Abstract

Patch recordings from Xenopus oocytes indicated that mechanically gated (MG) channels are expressed at a uniform surface density (∼1 channel μm−2) with an estimated > 3 × 106 MG channels per oocyte that could generate microamps of current at ± 50 mV.

Removal of external Ca2+ induced a membrane conductance that differed from MG channels in ion selectivity, pharmacology and sensitivity to connexion-38 antisense oligonucleotides.

Depolarization to +50 mV activated a Na+-selective, a Cl−-selective and a non-selective conductance. Hyperpolarization to −150 mV activated a non-selective conductance. None of these conductances appeared to be mediated by MG channels.

Hypotonicity (25 %) failed to evoke any change in membrane conductance in the majority of defolliculated oocytes. Hypertonicity (200 %) evoked a large non-selective (PK/PCl≈ 1) membrane conductance that was not blocked by 100 μM Gd3+.

Although the above stimuli could activate a variety of whole-oocyte conductances, including three novel conductances, they did not involve MG channel activation. Possible mechanisms underlying the discrepancy between observed conductances and those anticipated from patch-clamp studies are discussed.

The Xenopus oocyte is commonly used for heterologous expression and cloning of membrane transport proteins (Barnard et al. 1982; Methfessel et al. 1986). However, the native oocyte also expresses its own membrane conductances (Stuhmer & Parekh, 1995). For example, the predominant single-channel activity seen in patch-clamped membrane is a mechanically gated (MG) channel that can be activated by suction or pressure applied to the membrane patch after formation of the tight seal (Methfessel et al. 1986). This channel has been well characterized in terms of its single-channel kinetics, ion selectivity, voltage sensitivity and pharmacology (Taglietti & Toselli, 1988; Yang & Sachs, 1989, 1990; Lane et al. 1991, 1992; Hamill & McBride, 1992, 1996a,b; Silberberg & Magleby, 1997; Wu et al. 1998; Reifarth et al. 1999). However, its functional role in the oocyte remains unknown (Steffensen et al. 1991; Wilkinson et al. 1998). Furthermore, although patch densities (Methfessel et al. 1986) indicate that a fully grown oocyte may express in excess of one million MG channels, there have been no reports of a whole-cell MG conductance.

Clearly, demonstration of a macroscopic MG conductance activated by stimuli that the oocyte might encounter under normal circumstances would reinforce the idea that the MG channel plays a functional role rather than merely arises as a consequence of tight seal patch formation (Morris & Horn, 1991). Therefore, in this series of three papers we report a systematic search for the whole-cell correlate of single MG channel activity. In this first study, we tested three different forms of stimuli known to increase single MG channel conductance or open probability. The stimuli involve the removal of extracellular Ca2+ which otherwise blocks MG channels (Taglietti & Toselli, 1988; Yang & Sachs, 1989), prolonged membrane polarization which can partially (Hamill & McBride, 1996b) or fully open MG channels (Silberberg & Magleby, 1997) and osmotic swelling which has been recognized to activate single MG channels in patches on a variety of cell types (Hamill, 1983; Sackin, 1995). The oocyte or egg may encounter these stimuli under specific physiological or developmental conditions (e.g. during fresh water ovulation and fertilization).

METHODS

Solutions and chemicals

Normal Ringer solution (NR) contained (mm): 115 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 10 (Hepes-NaOH), 1.8 CaCl2 (pH 7.2). Barth's solution contained (mm): 88 NaCl, 1 KCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 5 Tris-Cl, 0.82 MgSO4, 0.33 Ca(NO3)2, 0.41 CaCl2 (pH 7.4), supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 each of streptomycin, penicillin and amikacin. The Ca2+-free Ringer solution had the same composition as NR except that no Ca2+ was added. In some experiments, the NaCl in NR was replaced by sodium glutamate, KCl, potassium acetate, CsCl, TEA-Cl or TBA (tetrabutylammonium)-Cl (pH 7 in all cases, adjusted with Hepes-NaOH for Na+, Hepes-KOH for K+ solutions and free Hepes for other solutions) of various concentrations in order to measure the ion selectivity of specific conductances. Stripping solution contained (mm): 200 potassium aspartate, 20 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA-KOH, 10 Hepes-KOH (pH 7.4), and was used to shrink the oocyte to facilitate mechanical removal of the surrounding vitelline membrane (Methfessel et al. 1986). Mannitol was added to solutions to adjust the osmolarity while maintaining the ionic strength constant. GdCl3 was purchased from Aldrich, BAPTA AM from Molecular Probes and all other chemicals from Sigma.

Preparation of Xenopus oocytes

Mature female frogs (Xenopus laevis) were purchased from two different sources, Xenopus I (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and Nasco (Modesto, CA, USA). We noticed no differences in results using frogs from the different vendors. The preparation and storage of Xenopus oocytes have been described before (Lane et al. 1991; Zhang et al. 1998). Briefly, frogs were anaesthetized by being bathed for approximately 20 min in a beaker containing 300 mg ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methanesulphonic acid (Aldrich) in 200 ml of distilled water. Sterile surgical procedures were used to remove oocytes that were then treated with collagenase (1–4 mg ml−1) at room temperature for 1–2 h in NR. Immediately after surgery the frogs were placed in a small aquarium and monitored for recovery based on their free-swimming behaviour. Approximately 3 months after the first surgery, the frogs underwent a second non-survival surgery and were killed by decapitation while under anaesthesia. All procedures were carried out according to the guidelines laid down by the animal welfare committee of the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB). Electrophysiological measurements were performed on oocytes within 7 days of their removal from the frog. In most cases, the collagenase-treated oocytes were manually defolliculated to facilitate microelectrode penetration. Only oocytes with initial membrane potentials of at least −30 mV were studied. For all patch-clamp studies the vitelline membrane was manually removed with forceps after incubating oocytes in stripping solution for about 5 min (Methfessel et al. 1986). Recordings were typically made between 10 and 30 min after stripping. For some whole-oocyte recordings, the vitelline membrane was removed without the use of stripping solution to avoid activation of hypertonicity-induced currents. Although devitellinated oocytes were more fragile, no differences were observed in specific conductances when compared with those in vitelline-enclosed oocytes

Whole-cell voltage clamp and data analysis

Whole-cell recordings were carried out using a three-microelectrode voltage-clamp configuration (see Zhang et al. 1998). Membrane potentials and currents were digitized by a PC computer through a Lab Master DMA 100 kHz data acquisition and control board using FastLab software (Indec Systems, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). Voltage ramps were generated by a custom-built circuit controlled by the computer. All results are expressed as means ± s.e.m. unless otherwise indicated. To estimate the ion selectivity of a specific conductance, reversal potentials measured in various extracellular solutions were fitted to the constant field equation (Hille, 1992; Zhang et al. 1998).

Synthesis and microinjection of antisense oligonucleotides

Antisense oligonucleotides against connexin-38 (Cx-38) and scrambled antisense oligonucleotides were synthesized in the Sealy Centre of Molecular Biology, UTMB, according to Ebihara (1996). Oocytes were injected with oligonucleotides (40 ng per oocyte) according to Zhang et al. (1998).

Patch clamp and pressure clamp

For patch-clamp studies, the cell-attached or inside-out patch configuration was used (Hamill et al. 1981). To mechanically activate MG channels, steps of suction or pressure were applied to the patch pipette using the pressure-clamp technique (McBride & Hamill, 1992; Hamill & McBride, 1995). Our standard pipettes made from thin-walled borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments) had an estimated internal pipette tip diameter of ∼2 μm. In specific experiments, membrane patch capacitance (Cm) measurements were used to estimate membrane patch area assuming a specific Cm of 1 μF cm−2. In these measurements, the pipette was coated with Sylgard (Dow-Corning) to within ∼100 μm of the tip to minimize the pipette Cm (see Hamill et al. 1981). The combination of patch and pipette capacitance was measured using the calibrated dial of the EPC7 capacitance compensation to cancel the fast current transient in response to voltage steps. The specific contribution of the pipette capacitance was estimated (20–50 fF) after excising the patch (i.e. inside-out patch) and gently pressing the pipette tip into a Sylgard ball attached to a glass probe (Sakmann & Neher, 1983). In all cases, special care was taken to form ‘gently’ sealed patches by applying suctions of less than 5 mmHg for less than 10 s using the pressure clamp (Hamill & McBride, 1992, 1997).

