Abstract

Hypoxia and metabolic inhibition with cyanide (CN) evoke catecholamine secretion in adrenal chromaffin cells through depolarization. We elucidated mechanisms for a CN- or anoxia-induced inward (depolarization) current, using the perforated patch method.

Bath application of Ba2+ induced a dose-dependent inhibition of a muscarine-induced current (IMUS) and part of the CN-induced current (ICN) with an IC50 (concentration responsible for 50 % inhibition) of 1.3 mM. The Ba2+-sensitive component was estimated to comprise 58 % of the total ICN.

The Ba2+-resistant component of ICN tended to increase with shifts of membrane potential from -40 to 40 mV and was markedly suppressed by exposure to a K+-free solution or 200 μm ouabain, indicating that the majority of the Ba2+-resistant component of ICN is due to suppression of the Na+ pump current (Ipump).

The non-Ipump component of ICN diminished progressively in K+-free solution. Substitution of glucose for sucrose in a K+-free CN solution further diminished the CN potency to produce the non-Ipump component.

The I-V relationship for the non-Ipump component of ICN had a reversal potential of -3 and -47 mV at 147 and 5.5 mM Na+, respectively, and showed an outward rectification, indicating that the non-Ipump component of ICN is due to activation of non-selective cation channels.

Exposure to anoxia induced a current with an amplitude comparable to that of ICN, and the anoxia-induced current apparently occluded development of ICN. The anoxia-induced current diminished by ca 60 % in the absence of K+ and reversed polarity at 5 mV under K+-free conditions.

It is concluded that exposure to CN and to anoxia induces suppression of the Na+ pump and activation of non-selective cation channels, probably due to an ATP decrease resulting mainly from consumption by the Na+ pump.

Hypoxia evokes catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla (Houssay & Molinelli, 1926; Bülbring et al. 1948), which allows the body to deal with life-threatening events (Lagercrantz & Bistoletti, 1977; Cryer, 1980). Recently, we (Inoue & Imanaga, 1997; Inoue et al. 1998) and others (Thompson et al. 1997; Mojet et al. 1997) reported that in addition to type I cells of the carotid body (López-Barneo, 1996), adrenal medullary cells themselves are capable of sensing a decrease of O2 tension with consequent catecholamine secretion. Both in the carotid body cell (Buckler & Vaughan-Jones, 1994; Ureña et al. 1994) and in the adrenal medullary cell (Thompson et al. 1997; Inoue et al. 1998), a hypoxia- or metabolic inhibition-induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) was found to be due to activation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels by depolarization. The mechanisms for this depolarization have remained in dispute regarding both preparations. In the rat carotid body cell, hypoxia suppressed a voltage-independent K+ channel (Buckler, 1997) or a Ca2+-dependent K+ channel (Peers, 1990; López-López et al. 1997), whereas in the rabbit carotid body cell (López-López et al. 1989; Ganfornina & López-Barneo, 1992) it inhibited voltage-dependent K+ channels. Similarly, anoxia inhibited Ca2+-dependent and voltage-dependent K+ channels in adrenal chromaffin cells obtained from newborn rats (Thompson & Nurse, 1998). On the other hand, our results (Inoue et al. 1998) suggested that metabolic inhibition with cyanide (CN), and probably hypoxia, results in activation of Na+-permeable cation channels. In addition to the discrepancy between the ion channels involved, it is also controversial how hypoxia modulates channel activity with the consequent catecholamine secretion. López-Barneo (1996) proposed the membrane ion channel hypothesis that a decrease of O2 tension is detected directly by a voltage-dependent K+ channel or by an O2 sensor closely associated with the channel molecule (Ganfornina & López-Barneo, 1992), whereas our results and those of others (Mojet et al. 1997) are consistent with the idea that dysfunction of the mitochondria is responsible for modulation of channel activity. We now find that exposure to CN and to anoxia induces suppression of the Na+ pump and activation of a non-selective cation (NS) channel, which may be the same as the muscarinic receptor-regulated channel (Inoue & Kuriyama, 1991).

METHODS

All experiments were carried out with the approval of the local ethical committee and in accordance with the institutional guidelines for animal care.

Experiments on dissociated adrenal medullary cells were done as described elsewhere (Inoue & Imanaga, 1995). Briefly, female guinea-pigs weighing 250-300 g were killed by a blow to the neck, then adrenal glands were removed and immediately put into ice-cold Ca2+-free solution in which 1.8 mM CaCl2 was simply omitted from a standard saline solution containing (mM): 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 0.53 NaH2PO4, 5 D-glucose, 5 Hepes and 4 NaOH. Adrenal medullae were cut into three to six pieces and incubated for 30 min with 0.25 % collagenase dissolved in the Ca2+-free solution. After the incubation, the tissue was washed 3 times in the Ca2+-free solution and then kept in the same solution at room temperature (23-25°C) until commencement of the experiment. A few pieces of the tissue were put in the bath apparatus placed on an inverted microscope and adrenal chromaffin cells were dissociated mechanically with fine needles. After a few minutes, during which time the dissociated cells were allowed to adhere to the bottom of the bath, the bath apparatus was perfused with standard saline solution constantly at a rate of 1 ml min−1.

The whole-cell current was recorded using the perforated patch method (Horn & Marty, 1988). The current was recorded using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments) and then fed into a brush recorder after low-pass filtering at 3 or 5 Hz, and into a videotape after digitizing using an analog-to-digital converter. The pipette solution for the perforated patch method contained (mM): 120 potassium isethionate, 20 KCl, 10 NaCl, 10 Hepes and 2.6 KOH. On the day of the experiment, nystatin was added to the pipette solution at a final concentration of 100 μg ml−1. Glucose and NaCl in the standard saline were replaced with equimolar sucrose (5 mM) and NaCN (5 mM) in the CN solution, unless otherwise stated, and 5.4 mM KCl in the standard saline or CN solutions was replaced with equimolar NaCl in each K+-free solution. KCl at 5.4 mM and 132 or 137 mM NaCl in the standard solution were replaced with 138 mM N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMG)Cl in K+-free, low Na+ solution ([Na+]o= 5.5 mM) or 138 mM NMGCl and 5 mM NaCN in K+-free, low Na+ CN solution ([Na+]o= 5.5 mM). The pH of the pipette solution and external solutions, except for the low Na+ solution and the CN solution, was adjusted to 7.2 and 7.4 with KOH and NaOH, respectively, and that of the low Na+ solution and the CN solution was adjusted to 7.4 with Tris and HCl, respectively. All chemicals were bath applied, and CN-induced currents (ICN) or muscarine-induced currents (IMUS) were evoked by perfusion of CN solution or 3 μm muscarine-containing solution. The bath solution was grounded via a 3 M KCl agar bridge, and the membrane potential was corrected for a liquid junction potential of -12 mV between the pipette solution and the standard solution. To study the effects of anoxia, bath solution containing 1 mM Na2S2O4 was bubbled with 100 % argon gas. The O2 pressure of the perfusate in the bath, measured using an acid-base analyser (ABL 30, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark), was 0 mmHg. The Na2S2O4 solution was made on the day of the experiment since O2 pressure in the solution just after addition of the O2 scavenger was 0 mmHg without bubbling, but increased with time when it was left in the air. When the voltage dependence of an anoxia-induced current was studied, 1 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA)Cl, 1 mM BaCl2 and 10 μm methoxyverapamil (D-600) were added to the perfusate to reduce Ca2+-dependent and voltage-dependent K+ currents. However, the majority of Ba2+ added seemed to form an insoluble complex with Na2S2O4 and precipitated. The concentration of free Ba2+ in the solution was sufficiently high to abolish an inwardly rectifying K+ current in chromaffin cells (Inoue & Imanaga, 1993) and was estimated to be 50 μm. All experiments were carried out at 23-25°C. Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m. and statistical significance was determined using Student's t test.

