Abstract

The transient outward K+ current (Ito) is a major repolarizing ionic current in ventricular myocytes of several mammals. Recently it has been found that its magnitude depends on the origin of the myocyte and is regulated by a number of physiological and pathophysiological signals.

The relationship between the magnitude of Ito, action potential duration (APD) and Ca2+ influx (QCa) was studied in rat left ventricular myocytes of endo- and epicardial origin using whole-cell recordings and the action potential voltage-clamp method.

Under control conditions, in response to a depolarizing voltage step to +40 mV, Ito averaged 12.1 ± 2.6 pA pF−1 in endocardial (n = 11) and 24.0 ± 2.6 pA pF−1 in epicardial myocytes (n = 12; P < 0.01). APD90 (90 % repolarization) was twice as long in endocardial myocytes, whereas QCa inversely depended on the magnitude of Ito. L-type Ca2+ current density was similar in myocytes from both regions.

To determine the effects of controlled reductions of Ito on QCa, recordings were repeated in the presence of increasing concentrations of the Ito inhibitor 4-aminopyridine.

Inhibition of Ito by as little as 20 % more than doubled QCa in epicardial myocytes, whereas it had only a minor effect on QCa in myocytes of endocardial origin. Further inhibition of Ito led to a progressive increase in QCa in epicardial myocytes; at 90 % inhibition of Ito, QCa was four times larger than the control value.

We conclude that moderate changes in the magnitude of Ito strongly affect QCa primarily in epicardial regions. An alteration of Ito might therefore allow for a regional regulation of contractility during physiological and pathophysiological adaptations.

Changes in shape and duration of the action potential (AP) have a strong influence on cardiac contractility (Wood et al. 1969). Fedida & Bouchard (1992) identified an increased action potential duration (APD), induced by a reduction in K+ currents, as the main cause for increased intracellular Ca2+ transients and contractions observed in isolated rat left ventricular myocytes under α1-adrenergic stimulation. Bouchard et al. (1995) investigated the effects of an increased APD on Ca2+ influx, Ca2+ release and cardiac contractility, and found an increased Ca2+ influx to be the primary cause for the subsequent increase in Ca2+ release and enhanced contractility.

The transient outward K+ current (Ito) is a major repolarizing ionic current in ventricular myocytes of several species (Josephson et al. 1984; Giles & Imaizumi, 1988; Litovsky & Antzelevitch, 1988; Beuckelmann et al. 1993; Varro et al. 1993; Wettwer et al. 1993). Accordingly, its inhibition leads to a significant prolongation of the AP (Josephson et al. 1984; Mitchell et al. 1984). Recently, several studies have demonstrated that the magnitude of Ito is considerably altered in response to a number of physiological and pathophysiological influences like α1-adrenergic activation (Apkon & Nerbonne, 1988), cardiac hypertrophy (Tomita et al. 1994), heart failure (Näbauer et al. 1993), hypo- or hyperthyroidism (Shimoni et al. 1992, 1995), diabetes (Jourdon & Feuvray, 1993), anoxia (Thierfelder et al. 1994) and development (Jeck & Boyden, 1992). This suggests that changes in the magnitude of Ito might constitute a pathway for altering APD and consequently Ca2+ influx and cardiac contractility. Moderate reductions in Ito have been observed in several pathophysiological conditions (Wickenden et al. 1998; Näbauer & Kääb, 1998), but the effects of this reduction on Ca2+ influx in different regions of the left ventricle have not yet been investigated.

We therefore used whole-cell recordings and the AP voltage-clamp method to analyse the quantitative effects of a graded inhibition of Ito on the shape and size of Ca2+ influx. Since Ito is not uniformly expressed in the left ventricle (Litovsky & Antzelevitch, 1988; Fedida & Giles, 1991; Clark et al. 1993; Wettwer et al. 1994), we have separately investigated myocytes from endocardial and epicardial regions.

METHODS

Isolation of myocytes

Female Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 180-220 g, were anaesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of Inactin (thiobutabarbital-sodium, 100 mg (kg body mass)−1; Byk Gulden, Konstanz, Germany). The heart was quickly excised and placed into cold (4°C) cardioplegic solution, where it stopped beating immediately. Left ventricular myocytes were isolated according to the method described by Isenberg & Klockner (1982). Briefly, the aorta was cannulated and retrogradedly perfused with nominally Ca2+-free modified Tyrode solution at 37°C for 5 min. Perfusion pressure was 75 mmHg, and all solutions were bubbled with 100 % oxygen. The perfusion was continued for 15 min with 20 ml of the same solution containing collagenase (Type CLS II, 200 U ml−1; Biochrom KG, Berlin, Germany) and protease (Type XIV, 0.7 U ml−1; Sigma), and the solution was recirculated. Finally, the heart was perfused with modified Tyrode solution containing 100 μm Ca2+ for another 5 min. After the perfusion, the left ventricular free wall was separated from the rest of the heart, and epi- and endocardial tissue was carefully isolated from the left ventricular free wall with fine forceps and placed into separate cups. To further disaggregate the tissue pieces, they were gently shaken at 37°C for some minutes, filtered through a cotton mesh and allowed to settle for half an hour. Cells were stored at room temperature in modified Tyrode solution containing 100 μm Ca2+. Only single rod-shaped cells with clear cross striations and no spontaneous contractions were used for experiments. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved by local authorities (permit no. 37-9185.81/114/95).

Solutions and chemicals

Cardioplegic solution contained (mM): NaCl 15, KCl 9, MgCl 4, NaH2PO4 0.33, CaCl2 0.015, glucose 10, mannitol 238, titrated to pH 7.40 with NaOH. Gigaohm seals were obtained in modified Tyrode solution (control solution; mM): NaCl 138, KCl 4, MgCl2 1, NaH2PO4 0.33, CaCl2 2, glucose 10, Hepes 10, titrated to pH 7.30 with NaOH. To inhibit Ca2+ currents, CdCl2 0.3 mM was added to the solution. Solutions containing 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) were freshly prepared on the day of the experiment and corrected for pH. The pipette solution contained (mM): glutamic acid 120 (titrated with KOH and thus resulting in potassium glutamate 120), KCl 10, MgCl2 2, EGTA 10, Na2-ATP 2, Hepes 10, titrated to pH 7.20 with KOH. In some experiments a pipette solution without Ca2+ buffering was used, containing (mM): glutamic acid 130 (titrated with KOH and thus resulting in potassium glutamate 130), KCl 10, MgCl2 2, EGTA 0.5, titrated to pH 7.20 with KOH. Free Ca2+ was calculated to be 0.1 μm in this solution (glutamic acid contained ∼0.02 % Ca2+, therefore 0.5 mM EGTA was added; myocytes patched with this solution in the pipette contracted upon depolarization throughout the experiment).

