Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate the actions of NO donors in ratsuperior mesenteric artery stimulated with noradrenaline by studying their effects on isometric tension, membrane potential (Vm), cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) and accumulation of inositol phosphates.

In unstimulated arteries, SNAP (S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine, 10 μm) hyperpolarised Vm by 3.0 ± 0.5 mV (n = 9). In KCl-stimulated arteries, SNAP relaxed contraction without changing Vm and [Ca2+]cyt.

In noradrenaline-stimulated arteries, SNAP relaxed tension, repolarised Vm and decreased [Ca2+]cyt with the same potency. Responses to SNAP were unaffected by the following K+ channel blockers: glibenclamide, 4-aminopyridine, apamin and charybdotoxin, and by increasing the KCl concentration to 25 mM.

In SNAP-pretreated arteries, the production of inositol phosphates and the contraction stimulated by noradrenaline were inhibited similarly.

The guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ abolished the increase in cyclic GMP content evoked by SNAP and inhibited the effects of SNAP on contraction, Vm and accumulation of inositol phosphates in noradrenaline-stimulated artery.

These results indicate that, in rat superior mesenteric arteries activated by noradrenaline, inhibition of production of inositol phosphates is responsible for the effects of the NO donor SNAP on membrane potential, [Ca2+]cyt and contraction through a cyclic GMP-dependent mechanism.

Vascular endothelium plays an important role in the regulation of tone through the release of contraction and relaxation factors, among which nitric oxide (NO) is one of the most important. Relaxation in response to NO is observed in many arteries. While the activation of the guanylate cyclase activity by NO is well recognised, the mechanism of the vasorelaxation is still debated. Several hypotheses have been proposed: decrease in the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile proteins (Salomone et al. 1995; Tran et al. 1998), activation of the Ca2+-ATPase (Cornwell et al. 1991), inhibition of intracellular Ca2+ release (Yuan et al. 1997) and inhibition of Ca2+ channels (Tewari & Simard, 1997).

Recently, K+ channels have emerged as possible mediators of NO-evoked vasorelaxation. Potassium channels are involved in the regulation of resting membrane potential and consequently of resting tone, and in the control of agonist-evoked depolarisation, in a way that depends on the subtype of the channel and on the artery (reviewed in Nelson & Quayle, 1995; Brayden, 1996). NO has been reported to activate Ca2+-dependent K+ channel (KCa) or voltage-dependent K+ channel (Kv) current, either directly (Bolotina et al. 1994; Yuan et al. 1996; Weidelt et al. 1997; Mistry & Garland, 1998) or through the activation of guanylate cyclase and the production of cyclic GMP (Robertson et al. 1993; Carrier et al. 1997). However, the physiological relevance of this effect is not clear. Indeed, NO hyperpolarises resting membrane potential in some arteries (Garland & McPherson, 1992; Krippeit-Drews et al. 1992; Plane et al. 1994; Murphy & Brayden, 1995; Archer et al. 1996; Weidelt et al. 1997), but not in others (Chen et al. 1988; Rand & Garland, 1992; Plane & Garland, 1993). Similarly, the vasorelaxation evoked by NO in precontracted arteries is associated with a change in membrane potential in rabbit carotid artery (Cohen et al. 1997; Plane et al. 1998) but not in rabbit basilar artery (Plane & Garland, 1993). A role for K+ channels in the vasorelaxation is suggested by the inhibition of the relaxation by K+ channel blockers (Archer et al. 1994; Plane et al. 1996; Carrier et al. 1997; Plane et al. 1998). Again, K+ channel blockers do not affect, or only slightly depress, the vasorelaxation in other arteries (Armstead, 1997; Vanheel & Van de Voorde, 1997).

In view of the multiplicity of the actions of NO and of the variability that is evident among vascular beds, it is important to investigate simultaneously the effects of NO on the different parameters involved in the control of smooth muscle tone. Among the reports concerning the mechanisms of NO-evoked relaxation, few studies have followed this kind of approach. The aim of the present work was thus to investigate the mechanism(s) of the vasorelaxation to NO in the superior mesenteric artery of WKY rats contracted by noradrenaline, by simultaneously recording contractile tone and membrane potential, by measuring the cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) and the production of inositol phosphates (IPs). In order to avoid the interference of both the permanent release of NO from the endothelium and of other endothelium-derived factors released by endothelium activation, endogenous production of NO was blocked with Nω-nitro-L-arginine and the NO donors SNAP (S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine) and SIN-1 (3-morpholino-sydnonimine) were used. The results suggest that, in the noradrenaline-stimulated superior mesenteric artery of the rat, K+ channel activation does not play a major role in the vasorelaxation evoked by the NO donors, SNAP and SIN-1. Interaction with an early step in the excitation-contraction coupling process could account for most of their effects on membrane potential, [Ca2+]cyt and tension.

METHODS

Normotensive Wistar-Kyoto (WKY, 14 weeks old, about 300 g) male rats (Iffa Credo, L'Arbresle, France) were used. Animals were housed in standard conditions and were given standard rodent chow and water ad libitum. Rats were anaesthetised with diethyl ether and killed by decapitation using a small animal guillotine. The superior mesenteric artery was rapidly removed, immersed in physiological solution of composition (mM): NaCl, 122; KCl, 5.9; NaHCO3, 15; glucose, 10; MgCl2, 1.25; and CaCl2, 1.25; supplemented with indomethacin (10 μm) and gassed with a mixture of 95 % O2-5 % CO2, and carefully cleaned of all fat and connective tissue. All experiments were carried out in accordance with national guidelines.

Simultaneous measurement of contractile tension and membrane potential

A segment of the superior mesenteric artery, ±2 mm in length, was inverted and mounted in a myograph. Briefly, two 40 μm wires were threaded through the lumen of the vessel segment. One wire was attached to a stationary support driven by a micrometre, while the other was attached to an isometric force transducer (UC 2, Gould). The bath of the myograph was continuously perfused with physiological solution, gassed and maintained at 37°C. Vessels were maintained under zero force for 60 min. A passive diameter- tension curve was constructed as described by Mulvany & Halpern (1977). The vessel was set at a tension equivalent to that generated at 0.9 times the diameter of the vessel under a transmural pressure of 100 mmHg.

Measurement of the smooth muscle membrane potential was made with a glass microelectrode (type GC 120F-15, Clark Electromedical Instruments, Reading, UK) filled with 1.5 M KCl and advanced through the luminal surface of the arterial segment with a micromanipulator. The input resistance of the microelectrodes varied between 50 and 80 MΩ. Potential differences were measured with reference (reference electrode type E208, Clark Electromedical Instruments) to the earthed bath by means of a Dagan amplifier (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Electrical responses were monitored on an oscilloscope. Membrane potential and tension were simultaneously recorded with a pen recorder. Criteria for a successful impalement were an abrupt drop in voltage on entry of the microelectrode into the cell, stable membrane potential for at least 2 min, and a sharp return to zero on withdrawal of the electrode.

After being mounted in the organ chamber, the rings were maintained in physiological solution (see above) containing Nω-nitro-L-arginine (L-NOARG, 100 μm) for 30 min before the initiation of the experiment. L-NOARG was used in order to avoid the interference with endogenously synthesised NO. The agonists and antagonists tested were applied in the perfusion solution. When high-KCl solutions were used, the NaCl concentration was reduced on a molar basis. The noradrenaline concentration was adapted to produce a contraction equivalent to 75 % of the maximum contraction evoked by noradrenaline and of a similar amplitude to that produced by a 40 mM KCl solution. Vasorelaxation to NO donors SNAP and SIN-1 was evoked by application of the drug during a sustained contraction.