Amplitudes of IMUS in the presence of Ba2+ were fitted using a non-linear least-squares method to the logistic equation y = 1/(1 +C/IC50), where y is the relative amplitude of the current in the presence of Ba2+ expressed as a fraction of that in its absence, C is the concentration of Ba2+, and IC50 is the concentration of Ba2+ responsible for 50 % inhibition.

Chemicals

(±)-Muscarine chloride, D-600, TEACl and nystatin were obtained from Sigma; ouabain from Merck; collagenase from Yakult (Japan); NaCN from Hayashi Pure Chemical Industries (Japan); and Na2S2O4 from Nacalai tesque (Japan).

RESULTS

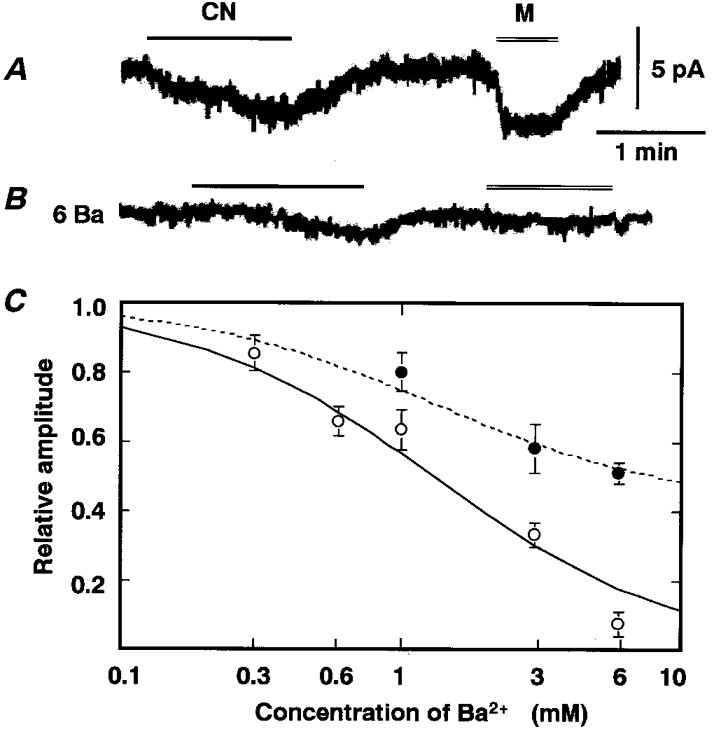

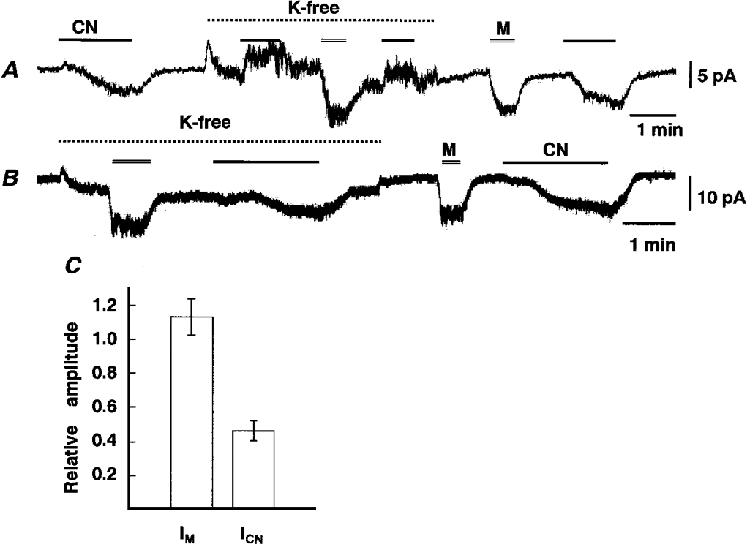

Different effects of Ba2+ on IMUS and ICN

Our previous findings (Inoue et al. 1998) suggested that muscarinic receptor stimulation and metabolic suppression with CN resulted in activation of common cation channels. To obtain further evidence for this notion, we searched for agents which would suppress IMUS, probably by plugging the channel, and compared the inhibitory potency for IMUS with that for ICN. If our notion is tenable, then inhibitory agents would be expected to suppress the two currents with the same potency. Figure 1 shows inhibition of IMUS and ICN by external Ba2+. The addition of Ba2+ to the perfusate induced a concentration-dependent inhibition of the inward current induced by 3 μm muscarine; 6 mM Ba2+ almost completely suppressed it (Fig. 1B; IMUS in 6 mM Ba2+, 7.5 ± 3.5 % of control, n = 6). Figure 1C shows that the amplitude (○) of IMUS in the presence of Ba2+ (0.3-6 mM), expressed as a fraction of that in its absence, fits a logistic equation with an IC50 of 1.3 mM, which suggests that muscarine-sensitive channels are homogeneous. In contrast to this potent inhibition of IMUS, the suppression of ICN by 6 mM Ba2+ was just 50 % of the maximum current (Fig. 1B; ICN in 6 mM Ba2+, 51 ± 2.9 % of control, n = 7). Although in this cell the initial part of ICN seemed to be completely suppressed by 6 mM Ba2+, the time course of development and decay of ICN in the presence of Ba2+ did not generally differ from that in its absence. The apparent difference between IMUS and ICN with respect to Ba2+ inhibition might suggest that muscarine- and CN-sensitive channels are distinct. Alternatively, ICN might comprise multiple current systems: for example, Ba2+-sensitive and Ba2+-insensitive ones. Therefore, we explored this possibility by studying the dose-dependent property of Ba2+ inhibition of ICN. Figure 1C shows that bath application of Ba2+ suppressed a Ba2+-sensitive component of ICN with a similar potency to that for IMUS. Relative amplitudes (•) of ICN in the presence of Ba2+ (1-6 mM) were approximated by a modified logistic equation with the same IC50 value as for IMUS; the equation assumes that Ba2+-sensitive and Ba2+-insensitive components correspond to 58 and 42 % of the total ICN, respectively. These results raise the possibility that ICN consists of at least the two components, Ba2+ sensitive and Ba2+ insensitive, whereas IMUS is composed of the Ba2+-sensitive component alone.

Figure 1. Dose-dependent inhibition of CN- and muscarine-induced currents by Ba2+.

