Abstract

When short segments of single bundles of circular muscle of guinea-pig antrum were isolated and impaled with two microelectrodes, the membrane potential recordings displayed an ongoing discharge of noise.

Treating the preparations with acetoxymethyl ester form of BAPTA (BAPTA AM) reduced the membrane noise and revealed discrete depolarizing unitary potentials. The spectral densities determined from control preparations and ones loaded with BAPTA had similar shapes but those from control preparations had higher amplitudes, suggesting that membrane noise results from a high frequency discharge of unitary potentials.

Depolarization of isolated segments of antrum initiated regenerative responses. These responses, along with membrane noise and unitary potentials, were inhibited by a low concentration of caffeine (1 mm).

Loading the preparations with BAPTA decreased the amplitudes of regenerative responses. Depolarization was now seen to increase the frequency and mean amplitude of unitary potentials over a time course similar to that of a regenerative potential.

Noise spectra determined during periods of rest, during regenerative potentials triggered by direct depolarization and during slow waves, recorded from preparations containing interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), had very similar shapes but different amplitudes.

The observations suggest that a regenerative potential, the secondary component of a slow wave, is made up of a cluster of several discrete unitary potentials rather than from the activation of voltage-dependent ion channels.

Many gastrointestinal muscles generate rhythmic contractions that are associated with slow waves (Tomita, 1981; Sanders, 1992). Several observations suggest that activity originates in interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), and that smooth muscle cells act as follower cells (Sanders, 1996). Thus, when regions containing ICC are cut away, slow waves are abolished (Smith et al. 1987). Similarly intestinal preparations obtained from strains of mice which lack ICC, fail to generate normal slow waves (Ward et al. 1994; Huizinga et al. 1995). In guinea-pig antrum, ICC generate large amplitude driving potentials which depolarize the circular layer. The depolarization triggers a secondary regenerative response, so giving rise to a complete slow wave (Dickens et al. 1999).

Previous analyses of slow waves have suggested that they resulted from the sequential activation of voltage-dependent ion channels (Sanders, 1992). However, when single bundles of circular muscle from the antral region of guinea-pig stomach were stimulated directly, they generated regenerative potentials that did not depend upon the activation of conventional voltage-dependent ion channels. Rather they appeared to involve the voltage-activated release of internal Ca2+ following the production of a second messenger like inositol trisphosphate (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999). Membrane depolarizations, that do not involve conventional voltage-dependent ion channels, are generated when increases in [Ca2+]i activate ion selective channels that allow an accumulation of internal positive charge (van Helden, 1991; Pacaud & Bolton, 1991; Large & Wang, 1996; Hashitani et al. 1996). In smooth muscle, groups of such channels are often activated intermittently at rest, giving rise to discrete transient depolarizing potentials (van Helden, 1991; Hashitani et al. 1996). When a transmitter is applied, it often activates a second messenger pathway which causes several transient depolarizing potentials to sum together and trigger an excitatory junction potential (van Helden, 1991; Hill et al. 1993). Regenerative potentials in stomach muscle had properties which matched those of the secondary component of slow waves. This suggests that during a slow wave a driving potential would activate a regenerative potential (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999), so giving rise to the secondary component of the slow wave (Dickens et al. 1999). During the resulting depolarization, L-type calcium channels (CaL channels) are activated but their contribution to the shape of a slow wave is barely detectable (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999).

During the study on antral smooth muscle, it was noted that membrane potentials displayed noise (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999) which appeared to increase during a regenerative potential. This report has examined the possibility that in guinea-pig antrum, membrane noise results from a discharge of discrete unitary potentials and that regenerative potentials result from a transient increase in the frequency of these potentials.

METHODS

The procedures described here have been approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee at the University of Melbourne. Guinea-pigs of either sex were stunned, exsanguinated, and the stomach removed. The methods have been described recently (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999). Briefly the stomach was immersed in oxygenated physiological saline (composition (mM): NaCl, 120; NaHCO3, 25; NaH2PO4, 0.1; KCl, 5; MgCl2, 2; CaCl2, 2.5; and glucose, 11.1; bubbled with 95 % O2-5 % CO2), cut along the greater curvature and the mucosa removed. In a few experiments single bundles of circular muscle (diameter 150–200 μm, length 600–1000 μm) with the longitudinal muscle layer attached, were used. In most experiments, single bundles of circular muscle (diameter 150–200 μm, length 300–600 μm) with the longitudinal layer removed, were pinned serosal surface uppermost in a recording chamber. Preparations were impaled with two independently mounted microelectrodes (90–150 MΩ) filled with 0.5 M KCl; use of a low molarity filling solution allowed long lasting, 3–5 h, impalements to be readily obtained. In some experiments, both electrodes were used to measure membrane potential changes. In others, one electrode was used to pass current and the second to record membrane potential. Signals were amplified using an Axoclamp-2A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA), low pass filtered (cut-off frequency, 100 Hz) digitized and stored on computer for later analysis. Preparations were superfused with physiological saline solution, warmed to 35°C, and were allowed to equilibrate for 2 h before recordings started. In initial experiments, periods of membrane noise were recorded before and after the addition of nifedipine (1 μM). As the membrane noise was unchanged, nifedipine (1 μM) was routinely added to the physiological saline to prevent involvement of L-type calcium channels in membrane potential changes.

Acetoxymethyl ester of bis-(aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA AM), caffeine and nifedipine (each obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) were used in these experiments.

Analysis of noise spectra

Most of the membrane potential recordings obtained from stomach muscle were dominated by large amplitude noise signals arising from the membranes of cells in these preparations. These were analysed by determining their power spectrum, or spectral density. A voltage signal can be represented as a sum of sine waves of different frequencies, with each frequency having an appropriate weighting and phase angle. The spectral density of a signal reflects the waveform energy at each frequency. Spectral densities were estimated by taking the square of the magnitude of the fast Fourier transform (FFT) of sequences of between 512 and 12 000 points of sampled data. The straight line of best fit to the data was first subtracted from each sequence to remove the DC contribution as well as any monotonic trend in voltage. This trend removal was particularly important for sequences selected from repolarization phases of regenerative potentials and slow waves. The sequence was then multiplied by the Welch window function (eqn 12.7.15 of Press et al. 1988) to reduce leakage of estimates to nearby frequency classes. Suites of FFTs of 8 or 16 data sequences were then averaged to improve the estimate of spectral density.

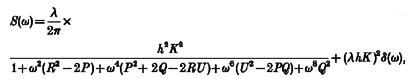

Spectral density functions were described theoretically in a way based on that discussed by Lee (1960). The spectral density functions of trains of identical events, which occur independently of each other at exponentially distributed intervals, termed Poisson waves, are determined by the shape of the unitary event. When the unitary event, termed a shot potential (Katz & Miledi, 1972), consists of an instantaneous rise followed by an exponential decay (Fig. 1A), the spectral density of the Poisson wave has a characteristic shape. The spectral density is constant at low frequencies and becomes proportional to f−2 at high frequencies (Katz & Miledi, 1972; Verveen & DeFelice, 1974). Such Lorentzian curves describe the frequency profile of currents produced by populations of independent channels whose transitions between open and closed states are described by Poisson statistics (Anderson & Stevens, 1973). When the relationship between spectral density and frequency is plotted on doubly logarithmic axes, the gradient at low frequencies is close to zero and as frequency increases, the gradient approaches −2 (Fig. 1B). If an additive high frequency noise limit is approached, the gradient is seen to return towards zero but never becomes more negative than −2. Verveen & DeFelice (1974) give the expression for the spectral density of a Poisson wave composed of shot potentials which are described by the difference between two exponential functions (eqn 3.25 of Verveen & DeFelice, 1974; Fig. 1A). At high frequencies, the spectral density becomes proportional to f−4, so its gradient approaches −4 when plotted on doubly logarithmic axes (Fig. 1B). The unitary potentials recorded from the circular muscle of the guinea-pig stomach could not be well described by exponentially decaying steps or by the difference between two exponential functions. However, they were well described by the difference between two exponential functions raised to the third power (see Fig. 5). This form of shot potential, v(t), can be represented by the following equation:

| (1) |

and where, h is an amplitude scaling factor, and A and B are time constants. After substituting v(t) for g(t) in eqns 3.7 and 3.8 (of Verveen & DeFelice, 1974), eqn 3.6 yields the following expression for spectral density:

|

(2) |

where ω is frequency in rad s−1 (2πf, where f is frequency in Hz); λ Hz is the mean frequency of occurrence of unitary potentials;

|

and δ(ω) is the Dirac delta function.