Measurement of contractile tension and cytosolic calcium concentration

Mesenteric artery rings were incubated for 3.5 h at room temperature in physiological solution containing 5 μm fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (fura-2 AM) and 0.05 % Cremophor EL. After the loading period, the rings were washed in physiological solution at 37°C for 30 min. The rings were mounted between two hooks under a tension of 8 mN in a 3 ml cuvette filled with physiological solution (composition as above) at 37°C gassed with 95 % O2- 5 % CO2. All solutions contained L-NOARG (100 μm) and indomethacin (10 μm). The cuvette was part of a fluorimeter (CAF, JASCO, Tokyo) which allowed estimation of the calcium signal. The muscle tone was measured by an isometric force transducer. The Ca2+ signal was measured as previously reported (Salomone et al. 1995). The fluorescence signals at 340 and 380 nm, F340 and F380, respectively, were measured simultaneously with the contractile tension and recorded on a computer, by using the data acquisition hardware MacLab and data recording software Chart (AD Instruments Pty Ltd, Castle Hill, Australia). After being mounted in the cuvette, the artery segment was further incubated for 30 min in physiological solution. Washing the artery at 37°C for 2 × 30 min allowed the leakage of fura-2 from the endothelial cells (Kuroiwa et al. 1993). Absence of Ca2+ signals from the endothelial cells was ensured by the absence of an increase in the Ca2+ signal when acetylcholine was added to the medium (Usachev et al. 1995). The artery was thereafter stimulated with 40 mM KCl solution. After washing and a further 15 min recuperation (during which time antagonists were added when required), the preparation was stimulated by either noradrenaline (0.5-1 μm), AlF4− or KCl (40 mM). Concentrations of the stimulatory agents were adjusted in order to produce a contraction of an amplitude similar to that developed by KCl. SNAP was added into the cuvette at the plateau of the contraction. At the end of the experiment, the fura-2 Ca2+ signal was calibrated. The maximal ratio (Rmax) was measured in calcium saturating medium by adding ionomycin (10 μm) in high-KCl solution (KCl 127 mM), while the minimal ratio (Rmin) was obtained in calcium-free medium in the presence of EGTA (10 mM). The autofluorescence was measured at 340 and 380 nm by quenching the fura-2 fluorescence with MnCl2 (5 mM). The cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) was calculated as described previously (Salomone et al. 1995).

Determination of cyclic GMP content

Cyclic GMP content was measured as described previously (Salomone et al. 1996). Briefly, mesenteric artery segments (3 mm) were incubated in physiological solution in the presence of isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX, 100 μm), L-NOARG (100 μm), indomethacin (10 μm), noradrenaline (0.5 μm) and with or without ODQ (1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one, 10 μm) for 30 min. SNAP was added to the incubation medium for the last 5 min. At the end of the incubation period, the tissues were immersed in liquid nitrogen, homogenised in trichloroacetic acid (6 %) and centrifuged at 1000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was extracted twice with 5 ml of water-saturated diethyl ether and cyclic GMP was assayed in the aqueous solution by radioimmunoassay (acetylation protocol). The amount of protein in the centrifugation pellet was determined by the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

Determination of inositol phosphates (IPs)

The artery segments were incubated in modified physiological solution (mM): NaCl, 118; KCl, 4.7; CaCl2, 1.25; MgCl2, 1.25; KH2PO4, 1.2; EDTA, 0.5; NaHCO3, 25; Hepes, 3.3; glucose, 10; Tris-HCl, 20 (pH 7.4) supplemented with indomethacin (10 μm) and L-NOARG (100 μm) at 37°C for 1 h. Subsequently, artery segments were incubated for 4 h at 37°C in fresh buffer containing 20–25 μCi ml−1 of [3H]myo-inositol. At the end of the incubation, [3H]inositol-labelled artery segments were washed in buffer for 10 min and then transferred to physiological solution containing 10 mM LiCl, plus noradrenaline (0.5 μm) and SNAP as required. Incubation was carried out for 30 min and stopped by rapid freezing of the tissue samples, transfer of the tissue to 1 ml assay tubes, and addition of 0.3 ml of ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (1 M). Tubes were vortexed and 0.3 ml aliquots were transferred to clean assay tubes and extracted twice with 1 ml chloroform:methanol (2:1). After the final wash, pH was adjusted to 7–8. Aliquots (0.8 ml) were loaded on Dowex AG 1 × 8 ion-exchange columns. The columns were washed with 10 ml water, 20 ml of 60 mM ammonium formate and 5 mM sodium tetraborate and 2 ml of 1 M ammonium formate and 0.1 M formic acid. Aliquots (0.5 ml) of the last eluent were counted for radioactivity in 10 ml of scintillant (PicoFluor, Packard Bioscience Company). Data were normalised to the protein content of each sample, measured by the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

Measurement of noradrenaline-evoked contraction in SNAP-pretreated artery

In order to compare the effects of SNAP on the accumulation of IPs and on the contraction evoked by noradrenaline, contraction was recorded in artery rings pretreated with SNAP. Artery rings were mounted in a myograph as described above. After equilibration, a first noradrenaline contraction was evoked. After washout and 60 min recuperation, SNAP was added into the bath (10 nM to 10 μm) 1 min before a second challenge with noradrenaline (0.5 μm, 30 min). Contractile responses were estimated by measuring the area under the curve (data recording software Chart v3.4, AD Instruments). The response obtained in the presence of SNAP was compared with the response obtained in the same artery before the addition of SNAP.

Drugs

Fura-2 acetoxymethylester (fura-2 AM) and ODQ were from Calbiochem (EuroBiochem, Bierges, Belgium). Charybdotoxin was from Latoxan (Rosans, France). Ionomycin was from Boehringer Mannheim (Brussels, Belgium). The cyclic GMP radioimmunoassay kit was from Amersham (Little Chalfont, UK). [3H]myo-Inositol was from NEN Du Pont Research Products (Brussels, Belgium). SIN-1 was a gift from Therabel and was dissolved in Na2HPO4/KH2PO4 buffer (pH 6.88). Cremophor EL, SNAP and all other compounds were obtained from Sigma. SNAP was dissolved in ethanol:water (1:1) as a 10 mM stock solution. Further dilutions were prepared in physiological solution immediately before use. 4-Aminopyridine solutions were adjusted to pH 7.4 with HCl. AlF4− was produced by the combination of 5 mM sodium fluoride (NaF) and 30 μm aluminium chloride (AlCl3). Glibenclamide and ODQ were dissolved in DMSO. Stock solution of indomethacin was prepared in 2 % Na2CO3.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ±s.e.m. EC50 values were calculated by non-linear curve fitting of the experimental data of the concentration-effect curves to the equation:

|

where Emax is the maximum amplitude of the effect produced by the agonist, [A] is the concentration of agonist and nH is the Hill slope (Multifit, Day Computing, Cambridge, UK; KaleidaGraph, Synergy Software, Reading, PA, USA). pD2, the negative log of the EC50 value, was used for the statistical analysis. pD2 values were obtained directly from individual EC50 values. Comparisons were made by Student's t test or by one-way ANOVA test, when more than two groups were compared. Differences of P values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Effects of NO donors on membrane potential, Ca2+ signal and tone in resting artery and in KCl- depolarised artery