RESULTS

Macroscopic currents anticipated from patch-clamp recordings

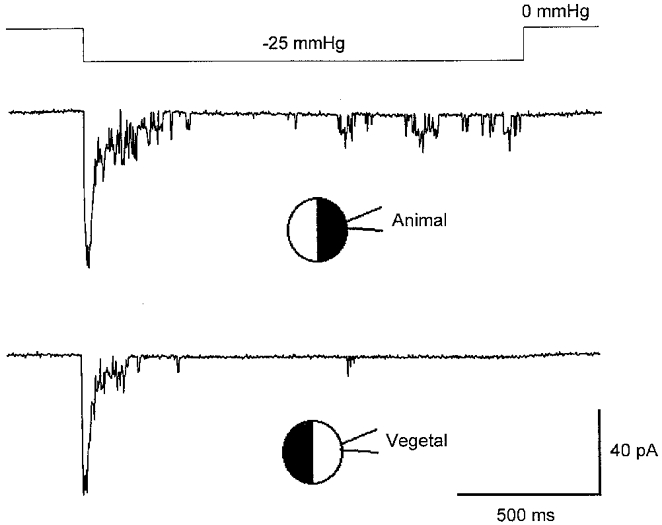

To predict the increase in membrane conductance expected from MG channel activation, we first made estimates of MG channel density and specifically tested for uniformity in MG channel surface distribution. Figure 1 shows MG channel currents activated in cell-attached membrane patches formed on the animal and vegetal pole of the same oocyte. The recordings indicate similar single MG channel current amplitudes (∼7 pA), maximal number of activated MG channels (∼10) and fast adaptation kinetics (the channels tended to close within 200 ms). Similar recordings from the animal (60 ± 11 pA, n = 15 patches) and vegetal (62 ± 14 pA, n = 19 patches) poles of other oocytes also indicated a uniform distribution of MG channels. This uniform distribution contrasts with the asymmetrical distribution of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels on the animal and vegetal poles of oocytes (Gomez-Hernandez et al. 1997).

Figure 1. MG channel activity in cell-attached patches on vegetal and animal hemispheres.

Recordings of MG channel activity measured in different patches from the animal and vegetal hemispheres of the same oocyte. The upper trace shows the suction step (-25 mmHg) applied to both patches. The recordings were made with the different pulled halves (pipette tip diameter = ≈ 2 μm) of a single pipette capillary tube. The membrane potential was −100 mV and the pipette solution contained (mm): 100 KCl, 10 Hepes-KOH, 2 EGTA-KOH.

The membrane patch area in our standard (∼2 μm internal tip diameter) pipettes was ∼10 μm2, estimated from a measured average patch capacitance of 112 ± 21 fF (n = 6 patches) and assuming a specific Cm of 1 μF cm−2. Thus, our results indicate a uniform membrane channel density of ∼1 MG channel μm−2, consistent with the earlier estimate made by Methfessel et al. (1986), and would predict more than 3 × 106 MG channels per oocyte, assuming a 1 mm diameter smooth sphere. The anticipated whole-cell MG channel currents, calculated using eqn (1),

| (1) |

where I, γ, N, Po and ΔV represent the whole-cell current, single-channel conductance, total number of channels, open probability and driving force, respectively, are listed in Table 1 for different Po values. These values can be considered lower estimates because the oocyte membrane, rather than being smooth, has numerous folds and microvilli which may increase the total membrane surface area as much as 10-fold (Bluemink et al. 1983; Zampighi et al. 1995). Below we describe attempts to evoke whole-oocyte MG currents by applying stimuli previously shown to increase single MG channel γ or Po.

Table 1.

Anticipated whole-cell MG channel current in Xenopus oocytes

| 2 mm Ca2+ Ringer | Ca2+-free Ringer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +50 mV (γ = 12 pS) | −150 mV (γ = 25 pS) | −50 mV (γ = 25 pS) | −50 mV (γ = 80 pS) | |||||

| Po | I (nA) | g (nS) | I (nA) | g (nS) | I (nA) | g (nS) | I (nA) | g (nS) |

| 0.0001 | 0.2 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 0.3 | 2 | 1 | 25 |

| 0.0010 | 2 | 33 | 11 | 79 | 3 | 23 | 10 | 252 |

| 0.0100 | 23 | 330 | 110 | 786 | 31 | 230 | 101 | 2500 |

| 0.1000 | 230 | 3830 | 1100 | 7860 | 314 | 2250 | 1010 | 25 250 |

| 1.0000 | 2300 | 38 330 | 11 000 | 78 600 | 3140 | 22 460 | 10 100 | 252 500 |

γ and g represent single-channel and whole-cell conductances, respectively.

Is the Ca2+-inactivated (Ic) current mediated by MG channels?

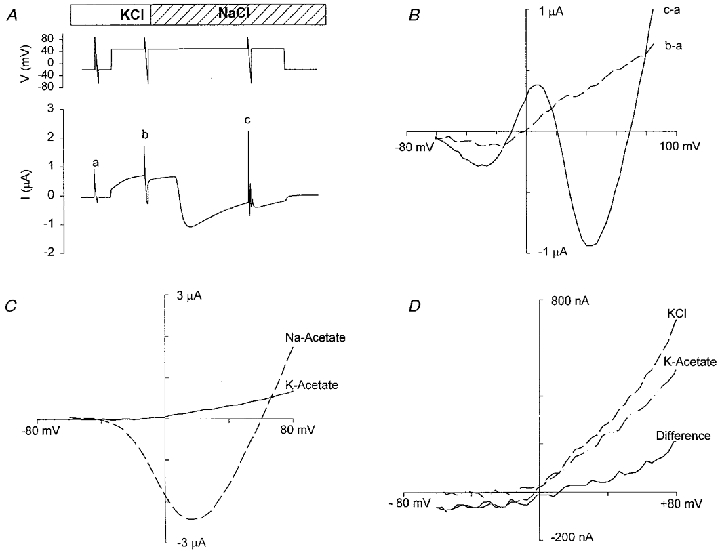

Any contribution that the reported spontaneous MG channel openings (e.g. see Methfessel et al. 1986; Reifarth et al. 1999) make to the resting oocyte conductance should be increased by the removal of external Ca2+ because Ca2+ (1.8 mm) in NR blocks the MG channel (Taglietti & Toselli, 1988; Yang & Sachs, 1989; see Table 1). In fact, Ca2+-free Ringer solution does induce a large increase in membrane conductance. For example, the typical resting conductance of oocytes at −40 mV is 3.1 ± 0.3 μS in NR and increases to 187 ± 68 μS (11 oocytes, 3 frogs) in Ca2+-free Ringer solution. This conductance increase is blocked by the MG channel blockers Gd3+, amiloride and gentamicin (Zhang et al. 1998). Furthermore, as indicated in Fig. 2, both Ca2+-inactivated currents (Ic) (Fig. 2A) and MG channel currents (Fig. 2B) reverse at around −10 mV. However, recent studies indicate that the Ic conductance is most probably mediated by endogenous hemi-gap-junctional (hemi-gap) channels (i.e. Cx-38) (Ebihara, 1996; Zhang et al. 1998). The experiments described below specifically examine the possible relationship between hemi-gap and MG channels.

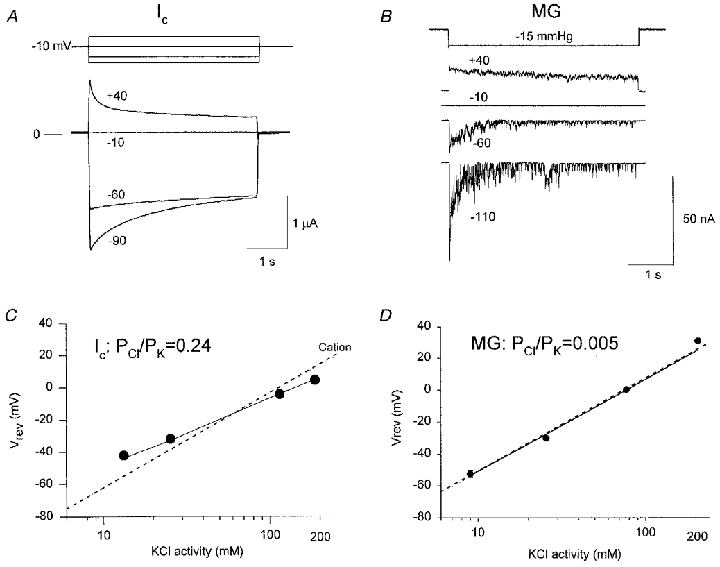

Figure 2. Ic and MG channel currents and reversal potential as functions of voltage and extracellular KCl activity, respectively.

A, Ic current recordings of a voltage-clamped oocyte in response to voltage pulses. B, MG channel currents in a cell-attached patch elicited in response to repetitive suction pulses at different membrane potentials. C, Ic reversal potential as a function of extracellular KCl activity (10 oocytes, 2 frogs). D, MG channel reversal potential as a function of KCl activity (10 inside-out patches). Points are means of measured reversal potentials. Some s.e.m. bars are concealed by the data points. The continuous lines were calculated according to the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) equation, with the relative permeabilities obtained by curve fitting (PCl/PK = 0.24 and PCl/PK < 0.01, for Ic and MG channel, respectively). The dotted lines were calculated according to the GHK equation, assuming an ideally cation-selective conductance.

