Abstract

Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport activity was measured in ferret erythrocytes as the bumetanide-sensitive uptake of 86Rb.

The Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport rate was stimulated by treating erythrocytes with sodium arsenite but not by sodium arsenate (up to 1 mM). Stimulation took an hour to develop fully. Arsenite had no effect on bumetanide-resistant 86Rb uptake.

In cells stored for 3 days or less, cotransport stimulation by arsenite could be described by assuming arsenite either acts at a single site (EC50, 60 ± 14 μM, mean ± s.e.m., n = 3) or that it acts at both high- (EC50, 35 ± 9 μM, mean ± s.e.m., n = 3) and low- (EC50 > 2 mM) affinity sites.

Stimulation by 1 mM arsenite was greatest on the day of cell collection (rate about 3 times that of the control), even exceeding that produced by 20 nM calyculin A, and declined during cell storage. Addition of calyculin A to arsenite-stimulated cells resulted in further stimulation of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport, suggesting that arsenite and calyculin act synergistically. This was most apparent in stored cells.

Stimulation by 1 mM arsenite was not affected by treating cells with the mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors SB203580 (20 μM) and PD98059 (50 μM), but was both prevented and reversed by the kinase inhibitors staurosporine (2 μM), 4-amino-5-(4-methylphenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine (PP1, 50 μM) and genistein (0.3 mM), and with a combination of 10 μM A23187 and 2 mM EDTA (to reduce intracellular Mg2+ concentration). Only treatment with EDTA and A23187 prevented stimulation by the combination of 1 mM arsenite and 20 nM calyculin, whereas no treatment was able to fully reverse this stimulation once elicited.

Our data are consistent with arsenite stimulating (perhaps indirectly) a kinase that phosphorylates and activates the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter.

The Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport system plays an important role in the regulation of cell K+ and Cl− content and cell volume (O'Grady et al. 1987; Haas, 1989, 1994; Haas & Forbush, 1998). Its activity is regulated by the concentration of its substrate ions and also by a variety of physiological stimuli including cell shrinkage, hypoxia and hormones (Haas & Forbush, 1998), and it is inhibited by bumetanide and other loop diuretics. Several stimuli affect cotransporter activity by altering protein phosphorylation (Alper et al. 1980), a link that can be disrupted by treating cells with inhibitors of protein kinases and phosphatases (Pewitt et al. 1990; Klein et al. 1993; Palfrey & Pewitt, 1993; Krarup et al. 1998; Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). Recent work shows that the cotransporter itself is phosphorylated (at multiple sites) and activated when cells are shrunk or treated with a variety of pharmacological agents (Lytle & Forbush, 1992; Tanimura et al. 1995; Lytle, 1997). However, it also seems likely that the phosphorylation of cytoskeletal proteins that are associated with the cotransporter may affect the transport rate independently of the cotransporter's own phosphorylation state (Matthews et al. 1994; Klein & O'Neill, 1995; D'Andrea et al. 1996; Haas & Forbush, 1998; Matthews et al. 1998).

To date, it has not been possible to identify the kinase (or kinases) responsible for phosphorylation of the cotransporter nor to find potent and reasonably specific inhibitors of kinase activity. The most potent protein kinase inhibitors tested (staurosporine and 4-amino-5-(4-methylphenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine (PP1)) only partially inhibit the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter in ferret erythrocytes, an effect that is mimicked by reducing intracellular Mg2+ concentration to micromolar levels (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). These interventions also prevent activation of the transporter by the potent protein phosphatase inhibitor calyculin A, but only partially inhibit transport once stimulated by calyculin. On the basis of these observations it has been suggested that staurosporine and PP1 activate the phosphatase (see Fig. 8) by preventing its phosphorylation (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). The active phosphatase then dephosphorylates the cotransporter and thus inhibits transport.

Figure 8. Proposed model for Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport regulation in ferret erythrocytes.

The cotransporter (COT) is phosphorylated, perhaps at multiple sites (to COT-P) by a kinase or kinases, which are lumped together as kinase K1, and dephosphorylated by a phosphatase or phosphatases, P1. Increased levels of COT-P are associated with increased rates of transport (Lytle, 1997). The transport rate is also affected by interactions between the cotransporter and the cytoskeleton (Klein & O'Neill, 1995; Matthews et al. 1998). The activity of P1 is inhibited by phosphorylation catalysed by kinase K2, an enzyme that is inhibited (directly or indirectly) by staurosporine, PP1 and possibly genistein (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). P1 is dephosphorylated by phosphatase P2, an enzyme that is inhibited by calyculin A. Reduction of [Mg2+]i to very low levels inhibits all kinases and possibly phosphatase P1 (Mildvan, 1987; Flatman, 1988; Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). Genistein may also directly inhibit the cotransporter (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). Our observations suggest that arsenite stimulates cotransport by acting through a single common pathway in this scheme - the activation of kinase K1, an effect which may be indirect, and may occur at several steps.

In our quest for an inhibitor of the kinase(s) we decided to screen compounds that interfere with stress-activated protein kinases (SAPK) and the related mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK). This looked a promising approach as these kinases are involved in the response to osmotic and hypoxic stress, as well as to a wide range of pharmacological agents in several organisms. We started by examining the effects of SB203580, an inhibitor of p38 MAPK and PD98059, an inhibitor of p42/p44 MAPK (Brunet & Pouysségur, 1997). p38 MAPK is similar to the yeast HOG1 gene product that is involved in responses to osmotic pressure (Brewster et al. 1993), whereas p42/p44 is activated by growth factors (Brunet & Pouysségur, 1997). We also wanted to examine the possible involvement of p46/p54 SAPKs as these have also been implicated in the response to osmotic shock and to hypoxia (Brunet & Pouysségur, 1997; Seko et al. 1997). Unfortunately, specific inhibitors for these kinases have not yet been developed, so we opted to examine the effects of anisomycin and sodium arsenite, compounds that have been used to activate MAPKs and SAPKs in several cell types (Kyriakis et al. 1994; Cavigelli et al. 1996; Ludwig et al. 1998). To our surprise we found that arsenite caused the largest stimulation of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport activity by any agent tested to date, whereas anisomycin caused inhibition. In this paper, we examine the nature of the stimulation caused by arsenite, an ion found widely in the environment, and consequently at high levels in the water supplies of several regions of the world (Snow, 1992).

A preliminary account of part of this work was given at a meeting of The Physiological Society (Flatman & Creanor, 1999a).

METHODS

All solutions were prepared in double glass distilled water with reagents of analytical quality (AnalaR, Merck). Experiments were carried out in ferret basic medium (FBM, mM: NaCl, 145; KCl, 5; EGTA, 0.05 and Hepes, 10, pH 7.5 at 38°C, adjusted with NaOH). Chemicals were obtained as follows: sodium (meta)-arsenite (Fluka Chemicals), calyculin A (Alexis Corporation Ltd, Nottingham, UK), genistein (Sigma or Calbiochem), 4-amino-5-(4-methylphenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine (PP1; Calbiochem or Alexis). Staurosporine, sodium arsenate, EDTA, EGTA, Hepes and Tris base were obtained from Sigma, and A23187, SB203580, PD98059 and anisomycin from Calbiochem. A 10 mM stock of bumetanide (a gift from Leo Laboratories Ltd, Aylesbury, UK) was prepared in water neutralized with Tris base.

Blood was taken by cardiac puncture into EDTA from adult ferrets terminally anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (Sagatal, Rhône Mérieux; 120 mg kg−1i.p.). Cells were washed 4 times by centrifugation and resuspended in FBM, care being taken to completely remove the buffy coat. Cells were stored, packed at about 80 % haematocrit in FBM, at 4°C until used. All solutions used for handling blood were sterilized by passage through a 0.2 μm filter (Millipore).

All fluxes were determined at 38°C in well-stirred suspensions of ferret erythrocytes (5–10 % haematocrit) in FBM containing 11 mM glucose. Potassium influx was determined using 86Rb (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as tracer as described previously (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). Fluxes through the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter were defined as the components of 86Rb uptake inhibited by 10–20 μM bumetanide. This represented more than 95 % of 86Rb uptake in the experiments described here. As none of the treatments described in this paper caused a major change in the bumetanide-resistant 86Rb fluxes (86Rb influx rate constants ranged between 0.1 and 0.16 h−1), the effects reported for total fluxes (rate constants between 1 and 10 h−1) are almost entirely a result of changes in the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport rate.

In order to inhibit protein kinases reversibly, cell Mg2+ content was reduced to very low levels by treating cells with 10 μM of the ionophore A23187 and 2 mM EDTA for 15 min. Under these conditions the free ionized intracellular Mg2+ concentration ([Mg2+]i) is estimated to be less than 1 μM (Flatman, 1988). However, this treatment may also deplete cells of ions such as Ca2+ and Zn2+ as A23187 can also transport other divalent cations that bind strongly to EDTA. Although the concentration of these ions is low in erythrocytes, possible interference from this effect should be borne in mind when interpreting the results. For instance, a reduction in the cell Zn2+ concentration could disinhibit some tyrosine phosphatases (Brautigan & Shriner, 1988).

Haematocrit and cell ATP content were determined as described previously (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). Cell contents are expressed as the amount found in a litre of cells at their original volume (loc).

All experiments were repeated at least twice with blood from different ferrets, and either representative rate constants are given together with the standard error of the estimate, or mean values are given with the standard error of the mean, in which case the number of repeats (n) is given in parentheses. Where necessary, the significance of the difference between means was assessed with a Student's two-tailed, unpaired t test. Curves in Fig. 3 were fitted to the data according to specific models, using non-linear regression analysis (Levenberg-Marquardt method). Goodness of fit is indicated by R2.

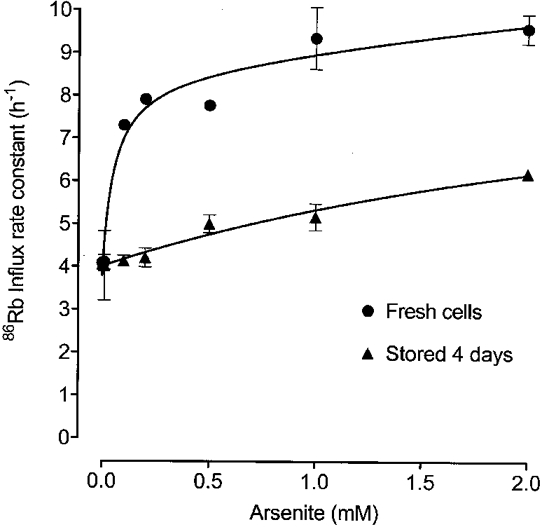

Figure 3. The effect of arsenite concentration on 86Rb uptake in fresh and 4-day-old cells.

86Rb uptake was determined in erythrocytes from one ferret shortly after collection (•) and after 4 days' storage at 4 °C (▴). Cells were washed and incubated at 38 °C in FBM containing 11 mM glucose and the indicated sodium arsenite concentrations for 60 min. 86Rb was added to the suspensions and the 86Rb uptake rates determined. Rate constants are shown with standard errors if these are larger than the point size. Lines were drawn using non-linear regression analysis. With fresh cells, three components were found, a constant at 3.79 h−1 and two saturating components with EC50 values of 0.051 and 16.9 mM, and maximal rates of 4.76 and 11.6 h−1, respectively. For the 4-day-old cells only two components were found, a constant at 4.01 h−1, and a saturating component with an EC50 of 3.45 mM and a maximal rate of 5.88 h−1.

RESULTS

The membrane-permeant MAPK inhibitors SB203580 (which inhibits p38 MAPK) and PD98059 (which inhibits p42/p44 MAPK) caused, at most, slight inhibition of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport rate, even at high concentrations and after long exposure. For instance, the 86Rb uptake rate constant was 4.01 ± 0.03 h−1 after exposure of cells to 10 μM SB203580 for 30 min compared with control values of 4.31 ± 0.06 h−1, and exposure of cells to 50 μM PD98059 for 30 min had no significant effect on flux (control, 2.01 ± 0.04 h−1; with PD98059, 1.95 ± 0.03 h−1). Neither drug affected the fluxes measured in the presence of 10 μM bumetanide, a potent cotransport inhibitor (rate constants: 0.15 ± 0.01 h−1 with 10 μM SB203580 compared with 0.16 ± 0.00 h−1 for control cells; 0.12 ± 0.02 h−1 for 50 μM PD98059 compared with 0.11 ± 0.00 h−1 for controls). Incubation of cells for 30 min in media containing anisomycin at 38 μM, a level that activates SAPK in other cells (Kyriakis et al. 1994; Ludwig et al. 1998), caused a slight inhibition of transport (rate constant: 2.05 ± 0.08 h−1 compared with control values of 2.25 ± 0.03 h−1), and this inhibition increased to 39 % (rate constant: 1.37 ± 0.01 h−1) at 380 μM. Anisomycin (380 μM) had no effect on 86Rb uptake in the presence of 10 μM bumetanide (rate constant: 0.16 ± 0.06 h−1 compared with control values of 0.10 ± 0.0 h−1) indicating that the inhibition of total flux reported above is caused solely by inhibition of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport.

Treatment of the cells with sodium arsenite caused a strong stimulation of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport. This stimulation was not apparent for the first 15 min after arsenite addition, but then developed slowly over the next 40 min, and was maximal within 1 h (Fig. 1). Over this same time, arsenite had no effect on 86Rb uptake in the presence of 10 μM bumetanide, the rate constant remaining at about 0.1 h−1 (control, 0.10 ± 0.01 h−1; with arsenite, 0.11 ± 0.01 h−1). Thus the large stimulation of 86Rb uptake by arsenite is due to activation of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport. This stimulatory effect of arsenite was not shared by arsenate, a compound with known deleterious effects in human erythrocytes (Winski & Carter, 1998). The 86Rb uptake rate constant was 3.46 ± 0.25 h−1 (n = 3) after 1 h in 1 mM sodium arsenate compared with 3.45 ± 0.20 h−1 control cells(n = 3).

Figure 1. Time course of activation of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport by sodium arsenite.

Ferret erythrocytes (stored for 2 days) were incubated at 38 °C in FBM containing 11 mM glucose. Control and bumetanide-resistant 86Rb uptake rates were determined in 0.9 ml aliquots of this suspension. Sodium arsenite (0.5 mM) was then added to the suspension at t = 0 min. Further 0.9 ml aliquots were taken to determine 86Rb uptake, and the fluxes plotted at the mid-point of their determination. The rate constants for bumetanide-resistant 86Rb uptake, determined in the control cells and 56 min after arsenite addition, were 0.08 ± 0.02 h−1 and 0.11 ± 0.00 h−1, respectively. Rate constants are shown with standard errors if these are larger than point size.

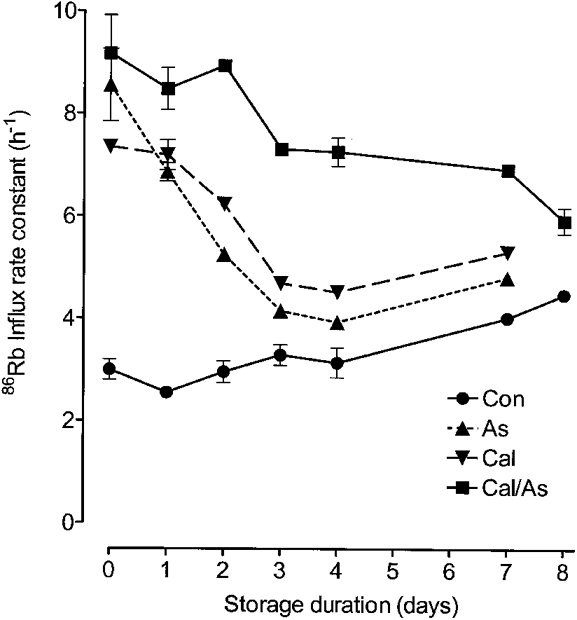

The amount of stimulation caused by arsenite was very dependent on the duration of cell storage. On the day of bleeding, arsenite caused the largest stimulation of cotransport by any single agent so far tested (rate constant about 3 times control), even exceeding that caused by 20 nM calyculin A (Fig. 2). On the following day, the extent of stimulation had fallen and was now similar to that caused by calyculin A. On subsequent days, arsenite caused less stimulation than calyculin, though the rate now approached that in the control, untreated group of cells. After 14 or more days of storage the addition of 1 mM arsenite caused a slight inhibition of cotransport compared with controls (rate constants, 2.17 ± 0.09 h−1vs. control values of 2.86 ± 0.04 h−1, n = 3, P = 0.02).

Figure 2. Effect of the duration of cell storage on responses to arsenite and calyculin.

This figure shows 86Rb uptake in erythrocytes taken from a single ferret and stored in FBM at 4 °C for the times indicated. Cells were washed and then added to FBM containing 11 mM glucose and incubated at 38 °C for 10 min (Con), for 60 min with 1 mM sodium arsenite (As), for 10 min with 20 nM calyculin (Cal), or for 60 min with arsenite followed by 10 min with calyculin (Cal/As), before 86Rb was added and influx measured. Rate constants are shown with standard errors if these are larger than point size.

When ferret erythrocytes are treated with calyculin A, 20 nM causes the maximal stimulation of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport possible with this agent (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). Similarly, increasing the arsenite concentration above 1 mM has only a small effect on the transport rate (Fig. 3). However, the addition of 20 nM calyculin A to cells treated with 1 mM arsenite, or arsenite to cells treated with calyculin, caused significant further stimulation of transport, and fluxes reached the highest levels seen. These levels were not affected by the order in which the compounds were added (e.g. after 10 min with calyculin followed by 1 h in arsenite, the influx rate constant was 9.17 ± 0.75 h−1; after 1 h in arsenite followed by 10 min in calyculin it was 9.66 ± 0.18 h−1; with calyculin alone it was 7.35 ± 0.12 h−1; and with arsenite alone it was 8.55 ± 0.71 h−1). Stimulation caused by the combined action of arsenite and calyculin also fell with time, but much more slowly than following treatment by either agent alone (Fig. 2). Stimulation of 86Rb uptake by the combination of calyculin and arsenite was due solely to activation of the cotransporter, as it had no effect on 86Rb uptake in the presence of 20 μM bumetanide (rate constant, 0.12 ± 0.01 h−1, n = 3).

Figure 3 shows the extent of stimulation caused by arsenite (60 min) as a function of arsenite concentration both in cells on the day of bleeding, and in cells from the same ferret stored for 4 days at 4°C. In fresh cells stimulation is large and occurs at low concentrations of arsenite. These data are well described (R2= 0.9557) by a model that assumes arsenite activates by binding to a high-affinity site (EC50, 85 μM). The data are also well described (R2= 0.9661) by a more complex model that assumes arsenite acts at two sites, one with a high affinity (EC50, 51 μM) and one with a low affinity (EC50 estimated to be about 17 mM in this experiment) for arsenite. After 4 days in storage, all the stimulation appeared to be due to arsenite acting at a low-affinity site (EC50, 3.5 mM; Fig. 3), and there was no evidence for a high-affinity effect. In three experiments using blood stored for 3 days or less, the EC50 for arsenite stimulation was 60 ± 14 μM assuming a single site of action, or 35 ± 9 μM for arsenite acting at the high-affinity site in the two site model. Unfortunately, it was not possible to obtain an accurate and reliable measure the EC50 for the low-affinity site as we could not increase the arsenite concentration to a high enough level without seriously altering the composition of the medium. However, all the data analysis indicates that it is greater than 2 mM. Our findings are consistent with two possible models. In one, arsenite acts at two sites (high and low affinity) in fresh cells, and the high-affinity site is lost as the cells age. In the other, arsenite binds with high affinity in fresh cells, and the affinity of this site falls as the cells get older.

Although our data suggest that p38 MAPK is probably not involved in the regulation of resting Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport activity, it still might mediate the stimulation of transport by arsenite. It has been shown recently that activation of the p38 MAPK pathway is a clear consequence of arsenite treatment in a variety of human cell lines (Ludwig et al. 1998). However, we found that treating cells for 10 min with 20 μM SB203580 before adding 1 mM arsenite had little effect on the stimulation of cotransport measured an hour later (rate constants: arsenite alone, 6.87 ± 0.05 h−1; with SB203580, 6.25 ± 0.01 h−1), probably ruling out a role for p38 MAPK in the response to arsenite in ferret erythrocytes. In the same experiment we found that 50 μM PD98059 did not prevent stimulation by arsenite (rate constant, 6.23 ± 0.26 h−1), perhaps also ruling out a role for p42/p44 MAPK.

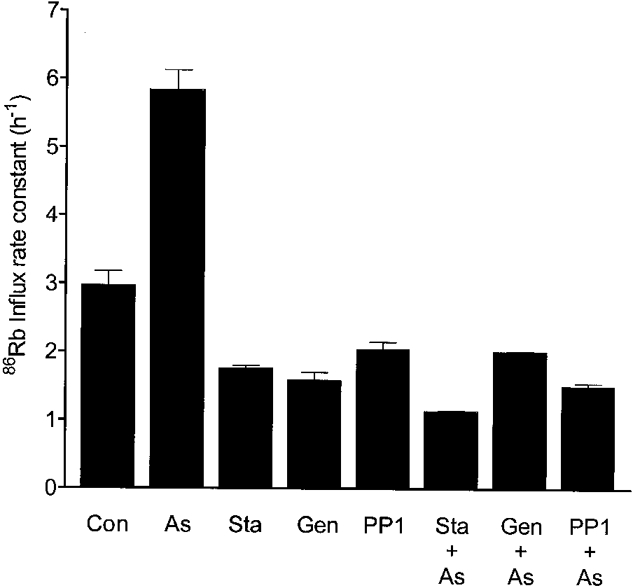

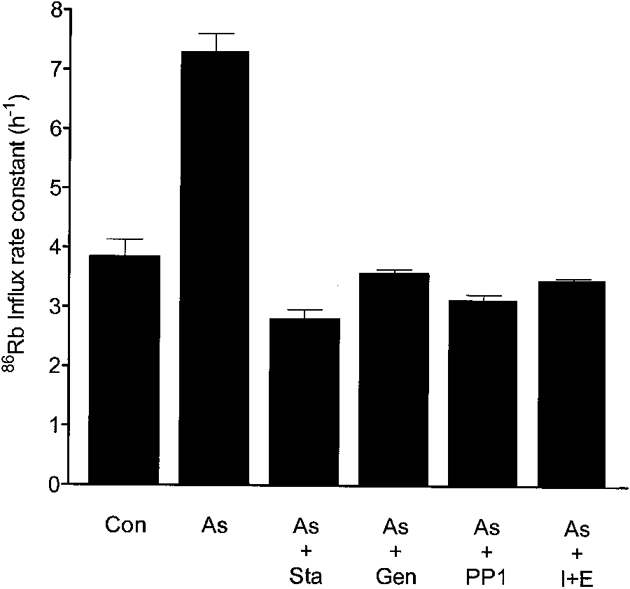

In order to explore whether cotransport stimulation by arsenite involves the same pathways responsible for the stimulation by calyculin A, we examined the effects of kinase inhibitors and Mg2+ depletion (A23187 + EDTA, see Methods) on the arsenite response (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). Figure 4 and Figure 5 show that treatment of erythrocytes for 15 min with 2 μM staurosporine, 50 μM PP1, 0.3 mM genistein or 10 μM A23187 with 2 mM EDTA prevented stimulation by 1 mM arsenite and also completely reversed the stimulation caused by arsenite. In a separate experiment we found that the treatment of cells with A23187 and EDTA prevented stimulation by arsenite. Addition of 1 mM arsenite increased the cotransport influx rate constant from 2.16 ± 0.03 to 8.63 ± 0.38 h−1 in cells with a normal Mg2+ concentration. However, after the cells had been treated with A23187 and EDTA, which caused the rate constant to fall to 1.66 ± 0.01 h−1, a further fall to 1.35 ± 0.05 h−1 occurred on addition of arsenite.

Figure 4. Prevention of arsenite stimulation by kinase inhibitors.

Cells (stored for 2 days) were incubated in FBM containing 11 mM glucose with no further additions (Con), or with 2 μM staurosporine (Sta), 0.3 mM genistein (Gen) or 50 μM PP1 for 15 min. 86Rb was added to an aliquot of each suspension to determine influx, and 1 mM sodium arsenite (As) was added to another. After incubation for a further hour, 86Rb was added to these arsenite-containing suspensions and the influx rate was determined. Bars represent the influx rate constants with standard errors.

Figure 5. Reversal of the arsenite effect by kinase inhibitors and Mg2+ removal.

Cells (stored for 1 day) were incubated in FBM containing 11 mM glucose for 15 min (Con) and in the same medium with the addition of 1 mM sodium arsenite for 60 min (As). 86Rb uptake rates were determined in aliquots of these suspensions. Staurosporine (2 μM; As + Sta), 0.3 mM genistein (As + Gen), 50 μM PP1 (As + PP1) or 10 μM of the ionophore A23187 together with 2 mM EDTA (As + I + E) were then added to aliquots of the arsenite-containing suspension and incubation continued for a further 15 min. 86Rb was added and the uptake rate determined. Bars represent the 86Rb influx rate constants with standard errors.

We have already seen that the combination of arsenite and calyculin produces the strongest stimulation of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport, and that this stimulation persists even in cells stored for long periods. This activation of cotransport was completely prevented by prior treatment of the cells with A23187 + EDTA (Fig. 6). In fact under these conditions a slight, but consistent, inhibition of transport was seen on addition of arsenite. Prior treatment of cells with 2 μM staurosporine or 0.3 mM genistein partially prevented the activation (activity was about 60 % of that seen in the presence of arsenite together with calyculin), whereas 50 μM PP1 had no significant effect (Fig. 6). When the treatments were performed after cotransport had been activated by the combination of calyculin with arsenite, neither PP1 nor A23187 + EDTA had any significant effect on the rate of transport, whereas both staurosporine and genistein caused a small degree of inhibition, the rate being reduced to 75–80 % maximal (Fig. 7).

Figure 6. Effects of kinase inhibitors and Mg2+ removal on 86Rb influx determined after the subsequent addition of arsenite and calyculin A.

Cells (stored for 3 days) were incubated in FBM containing 11 mM glucose with no further additions (Con), or with 2 μM staurosporine (Sta), 0.3 mM genistein (Gen), 50 μM PP1 (PP1), or 10 μM A23187 together with 2 mM EDTA (I + E) for 15 min. 86Rb was added to an aliquot of each suspension to determine influx, and 1 mM sodium arsenite together with 20 nM calyculin A (C/A) were added to another. After incubation for a further hour, 86Rb was added to those suspensions containing calyculin and arsenite, and influx rates were determined. Bars represent influx rate constants with standard errors.

Figure 7. Effects of kinase inhibitors and Mg2+ removal on 86Rb uptake stimulated by the combined effects of arsenite and calyculin A.

Cells (stored for 2 days) were incubated in FBM containing 11 mM glucose with no further additions (Con) or with 1 mM sodium arsenite and 20 nM calyculin A (C/As) for 1 h. 86Rb was added to an aliquot of these suspensions to determine uptake rate, and to other aliquots the following additions were made: 2 μM staurosporine (C/As + Sta), 0.3 mM genistein (C/As + Gen), 50 μM PP1 (C/As + PP1), or 10 μM A23187 together with 2 mM EDTA (C/As + I + E). These were incubated for a further 15 min before 86Rb was added to determine uptake. Bars represent influx rate constants with standard errors.

The possibility that arsenite may influence cotransporter function indirectly by altering the level of intracellular ATP was examined as follows. Freshly collected erythrocytes were incubated for 1 h in FBM and glucose, either alone or with the addition of 1 mM arsenite, or with 1 mM arsenite and 20 nM calyculin A. Initial and final cell ATP levels were measured. The ATP levels in the control cells rose steadily over the hour from an initial level of 0.72 ± 0.01 mmol loc−1 (n = 14) to 0.92 mmol loc−1. In cells treated with arsenite, ATP levels fell to 0.67 ± 0.03 mmol loc−1 (n = 6), whereas in cells treated with arsenite and calyculin there was little change in ATP levels to 0.70 ± 0.01 mmol loc−1 (n = 6). Although it is clear that arsenite alone, or in combination with calyculin, interferes with erythrocyte metabolism, the small changes in ATP level observed should not affect the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport rate (Flatman, 1991).

DISCUSSION

Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport is activated in many cells by osmotic shrinkage, growth factors and hypoxia (Haas, 1989, 1994; Haas & Forbush, 1998; Muzyamba et al. 1998). These same factors influence many cell functions through the activation of MAPKs and SAPKs (Brewster et al. 1993; Seko et al. 1997). We set out to examine the hypothesis that MAPKs and SAPKs were involved in the signal transduction pathway from receptors to the cotransporter and played a role in regulating the phosphorylation of the cotransporter that in turn regulates transport rate. Our work suggests that neither p38 MAPK nor p42/p44 MAPK are involved in regulating the cotransporter in ferret erythrocytes under our experimental conditions. While attempting to see whether SAPKs are involved in the signal pathway we treated cells with anisomycin and sodium arsenite, agents which non-specifically activate many MAPKs and SAPKs (Kyriakis et al. 1994; Cavigelli et al. 1996). However, we found that whereas anisomycin inhibited the cotransporter, arsenite caused the greatest stimulation of cotransport by any single agent yet tested, the rate of transport reaching levels in excess of those seen in the presence of saturating levels of calyculin A.

Stimulation by arsenite developed slowly after a lag period of 15–20 min. In fresh cells, and in cells stored for 3 days or less, arsenite stimulated transport by acting either at a single site (EC50, 60 μM), or at both high (EC50, 35 μM) and low (EC50 > 2 mM) affinity sites. Stimulation was greatest on the day of cell collection, and fell during cell storage. This may have been due either to a fall in the arsenite affinity of one site, or to the gradual disappearance of the high-affinity site.

A surprising finding, which offered an important clue to the mechanism of action of arsenite, was that the addition of calyculin A to cells already treated with arsenite (or vice versa) caused yet further stimulation of transport. This additive, or synergistic effect, which was clearest in cells stored for 4 days - a time by which arsenite or calyculin alone caused only minor stimulation of cotransport - suggests that calyculin A and arsenite act on different, complementary components in the signal transduction pathway in ferret erythrocytes. A possible model for these effects is given in Fig. 8. It has been established that calyculin A, either directly (Klein et al. 1993; Palfrey & Pewitt, 1993; Lytle, 1997) or indirectly (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b) inhibits phosphatase P1 which dephosphorylates the cotransporter. The actions of arsenite can be explained if it eventually stimulates kinase K1, the enzyme which phosphorylates the cotransporter. It is possible to set up this model so that transport is maximally stimulated in fresh cells, either by just stimulating the kinase K1 (with arsenite), or by just inhibiting the phosphatase P1 (with calyculin). Thus no additive effect will occur at this time. It is only when saturating levels of these agents cause less stimulation, as in stored cells, that an additive, or synergistic effect becomes apparent. Under these circumstances, maximal stimulation (phosphorylation) requires not only activation of the kinase, but also inhibition of the phosphatase. Changes in the sensitivity of cotransport to inhibitors may reflect a change in the activity of the kinases and phosphatases as cells age. Ultimately, the level of phosphorylated cotransporter determines the transport rate, and this level results from the balance of kinase and phosphatase activities. A similar balance may be achieved with very different absolute rates of kinase and phosphatase activity, and with the enzymes having different capacities for changes in activity. In previous studies on Na+-K+-2Cl−1 cotransport, calyculin alone was found to produce maximal stimulation, and its effects were not additive with any other stimulants (cyclic AMP, fluoride, cell shrinkage) (Palfrey & Pewitt, 1993; Lytle, 1997).

