Abstract

Intracellular recordings were obtained from neurons in the superfused retina-eyecup preparation of the rabbit under dark-adapted conditions. Neurotransmitter agonists and antagonists were applied exogenously via the superfusate to dissect the synaptic pathways pharmacologically and thereby determine those pathways responsible for the generation of the on-centre/off-surround receptive fields of AII amacrine cells.

Application of the metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist, APB, reversibly blocked both the on-centre and off-surround responses of AII cells. These data were consistent with the idea that both the centre- and surround-mediated responses are derived from inputs from the presynaptic rod bipolar cells.

Whereas rod bipolar cells showed on-receptive fields ≈100 μm across, we found no evidence for an antagonistic off-surround response using light stimuli which effectively elicited the off-surrounds of AII amacrine cells. These results indicated that the surrounds of AII cells are not derived from rod bipolar cell inputs.

Application of the ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists CNQX or DNQX enhanced the on-centre responses of AII cells but attenuated the off-surround responses. These data indicated that the centre- and surround-mediated responses could not both be derived from signals crossing the rod bipolar-to-AII cell synapse.

Application of the glycine antagonist, strychnine, had only minor and variable effects on AII cell responses. However, the GABA antagonists picrotoxin and bicuculline enhanced the on-centre response but attenuated or completely blocked the off-surround response of AII cells. The GABA antagonists had no effect on the responses of horizontal cells indicating that their effects on AII cell responses reflected actions on inner retinal circuitry rather than feedback circuitry in the outer plexiform layer.

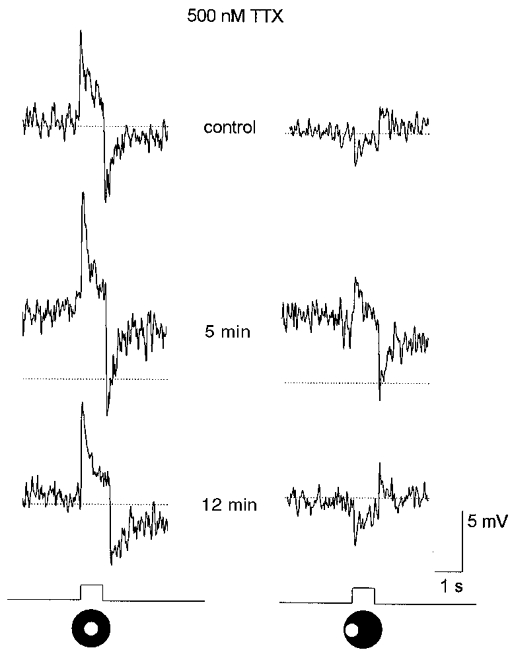

Application of the voltage-gated sodium channel blocker TTX enhanced the on-centre responses of AII cells but attenuated or abolished their off-surround responses.

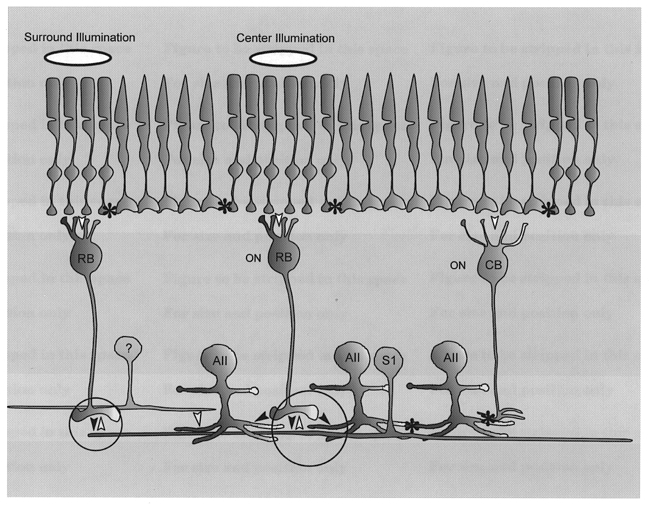

Taken together, our results suggest that the on-centre responses of AII cells result from the major excitatory drive from rod bipolar cells. However, the surround receptive fields of AII cells appear to be generated by lateral, inhibitory signals derived from neighbouring GABAergic, on-centre amacrine cells. A model is presented whereby the S1 amacrine cells produce the surround receptive fields of AII amacrine cells via inhibitory, feedback circuitry to the axon terminals of rod bipolar cells.

It has been nearly 50 years since Kuffler (1953) first described the concentric, antagonistic centre/surround receptive field organization of retinal ganglion cells. In this scheme, illumination of the peripheral or surround portion of a cell's receptive field evokes a response opposite in polarity to that produced by stimulation of the central region. This surround inhibition sharpens ganglion cell spatial tuning and provides for responsiveness to spatial variations in stimulus contrast rather than the absolute level of ambient illumination. Bipolar cells are first in the visual pathways to show centre/surround organization. Their surround inhibition is believed to be generated by the horizontal cells through reciprocal, feedback synapses formed with photoreceptors in the outer plexiform layer (OPL) (Werblin & Dowling, 1969; Baylor et al. 1971; Miller & Dacheux, 1976). In fact, injection of hyperpolarizing current into horizontal cells mimics the effect of surround illumination in both bipolar and ganglion cells (Naka & Nye, 1971; Naka & Witkovsky, 1972; Marchiafava, 1978; Toyoda & Tonosaki, 1978; Mangel, 1991), suggesting that surround inhibition at all levels of the retina may be derived ultimately from the lateral interactions in the OPL.

Amacrine cells are interneurons in the proximal retina forming a second laterally directed inhibitory, synaptic pathway. Although amacrine cells have been thought to be involved mainly in the formation of complex response properties of ganglion cells, such as direction or orientation sensitivity (Dubin, 1970; Caldwell et al. 1978), they have also been implicated in the formation of antagonistic surrounds of certain ganglion cells (Thibos & Werblin, 1978; Caldwell et al. 1978; Jacobs & Werblin, 1998). Recently it was shown that blockade of amacrine cell spike activity with TTX reduces the surround inhibition of some ganglion cells thereby increasing the size of their centre receptive fields (Cook & McReynolds, 1998; Taylor, 1999). These results suggest that the surround receptive fields of certain ganglion cells are mediated, at least in part, by amacrine cells whose activity is spread along the inner plexiform layer (IPL) via voltage-gated sodium channels. Thus, the surround activity of ganglion cells apparently results from a combination of lateral inhibitory circuits laying in both retinal plexiform layers.

The amacrine cells also display antagonistic surround receptive fields similar to that for ganglion cells, yet the circuits responsible for their generation remain entirely unclear. In this study we examined the circuitry subserving the surround inhibition of AII cells, the most abundant subtype of amacrine cell in the mammalian retina (MacNeil & Masland, 1998). In the mammal, rod bipolar cells rarely make synaptic contacts directly onto ganglion cells, but instead synapse mainly onto the dendrites of AII amacrine cells (Famiglietti & Kolb, 1975; Kolb, 1979; Dacheux & Raviola, 1986; Strettoi et al. 1990). The AII amacrine cells thus play a key role in the integration and propagation of rod signals within the retina and display a robust on-centre/off-surround receptive field organization under scotopic light conditions (Nelson, 1982; Dacheux & Raviola, 1986; Bloomfield, 1992; Bloomfield et al. 1997; Xin & Bloomfield, 1999). Fortunately, the input and output circuitry subserving AII amacrine cells has been very well described, making these cells particularly amenable to combined physiological and pharmacological experiments aimed at dissecting the synaptic circuits underlying their centre- and surround-mediated responses. Our results indicate that whereas the centre-mediated responses of AII cells result from excitatory inputs from rod bipolar cells, their antagonistic surrounds arise from lateral inhibition at the level of the IPL. This inhibition is derived from neighbouring GABAergic amacrine cells that provide direct synaptic inputs to AII cells or, more likely, inhibitory feedback to the axon terminals of presynaptic rod bipolar cells.

