Abstract

The actions of opioid receptor agonists on synaptic transmission in substantia gelatinosa (SG) neurones in adult (6- to 10-week-old) rat spinal cord slices were examined by use of the blind whole-cell patch-clamp technique.

Both the μ-receptor agonist DAMGO (1 μM) and the δ-receptor agonist DPDPE (1 μM) reduced the amplitude of glutamatergic excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) which were monosynaptically evoked by stimulating Aδ afferent fibres. Both also decreased the frequency of miniature EPSCs without affecting their amplitude.

In contrast, the κ-receptor agonist U-69593 (1 μM) had little effect on the evoked and miniature EPSCs.

The effects of DAMGO and DPDPE were not seen in the presence of the μ-receptor antagonist CTAP (1 μM) and the δ-receptor antagonist naltrindole (1 μM), respectively.

Neither DAMGO nor DPDPE at 1 μM affected the responses of SG neurones to bath-applied AMPA (10 μM).

Evoked and miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs), mediated by either the GABAA or the glycine receptor, were unaffected by the μ-, δ- and κ-receptor agonists. Similar results were also obtained in SG neurones in young adult (3- to 4-week-old) rat spinal cord slices.

These results indicate that opioids suppress excitatory but not inhibitory synaptic transmission, possibly through the activation of μ- and δ- but not κ-receptors in adult rat spinal cord SG neurones; these actions are presynaptic in origin. Such an action of opioids may be a possible mechanism for the antinociception produced by their intrathecal administration.

The dorsal horn of the spinal cord is thought to be an important site for the analgesic action of opioid receptor agonists. A powerful analgesia is produced following intrathecal administration of opioids in rats (Yaksh & Rudy, 1976) and in humans (Onofrio & Yaksh, 1990; see Cousins & Mather, 1984, for review); this analgesic effect may be mediated by three principal subtypes of opioid receptors, μ-, δ- and κ-type. Agonists of the opioid receptors are known to modulate synaptic transmission through both pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms in the central nervous system (CNS). It has been reported that μ- and δ-opioid receptor agonists inhibit glutamatergic synaptic transmission in CNS neurones presynaptically (superficial spinal dorsal horn: Jeftinija, 1988; Hori et al. 1992; Glaum et al. 1994; spinal trigeminal nucleus: Grudt & Williams, 1994; midbrain periaqueductal grey (PAG): Vaughan & Christie, 1997). Alternatively, opioids may open one or more K+ channels through the activation of each of μ-, δ- and κ-opioid receptors and thus hyperpolarize membranes, resulting in an inhibition of excitatory transmission in CNS neurones including rat spinal cord (Yoshimura & North, 1983; Jeftinija, 1988) and spinal trigeminal nucleus neurones (Grudt & Williams, 1993, 1994; see North, 1993, for review). Such pre- and postsynaptic actions of opioids in the spinal cord are supported by binding and histochemical studies. These opioid receptors have been found in superficial layers of the spinal cord, especially Rexed's lamina II (Rexed, 1952; substantia gelatinosa, SG) in rats (Besse et al. 1990; Gouarderes et al. 1991; see Mansour et al. 1995, for review) and in humans (Faull & Villiger, 1987). A reduction by 40-70% in the number of opioid-binding sites has been observed in the dorsal horn after either dorsal rhizotomy (Ninkovic et al. 1981; Besse et al. 1990; Gouarderes et al. 1991) or injection of a selective fine-afferent neurotoxin, capsaicin (Gamse et al. 1979), where the loss of binding sites paralleled the disappearance of fine primary afferent fibres, indicating the localization of opioid receptors to both nerve terminals and postsynaptic neurones (see Coggeshall & Carlton, 1997, for review). It has also been demonstrated that the rat SG contains endogenous opioid peptides such as the enkephalins (Hunt et al. 1980; Merchenthaler et al. 1986).

SG neurones preferentially receive thin myelinated Aδ and unmyelinated C primary afferent fibres, both of which carry nociceptive information. The SG neurones are thus thought to play an important role in modulating nociceptive transmission (Kumazawa & Perl, 1978; Yoshimura & Jessell, 1989). It is possible that an opioid-induced inhibition of pain transmission is due to a modulation of glutamatergic transmission at either presynaptic sites of primary afferent fibres or postsynaptic neurones in the SG. This idea is supported by an observation that opioids administered into the SG in anaesthetized cats inhibited the excitation of deeper dorsal horn neurones caused by noxious peripheral stimuli without a change in the response of the neurones to innocuous stimuli such as touch (Duggan et al. 1977).

The inhibitory neurotransmitters glycine and GABA, as well as L-glutamate may be involved in nociceptive transmission in SG neurones. Applying glycine and GABAA receptor antagonists often leads to a bursting activity of excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) in SG neurones in response to a single stimulus which previously evoked only a single EPSP, suggesting that a normally inhibitory circuitry in the SG may prevent a recurrent excitation (Grudt & Williams, 1994; Yoshimura & Nishi, 1995). Actions of opioids on inhibitory transmission may contribute to their antinociceptive effects together with their actions on excitatory transmission. Actions of opioids on inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs), however, have not yet been examined in the SG in the spinal cord. In a previous study, it was demonstrated that opioids hyperpolarize membranes resulting in an inhibition of excitation of SG neurones in adult rat spinal cord slices (Yoshimura & North, 1983). The aim of the present study was to examine the effects of μ-, δ- and κ-opioid receptor agonists (DAMGO, DPDPE and U-69593, respectively) on excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in SG neurones under blockade of the direct postsynaptic action of opioids.