A and B, traces of whole-cell currents at a holding potential of -62 mV in the absence and presence of 6 mM Ba2+, respectively. CN and muscarine (M) were bath applied during the periods indicated by the bar and double line, respectively; concentrations used in this and the following figures are 5 mM CN and 3 μm muscarine. A and B show results from the same chromaffin cell. C, dose-dependent inhibition of muscarine-induced current (IMUS, ○) and CN-induced current (ICN, •). Amplitudes of currents in the presence of Ba2+ are expressed as fractions of those in its absence. Means ±s.e.m. of 3-6 observations at each dose for IMUS and 2-7 observations for ICN. The continuous line and dashed line represent y = 1 /(1 +C/1.3) and y = 0.58/(1 +C/1.3) + 0.42, where y is the relative amplitude of current in the presence of Ba2+ and C is the concentration of Ba2+.

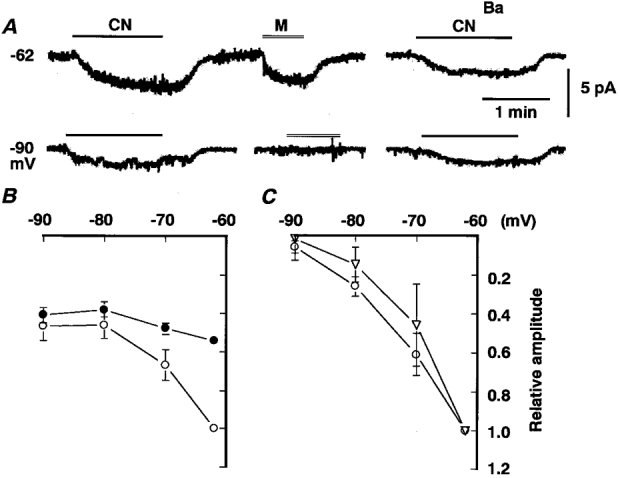

Voltage dependence of IMUS and ICN

The results with Ba2+ were entirely unexpected. Therefore, we reinvestigated the voltage dependence of IMUS and ICN at membrane potentials more negative than the ones previously studied, since one of the findings favouring involvement of common channels is a similar voltage dependence of IMUS and ICN at negative membrane potentials. Figure 2A shows ICN and IMUS elicited at -62 and -90 mV in the same cell. The shift of holding potential from -62 to -90 mV abolished IMUS, whereas it decreased ICN by 50 %. ICN in the presence of 6 mM Ba2+, the amplitude being 56 % of ICN in the absence of Ba2+, diminished only by 26 % with hyperpolarization to -90 mV. Despite these changes in the amplitude of ICN, the time course of development and decay of the current was not altered noticeably by adding Ba2+ (upper trace in Fig. 2A) or by a shift of membrane potential (lower trace), which means that Ba2+-sensitive and Ba2+-resistant components develop and decay with a similar time course. Figure 2B and C represent summaries of voltage-dependent decreases in both currents. IMUS (○ in Fig. 2C) decreased progressively with hyperpolarization to -90 mV and little current developed at -90 mV. On the other hand, the voltage-dependent decrease of ICN seemed to be restricted to membrane potentials between -62 and -80 mV, and at -90 mV ICN did not decrease further (○ in Fig. 2B). This characteristic voltage dependence of ICN may be accounted for by a different voltage dependence of the two components. The Ba2+-resistant component of ICN, which was not suppressed by 6 mM Ba2+, decreased slightly with hyperpolarization to -90 mV (• in Fig. 2B), whereas the Ba2+-sensitive component, which was obtained as the difference between currents in the absence and presence of Ba2+, diminished markedly with hyperpolarization. The I-V relationship for the Ba2+-sensitive component (▿ in Fig. 2C) almost coincided with that for IMUS (○ in Fig. 2C). These results suggest that ICN consists of two components: one is Ba2+ sensitive, possibly identical to IMUS (IMUS-like component), and the other is Ba2+ insensitive. (Hereafter, Ba2+-resistant component refers strictly to the current remaining unsuppressed in the presence of 6 mM Ba2+, and Ba2+-insensitive component to the putative component that is not suppressed by Ba2+ at all. Based on curve fitting, Ba2+-sensitive and Ba2+-insensitive components correspond to 58 and 42 % of the total ICN, respectively.)

Figure 2. Voltage dependence of ICN and IMUS.

A, traces of whole-cell currents at -62 (upper trace) and -90 mV (lower trace) in the absence (left and middle columns) and presence of 6 mM Ba2+ (right). Traces are from the same cell. The bath application of CN and muscarine are indicated by the bar and double line. B, current-voltage (I-V) relationships for ICN in the absence (○) and presence (•) of 6 mM Ba2+. Amplitudes of currents are expressed as a fraction of ICN in the absence of Ba2+ at -62 mV. Means ±s.e.m. of 3-8 observations at each potential for ICN and 5-8 observations in Ba2+. C, I-V relationships for IMUS (○) and the Ba2+-sensitive component of ICN (▿), which was obtained as the difference between ICN in the absence and the presence of Ba2+. Amplitudes of IMUS and the subtraction current are expressed as a fraction of each current at -62 mV; 2-7 observations at each potential.

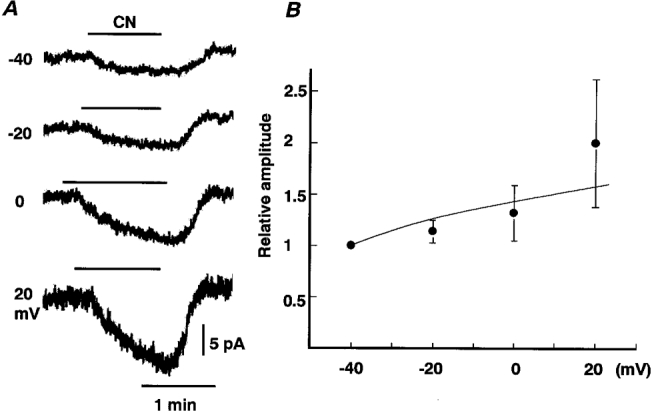

Suppression of the Na+ pump by CN

The foregoing results suggest that addition of 6 mM Ba2+ to the perfusate is a convenient means to isolate a non-IMUS-like component (i.e. Ba2+ insensitive) from the total ICN. Thus, we attempted to identify the current system responsible. To this end, the voltage dependence over a wide range of membrane potentials from negative to positive potentials was examined. Exposure to CN was expected to decrease ATP content and thus could result in suppression of the Ca2+-ATPase present in the plasma membrane and store sites, with the consequent production of Ca2+-dependent K+ currents (Inoue & Imanaga, 1998). To exclude these effects and contamination with the IMUS-like current, 6 mM Ba2+, 1 mM TEA and 10 μm D-600 were added to the perfusate. The Ba2+-resistant component of ICN elicited under such conditions tended to increase with successive shifts of the holding potential from -40 to 20 mV (Fig. 3A). Figure 3B summarizes the voltage dependence of the Ba2+-resistant component, the amplitudes of which are expressed as a fraction of the amplitude at -40 mV in each of four cells. On average, the amplitude of the current at 20 mV was roughly twice that at -40 mV. In two cells where the Ba2+-resistant current was studied at membrane potentials up to 40 mV, it was found to increase monotonically. These results suggest that the Ba2+-resistant component of ICN is not a Na+ or a Ca2+ current. In addition, suppression of a K+ current is not likely to be responsible for this current, since it did not reverse polarity at -85 mV, the equilibrium potential for K+ (EK; Fig. 2). Rather, the I-V relationship raises the possibility that inhibition of the Na+ pump current (Ipump) is responsible for the Ba2+-insensitive component of ICN (Gadsby & Nakao, 1989; Senatorov et al. 1997).