METHODS

The general methods used in this study have been described previously (Bloomfield & Miller, 1982; Bloomfield et al. 1997). Procedures were in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the Institutional Animal Care Committee at New York University School of Medicine. Adult, Dutch-belted rabbits (1.5-3.0 kg) were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ethyl carbamate (2.0 g kg−1) and a local injection of 2 % lidocaine hydrochloride into the tissue surrounding the eyelids. The eye was removed under dim red illumination and hemisected. The vitreous humour was removed with an ophthalmic sponge and the retina-eyecup was mounted in a superfusion chamber. The chamber was then mounted in a light-tight Faraday cage and superfused at a flow rate of 30 ml min−1 with a mammalian Ringer solution (Bloomfield & Miller, 1982). The superfusate was maintained at 35°C with oxygenation and pH 7.4 maintained by bubbling with a gaseous mixture of 95 % O2-5 % CO2. Following enucleation, animals were killed by an intracardial, bolus injection of ethyl carbamate.

Light stimulation

Two 100 W quartz-iodide lamps provided light for a dual beam optical bench. Light intensity could be reduced up to 7 log units with calibrated neutral density filters placed in the light path of both beams. The maximum irradiance of both beams was equalized at 2.37 mW cm−2. The beams were combined with a collecting prism and focused onto the vitreal surface of the retina-eyecup by means of a final focusing lens.

The bottom beam provided small concentric spot stimuli (50 μm to 6.0 mm diameter), as well as a 50 μm wide, 6.0 mm long rectangular slit of light which was moved along its minor axis (parallel to the visual streak) in steps as small as 3 μm. Alignment of the electrode tip with stimuli was accomplished visually with the aid of a dissecting microscope mounted in the Faraday cage. However, after impaling a cell, the spot stimulus which evoked the largest amplitude centre-mediated response was considered centred over the cell and adjustment of stimuli position was made accordingly. All retinas were left in complete darkness for at least 45 min prior to recording. In the search for cells, light stimuli of log-6.0 or log-5.5 intensity (approximately 1 log unit above rod threshold) were presented only once every 10 s to limit any light adaptation.

Electrical recordings

Intracellular recordings were obtained with microelectrodes fashioned from standard borosilicate glass tubing (Sutter Instruments). Electrodes were filled at their tips with 4 %N-(2-amino-ethyl)-biotinamide hydrochloride (Neurobiotin, Vector Laboratories), in 0.1 M Tris buffer (pH 7.6) and then back filled with 4 M potassium chloride. Final DC resistances of electrodes ranged from 250–450 MΩ. Following physiological characterization of a cell, Neurobiotin was iontophoresed into the neuron using a combination of sinusoidal (3 Hz, 0.8 nA peak to peak) and direct (0.4 nA) currents applied simultaneously; this method allowed passage of tracer through the electrode without polarization. Recordings were displayed on an oscilloscope, recorded on magnetic tape, and digitized off-line for computer analyses. For pharmacological studies, drugs were applied by switching from the control solution described above to one containing a known concentration of drug. Drugs and their sources were: D,L-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (APB) (Tocris Cookson); 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), 6,7-dinitoquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX) and (5R,10S)-(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine hydrogen maleate (MK-801) (Research Biochemicals International); picrotoxin, (-)-bicuculline methochloride and tetrodotoxin (TTX) (Sigma).

Histology

One hour after labelling the last cell in an experiment, the retina was fixed in a cold (4°C) solution of 4 % paraformaldehyde-0.1 % glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.3) for 12 min. The retina was then detached, trimmed, and fixed onto a gelatinized glass coverslip and left in fixative overnight at 4°C. Retinas were then washed in phosphate buffer and reacted with the Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) and 1 % Triton X-100 in 10 mM sodium phosphate-buffered saline (9 % saline, pH 7.6). Retinas were subsequently processed for peroxidase histochemistry using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) with cobalt intensification. Retinas were then dehydrated, cleared, and flatmounted for light microscopy.

RESULTS

This report includes data from intracellular recordings of 102 AII amacrine cells, 8 rod bipolar cells, 10 A-type and 12 B-type horizontal cell somatic and axon terminal endings. All impalements were made in and around the visual streak region with the most peripheral recording made 2.5 mm from the optic disc. All neurons were injected with Neurobiotin and thereby classified based on established morphological criteria. For AII amacrine cells, these criteria included relatively large somata in the proximal portion of the inner nuclear layer (INL) and the distinctive bistratified dendritic architecture consisting of lobular appendages in sublamina a and finer dendrites stratifying primarily in stratum 5 of the IPL (Famiglietti & Kolb, 1975; Kolb, 1979; Strettoi et al. 1992). Rod bipolar cells were identified by their numerous dendritic branchlets penetrating relatively deep into the OPL and a stout axon giving rise to terminal lobes arborizing in the most vitreal portion (stratum 5) of the IPL (Famigletti & Kolb, 1975; Dacheux & Raviola, 1986; Strettoi et al. 1990). The A- and B-type horizontal cells were easily identified by their characteristic soma-dendritic morphology (Fisher & Boycott, 1974; Bloomfield & Miller, 1982; Dacheux & Raviola, 1982). In particular, the B-type horizontal cells were identified by their oval somata in the distal IPL from which five to seven thin, lacy dendrites emerged to from a symmetrical, overlapping dendritic field and a thin axon ran several hundred micrometres before enlarging into an elaborate terminal arborization. Although Neurobiotin could effectively move across the connecting axon, a different but characteristic coupling pattern was seen when injections were made into the somatic or axon terminal endings (see Vaney, 1993,1994; Mills & Massey, 1994; Bloomfield et al. 1995), thereby enabling us to determine the site of impalement of B-type horizontal cells.

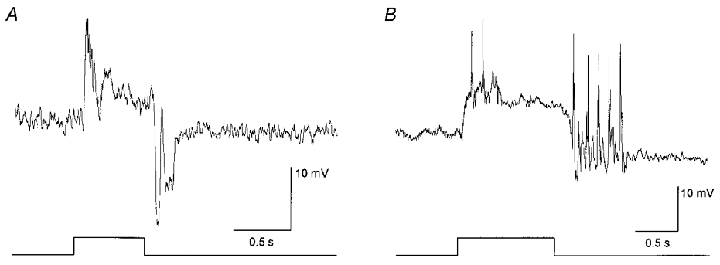

AII amacrine cell receptive fields

In dark-adapted retinas, AII amacrine cells showed on-centre responses to small spot illumination typically consisting of a transient depolarization at light onset followed by a sustained component and a large, oscillating hyperpolarization at light offset (Fig. 1A). Although the amplitude of individual components varied, this general response waveform was stereotypic of all dark-adapted AII cells. The AII cells showed an average resting (dark) membrane potential of -42 mV. On occasion, AII cell responses incorporated rapid, spike-like waves (Fig. 1B). These waves were abolished by application of TTX and thus reflected activity of voltage-gated sodium channels (see Boos et al. 1993).

Figure 1. Light-evoked responses of AII amacrine cells in the dark-adapted retina.

A, typical response consists of a transient depolarization at light onset followed by a sustained phase and a large-amplitude, oscillating hyperpolarization at light offset. Stimulus is a 75 μm diameter spot of light. Stimulus intensity, log-5.5; maximum intensity (log0.0 = 2.37 mW cm−2). Trace at bottom indicates onset and offset of the light stimulus. B, on occasion spike-like waves could be seen in the responses of AII amacrine cells. These spikes could be abolished with TTX indicating that they are generated by voltage-gated sodium channels. Stimulus parameters are the same as in A.

