Abstract

Whole-cell patch recording and puff pipette techniques were used to identify glutamate receptor mechanisms on bipolar cell (BC) dendrites in the zebrafish retinal slice. Recorded neurons were stained with Lucifer Yellow, to correlate glutamate responses with BC morphology.

BC axon terminals (ATs) consisted of swellings or varicosities along the axon, as well as at its end. AT stratification patterns identified three regions in the inner plexiform layer (IPL): a thick sublamina a, with three bands of ATs, a narrow terminal-free zone in the mid-IPL, and a thin sublamina b, with two bands of ATs. BCs occurred with ATs restricted to sublamina a(Group a), sublamina b(Group b) or with ATs in both sublaminae (Group a/b).

OFF-BCs belonged to Group aor Group a/b. These cells responded to glutamate or kainate with a CNQX-sensitive conductance increase. Reversal potential (Erev) ranged from −0.6 to +18 mV. Bipolar cells stimulated sequentially with both kainate and glutamate revealed a population of glutamate-insensitive, kainate-sensitive cells in addition to cells sensitive to both agonists.

ON-BCs responded to glutamate via one of three mechanisms: (a) a conductance decrease with Erev≈ 0 mV, mimicked by L-(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (APB) or trans-1-amino-1,3-cyclopentanedicarboxylic acid (trans-ACPD), (b) a glutamate-gated chloride conductance increase (IGlu-like) characterized by Erev≥ECl (where ECl is the chloride equilibrium potential) and partial blockade by extracellular Li+/Na+ substitution or (c) the activation of both APB and chloride mechanisms simultaneously to produce a response with outward currents at all holding potentials. APB-like responses were found only among BCs in Group b, with a single AT ramifying deep within sublamina b; whereas, cells expressing IGlu-like currents had one or more ATs, and occurred within Groups b or a/b.

Multistratified cells (Group a/b) were common and occurred with either ON- or OFF-BC physiology. OFF-BCs typically had one or more ATs in sublamina a and only one AT in sublamina b. In contrast, multistratified ON-BCs had one or more ATs in sublamina b and a single AT ramifying deep in sublamina a. Multistratified ON-BCs expressed the IGlu-like mechanism only.

Visual processing in the zebrafish retina involves at least 13 BC types. Some of these BCs have ATs in both the ON- and OFF-sublaminae, suggesting a significant role for ON- and OFF-inputs throughout the IPL.

Retinal bipolar cells are physiologically separated into ON- and OFF-subtypes based on responses to light and/or glutamate, the photoreceptor neurotransmitter. OFF-bipolar cells are depolarized by glutamate release in the dark. ON-bipolar cells, in contrast, are hyperpolarized by the very same glutamate release. The division of the light signal into ON- and OFF-pathways is achieved through a variety of glutamate receptors mediating these responses. OFF-bipolar cells express ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) that are directly activated by glutamate or the glutamate agonists, kainate and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA). Glutamate responses restricted to the kainate receptor family were recently described in OFF-bipolar cells of ground squirrel (DeVries & Schwartz, 1999). Kainate receptor currents are typically characterized by slower desensitization and recovery than AMPA receptor currents. Glutamate responses of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) family are not seen in retinal bipolar cells. Glutamate binding onto OFF-bipolar dendrites opens non-selective cation channels, increasing membrane conductance, and depolarizing the cell (Murakami et al. 1975; Sasaki & Kaneko, 1996).

ON-bipolar cells express a metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) that indirectly gates ion channels via a second messenger cascade (Nawy & Jahr, 1990; Nawy, 1999). This receptor is selectively agonized by L-(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (L-AP4 or APB) (Slaughter & Miller, 1981). In addition, APB has been reported to directly activate a potassium conductance (Hirano & MacLeish, 1991). Recently, a third ON-type glutamate-gated conductance, in which glutamate gates a chloride channel with transporter-like pharmacology (Grant & Dowling, 1995) was identified in ON-bipolar cells of white perch.

Classically, ON- and OFF-bipolar cells also differ by axon terminal ramification in the inner plexiform layer (IPL). OFF-bipolar cell axon terminals ramify in the distal IPL (sublamina a); whereas ON-bipolar cell axon terminals ramify in the proximal IPL (sublamina b) (Famiglietti et al. 1977; Stell et al. 1977). Multistratified bipolar cells have been identified in fish (Scholes, 1975; Sherry & Yazulla, 1993), turtle (Kolb, 1982), and salamander (Maple & Wu, 1997). Early anatomical studies of bipolar cell dendritic contacts identified basal contacts at synapses between photoreceptors and OFF-bipolar cells; while ON-bipolar cell dendrites terminated in invaginating ribbon synapses (Stell et al. 1977). Thus, the identification of basal contacts between photoreceptors and multistratified bipolar cells in monkey (Mariani, 1983) suggested that these cells represented a further population of OFF-bipolar cells. In accord with this, recent work in the salamander retina (Maple & Wu, 1997) physiologically identified bipolar cells with axon terminals ramifying in both sublaminae as OFF-cells.

In this report, we describe glutamate-gated currents and glutamate receptor types present on zebrafish bipolar cell dendrites and correlate the observed responses with axon terminal morphology. Zebrafish is an important model in developmental/molecular studies. It is the goal of the present work to define further the organization of the visual system in the zebrafish model. Based on the observed patterns of axonal ramification we have identified 13 morphological types of bipolar cells. In addition to classical ON or OFF stratification patterns, a diverse multistratified group containing both ON- and OFF-type responses was discovered. Glutamatergic mechanisms in ON-bipolar cells exhibited one of three different conductance patterns. OFF-bipolar cells exhibited a single ionotropic conductance pattern, but activated either by kainate-selective, or glutamate/kainate-selective receptors.

METHODS

Glutamate-evoked or glutamate agonist-evoked currents were recorded from 157 zebrafish bipolar cells (BCs) using whole-cell patch clamp techniques in the retinal slice preparation. Bipolar cells were initially identified by somal position in the distal to mid inner nuclear layer (INL). Lucifer Yellow (1 % solution) was present in the patch pipette to intracellularly label recorded neurons and reveal bipolar cell morphology.

Preparation of retinal slices

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) were obtained from a local supplier (Petsmart, Inc., Bowie, MD, USA), maintained on a 14 h light:10 h dark photoperiod, and fed daily. Zebrafish were dark-adapted overnight prior to killing. Following decapitation and ocular enucleation, retinal slices (Werblin, 1978) were prepared as described previously (Connaughton & Maguire, 1998). Retinal slices were viewed using a Zeiss compound microscope equipped with a ×40 water immersion lens and Hoffman modulation contrast optics. Lucifer Yellow-filled cells were visualized using a mercury light source and an FITC filter set.

The morphology of Lucifer Yellow-filled bipolar cells was determined after recording glutamate-gated currents. At this time, the dendritic arbor was identified and the location of axon terminals within the IPL determined. Glutamate responses were then correlated with the axon terminal ramification patterns. In intact cells, axonal processes terminated at a synaptic bouton. We found no evidence that bipolar cells with a single bouton lost a second or third terminal during tissue preparation (i.e. a multistratified cell incorrectly counted as a monostratified cell). Some bipolar cells exhibiting glutamate-gated currents did not have an identifiable axon terminal, probably due to tangentially cut retinal sections.

