Abstract

The purpose of these experiments was to examine the mechanisms by which either co-activation or independent activation of tongue protrudor and retractor muscles influence upper airway flow mechanics. We studied the influence of selective hypoglossal (XIIth) nerve stimulation on tongue movements and flow mechanics in anaesthetized rats that were prepared with an isolated upper airway. In this preparation, both nasal and oral flow pathways are available.

Inspiratory flow limitation was achieved by rapidly lowering hypopharyngeal pressure (Php) with a vacuum pump, and the maximal rate of flow (VI,max) and the nasopharyngeal pressure associated with flow limitation (Pcrit) were measured. These experimental trials were repeated while nerve branches innervating tongue protrudor (genioglossus; medial XIIth nerve branch) and retractor (hyoglossus and styloglossus; lateral XIIth nerve branch) muscles were stimulated either simultaneously or independently at frequencies ranging from 20-100 Hz. Co-activating the protrudor and retractor muscles produced tongue retraction, whereas independently activating the genioglossus resulted in tongue protrusion.

Co-activation of tongue protrudor and retractor muscles increased VI,max (peak increase 44 %, P < 0.05), made Pcrit more negative (peak decrease of 44 %, P < 0.05), and did not change upstream nasopharyngeal resistance (Rn). Independent protrudor muscle stimulation increased VI,max (peak increase 61 %, P < 0.05), did not change Pcrit, and decreased Rn (peak decrease of 41 %, P < 0.05). Independent retractor muscle stimulation did not significantly alter flow mechanics. Changes in Pcrit and VI,max at all stimulation frequencies were significantly correlated during co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles (r2= 0.63, P < 0.05), but not during independent protrudor muscle stimulation (r2= 0.09).

These findings indicate that either co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles or independent activation of protrudor muscles can improve upper airway flow mechanics, although the underlying mechanisms are different. We suggest that co-activation decreases pharyngeal collapsibility but does not dilate the pharyngeal airway. In contrast, unopposed tongue protrusion dilates the oropharynx, but has a minimal effect on pharyngeal airway collapsibility.

Electromyographic recordings in animal models indicate that tongue protrudor (genioglossus, GG) and retractor muscles (styloglossus, SG; hyoglossus, HG) are co-activated during inspiration (Yasui et al. 1993, Fregosi & Fuller, 1997). Moreover, recent experiments indicate that respiratory-related co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles results in retraction of the tongue (Fregosi & Fuller, 1997; Fuller et al. 1998). The observation that tongue muscle co-activation causes retraction of the tongue implies that respiratory-related tongue-motor activity narrows, rather than dilates, the oropharynx. However, two groups of investigators have shown that co-activation of the protrudor and retractor muscles evoked by XIIth nerve stimulation results in increased inspiratory flow rates in obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) patients, in spite of clear tongue retraction (Eisele et al. 1997; De Backer et al. 1998). Protrusion of the tongue, evoked by either medial XIIth nerve branch stimulation (Eisele et al. 1997) or direct GG muscle stimulation (Schwartz et al. 1996) is also associated with increased inspiratory flow rates in human subjects. These observations suggest that either co-activation of tongue protrudor and retractor muscles, or independent protrudor muscle activation will improve pharyngeal flow mechanics. This is in spite of the fact that the tongue retracts during co-activation, and protrudes during unopposed GG contraction.

To examine the mechanisms by which both co-activation and independent activation of the protrudor and retractor tongue muscles influence upper airway flow mechanics, we have developed a modification of the experimental model of Schwartz and colleagues (Schwartz et al. 1993). Our preparation allows quantification of both axial tongue movements and pharyngeal flow mechanics while muscle nerves to tongue protrudor and retractor muscles are stimulated simultaneously or selectively. In contrast to previous investigations (Schwartz et al. 1993; Eisele et al. 1995), we elected to leave the mouth of the animal open, enabling quantification of axial tongue movements as well as permitting flow to be oral, nasal, or oronasal. Our hypothesis was that co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles will decrease the collapsibility of the pharyngeal airway, resulting in higher flow rates at any given transmural pressure. Implicit in this hypothesis is the concept that tongue protrusion (and dilation of the pharyngeal airway) is not required to improve pharyngeal flow mechanics. The hypothesis was retained, and the implications of our results for maintenance of pharyngeal airway patency in the intact animal are discussed.

METHODS

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Arizona approved all experimental methods. We studied 16 male rats weighing 239-400 g. Rats were initially anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of urethane (1.3 g kg−1), and a subcutaneous injection of atropine sulphate (0.5 mg kg−1) was given to reduce airway secretions. Rectal temperature was monitored with a thermistor and maintained at 38°C with a servo-controlled heating lamp (Yellow Springs Instruments, Model 73ATD). Surgery was not performed until the animal was non-responsive to deep pressure applied to the paws and tail with a haemostat. Subsequently, the depth of anaesthesia was monitored by periodically repeating this manoeuvre and administering supplemental urethane if needed (0.3 g kg−1). Rats were supine throughout all procedures and experiments, and were killed at the conclusion of the experiments with an overdose of sodium pentobarbitone (200 mg kg−1).

Hypoglossal nerve stimulation

The medial and lateral branches of the XIIth nerve were exposed bilaterally using a ventral approach (Gilliam & Goldberg, 1995), and bathed in mineral oil. Nerves were stimulated using bipolar hook electrodes (diameter 0.5 mm) with an interelectrode distance of approximately 2 mm. The hook electrodes were mounted on a micromanipulator and connected to a constant current stimulus isolation unit (Grass, model PSIU6) and a Grass model S48 stimulator. If the protocol required co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles, the XIIth nerves were stimulated proximal to the bifurcation into medial and lateral branches. When it was necessary to activate protrudor or retractor muscles independently of one another, the medial or lateral XIIth nerve branches, respectively, were stimulated (Fuller et al. 1998). To prevent spontaneous or respiratory-related tongue muscle contraction, the XIIth nerves were crushed proximal to the stimulating electrodes.