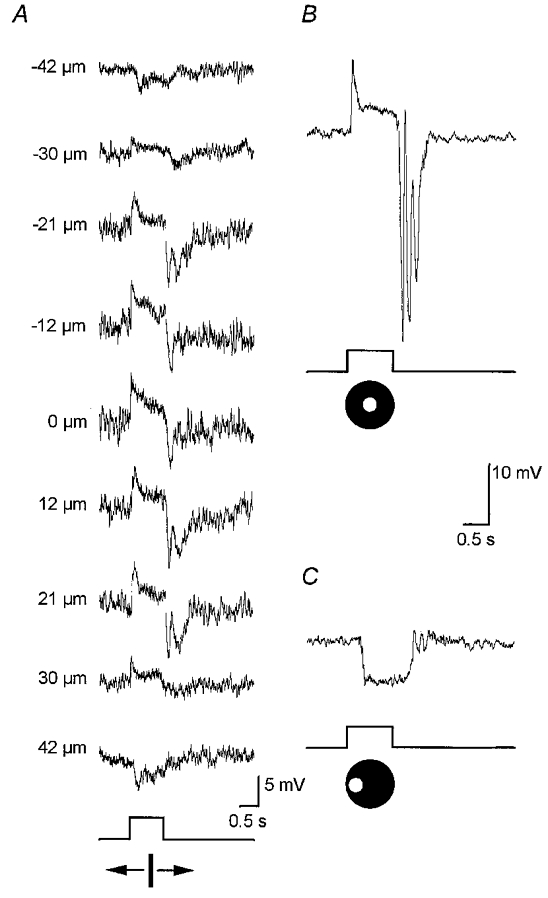

AII amacrine cells in the dark-adapted rabbit retina also showed prominent antagonistic surround receptive fields. Figure 2A shows the results of an experiment in which the stimulus was a 50 μm wide, 6.0 mm long slit of light which was initially centred over an impaled AII cell (0 μm) and then was displaced across the retina surface in discrete steps. When centred over the cell, the slit evoked a clear on-centre response which decreased in amplitude as the slit was stepped in either direction. However, the on-centre response was replaced by a clear light-evoked hyperpolarization, reflecting an antagonistic off-surround response, when the slit was positioned at ±42 μm from the centre of the cell. The total extent of this cell's on-centre receptive field was measured to be 66 μm across, whereas the off-surround receptive field extended to ∼100 μm. The centre- and surround-mediated responses of AII cells could also be evoked and isolated by lateral displacement of a centred, small spot stimulus (Fig. 2B and C). Large spots of light, which simultaneously stimulated both centre and surround receptive fields, typically evoked only weak on-centre responses due to the cancelling effects of the opposing membrane polarizations.

Figure 2. Receptive field properties of dark-adapted AII amacrine cells.

A, responses to a 50 μm wide, 6.0 mm long rectangular slit of light which was moved in discrete steps across the retinal surface. At 0 μm the slit was centred over the cell. The values to the left of each trace represent how far off-centre the slit was positioned; polarity of number indicates direction of movement. This cell showed an on-centre receptive field measured at 66 μm across. Stimulus intensity, log-5.5. Trace at bottom indicates presentation of light stimulus. B, on-centre response of an AII cell to a centred 75 μm diameter spot of light. Stimulus intensity, log-5.5. C, off-surround response of same AII cell as in B after the spot stimulus was displaced laterally by 100 μm.

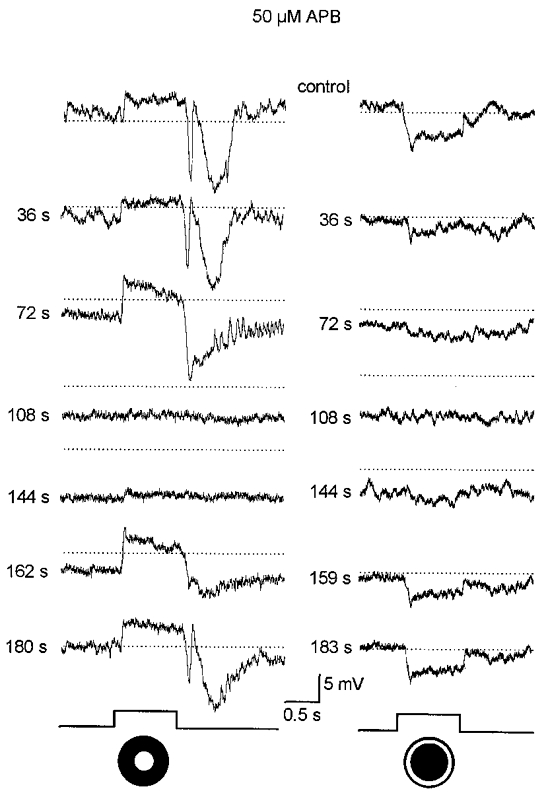

Effects of APB on AII amacrine cells

As mentioned in Introduction, the synaptic circuitry subserved by AII amacrine cells has been well established in the mammalian retina. With this knowledge, we carried out a number of pharmacological experiments aimed at dissecting the circuits responsible for the centre and surround responses of AII cells by applying neurotransmitter agonists and antagonists.

The excitatory synaptic inputs to AII cells are derived from rod bipolar cells (Famiglietti & Kolb, 1975; Kolb, 1979; Dacheux & Raviola, 1986; Strettoi et al. 1990). The glutamatergic synapses between rod bipolar cells and rods express the postsynaptic mGluR6 metabotropic glutamate receptors for which L-APB (L-AP4) is a potent agonist (Slaughter & Miller, 1981; Yamashita & Wässle, 1991; Nakajima et al. 1993). It is well known that, via this site of action, APB effectively blocks the on-centre responses of rod bipolar cells and, in turn, the on-centre responses of neurons in downstream visual pathways (Slaughter & Miller 1981, 1985; Massey et al. 1983; Bloomfield & Dowling 1985a, b). Not surprisingly, application of APB on dark-adapted AII cells reversibly abolished their on-centre responses to focal stimulation (Fig. 3, left panel). This action was coupled with a 5–10 mV hyperpolarization of the dark membrane potential, consistent with the agonistic action of APB on rod bipolar cell receptors in the OPL. APB also reversibly blocked the hyperpolarizing surround-mediated response of AII amacrine cells (Fig. 3, right panel). The time course of the APB effect on the surround-mediated response was virtually identical to that of their centre-mediated response, consistent with a single site of action.

Figure 3. Effects of 50 μM APB on the responses of a dark-adapted AII cell.

Prior to drug application (control), the cell responded to the 75 μm diameter spot of light (left panel) with the typical on-centre response components. Presentation of an annular light stimulus (inner diameter, 75 μm; outer diameter, 350 μm) (right panel) evoked a clear off-surround response. The values to the left of each trace indicate time from the beginning of the 40 s long application of APB; for example, the response at 72 s corresponds to 32 s after return to the control superfusate. APB produced an approximate 10 mV hyperpolarization and reversibly blocked both the on-centre and off-surround responses. Dotted lines correspond to the dark membrane potential during the initial control response and are provided for comparison. Intensity of both spot and annular stimuli, log-5.5. Traces at bottom indicate presentation of light stimuli.

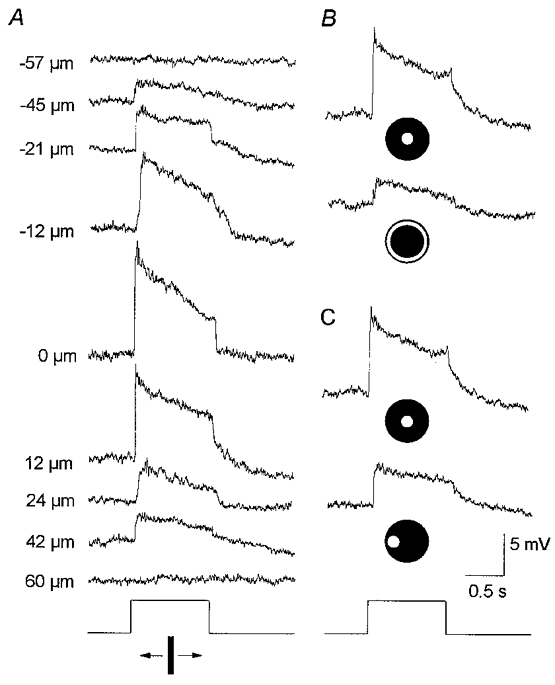

Rod bipolar cell receptive field organization

The results of the experiments with APB were consistent with the idea that both the centre- and surround-mediated responses of AII amacrine cells are derived from presynaptic rod bipolar cells. That is, the actions of APB on AII cells were indirect, reflecting the abolition of centre and surround responses of rod bipolar cells. To examine this idea directly it was necessary to obtain intracellular recordings from rod bipolar cells, a notoriously difficult task (see Nelson et al. 1976; Nelson & Kolb, 1983; Dacheux & Raviola, 1986). Fortunately, we were able to obtain recordings from eight rod bipolar cells which were identified morphologically following labelling with Neurobiotin. Consistent with previous reports (Dacheux & Raviola, 1986; Yamashita & Wässle, 1991) rod bipolar cells showed depolarizing responses to focal stimulation (Fig. 4). The on-centre response consisted of a fast transient depolarization at light onset followed by a declining plateau phase and a rapid return to baseline at light offset; rod bipolar cells did not show the prominent oscillating hyperpolarization seen in the responses of AII amacrine cells at stimulus offset. To determine the spatial profile of rod bipolar cell responses, we used the same narrow slit of light described above for experiments on AII cells. As the slit was displaced from the centre of the cell, the depolarizing response gradually decreased until it was finally lost in the background noise (Fig. 4A). Rod bipolar cells displayed narrow on-receptive fields, averaging 102 μm across. However, in contrast to AII cells, we never detected an antagonistic, hyperpolarizing surround response to peripherally placed slits of light (Fig. 4A). In fact, off-surround-mediated responses could not be detected from rod bipolar cells using annular (Fig. 4B) or translated small spot stimuli (Fig. 4C), both of which were effective in evoking surround responses of AII cells (see Figs 2 and 3). We were unable to evoke a surround response in any of the eight rod bipolar cells we impaled.