Non-responding bipolar cells expressed voltage-gated currents (recorded immediately after placing the cell in the whole-cell configuration), but no glutamate-gated responses. Most neurons not responding to glutamate lacked identifiable dendritic processes, though 7 % of bipolar cells examined were completely intact, but glutamate insensitive. In some slices, more than one bipolar cell was stained with Lucifer Yellow, indicating dye coupling between cells. Coupled cells were not scored in our analysis.

Solutions

Ligand-gated currents were recorded using a caesium-based intracellular solution containing (mM): 12 CsCl and 104 caesium gluconate (or 116 CsCl for high [Cl]i solution), 1 EGTA, 4 Hepes, 0.1 CaCl2, 2 Na-ATP, 1 Na-GTP, and 1 cGMP. The standard extracellular solution contained (mM): 120 NaCl (sodium isethionate in low [Cl−]o solution), 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 3 CaCl2, 4 Hepes, 3 D-glucose, and 2–5 CoCl2. In separate experiments, glutamate (1 mM) or the glutamate agonists, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA, 100 μm), kainate (50 μm), APB (250 μm), or trans-1-amino-1,3-cyclopentanedicarboxylic acid (trans-ACPD, 210 μm), were focally applied at 30–60 s intervals to bipolar cell dendrites using a second application pipette (50 ms puff, 15 psi). APB was purchased from Calbiochem International (La Jolla, CA, USA); NMDA and trans-ACPD were purchased from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA, USA). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA).

Data acquisition and analysis

Glutamate-gated currents were elicited at stepwise increasing holding potentials (Vh) from −60 to +20 mV (20 mV increments). Raw current traces were boxcar filtered in pCLAMP (2 ms interval, 9 data points on each side) prior to data analysis. To reduce periodic noise, some traces were further filtered (13–17 point run average on either side). Peak current amplitude at each holding potential was measured and plotted as a current-voltage relationship (Microcal Origin version 4.0). The reversal potential (Erev) for each current was determined by a linear regression through the I–V plot (only fits with r2 > 0.7 included). To document voltage-gated currents, depolarization-elicited currents were measured (Vh, −60 mV; voltage steps ranged from −40 to +30 mV, in 10 mV increments, 100 ms step duration), prior to glutamate application.

Data were collected using an Axopatch-1C patch clamp amplifier and pCLAMP (version 6.0) software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). Drugs were focally applied onto bipolar cell dendrites using a Model PPS-2 pneumatic pressure system (Medical Systems Corp., Greenvale, NY, USA). Thin-walled, filamented borosilicate pipettes were pulled to the desired tip diameter (5–10 MΩ) with a Flaming-Brown P-87 micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA, USA). Seal resistance was 1–10 GΩ. Series resistance averaged 36 ± 3.6 MΩ (±s.e.m.; n = 38). Liquid junction potentials (Neher, 1992) measured −6 mV for standard extracellular solution and −9 mV for low Cl− medium. Values in the text are uncorrected. This work has appeared previously in preliminary form (Connaughton, 1997; Connaughton & Nelson, 1998).

RESULTS

Bipolar cell classification scheme

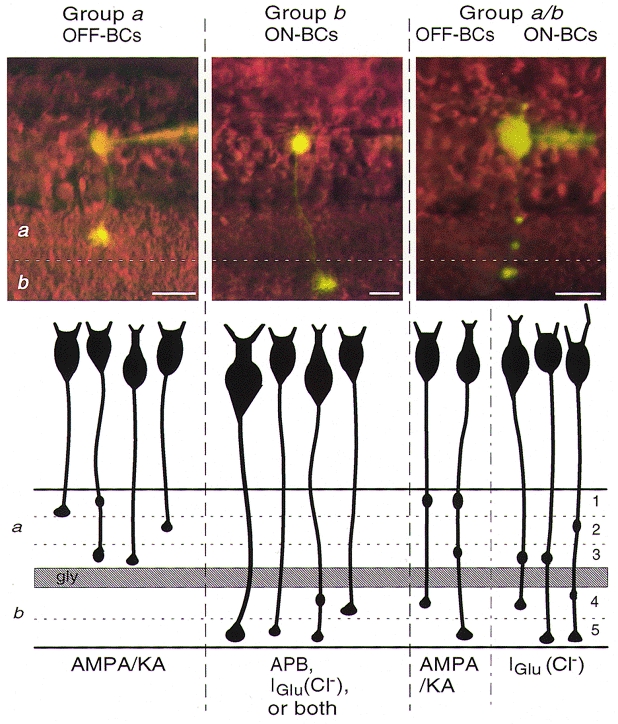

Based on bipolar cell axon terminal (AT) ramification patterns, we divided zebrafish BCs identified in this study into three general groups: a, b and a/b. Cells in Group a have ATs ramifying only in sublamina a; whereas, cells in Group b have ATs ramifying in sublamina b. Group a/b represents multistratified BCs with identifiable axonal boutons in both sublaminae. Each group contains a number of types, characterized by the particular layers in which the boutons reside (see Fig. 5). We have divided the zebrafish IPL into five strata with the distal three strata forming sublamina a and the proximal two strata forming sublamina b. This IPL stratification scheme is supported by immunocytochemical data showing that glutamate-containing BC ATs ramify within a thick OFF-sublamina and a thin ON-sublamina, separated by a bouton-free zone staining positively with anti-glycine (Connaughton et al. 1999).

Figure 5. Correlation of zebrafish bipolar cell morphological Groups a, b and a/b with glutamate receptor physiology.

The different groups and the corresponding polarity (ON- or OFF-) are indicated at the top of each column. In the top panels, light micrographs show representative bipolar cells within each group filled intracellularly with Lucifer Yellow. The schematic drawings below the micrographs depict further morphological variants within each group: Group a– 4 types, Group b– 4 types, and Group a/b– 5 types. The identified glutamate receptor type(s) contributing to the responses are listed at the bottom of each column. Bipolar cells within Group a express AMPA/kainate OFF-centre responses. Group b cells expressed one of three possible ON-centre mechanisms: a glutamate-gated chloride conductance (IGlu-like), a metabotropic APB-type response, or a combination of both responses. APB responses were found only among Group b cells. Multistratified a/b cells were categorized as either OFF-centre AMPA/kainate types or cells expressing ON-centre IGlu-like chloride responses. All bars = 10 μm. The dashed line through the micrographs denotes the sublamina a/b border, a glycine-positive terminal-free band in the IPL.

