Abstract

The following study describes the properties of a non-selective cation channel, which has a unit conductance below the resolving power of the single channel technique, located on the basolateral membrane of single proximal tubule cells isolated from frog kidney. The conductance was examined using cell-attached, inside-out and outside-out patches. Due to the small single channel magnitude, macroscopic patch currents were measured.

Addition of 2 mM ATP to the intracellular surface of excised patches activated an outwardly rectifying conductance (MCANS): outward (Gout) and inward (Gin) conductances increased by 46·8 ± 6·7 and 11·6 ± 2·1 pS, respectively (n= 29). MCANS was more selective for cations than anions, with a cation:anion selectivity ratio of 10·1 ± 1·7 (n= 7), but did not discriminate between Na+ and K+. It was more selective for Ca2+ over Na+, with a Ca2+:Na+ selectivity ratio of 4·49 ± 0·69 (n= 7).

In cell-attached patches addition of 100 μM strophanthidin to the bath increased both Gout and Gin. However this increase in conductance was absent in the presence of Gd3+, which inhibits MCANS.

These data suggest that single proximal tubule cells isolated from frog kidney contain an ATP-activated, non-selective cation conductance. The conductance does not discriminate between Na+ and K+, but is more selective for Ca2+ over Na+. Considering the prevailing electrochemical gradients for these ions, functional activation of the conductance would be expected to lead to a rise in intracellular Ca2+. MCANS is linked to the activity of the Na+,K+-ATPase and may therefore provide a link between the ATPase and K+ channel activity in the basolateral membrane and form an integral part of the pump-leak mechanism in transporting epithelia.

Non-selective cation channels have been identified in both excitable and non-excitable cells, where they are thought to play diverse roles, including the regulation of electrical excitability, smooth muscle contraction and volume regulation (Sachs, 1987; Wison et al. 1998; Takenaka et al. 1998). One common property of these non-selective channels is that they are permeable to monovalent cations, and on activation would be expected to allow extracellular Na+ to enter the cell and intracellular K+ to exit (Gustin et al. 1988; Bear, 1990; Filipovic & Sackin, 1991; Chraibi et al. 1994; Kock & Korbmacher, 1999). In addition, some non-selective channels are also permeable to divalent cations, and would therefore be expected to allow Ca2+ to enter the cell on activation (Gustin et al. 1988; Bear, 1990; Filipovic & Sackin, 1991).

Due to the large electrochemical driving force for Ca2+ movement, it is the Ca2+ permeability of these channels that is thought to be functionally important, with activation of the channels leading to a rise in intracellular Ca2+. Many of these channels are directly sensitive to the tension in the cell membrane, with activity increasing in response to a rise in tension, whether induced by the application of pressure or by hypotonic shock (Gustin et al. 1988; Bear, 1990; Filipovic & Sackin, 1991). These channels are thought to play an important role in volume regulation, with the rise in intracellular Ca2+ resulting from channel activation leading to the activation of solute exit pathways and subsequent recovery of cell volume. In the mouse collecting duct there is a non-selective cation channel that is activated upon cell shrinkage, implying a role in the regulation of collecting duct cell volume (Volk et al. 1995).

While the permeation properties of these channels are similar, i.e. a lack of discrimination between monovalent cations, high permeability to Ca2+ and low anion permeability, their regulation is often very different. For example, mouse collecting duct and thick ascending limb, cultured liver cells and insulin-producing tumour cells contain cation channels that are inhibited by intracellular ATP or AMP (Sturgess et al. 1987; Paulais & Teulon, 1989; Volk et al. 1995; Lidofsky et al. 1997), while the channel in Aplysia abdominal ganglia is activated by intracellular ATP (Wison et al. 1998). Despite a shared sensitivity to ATP, the mouse collecting duct channel is modulated by changes in intracellular pH (Chraibi et al. 1995), while the liver cation channel is insensitive to pH (Lidofsky et al. 1997). The ATP sensitivity of non-selective cation channels raises the possibility that they may be linked to the metabolic state of the cell and could therefore provide a link between the activity of the Na+,K+-ATPase and other transport pathways. Certainly, in the renal proximal tubule, the activity of the Na+,K+-ATPase appears to be linked to the activity of the basolateral K+ conductance (Messner et al. 1985) via changes in intracellular ATP concentration. The aim of the following study was to examine the properties and regulation of a small conductance, non-selective cation channel located on the basolateral membrane of single proximal tubule cells isolated from frog kidney and to determine whether this conductance was linked to the activity of the Na+,K+-ATPase.

METHODS

Cell isolation

Single proximal tubule cells were isolated by enzyme digestion from kidneys of Rana temporaria as described previously (Hunter, 1989). Frogs were killed by decapitation and the brain and spinal cord destroyed. Kidneys were removed and perfused with a divalent cation-free Ringer isolation solution which contained 101 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl and 10 mM Hepes (titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH). This promoted the dissociation of the tight junctions. Perfused kidneys were then injected with a mixture of collagenase and pronase, minced and then shaken in a water bath for 10 min. After this period the tissue suspension was removed and single cells sheared from the kidney fragments by trituration. Enzyme digestion was halted by a series of centrifugation and re-suspension steps and the final cell suspension stored on ice. This technique resulted in the generation of a mixed population of single cells derived from the whole kidney. Proximal cells were identified from their ‘snowman’-like appearance (Hunter, 1990).

Patch clamp

A suspension of single cells was placed in a Perspex bath on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Diaphot or Olympus IX70) and standard patch clamp techniques employed to investigate single channel currents (Hamill et al. 1981). Voltage protocols were driven from an IBM-compatible computer equipped with a Digidata or TL-1 interface, using the pCLAMP software program Clampex (Axon Instruments). Recordings were made using a List EPC-7 amplifier. Cell-attached, inside-out and outside-out excised patches were obtained via the basolateral aspect of the cells and currents either saved directly onto the hard disk of the computer following low-pass filtering at 5 kHz or saved onto DAT (DAT recorder Biologic DTR-1250). Pipette potential was maintained at a holding potential of 0 mV and then stepped to potentials between +100 and −100 mV in −20 mV steps. Due to the small single channel current magnitude, the macroscopic patch currents were measured (see Fig. 1). Mean steady-state currents were derived from the currents flowing within 40 ms of the end of each potential step using Clampfit software and Excel version 7.0 (Microsoft, USA). Reversal potentials (Vrev) of ohmic or rectifying currents were calculated by linear or polynomial regression, respectively. Outward (Gout) and inward (Gin) slope conductances were calculated for outward- and inward-directed currents either side of the reversal potential of the current. In some experiments slope conductance was calculated over the potential range +100 to −100 mV (Gslope). For estimation of single channel conductance, macroscopic current was recorded at a pipette potential of −40 mV, in response to increasing concentrations of ATP (0 mM to 10 mM). Data were initially saved onto DAT and the full recording subsequently saved onto the hard disk of the computer using pCLAMP 6. This recording was then broken down into 200 ms traces and the variance calculated (Excel version 7.0). To compensate for background noise, the variance of current recorded from a different patch at the same potential in the presence of gadolinium was subtracted. This background-corrected variance was then plotted against mean trace current and the data fitted by a parabolic equation (eqn (1)) to give an estimate of single channel current (Lewis et al. 1984):

| (1) |

where σ2 is the variance, i is the single channel current, I is the mean current and N is the number of channels.