Figure 4. Responses of a rod bipolar cell to different stimulus configurations.

A, responses to a 50 μm wide, 6.0 mm long rectangular slit of light moved in discrete steps across the retinal surface. Conventions are the same as in Fig. 2A. The on-centre receptive field was measured to be ≈100 μm across. Stimulus intensity, log-5.5. B, responses to a 75 μm diameter spot of light and an annulus of light (inner diameter, 75 μm; outer diameter, 350 μm). Conventions are the same as in Fig. 3. Both stimuli produced an on-centre response with the annulus failing to produce an off-surround. Stimulus intensity, log-5.5. C, responses to a 75 μm diameter spot of light first centred over the cell and then displaced laterally by 100 μm. Conventions are the same as in Fig. 2B and C. In both cases the spot evoked an on-centre response with the displaced stimulus failing to produce an off-surround response. Stimulus intensity, log-5.5. Taken together, these data indicate that rod bipolar cells do not express off-surround receptive fields.

Effects of glutamate antagonists on AII amacrine cell responses

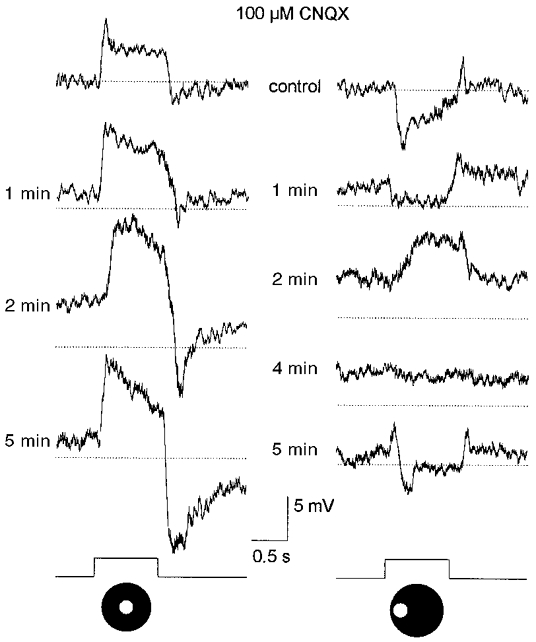

Clearly, our data from rod bipolar cells provide compelling evidence that the surround responses of AII cells are not derived from rod bipolar cells since the latter do not express surround receptive fields. Supporting evidence for this was provided by the results of experiments in which we examined the effect of CNQX (and DNQX), a non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist, on the responses of AII cells. If, in fact, both the centre- and surround-mediated responses of AII cells were derived from rod bipolar cell inputs then we would expect that they both would be abolished by the antagonistic actions of CNQX at the glutamatergic rod bipolar-to-AII cell synapse (cf. Boos et al. 1993; Brandstätter et al. 1997). However, CNQX (or DNQX) displayed differential effects on the centre- and surround-mediated responses. Application of CNQX produced an approximate 5 mV membrane depolarization coupled with a generalized increase in the on-centre responses (Fig. 5, left panel). However, the background noise level was not increased during drug application suggesting that there was not a significant increase in neuronal input resistance. Although this drug-induced enhancement was reversible, it persisted for 8–10 min after returning to the control superfusate. In contrast to the effects on the on-centre response, application of CNQX reversibly abolished the off-surround response of AII cells (Fig. 5, right panel). For some cells, the hyperpolarizing surround response was replaced by a depolarizing one. We believe that this emerging depolarization reflected an on-centre response, due to scatter of light into the centre receptive field, that was no longer masked by the off-surround response. Conversely, however, it may be questioned whether the apparent blockade of the surround-mediated response by CNQX may not have reflected a blockade of the surround at all, but rather an enhanced centre-mediated response, evoked by the light scatter, that obscured the antagonistic surround. If this was the case then the timing of the effects of CNQX on the centre- and surround-mediated responses should have coincided. However, as clearly shown in Fig. 5, the enhancement of the on-centre response outlasted the reduction of the off-surround response. These data suggest, then, that the opposing CNQX effects on the centre- and surround-mediated responses of AII cells reflect actions on different synaptic circuits and are thus inconsistent with the idea that both these responses arise from signals crossing the same synapses between rod bipolar and AII amacrine cells (see Discussion).

Figure 5. Effects of 100 μM CNQX on AII cell responses.

Prior to application of CNQX, a 75 μm diameter spot of light evoked an on-centre response (left panel), whereas the same spot displaced laterally by 100 μm evoked an off-surround response (right panel). Conventions are the same as in Fig. 3. A 40 s application of CNQX produced an approximate 5 mV depolarization and reversibly enhanced the on-centre response to the centred spot of light. CNQX abolished the off-surround response to the displaced spot of light, replacing the hyperpolarizing response with a depolarization. The depolarizing response is believed to be an on-centre response, evoked by light scatter into the centre receptive field, that was revealed after abolition of the off-surround. Note that the drug effects on the off-surround responses were reversed prior to that of the on-centre response. Stimulus intensity, log-5.5. Traces at bottom indicate presentation of the light stimuli.

As mentioned before, previous studies have indicated that ionotropic AMPA/KA receptors reside at the glutamatergic synapse between rod bipolar to AII cells. However, our finding that CNQX did not reduce, but in fact enhanced, the on-centre AII cell response argues that the receptors are not of the AMPA/KA variety or, at least, have atypical pharmacology. We therefore examined the effects of the selective NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 on AII cell responses. Application of 50 μM MK-801 produced a small hyperpolarization of the membrane, reduced the on-centre response by 50–70 % but had no clear effect on the off-surround responses (Fig. 6). We applied MK-801 in concentrations up to 250 μM but the on-centre responses of AII cells were never reduced by greater than 70 % nor did we observe any effect on the off-surround responses.

Figure 6. Effects of 50 μM MK-801 on AII cell responses.

A 40 s application of MK-801 produced an approximate 5 mV hyperpolarization of the membrane and reduced the on-centre response by ≈60 % (left panel) but had no obvious effect on the off-surround response. Stimuli consisted of a 75 μm diameter spot of light centred over the cell (left panel) and then translated laterally by 100 μm (right panel). Stimuli intensity, log-5.5. Drug effects were reversed within approximately 3 min after return to the control superfusate. Conventions are the same as in Fig. 3. Traces at bottom indicate presentation of the light stimuli.

Effects of GABA and glycine antagonists on AII cell responses

Taken together, the aforementioned data suggest that the surround responses of dark-adapted AII amacrine cells are not derived from inputs from rod bipolar cells and therefore must be generated by neuronal circuits within the proximal retina. The most parsimonious mechanism is lateral inhibition derived from neighbouring amacrine cells, either directly onto AII cell dendrites or via feedback synapses onto rod bipolar cell terminals (see Discussion). To explore this possibility we studied the effects of GABA and glycine antagonists, the most common inhibitory transmitters of amacrine cells (Yazulla, 1986; Marc, 1989), on AII cell responses.