Figure 3. I-V relationship for the Ba2+-resistant component of ICN.

A, traces of whole-cell currents in the presence of 6 mM Ba2+, 1 mM TEA and 10 μm D-600. Holding potentials are given next to the traces. CN was bath applied during the period indicated by the bar. Traces are from the same cell. B, I-V relationship for the Ba2+-resistant component of ICN elicited in the presence of 6 mM Ba2+, 1 mM TEA and 10 μm D-600. Means ±s.e.m. of 4 cells. Amplitudes are expressed as a fraction of the current at -40 mV.

Figure 4 gives support to this notion. The inward current induced by CN in the presence of 6 mM Ba2+ was markedly diminished under conditions where the Na+ pump was inhibited. Removal of K+ from the perfusate containing 6 mM Ba2+, 1 mM TEA and 10 μm D-600 produced an inward current of 3.4 ± 1.3 pA (n = 5), a value which approximated the amplitude of ICN elicited before perfusion of the K+-free solution (Fig. 4A and C). Application of CN at ca 1 min after the start of perfusion resulted in a much slower development of ICN with an amplitude of 0.5 pA, the value being just 19 % of ICN before K+ removal (Fig. 4C). Similarly, administration of 200 μm ouabain, a Na+ pump inhibitor, produced an inward current of 2.3 ± 0.4 pA (n = 3) comparable to the amplitude of the preceding ICN, and conspicuously suppressed the current induced by the concomitant application of CN (Fig. 4B and D). Washout of ouabain did not restore the holding current to the original level, whereas addition of K+ to the K+-free solution sometimes restored the current above the level prior to K+ removal (Balaban et al. 1980).

Figure 4. Marked diminution of the Ba2+-resistant component of ICN in K+-free solution.

A and B, traces of whole-cell currents at -62 mV in the presence of 6 mM Ba2+, 1 mM TEA and 10 μm D-600. Exposure to CN and K+-free solution (A) or 200 μm ouabain (B) is indicated by the bar and double line, respectively. A and B show traces from different cells. C and D, summary of inward currents evoked by CN, K+ removal or 200 μm ouabain, and CN in the absence of K+ or the presence of ouabain. Amplitudes are expressed as a fraction of ICN in the same cell. Means ±s.e.m. of 6 cells in C and 3 cells in D.

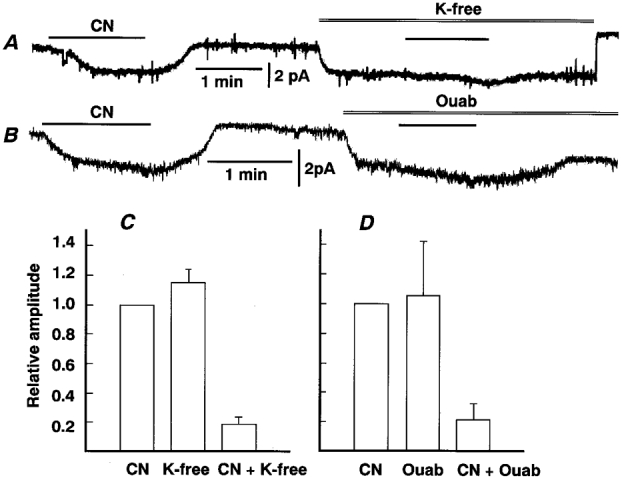

Diminution of the non-Ipump component of ICN by suppression of the Na+ pump

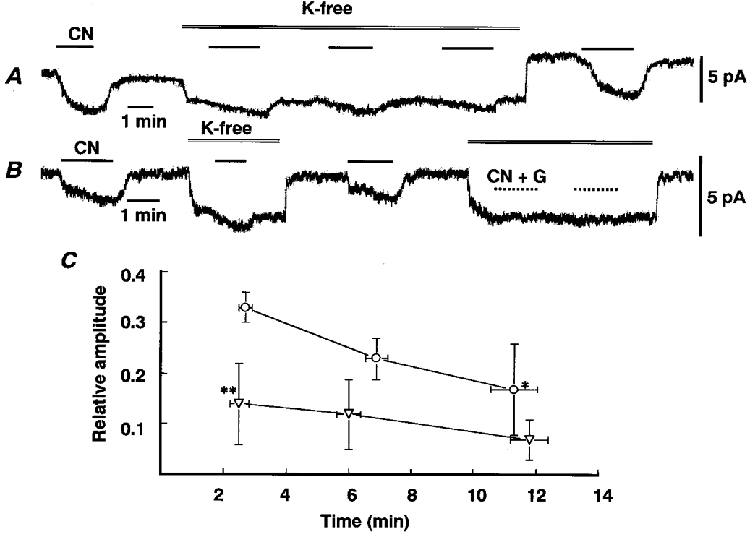

Since the Ba2+-insensitive component was found to be due to suppression of the Na+ pump, ionic mechanisms for the Ba2+-sensitive component of ICN were investigated under conditions of suppression of the Na+ pump. When K+ was omitted from the perfusate, an outward current developed transiently, and the level of current noise increased, with or without the apparent production of an inward current. In one of the five cells tested, application of CN in the absence of K+ resulted in the rapid production of an outward current with a sustained amplitude, although in the presence of K+ it slowly produced an inward current. In contrast to these complex actions of CN, IMUS was apparently not altered (Fig. 5A and C). On the other hand, in the remaining four cells, K+ removal resulted in the transient production of an outward current followed by development of an inward current with variable amplitude (3.6 ± 1.0 pA). In these cells, K+ removal diminished the amplitude of ICN by 54 ± 6 % (n = 5) (Fig. 5B). The relative amplitude (46 %) of ICN elicited in the absence of K+, which was expressed as a fraction of ICN in its presence, was smaller than the value (58 %) of the Ba2+-sensitive component estimated with the curve fitting in Fig. 1. This difference of the non-Ipump component of ICN, however, might be ascribed to concomitant production of an outward current during exposure to CN. To exclude this possibility, the effects of K+ removal were studied in the presence of 1 mM Ba2+, 1 mM TEA and 10 μm D-600 (Fig. 6); under such conditions, K+ removal no longer induced the transient outward current and exposure to CN consistently produced an inward current. Thus, we asked whether K+ removal would suppress the amplitude of ICN. As shown in Fig. 6A, the maximum amplitude of ICN elicited 2.7 min after the start of perfusion of the K+-free solution was 33 % of that in the presence of K+ and significantly diminished with perfusion time, being 17 % at 11 min. This reduction in potency of CN in eliciting an inward current was reversed by adding K+ (Fig. 6A). These results raise the possibility that a decrease in cellular ATP is involved in the generation of the non-Ipump component of ICN, and the abolition of Na+ pump activity, major machinery for ATP consumption (Rolfe & Brown, 1997), by K+ removal markedly reduces the extent of the ATP decrease resulting from suppression of oxidative phosphorylation by CN. This possibility was explored by replacing 5 mM sucrose with 10 mM glucose in the CN solution. If this notion is valid, then glycolytic ATP production might alleviate the decrease of ATP induced by CN. Figure 6B shows that the addition of glucose abolished the potency of CN to induce an inward current in the absence of K+. The amplitude of ICN in the presence of 10 mM glucose after 2.4 min of perfusion of a K+-free solution was significantly smaller than the corresponding value in 5 mM sucrose, and both currents diminished progressively (Fig. 6C).