Measurement of tongue force

The forces associated with axial tongue movement (i.e. protrusion and retraction) were measured as previously described (Fuller et al. 1998). Briefly, a thread was sewn through the anterior tip of the midline frenulum of the tongue and connected to an isometric force transducer. Retraction of the tongue loaded the transducer, and protrusion unloaded the transducer. To enable measurement of protrusion force, tension must be present in the line connecting the tip of the tongue to the force transducer. The tension was set according to two criteria: first, protrusion and retraction forces had to be clearly discernible during medial and lateral XIIth branch stimulation, respectively; second, we attempted to leave the tongue as close to its ‘natural’ position as possible. The intent was not to accurately determine the absolute magnitude of the tongue force during XIIth nerve stimulation, as this has been studied previously in detail (Gilliam & Goldberg, 1995; Fuller et al. 1998). Rather, our aim was to clearly demonstrate the direction of axial tongue movements without introducing an artifact into the pressure and flow recordings. Attaching the tongue to the force transducer did influence the pressure and flow recordings, primarily during lateral XIIth branch stimulation (independent activation of the retractor muscles). When the tongue was not attached to the force transducer, lateral XIIth stimulation caused a reduction in V̇I,max and a more positive Pcrit. In contrast, during trials with the tongue attached to the force transducer, lateral XIIth stimulation resulted in small increases in V̇I,max and a more negative Pcrit (Table 1). We suspect that when the tongue was attached to the force transducer, the retractor muscles were required to work against the transducer, and the resulting isometric contractions enhanced the ability of the retractor muscles to ‘stiffen’ the airway. Also, the force transducer prevented the tongue from retracting to a degree that would obstruct flow. Due to these observations, all experiments were done both with and without the tongue attached to the force transducer (Table 1), and the data collected with the tongue attached to the force transducer are used solely to document axial tongue movements.

Table 1.

The mean ‘peak response’ of all major variables during whole, medial and lateral XIIth nerve stimulation both with and without the tongue attached to the force transducer

| Tongue not attached to transducer | Tongue attached to transducer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole XIIth stimulation (Co-activation) | Medial XIIth stimulation (Protrudor activation) | Lateral XIIth stimulation (Retractor activation) | Whole XIIth stimulation (Co-activation) | Medial XIIth stimulation (Protrudor activation) | Lateral XIIth stimulation (Retractor activation) | ||

| Tongue | Direction | Retraction | Protrusion | Retraction | Retraction | Protrusion | Retraction |

| movements | Force (mN) | – | – | – | 346 ± 56 | 15 ± 2 | 563 ± 80 |

| V̇I,max(ml s−1) | Control | 26.7 ± 3.9 | 30.0 ± 5.4 | 31.9 ± 3.6 | 28.4 ± 4.1 | 32.3 ± 5.2 | 36.9 ± 5.2 |

| XIIth stim. | 38.5 ± 4.9 | 48.4 ± 4.9 | 29.6 ± 4.1 | 46.0 ± 7.2 | 58.0 ± 12.4 | 43.4 ± 7.4 | |

| % change | +44.2 * | +61.3 * | −7.2 | +62.0 * | +79.6 * | +17.6 | |

| Pcrit(cmH2O) | Control | −18.9 ± 2.7 | −17.8 ± 2.9 | −16.5 ± 2.5 | −16.2 ± 2.5 | −16.8 ± 2.9 | −15.9 ± 2.3 |

| XIIth stim. | −27.3 ± 4.4 | −17.1 ± 3.5 | −12.3 ± 2.0 | −26.0 ± 4.5 | −16.9 ± 2.9 | −18.4 ± 3.1 | |

| % change | −44.4 * | +3.9 | +25.5 | −60.5 * | — | −15.7 | |

| Rn(cmH2O/(ml s−1)) | Control | 0.65 ± 0.10 | 0.77 ± 0.16 | 0.61 ± 0.12 | 0.69 ± 0.18 | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 0.54 ± 0.11 |

| XIIth stim. | 0.77 ± 0.15 | 0.51 ± 0.13 | 0.50 ± 0.12 | 0.71 ± 0.19 | 0.49 ± 0.11 | 0.50 ± 0.87 | |

| % change | +18.5 | −30.5 * | −18.0 | +2.9 | −26.9 * | −7.4 | |

Each variable was assessed at the XIIth nerve stimulation frequency that resulted in the highest V̇I,max(the ‘peak response’). In most cases, the peak V̇I occurred in the range of 60–100 Hz. For a more detailed description, see Methods

Significantly different from control

Isolated upper airway

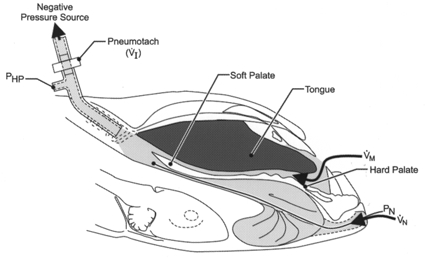

We created an isolated upper airway preparation similar to that described by Schwartz et al. (1993) (Fig. 1). The trachea was cannulated caudal to the larynx and the animals were mechanically ventilated with 100 % O2 throughout the experiments. The oesophagus was ligated dorsal to the tracheostomy tube, at the level of the larynx. The tip of a PE-200 catheter was placed approximately 1 cm rostral to the glottis, and carefully tied in place. This ‘hypopharyngeal’ catheter was connected in series to a Coulbourn pressure transducer (model T42-11), a pneumotach (Hans-Rudolph, model 8411), and a negative pressure source (commercially available vacuum cleaner). The pneumotach was connected to a differential pressure transducer (Validyne, model DP45-28) to enable measurement of flow rate (V̇I) across the isolated upper airway. A saline filled catheter (PE-60) was inserted into one nostril and connected to a pressure transducer (Statham, model P23XL). The tip of the nasal catheter was placed approximately 1 mm upstream (i.e. rostral) to the flow limiting segment (FLS) of the pharyngeal airway, which was identified as described below. It is important to emphasize that the mouth of the animal was not sealed in our model, as has been the case in most previous animal studies of upper airway flow mechanics using isolated upper airway preparations (Schwartz et al. 1993; Eisele et al. 1995). To examine if this feature of the model was responsible for discrepancies between our results and those of previous investigators (Schwartz et al. 1993; Eisele et al. 1995), the experimental protocol (see below) was repeated in three rats. In these three experiments, airflow mechanics were examined both with and without the mouth tightly sealed.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the experimental model used to study isolated upper airway flow mechanics.

The maximal rate of airflow (V̇I,max) and the nasopharyngeal pressure associated with flow limitation (Pcrit) were measured by rapidly lowering hypopharyngeal pressure (Php) with a vacuum pump. In this preparation, both the nasal and oral airflow pathways were available (see text for explanation). Pn, nasopharyngeal pressure; V̇I, airflow rate; Vm, oral airflow;Vn, nasal airflow.