Figure 1. Relationship between time courses of ‘shot’ events and spectral power density functions.

A shows the time course of three different potential changes whose time courses are readily described. A shot potential was simulated by instantaneous rise and exponential decay with a time constant of 160 ms. Such events give rise to a spectral density curve, frequently described as a Lorentzian curve (Ba). When a shot potential can be described by the difference between two exponentials (Ab), the gradient of the spectral density versus frequency curve approaches −4 (Verveen & DeFelice, 1974). When a shot potential can be described by the difference between two exponentials raised to the power 3 (Ac), the gradient of the spectral density plot approaches −8 (Bc). The spectral density plots have been normalized to have the same peak values at 0.1 Hz; the time constants used for both complex shot events were A, 400 ms and B, 80 ms (see eqn (1)).

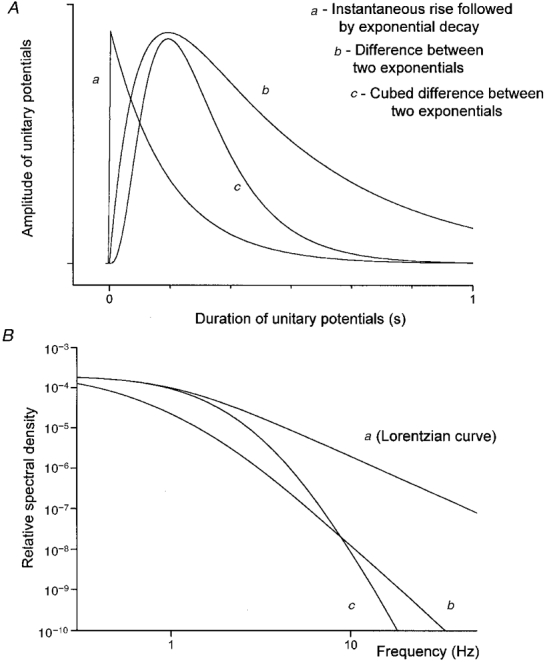

Figure 5. Theoretical fits of three unitary potentials selected for their range of amplitudes, along with description of their frequency of occurrence.

The three curves in A, represent the best fits of the function given in eqn (1) to describe three different spontaneous unitary potentials recorded from the same bundle of circular muscle illustrated in Fig. 2B. • illustrate data points. The two time constants (A and B) required to obtain satisfactory fits according to eqn (1) are given for each curve. Also given are the scaling factors (h) which allowed the amplitudes of the theoretical fits to be scaled to the data points. The lower graph B, shows the experimentally determined intervals between unitary potentials (□) compared with the theoretical distribution of a Poisson wave (▪) occurring at the same mean interval of 1.65 s.

This expression for S (ω) was checked by Fourier transforming simulated individual unitary events generated using eqn (1) and comparing the spectral densities with plots of S (ω) generated using eqn (2). At high frequencies, the spectral density of a Poisson wave of identical shot potentials, whose shape is described by eqn (1), is proportional to f−8. Thus the gradient of spectral density versus frequency, plotted on doubly logarithmic axes, approaches −8 (Fig. 1B). Fast Fourier Transformations, simulations and model parameter optimizations were carried out using Origin 5.0 (Microcal Software Inc., Northampton, MA, USA). Means ±s.e.m. are quoted throughout.

RESULTS

Membrane potentials recorded from single bundles of circular muscle from the antral region of guinea-pig stomach

Preparations of circular muscle were impaled with two independent microelectrodes. Cells had negative membrane potentials in the range −65 to −58 mV (−60.4 ± 0.7 mV; n = 23; mean ± s.e.m.; n = number of observations, where each n value represents a measurement from a preparation taken from a separate animal). When one electrode was used to pass current, the other was used to record the ensuing electrotonic potentials. The time courses of electrotonic potentials produced by small, i.e. < 1 nA, hyperpolarizing currents were well described over their entire range by single exponentials with time constants in the range 110 to 315 ms (175 ± 11 ms; n = 23). These observations suggest that the preparations are isopotential except perhaps for very fast events (see Hirst & Neild, 1980, for further discussion). The preparations had input resistances in the range 1.4–12.1 MΩ (4.3 ± 0.2 MΩ; n = 23).