Figure 5. Effects of K+ removal on IMUS and ICN.

A and B, traces of whole-cell currents at -62 mV, obtained from different cells. Exposure to CN, K+-free solution and muscarine is indicated by the bar, dotted line and double line, respectively. C, IMUS and ICN in the absence of K+ expressed as a fraction of each current in its presence. Means ±s.e.m. of 5 cells.

Figure 6. Suppression of the non-Ipump component of ICN by glucose.

A and B, traces of whole-cell currents at -62 mV in the presence of 1 mM Ba2+, 1 mM TEA and 10 μm D-600, obtained from different cells. Exposure to CN and to K+-free solution is indicated by the bar and double line. Sucrose at 5 mM in CN solution was replaced with 10 mM glucose during the period indicated by the dotted line. C, relative amplitude of ICN (presence of sucrose, ○; glucose, ▿) in K+-free solution plotted against time in the absence of K+. ICN in the absence of K+ is expressed as a fraction of that in its presence. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05) between amplitudes at 2 and 11 min in the presence of sucrose (*) and between those in the presence of sucrose and glucose at 2 min (**). Means ±s.e.m. of 4-13 observations at each point in sucrose and 4-5 observations in glucose.

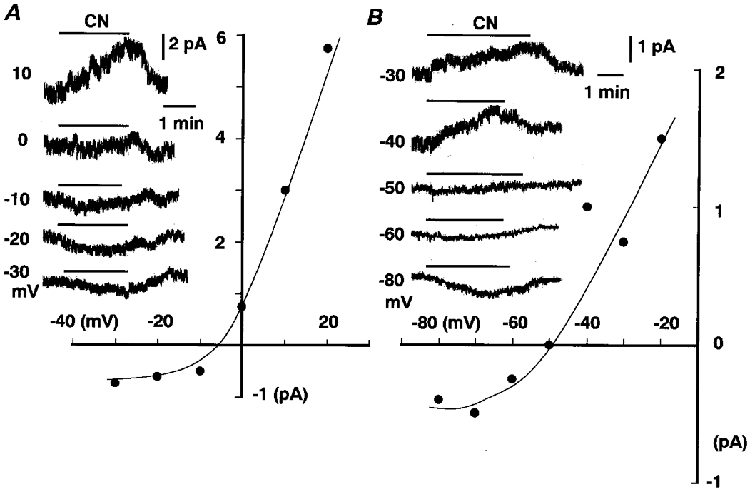

Involvement of NS channels in the non-Ipump component of ICN

To elucidate the ionic mechanism involved in the non-Ipump component of ICN, we measured its reversal potential in K+-free perfusates containing standard and low concentrations of Na+. The effects of run-down of ICN under K+-free conditions were reduced as much as possible: before exposure to CN, the membrane potential was shifted from -60 mV to a new level and the bath solution was changed from the standard to the K+-free solution, to which 1 mM Ba2+, 1 mM TEA, and 10 μm D-600 were added. Figure 7A shows the ICN elicited at various membrane potentials under K+-free conditions with a standard concentration of Na+. Exposure to CN resulted in the gradual development of inward and outward currents at negative and positive membrane potentials, respectively, with no noticeable change in the time course. The peak amplitudes were plotted against the membrane potential; the non-Ipump component of ICN reversed polarity at around -5 mV (-3.0 ± 1.2 mV, n = 5) and showed properties of an outward rectification. These characteristics are consistent with those of muscarinic receptor-regulated NS channels. Thus, we asked whether replacement of Na+ with equimolar NMG would shift the reversal potential for the non-Ipump component. Figure 7B shows that in the presence of 5.5 mM Na+, ICN generated under K+-free conditions changed polarity at -50 mV (-46.6 ± 5.7 mV, n = 5) and again the time courses of development and decay of the evoked currents were similar, regardless of whether they were inward or outward. The outwardly rectifying property of the current was also preserved in the 5.5 mM Na+ solution.

Figure 7. I-V relationships for the non-Ipump component of ICN in the presence of 147 and 5.5 mM Na+.

A and B, traces of whole-cell currents and I-V relationships for the non-Ipump component of ICN in 147 mM (A) and 5.5 mM (B) Na+. Exposure to CN is indicated by the bar. Ba2+ at 1 mM, 1 mM TEA and 10 μm D-600 were added to the K+-free solution with 147 or 5.5 mM Na+. For the low Na+ solution, Na+ was replaced with equimolar NMG.