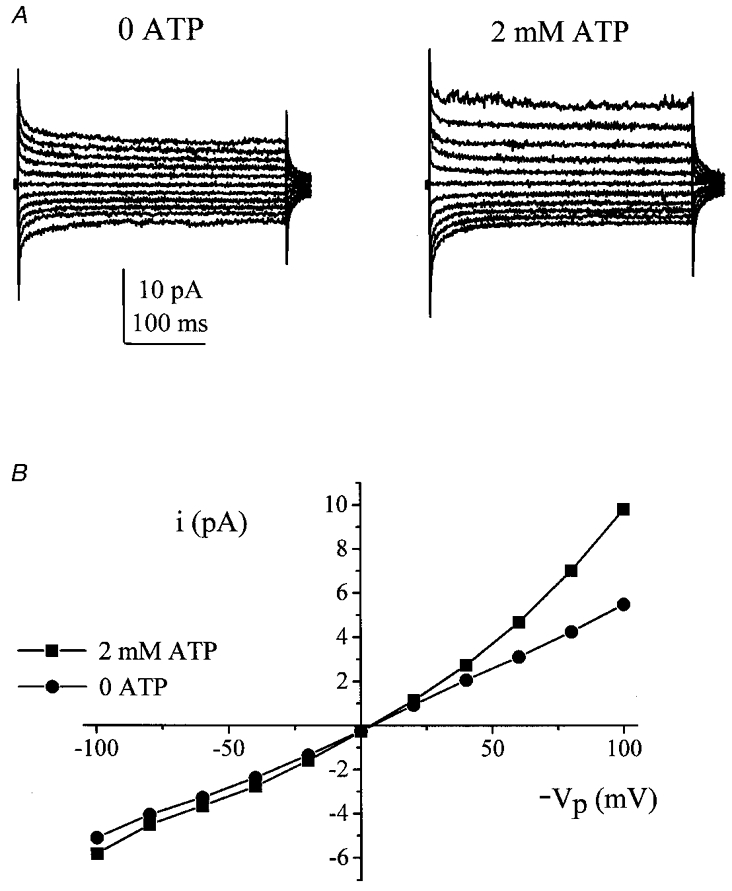

Figure 1. Effect of 2 mM ATP.

A, excised inside-out patch currents taken from a typical recording in the absence (left) and presence (right) of 2 mm ATP. B, I–V curves (patch current plotted against minus pipette potential, -Vp) recorded from these traces (•, 0 ATP; ▪, 2 mm ATP).

Solutions

The osmolality of solutions was measured (Roebling osmometer) and adjusted to within 1 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 of 215 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 with water or mannitol as appropriate. When 50 mM BaCl2 was included in the pipette solution no compensation of osmolality was made. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma and were of analytical grade.

Except where stated, the following solutions were used. In inside-out excised patch experiments the pipette contained high Ca2+, K+ amphibian Ringer solution (100 K+, Table 1) and the bath contained low Ca2+, Na+ amphibian Ringer solution (100 Na+, Table 2). In outside-out excised patch experiments the pipette contained low Ca2+, K+ amphibian Ringer solution (100 K+, Table 2) and the bath contained high Ca2+, high Na+ amphibian Ringer solution (97 Na+, Table 1).

Table 1.

Extracellular solutions

| 97 Na+ | 20 CaCl2 | 100 K+ | 50 Na+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl (mm) | 97 | 4 | — | 50 |

| KCl (mm) | 3 | — | 100 | 3 |

| CaCl2 (mm) | 2 | 20 | 2 | 2 |

| MgCl2 (mm) | 1 | — | 1 | 1 |

| Hepes (mm) | 10* | 10† | 10** | 10* |

| NMDG (mm) | — | 70.5 | — | — |

| Mannitol (mm) | — | — | — | 89 |

Titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH

titrated to pH 7.4 with KOH

titrated to pH 7.4 with HCl.

Table 2.

Intracellular solutions

| 100 Na+ | 2 CaCl2 | 100 K+ | 100 Cs+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl (mm) | 100 | 100 | — | — |

| KCl (mm) | — | — | 100 | — |

| CsCl (mm) | — | — | — | 100 |

| CaCl2 (mm) | — | 2 | — | — |

| MgCl2 (mm) | 2 | — | 1 | 2 |

| Hepes (mm) | 10* | 10** | 10† | 10‡ |

| Mannitol (mm) | 5 | — | 5 | 20 |

| EGTA (mm) | 0.5 | — | 5 | 0.5 |

Titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH

titrated to pH 7.4 with NMDG

titrated to pH 7.4 with KOH

titrated to pH 7.4 with CsOH.

Experimental protocols

Effect of ATP

Excised inside-out patches were initially superfused with Na+ Ringer solution that contained no ATP. This was exchanged for a solution that contained 2 mM Na2ATP (removal of 5 mM mannitol to maintain osmolality). On reaching a new steady state, ATP was then washed out from the bath. To determine whether the effect of ATP on patch currents was a direct action or via a mechanism dependent on ATP hydrolysis, each patch was exposed sequentially to 2 mM ATP and 2 mM 5′-adenylimidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP, a non-hydrolysable analogue of ATP) in a random order.

The sensitivity to ATP was examined in inside-out patches. The bath contained Cs+, to inhibit K+ channels (100 Cs+, Table 2) and the pipette contained high Ca2+, K+ amphibian Ringer solution (100 K+, Table 1). The MgATP concentration was varied between 1 and 10 mM (substitution by mannitol) and patch current recorded at a pipette potential of −40 mV (patch potential, +40 mV). These solutions were also used to determine single channel conductance.

Blocker sensitivity

Excised inside-out patches were superfused with Na+ Ringer solution and then exposed to 2 mM ATP as described above. This was carried out with 100 μM gadolinium (Gd3+, a blocker of stretch-activated channels) or 50 mM barium (Ba2+, a K+ channel inhibitor) present in the pipette solution. This concentration of Gd3+ (100 μM) has previously been shown to maximally inhibit GVI, a cation-selective conductance previously identified in the cells (Robson & Hunter, 1994b); the concentration of Ba2+ used (50 mM) was 10 times the concentration that has been shown to produce half-maximal inhibition of GVI (Robson & Hunter, 1994b).