Ic conductance was initially reported to be cation selective (the Na+: K+ permeability ratio (PNa/PK) ≈ 1) (Arellano et al. 1995). However, as indicated in Fig. 2C, Ca2+-inactivated channel also displays a small but finite Cl− permeability (PCl/PK = 0.24; see Zhang et al. 1998). Although the oocyte MG channel is generally considered to be cation selective (Methfessel et al. 1986), examination of specific published data indicated less than ideal cation-selective behaviour (see Fig. 4 of Taglietti & Toselli, 1988). We therefore re-did these experiments using the better-defined transmembrane ionic conditions of inside-out patches. Our results, summarized in Fig. 2D, confirm that the MG channel is a cation-selective channel with insignificant Cl− permeability (PCl/PK < 0.005).

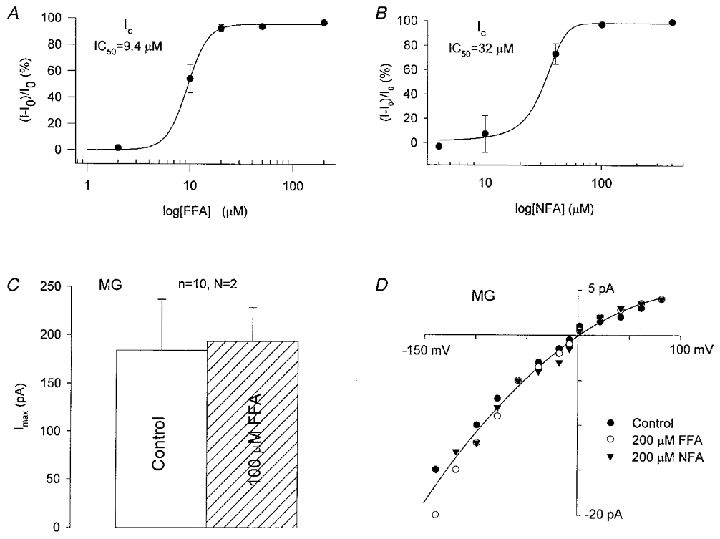

Figure 4. Comparison of the effects of flufenamic acid (FFA) and niflumic acid (NFA) on Ic and MG channels.

A and B, dose-inhibition curves for the block of Ic by FFA and NFA measured in Ca2+-free Ringer solution. Data points show percentage inhibition. The continuous lines are best fits to the data. C, comparison of the maximal MG channel currents (Imax) in response to pressure pulses in cell-attached membrane patches with standard pipette solution (100 mm KCl, 5 mm Hepes-KOH) with and without 100 μM FFA. D, single MG channel I–V relations measured in standard pipette solution with and without 200 μM FFA or 200 μM NFA present.

The Ic conductance displays significant permeability to TEA+ and TBA+ (PTEA/PK = 0.35, PTBA/PK = 0.2; see Zhang et al. 1998). In comparison, we found that the MG channel displays much lower permeability to TEA+ and TBA+. Specifically, the reversal potential of MG currents in 100 mm TEA-Cl was −48.2 ± 15.8 mV (n = 3 patches), indicating a PTEA/PK of 0.15, while the reversal potentials in 100 mm TBA-Cl (-61.3 ± 7.2 mV) and in 90 mm TBA-Cl and 10 mm KCl (-52.5 ± 5.7 mV) indicated a PTBA/PK of ∼0.05 (n = 4 patches).

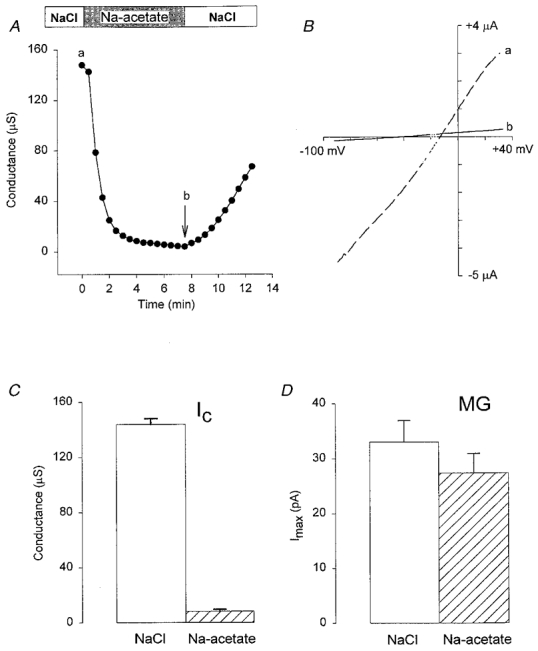

As shown in Fig. 3A–C, Ca2+-inactivated and MG channels differ qualitatively in their sensitivity to block by external acetate. Perfusion of the oocyte with sodium acetate caused a complete block of Ic conductance that only recovered slowly after returning to NR (Fig. 3A). In comparison, MG channel activity was unaffected by external acetate (Fig. 3D). We believe acetate blocks Ic conductance by intracellular acidification, rather than by acting as an impermeant anion, because gluconate, a larger anion, permeates but does not block Ic (PGluc/PCl≈ 1; Zhang et al. 1998). Furthermore, this pH sensitivity would be consistent with Ic being mediated by hemi-gap channels (Ebihara, 1996; see below). The apparent lack of residual Ic in acetate indicates little contribution of MG channels (i.e. < 5 %) to the Ca2+-inactivated conductance.

Figure 3. The effect of extracellular acetate on Ic and MG channels.

A shows the time course of Ic conductance block and recovery from block after switching from NaCl to sodium acetate and back. B shows the I–V relations before (a, dashed line) and after (b, continuous line) perfusion with acetate solution. C, histogram showing Ic conductance measured in NaCl and sodium acetate (data from 4 oocytes). D, histogram showing the maximal MG channel currents in cell-attached patches with NaCl (□) or sodium acetate ( ) in the bath and pipette solutions (data from 6 patches in each condition using paired pipettes from single pulls). NaCl solution (mm): 120 NaCl, 5 Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.2). Sodium acetate solution (mm): 120 sodium acetate, pH adjusted with free Hepes to 7.2.

) in the bath and pipette solutions (data from 6 patches in each condition using paired pipettes from single pulls). NaCl solution (mm): 120 NaCl, 5 Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.2). Sodium acetate solution (mm): 120 sodium acetate, pH adjusted with free Hepes to 7.2.

Although both the Ca2+-inactivated and MG channels are blocked by external Ca2+ they show different Ca2+ sensitivities. For example, the Ic conductance is reduced 100-fold on going from Ca2+-free Ringer solution to NR (Zhang et al. 1998), while peak MG currents (95.4 ± 6.2 pA) and single-channel currents (15.8 ± 0.8 pA) are only reduced about 5-fold with the same change in ionic conditions (to 18.6 ± 4.6 and 3.6 ± 0.3 pA, respectively; n = 6 patches, 2 oocytes at −150 mV; see also Lane et al. 1993).

Ic conductance is blocked by the MG channel blockers Gd3+, amiloride and gentamicin (Zhang et al. 1998). Dose-response relations indicate half-block concentrations of Ic of 0.6, 60 and 800 μM for Gd3+, gentamicin and amiloride, respectively (relations not shown; see Zhang, 1998), compared with ∼1, 100 and 500 μM for MG channels (Lane et al. 1991; Wilkinson et al. 1998). In contrast to these relatively small differences, the Ic and MG conductances differ more dramatically in their sensitivity to flufenamic acid (FFA) and niflumic acid (NFA). For example, as indicated in Fig. 4, both FFA and NFA produce complete block of Ic at 100 μM (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, even higher concentrations of these drugs (200 μM) included in the pipette solution failed to affect peak MG channel currents (Fig. 4C) or single MG channel current amplitudes recorded on cell-attached patches (see Fig. 4D). Furthermore, 200 μm FFA included in the bath solution did not block single MG channel currents measured in cell-attached patches or after inside-out patch formation (n = 6 patches, 1 oocyte; data not shown).