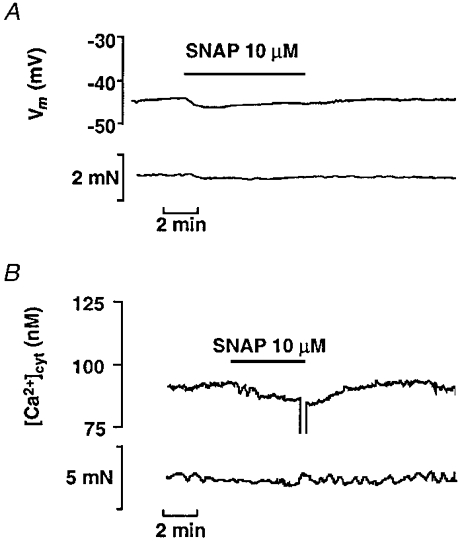

The mean resting membrane potential of rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells recorded in arteries incubated in the presence of L-NOARG (100 μm) and indomethacin (10 μm) was −44.4 ± 0.3 mV (n = 44). In unstimulated arteries, SNAP (10 μm) hyperpolarised the membrane by 3.0 ± 0.5 mV (n = 9) and produced a small drop in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) and tension (Fig. 1). The same effect was observed with SIN-1 (10 μm), which hyperpolarised the cell membrane by 1.7 ± 0.2 mV (n = 4).

Figure 1. Effects of SNAP in unstimulated mesenteric artery.

A, representative experimental traces showing simultaneous records of smooth muscle membrane potential (Vm, upper trace) and tension (lower trace) in an unstimulated artery segment. SNAP was applied as indicated. B, representative experimental traces showing simultaneous records of cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt, upper trace) and tension (lower trace) in an unstimulated artery segment loaded with fura-2.

Increasing the KCl concentration in the medium to 40 mM contracted the arteries by 9.2 ± 1.9 mN (n = 11) and depolarised the cell membrane to −22 ± 1.3 mV (n = 6). In fura-2-loaded arteries, 40 mM KCl increased [Ca2+]cyt from 116 ± 11 to 250 ± 34 nM (n = 5). The higher concentration of SNAP (10 μm) relaxed the tension by 85 ± 6.7 % (n = 6) but did not significantly change the membrane potential (-23.3 ± 1.2 mV, n = 6, in the presence of SNAP). Similarly, in fura-2-loaded arteries, SNAP (10 μm) relaxed tension by 87 ± 5 % (n = 6) but did not significantly affect the [Ca2+]cyt, which was equal to 235 ± 35 nM (n = 4) after the addition of SNAP (Fig. 2). The pD2 value for the vasorelaxation to SNAP was 6.49 ± 0.15 (n = 4). Similar results were obtained with SIN-1, which at a concentration of 10 μm changed the membrane potential of KCl-depolarised arteries by only 2 ± 0.5 mV while it relaxed the contraction by 92 ± 3 % (n = 3). The effects of SNAP in high-KCl solution were not affected by the α-adrenergic antagonist phentolamine (10 μm).

Figure 2. Effects of SNAP on membrane potential, cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and contractile tension in KCl-stimulated mesenteric artery.

A, left panel: representative experimental traces of simultaneous records of membrane potential (Vm, upper trace) and tension (lower trace) showing the lack of repolarisation and the marked relaxation evoked by SNAP (10 μm) in a mesenteric artery segment depolarised and contracted by 40 mM KCl. Right panel: mean values +s.e.m. from 6 arteries. Responses to KCl were measured immediately before the addition of SNAP. Responses to SNAP were measured at their maximum. * P < 0.05 versus KCl. B, left panel: representative traces showing simultaneous records of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt, upper trace) and contractile tension (lower trace), in a mesenteric artery segment stimulated with KCl (40 mM). SNAP (10 μm) was applied as indicated. Right panel: mean values +s.e.m. from 5 arteries. Responses to KCl were measured immediately before the addition of SNAP. Responses to SNAP were measured at their maximum. * P < 0.05 versus KCl.

Effects of SNAP on membrane potential, Ca2+ signal and tone in noradrenaline-contracted artery

Noradrenaline (0.5 μm) depolarised the cell membrane to −32.8 ± 1.1 mV and simultaneously produced a contraction of 9.5 ± 0.7 mN (n = 9). In most of the cells, rhythmic oscillations of the membrane potential of 5–10 mV of amplitude were superimposed on the tonic depolarisation. In such cells, the membrane potential was measured as the mean between maximum and minimum values. Rhythmic activity was less pronounced in the contractile tension. In the fura-2-loaded artery, contraction of an amplitude similar to that produced by 40 mM KCl was obtained with a mean concentration of 0.8 ± 0.02 μm noradrenaline, which increased [Ca2+]cyt from 120 ± 6.3 to 210 ± 24 nM and simultaneously produced a contraction of 10.1 ± 2.4 mN (n = 10). The addition of SNAP (10 nM to 10 μm) on the plateau of the contraction evoked by noradrenaline produced a dose-dependent vasorelaxation (maximum relaxation: 100 ± 0.7 %, n = 5) and simultaneously abolished the noradrenaline-evoked depolarisation (in the presence of 10 μm SNAP membrane potential was −43.8 ± 1.2 mV, a value not significantly different from the resting membrane potential recorded before the addition of noradrenaline, n = 5) (Fig. 3). The concentration-effect curves for the effect of SNAP on the noradrenaline-evoked change in membrane potential and in contractile tension ran parallel, pD2 values were 6.61 ± 0.20 and 6.82 ± 0.17 for the change in membrane potential and for the relaxation, respectively (n = 6) (Fig. 3). SIN-1 produced the same effects as SNAP: relaxation of the contraction to noradrenaline was complete in the presence of SIN-1 (10 μm), which also repolarised the membrane potential to its resting level (n = 3 arteries; not shown).

Figure 3. Effects of SNAP on membrane potential, cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and contractile tension in noradrenaline-stimulated mesenteric artery.

A, representative original traces of simultaneous records of membrane potential (Vm, upper trace) and contractile tension (lower trace) showing the repolarisation and the relaxation induced by SNAP (10 μm) in an artery segment depolarised and contracted by noradrenaline (NA, 0.5 μm). B, experimental traces showing simultaneous records of cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt, upper trace) and contractile tension (lower trace) in a fura-2-loaded mesenteric artery segment stimulated with noradrenaline (NA, 1 μm) C, dose-effect curves for the effects of SNAP on membrane potential and tension. The change in membrane potential (expressed in mV) is compared with the relaxation (expressed as a percentage of the contraction to noradrenaline) evoked by increasing concentrations of SNAP applied on the plateau of the contraction in untreated arteries (□, change in membrane potential, ΔVm; ○, relaxation) and in arteries preincubated in the presence of the guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ (10 μm) (▪, change in membrane potential, ΔVm; •, relaxation). The dashed line represents the change in potential reversing the depolarisation evoked by noradrenaline. Data are mean values ±s.e.m. from 7 experiments. D, dose-effect curves for the effects of SNAP on cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (▵) and tension (○). Increasing concentrations of SNAP were cumulatively applied on arteries stimulated with noradrenaline (0.5-1 μm). The change in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and the relaxation are expressed as a percentage of the response to noradrenaline measured before the addition of SNAP. Data are mean values ±s.e.m. from 6 experiments.