Glutamate elicited four different current responses in zebrafish BCs. Reversal potentials (Erev) were broadly distributed and reflected conductance increases, conductance decreases, and differential sensitivities to 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), an iGluR antagonist. Each physiological response was correlated with BC morphology to identify bipolar cell types comprising the ON- and OFF-pathways within the retina. Each bipolar cell examined was stimulated with one agonist only, except as indicated. Table 1 summarizes the morphological and physiological properties of all cells contributing to this study. For inclusion in our summary physiological data (Table 1), at least partial staining of dendritic and axonal processes was required. Glutamate-gated currents could be elicited in bipolar cells lacking an axon terminal, but not from cells lacking a dendritic process (see Methods above). Cells that were not stained at all by Lucifer Yellow were not included. Cells potentially connected by gap junctions, as evidenced by two or more Lucifer Yellow-stained somata, were also excluded. However, to construct the morphological summary (Fig. 5, Table 1) complete staining of bipolar cell axon terminals was required. Correspondingly there are fewer cells in the morphological summaries. Within Table 1, the number of cells in each of the three morphological groups responding to a particular agonist is presented in bold. The number of cells that did not respond to an agonist treatment is in italics. Based on these selection criteria, we found that over 90 % of bipolar cells tested responded to glutamate, with a variety of mechanisms, whereas about 60 % responded to kainate, about 30 % responded to APB or trans-ACPD, and none responded to NMDA. These physiological responses and their morphological correlates are discussed in greater detail below.

Table 1.

Summary table correlating bipolar cell glutamate responses with axon terminal ramification patterns

| AT ramification | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonist | Dose | No. cells tested | Response | No. cells responding (% total) | Erev (mV) | Conductance (pS) | a | b | a/b | Polarity |

| l-Glu | 1 mm | 100 | g increase (Kainate-like) | 15 (15%) | 6 ± 6.4 | 0.2 ± 0.18 | 8 | 2 | 2 | OFF |

| g decrease (APB-like) | 4 (4%) | −0.9 ± 2.9 | −0.2 ± 0.16 | 1 | 2 | — | ON | |||

| g increase Cl− (IGlu-like) | 60 (60%) | −40 ± 8.6 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 2 | 11 | 6 | ON | |||

| Outward I (APB + IGlu-like) | 14 (14%) | — | — | — | 2 | — | ON | |||

| None | 7 (7%) | — | — | 2 | 1 | — | — | |||

| Kainate | 50 μm | 14 | g increase | 8 | 11 ± 7.1 | 1 ± 0.64 | 4 | — | 1 | OFF |

| (57.1%) | — | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| APB | 250 μm | 21 | g decrease | 6 | −3 ± 8.4 | −0.1 ± 0.46 | — | 2 | — | ON |

| (28.6%) | 3 | 3 | 1 | |||||||

| trans-ACPD | 210 μm | 15 | g decrease | 5 | 1 ± 9.5 | −0.2 ± 0.04 | — | 2 | — | ON |

| (33.3%) | 2 | 5 | 1 | |||||||

| NMDA | 100 μm | 7 | None | 0 | — | — | 1 | 3 | — | — |

| (0%) | ||||||||||

For each agonist tested, the administered concentration (dose), total number of cells tested, response type, number of cells responding (and percentage of total), reversal potential (Erev) and conductance (g) of ligand-gated currents, axon terminal ramification patterns, and bipolar cell polarity are presented. Intact cells that elicited voltage-gated currents, but did not respond to agonist application were classified as non-responding cells. Axonal bouton location within sublamina a, sublamina b, or both sublamina a and b of the inner plexiform layer was categorized for all intact cells (both responding and non-responding). The axon terminal ramification patterns for bipolar cells tested with each agonist are presented with the number of responding cells given in bold and that of non-responding cells in italics. Values are means ± s.d.

For each agonist tested, the administered concentration (dose), total number of cells tested, response type, number of cells responding (and percentage of total), reversal potential (Erev) and conductance (g) of ligand-gated currents, axon terminal ramification patterns, and bipolar cell polarity are presented. Intact cells that elicited voltage-gated currents, but did not respond to agonist application were classified as non-responding cells. Axonal bouton location within sublamina a, sublamina b, or both sublamina a and b of the inner plexiform layer was categorized for all intact cells (both responding and non-responding). The axon terminal ramification patterns for bipolar cells tested with each agonist are presented with the number of responding cells given in bold and that of non-responding cells in italics. Values are means ±s.d.

