Abstract

Stretch-activated channels (SACs) were studied in isolated rat atrial myocytes using the whole-cell and single-channel patch clamp techniques. Longitudinal stretch was applied by using two patch electrodes.

In current clamp configuration, mechanical stretch of 20 % of resting cell length depolarised the resting membrane potential (RMP) from -63·6 ± 0·58 mV (n = 19) to -54·6 ± 2·4 mV (n = 13) and prolonged the action potential duration (APD) by 32·2 ± 8·8 ms (n = 7). Depolarisation, if strong enough, triggered spontaneous APs. In the voltage clamp configuration, stretch increased membrane conductance in a progressive manner. The current-voltage (I–V) relationship of the stretch-activated current (ISAC) was linear and reversed at -6·1 ± 3·7 mV (n = 7).

The inward component of ISAC was abolished by the replacement of Na+ with NMDG+, but ISAC was hardly altered by the Cl− channel blocker DIDS or removal of external Cl−. The permeability ratio for various cations (PCs:PNa:PLi = 1·05:1:0·98) indicated that the SAC current was a non-selective cation current (ISAC,NC). The background current was also found to be non-selective to cations (INSC,b); the permeability ratio (PCs:PNa:PLi = 1·49:1:0·70) was different from that of ISAC,NC.

Gadolinium (Gd3+) acted on INSC,b and ISAC,NC differently. Gd3+ inhibited INSC,b in a concentration-dependent manner with an IC50 value of 46·2 ± 0·8 μM (n = 5). Consistent with this effect, Gd3+ hyperpolarised the resting membrane potential (-71·1 ± 0·26 mV, n = 9). In the presence of Gd3+ (0·1 mM), stretch still induced ISAC,NC and diastolic depolarisation.

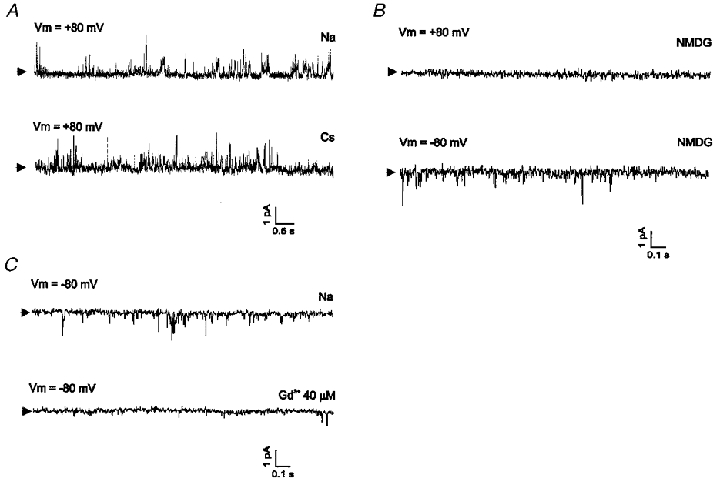

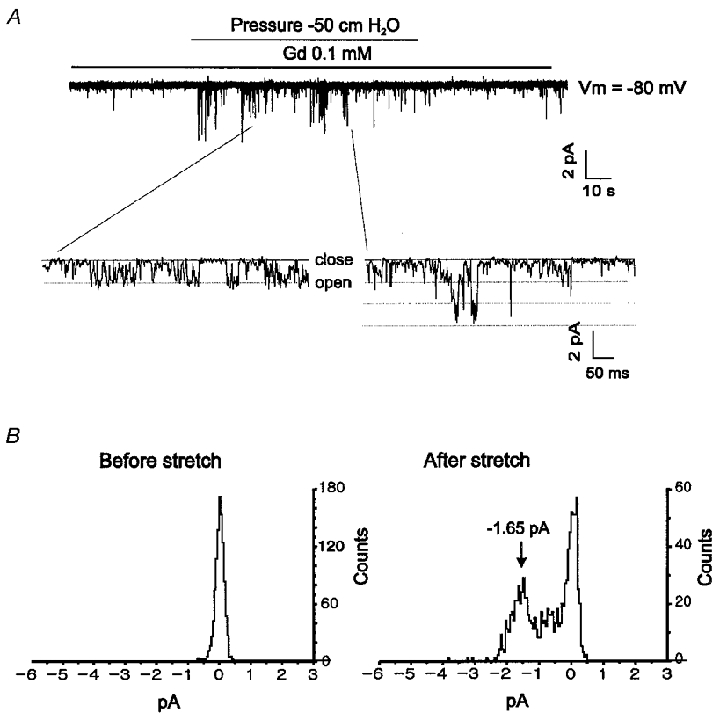

Single-channel activities were recorded in isotonic Na+ and Cs+ solutions using the inside-out configuration. In NMDG+ solution, outward currents were abolished. Gd3+ (100 μM) strongly inhibited channel opening both from the inside and outside. In the presence of Gd3+ (100 μM) in the pipette solution, an increase in pipette pressure induced an increase in channel opening (21·27 ± 0·24 pS; n = 7), which was distinct from background activity.

We concluded from the above results that longitudinal stretch in rat atrial myocytes induces the activation of non-selective cation channels that can be distinguished from background channels by their different electrophysiology and pharmacology.

It is well known that myocardial stretch causes changes in electrical signalling and contractility of the heart and the presence of a mechano-electric feedback mechanism has been proposed (Lab, 1982). For example, mechanical stretch depolarises the membrane potential of cardiac cells and alters the shape of action potentials (APs) (Hansen et al. 1991; Sasaki et al. 1992; Hu & Sachs, 1997; Kohl et al. 1999). As a result, these effects either accelerate the frequency of heart rate or induce arrhythmias of the heart (Stacy et al. 1992; Kohl et al. 1999). Mechanical stress also causes molecular transformations: stretching of cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes increases gene expression, for example, pro-oncogene expression and protein synthesis (hypertrophy) (Komuro et al. 1990; Sadoshima & Izumo, 1997). In addition, atrial natriuretic peptide, which is known to be synthesised and stored in the atrium, is secreted in response to local atrial wall stretch (de Bold, 1985; Lang et al. 1985; Ruskoaho, 1992). Several intracellular signalling mechanisms have been shown to be activated by mechanical stretch, including phospholipases, tyrosine kinases, mitogen-activated protein kinases, etc. (Vandenburgh, 1992; Sadoshima & Izumo, 1993). However, little is known about how mechanical stretch is sensed and transduced into intracellular signals, to bring about its effects.

Since stretch-activated channels (SACs) were first identified in cultured skeletal muscle cells (Guharay & Sachs, 1984), many different types of SAC have been reported in a wide variety of cells (Sackin, 1995; Hu & Sachs, 1997). In the cardiac cell, several types of SAC have been described: potassium-selective channels (Sigurdson et al. 1987), ATP-sensitive potassium channels (Van Wagoner & Russo, 1992), Cl−-selective anion channels (Sorota, 1991; Tseng, 1992; Hagiwara et al. 1992b; Zhang et al. 1993) and non-selective cation channels (Kim, 1993; Kim & Chen, 1993; Ruknudin et al. 1993; Hoyer et al. 1994). In the above studies, SACs were activated by application of negative or positive pressure to the patched membrane, or by application of hyposmotic solutions to induce volume increase. It is, however, not certain whether pressure and volume stress can be regarded as similar mechanical stimuli under physiological conditions. In order to understand the contribution of SACs to stretch-induced responses of cardiac myocytes, it is necessary to characterise the type of channel activated by direct mechanical stretch.

