Abstract

Using an in vitro single unit recording technique we studied the changes in mechanical and chemical sensitivity of vagal afferent fibres in acute oesophagitis, with particular attention to inflammatory products such as purines.

Histologically verified oesophagitis was induced by oesophageal perfusion of 1 mg ml−1 pepsin in 150 mM HCl in anaesthetized ferrets for 30 min on two consecutive days. Controls were infused with 154 mM NaCl.

The number of action potentials evoked in oesophageal mucosal afferents by mucosal stroking with calibrated von Frey hairs (10–1000 mg) was stimulus dependent. In oesophagitis responsiveness was reduced across the range of stimuli compared with controls.

Topical application of the P2X purinoceptor agonist αβ-methylene ATP had no direct excitatory effect on afferents. In oesophagitis, but not in controls, there was a significant increase in responses to stroking with von Frey hairs during superfusion with αβ-methylene ATP (1 μM).

Mucosal afferents responded directly to one or more chemical stimuli: 26 % (5/19 afferents) responded in controls, and 47 % (7/15 afferents) in oesophagitis. There were no differences in responsiveness to bradykinin (1 μM), prostaglandin E2 (100 μM), 5-hydroxytryptamine (100 μM), capsaicin (1 mM) or hydrochloric acid (150 mM) between control and oesophagitis groups.

We conclude that a sensitizing effect of a P2X purinoceptor agonist on mechanosensory function is induced in oesophagitis. This effect is offset by a decrease in basal mechanosensitivity.

One of the major consequences of tissue injury and the resultant cell damage is the release of cytoplasmic contents rich in adenosine triphosphate (ATP). A number of other processes are initiated that lead to inflammation, including local production of bradykinin and prostaglandins, mast cell degranulation and localized acidosis. There is evidence to support a role for the products of inflammatory processes (including purines, bradykinin, prostaglandins, 5-hydroxytryptamine, and low pH) in activation or sensitization of primary afferent endings (Rang et al. 1994), giving rise to sensations and reflex effector responses. Recent evidence indicates that specific subtypes of purinergic and bradykinin receptors are present on afferent neurones (Sengupta et al. 1992; Chen et al. 1995; Cook et al. 1997) including vagal afferents (Khakh et al. 1995), and that purines may be responsible for the sensitization of endings to other stimuli (Sawynok & Reid, 1997; Kress & Guenther, 1999).

One of the most common manifestations of inflammation is in oesophagitis, which occurs following repeated gastro-oesophageal reflux, whereby hydrochloric acid and pepsin secreted by the stomach during digestion come into contact with the oesophageal mucosa. This is pathological when it becomes symptomatic or complications develop, constituting gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (Dent, 1998). Sensation induced by the presence of acid in the oesophagus, which is signalled by mucosal afferents (Harding & Titchen, 1975; Clerc & Mei, 1983; Page & Blackshaw, 1998), is increased in reflux disease, whereas sensation of oesophageal distension, which is mediated by tension-sensitive afferents (Clerc & Mei, 1983; Sengupta et al. 1989; Page & Blackshaw, 1998), is unchanged (Fass et al. 1998).

Using a recently established in vitro electrophysiological approach (Page & Blackshaw, 1998; Lynn & Blackshaw, 1999), we have developed the capability to precisely categorize gastrointestinal afferents into functional subtypes based on mechanosensitivity. These are: mucosal receptors that respond to mucosal stroking but not tension applied across the preparation; tension receptors that respond only to tension; and tension/mucosal receptors that respond to both types of stimulus (Page & Blackshaw, 1998, 1999). This approach has allowed not only detailed investigation of fine tactile sensitivity and chemosensitivity of mucosal afferents, but also changes in sensitivity that may be induced pharmacologically (Page & Blackshaw, 1999). In this study we aimed to characterize the changes in mechano- and chemosensitivity in the subtype of afferent most likely to be influenced by mucosal inflammation by virtue of the location of their receptive fields – oesophageal mucosal vagal afferents. This was performed in an established model of acute oesophagitis (Smid et al. 1998), with particular emphasis on the effects of inflammatory products.

METHODS

All studies were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Ethics Committees of the Royal Adelaide Hospital and Institute for Medical and Veterinary Sciences, Adelaide.