The inhibition of the whole-cell conductance GVI by Gd3+ is irreversible. To examine whether the effect of Gd3+ on the control and ATP-activated patch currents was also irreversible the outside-out excised patch technique was employed. Outside-out patches were obtained with 100 K+ (plus or minus ATP) in the pipette (Table 2). Patches were superfused with high Na+ bath Ringer solution (97 Na+, Table 1) and then exposed to 100 μM Gd3+. Once the effect of Gd3+ had reached steady state, Gd3+ was removed from the bath and current recovery monitored.

Ionic selectivity of patch currents

In excised inside-out patches the cation:anion selectivity ratio of current was determined using a dilution protocol. Currents were initially recorded with 100 mM Na+ Ringer solution in the bath. The concentration of Na+ and Cl− in the bath was then dropped fivefold. Under these circumstances if the currents were cation selective the Vrev should shift in a positive direction by 40 mV, while if the currents were anion selective the Vrev should shift in a negative direction by 40 mV. This was carried out in the absence and presence of bath ATP. All values obtained for Vrev were corrected for the junction potential shift that occurred on dropping bath Cl−. Junction potential shifts were measured using a flowing 3 M KCl reference electrode.

Ionic selectivity of Gd3+-sensitive current

Examination of the selectivity of the patch current suggested that, on addition of ATP to the intracellular face of the patch, there was activation of a Gd3+-sensitive, cation-selective conductance (see Results). To examine the selectivity of this conductance a second series of experiments was carried out using the outside-out excised patch technique, which directly examined the selectivity of the Gd3+-sensitive current. The Gd3+-sensitive current was recorded in the absence and presence of ATP. The Na+:K+ selectivity ratio was determined with high K+ in the pipette (100 K+, Table 2) and high Na+ in the bath (97 Na+, Table 1). The Ca2+ permeability of the Gd3+-sensitive current was examined with high Na+ in the pipette (2 CaCl2, Table 2), while the bath contained 20 mM CaCl2 (Table 1). Gd3+-sensitive current was recorded in the absence and presence of ATP and the Ca2+:Na+ selectivity ratio calculated (Robson & Hunter, 1994b). Under these circumstances the Vrev for Na+-selective currents was −81 mV, the Vrev for Ca2+-selective currents was +29 mV and the Vrev for Cl−-selective currents was −2 mV.

pH sensitivity

It has been reported that non-selective cation channels may be regulated by changes in H+ concentration (Chraibi et al. 1995). To determine whether the patch current was also modulated by H+, excised inside-out patches were obtained with Na+ Ringer solution in the bath at pH 7.4. The pH was then altered to 8.2 and 6.2 using NaOH and HCl, respectively. This was carried out in the absence and presence of 2 mM ATP. Cells were exposed to the solutions in a random order.

Effect of pressure and hypotonic shock

The effect of pressure was examined in both cell-attached and excised, inside-out patches. Excised, inside-out patches were obtained with 100 K+ in the pipette (Table 1) and 100 Na+ in the bath (Table 2). Currents were recorded in the absence of an imposed pressure gradient and then in the presence of +12 cmH2O. A constant pressure gradient was imposed via a water manometer, which was connected to the pipette holder. This was carried out in the absence and presence of 2 mM ATP. When the effect of pressure was examined in cell-attached patches both the pipette and bath contained 50 Na+ (Table 1). Again, currents were recorded in the absence of an applied pressure gradient and then in the presence of +12 cmH2O.

To determine the effect of cell swelling on the conductance, cell-attached patches were obtained via the basolateral membrane with 50 Na+ (Table 1) in both the pipette and bath. An osmotic gradient was imposed across the cell membrane by the removal of 40 mM mannitol from the bath. A previous study has shown that, in intact cells, the peak increase in cell length from a 40 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 osmotic shock is typically observed within 1–2 min (Robson & Hunter, 1994a). Patch current was therefore recorded 1, 2 and 5 min after exposure of the cells to the hypotonic shock.

Effect of pump inhibition

Cell-attached patches of the basolateral membrane were obtained with 97 Na+ (Table 1) in both the bath and pipette. Cells were then exposed to 100 μM strophanthidin, which inhibits the Na+,K+-ATPase (Beck et al. 1991). In unpaired cells, the effect of strophanthidin was examined in the absence or presence of 100 μM Gd3+ in the pipette.

Statisics

All values are given as means ± 1 s.e.m. Significance was tested using Student's t test or ANOVAs as appropriate and was assumed at the 5 % level.

RESULTS

Effect of ATP

Currents were recorded with 100 K+ in the pipette and 100 Na+ in the bath in the excised inside-out patch configuration. In the control circumstance Gout was 31.1 ± 3.9 pS, while Gin was 25.7 ± 2.1 pS (n= 29 patches). On addition of 2 mM ATP to the intracellular face of the patch there was a significant increase in both Gout and Gin to 78.3 ± 9.7 and 35.8 ± 3.4 pS, respectively (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1). ATP increased patch current in all 29 patches tested. The control currents were linear, whereas the conductance activated by ATP showed outward rectification. The ATP-activated increase in Gout (46.8 ± 6.7 pS) was 4 times greater than the increase in Gin (11.6 ± 2.1 pS; P < 0.0001).

The reversibility of the response to ATP was examined in nine patches. In these patches Gout was 38.7 ± 11.4 pS under the control circumstance, 103.1 ± 31.8 pS in the presence of ATP and 37.2 ± 6.8 pS after washing off ATP from the intracellular surface of the patch. Gin was 26.6 ± 3.6 pS under the control circumstance, 35.0 ± 4.9 pS in the presence of ATP and 31.2 ± 4.0 pS on removal of ATP. There was no significant difference between Gout measured in either control or wash circumstances. There was also no significant difference between Gin values.

The stimulatory effect of ATP was only partially reproduced by exposure of patches to AMP-PNP. In paired patches, addition of 2 mM ATP to the bath increased Gout and Gin by 148.6 ± 27.4 and 115.0 ± 25.8 pS, respectively (n= 7). This was significantly reduced to 103.9 ± 19.7 and 70.9 ± 27.9 pS (n= 7) in the presence of the same concentration of AMP-PNP (P= 0.009 and 0.03, respectively).