METHODS

Preparation of spinal cord slices

The methods used for obtaining an adult rat spinal cord slice that retained an attached dorsal root and for blind patch-clamp recordings from SG neurones have been described elsewhere (Yoshimura & Nishi, 1993). Briefly, male adult Sprague-Dawley rats (6- to 10-week-old) were anaesthetized with urethane (1.5 g kg−1, i.p.) and then a lumbosacral laminectomy was performed. The lumbosacral spinal cord (L1-S3) was removed and placed in preoxygenated Krebs solution at 1-3°C; the rats were then killed by exsanguination. After cutting all the ventral and dorsal roots near the root entry zone, except for the L4 or L5 dorsal root on one side, the pia-arachnoid membrane was removed. The spinal cord was mounted on a Vibratome and then a 500 μm-thick transverse slice with the dorsal root attached was cut. The slice was placed on a nylon mesh in the recording chamber having a volume of 0.5 ml, and was then perfused at a rate of 15 ml min−1 with Krebs solution which was saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, and maintained at 36 ± 1°C; this perfusion was continued for at least 1 h before recording. The Krebs solution contained (mM): NaCl, 117; KCl, 3.6; CaCl2, 2.5; MgCl2, 1.2; NaH2PO4, 1.2; NaHCO3, 25; and glucose, 11. In some experiments, young adult (3- to 4-week-old) rats were used. All the experimental procedures involving rats were approved by the institutional Animal Use and Care Committee.

Recording and stimulation

SG neurones were identified by their location and morphological features as reported previously (Yoshimura & Jessell, 1989; Yajiri et al. 1997). Under a binocular microscope and with transmitted illumination, the SG was clearly discernible as a relatively translucent band across the dorsal horn. Blind whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from the SG neurones with patch-pipette electrodes having a resistance of 5-12 MΩ (Yoshimura & Nishi, 1993; Yajiri et al. 1997; Baba et al. 1998). The patch-pipette solution contained (mM): caesium sulphate, 110; CaCl2, 0.5; MgCl2, 2; EGTA, 5; Hepes, 5; tetraethylammonium (TEA), 5; ATP (magnesium salt), 5; and guanosine 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphate) (GDP-β-S), 1. The GDP-β-S and K+ channel blockers (Cs+ and TEA) were added to the patch-pipette solution to inhibit a postsynaptic effect of the opioids through the action of GTP-binding proteins (G-proteins) and to block activation of K+ channels which may result from the postsynaptic effect, respectively. Signals were amplified with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). Currents obtained in the voltage-clamp mode were low-pass filtered at 5 kHz, and digitized at 333 kHz with an A/D converter. Data were stored and analysed with a personal computer using pCLAMP 6 and AxoGraph data acquisition program (Axon Instruments). Membrane potentials were not corrected for liquid junction potentials between the Krebs and patch-pipette solutions.

Monosynaptic excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were evoked at a frequency of 0.1 Hz by orthodromic stimulation of the dorsal root (length, 8-12 mm) via a suction electrode. Stimuli of relatively low intensity (duration, 0.1 ms) were used for activating myelinated Aδ fibres, and those having a relatively higher intensity and longer duration (0.4 ms) for unmyelinated C fibres. The stimulus intensity sufficient to activate Aδ and C afferent fibres and the conduction velocity of these fibres were determined from extracellularly recorded compound action potentials from an isolated dorsal root preparation, as described previously (Yoshimura & Jessell, 1989; Yoshimura & Nishi, 1993). The minimal stimulus intensities required to activate Aδ and C afferent fibres were 21 and 78 μA, respectively. The same suction electrode was used to activate dorsal roots in slice preparations throughout the present experiment. Aδ fibre-evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) were judged to be mono- rather than polysynaptic on the basis of both their short and constant latencies and the absence of failures with repetitive stimulation at 20 Hz. Monosynaptic inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) were evoked at a frequency of 0.1 Hz by focal stimulation (duration, 0.1 ms) of interneurones in the SG with a monopolar silver wire electrode (50 μm diameter), insulated except for the tip, located within 150 μm of the recorded neurones. All numerical data are given as means ±s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined as P < 0.01 using either Student's paired t test (unless otherwise noted) or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In all cases n refers to the number of neurones studied.

Application of drugs

Drugs were applied by superfusion, with a change in solution in the recording chamber being complete within 20 s. Drugs used were: [D-Ala2,N-Me-Phe4,Gly5-ol]enkephalin (DAMGO), [D-Pen2,D-Pen5]enkephalin (DPDPE), AMPA, dl-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV), strychnine, bicuculline and GDP-β-S from Sigma; 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) from Tocris Cookson (St Louis, MO, USA); D-(5α,7α,8β)-(+)-N-methyl-N-[7-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-oxaspiro[4.5]dec-8-yl]benzeneacetamide (U-69593) and naltrindole from Research Biochemicals International; D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2 (CTAP) from Bachem (Switzerland); and tetrodotoxin (TTX) from Wako (Osaka, Japan).

RESULTS

Whole-cell recordings were obtained from 204 SG neurones. Stable recordings could be obtained from slices maintained in vitro for more than 12 h, and recordings were made from a single SG neurone for up to 4 h. All SG neurones examined exhibited miniature EPSCs and IPSCs (mEPSCs and mIPSCs, respectively) at a holding potential (VH) of -70 mV and more positive than -60 mV, respectively (see Yoshimura & Nishi, 1993; Baba et al. 1998). Shortly after establishing the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration, opioids elicited an outward current in a subset of SG neurones at -70 mV; this current disappeared within a few minutes under the present conditions where the patch-pipette solution contained GDP-β-S, Cs+ and TEA, suggesting the involvement of G-protein-coupled K+ channels (not shown; see Yoshimura & North, 1983; Yajiri et al. 1997). The following results were obtained after such outward currents had subsided.

Effects of μ-, δ- and κ-receptor agonists on Aδ fibre-evoked EPSCs

In the presence of the GABAA and glycine receptor antagonists bicuculline (20 μm) and strychnine (2 μm), stimulation of a dorsal root with a low stimulus strength (26-66 μA; 1.2-3.1 times the threshold required to elicit an EPSC in the most excitable fibres) evoked a monosynaptic EPSC in SG neurones as shown in Fig. 1B. The evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) had a mean amplitude of 223 ± 16 pA (range, 91-515 pA; n = 52; VH = -70 mV), and the afferent fibres had a conduction velocity of 7.1 m s−1 (3.5-11.7 m s−1), values that concur with those of Aδ fibres. This Aδ fibre eEPSC was completely blocked by CNQX (20 μm), indicating an activation of non-N-methyl-D-aspartate (non-NMDA) receptors (not shown; see Yoshimura & Nishi, 1993).