Injection of oocytes with Cx-38 antisense oligonucleotides blocks ∼90 % of the Ic conductance, providing the best evidence that Ic is mediated by the endogenous hemi-gap channel (Ebihara, 1996; Zhang et al. 1998). In comparison, we found that maximal MG channel currents were unaffected by Cx-38 antisense oligonucleotides (102 ± 14 pA, n = 9 patches in 4 oocytes) compared with scrambled Cx-38 antisense oligonucleotides injected oocytes (109 ± 9 pA, n = 9 patches in 4 oocytes). As indicated previously, the residual Ic conductance that is not blocked by Cx-38 antisense oligonucleotides (∼10 %) displays the same mixed cation/anion permeability as the unblocked Ic (see Fig. 7C of Zhang et al. 1998), ruling out the idea that MG channels mediate this residual Ca2+-sensitive conductance. Our observation that the conductance of oocytes injected with Cx-38 antisense oligonucleotides was reduced by 53 ± 10 % compared with oocytes injected with scrambled antisense oligo-nucleotides (from 3.1 ± 0.3 to 1.47 ± 0.19 μS; 11 and 13 oocytes, respectively) suggested that Ic conductance may also contribute to the oocyte's resting conductance in NR. FFA (100 μM) or Gd3+ (10 μM) produced similar reductions in oocyte resting conductance (data not shown), consistent with participation of Ic but not MG channels.

Figure 7. Depolarization-activated currents and I–V relations in different bathing solutions.

A, membrane potential and current recordings when 100 mm K+ in Ringer solution was replaced by 100 mm Na+ (NR). Top trace is the voltage protocol (depolarization pulse from −30 mV to +50 mV for 100 s). Voltage ramps of 1.5 s were applied before (a) and during (b and c) the 120 s depolarizing pulse. Bottom trace is current recording. B, I–V relations measured by the second (b–a; dashed line) and the third (c–a; continuous line) ramps after subtraction of the current of the first ramp (a). C, I–V relations of the depolarization-activated currents in 120 mm potassium acetate and 120 mm sodium acetate solution. D, I–V relations of depolarization-activated currents in 120 mm KCl, 120 mm potassium acetate solution and their difference current (KCl – potassium acetate). Each solution had a pH of 7.5, adjusted with Hepes.

Are depolarization-activated conductances mediated by MG channels?

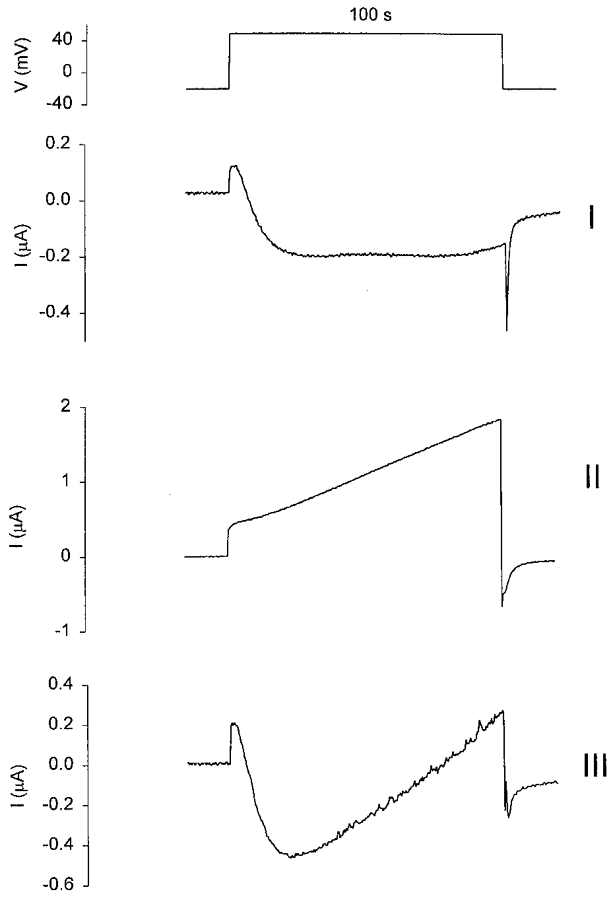

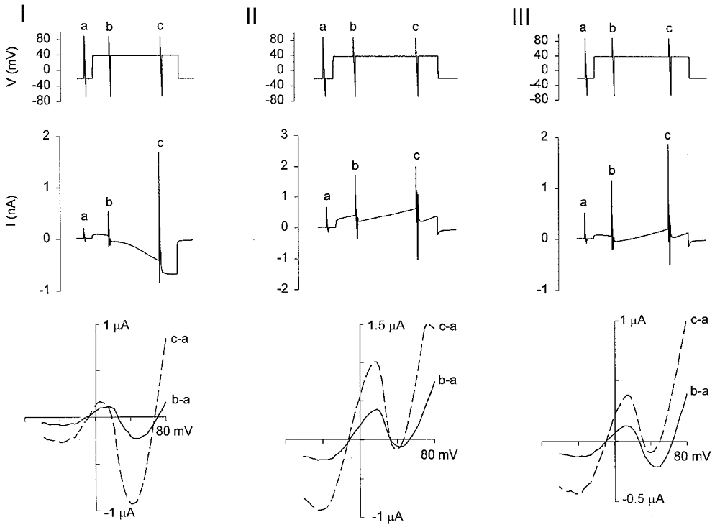

Long duration (100 s) depolarizing steps to +50 mV produced three types of current waveforms depending upon the oocyte tested (Fig. 5). For example, 25 out of 67 oocytes (3 frogs) displayed a current waveform similar to trace I in Fig. 5, 26 oocytes displayed the current waveform seen in trace II and the remaining 16 oocytes had a current waveform similar to that in trace III. Figure 6 shows I–V relations measured in different oocytes in NR during development of the three current waveforms shown in Fig. 5. The three I–V relations indicate common features in their shape, with the main difference being in the relative amplitudes of the outward and inward current components. As demonstrated below, at least three distinct ionic conductances contribute to the complex currents seen in Figs 5 and 6.

Figure 5. Three types of depolarization-activated current waveforms recorded in different oocytes.

The upper panel shows a depolarizing pulse of 100 s. The holding potential was stepped from −20 mV to +50 mV and then stepped back to −20 mV. I, II and III are the three types of current waveforms that are seen in different oocytes (67 oocytes, 3 frogs) recorded in NR.

Figure 6. Current-voltage relations of the three currents (I, II and III) similar to those shown in Fig. 5.

The upper panel of each figure is the voltage protocol. The holding potential was stepped from −20 mV to +50 mV for 100 s and then stepped back to −20 mV. Voltage ramps were applied before and within each depolarizing pulse. Each recording was obtained from a different oocyte in NR. The middle panels show the currents and the lower panels show the I–V relations of the 2nd (b–a, continuous lines) and 3rd (c–a, dashed lines) voltage ramps minus the I–V curves of the 1st ramps (a).

As shown in Fig. 7A and B, perfusion of the oocyte with a KCl solution (KCl replaced NaCl) reversibly blocked development of the inward current, consistent with a Na+-selective conductance. Isolation of this Na+ conductance was achieved by replacement of external NaCl with sodium acetate (Fig. 7D). Under these ionic conditions, the I–V relation exhibited the shape and reversal potential (+60 mV) of the slow depolarization-induced Na+ conductance previously described in Xenopus oocytes (Baud et al. 1982).

The outward currents recorded in KCl could be carried by K+, Cl− or both ions. Replacement of external KCl with potassium acetate (Fig. 7D) or potassium gluconate (not shown) reduced, but did not entirely block, the outward current, indicating that several conductances, including a Cl−-selective conductance (see difference current) contribute to the outward current. This Cl− conductance was also blocked by 4 mm Cd2+, a Ca2+ channel blocker (Hille, 1992), consistent with the Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance previously described in Xenopus oocytes (e.g. see Barish, 1983).

The outward residual current (Ir) recorded at +50 mV in potassium acetate should be free of contamination by Na+- and Cl−-selective conductances. Furthermore, external acetate blocks Ca2+-inactivated channels but not MG channels (see Fig. 3). As indicated in Fig. 8A–C, Ir is activated by depolarization to +50 mV, reaches its half-maximal value in 3–8 s after the step, is fully activated by ∼20 s, and displays slow and incomplete inactivation with prolonged depolarization. Ir ranges in size from 0.5 to 1.5 μA in different oocytes (7 oocytes, 2 donor frogs). The kinetics and strong outward rectification of Ir observed in some but not all recordings (cf. Fig. 8B and C with Fig. 8D) may reflect an outwardly rectifying K+-selective conductance (Parker & Ivorra, 1990), a cation-selective conductance, possibly via the MG channel, a non-selective conductance, or a combination of these conductances. However, a K+-selective channel seems unlikely since substitution of K+ with Cs+ in the external acetate solution increased the size of inward currents and caused positive shifts in reversal potential (Fig. 8C). This behaviour is inconsistent with the typical Cs+ impermeability of K+-selective channels (Hille, 1992). On the other hand, if the current were mediated by a cation-selective channel, one would expect reversal potential shifts of 24 mV in going from 120 mm to 30 mm potassium acetate (see Fig. 2C and D). Instead, the actual reversal potential shifts were insignificant (-5.9 ± 2.5 mV in 30 mm and −7.1 ± 2.0 mV in 120 mm, n = 4 patches). This apparent lack of ion selectivity may reflect a mixture of anion- and cation-selective channels. For example, the variable rectification properties of Ir seen in different oocytes may indicate varying inward Cl− currents (Cl− efflux) that are not blocked by replacement of external Cl− with acetate. Ir is blocked by 10 μM Gd3+ (data not shown; see Zhang, 1998). However, it is also blocked by 100 μM FFA (> 90 %, 6 oocytes 2 frogs; see Fig. 8E), ruling out a significant contribution by MG cation channels

Figure 8. Activation of the residual conductance by depolarization in potassium acetate solution and the effects of Cs+ and FFA.