Glutamate-elicited conductance increases, with Erev≥ 0 mV

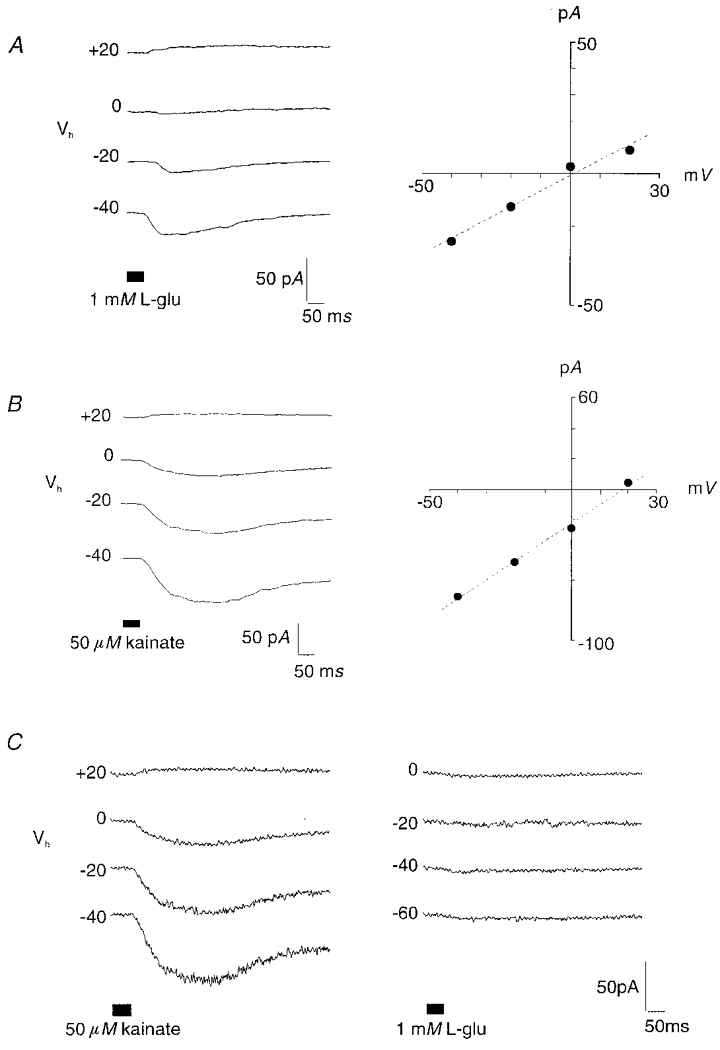

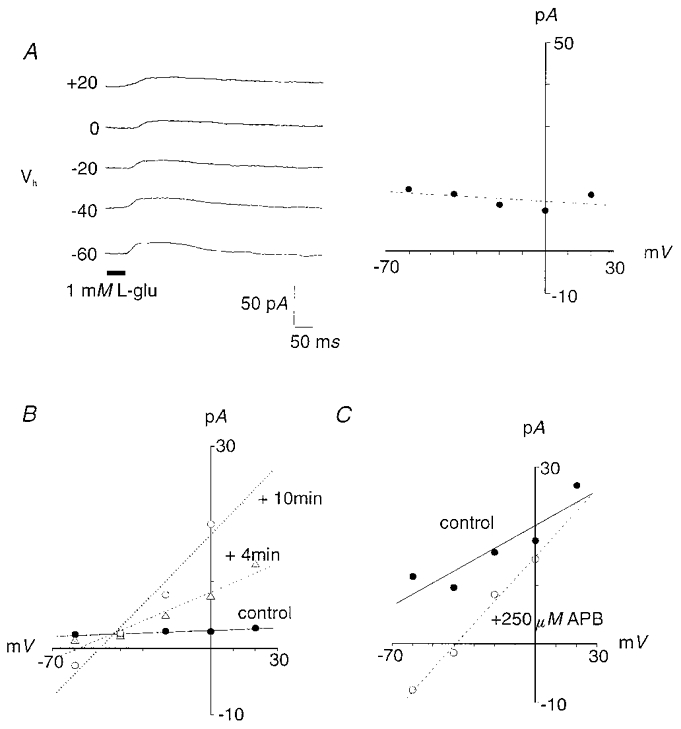

Glutamate-evoked, CNQX-sensitive AMPA/kainate-like responses were observed in 15 % of cells (15 of 100 cells). Peak current amplitudes, typically measuring 20–30 pA, were accompanied by a conductance increase. Currents were blocked by 150–300 μm CNQX (n = 4 of 5 cells). Glutamate application onto these presumed OFF-bipolar cells elicited currents with a range of recorded Erev. In 14 of 15 cells exhibiting this response (Fig. 1A), the Erev ranged from −0.6 to +18 mV, with a mean value of 6 ± 6.4 mV (Table 1). The calculated mean conductance for this current was 0.2 ± 0.18 pS. One outlier reversed at −17 mV. Such net excitatory glutamate-elicited currents were recorded from cells within Group a (n = 8), Group a/b (n = 2) and Group b (n = 2).

Figure 1. Putative zebrafish OFF-bipolar cells responded to glutamate application with a conductance increase and a positive Erev.

A, in 14 of 15 cells with this response, glutamate application elicited a current with a Erev ranging from −0.6 to +18 mV, as shown in this representative whole-cell current trace (left) and current-voltage relationship (right). B, similar currents were evoked with the application of 50 μm kainate (8 of 14 cells). Traces in A and B were recorded from different cells. C, when both glutamate and kainate were administered to the same bipolar cell, some (n = 5) responded to kainate, but not glutamate. In this and subsequent figures, holding potentials (Vh) are indicated to the left of each trace, drug application is indicated by the bar below the traces, and current-voltage relationships represent peak current amplitudes measured at each holding potential.

Kainate application also elicited currents characterized by a conductance increase (0.97 ± 0.65 pS) and an Erev ranging from 0.2 to +18 mV, though the average Erev for kainate-gated currents (11 ± 7.1 mV; n = 5) was more depolarized than glutamate-elicited responses (Fig. 1B, Table 1). In addition, there were several outliers (n = 3) which reversed at more depolarized levels than the range of voltage steps. Peak current amplitudes for kainate-gated currents were greater than for glutamate-gated currents, ranging from 50 to 100 pA. Kainate-evoked currents were also sensitive to CNQX (n = 3). Overall, kainate responses were identified in 8 of 14 cells (57 %) tested with this agonist. Kainate currents were recorded from intact cells classified within either Group a (n = 4) or Group a/b (n = 1); non-responding cells were grouped within Group a/b (n = 1) or Group b (n = 3).

The above paragraphs discuss the glutamate- and kainate-elicited currents individually. However, the majority (12 of 14) of bipolar cells stimulated with kainate were also stimulated with glutamate. Using a dual puffer system, we administered glutamate and kainate to the same cell using two application pipettes, one containing glutamate and the other containing kainate. Initially, one agonist was applied onto bipolar cell dendrites and the response recorded. After 2–3 min, the other agonist was applied. The results indicate that only one cell responded to both glutamate (Erev, +17 mV) and kainate (Erev, +40 mV). The majority of neurons tested using this protocol responded to kainate, but not glutamate (n = 5; Fig. 1C) or responded to neither compound (n = 5). These results were obtained regardless of the order of agonist application. Two cells responded to glutamate, but not kainate, with a chloride conductance subsequently identified in ON-cells (see below). The different Erev values for the cell responding to both kainate and glutamate and the observed kainate sensitivity, glutamate insensitivity in other cells suggests there may be at least two populations of OFF-bipolar cells in zebrafish: one with ionotropic receptors selectively sensitive to kainate, and another with receptors responding to both glutamate and kainate. This interpretation is further supported by the more depolarized range of Erev values observed for all recorded kainate-gated currents (see above). Kainate- or kainate/glutamate-selective mechanisms may occur separately or in combination.

Glutamate-elicited conductance decreases, with Erev≡ 0 mV

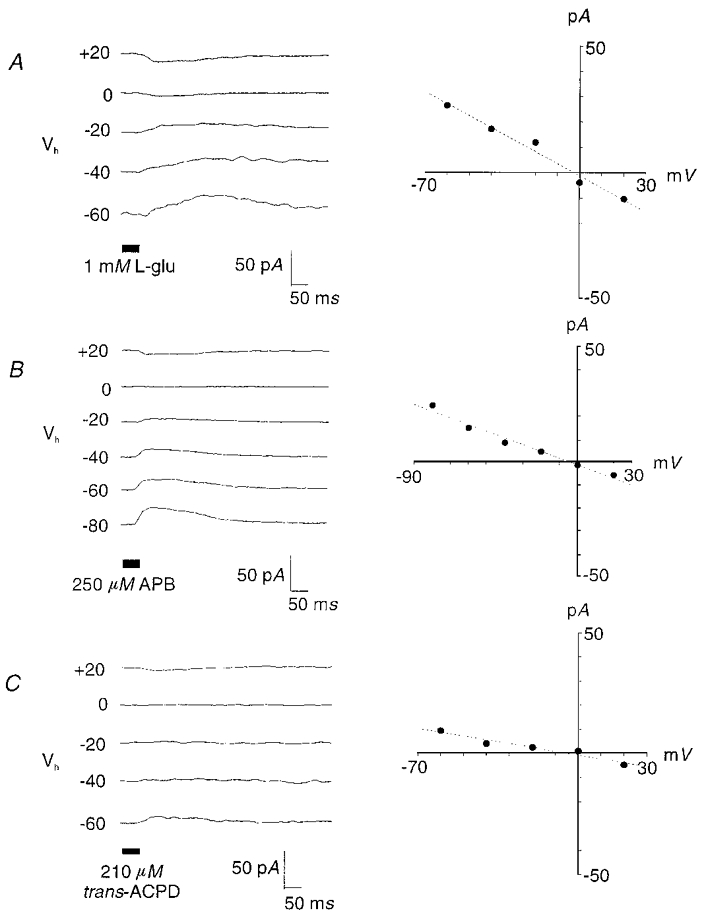

Glutamate elicited a conductance decrease (mean, −0.2 ± 0.16 pS) in 4 % of cells tested, with a calculated mean Erev of −0.9 ± 2.9 mV (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). Peak current amplitude measured 20 pA. A similar response was recorded in another group of cells after the application of APB, an mGluR agonist, onto bipolar cell dendrites. APB elicited a current characterized by a mean Erev of −3 ± 8.4 mV and a mean conductance change of −0.1 ± 0.46 pS (Table 1, Fig. 2B). We did not observe any conductance increases in response to APB application. Examination of repeated I–V plots for APB-elicited currents suggested rundown of some currents, despite the addition of nucleotides within the patch pipette. In two of four cells for which multiple current plots were generated, rundown was observed 4–5 min after placing the cell in the whole-cell configuration. However, we did not observe a complete rundown as APB application elicited currents throughout the course of an experiment. Intact bipolar cells responding to APB (n = 2) had identifiable axon terminals in sublamina b only; while non-responding cells displayed diverse morphologies with terminals exclusively in sublamina a (n = 3), sublamina b (n = 3), or both sublamina a and b (n = 1).