In the present study, we applied direct stretch to rat atrial myocytes using two patch pipettes attached to either end of the cell. Using one of the electrodes, the whole-cell patch clamp technique was performed. We found that stretch of cells resulted in depolarisation of the membrane potential and an increase in membrane current. The increase in current was proportional to the degree of cell stretch, and electrophysiological characteristics suggested that the ionic nature of this current was non-selective to cations. Since a non-selective cation current is known to be present as a background current (Hagiwara et al. 1992a; Mubagwa et al. 1997), we further investigated whether the stretch- activated non-selective cation channel (SACNC) and the background non-selective cation (NSCb) channel were the same or different channels.

METHODS

Preparation of single atrial myocytes

Atrial myocytes were isolated from Sprague-Dawley adult rats (200-250 g). All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee for Animal Experiment Guide of the College of Medicine, Seoul National University. The rats were killed by cervical dislocation and the hearts removed quickly for connection to a Langendorff perfusion system. After washing with 100 ml of normal Tyrode solution, nominal Ca2+-free Tyrode solution was applied for 8 min, followed by 10–13 min perfusion with Tyrode solution containing 5 μM Ca2+ and 50 u ml−1 collagenase (Yakult, Japan). After enzyme perfusion, both right and left atria and appendages were trimmed off and dissected into small pieces in high-K+, low-Cl− storage medium (Kraft-Brühe; KB medium). The pieces were then dissociated by gentle agitation with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette in fresh KB medium. The isolated single cells were kept at 4°C for subsequent experiments. All experiments were performed at room temperature.

Solutions and chemicals

For the experiments under control conditions, a normal Tyrode external solution and a high-K+ pipette solution were used. The normal Tyrode solution contained (mM): 143 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 11 glucose, 5 Hepes, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The high-K+ pipette solution contained (mM): 140 KCl, 10 Hepes, 1 MgCl2, 5 MgATP, 2.5 ditris-phosphocreatine, 2.5 disodium phosphocreatine, 5 EGTA, titrated to pH 7.3 with KOH. Nystatin (0.2 mg ml−1) was added to the pipette solution to obtain the perforated patch in current clamp experiments. To study the ionic nature of the non-selective cation currents, the internal and external solutions were changed to NaCl-containing solutions to minimise voltage-activated K+ and Ca2+ currents. External NaCl solution contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Nicardipine (10 μM) was added to block the permeation of Na+ through Ca2+ channels. NaCl was replaced with LiCl, CsCl or N-methyl-D-glutamate (NMDG)-Cl in certain experiments, where indicated (pH titrated to 7.4 with LiOH, CsOH or HCl, respectively). Internal NaCl solution contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 10 Hepes, 1 MgCl2, 5 MgATP, 2.5 ditris-phosphocreatine, 2.5 disodium phosphocreatine, 5 EGTA, titrated to pH 7.3-7.4 with NaOH. Internal NaCl was replaced with CsCl or NMDG-Cl in some experiments, for the determination of cation selectivity. In single-channel experiments, ATP, phosphocreatines and EGTA were omitted from the above solutions. KB medium contained (mM): 70 KOH, 40 KCl, 50 L-glutamic acid, 20 taurine, 20 KH2PO4, 3 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 Hepes, 0.5 EGTA (pH titrated to 7.4 with KOH). All chemicals were obtained from Sigma, except gadolinium chloride (Aldrich).

Electrophysiological recordings

The standard whole-cell voltage clamp technique was used to record membrane currents, and the nystatin-perforated patch current clamp technique to record membrane potentials and APs from single atrial myocytes. Recording electrodes were pulled from 1.5 mm o.d. and 1.17 mm i.d. glass (Clark Electromedical Instruments, Pangbourne, UK) using a Narishige puller (PP-83, Japan). Pipette resistance varied from 2 to 4 MΩ. An Axopatch-1C patch clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments) was used for voltage and current clamp experiments. Inward current (5 nA, 2 ms) was injected through the pipette to elicit APs. Recordings were shown on an oscilloscope (PM-3335, Philips) during the experiments and displayed on a chart recorder (Gould, USA). Data were low-pass filtered at 2–3 kHz, digitised at a sampling rate of 5–10 kHz using an analog-to-digital converter (Digidata, Axon Instruments) and stored on the hard disk of an IBM-compatible computer for later analysis using pCLAMP 6.0 software (Axon Instruments). The liquid junction potential was -6 mV between the external normal Tyrode solution and the internal K+-rich pipette solution; this was not corrected for in the data. A 3 M KCl-agar bridge electrode was used as the reference electrode. Cell capacitance was compensated after the whole-cell mode was obtained. Data are presented as means ±s.e.m. (n, number of cells).

Single-channel recordings were made using the inside-out patch clamp technique. Pipette resistance ranged between 3 and 5 MΩ and pipettes were coated with Sylgard. Data were filtered at 1 kHz (cut-off frequency at -3 dB points). In single-channel analysis, the threshold of opening transition was set at one-half of the unitary current.

Application of mechanical stretch

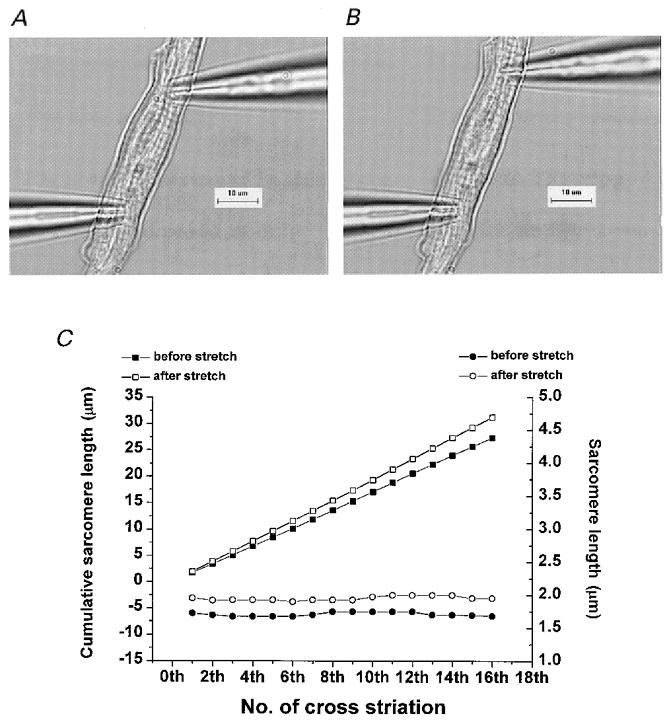

Mechanical stretch was applied directly using two patch electrodes, following a method modified from Davis et al. 1992 and Wellner & Isenberg (1994). One electrode was placed at one end of the cell and used for conventional whole-cell patch clamp recording. The other electrode was sealed to the opposite end, as shown in Fig. 1A. Stretch was applied via longitudinal displacement of the second electrode, using a hydraulic micromanipulator (Narishige, Japan) (Fig. 1B). The extent of stretch was expressed as the percentage change in cell length (L) relative to the original length:

In order to test whether the displacement of one electrode causes the uniform stretch of the cell, we examined the change in sarcomere length (SL) after stretch was applied. SL was measured from the distance between cross-striations and each length was plotted (Fig. 1C, circles) together with cumulative SL (Fig. 1C, squares). The value of SL of each sarcomere was relatively uniform, and a linear relationship of cumulative SL also indicates that the arrangement of cross-striations was uniform. When the upper electrode was moved by 15 % of the original distance, the cell was elongated and cross-striations were displaced accordingly. SL increased from 1.70 ± 0.03 to 1.95 ± 0.03 μm following stretch, and the slope of the cumulative SL increased by 15 %. We tested a further 10 cells, and obtained similar responses, indicating that the method used induced a uniform stretch of the cell. However, uniformity of the stretch was affected by the shape of the cell. When the shape of the cell was irregular, the part of the cell where the diameter was larger tended to be stretched to a lesser extent.