In fura-2-loaded arteries stimulated by noradrenaline, SNAP-evoked relaxation was associated with a decrease of [Ca2+]cyt to its basal value (Fig. 3). SNAP had the same potency on the Ca2+ signal and on the contraction, pD2 values being 7.09 ± 0.17 and 7.23 ± 0.23, respectively (n = 6). There was a small difference between the vasorelaxant potency of SNAP measured in fura-2-loaded arteries compared with unloaded arteries, the former being slightly more sensitive to the NO donor than the latter, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Involvement of cyclic GMP in the responses to SNAP in noradrenaline-stimulated artery was tested by blocking the guanylate cyclase with the specific blocker ODQ (10 μm). SNAP (10 μm) increased the concentration of cyclic GMP in the artery from 339 ± 34 fmol (mg protein)−1 (n = 6) to 684 ± 42 fmol (mg protein)−1 (n = 6, P < 0.01 versus basal level). Preincubation of the artery with ODQ (10 μm) prevented the increase in cyclic GMP produced by SNAP (391 ± 13 fmol (mg protein)−1 in the presence of ODQ and SNAP, n = 6; P < 0.01 versus SNAP; not significantly different from basal level). In noradrenaline-stimulated artery, ODQ markedly and significantly inhibited the relaxation and the repolarisation to SNAP (Fig. 3). Marked fluorescence of the ODQ molecule at 340 nm prevented its use in [Ca2+]cyt measurement.

Influence of K+ channel blockers on the responses to NO donors in noradrenaline-contracted artery

The lack of effect of SNAP on membrane potential and [Ca2+]cyt in high-KCl solution suggested that the responses observed in noradrenaline-stimulated arteries could be mediated by an interaction with K+ channels. Several selective K+ channel blockers were used to investigate which channel could contribute to the change in membrane potential evoked by SNAP: glibenclamide (0.1 μm) as a blocker of ATP-dependent K+ channels (KATP), 4-aminopyridine (0.5 mM) as a blocker of voltage-dependent K+ channels (Kv), and the association of charybdotoxin (0.1 μm) + apamin (0.1 μm) to block Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa) (Nelson & Quayle, 1995). Their effects are summarised in Fig. 4. All the K+ channel blockers depolarised and contracted resting artery: the most effective was the combination of charybdotoxin plus apamin, followed by 4-aminopyridine and glibenclamide. The effects of 4-aminopyridine and glibenclamide were not statistically significant. In fura-2-loaded arteries, glibenclamide and 4-aminopyridine did not significantly change resting [Ca2+]cyt while the combination of charybdotoxin plus apamin increased basal [Ca2+]cyt by 41 ± 14 nM and tension by 1.7 ± 0.9 mN (n = 6). Noradrenaline (0.5 μm) contracted the artery by 10.1 ± 0.9 mN (n = 11), 11.5 ± 1.3 mN (n = 7) and 8.2 ± 1.8 mN (n = 4) in the presence of charybdotoxin plus apamin, 4-aminopyridine and glibenclamide, respectively. Simultaneously, membrane potential was depolarised by a mean value of 10–15 mV, most of the cells exhibiting rhythmic oscillations similar to those noted in the absence of blocker (Fig. 4). None of the K+ channel blockers significantly modified the effects of SNAP on contraction and membrane potential: there was no change in the maximum effect of SNAP or in its EC50 value (Fig. 4, Table 1). Only the combination of charybdotoxin and apamin slightly shifted to the right the curve for the effect of SNAP on [Ca2+]cyt without affecting the relaxation (Table 1).

Figure 4. Effects of K+ channel blockers on the repolarisation and the relaxation in response to SNAP (10 μm) in arteries contracted with noradrenaline.

A-D, left panels: original records showing the changes in membrane potential (Vm, upper trace) and in tension (lower trace) induced by SNAP in the presence of charybdotoxin (Ctx, 0.1 μm) and apamin (Apa, 0.1 μm; A), 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 0.5 mm; B), glibenclamide (Gli, 0.1 μm; C), and a cocktail of charybdotoxin (0.1 μm) + apamin (0.1 μm) + 4-aminopyridine (5 mM) + glibenclamine (10 μm; D), in artery segments stimulated by noradrenaline (NA, 0.5 μm). Right panels: bar graphs showing the mean values +s.e.m. of the change in membrane potential (Vm) evoked by the blocker(s) (□), noradrenaline in the presence of the blocker(s) before the addition of SNAP (▪) and after the addition of SNAP (1–10 μm) ( ,

, ). The base of the columns corresponds to the level of the resting membrane potential. Data are means +s.e.m. from 4–11 recordings.

). The base of the columns corresponds to the level of the resting membrane potential. Data are means +s.e.m. from 4–11 recordings.

Table 1. Effect of K+ channel blockers on the pD2 values (–log ED50) of SNAP for the inhibition of the increase in [Ca2+]cyt and of the contractile tension induced by noradrenaline.

| n | pD2 values for [Ca2+]cyt | pD2 values for contractile tension | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 6 | 7.09 ± 0.17 | 7.23 ± 0.23 |

| Charybdotoxin (0.1 μm) + apamin (0.1 μm) | 4 | 6.15 ± 0.13* | 6.72 ± 0.26 |

| 4-Aminopyridine (0.5 μm) | 4 | 6.67 ± 0.34 | 6.96 ± 0.28 |

| Glibenclamide (0.1 μm) | 4 | 6.68 ± 0.09 | 7.03 ± 0.24 |

| Cocktail of blockers | 4 | 6.04 ± 0.31* | 6.60 ± 0.28 |

P < 0.05 versus control (ANOVA). ‘Cocktail of blockers’ contained charybdotoxin (0.1 μm), apamin (0.1 μm), 4aminopyridine (5 μm) and glibenclamide (10 μm). Changes in [Ca2+]cyt and in contractile tension were measured simultaneously in fura-2loaded arteries. Increasing concentrations of SNAP were added during a sustained contraction evoked by noradrenaline. pD2 values were calculated by nonlinear regression of individual experimental data. pD2 values for the change in [Ca2+]cyt and in contractile tension in each condition were not significantly different (paired t test). Data are mean values ± S.E.M. from n determinations.

To test the possibility that different types of K+ channels could be stimulated by SNAP simultaneously, a combination of all the blockers at maximal concentration (charybdotoxin, 0.1 μm; apamin, 0.1 μm; glibenclamide, 10 μm; 4-aminopyridine, 5 mM) was also used. The cocktail of all the blockers depolarised the membrane to −29.7 ± 3.5 mV and contracted the artery by 4.5 ± 2.5 mN (n = 3). Figure 4D shows that in noradrenaline-depolarised arteries, the combination of all the blockers did not prevent the change in membrane potential evoked by SNAP, which repolarised the membrane to −30.3 ± 0.7 mV (n = 3), a value not different from the potential recorded before the addition of noradrenaline. As observed in the presence of charybdotoxin plus apamin, the concentration-effect curve of SNAP for the decrease in [Ca2+]cyt was shifted slightly to the right, but relaxation was unaffected (Table 1). Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments when SIN-1 was used as NO donor: the relaxation of the contraction to noradrenaline and the repolarisation of the membrane potential evoked by SIN-1 were not affected by the cocktail of blockers (not shown).