We further explored arsenite's mechanism of action by inhibiting kinases in the signal transduction pathways of the cotransporter with staurosporine, PP1 or genistein (this may also directly inhibit the cotransporter; Flatman & Creanor (1999b)), or by reducing [Mg2+]i to micromolar levels by treating the cells with A23187 and EDTA. All these treatments prevented and reversed the stimulation of transport caused by 1 mM arsenite. Previously, we have shown that these treatments also prevent stimulation by calyculin, but only partially reverse stimulation once established with calyculin (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). These results again suggest that arsenite and calyculin stimulate cotransport by different mechanisms. The simplest explanation of these effects, which is also consistent with the effects of arsenite and calyculin being additive, is that arsenite activates kinase K1 (Fig. 8), as suggested above. Staurosporine, PP1, Mg2+ removal and possibly genistein all stimulate phosphatase P1 by inhibiting an inhibitory kinase (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b) (Fig. 8). Activation of the phosphatase outweighs any stimulation of kinase K1 by arsenite, and this not only prevents cotransport stimulation by arsenite but also reverses any stimulation already established by arsenite.

As predicted by the model shown in Fig. 8, treatment of cells with A23187 and EDTA prevented stimulation by the combination of arsenite with calyculin (Fig. 6), but did not affect the stimulated transport rate, once this had been established (Fig. 7). The model also successfully accounts for the effects of staurosporine and PP1. These completely prevented stimulation by arsenite alone (Fig. 4) and reduced stimulation by calyculin alone by more than 90 %, with staurosporine being the more potent (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). However, pretreatment with PP1 did not significantly reduce stimulation by the combination of arsenite with calyculin and stimulation was still about 60 % of maximal after treatment with staurosporine (Fig. 6). This again demonstrates the synergy between arsenite and calyculin, the residual stimulation caused by calyculin in the presence of staurosporine or PP1 being amplified by arsenite acting on a different step in the signal transduction pathway. As predicted by the model, PP1 had no significant effect on transport once it had been stimulated by the combination of arsenite and calyculin, while staurosporine caused a small amount of inhibition (about 20 %), possibly because it acts on several steps in the signal transduction pathway (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). The results further suggest that PP1 is a much more specific inhibitor of the regulatory pathway controlling phosphatase P1. The actions of genistein may be similar to those of PP1 and staurosporine, though our previous work has shown that it may also directly inhibit the cotransporter (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). Such an effect is consistent with the results reported here both with arsenite, and with the combination of arsenite and calyculin, where genistein reduced the cotransport rate by about 30–50 % under all conditions. This would be expected if the EC50 for genistein is above 0.3 mM, as reported previously (Flatman & Creanor, 1999b).

The model shown in Fig. 8 assumes that arsenite stimulates cotransport by acting through a single final common pathway - the activation of kinase K1. This idea is supported by the observed interactions between arsenite, calyculin and the kinase inhibitors. If arsenite had a major effect on phosphatase P1 this would have been apparent in experiments where arsenite was used in combination with the kinase inhibitors (compare the actions of these same inhibitors in conjunction with calyculin; Flatman & Creanor, 1999b). The stimulation of K1 by arsenite could be due a single action on the pathway (the single-site model) or to multiple actions (e.g. the two-site model).

The molecular basis for the stimulation of cotransport by arsenite is not clear from our work. The fact that Mg2+ depletion both prevented and reversed stimulation by arsenite supports the notion that arsenite stimulates kinase K1 (Fig. 8). This could be a direct or indirect effect, though the slowness of stimulation perhaps favours an indirect effect. Arsenite is a sulfhydryl reagent that reacts with thiol groups on proteins (Snow, 1992; Cavigelli et al. 1996), and this interaction is strongest where several thiol groups are close to each other. There is evidence that arsenite may interact with the thiol groups at the active centre of phosphotyrosine phosphatases and inhibit activity (Cavigelli et al. 1996). Such phosphatases may be involved in the regulation of kinase K1 (Fig. 8). Involvement of p38 and p42/p44 MAPKs in the response to arsenite seems unlikely as neither SB203580 nor PD98059 affect the stimulation of transport caused by arsenite. The observation that arsenite stimulated cotransport whereas anisomycin inhibited it leaves doubts about the involvement, or role, of SAPKs in regulating the cotransporter. The findings suggest that caution must be exercised when interpreting experiments where these compounds have been used to stimulate SAPKs.

An interesting possibility is that arsenite may reduce the levels of intracellular glutathione by inhibiting glutathione reductase (Snow, 1992), and this in turn may affect the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport rate. A reduction in the level of a key cytoplasmic metabolite like glutathione may provide an explanation for the unusual time course of the stimulation caused by arsenite (Fig. 1). If glutathione protects against the actions of arsenite, as has been suggested (Cavigelli et al. 1996), then stimulation of cotransport will be delayed until the glutathione levels have fallen sufficiently. An additional possibility is that changes in glutathione levels directly affect the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport rate. Although this has yet to be investigated, effects of glutathione on the related K+-Cl− cotransporter are well documented (Lauf et al. 1995).

Finally, our work also suggests that arsenite may have other sites of action in the regulatory pathways which control the cotransporter. In cells stored for long periods, or treated with A23187 and EDTA, arsenite consistently caused a small inhibition of transport.

Our findings suggest that arsenite may prove a useful tool in further investigations into cotransporter regulation. In addition, they may have physiological significance. Many water supplies in the world contain levels of naturally occurring or pollutant arsenic (> 10 μM), often as arsenite ions (Snow, 1992; Nickson et al. 1998), that are high enough to affect the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport rate, and presumably as a consequence, body fluid regulation. This may help explain some of the deleterious effects of ingesting even low levels of this ion.

Acknowledgments

We should like to thank The Wellcome Trust for supporting this project and Dr Hal B. F. Dixon for discussions that kindled an interest in the biological effects of arsenic.

References

- Alper SL, Beam KG, Greengard P. Hormonal control of Na+-K+ co-transport in turkey erythrocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1980;255:4864–4871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigan DL, Shriner CL. Methods to distinguish various types of protein phosphatase activity. Methods in Enzymology. 1988;159:339–346. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)59034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster JL, De Valoir T, Dwyer ND, Winter E, Gustin MC. An osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. Science. 1993;259:1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.7681220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Pouysségur J. Mammalian MAP kinase modules: how to transduce specific signals. Essays in Biochemistry. 1997;32:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavigelli M, Li WW, Lin A, Su B, Yoshioka K, Karin M. The tumor promoter arsenite stimulates AP-1 activity by inhibiting a JNK phosphatase. EMBO Journal. 1996;15:6269–6279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea L, Lytle C, Matthews JB, Hofman P, Forbush B, III, Madara JL. Na:K:2Cl cotransporter (NKCC) of intestinal epithelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:28969–28976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatman PW. The effects of magnesium on potassium transport in ferret red cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;397:471–487. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatman PW. The effects of metabolism on Na+-K+-Cl− cotransport in ferret red cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;437:495–510. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatman PW, Creanor J. Na+ arsenite: a potent stimulant of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport in ferret red cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1999a. in the Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Flatman PW, Creanor J. Regulation of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport by protein phosphorylation in ferret erythrocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1999b;517:699–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0699s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M. Properties and diversity of (Na-K-Cl) cotransporters. Annual Review of Physiology. 1989;51:443–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M. The Na-K-Cl cotransporters. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:C869–885. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.4.C869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M, Forbush B., III The Na-K-Cl cotransporters. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 1998;30:161–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1020521308985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JD, O'Neill WC. Volume-sensitive myosin phosphorylation in vascular endothelial cells: correlation with Na-K-2Cl cotransport. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:C1524–1531. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.6.C1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JD, Perry PB, O'Neill WC. Regulation by cell volume of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport in vascular endothelial cells: role of protein phosphorylation. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1993;132:243–252. doi: 10.1007/BF00235741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krarup T, Jakobsen LD, Jensen BS, Hoffmann EK. Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport in Ehrlich cells: regulation by protein phosphatases and kinases. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:C239–250. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.1.C239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis JM, Banerjee P, Nikolakaki E, Dai T, Rubie EA, Ahmad MF, Avruch J, Woodgett JR. The stress-activated protein kinase subfamily of c-Jun kinases. Nature. 1994;369:156–160. doi: 10.1038/369156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauf PK, Adragna NC, Agar NS. Glutathione removal reveals kinases as common targets for K-Cl cotransport stimulation in sheep erythrocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:C234–241. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.1.C234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig S, Hoffmeyer A, Goebeler M, Kilian K, Häfner H, Neufeld B, Han J, Rapp UR. The stress inducer arsenite activates mitogen-activated protein kinases extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 via a MAPK kinase 6/p38-dependent pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:1917–1922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle C. Activation of the avian erythrocyte Na-K-Cl cotransport protein by cell shrinkage, cAMP, fluoride, and calyculin-A involves phosphorylation at common sites. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:15069–15077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle C, Forbush B., III The Na-K-Cl cotransport protein of shark rectal gland. II. Regulation by direct phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:25438–25443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JB, Smith JA, Mun EC, Sicklick JK. Osmotic regulation of intestinal epithelial Na+-K+-Cl− cotransport: role of Cl− and F-actin. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C697–706. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.3.C697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JB, Smith JA, Tally KJ, Awtrey CS, Nguyen H, Rich J, Madara JL. Na-K-2Cl cotransport in intestinal epithelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:15703–15709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mildvan AS. Role of magnesium and other divalent cations in ATP-utilizing enzymes. Magnesium. 1987;6:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzyamba MC, Cossins AR, Gibson JS. Response of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter in turkey red cells to physiological stimuli: effect of ‘phosphorylation clamping’. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;513.P:56–57. P. [Google Scholar]

- Nickson R, McArthur J, Burgess W, Ahmed KM, Ravenscroft P, Rahman M. Arsenic poisoning of Bangladesh groundwater. Nature. 1998;395:338. doi: 10.1038/26387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Grady SM, Palfrey HC, Field M. Characteristics and functions of Na-K-Cl cotransport in epithelial tissues. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:C177–192. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.2.C177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfrey HC, Pewitt EB. The ATP and Mg2+ dependence of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport reflects a requirement for protein phosphorylation: studies using calyculin A. Pflügers Archiv. 1993;425:321–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00374182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pewitt EB, Hegde RS, Haas M, Palfrey HC. The regulation of Na/K/2Cl cotransport and bumetanide binding in avian erythrocytes by protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Effects of kinase inhibitors and okadaic acid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:20747–20756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seko Y, Takahashi N, Tobe K, Kadowaki T, Yazaki Y. Hypoxia and hypoxia/reoxygenation activate p65PAK, p38mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) in cultured rat cardiac myocytes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;239:840–844. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow ET. Metal carcinogenesis: mechanistic implications. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1992;53:31–65. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90043-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura A, Kurihara K, Reshkin SJ, Turner RJ. Involvement of direct phosphorylation in the regulation of the rat parotid Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:25252–25258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winski SL, Carter DE. Arsenate toxicity in human erythrocytes: characterization of morphologic changes and determination of the mechanism of damage. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 1998;53:345–355. doi: 10.1080/009841098159213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]