Oesophagitis model

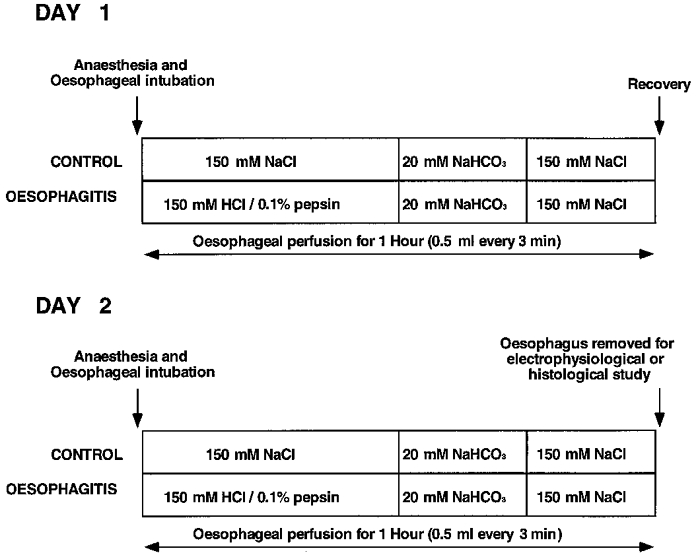

Ferrets (n = 66) were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (50 mg kg−1i.p.) and treated with atropine (50 μg kg−1i.p.) to inhibit salivary secretion and therefore minimize aspiration into the airway during recovery. The animals were intubated with a tracheal cannula to prevent aspiration into the airways during the oesophageal perfusion. A multi-lumen polyethylene infusion assembly was then inserted into the oesophagus through the mouth. The perfusion side hole was located 2.5 cm above the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) as estimated from an average length of 20 cm from LOS to incisors in ferrets of similar body weight in previous studies in our laboratory. A separate drainage tube was also inserted into the lumen of the oesophagus so that the drainage side hole was 5 cm above the LOS. The protocols for induction of oesophagitis are illustrated in Fig. 1. In 29 ferrets an initial 1.5 ml of acid-pepsin mixture (1 mg pepsin-1 ml 150 mM HCl) were infused into the oesophagus followed by 0.5 ml every 3 min for 30 min. This was followed by an infusion of sodium bicarbonate (20 mM, 3.5 ml in 15 min) to neutralize the acid and finally saline (3.5 ml in 15 min). The animals were then allowed to recover under close observation and the procedure was repeated 23 h later. In 37 control animals saline was perfused instead of the acid-pepsin solution. After two days of either treatment the ferrets were exsanguinated while still under deep anaesthesia. Body weights of ferrets undergoing control or oesophagitis protocols were similar (586 ± 28 g; n = 37 vs. 586 ± 19 g; n = 29, respectively).

Figure 1. Protocols.

Diagrammatic representation of the protocols followed for induction of acute oesophagitis or for control treatment. The procedures were carried out under general anaesthetic and were undertaken on consecutive days as shown.

Histological studies

Segments of oesophagus (1, 3, 5, 7 and 10 cm from the LOS) were taken from three control and five acid-pepsin-treated animals for histological examination. These animals are additional to those used for electrophysiological studies. Tissue samples were fixed in 10 % formalin and processed into paraffin wax. Transverse sections were cut (4 μm) and stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

Electrophysiological setup

The oesophagus and attached vagal nerves, heart and lungs were removed and placed in a modified Krebs solution of the following composition (mM): NaCl, 118.1; KCl, 4.7; NaHCO3, 25.1; Na2PO4, 1.3; MgCl, 1.2; CaCl2, 1.5; citric acid, 1.0; glucose, 11.1; bubbled with 95 % O2-5 % CO2. The heart, lungs and blood vessels were removed and the vagus nerve cleared of connective tissue. The preparation (7–8 cm long) was opened longitudinally along the oesophagus and pinned out flat, mucosa side up, in a perspex chamber (dimensions 13.0 × 4.0 × 1.0 cm) and perfused at a rate of 11–12 ml min−1 with Krebs solution maintained at 34°C. The vagus nerve (free length 3.0 cm) was drawn through a small hole into an isolated recording chamber (dimensions 5.0 × 5.0 × 1.0 cm) where it was bathed in paraffin oil. Under a dissecting microscope a small longitudinal incision was made in the nerve sheath. Using fine forceps nerve fibres were teased back onto a platinum recording electrode.

Characterization of oesophageal vagal afferent properties

Location of receptive fields was determined by mechanical stimulation throughout the preparation with a brush, then more accurately with a blunt glass rod. Mechanical thresholds and receptive field size were determined using calibrated von Frey hairs. Responses to tension applied across the preparation were tested for each receptive field to confirm that afferents had receptive fields only in the mucosa, and not in the muscle layer (see Page & Blackshaw, 1998). Mucosal receptors showed rapidly adapting responses to maintained pressure on the receptive field with a von Frey hair. The most reproducible, stimulus-dependent, and probably physiological responses of these afferents to mucosal stimuli were evoked when the probe was moved at a rate of 5 mm s−1 across the receptive field, rather than being static. As the receptive fields of these afferents were found to be small (1–3 mm2), a single test at each intensity would tend to miss the centre of the receptive field. Therefore we minimised experimenter error by measuring the mean response to the middle eight of ten standard strokes given at 1 s intervals. As the von Frey hair was bent evenly throughout the stroking stimulus, the receptive field was subjected to an even force as the hair passed over it.

