Abstract

The non-linear capacitance (Cnon-lin) of postnatal outer hair cells (OHCs) of the rat was measured by a patch-clamp lock-in technique. Cnon-lin is thought to result from a membrane protein that provides the molecular basis for the unique electromotility of OHCs by undergoing conformational changes in response to changes in membrane potential (Vm). Protein conformation is coupled to Vm by a charged voltage sensor, which imposes Cnon-lin on the OHC. Cnon-lin was investigated in order to characterize the surface expression and voltage dependence of this motor protein during postnatal development.

On the day of birth (P0), Cnon-lin was not detected in OHCs of the basal turn of the cochlea, whilst it was 89 fF in apical OHCs. Cnon-lin increased gradually during postnatal development and reached 2.3 pF (basal turn, P9) and 7.5 pF (apical turn, P14) at the oldest developmental stages covered by our measurements. The density of the protein in the plasma membrane, deduced from non-linear charge movement per membrane area, increased steeply between P6 and P11 and reached steady state (4200 e−μm−2) at about P12.

Voltage at peak capacitance (V½) shifted with development from hyperpolarized potentials shortly after birth (-88.3 mV, P2) to the depolarized potential characteristic of mature OHCs (-40.8 mV, P14). This developmental difference in V½ was also observed in outside-out patches immediately after patch excision. During subsequent wash-out V½ shifted towards the depolarized value found in the adult state, suggesting a direct modulation of the molecular motor.

Thus, the density of the motor protein in the plasma membrane and also its voltage dependence change concomitantly in the postnatal period and reach adult characteristics right at the onset of hearing.

Outer hair cells (OHCs) of the mammalian cochlea change their cell length reversibly upon electrical stimulation (Brownell et al. 1985). Contraction-elongation cycles can be evoked by stimuli of at least 25-100 kHz (Dallos & Evans, 1995; Gale & Ashmore, 1997b; Frank et al. 1999). This fast electromotility is thought to constitute the effector arm of an active feedback mechanism, the cochlear amplifier (Davis, 1983; Dallos & Corey, 1991), which enables the exquisite sensitivity and frequency selectivity of the mammalian inner ear.

The electromotility of OHCs is directly driven by changes in membrane potential (Ashmore, 1987; Santos-Sacchi & Dilger, 1988; Dallos et al. 1991; Kalinec et al. 1992) and is accompanied by translocation of electrical charge across the basolateral membrane (Ashmore, 1989; Santos-Sacchi, 1991), similar to the gating currents of voltage-gated ion channels (Armstrong & Bezanilla, 1974). Based on the tight coupling of electromotility and charge transfer and the localization of both effects in the lateral membrane, a transmembrane protein has been proposed as the molecular basis of OHC electromotility (Dallos et al. 1991; Kalinec et al. 1992). This protein, termed motor protein (Gale & Ashmore, 1997a), is thought to constitute a charged voltage sensor that moves through the membrane electrical field, thereby inducing a conformational change in the protein, which in turn alters its area in the membrane plane (Dallos et al. 1993; Iwasa, 1994). The molecular identity of the OHC motor protein is as yet unknown.

He et al. (1994) have shown that postnatal OHCs of gerbils begin to acquire electromotile properties 7 days after birth, and reach adult motility levels shortly after the onset of hearing at about P12. During these first 2 weeks, OHCs change from small epithelial cells to the elongated cylindrical cells characteristic of the adult mammalian organ of Corti. Maturation includes formation of the lateral cortex of the OHC, which is composed of the cytoskeletal lattice and one to several layers of subsurface cisternae (Pujol et al. 1991; Weaver & Schweitzer, 1994). It is, therefore, unclear whether the onset of motile properties reflects the expression pattern of the putative motor or rather results from the acquisition of the prerequisites of motility, such as the elastic properties of the OHC or cell turgor (Holley & Ashmore, 1988).

To address this question, we aimed to derive information on the expression of the motor protein during postnatal development by measuring the voltage-dependent charge transfer that is associated with the voltage sensor. Fast charge translocation imposes a voltage-dependent capacitance on the OHC (Santos-Sacchi, 1991; Gale & Ashmore, 1997a), which was measured with a high resolution patch-clamp lock-in technique (Neher & Marty, 1982; Fidler & Fernandez, 1989).

METHODS

Preparation

Organs of Corti were dissected from the cochleae of postnatal Wistar rats as described previously (Oliver et al. 1997). Briefly, animals were killed by decapitation, cochleae were dissected and the organ of Corti was separated from the modiolus and stria vascularis. The basal and apical turns were mounted onto coverslips with glass filaments. The preparation was performed in a solution containing (mM): 144 NaCl, 5.8 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 0.9 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 0.7 Na2HPO4, 5.6 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.3 with NaOH. Osmolality was 305 ± 2 mosmol kg−1. For the recordings, OHCs located approximately half a turn from either the apex or the base of the cochlea were selected. If necessary, supporting cells were removed with gentle suction from a cleaning pipette. All experiments were performed at room temperature (21-24°C) within 4 h of dissection. Animal care and experiments followed approved institutional guidelines at the University of Tübingen.

Patch-clamp recording

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). Electrodes were pulled from quartz glass, had resistances of 2-3 MΩ and were coated with Sylgard. Electrodes were filled with intracellular solutions, composition (mM): Cs+-based solution: 100 CsCl, 20 TEA-Cl, 3.5 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 6 BAPTA, 2.5 Na2ATP, 5 Hepes, pH 7.3 with CsOH; K+-based solution: 125 KCl, 20 TEA-Cl, 3.5 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 5 K2EGTA, 2.5 Na2ATP, 5 Hepes, pH 7.3 with KOH. Osmolality was adjusted to 305 ± 1 mosmol kg−1 with glucose. These solutions blocked most of the outwardly rectifying K+ currents of postnatal OHCs. After seal formation on the basolateral membrane the whole-cell configuration was achieved by rupturing the patch with electrical zapping to avoid disturbance of the cell turgor by suction. Whole-cell series resistances ranged from 3 to 10 MΩ. Cells were voltage clamped at -60 or -80 mV, without correction for liquid junction potentials (6 mV and 4 mV for Cs+- and K+-based pipette solutions, respectively).