Identification of the flow limiting segment of the pharyngeal airway and measurement of pharyngeal flow mechanics

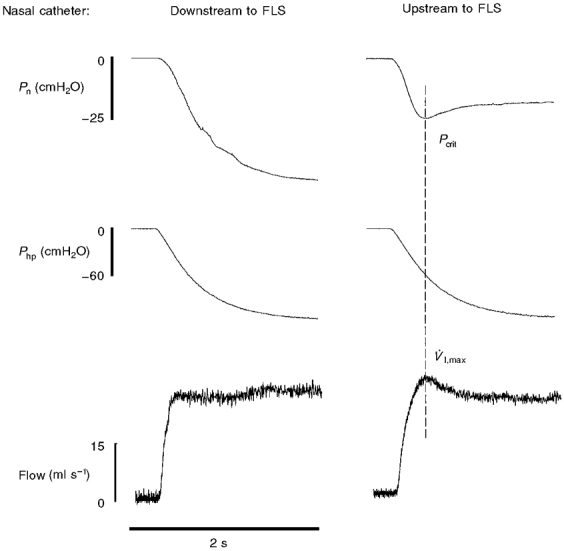

Maximum inspiratory flow rate (V̇I,max) was determined by rapidly lowering the downstream pharyngeal pressure (Php) with the vacuum pump. At the onset of flow limitation V̇I,max was measured, and this was defined as the nadir in V̇I that occurred despite further decreases in Php (see Fig. 2). The rate of decrease in Php was set such that V̇I,max occurred in < 0.5 s. The naso-pharyngeal pressure (Pn) associated with the onset of flow limitation was defined as Pcrit (Fig. 2). The location of the flow-limiting segment of the isolated pharyngeal airway (FLS) was determined by advancing the nasal catheter in 5 mm increments beginning at the external nares. At each increment, V̇I,max, Php and Pn were recorded. As shown in the left panel of Fig. 2, once the Pn catheter tip was positioned downstream to a discrete site of flow limitation, Php and Pn decreased in parallel following the onset of flow limitation. Subsequently, the catheter was withdrawn in 1 mm increments until Pn reached a nadir coincident with V̇I,max, indicating that the tip of the catheter was upstream to the FLS (Fig. 2, right panel). The catheter was left in this position for the duration of the experiment. In all animals, the location of the FLS was between 30 and 40 mm from the external nares. At the end of two experiments, dissection revealed that the tip of the Pn catheter was located in the velopharyngeal airway, approximately 2 mm upstream to the rim of the soft palate.

Figure 2. Sample record demonstrating the technique used to determine placement of the nasopharyngeal catheter, and to establish Pcrit.

In the left panel, the tip of the nasal catheter was placed downstream, or caudal, to the flow-limiting segment (FLS) of the pharyngeal airway. Note that once flow limitation occurs (i.e. V̇I,max), Pn and Php continue to drop in parallel. When the nasal catheter is moved upstream (i.e. rostral) to the FLS (right panel), nasal pressure (Pn) nadirs at V̇I,max. This nadir in Pn associated with the onset of flow limitation is defined as Pcrit. The nasopharyngeal catheter was placed upstream to the FLS during all experiments (see text for explanation).

Nasopharyngeal resistance upstream to the FLS (Rn) was calculated using the equation provided by Schwartz et al. (1993) (V̇I,max= (Pn - Pcrit)/Rn), where Pn is the pressure at the external nares, and is considered to be atmospheric. As discussed above, the mouth was not sealed in these experiments, and this may have influenced our ability to accurately measure Rn. In the current preparation, all measurements of airflow represent some combination of oral and nasal flow. Thus, calculations of upstream resistance were made by dividing nasopharyngeal pressure (cmH2O) by total airflow (i.e. oral plus nasal airflow, in ml s−1), but the ratio of oral:nasal flow was not known. Nevertheless, the changes in Rn reported here are consistent with what might be predicted based on observed changes in V̇I,max and Pcrit, which increases our confidence that this methodological concern had a minimal influence on our calculated Rn values.

Experimental protocol

After identifying the FLS, V̇I,max and Pcrit were determined with and without (i.e. control) XIIth nerve stimulation at frequencies of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 Hz, in random ascending or descending order. In all cases two trials were performed at control and at each stimulation frequency. Nerve stimulation was initiated 1 s prior to activation of the vacuum pump, and maintained for 5 s. The above protocol was performed three times in each rat as follows: (1) intact whole XIIth nerve stimulation (co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles); (2) medial XIIth nerve branch stimulation (independent GG activation) and (3) lateral XIIth nerve branch stimulation (independent retractor stimulation). These experiments were done with and without the tongue attached to the force transducer. Thus, a total of six experimental protocols were performed in each animal.

Analyses

Differences between conditions (e.g. whole XIIth vs. medial XIIth nerve stimulation, etc.) and within a condition (e.g. control vs. 60 Hz stimulation), as well as trials with the tongue attached and not attached to the force transducer, were determined using a two-way analysis of variance procedure and the Student-Newman- Keuls post-hoc test. Linear regression was used to examine the relationship between V̇I,max and Pcrit over the range of stimulation frequencies. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. All data are presented as means ± 1 s.e.m..

RESULTS

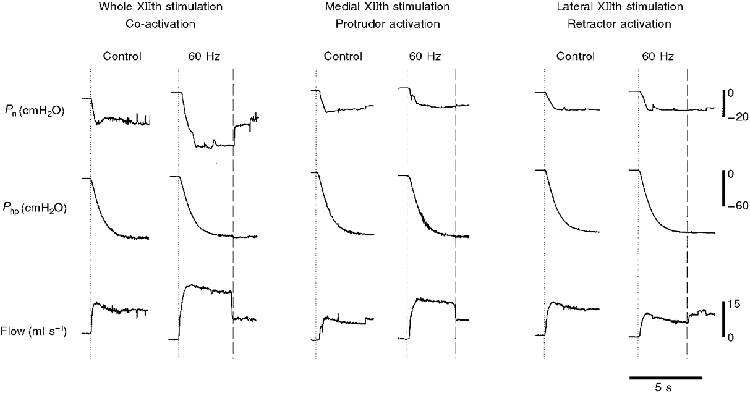

Representative pressure and flow recordings for experiments in which the tongue was not attached to the force transducer are shown in Fig. 3. Whole XIIth stimulation at 60 Hz (i.e. co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles) resulted in a more negative Pcrit and a higher V̇I,max (Fig. 3, left panels). Note the close correspondence between the nasal pressure trace and the flow trace during both control and stimulation trials, which suggests that the great majority (if not all) of the flow was nasal. The middle panels of Fig. 3 demonstrate that medial XIIth stimulation (i.e. activating protrudors but not retractors) also increases V̇I,max, but has minimal influence on Pcrit. Note that flow rate and nasopharyngeal pressure do not change in parallel during medial XIIth nerve stimulation, indicating that the increase in flow was primarily oral. The right panels of Fig. 3 show that stimulation of the retractor muscles (lateral XIIth stimulation) reduces V̇I,max, but has little effect on nasopharyngeal pressure. Note that when nerve stimulation was stopped (vertical dashed line in each panel), the rate of flow returned to the control level in each experiment.