In later studies, conduction velocity of vagal afferent fibres was calculated from the time and distance between stimulating (1 Hz, 20 V, 0.1 ms duration) and recording electrodes. Both C fibres (conduction velocity below 2.0 m s −1) and Aδ fibres (conduction velocity between 2 and 25 m s−1) were found. Aβ fibres were not encountered. Numbers of afferents whose conduction velocites were tested is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic properties of oesophageal afferents in control and oesophagitis tissue

| Control | Oesophagitis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous activity (impulses s−1) | Overall | 0.51 ± 0.27 | (n = 32) | 0.78 ± 0.44 | (n = 26) | n. s |

| C fibres | 0.43 ± 0.27 | (n = 9) | — | — | ||

| Aδ fibres | 0.72 ± 0.29 | (n = 17) | 0.41 ± 0.27 | (n = 8) | n.s. | |

| Size of receptive field (mm2) | Overall | 2.25 ± 0.15 | (n = 18) | 2.80 ± 0.20 | (n = 15) | n. s. |

| C fibres | 1.83 ± 0.17 | (n = 6) | — | — | ||

| Aδ fibres | 2.35 ± 0.21 | (n = 12) | 2.90 ± 0.51 | (n = 5) | n.s. | |

| Conduction velocity (m s−1) | Overall | 6.80 ± 0.98 | (n = 29) | 6.66 ± 0.77 | (n = 8) | n.s. |

| C fibres | 0.97 ± 0.15 | (n = 9) | — | — | ||

| Aδ fibres | 9.63 ± 0.91 | (n = 20) | 6.66 ± 0.77 | (n = 8) | n.s. | |

No significant differences occurred (n. s., using unpaired t test or Kruskal-Wallis test in the case of overall conduction velocity). Properties were not determined for all afferent fibres and therefore numbers vary between groups.

Subject to maintenance of recordings throughout experiments, the chemosensitivity of mucosal fibres was examined by applying solutions directly onto the receptive field. Agents were applied for periods of up to 7 min by means of a small cylindrical chamber (1 cm diameter) placed over the receptive field. The following were tested: αβ-methylene ATP (100 μM), hydrochloric acid (150 mM; HCl), 5-hydroxytryptamine (100 μM; 5-HT), bradykinin (1 μM), prostaglandin E2 (100 μM; PGE2), and capsaicin (1 mM). Table 2 shows the numbers of fibres tested with each stimulus. In all experiments the mechanical sensitivity of receptive fields was checked between each drug application to ensure continued viability of the unit under investigation. Capsaicin was administered last due to the desensitization often associated with this stimulus.

Table 2.

Chemosensitivity of oesophageal afferents in control and oesophagitis tissue to individual stimuli applied directly into a ring around the receptive field

| Control | Oesophagitis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bradykinin (1 μm) | 0/17 | 3/15 | n.s. |

| Prostaglandin E2 (100 μm) | 2/17 | 3/14 | n.s. |

| 5-Hydroxytryptamine (100 μm) | 1/14 | 3/14 | n.s. |

| Capsaicin (1 mm) | 4/15 | 1/14 | n.s. |

| Hydrochloric acid (150 mm) | 0/14 | 1/11 | n.s. |

| αβ-MeATP (100 μm) | 0/3 | 0/3 | n.s. |

Fractions indicate number of fibres responding/number tested. No significant differences (n.s.) were seen when compared using a Fisher's exact test.

In 12 specifically designed experiments, after responses to the full range of von Frey hairs had been determined, the effect of the P2X purinoceptor agonist αβ-methylene ATP (αβ-meATP; 1 μM) on mechanical sensitivity was determined. These experiments were undertaken also with a view to investigating non-desensitizing P2X purinoceptors (Lewis et al. 1995). αβ-meATP (1 μM) was added to the superfusing Krebs solution and allowed to equilibrate for 20 min after which the stroke-response curves were re-determined. This equilibration period was observed so as to ensure penetration of the drug into all layers of the tissue. The drug was then washed out of the perfusate and, after 20 min, stroke-response curves were re-determined.

Data recording and analysis

Neural recordings were amplified with a biological amplifier (BA.1; JRAK, Melbourne. Australia) and scaling amplifier (SA.1; JRAK), filtered (F.1; JRAK) and monitored using an oscilloscope (DL1200A; Yokogawa, Japan). Single units were discriminated on the basis of action potential shape, duration and amplitude on-line using a JRAK window discriminator (WD1) and also off-line using Spike II software (Cambridge Electronic Design Limited, Cambridge, England). All data were recorded on magnetic tape and analysed off-line using a personal computer (Power Macintosh 7300/200). Peristimulus-time histograms and discharge traces were displayed using Spike II software.