During recordings the bath was continuously perfused with dissection solution (see above). For one set of experiments, OHCs were locally perfused with extracellular solutions of modified osmolarity via a glass capillary. These solutions had the following composition (mM): 125 NaCl, 5.8 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 0.9 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 0.7 Na2HPO4, 5.6 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.3 with NaOH. Osmolality was adjusted to 285, 305, 365 or 405 mosmol kg−1 with sucrose.

Outside-out patches were excised from the basolateral membrane of OHCs after a quick test for non-linear capacitance in the whole-cell mode. K+-based pipette solution was used for outside-out patch experiments.

Capacitance measurements

Voltage-dependent capacitance was measured by two different methods. First, the phase-tracking technique (Neher & Marty, 1982; Fidler & Fernandez, 1989), which employs a software lock-in amplifier and was implemented as an IgorPro XOP (Herrington et al. 1995), was used. After manual compensation of membrane capacitance (Cm), lock-in phase angles yielding signals proportional to changes in Cm and conductance were calculated by dithering the series resistance by 0.5 MΩ. The capacitance output was calibrated by a 100 fF change in the Cm compensation setting. Command sinusoid (2.6 kHz, amplitude 10 mV, sampling rate 83 kHz) was filtered at 5 kHz with an 8-pole Bessel filter, and 16 periods were integrated to generate each capacitance point. To obtain the voltage dependence of membrane capacitance, voltage ramps ranging from -120 to +70 mV or -160 to +30 mV (slope, 0.16 V s−1 or -0.16 V s−1) were summed to the sinusoid command during capacitance measurements. Scaled capacitance traces as well as the conductance signal and DC current induced by the voltage ramp were plotted versus the membrane voltage.

The second method employed a stairstep stimulus (Huang & Santos-Sacchi, 1993a), which increased membrane potential in 5 mV steps, each lasting 5 ms. Cm compensation was omitted in these measurements. Current output filter was set to 10 kHz (sampling rate, 100 kHz). For each voltage step, the decay time constant of the current, τ, was obtained from a monoexponential fit to the transient. Input resistance (Rin) was calculated from the steady-state current and charge (Q) was obtained by integration. Capacitance Cm(i) at each voltage step i was derived by an equation given by Huang & Santos-Sacchi (1993a), taking into account the contribution of the relatively low Rm of mature OHCs:

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

| (3) |

Rs is the series resistance, Rm is the membrane resistance and Vc is the command voltage step amplitude. Cm(i) was plotted versus (V(i) +V(i+ 1))/2, after correction of all voltages for series resistance errors.

Data evaluation

Processing and fitting of data were performed with IgorPro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA) on a Macintosh PowerPC.

The capacitance was fitted with a derivative of the Boltzmann function:

| (4) |

where Clin is the residual linear membrane capacitance, not compensated for by the Cm compensation circuit of the amplifier, V is the membrane potential, Qmax is the maximum voltage sensor charge moved through the membrane electrical field, V½ is the voltage at half-maximum charge transfer and α is the slope factor of the voltage dependence. Maximum voltage-dependent capacitance (Cpeak) occurs at V½.

The whole-cell membrane capacitance (Cm) of OHCs was determined from the current transient evoked by a 10 mV step depolarization with Cm compensation disabled, as described above for the stairstep method (eqn (1)). Linear capacitance was calculated as the difference between Cm and non-linear capacitance. When the stairstep method was applied, linear capacitance was directly derived as Clin from eqn (4). As a measure of the motor protein density in the OHC membrane, the maximum charge transfer, Qmax, reflecting the number of voltage-sensing proteins, was divided by the linear capacitance, which is proportional to the membrane area. This normalized charge transfer will be termed charge density.

All data are given as means ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Non-linear capacitance in postnatal OHCs

