metabotropic glutamate receptor at rat hippocampal mossy fibre synapse. Neuroscience. 1997;80:89–94. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai H, Petersen OH. Spatial dynamics of second messengers: IP3 and cAMP as long range and associative messengers. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landò L, Zucker RS. Ca2+ cooperativity in neurosecretion measured using photolabile Ca2+ chelators. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72:825–830. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.2.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano I, Marty A. Presynaptic metabotropic glutamatergic regulation of inhibitory synapses in rat cerebellar slices. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:163–176. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, Tóth K, McBain CJ. Target-specific expression of presynaptic mossy fibre plasticity. Science. 1998;279:1368–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5355.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe T, Renner P, Nicoll RA. Postsynaptic contribution to long-term potentiation revealed by the analysis of miniature synaptic currents. Nature. 1992;355:50–55. doi: 10.1038/355050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minta A, Kao JPY, Tsien RY. Fluorescent indicators for cytosolic calcium based on rhodamine and fluorescein chromophores. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:8171–8178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Calcium control of transmitter release at a cerebellar synapse. Neuron. 1995;15:675–688. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poncer J-C, Shinozaki H, Miles R. Dual modulation of synaptic inhibition by distinct metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;485:121–134. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regehr WG, Tank DW. Selective fura-2 loading of presynaptic terminals and nerve cell processes by local perfusion in mammalian brain slice. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1991;37:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90121-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Presynaptic inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission by muscarinic and metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in the hippocampus: are Ca2+ channels involved. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1549–1557. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00119-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Salin PA, Vogt KE, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Use-dependent increases in glutamate concentration activate presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature. 1997;385:630–634. doi: 10.1038/385630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R, Kinoshita A, Wada E, Nomura S, Ohishi H, Takada M, Flor PJ, Neki A, Abe T, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Differential presynaptic localization of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in the rat hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:7503–7522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz KJ, Bean BP. Inhibition of calcium channels in rat CA3 pyramidal neurons by a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:4358–4371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04358.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Onodera K. Presynaptic calcium current modulation by a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Science. 1996;274:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Momiyama A. Different types of calcium channels mediate central synaptic transmission. Nature. 1993;366:156–158. doi: 10.1038/366156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth K, McBain CJ. Afferent-specific innervation of two distinct AMPA receptor subtypes on single hippocampal interneurons. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:572–578. doi: 10.1038/2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzounopoulos R, Janz R, Südhof TC, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. A role for cAMP in long-term depression at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Neuron. 1998;21:837–845. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80599-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Castillo PE, Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. Mediation of hippocampal mossy fibre long-term potentiation by cyclic AMP. Science. 1994;265:1878–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.7916482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DB, Randall A, Tsien RW. Roles of N-type and Q-type Ca2+ channels in supporting hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science. 1994;264:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.7832825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-G, Saggau P. Adenosine inhibits evoked synaptic transmission primarily by reducing presynaptic calcium influx in area CA1 of hippocampus. Neuron. 1994;12:1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-G, Saggau P. Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-G, Westenbroek RE, Borst JG, Catterall WA, Sakmann B. Calcium channel types with distinct presynaptic localization couple differentially to transmitter release in single calyx-type synapses. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:726–736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00726.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto C, Sawada S, Ohno-Shosaku T. Suppression of hippocampal synaptic transmission by the spider toxin ω-agatoxin-IV-A. Brain Research. 1994;634:349–352. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91942-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi M, Kobayashi K, Manabe T, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi I, Katsuura G, Shigemoto R, Ohishi H, Nomura S, Nakamura K, Nakao K, Katsuki M, Nakanishi S. Impairment of hippocampal mossy fibre LTD in mice lacking mGluR2. Science. 1996;273:645–647. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino M, Kamiya H. Suppression of presynaptic calcium influx by metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists in neonatal rat hippocampus. Brain Research. 1995;695:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00743-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T-P, Brown TH. Three-dimensional quantification of mossy-fibre presynaptic boutons in living hippocampal slices using confocal microscopy. Synapse. 1994;18:190–197. doi: 10.1002/syn.890180304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]