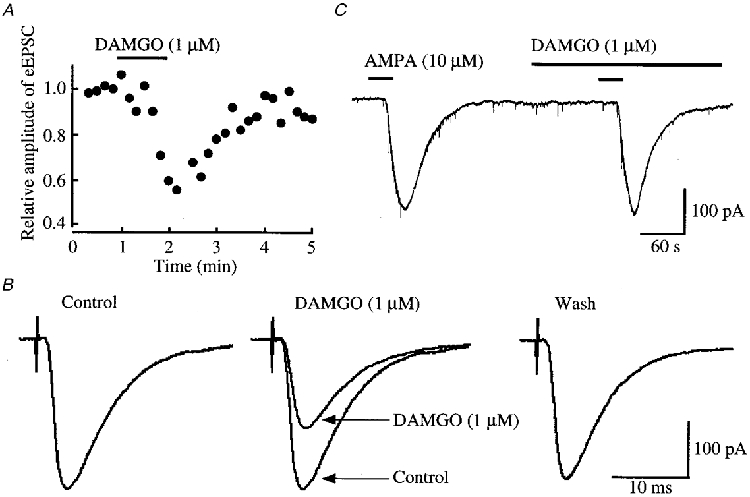

Figure 1. Effects of DAMGO on glutamatergic EPSCs evoked by stimulating Aδ afferent fibres and on the response of SG neurones to AMPA.

A, time course of the amplitude of eEPSCs under the action of DAMGO (1 μM) relative to that before its application; there was a time delay of 1 min before the DAMGO action was maximal. The EPSCs were evoked every 10 s in the presence of bicuculline (20 μm) and strychnine (2 μm). B, averaged traces of six consecutive eEPSCs before (left, Control) and during the action of DAMGO (middle; the control eEPSC is superimposed for comparison), and after washout of the agonist (right). C, AMPA (10 μM) responses in control and during superfusion of DAMGO. In this and following figures, the horizontal bars above the records indicate the period of time during which the drugs were applied; there was a time delay of approximately 20 s before the drug reached SG neurones. Data in A, B and C were obtained from the same neurone; holding potential (VH) = -70 mV.

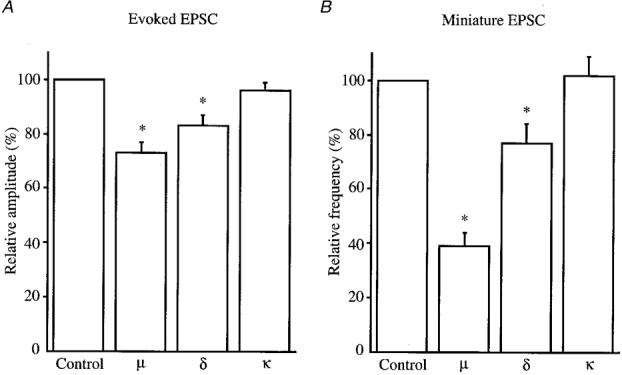

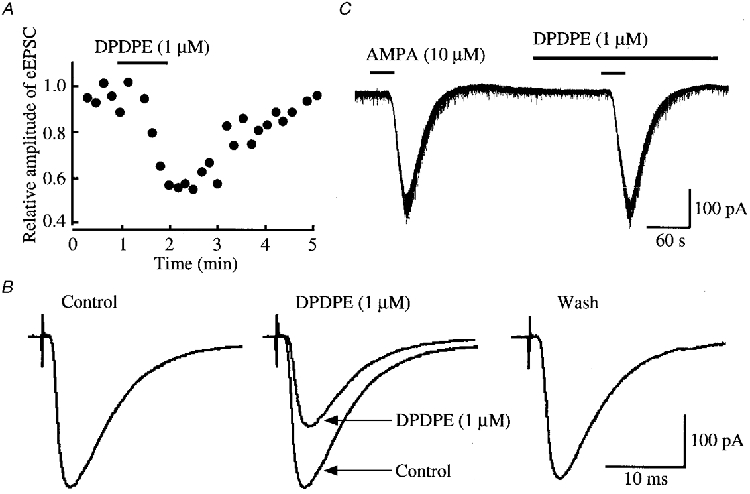

Superfusion of a μ-receptor agonist, DAMGO (1 μm), reversibly reduced the peak amplitude of the glutamatergic Aδ fibre eEPSCs, as shown in Fig. 1A and B. The magnitude of this depression was on average 27 ± 4% (P < 0.01, n = 19; Fig. 5A). The Aδ agonist DPDPE (1 μm) also decreased the amplitude of eEPSCs (Fig. 2A and B) by a mean of 17 ± 4% (P < 0.01, n = 17; Fig. 5A). When examined in neurones exhibiting an inhibition of more than 5%, the effects of DAMGO and DPDPE were not seen in the presence of a μ-receptor antagonist, CTAP (1 μm; 97 ± 3% of control, n = 3), and a δ-receptor antagonist, naltrindole (1 μm; 95 ± 4% of control, n = 3), respectively. In contrast, a κ-receptor agonist, U-69593 (1 μm), had little effect on the eEPSC (amplitude, 96 ± 3% of control; n = 16, P > 0.05; Fig. 5A). In order to determine whether the reduction in eEPSC amplitude by μ- or δ-receptor agonists was pre- or postsynaptic in origin, the effects of these opioid agonists on the response of SG neurones to AMPA (10 μm) were examined. As seen in Figs 1C and 2C, neither DAMGO (1 μm) nor DPDPE (1 μm) affected the peak amplitude of the AMPA response (97 ± 2% (n = 5) and 98 ± 6% (n = 5) of control, respectively; P > 0.05), indicating that these actions were presynaptic.

Figure 5. Effects of DAMGO, DPDPE and U-69593 on glutamatergic eEPSCs and mEPSCs.

Amplitude of eEPSCs (A) and frequency of mEPSCs (B) under the action of DAMGO, DPDPE or U-69593 (μ-, δ- and κ-opioid receptor agonists, respectively; each 1 μm) relative to those in the control. Error bars show s.e.m.; * Significantly different from control, P < 0.01.

Figure 2. Effects of DPDPE on glutamatergic EPSCs evoked by stimulating Aδ afferent fibres and on the response of SG neurones to AMPA.