Figure 2. Glutamate application elicited APB-like responses in a subset of presumed ON-bipolar cells.

A, these cells responded to glutamate with a conductance decrease and an Erev near 0 mV. A similar response was elicited by the application of APB (250 μm) (B) or trans-ACPD (210 μm) (C).

Another mGluR agonist, trans-ACPD, also elicited responses in zebrafish bipolar cells (Fig. 2C). Trans-ACPD-gated currents were observed in five of 15 cells tested with this agonist. In three of these cells, the Erev averaged 1 ± 9.5 mV, with a mean conductance change of −0.2 ± 0.04 pS. However, in two cells, an Erev was not observed over the voltage range tested (−60 to +20 mV). For these cells the calculated conductance was −0.1 ± 0.04 pS, similar to the other responding cells; however, the calculated Erev of 67 ± 37.9 mV. As observed in bipolar cells responding to APB application, trans-ACPD responses were evoked in cells with axon terminals ramifying in sublamina b only (n = 2); while non-responding cells had axon terminals within sublamina a (n = 2), sublamina b (n = 5), or were bistratified (n = 1).

Thus, zebrafish BCs responding to the glutamate agonists APB and trans-ACPD were classified within morphological Group b, corresponding to the classical morphology of ON-BCs; however, not all cells with Group b morphology responded to metabotropic agonists.

Glutamate-gated chloride conductance

In 60% (60 of 100) of bipolar cells examined, glutamate elicited currents with an observed Erev between −20 and −60 mV. (For example, Erev is −55 mV in the cell in Fig. 3A.) Glutamate application elicited a conductance increase in these cells with a calculated mean Erev of −40 ± 8.6 mV and conductance increase of 0.5 ± 0.3 pS (Table 1). Peak current amplitude averaged 30–50 pA. Bipolar cells expressing this current had identifiable axon terminals within sublamina a (n = 2), sublamina b (n = 11), or in both sublaminae (n = 6). Thus, most of the neurons expressing this current are morphological ON-bipolar cells, though the overall morphology was less adherent to classical patterns than BCs expressing the metabotropic (APB-type) receptor (Table 1).

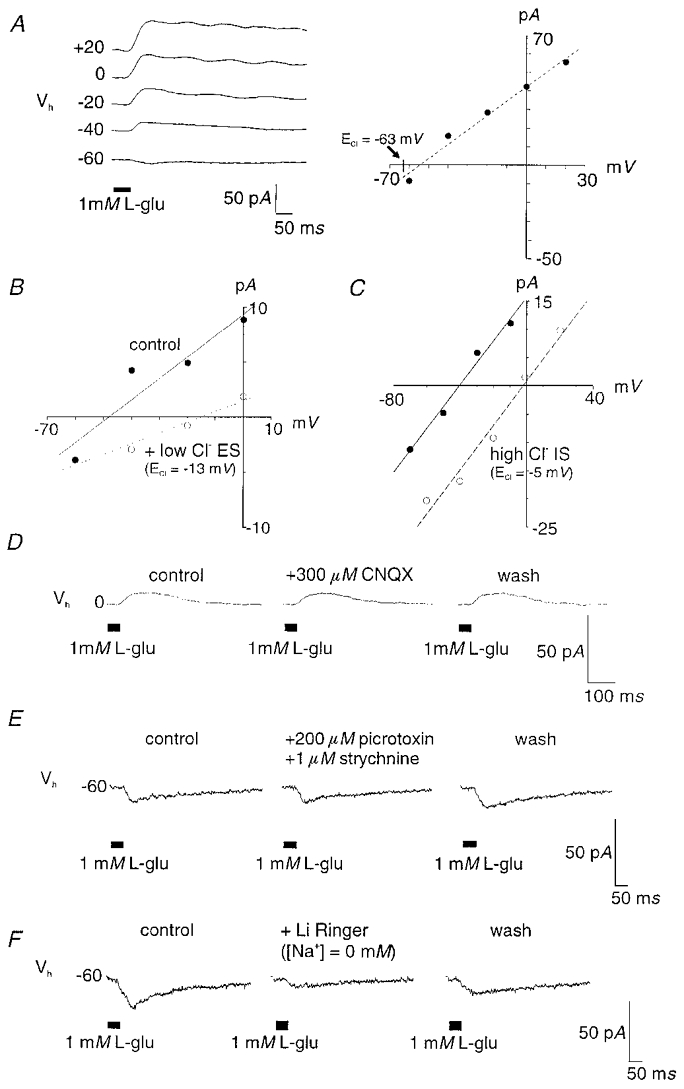

Figure 3. The majority of zebrafish bipolar cells examined (60 of 100) responded to glutamate with a conductance increase and an Erev near ECl.

A, representative current trace (left) and current-voltage relationship (right) for the glutamate-gated chloride conductance (IGlu-like current). ECl, −63 mV. The observed Erev depolarized in a low Cl− extracellular solution (ES, [Cl−]o, 20 mM; new ECl, −13 mV; n = 10) (B) or, a high Cl− intracellular solution (IS, [Cl−]i, 116 mM; new ECl, −5 mV; n = 3) (C) suggesting this current is carried by chloride ions. This current was insensitive to 300 μm CNQX (n = 8) (D) and 200 μm picrotoxin plus 1 μm strychnine (n = 5) (E). F, substitution of external Na+ with Li+ partially blocked this current (n = 4). These cells are likely to be ON-bipolar cells physiologically.

The range of reversal potentials for this glutamate-gated mechanism was typically at more depolarized levels than the calculated reversal potential for chloride (−63 mV). Poor diffusion into fine cellular processes by the chloride substitute gluconate may account for this, as seen also with some intracellular dyes (Stretton & Kravitz, 1968). To determine if these currents represent a chloride conductance, we performed the following experiments. Substitution of the standard extracellular solution ([Cl−]o, 140 mM) with a low Cl− medium ([Cl−]o, 20 mM) resulted in a depolarizing shift (10 mV to 30 mV) in the Erev in 10 of 13 cells (Fig. 3B). The recorded Erev in the low [Cl−]o solution was between 0 and −20 mV, which was close to the calculated chloride equilibrium potential (ECl, −13 mV) under these conditions. Similarly, substitution of the standard intracellular Cl− solution ([Cl−]i, 12 mM) with a high Cl− solution ([Cl−]i, 116 mM) resulted in glutamate-elicited currents with an Erev of −3 ± 1.2 mV (n = 3 of 3 cells; Fig. 3C), which is close to the expected ECl value (−5 mV). These last experiments were carried out in media containing 75 μm CNQX and 250 μm APB to suppress other glutamate-gated currents. Thus, the change in Erev for this glutamate-gated current paralleled the change in either intracellular or extracellular chloride concentrations indicating that this current is carried by chloride ions.