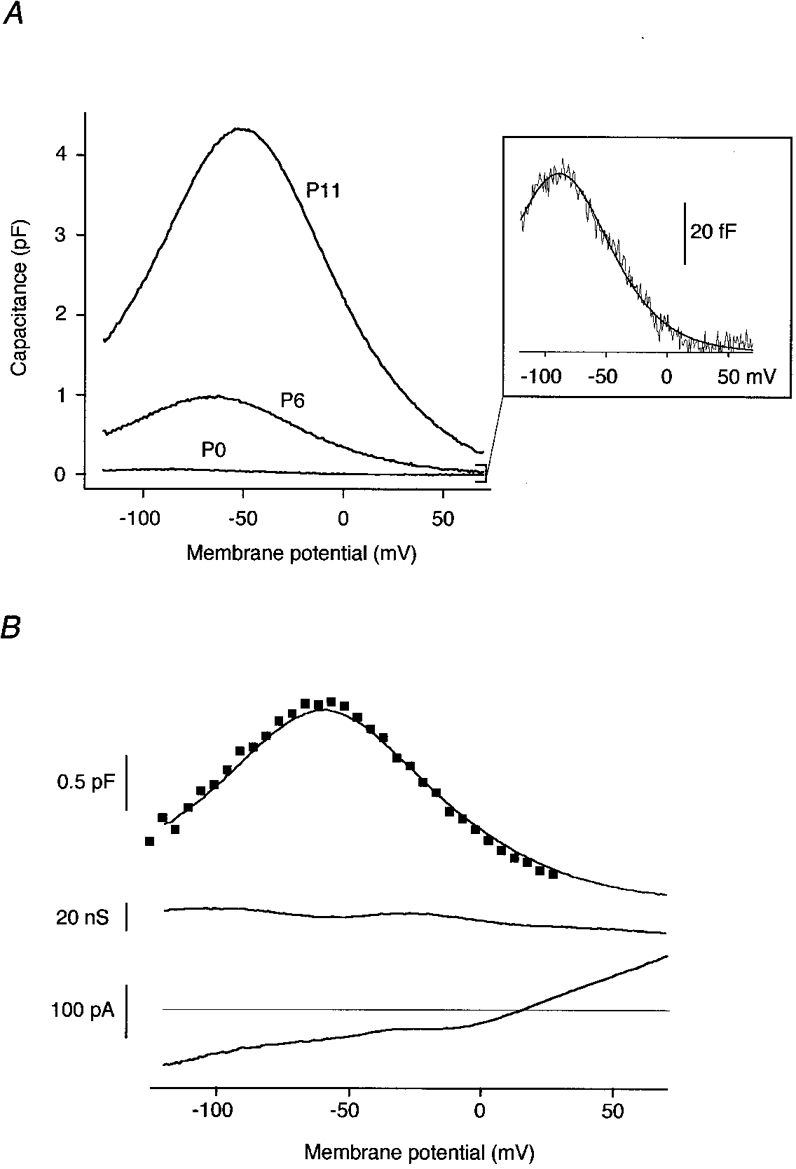

Non-linear capacitance (Cnon-lin) as measured in rat OHCs at three stages of postnatal development is shown in Fig. 1A. At any stage, Cnon-lin showed a bell-shaped voltage dependence that could be well fitted with the derivative of a first-order Boltzmann function (eqn (4)). At P6, for example, these fits yielded values for Cpeak, V½ and α of 0.79 ± 0.33 pF, -73.0 ± 7.6 mV and 30.3 ± 1.6 mV, respectively (n = 10). Cnon-lin was not detected in supporting cells (Deiters cells) at any developmental stage (data not shown).

Figure 1. Cnon-lin from OHCs of postnatal rats measured with the phase-tracking technique.

A, Cnon-lin from apical OHCs of the developmental stages indicated. Residual linear capacitance was subtracted for display. Inset: Cnon-lin (P0) on an enlarged scale. The line is the fit of eqn (4) to the data. Fit parameters were: V½= -88.7 mV, α= 27.8 mV, Qmax= 7.2 fC at P0; V½= -66.3 mV, α= 30.0 mV, Qmax= 116.3 fC at P6; and V½= -51.8 mV, α= 30.4 mV, Qmax= 522.1 fC at P11. B, capacitance (upper trace), conductance (middle trace), and DC current (lower trace) as obtained with the phase-tracking technique during a voltage ramp (1.2 s) from -120 to +70 mV (P7, apical). Squares overlaid onto the upper trace are capacitance data from the same cell obtained with the stairstep method. Fits to the capacitance (not shown) yielded V½= -60.1 mV, α= 27.6 mV, Qmax= 192.3 fC (phase-tracking) and V½= -62.2 mV, α= 26.9 mV, Qmax= 195.4 fC (stairstep). Cs+-based pipette solution was used throughout the experiments shown in A and B.

As shown in Fig. 1A, the amplitude of Cnon-lin varied considerably between developmental stages, necessitating an experimental approach that is both highly sensitive to detect small Cnon-lin and robust for evaluation of large changes in capacitance. Figure 1B shows capacitance, conductance, and DC current traces recorded with the phase-tracking technique in response to a voltage ramp from -120 to +70 mV. No cross-talk between capacitance and conductance signals occurred, indicating that this capacitance technique can be applied with negligible errors, even though some residual potassium current was activated by depolarization. Phase tracking allowed the measurement of voltage-dependent capacitances of Cpeak < 50 fF in neonatal OHCs (Fig. 1A, inset). However, for Cpeak > 4 pF, significant cross-talk between capacitance and conductance traces became obvious in the phase tracking data. Therefore, quantitative measurements of capacitances > 4 pF were achieved with the stairstep method. For intermediate peak capacitances, data obtained by the two methods were in good agreement (Fig. 1B), while small capacitance changes (Cpeak < 1pF) could not be resolved sufficiently with the stairstep method due to its lower signal-to-noise ratio.