Na2-ATP, 4-AP and CdCl2 were purchased from Sigma, glucose, KCl, MgCl2, NaCl and NaOH from Merck, CaCl2 from J. T. Baker (Deventer, The Netherlands), EGTA from Boehringer Mannheim, glutamic acid from Fluka and KOH was purchased from Riedel de Haen (Seelze, Germany).

Patch-clamp technique

The ruptured-patch whole-cell configuration was used as described previously (Hamill et al. 1981). Myocardial cells were transferred to an elongated chamber (2.5 mm × 20 mm), mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Axiovert 25, Zeiss, Jena, Germany), and initially superfused with control solution. All experiments were performed at room temperature (22-26°C). During recordings, liquid flow was stopped to minimize electric noise. The flow rate was 15 ml min−1 and solution exchange of the bath was achieved within seconds. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (GC150-15, Clark Electromedical Instruments) using a P-87 Puller (Sutter Instruments). Pipette resistance (Rpip) averaged 3.6 ± 0.1 MΩ (n = 38) with potassium glutamate in the pipettes and control solution in the bath.

Currents were recorded using an EPC-9 amplifier (HEKA Elektronik), controlled by a Power-Macintosh (Apple Computer) and the Pulse-Software (HEKA Elektronik). Membrane voltage (Vm) and APs were recorded in the zero current-clamp mode and ionic currents in the voltage-clamp mode. For AP voltage-clamp recordings, APs were recorded at the beginning of the experiments and used as a voltage template in the voltage-clamp mode of the amplifier (Doerr et al. 1989). Membrane capacitance (Cm) and series resistance (Rs) were calculated using the automated capacitance compensation procedure of the EPC-9 amplifier. Rs averaged 6.5 ± 0.3 MΩ (n = 38) and was compensated by 85 % leading to an average effective Rs of ∼1.0 MΩ. Accordingly, at the largest recorded currents of about 6 nA observed at a pipette potential (Vpip) of +60 mV, the voltage error was less than 6 mV or 10 %. Cm averaged 120.5 ± 5.8 pF (n = 35) and was similar in both endo- and epicardial myocytes. The reference electrode of the amplifier headstage was bathed in pipette solution in a separate chamber and was connected to the bath solution via an agar-agar bridge filled with pipette solution. Vpip and Vm were corrected for liquid junction potentials occurring at the bridge-bath junction (13.3 mV for potassium glutamate pipette solution and control solution in the bath). Whole-cell currents were low-pass filtered at 1 kHz and sampled at 5 kHz. APs were sampled at 1 kHz. Whole-cell data were analysed using the Pulse-Fit (HEKA Elektronik) and IGOR (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA) software. Data are given as means ±s.e.m., and n is the number of experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using the appropriate version of Student's t test or the Mann-Whitney U test after an initial two-way ANOVA using the software PRISM (Graph-Pad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Identification and separation of currents

The Ca2+-independent depolarization-induced outward current observed in rat ventricle has been separated into two distinct K+ currents: a rapidly inactivating component (Ito) and a sustained (steady-state) component (Iss) (Apkon & Nerbonne, 1991). Ito is sensitive to 4-AP, while Iss is blocked by tetraethylammonium (TEA). Nevertheless, quantification and separation of the two components has been a matter of debate (Shimoni et al. 1995), because both currents are rate dependent and inhibition of Ito by 4-AP shows a reverse use dependence resulting in a reduced inhibition at higher stimulation rates (Campbell et al. 1993). We therefore used a low stimulation rate of 0.33 Hz or less for all voltage-clamp, AP voltage-clamp or AP recordings. Ito was calculated as the transient component of the outward current, that is the difference between the peak and the steady-state current, which correlates quite well with the 4-AP-sensitive current (data not shown) and thus gives a good estimate for Ito.

Using the AP voltage-clamp method, AP-induced Ca2+ currents and Ca2+ influx were estimated by subtracting recordings made in the presence of 300 μm Cd2+ in the bath solution from those in the absence of Cd2+. This difference represents the Cd2+-sensitive current. Cd2+ at a concentration of 300 μm is a relatively non-specific blocker of Ca2+ channels (Fox et al. 1987) but has only minor effects on Ito, whereas other, more specific inhibitors of Ca2+ channels like dihydropyridines or D600 are potent inhibitors of Ito (Gotoh et al. 1991; Lefevre et al. 1991). Cd2+ also inhibits the Na+-Ca2+ exchange current (Kimura et al. 1987) and the currents depending on Ca2+ influx. Therefore, the pipette solution contained 10 mM of the Ca2+ chelator EGTA, which should have been sufficient to prevent Ca2+-dependent currents from activating. In the absence of intracellular Ca2+, the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger does not contribute to the whole-cell current (Allen & Baker, 1985). Since previous studies (Tytgat et al. 1990; Bouchard et al. 1995) could not identify T-type currents in rat left ventricle, their contribution to the Cd2+-sensitive component is very unlikely. Because we wanted to evaluate the influence of Ito on the AP-induced Ca2+ influx, we could not replace intracellular K+ by impermeable cations.

Ito is known to be influenced by divalent cations (Agus et al. 1991): at a concentration of 300 μm, Cd2+ shifts the steady-state activation and inactivation curves by about 15-20 mV to more positive potentials. Maximal activation of Ito, however, is observed at about Vm= 20 mV. This value was always exceeded in the AP voltage-clamp experiments, since the overshoot of the rat AP reaches values of about Vm= 30 mV. Furthermore, we started the AP voltage-clamp experiments from the normal resting membrane potential of Vm= -90 mV, which is out of range of the steady-state inactivation. Thus, the influence of a 20 mV shift in the steady-state activation and inactivation on the present results should be minimal.

Subtracting current recordings made in the absence of Ca2+ from those made with Ca2+ present in the bath solution is another way of estimating Ca2+ currents. However, Ito-like K+ currents, which are activated by removal of external Ca2+, have been described (Inoue & Imanaga, 1993) and therefore this protocol can only be used in the absence of internal K+ to suppress these currents. Finally, Ca2+ currents typically exhibit run-down during an experiment. Scamps et al. (1990) found a reduction in Ca2+ currents of less than 10 % within 30 min. In our experiments, the estimation of Ca2+ currents was usually performed within the first 10 min, and therefore run-down is negligible. We conclude therefore that under our experimental conditions the Cd2+-sensitive currents appear to give the best estimate of the L-type Ca2+ current.