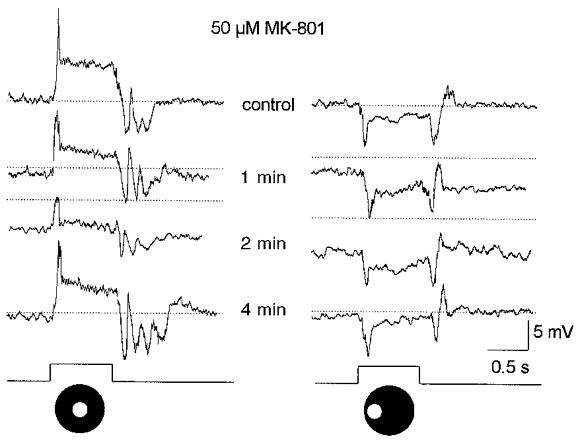

Application of the glycine blocker, strychnine, at concentrations up to 100 μM, produced only minor and variable effects on AII cells: centre and surround responses were either enhanced or reduced by only 5–10 %. In contrast, application of the GABA blockers picrotoxin or bicuculline produced a 4–6 mV depolarization of the dark membrane potential and reversibly enhanced the on-centre responses of AII cells (Fig. 7). In contrast, at concentrations as low as 50 μM, picrotoxin completely abolished the off-surround responses (Fig. 7A). Bicuculline also reduced the off-surround responses but did not completely abolish them even at concentrations as high as 250 μM (Fig. 7B). Although these drugs showed opposite effects on the centre- and surround-mediated responses, the timing of these effects and their reversal were similar (Fig. 7). Overall, the effects of the GABA blockers were qualitatively similar to those described above for CNQX or DNQX.

Figure 7. Effects of GABA antagonists on AII cell responses.

A, a 40 s application of 100 μm picrotoxin produced a 5 mV depolarization of the membrane, enhanced the on-centre response of the AII cell but completely abolished the off-surround response. These drug effects were reversed approximately 3 min after return to the control superfusate. Stimuli consisted of a 75 μm diameter spot of light centred over the cell (left panel) and displaced laterally by 100 μm (right panel). Conventions are the same as in Fig. 3. B, a 40 s application of 100 μM bicuculline also depolarized the membrane by ≈5 mV and enhanced the on-centre response. However, in contrast to the effects of picrotoxin, bicuculline markedly reduced but did not abolish the off-surround response. Stimulus parameters are the same as in A. Traces at bottom indicate presentation of light stimuli.

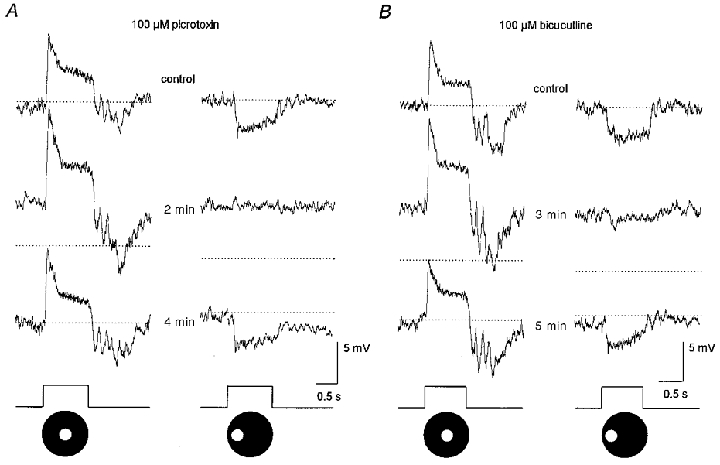

Effects of GABA antagonists on horizontal cell responses

Taken together, the pharmacological studies described above implicate GABAergic inhibition from amacrine cells as the source of the surround responses of AII cells. However, as described in Introduction, a widely held view is that GABAergic feedback synapses from horizontal cells to photoreceptors underlie the surround responses of bipolar cells and, in turn, more proximal neurons. It thus remained possible that the effects of the GABA blockers on AII cell surround responses reflected, at least in part, actions at synapses in the outer retina. We therefore examined the effects of these blockers on horizontal cells responses. We concentrated our studies on B-type horizontal cells since they have axon terminals postsynaptic to rods and thus display prominent rod-driven response components (Bloomfield & Miller, 1982; Dacheux & Raviola, 1982). We found that neither picrotoxin nor bicuculline, at concentrations up to 250 μM, had any appreciable effect on either the dark membrane potential or light-evoked responses of either the somatic or axon terminal endings of B-type horizontal cells (Fig. 8). We also found no effect of these drugs on A-type horizontal cells. These results indicate that the effects of the GABA blockers on AII cell responses did not reflect actions on GABAergic feedback circuitry in the outer retina (see Discussion).

Figure 8. Effects of 100 μM picrotoxin on B-type horizontal cell responses.

A, effects of a 2 min application of picrotoxin on the responses recorded from the somatic ending of a B-type horizontal cell. The drug showed no effect on either the membrane potential or light-evoked responses. Stimulus was full-field illumination with intensity of log-5.5. Conventions are the same as in Fig. 3. B, effects of a 2 min application of picrotoxin on the responses recorded from the axon terminal ending of a B-type horizontal cell. Again, the drug had no clear effects on this cell. Stimulus parameters are the same as in A. Traces at bottom indicate presentation of light stimuli.

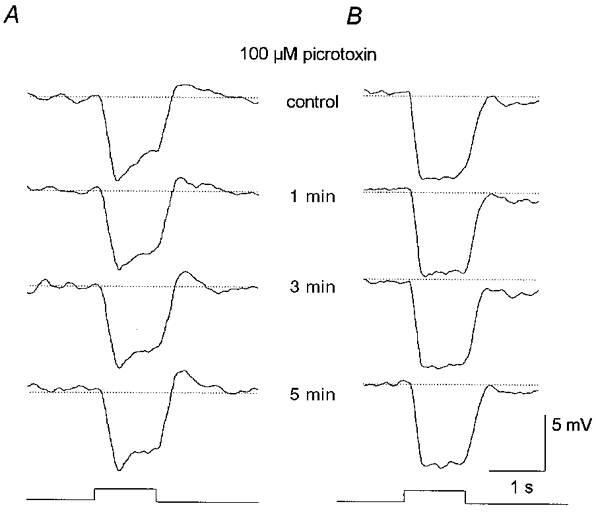

Effects of TTX on AII cell responses

Many amacrine cells in the retina show sodium action potentials which play a clear role in propagating signals across their dendritic arbors (Werblin & Dowling, 1969; Miller & Dacheux, 1976; Cook & Werblin, 1994; Bloomfield, 1996). If lateral inhibition derived from amacrine cells generated the surround responses of AII cells, it follows that the lateral propagation of these signals may have been active, requiring voltage-gated sodium channels. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of blocking these channels with TTX on the responses of AII cells. Application of TTX produced a minor depolarization of the dark membrane potential. This action was coupled with a prominent enhancement of the on-centre response of AII cells and a reduction or total blockade of the off-surround response (Fig. 9). On occasion, as shown in Fig. 9, stimulation of the surround receptive field during TTX application produced a small depolarizing response with waveform similar to the on-centre response. These effects were analogous to those described above for CNQX. Again, we believe that this reflects light scatter into the centre receptive field region that produced a small on-centre response that was unmasked by blockade of the surround response. We applied TTX in concentrations of 0.5-1.0 mM. Although the drug effects were similar at all concentrations, we were able to reverse the effects only to the lowest concentration of drug. Further, the timing of these effects, and their reversal, on the centre- and surround-mediated responses were similar.

Figure 9. Effects of 500 nM TTX on AII cell responses.

A 3 min application of TTX produced a 5 mV depolarization of the membrane and enhanced the on-centre response. TTX also reduced the off-surround response, replacing it with a depolarization with waveform similar to that of the on-centre response, albeit smaller in amplitude. Analogous to the effects of CNQX, we believe that the depolarizing response is an on-centre response, evoked by light scatter into the centre receptive field, that was revealed after reduction or abolition of the off-surround. Stimuli are a 75 μm diameter spot of light centred over the cell (left panel) and displaced laterally by 100 μm (right panel). Conventions are the same as in Fig. 3. Traces at bottom indicate presentation of light stimuli.