Development of motor protein expression

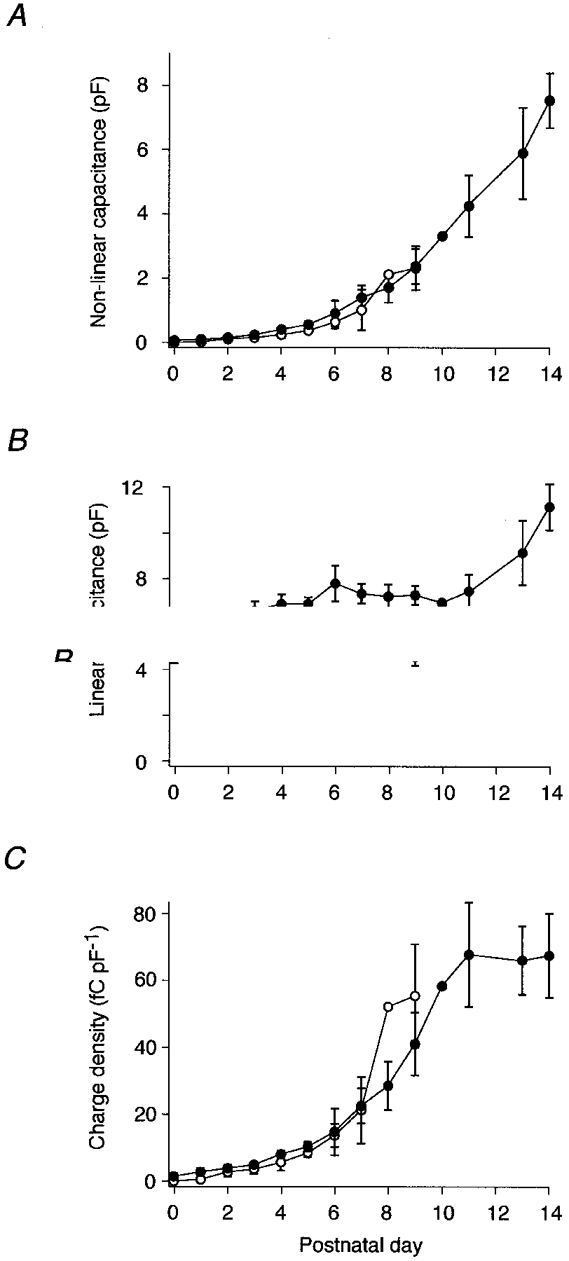

The increase in Cnon-lin was investigated in more detail by determining its growth from P0 to P14 (Fig. 2A). At P0, Cnon-lin was not observed in OHCs from the basal turn of the cochlea (n = 6 cells), while a small amount was found in apical OHCs (Cpeak= 89 ± 36 fF, n = 8). During subsequent development, Cpeak gradually increased to 2.3 ± 0.7 pF (n = 6) in basal and to 2.4 ± 0.5 pF (n = 7) in apical OHCs at P9. Since basal OHCs from older animals died rapidly after dissection of the cochlea, experiments on basal OHCs were restricted to cells younger than P10. The Cpeak of apical OHCs further increased to reach 7.5 ± 0.8 pF at P14 (n = 12).

Figure 2. Increase in Cnon-lin during postnatal development.

Peak Cnon-lin (A), linear capacitance (B) and charge transfer density (C, see Methods), plotted as a function of time after birth for OHCs from the basal turn (○) and the apical turn (•) of the rat cochlea. The numbers of cells measured at the various ages are 6, 6, 7, 5, 6, 5, 5, 6, 1 and 6 for basal cells and 8, 4, 8, 5, 7, 6, 5, 8, 9, 7, 1, 6, 6 and 12 for apical OHCs. Cells were obtained from individuals of 4 litters. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Simultaneously with Cnon-lin, the size of OHCs changed, as reflected by changes in the linear capacitance, which is proportional to membrane area. In apical OHCs, membrane area increased as the cells elongated to establish their adult appearance, whereas it decreased slightly in basal OHCs (Fig. 2B). Thus, to derive information about protein density in the membrane the charge, Qmax, was normalized to the linear membrane capacitance. Figure 2C shows that charge density increased steeply between postnatal days 5 and 10. In contrast to the absolute value of Cnon-lin, however, charge density displayed saturation after P11, with a steady-state value of 67.5 ± 12.5 fC pF−1 at P14. This indicated that mature motor protein density is established at this stage, and further increase in non-linear capacitance is due to an increase in membrane area containing the same density of motor proteins.