RESULTS

Transient outward K+ current

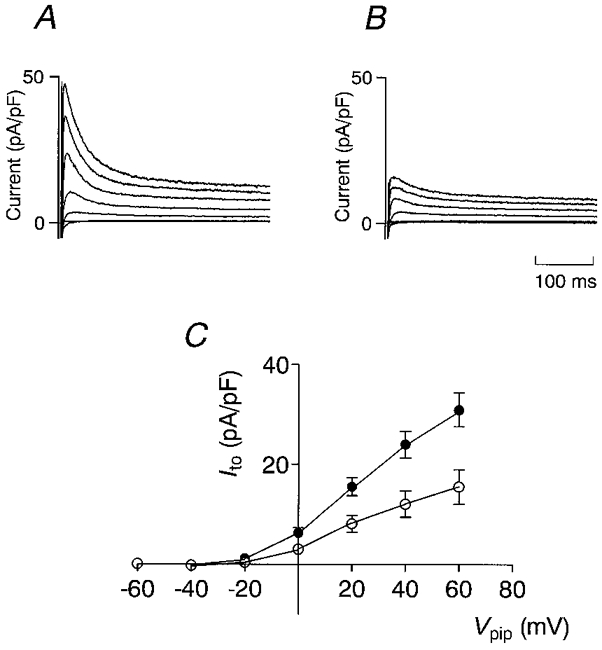

At the beginning of each experiment, after the conventional ruptured patch whole-cell configuration was established, the resting membrane potential was recorded in the zero current-clamp mode of the amplifier. The average Vm was -87.0 ± 0.4 mV (n = 36, no. of rats = 11) and was not significantly different in endo- and epicardial myocytes. Only cells with a Vm of at least -85 mV were used for experiments. Panels A and B in Fig. 1 show representative current recordings of Ito in, respectively, an epicardial and an endocardial myocyte, activated by depolarizing voltage pulses. Sodium currents were inactivated by an initial depolarization to Vpip= -50 mV for 20 ms, and Ca2+ currents were inhibited by the presence of 300 μm Cd2+ in the bath solution. Ito activated at pipette potentials above Vpip= -20 mV and continued to increase up to Vpip= 60 mV. Ito was much larger in the epicardial myocyte, but had similar activation and inactivation properties in both cells. Figure 1C shows average current-voltage (I-V) relations of Ito recorded in 11 endocardial and 12 epicardial myocytes. Ito was quantified as the difference between the peak current and the current at the end of the voltage pulse (after 600 ms; see Methods). Currents were normalized to cell capacitance to correct for different cell sizes and are thus given in picoamps per picofarad (pA pF−1). The threshold of activation was around Vpip= -20 mV in myocytes of both regions, and Ito increased linearly up to the maximal applied voltage of Vpip= 60 mV. At Vpip= 40 mV, Ito averaged 12.1 ± 2.6 pA pF−1 in endocardial myocytes and 24.0 ± 2.6 pA pF−1 in epicardial myocytes (P < 0.01). The current decay was best fitted monoexponentially and the inactivation time constant was identical in both regions (33.2 ± 1.8 ms in endocardial and 32.9 ± 3.5 ms in epicardial myocytes at Vpip= 40 mV).

Figure 1. Magnitude of Ito in epi- and endocardial myocytes.

Representative outward currents recorded from an epicardial (A) and an endocardial (B) myocyte. Current was normalized to cell capacitance to compensate for different cell sizes. Currents were activated by voltage pulses of 600 ms duration from a holding potential of -90 mV to values ranging from -60 to +60 mV in steps of 20 mV. Prior to each depolarization, Vm was clamped on -50 mV for 20 ms to inactivate Na+ currents. C, average I-V relation of Ito recorded from 12 epicardial (•) and 11 endocardial (○) myocytes. Ito was quantified by subtracting the current at the end of the voltage pulse (600 ms) from the peak current.

AP, Ito and Ca2+ influx in endo- and epicardial myocytes

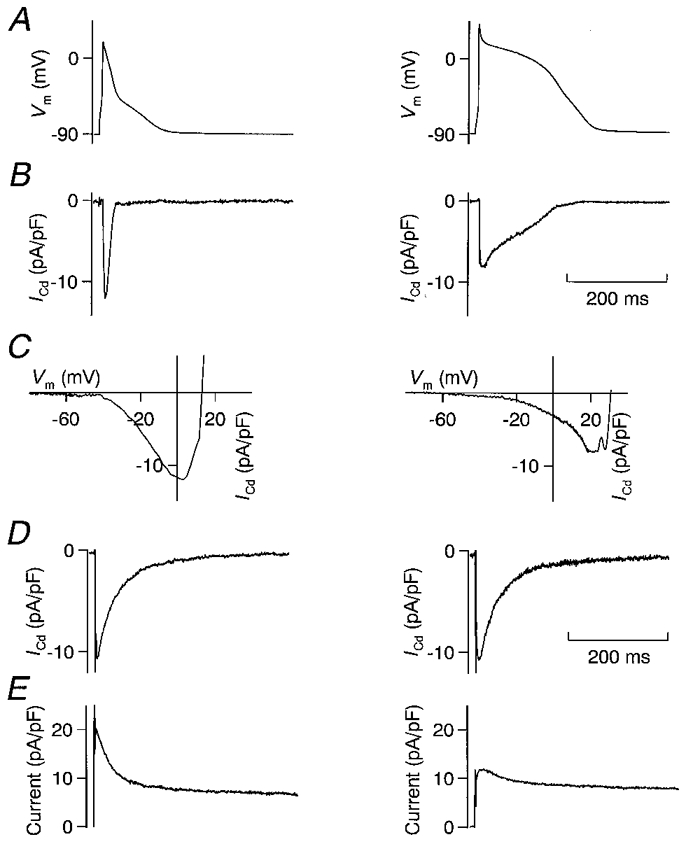

Figure 2 compares APs, AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive currents, Ito and Cd2+-sensitive currents activated by a rectangular voltage step to Vpip= 0 mV in representative endo- and epicardial myocytes; average results are summarized in Table 1. The epicardial AP showed a pronounced early repolarization, whereas the endocardial AP was considerably longer and the plateau potential was more positive (Fig. 2A). The strong early repolarization observed in epicardial myocytes is reflected in APD0 mV (i.e. the time span from AP upstroke until Vm falls to below 0 mV), which was on average about three times shorter (27.9 ± 8.5 ms, n = 13) than in endocardial myocytes (85.2 ± 20.6 ms, n = 11, P < 0.05). The APD90 (i.e. the time span from AP upstroke until 90 % repolarization) differed only by a factor of two (118 ± 20 vs. 209 ± 38 ms, P < 0.05).