Since the effects of SNAP and SIN-1 on membrane potential could still be related to the activation of a K+ conductance resistant to the blockers used, the driving force for K+ was reduced by increasing the concentration of KCl in the bathing solution from 5.9 to 25 mM (Fig. 5). KCl (25 mM) produced a depolarisation of 15.4 ± 1 mV (n = 5), increased the [Ca2+]cyt by 71 ± 19 nM (n = 3) and contracted the artery ring by 6.8 ± 1.3 mN (n = 9). In the presence of KCl (25 mM), noradrenaline further depolarised the cell membrane by 7.2 ± 1.3 mV (n = 5), increased [Ca2+]cyt by 52 ± 19 nM (n = 3) and contracted the artery ring by 12.7 ± 2.3 mN (n = 9). SNAP (10 μm) repolarised the membrane potential by 7.5 ± 0.9 mV (n = 4) and decreased [Ca2+]cyt by 43 ± 15 nM (n = 3) while the tension was relaxed by 86 ± 3 % of the total contraction (n = 9). In the presence of SNAP, phentolamine (10 μm) did not change membrane potential and [Ca2+]cyt further, suggesting that SNAP reversed the depolarisation, and the increase in [Ca2+]cyt evoked by noradrenaline, without affecting the responses to KCl, in agreement with results obtained in KCl-activated arteries.

Figure 5. Effects of 25 mM KCl on the change in membrane potential and in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and on the relaxation evoked by SNAP in noradrenaline-stimulated mesenteric artery.

A, left panel: original records showing the changes in membrane potential (Vm, upper trace) and in tension (lower trace) induced by SNAP in a mesenteric artery ring stimulated with noradrenaline in the presence of 25 mm KCl. Right panel: mean values +s.e.m. from 4 recordings of the membrane potential (Vm). The base of the columns corresponds to the level of the resting membrane potential. B, left panel: original traces showing simultaneous records of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt, upper trace) and contractile tension (lower trace), in a mesenteric artery segment stimulated with noradrenaline in the presence of 25 mM KCl. SNAP (10 μm) and phentolamine (Phent, 10 μm) were applied as indicated. Right panel: mean values +s.e.m. from 3 recordings of the change in [Ca2+]cyt.

Effect of SNAP on the production of inositol phosphates stimulated by noradrenaline

The α-adrenoceptors in vascular smooth muscle cells are known to be coupled to production of inositol phosphates (IPs) (Hashimoto et al. 1986). In the rat superior mesenteric artery, the production of IPs could be readily stimulated by noradrenaline. The mean stimulation of total IPs production by noradrenaline (0.5 μm) was 185 ± 20 % (n = 15) above the basal level. As shown in Fig. 6, the stimulation of IPs production by noradrenaline was inhibited in the presence of SNAP (0.1-10 μm) but the basal level of IPs production was unaffected. The highest concentration of SNAP (10 μm) produced an inhibition of 81 ± 5 % of IPs accumulation, and the pD2 value was equal to 5.84 ± 0.21 (n = 3 individual experiments performed in triplicate). The effect of SNAP (10 μm) on the stimulation of IPs production by noradrenaline was abolished by the guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ (10 μm) (Fig. 6) but it was not affected by the increase of the KCl concentration in the medium to 40 mM (in 40 mM KCl solution, SNAP (10 μm) inhibited the noradrenaline-evoked production of IPs by 75 ± 6 %, n = 3).

Figure 6. Effect of SNAP on inositol phosphates accumulation in noradrenaline-stimulated preparation.

A,[3H]myo-inositol-loaded arteries were pretreated with SNAP and/or ODQ (10 μm) for 1 min and further incubated in the presence of noradrenaline for 30 min. Data are from a typical experiment, performed in triplicate. * P < 0.05 versus NA in the absence of SNAP. B, comparison of the inhibition by SNAP of inositol phosphates accumulation and of contraction evoked by noradrenaline. Arteries were pretreated with SNAP for 1 min before the addition of noradrenaline. Contraction was measured by the area under the curve. Data are means ±s.e.m. from 6 determinations.

In order to compare the effect of SNAP on accumulation of IPs with its vasorelaxant effect, the inhibition of the contraction was measured in experimental conditions similar to those used for the measurement of IPs. Thus, contraction was evoked by noradrenaline in arteries pretreated with SNAP and the response to noradrenaline was estimated by measuring the area under the curve, during a time interval of 30 min. In these conditions, SNAP was less potent than when it was added on the plateau of the response to noradrenaline. The inhibition of the contraction by the NO donor was then close to, although not superimposed on, the inhibition of IPs accumulation. The pD2 value of SNAP in pretreated arteries was equal to 6.32 ± 0.03 (n = 4).

Effects of SNAP on membrane potential, Ca2+ signal and tone in artery stimulated by AlF4−

AlF4− produces a contraction of vascular smooth muscle by direct activation of G proteins (Boonen & De Mey, 1990). Incubation of the artery in the presence of NaF (5 mM) and AlCl3 (30 μm) produced a slow depolarisation (mean steady-state depolarisation: 13.5 ± 1.3 mV, n = 4). Contraction developed with a latency of about 2 min and reached a plateau value of 14.1 ± 3.3 mN (n = 4). In fura-2-loaded arteries, AlF4− produced a slow increase in [Ca2+]cyt which was observed before the increase in contraction (Fig. 7). SNAP (10 μm) rapidly relaxed the contraction, repolarised the membrane and reversed the increase in [Ca2+]cyt. Mean inhibition values were 91 ± 2 % (n = 8), 80 ± 4 % (n = 4) and 77 ± 5 % (n = 4), for the contraction, the membrane potential and the Ca2+ signal, respectively.

Figure 7. Effects of SNAP on membrane potential, cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and contractile tension in mesenteric artery segments stimulated with AlF4−.

A, left panel: experimental traces of simultaneous records of membrane potential (Vm, upper trace) and tension (lower trace) showing the repolarisation and the relaxation induced by SNAP (10 μm) in an artery segment depolarised and contracted with AlF4−. Right panel: mean values +s.e.m. from 4 recordings. Responses to AlF4− were measured immediately before the addition of SNAP. Responses to SNAP were measured at their maximum. ** P < 0.01. B, left panel: experimental traces showing simultaneous records of cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt, upper trace) and contractile tension (lower trace) in a fura-2-loaded artery segment stimulated with AlF4−. Right panel: mean values +s.e.m. from 4 recordings. Responses to AlF4− were measured immediately before the addition of SNAP. Responses to SNAP were measured at their maximum. ** P < 0.01.

Effects of cromakalim in noradrenaline-stimulated artery

The effects of SNAP on contraction and membrane potential in noradrenaline-stimulated arteries were compared with those of the K+ channel opener cromakalim. In unstimulated arteries, cromakalim (10 μm) produced a hyperpolarisation of −26 ± 1.7 mV (n = 3). In noradrenaline-stimulated arteries, cromakalim produced a complete relaxation, which was associated with a change in membrane potential (Fig. 8). Higher concentrations of cromakalim (1–10 μm) shifted the membrane potential towards hyperpolarised values. At a concentration of 1 μm, cromakalim relaxed the contraction by 93 ± 1.7 % and simultaneously hyperpolarised the membrane potential to −55 ± 1.5 mV (n = 6), a value which is about 10 mV more negative than the resting membrane potential.

Figure 8. Effects of cromakalim on the depolarisation and the contraction evoked by noradrenaline.