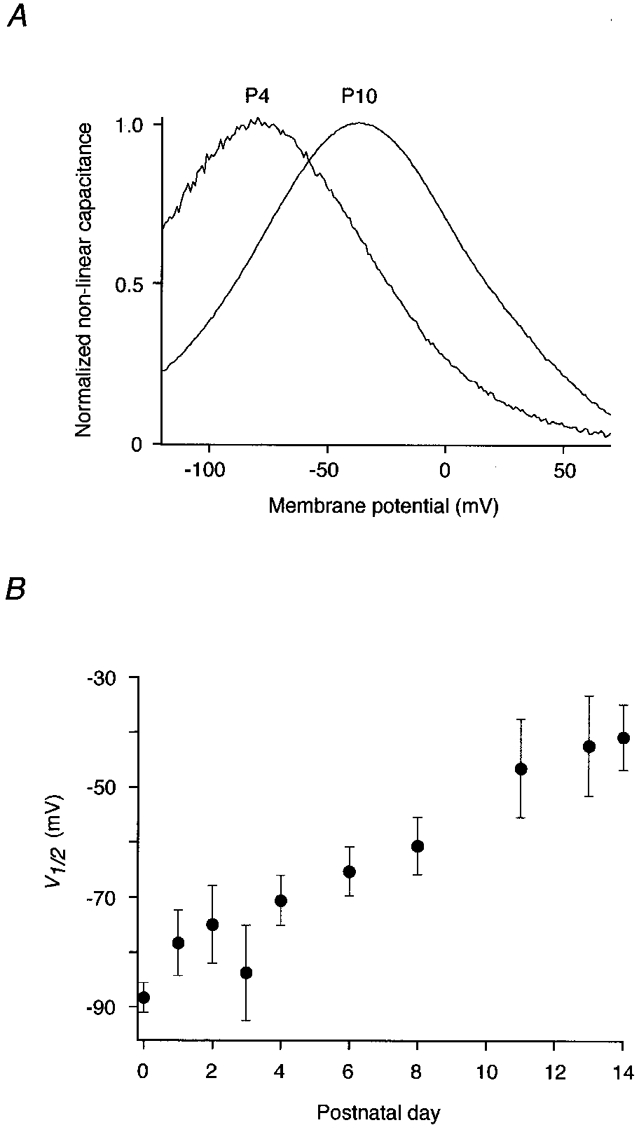

Voltage dependence changes during postnatal development

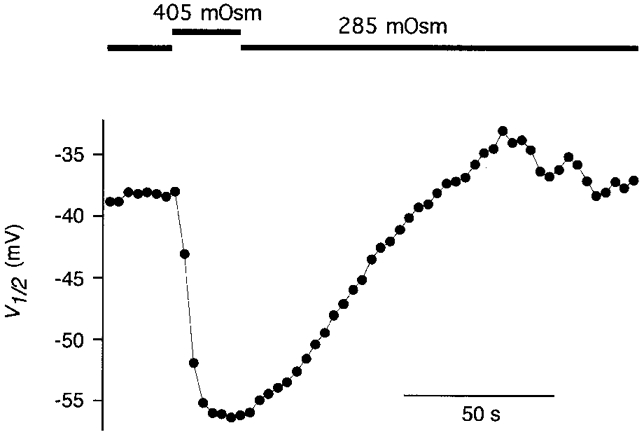

In addition to its density in the plasma membrane, the voltage dependence of the motor protein changed during postnatal development. As shown in Fig. 3B, V½ shifted from -88.3 ± 2.7 mV (P0) to -40.8 ± 6.0 mV at P14. This shift might be caused by biochemical modulation of the motor protein or it might reflect the influence of cellular properties, such as membrane tension (Iwasa, 1993; Gale & Ashmore, 1994; Kakehata & Santos-Sacchi, 1995) or structural elements, on functional characteristics of the protein. To test for alteration of membrane tension as a mechanism underlying the shift of V½, we abolished tension by deflating the cells via perfusion with hyperosmotic (365 or 405 mosmol kg−1) extracellular solution. Fast cell collapse and reinflation of the cells following solution exchange were monitored through the experimental microscope. As found previously (Kakehata & Santos-Sacchi, 1995), removal of cell turgor (and thereby membrane tension) led to a reversible shift of V½ to more negative potentials (Fig. 4). The osmotic collapse of 15 OHCs (P12-14) yielded a V½ at zero tension of -54.9 ± 7.4 mV, a value significantly different from that observed in neonatal OHCs (P < 0.001, Student's t test). Furthermore, perfusion of OHCs at P3 and P4 with hyper- and hyposmotic solution also shifted V½ reversibly (data not shown). This indicated that a mechanism different from increase in membrane tension must account for the observed developmental shift of V½.

Figure 3. Voltage dependence of the motor protein changes during postnatal development.

A, Cnon-lin from P4 and P10 apical OHCs normalized to the respective Cpeak. Note the developmental shift of V½ at constant slope. Parameters yielded by fits (not shown) as in Fig. 1 were V½= -79.1 mV, α= 31.1 mV for P4 and V½= -36.2 mV, α= 30.5 mV for P10. B, V½ of apical OHCs plotted versus time after birth (n = 3, 4, 8, 5, 7, 6, 8, 10, 10 and 12, respectively). Measurements were obtained within 30 s of establishment of the whole-cell configuration. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Figure 4. Release of cell turgor reversibly shifts V½.

A P13 OHC was perfused with hyposmotic solution. Upon switching to hyperosmotic solution, the cell quickly collapsed as viewed through the experimental microscope, but recovered after return to control solution. V½ was monitored continuously by taking a phase-tracking measurement of Cnon-lin every 3.15 s. Note that V½ does not reach the hyperpolarized values of neonatal OHCs.