Figure 3. Representative record of Pn, Php and VI during whole, medial and lateral XIIth nerve stimulation.

The dotted lines represent the point where the vacuum pump was turned on; the dashed lines indicate the point where XIIth nerve stimulation stopped. In these trials the tongue was not attached to the force transducer. Note that while both whole and medial XIIth nerve stimulation resulted in increased V̇I,max, only whole nerve stimulation lowered Pcrit significantly. Lateral XIIth nerve branch stimulation reduced V̇I,max, but did not influence Pcrit.

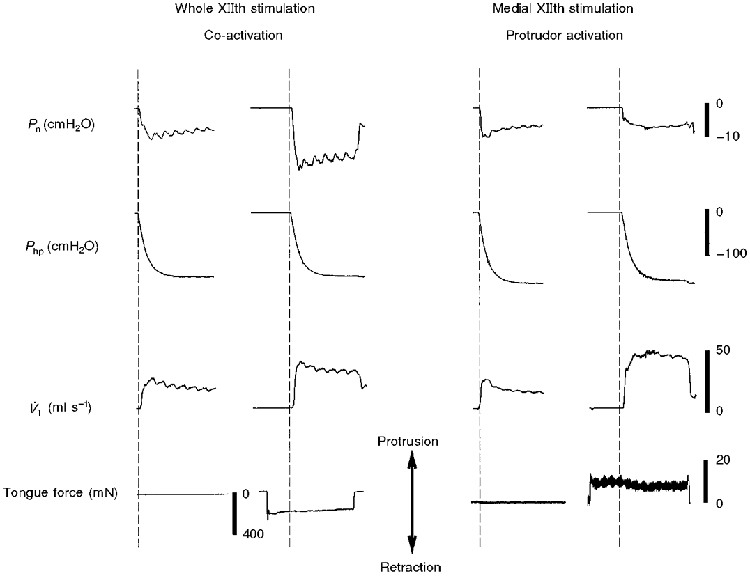

Figure 4 shows representative tracings of the effect of XIIth nerve stimulation on pressure and flow recordings for trials in which the tongue was attached to the force transducer (see Methods). Most importantly, note that the tongue retracted during whole XIIth nerve stimulation, and protruded during medial XIIth stimulation. Despite the observed retraction force during whole XIIth nerve stimulation (Fig. 4, left panel), V̇I,max increased and Pcrit was more negative, relative to control values. The right panel of Fig. 4 shows that medial XIIth stimulation causes tongue protrusion and an increase in V̇I,max with little change in Pcrit. This response is qualitatively the same as that observed in the tongue unattached trials (Fig. 3, right panel).

Figure 4. Representative record of Pn, Php, VI and tongue force during whole and medial XIIth nerve stimulation.

For these trials, the tongue was attached to the force transducer as described in Methods. Whole XIIth nerve stimulation produced an increase in V̇I,max and a more negative Pcrit, despite tongue retraction. In contrast, medial XIIth nerve stimulation caused tongue protrusion as well an increased V̇I,max, with no change in Pcrit.

The peak responses of tongue force, V̇I,max, Pcrit, and Rn during XIIth nerve stimulation trials both with and without the tongue attached to the force transducer are presented in Table 1. Co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles always resulted in a retraction force, whereas stimulation of the protrudor muscles independent of the retractors always caused tongue protrusion. Consistent with Fig 3 and Fig 4, both whole and medial XIIth stimulation resulted in increased V̇I,max, however only whole XIIth stimulation caused a more negative Pcrit. Conversely, medial XIIth stimulation produced a decrease in Rn, whereas whole XIIth stimulation did not alter Rn. The influence of XIIth stimulation frequency on V̇I,max, Pcrit, and Rn is shown in Fig. 5. During medial and whole XIIth nerve stimulation, increases in V̇I,max did not achieve statistical significance until stimulation frequencies reached 60 Hz. Medial XIIth nerve stimulation did not alter Pcrit at any stimulation frequency, whereas whole XIIth nerve stimulation significantly lowered Pcrit at frequencies ≥ 60 Hz. Changes in Rn during XIIth stimulation were variable, and did not reach statistical significance with one exception (whole XIIth stimulation, 100 Hz). As shown in Table 1, however, the decrease in Rn occurring at the stimulation frequency which resulted in peak V̇I,max achieved statistical significance during medial XIIth stimulation.

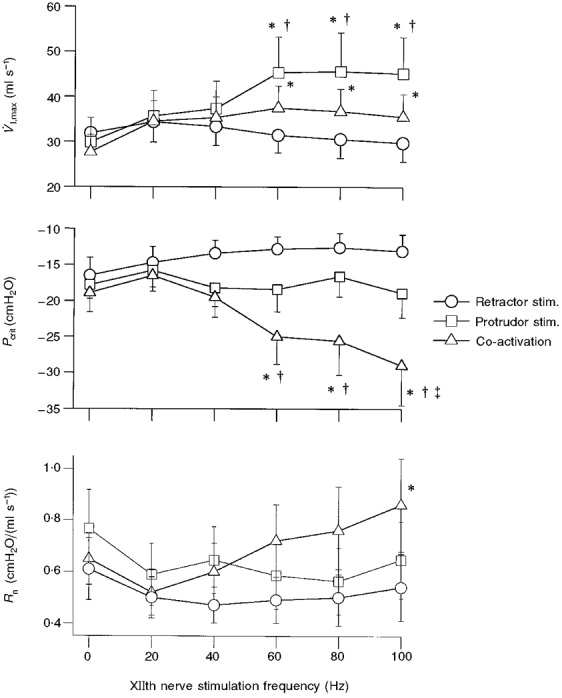

Figure 5. Influence of XIIth nerve stimulation frequency on V̇I,max, Pcrit and Rn.

These data were obtained during trials in which the tongue was not attached to the force transducer. Note that co-activation of the tongue protrudors and retractors at frequencies > 40 Hz caused a significantly more negative Pcrit, whereas independent stimulation of tongue protrudors and retractors did not influence Pcrit. * Significantly different from control (0 Hz); † significantly different from retractor muscle response at that frequency; ² significantly different from protrudor muscle response at that frequency.