Data are quoted as means ± standard error of the mean, with n = number of animals. Differences in conduction velocities between afferent fibres studied with each protocol were assessed using a Kruskal-Wallis test, as these differences were not normally distributed. Differences between stimulus-response curves were evaluated using two-way analysis of variance. Differences between receptive field sizes were assessed using an Student's unpaired t test, as were differences in spontaneous activity. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. A response to a chemical stimulus was scored when a maintained 10 % increase in discharge frequency occurred above a steady baseline. This criterion did not need to be applied because all responses to chemicals showed greater than 50 % increases. To test for differences in proportions of afferents, for example of those responding to chemical stimuli in different groups, Fisher's exact test was used.

Drugs

Stock solutions of all drugs were kept frozen and diluted to their final concentration in Krebs solution on the day of the experiment. αβ-Methylene ATP, capsaicin, bradykinin, 5-hydroxytryptamine creatinine sulphate, pepsin and prostaglandin E2 were all obtained from Sigma (Sydney, Australia).

RESULTS

Histology

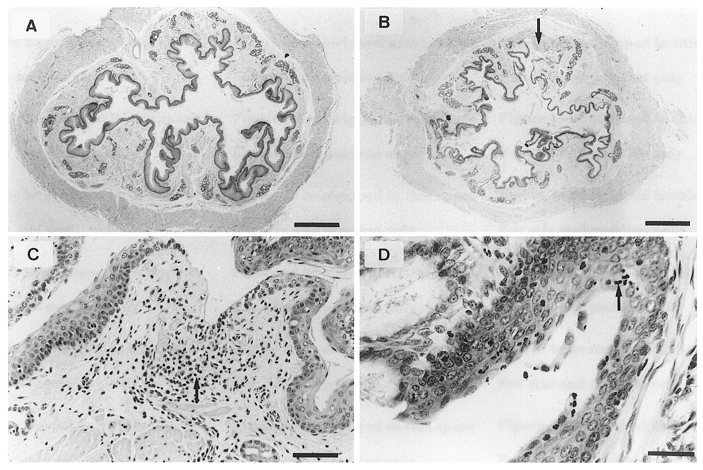

Histological examination of distal oesophageal sections from acid-pepsin-treated ferrets revealed features characteristic of acute clinical oesophagitis, illustrated in Fig. 2, including uneven thinning of the epithelium, shedding of damaged cells, and discrete ulcerations (Fig. 2B–D). There was also damage to mucous glands and ducts (not shown). Discrete lesions were associated with accumulation of mixed inflammatory cells, including eosinophils (Fig. 2D). These features were observed from immediately above the lower oesophageal sphincter to 70 mm proximal. Distal oesophageal sections from saline-infused controls showed normal histology (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Distal oesophageal tissue.

Haematoxylin and eosin-stained transverse sections of distal oesophageal tissue from saline-perfused control (A) and acid-pepsin treated ferrets (B–D). B, complete shedding around a focal lesion (arrow) and areas of denuded epithelium (A and B: bar = 1 mm). C, higher magnification of lesion, with evidence of inflammatory cell infiltration (arrow) and basal cell hyperplasia (bar = 100 μm). D, inflammatory cell accumulation (arrow; bar = 50 μm).

Electrophysiology

Distribution of receptive fields

The distribution of mucosal afferents recorded in controls and oesophagitis was random. In the control group the receptive fields were found proximal as well as distal to the point of vagal dissection, showing that afferents course up, as well as down the oesophagus before exiting, as we have observed previously (Page & Blackshaw, 1998). In acid-pepsin treated oesophagi the receptive fields were found either level with or distal to the point of vagal dissection, and all were in areas that showed macroscopic evidence of oesophagitis consistent with that observed in histological studies. No specific properties were associated with receptive fields occurring on or near discrete ulcerations. There was no significant difference in the size of individual mechanoreceptive fields between controls and oesophagitis (Table 1).

Spontaneous firing and conduction velocity

In controls and oesophagitis, mucosal afferents usually showed little or no resting activity. When there was spontaneous resting activity it had no apparent rhythm. There was no significant difference in spontaneous activity between the two groups (Table 1). Conduction velocity was measured in 29/37 fibres recorded in control preparations, and 8/29 fibres in oesophagitis. Nine fibres in controls had conduction velocities in the C fibre range, and 20 were in the Aδ fibre range. All eight fibres recorded in oesophagitis were Aδ fibres. The proportion in each range was not significantly altered by inflammation (P = 0.16, Fisher's exact test).