A, recordings of the membrane potential and current of an oocyte in potassium acetate solution. The depolarization pulse was 120 s. B, I–V relations of Ir with the resting conductance subtracted. C, I–V relations of Ir in potassium acetate and caesium acetate. Potassium acetate solution (mm): 120 potassium acetate, 2 Hepes-KOH, 2 calcium acetate (pH 7.2). Caesium acetate solution (mm): 120 caesium acetate, 2 calcium acetate (pH 7.2, adjusted by adding Hepes directly to the solutions). D, I–V relations of Ir in potassium acetate solution in the absence and presence of 100 μM FFA.

Is the hyperpolarization-activated conductance mediated by MG channels?

Hyperpolarizing steps to −150 mV activated large non-saturating inward currents (Ih) in 12 out of 17 oocytes bathed in NR (from 3 frogs; Fig. 9A). Similar large inward currents were recorded in 100 mm KCl Ringer solution (K+ replaced Na+; data not shown). As illustrated in Fig. 9B, Ih developed faster with larger hyperpolarizing pulses. In some oocytes (2 out of 12), Ih was more voltage sensitive in that it could be activated by a hyperpolarization of −120 mV compared with other oocytes (5 out of 17) which required hyperpolarizations more negative than −180 mV. In all cases, recovery of the resting conductance after hyperpolarization was very slow (i.e. > 10 min, Fig. 9A).

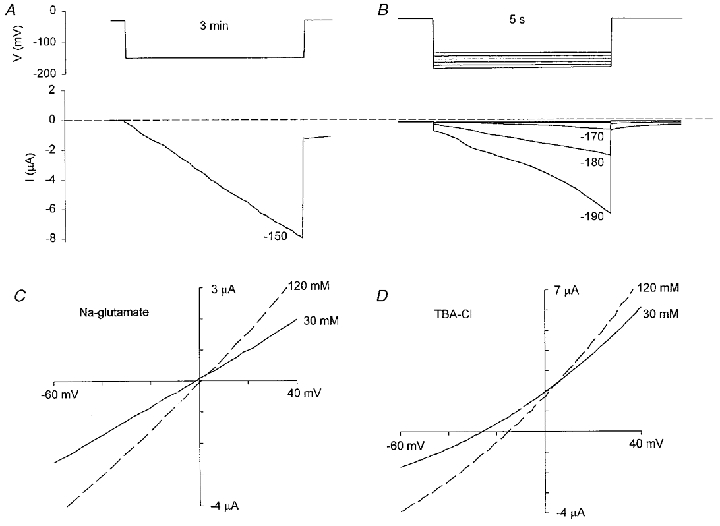

Figure 9. Hyperpolarization-induced current and its ion selectivity.

A shows the typical current induced by a hyperpolarization of −150 mV for 3 min. B shows the current responses to shorter (5 s) hyperpolarization pulses. The oocytes were held at −30 mV before the hyperpolarizing pulses were applied. C, I–V relations of Ih in 120 mm sodium glutamate and 30 mm sodium glutamate. D, I–V relations of Ih in 120 mm TBA-Cl and 30 mm TBA-Cl. I–V relations were measured by voltage ramps. All solutions contained 1 mm CaCl2 and pH was adjusted to 7.2 with free Hepes. Mannitol (180 mm) was added to the 30 mm sodium glutamate and 30 mm TBA-Cl solutions to maintain osmolarity.

Ih is a relatively non-selective current that discriminates poorly between Na+, K+ and Cl−. For example, a 10-fold change in NaCl concentration only shifted the Erev of Ih by 4.8 mV (Table 2). In comparison, one would expect a shift of > 50 mV for the MG cation channel (see Fig. 3B). The Ih conductance also shows little selectivity against large organic ions (Table 2 and Fig. 9C and D). For example, going from 120 to 30 mm sodium glutamate caused no significant shift in Erev (P > 0.05), indicating poor discrimination between Na+ and glutamate− (Pglutamate/PNa≈ 1). In comparison, similar changes in TBA-Cl concentration did cause significant Erev shifts (P < 0.05, Table 2 and Fig. 9D), indicating that TBA+ was less permeant than Na+ (PTBA/PNa≈ 0.3). Under our recording conditions we did not see the previously reported hyperpolization-activated Cl−-selective conductance that is apparently smaller in amplitude (∼100 nA), turns on faster than Ih, and, at least according to some reports, is only seen in a limited number of oocytes (cf. Parker & Miledi, 1988; Kowdley et al. 1994; Tokimasa & North, 1996).

Table 2.

Reversal potentials (mV) of Ih in various extracellular salt concentrations

| 10 mm | 24 mm | 30 mm | 120 mm | 240 mm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl | — | −9.6 ± 1.2 | — | −13.0 ± 0.6 | −15.4 ± 1.3 |

| Sodium glutamate | — | — | −7.3 ± 3.1 | −2.1 ± 1.4 | — |

| TBA-Cl | −11.3 ± 2.4 | — | −17.9 ± 1.8 | −29.8 ± 1.4 | — |

Values are means ± s.e.m.

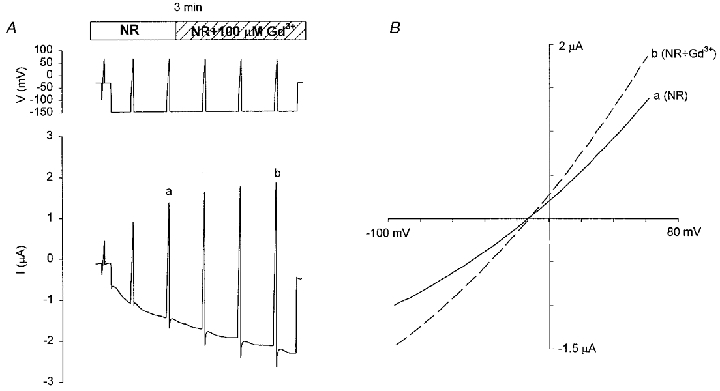

Ih was activated in oocytes treated with the cell-permeant Ca2+ chelator, BAPTA AM (100 μM for 4 h, 8 oocytes, 2 frogs) with no Erev shift compared with control. Moreover, Ih could still be activated in oocytes in which Ca2+ was replaced by 20 mm MgCl2 in NR (data not presented). These results indicate that the development of Ih does not require Ca2+ influx (i.e. through the MG channel). The absence of MG channel participation in Ih was also indicated by the lack of effect of 100 μM Gd3+ (see Fig. 10). Specifically, we found that the Erev values of Ih in NR (8 oocytes, 2 frogs) and in NR plus 100 μM Gd3+ (6 oocytes, 2 frogs) were −15.7 ± 6.3 and −11.5 ± 5.5 mV, respectively. One would expect that if either Gd3+-sensitive MG or hemi-gap channels (Erev = −10 mV) contributed to Ih then Erev should have been shifted to more negative potentials rather than the slightly more positive values.

Figure 10. Gd3+ does not block Ih.

A, 100 μM Gd3+ did not block Ih after its full activation. A 3 min hyperpolarizing pulse from −30 to −150 mV was applied along with six voltage ramps to measure the I–V relations. The lower panel shows the current responses. B, I–V relations of Ih in the absence (a, 3rd ramp) and presence (b, 6th ramp) of 100 μM Gd3+ in NR. The increased amplitude in Gd3+ reflects the time-dependent development of Ih that is apparently unaffected by 100 μM Gd3+.

Does hypotonicity activate MG channels?