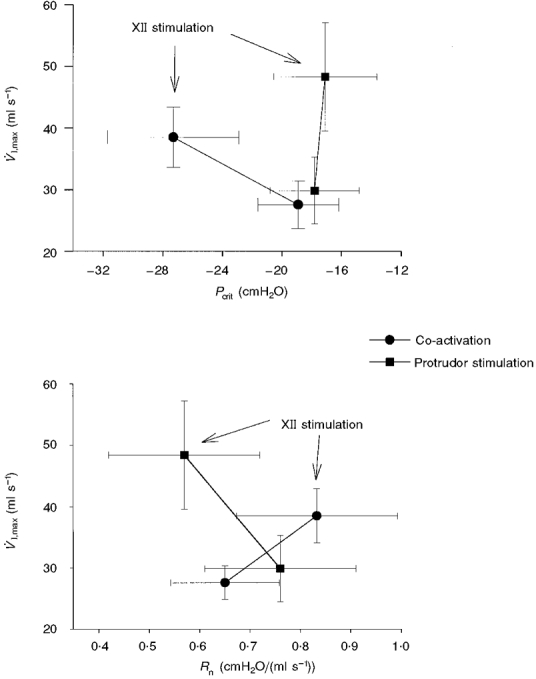

The relationship between the control values of V̇I,max and Pcrit and the peak response recorded during either whole or medial XIIth branch stimulation is shown in Fig. 6 (top panel). Co-activation of the tongue protrudor and retractor muscles resulted in a more negative Pcrit, and an increased V̇I,max, suggesting a cause and effect relationship between these two variables. That is, the more negative Pcrit indicates that the pharyngeal airway was able to withstand a greater transmural pressure before flow became limited. In contrast, protrudor muscle stimulation resulted in an increased V̇I,max, with no effect on Pcrit (Fig. 6, top panel). Thus, increases in V̇I,max during medial XIIth stimulation were most likely due to decreased oro- and/or nasopharyngeal airflow resistance. The lower panel of Fig. 6 supports this conclusion by demonstrating that peak increases in V̇I,max during medial XIIth stimulation were associated with decreased Rn. Pcrit and V̇I,max across all stimulation frequencies were correlated significantly during whole XIIth stimulation (r2= 0.63, P < 0.05), but not during medial XIIth nerve branch stimulation (r2= 0.09).

Figure 6. Changes in V̇I,max as a function of Pcrit (top panel) and Rn (bottom panel), both with and without stimulation of the whole hypoglossal nerves (co-activation) or the medial branches (protrudor stimulation).

The data labelled ‘XII stimulation’ represent the peak response observed across all stimulation frequencies (see Methods). Independent protrudor muscle stimulation caused an increase in V̇I,max with no change in Pcrit (top panel) and a lower Rn (bottom panel). In contrast, the increase in V̇I,max evoked by co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles was associated with a more negative Pcrit (top panel) and an increased Rn (bottom panel).

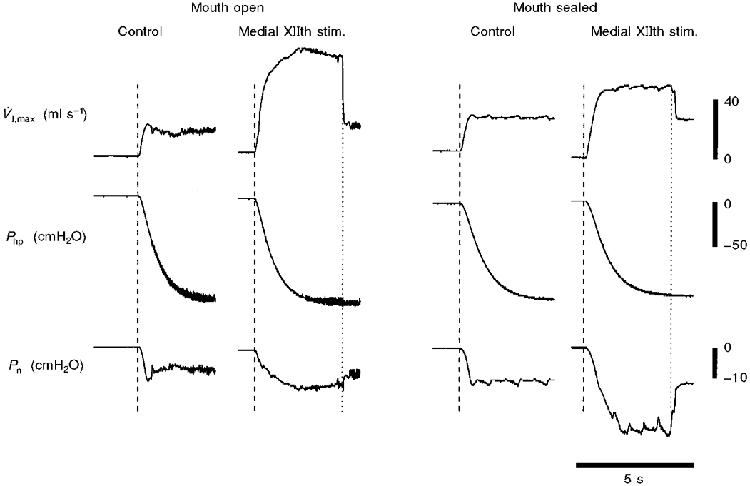

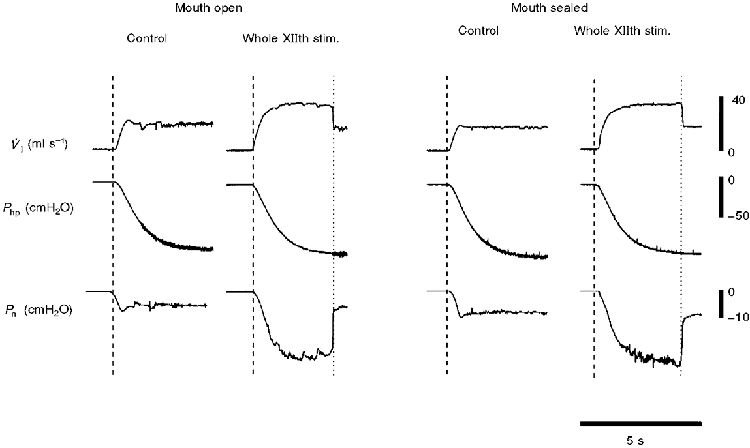

Examples of the influence of sealing the mouth (and eliminating the oral flow pathway) on airflow mechanics are presented in Fig 7 and Fig 8. As indicated in Methods, these supplemental experiments were intended to determine if differences in methodology were responsible for the discrepancies between our results and those of previous investigators (Schwartz et al. 1993; Eisele et al. 1995). Consistent with Figs 3–6, Fig. 7 demonstrates that stimulating the medial branch of the XIIth nerve resulted in increased V̇I,max and no change in Pcrit, when the mouth was open (left panel). When the mouth was sealed, however, medial XIIth nerve branch stimulation resulted in a more negative Pcrit, and a much smaller change in V̇I,max (Fig. 7, right panel). In contrast, sealing the mouth had no influence on the pressure and flow responses to whole XIIth nerve stimulation (Fig. 8). The mean data from these three experiments are shown in Table 2.

Figure 7. Representative record demonstrating the influence of sealing the mouth on pharyngeal airflow mechanics during medial XIIth nerve stimulation.

V̇I,max and Pcrit were initially determined during 60 Hz stimulation of the medial branches of both XIIth nerves with the mouth open (left panel). The mouth was then sealed, and V̇I,max and Pcrit were again determined during 60 Hz medial XIIth nerve stimulation (right panel). Note that when the mouth was open, medial XIIth stimulation caused a large increase in V̇I,max, with no change in Pcrit (indicating the majority of the increase in airflow is oral). In contrast, once the mouth had been sealed (eliminating the oral flow pathway), medial XIIth nerve stimulation caused a significantly more negative Pcrit, and a much smaller increase in V̇I,max.

Figure 8. Representative record demonstrating the influence of sealing the mouth on pharyngeal airflow mechanics during whole XIIth nerve stimulation.

V̇I,max and Pcrit were initially determined during 60 Hz stimulation of both whole XIIth nerves, with the mouth open (left panel). The mouth was then sealed, and V̇I,max and Pcrit were again determined during 60 Hz stimulation of the whole XIIth nerves (right panel). In contrast with the effect of sealing the mouth on the response to medial XIIth nerve stimulation (Fig. 7), the response of Pcrit and V̇I,max to whole XIIth nerve stimulation was the same whether or not the mouth was sealed. These data indicate that the majority of the changes in airflow during whole XIIth nerve stimulation was nasal.