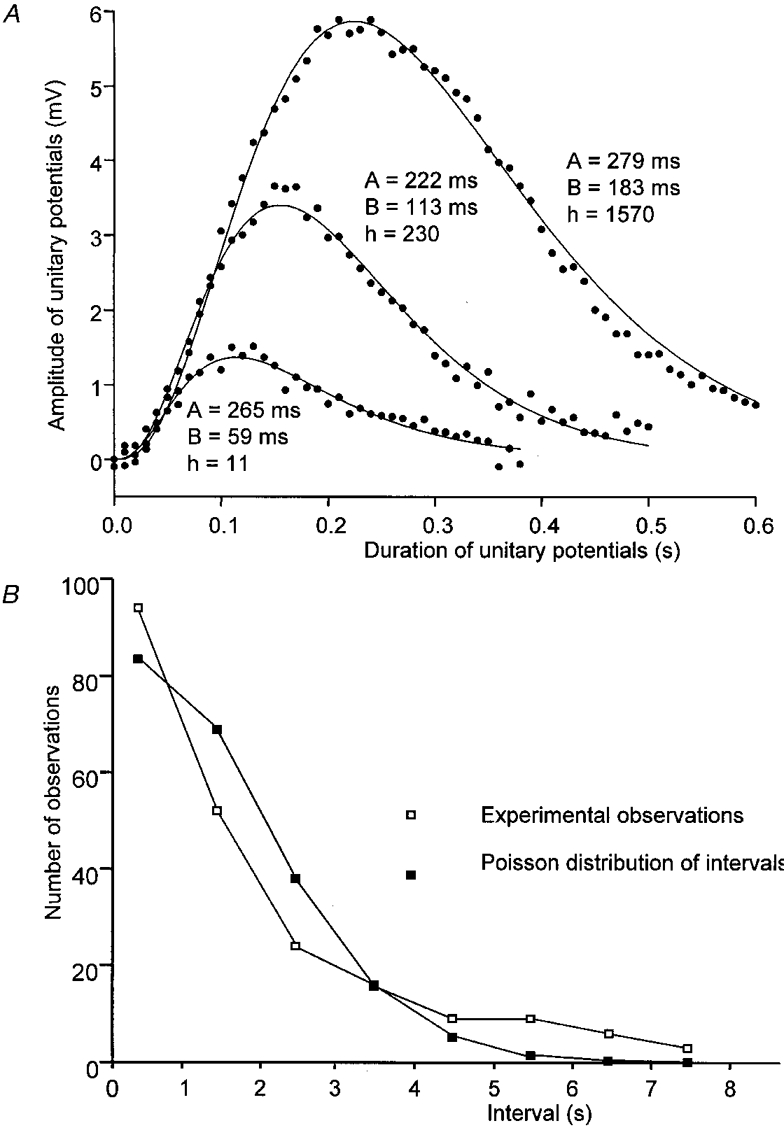

When membrane potential recordings were inspected, they were found to be dominated by membrane noise (Fig. 2Aa and b). The recordings obtained with either electrode were very similar, despite the fact that the electrodes were usually separated by some 100–200 μm. The membrane noise, which was unchanged by adding nifedipine (1 μM) to the physiological saline, was abolished by superfusing the tissues with physiological saline containing BAPTA AM (50 μM) for 10 min. However, if a lower concentration of BAPTA AM (10–20 μM) was added to the physiological saline for 10–15 min, spontaneous membrane potential changes were readily detected. Most spontaneous membrane potential changes had the form of discrete depolarizing unitary potentials (Fig. 2Ba and b). In a few preparations an ongoing discharge of transient hyperpolarizing potentials was also detected (Fig. 2Ba and b, and Fig. 6E). These invariably had smaller amplitudes than the depolarizing unitary potentials. Although the occurrence of the two distinct events appeared to be unrelated, both appeared to depend upon an increase in [Ca2+]i as both were abolished by high concentrations of BAPTA AM (50 μM).

Figure 2. Effect of BAPTA on membrane noise recorded from a single bundle of circular muscle from the antral region of guinea-pig stomach.

The upper pair of traces (Aa and b) shows simultaneous recordings of membrane noise obtained using two independent intracellular recording electrodes, placed some 300 μm apart in the same isolated muscle bundle; recordings made in control solution. The peak negative membrane potential was −59 mV. The lower pair of traces (Ba and b) shows recordings from the same cells some 20 min after the preparation had been loaded with BAPTA by adding BAPTA AM (20 μM) to the physiological saline. It can be seen that in each pair of recordings the membrane potential changes detected are very similar. In control solution membrane potential excursions of up to 10 mV are detected (A). After loading with BAPTA, the membrane noise is much reduced and unitary potentials, some with amplitudes approaching 10 mV are now recorded (B). The peak negative membrane potential was −58 mV. The events identified as unitary potentials are indicated •. Voltage and time calibrations refer to all recordings.

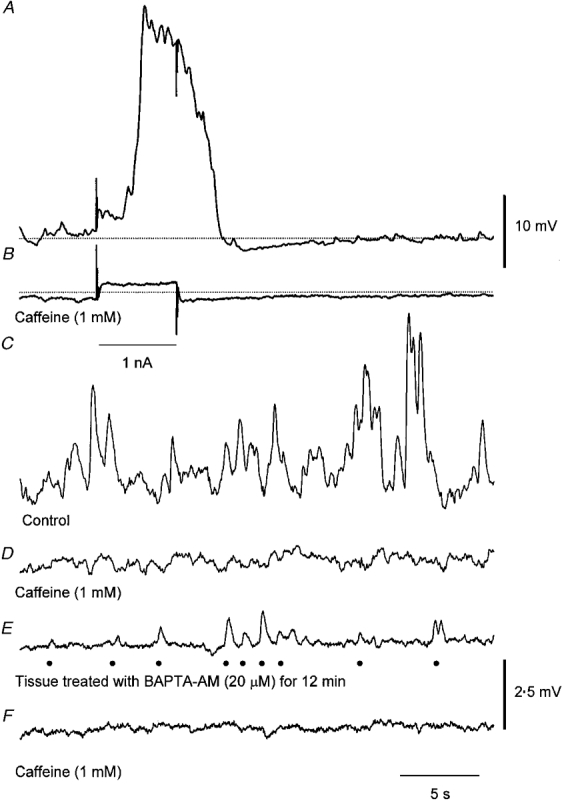

Figure 6. Effect of caffeine on regenerative potentials, membrane noise and unitary potentials recorded from circular muscle of guinea-pig antrum.

The upper trace (A) shows a regenerative potential triggered by a depolarizing current pulse +1 nA. The second trace (B) shows the membrane potential change produced by the same current some 2 min after adding caffeine (1 mM) to the physiological saline. The dotted line indicates a membrane potential of −61 mV in both traces. Note that large membrane potential transients were detected on the falling phase of the regenerative potential and the membrane noise was reduced immediately after the regenerative potential. The control membrane noise (C) was reduced by caffeine (D) which was associated with a small sustained membrane hyperpolarization. In another preparation which had been loaded with BAPTA, (20 μM BAPTA AM applied for 12 min), unitary potentials were detected (E) and these were abolished by caffeine (F). •, events identified as unitary potentials. The upper voltage calibration applies to the upper two traces and the lower to the lower four traces. The time calibration applies to all traces.

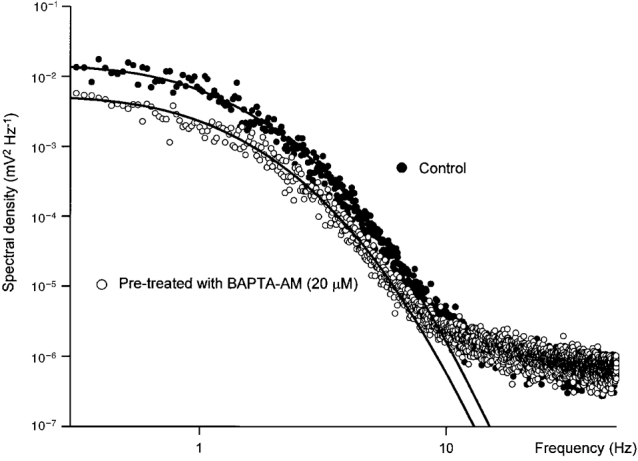

It seemed possible that noise discharges, detected in control solution, might result from the high frequency discharge of unitary potentials, detected in BAPTA-loaded preparations. This possibility was examined by determining the power spectral densities of membrane potential recordings made in control and after moderate loading of the tissues with BAPTA (Fig. 3). When this was done, both spectra were found to have similar shapes. In both curves, energy increased from very low values above 10 Hz to approach a plateau value somewhere below 1 Hz (Fig. 3). Invariably control curves had higher energy values at low frequencies than did those determined after loading the preparations with BAPTA. At higher frequencies the gradient of both curves approached zero, reflecting the properties of the microelectrodes, the recording system and presumably any conventional ion channels active in the membranes of the preparation. Unlike the spectral density curves detected in other biological membranes (see Katz & Miledi, 1972) where the curves reflect channel noise, the spectral power decayed very rapidly at even moderate frequencies. In Fig. 3, for example, the most negative gradient seen in the control spectrum was about −5.5 and occurred at about 7 Hz (−5.6 ± 0.4 at 5.5 ± 0.6 Hz, n = 4). Together the observations suggest that treating a preparation with BAPTA simply reduces the energy of the spectral density plot without otherwise changing its shape. Since it was possible to detect similarly large excursions of membrane potential in control and BAPTA-loaded preparations (Fig. 2), it seems most likely that BAPTA simply reduced the frequency of unitary potentials.

Figure 3. Spectral density curves illustrating the properties of the membrane noise detected before and after loading a preparation with BAPTA.

The data set illustrated • was obtained by averaging spectral densities of several membrane noise records like those shown in Fig. 2A. The second data set ^, was obtained in the same way but taking similar lengths of recordings from the preparation after treating with BAPTA AM (20 μM for 15 min, Fig. 2B). Each set of data is fitted with curves of best fit, defined by eqn (2), which were fitted for frequencies less than 7 Hz. It can be seen that in both sets of data the spectral density curves tended towards a plateau at frequencies less than 1 Hz. At frequencies above 1 Hz the gradient of the line rapidly steepened to −5 at frequencies of 5–7 Hz. At frequencies above 10 Hz, the gradient returned towards zero as the recordings became dominated by high frequency components, including microelectrode and recording system noise. In this example the time constants (A and B) appearing in eqn (1), used to generate the theoretical curves, are 505 and 55 ms respectively. The scaling factors indicated that the low frequency spectral power fell by 64 % when the preparation was loaded with BAPTA.