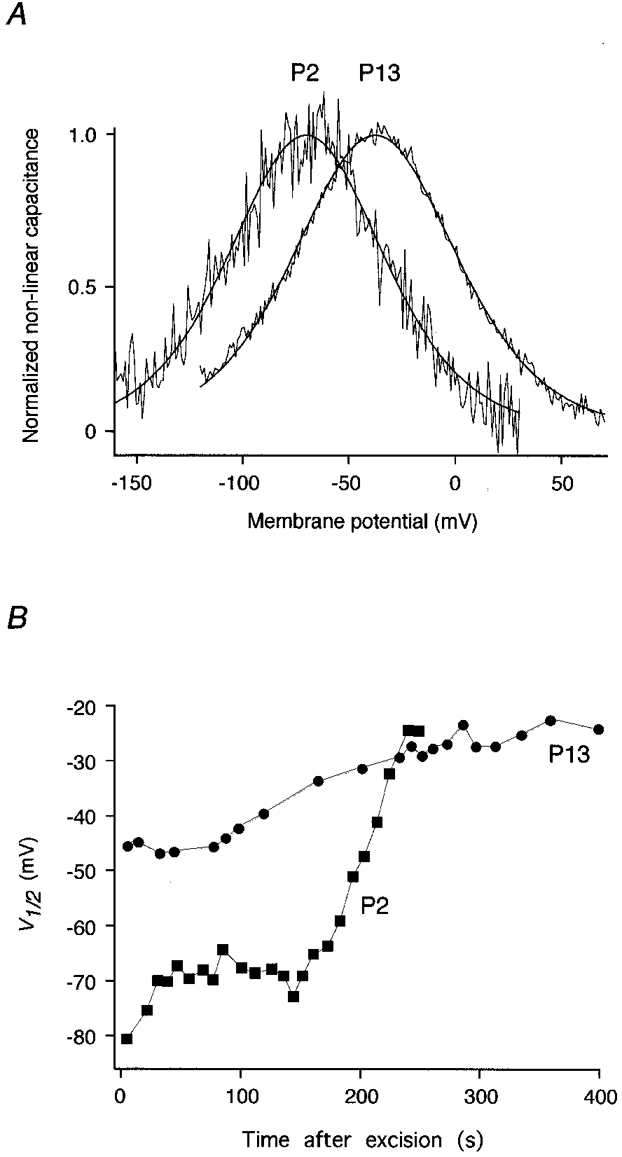

More information about the mechanism underlying the V½ shift was gained from experiments with excised patches. Cnon-lin was consistently detected with the phase-tracking technique in outside-out patches (Fig. 5), excised from the basolateral membrane of postnatal OHCs. At stages P13-14 Cpeak was 30.2 ± 14.1 fF (n = 6), while at P2 only a small capacitance signal was detected in 3 out of 7 patches (Cpeak= 2.1 ± 0.7 fF). These values of Cnon-lin in patches correspond to the developmental differences found in the whole-cell configuration. Moreover, the developmental shift in V½ that was observed in the whole-cell configuration was reproduced under cell-free conditions: V½ was -83.4 ± 12.6 mV at P2 and -39.1 ± 16.5 mV at P13/14 when measured immediately after excision of the patches (Fig. 5A). Following excision, however, V½ slowly shifted to more depolarized potentials, finally yielding V½≥ -20 mV. This was observed in patches from both P2 and P13/14 (Fig. 5B). These findings indicate that the developmental shift of V½ can be mimicked in excised patches by wash-out of the cytoplasm and suggest modulation of the motor protein rather than an interaction with structural elements, such as the cortical lattice or subsurface cisternae.

Figure 5. Changes in V½ in outside-out patches during development and wash-out.

A, normalized Cnon-lin measured in outside-out patches from OHCs at P2 and P13. Lines represent fits to the data as in Fig. 1. Parameters were V½= -70.3 mV, α= 24.2 mV, Qmax= 0.28 fC at P2, and V½= -37.9 mV, α= 25.5 mV, Qmax= 5.41 fC at P13. B, V½ shifts to depolarized membrane potentials following patch excision in both P2 and P13 patches. Measurements are from the same patches as in A. The pipette solution was K+ based.

In contrast to V½, the slope (α) of voltage dependence remained constant throughout the postnatal development. At P1, α was 31.7 ± 2.0 mV and at P11 it was 29.4 ± 0.8 mV. Calculation of the sensor charge that moves through the membrane field yields a charge valency of 0.80 e− and 0.87 e−, respectively, closely matching data from adult guinea-pig OHCs (Santos-Sacchi, 1991, 1998; Tunstall et al. 1995).

DISCUSSION

Here we describe the occurrence and developmental changes of Cnon-lin in postnatal OHCs from rat, using high-resolution lock-in techniques. This capacitance is generated by a transmembrane protein, which presumably underlies fast electromotility (Huang & Santos-Sacchi, 1993a, 1994; Iwasa, 1994). Capacitance measurements suggest the onset of surface expression of the motor protein shortly after birth and a subsequent steep increase in abundance as well as a change in its voltage dependence. Both surface expression and voltage dependence change with a similar timecourse and reach adult characteristics at the onset of hearing prior to the subsequent refinement of auditory function (Henley et al. 1989; Rybak et al. 1992). The developmental expression pattern shown here might be used for molecular identification of the motor protein in the future.

Onset and development of expression of the motor protein

Cnon-lin, reflecting functional expression of the motor protein, can first be detected in rat OHCs at P0 to P1, and protein expression increases by more than two orders of magnitude during postnatal development. Expression density saturates concomitantly with the onset of hearing, which occurs at about P12 in rat, as indicated by the onset of the compound action potential (Rybak et al. 1992) and otoacoustic emissions (Henley et al. 1989). Assuming a specific membrane capacitance of 10 fF μm−2, charge transfer is then about 4200 e−μm−2, similar to values obtained from adult guinea-pig OHCs (Santos-Sacchi, 1991; Huang & Santos-Sacchi, 1993a; Gale & Ashmore, 1997a). No attempts have been made here to account for the apical and basal pole membrane areas, which are known to be devoid of non-linear capacitance (Huang & Santos-Sacchi, 1993a). The development of electromotility has been studied in gerbil OHCs (He et al. 1994). Though inter-species differences have to be considered, the functional maturation of the auditory system with the onset of hearing around P12-14 and the subsequent refinement of auditory function is very similar in rat (Henley et al. 1989; Rybak et al. 1992) and gerbil (Woolf & Ryan, 1984; Norton et al. 1991), allowing useful comparison of OHC maturation between the two species. Using the microchamber technique, He et al. (1994) reported the first appearance of motility at P7 in basal and at P8 in apical OHCs. The threshhold of the motile reaction improved up to P12-14, when adult sensitivity was reached. This increase in sensitivity correlates well with the postnatal period in which we detected a steep increase in charge transfer density, and may, therefore, be linked to an increase in surface expression level of the motor protein. More specifically, the relative length change of OHCs, which should be proportional to the number of independent motor units per cell length unit, saturates at about P14 in the gerbil, reasonably matching our data on protein density. However, it should be stressed that we detect a significant amount of functional motor protein prior to the onset of electromotility. An explanation for this divergence might be that the motile amplitudes provided by a small number of motor units may not exceed the noise floor of the photodiode measurements (He et al. 1994).

There is substantial experimental evidence that OHC motility originates in the plasma membrane and that the cytoskeletal cortical lattice and the subsurface cisternae are not essential for electromotility (Kalinec et al. 1992; Huang & Santos-Sacchi, 1994; Gale & Ashmore, 1997b), although the cytoskeleton appears to be necessary to shape the macroscopic movement of the cell, i.e. elongation and contraction in the longitudinal axis (Holley et al. 1992). In addition, cell turgor is required to establish the macroscopic movement, though voltage-dependent transitions of the motor protein occur in the absence of positive pressure (Santos-Sacchi, 1991). It is, therefore, conceivable that the maturation of structural features of the OHC determines the onset of electromotility. Indeed, Pujol et al. (1991) observed a developmental correlation between the onset of electromotility and the maturation of the cytoskeleton and subsurface cisternae. This might also explain the base-to-apex gradient in the onset of motility found in the gerbil (He et al. 1994) and guinea-pig (Pujol et al. 1991), which is not obvious in the expression pattern of the motor protein. The assembly of motor units into the tightly packed orthogonal array of particles seen in the adult OHC membrane (Forge et al. 1991; Kalinec et al. 1992) might also be a prerequisite for the generation of macroscopic movements and might lag behind the appearance of the protein in the membrane.

