Abstract

A high-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel (BK KCa) was characterized at a cholinergic presynaptic nerve terminal using the calyx synapse isolated from the chick ciliary ganglion.

The channel had a conductance of 210 pS in a 150 mM:150 mM K+ gradient, was highly selective for K+ over Na+, and was sensitive to block by external charybdotoxin or tetraethylammonium (TEA) and by internal Ba2+. At +60 mV it was activated by cytoplasmic calcium [Ca2+]i with a Kd of ≈0.5 μM and a Hill coefficient of ≈2.0. At 10 μM [Ca2+]i the channel was 50 % activated (V½) at -8.0 mV with a voltage dependence (Boltzmann slope-factor) of 32.7 mV. The V½ values hyperpolarized with an increase in [Ca2+]i while the slope factors decreased. There were no overt differences in conductance or [Ca2+]i sensitivity between BK channels from the transmitter release face and the non-release face.

Open and closed times were fitted by two and three exponentials, respectively. The slow time constants were strongly affected by both [Ca2+]i and membrane potential changes.

In cell-attached patch recordings BK channel opening was enhanced by a prepulse permissive for calcium influx through the patch, suggesting that the channel can be activated by calcium ion influx through neighbouring calcium channels.

The properties of the presynaptic BK channel are well suited for rapid activation during the presynaptic depolarization and Ca2+ influx that are associated with transmitter release. This channel may play an important role in terminating release by rapid repolarization of the action potential.

Substantial evidence suggests that most, if not all, nerve terminals that secrete neurotransmitters by action potential-dependent mechanisms exhibit a calcium-activated potassium (KCa) channel. Such terminals include presynaptic nerve terminals at fast-transmitting synapses (Bartschat & Blaustein, 1985; Farley & Rudy, 1988; Anderson et al. 1988; Lindgren & Moore, 1989; Schneider et al. 1989; Astrand & Stjarne, 1991; Sivaramakrishnan et al. 1991; Robitaille & Charlton, 1992; Wangemann & Takeuchi, 1993; Blundon et al. 1995; Rahamimoff et al. 1995; Katz et al. 1997; Sakaba et al. 1997; Yazejian et al. 1997), hormone-secreting nerve terminals (Bielefeldt et al. 1992; Wang & Lemos, 1992; Wang et al. 1992; Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1993) and sense-organ cells (such as hair cells, Edgington & Stewart, 1981; Roberts et al. 1990, 1991; Issa & Hudspeth, 1994; Art et al. 1995) which share many properties with fast-transmitting nerve terminals. It is not clear which specific types of KCa channel are present at most of these sites but, where tested by specific staining or direct recording, the high-conductance, BK-type has been repeatedly observed (Smith et al. 1986; Castle & Strong, 1986; Roberts et al. 1991; Robitaille & Charlton, 1992; Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1993; Wangemann & Takeuchi, 1993; Issa & Hudspeth, 1994; Art et al. 1995; Knaus et al. 1996). Other studies have presented more indirect evidence for the presence of this channel in the nerve terminal on the basis of effects of peptide blockers, primarily charybdotoxin (CTX) or iberiotoxin (IbTX), or intracellular buffers on transmitter release (Kumamoto & Kuba, 1985; Sivaramakrishnan et al. 1991; Robitaille & Charlton, 1992; Stretton et al. 1992; Takeuchi & Wangemann, 1993; Robitaille et al. 1993; Yazejian et al. 1997).

Despite the evident broad distribution of BK channels in nerve terminals little is known about their biophysical properties and to what extent these may differ from their relatives in the cell soma. This question has become of particular interest recently with the discovery that the BK channel can be expressed in many functionally different isoforms (Butler et al. 1993; Wei et al. 1998). In addition, the channel can associate with a β subunit (Vergara et al. 1998) that has marked effects on its biophysical and pharmacological properties. Thus, because of this diversity a full understanding of the role of this channel in the nerve terminal requires direct recording of its properties in situ. Furthermore, the complex activation characteristics of the BK channel require analysis at the single-channel level since it is gated by both a ligand and a physical factor, i.e. calcium and voltage. There have been only two nerve terminals at which the single-channel properties of BK channels have been examined (Wang et al. 1992; Wangemann & Takeuchi, 1993; Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1993) due, presumably, to the general small size and inaccessibility of these structures. Few nerve terminals are of sufficiently large size to permit direct patch-clamp recording, and in the cases where this is possible obtaining sufficient data requires considerable experimental effort. This study presents the first characterization of single BK channels at the presynaptic nerve terminal of a neuron-to-neuron synapse.

We used the calyx-type synapse of the chick ciliary ganglion (CCG) to record and characterize single presynaptic high-conductance KCa channels. This experimental preparation was the first in which an intact vertebrate presynaptic terminal could be voltage clamped to record whole-terminal currents (Stanley, 1989) or clamped in the cell-attached configuration (Stanley, 1991) to record single-channel activity. We have recently presented evidence for the presence of KCa channels on this terminal by direct recording of an outwardly rectifying K+ current that was sensitive to CTX and IbTX (Tozer et al. 1998). In this study we first used the patch-clamp technique in the outside-out and inside-out configurations to test for block with standard K+ channel blockers. We next used the same techniques to examine the voltage and calcium sensitivity of single BK channels. Finally, we used the cell-attached configuration to test whether presynaptic BK channels could be activated by calcium influx through the same membrane patch.

METHODS

Preparation of calyces

Calyx nerve terminals were prepared as described (Stanley, 1991; Stanley & Goping, 1991). Briefly, 15-day-old chick embryos were killed, in compliance with NIH guidelines, by decerebration immediately upon removal from the egg. Ciliary ganglia were dissected and were incubated in modified Eagle's medium (MEM) with 0.74 mg ml−1 collagenase Type IV (Worthington), 12.3 mg ml−1 Dispase (Boehringer Mannheim), 800 units ml−1 hyaluronidase and 70 μg ml−1 trypsin inhibitor Type II (Sigma) for 2-3 h at 37°C in 5 % CO2 and 95 % air. The cells were washed, triturated and allowed to adhere to a glass coverslip in a 0.5 ml chamber for recording. The above treatment resulted in calyx nerve terminals that had been dissociated from the postsynaptic neurones to varying degrees, and included intact, partially dissociated and fully dissociated calyx synapses. Except where specified, only fully isolated calyces (see Haydon et al. 1994, Fig. 1C) were used for single-channel recording in this study.