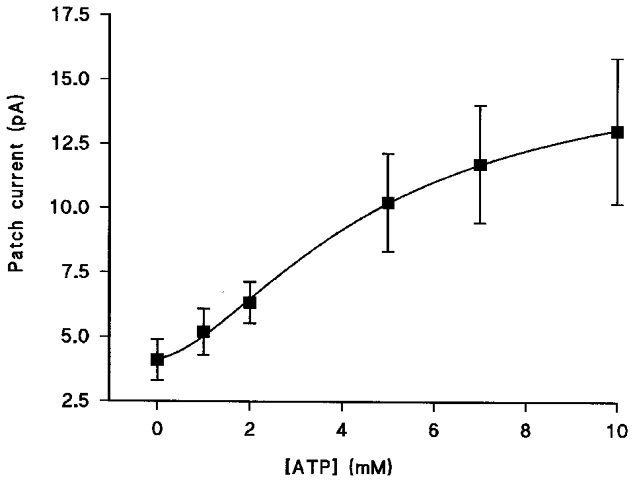

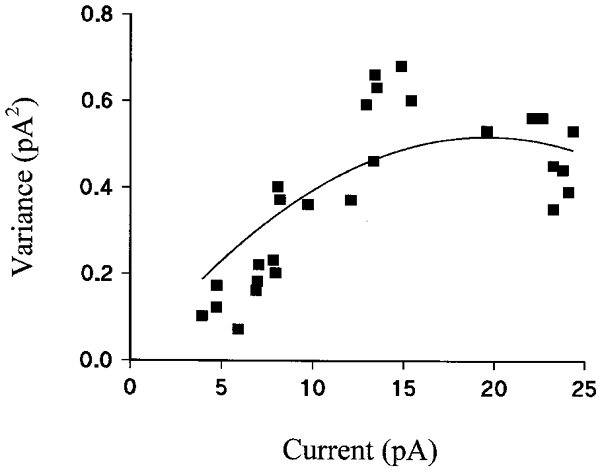

In inside-out patches, with K+ in the pipette and Cs+ in the bath, ATP activated the patch current in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2). Maximal activation was obtained with 10 mM ATP. A Hill plot of the activation gave a half-maximal activation concentration (Kd) of 3.68 ± 0.61 mM (n= 9) and a value of nHof 2.32 ± 0.33 (n= 9). Noise analysis gave an estimate of single channel current at +40 mV of 0.030 ± 0.005 pA (n= 9), corresponding to a single channel conductance of 0.75 ± 0.13 pS (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Dose-response curve for ATP.

The graph shows the mean current recorded in excised inside-out patches at a patch potential of +40 mV plotted against ATP concentration. Each data point is the mean of nine cells and the error bars show the s.e.m. The line though the data is the best fit to the Hill equation.

Figure 3. Estimation of single channel current.

The graph shows the variance of the current recorded at +40 mV in excised inside-out patches against mean current. Data points were all taken from the same patch and the line through the data is the best fit to eqn (1).

Blocker sensitivity

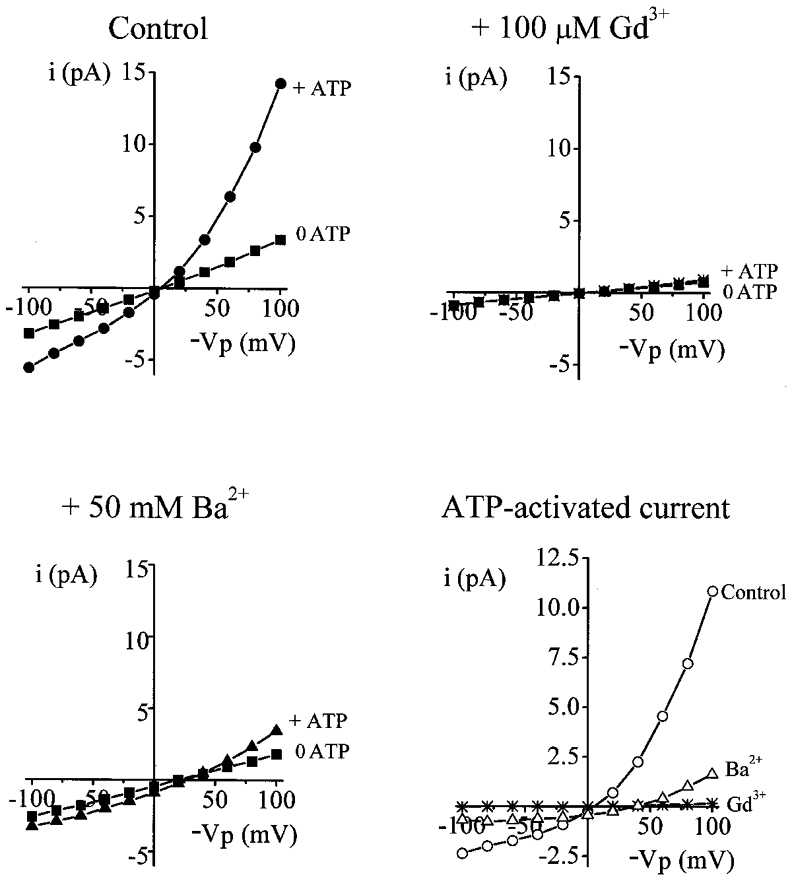

In excised inside-out patches, with K+ in the pipette and Na+ in the bath, 100 μM Gd3+ or 50 mM Ba2+ in the pipette inhibited the currents recorded in the absence of 2 mM ATP (Fig. 4). In the absence of blockers, Gout was 33.4 ± 3.5 pS (n= 37). In the presence of Gd3+ or Ba2+ in the pipette, Gout fell to 12.8 ± 2.7 pS (n= 8) and 18.0 ± 2.5 pS (n= 8), respectively (F2,50= 5.72). Gin was also reduced by Gd3+ and Ba2+, from 26.9 ± 2.0 pS (n= 37) in control to 13.5 ± 1.5 pS (n= 8) and 16.1 ± 2.1 pS (n= 8) in the presence of Gd3+ and Ba2+, respectively (F2,50= 7.75).

Figure 4. Effect of Ba2+ and Gd3+ on the ATP-dependent activation of currents.

All I–V curves show typical excised inside-out recordings obtained: top left, control circumstance; top right, presence of Gd3+; bottom left, presence of Ba2+ (▪, 0 ATP; •, ⋇ and ▴, 2 mM ATP). The bottom right plot shows the ATP-activated current taken from the three preceding I–V curves (^, control circumstance; ⋇, presence of Gd3+; ▵, presence of Ba2+).

Gd3+ and Ba2+ also inhibited the increase in conductance typically observed on addition of 2 mM ATP to the intracellular face of the patch (Fig. 4). The increase in Gout on addition of ATP to the bath was 46.8 ± 6.7 pS (n= 29), 7.8 ± 2.1 pS (n= 8) and 23.0 ± 1.8 pS (n= 8) in the control circumstance, and in the presence of pipette Gd3+ and Ba2+, respectively (F2,42= 6.60). The increase in Gin on addition of ATP to the bath was 11.56 ± 2.12 pS (n= 29), 3.53 ± 1.88 pS (n= 8) and 3.43 ± 1.09 pS (n= 8) in the control circumstance, and in the presence of pipette Gd3+ and Ba2+, respectively (F2,42= 3.37).