Figure 1. Image of an atrial myocyte before and after stretch.

A, image obtained when two patch pipettes were attached at each side of the cell. Cross-striations are visible. B, image obtained after the upper pipette was moved in the longitudinal direction by 15 %. The cell was stretched by movement of the electrode. C, sarcomere length measured from the distance between cross-striations (circles; right y-axis) and its cumulative values (squares; left y-axis) obtained before (closed symbols) and after (open symbols) stretch.

In the case of single-channel recordings, mechanical stretch of a patch of membrane was obtained by application of negative pressure (-50 cmH2O) to the patch pipette.

Results

Effect of mechanical stretch on membrane potential and membrane currents

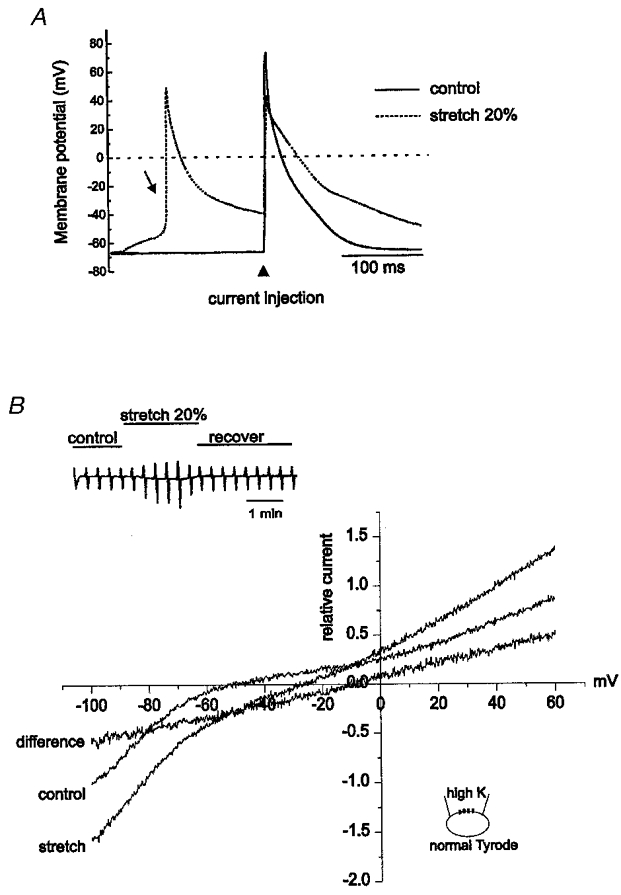

Only rat atrial myocytes with clear striations and well-defined margins were chosen for patch clamp experiments. The shape of the cells was monitored continuously using a CCD camera to ensure that experiments were performed while the shape of the cells remained intact, without swelling or shrinkage. Membrane potentials were recorded in normal Tyrode solution using the nystatin-perforated whole-cell patch clamp technique. Under control conditions, the resting membrane potential (RMP) was -63.6 ± 0.58 mV (n = 19). APs were triggered by application of short current stimuli (5 nA, 2 ms) at 30 s intervals. The action potential duration (APD) measured at 90 % repolarisation was 108.8 ± 11.9 ms (n = 7). When mechanical stretch of about 20 % of resting cell length was applied, the RMP was significantly depolarised to -54.6 ± 2.40 mV (n = 13; Fig. 2A). In 6 of 13 cells, this depolarisation reached threshold, resulting in the firing of spontaneous APs. Stretch-induced APs had a longer duration compared with electrically triggered APs: they were prolonged by 32.2 ± 8.8 ms at 90 % depolarisation (n = 7). The amplitude of mechanically induced APs was slightly decreased, possibly via partial inactivation of sodium channels during the preceding stretch-induced diastolic depolarisation. These changes were reversible and the membrane potential repolarised back to the control level when the cell was returned to its original length. These results suggest that there may be mechanosensitive channels that carry inward currents during diastole.

Figure 2. Effect of longitudinal mechanical stretch on RMP, AP and stretch-activated current (ISAC).

A, direct stretch of the cell by 20 % using two microelectrodes depolarised the RMP. When depolarisation reached threshold, spontaneous APs were elicited (arrow). Current injection during stretch still elicited an AP that was smaller in amplitude and longer in duration (dotted line) compared with control (continuous line). B, I-V relationships of ISAC in normal Tyrode external and high-K+ internal solutions. Left upper inset shows the chart recording of current traces. Currents were elicited by ramp pulses from +60 to -120 mV with dV/dt of -225 mV s−1. The amplitude of the current was normalised to the current measured at -100 mV in control, and normalised I–V curves obtained from 7 cells were averaged. Stretch of the cell by 20 % caused an increase in both the inward and outward currents (from Icontrol to Istretch). The difference between Istretch and Icontrol represents ISAC.

Figure 2B shows whole-cell currents recorded in voltage clamp mode by application of voltage ramps (from +60 to -120 mV; dV/dt =−225 mV s−1) from a holding potential of -30 mV. The amplitude of the current was normalised to the current measured at -100 mV in control and I–V relationships obtained from seven cells were averaged (Fig. 2B). The current-voltage (I–V) relationship in control conditions showed strong inward rectification, which is characteristic for cardiac myocytes. Mechanical stretch induced an increase in membrane current and a positive shift of the reversal potential. The reversal potential was -6.1 ± 3.7 mV (n = 7). This change was completely reversible. The difference current before and after the stretch was regarded as a stretch-activated current (ISAC).