Figure 2. AP voltage-clamp recordings from epi- and endocardial myocytes.

A, APs recorded in a representative epicardial (left) and endocardial (right) myocyte. Early repolarization was much stronger in the epicardial myocyte. B, Cd2+-sensitive current recorded with the AP voltage-clamp method using the APs depicted in A. Peak current was higher in the epicardial myocyte, but total QCa (integral of the current) was much higher in the endocardial myocyte. C, I-V relation, drawn using the AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive current (B) and the corresponding AP (A). The peak of the inward current was recorded at a more positive potential in the endocardial myocyte (20 vs. 5 mV). D, Cd2+-sensitive current, activated by a rectangular depolarizing voltage pulse to 0 mV. The Na+ current was inactivated by a 20 ms step from a holding potential of -90 mV to -50 mV. Activated by the same command potential, Cd2+-sensitive currents were similar in size and inactivation kinetics in the epi- and endocardial myocyte. E, outward current, activated by a rectangular depolarizing voltage pulse to +40 mV. The Na+ current was inactivated by a 20 ms step from a holding potential of -90 mV to -50 mV. Ito was much more prominent in the epicardial myocyte, which explains the strong early repolarization and the smaller QCa. All recordings were made in the same epi- or endocardial myocyte.

Table 1.

Average properties of APs and AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive currents

| Myocyte | Vm (mV) | Overshoot (mV) | APD0 mV (ms) | APD90 (ms) | QCa (fC pF−1) | ICd,peak (pA pF−1) | Vm,peak (mV) | Ito(40 mV) (pA pF−1) | ICa(0 mV) (pA pF−1) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epicardial | −88.2 ± 0.5 | 29.4 ± 2.6 | 27.9 ± 8.5* | 118 ± 20* | 250 ± 71* | 11.5 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 2.5* | 24.0 ± 2.6†‡ | 15.1 ± 1.2‡ | 13 |

| Endocardial | −87.3 ± 0.5 | 33.8 ± 3.5 | 85.2 ± 20.6 | 209 ± 38 | 526 ± 107 | 10.2 ± 0.5 | 14.2 ± 3.4 | 12.1 ± 2.6 | 13.4 ± 0.9 | 11 |

Vm, Overshoot, APD0mV and APD90 were calculated from the AP used for the AP voltage-clamp recording in each experiment. QCa, ICd,peak and Vm,peak were calculated using AP-induced Cd2+ -sensitive current. Ito was estimated at Vpip = +40 mV, ICa was estimated as the Cd2+ sensitive current recorded using a rectangular voltage pulse to Vpip = 0 mV as described in Fig. 2.

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

n = 12.

Figure 2B shows Cd2+-sensitive currents recorded with the AP voltage-clamp method. The duration of the Cd2+-sensitive current was much greater in the endocardial than in the epicardial myocyte. Total Ca2+ influx (QCa), calculated as the integral of the AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive current and normalized to the cell capacitance, was larger in the endocardial cell; average values were 526 ± 107 fC pF−1 (n = 11) in endocardial myocytes and 250 ± 71 fC pF−1 (n = 13) in epicardial myocytes (P < 0.05). Average peak currents were not significantly different between both regions (epicardial, 11.5 ± 0.8 pA pF−1, n = 13; endocardial, 10.2 ± 0.5 pA pF−1, n = 11; P = 0.14).

The I-V relations shown in Fig. 2C were computed using the cell's AP and the corresponding AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive current. It should be noted that they differ from the classical bell-shaped I-V relation of L-type Ca2+ currents in that their shape also depends on the time-dependent activation and inactivation properties of the Ca2+ channels. Thus, the magnitude of the current recorded depends not only on the Vm at which it is recorded, but also on the time when Vm is reached during the AP. These I-V curves explain the differences in the peak of the AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive currents: in the epicardial myocyte, the current peaked at Vpip= 5 mV, whereas it peaked at Vpip= 20 mV in the endocardial myocyte. The bell-shaped I-V relation of the L-type Ca2+ current has its maximum around 0 mV (McDonald et al. 1994), thus the AP-induced Ca2+ current would be maximal if the membrane potential was 0 mV immediately after the overshoot, when the open probability of the Ca2+ channels is maximal. The strong early repolarization to values of Vm≈ 0 mV in the epicardial myocytes favours a high peak Ca2+ current. In contrast, the weaker early repolarization observed in endocardial myocytes leads to more depolarized plateau potentials and thus a lower electrochemical driving force for Ca2+ ions. The average values for Vm, at which the peak AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive current was observed (Vm,peak), were 2.4 ± 2.5 mV in epicardial myocytes and 14.2 ± 3.4 mV in endocardial myocytes (P < 0.05). Although in endocardial myocytes Vm,peak was significantly higher than in epicardial myocytes, both values were close to the maximum of the bell-shaped L-type Ca2+ current I-V. This explains why the average peak values of the AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive currents were not significantly different.

Figure 2D depicts Cd2+-sensitive currents activated by rectangular voltage pulses to Vm= 0 mV. Current magnitude averaged 15.1 ± 1.2 pA pF−1 in epicardial (n = 12) and 13.4 ± 0.9 pA pF−1 in endocardial myocytes (n = 11). Similar results have been obtained by Clark et al. (1993) using Cs2+ as the main cation in the pipette solution. This demonstrates that L-type Ca2+ current density is not different between both regions and thus cannot account for the differences in Ca2+ influx. Figure 2E shows the Ito from the same myocytes activated by depolarizing voltage steps to Vpip=+40 mV. Ito was much smaller in the endocardial myocyte (5 pA pF−1) than in the epicardial myocyte (18 pA pF−1), whereas the steady-state currents at the end of the voltage pulse had similar values. The average values for Ito, Ca2+ influx and APD demonstrate that in endocardial myocytes, where Ito is low, Ca2+ influx and APD are high, whereas in epicardial myocytes, where Ito is high, Ca2+ influx and APD are low (see Table 1). It appears that Ca2+ influx depends on the magnitude of Ito, and that a modulation of Ito may affect Ca2+ influx.