A, time course of the amplitude of eEPSC under the action of DPDPE (1 μM) relative to that before its application; there was a time delay of 1 min before the DPDPE action was maximal. The EPSCs were evoked every 10 s in the presence of bicuculline (20 μm) and strychnine (2 μm). B, averaged traces of six consecutive eEPSCs before (left, Control) and during the action of DPDPE (middle; control eEPSC is superimposed for comparison), and after washout of the agonist (right). C, AMPA (10 μM) responses in control and during superfusion of DPDPE. Data in A, B and C were obtained from the same neurone; VH = -70 mV.

Although the SG neurones are known to receive C as well as Aδ afferent fibres, the activation of C fibres elicited EPSCs which exhibited failures with repetitive stimulation at 20 Hz, and were therefore presumably polysynaptic in origin; a monosynaptic EPSC was detected only in a few SG neurones. Thus, the effect of opioids on the C afferent responses was not tested.

Effects of μ-, δ- and κ-receptor agonists on mEPSCs

mEPSCs were isolated by adding TTX (0.5 μm) together with bicuculline (20 μm) and strychnine (2 μm) to the superfusing Krebs solution. The mEPSCs occurred at a frequency of 9.0 ± 0.8 Hz (2.1-23.6 Hz, n = 35) with an amplitude of 15.1 ± 0.7 pA (10.1-18.7 pA; VH = -70 mV); these were abolished by the addition of CNQX (20 μm), indicating an involvement of non-NMDA receptors (not shown; see Yoshimura & Nishi, 1993).

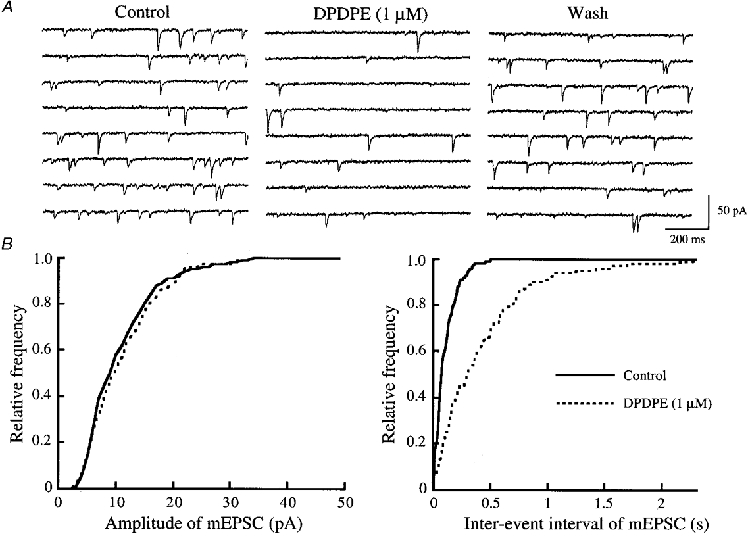

As illustrated in Fig. 3A, superfusion of DAMGO (1 μm) resulted in a rapid and reversible reduction in the frequency of glutamatergic mEPSCs. Figure 3B demonstrates the action of DAMGO on cumulative distributions of the amplitude and inter-event interval of mEPSCs. While DAMGO increased a proportion of mEPSCs having a longer inter-event interval, it had no consistent effect on the cumulative distribution of mEPSC amplitude. The frequency of mEPSCs was on average reduced to 39 ± 5% of control during the action of DAMGO (P < 0.01, n = 17; Fig. 5B), whereas the amplitude was not altered (96 ± 3% of control, P > 0.05). As seen in Fig. 4, DPDPE (1 μm) exhibited a similar action; the frequency of mEPSCs was reduced without a change in the amplitude. On average, the frequency of mEPSCs was reduced to 77 ± 7% of control during the action of DPDPE (P < 0.01, n = 12; Fig. 5B), and the amplitude was 106 ± 5% of control (P > 0.05). The effects of DAMGO and DPDPE were not seen in the presence of CTAP (1 μm; n = 3) and naltrindole (1 μm; n = 3), respectively, although the results were not quantitatively analysed. In contrast, U-69593 (1 μm) had little effect on the frequency of mEPSCs (102 ± 7% of control, n = 6, P > 0.05; Fig. 5B).

Figure 3. Effect of DAMGO on glutamatergic mEPSCs.

A, eight consecutive traces of mEPSCs before (left) and during the action of DAMGO (1 μM) (middle; 1 min after the beginning of DAMGO application), and after washout of the agonist (right); the traces were recorded in the presence of TTX (0.5 μm), bicuculline (20 μm) and strychnine (2 μm). B, cumulative distributions of the amplitude (left) and inter-event interval (right) of mEPSCs, before (continuous line) and during (interrupted line) the action of DAMGO, which were obtained by analysing 399 and 144 mEPSC events, respectively (which occurred over 60 and 120 s, respectively). DAMGO had no effect on the amplitude distribution (P > 0.5), but shifted the frequency distribution towards a longer inter-event interval (P < 0.01; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Data in A and B were obtained from the same neurone; VH = -70 mV.

Figure 4. Effect of DPDPE on glutamatergic mEPSCs.

A, eight consecutive traces of mEPSCs before (left) and during the action of DPDPE (1 μm) (middle; 1 min after the beginning of DPDPE application), and after washout of the agonist (right); the traces were recorded in the presence of TTX (0.5 μm), bicuculline (20 μm) and strychnine (2 μm). B, cumulative distributions of the amplitude (left) and inter-event interval (right) of mEPSCs, before (continuous line) and during (interrupted line) the action of DPDPE, which were obtained by analysing 243 and 156 mEPSC events, respectively (which occurred over 60 and 120 s, respectively). DPDPE had no effect on the amplitude distribution (P > 0.7), but shifted the frequency distribution towards a longer inter-event interval (P < 0.01; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Data in A and B were obtained from the same neurone; VH = -70 mV.

Table 1 demonstrates the proportion of neurones that exhibited magnitudes of inhibition by DAMGO, DPDPE or U-69593 greater than 5% with respect to eEPSC amplitude and mEPSC frequency. A significant inhibition by DAMGO of either eEPSCs or mEPSCs was observed in > 95% of neurones examined, and that by DPDPE was observed in more than 71% of neurones. In contrast, such depressive actions by U-69593 were seen in less than 33% of neurones tested.