Increasing concentrations of cromakalim were cumulatively applied on arteries stimulated with noradrenaline (0.5 μm). Membrane potential (□) and contractile tension (○) were recorded simultaneously. Changes in membrane potential are expressed as the difference between the membrane potential value recorded in the presence of cromakalim and its value recorded in the presence of noradrenaline before the addition of cromakalim. The relaxation is expressed as a percentage of the contraction evoked by noradrenaline. The dashed line represents the change in potential reversing completely the depolarisation evoked by noradrenaline. Data are mean values ±s.e.m. from 6 experiments.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of NO donors on the different steps of the excitation pathway activated by noradrenaline in the superior mesenteric artery of the rat. We have used the NO donor SNAP, which releases nitric oxide extracellularly, probably after a metabolic activation step at the external vascular smooth muscle cell membrane (Butler & Rhodes, 1997). Major effects were confirmed with another NO donor, SIN-1 (Feelisch et al. 1989).

A common characteristic of the effects of SNAP on IPs accumulation, membrane potential, and contraction in noradrenaline-stimulated artery was their sensitivity to the guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ. This suggests that the first step in the signal transduction pathway of SNAP-derived NO is the activation of the guanylate cyclase in the smooth muscle cells and the production of cyclic GMP. Two main effects then result from the increase in cyclic GMP concentration: the decrease in sensitivity to Ca2+ of the contractile machinery, which is responsible for the relaxation of KCl-activated arteries, and the uncoupling of the excitation-contraction process activated by noradrenaline, which prevents the development of the agonist-evoked responses.

Before discussing in detail the actions of NO, it is worthwhile briefly reviewing the mechanisms involved in the contraction evoked by noradrenaline, even if their investigation did not constitute the main objective of the present study. Noradrenaline-evoked contraction was associated with IPs accumulation, membrane depolarisation and increase in [Ca2+]cyt. In the rat mesenteric artery, noradrenaline binds to α1D- and α1L-adrenergic receptors (Youssif et al. 1998). α-Adrenoceptors are mainly coupled to Gq proteins (Exton, 1994) which activate phospholipase Cβ1 (PLCβ1) and PLCβ3 (Wu et al. 1992) to produce inositol trisphosphate (IP3). Mechanisms underlying the depolarisation evoked by noradrenaline involve Ca2+-dependent activation of Cl− channels and/or other membrane conductances (Amédée et al. 1990; Lamb & Barna, 1998) triggered by the release of intracellular Ca2+ evoked by IP3 (Loirand et al. 1990). Depolarisation causes the opening of voltage-operated Ca2+ channels allowing Ca2+ influx (Morel & Godfraind, 1991). A direct effect of noradrenaline on voltage-operated Ca2+ channels has also been proposed (Nelson et al. 1988). Noradrenaline also causes an increase in the sensitivity to Ca2+ of the contractile filaments, which is, at least partly, mediated through the inhibition of myosin phosphatase activity (Nishimura et al. 1990). We have observed that in most of the artery segments (but not in all), noradrenaline produced rhythmic oscillations of the membrane potential which were superimposed on a tonic depolarisation. Rhythmic activity was smaller in the contraction and was scarcely observed in the Ca2+ signal, probably for methodological reasons: membrane potential was recorded in one cell while Ca2+ signal and contraction were measured at the level of the tissue and were the average of the activity of a population of cells.

Effects of NO donors on the responses to noradrenaline

In the noradrenaline-stimulated arteries, vasorelaxation in response to the NO donors SNAP and SIN-1 was associated with parallel changes in membrane potential and in [Ca2+]cyt. The observation that SNAP did not change [Ca2+]cyt independently of a change in membrane potential suggests that the NO donor does not directly interact with Ca2+ influx, efflux or storage processes. In line with several reports showing direct (Bolotina et al. 1994; Mistry & Garland, 1998) or cyclic GMP-dependent (Carrier et al. 1997) activation of K+ channel current by NO, K+ channels were important candidates for mediating the effect of SNAP on membrane potential. In agreement with these reports, using freshly isolated smooth muscle cells from the mesenteric artery in patch-clamp experiments, we have observed a 70 % increase of Ca2+-activated K+ channel current by SNAP (5 μm) at a test potential of +30 mV (J.-P. Gomez, unpublished data). In the mesenteric artery, as in many arteries, K+ channel blockers produced a depolarisation and a contraction, consistent with a role for K+ channels in the regulation of resting membrane potential (Nelson & Quayle, 1995; Brayden, 1996) but they did not affect the responses to noradrenaline. None of 4-aminopyridine, glibenclamide, charybdotoxin + apamin, blockers of Kv, KATP and large (BKCa) and small (SKCa) conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels, respectively (Nelson & Quayle, 1995), or a combination of all blockers, suppressed the effects of SNAP or SIN-1 on membrane potential, Ca2+ signal and contractile tension. The only significant effect of the association of charybdotoxin and apamin, and of the cocktail of blockers, was a small decrease in the potency of SNAP at inhibiting the Ca2+ signal. This observation is consistent with the reported activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels by NO but it might also be related to the larger depolarisation and increase in [Ca2 +]cyt produced by the Ca2+-activated K+ channel blockers. When the KCl concentration in the bathing solution was increased to 25 mM, SNAP selectively inhibited the component of the depolarisation and the increase in [Ca2+]cyt evoked by noradrenaline, but not the responses evoked by KCl, indicating that the effects of SNAP on membrane potential and Ca2+ signal were not affected by a reduction of the electrochemical gradient of K+. This result confirmed that activation of K+ channels does not play a major role in the effects of NO donors in noradrenaline-activated artery. Since charybdotoxin has been reported to block vasorelaxation in response to NO in other arteries (Plane et al. 1996), important differences in the involvement of K+ channels could exist between different vascular beds, as suggested by the differential regional distribution of K+ channel subtypes in conduit and resistance pulmonary artery (Archer et al. 1996). The experiments with cromakalim also revealed marked differences between the effects of a K+ channel opener and those of NO donors. In resting arteries, as in noradrenaline-stimulated arteries, the opening of K+ channels produced a hyperpolarisation of 15–25 mV. On the other hand, NO donors only changed resting membrane potential by a maximum of 3 mV and, in noradrenaline-stimulated arteries, the effect on the arteries was restricted to the reversal of the depolarisation evoked by noradrenaline. Moreover, complete relaxation of the noradrenaline-evoked contraction by cromakalim was observed for membrane potential values significantly more negative than when SNAP or SIN-1 was used, which suggests that another mechanism has to be involved in the vasorelaxation evoked by NO donors. Prevention of Cl− channel opening following noradrenaline stimulation has been proposed to explain the suppression by endothelium-derived NO of the potentiation of noradrenaline-evoked contraction of rat aorta by low Cl− buffer (Lamb & Barna, 1998b). However, in cat tracheal smooth muscle stimulated with carbachol, the inhibition of Cl− channel current by NO donors does not result from direct interaction with the Ca2+-dependent Cl− channel but has been suggested to result from the action of NO at a site between the muscarinic receptor and the IP3 receptors (Waniishi et al. 1998). The present results provide evidence to confirm this hypothesis and demonstrate that the inhibition by SNAP of noradrenaline-evoked contraction was associated with the inhibition of the accumulation of IPs. The inhibition of IPs accumulation correlates with the inhibition of the contraction when both responses were measured under the same experimental conditions. Indeed, a tenfold difference was observed in the vasorelaxant potency of SNAP according to the protocol that was applied: pretreatment of the artery with SNAP resulted in a lower inhibition of the contraction than application of SNAP during a sustained contraction (relaxation protocol). The major difference between these two protocols was that in the ‘relaxation protocol’, peak effect, which occurred within 30 s of the addition of SNAP, was measured, while in the ‘pretreatment protocol’ the effect of SNAP was estimated over a time interval of 30 min. The difference in SNAP potency might be related to the inactivation of NO in aqueous solution. The ability of NO and cyclic GMP to inhibit the accumulation of IPs was first reported by Rapoport in rat aorta (Rapoport, 1986) but the precise site of action of NO still needs to be identified. Our results obtained with AlF4−, which directly activates G proteins, showed that SNAP inhibited contraction, [Ca2+]cyt and depolarisation in a manner similar to that in noradrenaline-stimulated arteries, suggesting that SNAP acts on a step of the activation process which is downstream of the receptor-G protein interaction. These results are consistent with the report that cyclic GMP inhibits IP3 formation in rat aorta segments by causing an uncoupling of the agonist-activated G protein and phospholipase C (Hirata et al. 1990). Inhibition of noradrenaline-induced synthesis of IPs by hyperpolarisation has also been reported (Itoh et al. 1992), but the observation that SNAP-mediated inhibition of IPs accumulation was not abolished in the presence of 40 mM KCl indicates that it could not be caused by a change in membrane potential. The observed inhibition by SNAP of the accumulation of IPs provides an explanation for the multiple effects of the NO donor on the responses to noradrenaline. Indeed, the blockade of the activation of PLC, which according to the model of the group of Mironneau (Loirand et al. 1990) constitutes the initial event in the excitation-contraction coupling process activated by noradrenaline, prevents the activation of all the subsequent steps in the excitation pathway, in particular membrane depolarisation and Ca2+ entry. Conversely, a depolarisation that was not mediated through G protein activation, such as the depolarisation evoked by high-KCl solution, was not sensitive to the inhibitory action of SNAP. Since the present results were obtained with exogenous NO donors, further experiments should investigate whether endothelium-derived NO exhibits the same me chanism of action. Indeed, the uncoupling by NO of G protein-PLC activation could be responsible for the observation that endothelium-derived NO decreases the responses of several arteries to agonists (Eglème et al. 1984), an effect that has been reported to be related to a decrease in agonist efficacy (Alosachie & Godfraind, 1988). Further experiments should investigate the nature of the interaction of NO with the G protein-PLC activation and the precise site of its action.