Quantification of the effect of 4-AP on Ito

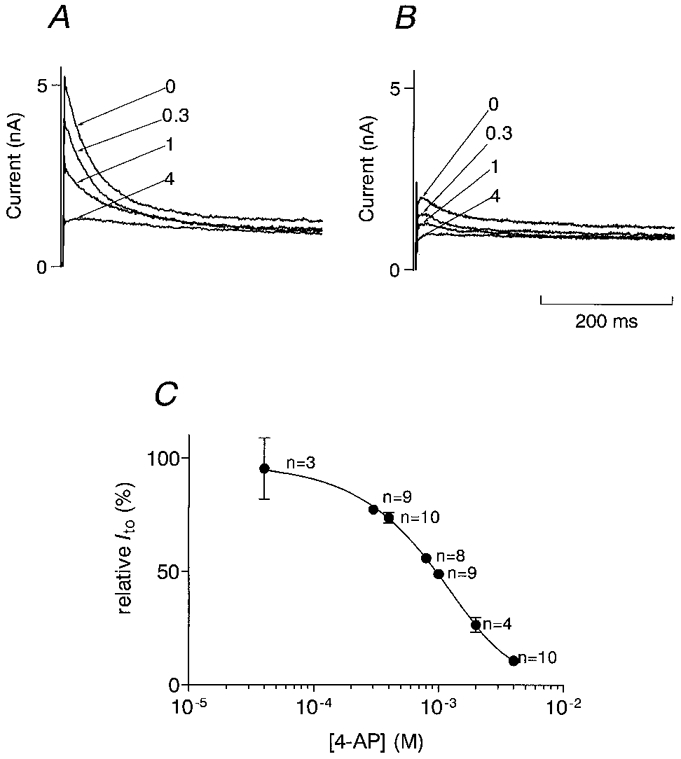

4-AP is an inhibitor of Ito with a well-characterized pharmacology (Castle & Slawsky, 1993). In the present study, we wanted to use 4-AP for a graded inhibition of Ito and therefore established a dose-response relation to estimate the inhibitory effect of defined concentrations of 4-AP under our experimental conditions. Figure 3A and B illustrates the effect of 4-AP on Ito in endo- and epicardial myocytes. The bath solution did not contain Cd2+. Current traces were activated by depolarizing voltage pulses to Vpip=+60 mV, which corresponds to the reversal potential of the Ca2+ current. In similar experiments with Cd2+ in the bath solution we could show that the presence of Cd2+ does not influence the effect of 4-AP on Ito (data not shown). Increasing concentrations of 4-AP progressively suppressed Ito until it was almost completely inhibited at 4 mM (Fig. 3A and B). Since we could not detect any differences in the inhibitory effect of 4-AP on Ito between endo- and epicardial myocytes, all experiments were pooled (Fig. 3C). The dose- response relation was fitted assuming Michaelis-Menten kinetics for the effect of 4-AP on Ito.

Figure 3. Dose-response relation between 4-AP and Ito.

Effects of different concentrations of 4-AP on outward currents recorded in an epicardial (A) and an endocardial (B) myocyte. Cell capacitance of both myocytes was similar (133 pF in the epicardial, 137 pF in the endocardial myocyte). Currents were activated by a depolarizing rectangular voltage pulse from a holding potential of -90 mV to -50 mV for 20 ms to inactivate Na+ currents, and then to +60 mV. The numbers indicate the concentration of 4-AP (mM) in the bath solution. C, dose-response relation between 4-AP and Ito. Ito observed in the presence of 4-AP was normalized to Ito recorded in the absence of 4-AP in each individual myocyte. The graph contains data from endo- and epicardial myocytes. The data were fitted assuming Michaelis-Menten kinetics for the effect of 4-AP. IC50 was 0.98 mM.

Influence of inhibition of Ito on AP and Ca2+ influx in endo- and epicardial myocytes

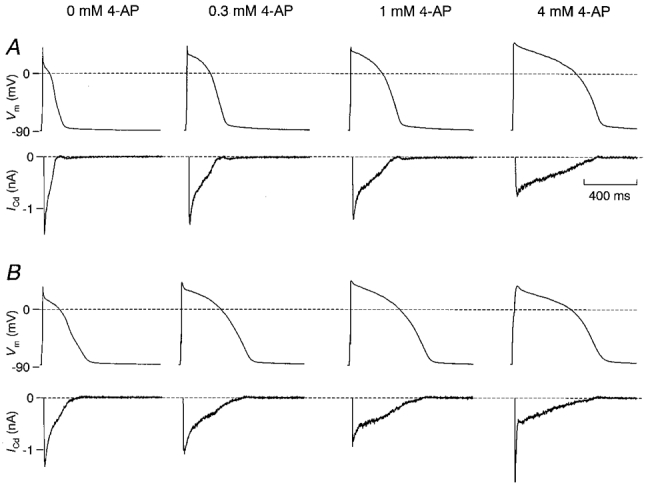

To evaluate the effect of an inhibition of Ito on Ca2+ influx, the following experimental protocol was used: after establishing the whole-cell configuration, APs were recorded under control conditions and in the presence of 0.3, 1 and 4 mM 4-AP, which corresponds to an inhibition of Ito by 0, 20, 50 and 86 % as demonstrated in Fig. 3C. Subsequently, by using the AP voltage-clamp method, the membrane potential was clamped on these four APs in the absence and presence of Cd2+ in the bath solution. Subtraction of the corresponding currents revealed the AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive currents for each AP. Figure 4 shows APs and corresponding AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive currents under increasing inhibition of Ito in a representative epicardial (Fig. 4A) and endocardial (Fig. 4B) myocyte. 4-AP had no effect on the resting membrane potential. Under control conditions, the AP of the endocardial myocyte was longer than that of the epicardial myocyte (see also Fig. 2), and the plateau potential was more positive. However, with increasing inhibition of Ito, the increase in APD and plateau potential in the epicardial myocyte was greater than in the endocardial myocyte. At maximal inhibition of Ito by 4 mM 4-AP, both APs had approximately the same duration and plateau potential. The peak of the AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive currents decreased with increasing inhibition of Ito, but the duration of the current increased. Both effects were more pronounced in the epicardial myocyte. The high peak current observed in the endocardial myocyte at 4 mM 4-AP is an artefact due to a sudden increase in access resistance during the AP recording. The resultant slow upstroke of this AP led to an artificial high peak current which was not recorded in other similar experiments.

Figure 4. Influence of inhibition of Ito on APs and AP-induced Ca2+ currents in epi- and endocardial myocytes.