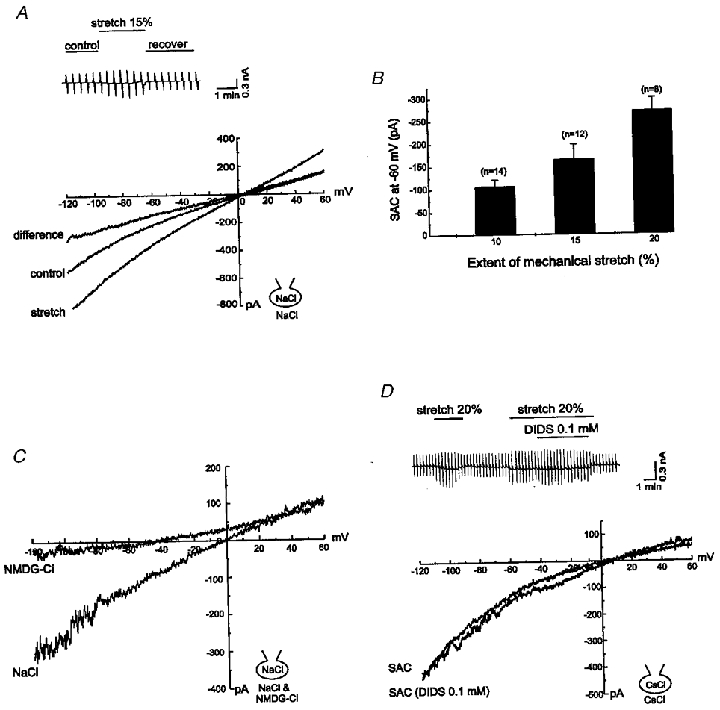

Ionic nature of ISAC

The reversal potential of ISAC implies that ISAC is non-selective to cations. In order to test this hypothesis, we recorded currents in symmetrical Na+ or Cs+ solutions (K+ free and Ca2+ free to eliminate any currents carried by these ions). In symmetrical Na+ solutions, I–V relationships were linear with a reversal potential of 0 mV (Fig. 3A). In symmetrical Cs+ solutions, 100 μM E-4031 was added to block Cs+ permeation through the rapidly activating delayed rectifier K+ channels. Under both conditions, mechanical stretch activated ISAC (Fig. 3A and D). The amplitude of ISAC under these conditions was dependent on the degree of stretch (Fig. 3B). It was not possible to stretch cells to more than 30 % of their resting length since this tended to result in the breakdown of the seal. The application of a Cl− channel blocker (4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS), 0.1 mM, n = 11; Fig. 3D) or replacement of Cl− with aspartic acid (data not shown) did not appear to affect ISAC (n = 3), indicating that a Cl− component is unlikely to contribute to ISAC induced by direct stretch.

Figure 3. Ionic nature of ISAC.

A, I–V relationships of ISAC recorded in symmetrical NaCl solutions. Direct stretch of the cell by 20 % still elicited linear ISAC. Upper inset: chart recording of current traces. B, bar graph of ISAC as a function of the extent of stretch (measured at -60 mV). C, comparison of ISAC when the external solution was changed from solution containing NaCl to solution containing NMDG-Cl. The inward component of ISAC was almost completely abolished while the outward component remained unchanged, suggesting that Na+ was the main carrier. D, I–V relationships of ISAC recorded in symmetrical CsCl solutions before and after treatment with DIDS. Upper inset: chart recording of current traces. Replacement of NaCl with CsCl did not affect the activation, amplitude or I–V relationship of ISAC. ISAC was not affected by 0.1 mM DIDS, indicating that the Cl− channel was not responsible for ISAC.

On the other hand, replacement of external Na+ with non-permeant NMDG+ or TEA+ almost completely abolished the inward component of ISAC with little effect on the outward current (n = 6; Fig. 3C). When permeant cations in internal solutions were completely replaced with NMDG+, the increase in current activated by stretch was apparent only in the inward direction (data not shown).

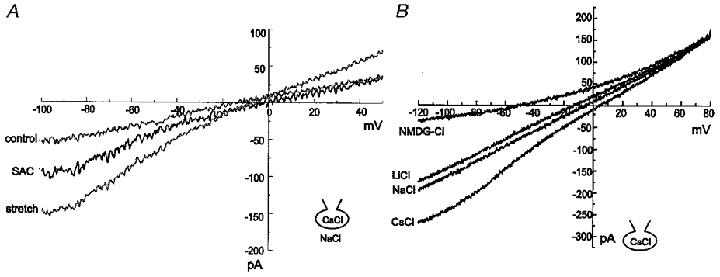

In order to obtain the relative permeability ratio of various cations for ISAC, currents were recorded under biionic conditions and reversal potentials were measured. Figure 4A shows I–V relationships obtained in isotonic [Cs+]i/[Na+]o. Before stretch, the reversal potential was -13 mV. When stretch was applied, the current was increased and the reversal potential was shifted slightly to the right. The I–V relationship of ISAC reversed at about -2 mV. The reversal potential of ISAC was obtained under various ionic conditions, such as [Cs+]i/[Li+]o, [Na+]i/[Cs+]o, [Na+]i/[Li+]o; the reversal potentials obtained were not significantly different. The relative permeability of Na+, Li+ and Cs+ for ISAC was calculated using an equation derived from the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation (Hille, 1992):

| (1) |

where Erev is the reversal potential recorded under biionic conditions, P is permeability and C is the concentration of the permeant ion. Subscripts A and B indicate external and internal cations, respectively. F, R and T are the Faraday constant, gas constant and absolute temperature, respectively. PCs:PNa:PLi was calculated to be 1.05:1:0.98 (n = 5 for Cs+; n = 7 for Li+), indicating that the permeability of Na+ and that of Li+ or Cs+ for ISAC were almost identical. K+ permeability through the SAC could not be determined in isotonic K+ solution because K+ channel currents could not be eliminated completely. Instead, we calculated PK/PNa from the reversal potential of ISAC obtained under normal ionic conditions (Fig. 2B); its value was 1.32. These results clearly indicate that ISAC induced by direct stretch is a non-selective cation current; we refer to this current as ISAC,NC in the following experiments.

Figure 4. Different permeability characteristics of ISAC,NC and INSC,b.

A, I–V relationships of ISAC,NC obtained in 140 mM NaCl external and 140 mM CsCl internal solutions. Mechanical stretch shifted the reversal potential of the current (stretch) slightly to the right. The difference current (SAC) reversed near 0 mV, suggesting that the permeabilities of Cs+ and Na+ for ISAC,NC were almost identical. B, I–V relationships of INSC,b obtained in 140 mM CsCl internal solution with the external solution being changed from solution containing CsCl to solutions containing NaCl, LiCl or NMDG-Cl. Current amplitude was reduced in the inward direction without change in the outward current, and the reversal potential was shifted in a negative direction.

Background non-selective cation current in atrial myocytes

As shown in Fig. 3, the background current before stretch had a linear I–V relationship; this current was not affected by replacement of Cl− with aspartic acid or by DIDS, suggesting the presence of a background non-selective cation current (INSC,b). The shift of the reversal potential by stretch (n = 5; Fig. 4A) suggested a difference in ion selectivity between INSC,b and ISAC,NC. In order to determine the ion selectivity of INSC,b, currents were induced by the same ramp pulses used to record ISAC,NC and the I–V relationship for INSC,b was plotted (n = 6; Fig. 4B). The pipette solution in this experiment contained 140 mM CsCl, and the I–V relationship was linear with a reversal potential of 0 mV in isotonic Cs+ solution. Replacement of external Cs+ with Na+ or Li+ decreased the inward current, along with a shift of the reversal potential in a negative direction. Replacement with NMDG+ resulted in further reduction and only very little inward current remained, indicating that most of the background inward current was carried by cations. From the reversal potential changes under different ionic conditions, the permeability ratio calculated using eqn (1) was PCs:PNa:PLi = 1.49:1:0.70 (n = 6).