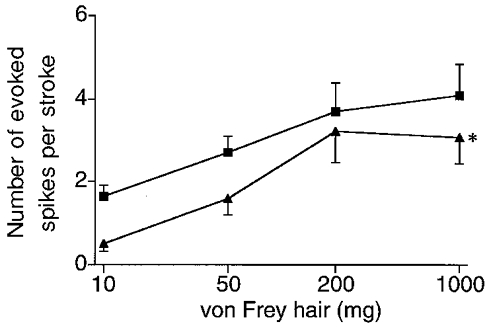

Mechanical sensitivity

As previously reported (Page & Blackshaw, 1998, 1999), oesophageal mucosal afferents did not respond to tension applied across the receptive field, but showed consistent responses to stroking with calibrated von Frey hairs. Stimulus-response functions in controls and oesophagitis are shown in Fig. 3. In oesophagitis there was a significant reduction in the number of action potentials evoked by stroking throughout the range of stimulus intensities (P < 0.05 vs. control, two-way ANOVA). This result was significant also when only Aδ fibres in each group were compared (P < 0.05, data not shown). Most afferents had von Frey thresholds below 10 mg (23/26 tested in oesophagitis and 29/32 tested in controls). The remainder had thresholds below 50 mg. There was no significant difference in these proportions between the two groups. No relationship was observed between mechanical sensitivity and conduction velocity. Due to difficulties experienced in penetrating the surface tension of the superfusate with thinner hairs, thresholds below 10 mg could not be investigated.

Figure 3. Stimulus-response functions of mucosal afferents.

Controls (▪; n = 32) and oesophagitis (▴; n = 26). The afferents recorded in oesophagitis showed significantly smaller numbers of evoked spikes per stroke than afferents in controls (two-way ANOVA, * P < 0.05).

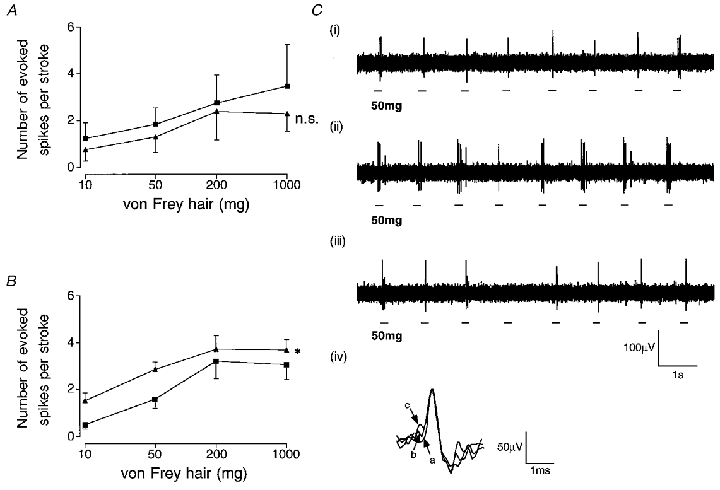

Chemical modulation of mechanical sensitivity

In order to evaluate changes in sensitivity to purinergic receptor agonists that may occur in oesophagitis, in early studies both ATP and the selective P2X receptor agonist αβ-methylene ATP were applied into a ring around the receptive field in the concentration range 10−6 to 10−3 M. Neither had any direct effect on afferent firing, but in early experiments on inflamed tissue it was noted that mechanical sensitivity was enhanced, particularly after application of αβ-methylene ATP. This was therefore repeated with a concentration of 10−6 M in the superfusate in subsequent experiments, which consistently increased responses to mucosal stroking throughout the range of stimuli (Fig. 4). Enhancement of mechanosensitivity was reversed after wash out of the agonist. In similar experiments on non-inflamed tissue from controls, no effect of αβ-methylene ATP on mechanosensitivity occurred (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Response of oesophageal mucosal afferents to mucosal stroking.

Stimulus-response functions before (▪) and after (▴) exposure to the P2X receptor agonist αβ-methylene ATP in controls (A; n = 4, all A fibres) and oesophagitis (B; n = 8, all A fibres). Asterisk in B indicates that αβ-meATP significantly enhances the response to mucosal stroking in oesophagitis (two-way ANOVA, *P < 0.05). C, original recording of a mucosal afferent response to mucosal stroking with a 50 mg von Frey hair in oesophagitis in normal Krebs solution (i), 20 min after perfusion of αβ-methylene ATP (1 μM) (ii), and 20 min after reintroduction of normal Krebs solution (iii). Inset (iv) shows superimposed action potentials on a fast time base recorded at each stage described above (a-i, b-ii, c-iii), indicating that recordings were from the same single unit.

Following exposure of receptive fields to ring application of bradykinin (1 μM), prostaglandin E2 (100 μM), 5-hydroxytryptamine (100 μM), capsaicin (1 mM) or hydrochloric acid (150 mM), no increases in sensitivity to mucosal stroking were seen (data not shown) as previously reported (Page & Blackshaw, 1998), although this was not tested systematically. Capsaicin caused desensitization of responses to itself and to mechanical stimulation – also as previously reported (Page & Blackshaw, 1998). Due to the absence of mechanical sensitization after ring application of high concentrations of the above agents, further detailed characterization of mechanosensitivity after exposure by bath superfusion was not carried out.