Table 2.

Data demonstrating the influence of sealing the mouth on pharyngeal flow mechanics during selective XIIth nerve stimulation in three animals

| Medial XIIth stimulation | Whole XIIth stimulation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouth open | Mouth sealed | Mouth open | Mouth sealed | ||

| V̇I,max (ml s−1) | Control | 28.0 ± 7.1 | 22.9 ± 4.9 | 27.6 ± 0.28 | 20.7 ± 3.7 |

| XIIth stim. | 68.8 ± 13.2 | 46.7 ± 8.4 | 48.1 ± 4.7 | 47.8 ± 2.1 | |

| % change | +145* | +104 | +74 | +131 | |

| Pcrit (cmH2O) | Control | −22.0 ± 4.9 | −23.1 ± 6.2 | −21.4 ± 6.1 | −22.4 ± 8.9 |

| XIIth stim. | −26.5 ± 6.9 | −41.5 ± 17.7 | −48.1 ± 24.4 | −49.8 ± 30.2 | |

| % change | −20 | −80 | −125 | −122 | |

| Rn (cm2O/(ml s−1)) | Control | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 0.78 ± 0.23 | 1.03 ± 0.24 |

| XIIth stim. | 0.44 ± 0.19 | 0.86 ± 0.30 | 1.06 ± 0.61 | 1.02 ± 0.58 | |

| % change | −47 | −14 | +36 | −1 | |

Each variable was assessed during control trials and at the XIIth nerve stimulation frequency that resulted in the peak V̇I,max (see Methods, Results and legend to Table 1 for details).

Significantly different from control.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that both independent tongue protrudor stimulation and co-activation of tongue protrudor and retractor muscles can improve upper airway flow mechanics, but by different mechanisms. Despite causing tongue retraction, co-activation of the protrudor and retractor muscles resulted in increased flow rates that were associated with more negative nasopharyngeal pressures, indicating that the pharyngeal airway was more resistant to collapse. In contrast, independent protrudor muscle stimulation resulted in tongue protrusion and increased flow rates, but did not change nasopharyngeal pressure, suggesting that protrudor muscle stimulation had little influence on pharyngeal airway collapsibility. Independent stimulation of the retractor muscles resulted in strong tongue retraction, without significant change in V̇I,max or Pcrit, indicating that tongue retraction must be associated with co-activation in order to improve upper airway flow mechanics.

Critique of methods

Prior to discussing our results, several methodological concerns should be addressed. First, it is possible that pharyngeal airway movement during XIIth nerve stimulation caused movement of the FLS. Under conditions where the FLS moves upstream (i.e. rostral), overestimation of Pcrit could occur. In contrast, Pcrit may be underestimated if the FLS moves downstream (i.e. caudal) during XIIth nerve stimulation. We did not attempt to determine if movement of the FLS occurred during nerve stimulation. This decision was based on the observation that small (< 5 mm) movements of the nasopharyngeal catheter tip rostral to the FLS have only minor (i.e. 1-2 cmH2O) influences on the magnitude of Pcrit (D. D. Fuller & R. F. Fregosi, unpublished observations). Thus, although we cannot rule out FLS movement and associated changes in Pcrit during XIIth nerve stimulation, we are confident that movement of the FLS did not artifactually produce the reported Pcrit differential between medial and whole XIIth nerve stimulation. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that quantitative differences in Pcrit may have occurred as a consequence of stimulation-induced movement of the FLS. Moreover, FLS movement could potentially account for the conflicting results between the current study and prior work (Eisele et al. 1995). We feel strongly, however, that the primary reason for the different findings is based on the configuration of the mouths of the animals in the two studies, as emphasized later in the discussion. In short, Eisele et al. (1995) showed that Pcrit became negative with medial XIIth branch stimulation in cats studied with the mouth sealed, whereas in our studies (done with the mouth open) Pcrit did not change with medial XIIth branch stimulation. However, we were able to reproduce the findings of Eisele and colleagues (1995) when we repeated our experiments under conditions where the mouth was sealed (e.g. Fig. 7 and Table 2). Thus, our data clearly demonstrate that sealing the mouth of the animal has important effects on the influence of tongue muscle activation on airway mechanics. Accordingly, configuration of the mouth and jaw of the animal must be considered when interpreting the effects of tongue muscle activity on pharyngeal airway mechanics.

Second, a rat isolated upper airway model was used in these experiments, and there are clear anatomical differences between the rat and human upper airway that should be kept in mind when attempting to interpret the current results. The supine rat upper airway is relatively rectilinear along a rostral to caudal axis (Fig. 1). In contrast, the upper airway of a supine human is ‘L-shaped’, exhibiting an almost 90 deg bend from the naso- to oropharynx. Therefore, the influence of XIIth nerve stimulation on flow mechanics could be quite different between species, and this must be acknowledged. However, the innervation and mechanical actions of the tongue muscles are similar in rat and human (Warwick & Williams, 1973; Gilliam & Goldberg, 1995; Eisele et al. 1997; Fuller et al. 1998 and De Backer et al. 1998; see below). Moreover, comparison of XIIth nerve stimulation in both species indicates that the effects on upper airway flow mechanics are also similar (e.g. present data and Eisele et al. 1997). Accordingly, the rat is a useful model for initial investigations on the effects of selective XIIth nerve stimulation on upper airway flow mechanics.

Third, using the force transducer to study tongue movements influenced the flow mechanics of the upper airway, independently of XIIth nerve stimulation (Table 1). Therefore all trials were performed both with and without the tongue attached to the force transducer (see Methods). The data from the former condition were used solely to document the direction of tongue movements during XIIth nerve stimulation, while the data from the latter condition have been used to examine the mechanisms underlying changes in upper airway flow mechanics as a result of XIIth nerve stimulation. Thus, we are confident that the measurement of tongue movements did not influence our conclusions regarding upper airway flow mechanics.