Different effects of Gd3+ on ISAC,NC and INSC,b

Gd3+ has previously been reported to block non-selective cation currents and stretch-activated currents in various cell types (Yang & Sachs, 1989; Sackin, 1995). However, in cultured neonatal rat atrial myocytes, Gd3+ was reported not to affect the stretch-activated cation channel (Kim & Chen, 1993). In this study, the effects of Gd3+ on INSC,b and ISAC,NC were investigated. As shown in Fig. 5A, INSC,b was significantly blocked by Gd3+ in a dose-dependent manner. An inhibitory concentration for half-maximum effect (IC50) of 46.2 ± 0.8 μM was obtained (n = 5; Fig. 5B). On the other hand, ISAC,NC was still activated in the presence of Gd3+ (0.1 mM, n = 4), suggesting that ISAC,NC may not be sensitive to Gd3+ (Fig. 6). The different effects of Gd3+ on INSC,b and ISAC,NC were further illustrated in the following experiment in which the effect of Gd3+ on the AP was investigated using the perforated-patch clamp technique (Fig. 7). Application of 0.1 mM Gd3+ to normal Tyrode external solution hyperpolarised the RMP from -63.6 ± 0.58 to -71.1 ± 0.26 mV (n = 9) and shortened the APD markedly (from 108 ± 11.9 to 28.0 ± 2.39 ms, n = 12). Similar results were obtained following pretreatment with nicardipine (2-5 μM) to block L-type Ca2+ channels (data not shown). This result suggests that background non-selective cation (NSCb) channels may contribute to the shape of APs by generating inward currents at the RMP and during the late phase of repolarisation. However, other possibilities cannot be ruled out, considering that the effect of Gd3+ is not selective (Caldwell et al. 1998). On the other hand, mechanical stretch still depolarised the RMP and evoked spontaneous APs in the presence of Gd3+ (0.1 mM, n = 7; Fig. 7B). This result confirmed the results in Fig. 6 showing the insensitivity of ISAC,NC to Gd3+. The different pharmacologies of ISAC,NC and INSC,b indicate that they are carried by distinct populations of non-selective cation channels.

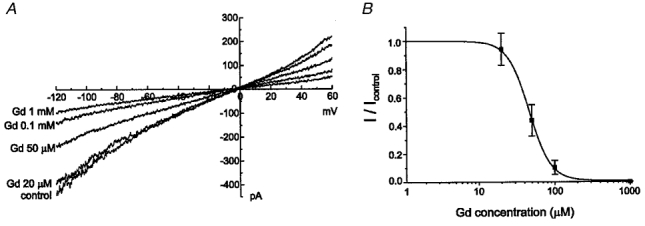

Figure 5. Inhibitory effect of Gd3+ on INSC,b.

A, an increase in the concentration of external Gd3+ subsequently decreased INSC,b. Currents were recorded in symmetrical NaCl solutions. Replacement of Na+ with NMDG+ did not change the residual current suggesting that 1 mM Gd3+ almost completely blocked INSC,b. B, dose-dependence curve of the effect of Gd3+ on INSC,b. Current amplitudes were measured at -80 mV and plotted against the external Gd3+ concentration. The current before application of Gd3+ was normalised as 1.0. The continuous curve was plotted according to the Michaelis-Menten equation: I/Imax = 1/(1 +[Gd3+]/IC50); IC50 = 46.2 ± 0.8 μM.

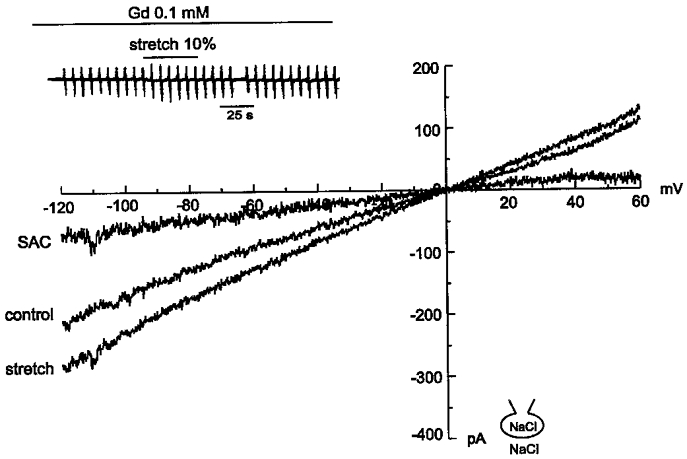

Figure 6. Effect of Gd3+ on ISAC,NC.

ISAC,NC was recorded in the presence of Gd3+ (0.1 mM). Mechanical stretch still increased both inward and outward currents. Upper inset: chart recording of current traces.

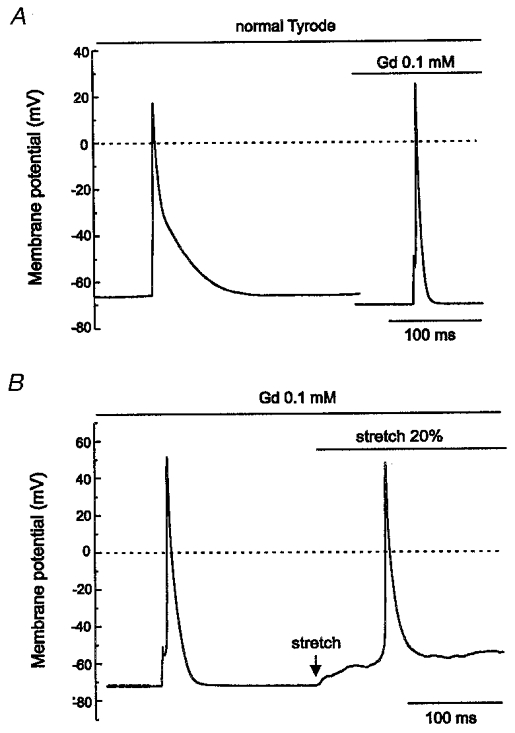

Figure 7. Effect of Gd3+ on AP and stretch-induced depolarisation.

A, in the current clamp configuration, current injection triggered an AP from the RMP of -63.6 ± 0.58 mV. Addition of Gd3+ (0.1 mM) not only hyperpolarised the RMP to -71.1 ± 0.26 mV but also significantly shortened the duration of the AP. B, despite the fact that Gd3+ hyperpolarised the RMP, mechanical stretch still induced depolarisation and this depolarisation triggered spontaneous APs, suggesting that Gd3+ did not block ISAC,NC.

Effect of cytochalasin D

Cytoskeletons are believed to be involved in mechanosensitivity. Cytochalasin D, the actin filament disrupter, has been reported to increase the stretch sensitivity of stretch-activated currents in rat atrial myocytes (Kim, 1993) and in chick skeletal muscle (Kawahara, 1990). The effect of cytochalasin D (20-40 μM) on SACNC is shown in Fig. 8. Exposure to cytochalasin D for 20–30 min did not affect INSC,b (Fig. 8A), but increased the amplitude of ISAC,NC (n = 6; Fig. 8B).