Effects of SNAP in arteries depolarised by high-KCl solution

The inhibition by NO and cyclic GMP of voltage-operated Ca2+ channel (VOC) activity has been reported in isolated smooth muscle cells from guinea-pig basilar artery and from human coronary artery (Tewari & Simard, 1997; Quignard et al. 1997). Importantly, in arteries contracted by high-KCl concentration, which causes Ca2+ influx through depolarisation-evoked opening of VOCs, the relaxation evoked by SNAP was observed without any change in membrane potential or in [Ca2+]cyt, suggesting that this compound did not affect voltage-activated Ca2+ entry in isolated arteries. The KCl concentration used to stimulate the artery was chosen to produce a level of contraction similar to that obtained with noradrenaline, although it produced a larger depolarisation and a slightly higher increase in [Ca2+]cyt than did noradrenaline. This observation is in agreement with the increase by noradrenaline of the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile filaments (Nishimura et al. 1990). Larger responses to KCl compared with noradrenaline could not be responsible for the lack of effect of SNAP on membrane potential and [Ca2+]cyt since SNAP also did not affect these parameters when lower KCl concentrations (20–25 mM) were used (not shown). However, lower KCl concentrations produced unstable contractions and therefore were useless when relaxation had to be estimated. The absence of effect of SNAP on [Ca2+]cyt in KCl-depolarised artery is in agreement with our previous report that bromo-cyclic GMP does not affect KCl-evoked Ca2+ influx in the rat aorta (Salomone et al. 1995) and with the reports that show that vasorelaxation evoked by NO is caused by a cyclic GMP-dependent decrease in the sensitivity of the contractile machinery to Ca2+ (Nishimura et al. 1988; Karaki et al. 1988; Tran et al. 1998).

In conclusion, it is clear from the present results as well as from the literature, that NO operates at multiple sites in the vascular smooth muscle cell. It is difficult with regard to those multiple effects to distinguish which one(s) contribute to the vasorelaxation, and to what degree. The present results confirmed that the extent by which different mechanisms contribute to relaxation may depend on the type of foregoing contraction (Plane et al. 1998). The results indicated that, in KCl-contracted rat mesenteric artery, the decrease in the sensitivity of the contractile machinery to Ca2+ is the most important mechanism involved in the relaxation by SNAP, since the vasorelaxation is not dependent on a change in [Ca2+]cyt. In the noradrenaline-stimulated superior mesenteric artery of the rat, the vasorelaxation evoked by SNAP runs parallel to its effects on membrane potential and [Ca2+]cyt and on accumulation of IPs. The lack of effect of K+ channel blockers indicates that K+ channel activation does not play a major role in the vasorelaxation. On the other hand, the inhibition of IPs accumulation suggests that NO donors interact with an early step of the excitation-contraction coupling process and in that way prevent the membrane depolarisation, the increase in [Ca2+]cyt and the contraction evoked by noradrenaline.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Lambert and D. Kinnard for their skilful technical assistance and Professor T. Godfraind for useful discussion. J.-P. Gomez was supported by a grant from INSERM (Bourse de formation à l’étranger). This work was supported by grant ARC 95/00-188 from the General Direction of Scientific Research of the French Community of Belgium and by a grant from the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique Médicale (grant 3.4534.98).