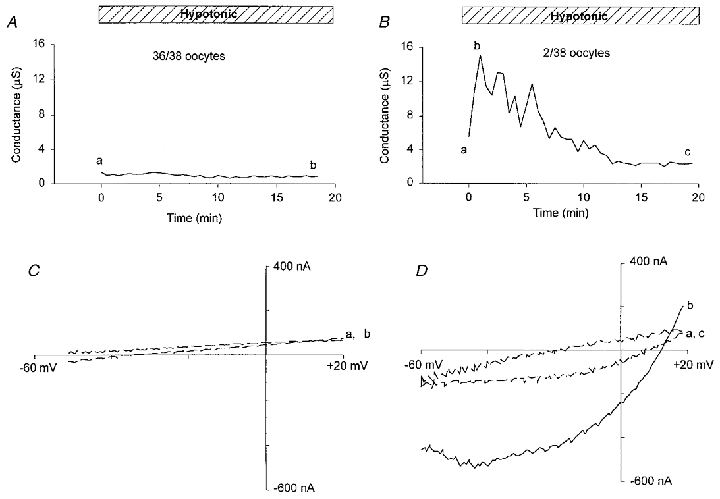

Changing from isotonic (250 mosmol l−1) to hypotonic (63 mosmol l−1) solution failed to induce a significant increase in the resting conductance of 36 out of 38 oocytes monitored for 20 min, even though significant oocyte swelling (20–30 %) occurred within this time period (Fig. 11A and C). However, in two oocytes (< 5 %) there was a reversible current increase (Ihypo) (Fig. 11B) that peaked within the first 2 min in hypotonic solution but decayed back to resting conductance levels after 10 min in hypotonic solution. Ihypo was outwardly rectifying and reversed at ∼10 mV in 30 mm NaCl solution (Fig. 11D), consistent with a Cl−-selective conductance (ECl = 10 mV; see also Ackerman et al. 1994; Arellano & Miledi, 1995) rather than a cation-selective channel (Ecat = −40 mV; see Fig. 2C). To specifically exclude the possibility that the vitelline membrane, by constraining the oocyte, blocks a swelling-induced MG conductance, devitellinated oocytes were also tested. Most devitellinated oocytes either showed local damage within a few minutes around the electrodes or were ruptured by the bath perfusion. However, 2 out of 10 oocytes showed no increase in resting conductance after 20 min in the hypotonic solution (data not presented).

Figure 11. Hypotonicity-induced conductance and its I–V relation.

A and B, membrane conductance induced by hypotonicity (63 mosmol l−1, 25 %) in two different oocytes, with A illustrating the lack of response shown by most oocytes and B the response seen in 2 out of 38 oocytes. C and D, I–V relations measured by voltage ramps before, at the peak, and at the end of the conductance induction in A and B. The continuous lines are I–V relations measured at the peak of the conductance. The dashed lines are I–V relations measured before and after exposure to hypotonic solution.

Is the hypertonicity-induced conductance mediated by MG channels?

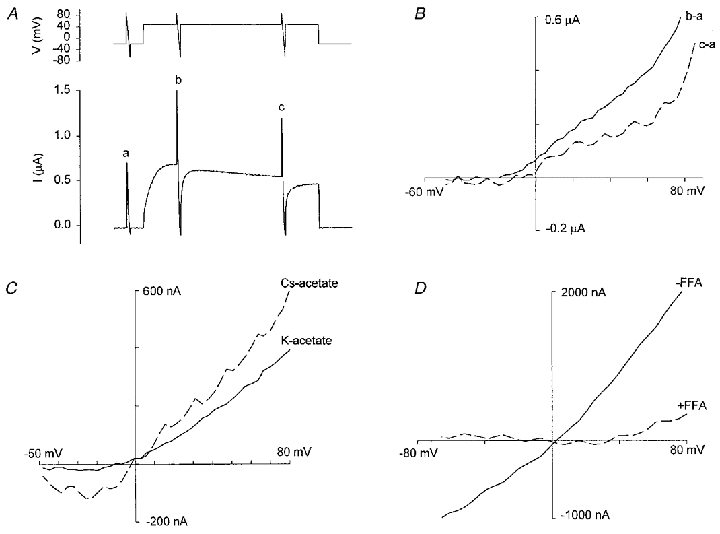

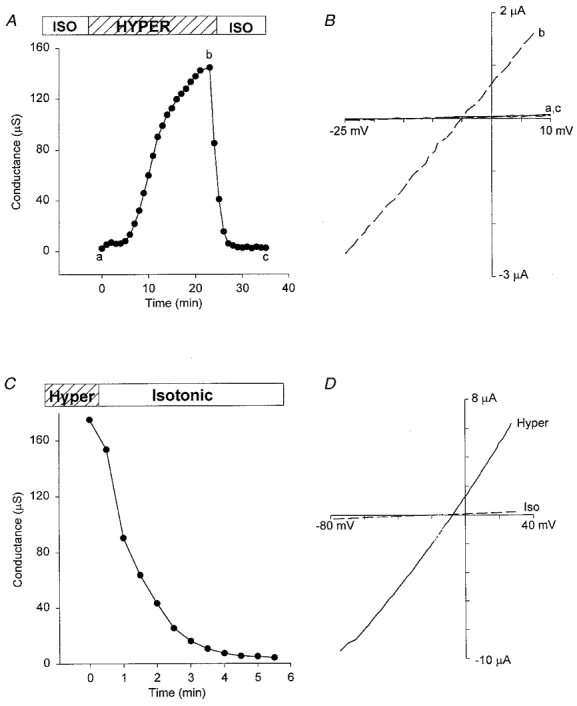

Thirty minutes in a 400 mosmol l−1 hypertonic solution caused visible oocyte shrinkage but failed to activate an increase in membrane conductance in any of the eight oocytes tested. However, when oocytes were bathed in a 480 mosmol l−1 solution, all 54 oocytes tested showed a current (Ishrink) increase. Figure 12A indicates the slow development and recovery of Ishrink in hypertonic solution and return to isotonic solution. To specifically exclude the possibility that Ishrink was a non-specific leak that developed around the electrodes as the oocyte shrunk, five oocytes were pre-incubated for ∼15 min in hypertonic solution before inserting the voltage-clamp electrodes. The average membrane conductance of these five pre-shrunk oocytes was 133 ± 28 μS, which compares with the normal resting conductance of less than 5 μS (Fig. 12C and D). Ion substitution experiments indicate that Ishrink is a non-selective current that shows little discrimination between TBA+ and K+ and is only slightly less permeable to acetate− than Cl− (see Table 3 for details and the permeability for other ions). The Ishrink conductance is also permeable to divalent cations (e.g. Mg2+) but is not blocked by 10 μM Gd3+ (data not presented; see Zhang, 1998).

Figure 12. Hypertonicity-induced conductance.

A, a reversible conductance increase induced by hypertonic (480 mosmol l−1, 200 %) solution for a typical oocyte response. B, I–V relations measured by voltage ramps before, at the peak, and at the end of the conductance increase induced in A. Dashed line is the I–V relation measured at the peak of the conductance (b) and the continuous lines (a,c) are the I–V relations measured before exposure to hypertonic solution and after returning to isotonic solution. C, conductance of a pre-shrunk oocyte that was deactivated by returning to isotonic solution. D, I–V relations of membrane conductance in the pre-shrunk oocyte in hypertonic (continuous lines) and isotonic (dashed lines) solutions. Hypertonic solution contained (mm): 120 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 260 mannitol, 5 Hepes-KOH (pH 7.2). Isotonic solution had the same ionic composition but no mannitol was added.

Table 3.

Reversal potentials of Ishrink in various hypertonic solutions

| Solution (mm) | Erev (mV) |

|---|---|

| 120 KCl | −11.6 ± 1.9 |

| 30 KCl | −13.1 ± 1.9 |

| 120 NaCl | −9.5 ± 3.4 |

| 120 CsCl | −14.3 ± 5.1 |

| 115 TEA-Cl | −22.3 ± 2.3 |

| 120 TBA-Cl | −19.9 ± 2.9 |

| 100 caesium acetate | −13.3 ± 4.5 |

| 120 sodium glutamate | −2.4 ± 2.4 |

Values are means ± s.d. The osmolarity of each solution was adjusted to 500 mosmol l−1 by adding mannitol. CaCl2 (2 mm) was added to KCl, NaCl, CsCl, TEA-Cl and TBA-Cl solutions. Calcium acetate (2 mm) was added to caesium acetate solutions. Hepes-KOH (5 mm) was added to KCl solutions. Free Hepes was added to other solutions. pH for all solutions was 7.2.