Freeze-fracture replicas of the OHC lateral membrane show a large increase in the number of intramembrane protein particles during postnatal development in the gerbil (Souter et al. 1995). Though different populations of particles were observed, the agreement with the onset of non-linear capacitance, e.g. occurrence prior to the onset of motility, indicates that at least a subset of these particles might indeed represent the motor protein.

Changes in voltage dependence

In addition to the deduced upregulation of protein density, voltage dependence of the motor protein undergoes a significant change during the first two weeks after birth. V½ shifts by as much as 50 mV, reaching the value reported for adult guinea-pig OHCs (Ashmore, 1989; Santos-Sacchi, 1991; Gale & Ashmore, 1997a). In contrast, the slope of the voltage dependence did not change. Although the mechanism underlying this change remains to be elucidated, we ruled out several mechanisms previously shown to affect V½. The influence of membrane tension, which has been shown to shift V½ towards more positive voltages (Iwasa, 1993; Gale & Ashmore, 1994; Kakehata & Santos-Sacchi, 1995), can be excluded since the V½ shift persists at zero membrane tension as well as in outside-out patches. Equally, dependence of V½ on membrane potential (Santos-Sacchi et al. 1998) does not change during development (D. Oliver, unpublished observation). Moreover, the V½ difference remains unaltered by patch excision, suggesting that membrane-associated structures such as the cortical lattice and the subsurface cisternae are not directly involved in modulating voltage dependence. Another intriguing explanation for the observed voltage shift would be the assembly of the voltage sensor with an accessory β-subunit, as would be expected to occur if the voltage sensor and molecular motor were located on separate subunits. In isolated patches, however, a slow shift in V½, mimicking the developmental shift, was consistently observed. This argues strongly against an association-induced shift, but rather resembles the wash-out phenomena well known from a large number of ion channel types (e.g. Fakler et al. 1994). We therefore conclude that it is most likely that the motor protein is subject to a regulatory process, such as phosphorylation/dephosphorylation (Hunter, 1995) or interaction with specific membrane phospholipids, which have recently been shown to regulate a variety of transporters and ion channels (Hilgemann & Ball, 1996; Baukrowitz et al. 1998). In line with this interpretation are recent results indicating that reagents affecting calmodulin-dependent protein phosphorylation may shift non-linear capacitance (Huang & Santos-Sacchi, 1993b; Frolenkov et al. 1999).

The V½ shift of the voltage sensor explains nicely an observation by He et al. (1994) on isolated OHCs from the gerbil. These authors showed an elongation asymmetry in P7 cells, i.e. the elongation observed upon hyperpolarization is larger than the contraction upon depolarization. A minor population of cells exhibited the reverse behaviour, contraction asymmetry. The relation between cells displaying elongation versus cells displaying contraction asymmetry was shown to reverse during the course of the next week. Elongation asymmetry means that at the resting potential (VR), more motor units are in the ‘contracted state’ than in the ‘elongated state’, i.e. the resting potential is positive to V½. Assuming a developmentally constant VR of around -60 mV (Russell & Richardson, 1987; Oliver et al. 1997), our data show a V½ shift from negative to VR, yielding an elongation asymmetry, to positive to VR, yielding a contraction asymmetry.

In addition to the asymmetry of OHC motility, the gain of the cochlear amplifier, which is defined by the slope of the length change versus voltage function, δL(V), also changes. It is directly proportional to Cnon-lin, since this function is the derivative of the voltage dependence of the motor protein. Maximum gain corresponds to peak capacitance, i.e. it occurs at V½. At the onset of OHC electromotility around P7 (He et al. 1994), V½ equals the assumed membrane potential of -60 mV, providing maximum gain of the OHC motor. During subsequent development, V½ shifts away from the resting potential, resulting in decreased motor gain. Nevertheless, the amplitude and sensitivity of motility increase during this period (He et al. 1994), suggesting that the level of motility in maturing OHCs may be explained by the density of functional motor units, as outlined above.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Peter Ruppersberg, Tobias Moser, Jost Ludwig, Uwe Schulte and Anthony Gummer for many helpful discussions and for reading the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to B. F. (SFB 430, A1) and by the Bundesministerium für Forschung und Technologie (IZKF 2000, TP I A1).

References

- Armstrong CM, Bezanilla F. Charge movement associated with the opening and closing of the activation gates of the Na channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1974;63:533–552. doi: 10.1085/jgp.63.5.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore JF. A fast motile response in guinea-pig outer hair cells: the cellular basis of the cochlear amplifier. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;388:323–347. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore JF. Transducer motor coupling in cochlear outer hair cells. In: Wilson JP, Kemp D, editors. Mechanics of Hearing. New York: Plenum Press; 1989. pp. 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Schulte U, Oliver D, Herlitze S, Krauter T, Tucker SJ, Ruppersberg JP, Fakler B. PIP2 and PIP as determinants for ATP inhibition of KATP channels. Science. 1998;282:1141–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell WE, Bader CR, Bertrand D, de Ribaupierre Y. Evoked mechanical responses in isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 1985;227:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.3966153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Corey ME. The role of outer hair cell motility in cochlear tuning. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1991;1:215–220. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(91)90081-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Evans BN. High frequency motility of outer hair cells and the cochlear amplifier. Science. 1995;267:2006–2009. doi: 10.1126/science.7701325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Evans BN, Hallworth R. Nature of the motor element in electrokinetic shape changes of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature. 1991;350:155–157. doi: 10.1038/350155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Hallworth R, Evans BN. Theory of electrically driven shape changes of cochlear outer hair cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70:299–323. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H. An active process in cochlear mechanics. Hearing Research. 1983;9:79–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(83)90136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakler B, Brändle U, Glowatzki E, Zenner H-P, Ruppersberg JP. Kir2.1 inward rectifier K+ channels are independently regulated by protein kinases and ATP hydrolysis. Neuron. 1994;13:1413–1420. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler N, Fernandez JM. Phase tracking: an improved phase detection technique for cell membrane capacitance measurements. Biophysical Journal. 1989;56:1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82762-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Davies S, Zajic G. Assessment of ultrastructure in isolated cochlear hair cells using a procedure for rapid freezing before freeze-fracture and deep-etching. Journal of Neurocytology. 1991;20:471–484. doi: 10.1007/BF01252275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank G, Hemmert W, Gummer AW. Limiting dynamics of high-frequency electromechanical transduction of outer hair cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:4420–4425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolenkov GI, Coling D, Mammano F, Kachar B. 22nd Midwinter Meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. Florida: St Petersburg; 1999. The voltage-dependence of electromotility mechanism in cochlear outer hair cells is modulated by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphorylation; p. 732. [Google Scholar]