References

- Alosachie I, Godfraind T. The modulatory role of vascular endothelium in the interaction of agonists and antagonists with α-adrenoceptors in the rat aorta. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1988;95:619–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amédée T, Benham CD, Bolton TB, Byrne NG, Large WA. Potassium, chloride and non-selective cation conductances opened by noradrenaline in rabbit ear artery cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;423:551–568. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Huang JMC, Hampl V, Nelson DP, Schultz PJ, Weir EK. Nitric oxide and cGMP cause vasorelaxation by activation of a charybdotoxin-sensitive K channel by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:7583–7587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Huang JMC, Reeve HL, Hampl V, Tolarova S, Michelakis E, Weir EK. Differential distribution of electrophysiologically distinct myocytes in conduit and resistance arteries determines their response to nitric oxide and hypoxia. Circulation Research. 1996;78:431–442. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM. Role of activation of calcium sensitive K+ channels in NO and hypoxia induced pial artery vasodilation. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:H1785–1790. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.4.H1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotina VM, Najibi S, Palacino JJ, Pagano PJ, Cohen RA. Nitric oxide directly activates calcium-dependent potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Nature. 1994;368:850–853. doi: 10.1038/368850a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonen HCM, De Mey JGR. G-proteins are involved in contractile responses of isolated mesenteric resistance arteries to agonists. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1990;342:462–468. doi: 10.1007/BF00169465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayden JE. Potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1996;23:1069–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AR, Rhodes P. Chemistry, analysis, and biological roles of S-nitrosothiols. Analytical Biochemistry. 1997;249:1–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier GO, Fuchs LC, Winecoff AP, Giulumian AD, White RE. Nitrovasodilators relax mesenteric microvessels by cGMP-induced stimulation of Ca-activated K channels. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:H76–84. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Suzuki H, Weston AH. Acetylcholine releases endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor and EDRF from rat blood vessels. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1988;95:1165–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Plane F, Najibi S, Huk I, Malinski T, Garland CJ. Nitric oxide is the mediator of both endothelium dependent relaxation and hyperpolarization of the rabbit carotid artery. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:4193–4198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell TL, Pryzwansky KB, Wyatt TA, Lincoln TM. Regulation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum protein phosphorylation by localized cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells. Molecular Pharmacology. 1991;40:923–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglème C, Godfraind T, Miller RC. Enhanced responsiveness of rat isolated aorta to clonidine after removal of the endothelial cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1984;81:16–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1984.tb10736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exton JH. Phosphoinositide phospholipases and G proteins in hormone action. Annual Review of Physiology. 1994;56:349–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feelisch M, Ostrowski J, Noack E. On the mechanism of NO release from sydnonimines. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1989;14(suppl. 11):S13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland CJ, Mcpherson GA. Evidence that nitric oxide does not mediate the hyperpolarization and relaxation to acetylcholine in the rat small mesenteric artery. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;105:429–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Hirata M, Itoh T, Kanmura Y, Kuriyama H. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate activates pharmacomechanical coupling in smooth muscle of the rabbit mesenteric artery. The Journal of Physiology. 1986;370:605–618. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata M, Kohse KP, Chang CH, Ikebe T, Murad F. Mechanism of cyclic GMP inhibition of inositol phosphate formation in rat aorta segments and cultured bovine aortic smooth muscle cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:1268–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Seki N, Suzuki S, Ito S, Kajikuri J, Kuriyama H. Membrane hyperpolarization inhibits agonist-induced synthesis of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate in rabbit mesenteric artery. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;451:307–328. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaki H, Sato K, Ozaki H, Murakami K. Effects of sodium nitroprusside on cytosolic calcium level in vascular smooth muscle. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1988;156:259–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippeit-Drews P, Morel N, Godfraind T. Effect of nitric oxide on membrane potential and contraction of rat aorta. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1992;20:S72–75. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199204002-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroiwa M, Aoki H, Kobayashi S, Nishimura J, Kanaide H. Role of GTP-protein and endothelium in contraction induced by ethanol in pig coronary artery. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;470:521–537. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb FS, Barna TJ. Chloride ion currents contribute functionally to norepinephrine-induced vascular contraction. American Journal of Physiology. 1998a;275:H151–160. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.1.H151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb FS, Barna TJ. The endothelium modulates the contribution of chloride currents to norepinephrine-induced vascular contraction. American Journal of Physiology. 1998b;275:H161–168. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.1.H161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loirand G, Pacaud P, Mironneau C, Mironneau J. GTP-binding proteins mediate noradrenaline effects on calcium and chloride currents in rat portal vein myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;428:517–529. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry DK, Garland CJ. Nitric oxide (NO)-induced activation of large conductance Ca2+-dependent K+ channels (BKCa) in smooth muscle cells isolated from the rat mesenteric artery. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;124:1131–1140. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel N, Godfraind T. Characterization in rat aorta of the binding sites responsible for blockade of noradrenaline-evoked calcium entry by nisoldipine. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1991;102:467–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvany MJ, Halpern W. Contractile properties of small arterial resistance vessels in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Circulation Research. 1977;41:19–25. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ME, Brayden JE. Nitric oxide hyperpolarizes rabbit mesenteric arteries via ATP-sensitive potassium channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:47–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:C799–822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Standen NB, Brayden JE, Worley JF. Noradrenaline contracts arteries by activating voltage-dependent calcium channels. Nature. 1998;336:382–385. doi: 10.1038/336382a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura J, Khalil RA, Drenth JP, van Breemen C. Evidence for increased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in norepinephrine-activated vascular smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;259:H2–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.1.H2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura J, Kolber M, Van Breemen C. Norepinephrine and GTP-γ-S increase myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in α-toxin permeabilized arterial smooth muscle. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1988;157:677–683. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plane F, Garland CJ. Differential effects of acetylcholine, nitric oxide and levcromakalim on smooth muscle membrane potential and tone in the rabbit basilar artery. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;110:651–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plane F, Hurrell A, Jeremy JY, Garland JG. Evidence that potassium channels make a major contribution to SIN-1-evoked relaxation of rat isolated mesenteric artery. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;119:1557–1562. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plane F, Pearson T, Garland CJ. Multiple pathways underlying endothelium-dependent relaxation in the rabbit isolated femoral artery. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1994;115:31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plane F, Wiley KE, Jeremy JY, Cohen RA, Garland CJ. Evidence that different mechanisms underlie smooth muscle relaxation to nitric oxide and nitric oxide donors in the rabbit isolated carotid artery. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;123:1351–1358. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quignard JF, Frapier JM, Harricane MC, Albat B, Nargeot J, Richard S. Voltage-gated calcium channel currents in human coronary myocytes. Regulation by cyclic GMP and nitric oxide. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;99:185–193. doi: 10.1172/JCI119146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand VE, Garland CJ. Endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine in the rabbit basilar artery: importance of membrane hyperpolarization. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;106:143–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport RM. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate inhibition of contraction may be mediated through inhibition of phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis in rat aorta. Circulation Research. 1986;58:407–410. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson BE, Schubert R, Hescheler J, Nelson MT. cGMP-dependent protein kinase activates Ca-activated K channels in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;265:C299–303. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.1.C299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomone S, Morel N, Godfraind T. Effects of 8-bromo cyclic GMP and verapamil on depolarization-evoked Ca2+ signal and contraction in rat aorta. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;114:1731–1737. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomone S, Silva CLM, Morel N, Godfraind T. Facilitation of the vasorelaxant action of calcium antagonists by basal nitric oxide in depolarized artery. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1996;354:505–512. doi: 10.1007/BF00168443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari K, Simard JM. Sodium nitroprusside and cGMP decrease Ca2+ channel availability in basilar artery smooth muscle cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1997;433:304–311. doi: 10.1007/s004240050281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran NNP, Spitzbarth E, Robert A, Giummelly P, Atkinson J, Capdeville-Atkinson C. Nitric oxide lowers the calcium sensitivity of tension in the rat tail artery. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:163–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.163bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usachev YM, Marchenko SM, Sage SO. Cytosolic calcium concentration in resting and stimulated endothelium of excised intact rat aorta. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;489:309–317. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanheel B, Van Voorde J. Nitric oxide induced membrane hyperpolarization in the rat aorta is not mediated by glibenclamide-sensitive potassium channels. Canadian The Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1997;75:1387–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waniishi Y, Inoue R, Morita H, Teramoto N, Abe K, Ito Y. Cyclic GMP-dependent but G-kinase-independent inhibition of Ca2+-dependent Cl− currents by NO donors in cat tracheal smooth muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;511:719–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.719bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidelt T, Boldt W, Markwardt F. Acetylcholine induced K+ currents in smooth muscle cells of intact rat small arteries. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:617–630. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Katz A, Lee Ch, Simon MI. Activation of phospholipase C by alpha 1-adrenergic receptors is mediated by the alpha subunits of Gq family. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;25:25798–25802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssif M, Kadavil EA, Oriowo MA. Heterogeneity of alpha(1)-adrenoceptor mediating noradrenaline-induced contractions of the rat superior mesenteric artery. Pharmacology. 1998;56:196–206. doi: 10.1159/000028198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan XJ, Bright RT, Aldinger AM, Rubin LJ. Nitric oxide inhibits serotonin-induced calcium release in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:L44–50. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.1.L44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan XJ, Tod M, Rubin LJ, Blaustein MP. NO hyperpolarizes pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and decreases the intracellular Ca2+ concentration by activating voltage-gated K+ channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:10489–10494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]