DISCUSSION

The AII amacrine cells play a fundamental role in rod vision in that nearly all rod-mediated signals must pass through them first before reaching the ganglion cells and ultimately higher brain regions. Under dark-adapted conditions, AII amacrine cells display robust, antagonistic on-centre/off-surround receptive fields. Our present findings indicate that whereas the centre-mediated responses reflect the dominant excitatory inputs from rod bipolar cells, the surround-mediated responses are derived from inhibitory inputs from neighbouring amacrine cells. These results clearly conflict with the view that the surround receptive fields of proximal neurons are derived from those of the presynaptic bipolar cells (Naka & Nye, 1971; Naka & Witkovsky, 1972; Mangel, 1991). However, recent findings in both amphibian and mammalian retinas indicate that the surround-mediated responses of certain ganglion cells are generated within the inner retina by lateral inhibitory inputs from amacrine cells (Cook & McReynolds, 1998; Taylor, 1999). Our results extend these findings to the amacrine cells, for which AII cells form the most abundant subtype, and thus reveal a novel, additional function for amacrine to amacrine cell interactions.

Although our evidence is circumstantial, there were four major findings in this study that, when taken together, provide strong support for our conclusion that AII cell surround receptive fields are generated in the inner retina. First, we found that rod bipolar cells, the sole conduit for signals between the outer retina and AII cells, did not express antagonistic surrounds. Obviously, then, the surround-mediated responses of AII cells are not generated in the OPL and then simply passed down from rod bipolar cells.

Second, we found that CNQX or DNQX produced opposite effects on the centre- and surround-mediated responses of AII cells, the former being enhanced and the latter attenuated in amplitude. If, in fact, these two types of responses were being passed down across the rod bipolar-to-AII cell synapse then blockade of that single synapse with CNQX should have produced similar inhibitory effects on both responses. These results suggest, then, that AII cell centre- and surround-mediated responses do not arise from the same synaptic circuits (see below).

Third, application of TTX abolished the surround-mediated responses of AII cells. Thus, neurons capable of generating sodium-dependent action potentials must provide key inputs for the generation of AII cell surround responses. These data clearly implicate amacrine cells as the source of these inputs in that many subtypes generate action potentials which play a key role in the propagation of signals across their often extensive dendritic arbors (Cook & Werblin, 1994; Bloomfield, 1996). In this regard it must be remembered that AII cells also display sodium-dependent action potentials and so the TTX effects may have reflected, at least in part, direct effects on AII cells. However, it is difficult to explain how blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels on AII cells alone could have produced opposite effects on the centre- and surround-mediated responses. It is more reasonable to conclude that the TTX effects on AII cell responses reflected, to a large extent, actions on circuits subserved by neighbouring, spiking amacrine cells.

Fourth, the GABA antagonists, picrotoxin and bicuculline, reduced or abolished the surround responses of AII cells. These data also implicate amacrine cells, which form the most common type of GABAergic neuron in the retina. Our finding that GABA antagonists had no effect on the responses of horizontal cells argues against a role for a GABAergic feedback circuit from horizontal cells to photoreceptors in the generation of AII cell surrounds. However, these data do not address the possibility of a GABAergic feedforward circuit from horizontal cells to rod bipolar cells playing a role in the generation of AII cell surrounds (cf. Dowling et al. 1966; Fisher & Boycott, 1974). Nevertheless, this scenario appears extremely unlikely based on the present finding that rod bipolar cells do not express surround receptive fields. Further, such feedforward synapses appear rare in the mammalian retina (Kolb, 1979) and have been shown to have no role in the generation of ganglion cell surround receptive fields (Mangel, 1991).

A circuit model for the generation of AII cell responses

Combining our present results with the well-described circuitry subserved by AII cells we have developed a detailed circuit model for the generation of the centre/surround responses of AII cells (Fig. 10). First, our finding that APB reversibly blocked the on-centre responses is consistent with the idea that these signals arise from inputs from presynaptic rod bipolar cells. However, as shown in the schematic circuit in Fig. 10, rod signals may be communicated to cones via gap junctions that link the two types of photoreceptors. These rod signals can then be passed onto on-centre cone bipolar cells and then to AII cells via gap junctions in the proximal IPL. In fact, DeVries & Baylor (1995) suggested that, by this route, cone bipolar cells are conduits of scotopic signals to ganglion cells with complex receptive fields. In a recent study, however, we showed that uncoupling AII cells from on-centre cone bipolar cells with nitric oxide or cGMP has no effect on the on-centre responses of dark-adapted AII cells, indicating that these signals arise from the chemically mediated synaptic inputs from rod bipolar cells (Xin & Bloomfield, 1999). It was thus surprising and problematic that blockade of the presumed ionotropic glutamate receptors at the rod bipolar-to-AII cell synapse (cf. Boos et al. 1993; Brandstätter et al. 1997) with CNQX or DNQX did not diminish the on-centre responses but actually enhanced them. In contrast, we found that application of the NMDA receptor blocker MK-801 resulted in up to a 70 % reduction in the on-centre response amplitude. Hartveit & Veruki (1997) have provided evidence for NMDA receptors on AII cells, although a recent immunohistochemical study has denied their existence (Fletcher et al. 1999). Thus, although the receptor pharmacology of the glutamatergic rod bipolar-to-AII cell synapse remains unclear, our findings suggest a role for the NMDA subtype. Clearly, further work is called for to decifer the receptor pharmacology at this synapse.

Figure 10. Schematic diagram of synaptic circuitry subserving AII cell centre and surround responses in the dark-adapted retina.

Illumination of the centre receptive field of an AII cell produces an on-centre responses via the rod → rod bipolar cell → AII amacrine cell pathway (large circle). Illumination of the surround receptive field produces an off-surround response by the pathway rod → rod bipolar cell → S1 amacrine cell (small circle) which carries the signal centrally and feeds back via a GABAergic inhibitory (sign inverting) synapse to central rod bipolar cell axon terminals (large circle). Activation of this ‘surround-generating’ circuit shunts the signal in the rod bipolar cell axon terminal thereby reducing the glutamate release onto AII cells and producing the hyperpolarizing off-response. An alternative, but less likely, pathway for surround inhibition may be from unidentified amacrine cells (?) which provide direct inhibitory inputs onto AII amacrine cell dendrites. Asterisks, gap junctions; filled arrowheads, sign-conserving synapse; open arrowheads, sign-inverting synapse; AII, AII amacrine cell; RB, rod bipolar cell; S1, S1 amacrine cell; ON, on-centre.

Again, our findings that picrotoxin and bicuculline reduced or abolished the surround-mediated responses of AII cells indicate that GABAergic inhibition from amacrine cells plays a key role in their generation. Further, the fact that TTX and APB reversibly attenuated or abolished the surround-mediated responses indicates that these inhibitory amacrine cells generate spikes and are of the on-centre variety. The dendrites of AII cells in sublamina b (the on-sublamina) receive a massive chemical input from a homogeneous population of amacrine cell dendritic processes (Strettoi et al. 1992). These inhibitory synaptic profiles from as yet unidentified amacrine cells, represented as the cell with the question mark in Fig. 10, may represent the GABAergic surround inhibition to AII cells. In addition, however, rod bipolar cell axon terminals receive a GABAergic, inhibitory feedback synapse from the S1 (A17) subtype of amacrine cell (Dacheux & Raviola, 1986; Strettoi et al. 1990). We believe that this feedback circuit from S1 cells to rod bipolar cells is probably responsible for the generation of AII cell surround responses for the following reasons. First, the S1 cells receive a dominant, excitatory input from rod bipolar cells and are thereby operational under scotopic light conditions when AII cells express surrounds (Dacheux & Raviola, 1986; Sandell et al. 1989). Second, these amacrine cells are GABAergic (they also accumulate serotonin) with their sole output being the inhibitory feedback to rod bipolar cells (Dacheux & Raviola, 1986; Sandell et al. 1989; Massey et al. 1992). Third, S1 cells display on-centre responses and very large receptive fields, approximately 1 mm across in the visual streak. Interestingly, they do not display an antagonistic off-surround response (Nelson & Kolb, 1985; Dacheux & Raviola, 1986; Bloomfield, 1992). Fourth, these cells generate action potentials.

Thus, the physiological profile of S1 amacrine cells meets all the criteria, as inferred from the present results, for the neuron providing surround inhibition to AII cells. Further, the circuitry subserved by S1 cells is very similar to the horizontal cell-to-photoreceptor feedback circuit in the OPL and is thereby well-suited to form an analogous surround-generating pathway in the proximal retina. Following our model (Fig. 10), stimulation of the surround receptive field of an AII cell gives rise to responses in peripheral rod bipolar cells which excite and elicit the on-responses of neighbouring S1 amacrine cells. These ‘surround’ signals then propagate both passively and actively across the extensive dendritic arbors of S1 cells which activate the GABAergic feedback synapses to more central rod bipolar cells. This GABAergic inhibition shunts the membrane of the rod bipolar axon terminals, thereby decreasing the release of glutamate to the postsynaptic AII amacrine cells. It is this disinhibition of the rod bipolar cells which is seen as the hyperpolarizing surround response of AII cells.

One important caveat to this model is that, to allow for the disinhibition, there must be a tonic release of glutamate from rod bipolar cells to both the postsynaptic AII and S1 amacrine cells in the dark. This, in turn, would provide for a basal release of GABA across the S1-to-rod bipolar cell feedback synapse. Although a controversy presently exists concerning the pattern of vesicular release at bipolar cell terminals, mechanisms of continuous release have been described (Lagnado et al. 1996; Rouze & Schwartz, 1998).

It is interesting to note that although picrotoxin effectively abolished the surround-mediated responses of AII cells, bicuculline reduced but never completely eliminated them. This difference in drug effects may reflect the clustering of GABAA and GABAC receptors at rod bipolar cell axon terminals (Euler & Wässle, 1998; Fletcher et al. 1998). That is, whereas picrotoxin effectively blocked both GABAA and GABAC receptors, the bicuculline-resistive response component may have reflected GABAC receptor-mediated synaptic currents (cf. Lukasiewicz et al. 1994; Qian & Dowling, 1995; Yeh et al. 1996).

According to our model, application of CNQX or DNQX blocked the ionotropic glutamate receptors at the rod bipolar-to-S1 synapse but had little or no effect at the rod bipolar-to-AII cell synapse. This abolished the light-evoked depolarization of S1 cells, diminished the GABAergic feedback inhibition and, in turn, the surround responses of AII cells. Attenuation of this inhibitory feedback signal also resulted in an increased light-evoked release of glutamate from the rod bipolar cell, thus explaining the enhanced centre-mediated response of the AII cell seen following exposure to CNQX. Likewise, application of TTX eliminated the active propagation of signals across S1 cell dendritic arbors, thereby reducing the surround inhibition to rod bipolar cells resulting in attenuated surround-mediated and enhanced centre-mediated responses of AII cells. Finally, APB's blockade of both the centre and surround responses of AII cells reflected actions mediated through two difficult circuits. In this scheme, application of APB blocked the responses of rod bipolar cells, thereby eliminating the direct excitatory drive to postsynaptic AII cells and neighbouring S1 cells and, as a result, the on-centre and off-surround responses of AII cells, respectively.

Are AII cell surround receptive fields unique?

The present results confirm prior reports that AII cells display a robust off-surround receptive field under dark-adapted conditions (Nelson, 1982; Dacheux & Raviola, 1986; Bloomfield et al. 1997). Interestingly, we showed recently that the surround-mediated responses of AII cells vanished following light adaptation of the retina (Xin & Bloomfield, 1999). Thus, AII cell surround responses appear to reflect rod-mediated, but not cone-mediated, signals. This scheme appears opposite to that found for brisk ganglion cells whose surrounds are present under light-adapted conditions and are greatly reduced or abolished by dark adaptation (Barlow et al. 1957; Rodieck & Stone, 1965; Muller & Dacheux, 1997). Thus, the surround receptive fields of AII amacrine cells are not simply imparted to postsynaptic ganglion cells. Instead, the centre/surround organization will dictate how AII cells respond to different spatial stimuli and these responses will, in turn, contribute to the centre receptive field mechanism of dark-adapted ganglion cells.

The surround receptive fields displayed by AII cells thus may be unique in that they appear exclusively under scotopic light conditions. In this regard, it is interesting to note that it is widely believed that the synaptic feedback circuitry from horizontal cells to photoreceptors, again thought responsible for generating the surround responses of retinal neurons, occurs onto cones but not rods (Baylor et al. 1971; Burkhardt, 1977; but see Linberg & Fisher, 1988). Our finding that rod bipolar cells do not display surround-mediated responses is consistent with this idea. In this scheme, the feedback circuitry need only exist for cones since ganglion cell (or bipolar cell) surround responses only occur under light-adapted conditions. This would necessitate different synaptic circuits to generate the rod-driven surround responses of AII cells since the appropriate feedback circuits do not exist in the outer retina. Are then the proposed surround-generating circuits in the inner retina unique to AII cells whereas other amacrine cells rely on feedback circuitry in the OPL to convey cone-mediated surround signals? Clearly, studies of the surround mechanisms of other amacrine cell types will be necessary to answer this question. However, it has been shown recently that lateral inhibition derived from spiking, GABAergic amacrine cells plays an important role in generating the surround responses of certain ganglion cells in the light-adapted amphibian retina (Cook & McReynolds, 1998). Taken together with our present findings, these results suggest that inhibitory circuits subserved by amacrine cells play a major role in creating antagonistic surround receptive fields of inner retinal neurons under both dark- and light-adapted conditions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Grant EY07360 awarded to S. A. Bloomfield and NIH Postdoctoral Fellowship EY06689 awarded to D. Xin. S. A. Bloomfield was the grateful recipient of the Research to Prevent Blindness Miriam and Benedict Wolf Special Scholar Award.