DISCUSSION

There were several reasons why we chose the three specific forms of stimuli in our initial attempts to activate whole-oocyte MG conductances. First, patch-clamp studies indicate that MG channels, as well as being mechano-sensitive, are also sensitive to changes in external Ca2+, membrane potential and solution tonicity. Moreover, all three stimuli may be encountered by an oocyte or egg under certain developmental conditions such as during fresh water ovulation and fertilization. On the other hand, the enclosure of the oocyte and the egg in external membranes and cell layers may protect the plasma membrane from external mechanical perturbations. Second, while discrepancies between the mechanosensitive response of the patch and whole cell have been reported (Morris & Horn, 1991), there is general agreement that patch-clamp recordings of voltage- and ligand-sensitive conductances can accurately predict the whole-cell response of oocytes (Methfessel et al. 1986) and other cells (Hille, 1992). Nevertheless, we have found major discrepancies between the experimentally observed oocyte conductances and those anticipated from patch-clamp studies

Although external Ca2+ causes significant block of single MG channels (Taglietti & Toselli, 1988; Yang & Sachs, 1989), the large Ca2+-masked conductance recorded in the whole oocyte displays a different ion selectivity, pharmacology and sensitivity to Cx-38 antisense oligonucleotides compared with MG channels and is most probably mediated by hemi-gap channels. We believe the low probability of observing single hemi-gap channels in oocyte patches reflects the overall low membrane density of this endogenous channel (e.g. see Trexler et al. 1996). Our occasional recordings (i.e. < 1 in 50 patches) of putative hemi-gap channels indicate a channel of ∼200 pS with long open times and no stretch activation (O. P. Hamill, unpublished observations). In these recordings, MG and hemi-gap channels currents appear to be independent with no evidence of interconversion between the two channels. Furthermore, the observation that MG channel activity is insensitive to Cx-38 antisense oligonucleotides would also seem to exclude any post-translational conversion between the two channels. We therefore consider it unlikely that mechanical stimulation changes the ion selectivity and pharmacology of the MG channel as has been reported for the amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel (Achard et al. 1996).

Regarding spontaneous single MG channel openings, different laboratories report different levels of MG channel activity (Methfessel et al. 1986; Hamill & McBride, 1992; Silberberg & Magleby, 1997; Reifarth et al. 1999). In our own studies, we observe low frequency MG channel openings in some patches at the resting potential (Po < 0.01 at −50 mV). However, a number of factors may contribute to this apparent spontaneous activity. For example, capillary and hydrostatic pressures exerted by the pipette solution may stress the patch in addition to experimentally applied pressures. In principle, one can use the lack of visible particulate movement at the pipette tip to set the true zero pressure before sealing (see Sokabe & Sachs, 1990) but then sealing becomes problematic. Another factor may be related to the forces that seal the membrane to the pipette glass, which may exert a significant tension on the bilayer (Sokabe & Sachs, 1990; Sokabe et al. 1997). However, whatever the factors that create spontaneous MG channel activity in the patch, they apparently do not exert their effect on the MG channels in oocyte membrane to cause significant contribution to the resting oocyte conductance.

In order to identify possible voltage-activated conductances mediated by MG channel activity, it was necessary to identify ionic conditions that would selectively block the contributions of other voltage-sensitive conductances. In the case of depolarization, potassium acetate was used to minimize the contributions of Ic, and Na+- and Cl− currents. Under these ionic conditions, a residual non-selective conductance, Ir, was identified, which displayed variable rectification properties, possibly reflecting several conductance components. Ir was blocked by Cd2+, Gd3+ and most significantly, by FFA. Specifically, in potassium acetate solution with 100 μM FFA present, the residual conductance was basically abolished. Therefore, since FFA does not block MG channels, if there is any depolarization-activated whole-cell MG channel current, it must be much smaller (i.e. < 50 nA) than that predicted from patch studies (i.e. > 3 μA, see Table 1).

As with the spontaneous MG channel activity, different laboratories report different levels of depolarized-induced single MG channel activity. For example, Silberberg & Magleby (1997) reported that prolonged depolarization to +50 mV consistently and fully activated MG channels in excised and cell-attached patches. However, in a more recent report, the same depolarizing protocol was found ineffective if soft glass rather than borosilicate glass pipettes were used (Gil et al. 1999). On this basis, it was concluded that membrane-glass interactions underlie the voltage activation of MG channels (Gil et al. 1999). However, our observations on over 200 patches, using identical solutions to the above study and borosilicate glass pipettes, indicate that the large majority of patches (95 %) show no depolarization-induced activation, even when the depolarization to +50 mV was maintained for 15 min. Instead, a few patches showed long bursts of MG channel openings during prolonged depolarization (O. P. Hamill, unpublished observations). A possible patch phenomenon that may contribute to this sporadic activation is depolarization-induced membrane patch movements. Specifically, prolonged depolarization (∼5 min) causes the patch to flex inward towards the cell, as if positive pressure was being applied. However, this depolarization-induced patch curvature does not consistently promote MG channel activation. On more rare occasions, depolarized patches also exhibit additional repetitive contractile motions (O. P. Hamill, unpublished observations; see also Sokabe & Sachs, 1990) which may underlie the observed bursts or cooperative MG channel openings. The mechanisms that underlie such patch movements are unknown. They may specifically arise because constraints placed on the membrane patch by tight seal formation make it hypersensitive to electro-curvature effects and any contractile forces generated within the cytoskeleton.

The hyperpolarization-activated current, Ih, has properties different from single MG channel activity in terms of its kinetics, ion selectivity and pharmacology. Furthermore, hyperpolarization never fully activates all the MG channels in the patch (Po increases to 0.01 or less) and upon depolarization the channels deactivate immediately (Hamill & McBride, 1996b; Silberberg & Magleby, 1997). Therefore, while the predicted whole-cell current may be several hundred nanoamps at −150 mV (Table 1), Ih continues to develop without saturation to values > 10 μA (Fig. 12). It may be that Ih reflects an electrically induced reversible formation of large diameter pores in the plasma membrane. Similar ‘breakdown pores’ also occur in strongly hyperpolarized patches (∼-200 mV) and appear as noisy, variable-amplitude currents that mask the much lower MG channel activity and only turn off slowly (i.e. over several minutes) with patch depolarization (O. P. Hamill, unpublished observations).

Our inability to detect a hypotonicity-activated conductance in most oocytes is consistent with previous reports that found no increased cation conductance and only observed a hypotonicity-activated Cl− conductance in oocytes not treated with collagenase (Ackerman et al. 1994; Arellano et al. 1995). It may be that the immediate plasma membrane reserves of the oocyte, in the form of microvilli and extensive membrane folds, prevent the development of bilayer tension to activate MG channels, even when oocytes are swollen to nearly twice their diameter. Indeed, membrane area estimates based on capacitance measurements indicate an excess membrane area at least 5 times larger than that predicted for a smooth sphere (Zhang & Hamill, 2000). In this case, the oocyte would need to be inflated to more than twice its diameter, and over 10 times its volume, in order smooth out the excess surface membrane (Zhang & Hamill, 2000). However, such large volume increases cannot be experimentally achieved (either by osmotic or direct inflation of devitellinated oocytes) before visibly damaging the voltage-clamped oocyte. Furthermore, if MG channels are localized on microvilli that are preserved during oocyte swelling, then their small radius of curvature (i.e. < 0.1 μm; see Zampighi et al. 1995) would prevent MG channel activation (according to Laplace's Law considerations), even when the oocyte was swollen to over twice its normal diameter (see Zhang & Hamill, 2000).

We have not tested whether hypotonicity activates single MG channel activity in cell-attached patches of Xenopus oocytes but such activation has been reported in vesicles excised from the oocyte during patch recording (Schutt & Sackin, 1997). In this case, MG activation may occur because the excess plasma membrane area has been smoothed out in the process of patch and vesicle formation (Zhang & Hamill, 2000; Zhang et al. 2000).

The current activated by hypertonicity, Ishrink, appears to be mediated by a relatively large diameter pore that allows TBA+ and acetate− permeation and is not blocked by Gd3+. It therefore differs from the hypertonicity-activated conductance reported in cortical collecting duct cells that is cation selective, impermeable to large organic cations, and blocked by FFA and Gd3+ (Volk et al. 1995). Our observation in the next study that Ishrink can be reversed by oocyte inflation (Zhang & Hamill, 2000) indicates a mechanical mechanism may be involved in the activation and deactivation of this conductance.

Comparison of Ic, Ir, Ih and Ishrink

A side-by-side comparison of the whole-cell MG channel currents predicted from patch data and those experimentally observed is presented in Table 4. Ic is clearly different from Ishrink and Ih in its ion selectivity and Gd3+ sensitivity. The ion selectivity and rectification of Ir distinguish it from Ic. The Gd3+ sensitivity of Ir distinguish it from Ih and Ishrink, although they are all poorly selective with nearly equal permeability to cations and anions. The block of Ir by FFA distinguishes it from MG channels. Ih and Ishrink are similar in that both are non-selective and permeable to large cations such as TBA+ and large anions such as glutamate and are not blocked by 100 μM Gd3+. However, one difference between Ishrink and Ih is that Ishrink is sensitive to cell inflation but Ih is not (Zhang & Hamill, 2000). Our results at present cannot distinguish whether Ih and Ishrink are independent or somehow related. However, we conclude that MG channels mediate none of the conductances. In the next study, we examine the mechanosensitivity of the oocyte and the various conductances described in Table 4. In addition, specific mechanisms that may underlie the discrepancy between patch and whole-cell recordings are tested (Zhang & Hamill, 2000).