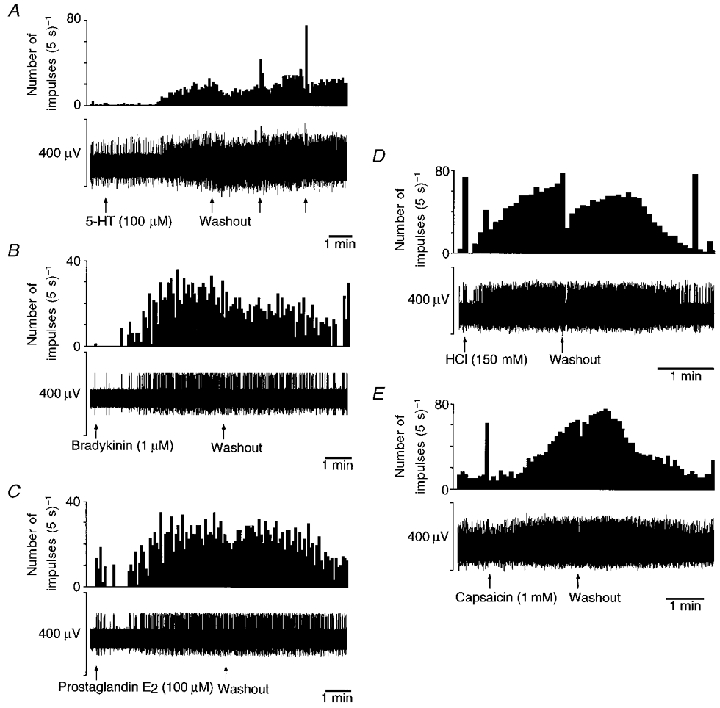

Chemosensitivity

Examples of responses of mucosal afferents to chemical stimuli in oesophagitis are illustrated in Fig. 5. The proportion of oesophageal mucosal afferents sensitive to various chemicals applied to the receptive field is indicated in Table 2. The proportion of afferents responding directly to bradykinin (1 μM), prostaglandin E2 (100 μM), 5-hydroxytryptamine (100 μM), capsaicin (1 mM), hydrochloric acid (150 mM) and αβ-methylene ATP (100 μM) was not significantly different between the control and oesophagitis groups (Table 2).

Figure 5. Responses to applied chemicals.

Representative oesophageal mucosal receptor responses to 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, 100 μM; A), bradykinin (1 μM; B), prostaglandin E2 (100 μM; C), hydrochloric acid (150 mM; D) and capsaicin (1 mM; E) in oesophagitis. The top trace for each section is spike frequency and the bottom trace is the raw recording of electrical activity. The responses shown are not all from the same fibre. Stimuli were left in contact with the receptive field for several minutes to allow full penetration of the mucosal epithelium. In A and E, more than one fibre was active on the strand being recorded. Individual units were discriminated on the basis of waveform. In B–D, the only active fibre is the one under investigation. In C–E a brief burst of firing is initially evoked before the response to chemicals which must have been caused by the mechanical effect of the solution being pipetted into the ring around the receptive field, because a similar initial burst was seen upon application of saline (not shown).

As only a small number of afferents responded to chemical stimuli, changes in the latency and amplitude of response, time to reach maximum and wash out time were not possible to compare quantitatively. We observed that these parameters were all similar in the two groups, and these were generally similar to those we have reported in oesophageal mucosal afferents previously (Page & Blackshaw, 1998). No relationship was found between sensitivity to chemical stimuli and conduction velocity of fibres in control or oesophagitis groups.

DISCUSSION

The data presented indicate that inflammation induces a sensitizing effect of a purinergic receptor agonist on vagal mucosal afferents. Afferents did not show direct excitation after application of the agonist, but their mechanical sensitivity was potentiated. This occurred despite a decrease in basal mechanical sensitivity following inflammation, and a relatively minor change in direct chemical sensitivity to other mediators.

ATP, acting via P2X purinergic receptors, is considered to be a primary signal for activation of sensory neurones following injury or inflammation. Several recent studies have shown that direct excitation occurs, e.g. Lewis et al. (1995); Cook et al. (1997); Dowd et al. (1998); McQueen et al. (1998). However, the proportions of neurones showing direct excitation may have been overestimated because many studies used recordings from neuronal somata after isolation and short-term culture, procedures which may induce direct sensitivity to purines. This was suggested by an investigation of cell somata in intact dorsal root ganglia, which found that they are insensitive to purines, but rapidly gain direct sensitivity after isolation (Stebbing et al. 1998). Of course, in vivo, only the peripheral endings of sensory neurones are exposed directly to ATP derived from injury or inflammation. Still, there are differing reports of purinergic actions on endings, with some studies showing a direct excitation (Dowd et al. 1998; McQueen et al. 1998), and others showing only a sensitization to other modalities of stimulus (Kress & Guenther, 1999). These discrepancies extend even to behavioural investigations (Sawynok & Reid, 1997; Hamilton et al. 1999). Our data show neither direct effects nor simple sensitizing influences of purines, but demonstrate a novel concept of sensitization only after inflammation. It is interesting to compare the findings of Stebbing et al. (1998) with ours. These have in common the observations that effects of purines are rare or absent in intact neurones, yet they become evident after injury – either by severing the axon or by exposing the ending to a hostile environment. Alternatively, a more subtle influence may have given rise to the expression of purinoceptors in our experiments, such as an action of neurotrophins. These are known to be upregulated in inflamed tissue, and are linked with short-term changes in mechanosensory function in urinary bladder over periods up to 3 h (Dmitrieva et al. 1997). Their effects on sensory function over periods of days, such as those in the present study, or on expression of purinoceptors, have not yet been evaluated directly.