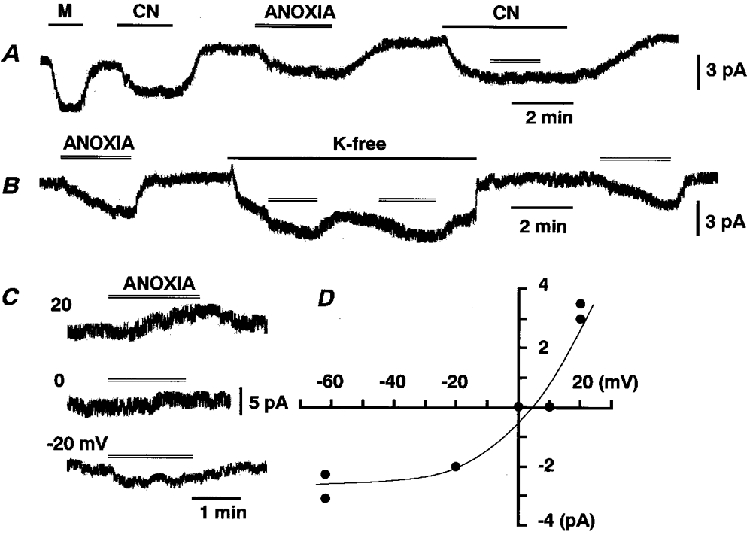

Pump inhibition and NS channel activation by anoxia

The foregoing results indicate that exposure to CN induces suppression of the Na+ pump and activation of NS channels. Since CN possibly inhibits the pump by producing reactive oxygen species (Beauchamp & Fridovich, 1973; Huang et al. 1994), either or both of the effects of CN might not relate to chemical hypoxia. Thus, we asked whether exposure to anoxia would induce suppression of the Na+ pump and activation of the channel (since anoxia consistently induced large currents compared with severe hypoxia (20 mmHg: Inoue et al. 1998), cells were exposed to anoxia in the present experiment). If our hypothesis is tenable, then the effects of CN should be masked and mimicked by a decrease in O2 tension. Figure 8 shows that this is indeed the case. Inward currents with comparable amplitudes developed in response to 5 mM CN and to anoxia, and anoxia did not induce a further inward current during development of ICN (Fig. 8A). The maximum amplitude of the anoxia-induced current was 81 ± 11 % of that of ICN elicited in the same six cells, and the peak amplitude of the current induced by CN and anoxia was 97 ± 2 % (n = 3) of ICN. This apparent occlusion indicates that the development of ICN is due to chemical hypoxia. Furthermore, the amplitude of the inward current in response to anoxia was reversibly diminished by 61 ± 4 % (n = 5) in the absence of K+ (Fig. 8B). This extent of decrease did not differ from that of ICN (P = 0.3). The current induced by anoxia in the absence of K+ reversed polarity at around 0 mV (4.8 ± 5.3 mV, n = 4) and exhibited an outward rectification (Fig. 8C and D), as was noted with ICN elicited under similar conditions. These results indicate that a decrease in O2 tension induces both suppression of the Na+ pump and activation of NS channels.

Figure 8. Anoxia mimics the effects of CN.

A and B, traces of whole-cell currents at -62 mV from different cells. Exposure to muscarine, CN, K+-free solution and anoxia is indicated by the bar or double line (anoxia). C and D, traces of whole-cell currents and I-V relationship for the non-Ipump component of anoxia-induced current. TEA at 1 mM, 10 μm D-600 and ca 50 μm Ba2+ were added to K+-free solution with 147 mM Na+ (see Methods).

DISCUSSION

Pump inhibition and NS channel activation by CN and anoxia

The present experiment clearly shows that the metabolic inhibition- and anoxia-induced inward current or depolarization are due to suppression of the Na+ pump and activation of NS channels. Two lines of evidence indicate that suppression of the Na+ pump contributes 42 % of the total ICN. Firstly, the Ba2+-resistant component of ICN, which remained unsuppressed in the presence of 6 mM Ba2+, tended to increase as the membrane potential shifted successively from -40 to 40 mV. This voltage dependence would exclude the involvement of Na+ and Ca2+ currents. In addition, the suppression of a K+ channel could not contribute to the Ba2+-resistant component, since it showed a small voltage-dependent decline with hyperpolarization to -90 mV and did not reverse polarity at EK. The finding that the Ba2+-resistant component was consistently produced in the presence of K+ channel blockers (TEA and Ba2+) would also argue against the involvement of K+ channels. The voltage dependence of the Ba2+-resistant component of ICN roughly agrees with that of the Na+ pump studied in cardiac myocytes (Gadsby & Nakao, 1989) and brain neurons (Senatorov et al. 1997). Secondly, the Ba2+-resistant component of ICN diminished by 80 % under conditions where the Na+ pump was inhibited by either K+ removal or addition of 200 μm ouabain. This result, taken together with the voltage dependence, indicates that the majority of the Ba2+-resistant component of ICN is due to suppression of the Na+ pump. As shown in Fig. 4, 20 % of the Ba2+-resistant component remained unsuppressed under conditions of Na+ pump inhibition. This remaining component cannot be ascribed to suppression of the residual Na+ pump since the Na+ pump activity was reported to be zero in the absence of external K+ (Gadsby & Nakao, 1989). Thus, another possibility would be a IMUS-like component. The difference (0.1) between the relative amplitude of the Ba2+-resistant component of ICN in the presence of 6 mM Ba2+ (0.52) and that of the Ba2+-insensitive component estimated with curve fitting (0.42) possibly represents an unsuppressed part of the Ba2+-sensitive component. Thus, in the absence of Na+ pump activity (i.e. Ba2+-insensitive component 0.42 of total ICN), 0.1 Ba2+-sensitive component would be calculated to comprise 19 % of the Ba2+-resistant ICN (i.e. 0.1 divided by 0.52), the value being consistent with the observed one. It should be noted, however, that this calculation is based on the assumption that 1 mM TEA and 10 μm D-600 produce no inhibition of ICN. In preliminary experiments, these agents at such concentrations had no or little effect on ICN.

On the other hand, the involvement of NS channels in the Ba2+-sensitive component of ICN is supported by the reversal potential for the current and its dependence on [Na+]o. Exposure to CN in the absence of K+ slowly produced inward and outward currents at negative and positive membrane potentials, respectively, and the time course of these evoked currents was not apparently altered by membrane potential. These results suggest that the change in polarity is not due to the additional production of an outward current, such as a Ca2+-dependent K+ current. Furthermore, the majority of K+ channels are probably suppressed in the presence of 1 mM Ba2+, 1 mM TEA and 10 μm D-600. Thus, the reversal potential of -3 mV may reflect a property of ion channels involved in the non-Ipump component of ICN. This value is half-way between EK and ENa and different from ECl, suggesting the involvement of NS channels. This notion is further supported by a shift of the reversal potential to -47 mV with a decrease in [Na+]o to 5.5 mM. From these results, we conclude that the non-Ipump component of ICN is due to activation of NS channels. The conductance of this CN-sensitive NS channel had an outward rectification, irrespective of [Na+]o, and decreased with hyperpolarization. These properties of the CN-sensitive channel are similar to those of muscarinic NS channels (Inoue & Kuriyama, 1991). In particular, the I-V relationship for the Ba2+-sensitive component of ICN coincided with that for IMUS in Fig. 2. Thus, it is likely that CN-sensitive channels are the same as those activated by the muscarinic receptor.

Inhibition of the Na+ pump and activation of the NS channel by CN were reproduced by anoxia (Fig. 8). Firstly, exposure to CN and to anoxia induced inward currents with comparable amplitudes and anoxia failed to evoke a further inward current during development of ICN. Secondly, removal of K+ from the perfusate diminished the anoxia-induced current by ca 60 %, the value being similar to that noted with ICN. This result suggests that the anoxia-induced current comprises inhibition of the Na+ pump and a non-pump component. Thirdly, the anoxia-induced current evoked in the absence of K+ (i.e. in the absence of Na+ pump activity) reversed polarity around 0 mV and showed an outward rectification. These properties of the non-pump component agreed with those of the CN and muscarine-sensitive NS channels. In fact, muscarine-induced currents were markedly diminished during development of the current in response to anoxia. From these results, we conclude that CN and anoxia each induce inhibition of the Na+ pump and activation of NS channels. Thus, the effects of CN are due to chemical hypoxia or anoxia.