Table 1.

Proportion of neurones exhibiting inhibition by μ-, δ- or κ-receptor agonists with respect to either the amplitude of the eEPSC or the frequency of the mEPSC

| DAMGO(μ-type) | DPDPE (δ-type) | U-69593(κ-type) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude of eEPSC | 18/19 (95%) | 12/17 (71%) | 5/16 (31%) |

| Frequency of mEPSC | 17/17 (100%) | 9/12 (75%) | 2/6 (33%) |

The evoked and miniature EPSCs were glutamatergic. The concentration of DAMGO, DPDPE and U-69593 used was 1 μm. The neurones examined were considered to be sensitive to the opioid agonist if they exhibited depressions of more than 5%.

Effects of μ-, δ- and κ-receptor agonists on evoked IPSCs

After blockade of glutamatergic transmission by adding not only CNQX (20 μm) but also an NMDA receptor antagonist, APV (50 μm), to the Krebs solution, local stimulation of interneurones in the SG induced monosynaptic IPSCs in SG neurones voltage clamped at 0 mV. The mean intensity of the stimuli required to activate the interneurones was 79 ± 14 μA. The evoked IPSCs (eIPSCs) consisted of two components which were distinct in their duration and pharmacology: a short eIPSC, which had a half-decay time of 6.5 ± 0.4 ms, and was abolished by strychnine (2 μm); and a long eIPSC, which had a half-decay time of 19.3 ± 3.4 ms, and was depressed by bicuculline (10 μm), indicating that they are mediated by glycine and GABAA receptors, respectively (see Fig. 6A and D; Yoshimura & Nishi, 1993).

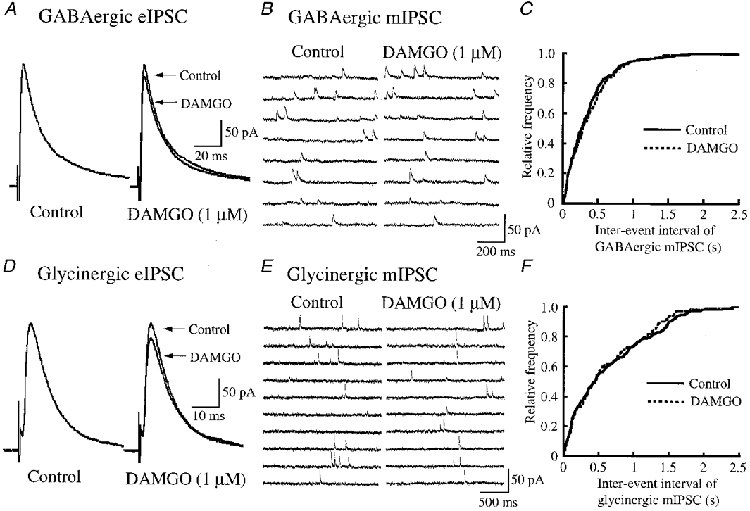

Figure 6. Effects of DAMGO on eIPSCs and mIPSCs that are either GABAergic or glycinergic.

A, averaged traces of six consecutive GABAergic eIPSCs before (left, Control) and during (right; 1 min after the start of DAMGO application; control eIPSC is superimposed for comparison) the application of DAMGO (1 μm). B, eight consecutive traces of GABAergic mIPSCs before (left) and during (right; after 1 min) the application of DAMGO. C, cumulative distributions of the inter-event interval of GABAergic mIPSCs before (continuous line) and during (interrupted line; after 1 min) the application of DAMGO, which were obtained by analysing 152 and 139 mIPSC events, respectively. DAMGO had no effect on the distribution (P > 0.4; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test); the cumulative distribution of GABAergic mIPSC amplitude was also not changed (not shown). Data in B and C were obtained from the same neurone. D, averaged traces of six consecutive glycinergic eIPSCs before (left, Control) and during (right; after 1 min; control eIPSC is superimposed for comparison) the application of DAMGO. E, ten consecutive traces of glycinergic mIPSCs before (left), and during (right; after 1 min) the application of DAMGO. F, cumulative distributions of the inter-event interval of glycinergic mIPSCs before (continuous line) and during (interrupted line; after 1 min) the application of DAMGO, which were obtained by analysing 113 and 110 mIPSC events, respectively. DAMGO had no effect on the distribution (P > 0.5; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test); the cumulative distribution of glycinergic mIPSC amplitude was also not altered (not shown). Data in E and F were obtained from the same neurone. The eIPSCs were evoked every 10 s in the presence of either strychnine (2 μm; A) or bicuculline (20 μm; D) together with CNQX (20 μm) and APV (50 μm); the mIPSCs were recorded in the presence of either strychnine (2 μm; B and C) or bicuculline (20 μm; E and F) together with TTX (0.5 μm), CNQX (20 μm) and APV (50 μm). VH = 0 mV.

GABAergic eIPSCs, recorded in the presence of strychnine (2 μm) together with CNQX (20 μm) and APV (50 μm), had a mean amplitude of 130 ± 11 pA (50-222 pA, n = 25; VH = 0 mV). Superfusion of DAMGO (1 μm) did not affect the peak amplitude of GABAergic eIPSCs (95 ± 4% of control, n = 9, P > 0.05; Fig. 6A). Similarly, neither DPDPE (1 μm) nor U-69593 (1 μm) affected GABAergic eIPSCs (peak amplitude, 101 ± 4% (n = 9) and 98 ± 2% (n = 7) of control, respectively; P > 0.05; not shown). Glycinergic eIPSCs, recorded in the presence of bicuculline (20 μm) together with CNQX (20 μm) and APV (50 μm), had a mean amplitude of 109 ± 12 pA (50-205 pA, n = 21). Superfusion of DAMGO (1 μm) did not affect the peak amplitude of glycinergic eIPSCs (98 ± 2% of control, n = 7, P > 0.05; Fig. 6D). Similarly, neither DPDPE (1 μm) nor U-69593 (1 μm) affected glycinergic eIPSCs (peak amplitude, 100 ± 3% (n = 7) and 97 ± 3% (n = 7) of control, respectively; P > 0.05; not shown).