Two types of glutamate-gated chloride currents have been identified in retinal bipolar cells. In rat, the glutamate-elicited chloride current is generated indirectly via GABAergic inputs from presynaptic amacrine cells (Hartveit, 1996). Kainate application stimulated amacrine cells to release GABA onto bipolar cell terminals (Hartveit, 1996). In contrast, glutamate directly activates a chloride current with transporter-like pharmacology in white perch bipolar cells (Grant & Dowling, 1995). To determine if the glutamate-elicited chloride current we recorded in zebrafish bipolar cells was generated directly by glutamate or indirectly from endogenous GABA and/or glycinergic inputs, we performed the following experiments.

First, we observed that the current in zebrafish was insensitive to the bath application of 300 μm CNQX (8 of 9 cells; Fig. 3D), indicating the chloride current is not generated by the activation of AMPA/kainate-type receptors. Second, the glutamate-gated chloride current was insensitive to the co-application of 50–200 μm picrotoxin, the GABAA,C receptor antagonist, plus 1 μm strychnine, a glycine receptor blocker (n = 5 of 5 cells; Fig. 3E). These findings suggest that the chloride current in zebrafish bipolar cells is directly gated by glutamate and not generated via indirect GABAergic or glycinergic inputs from other retinal neurons.

Next, we wished to determine if the chloride current in zebrafish was similar to IGlu, the glutamate-gated chloride current with transporter-like pharmacology previously identified in white perch (Grant & Dowling, 1995). IGlu is elicited directly by glutamate, sensitive to changes in internal [Cl−], and completely blocked in Na+-free (lithium-based) Ringer solution (Grant & Dowling, 1995). To examine the dependence of this current on external Na+, we performed experiments in which glutamate-gated currents were recorded using the standard pipette solution and an extracellular solution containing 5 mM CoCl2, 75 μm CNQX, and 250 μm APB to isolate the chloride current. Under these conditions, glutamate application elicited a current with a conductance increase and mean Erev of −43 ± 4.8 mV (n = 3). This current was reduced 31–75 % when the control external solution was replaced with a solution containing LiCl ([Na]o, 0 mM; n = 4 of 4 cells; Fig. 3F).

Taken together, these experiments indicate that the glutamate-elicited chloride current in zebrafish bipolar cells is IGlu-like as it is gated directly by glutamate and sensitive to changes in either [Cl−]i or [Cl−]o, but only displays partial sensitivity to sodium-free medium.

ON-bipolar cells that express two conductance mechanisms

Glutamate application elicited outward currents at all Vh values tested in 14 cells (Fig. 4A). No Erev was observed across the test voltage range (−60 to +20 mV). Similar currents, reported in white perch (Grant & Dowling, 1996), result from the combined action of IGlu and APB mechanisms in bipolar neurons. In zebrafish, glutamate-elicited ‘all outward’ currents also appear to be generated via multiple conductance mechanisms within the same bipolar cell. Further, these conductances, which were initially expressed equally, could change over time.

Figure 4. In one group of bipolar cells, glutamate elicited outward going currents at all holding potentials measured.

These cells express two conductance mechanisms in response to glutamate application, both consistent with ON-bipolar cell physiology. A, representative current trace (left) and current-voltage relationship (right) for this response. B, in a subset of cells (2 of 8), current responses changed with time, revealing a current with an Erev near ECl and a conductance increase. C, the application of 250 μm APB also changed such current responses resulting in a current with an Erev of −40 mV.

In eight cells, current activity was followed over time. In most of these cells (n = 6), a change in slope conductance of glutamate-evoked currents was observed 2–14 min after initial recordings. In two of these cells, the change was so extensive as to result in current responses with an Erev between −40 and −60 mV (Fig. 4B) and a conductance increase. We believe this emergent current to be the IGlu-type chloride current previously identified in other populations of zebrafish ON-bipolar cells (see above). In the remaining four cells, a change in slope conductance was observed, including in some cases a change in sign of slope conductance, but currents remained all outward, with no Erev.

Bath application of 250 μm APB increased slope conductance in two cells. In one of these cells, the altered current response revealed an Erev between −30 and −40 mV (Fig. 4C) and a conductance increase. The sensitivity of these cells to APB and the negative reversal potential of the APB-insensitive current component suggests that zebrafish bipolar cells expressing ‘all outward’ currents may have two conductance mechanisms to glutamate (i.e. Saito et al. 1979; Nawy & Copenhagen, 1987): an APB-sensitive conductance decrease and an APB-insensitive, IGlu-like conductance (Grant & Dowling, 1996). Spontaneous changes in slope conductance appear to be due to changes in either IGlu or APB conductance mechanisms. In half of the cells, changes in slope conductance were due to an increase (‘run-up’) in the amplitude of the chloride current (as in Fig. 4B) as the observed increases in current amplitude occurred at 0 mV, the Erev for APB-gated currents. In the other half, changes in current amplitude were observed around ECl, but not at potentials near or positive to 0 mV, suggesting the APB component changed in these cells. Taken together, these findings suggest that a population of bipolar cells expresses multiple conductance mechanisms in response to glutamate release and that both mechanisms can change in a time-dependent manner, or in response to pharmacological blockade. Bipolar cells expressing this type of glutamate-gated current were consistently classified within Group b, similar to ON-BC types responsive to metabotropic agonists (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The zebrafish retinal slice preparation has provided access to a diversity of physiological and morphological BC types. Four major response patterns elicited by glutamate in zebrafish bipolar cells were characterized by changes in membrane conductance, Erev, and CNQX, APB, chloride, or lithium sensitivity. Numerically, the different glutamate responses in zebrafish bipolar cells can be separated as follows: 15 % of the cells were presumed OFF-bipolars expressing an AMPA/kainate-type response, 78 % of the cells were ON-bipolars expressing either APB responses (4 %), a glutamate-gated chloride current (60 %), or a combination of the chloride and APB mechanisms (14 %). The remaining bipolar cells tested (7 %) were intact, but did not respond to glutamate. In addition, the AMPA/kainate responses characteristic of OFF-bipolar cells could be further subdivided into two or more groups based on agonist sensitivity. Responses to N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) were not observed (n = 7; Table 1), even when NMDA was co-applied with 1 μm glycine.