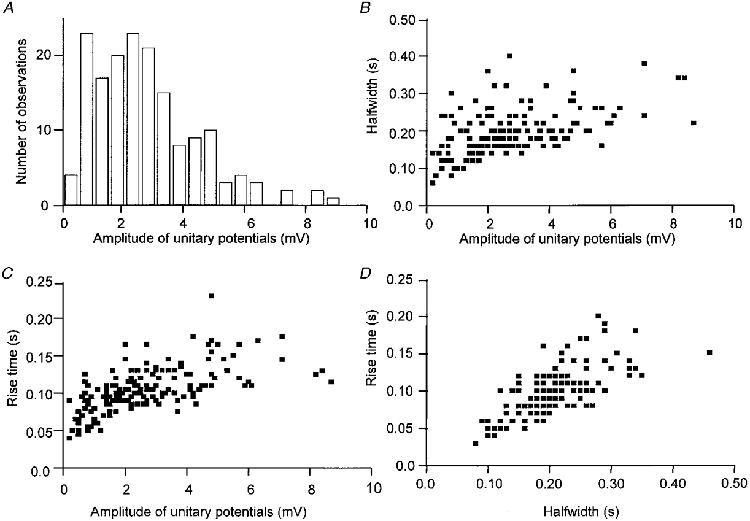

We were concerned that the spectral density curves differed from those reported previously in respect of the rapid rate of decay of energy at even moderate frequencies (see Fig. 1). It has been pointed out that all the frequency information found in a plot of spectral density is contained in a single example of the unitary event which makes up the noisy signal when occurring as a Poisson wave (Lee, 1960). Therefore, the time courses and amplitudes of unitary potentials were determined, to check to see if they had any temporal characteristics which might ultimately account for the spectral shapes detected experimentally (Fig. 3). In the example shown in Fig. 2B unitary potentials occurred at a mean frequency of 0.26 Hz. These had amplitudes in the range 0.5 to 9 mV (Fig. 4A), with a modal value of about 2 mV. There was a tendency for both the half-width (the time that potential change is above 50 % of its peak amplitude) and the rise time (the time between 10 % and 90 % of the peak amplitude) to increase with the amplitude of an individual unitary potential (Fig. 4B and C). Potentials with longer rise times had longer half-widths (Fig. 4D). When the time constant of the final phase of the larger individual unitary potentials was determined, it was found to be some 130 ms. This was marginally greater than that of the electrotonic potential of the preparation, in this case 120 ms. Similar observations were made on six other preparations, the results from the experimental series are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 4. Properties of spontaneous unitary potentials recorded from a single bundle of circular muscle that had been loaded with BAPTA.

The histogram (A) and three scatter diagrams (B, C and D) illustrate the properties of spontaneous unitary potentials recorded from the bundle of circular muscle, loaded with BAPTA, illustrated in Fig. 2B. The histogram (A) indicates that the unitary potentials had amplitudes which ranged from some 0.5 to 9 mV. The scatter diagram B shows the relationship between amplitudes of unitary potentials and their half-widths; as their amplitudes increase, there is a tendency for their durations to increase. The scatter diagram (C) shows the relationship between amplitudes of unitary potentials and their rise times; as their amplitudes increase there is a tendency for their rise times to lengthen. The scatter diagram (D) shows the relationship between half-width and rise time; potentials with longer half-widths had longer rise times.

Table 1.

Properties of spontaneous and evoked unitary potentials recorded from single bundles of circular muscle isolated from the antral region of guinea-pig stomach

| Properties of spontaneous unitary potentials | Electrical properties of muscle bundles | Properties of evoked unitary potentials | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt no. | Amplitude (mV) | Rise time (ms) | Half width (ms) | No. obs | Time constant (ms) | n | Amplitude* (pA) | IR (MΩ) | Time constant (ms) | Amplitude (mV) | Rise time (ms) | Half width (ms) | No. obs |

| i | 1.50 ± 0.08 | 148 ± 8 | 290 ± 10 | 72 | 245 ± 25 | 22 | 200 | 7.6 | 170 | 2.54 ± 0.21 | 156 ± 7 | 349 ± 17 | 65 |

| ii | 1.12 ± 0.06 | 177 ± 8 | 217 ± 8 | 63 | 219 ± 25 | 26 | 600 | 1.8 | 162 | 1.31 ± 0.09 | 168 ± 11 | 225 ± 13 | 63 |

| iii | 1.42 ± 0.14 | 180 ± 9 | 321 ± 14 | 37 | 253 ± 30 | 24 | 400 | 3.8 | 165 | 1.67 ± 0.15 | 181 ± 10 | 324 ± 18 | 46 |

| iv | 2.64 ± 0.13 | 97 ± 2 | 209 ± 5 | 165 | 132 ± 7 | 21 | 360 | 7.4 | 118 | 3.50 ± 0.4 | 94 ± 4 | 187 ± 11 | 64 |

| v | 1.21 ± 0.07 | 87 ± 4 | 178 ± 5 | 122 | 156 ± 35 | 24 | 250 | 5.1 | 102 | 2.07 ± 0.21 | 89 ± 3 | 184 ± 6 | 118 |

| vi | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 126 ± 7 | 285 ± 13 | 68 | 259 ± 40 | 23 | 700 | 1.2 | 204 | 1.14 ± 0.08 | 127 ± 6 | 263 ± 10 | 67 |

| vii | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 174 ± 5 | 305 ± 10 | 89 | 258 ± 30 | 21 | 270 | 3.7 | 210 | — | — | — | — |

The amplitude of the current underlying a spontaneous unitary potential was obtained by taking the mean peak amplitude of a unitary potential and dividing that value by the corresponding value of input resistance. Expt no., experiment number; IR, input resistance; No. obs, number of observations.

We were unable to describe the time courses of individual unitary potentials with a simple function, for example, a rapid rise and exponential decay or the difference between two exponentials. However, in each preparation individual unitary potentials could be well described by the difference between two exponentials raised to the third power (Methods, eqn (1)). Three individual units, which reflect the range of potentials shown in Fig. 4A, have been selected and fitted with appropriate exponential functions. As the amplitude increased, the rise time and half-width increased but still gave a good empirical description of the units by varying the exponential function parameters (Fig. 5). The relationship which describes the spectral density of a series of unitary events whose time courses reflect the difference between two exponentials raised to the third power is given by eqn (2) (see Methods). The spectral densities derived from recordings in control and BAPTA-loaded preparations were each well described by this relationship (Fig. 3). For each fit, common values of exponential functions were used (A = 505 ms, B = 55 ms), however, in the BAPTA-loaded preparation the spectral density was reduced to 36 % of control levels in the region below 10 Hz. This suggests that, in both cases membrane noise was composed of sums of Poisson waves of unitary events which had the same range of time courses. In four preparations, the exponential time constants of best fit were A = 547 ± 28 ms and B = 74 ± 8 ms in control. After loading with BAPTA (10 μM), the time constants of best fit were A = 571 ± 77 ms and B = 84 ± 11 ms and the amplitude of the spectral density was reduced to 26.7 ± 8.4 % (n = 4) of control levels. Using a paired two-tailed t test, neither value of time constant was significantly changed by loading with BAPTA, P > 0.1 in both cases.

The assumption that the intervals between unitary potentials conform to Poisson statistics was checked in three experiments where the unitary events were very much larger than the recording noise. The example shown is that illustrated in Fig. 2B. The intervals between successive events were determined and compared with the distribution function for a Poisson process having the same mean frequency of occurrence (Fig. 5B). The cumulative distribution function for the intervals was tested against the cumulative distribution function for this Poisson process using a two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (Hashitani & Edwards, 1999). In this and the other two cases, the differences were not significant (P > 0.05). Applying Durbin's transformation to the cumulative distribution allowed a more powerful test of goodness of fit of the data to a Poisson process of the same mean frequency (Durbin, 1961). Two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov testing of the transformed distributions again failed to show significant differences from Poisson processes of equivalent mean frequency (P > 0.05). These analyses suggest that the process that generates unitary potentials is adequately described by Poisson statistics.

It was clear that successive unitary potentials had neither identical amplitudes nor identical time courses (Fig. 2B). However, when spectral densities of the three unitary potentials shown in Fig. 5 were added, after weighting according to the probabilities of occurrence indicated in Fig. 4A, the resultant spectrum overlaid the curve of best fit for BAPTA-loaded tissue for frequencies above 1 Hz. Low frequency densities were underestimated due to the omission of slower unitary potentials in constructing the composite spectral density. Thus a three component approximation to the sum of spectral densities was sufficient to model the shoulder and steep decay regions of the measured spectral density. This observation is in accord with the superposition property for independent random time series (eqn (2.26) of Verveen & DeFelice, 1974): that is, the spectral density of a composite time series, made up of several independent Poisson wave sources with differing event shapes and amplitudes, is equal to the sum of their spectral densities.

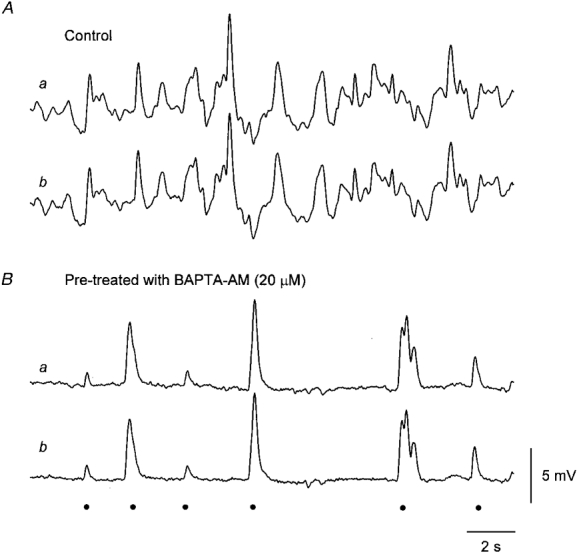

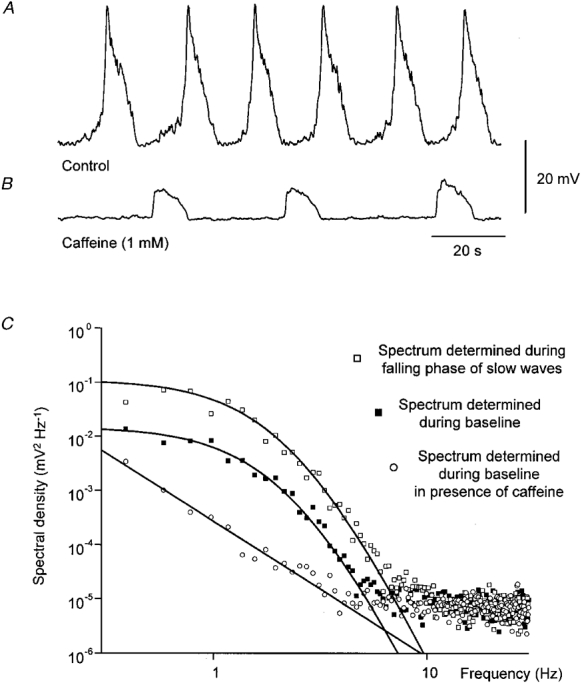

Effect of caffeine on regenerative potentials, membrane noise and unitary potentials recorded from single bundles of circular muscle from the antral region of guinea-pig stomach

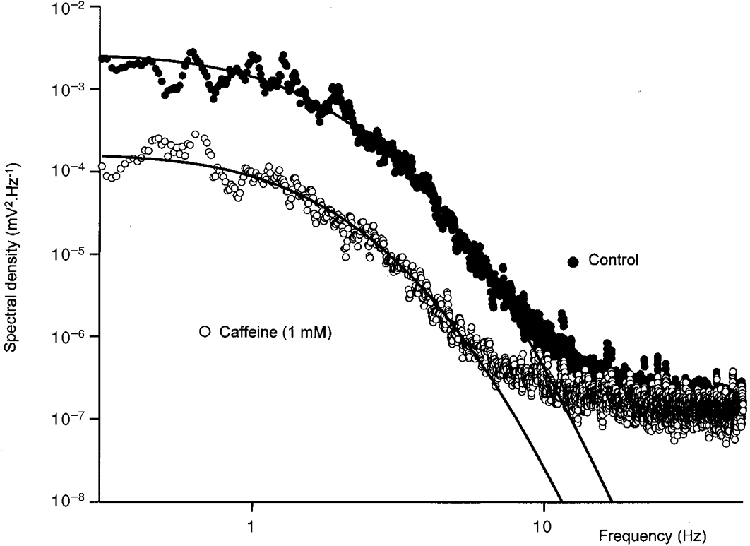

It has previously been shown that low concentrations of caffeine abolish both regenerative potentials (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999) and the secondary component of slow waves (Dickens et al. 1999). In this series of experiments we examined the effects of low concentrations of caffeine on regenerative potentials and membrane noise and on unitary potentials detected in preparations that had been pre-treated with BAPTA AM (10–20 μM). Caffeine (1 mM) rapidly abolished regenerative potentials triggered by depolarizing the preparation (Fig. 6A and B), often causing a hyperpolarization of some 2–4 mV and invariably reducing the membrane noise (Fig. 6C and D).

When the spectral densities of the control and caffeine- treated preparations were determined, it was found that the spectral power at frequencies below 10 Hz was reduced by caffeine (Fig. 7). In the illustrated case, the theoretical curve fits indicated that the spectral density had fallen to about 6 % of the control value. In other preparations the spectra determined in caffeine had little or no energy that could be attributed to the discharge of unitary potentials (see as an example Fig. 11C). The average proportion of energy remaining after treating with caffeine (1 mM) was about 7 % of control (7.4 ± 3.7 %; n = 5). The most negative gradient in the control spectrum shown is −5.6, again exceeding that of a Lorentzian characteristic, and occurs at about 7 Hz (−5.4 ± 0.2 at 6.5 ± 0.6 Hz, n = 4). The exponential time constants (eqn (1)) which allowed the best fit of eqn (2) to the spectra shown in Fig. 7 were A = 395 ms and B = 60 ms and average values of A were 532 ± 49 ms and of B were 57 ± 6 ms (n = 5). In contrast to the recordings made from tissues loaded with BAPTA, inspection of the membrane potential recordings made in the presence of caffeine failed to reveal a discharge of obvious large spontaneous unitary potentials (Fig. 6D), suggesting that caffeine reduces the size of unitary potentials.

Figure 7. Effect of caffeine on spectral density curves of membrane noise.

The spectral density curves were calculated from data illustrated in Fig. 6C and D. •, control data; ^, membrane noise detected in caffeine (1 mM). Each set of data is fitted with curves of best fit, described by eqn (2), fitted for frequencies of less than 7 Hz. The time constants (A and B) appearing in eqn (1), used to generate the theoretical curves, were 395 and 60 ms respectively. The change in scaling factor indicated that caffeine reduced the low frequency spectral power by 94 %.