The three ways that purinergic receptors influence function of sensory neurones described above (direct, sensitizing and inflammation-induced) are not mutually exclusive. We have preliminary in vitro data using the same apparatus as this study (A. J. Page and L. A. Blackshaw, unpublished observations) showing that gastric spinal mucosal afferents respond directly to αβ-methylene ATP with powerful, short latency excitation, and in vivo data showing that ferret duodenal vagal afferents also show direct sensitivity (L. A. Blackshaw and D. Grundy, unpublished observations). These findings demonstrate that different types of effect can occur in the same organ bath preparation but in a different nerve, and in the same nerve but in afferents ending in a different location. These observations and those published provide evidence for a hierarchically organized sensory system for signalling the release of ATP. Direct excitation provides immediate signals upon tissue damage, sensitization indirectly evokes hypersensitivity to other stimuli, and inflammation-induced expression evokes a longer-term increase in sensitivity of sensory fibres. As the effect of αβ-methylene ATP on mechanosensitivity was maintained throughout the period of perfusion (up to 30 min), we suggest that the receptor subtype involved in its effect is similar to the P2X2/3 heterodimer that was demonstrated to confer maintained responses to αβ-methylene ATP in recombinant systems (Lewis et al. 1995). In the present study, these maintained effects would have been below the threshold for generation of action potentials, but sufficient to lead to generation of increased numbers of action potentials in response to mechanical stimuli.

As mechanosensitivity to stroking was reduced by inflammation, and subsequently enhanced by exposure to the purinergic agonist, this had the net effect of restoring the profile of the stimulus-response curve to that seen in control, un-inflamed tissue. Our data on baseline mechanosensitivity compare favourably with those from a recent detailed clinical study of oesophageal mechanosensitivity in controls and reflux disease, which revealed no increase in oesophagitis (Fass et al. 1998). It can often be argued that comparisons between clinical inflammation and animal models thereof are difficult to make. We are fortunate in this respect that major features are shared between our model of inflammation and that occurring in the clinical setting: the oesophagitis is caused by the same agents in both cases; and histology showed a close correlation of microscopic features. On the other hand, inflammation in vivo was probably in an active state, whereas that in the in vitro preparation would have lacked important circulating influences. Local metabolites of active inflammation in vivo such as ATP would therefore be lacking in vitro, but these could be selectively replaced in the superfusion solution.

The clinical study of Fass et al. (1998) found that in contrast to mechanical sensitivity, sensitivity to acid perfusion was increased in oesophagitis. We found no increase in the sensitivity of vagal afferents to acid or capsaicin, which are both considered to act on the same receptor (Caterina et al. 1997; Tominaga et al. 1998). This would suggest that an alternative, probably spinal, pathway probably mediates increased sensation of oesophageal acidification. This pathway may be further implicated by another study on oesophagitis in ferrets, which found that smooth muscle responses induced by capsaicin were increased four-fold above controls (Smid et al. 1998). The action of capsaicin in this preparation was abolished by chronic degeneration of the spinal innervation (S. D. Smid and L. A. Blackshaw, unpublished observations).

Direct sensitivity of mucosal afferents to purines was not seen in this study, but did occur in a minority of fibres to bradykinin, 5-HT, prostaglandin E2, capsaicin and hydrochloric acid. When responses to these stimuli were evoked, they consisted of powerful excitation of discharge, indicating an all-or-nothing phenomenon. This in turn indicates that when receptors to these stimuli are expressed by afferents, they are coupled efficiently to mechanisms of action potential generation. Previous investigations of cutaneous and visceral sensory fibres have shown sensitivity to these stimuli (Lang et al. 1990; Blackshaw & Grundy, 1993; Page & Blackshaw, 1998; Lynn & Blackshaw, 1999; Maubach & Grundy, 1999). A study of cutaneous afferents demonstrated that an increase in sensitivity to bradykinin occurs after inflammation (Kirchhoff et al. 1990), yet this was not seen in the present study. Changes in sensitivity to other mediators have not received specific attention in the literature.

We conclude that a novel form of sensitization of afferent fibres has been identified, whereby changes in afferent function are induced via purinergic P2X receptors only after inflammation, whereupon they have an indirect action by enhancing mechanical sensitivity. This contrasts with minor changes in other aspects of afferent chemosensitivity.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Ms J. Langman and Dr R. Rowland from the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science Tissue Pathology Division are thanked for their help with histological classification. Dr Alyson J. Fox is rather belatedly thanked for her advice in setting up our in vitro electrophysiological recording preparation.

References

- Blackshaw LA, Grundy D. Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) on the discharge of vagal mucosal afferent fibres in the upper gastrointestinal tract of the anaesthetized ferret. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1993;45:41–50. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Akopian AN, Sivilotti L, Colquhoun D, Burnstock G, Wood JN. A P2X purinoceptor expressed by a subset of sensory neurons. Nature. 1995;377:428–431. doi: 10.1038/377428a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc N, Mei N. Vagal mechanoreceptors located in the lower oesophageal sphincter of the cat. The Journal of Physiology. 1983;336:487–498. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SP, Vulchanova L, Hargreaves KM, Elde R, Mccleskey EW. Distinct ATP receptors on pain-sensing and stretch-sensing neurons. Nature. 1997;387:505–508. doi: 10.1038/387505a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent J. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion. 1998;59:433–445. doi: 10.1159/000007521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrieva N, Shelton D, Rice S, Mcmahon SB. The role of nerve growth factor in a model of visceral inflammation. Neuroscience. 1997;78:449–459. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00575-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd E, Mcqueen DS, Chessell IP, Humphrey PP. P2X receptor-mediated excitation of nociceptive afferents in the normal and arthritic rat knee joint. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;125:341–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fass R, Naliboff B, Higa L, Johnson C, Kodner A, Munakata J, Ngo J, Mayer EA. Differential effect of long-term esophageal acid exposure on mechanosensitivity and chemosensitivity in humans. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1363–1373. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SG, Wade A, Mcmahon SB. The effects of inflammation and inflammatory mediators on nociceptive behaviour induced by ATP analogues in the rat. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;126:326–332. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding H, Titchen DA. Chemosensitive vagal endings in the oesophagus of the cat. The Journal of Physiology. 1975;247:52–53. P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, Humphrey PP, Surprenant A. Electrophysiological properties of P2X purinoceptors in rat superior cervical, nodose and guinea-pig coeliac neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;484:385–395. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff C, Jung S, Reeh PW, Handwerker HO. Carrageenan inflammation increases bradykinin sensitivity of rat cutaneous nociceptors. Neuroscience Letters. 1990;111:206–210. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90369-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress M, Guenther S. Role of [Ca2+]i in the ATP-induced heat sensitization process of rat nociceptive neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;81:2612–2619. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.6.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang E, Novak A, Reeh PW, Handwerker HO. Chemosensitivity of fine afferents from rat skin in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1990;63:887–901. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Neidhart S, Holy C, North RA, Buell G, Surprenant A. Coexpression of P2X2 and P2X3 receptor subunits can account for ATP-gated currents in sensory neurons. Nature. 1995;377:432–435. doi: 10.1038/377432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn PA, Blackshaw LA. In vitro recordings of afferent fibes with receptive fields in the serosa, muscle and mucosa of rat colon. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;518:271–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0271r.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcqueen DS, Bond SM, Moores C, Chessell I, Humphrey PP, Dowd E. Activation of P2X receptors for adenosine triphosphate evokes cardiorespiratory reflexes in anaesthetized rats. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:843–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.843bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maubach KA, Grundy D. The role of prostaglandins in the bradykinin-induced activation of serosal afferents of the rat jejunum in vitro. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;515:277–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.277ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page AJ, Blackshaw LA. In vitro recordings of gastro-oesophageal mucosal afferent fibres innervating the ferret oesophagus and stomach. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;512:907–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.907bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page AJ, Blackshaw LA. GABAB receptors inhibit mechanosensitivity of primary afferent endings. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:8597–8602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08597.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang HP, Bevan S, Dray A. Nociceptive peripheral neurons: cellular properties. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of Pain. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994. pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sawynok J, Reid A. Peripheral adenosine 5′-triphosphate enhances nociception in the formalin test via activation of a purinergic p2X receptor. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;330:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta JN, Kauvar D, Goyal RK. Characteristics of vagal esophageal tension-sensitive afferent fibers in the opossum. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1989;61:1001–1010. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.5.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta JN, Saha JK, Goyal RK. Differential sensitivity to bradykinin of esophageal distension-sensitive mechanoreceptors in vagal and sympathetic afferents of the opossum. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;68:1053–1067. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.4.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smid S, Page AJ, O'donnell TA, Langman J, Rowland R, Blackshaw LA. Oesophagitis-induced changes in capsaicin-sensitive tachykininergic pathways in the ferret lower oesophageal sphincter. Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 1998;10:403–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.1998.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbing MJ, Mclachlan EM, Sah P. Are there functional P2X receptors on cell bodies in intact dorsal root ganglia of rats? Neuroscience. 1998;86:1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]