The failure of DAMGO to affect the eIPSCs contrasts with the results of Grudt & Henderson (1998) who examined the action of DAMGO in spinal trigeminal SG neurones of young adult rats. To examine whether this difference arose because we used mature rats, we repeated our experiments in young adult rat spinal cord slices. DAMGO (1 μm) did not affect the peak amplitudes of GABAergic and glycinergic eIPSCs (98 ± 2% (n = 5) and 96 ± 3% (n = 9) of control, respectively; P > 0.05).

Effects of μ-, δ- and κ-receptor agonists on mIPSCs

mIPSCs were isolated by adding TTX (0.5 μm) together with CNQX (20 μm) and APV (50 μm) to the superfusing solution. There were two types of mIPSC, mediated by either glycine or GABAA receptors, as seen for eIPSCs (Yoshimura & Nishi, 1993).

GABAergic mIPSCs, recorded in the presence of strychnine (2 μm) together with TTX (0.5 μm), CNQX (20 μm) and APV (50 μm), had a frequency of 3.0 ± 0.5 Hz (1.1-6.7 Hz, n = 19) and an amplitude of 13.4 ± 0.9 pA (11.6-15.4 pA; VH = 0 mV). Superfusion of DAMGO (1 μm) did not affect the frequency or amplitude, which were 94 ± 3 and 101 ± 3% of control, respectively (n = 7, P > 0.05; Fig. 6B). Figure 6C demonstrates no effect of DAMGO on a cumulative distribution of the frequency of GABAergic mIPSCs. Similarly, neither DPDPE (1 μm) nor U-69593 (1 μm) changed the frequency of GABAergic mIPSCs (108 ± 6% (n = 6) and 97 ± 4% (n = 6) of control, respectively; P > 0.05; not shown). Glycinergic mIPSCs, recorded by the addition of bicuculline (20 μm) together with TTX (0.5 μm), CNQX (20 μm) and APV (50 μm) to the Krebs solution, had a frequency of 2.3 ± 0.3 Hz (0.6-4.8 Hz, n = 22) and an amplitude of 14.8 ± 1.7 pA (11.8-19.9 pA; VH = 0 mV). Superfusion of DAMGO (1 μm) did not affect the frequency or amplitude, which were 96 ± 5 and 97 ± 4% of control, respectively (n = 8, P > 0.05; Fig. 6E). Figure 6F shows no effect of DAMGO on a cumulative distribution of the frequency of glycinergic mIPSCs. Similarly, neither DPDPE (1 μm) nor U-69593 (1 μm) altered the frequency of glycinergic mIPSCs (101 ± 7% (n = 7) and 102 ± 3% (n = 7) of control, respectively; P > 0.05; not shown).

When examined in SG neurones in young adult rat spinal cord slices, DAMGO (1 μm) did not affect the frequency or amplitude of GABAergic and glycinergic mIPSCs, as seen for eIPSCs, although the results were not quantitatively analysed.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that μ- and δ-opioid receptor agonists (DAMGO and DPDPE, respectively) suppress excitatory but not inhibitory synaptic transmission through a presynaptic action and that the κ-opioid receptor agonist U-69593 has no effect on either type of transmission in adult rat spinal cord SG neurones in slice preparations. A similar depressive action of μ- or δ-opioids on excitatory transmission has been demonstrated in the midbrain PAG (Vaughan & Christie, 1997), the spinal trigeminal SG (Grudt & Williams, 1994) and the superficial layer of the spinal cord in the rat (Jeftinija, 1988; Hori et al. 1992; Glaum et al. 1994).

Inhibition by opioids of excitatory synaptic transmission in SG neurones

Although a similar inhibition of eEPSCs by both DAMGO and DPDPE has been reported in rat spinal cord SG neurones by Glaum et al. (1994), the present work revealed that the opioids depress not only eEPSCs but also mEPSCs. There was a dissociation between the actions of each of the opioids on eEPSC and mEPSC. The magnitude of inhibition by DPDPE was comparable for eEPSCs and mEPSCs. In contrast, the inhibition of eEPSCs by DAMGO was less extensive than that of mEPSCs, as shown in Fig. 5. One reason for this discrepancy may be that opioids act differently on evoked and spontaneous transmitter-release mechanisms, resulting in a distinct action on eEPSCs and mEPSCs; for example, an inhibition of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in nerve terminals leads to a depression of eEPSCs while mEPSCs are unaffected. Alternatively, mEPSCs in SG neurones may be produced by inputs not only from primary afferent fibre axons but also from interneurone axons, the latter terminals having more μ-opioid receptors than the former ones. Although a mechanism for the presynaptic inhibition of eEPSC was not examined here, this would be due to an inhibition of Ca2+ channels by opioids in nerve terminals, because opioids suppress Ca2+ channels in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones (Schroeder et al. 1991; see North, 1993, for review).

When examined at the same concentration (1 μm), the sequence of efficacy of opioids in inhibiting either eEPSCs or mEPSCs was μ- > δ- >> κ-type, as seen in Fig. 5. This rank order was the same as that for the proportion of neurones in which each of the opioids inhibited excitatory transmission by more than 5% (see Table 1). These results are in good agreement with those of the analgesic effect caused by intrathecal injection of opioids in the rat, the potency order of which was μ- > δ- >> κ-type (Dickenson et al. 1987; Leighton et al. 1988; Danzebrink et al. 1995). The different potencies appear to be due to a difference in density among the three types of opioid receptor in the superficial dorsal horn, because it has been demonstrated by radioligand-binding experiments in the rat spinal cord that the most prevalent type of opioid receptor in laminae I-II is the μ-receptor (63% or more) with considerably fewer δ- (23% or less) and κ-type receptors (15% or less) (Besse et al. 1990; Stevens et al. 1991; Rahman et al. 1998).