A fourth concern regards the quantification of tongue movements. Securing the tongue to the force transducer enabled axial tongue movements to be quantified as either protrusive or retractive. However, the extrinsic tongue muscles can produce tongue movements that are not limited to protrusion and retraction (e.g. depression, elevation; Warwick & Williams, 1973), and our model does not allow the measurement of depression or elevation forces. Nevertheless, visual observation often revealed depression of the tongue during both selective protrudor muscle stimulation and protrudor and retractor muscle co-activation. Indeed, in mammals, including humans, depression of the tongue is a common action of both protrudor and retractor muscles (Warwick & Williams, 1973), suggesting that tongue depression plays an important role in modulating pharyngeal airway mechanics. Recent studies from our laboratory are designed to test this hypothesis, and preliminary findings support it (M. J. Brennick and R. F. Fregosi, unpublished observations). In short, we have used magnetic resonance imaging to quantify changes in pharyngeal airway geometry during selective XIIth nerve stimulation in anaesthetized rats. Data from six experiments show that co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles (whole XIIth nerve stimulation) depress the base of the tongue markedly, cause modest tongue retraction and widen the retroglossal airway. In contrast, medial XIIth branch stimulation evokes tongue depression and protrusion, and widens the oropharyngeal airway with little or no effect on the retroglossal airspace. Finally, independent stimulation of the tongue retractor muscles has little effect on pharyngeal geometry. These preliminary anatomical observations are consistent with the physiological findings reported herein.

The final methodological issue regards the degree of flexion or extension of the head of the animals. Neck flexion from 0 to 90 deg decreases V̇I,max and elevates Pcrit in the isolated canine upper airway (Odeh et al. 1995). Also, changing head and neck position may alter tongue muscle position and length. In our preparation, the rats were studied in the supine position, with 0 deg neck flexion. However, the influence of XIIth nerve stimulation on pharyngeal flow imechanics may depend on head position and further experimentation is needed to address this issue.

Mechanical influence of selective XIIth nerve stimulation

Consistent with previous reports from our laboratory (Fregosi & Fuller, 1997; Fuller et al. 1998), co-activating the protrudor and retractor muscles resulted in tongue retraction. Importantly, two groups have recently shown that co-activating the protrudor and retractor muscles via XIIth nerve stimulation in human subjects also produces tongue retraction (Eisele et al. 1997, De Backer et al. 1998), indicating that the mechanical actions of tongue protrudor and retractor muscle co-activation are similar in rats and humans. As expected, selectively activating the tongue protrudor or retractor muscles produced tongue protrusion and retraction, respectively (Hellstrand, 1980; Gilliam & Goldberg, 1995; Fuller et al. 1998).

Co-activation of tongue protrudor and retractor muscles and pharyngeal airflow mechanics

Schwartz et al. (1993), Eisele et al. (1995) and Oliven et al. (1996) examined isolated upper airway pressure-flow relationships during whole XIIth nerve stimulation (i.e. co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles). Each of these studies showed that whole XIIth nerve stimulation augmented V̇I,max and resulted in a more negative Pcrit. These consistent findings demonstrate that co-activation of tongue protrudor and retractor muscles can improve flow mechanics in the isolated upper airway. These effects have typically been attributed to decreased airway resistance and/or collapsibility, resulting from activation of the GG muscle and tongue protrusion (Schwartz et al. 1993; Hida et al. 1995; Eisele et al. 1995; Oliven et al. 1996). Such a conclusion is incompatible with the present data and previously published reports showing that whole XIIth stimulation causes tongue retraction in human subjects and animal models; thus, tongue protrusion cannot explain the improved pharyngeal mechanics observed with whole XIIth nerve stimulation. Rather, the present data suggest that co-activation of the protrudor and retractor muscles stiffens, retracts and depresses the tongue as the antagonistic muscles contract against one another, resulting in a less collapsible retroglossal airway. In the present experiments, decreased airway collapsibility was manifest as a more negative critical pressure during whole XIIth nerve stimulation. The ability to withstand more negative intraluminal pressures insured that greater transmural pressures could be achieved before the airway narrowed to the point where flow became limited. As shown in the present experiments, this leads to greater pharyngeal airflow (V̇I,max) at a given downstream driving pressure. Thus, the ability of the extrinsic tongue muscles to decrease pharyngeal airway collapsibility is enhanced when the protrudor and retractor muscles contract simultaneously and antagonistically, rather than separately.

The observation that tongue muscle co-activation produces increased airflow rates in the face of tongue retraction is not unique to the rat. Two groups have reported similar findings in human obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) patients. Eisele and colleagues (1997) found that whole XIIth nerve stimulation during inspiration caused tongue retraction and increased airflow rates in OSA patients. Subsequently, De Backer et al. (1998) reported that whole XIIth nerve stimulation decreased the frequency of apnoeic events during sleep in OSA patients despite causing tongue retraction. These results suggest that the mechanical effects of whole XIIth nerve stimulation are qualitatively the same in the rat and the human. Future experiments are needed to determine if humans co-activate the protrudor and retractor muscles during eupnoea or hyperpnoea, and if respiratory-related co-activation improves pharyngeal airflow mechanics.

In addition to the tongue retractor muscles, there are other examples of pharyngeal ‘constricting’ muscles contributing to airway patency. For example, the termination of apnoeic events in OSA patients is accompanied by an increase in superior pharyngeal constrictor EMG activity (Kuna & Smickley, 1997). Moreover, at low airway volumes, stimulation of the superior and middle pharyngeal constrictor muscles is associated with dilation of the isolated feline upper airway (Kuna & Vanoye, 1999). Kuna and colleagues hypothesize that contraction of the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscles stiffens, and under some conditions dilates the pharynx, thereby enhancing airway patency. These results, along with the present data, underscore the complex mechanical actions of the pharyngeal airway muscles. Specifically, recent data clearly indicate that activation of muscles traditionally associated with pharyngeal narrowing (e.g. pharyngeal constrictors and tongue retractors) can promote pharyngeal airway patency under some conditions.

Protrudor muscle stimulation and flow mechanics

The influence of tongue protrudor muscle stimulation on flow mechanics in OSA patients has been examined either by stimulating the medial XIIth nerve branch (Eisele et al. 1997), or the genioglossus muscle directly (Schwartz et al. 1996). Both experimental approaches produced increases in V̇I,max of approximately 200 ml s−1. Moreover, Eisele and colleagues have reported that medial XIIth nerve branch stimulation produces an 88 % increase in V̇I,max in the isolated feline upper airway (Eisele et al. 1995). Therefore, our data demonstrating increases in V̇I,max during medial XIIth nerve stimulation are consistent with previous reports in both human subjects and animal preparations.

It is well accepted that tongue protrudor muscle activation can improve upper airway flow mechanics by dilating the oropharynx and reducing flow resistance (Bartlett, 1986). It has also been suggested that GG muscle activation decreases the compliance of the pharyngeal airway (Schwartz et al. 1993; Hida et al. 1995). However, the present data indicate that independent GG muscle activation does not significantly alter the collapsibility of the pharyngeal airway. We say this because the nasopharyngeal pressure associated with the onset of flow limitation (i.e. Pcrit) was not significantly influenced by selective protrudor muscle stimulation. Therefore, in our preparation, the increases in flow observed during selective protrudor muscle stimulation were due to pharyngeal dilation and decreased oral flow resistance, and not altered pharyngeal collapsibility. Indeed, Rn was significantly lower at the stimulation frequency resulting in peak V̇I,max (Table 1).