A diversity of glutamate responses was observed in ON-BCs, indicating there are multiple mechanisms available to shape the light responses of these cells. APB-like mechanisms appeared restricted to cells in Group b (Fig. 5) similar to the classic ON-BC morphology (Famiglietti et al. 1977; Nelson & Kolb, 1983; Euler et al. 1996). Combining the morphological data collected from bipolar cells exhibiting conductance decreases in response to either glutamate, APB, or trans-ACPD, with cells expressing glutamate-evoked all outward currents, known to include an APB-like mechanism (Table 1), eight of nine cells with a metabotropic response had axon terminals restricted to sublamina b. In contrast only 34 of 71 stained cells overall had this morphology.

The other ON-type mechanism, similar to IGlu, appeared in a broader range of morphologies including numerous cells from Group a/b as well as Group b (Fig. 5). Seventeen of 19 cells responding in this manner were classified within these two groups. In contrast, only 48 of 71 stained cells overall belonged to these groups. We did not observe an APB-elicited potassium conductance increase as reported in salamander bipolar cells (Hirano & MacLeish, 1991). Our standard pipette solution contained caesium to suppress outward rectifying potassium currents (Connaughton & Maguire, 1998) which interfere with measurement of glutamate reversal potentials (Lasansky, 1992). Other investigators (Nawy & Copenhagen, 1990) have argued that caesium may block APB-elicited potassium currents.

Zebrafish presumed OFF-bipolar cells responded to glutamate application with an AMPA/kainate-like conductance increase and a broad range of positive Erev values, suggesting there might be more than one population of OFF-bipolar-cell mechanisms in this retina. While some OFF-bipolar cells responded to either glutamate or kainate with similar currents, our dual-puffer experiments indicated that other OFF-bipolar cells were selectively sensitive to kainate but not glutamate. OFF-bipolar cells occurred with Group a or Group a/b morphology (Fig. 5) with 15 of 17 cells belonging to one of these groups. In contrast only 37 of 71 stained cells overall had such morphologies. Like ON-bipolar cells, OFF-bipolar cells employ multiple glutamatergic mechanisms though, in the case of OFF-bipolar cells, all mechanisms appear to be ionotropic.

AMPA/kainate responses were found among cells within Group a/b. In general, Group a/b OFF-cells were characterized by a single axon terminal in sublamina b (layer 4 or 5) and one or more axonal boutons ramifying throughout sublamina a (layers 1, 2, and/or 3). In contrast, Group a/b ON-BCs exclusively expressed an IGlu-like current and typically had one or more axon terminals in sublamina b (layers 4 and 5) and a single axonal bouton ramifying deep sublamina a (layer 3). Multistratified cells expressing both mechanisms were not identified. Colour opponent BCs, as identified in carp (Kaneko & Tachibana, 1981), might logically have been generated by a combination of ON- and OFF-glutamatergic inputs, but no examples were found.

Metabotropic glutamate receptors are separated into three groups based on sequence homology (Nakanishi, 1992), though they also differ in agonist selectivity and second messenger pathways. Studies employing either in situ hybridization techniques (Nakajima et al. 1993) or mGluR6-deficient mice (Masu et al. 1995) have identified mGluR6 as the probable glutamate receptor located on ON-bipolar dendrites. APB is the agonist for this, and other, Group III mGluRs (Nakajima et al. 1993; Pin & Duvoisin, 1995); while trans-ACPD is an agonist at Group I and II mGluRs (Pin & Duvoisin, 1995). Both these compounds elicit responses in zebrafish bipolar cells. The similar kinetics and conductance changes of APB- and trans-ACPD-gated currents in zebrafish indicate these compounds may act through a similar intracellular pathway, whether or not the same receptors (i.e. Thoreson & Miller, 1994; Tian & Slaughter, 1994, 1995) are activated.

Mammalian rod bipolar cells express APB-elicited currents characterized by a conductance decrease and Erev≡ 0 mV (Yamashita & Wässle, 1991; de la Villa et al. 1995). Rod-generated ON responses of large bodied mixed BCs in fish also arise through a metabotropic pathway (Saito et al. 1979; Nawy & Copenhagen, 1987, 1990; Grant & Dowling, 1996), as do some cone-generated responses (Saito & Kujiraoka, 1982). In the zebrafish retina, signals processed by this pathway, whether they arise from rods or cones, are present in Group b BCs. Although metabotropic APB responses were readily detected in zebrafish BCs, none were seen in the Group a/b, and only one of nine cells in Group a. The majority of ON-BCs in the zebrafish retina expressed an IGlu-like current. Such responses were sensitive to sodium substitution, and to manipulation of external chloride, but insensitive to CNQX, picrotoxin or strychnine. This current in zebrafish differed from that in white perch (Grant & Dowling, 1995) by its only partial sensitivity to lithium-for-sodium substitution, which suggests a further mechanism might be involved in generating this current. Many IGlu-expressing cells were multistratified a/b types which are likely to be the classic small bodied cone-contacting bipolar cells (Stell, 1967), as recognized by patterns of axonal stratification (Scholes, 1975; Sherry & Yazulla, 1993). Based on present observations, ON-cone BCs within Group a/b utilize exclusively the chloride conductance mechanism. There are, of course, OFF-cone BCs of similar morphology which utilize CNQX-sensitive AMPA/kainate receptors. Together these multistratified cone BCs represent onset and offset light excitation systems that do not respect the classical ON-OFF layering of cyprinid inner plexiform layer (Famiglietti et al. 1977).

There is a further group of BCs, with axon terminal boutons restricted to sublamina b, expressing a chloride current similar to IGlu. Overall this current was expressed in 60 % of the presumed ON-bipolar cells examined. The high percentage of this type of ON-BC (vs. those expressing APB-type receptors) may reflect a sampling bias during our experiments. However, we believe that our results may represent a uniform sampling of zebrafish BCs as we were unable to selectively record from any one specific BC type (such as large Mb-type bipolars). Based on present observations, ON-cone BCs within Group a/b utilize exclusively the chloride conductance mechanism. The inclusion of such cells in our sample, together, potentially, with further ON-cone BC types, which might not commonly be recorded in other preparations, may help to explain the large fraction of cells observed with this receptor mechanism. IGlu-like responses are likely to arise in cone BCs, as rod signals are believed to be associated only with an APB-type mechanism (Saito et al. 1979; Grant & Dowling, 1996). Another set of zebrafish ON-BCs expressed mixed APB and chloride conductances. These are likely to be mixed rod-cone bipolar cell types (Stell, 1967; Ishida et al. 1980; Saito et al. 1985).

In a previous study, axon terminal ramification patterns were correlated with the voltage-gated currents in zebrafish bipolar cells (Connaughton & Maguire, 1998). These authors report no relationship between neuronal morphology (i.e. classification into Group a, b or a/b) and voltage-gated current expression, as all identified potassium and calcium currents were recorded from cells classified within each morphological group. Overall, the morphological identification of ON- and OFF-bipolar cells in this study supports the conclusion that ON- and OFF-cells in the zebrafish retina cannot be uniquely distinguished by their voltage-gated currents. However, an examination of the two data sets suggests trends in the results. For example, Group a bipolar cells express AMPA/kainate-type receptors and are more likely to express the transient A-type potassium current in response to membrane depolarizations. In contrast, cells within Group b, characterized by a single axon terminal ramifying deep (i.e. layer 5) within the IPL, express APB-type glutamate receptors and are more likely to express a delayed rectifying potassium current and an L-type calcium current in response to membrane depolarizations (Connaughton & Maguire, 1998). Multistratified cells, however, comprise both ON- and OFF-cell types and express a mixture of voltage-gated currents.