Previous studies have demonstrated that excitatory afferent transmission is depressed mainly by μ-opioids in superficial dorsal horn neurones of the rat spinal cord (Jeftinija, 1988; Hori et al. 1992). On the other hand, Randic et al. (1995) have reported that κ-receptor agonists cause both potentiation and inhibition of excitatory transmission in spinal cord SG neurones, an observation different from that in the present study. Such a discrepancy among studies may be partly due to a difference in age of the rats used. There is a maturation of the somatosensory pathway during postnatal week 3 in the rat spinal cord; for example, lamina II neurones do not complete their differentiation and maturation processes until 3 weeks of age (Bicknell & Beal, 1984). Alternatively, there is a developmental change during postnatal days 0-56 in the relative proportion of μ-, δ- and κ-receptors in the superficial layers (laminae I-II) in the spinal cord (Rahman et al. 1998). Many of the previous studies have used juvenile rats (Jeftinija, 1988; Hori et al. 1992; Randic et al. 1995: 18- to 30-, 6- to 12- and 15- to 27-day-old, respectively), except for that of Glaum et al. (1994; 28- to 60-day-old) which reported results similar to those in the present study.

Inhibitory synaptic transmission in SG neurones in the spinal cord may not be involved in the antinociceptive action of opioids

A descending antinociceptive modulatory system is known to relay via the PAG and then the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM) to the spinal cord. Vaughan & Christie (1997) have proposed that opioids inhibit GABAergic IPSCs in rat PAG neurones through the activation of μ-receptors and thereby disinhibit PAG output neurones projecting to the RVM, resulting in antinociception. Alternatively, Pan et al. (1990) have demonstrated that GABA-mediated synaptic potentials are reduced by μ-opioids in the primary cells of the nucleus raphe magnus (NRM) in the RVM. If this disinhibition leads to an increase in the activity of NRM neurones which project to the spinal cord, this could be one of the pain modulatory systems in the RVM. In the present study, in rat spinal cord SG neurones, however, opioid receptor agonists did not influence eIPSCs and mIPSCs that were either glycinergic or GABAergic; this was the case in young as well as adult rats. This result is distinct from an observation reported very recently by Grudt & Henderson (1998) that glycinergic and GABAergic transmissions are depressed by DAMGO in SG neurones of the spinal trigeminal nucleus in horizontal brain slices. There are several possibilities which may account for the difference between the spinal cord and spinal trigeminal SG neurones. One possibility is that the transverse slice used in the present study may have severed connections between interneurones which run in a rostro-caudal plane, resulting in no effects of opioids on the inhibitory transmission. Magnuson & Dickenson (1991) have suggested an opioid facilitation involving GABA in rat dorsal horn neurones in horizontal slices. Another possibility is that there is a distinction in opioid actions between SG neurones in the two regions. According to an immunohistochemical study by Mansour et al. (1994), there seems to be a difference in the distribution of μ-, δ- and κ-receptor mRNAs between the rat spinal cord and spinal trigeminal nucleus. Alternatively, it has been reported that there is a distinction in the relative proportion of dynorphin- and enkephalin-immunoreactive neurones between the cat spinal cord and spinal trigeminal nucleus SG (Cruz & Basbaum, 1985). Kemp et al. (1996) have demonstrated that μ-opioid receptors are not expressed in superficial spinal cord dorsal horn interneurones that contain glycine or GABA, although comparable data are not available in the spinal trigeminal nucleus. Since activation of the interneurones via primary afferent fibres is thought to result in glycinergic or GABAergic IPSCs in the spinal cord SG (Yoshimura & Nishi, 1995), the observation of Kemp et al. (1996) may be consistent with the lack of effect of DAMGO on IPSCs revealed in the present study.

Physiological significance of opioid actions in the SG

The dorsal horn of the spinal cord, especially the SG, is a primary receiving area for somatosensory, presumably nociceptive, input, which contains high concentrations of opioid receptors and also of endogenous opioids (see Coggeshall & Carlton, 1997, for review). Low doses of opioids, applied directly to the spinal cord, produce clinically effective and localized analgesia (see Cousins & Mather, 1984; Yaksh, 1993, for reviews). According to the present and previous studies (Yoshimura & North, 1983), this effect appears to be attributed to two actions of opioids: (1) reduction in the release of excitatory neurotransmitters to SG neurones from the central terminals of primary afferent nociceptors, and (2) direct inhibition of SG neurones resulting from membrane hyperpolarization.

In summary, the results presented here provide a cellular basis for the antinociceptive presynaptic action of opioid receptor agonists at the spinal level and support a physiological role for opioids as important inhibitors of sensory information processing in the spinal dorsal horn.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan to M. Y. and E. K., and by the Human Frontier Science Program to M. Y.

References

- Baba H, Kohno T, Okamoto M, Goldstein PA, Shimoji K, Yoshimura M. Muscarinic facilitation of GABA release in substantia gelatinosa of the rat spinal dorsal horn. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:83–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.083br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besse D, Lombard MC, Zajac JM, Roques BP, Besson JM. Pre- and postsynaptic distribution of μ, δ and κ opioid receptors in the superficial layers of the cervical dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. Brain Research. 1990;521:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91519-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicknell HR, Jr, Beal JA. Axonal and dendritic development of substantia gelatinosa neurons in the lumbosacral spinal cord of the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1984;226:508–522. doi: 10.1002/cne.902260406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggeshall RE, Carlton SM. Receptor localization in the mammalian dorsal horn and primary afferent neurons. Brain Research Reviews. 1997;24:28–66. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins MJ, Mather LE. Intrathecal and epidural administration of opioids. Anesthesiology. 1984;61:276–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz L, Basbaum AI. Multiple opioid peptides and the modulation of pain: immunohistochemical analysis of dynorphin and enkephalin in the trigeminal nucleus caudalis and spinal cord of the cat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1985;240:331–348. doi: 10.1002/cne.902400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzebrink RM, Green SA, Gebhart GF. Spinal mu and delta, but not kappa, opioid-receptor agonists attenuate responses to noxious colorectal distension in the rat. Pain. 1995;63:39–47. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00275-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickenson AH, Sullivan AF, Knox R, Zajac JM, Roques BP. Opioid receptor subtypes in the rat spinal cord: electrophysiological studies with μ- and δ-opioid receptor agonists in the control of nociception. Brain Research. 1987;413:36–44. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan AW, Hall JG, Headley PM. Suppression of transmission of nociceptive impulses by morphine: selective effects of morphine administered in the region of the substantia gelatinosa. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1977;61:65–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faull RLM, Villiger JW. Opiate receptors in the human spinal cord: a detailed anatomical study comparing the autoradiographic localization of [3H]diprenorphine binding sites with the laminar pattern of substance P, myelin and nissl staining. Neuroscience. 1987;20:395–407. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamse R, Holzer P, Lembeck F. Indirect evidence for presynaptic location of opiate receptors on chemosensitive primary sensory neurones. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1979;308:281–285. doi: 10.1007/BF00501394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaum SR, Miller RJ, Hammond DL. Inhibitory actions of δ1-, δ2-, and μ-opioid receptor agonists on excitatory transmission in lamina II neurons of adult rat spinal cord. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:4965–4971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04965.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouarderes C, Beaudet A, Zajac J-M, Cros J, Quirion R. High resolution radioautographic localization of [125I]FK-33–824-labelled mu opioid receptors in the spinal cord of normal and deafferented rats. Neuroscience. 1991;43:197–209. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90427-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudt TJ, Henderson G. Glycine and GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in rat substantia gelatinosa: inhibition by μ-opioid and GABAB agonists. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:473–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.473bt.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudt TJ, Williams JT. κ-Opioid receptors also increase potassium conductance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1993;90:11429–11432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudt TJ, Williams JT. μ-Opioid agonists inhibit spinal trigeminal substantia gelatinosa neurons in guinea pig and rat. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:1646–1654. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01646.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori Y, Endo K, Takahashi T. Presynaptic inhibitory action of enkephalin on excitatory transmission in superficial dorsal horn of rat spinal cord. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;450:673–685. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt SP, Kelly JS, Emson PC. The electron microscopic localization of methionine-enkephalin within the superficial layers (I and II) of the spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1980;5:1871–1890. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeftinija S. Enkephalins modulate excitatory synaptic transmission in the superficial dorsal horn by acting at μ-opioid receptor sites. Brain Research. 1988;460:260–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp T, Spike RC, Watt C, Todd AJ. The μ-opioid receptor (MOR1) is mainly restricted to neurons that do not contain GABA or glycine in the superficial dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1996;75:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa T, Perl ER. Excitation of marginal and substantia gelatinosa neurons in the primate spinal cord: indications of their place in dorsal horn functional organization. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1978;177:417–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.901770305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton GE, Rodriguez RE, Hill RG, Hughes J. κ-Opioid agonists produce antinociception after I.V. and i.c.v. but not intrathecal administration in the rat. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1988;93:553–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb10310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson DSK, Dickenson AH. Lamina-specific effects of morphine and naloxone in dorsal horn of rat spinal cord in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1991;66:1941–1950. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.6.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Fox CA, Akil H, Watson SJ. Opioid-receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: anatomical and functional implications. Trends in Neurosciences. 1995;18:22–29. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93946-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Fox CA, Burke S, Meng F, Thompson RC, Akil H, Watson SJ. Mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: an in situ hybridization study. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1994;350:412–438. doi: 10.1002/cne.903500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchenthaler I, Maderdrut JL, Altschuler RA, Petrusz P. Immunocytochemical localization of proenkephalin-derived peptides in the central nervous system of the rat. Neuroscience. 1986;17:325–348. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninkovic M, Hunt SP, Kelly JS. Effect of dorsal rhizotomy on the autoradiographic distribution of opiate and neurotensin receptors and neurotensin-like immunoreactivity within the rat spinal cord. Brain Research. 1981;230:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA. Opioid actions on membrane ion channels. In: Herz A, editor. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 104. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1993. pp. 773–797. [Google Scholar]

- Onofrio BM, Yaksh TL. Long-term pain relief produced by intrathecal morphine infusion in 53 patients. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1990;72:200–209. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.2.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan ZZ, Williams JT, Osborne PB. Opioid actions on single nucleus raphe magnus neurons from rat and guinea-pig in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;427:519–532. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman W, Dashwood MR, Fitzgerald M, Aynsley-Green A, Dickenson AH. Postnatal development of multiple opioid receptors in the spinal cord and development of spinal morphine analgesia. Developmental Brain Research. 1998;108:239–254. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randic M, Cheng G, Kojic L. κ-Opioid receptor agonists modulate excitatory transmission in substantia gelatinosa neurons of the rat spinal cord. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:6809–6826. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06809.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rexed B. The cytoarchitectonic organization of the spinal cord in the cat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1952;96:415–495. doi: 10.1002/cne.900960303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JE, Fischbach PS, Zheng D, McCleskey EW. Activation of μ opioid receptors inhibits transient high- and low-threshold Ca2+ currents, but spares a sustained current. Neuron. 1991;6:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90117-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CW, Lacey CB, Miller KE, Elde RP, Seybold VS. Biochemical characterization and regional quantification of μ, δ and κ opioid binding sites in rat spinal cord. Brain Research. 1991;550:77–85. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90407-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CW, Christie MJ. Presynaptic inhibitory action of opioids on synaptic transmission in the rat periaqueductal grey in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;498:463–472. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yajiri Y, Yoshimura M, Okamoto M, Takahashi H, Higashi H. A novel slow excitatory postsynaptic current in substantia gelatinosa neurons of the rat spinal cord in vitro. Neuroscience. 1997;76:673–688. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL. The spinal actions of opioids. In: Herz A, editor. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 104. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1993. pp. 53–90. [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Rudy TA. Analgesia mediated by a direct spinal action of narcotics. Science. 1976;192:1357–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.1273597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Jessell TM. Primary afferent-evoked synaptic responses and slow potential generation in rat substantia gelatinosa neurons in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1989;62:96–108. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Nishi S. Blind patch-clamp recordings from substantia gelatinosa neurons in adult rat spinal cord slices: pharmacological properties of synaptic currents. Neuroscience. 1993;53:519–526. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Nishi S. Primary afferent-evoked glycine- and GABA-mediated IPSPs in substantia gelatinosa neurones in the rat spinal cord in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;482:29–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, North RA. Substantia gelatinosa neurones hyperpolarized in vitro by enkephalin. Nature. 1983;305:529–530. doi: 10.1038/305529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]