Figure 11. Spectral density curves illustrating the properties of the membrane noise detected before a slow wave, during the secondary component of the slow wave and after abolishing the secondary component of the slow wave with caffeine.

The upper trace (A) shows a series of slow waves initiated in a bundle of circular muscle of antrum with the longitudinal muscle layer left attached. The baseline spectra (▪, C) were determined from regions before the upstroke of the slow wave. Slow wave spectra (□, C) were determined during the falling phases of successive slow waves. After the addition of caffeine (1 mM) the secondary components of the slow waves were abolished but the primary components of the slow waves, initiated at low frequency persisted (B). The noise spectra of membrane potential recordings between primary components (^, C) displayed little spectral power that could be attributed to the discharge of unitary potentials. The time and voltage calibrations apply to both membrane potential recordings. The control spectral density curves were well described using eqn (2) with the time constants of 375 ms for A and of 125 ms for B.

When preparations that had been loaded with BAPTA were treated with caffeine (1 mM) the discharge of unitary potentials was rapidly abolished (Fig. 6E and F). Similar observations were made on four other preparations. Washing with drug-free solution readily reversed these effects of caffeine. In three of these experiments, spontaneous transient hyperpolarizations were also detected, however the occurrence of these potentials, unlike the depolarizing unitary potentials, was not prevented by this concentration of caffeine (Fig. 6E and F).

Together these pharmacological observations indicate that unitary potentials, regenerative potentials and the discharge of membrane noise involve a step that can be disrupted by low concentrations of caffeine.

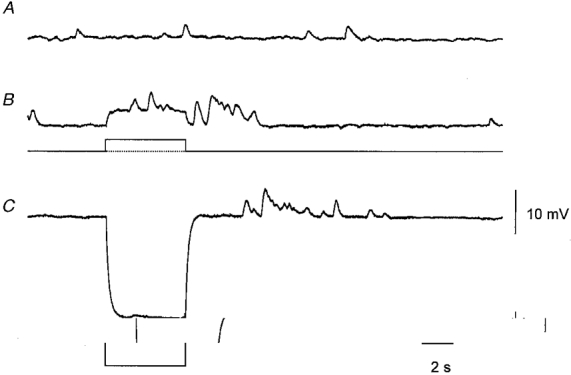

Comparison between spontaneous and evoked unitary potentials recorded from segments of circular muscle loaded with BAPTA

If regenerative potentials are made up of the synchronized discharge of many unitary potentials, the membrane potential changes that trigger a regenerative potential should accelerate the frequency of unitary potentials detected in preparations loaded with BAPTA. Results from such an experiment are shown in Fig. 8. The preparation had previously been loaded with BAPTA by incubating it in physiological saline containing BAPTA AM (20 μM) for 10 min. In the absence of stimulation an ongoing discharge of unitary potentials was detected (Fig. 8A). A depolarizing step increased the frequency of unitary potentials after a delay of 1 s for about 8 s (Fig. 8B). A similar discharge of unitary potentials was triggered after a period of membrane hyperpolarization (Fig. 8B). Thus like regenerative potentials, positive going membrane potential changes, rather than membrane depolarization (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999), triggered a discharge of unitary potentials. This anomalous behaviour occurs because a finite period of hyperpolarization resets the threshold for activation of regenerative potentials to a more negative value. During the decay of a hyperpolarizing electrotonic potential, the membrane potential passes through the new threshold and triggers a regenerative response (G. D. S. Hirst & F. R. Edwards, unpublished observations).

Figure 8. Discharge of unitary potentials evoked by changing the membrane potential of a single bundle of antral muscle.

The upper trace (A) shows the spontaneous discharge of unitary potentials recorded from a preparation that had been treated with BAPTA AM (20 μM) for 10 min. Depolarizing the membrane by passing current through the second intracellular electrode (B) evoked a discharge of unitary potentials during and following the electrotonic potential. A discharge of unitary potentials was also triggered shortly after the end of an electrotonic potential (C) evoked by a hyperpolarizing current pulse. The time bar applies to all traces. The voltage calibration bar applies to the three membrane potential recordings; the current calibration bar applies to the two current recordings. The membrane potential was −59 mV.

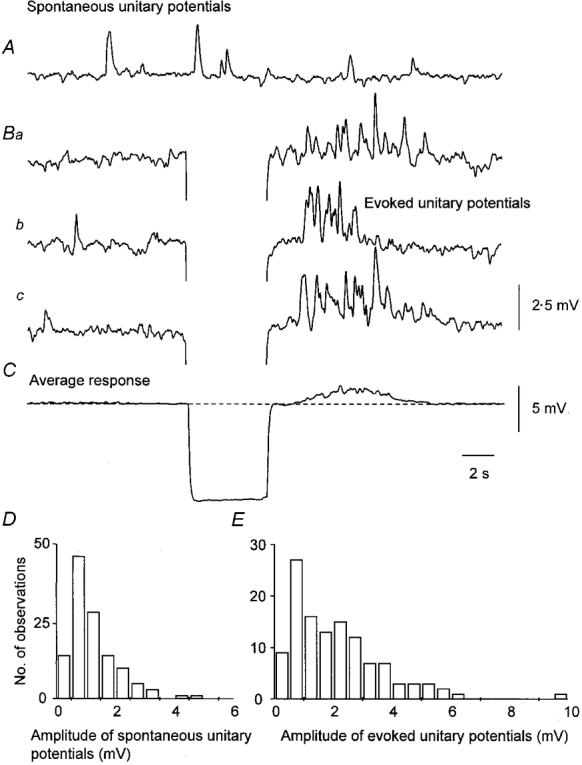

As the reversal potential of the unitary potentials is not known, to avoid changing their driving potential, all measurements of the properties of evoked unitary potentials were made on responses triggered by periods of membrane hyperpolarization. An experiment is shown in Fig. 9 where the preparation had been loaded with BAPTA AM (10 μm for 15 min). In the absence of stimulation, unitary potentials occurred at a frequency of 6.1 unitary potentials min−1. Shortly after a hyperpolarization of some 10 mV (Fig. 9C), unitary potentials occurred at 58 unitary potentials min−1 (Fig. 9B). The average of several individual responses showed that the response, like regenerative potentials, started after a delay of about 1 s and persisted for some 6 to 7 s (Fig. 9C). The amplitudes and time courses of spontaneous and evoked unitary potentials were determined. The amplitude/frequency histogram of the spontaneous unitary potentials was skewed (Fig. 9D). Many evoked unitary potentials had similar amplitudes to those occurring spontaneously but many had larger amplitudes than detected in the absence of stimulation. Larger evoked unitary potentials tended to have longer durations than did smaller evoked unitary potentials. The observations from this experiment and five other similar ones are given in Table 1. Hence depolarizing membrane potential changes increase the frequency of unitary potentials and in some way causes many of them to have larger amplitudes.

Figure 9. Effect of hyperpolarizing membrane potential changes on discharge of unitary potentials recorded from a single bundle of circular muscle that had been loaded with BAPTA.

The upper trace (A) shows the spontaneous discharge of unitary potentials. The set of three traces (Ba, b and c) shows selected responses triggered by hyperpolarizing current pulses of −2 nA. Shortly after the hyperpolarizing electrotonic potential, the frequency of unitary potentials was greatly increased. The average membrane potential change averaged over 40 successive trials is shown in C; a depolarization was triggered after a delay of 1 s and this lasted for a further 5 or 6 s. The two histograms D and E describe the amplitudes of spontaneous and evoked unitary potentials, respectively. The time calibration applies to all traces. The upper voltage calibration applies to the upper four traces, the lower voltage calibration applies to the average response in C. The membrane potential was −62 mV.

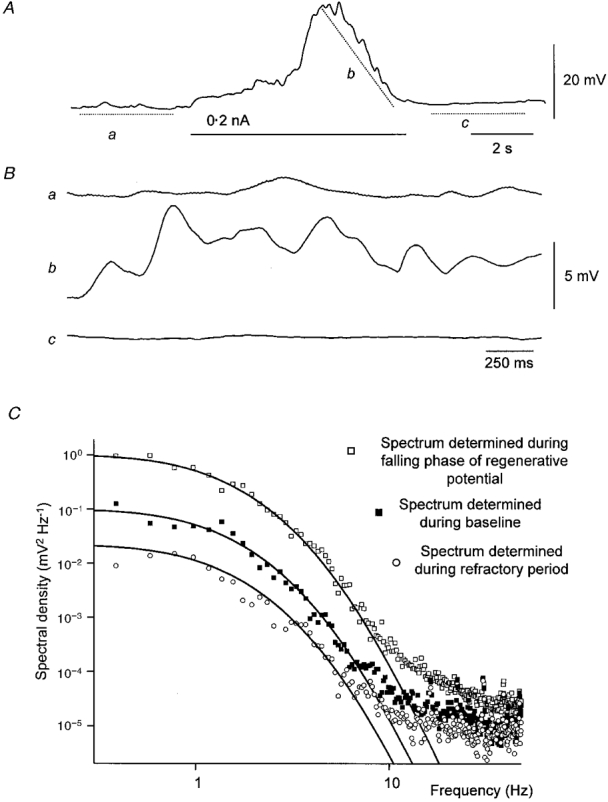

Spectral densities determined during the falling phases of regenerative potentials and the secondary components of slow waves

The previous section showed that membrane depolarization, or recovery from hyperpolarization, accelerates the frequency of occurrence and increases the amplitudes of unitary potentials. We tested the possibility that during a regenerative potential the fluctuations in the falling phase had the same frequency profile as baseline noise. Spectral density curves were constructed during rest, the falling phase of the regenerative potential and during the initial part of the refractory period which follows each regenerative potential (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999). The spectral density curves had similar temporal characteristics suggesting that common events dominated each sequence of membrane potential recordings (Fig. 10). The time constants substituted into eqn (2) (see Methods) to generate the spectral fits shown in Fig. 10 were A = 420 ms and B = 60 ms. The steepest gradient seen in the baseline region spectrum is −5.6 at about 7 Hz (−6.2 ± 0.2 at 6.5 ± 0.3 Hz, n = 4). In four preparations, the mean values of fitting time constants were A = 334± 33 ms and B = 91 ± 12 ms.

Figure 10. Spectral density curves illustrating the properties of the membrane noise detected before a regenerative potential, during its falling phase and following the regenerative potential.

The upper trace (A) shows a regenerative potential initiated by membrane depolarization (0.2 nA). The next three traces (Ba-c) show the regions of trace A selected for spectral analysis after removal of their baseline trends. The first section (Ba) represents baseline, the next (Bb) the falling phase of the regenerative potential and the following trace (Bc) the refractory period. The upper voltage and time calibrations apply to upper trace, the lower voltage and time calibrations apply to the three expanded sections of trace. The spectral densities for the three regions are shown in C. Each spectral density curve could be well described by eqn (2) using the same time constants; A, 420 ms; and B, 60 ms.

Similar analyses were applied to four preparations where myogenic activity resulted from activity arising in Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC). In these preparations, the longitudinal muscle layer was left attached. The preparations gave a regular discharge of slow waves (Fig. 11A). When caffeine (1 mM) was added to the physiological saline, the primary components of the slow waves persisted at low frequency (Fig. 11B; see also Dickens et al. 1999). These preparations had input resistances in the range 0.9–1.7 MΩ (1.4 ± 0.2 MΩ). Spectral density curves were constructed from membrane potential recordings taken during the intervals between slow waves, the falling phases of the slow waves and during the intervals between primary phases of the slow wave, recorded in caffeine (Fig. 11C). Again the spectral density curves determined during a slow wave and between slow waves had similar temporal characteristics (Fig. 11C). In this example the membrane potential obtained between the primary components of the slow waves, recorded in the presence of caffeine, failed to demonstrate an energy component that could be attributed to unitary potentials, rather a linear frequency profile was detected. Such profiles have been demonstrated in many biological membranes (membrane 1/f noise; Verveen & DeFelice, 1974): the high frequency components were found in spectral densities of the noise obtained from a typical microelectrode used in this study. The time constants used to generate the spectral fits shown in Fig. 11 were A = 375 ms and B = 125 ms. The gradient of the spectrum determined during the baseline region was steepest at about 4.5 Hz, having a value of −6 (−5.8 ± 0.5 at 6.1 ± 1.1 Hz, n = 4). In four preparations, the mean values of fitting time constants were A = 297± 31 ms and B = 93± 12 ms.

DISCUSSION

Throughout this experimental series, membrane potential changes have been recorded under a variety of conditions, which are dominated by events with the same characteristic spectral energy densities. Intracellular recordings from isolated segments of circular muscle displayed patterns of large amplitude membrane noise (Fig. 2). The spectral density curve showed that energy was largely concentrated at frequencies less than 10 Hz, showing a plateau at frequencies lower than 1 Hz and having a steep inverse dependency on frequency (Fig. 3). After loading the preparations with BAPTA, to buffer [Ca2+]i at moderately low levels, unitary potentials were detected (Fig. 2): the spectral density curve of a succession of these events had similar temporal characteristics but lower energy levels than in control conditions (Fig. 3). As the shapes of individual unitary potentials (Figs 4 and 5) could be used to predict the spectral characteristics of the noise (Fig. 3), it seems most likely that membrane noise resulted simply from the high frequency discharge of unitary events. When spectral energy densities were determined for the falling phases of regenerative potentials (Fig. 10) and the secondary components of slow waves (Fig. 11), they had identical temporal characteristics to both their own baseline recordings and those recorded in normal and BAPTA-loaded preparations (Fig. 3).

These observations suggest that unitary potentials of a more or less constant range of temporal characteristics added together to make up the voltage events in each response. At rest a discharge of unitary potentials occurs. When they occur at moderate frequencies they give rise to noisy baselines. Membrane depolarization transiently increases their frequency and their sizes. In BAPTA-loaded preparations a cluster of unitary potentials occurs, in normal preparations a regenerative potential results. Support for this idea comes from peripheral observations made during the study. Namely, caffeine blocked the discharge of evident unitary potentials, reduced membrane noise and stopped membrane depolarizations triggering regenerative potentials (Fig. 6). This occurred using lower concentrations than those found to be necessary to disrupt intracellular Ca2+ storage in other tissue, perhaps by phosphodiesterase inhibition (Tsuengo et al. 1995) or by blocking the production of inositol trisphosphate (Toescu et al. 1992). Whatever the case, the commonality of effects suggests that these three phenomena are in some way interrelated.

It could be argued that unitary potentials resulted from damage whilst the preparations were being dissected. Noise fluctuations with amplitudes described here are not a common feature of slow waves recorded from antral smooth muscle cells (Dickens et al. 1999; Suzuki & Hirst, 1999). We suggest that the detection of unitary potentials relates to the differing electrical properties of the preparations. Single bundles of circular smooth muscle had input resistances of some 5 MΩ, those with longitudinal muscle attached had input resistances of about 1 MΩ. This contrasts with the apparent input resistances of larger preparations: in these, a current of 10–20 nA is required to produce a hyperpolarization of 2–5 mV (Dickens et al. 1999). Clearly the input impedances of the preparations differ by an order of magnitude. Moreover, each regenerative potential is followed by a period where the discharge of unitary potentials is suppressed (Fig. 10). In the antrum, the membranes of circular muscle cells are regularly depolarized by the passive spread of driving potentials from ICC (Dickens et al. 1999). Thus the discharge of membrane noise during the interval between slow waves may be largely suppressed and the only time the discharge of unitary potentials would be apparent would be during the falling phase of the secondary component of the slow wave. This is commonly found to be the case when recording from antral muscle (see as an example Fig. 1 in Suzuki & Hirst, 1999).