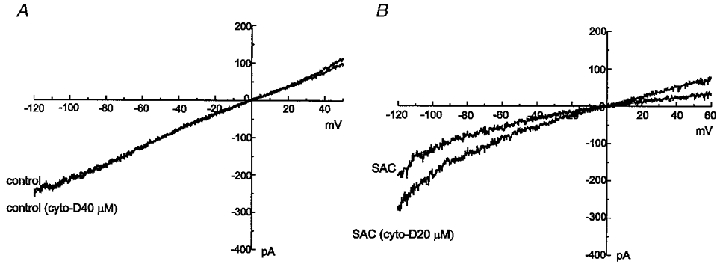

Figure 8. Different effects of cytochalasin D on INSC,b and ISAC,NC.

Cytochalasin D (40 μM) did not change INSC,b recorded in symmetrical NaCl solutions (A); however, cytochalasin D (20 μM) increased ISAC,NC (B).

Single-channel recordings of SACNC and NSCb

We examined whether SACNC and NSCb channels could be identified at a single-channel level using the inside-out patch clamp technique. We could identify single-channel openings in symmetrical NaCl solutions (Fig. 9A). The amplitude of the single-channel current was less than 1 pA at +80 mV. Openings occurred very occasionally and briefly, and systematic analysis was not performed. When isotonic CsCl solution was perfused, single-channel activity was still recorded (Fig. 9A). When the bath solution was changed to isotonic NMDG-Cl solution, the outward currents disappeared, while the inward currents remained unaltered (Fig. 9B). A change of the bath solution to a low-Cl− solution (5.4 mM) did not significantly affect single-channel activity (data not shown). Single-channel activity showing similar characteristics was recorded in 35 out of 48 patches tested; we consider it to correspond to the NSCb channel.

Figure 9. Single-channel recordings of NSCb channels in inside-out patch.

Single-channel currents were recorded under various ionic conditions in inside-out mode. Current signals were acquired with low-pass filtering by an eight-pole Bessel filter at 1 kHz. Vm denotes transmembrane potential. Each arrow indicates the closed level. A, representative recordings obtained with [Na+]i/[Na+]o = 140 mM/140 mM (upper trace) and with [Cs+]i/[Cs+]o = 140 mM/140 mM (lower trace). B, effect of replacement of Na+ in the bath solution with impermeant NMDG+. Outward currents disappeared (upper trace), whereas inward currents remained active (lower trace). C, effect of application of Gd3+ (40 μM) to the bath solution. Single-channel activities recorded with symmetrical Na+ solutions were blocked by Gd3+.

When Gd3+ (40-100 μM) was added to the pipette solution, NSCb single-channel activity was not detected in most of the patches used for recording (n = 33). Gd3+ was also effective at blocking INSC,b when added to the bath solution. NSCb single-channel activity disappeared after addition of Gd3+ to the bath solution (n = 8; Fig. 9C). In the presence of Gd3+ in the pipette solution, however, application of negative pressure (-50 cmH2O for about 3 min) to the pipette induced a dramatic increase in channel opening (Fig. 10A). The pattern of channel opening seemed to be different from that of the NSCb channel, in that openings appeared as a cluster and with larger amplitudes. In Fig. 10B, amplitude histograms obtained before and after stretch are shown. The amplitude of the single-channel current obtained at -80 mV was -1.65 pA, and from this value the single-channel conductance was calculated to be 20.6 pS (mean ±s.e.m. obtained from 7 cells: 21.27 ± 0.24 pS). When Na+ in the bath solution was replaced with NMDG+, only the current in the outward direction was abolished, indicating that the current was carried by cations (data not shown, n = 8). We consider this single-channel activity to correspond to SACNC. These results obtained from single channels correlate well with the results obtained from whole cells and support the hypothesis that NSCb and SACNC are indeed distinct channels.

Figure 10. Single-channel recordings of SACNC in the presence of Gd3+.

A, in symmetrical Na+ solutions, ISAC,NC was still activated by application of negative pressure (-50 cmH2O) in the presence of 0.1 mM Gd3+ in the pipette solution. Membrane potential was held at -80 mV. The lower panel shows expanded traces showing channel flickering. The cut-off frequency was 1 kHz. B, amplitude histograms before and after stretch corresponding to the current traces in A. Histograms correspond to records of 8.19 s. The arrow indicates the peak corresponding to the unit amplitude (1.65 pA).

Discussion

In the present study, we have investigated the properties of currents activated by direct longitudinal stretch in rat atrial myocytes. The ionic nature of ISAC was non-selective to cations. The non-selective cation current activated by stretch (ISAC,NC) was distinguishable from background non-selective cation current (INSC,b) by differences in ion selectivity and pharmacology. These results suggest that SACNC activity is derived not from an increase in NSCb channel activity, but that SACNC and NSCb are different channels.

Method of stretch using two patch electrodes

It is well established that the main stimulus for SAC opening is membrane deformation. Membrane deformation was accomplished in the present study by direct stretch in a longitudinal direction using two patch electrodes, as performed previously by Wellner & Isenberg (1994). We examined the uniformity of stretch by measuring the displacement of cross-striations (Fig. 1), and found that the stretch was applied uniformly. Although the stretch was applied only unidirectionally, we consider that this method mimics the mechanical stimulus imposed on the heart under physiological conditions reasonably well. Another advantage of the direct stretch method is that the degree of stretch is easy to control and quantify. We defined the extent of stretch as a percentage of the difference between the length of the cell before and after stretch. Recovery from the stretched state back to the control level is also simple. However, the technique of application of two electrodes to the cell and maintainance of a tight seal during stretch is difficult, and thus the success ratio is low. Probably due to this technical difficulty, various other protocols have been used to induce membrane deformation and to investigate SACs (Sachs & Morris, 1998), for example, by application of positive or negative pressure through the patch pipette (Guharay & Sachs, 1984), use of a hyposmotic perfusate to cause cell swelling (Ubl et al. 1988) and by increasing and decreasing the pipette pressure to induce cell inflation and deflation, respectively, in the whole-cell mode (Setoguchi et al. 1997).

However, hyposmotic swelling or cell inflation not only causes stretch of the cell membrane, but also induces a change in cell volume. Therefore, the response of the cell to these stimuli could be a response to mechanical stretch of the membrane, volume change, or both. The increase in current induced by hyposmotic solutions in cardiac myocytes was found to be carried by Cl− (Sorota, 1991; Tseng, 1992; Hagiwara et al. 1992b; Zhang et al. 1993), which has similar characteristics to volume-activated Cl− current found in various cell types (Nilius et al. 1994). The present study shows that the Cl− component is not activated by direct stretch, suggesting that membrane deformation by volume change and direct stretch are sensed differently by ion channels. Another problem with this method is that the relationship between the degree of membrane deformation and the intensity of these stimuli is not simple (Sachs & Morris, 1998). The degree of membrane stretch by hyposmotic solutions is expected to be complicated, since volume change of the cell is not proportional to osmolality itself, possibly due to the volume regulation mechanism (Nilius et al. 1995; Sachs & Morris, 1998). The situation is further complicated in cases where second messengers are produced by a volume change (Rothstein & Mack, 1992; Vandorpe et al. 1994; Kim et al. 1995). The problem of volume change can be avoided by the method of applying positive or negative pressure to the patch membrane, and this is widely used for studying SACs at the single-channel level. However, stimulation is restricted to the patch membrane, so the response is also limited within the patch rather than within the whole cell. It seems, therefore, that hyposmotic swelling and pressure application are not appropriate methods when one wishes to investigate the cellular response related to mechanical stimulation in cardiac cells.