In our previous experiments (Inoue et al. 1998), the amplitude of ICN measured 1 min after the start of CN application was roughly equal to that of 3 μm muscarine-induced current and 3 μm muscarine failed to induce a further inward current during development of ICN. We considered that this apparent occlusion of IMUS by ICN might be due to the involvement of common channels. The present experiment, however, revealed that NS channel activity contributes not more than 58 % of the total ICN. Thus, the apparent occlusion of IMUS might not be ascribed solely to saturation of NS channel activity. Activation of NS channels by infusion of a G protein activator, however, depended on the concentration of MgATP with an EC50 (concentration responsible for 50 % activation) of 0.265 mM (Inoue et al. 1996). Even a short exposure to CN may result in a conspicuous decrease of ATP content beneath the plasma membrane, where ATP is continuously consumed by active ion transport. Thus, the apparent contradiction might be accounted for by diminution of the maximum NS channel activity.

Mechanism for Na+ pump inhibition and channel activation

Effects of hypoxia have been studied not only in carotid body cells and chromaffin cells, but also in cardiac myocytes, smooth muscle cells and neurons, and various mechanisms for O2 sensing have been proposed. These mechanisms can be divided into two groups: mitochondrial and membrane hypotheses. The latter includes O2 sensing by a voltage-dependent K+ channel or closely associated protein in carotid body cells (Ganfornina & López-Barneo, 1992; López-Barneo, 1996) and by a plasmalemmal NADPH oxidase in pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies (Youngson et al. 1993). Our previous experiments and those of others (Mojet et al. 1997) revealed that hypoxia-induced catecholamine release and inward currents were mimicked by metabolic suppression with electron transport inhibitors. The straightforward interpretation of this result would be that mitochondrial dysfunction is primarily responsible for a change in ion transport across the plasma membrane, but other interpretations can also be made. The suppression of mitochondrial function by hypoxia or by certain electron transport chain inhibitors is expected to induce a shift in the cytosolic redox balance to the reduced state, and a change in the redox status was proposed to mediate hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction through inhibition of K+ channels (Archer et al. 1993). This redox-based mechanism may not be involved in the generation of ICN, since the effects of anoxia were mimicked by CN in adrenal medullary cells, but not in pulmonary smooth muscle cells, where CN is assumed to enhance oxidation with the production of reactive oxygen species. Our previous experiments (Inoue et al. 1998) excluded an increase in [Ca2+]i and a decrease in intracellular pH as possible causes of the production of ICN. Thus, one of the remaining possibilities was a decrease in ATP content.

The Na+ pump activity in a suspension of rabbit renal tubules was found to have a linear relationship with millimolar concentrations of cellular ATP, although the Na+,K+-ATPase activity in lysed membranes of tubules displayed a rectangular hyperbola as a function of ATP with an EC50 of 0.2 mM (Soltoff & Mandel, 1984). Thus, a slight decrease in cellular ATP concentration, usually 2-4 mM, would be expected to suppress the Na+ pump activity. Exposure to CN or to anoxia may not decrease the mean concentration of cellular ATP in the order of one or two tens of seconds, but may result in a marked decrease in ATP content beneath the plasma membrane on such a time scale, owing to continuous consumption by active ion transport. This idea is supported by recent findings. Firstly, an ATP-sensitive K+ current in ventricular myocytes, which developed under metabolic suppression, was suppressed with a time constant of 5 s by application of 0.5 mM strophantidin, a Na+-K+ pump inhibitor, and a similar decline of the current occurred with removal of K+ (Priebe et al. 1996). Secondly, the suppression of Na+,K+-ATPase activity by K+ removal or ouabain addition produced a rapid (in the order of a few tens of seconds) increase in NAD(P)H autofluorescence in a rabbit renal tubule suspension (Balaban et al. 1980) and in mouse pancreatic islets (Ding & Kitasato, 1997). This increase in fluorescence suggests that suppression of the pump results in a rapid inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation with the consequent increase in the reduced form of NAD(P). Based on these findings, exposure to CN and to anoxia may be assumed to induce a decrease in ATP to the extent that Na+ pump activity is reduced.

In contrast to inhibition of the pump, there is pertinent evidence for involvement of an ATP decrease in the activation of NS channels in response to CN and anoxia. As shown in Fig. 5, the CN, but not muscarinic, potency to stimulate NS channels selectively diminished in a K+-free solution. The amplitude of ICN elicited in the absence of external K+ was smaller than the estimated value of the Ba2+-sensitive component of ICN. This diminution in CN potency became progressively more conspicuous with duration of perfusion of the K+-free solution. What is more striking is that CN failed to stimulate NS channels appreciably when sucrose in a K+-free CN solution was replaced with glucose. These results suggest that CN activation of the channel is not due to a direct effect of CN or of mitochondrial dysfunction, but rather to an indirect effect through a decrease in cellular ATP. The apparent capacity of CN to decrease ATP depends on the rate of ATP consumption by the active transport system, especially the Na+ pump, and this capacity may be counteracted by glycolytic ATP production.

Physiological implications

In the present experiments, the perforated patch method was used to examine the effects of CN or anoxia on ion transport systems. This method preserves the composition of divalent cations and larger molecules inside the cell, and 10 mM Na+ present in the patch solution approximated [Na+]i (5-20 mM) of cat adrenal chromaffin cells, as determined using microfluorometry (Sorimachi et al. 1994). Thus, it is unlikely that the mechanisms elucidated relate to the experimental conditions. The second concern would be whether pump inhibition and NS channel activation are involved in depolarization or receptor potential in response to a decrease in O2 tension. Thompson & Nurse (1998) reported that anoxia induced suppression of Ca2+-dependent and delayed-rectifier type K+ channels in neonatal adrenal chromaffin cells, similar to the inhibition of K+ channels in the carotid body type I cell of the fetal rabbit (Delpiano & Hescheler, 1989) and the neonatal rat (Wyatt & Peers, 1995). The application of 10 mM TEA completely suppressed these anoxia-sensitive K+ currents, but did not affect the depolarization evoked by anoxia in the rat chromaffin cell, consistent with findings in the rat carotid body type I cell (Buckler, 1997). Even more interesting is that the depolarization was decreased to half by removal of Na+ and Ca2+ from the perfusate. This result roughly agreed with ours obtained in voltage-clamp experiments, in which the guinea-pig chromaffin cell was exposed to chemical hypoxia (Inoue et al. 1998). The presence of Na+- and Ca2+-dependent and independent components in the anoxia-induced depolarization could be readily accounted for by our notion that inhibition of mitochondrial function results in suppression of the Na+ pump and activation of NS channels (Thompson & Nurse, 1998, suggested that the component of depolarization remaining in the absence of Na+ may not be due to inhibition of the Na+ pump, which is opposite to the result of Gadsby & Nakao (1989)). Moreover, production of small inward currents was frequently noted during exposure to anoxia in voltage-clamp studies on the rat, in which most of the outward current was blocked. Thus, it is likely that the mechanisms for O2 sensing in the guinea-pig chromaffin cell also function in the rat.

Rat chromaffin cells, however, are generally assumed to lose the competence to sense hypoxia or chemical hypoxia with catecholamine secretion in adults, whereas chromaffin cells acutely dissociated from the adult guinea-pig adrenal medullae clearly responded to hypoxia and CN with the secretion and membrane responses (Inoue et al. 1998; present results). This difference between rat and guinea-pig may not be pertinent, since adult rat chromaffin cells in culture were found to secrete catecholamines in response to hypoxia (Mochizuki-Oda et al. 1997). In the light of the physiological significance of catecholamines in stress, adrenal medullary cells in the majority of mammals, including humans (Lagercrantz & Bistoletti, 1977), may be equipped with machinery for sensing hypoxia, and that in guinea-pig happens to be maintained throughout life. This maintenance in the guinea-pig might relate to the fact that the mammal originates from a high altitude habitat in South America. Since O2 pressure at such high altitudes is low, the habitat might necessitate the maintenance of the machinery for sensing hypoxia throughout life.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan and by a grant from Brain Science Foundation (Japan).

References

- Archer SL, Huang J, Henry T, Peterson D, Weir EK. A redox-based O2 sensor in rat pulmonary vasculature. Circulation Research. 1993;73:1100–1112. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban RS, Mandel LJ, Soltoff SP, Storey JM. Coupling of active ion transport and aerobic respiratory rate in isolated renal tubules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1980;77:447–451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.1.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp CO, Fridovich I. Isozymes of superoxide dismutase from wheat germ. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1973;317:50–64. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(73)90198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler KJ. A novel oxygen-sensitive potassium current in rat carotid body type I cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;498:649–662. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler KJ, Vaughan-Jones RD. Effects of hypoxia on membrane potential and intracellular calcium in rat neonatal carotid body type I cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;476:423–428. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bülbring E, Burn JH, De Elio FJ. The secretion of adrenaline from the perfused suprarenal gland. The Journal of Physiology. 1948;107:222–232. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1948.sp004265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryer PE. Physiology and pathophysiology of the human sympathoadrenal neuroendocrine system. New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;303:436–444. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198008213030806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpiano MA, Hescheler J. Evidence for a PO2-sensitive K+ channel in the type-1 cell of the rabbit carotid body. Federation of European Biochemical Societies. 1989;249:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80623-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding W-G, Kitasato H. Suppressing Na+ influx induces an increase in intracellular ATP concentration in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Japanese The Journal of Physiology. 1997;47:299–306. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.47.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Nakao M. Steady-state current-voltage relationship of the Na/K pump in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;94:511–537. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.3.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganfornina MD, López-Barneo J. Potassium channel types in arterial chemoreceptor cells and their selective modulation by oxygen. Journal of General Physiology. 1992;100:401–426. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.3.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn R, Marty A. Muscarinic activation of ionic currents measured by a new whole-cell recording method. Journal of General Physiology. 1988;92:145–159. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houssay BA, Molinelli EA. Adrenal secretion produced by asphyxia. American Journal of Physiology. 1926;76:538–550. [Google Scholar]

- Huang W-H, Wang Y, Askari A, Zolotarjova N, Ganjeizadeh M. Different sensitivities of the Na+/K+-ATPase isoforms to oxidants. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1994;1190:108–114. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Fujishiro N, Imanaga I. Hypoxia and cyanide induce depolarization and catecholamine release in dispersed guinea-pig chromaffin cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:807–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.807bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Imanaga I. G protein-mediated inhibition of inwardly rectifying K+ channels in guinea pig chromaffin cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;265:C946–956. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.4.C946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Imanaga I. Phosphatase is responsible for run down, and probably G protein-mediated inhibition of inwardly rectifying K currents in guinea pig chromaffin cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1995;105:249–266. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Imanaga I. Mechanism for hypoxia-induced secretion of catecholamines from adrenal chromaffin cells. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1997;23:2281. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Imanaga I. Activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels by cyanide in guinea pig adrenal chromaffin cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C105–111. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.1.C105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Kuriyama H. Muscarinic receptor is coupled with a cation channel through a GTP-binding protein in guinea-pig chromaffin cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;436:511–529. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Ogawa K, Fujishiro N, Yano A, Imanaga I. Role and source of ATP for activation of nonselective cation channels by AlF complex in guinea pig chromaffin cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1996;154:183–195. doi: 10.1007/s002329900143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagercrantz H, Bistoletti P. Catecholamine release in the newborn infant at birth. Pediatric Research. 1977;11:889–893. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Barneo J. Oxygen-sensing by ion channels and the regulation of cellular functions. Trends in Neurosciences. 1996;19:435–440. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-López J, González G, Ureña J, López-Barneo J. Low pO2 selectively inhibits K channel activity in chemoreceptor cells of the mammalian carotid body. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;93:1001–1015. doi: 10.1085/jgp.93.5.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-López JR, González C, Pérez-García MT. Properties of ionic currents from isolated adult rat carotid body chemoreceptor cells: effect of hypoxia. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;499:429–441. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki-Oda N, Takeuchi Y, Matsumura K, Oosawa Y, Watanabe Y. Hypoxia-induced catecholamine release and intracellular Ca2+ increase via suppression of K+ channels in cultured rat adrenal chromaffin cells. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;69:377–387. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojet MH, Mills E, Duchen MR. Hypoxia-induced catecholamine secretion in isolated newborn rat adrenal chromaffin cells is mimicked by inhibition of mitochondrial respiration. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;504:175–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.175bf.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peers C. Hypoxic suppression of K+ currents in type I carotid body cells: selective effect on the Ca2+-activated K+ current. Neuroscience Letters. 1990;119:253–256. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe L, Friedrich M, Benndorf K. Functional interaction between KATP channels and the Na+-K+ pump in metabolically inhibited heart cells of the guinea-pig. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:405–417. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe DFS, Brown GC. Cellular energy utilization and molecular origin of standard metabolic rate in mammals. Physiological Reviews. 1997;77:731–758. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senatorov VV, Mooney D, Hu B. The electrogenic effects of Na+-K+-ATPase in rat auditory thalamus. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;502:375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.375bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltoff SP, Mandel LJ. Active ion transport in the renal proximal tubule. III. The ATP dependence of the Na pump. Journal of General Physiology. 1984;84:643–662. doi: 10.1085/jgp.84.4.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorimachi M, Nishimura S, Yamagami K. Inability of Ca2+ influx through nicotinic ACh receptor channels to stimulate catecholamine secretion in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells: studies with fura-2 and SBFI microfluorometry. Japanese The Journal of Physiology. 1994;44:343–356. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.44.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RJ, Jackson A, Nurse CA. Developmental loss of hypoxic chemosensitivity in rat adrenomedullary chromaffin cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;498:503–510. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RJ, Nurse CA. Anoxia differentially modulates multiple K+ currents and depolarizes neonatal rat adrenal chromaffin cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;512:421–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.421be.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ureña J, Fernández-Chacón R, Benot AR, Alvarez De Toledo G, López-Barneo J. Hypoxia induces voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry and quantal dopamine secretion in carotid body glomus cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:10208–10211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt CN, Peers C. Ca2+-activated K+ channels in isolated type I cells of the neonatal rat carotid body. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;483:559–565. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngson C, Nurse C, Yeger H, Cutz E. Oxygen sensing in airway chemoreceptors. Nature. 1993;365:153–155. doi: 10.1038/365153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]