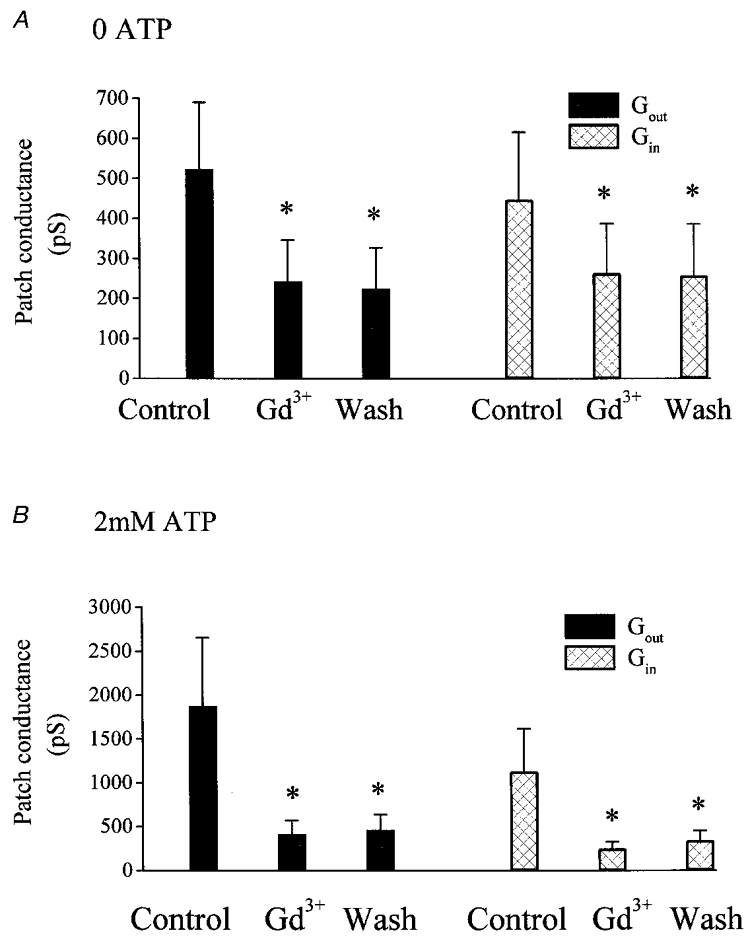

The effect of Gd3+ on outside-out patch currents, recorded with K+ in the pipette and Na+ in the bath, in the absence (n= 10) or presence (n= 20) of 2 mM ATP was irreversible (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Irreversibility of Gd3+ inhibition.

Excised outside-out patch conductance under the control circumstance, in the presence of 100 μM Gd3+ and on washout of Gd3+ from the bath, in the absence of pipette ATP (A) and in the presence of pipette ATP (B). * Significant difference from the conductance recorded under the control circumstance (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the patch conductance recorded in the presence of Gd3+ and on washout of Gd3+ from the bath.

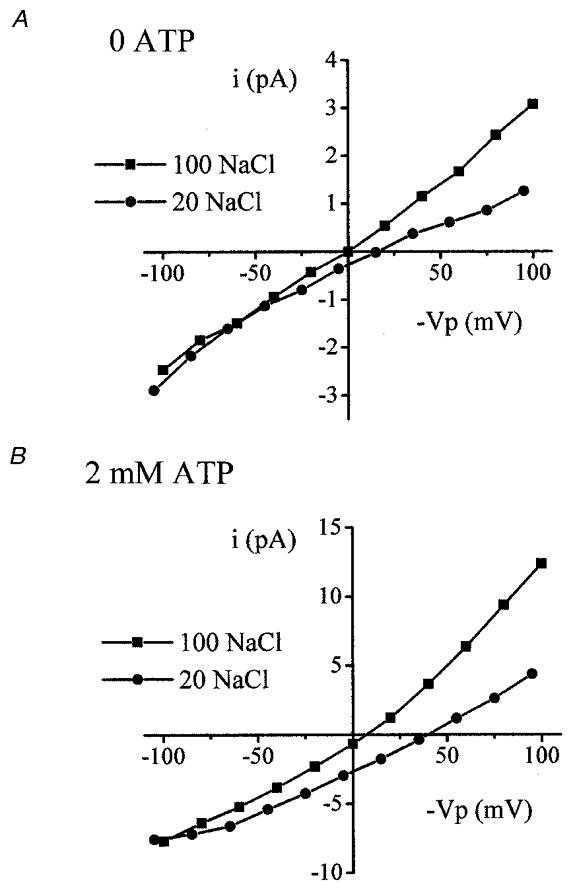

Ionic selectivity of patch currents

The ionic selectivity of patch currents was recorded with inside-out patches. Recordings were made with K+ in the pipette and Na+ in the bath. In the absence of ATP, patches were cation selective. The Vrev of currents in 100 mM bath NaCl was 1.20 ± 2.0 mV (n= 7). This shifted to 22.8 ± 5.0 mV on a fivefold dilution of Na+ and Cl−, a mean change in Vrev of 21.6 ± 3.9 mV (P= 0.001; Fig. 6a) corresponding to a cation:anion selectivity ratio of 6.3 ± 2.3. However, in the presence of ATP, currents were more cation selective. The Vrev in 100 mM NaCl was not significantly different to that recorded in the absence of ATP (3.5 ± 1.6 mV, n= 7). On dilution of bath NaCl, Vrev shifted to 33.7 ± 2.5 mV, a mean shift of +30.2 ± 1.1 mV (P < 0.0001; Fig. 6B). The change in Vrev was significantly greater than that observed in the absence of ATP and corresponded to a cation:anion selectivity ratio of 10.1 ± 1.7 (P= 0.04).

Figure 6. The cation:anion selectivity of patch current.

I–V curves for recordings taken from typical excised inside-out patches. Currents were recorded in response to the dilution of bath NaCl in the absence of ATP (A) and in the presence of ATP (B). ▪, 100 mM NaCl; •, 20 mM NaCl.

The channel has an apparent permeability to Ba2+. In excised inside-out patches, with symmetrical monovalent cation concentrations (K+ in the pipette and Na+ in the bath), the Vrev in the presence of Ba2+ was +19.5 ± 1.14 mV (n= 12) in the absence of ATP and +24.1 ± 1.56 mV (n= 9) in the presence of ATP. The unpaired shift in Vrev between Ba2+-free and Ba2+-containing recordings was +18.69 and +20.46 mV, in the absence and presence of ATP, respectively. Estimating the Ba2+:Na+ permeability ratio from these values gives 1.96 and 3.1.

Ionic selectivity of Gd3+-sensitive current

The ionic selectivity of the Gd3+-sensitive current was recorded in excised, outside-out patches, with K+ in the pipette and Na+ in the bath. In the absence of ATP the Vrev of the Gd3+-sensitive current was −7.29 ± 4.04 mV (n= 11). This corresponded to a Na+:K+ selectivity ratio of 0.82 ± 0.11 (n= 11), which was not significantly different from 1. In the presence of ATP the Vrev of the Gd3+-sensitive current was −0.50 ± 1.66 mV (n= 20). This corresponded to a Na+:K+ selectivity ratio of 1.07 ± 0.08 (n= 20), which was not significantly different from 1. There was no significant difference between either the Vrev or the selectivity ratios in the absence and presence of ATP.

The Ca2+:Na+ permeability was determined in excised outside-out patches under biionic conditions. In the absence of intracellular ATP, the Gd3+-sensitive current was more selective for Ca2+ than for Na+. The Vrev of the Gd3+-sensitive current was −1.91 ± 2.39 mV, which corresponded to a Ca2+:Na+ selectivity ratio of 2.53 ± 0.53 (n= 6). In the presence of ATP, Gd3+-sensitive current was also more selective for Ca2+ over Na+. The Vrev of the Gd3+-sensitive current was 6.01 ± 1.87 mV, which corresponded to a Ca2+:Na+ selectivity ratio of 4.49 ± 0.69 (n= 7). There was no significant difference between either the Vrev or the selectivity ratios in the absence and presence of ATP.

pH sensitivity

In excised inside-out patches, with K+ in the pipette and Na+ in the bath, the conductance and selectivity of the basal and ATP-activated currents were insensitive to intracellular pH changes. In the absence of ATP, there was no significant change in Vrev on altering bath pH. The Vrev was 9.0 ± 3.13, 8.16 ± 2.52 and 4.32 ± 3.91 mV at pH 7.4, 8.2 and 6.2, respectively (n= 10). There was also no change in conductance (Table 3). In the presence of ATP, changing pH was also without effect on either the Vrev or conductance (Table 3). The Vrev was 1.75 ± 1.93, 4.64 ± 1.38 and −1.21 ± 3.07 mV at pH 7.4, 8.2 and 6.2, respectively (n= 6).

Table 3.

Effect of changes in intracellular pH on conductance

| pH 7.4 | pH 8.2 | pH 6.2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 ATP, Gout (pS) | 249.5 ± 36.5 | 269.4 ± 40.7 | 246.8 ± 33.8 |

| 0 ATP, Gin (pS) | 292.7 ± 85.2 | 327.5 ± 90.2 | 285.2 ± 86.1 |

| 2mm ATP, Gout (pS) | 352.5 ± 96.2 | 348.3 ± 81.5 | 359.9 ± 98.3 |

| 2mm ATP, Gin (pS) | 164.4 ± 30.1 | 172.2 ± 27.6 | 184.8 ± 28.3 |

0 ATP cells, n = 10; 2 mm ATP cells, n = 6.

Effect of pressure and hypotonic shock

In excised inside-out patches, with K+ in the pipette and Na+ in the bath, currents recorded in the absence or presence of ATP were not pressure sensitive. In the absence of an imposed pressure gradient, without ATP in the bath, Gslope was 186.3 ± 32.9 pS (n= 13). Gslope was unchanged by imposing +12 cmH2O on the patch (182.1 ± 31.6 pS). A similar lack of response was observed with ATP in the bath. Gslope was 220.7 ± 53.3 vs. 217.8 ± 53.2 pS in the absence and presence of +12 cmH2O, respectively (n= 9). A lack of pressure sensitivity was also observed in cell-attached patches. Gslope was 162.0 ± 64.0 pS in the absence of an applied pressure gradient and 163.3 ± 65.5 pS in the presence of +12 cmH2O (n= 6).

Exposure of intact cells to a hypotonic shock had no effect on the magnitude of currents recorded in cell-attached patches. Gslope was 91.3 ± 15.5 pS in control solution and 86.4 ± 17.3 pS 5 min after exposure of cells to a hypotonic shock (n= 8).

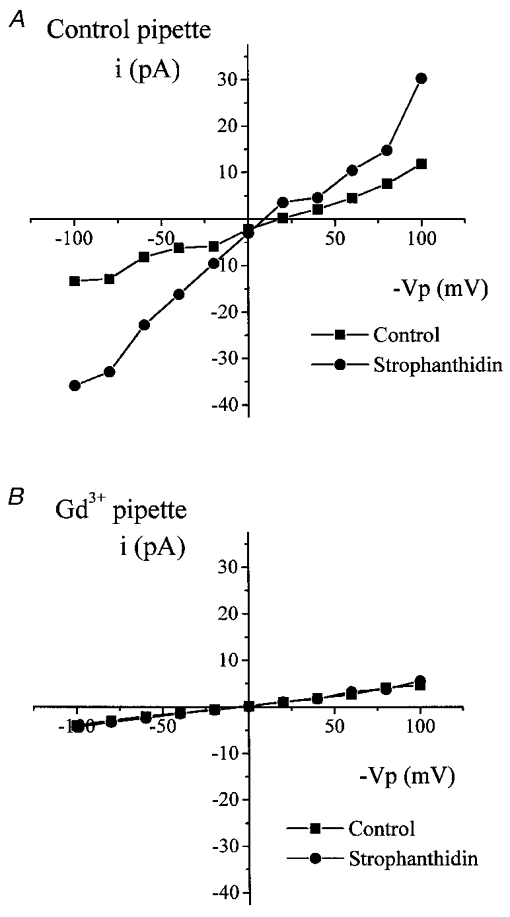

Effect of pump inhibition

In cell-attached patches, with Na+ in the bath and the pipette, Gd3+ inhibited the resting current. In unpaired cells, Gout was 144.7 ± 20.9 pS (n= 12) in the absence of Gd3+, and 65.5 ± 6.71 pS (n= 6) in the presence of Gd3+ (P= 0.002). Gin was similarly inhibited, with values of 111.5 ± 12.4 pS (n= 12) and 59.3 ± 8.52 pS (n= 6) in the absence and presence of Gd3+, respectively (P= 0.002).

Addition of strophanthidin to the solution bathing the cells increased Gout and Gin (Fig. 7). Gout increased from 148.0 ± 25.0 pS in the control circumstance to 302.6 ± 54.1 pS (n= 8) in the presence of strophanthidin (P= 0.009). Gin increased from 117.3 ± 12.7 pS in the control circumstance to 213.9 ± 38.3 pS (n= 8) in the presence of strophanthidin (P= 0.02). This increase in Gout and Gin was absent when Gd3+ was included in the pipette solution. Gout and Gin were 65.5 ± 6.71 vs. 55.3 ± 10.5 pS (n= 6) and 59.3 ± 8.52 vs. 55.6 ± 9.75 pS (n= 6), in the absence and presence of strophanthidin, respectively.

Figure 7. The effect of strophanthidin on cell-attached patch current.

I–V curves for recordings from two typical cell-attached patches in response to addition of 100 μM strophanthidin to the bath in the control circumstance (A) and with 100 μM Gd3+ in the pipette (B). ▪, control current; •, current recorded in the presence of strophanthidin.

DISCUSSION

Addition of ATP to the intracellular surface of excised, inside-out patches of the basolateral membrane of frog isolated proximal tubule cells caused a rise in both outward and inward conductance. Several pieces of evidence suggest that this rise in conductance was not simply due to a change in the leak conductance. (1) The increase in conductance was inhibited by Gd3+ and Ba2+, well-known inhibitors of non-selective cation channels. (2) In the presence of ATP, patch currents changed from exhibiting non-rectifying to exhibiting outwardly rectifying behaviour. (3) The cation:anion selectivity ratio of patch current was increased in the presence of ATP. Therefore, ATP activates a small conductance, cation-selective, outwardly rectifying conductance (MCANS) in patches of the basolateral membrane.

Conductance properties and selectivity

The estimated single channel conductance of the channel is severalfold less than those of other non-selective cation channels, which are around 28 pS (Chraibi et al. 1994; Marunaka et al. 1994; Volk et al. 1995; Kock & Korbmacher, 1999). To our knowledge, there are no previous reports of such small cation channels – this could be a consequence of the small single channel current amplitude. Indeed, MCANS cannot be resolved at the single channel level and appears as background noise in single channel recordings.

Addition of ATP increased the cation:anion selectivity ratio of the patch current from 6.3 to 10.1, suggesting that it activated a cation-selective conductance. This high cation selectivity is different to two Gd3+-sensitive whole-cell conductances that have been identified previously in the cells (ratios of 0.34 for GVD and 4.27 for GVI) (Robson & Hunter, 1994b). Despite being cation selective, MCANS did not discriminate between K+ and Na+. The Vrev with Na+ as the dominant cation on one side and K+ on the other side of the patch was not significantly different from zero in either the absence or the presence of ATP. Again, this is similar to many other cation conductances and also to GVD, although GVI is slightly selective for K+ over Na+ (Robson & Hunter, 1994b). The ATP-activated conductance was also both Ca2+ and Ba2+ permeable; in fact, the permeability to these divalent cations was higher than that of Na+ (a selectivity relative to Na+ of 4.49 and 3.1, respectively). The Ca2+:Na+ selectivity was similar to that recorded for GVD and GVI (3.8 and 2.6, respectively). Considering the prevailing electrochemical gradients, on activation this conductance would be expected to allow both Ca2+ and Na+ to enter, and K+ to exit, the cell. However, taking into account the magnitude of the electrochemical driving forces for these three cations, it seems likely that the movement of Ca2+ may be of greatest functional importance.

Blocker sensitivity

MCANS was inhibited by Gd3+ and Ba2+. The inhibition by Gd3+ was irreversible. Such an irreversible action of Gd3+ has been observed for other cation conductances and also for the previously identified conductance GVI (Yang & Sachs, 1989; Filipovic & Sackin, 1991; Robson & Hunter, 1994b). In addition, GVI also seems to be sensitive to Ba2+, in a similarly high concentration range – suggesting that MCANS may be attributable to GVI. However, there are several important differences between the two conductances. MCANS demonstrates outward rectification, while GVI is ohmic (Robson & Hunter, 1994b). GVI was only observed in approximately half of the cells tested, while MCANS was present in all patches of the basolateral membrane. Finally, the selectivities of the conductances are different (see selectivity discussion). Taken together, these results suggest that MCANS and GVI are probably different conductances.

pH and pressure

The cation channel identified in mouse cortical collecting duct is regulated by changes in intracellular pH (Chraibi et al. 1995). However, MCANS was not affected by changes in intracellular pH. In addition, many non-selective cation channels are activated by pressure. Indeed, this ‘stretch sensitivity’ is thought to confer a role for these channels in the regulation of cell volume (Gustin et al. 1988; Bear, 1990; Filipovic & Sackin, 1991). However, MCANS was not sensitive to pressure in either cell-attached or excised patches, suggesting that it is not regulated directly by membrane stretch. In addition, as exposure of cells to an osmotic shock did not alter the magnitude of MCANS, it does not appear to be regulated by cell volume.

ATP sensitivity

MCANS was activated by ATP in a dose-dependent manner. Several non-selective cation channels are regulated by intracellular ATP. In rat and mouse collecting duct, for example, millimolar concentrations of ATP inhibit channels located on the apical and basolateral membrane (Nonaka et al. 1995; Volk et al. 1995). In the mouse proximal tubule there is evidence for a basolateral ATP-inhibited cation channel (Chraibi et al. 1994). In contrast, abdominal ganglia isolated from Aplysia contain an ATP-activated cation channel (Wison et al. 1998). Half-maximal activation of MCANS was observed with 3.68 mM ATP. This is within the physiological range reported for the ATP concentration in rabbit renal proximal tubule, which varies between 2–4 mM and 2–2.4 mM, in response to changes in transepithelial Na+ transport and pump inhibition by strophanthidin (Beck et al. 1991). This suggests that the conductance could be regulated by physiological concentrations of ATP. Interestingly, addition of strophanthidin to the cells activated a Gd3+-sensitive conductance in cell-attached patches, although the level of activation of the conductance was greater than that predicted from looking at the dose-response data (Fig. 2) and the increase in ATP recorded in response to strophanthidin in rabbit (Beck et al. 1991). However, as the rabbit ATP measurements were carried out on total cell ATP, it is feasible that much greater local changes in ATP concentration could occur in the cells in response to strophanthidin. Such local changes in ATP may play a role in the regulation of basolateral ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the proximal tubule.

Two-thirds of the response to ATP was reproduced by addition of the non-hydrolysable analogue of ATP, AMP-PNP, to the intracellular surface of the patch. This suggests that ATP exerted at least part of its action via allosteric binding that was independent of ATP hydrolysis. The smaller activation observed with AMP-PNP could be a consequence of either (1) activation by ATP of MCANS also via a mechanism dependent on ATP hydrolysis or (2) a lower affinity of the ATP binding site for AMP-PNP, which therefore exerts a smaller effect at the same concentration. There are differences in the affinity of purines at P2 purinoceptors, although these receptors are activated by binding of extracellular ATP (Surprenant et al. 1996). At present, we cannot discriminate between these possibilities.

Function

The regulation of MCANS by changes in intracellular ATP, coupled with the Ca2+ permeability of the conductance, suggest that it may play a role as a Ca2+ entry pathway in response to a fall in transepithelial Na+ transport. Changes in intracellular Ca2+ have been postulated to play a role in pump-leak coupling between the Na+,K+-ATPase and the K+ channel located on the basolateral membrane of the renal proximal tubule (Messner et al. 1985). Certainly, inhibition of the Na+,K+-ATPase decreases the K+ conductance in rabbit, mouse and frog proximal tubule (Messner et al. 1985; Volkl et al. 1986; Hurst et al. 1993; authors' unpublished observations). One mediator of this inhibition is thought to be a direct inhibition of the channel by the associated increase in intracellular ATP concentration. However, the basolateral K+ channel is also inhibited by the Ca2+-dependent enzyme protein kinase C (Mauerer et al. 1995; Robson & Hunter, 1996, 1997) and a rise in intracellular Ca2+ concentration could, therefore, inhibit the channel by stimulation of protein kinase C activity.

In conclusion, single proximal tubule cells isolated from frog kidney contain an ATP-activated, non-selective cation conductance that is activated in response to inhibition of the Na+,K+-ATPase. Activation of the conductance would be expected to lead to a rise in intracellular Ca2+. The conductance is not sensitive to the tension of the cell membrane, and would not be expected to play a role in the regulation of cell volume. Instead, the conductance appears to be linked to the activity of the Na+,K+-ATPase, and this activity is coupled to that of the K+ channels in the basolateral membrane. Thus the conductance may act as a permissive link between pump and K+ channel activity in the basolateral membrane and form an integral part of the pump-leak mechanism in ion-transporting epithelia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust and the National Kidney Research Fund. Thanks also to Judith Hartley for her excellent technical support.

References

- Bear CE. A nonselective cation channel in rat liver cells is activated by membrane stretch. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;258:C421–428. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.3.C421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS, Breton S, Mairbraul H, Laprade R, Giebisch G. Relationship between sodium transport and intracellular ATP in isolated perfused rabbit proximal convoluted tubule. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:F634–639. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.261.4.F634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chraibi A, Guinamard R, Teulon J. Effects of internal pH on the nonselective cation channel from the mouse collecting tubule. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1995;148:83–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00234159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chraibi A, van den Abbeele T, Guinamard R, Teulon J. A ubiquitous non-selective cation channel in the mouse renal tubule with variable sensitivity to calcium. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;429:90–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02584034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipovic D, Sackin H. A calcium-permeable stretch-activated cation channel in renal proximal tubule. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:F119–129. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.260.1.F119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustin MC, Zhou XL, Martinac B, Kung C. A mechanosensitive ion channel in the yeast plasma membrane. Science. 1988;242:762–765. doi: 10.1126/science.2460920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch clamp techniques for high resolution current recording from cells and cell free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. Isolation of single proximal cells from frog kidneys. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;416:13. P. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. Stretch-activated channels in the basolateral membrane of single proximal cells of frog kidney. Pflügers Archiv. 1990;416:448–453. doi: 10.1007/BF00370753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst AM, Beck JS, Laprade R, Lapointe J-Y. Na pump inhibition downregulates an ATP-sensitive K channel in rabbit proximal convoluted tubule. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264:F760–764. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.4.F760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch J-P, Korbmacher C. Osmotic shrinkage activates nonselective cation (NSC) channels in various cell types. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1999;168:131–139. doi: 10.1007/s002329900503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SA, Ifshin MS, Loo DDF, Diamond JM. Studies of sodium channels in rabbit urinary bladder by noise analysis. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1984;80:135–151. doi: 10.1007/BF01868770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidofsky SD, Sostman A, Fitz JG. Regulation of cation-selective channels in liver cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1997;157:231–236. doi: 10.1007/s002329900231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunaka Y, Tohda H, Hagiwara N, Nakahari T. Antidiuretic hormone-responding nonselective cation channel in distal nephron epithelium (A6) American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:C1513–1522. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.6.C1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauerer UR, Boulpaep E, Segal AS. Regulation of an inwardly rectifying KATP channel on the basolateral membrane of renal proximal tubule. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1995;6:345. [Google Scholar]

- Messner G, Wang W, Paulmichl M, Oberleithner H, Lang F. Ouabain decreases apparent potassium-conductance in proximal tubules of the amphibian kidney. Pflügers Archiv. 1985;404:131–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00585408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka T, Matsuzaki K, Kawahara K, Suzuki K, Hoshino M. Monovalent cation selective channel in the apical membrane of rat inner medullary collecting duct cells in primary culture. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1233:163–174. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)00241-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulais M, Teulon J. A cation channel in the thick ascending limb of Henle's loop of the mouse kidney: inhibition by adenine nucleotides. The Journal of Physiology. 1989;413:315–327. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson L, Hunter M. Volume regulatory responses in frog isolated proximal cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1994a;428:60–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00374752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson L, Hunter M. Volume-activated, gadolinium-sensitive whole cell currents in single proximal cells of frog kidney. Pflügers Archiv. 1994b;429:98–106. doi: 10.1007/BF02584035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson L, Hunter M. Regulation of a barium-sensitive K+ conductance by protein kinase C and A in single proximal tubule cells isolated from frog kidney. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;493.P:68. P. [Google Scholar]

- Robson L, Hunter M. Two K+-selective conductances in single proximal tubule cells isolated from frog kidney are regulated by ATP. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:605–616. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs F. Baroreceptor mechanisms at the cellular level. Federation Proceedings. 1987;46:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgess NC, Carrington CA, Hales CN, Ashford MLJ. Nucleotide-sensitive ion channels in human insulin producing tumour cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1987;410:169–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00581911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surprenant A, Rassendren F, Kawashima E, North RA, Buell G. The cytosolic P2Z receptor for extracellular ATP identified as a P2X receptor (P2X7) Science. 1996;272:735–738. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka T, Suzuki H, Okada H, Hayashi K, Kanno Y, Saruta T. Mechanosensitive cation channels mediate afferent arteriolar myogenic constriction in the isolated rat kidney. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;511:245–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.245bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk T, Fromter E, Korbmacher C. Hypertonicity activates nonselective cation channels in mouse cortical collecting duct cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:8478–8482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkl H, Geibel J, Greger R, Lang F. Effects of ouabain and temperature on cell membrane potentials in isolated perfused straight proximal tubules of the mouse kidney. Pflügers Archiv. 1986;407:252–257. doi: 10.1007/BF00585299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wison GF, Magoski NS, Kaczmarek LK. Modulation of a calcium-sensitive nonspecific cation channel by closely associated protein kinase and phosphatase activities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:10938–10943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Sachs F. Block of stretch-activated ion channels in Xenopus oocytes by gadolinium and calcium ions. Science. 1989;243:1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.2466333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]