Comparison of ISAC,NC and INSC,b

ISAC,NC induced by mechanical stretch in rat atrial myocytes showed a linear I–V relationship from -120 to +60 mV and the reversal potential was near 0 mV under biionic conditions (Fig. 4A), indicating a poor selectivity to various cations (PCs:PNa:PLi = 1.05:1:0.98). This result is similar to those of other studies investigating ISAC,NC in cardiac myocytes (Kim, 1993; Sasaki et al. 1992), smooth muscle cells (Wellner & Isenberg, 1993), endothelial cells (Hoyer et al. 1994; Hu & Sachs, 1997) and liver cells (Bear, 1990). The single-channel conductance of SACNC in this paper (21.27 pS) is similar to previously reported values in vascular smooth muscle cells (23 pS, Davis et al. 1992), atrial cells (21.0 ± 2.2 pS, Kim, 1993) and chick ventricular cells (21 ± 0.9 pS, Hu & Sachs, 1996).

INSC,b was different from ISAC,NC in its permeability characteristics, in that the difference in permeability among ions was larger for INSC,b (PCs:PNa:PLi = 1.49:1:0.70). These values are consistent with those of previous studies (Setoguchi et al. 1997; Bae et al. 1999). The difference between ISAC,NC and INSC,b was further confirmed by pharmacological studies: the response to Gd3+ and cytochalasin D. INSC,b was blocked by Gd3+ in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5), whereas ISAC,NC was not affected significantly by Gd3+ (Fig. 6). This result is consistent with that obtained from cultured neonatal cardiac myocytes (Kim & Chen, 1993) in which Gd3+ did not block SACNC. There are also contradictory reports showing the inhibitory effects of Gd3+ on SACs (Gustin et al. 1988; Yang & Sachs, 1989; Hamill & McBride, 1996). This discrepancy may indicate that SACs in different tissues or in different species are different channels and therefore have distinct pharmacological properties. Therefore, it seems inappropriate to use Gd3+ as a tool for identifying SACs or as a selective blocker of SACs. There are also reports showing that Gd3+ is not a specific blocker of SACs. Gd3+ is known to block other types of channel such as the L-type Ca2+ channel (Sadoshima et al. 1992) or delayed rectifier K+ channels (Hongo et al. 1997).

The cytoskeleton, which is a skeletal component of the myocyte, is known to protect the membrane from tension. The membrane that was attached to or separated from the cytoskeleton showed either hypo- or hyper-mechanosensitivity, respectively, to mechanical stimuli (Hamill & McBride, 1997), suggesting the involvement of the cytoskeleton in the mechanosensitive mechanism. Destruction of the actin filament using cytochalasins increased the stretch sensitivity of SACs in neonatal rat atrial myocytes (Kim & Chen, 1993) and chick skeletal muscle cells (Kawahara, 1990). In our experiments, cytochalasin D increased ISAC,NC without affecting INSC,b channel activity, supporting the idea that ISAC,NC and INSC,b are carried by different channels.

Physiological roles of NSCb and SACNC

Selective permeability to K+ has long been known as the key mechanism underlying the RMP of excitable cells. However, actual values of RMP in most cell types, except ventricular myocytes, are usually less negative than the K+ equilibrium potential, indicating the contribution of inward currents to RMP, counterbalancing K+ outward currents. In sino-atrial cells of the heart (Hagiwara et al. 1992a), and in some smooth muscle cells (Bae et al. 1999) where RMP is around -35 mV, characteristics of the background current and its contribution to RMP have been thoroughly investigated. In the present paper, the contribution of NSCb channels to RMP and the AP plateau in atrial myocytes was suggested in the experiment demonstrating the effect of Gd3+ (Fig. 7). As shown in Fig. 7B, 0.1 mM Gd3+, which almost completely blocks NSCb channels, hyperpolarised the RMP by about 10 mV (from -63.6 ± 0.58 to -71.1 ± 0.26 mV), and shortened the duration of the AP to 28.0 ± 2.39 ms. However, the effects of Gd3+ on channels other than NSCb channels cannot be entirely excluded. For example, Gd3+ can block L-type (Biagi & Enyeart, 1990) and T-type (Lacampagne et al. 1994) Ca2+ channels, and K+ (Hongo et al. 1997) channels. However, since nicardipine did not change the response of the AP to Gd3+, it can be said that the change in AP by Gd3+ was caused by the blockade of a depolarising current other than Ca2+ currents, and that this depolarising current is likely to be INSC,b.

Activation of SACNC induced further depolarisation both under control conditions and in the presence of Gd3+ (Figs 2A and 7B). The result that depolarisation could trigger spontaneous APs (Fig. 2A and 7B) may suggest that activation of SACNC is the mechanism of stretch-induced arrhythmias in cardiac tissue (Stacy et al. 1992). It is also possible that SACNC contributes to other cellular responses induced by stretch, such as gene expression, protein synthesis, secretion and hypertrophy (Sadoshima & Izumo, 1997). The role of SACs in these processes has been suggested (Laine et al. 1994; Sadoshima & Izumo, 1997), but a correlation between SAC activation and these cellular events has not yet been directly investigated.

The significance of the present study relies on the successful recording of SACs using the direct mechanical stretch method with two microelectrodes. To our knowledge, this is the first report investigating the presence and the role of NSCb and SACNC using direct stretch, and presenting direct evidence that NSCb and SACNC are different channels. The presence of different non-selective cation channels may imply different physiological roles for these channels. The physiological and pathophysiological significance of this observation requires further clarification in future studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Basic Medical Research Fund (1995) from the Ministry of Education, a Non Directed Research Fund from the Korea Research Foundation (1996), and grant 03-96-080 from Seoul National University Hospital. We would like to thank Dr A. Levi and Dr A. Hinde for correction of English.