A, APs and corresponding AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive currents recorded in a representative epicardial myocyte subjected to increasing inhibition of Ito with 4-AP. B, similar recordings in an endocardial myocyte. Cell capacitance was similar with 136 pF in the epicardial and 144 pF in the endocardial myocyte. The resting membrane potential was not affected by 4-AP. With increasing concentrations of 4-AP in the bath solution, APs became longer and the plateau potential increased. The increase in APD was accompanied by an increased duration, but reduced peak of the AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive current. These effects were more pronounced in the epicardial myocyte. With maximal inhibition of Ito, APs and AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive currents were similar in both myocytes. Artefacts in the current recordings prior to the activation of the Cd2+-sensitive current resulting from capacitive and Na+ currents were cut away. The spike of the AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive current recorded from the endocardial myocyte at 4 mM 4-AP is an artefact secondary to the slow upstroke of the corresponding AP and was not observed in similar recordings.

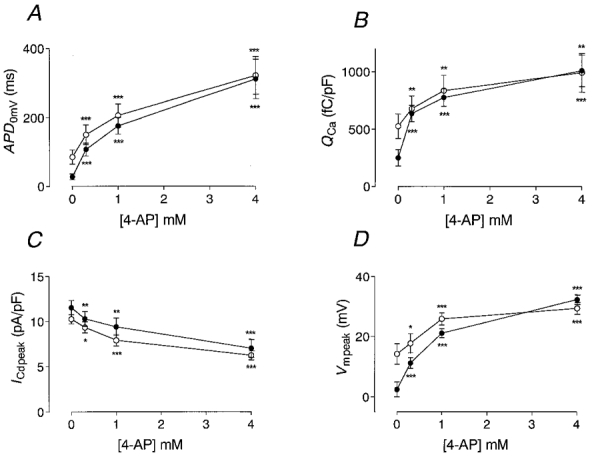

Figure 5A summarizes similar results obtained in 11 endocardial and 13 epicardial myocytes. Under control conditions, APD0 mV was three times longer in endocardial myocytes than in epicardial myocytes. With increasing inhibition of Ito, APD0 mV increased in both cell types until similar values were reached at maximal inhibition. In Fig. 5B, Ca2+ influx is plotted versus the concentration of 4-AP in the bath solution. Under control conditions, Ca2+ influx was significantly larger in endocardial myocytes. Inhibition of Ito by 20 % (0.3 mM 4-AP) more than doubled Ca2+ influx from an average of 250 ± 71 to 636 ± 72 fC pF−1 in epicardial myocytes (P < 0.001). In myocytes of endocardial origin, the effect of inhibition of Ito was much less pronounced: at 20 % inhibition, Ca2+ influx increased by a factor of 1.3 from 526 ± 107 to 678 ± 112 fC pF−1 (P < 0.01). With maximal inhibition of Ito, Ca2+ influx increased by a factor of 4.0 to 1011 ± 136 fC pF−1 in epicardial myocytes (P < 0.001), but only by a factor of 1.9 to 994 ± 168 fC pF−1 in endocardial myocytes (P < 0.01). Interestingly, at 20 % inhibition of Ito, Ca2+ influx attained similar values in epi- and endocardial myocytes.

Figure 5. Effect of inhibition of Ito on APD0mV, QCa, ICd,peak and Vm,peak in epi- and endocardial myocytes.

Curves were calculated from average data recorded in every experiment. Single recordings were made similar to those shown in Fig. 4. The effects of 0, 0.3, 1 and 4 mM 4-AP on APD0 mV (A), QCa (B), the peak AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive current (ICd,peak) (C), and the membrane voltage at which ICd,peak was recorded (Vm,peak) (D) are illustrated. •, data recorded in epicardial myocytes; ○, data recorded in endocardial myocytes. ICd,peak was estimated as the maximal inward current after the initial capacitive current. Note that differences between epicardial and endocardial myocytes disappear with increasing inhibition of Ito. Significance of difference from control values (0 mM 4-AP) was tested using Student's paired t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Figure 5C illustrates the effect of inhibition of Ito on the peak of the AP-induced Cd2+-sensitive current. With increasing inhibition of Ito, the peak current decreased significantly in both endo- and epicardial myocytes. At maximal inhibition of Ito, the peak current was reduced by about 50 %. In parallel with the decrease in the peak Cd2+-sensitive current, the membrane potential at which the peak Cd2+-sensitive current was observed during the AP (Vm,peak) increased (Fig. 5D). Under control conditions, Vm,peak was higher in endocardial myocytes, while peak Cd2+-sensitive current was lower (see Fig. 2C). With maximal inhibition of Ito, Vm,peak increased by 29.9 ± 2.0 mV in epicardial and by 15.9 ± 3.0 mV in endocardial myocytes (P < 0.001). Thus, progressive inhibition of Ito led to a higher plateau potential which reduced the driving force for the AP-induced Ca2+ current. This effect was more pronounced in epicardial myocytes.

DISCUSSION

The present investigation demonstrates that a differential distribution of Ito is the most important cause for different AP waveforms in endo- and epicardial myocytes from adult rat left ventricle. Furthermore, the results indicate that the magnitude of Ito has a major impact on Ca2+ transients and the amount of Ca2+ influx during an AP.

Accuracy of estimated Ca2+ influx

We tried to quantify AP-induced Ca2+ currents and Ca2+ influx under as much physiological conditions as possible. The composition of internal and external solutions resembled mostly the normal distribution of ions. However, some compromises had to be made. Internal Ca2+ was buffered using 10 mM EGTA in the pipette solution to inhibit Ca2+-dependent currents (as discussed in Methods). Buffering of internal Ca2+ may slow L-type Ca2+ current inactivation in two ways: first, Ca2+ ions entering the cell via L-type channels are buffered and thus cannot bind to the proposed Ca2+-binding site of the channel (de-Leon et al. 1995); second, Ca2+ release into the fuzzy space close to the L-type channel is prevented by emptying of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Sham, 1997). However, the normal Ca2+-induced inactivation is well preserved, even in the presence of EGTA, probably because the proposed Ca2+-binding site is close to the channel mouth and cannot be reached quickly enough by EGTA (de-Leon et al. 1995). Furthermore, using the AP voltage-clamp method, Linz & Meyer (1998) demonstrated that Ca2+ currents recorded in the presence of 10 mM EGTA in the pipette solution differed only slightly in the late phase of the AP from those recorded in the absence of internal Ca2+ buffering. Finally, we performed experiments with minimal internal Ca2+ buffering (0.5 mM EGTA, free [Ca2+]= 100 nM) and found a similar increase in Ca2+ influx induced by inhibition of Ito in epicardial myocytes compared with that found in the experiments in which 10 mM EGTA was present in the pipette solution (n = 4, data not shown).