Table 4.

Comparison of the properties of predicted whole-cell MG channel current and recorded whole-cell currents

| Current | PCl/PK | Gd2+ block | Rectification | PTBA/PK | Sensitivity to cell inflation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG current | 0 | Yes | Strongly outward (ramp) | 0.05 | Increase |

| Ic | 0.24 | Yes | No (instantaneous) | 0.2 | Slight reduction |

| Ir | ∼1 | Yes | Strongly outward (ramp) | — | No |

| Ih | ∼1 | No | No (ramp) | ∼0.3 | No |

| Ishrink | ∼1 | No | No (ramp) | ∼1 | Significant reduction |

Rectification was judged by I–V relations measured either by voltage ramp (ramp) or steps (instantaneous).

Acknowledgments

Our research is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Grant R01-AR42782 and the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

References

- Achard J-M, Bubien JK, Benos DJ, Warnock DG. Stretch modulates amiloride sensitivity and cation selectivity of sodium channels in human B-lymphocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270:C224–234. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.1.C224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman MJ, Wickman KD, Clapham DE. Hypotonicity activates a native chloride current in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;103:153–179. doi: 10.1085/jgp.103.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano RO, Miledi R. Functional role of follicular cells in the generation of osmolarity-dependent Cl− currents in Xenopus follicles. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;488:351–357. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano RO, Woodward RM, Miledi R. A monovalent cation conductance that is blocked by extracellular divalent cations in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;484:393–604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barish ME. A transient calcium-dependent chloride current in the immature Xenopus oocyte. The Journal of Physiology. 1983;342:309–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard EA, Miledi R, Sumikawa K. Translation of exogenous messenger RNA coding for nicotinic acetylcholine receptor produces functional receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Proceedings of the Royal Society. 1982;B 215:241–246. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1982.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baud C, Kado RT, Marcher K. Sodium channels induced by depolarization of the Xenopus laevis oocyte. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1982;79:3188–3192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluemink JG, Hage WJ, van den Hoef MH, Dictus WJ. Freeze-fracture electron microscopy of membrane changes in progesterone-induced maturing oocytes and eggs of Xenopus laevis. European Journal of Cell Biology. 1983;31:85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara L. Xenopus connexin38 forms hemi-gap-junctional channels in the nonjunctional plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:742–748. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79273-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil Z, Magleby KL, Silberberg SD. Membrane-pipette interactions underlie delayed voltage activation of mechanosensitive channels in Xenopus oocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:3118–3127. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77463-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Hernandez J-M, Stuhmer W, Parekh AB. Calcium dependence and distribution of calcium-activated chloride currents in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;502:569–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.569bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP. Potassium and chloride channels in red blood cells. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-channel Recording. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 451–471. [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr Rapid adaptation of single mechanosensitive channels in Xenopus oocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:7462–7466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr . Pressure/patch-clamp techniques. In: Boulton A, Baker G, Walz W, editors. Neuromethods, Patch-clamp Applications and Protocols. Vol. 26. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press; 1995. pp. 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr The pharmacology of mechanogated membrane ion channels. Pharmacological Reviews. 1996a;48:231–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr Membrane voltage and tension interactions in the gating of the mechano-gated cation channel in Xenopus oocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1996b;70:A348–A348. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr Induced membrane hypo/hyper-mechanosensitivity: A limitation of patch-clamp recording. Annual Review of Physiology. 1997;59:621–631. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kowdley GC, Ackerman SJ, John JE, III, Jones LR, Moorman JR. Hyperpolarization-activated chloride currents in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;103:217–230. doi: 10.1085/jgp.103.2.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JW, McBride DW, Jr, Hamill OP. Amiloride block of the mechanosensitive cation channel in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;441:347–366. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JW, McBride DW, Jr, Hamill OP. Structure-activity relations of amiloride and its analogues in blocking the mechanosensitive channels in Xenopus oocytes. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;106:283–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JW, McBride DW, Jr, Hamill OP. Ionic effects on amiloride block by the mechanosensitive channel in Xenopus oocytes. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;108:116–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride DW, Jr, Hamill OP. Pressure-clamp: a method for rapid step perturbation of mechanosensitive channels. Pflügers Archiv. 1992;421:606–612. doi: 10.1007/BF00375058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methfessel C, Witzemann V, Takahashi T, Mishina M, Numa S, Sakmann B. Patch clamp measurements on Xenopus laevis oocytes: currents through endogenous channels and implanted acetylcholine receptor and sodium channels. Pflügers Archiv. 1986;407:577–588. doi: 10.1007/BF00582635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CE, Horn R. Failure to elicit neuronal macroscopic mechanosensitive currents anticipated by single-channel studies. Science. 1991;251:1246–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.1706535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker I, Ivorra I. A slowly inactivating potassium current in native oocytes of Xenopus laevis. Proceedings of the Royal Society. 1990;B 238:369–381. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1990.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker I, Miledi R. A calcium independent chloride current activated by hyperpolarization in Xenopus oocytes. Proceedings of the Royal Society. 1988;B 233:191–199. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1988.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifarth FW, Clauss W, Weber W-M. Stretch-independent activation of the mechanosensitive cation channel in oocytes of Xenopus laevis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1999;1417:63–76. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackin H. Mechanosensitive channels. Annual Review of Physiology. 1995;57:333–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakmann B, Neher E. Geometric parameters of pipettes and membrane patches. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-channel Recording. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Schutt W, Sackin H. A new technique for evaluating volume sensitivity of ion channels. Pflügers Archiv. 1997;433:368–375. doi: 10.1007/s004240050290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg SD, Magleby KL. Voltage-induced slow activation and deactivation of mechanosensitive channels in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;505:551–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.551ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokabe M, Naruse K, Nunogaki K. Mechanosensitive ion channels: Single channel vs. whole cell activities. Progress in Cell Research. 1997;6:139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Sokabe M, Sachs F. The structure and dynamics of patch clamped membrane: A study using differential interference contrast microscopy. Journal of Cell Biology. 1990;111:599–606. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen I, Bates WR, Morris CE. Embryogenesis in the presence of blockers of mechanosensitive ion channels. Development Growth and Differentiation. 1991;33:437–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1991.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhmer W, Parekh AB. Electrophysiological recordings from Xenopus oocytes. In: Neher E, Sakmann B, editors. Single-channel Recording. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 341–356. [Google Scholar]

- Taglietti V, Toselli M. A study of stretch-activated channels in the membrane of frog oocytes: interactions with Ca2+ ions. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;407:311–328. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokimasa T, North RA. Effects of barium, lanthanum and gadolinium on endogenous chloride and potassium currents in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:677–686. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trexler RB, Bennet MVL, Bargiello TA, Verselis VK. Voltage gating and permeation of a gap junction hemichannel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:5836–5841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk T, Fromter E, Korbmacher C. Hypertonicity activates nonselective cation channels in mouse cortical collecting duct cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:8478–8482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson NC, Gao F, Hamill OP. Effects of mechanogated channel blockers on oocyte growth, fertilization and embryogenesis. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1998;165:161–174. doi: 10.1007/s002329900430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, McBride DW, Jr, Hamill OP. Mg2+ block and inward rectification of mechanosensitive channels in Xenopus oocytes. Pflügers Archiv. 1998;435:572–574. doi: 10.1007/s004240050554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XC, Sachs F. Block of stretch-activated ion channels in Xenopus oocytes by gadolinium and calcium ions. Science. 1989;243:1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.2466333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XC, Sachs F. Characterization of stretch-activated ion channels in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;431:103–122. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampighi GA, Kreman M, Boorer KJ, Loo DDF, Bezanilla F, Chandy G, Hall JE, Wright EM. A method for determining the unitary functional capacity of cloned channels and transporters expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1995;148:65–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00234157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. TX, USA: University of Texas Medical Branch; 1998. Membrane patch and whole cell response of Xenopus oocytes to mechanical, electrical and osmotic stimulation. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Gao F, Popov VL, Wen JW, Hamill OP. Mechanically gated channel activity in cytoskeleton-deficient plasma membrane blebs and vesicles from Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 2000;523:117–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Hamill OP. On the discrepancy between whole-cell and membrane patch mechanosensitivity in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 2000;523:101–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, McBride DW, Jr, Hamill OP. The ion selectivity of a membrane conductance inactivated by extracellular calcium in Xenopus oocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:763–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.763bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]