Unitary potentials appeared to depend upon an increase in [Ca2+]i for their occurrence. They persisted in the presence of nifedipine. Their frequency was reduced when the preparations were lightly loaded with BAPTA and they were abolished with heavy loading. They had a wide range of, often-large, amplitudes and long durations. Thus it was not unusual to record a unitary potential with an amplitude of 10 mV, with the mean peak amplitude being some 1–2 mV (Table 1). The rising phases, half-widths and final rates of decay of unitary potentials were all slow when compared with the time constant of the individual preparations (Table 1), indicating that inward current flow persists throughout much of the potential change. During a mean unitary potential the peak current must be about 400 pA (Table 1); during a large unitary potential the peak current may well exceed 3 nA. In other tissues when ‘packets’ of Ca2+ are released from internal stores and subsequently activate Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels, the ensuing currents have more uniform amplitudes (Benham & Bolton, 1986). When Ca2+-sensitive Cl− channels are activated, the ensuing transient depolarizations result from currents of the order 50–100 pA (van Helden, 1991; van Helden et al. 1996). If this represents saturation of all the Ca2+-activated K+ or Cl− selective channels in a single cell, it seems likely that larger unitary potentials recorded from antral muscle reflect the co-ordinated response of several nearby cells. Alternatively, if single cells in the antrum have several patches of Ca2+-activated ion channels, unitary potentials might reflect the co-ordinated activation of several sets of channels within the cell. Large potentials would presumably involve many sets and smaller potentials would involve fewer sets of channels.

Our observations indicate that regenerative potentials and the secondary phase of slow waves, recorded from the antral region of guinea-pig stomach, do not involve the activation of conventional voltage-dependent ion channels (see also Dickens et al. 1999; Suzuki and Hirst, 1999). Indeed a complement of ion channels required to produce long lasting membrane depolarizations of the type recorded are absent from the cells isolated from guinea-pig antrum (Noack et al. 1992). We suggest that a unitary potential results from the co-ordinated release of Ca2+ from the intracellular stores of several nearby cells. Ca2+ then have access to sets of Ca2+-activated channels which result in the net influx of positive charge. The ionic selectivity of these channels is not clear. We have recently found the reversal potential for regenerative potentials, obtained by extrapolation, is about −20 mV (G. D. S. Hirst & F. R. Edwards, unpublished observations). Since several agents which block Cl− channels have little effect on slow waves, it seems unlikely that such channels are involved (Suzuki et al. 1999). Presumably unitary potentials reflect the opening of sets of cation selective channels. We suggest that at rest, the release of Ca2+ occurs at random in a few clumps of cells. Any positive movement of the membrane potential increases the likelihood that Ca2+ will be released from intracellular stores. It is unlikely that the potential changes directly co-ordinate the release of more Ca2+. Because of the slow onset of the responses, it seems more likely that an enzyme such as phospholipase C is activated. This results in the production of a second messenger which triggers the more or less synchronous occurrence of many unitary potentials. Subsequently many unitary potentials sum together to give a regenerative potential with a reversal potential of −20 mV. During this secondary phase of a slow wave, entry of Ca2+ via CaL channels occurs, but the membrane potential change contributed by these channels is small (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999).

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Drs Narelle Bramich and Hikaru Hashitani, Emma Dickens and Damian Wallace for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This project was supported by a grant from the Australian NH&MRC.

References

- Anderson CR, Stevens CF. Voltage clamp analysis of acetylcholine produced end-plate current fluctuations at frog neuromuscular junction. The Journal of Physiology. 1973;235:655–691. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham CD, Bolton TB. Spontaneous transient outward currents in single visceral and vascular smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. The Journal of Physiology. 1986;381:385–406. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramich NJ, Hirst GDS. Sympathetic neuroeffector transmission in the rat anococcygeus muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:101–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.101aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens EJ, Hirst GDS, Tomita T. Identification of rhythmically active cells in guinea-pig stomach. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;514:515–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.515ae.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin J. Some methods of constructing exact tests. Biometrika. 1961;48:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Edwards FR. Spontaneous and neurally activated depolarization in smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig urethra. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;514:459–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.459ae.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, van Helden DF, Suzuki H. Properties of spontaneous depolarizations in circular smooth muscle cells of rabbit urethra. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;118:1627–1632. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, Klemm MF, Edwards FR, Hirst GDS. Sympathetic transmission to the dilator muscle of the rat iris. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1993;425:107–123. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90123-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst GDS, Neild TO. Some properties of spontaneous excitatory junction potentials recorded from arterioles of guinea-pig. The Journal of Physiology. 1980;303:43–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Kluppel M, Malysz J, Mikkelsen HB, Bernstein A. W/Kit gene required for intestinal pacemaker activity. Nature. 1995;373:347–349. doi: 10.1038/373347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. The statistical nature of the acetylcholine potential and its molecular components. The Journal of Physiology. 1972;224:665–699. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;217:C435–454. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YW. Statistical Theory of Communications. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Noack T, Deitmer P, Lammel E. Characterization of membrane currents in single smooth muscle cells from the guinea-pig antrum. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;451:387–417. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacaud P, Bolton TB. Relation between muscarinic receptor cationic current and intestinal calcium in guinea-pig jejunal smooth muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;441:447–499. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press WH, Flannery BP, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT. Numerical Recipes in C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders KM. Ionic mechanisms of electrical rhythmicity in gastrointestinal smooth muscles. Annual Review of Physiology. 1992;54:439–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.54.030192.002255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders KM. A case for interstitial cells of Cajal as pacemakers and mediators of neurotransmission in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:492–515. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TK, Reed JB, Sanders KM. Origin and propagation of electrical slow waves in the circular layer of canine colon. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;252:C215–224. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.252.2.C215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Hirst GDS. Regenerative potentials evoked in circular smooth muscle of the antral region of guinea-pig stomach. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:563–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0563t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Yamamoto Y, Hirst GDS. Properties of spontaneous activity in gastric smooth muscle. Korean Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1999;3:119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Toescu EC, O'Neill SC, Petersen OH, Eisner DA. Caffeine inhibits the agonist-evoked cytosolic Ca2+ signal in mouse pancreatic acinar cells by blocking inositol trisphosphate production. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:23467–23470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita T. Electrical activity (spikes and slow waves) in gastrointestinal smooth muscles. In: Bülbring E, Brading AF, Jones AW, Tomita T, editors. Smooth Muscle: An Assessment of Current Knowledge. London: Edward Arnold; 1981. pp. 127–156. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuengo M, Huang S-M, Pang Y-W, Chowdhury JU, Tomita T. Effects of phosphodiesterase inhibitors on spontaneous electrical activity (slow waves) in guinea-pig gastric muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;485:493–502. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Helden DF. Spontaneous and noradrenaline induced transient depolarizations in the smooth muscle of guinea-pig mesenteric vein. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;437:543–562. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Helden DF, von der Weid P-Y, Crowe MJ. Intracellular Ca2+ release: A basis for electrical pacemaking in lymphatic smooth muscle. In: Bolton TB, Tomita T, editors. Smooth Muscle Excitation. London: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 355–374. [Google Scholar]

- Verveen AA, DeFelice LJ. Membrane noise. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 1974;28:189–265. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(74)90019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SM, Burns AJ, Torihashi S, Sanders KM. Mutation of the proto-oncogene c-kit blocks development of interstitial cells and electrical rhythmicity in murine intestine. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;480:91–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]