References

- Bae YM, Park MK, Lee SH, Ho W-K, Earm YE. Contribution of Ca2+-activated K+ channels and non-selective cation channels to membrane potential of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;514:747–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.747ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear CE. A nonselective cation channel in rat liver cells is activated by membrane stretch. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;258:C421–428. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.3.C421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagi BA, Enyeart JJ. Gadolinium blocks low- and high-threshold calcium currents in pituitary cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;259:C515–520. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.3.C515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell RA, Clemo HF, Baumgarten CM. Using gadolinium to identify stretch-activated channels: technical considerations. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:C619–621. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MJ, Donovitz JA, Hood JD. Stretch-activated single-channel and whole cell currents in vascular smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:C1083–1088. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.4.C1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bold AJ. Atrial natriuretic factor: a hormone produced by the heart. Science. 1985;230:767–770. doi: 10.1126/science.2932797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guharay F, Sachs F. Stretch-activated single ion channel currents in tissure-cultured embryonic chick skeletal muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1984;352:685–701. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustin MC, Zhou X, Martinac B, Kung C. A mechanosensitive ion channel in the yeast plasma membrane. Science. 1988;242:762–765. doi: 10.1126/science.2460920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N, Irisawa H, Kasanuki H, Hosoda S. Background current in sino-atrial node cells of the rabbit heart. The Journal of Physiology. 1992a;448:53–72. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N, Masuda H, Shoda M, Irisawa H. Stretch-activated anion currents of rabbit cardiac myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1992b;456:285–302. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr The pharmacology of mechanogated membrane ion channels. Pharmacological Reviews. 1996;48:231–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr Induced membrane hypo/hyper-mechanosensitivity: a limitation of patch-clamp recording. Annual Review of Physiology. 1997;59:621–631. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DE, Borganelli M, Stacy GP, Taylor LK. Dose-dependent inhibition of stretch-induced arrhythmias by gadolinium in isolated canine ventricles. Evidence for a unique mode of antiarrhythmic action. Circulation Research. 1991;69:820–831. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.3.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 2. MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hongo K, Pascarel C, Cazorla O, Gannier F, van Guennec J-Y, White E. Gadolinium blocks the delayed rectifier potassium current in isolated guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Experimental Physiology. 1997;82:647–656. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer J, Distler A, Haase W, Gogelein H. Ca-influx through stretch-activated cation channels activates maxi K channels in porcine endocardial endothelium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:2367–2371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Sachs F. Mechanically activated currents in chick heart cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1996;154:205–216. doi: 10.1007/s002329900145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Sachs F. Stretch-activated ion channels in the heart. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1997;29:1511–1523. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara K. A stretch-activated K channel in the basolateral membrane of Xenopus kidney proximal tubule cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1990;415:624–629. doi: 10.1007/BF02583516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Novel cation-selective mechanosensitive ion channel in the atrial cell membrane. Circulation Research. 1993;72:225–231. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Chen F. Activation of a nonselective cation channel by swelling in atrial cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1993;135:27–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00234649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Sladek CD, Aguado-Velasco C, Mathiasen JR. Arachidonic acid activation of a new family of K+ channels in cultured rat neuronal cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;484:643–660. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl P, Hunter P, Noble D. Stretch-induced changes in heart rate and rhythm: clinical observations, experiments and mathematical models. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 1999;71:91–138. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuro I, Kaida T, Shibazaki Y, Kurabayashi M, Katoh Y, Hoh E, Takaku F, Yazaki Y. Stretching cardiac myocytes stimulates protooncogene expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:3595–3598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lab MJ. Contraction-excitation feedback in myocardium. Circulation Research. 1982;50:757–766. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacampagne A, Gannier F, Argibay J, Garnier D, Le Guennec JY. The stretch-activated ion channel blocker gadolinium also blocks L-type calcium channels in isolated ventricular myocytes of the guinea-pig. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1994;1191:205–208. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine M, Arjamaa O, Vuolteenaho O, Ruskoaho H, Weckström M. Block of stretch-activated atrial natriuretic peptide secretion by gadolinium in isolated rat atrium. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;480:553–561. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang RE, Tholken H, Ganten D, Luft FC, Ruskoaho H, Unger T. Atrial natriuretic factor – a circulating hormone stimulated by volume loading. Nature. 1985;314:264–266. doi: 10.1038/314264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubagwa K, Stengl M, Flameng W. Extracellular divalent cations block a cation non-selective conductance unrelated to calcium channels in rat cardiac muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;502:235–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.235bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Sehrer J, van Smet P, van Driessche W, Droogmans G. Volume regulation in a toad epithelial cell line: role of coactivation of K+ and Cl− channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;487:367–378. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Sehrer J, Viana F, van Greef C, Raeymaekers L, Eggermont J, Droogmans G. Volume-activated Cl− currents in different mammalian non-excitable cell types. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;428:364–371. doi: 10.1007/BF00724520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein A, Mack E. Volume-activated calcium uptake: its role in cell volume regulation of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:C339–447. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.2.C339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruknudin A, Sachs F, Bustamante JO. Stretch-activated ion channels in tissue-cultured chick heart. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264:H960–972. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.3.H960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskoaho H. Atrial natriuretic peptide: synthesis, release, and metabolism. Pharmacological Reviews. 1992;44:479–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs F, Morris CE. Mechanosensitive ion channels in nonspecialized cells. Reviews of Physiology Biochemistry and Pharmacology. 1998;132:1–77. doi: 10.1007/BFb0004985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackin H. Mechanosensitive channels. Annual Review of Physiology. 1995;57:333–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoshima J, Izumo S. Mechanical stretch rapidly activates multiple signal transduction pathways in cardiac myocytes: potential involvement of an autocrine/paracrine mechanism. EMBO Journal. 1993;12:1681–1692. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoshima J, Izumo S. The cellular and molecular response of cardiac myocytes to mechanical stress. Annual Review of Physiology. 1997;59:551–571. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoshima J, Takahashi T, Jahan L, Izumo S. Roles of mechanosensitive ion channels, cytoskeleton and contractile activity in stretch-induced immediate-early gene expression and hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:9905–9909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki N, Mitsuiye T, Noma A. Effects of mechanical stretch on membrane currents of single ventricular myocytes of guinea-pig heart. Japanese The Journal of Physiology. 1992;42:957–970. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.42.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setoguchi M, Ohya Y, Abe I, Fujishima M. Stretch-activated whole-cell currents in smooth muscle cells from mesenteric resistance artery of guinea-pig. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;501:343–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.343bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdson WJ, Morris CE, Brezden BL, Gardner DR. Stretch activation of a K+ channel in molluscan heart cells. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1987;127:191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sorota S. Swelling-induced chloride-sensitive current in canine atrial cells revealed by whole cell patch-clamp method. Circulation Research. 1991;70:679–687. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy GP, Jr, Jobe R L, Taylor LK, Hansen DE. Stretch-induced depolarizations as a trigger of arrhythmias in isolated canine left ventricles. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263:H613–621. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.2.H613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng GN. Cell swelling increases membrane conductance of canine cardiac cells: evidence for a volume-sensitive Cl channel. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:C1056–1068. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.4.C1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubl J, Murer H, Kolb HA. Hypotonic shock evokes opening of Ca2+-activated K channels in opossum kidney cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1988;412:551–553. doi: 10.1007/BF00582547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenburgh HH. Mechanical forces and their second messengers in stimulating cell growth in vitro. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:R350–355. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.3.R350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandorpe DH, Small DL, Dabrowski AR, Morris CE. FMRFamide and membrane stretch as activators of the Aplysia S-channel. Biophysical Journal. 1994;66:46–58. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80749-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner DR, Russo M. Whole cell mechanosensitive K+ currents in rat atrial myocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1992;61:A251. [Google Scholar]

- Wellner MC, Isenberg G. Properties of stretch-activated channels in myocytes from the guinea-pig urinary bladder. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;466:213–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellner MC, Isenberg G. Stretch effects on whole-cell currents of guinea-pig urinary bladder myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1994;480:439–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XC, Sachs F. Block of stretch-activated ion channels in Xenopus oocytes by gadolinium and calcium ions. Science. 1989;243:1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.2466333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Rasmusson RL, Hall SK, Lieberman M. A chloride current associated with swelling of cultured chick heart cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;472:801–820. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]