- Gale JE, Ashmore JF. Charge displacement induced by rapid stretch in the basolateral membrane of the guinea pig outer hair cell. Proceedings of the Royal Society. 1994;255:243–249. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0035. B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale JE, Ashmore JF. The outer hair cell motor in membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1997a;434:267–271. doi: 10.1007/s004240050395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale JE, Ashmore JF. An intrinsic frequency limit to the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 1997b;389:63–66. doi: 10.1038/37968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He DZZ, Evans BN, Dallos P. First appearance and development of electromotility in neonatal gerbil outer hair cells. Hearing Research. 1994;78:77–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley CM, Owings MH, Stagner BB, Martin GK, Lonsbury-Martin BL. Postnatal development of 2f1-f2 otoacoustic emissions in pigmented rat. Hearing Research. 1989;43:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90223-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington JD, Newton KR, Bookman RJ. PulseControl V4.7: IGOR XOPs for Patch Clamp Data Acquisition and Capacitance Measurements. Miami, FL: University of Miami; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Ball R. Regulation of cardiac Na+, Ca2+ exchange and KATP potassium channels by PIP2. Science. 1996;273:956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley MC, Ashmore JF. On the mechanism of a high frequency force generator in outer hair cells isolated from the guinea pig cochlea. Proceedings of the Royal Society. 1988;232:413–429. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1988.0004. B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley MC, Kalinec F, Kachar B. Structure of the cortical cytoskeleton in mammalian outer hair cells. Journal of Cell Science. 1992;102:569–580. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Santos-Sacchi J. Mapping the distribution of the outer hair cell motility voltage sensor by electrical amputation. Biophysical Journal. 1993a;65:2228–2236. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81248-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Santos-Sacchi J. 16th Midwinter Meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. Florida: St Petersburg; 1993b. Metabolic control of OHC function: phosphorylation and dephosphorylation agents shift the voltage dependency of motility related capacitance; pp. 4–64. [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Santos-Sacchi J. Motility voltage sensor of the outer hair cell resides within the lateral plasma membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:12268–12272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;80:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa KH. Effect of stress on the membrane capacitance of the auditory outer hair cell. Biophysical Journal. 1993;65:492–498. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81053-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa KH. A membrane motor model for the fast motility of the outer hair cell. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1994;96:2216–2224. doi: 10.1121/1.410094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehata S, Santos-Sacchi J. Membrane tension directly shifts voltage dependence of outer hair cell motility and associated gating charge. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68:2190–2197. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80401-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinec F, Holley MC, Iwasa KH, Lim DJ, Kachar B. A membrane based force generation mechanism in auditory sensory cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:8671–8675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Marty A. Discrete changes of cell membrane capacitance observed under conditions of enhanced secretion in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1982;79:6712–6716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton SJ, Bargones JY, Rubel EW. Development of otoacoustic emissions in gerbil: Evidence for micromechanical changes underlying development of the place code. Hearing Research. 1991;51:73–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90008-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver D, Plinkert P, Zenner HP, Ruppersberg JP. Sodium current expression during postnatal development of rat outer hair cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1997;434:772–778. doi: 10.1007/s004240050464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol R, Zajic G, Dulon D, Raphael Y, Altschuler RA, Schacht J. First appearance and development of motile properties in outer hair cells isolated from guinea-pig cochlea. Hearing Research. 1991;57:129–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90082-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ, Richardson GP. The morphology and physiology of hair cells in organotypic cultures of the mouse cochlea. Hearing Research. 1987;31:9–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak LP, Whitworth C, Scott V. Development of endocochlear potential and compound action potential in the rat. Hearing Research. 1992;59:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J. Reversible inhibition of voltage-dependent outer hair cell motility and capacitance. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:3096–3110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03096.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J, Dilger JP. Whole cell currents and mechanical responses of isolated outer hair cells. Hearing Research. 1988;35:143–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J, Kakehata S, Takahashi S. Effects of membrane potential on the voltage dependence of motility-related charge in outer hair cells of the guinea-pig. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:225–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.225bz.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souter M, Nevill G, Forge A. Postnatal development of membrane specialisations of gerbil outer hair cells. Hearing Research. 1995;91:43–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall MJ, Gale JE, Ashmore JF. Action of salicylate on membrane capacitance of outer hair cells from the guinea-pig cochlea. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;485:739–752. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SP, Schweitzer L. Development of gerbil outer hair cells after the onset of cochlear function: an ultrastructural study. Hearing Research. 1994;72:44–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf NK, Ryan AF. The development of auditory function in the cochlea of the mongolian gerbil. Hearing Research. 1984;13:277–283. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]