References

- Connaughton VP. Glutamate-gated currents in zebrafish, Danio rerio, retinal bipolar cells. Bulletin of the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory. 1997;36:43. [Google Scholar]

- Connaughton VP, Behar TN, Liu W-LS, Massey S. Immunocytochemical localization of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in the zebrafish retina. Visual Neuroscience. 1999;16:483–490. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899163090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connaughton VP, Maguire G. Differential expression of voltage-gated K+ and Ca2+ currents in bipolar cells in the zebrafish retinal slice. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;10:1350–1362. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connaughton VP, Nelson R. Glutamate-gated currents and glutamate receptors on zebrafish retinal bipolar cells. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1998;39:S982. [Google Scholar]

- de la Villa P, Kurahashi T, Kaneko A. L-Glutamate-induced responses and cGMP-activated channels in three subtypes of retinal bipolar cells dissociated from the cat. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:3571–3582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03571.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH, Schwartz EA. Kainate receptors mediate synaptic transmission between cones and ‘Off’ bipolar cells in mammalian retina. Nature. 1999;397:157–160. doi: 10.1038/16462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euler T, Schneider H, Wässle H. Glutamate responses of bipolar cells in a slice preparation of the rat retina. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:2934–2944. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-02934.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famiglietti EV, Jr, Kaneko A, Tachibana M. Neuronal architecture of On and Off pathways to ganglion cells in carp retina. Science. 1977;190:1267–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.73223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant GB, Dowling JE. A glutamate-activated chloride current in cone-driven ON bipolar cells of the white perch retina. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:3852–3862. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03852.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant GB, Dowling JE. ON bipolar cell responses in the teleost retina are generated by two distinct mechanisms. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:3842–3849. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harveit E. Membrane currents evoked by ionotropic glutamate receptor agonists in rod bipolar cells in the rat retinal slice preparation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:401–422. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano AA, MacLeish PR. Glutamate and 2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate evoke and increase in potassium conductance in retinal bipolar cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:805–809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida AT, Stell WK, Lightfoot DO. Rod and cone inputs to bipolar cells in goldfish retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1980;191:315–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901910302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko A, Tachibana M. Retinal bipolar cells with double colour-opponent receptive fields. Nature. 1981;293:220–222. doi: 10.1038/293220a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. The morphology of the bipolar cells, amacrine cells and ganglion cells in the retina of the turtle Pseudemys scripta elegans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 1982;B 298:355–393. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1982.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasansky A. Properties of depolarizing bipolar cell responses to central illumination in salamander retinal slices. Brain Research. 1992;576:181–196. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maple BR, Wu SM. Synaptic inputs mediating bipolar cell responses in the tiger salamander retina. Vision Research. 1997;36:4015–4023. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani AP. Giant bistratified bipolar cells in monkey retina. Anatomical Record. 1983;206:215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Masu M, Iwakabe H, Togawa Y, Miyoshi T, Yamashita M, Fukuda Y, Sasaki H, Hiroi K, Nakamura Y, Shigemoto R, Takada M, Nakamura K, Nakao K, Katsuki M, Nakanishi S. Specific deficit of the ON response in visual transmission by targeted disruption of the mGluR6 gene. Cell. 1995;80:757–765. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Ohtsuka T, Shimazaki H. Effects of aspartate and glutamate on the bipolar cells in the carp retina. Vision Research. 1975;15:456–458. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(75)90101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Iwakabe H, Akazawa C, Nawa H, Shigemoto R, Mizuno N, Nakanishi S. Molecular characterization of a novel retinal metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR6 with a high agonist selectivity for L-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:11868–11873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi S. Molecular diversity of glutamate receptors and implications for brain functions. Science. 1992;258:597–603. doi: 10.1126/science.1329206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawy S. The metabotropic receptor mGluR6 may signal through Go, but not phosphodiesterase, in retinal bipolar cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:2938–2944. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-02938.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawy S, Copenhagen DR. Multiple classes of glutamate receptor on depolarizing bipolar cells in retina. Nature. 1987;325:56–58. doi: 10.1038/325056a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawy S, Copenhagen DR. Intracellular cesium separates two glutamate conductances in retinal bipolar cells of goldfish. Vision Research. 1990;30:967–972. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(90)90105-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawy S, Jahr CE. Suppression by glutamate of cGMP-activated conductance in retinal bipolar cells. Nature. 1990;346:269–271. doi: 10.1038/346269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Correction for liquid junction potentials in patch clamp experiments. In: Rudy B, Iverson LE, editors. Methods in Enzymology Ion Channels. Vol. 207. San Diego, California: Academic Press; 1992. pp. 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R, Kolb H. Synaptic patterns and response properties of bipolar and ganglion cells in the cat retina. Vision Research. 1983;23:1183–1195. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin J-P, Duvoisin R. Review: Neurotransmitter receptors. I. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and function. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Kondo H, Toyoda J-I. Ionic mechanisms of two types of On-center bipolar cells in the carp retina. I. The responses to central illumination. Journal of General Physiology. 1979;73:73–90. doi: 10.1085/jgp.73.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Kujiraoka T. Physiological and morphological identification of two types of on-center bipolar cells in the carp retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1982;205:161–170. doi: 10.1002/cne.902050207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Kujiraoka T, Tomohide Y, Chino Y. Reexamination of photoreceptor-bipolar connectivity patterns in carp retina: HRP-EM and Golgi-EM studies. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1985;236:141–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.902360202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Kaneko A. L-Glutamate-induced responses in OFF-type bipolar cells of the cat retina. Vision Research. 1996;36:787–795. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(95)00176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholes JH. Colour receptors, and their synaptic connexions, in the retina of a cyprinid fish. The Journal of Physiology. 1975;270:61–118. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1975.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry DM, Yazulla S. Goldfish bipolar cells and axon terminal patterns: a Golgi study. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;329:188–200. doi: 10.1002/cne.903290204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter MM, Miller RF. 2-Amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid: a new pharmacological tool for retina research. Science. 1981;211:182–184. doi: 10.1126/science.6255566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stell WK. The structure and relationships of horizontal cells and photoreceptor-bipolar synaptic complexes in goldfish retina. American Journal of Anatomy. 1967;121:401–424. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001210213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stell WK, Ishida AT, Lightfoot DO. Structural basis for On- and Off-center responses in retinal bipolar cells. Science. 1977;198:1269–1271. doi: 10.1126/science.201028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stretton AOW, Kravitz EA. Neuronal geometry: determination with a technique of intracellular dye injection. Science. 1968;162:132–134. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3849.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreson WB, Miller RF. Actions of (1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (1S,3R-ACPD) in retinal ON bipolar cells indicate that it is an agonist at L-AP4 receptors. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;103:1019–1034. doi: 10.1085/jgp.103.6.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian N, Slaughter MM. