Abstract

In this study we investigated the role of basolateral potassium transport in maintaining cAMP-activated chloride secretion in human colonic epithelium.

Ion transport was quantified in isolated human colonic epithelium using the short-circuit current technique. Basolateral potassium transport was studied using nystatin permeabilization. Intracellular calcium measurements were obtained from isolated human colonic crypts using fura-2 spectrofluorescence imaging.

In intact isolated colonic strips, forskolin and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) activated an inward transmembrane current (ISC) consistent with anion secretion (for forskolin ΔISC = 63.8 ± 6.2 μA cm−2, n = 6; for PGE2 ΔISC = 34.3 ± 5.2 μA cm−2, n = 6). This current was inhibited in chloride-free Krebs solution or by inhibiting basolateral chloride uptake with bumetanide and 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS).

The forskolin- and PGE2-induced chloride secretion was inhibited by basolateral exposure to barium (5 mM), tetrapentylammonium (10 μM) and tetraethylammonium (10 mM).

The transepithelial current produced under an apical to serosal K+ gradient in nystatin-perforated colon is generated at the basolateral membrane by K+ transport. Forskolin failed to activate this current under conditions of high or low calcium and failed to increase the levels of intracellular calcium in isolated crypts

In conclusion, we propose that potassium recycling through basolateral K+ channels is essential for cAMP-activated chloride secretion.

The key event in colonic fluid secretion is the electrogenic transport of chloride ions, with sodium and water following by passive diffusion. It has been shown in the immortalized intestinal-derived cell line T-84 and in dogfish rectal gland (Greger & Schlatter, 1984; Halm et al. 1988; Dharmsathaphorn et al. 1988) that during chloride secretion chloride ions enter the secreting cells via the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and leave the luminal surface through apical chloride channels. This results in an accumulation of K+ by the secreting cell. Basolateral K+ channels therefore play an important role in maintaining the driving force for chloride secretion.

A number of K+ channels have been identified on the basolateral membrane of mammalian colon. In rat colon there appear to be at least four distinct K+ channels: a < 3 pS cAMP-activated channel (Greger et al. 1997a), a 16 pS Ca2+-activated channel (Burckhardt & Goegelein, 1992), a maxi-K channel (Burckhardt & Goegelein, 1992) and a non-selective cation channel (Siemer & Goegelein, 1992). In rabbit colon the predominant basolateral K+ channel is a calcium-activated maxi-K channel (Klaerke, 1997). In T-84 cells at least two K+ channels have been identified on the basolateral membrane; these are an inwardly rectifying Ca2+-activated channel (Tachbarani et al. 1994) and a large conductance Ca2+-independent channel (Devor & Frizzell, 1998). We have identified two pharmacologically distinct potassium conductances in the basolateral membrane of human colonic epithelial cells, ATP-regulated potassium channels (KATP) and calcium-activated potassium channels (KCa) (Maguire et al. 1994). Both channels are sensitive to the non-specific potassium channel blocker barium. KATP channels are activated by increasing intracellular pH and inhibited by the sulphonylurea tolbutamide. KCa channels are activated by cytosolic calcium and inhibited by quaternary ammonium cations such as tetrapentylammonium (TPeA) and tetra-ethylammonium (TEA).

Electrogenic chloride secretion in colonic cells may be activated by either of two second messenger systems. Secretagogues such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and forskolin activate secretion through cAMP, while agonists such as histamine, bradykinin, acetylcholine and carbachol act by increasing intracellular calcium (Bridges et al. 1983; Diener et al. 1988; Pickles & Cuthbert, 1991). In rat colon the inter-relationship between apical chloride conductance, basolateral K+ conductance and intracellular Ca2+ during chloride secretion is well understood. During carbachol- and acetylcholine-activated chloride secretion a 16 pS Ca2+-dependent K+ channel is activated (Nielsen et al. 1998). In contrast, during cAMP-mediated chloride secretion, cAMP directly activates apical chloride secretion; in addition there is a parallel activation of small conductance basolateral K+ channels (Greger et al. 1997b), and this is accompanied by inhibition of the Ca2+-dependent channel. However, there are significant interspecies differences in colonic ion transport mechanisms (Binder & Sandle, 1994). It is therefore particularly important to describe the exact ionic transport mechanisms that occur in human colon. In intact native human colonic epithelium the relationship between chloride secretion, basolateral K+ transport and intracellular Ca2+ during cAMP-activated chloride secretion has not been well described. In this study we have investigated which of the K+ channel types are involved in cAMP-mediated chloride secretion in the human distal colon and the effects of cAMP and raised intracellular calcium levels on basolateral K+ transport.

METHODS

Source and preparation of colonic mucosa

Non-diseased samples of human distal colon from patients undergoing resection for carcinoma were used. The use of human tissue in these experiments was approved by the Cork University Teaching Hospitals' Ethics Committee, and experiments were performed with patients' full consent and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The sample was transported to the laboratory in 0.9 % saline within 30 min of surgery.

The epithelial layer was separated from underlying smooth muscle and connective tissue by blunt dissection. Sheets of this tissue (0.5 cm2) were mounted in modified Perspex Ussing chambers (ADInstruments UK Ltd). Experiments on chloride secretion in intact cells were performed in Krebs solution of the following ionic composition (mM): NaCl, 118; NaHCO3, 25; glucose, 11; KCl, 4.7; CaCl2, 2.5; MgSO4, 1.2; and KH2PO4, 1.2. The solution was equilibrated in 5 % CO2 in oxygen, pH 7.4. The bath temperature was maintained at 37°C using a heated water jacket.

Electrophysiological techniques

The spontaneous transmembrane potential was measured using an EVC 4000 Amplifier (WPI). The potential was clamped to 0 mV by the application of a short-circuit current (ISC), which is a measure of electrogenic ion transport (Koefoed-Johnsen & Ussing, 1958). Transepithelial resistance (Rt) was calculated by measuring the current response to a 5 mV pulse. The current signal was digitized using an MP100 analog-digital converter (Biopac Systems Inc., USA) and analysed using Acqknowledge version 3.0 software (Biopac Systems Inc., USA) on an Apple Macintosh Quadra 650 personal computer. All drugs and chemicals were obtained from Sigma.

Studies with K+ channel blockers

In nystatin permeabilization experiments the basolateral membrane was bathed in a low chloride Krebs solution of the following ionic composition (mM): sodium gluconate, 100; NaCl, 20; NaHCO3, 25; glucose, 11; KCl, 4.7; CaCl2, 2.5; MgSO4, 1.2; and KH2PO4, 1.2. pH was maintained at 7.4 by gassing with 95 % O2-5 % CO2. The apical membrane was bathed in potassium-rich solution of the following ionic composition (mM): potassium gluconate, 120; NaCl, 20; MgSO4, 3; KH2PO4, 1.2; glucose, 11; EDTA, 5; and Hepes, 6. CaCl2 was added to give a final free calcium concentration of 10 nM, 50 nM, 100 nM or 1 μM at 37°C and pH 7.2; the amount of CaCl2 to be added was calculated using a computer program (Chang et al. 1988), and pH was adjusted to 7.2 by the addition of KOH. Electrogenic Na+ transport was abolished by treatment of the apical membrane with amiloride (100 μM). The use of symmetrical low chloride solutions was found to be necessary to avoid cell volume changes.

The apical membrane was treated with the polyene antibiotic nystatin (500 i.u. ml−1 in < 0.01 % methanol) and the transepithelial current allowed to reach a steady state. Nystatin forms cation-permeable pores in the apical membrane, and isolates the basolateral membrane electrically (Lewis et al. 1977). Under the conditions of a mucosa to serosa K+ gradient, the transepithelial current is generated by the K+ conductance of the basolateral membrane and K+ transport across the paracellular pathway. Transport across the paracellular pathway is insensitive to K+ channel blockers. In our nystatin experiments the current remaining after K+ channel inhibition accounted for < 10 % of the total.

Statistical methods

All values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Student's t test was used to determine statistical significance. We used half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) as a summary statistic to compare the concentration-inhibition characteristics of the K+ channel blockers used in these experiments. IC50 was calculated by fitting concentration and response values to the following equation, which is analogous to the Michaelis-Menten equation. This was done using a commercially available computer program (SPSS for windows, SPSS Inc. UK).

| (1) |

where ΔI is the inhibition of ISC or IK at a given concentration of drug, and ΔImax is the maximum inhibition of IK or ISC produced by the drug.

Intracellular calcium measurements

Human colonic epithelium is a complex tissue. It is therefore difficult to precisely measure intracellular calcium in individual cells and to extrapolate these results to the conditions that apply in Ussing chamber experiments. To make qualitative measurements of the changes in intracellular calcium levels that occur during cAMP-mediated chloride secretion we measured intracellular Ca2+ in intact colonic crypts using the following techniques. Intact human crypts were isolated by exposing mucosal segments, microdissected from resected segments, to a calcium chelation solution (composition (mM): NaCl, 96; KCl, 1.5; Hepes-Tris, 10; NaEDTA, 27; sorbitol, 45; and sucrose, 28) for 30 min at room temperature. A pellet of isolated crypts was formed by centrifugation at 2000 g for 1 min and was resuspended in Krebs solution. Freshly isolated crypts were exposed to 5 μM fura-2 AM at room temperature for 60 min. They were then rinsed twice and stored in the dark in fresh Krebs solution on ice.

Crypts were transferred to glass coverslips treated with poly-L-lysine and were mounted on an inverted epi-fluorescence microscope (Diaphot 200, Nikon). The light from a xenon lamp (Nikon) was filtered through alternating 340 and 380 nm interference filters (10 nm bandwidth, Nikon). The emitted fluorescence was passed through a 400 nm dichroic mirror, filtered at 510 nm and then collected using an intensified CCD camera system (Darkstar, Photonic Science). Images were digitized and analysed using the Starwise Fluo system (Imstar, Paris). The system was calibrated in vitro and the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration was calculated using the equation of Grynkiewicz et al. (1985). We determined the changes in intracellular calcium levels in response to varying extracellular [Ca2+] in the presence of nystatin (500 i.u. ml−1 in < 0.01 % methanol). The nystatin pore has a low but finite permeability to Ca2+, and changes in extracellular Ca2+ over the range 10 nM to 100 μM produce a sustained increase in cytosolic [Ca2+] from 50 to 800 nM. In the presence of nystatin, the intracellular Ca2+ level at the following [Ca2+]o was found to be as follows: at an [Ca2+]o of 10 nM, 50 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM, 10 μM and 100 μM, the corresponding [Ca2+]i was 47 ± 11, 110 ± 19, 225 ± 31, 295 ± 51, 385 ± 51 and 515 ± 126 nM (n = 18), respectively.

RESULTS

Basolateral chloride transport involved in forskolin-induced chloride secretion

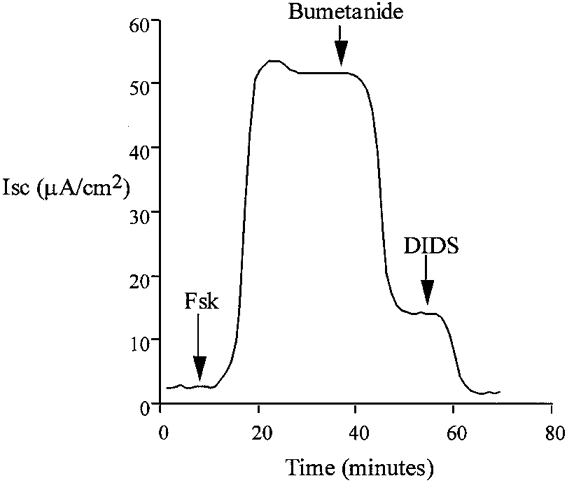

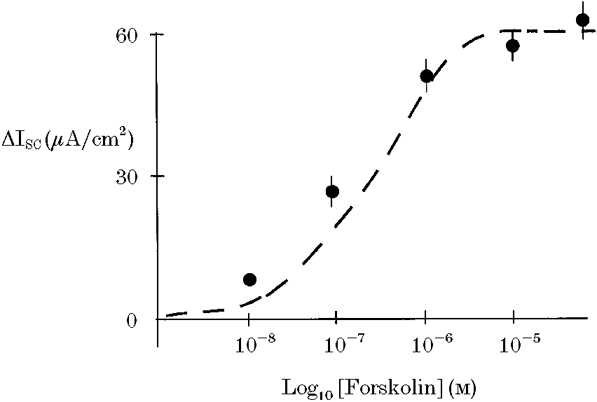

Addition of forskolin to the basolateral membrane produced an immediate and sustained increase in short-circuit current (ISC) consistent with anion secretion (Fig. 1). This effect was concentration dependent with maximal stimulation of current occurring at a forskolin concentration of 15 μM (basal ISC = 2.1 ± 0.3 μA cm−2, +forskolin ISC = 65.9 ± 5.8 μA cm−2, corresponding to a mean increase in current (ΔISC) of 63.8 ± 6.2 μA cm−2, n = 6). The concentration- response characteristics for the forskolin response are shown in Fig. 2. This was associated with a fall in transepithelial resistance (control Rt = 312 ± 16 Ω cm2, forskolin Rt = 276 ± 10 Ω cm2, n = 6, P < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Addition of forskolin (Fsk) to the basolateral side of isolated colon epithelium resulted in an immediate increase in transepithelial short-circuit current, ISC, consistent with anion secretion. This representative trace shows that secretion was inhibited by blockade of basolateral Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport with bumetanide (100 μM) and Cl−-HCO3− exchange with DIDS (100 μM). Replacement of basolateral Cl− with gluconate also prevented this response.

Figure 2. Concentration-response relationship for the effect of forskolin on ISC.

Maximal response to forskolin was obtained at a concentration of 10 μM. Dashed lines show the best-fit curve for an equation analagous to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

Exposure of the colonic epithelium to a low chloride Krebs solution on both sides (NaCl replaced by sodium gluconate) prevented activation of current by forskolin (basal ISC = 1.7 ± 0.8 μA cm−2, +forskolin ISC = 3.2 ± 0.9 μA cm−2, ΔISC = 1.4 ± 0.4 μA cm−2, n = 6). These results indicate that the forskolin-activated current is carried by chloride ions. Treatment of the basolateral membrane with bumetanide (100 μM), a known inhibitor of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport, produced an immediate inhibition of ISC (Fig. 1) (forskolin ISC = 62.2 ± 4.9 μA cm−2, forskolin + bumetanide ISC = 20.4 ± 3.8 μA cm−2, bumetanide-inhibited current (ΔISC) = 41.8 ± 3.2 μA cm−2, n = 6). The remaining current was sensitive to the stilbene derivative 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS), a known inhibitor of Cl−-HCO3− exchange (forskolin + bumetanide ISC = 20.2 ± 3.6 μA cm−2, forskolin + bumetanide + DIDS ISC = 1.3 ± 0.6 μA cm−2, DIDS-sensitive current (ΔISC) = 18.9 ± 2.8 μA cm−2, n = 6). In our experiments we found a small and variable amount of amiloride-sensitive current under basal conditions (basal ISC = 4.9 ± 2.2 μA cm−2, +amiloride ISC = 2.7 ± 0.4 μA cm−2, ΔISC = 2.2 ± 0.8 μA cm−2, n = 6). We did not detect any change in amiloride-sensitive current following forskolin treatment (forskolin ISC = 64.9 ± 4.1 μA cm−2, +amiloride ISC = 62.4 ± 5.4 μA cm−2, ΔISC = 2.5 ± 1.3 μA cm−2, n = 6, P = 0.39). Because of the small amount of amiloride-sensitive current it is not possible to base any definite conclusions on these amiloride data.

DIDS partially inhibits Cl− channels. To confirm the role of HCO3− exchange we performed similar experiments in the nominal absence of CO2/HCO3−. When experiments were performed in the nominal absence of CO2/HCO3− (Hepes-buffered Krebs solution, pH 7.4, gassed with 100 % oxygen), the current response to forskolin was blunted (basal ISC = 1.9 ± 0.6 μA cm−2, +forskolin in Hepes buffer ISC = 44.1 ± 4.2 μA cm−2, ΔISC = 42.2 ± 3.9 μA cm−2, n = 6, significantly different from response in CO2/HCO3− buffer, P < 0.001). Under Hepes buffer conditions, the forskolin-activated current was almost completely inhibited by bumetanide (forskolin + Hepes ISC = 41.6 ± 3.7 μA cm−2, forskolin + Hepes + bumetanide ISC = 2.5 ± 0.6 μA cm−2, bumetanide-inhibited current (ΔISC) = 39.1 ± 2.5 μA cm−2, n = 6) and DIDS had little inhibitory influence (forskolin + bumetanide ISC = 2.6 ± 0.4 μA cm−2, forskolin + bumetanide + DIDS ISC = 1.4 ± 0.3 μA cm−2, ΔISC = 1.2 ± 0.2 μA cm−2, n = 6). These results indicate that the cAMP-mediated chloride secretion is dependent on both Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport and Cl−-HCO3− exchange. They imply that approximately two-thirds of chloride secretion in human colon is mediated by Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport.

Basolateral potassium transport involved in forskolin-induced chloride secretion

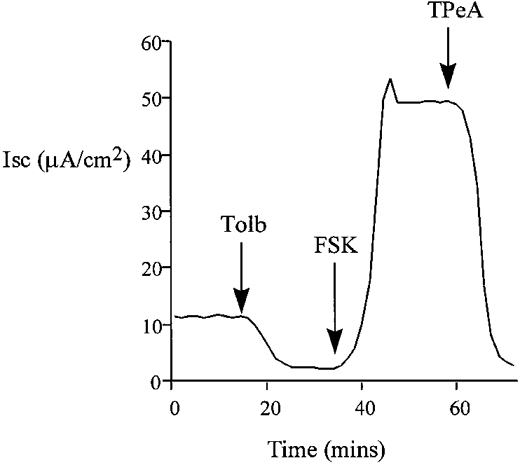

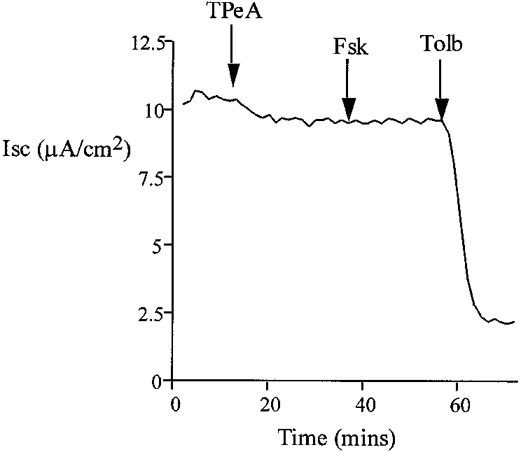

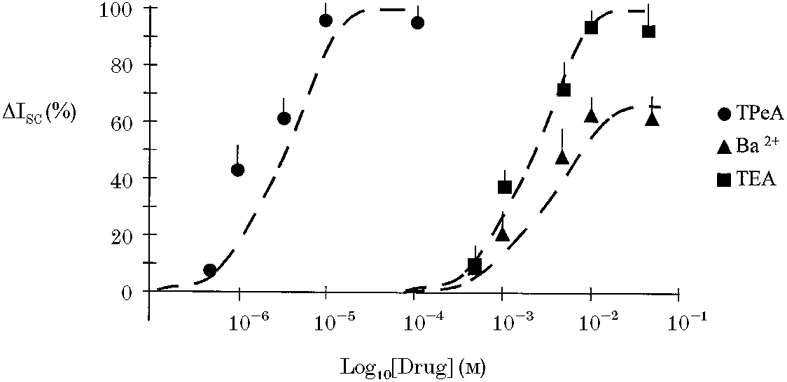

The effects of K+ channel blockers on the forskolin-induced chloride secretion were determined in intact isolated colon. Sulphonylureas inhibit ATP-regulated K+ channels (Ashcroft & Ashcroft, 1990) and quaternary ammonium ions are effective blockers of calcium-activated K+ channels (Villarroel et al. 1988). The possible involvement of these classes of K+ channels in the secretory response was tested using tolbutamide and tetrapentylammonium (TPeA), respectively. We selected a high dose of tolbutamide, 100 μM, to ensure we had maximally inhibited KATP channels. Pre-treatment of the basolateral side of the colonic epithelium with tolbutamide resulted in a reduction in the steady-state ISC from 12.7 ± 0.9 to 2.1 ± 0.4 μA cm−2(n = 6), but did not prevent the chloride secretory response to forskolin (ΔISC = 61 ± 2.4 μA cm−2 compared with control ΔISC = 58.4 ± 3.1 μA cm−2, n = 6, P = 0.27). A representative experiment is shown in Fig. 3. Subsequent basolateral addition of TPeA (10 μM) during the peak forskolin response caused a rapid reduction in ISC from 62.9 ± 3.2 to 2.7 ± 0.8 μA cm−2 (n = 6) (Fig. 3). At the high concentration of tolbutamide used, other classes of potassium channel may have been inhibited. However, since at this concentration of tolbutamide most KATP channels would be inactive, these results indicate a minor role for sulphonylurea-sensitive K+ channels in the secretory response. The complete inhibition of the forskolin-induced chloride secretion using TPeA indicates an absolute requirement for activation of a basolateral calcium-dependent K+ channel to sustain the secretory response. This hypothesis was further tested by pre-treating the epithelium with TPeA prior to forskolin addition (Fig. 4). Pre-treatment with TPeA (10 μM) did not change the steady-state short-circuit current (control ISC = 11.9 ± 1.8 μA cm−2, +TPeA ISC = 11.7 ± 0.9 μA cm−2, n = 6). However, the normal chloride secretory response to forskolin was completely prevented by TPeA (TPeA + forskolin ISC = 11.4 ± 0.8 μA cm−2, n = 6). The forskolin effect on chloride secretion was sensitive to another quaternary ammonium ion, tetraethylammonium (TEA) and to Ba2+, a general K+ channel blocker. The concentration dependence for these K+ channel blockers is shown in comparison with TPeA in Fig. 5. Half-maximal inhibition (IC50) for TPeA was obtained at 5.1 μM (n = 6), with 10 μM TPeA producing a maximum inhibition of chloride secretion. TEA and Ba2+ were less potent inhibitors of chloride secretion with IC50 values of 4.3 (n = 6) and 5.6 mM (n = 6), respectively.

Figure 3.

Pre-treatment with tolbutamide (Tolb, 100 μM) decreased baseline ISC but did not reduce the forskolin-induced chloride secretion in isolated colon. The forskolin-induced transepithelial current was TPeA (10 μM) sensitive (n = 6).

Figure 4.

Pre-treatment with TPeA (10 μM) did not affect baseline current, and subsequent addition of basolateral forskolin (20 μM) failed to increase ISC. The remaining current was sensitive to tolbutamide (100 μM) (n = 6).

Figure 5. Concentration-inhibition characteristics for TPeA, TEA and Ba2+ effects on forskolin-activated Cl− secretion.

Responses are shown as means + s.e.m. (n = 6). The forskolin-activated ISC was almost completely inhibited by TPeA at a concentration of 10 μM and by TEA at a concentration of 10 mM. Ba2+ produced maximal inhibition at 10 mM. •, TPeA; ▪, TEA; ▴, Ba2+. Best fit for an equation analagous to the Michaelis-Menten equation shown with dashed line.

Effect of prostaglandin E2

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is a secretagogue known to act by increasing intracellular cAMP levels. Addition of PGE2 (10 μM) to the basolateral membrane of this preparation produced a rapid and sustained increase in ISC consistent with chloride secretion. This ISC was inhibited by bumetanide and DIDS (basal ISC = 9.3 ± 1.8 μA cm−2, PGE2ISC 43.6 ± 6.1 μA cm−2, PGE2 + bumetanide ISC = 17.4 ± 4.1 μA cm−2, PGE2 + bumetanide + DIDS ISC = 4.2 ± 1.1 μA cm−2, n = 6). The PGE2-activated current showed similar sensitivity to the forskolin-activated current to treatment of the basolateral membrane with potassium channel blockers (PGE2ISC = 39.3 ± 5.8 μA cm−2, PGE2 + 100 μM tolbutamide ISC = 38.6 ± 6.1 μA cm−2, PGE2 + 100 μM tolbutamide + 10 μM TPeA ISC = 5.4 ± 4.1 μA cm−2).

Basolateral K+ transport in the nystatin-perforated colon

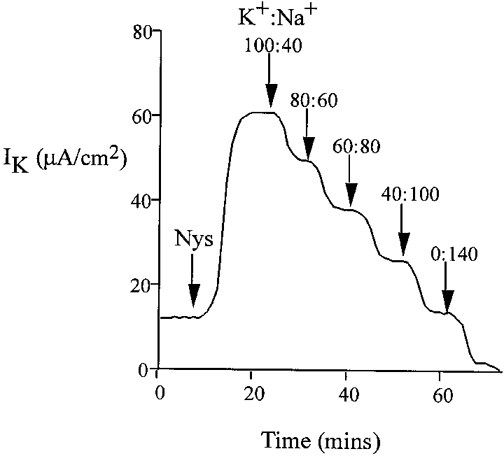

We investigated basolateral K+ transport using nystatin perforation of the apical membrane. Treatment of the apical membrane of mammalian colonic epithelium with nystatin has previously been shown to remove the electromotive force and resistance generated by the apical membrane. This allows investigation of the basolateral membrane in isolation (Wills et al. 1979). In the presence of high mucosal [K+] and low [Ca2+] (10 nM), the addition of nystatin produced an immediate increase in transepithelial current (from 22.3 ± 0.8 to 51.0 ± 1.2 μA cm−2, corresponding to a mean increase in current (ΔIt) = 28.7 ± 1.1 μA cm−2, n = 40), with membrane potential clamped to 0 mV. This was associated with a fall in transepithelial resistance (control Rt = 326 ± 9 Ω cm2, forskolin Rt = 166 ± 12 Ω cm2, n = 40, P < 0.01). The K+ dependence of this current was tested by graded replacement of all potassium salts with sodium salts in the apical bath (Fig. 6). The nystatin-induced current was abolished following total replacement of apical K+ by Na+ and a linear correlation (r = 0.89, P < 0.01) with zero intercept was found for the relationship between transepithelial current and apical [K+] over the range 0–120 mM. Therefore, the nystatin-induced transepithelial current reflects channel-mediated K+ flow (K+ channel activity) across the basolateral membrane and is hereafter referred to as trans-basolateral K+ current (IK). Further proof for this conclusion was obtained from the effects of K+ channel inhibitors on the nystatin-induced current. There was a small transepithelial HCO3− gradient generated by the solutions used for our nystatin method. This did not result in a significant diffusion potential (the HCO3− gradient was maintained during the sodium substitution protocol; when the K+ gradient was zero there was no measurable ISC despite the maintained HCO3− gradient).

Figure 6. Potassium dependence of the trans-basolateral current in the nystatin-perforated colon.

Replacement of potassium gluconate with equimolar sodium gluconate in the apical bath over the concentration range 0–120 mM.

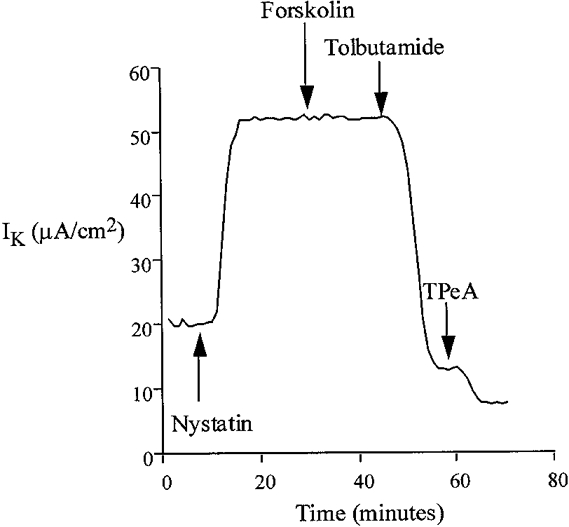

Under conditions designed to preserve the intracellular ionic environment (apical bath containing high [K+] (120 mM), low [Cl−] (20 mM) and low [Ca2+] (10 nM)), the current present under nystatin-permeabilized conditions was almost completely inhibited by basolateral tolbutamide and, to a much lesser extent, by TPeA (Fig. 7). This sensitivity profile of IK to these K+ channel inhibitors was independent of the order of addition of drugs (data not shown). Tolbutamide reduced the K+-dependent current by 47.5 ± 1.2 μA cm−2 (n = 20), corresponding to a 93 % inhibition of the total IK, whereas TPeA inhibited the K+-dependent current by only 6.3 ± 0.8 μA cm−2 (5 % of total IK) (n = 20). The current remaining after combined tolbutamide and TPeA treatment was insensitive to barium and may be generated by paracellular K+ leak from mucosa to serosa, since it was abolished by elimination of the transepithelial K+ gradient (mucosal Na+ substitution for K+). These results imply that under low intracellular [Ca2+], basolateral K+ transport occurs through a sulphonylurea-sensitive K+ conductance pathway.

Figure 7.

Following permeabilization of the apical membrane with nystatin, treatment of the basolateral membrane with forskolin did not alter serosal K+ transport under low apical [Ca2+] conditions. However, the remaining current was almost completely inhibited by basolateral addition of tolbutamide (100 μM).

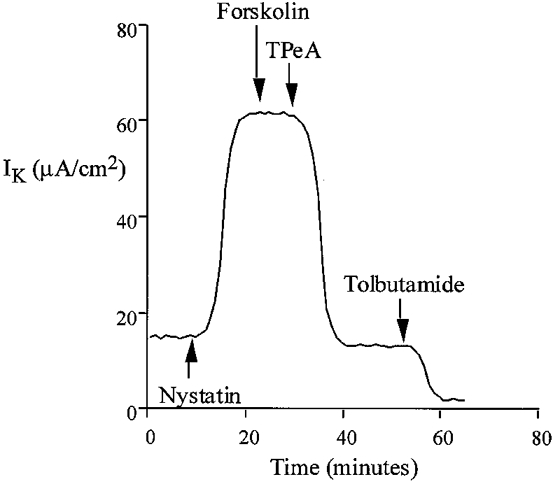

Under experimental conditions with approximately 1 μM free calcium, the addition of nystatin produced an immediate increase in K+-dependent transepithelial current (from 18.4 ± 1.8 μA cm−2, ΔIK = 33.6 ± 2.5 μA cm−2, n = 40). Under these conditions of high [Ca2+]i, the IK was almost completely abolished by TPeA or TEA with relatively low sensitivity to tolbutamide (Fig. 8). TPeA (10 μM) reduced the IK by 45.2 ± 3.8 μA cm−2 (control nystatin IK = 52.6 ± 3.2 μA cm−2, nystatin + TPeA IK = 7.4 ± 0.6 μA cm−2, n = 20), corresponding to an 86 % inhibition of IK, whereas tolbutamide (100 μM) inhibited the IK by only 5.4 ± 0.7 μA cm−2, corresponding to 10 % of total IK (n = 20) (nystatin IK = 55.1 ± 2.7 μA cm−2, nystatin + tolbutamide IK = 49.7 ± 3.5 μA cm−2). This high sensitivity of IK, under conditions of elevated [Ca2+]i, to quaternary ammonium ions and low sensitivity to sulphonylureas is in contrast to the pharmacological profile observed under low [Ca2+]i. The IC50 values for TPeA (5.5 μM), TEA (5.1 mM) and Ba2+ (4.4 mM) are very similar to the half-maximal effective concentration of these drugs on forskolin-induced chloride secretion observed in the intact tissue (Fig. 5). The results indicate that under low physiological levels of intracellular Ca2+, a sulphonylurea-sensitive K+ channel generates the basolateral membrane current. When intracellular [Ca2+] is increased, or when chloride secretion is activated by forskolin, the tolbutamide-sensitive channel is inhibited and basolateral K+ current is carried predominantly by a TPeA-sensitive K+ channel. It has been shown in other tissues that activation of one conductance class downregulates the activity of the other (Germann et al. 1986).

Figure 8.

Inhibition by TPeA (10 μM) of basolateral K+ current in the nystatin-perforated colon under conditions of high intracellular calcium (1 μM Ca2+ in the apical bathing solution). Forskolin (20 μM) did not produce a change in basolateral K+ current in the nystatin-perforated colon at high intracellular [Ca2+].

With 50 nM Ca2+ in the apical bath, the IK was generated by both tolbutamide- and TPeA-sensitive channels (nystatin IK = 55.4 ± 6.6 μA cm−2, nystatin + TPeA IK = 41.7 ± 4.6 μA cm−2, nystatin + TPeA + tolbutamide IK = 6.4 ± 2.1 μA cm−2, n = 6). This implies that under conditions close to physiological levels of intracellular calcium (∼100 nM), approximately 70 % of the IK is generated by tolbutamide-sensitive channels, and the remaining current is generated mainly by TPeA-sensitive channels.

Forskolin effects in nystatin-perforated colon

The colonic crypt is a heterogeneous functional epithelium. Chloride secretion in mammalian colon is believed to occur in cells located in the middle third of the crypt. If nystatin failed to penetrate deep into the crypt, to perforate the apical membrane, the forskolin-induced chloride secretory current should remain intact. We found no response to forskolin following nystatin treatment under conditions designed to measure chloride secretion (physiological Krebs solution in both apical and basolateral baths; nystatin ISC = 0.7 ± 0.2 μA cm−2, nystatin + forskolin ISC = 0.8 ± 0.1 μA cm−2, n = 6, P = 0.25).

The nystatin-induced current has been shown to be essentially generated by a tolbutamide-inhibitable K+ channel under low [Ca2+] conditions and via a TPeA-inhibitable K+ channel with a high [Ca2+]. After treatment with nystatin, forskolin failed to affect transepithelial current under conditions of 10 nM, 50 nM, 100 nM or 1 μM Ca2+ in the external bathing solution; 10 nM and 1 μM experiments are shown in Figs 7 and 8, respectively (nystatin + 10 nM Ca2+IK = 49.7 ± 2.2 μA cm−2, +forskolin IK = 48.4 ± 1.9 μA cm−2, n = 6, P = 0.84; nystatin + 50 nM Ca2+IK = 51.3 ± 1.9 μA cm−2, +forskolin IK = 51.1 ± 1.9 μA cm−2, n = 6, P = 0.63; nystatin + 100 nM Ca2+IK = 50.8 ± 3.1 μA cm−2, +forskolin IK = 50.4 ± 3.0 μA cm−2, n = 6, P = 0.68; nystatin + 1 μM Ca2+IK = 53.7 ± 3.9 μA cm−2, +forskolin IK = 53.1 ± 4.2 μA cm−2, n = 6, P = 0.42).

Intracellular calcium measurements

Basal [Ca2+]i was 131 ± 29 nM (n = 12 crypts). Forskolin did not increase or decrease basal [Ca2+]i of human colonic crypts over 20 min at concentrations of 1–20 μM (n = 12, P > 0.3). [Ca2+]i was 137 ± 31 nM (n = 12 crypts) 20 min after exposure to 20 μM forskolin.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to determine the role of basolateral K+ channels in cAMP-activated secretion in human colon. We found that forskolin activated an immediate and sustained increase in chloride-dependent short-circuit current consistent with chloride secretion. This current was sensitive to inhibition of basolateral Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransport with bumetanide and to a lesser extent to inhibition of Cl−-HCO3− exchange produced by DIDS. Since the maximal sensitivity of human colonic Cl−-HCO3− exchange is approximately 60 % with 1 mM DIDS (Mahajan et al. 1996), experiments were also performed in the nominal absence of CO2/HCO3− in order to completely inhibit Cl−-HCO3− exchange. We found that the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter is responsible for two-thirds of cAMP-dependent chloride secretion under physiological buffer conditions, and that Cl−-HCO3− exchange activity contributes the remaining one-third to the secretory process (Fig. 9). We could not detect any alteration in amiloride-sensitive Na+ transport following forskolin treatment. These results are not reliable because of the small amount (∼2 μA cm−2) of basal amiloride-sensitive current. Forskolin has been shown to inhibit amiloride-sensitive Na+ transport in rat colon (Ecke et al. 1996) and further experiments are required to elucidate the exact effect of cAMP on Na+ transport in intact human colonic epithelium.

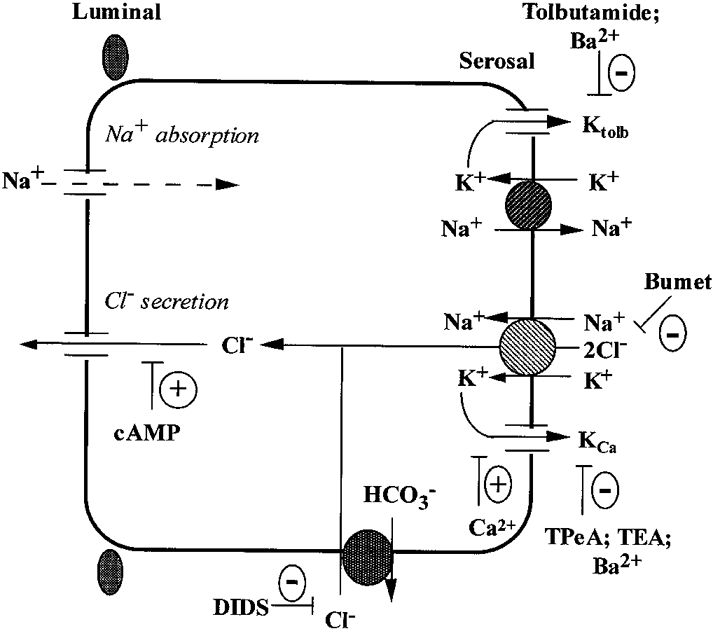

Figure 9. Cell model of the membrane transport processes in the human distal colon.

The basolateral Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and Cl−-HCO3− exchanger contribute two-thirds and one-third, respectively, of transepithelial chloride secretion. The cAMP-activated chloride secretion is dependent on co-stimulation of basolateral calcium-dependent, quaternary ammonium-sensitive K+ channels. A tolbutamide-sensitive K+ channel (Ktolb) is dominant under basal conditions and is inactivated following forskolin-induced Cl− secretion or under conditions of high intracellular calcium. The Ktolb channel shares pharmacological properties with ATP-regulated K+ channels and is most probably involved in basolateral K+ recycling under steady-state and aldosterone-dependent sodium reabsorption conditions. KCa channels and Ktolb channels may be localized in separate cell types (e.g. Ktolb channels in surface Na+ reabsorbing cells and KCa channels in chloride-secreting crypt cells) or the two channel types may co-exist in the same pluripotent crypt cell.

Apical chloride transport must be coupled to basolateral potassium transport if a favourable gradient for chloride secretion is to be maintained (Mandel et al. 1986). There are believed to be two signal transduction pathways involved in human colonic secretion (Weyer et al. 1985; Dharmsathaphorn & Pandol, 1987). Agonists such as carbachol increase intracellular calcium while PGE2 acts through cAMP. In this study we investigated basolateral potassium transport under conditions of high and low cellular [Ca2+] and during cAMP-activated chloride secretion in human colon.

Basolateral K+ conductance was shown to be essential in maintaining a secretory response to forskolin. The potassium channel inhibitor Ba2+ produced an immediate inhibition of the forskolin-activated current. This chloride secretory current was also inhibited by TPeA and TEA at similar doses to those which inhibited basolateral calcium-dependent K+ channels in nystatin-perforated colon. The sulphonylurea tolbutamide, an inhibitor of ATP-dependent K+ channels, had a much smaller effect on forskolin-induced chloride secretion. These results imply a dominant role for a calcium-dependent K+ conductance in cAMP-mediated chloride secretion with a minimal role for tolbutamide-inhibitable K+ channels in the secretory response (Fig. 9). We also found that Ba2+ only blocked 60 % of the Ca2+-dependent K+ conductance, while TPeA and TEA produced < 90 % inhibition of the Ca2+-dependent K+ conductance. This suggests either that this current is carried by a single channel which is only partially inhibited by Ba2+ or that the current is carried by two channels, one of which is insensitive to Ba2+. Previous patch-clamp experiments on isolated human colonic crypts have identified a 23 pS, Ba2+-sensitive and calcium-activated K+ channel on the basolateral membrane of human colonic epithelium (Sandle et al. 1994). Our results suggest that this channel may play an important role in maintaining chloride secretion in human colonic epithelium.

In nystatin-perforated colon, forskolin had no effect on basolateral K+ conductance under the following conditions: (1) at low levels of intracellular calcium when both KATP and KCa channels were active, and (2) when KCa channels were activated by increasing the level of intracellular calcium. This was a surprising result because exposure to cAMP activates Ca2+-activated K+ channels in the basolateral membrane of human colonic crypts (Sandle et al. 1994). Forskolin or exposure to cAMP also activates Ca2+-activated K+ channels in the apical membrane of cultured kidney cells (Guggino et al. 1985), and basolateral K+ channels in rat (Böhme et al. 1991; Siemer & Gögelein, 1992, 1993; Greger et al. 1997b) and rabbit (Loo & Kaunitz, 1989) colonic crypts and T84 cells (Baró et al. 1994). There are two possible explanations for this surprising result. Firstly, our results may be an artefact of using nystatin perforation to investigate K+ transport across the basolateral membrane, and measurements of macroscopic K+ current may not be sensitive enough to measure direct cAMP activation of basolateral K+ channels. This would particularly apply if, as in rat colon, cAMP actually inhibited one group of K+ channels. Secondly, the activation of basolateral K+ transport which supports chloride secretion may occur as a result of an indirect mechanism which is disrupted by nystatin perforation of the apical membrane. Two such signals are membrane potential and intracellular calcium. The evidence does not support a role for intracellular calcium. Carbachol activates chloride secretion and basolateral K+ channels by increasing intracellular Ca2+. We have found that carbachol also activates basolateral K+ conductance in nystatin-perforated human colon using an identical protocol (Winter et al. 1996). Moreover, we found no detectable change in the levels of intracellular calcium measured in isolated colonic crypts exposed to forskolin. However, membrane potential could act as this ‘cross-talk’ signal. Activation of apical chloride channels would depolarize the cell and increase the electrical driving force for basolateral K+ efflux. A possible role for membrane potential in driving basolateral K+ efflux during forskolin-induced chloride secretion in human colon is supported by micro-impalement studies on the human colonic cell line HT-29. Here cAMP does not directly activate basolateral K+ transport but cAMP-activated chloride secretion is associated with significant depolarization (Bajnath et al. 1991). There also appears to be an important interspecies difference between rat and human colon. In rat colon increasing intracellular cAMP activates chromanol-sensitive K+ channels while inhibiting a Ca2+-dependent channel (Greger et al. 1997a, b; Nielsen et al. 1998), and this results in a fall in macroscopic K+ conductance (Schultheiss & Diener, 1997).

cAMP-mediated chloride secretion is an important component of inflammatory and infective colonic disease (Binder et al. 1991). Understanding the mechanism of secretion in intact native human colon is important for developing therapeutic strategies for the medical treatment of diseases of the large intestine. We have shown that during cAMP-mediated chloride secretion chloride enters the cell through two distinct pathways. We have also shown that potassium recycling across the basolateral membrane is an essential component of cAMP-mediated chloride secretion (Fig. 9). This potassium recycling occurs through a Ca2+-activated and TPeA-sensitive pathway; this has not previously been demonstrated in native human colon. We were unable to show direct activation of this pathway by cAMP.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by The Wellcome Trust, grant no. 040067/Z/93.

References

- Ashcroft SJH, Ashcroft FM. Properties and functions of ATP-sensitive K-channels. Cellular Signalling. 1990;2:197–214. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(90)90048-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajnath RB, Augeron C, Laboisse CL, Bijman J, de Jonge HR, Groot JA. Electrophysiological studies of forskolin-induced changes in ion transport in the human colon carcinoma cell line HT-29 Cl.19: lack of clear evidence for a cAMP-activated basolateral K+ conductance. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1991;122:239–250. doi: 10.1007/BF01871424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baró I, Roch B, Hongre AS, Escande D. Concomitant activation of Cl− and K+ currents by secretory stimulation in human epithelial cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;478:469–482. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder HJ, Sandle GI. Electrolyte transport in the mammalian colon. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastro-Intestinal Tract. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 2133–2171. [Google Scholar]

- Binder HJ, Sandle GI, De Signer M. Colonic fluid and electrolyte movement in health and disease. In: Philips SF, Shorter R, Pemberton W, editors. The Large Intestine. New York: Raven Press; 1991. pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme M, Diener M, Rummel W. Calcium- and cyclic-AMP-mediated secretory responses in isolated colonic crypts. Pflügers Archiv. 1991;419:144–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00373000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges RJ, Rummel W, Simon B. Forskolin induced chloride secretion across the isolated mucosa of rat colon descendens. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1983;323:355–360. doi: 10.1007/BF00512476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt BC, Gogelhein H. Small and maxi-K+ channels in the basolateral membrane of isolated crypts from rat distal colon: single channel and slow whole cell recordings. Pflügers Archiv. 1992;420:54–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00378641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Hsieh PS, Dawson DC. A program in BASIC for calculating the composition of solutions with specified concentrations of calcium, magnesium and other divalent cations. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 1988;18:353–366. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(88)90022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor DC, Frizzell RA. Modulation of K channels by arachidonic acid in T84 cells. II. Activation of a Ca2+ independent K channel. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C149–160. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.1.C149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmsathaphorn K, McRoberts JA, Mandel K, Tisdale L, Masui H. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-induced secretion by a colonic epithelial cell line. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1988;75:462–471. doi: 10.1172/JCI111721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmsathaphorn K, Pandol SJ. Mechanism of chloride secretion induced by carbachol in a colonic cell line. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1987;77:348–354. doi: 10.1172/JCI112311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener M, Bridges RJ, Knobloch SF, Rummel W. Neuronally mediated and direct effects of prostaglandins on ion transport in rat colon descendens. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1988;337:74–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00169480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecke D, Bleich M, Greger R. The amiloride inhibitable Na+ conductance of rat colonic crypt cells is suppressed by forskolin. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;431:984–986. doi: 10.1007/s004240050095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germann WJ, Lowy ME, Ernst SA, Dawson DC. Differentiation of two distinct K conductances in the basolateral membrane of turtle colon. Journal of General Physiology. 1986;88:237–251. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger R, Bleich M, Riedemann N, Van Driessche W, Ecke D, Warth R. The role of K channels in colonic Cl− secretion. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1997b;118:A271–275. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(96)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger R, Bleich M, Warth R. New types of K+ channels in the colon. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 1997a;109:497–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger R, Schlatter E. Mechanism of NaCl secretion in rectal gland tubules of spiny dogfish. II The effect of inhibitors. Pflügers Archiv. 1984;402:364–375. doi: 10.1007/BF00583937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggino SE, Suarez-Isla B A, Guggino WB, Sacktor B. Forskolin and antidiuretic hormone stimulate a Ca2+-activated K+ channel in cultured kidney cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1985;249:F448–455. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1985.249.3.F448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halm DR, Rechkemmer GR, Schoumacher RA, Frizzell RA. Apical membrane chloride channels in a colonic cell line activated by secretory agonists. American Journal of Physiology. 1988;254:C505–511. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.4.C505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaerke DA. Regulation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels from rabbit distal colon. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1997;118:A215–217. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(97)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koefoed-Johnsen V, Ussing HH. The nature of the frog skin potential. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1958;42:293–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1958.tb01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SA, Eaton DC, Clausen C, Diamond JM. Nystatin as a probe for investigating the electrical properties of a tight epithelium. Journal of General Physiology. 1977;70:427–440. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo DDF, Kaunitz JD. Ca2+ and cAMP activate K+ channels in the basolateral membrane of crypt cells isolated from rabbit distal colon. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1989;110:19–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01870989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire DD, O'Sullivan GC, Harvey BJ. Potassium ion channels and sodium absorption in human colon. Surgical Forum. 1994;XLV:195–197. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan RJ, Baldwin ML, Harig JM, Ramaswamy K, Dudeja PK. Chloride transport in human proximal colonic apical membrane vesicles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1996;1280:12–18. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel KG, McRoberts JA, Beuerlein G, Foster E, Dharmsathaphorn K. Ba inhibition of VIP and A23187 stimulated Cl secretion by T84 monolayers. American Journal of Physiology. 1986;259:C486–494. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.250.3.C486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MS, Warth R, Bleich M, Weyand B, Greger R. The basolateral Ca dependent K channel in rat colonic crypt cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1998;435:267–272. doi: 10.1007/s004240050511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles RJ, Cuthbert AW. Relation of anion secretory activity to intracellular Ca2+ in response to lysylbradykinin and histamine in a cultured human colonic epithelium. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1991;199:77–91. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandle GI, McNicholas CM, Lomax RB. Potassium channels in colonic crypts. Lancet. 1994;343:23–25. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss G, Diener M. Regulation of apical and basolateral K conductance in rat distal colon. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;122:87–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemer C, Gögelein H. Activation of nonselective cation channels in the basolateral membrane of rat distal colon crypt cells by prostaglandin E2. Pflügers Archiv. 1992;420:319–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00374465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemer C, Gögelein H. Effects of forskolin on crypt cells of rat distal colon: activation of nonselective cation channels in the crypt base and of chloride conductance pathway in other parts of the crypt. Pflügers Archiv. 1993;424:321–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00384359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabcharani JA, Boucher A, Eng JW, Hanrahan JW. Regulation of an inwardly rectifying K channel in the T84 cell line by calcium, nucleotides and kinases. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1994;142:255–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00234947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarroel A, Alvarez O, Oberhauser A, Latorre R. Probing of Ca2+-activated K+ channels with quaternary ammonium ions. Pflügers Archiv. 1988;413:118–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00582521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyer A, Huott P, Liu W, McRoberts JA, Dharmsathaphorn K. Chloride secretory mechanism induced by prostaglandin E1 in a colonic epithelial cell line. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1985;76:1828–1836. doi: 10.1172/JCI112175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills NK, Lewis SA, Eaton DC. Active and passive properties of rabbit descending colon: A microelectrode and nystatin study. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1979;45:81–108. doi: 10.1007/BF01869296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter D, Cuffe J, O'Sullivan GC, Butt AG, Harvey BJ. Calcium mediated potassium channel activation by histamine and carbachol in human colon. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;493.P:52–53. P. [Google Scholar]