References

- Barlow HB, Fitzhugh R, Kuffler SW. Change of organization of receptive fields of the cat's retina during dark adaptation. The Journal of Physiology. 1957;137:338–354. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor DA, Fuortes MGF, O'Bryan PM. Receptive field of cones in the retina of the turtle. The Journal of Physiology. 1971;214:265–294. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA. Relationship between receptive and dendritic field size of amacrine cells in the rabbit retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;68:711–725. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.3.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA. Effect of spike blockade on the receptive-field size of amacrine and ganglion cells in the rabbit retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;75:1878–1893. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.5.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA, Dowling JE. Roles of aspartate and glutamate in synaptic transmission in rabbit retina. I. Outer plexiform layer. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1985a;53:699–713. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA, Dowling JE. Roles of aspartate and glutamate in synaptic transmission in rabbit retina. II. Inner plexiform layer. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1985b;53:714–725. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.3.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA, Miller RF. A physiological and morphological study of the horizontal cell types in the rabbit retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1982;208:288–303. doi: 10.1002/cne.902080306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA, Xin D, Osborne T. Light-induced modulation of coupling between AII amacrine cells in the rabbit retina. Visual Neuroscience. 1997;14:565–576. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800012220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA, Xin D, Persky SE. A comparison of the receptive field and tracer coupling size of horizontal cells in the rabbit retina. Visual Neuroscience. 1995;12:985–999. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800009524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos R, Schneider H, Wässle H. Voltage- and transmitter-gated currents of AII-amacrine cells in a slice preparation of the rat retina. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:2874–2888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-02874.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandstätter JH, Koulen P, Wässle H. Selective synaptic distributions of kainate receptor subunits in the two plexiform layers of the rat retina. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:9298–9307. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09298.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt DA. Responses and receptive field organization of cones in perch retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1977;40:53–62. doi: 10.1152/jn.1977.40.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JH, Daw NW, Wyatt HJ. Effects of picrotoxin and strychnine on rabbit retinal ganglion cells: lateral interactions for cells with more complex receptive fields. The Journal of Physiology. 1978;276:277–298. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PB, McReynolds JS. Lateral inhibition in the inner retina is important for spatial tuning of ganglion cells. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:714–719. doi: 10.1038/3714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PB, Werblin FS. Spike initiation and propagation in wide-field transient amacrine cells of the salamander retina. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:3852–3861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03852.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacheux RF, Raviola E. Horizontal cells in the retina of the rabbit. Journal of Neuroscience. 1982;2:1486–1493. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-10-01486.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacheux RF, Raviola E. The rod pathway in the rabbit retina: A depolarizing bipolar and amacrine cell. Journal of Neuroscience. 1986;6:331–345. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-02-00331.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH, Baylor DA. An alternative pathway for signal flow from rod photoreceptors to ganglion cells in mammalian retina. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:10658–10662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling JE, Brown JE, Major D. Synapses of horizontal cells in rabbit and cat retinae. Science. 1966;153:1639–1641. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3744.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin M. The inner plexiform layer of the vertebrate retina: a quantitative and comparative electron microscopic analysis. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1970;140:479–506. doi: 10.1002/cne.901400406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euler T, Wässle H. Different contributions of GABAA and GABAC receptors to rod and cone bipolar cells in a rat retinal slice preparation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:1384–1395. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famiglietti EV, Kolb H. A bistratified amacrine cell and synaptic circuitry in the inner plexiform layer of the retina. Brain Research. 1975;84:293–300. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90983-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SK, Boycott BB. Synaptic connections made by horizontal cells within the outer plexiform layer of the cat and the rabbit. Proceedings of the Royal Society. 1974;B 186:317–331. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1974.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher EL, Hack I, Brandstätter JH, Wässle H. Immunocytochemical localization of NMDA receptors in the rat retina. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1999;40:S236. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher EL, Koulen P, Wässle H. GABAA and GABAC receptors on mammalian rod bipolar cells. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1998;396:351–365. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980706)396:3<351::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harveit E, Veruki ML. AII amacrine cells express functional NMDA receptors. NeuroReport. 1997;8:1219–1223. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199703240-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs AL, Werblin FS. Spatiotemporal patterns at the retinal output. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:447–451. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. The organization of the outer plexiform layer in the retina of the cat: electron microscopic observations. Journal of Neurocytology. 1979;6:131–153. doi: 10.1007/BF01261502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuffler SW. Discharge patterns and functional organization of mammalian retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1953;16:37–68. doi: 10.1152/jn.1953.16.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagnado L, Gomis A, Job C. Continuous vesicle cycling in the synaptic terminal of retinal bipolar cells. Neuron. 1996;17:957–967. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linberg KA, Fisher SK. Ultrastructural evidence that horizontal cell axon terminals are presynaptic in the human retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1988;268:281–297. doi: 10.1002/cne.902680211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz PD, Maple BR, Werblin FS. A novel GABA receptor on bipolar cell terminals in the tiger salamander retina. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:1201–1212. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01202.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil MA, Masland RH. Extreme diversity among amacrine cells: implications for function. Neuron. 1998;20:971–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangel SC. Analysis of the horizontal cell contribution to the receptive field surround of ganglion cells in the rabbit retina. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;442:211–234. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc RE. The role of glycine in the mammalian retina. Progress in Retinal Research. 1989;8:67–107. [Google Scholar]

- Marchiafava PL. Horizontal cells influence membrane potential of bipolar cells in the retina of the turtle. Nature. 1978;275:141–142. doi: 10.1038/275141a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey SC, Mills SL, Marc RE. All indoleamine-accumulating cells in the rabbit retina contain GABA. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1992;322:275–291. doi: 10.1002/cne.903220213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey SC, Redburn DA, Crawford MLJ. The effects of 2-amino-4-phosphonobutryric acid (APB) on the ERG and ganglion cell discharge of rabbit retina. Vision Research. 1983;23:1607–1613. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RF, Dacheux RF. Synaptic organization and the ionic basis of on- and off-channels in the mudpuppy retina. I. Intracellular analysis of chloride-sensitive electrogenic properties of receptors, horizontal cells, bipolar cells, and amacrine cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1976;67:639–659. doi: 10.1085/jgp.67.6.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills SL, Massey SC. Distribution and coverage of A- and B-type horizontal cells stained with Neurobiotin in the rabbit retina. Visual Neuroscience. 1994;11:549–560. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800002455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller JF, Dacheux RF. Alpha ganglion cells of the rabbit retina lose antagonistic surround responses under dark adaptation. Visual Neuroscience. 1997;14:395–401. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800011512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka K-I, Nye PW. Role of horizontal cells in the organization of the catfish retinal receptive field. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1971;34:785–801. doi: 10.1152/jn.1971.34.5.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka K-I, Witkovsky P. Dogfish ganglion cell discharge resulting from extrinsic polarization of the horizontal cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1972;223:449–460. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Iwakabe H, Akazawa C, Nawa H, Shigemoto R, Mizuno N, Nakanishi S. Molecular characterization of a novel metabotropic glutamate receptor mGLUR6 with a high selectivity for L-2-amino-4-phosphono butyrate. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:11863–11973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. AII amacrine cells quicken time course of rod signals in the cat retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1982;47:928–947. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.47.5.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R, Kolb H. Synaptic patterns and response properties of bipolar and ganglion cells in the cat retina. Vision Research. 1983;23:1183–1195. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R, Kolb H. A17: A broad-field amacrine cell in the rod system of the cat retina. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1985;54:592–614. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R, Kolb H, Famiglietti EV, Gouras P. Neural responses in the rod and cone systems of the cat retina: Intracellular records and procion stains. Investigative Ophthalmology. 1976;15:946–953. [Google Scholar]

- Qian H, Dowling JE. GABAA and GABAC receptors on hybrid bass retinal bipolar cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;74:1920–1928. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.5.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodieck RW, Stone J. Analysis of receptive fields of cat retinal ganglion cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1965;28:833–849. doi: 10.1152/jn.1965.28.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouze NC, Schwartz EA. Continuous and transient vesicle cycling at a ribbon synapse. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:8614–8624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08614.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell JH, Masland RH, Raviola E, Dacheux RF. Connections of indoleamine-accumulating cells in the rabbit retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1989;283:303–313. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter MM, Miller RF. 2-Amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid: a new pharmacological tool for retina research. Science. 1981;211:182–185. doi: 10.1126/science.6255566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter MM, Miller RF. Characterization of an extended glutamate receptor of the ON bipolar neuron in the vertebrate retina. Journal of Neuroscience. 1985;5:224–233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-01-00224.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strettoi E, Dacheux RF, Raviola E. Synaptic connections of rod bipolar cells in the inner plexiform layer of the rabbit. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;295:449–466. doi: 10.1002/cne.902950309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strettoi E, Dacheux RF, Raviola E. Synaptic connections of the narrow-field, bistratified rod amacrine cell (AII) in the rabbit retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1992;325:152–168. doi: 10.1002/cne.903250203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WR. TTX attenuates surround inhibition in rabbit retinal ganglion cells. Visual Neuroscience. 1999;16:285–290. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899162096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibos LN, Werblin FS. The properties of surround antagonism elicited by spinning windmill patterns in the mudpuppy retina. The Journal of Physiology. 1978;278:101–116. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda J-I, Tonosaki K. Effect of polarization of horizontal cells on the on-centre bipolar cell of carp retina. Nature. 1978;276:399–400. doi: 10.1038/276399a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaney DI. The coupling pattern of axon-bearing horizontal cells in the mammalian retina. Proceedings of the Royal Society. 1993;B 252:501–508. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1993.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaney DI. Patterns of neuronal coupling in the retina. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 1994;13:301–355. [Google Scholar]

- Werblin FS, Dowling JE. Organization of the retina of the mudpuppy. Necturus maculosus. II. Intracellular recording. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1969;32:339–355. doi: 10.1152/jn.1969.32.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin D, Bloomfield SA. Comparison of the responses of AII amacrine cells in the dark- and light-adapted rabbit retina. Visual Neuroscience. 1999;16:653–665. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899164058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M, Wässle H. Responses of rod bipolar cells isolated from the rat retina to the glutamate agonist 2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (APB) Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:2372–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-08-02372.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazulla S. GABAergic mechanisms in the retina. Progress in Retinal Research. 1986;6:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh HH, Grigorenko EV, Veruki ML. Correlation between a bicuculline-resistant response to GABA and GABAA receptor rho-1 subunit expression in single rat retinal bipolar cells. Visual Neuroscience. 1996;13:283–292. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800007525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]