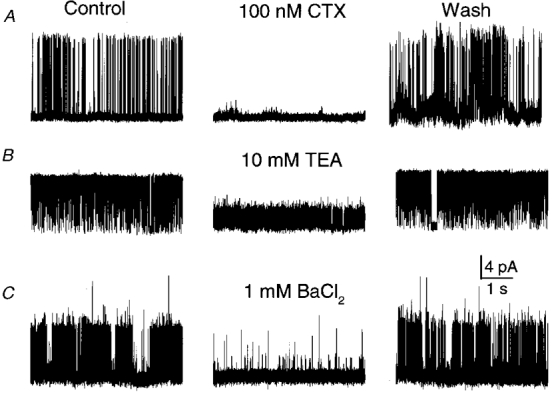

Figure 1. Effect of blockers on single KCa channels in isolated patches.

Block by external CTX (A) or TEA (B), recorded in outside-out patches, or by internal Ba2+ (C), recorded from an inside-out patch, were all reversible. Channel openings are upward. Symmetrical 150 mM K+ was used with 100 μM [Ca2+]i on the cytoplasmic face. Membrane potential: +60 mV in A, +40 mV in B and C.

Single-channel recording

The patch clamp was used in several configurations including cell-attached, outside-out and inside-out. Patch pipettes (WPI, TW150F) were fire polished and coated with beeswax. For cell-attached recording patch electrodes were filled with standard extracellular solution (SES) containing (mM): 140 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 5 KCl, 0.001 TTX and 10 Hepes; pH = 7.3 (adjusted with NaOH). 4-Aminopyridine (4-AP; 10 mM) was added to block calcium-insensitive K+ channels. The bath contained SES in which the NaCl had been replaced with KCl (K+-SES) to depolarize the membrane potential to ∼0 mV. For outside-out recordings the bath contained SES while the pipette was filled with standard internal solution (SIS) containing (mM): 150 KCl or 150 potassium aspartate, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 2 EGTA and 10 Hepes; pH 7.3 (adjusted with KOH). The calculated free internal Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) is 7 μM (see below for method). Inside-out patches were recorded with K+-SES in the pipette and SIS in the bath. Free-calcium levels on the cytoplasmic face of the membrane were set by adding the calculated ratio of CaCl2 and EGTA (using Chelator 1.0 software, Schoenmakers, Nijmen, The Netherlands). Patches were excised initially in low free-calcium of 0.01-0.1 μM. Channels that exhibited detectable inactivation (Fig. 7) were not used in analysis of steady-state open probablity (Po) and kinetics. The dish was continually perfused and drugs and salts were added directly to the perfusate, allowing 15 min for complete solution exchange. Experiments were carried out at room temperature (∼22°C).

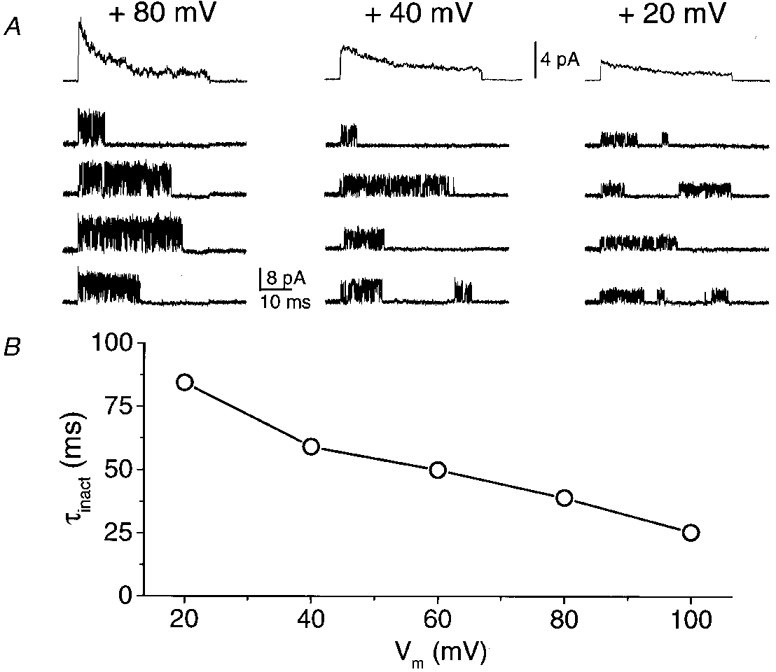

Figure 7. Inactivation of single-channel BK currents.

A, each panel shows recordings of a single KCa channel in an inside-out patch during voltage steps from Vh= -70 mV to the indicated potentials. The bottom four traces are representative recordings whilst the top trace is the ensemble average of 100 traces. This behaviour was only observed in a few patches. B, the decay of each ensemble average was fitted to a single exponential and the time constant (τinact) plotted as a function of the membrane potential. Symmetrical 150 mM K+ solutions were used, with 10 μM [Ca2+]i.

Channel blockers

CTX, tetraethylammonium (TEA), and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) were from RBI.

Data acquisition

Single-channel currents were acquired, filtered at 5 kHz, and sampled at 10-50 kHz with an Axopatch 1C amplifier (Axon Instruments) controlled using pCLAMP (v. 5.5 to 6.03; Axon Instruments) software. Data were stored on disc and were analysed with pCLAMP (v. 6.03) software.

Analysis

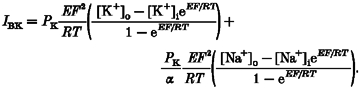

All membrane potentials are presented as the potential inside the cell relative to that outside. The number of channels in the patch was determined by holding the membrane at +60 mV in the presence of a high [Ca2+]i and recording for gt; 30 s. Since the maximum open probability (Po(max)) is high (>s0.7, see Fig. 4) multi-channel patches could be readily identified. All patches used for lifetime distributions contained only one channel and were recorded for a minimum of 30 s under all conditions. Longer durations were used when the open probability was low. The permeability ratio (α=PK/PNa) was calculated using a simplification of the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation for monovalent ions:

| (1) |

where R, T and F have their usual meanings.

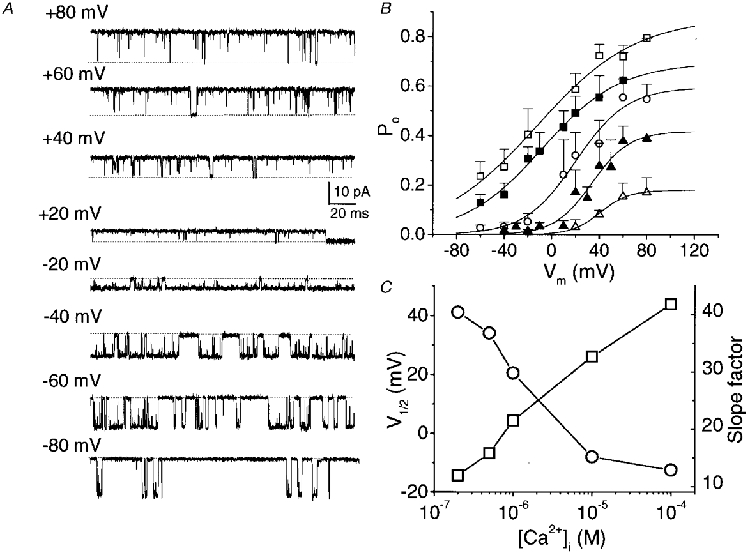

Figure 4. Voltage dependence of BK channels at different [Ca2+]i.

A, BK channel activity recorded at a range of membrane potentials in symmetrical K+ (150 mM) with 100 μM [Ca2+]i. B, Po as a function of membrane potential at various [Ca2+]i (μM): □, 100; ▪, 10; ^, 1; ▴, 0.5; ▵, 0.2. Each point represents the mean of single channels in 3-8 different patches. Smooth curves are fitted with Boltzmann relations which were set to Po(min)→ 0. C, plot of V½ (^) and slope factors (□) derived from the Boltzmann fits to the data in B against [Ca2+]i.

Single-channel current-voltage curves were fitted with the predicted K+ current using the Goldman current equation:

To make this calculation we assumed that K+ and Na+ are the only permeant ions and subtracted the small contribution of Na+ current. That is, the measured current (IBK) =IK+INa:

|

(2) |

Open-closed transitions were detected as current transitions beyond a threshold level set at 50 % of the fully open channel. Although subconductance states were occasionally seen in these channels (see Fig. 2), they were too infrequent to significantly affect the channel-state analysis. Dwell times were binned using a log-scale bin size, plotted on linear bin amplitude co-ordinates and were fitted to multiexponential functions with a Levenberg-Marquardt curve fitting algorithm in the pCLAMP (v. 6.03) analysis suite. The mean open and closed durations were obtained as the sum of the relative area of each exponential component multiplied by the time constant of the component. Data are expressed as means ± s.e.m, with n indicating the number of recordings.

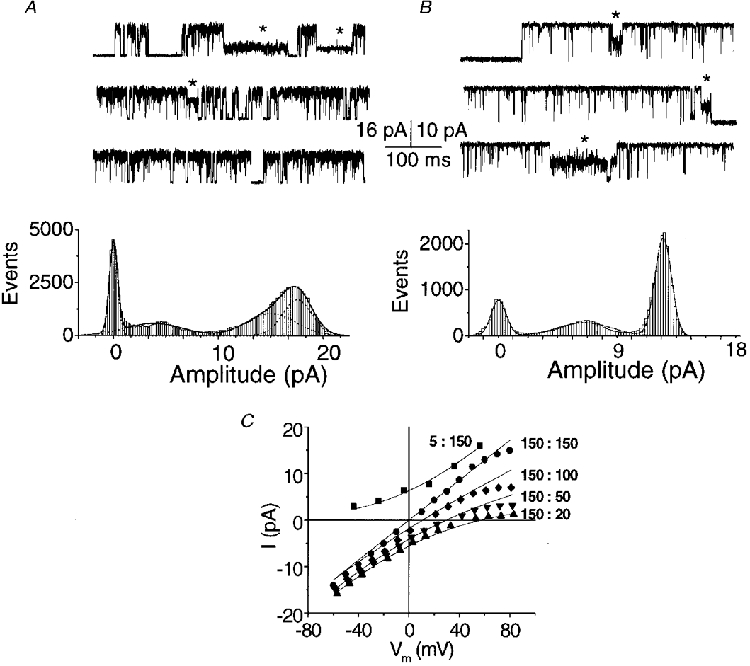

Figure 2. Single-channel KCa currents, subconductance states and cation selectivity.

A and B, two examples of current fluctuations (upper panels) and all-points histograms with fitted Gaussian distributions (lower panels) in inside-out membrane patches held at +60 mV with 10 μM [Ca2+]i. Channel openings are upward. Traces were selected to illustrate current amplitude substates (*). A, the internal solution contained 5 mM Na+ and 150 mM K+ and the external solution contained 155 mM Na+ and 5 mM K+. B, internal and external solutions were symmetrical, with 5 mM Na+ and 150 mM K+. C, current- membrane potential (Vm) curves from two inside-out patches in symmetrical 5 mM [Na+]o plus different K+ gradients (substituting Na+ for K+) with 10 μM [Ca2+]i. Ratios indicated are for : (both mM). Current-voltage relations were fitted to the theoretical potassium current using a modified Goldman current equation that included a term used to subtract the sodium component (Methods, eqn (2)).

RESULTS

Characterization of the steady-state behaviour of the KCa channel

Identification of the KCa channel

We used single-channel recordings to characterize the presynaptic KCa channels in detail. Cell-attached recordings from the calyx nerve terminals exhibited little or no channel activity at membrane potentials up to +20 mV. However, after excision into high [Ca2+]i, 145/181 membrane patches exhibited active K+ channels. Of the remaining patches, 21 exhibited no channel activity and 15 exhibited a smaller-conductance channel that was not examined further. Channel conductance was 210 ± 7 pS (n = 20) in symmetrical 150 mM K+ solutions, as calculated from the slope of the I-V curve over the -60 to +60 mV range. These single-channel currents were blocked by external TEA or the peptide toxin CTX or by internal Ba2+ ions, confirming their identity as large-conductance KCa channels (BK channel; Fig. 1). The block by all three agents was reversible, with TEA or Ba2+ block relieved immediately on removal, whereas CTX block reversed only slowly.

Ion selectivity

Channels were examined in excised patches in order to completely control the ions on both sides of the membrane. The BK channel had a large conductance and usually opened to a single current level (e.g. Fig. 1). However, infrequent subconductance states were also observed and these could be resolved to defined levels in selected traces (Fig. 2A and B).

The conductance of the main open state was compared at different K+:Na+ ratios (Fig. 2C). In all gradients the current reversal was close to the calculated K+ equilibrium potential, EK, confirming the high selectivity for K+. PK/PNa was ∼32, calculated using eqn (1) and the difference between the calculated EK and the reversal potential, EREV, estimated by eye from the data with 150 mM K+ and 5 mM Na+ in the extracellular solution and 20 mM K+ and 135 mM Na+ in the internal solution. From a least-squares fit of each of the curves in Fig. 2C to eqn (2), PK was estimated to be 4.04 ± 0.15 × 10−13 cm s−1 (range, 3.62-4.39; n = 5), a value that is very close to that reported previously (Carl & Sanders, 1989).

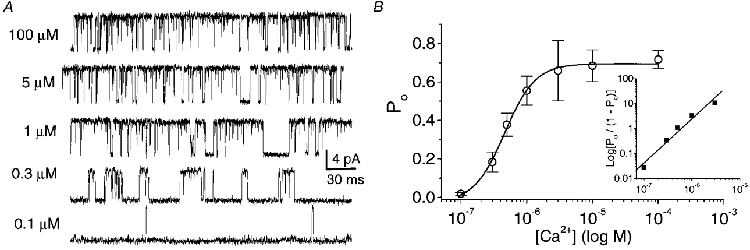

Calcium and voltage dependence of the BK channel

The steady-state open probability as a function of [Ca2+]i was examined using inside-out patches held at a constant voltage of +60 mV. At this potential Po increased steeply with increasing [Ca2+]i and channel openings were observed at a cytoplasmic calcium level as low as 0.1 μM (Fig. 3), reaching a plateau at 5-10 μM. The average data from three to eight single-channel recordings were well fitted with a dose-response curve, to give a dissociation constant (KD) of ∼5 × 10−7 and an estimated Po(max) at +60 mV of ∼0.7. A Hill plot gave a slope of ∼2, suggesting strong co-operative binding of at least two calcium ions, or weaker co-operative binding of more than two ions, to maximally activate the channel.

Figure 3. Effects of [Ca2+]i on BK open probability.

A, representative unitary KCa current in an inside-out patch recorded at +60 mV in symmetrical K+ (150 mM) and in various [Ca2+]i. B, the effect of [Ca2+]i on open probability (Po). Each point represents the average of 3-8 single-channel patch recordings at a holding potential (Vh) of +60 mV. The data are fitted to a dose-response curve with a Po(max) of 0.72 and a KD of 4.8 × 10−7. Inset: Hill plot derived from the first 5 points after normalizing to Po(max). A Hill coefficient of 2.0 was estimated as the slope of a straight line fit to the log-log plot.

We next examined the effect of membrane potential on steady-state channel open probability at different [Ca2+]i levels (Fig. 4A). At each [Ca2+]i the voltage dependence could be fitted by a single Boltzmann relation (Fig. 4B). The effect of increasing [Ca2+]i on the relation between voltage and Po is particularly interesting with respect to three channel properties. First, there was a hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage range over which the channel was active, as indicated by a shift of V½ (Table 1, Fig. 4C). Second, the slope factor of the Boltzmann fit, a reflection of the voltage dependence of the channel, increased at higher [Ca2+]i (Art et al. 1995; Table 1), indicating a reduced voltage dependence when the [Ca2+]i binding sites are occupied. Finally, there was a progressive increase in Po(max) but we did not examine this further.

Table 1. Effect of calcium on the voltage dependence of single BK channel openings.

| [Ca2+]i(μM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 0.5 | 1 | 10 | 100 | |

| V1/2 (mV) | 41.1 | 34.0 | 20.5 | −8.0 | −12.5 |

| Slope factor (mV) | 11.9 | 15.8 | 21.5 | 32.7 | 41.8 |

| n | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

Pooled data from n individual single-channel patch recordings were fitted to a Boltzmann curve for each [Ca2+]i.

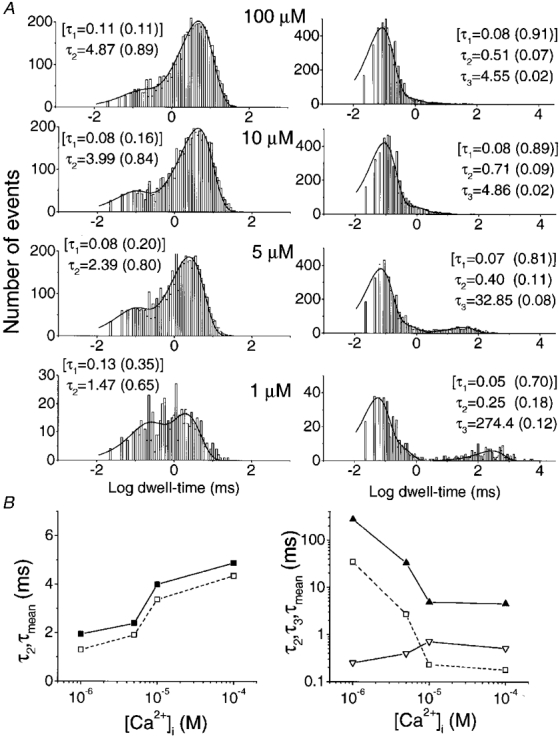

BK channel kinetics

Patches with single KCa channels (e.g. Fig. 4A) were used to analyse open-closed kinetics at different [Ca2+]i levels. Channel behaviour could be adequately described by two open and three closed states (Fig. 5A). The fastest (τ1) open and closed states were used for fitting purposes only since they were too brief to be resolved reliably under our recording conditions. Increasing [Ca2+]i increased the duration of the slow open state and markedly decreased the duration of the slowest closed state (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Intracellular Ca2+ modulates the steady-state kinetics of the BK channel.

Single-channel current fluctuations were recorded at various [Ca2+]i levels in inside-out patches held at +60 mV in symmetrical 150 mM K+ solutions. A, fitted dwell-time histograms are shown for a typical single-channel recording (e.g. Fig. 3A). Open times (left panels) were fitted with double exponentials and closed times (right panels) with three exponentials, with the time constants indicated on each panel. The fastest time constants (τ1, square brackets) in each case were too short to be measured reliably and were used for fitting purposes only. The numbers in parentheses show the fractional contribution of each component to the area under the curve. B, open (left) and closed (right) time constants for the reliably measured slow (τ2, ▪, left; τ3, ▴, right), intermediate (τ2, ▿, right) and mean time constants (□). Results are from the data in Fig. 5A.

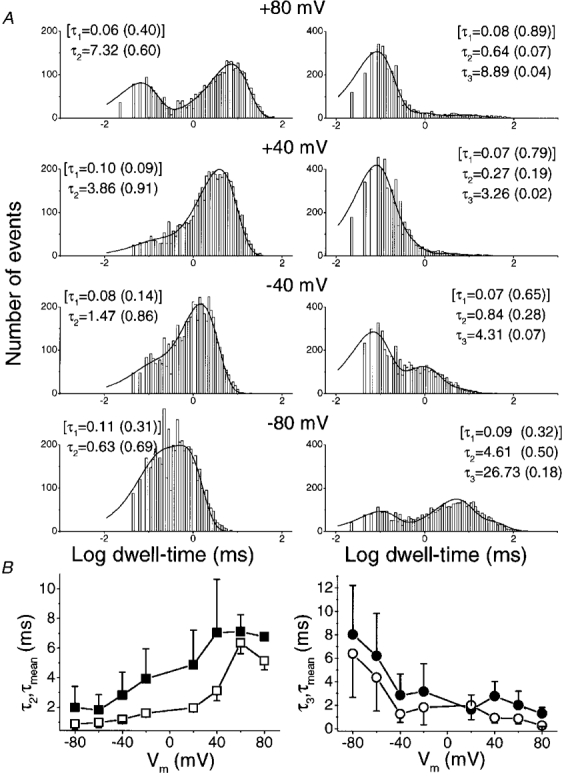

We also examined the effect of voltage on steady-state single-channel kinetics (Fig. 6). Data were analysed as in Fig. 5 but at different holding potentials and at a fixed [Ca2+]i of 100 μM. Again, the slowest time constants were the most sensitive to voltage shifts for both open and closed states (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Voltage modulates the steady-state kinetics of the KCa channel. Inside-out patches, exposed to symmetrical 150 mM K+ solutions with 100 μM [Ca2+]i, were held at various membrane potentials.

A, fitted dwell-time histograms for a representative single-channel patch held at four membrane potentials. Data were analysed and are presented as in Fig. 5. B, open (left) and closed (right) time constants for the reliably measured slow (τ2, ▪, left; τ3, •, right) and mean time constants (□, ^) averaged for 4 single-channel patches.

Channel inactivation

In general, the channels did not inactivate during sustained depolarizations, as is evident from the observed high Po(max) (Figs 3 and 5). However, inactivation was observed during a depolarizing voltage pulse in about 4 % of the patch recordings (8/181 patches; Fig. 7A). Openings were clustered at the beginning of the trace and ensemble averages demonstrated an inactivating current. The rate of inactivation was weakly voltage dependent and the time constant decreased with the degree of depolarization (Fig. 7A and B).

Relation of the KCa channel to the nerve terminal

BK channel properties and location

We carried out a limited comparison of BK channel properties at two main regions of the calyx: on the back, Schwann cell-facing aspect, or on the front, transmitter-release face aspect (Table 2). Channels were noted in most patches at both locations and there were no obvious differences in channel conductance nor in calcium sensitivity.

Table 2. Comparison of the properties of BK channels recorded from the calyx nerve terminal transmitter release face with those on the back face.

| Location | Frequency* | Single-channel conductance†(pS) | KD‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Release face | 100% (6/6) | 217.0 ± 10.4 (4) | 7.7 ± 10−6 (2) |

| Back face | 80% (24/30) | 200.3 ± 8.2 (5)§ | 8.0 ± 10−6 (2) |

Percentage of patches with BK channel activity (positive patches/number of patches examined).

Mean ± S.E.M. (number of trials).

Ca2+ dissociation constant calculated at +40 mV (number of single-channel patches).

P gt; 0.05 (Student's t test) vs. release face.

Activation by calcium domains

We recorded BK channels in situ in the cell-attached configuration to test whether these channels could be activated by calcium channels in the same membrane region. This was tested by first examining BK channel activation during a sufficiently large depolarization (to +80 mV) to inhibit calcium influx (i.e. to well beyond the reversal potential, Erev, ∼+65 mV; see Stanley, 1991). The amount of BK current activated at +80 mV was then compared after a short pre-pulse to a potential within the range that allows calcium influx (-20 or 0 mV, n = 7). We selected patches that were likely to be located on the transmitter-release face of the nerve terminal, the location of the calcium channels (Stanley, 1991). Representative experiments are shown in Fig. 8, from a multi-channel patch, and Fig. 9, from a single-channel patch. Some openings were observed in the absence of a prepulse (Figs 8A and 9A), as expected from their voltage dependence, but these were enhanced by the short conditioning pulse to above threshold for opening calcium channels (Fig. 8B and 9B). A small inward current, consistent with a calcium current, is evident during the prepulse in Fig. 9B but in Fig. 8B this was too small to detect. The presence and activation of a calcium current in the patch in Fig. 9B is evident from the prominent inward tail current at the end of the +80 mV test pulse. The lack of effect of a +80 mV prepulse (Fig. 8C) demonstrates that the recruitment of BK channel activity is not simply due to a preceding depolarization. Further, no increase in Po was observed with a prepulse to -20 mV when Ca2+ channels were blocked by ω-conotoxin GVIA in the external solution in the patch electrode (n = 2; data not shown). By subtracting the ensemble averaged currents in the single-channel recording, a prepulse-induced increase in BK ensemble current (and thus Po) was revealed (Fig. 9D). This observation, together with the decreased time to first channel opening after prepulses to -20 or 0 mV (Figs 8C and 9E) demonstrated that BK channel activity resulted from changes in channel kinetics, and did not require recruitment of new channels. The simplest interpretation of these findings is that Ca2+ influx through the calcium channels in the membrane patch activated the neighbouring KCa channels.

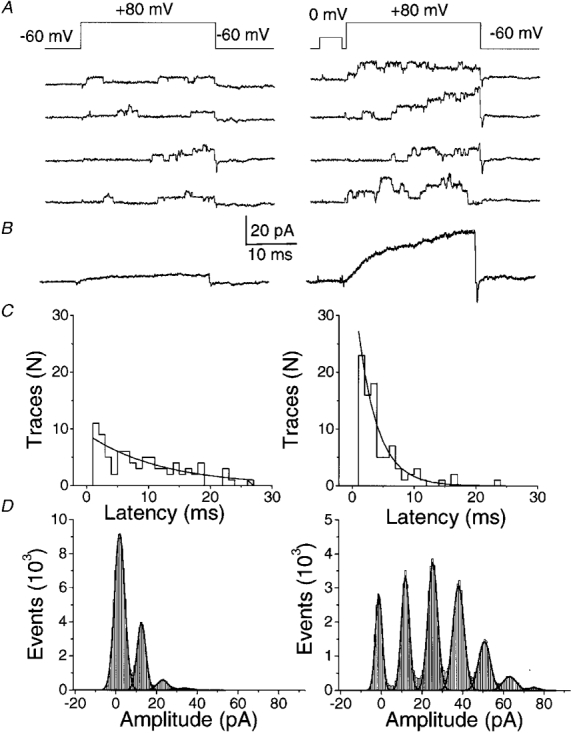

Figure 8. BK single-channel current is recruited by prepulses favouring Ca2+ entry.

Depolarizing pulses to +80 mV (above, Erev) were applied from a holding potential of -60 mV to the same cell-attached patch containing multiple BK channels either without (all left panels) or following (all right panels) a 5 ms prepulse to 0 mV. A, examples of individual sweeps. B, currents calculated as the average of 100 traces. C, histograms of latency to first opening after the pulse to +80 mV. D, all-points amplitude histograms with (left panel) and without (right panel) a prepulse. Each peak above 0 pA corresponds to one open channel. The pipette contained SES with 10 mM CaCl2 while the bath contained 150 mM K+ solution.

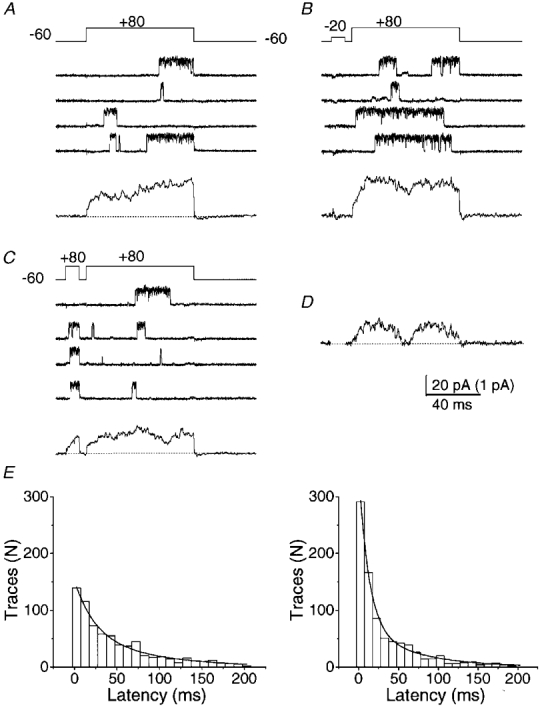

Figure 9. A depolarizing prepulse can increase the open probability of a single BK channel in a cell-attached patch.

Test pulses were given to +80 mV (above, Erev) from a holding potential of -60 mV. Four individual current traces and their respective ensemble average of 200 traces (below) are shown in the absence of a prepulse (A) or following a 10 ms prepulse to -20 mV (B) or +80 mV (C) in the same patch. Recording solutions were as in Fig. 8. D, subtraction of ensemble current in C from that in B shows the current activated by the -20 mV prepulse (ensemble average current). For clarity, the current during the prepulse has been blanked. The scale bar for the ensemble currents is 1 pA. E, time to first opening of BK channels after the onset of the test pulse to +80 mV without (left) or following (right) a prepulse to -20 mV. Data are pooled from 1200 sweeps from 6 calyces. The smooth curves were fitted to double exponential functions with time constants of 23.5 and 81.6 ms in the control (no prepulse) and 12.0 and 62.4 ms in the prepulse group.

BK channel density

In over 180 cell-attached patches the highest density of BK channels was six channels, as shown in Fig. 8. The bulk of patches exhibited one to three channels.

DISCUSSION

The object of this study was to identify and characterize a BK channel on a vertebrate presynaptic nerve terminal at a fast-transmitting synapse. Nerve terminal BK channels have previously been characterized at the single-channel level in only two preparations, the neurosecretory terminal of the posterior pituitary (Bielefeldt et al. 1992), which secretes hormones, and the efferent terminals in the organ of Corti (Wangemann & Takeuchi, 1993), which modulates a sensory hair cell. The present results represent the first examination of the single-channel properties of BK channels in the presynaptic terminal of a neuron-to-neuron synapse.

We find that the presynaptic KCa channel has many properties in common with a subset of BK channels recorded in a variety of cell types (see Vergara et al. 1998, for a recent review). Four properties are of particular interest with regard to nerve terminal function. First, block by CTX is reversible, second, calcium affinity is in the low to mid range for this channel type, third, the channels exhibit a strong voltage dependence particularly at low [Ca2+]i and, finally, we present evidence that these channels can be activated by [Ca2+]i influx through neighbouring calcium channels.

The calyx BK channel was blocked by the peptide toxin, CTX, as is typical for channels of this type. We did not determine the affinity of CTX binding but did note that after repeated washing the block was reversible. Previous studies report that KCa currents in other presynaptic terminals range from those that are blocked by CTX (Schneider et al. 1989; Robitaille et al. 1993) to those that are totally insensitive (Bielefeldt et al. 1992; Blundon et al. 1995).

The BK channel was highly selective for potassium over sodium and exhibited an outward current over the entire physiological range (-75 to +50 mV), as is typical of this channel type. At +60 mV the BK channel was essentially closed at 100 nM [Ca2+]i but reached maximal activation at ∼3 μM. Thus, these presynaptic BK channels are of moderate calcium sensitivity, similar to those at the organ of Corti synapse (Wangemann & Takeuchi, 1993) and only slightly less sensitive than those at the posterior pituitary neurosecretory terminal (Bielefeldt et al. 1992). Again, in common with many other reports on BK channels and with data from the posterior pituitary neurosecretory terminal we obtained a Hill coefficient of ∼2. Although this has been taken to suggest that two calcium ions are necessary to activate this channel it is safer to conclude that a minimum of two are required. Furthermore, Hill coefficients have been determined only for steady-state behaviour: the dependence may be steeper when the channel is activated, as it almost certainly is in vivo, by acute increases in [Ca2+]i.

The open and closed times determined from single-channel recordings in different [Ca2+]i could be fitted by two open and three closed states, consistent with many previous studies on this channel type (Vergara et al. 1998). However, the shortest of the open and closed times were too rapid to be recorded reliably under our conditions. Of the kinetic states that could be examined, the slowest closed state was the most sensitive to [Ca2+]i.

The voltage dependence of the channel open probability was examined at steady state across a wide range of calcium concentrations. The open probability curve shifted to more hyperpolarized potentials with increases in [Ca2+]i. As observed in BK channels in cell bodies (Vergara et al. 1998) as well as in the posterior pituitary neurosecretory terminal (Bielefeldt et al. 1992), there was a reduction in the steepness of the voltage dependence of the relation at higher [Ca2+]i. This finding has been interpreted to indicate an independence of the calcium and voltage effects on channel gating (Cui et al. 1997; Vergara et al. 1998). It is of particular interest that the observed shift in slope can be virtually superimposed on results reported recently for expressed hslo channels in frog oocytes (DiChiara & Reinhart, 1995). Analysis of the single-channel kinetics demonstrated that voltage affected both the channel open and closed states, with the primary effect on the slowest observed rate constants. In all, gating of BK channels is highly controlled, depending as it does on both a [Ca2+]i increase and membrane depolarization. This is in contrast to small-conductance KCa (SK) channels that are gated by [Ca2+]i alone. A dual control mechanism for high-conductance K+ channels, with its greater control over random openings, may be necessary at presynaptic terminals where channel openings are likely to markedly affect the input impedance. This is of particular importance in the much smaller bouton-type presynaptic nerve terminal in which a single BK channel opening might severely attenuate action potential invasion and, hence, transmitter release.

In a few cases the calyx BK channels exhibited inactivation during sustained depolarizations but the inactivation rate was only weakly voltage sensitive and was slow at even the most depolarized potentials. Thus, as in the posterior pituitary neurosecretory terminal, inactivation is not a prominent feature of the presynaptic BK channel, unlike that observed in adrenal chromaffin cells (Solaro et al. 1995). Nonetheless, the presence of inactivation is of interest since it may indicate either a different variant (Chang et al. 1997; Farley & Rudy, 1998) or that the channels can be modulated by a second-messenger system (e.g. Egan et al. 1993).

The BK channels detected in this, as well as in the two other nerve terminal preparations examined, exhibit characteristics consistent with those reported for expressed hslo KCa channels (DiChiara & Reinhart, 1995). Expressed BK channels can be modified by a β subunit which has been reported to markedly increase both sensitivity to block by CTX (Hanner et al. 1997) and activation by calcium (McManus et al. 1995). This subunit is not essential and the channel has been reported to exist and function in its absence (McManus et al. 1995; Chang et al. 1997). It is interesting to note that the BK channel expressed in the absence of the β subunit exhibits a [Ca2+]i dependence and CTX sensitivity that are similar to those observed here and to those reported previously in the organ of Corti (Wang et al. 1992) and the posterior pituitary neurosecretory terminal (Bielefeldt & Jackson, 1993). This raises the possibility that nerve terminal BK channels exist in the β subunit-free state. Whether this is in fact the case, and whether this represents a general property for nerve terminal BK channels will require further study. Even so, the reported range of sensitivities to CTX indicate that there is some additional variability in presynaptic BK channel characteristics.

Several lines of evidence suggest that BK channels can be activated by the plume, or domain, of ions entering through closely associated calcium channels (Roberts et al. 1990; Gola & Crest, 1993; Thompson, 1994; Protti & Uchitel, 1997; Marrion & Tavalin, 1998). Since the calcium channels and the BK channels are physically co-localized at the nerve terminal (Robitaille et al. 1993) domain-based activation might be expected, as appears also to be the case for transmitter release (Stanley, 1997). Evidence for a close association of these channel types in presynaptic structures has been presented at the hair cell (Roberts et al. 1990), and the neuromuscular junction (Yazejian et al. 1997; Protti & Uchitel, 1997) and our results are consistent with these findings.

We did not note any obvious differences between transmitter release face and non-release face BK channels. In over 180 recordings from membrane patches we never observed more than six BK channels in a single patch, a channel density that is consistent with estimates from whole-terminal recordings at the frog neuromuscular junction in culture (Yazejian et al. 1997). This contrasts markedly with the density of single calcium channels recorded at the calyx transmitter release face which can exceed 200 channels in similar sized patches (Stanley, 1991; Haydon et al. 1994). If both the BK and calcium channels are located along the secretory zones, as suggested by immunofluorescent staining (Robitaille et al. 1993), the BK channels are presumably dispersed amongst the much more numerous calcium channels.

References

- Anderson AJ, Harvey AL, Rowan EG, Strong PN. Effects of charybdotoxin, a blocker of Ca2+-activated K+ channels, on motor nerve terminals. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1988;95:1329–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Art JJ, Wu Y-C, Fettiplace R. The calcium-activated potassium channels of turtle hair cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1995;105:49–72. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrand P, Stjarne L. A calcium-dependent component of the action potential in sympathetic nerve terminals in rat tail artery. Pflügers Archiv. 1991;418:102–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00370458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartschat DK, Blaustein MP. Calcium-activated potassium channels in isolated presynaptic nerve terminals from rat brain. The Journal of Physiology. 1985;361:441–457. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt K, Jackson MB. A calcium-activated potassium channel causes frequency-dependent action-potential failures in a mammalian nerve terminal. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70:284–298. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.1.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt K, Rotter JL, Jackson MB. Three potassium channels in rat posterior pituitary nerve terminals. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;458:41–67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blundon JA, Wright SN, Brodwick MS, Bittner GD. Presynaptic calcium-activated potassium channels and calcium channels at a crayfish neuromuscular junction. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;73:178–189. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A, Tsunoda S, McCobb DP, Wei A, Salkoff L. mSlo, a complex mouse gene encoding ‘Maxi’ calcium-activated potassium channels. Science. 1993;261:221–224. doi: 10.1126/science.7687074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl A, Sanders KM. Ca2+-activated K channels of canine colonic myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257:C470–480. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.257.3.C470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle NA, Strong PN. Identification of two toxins from scorpion (Leiurus quinquestriatus) venom which block distinct classes of calcium-activated potassium channel. FEBS Letters. 1986;209:117–121. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CP, Dworetzky SI, Wang J, Goldstein ME. Differential expression of the a and b subunits of the large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel: implications for channel diversity. Molecular Brain Research. 1997;45:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Cox DH, Aldrich RW. Intrinsic voltage dependence and Ca2+ regulation of mslo large conductance Ca-activated K+ channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;109:647–673. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.5.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiChiara TJ, Reinhart PH. Distinct effects of Ca2+ and voltage on the activation and deactivation of cloned Ca2+-activated K+ channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;489:403–418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgington DR, Stewart AE. Properties of tetraethylammonium ion-resistant K+ channels in the photoreceptor membrane of the giant barnacle. Journal of General Physiology. 1981;77:629–646. doi: 10.1085/jgp.77.6.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan TM, Dagan D, Levitan IB. Properties and modulation of a calcium-activated potassium channel in rat olfactory bulb neurones. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;5:1433–1442. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.5.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley J, Rudy B. Multiple types of voltage-dependent Ca2+-activated K+ channels of large conductance in rat brain synaptosomal membranes. Biophysics Journal. 1988;53:919–934. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83173-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gola M, Crest M. Colocalization of active KCa channels and Ca2+ channels within Ca2+ domains in helix neurones. Neuron. 1993;10:689–699. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90170-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanner M, Schmalholfer WA, Munujos P, Knaus HG, Kaczorowski GJ, Garcia ML. The beta subunit of the high-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel contributes to the high-affinity receptor for charybdotoxin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:2853–2858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon PG, Henderson E, Stanley EF. Localisation of individual calcium channels at the release face of a presynaptic nerve terminal. Neuron. 1994;13:1275–1280. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa NP, Hudspeth AJ. Clustering of Ca2+ channels and Ca2+-activated K+ channels at fluorescently labelled presynaptic active zones of hair cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:7578–7582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz E, Protti DA, Ferro PA, Rosato Siri MD, Uchitel OD. Effects of Ca2+ channel blocker neurotoxins on transmitter release and presynaptic currents at the mouse neuromuscular junction. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;121:1531–1540. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus HG, Schwarzer C, Koch RO, Eberhart A, Kaczorowski GJ, Glossmann H, Wunder F, Pongs O, Garcia ML, Sperk G. Distribution of high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in rat brain: targeting to axons and nerve terminals. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:955–963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-00955.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto E, Kuba K. Effects of K+-channel blockers on transmitter release in bullfrog sympathetic ganglia. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1985;235:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren CA, Moore JW. Identification of ionic currents at presynaptic nerve endings of the lizard. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;414:201–222. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus OB, Pallanck L, Helms LMH, Swanson R, Leonard RJ. Functional role of the b subunit of high conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Neuron. 1995;14:645–650. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrion NV, Tavalin SJ. Selective activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels by co-localised Ca2+ channels in hippocampal neurones. Nature. 1998;29:900–905. doi: 10.1038/27674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protti DA, Uchitel OD. P/Q-type calcium channels activate neighbouring calcium-dependent potassium channels in mouse motor nerve terminals. Pflügers Archiv. 1997;434:406–412. doi: 10.1007/s004240050414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahamimoff R, Edry-Schiller J, Rubin-Fraenkel M, Butkevich A, Ginsburg S. Oscillations in the activity of a potassium channel at the presynaptic nerve terminal. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;73:2448–2458. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.6.2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WM, Jacobs RA, Hudspeth AJ. Colocalization of ion channels involved in frequency selectivity and synaptic transmission at presynaptic active zones of hair cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:3664–3684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03664.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WM, Jacobs RA, Hudspeth AJ. The hair cell as a presynaptic terminal. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 1991;635:221–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb36494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille R, Charlton MP. Presynaptic calcium signals and transmitter release are modulated by calcium-activated potassium channels. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:297–305. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-01-00297.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille R, Garcia ML, Kaczorowski GJ, Charlton MP. Functional colocalization of calcium and calcium-gated potassium channels in control of transmitter release. Neuron. 1993;11:645–655. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Ishikane H, Tachibana M. Ca2+-activated K+ current at presynaptic terminals of goldfish retinal bipolar cells. Neuroscience Research. 1997;27:219–228. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)01155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MJ, Rogowski RS, Krueger BK, Blaustein MP. Charybdotoxin blocks both Ca-activated K channels and Ca-independent voltage-gated K channels in rat brain synaptosomes. FEBS Letters. 1989;250:433–436. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80771-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishnan S, Bittner GD, Brodwick MS. Calcium-activated potassium conductance in presynaptic terminals at the crayfish neuromuscular junction. Journal of General Physiology. 1991;98:1161–1179. doi: 10.1085/jgp.98.6.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Phillips M, Miller C. Purification of charybdotoxin, a specific inhibitor of the high-conductance Ca2+ calcium-activated K+ channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:14607–14613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaro CR, Prakriya M, Ding JP, Lingle CJ. Inactivating and noninactivating Ca2+- and voltage-dependent K+ current in rat adrenal chromaffin cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:6110–6123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06110.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley EF. Calcium currents in a vertebrate presynaptic nerve terminal: the chick ciliary ganglion calyx. Brain Research. 1989;505:341–345. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley EF. Single calcium channels on a cholinergic presynaptic nerve terminal. Neuron. 1991;7:585–591. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley EF. The calcium channel and the organisation of the presynaptic transmitter release face. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:404–409. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley EF, Goping G. Characterisation of a calcium current in a vertebrate cholinergic presynaptic nerve terminal. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:985–993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-00985.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stretton D, Miura M, Belvisi MG, Barnes PJ. Calcium-activated potassium channels mediate prejunctional inhibition of peripheral sensory nerves. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:1325–1329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi S, Wangemann P. Aminoglycoside antibiotics inhibit maxi-K+ channel in single isolated cochlear efferent nerve terminals. Hearing Research. 1993;67:13–19. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90227-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SH. Facilitation of calcium-dependent potassium current. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:7713–7725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07713.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozer KR, Mirotznik RR, Stanley EF. Characterisation of voltage-gated potassium channels in a presynaptic nerve terminal. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1998;24:1331. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara C, Latorre R, Marrion NV, Adelman JP. Calcium-activated potassium channels. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1998;8:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Lemos JR. Tetrandrine blocks a slow, large-conductance, Ca2+-activated potassium channel besides inhibiting a non-inactivating Ca2+ current in isolated nerve terminals of the rat neurohypophysis. Pflügers Archiv. 1992;421:558–565. doi: 10.1007/BF00375051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Thorn P, Lemos JR. A novel large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel and current in nerve terminals of the rat neurohypophysis. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;457:47–74. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P, Takeuchi S. Maxi-K+ channels in single isolated cochlear efferent nerve terminals. Hearing Research. 1993;66:123–129. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90133-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei A, Solaro C, Lingle CJ, Salkoff L. Calcium sensitivity of BK-type KCa channels determined by a separable domain. Neuron. 1998;13:671–681. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazejian B, Digregorio DA, Vergara JL, Poage RE, Meriney SD, Grinnell AD. Direct measurements of presynaptic calcium and calcium-activated potassium currents regulating neurotransmitter release at cultured Xenopus nerve-muscle synapses. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:2990–3001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-02990.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]