Because we used 4-AP to inhibit Ito in order to determine its contribution to APD and Ca2+ influx, a key question concerns the specificity of 4-AP for Ito. 4-AP does not affect L-type Ca2+ currents (Clark et al. 1993). Apkon & Nerbonne (1991) have shown that the transient component of the depolarization-activated outward current is sensitive to 4-AP, whereas the steady-state current is insensitive to 4-AP, but can be blocked by TEA. Thus, by using 4-AP we should have inhibited only the transient component of the depolarization-activated outward current (Ito). However, Kv1.5, a channel gene which codes for a slowly inactivating current, and which is expressed in the rat ventricle at the mRNA (Dixon & McKinnon, 1994) and at the protein level (Gidh-Jain et al. 1996), is also inhibited by 4-AP (Po et al. 1993) and thus may contribute to the 4-AP-sensitive current. Consistent with an alteration of the delayed rectifier current, we observed in some experiments a reduction in the steady-state current at the end of the voltage pulse induced by 4-AP. On average, however, only a minor component of the total delayed rectifier current was inhibited by 4-AP.

In the present study, stimulation rates of 0.33 Hz or less were used, whereas normal heart rates in rats are much higher. This higher stimulation rate could potentially alter the effects of Ito on AP waveform and Ca2+ influx. Interestingly, Shimoni et al. (1995) found Ito to be more rate sensitive in endocardial than in epicardial myocytes and identified differences in recovery kinetics as the cause: Ito in endocardial myocytes recovered with smaller time constants. As a consequence, at higher stimulation rates APD increased to a larger extent in endocardial than in epicardial myocytes. Thus at higher stimulation rates, the difference in Ca2+ influx between endo- and epicardial myocytes and its modulation by Ito may be even larger than observed in the present study.

Differences between endo- and epicardial myocytes

The gradient in APD and the values we obtained for Ito and L-type Ca2+ current density in endo- and epicardial myocytes are similar to those observed in previous studies under similar conditions (Clark et al. 1993; Shimoni et al. 1995). Clark et al. (1993) did not observe any differences in L-type Ca2+ currents or the steady-state current at the end of the voltage pulse between these two regions. In addition, they found the inwardly rectifier current to be similar in the two regions. Ca2+ influx has been quantified using a similar approach by Bouchard et al. (1995). The values they obtained for Ca2+ influx and the AP-induced peak Ca2+ current were between the values we have observed in endo- and epicardial regions. Since the regional origin of the myocytes they used was not further specified, they might have used myocytes from both regions or from in-between, where Ca2+ influx has intermediate values (data not shown). Terracciano & MacLeod (1997) estimated smaller values for Ca2+ entry than were found in the present study. This discrepancy may be due to a different technical approach: they used conventional microelectrodes without intracellular buffering of Ca2+, and thus a Ca2+-dependent outward current, which was blocked by the addition of Cd2+, may have reduced the recorded inward currents. In addition, they did not specify whether the myocytes were of left or right ventricular or of endo- or epicardial origin.

Effect of inhibition of Ito

Because of its immediate activation by depolarization and its transient nature, Ito plays an important role in the early repolarization of the AP. It influences the height of the plateau potential and the APD, especially in the early phase. Changes in shape and duration of the AP alter the Ca2+ influx: the increase in plateau potential leads to a reduced electrochemical driving force for Ca2+, thereby reducing the AP-induced peak Ca2+ current. A longer AP increases the total time of the Ca2+ current, thus increasing Ca2+ influx. It should be noted that the effects of inhibition of Ito vary among different regions and species. In canine left ventricular epicardial myocytes, the plateau potential increased and the APD decreased, whereas in endocardial myocytes both plateau potential and APD increased after inhibition of Ito (Litovsky & Antzelevitch, 1988). In contrast, in rabbit epicardial myocytes inhibition of Ito increased both APD and plateau potential, while rabbit endocardial myocytes were affected only to a very small extent (Fedida & Giles, 1991). In rat ventricle, inhibition of Ito also led to an increase in the plateau potential and a prolongation of the AP in both epi- and endocardial myocytes, but to a greater extent in epicardial myocytes (Clark et al. 1993).

It has been shown for α1-adrenoceptor activation that an increased Ca2+ influx, facilitated by a longer AP, is responsible for the increase in contractility (Fedida & Bouchard, 1992). In most studies of the effects of chronic alterations on Ito (for review, see Wickenden et al. 1998; Näbauer & Kääb, 1998), its magnitude was found to be reduced in the range of 20-40 %, and this reduction was held to be at least partly responsible for the observed increase in APD. According to the present study, a 30 % reduction in Ito in epicardial myocytes would increase Ca2+ influx by a factor of about 2.8, whereas similar changes in Ito in endocardial myocytes would only have a minor effect. Interestingly, the mechanism of reducing Ito in order to increase Ca2+ influx and thus contractility appears to be limited to epicardial regions of the left ventricle. This may explain the greater increase in unloaded cell shortening in epicardial than endocardial myocytes observed by Clark et al. (1993). An alteration in Ito might therefore allow for a regional regulation of contractility during physiological and pathophysiological adaptations.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to Rudolf Dussel for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Graduiertenkolleg ‘Experimentelle Nieren- und Kreislaufforschung’).

References

- Agus ZS, Dukes ID, Morad M. Divalent cations modulate the transient outward current in rat ventricular myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:C310–318. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.2.C310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TJ, Baker PF. Intracellular Ca indicator Quin-2 inhibits Ca2+ inflow via Na/Ca exchange in squid axon. Nature. 1985;315:755–756. doi: 10.1038/315755a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkon M, Nerbonne JM. Alpha 1-adrenergic agonists selectively suppress voltage-dependent K+ current in rat ventricular myocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1988;85:8756–8760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkon M, Nerbonne JM. Characterization of two distinct depolarization-activated K+ currents in isolated adult rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1991;97:973–1011. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.5.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuckelmann DJ, Näbauer M, Erdmann E. Alterations of K+ currents in isolated human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circulation Research. 1993;73:379–385. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard RA, Clark RB, Giles WR. Effects of action potential duration on excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricular myocytes. Action potential voltage-clamp measurements. Circulation Research. 1995;76:790–801. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.5.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DL, Qu Y, Rasmusson RL, Strauss HC. The calcium-independent transient outward potassium current in isolated ferret right ventricular myocytes. II. Closed state reverse use-dependent block by 4-aminopyridine. Journal of General Physiology. 1993;101:603–626. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.4.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle NA, Slawsky MT. Characterization of 4-aminopyridine block of the transient outward K+ current in adult rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1993;265:1450–1459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RB, Bouchard RA, Salinas SE, Sanchez CJ, Giles WR. Heterogeneity of action potential waveforms and potassium currents in rat ventricle. Cardiovascular Research. 1993;27:1795–1799. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.10.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De-Leon M, Wang Y, Jones L, Perez RE, Wei X, Soong TW, Snutch TP, Yue DT. Essential Ca2+-binding motif for Ca2+-sensitive inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels. Science. 1995;270:1502–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JE, McKinnon D. Quantitative analysis of potassium channel mRNA expression in atrial and ventricular muscle of rats. Circulation Research. 1994;75:252–260. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerr T, Denger R, Trautwein W. Calcium currents in single SA nodal cells of the rabbit heart studied with action potential clamp. Pflügers Archiv. 1989;413:599–603. doi: 10.1007/BF00581808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedida D, Bouchard RA. Mechanisms for the positive inotropic effect of α1-adrenoceptor stimulation in rat cardiac myocytes. Circulation Research. 1992;71:673–688. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.3.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedida D, Giles WR. Regional variations in action potentials and transient outward current in myocytes isolated from rabbit left ventricle. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;442:191–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AP, Nowycky MC, Tsien RW. Kinetic and pharmacological properties distinguishing three types of calcium currents in chick sensory neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;394:149–172. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidh-Jain M, Huang B, Jain P, El-Sherif N. Differential expression of voltage-gated K+ channel genes in left ventricular remodeled myocardium after experimental myocardial infarction. Circulation Research. 1996;79:669–675. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles WR, Imaizumi Y. Comparison of potassium currents in rabbit atrial and ventricular cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;405:123–145. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh Y, Imaizumi Y, Watanabe M, Shibata EF, Clark RB, Giles WR. Inhibition of transient outward K+ current by DHP Ca2+ antagonists and agonists in rabbit cardiac myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:H1737–1742. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.5.H1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Imanaga I. Masking of A-type K+ channel in guinea pig cardiac cells by extracellular Ca2+ American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264:C1434–1438. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.6.C1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg G, Klockner U. Calcium tolerant ventricular myocytes prepared by preincubation in a ‘KB medium’. Pflügers Archiv. 1982;395:6–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00584963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeck CD, Boyden PA. Age-related appearance of outward currents may contribute to developmental differences in ventricular repolarization. Circulation Research. 1992;71:1390–1403. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.6.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson IR, Sanchez CJ, Brown AM. Early outward current in rat single ventricular cells. Circulation Research. 1984;54:157–162. doi: 10.1161/01.res.54.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdon P, Feuvray D. Calcium and potassium currents in ventricular myocytes isolated from diabetic rats. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;470:411–429. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura J, Miyamae S, Noma A. Identification of sodium-calcium exchange current in single ventricular cells of guinea-pig. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;384:199–222. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefevre IA, Coulombe A, Coraboeuf E. The calcium antagonist D600 inhibits calcium-independent transient outward current in isolated rat ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;432:65–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linz KW, Meyer R. Control of L-type calcium current during the action potential of guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;513:425–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.425bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky SH, Antzelevitch C. Transient outward current prominent in canine ventricular epicardium but not endocardium. Circulation Research. 1988;62:116–126. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald TF, Pelzer S, Trautwein W, Pelzer DJ. Regulation and modulation of calcium channels in cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle cells. Physiological Reviews. 1994;74:365–507. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MR, Powell T, Terrar DA, Twist VW. Strontium, nifedipine and 4-aminopyridine modify the time course of the action potential in cells from rat ventricular muscle. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1984;81:551–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1984.tb10108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näbauer M, Beuckelmann DJ, Erdmann E. Characteristics of transient outward current in human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circulation Research. 1993;73:386–394. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näbauer M, Kääb S. Potassium channel downregulation in heart failure. Cardiovascular Research. 1998;37:324–334. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Po S, Roberds S, Snyders DJ, Tamkun MM, Bennett PB. Heteromultimeric assembly of human potassium channels. Molecular basis of a transient outward current. Circulation Research. 1993;72:1326–1336. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.6.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scamps F, Mayoux E, Charlemagne D, Vassort G. Calcium current in single cells isolated from normal and hypertrophied rat heart. Effects of beta-adrenergic stimulation. Circulation Research. 1990;67:199–208. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham JS. Ca2+ release-induced inactivation of Ca2+ current in rat ventricular myocytes: evidence for local Ca2+ signalling. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:285–295. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni Y, Banno H, Clark RB. Hyperthyroidism selectively modified a transient potassium current in rabbit ventricular and atrial myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;457:369–389. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni Y, Severson D, Giles W. Thyroid status and diabetes modulate regional differences in potassium currents in rat ventricle. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;488:673–688. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano CM, MacLeod KT. Measurements of Ca2+ entry and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content during the cardiac cycle in guinea pig and rat ventricular myocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:1319–1326. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierfelder S, Hirche H, Benndorf K. Anoxia decreases the transient K+ outward current in isolated ventricular heart cells of the mouse. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;427:547–549. doi: 10.1007/BF00374273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita F, Bassett AL, Myerburg RJ, Kimura S. Diminished transient outward currents in rat hypertrophied ventricular myocytes. Circulation Research. 1994;75:296–303. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat J, Vereecke J, Carmeliet E. A combined study of sodium current and T-type calcium current in isolated cardiac cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1990;417:142–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00370691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varro A, Nanasi PP, Lathrop DA. Potassium currents in isolated human atrial and ventricular cardiocytes. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1993;149:133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1993.tb09605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettwer E, Amos G, Gath J, Zerkowski HR, Reidemeister JC, Ravens U. Transient outward current in human and rat ventricular myocytes. Cardiovascular Research. 1993;27:1662–1669. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.9.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettwer E, Amos GJ, Posival H, Ravens U. Transient outward current in human ventricular myocytes of subepicardial and subendocardial origin. Circulation Research. 1994;75:473–482. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickenden AD, Kaprielian R, Kassiri Z, Tsoporis JN, Tsushima R, Fishman GI, Backx PH. The role of action potential prolongation and altered intracellular calcium handling in the pathogenesis of heart failure. Cardiovascular Research. 1998;37:312–323. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood EH, Heppner RL, Weidmann S. Inotropic effects of electric currents. I. Positive and negative effects of constant electric currents or current pulses applied during cardiac action potentials. II. Hypotheses: calcium movements, excitation-contraction coupling and inotropic effects. Circulation Research. 1969;24:409–445. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]