As outlined in ‘Critique of methods’, our finding that medial XIIth nerve branch stimulation does not significantly influence Pcrit contradicts a prior report by Eisele et al. (1995), which shows that independent GG muscle activation results in a more negative Pcrit. We addressed this discrepancy by conducting the experiments shown in Figs 7 and 8, and Table 2. Similar to the results of Eisele et al. (1995) we found that medial XIIth nerve branch stimulation resulted in a higher V̇I,max and a more negative Pcrit when the mouth of the animal was sealed (Fig. 7). In contrast, when the experiments were repeated in the same animals under conditions where the mouth was open, medial XIIth stimulation increased V̇I,max markedly, but did not influence Pcrit (Fig. 7). The physiological significance of these findings is that unopposed tongue protrusion dilates, but does not alter the collapsibility of the pharyngeal airway in preparations with patent nasal and oral flow routes. Interestingly, co-activation of protrudor and retractor muscles via whole XIIth nerve stimulation evokes similar changes in V̇I,max and Pcrit whether the mouth is open or sealed (Fig. 8 and see below).

Nasal vs. oral airflow

The changes in nasopharyngeal pressure and airflow during XIIth nerve stimulation reported herein indicate that the pattern of extrinsic tongue muscle activation can influence the route of airflow (i.e. oral vs. nasal). During co-activation, changes in nasopharyngeal pressure and flow rates were significantly correlated, suggesting that the majority of flow under these conditions was nasal. In addition, sealing the mouth had no influence on the flow and pressure responses to whole XIIth nerve stimulation (Fig. 8), providing further evidence that the changes in airflow under these conditions were nasal. In contrast, changes in nasopharyngeal pressure and airflow were not significantly correlated during independent protrudor muscle stimulation. The lack of relationship between these two variables indicates that medial XIIth nerve branch stimulation dilated the oropharyngeal airway in a manner that enhanced oral airflow, with little effect on nasal flow. Moreover, in the three animals tested in this manner, sealing the mouth (and eliminating the oral flow pathway), reduced the changes in V̇I,max, Pcrit and Rn evoked by medial XIIth nerve stimulation (Fig. 7 and Table 2). Although speculative, these results suggest that co-activating the protrudor and retractor muscles may promote nasal airflow, while selectively activating the protrudor muscles may favour oral airflow. Consistent with this hypothesis, changes in oral airflow and GG EMG activity are significantly correlated during progressive intensity exercise in human subjects, and the switch from nasal to oronasal breathing during exercise is accompanied by a significant increase in inspiratory GG EMG activity (Williams et al. 1998).

Conclusion

Independent activation of the GG muscle, or co-activation of the GG with the tongue retractor muscles, results in an increase in maximal flow through the isolated pharyngeal airway of anaesthetized rats. However, the mechanisms underlying the increase in flow evoked by these two strategies are not the same. The present results suggest that activation of the GG dilates the oropharynx and promotes oral airflow, whereas co-activation of the protrudor and retractor muscles evokes a more modest increase in airflow but stiffens the airway considerably. Further studies are required to determine if co-activation of tongue muscles occurs during breathing in healthy human subjects and OSA patients, and if co-activation improves pharyngeal airway mechanics.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank The National Institutes of Health of the United States Public Health Service for supporting the studies (grant nos HL 56876 and HL 51056).

References

- Bartlett D. Upper airway motor systems. In: Cherniack NS, Widdicombe JG, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 3, The Respiratory System, Control of Breathing. II. Bethesda, MD, USA: American Physiological Society; 1986. pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- De Backer WA, Boudewyns A, Van De Heyning P. Hypoglossal nerve (HGN) stimulation using a fully implantable pulse generator: clinical experience in 2 OSA patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;157:A284. [Google Scholar]

- Eisele DW, Schwartz AR, Hari A, Thut DC, Smith PL. The effects of selective nerve stimulation on upper airway flow mechanics. Archives of Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 1995;121:1361–1364. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890120021004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisele DW, Smith PL, Alam DS, Schwartz AR. Direct hypoglossal nerve stimulation in obstructive sleep apnoea. Archives of Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 1997;123:57–61. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900010067009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregosi RF, Fuller DD. Respiratory-related control of extrinsic tongue muscle activity. Respiration Physiology. 1997;110:295–306. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(97)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Meteika JH, Fregosi RF. Co-activation of tongue protrudor and retractor muscles during chemoreceptor stimulation in the rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:265–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.265bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam EE, Goldberg SJ. Contractile properties of the tongue muscles: effects of hypoglossal nerve and extracellular motoneuron stimulation in the rat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;74:547–555. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrand E. Morphological and histochemical properties of tongue muscles in cat. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1980;110:187–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1980.tb06650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hida W, Kurosawa H, Okabe S, Kikuchi Y, Midorikowa J, Chung Y, Takishami T, Shirato K. Hypoglossal nerve stimulation affects the pressure-volume behaviour of the upper airway. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1995;151:455–460. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7842206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuna ST, Smickley JS. Superior pharyngeal constrictor activation in obstructive sleep apnoea. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1997;156:874–880. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9702053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuna ST, Vanoye CR. Mechanical effects of pharyngeal constrictor activation on pharyngeal airway function. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1999;86:411–417. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.1.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odeh M, Schnall R, Gavriely N, Oliven A. Dependency of upper airway patency on head position: the effect of muscle contraction. Respiratory Physiology. 1995;100:239–244. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(94)00135-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliven A, Odeh M, Schnall RP. Improved upper airway patency elicited by electrical stimulation of the hypoglossal nerves. Respiration. 1996;63:213–216. doi: 10.1159/000196547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AR, Eisele DW, Hari A, Testerman R, Erickson D, Smith PL. Electrical stimulation of the lingual musculature in obstructive sleep apnoea. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1996;81:643–652. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AR, Thut DC, Tuss B, Seelagy M, Yuan X, Brower RG, Permutt S, Wise RA, Smith PL. Effect of electrical stimulation of the hypoglossal nerve on airflow mechanics in the isolated upper airway. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1993;147:1144–1150. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.5.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warwick R, Williams P. Gray's Anatomy. 35. Philadelphia, USA: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1973. British. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JS, Janssen PL, Fregosi RF. Neuromuscular control of airflow through the oral and nasal passages during exercise. FASEB Journal. 1998;12:A783. [Google Scholar]

- Yasui Y, Kogo M, Iida S, Hamaguchi M, Koizumi H, Kohara H, Matsuya T. Respiratory activities in relation to external glossal muscles. Journal of the Osaka University Dental School. 1993;33:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]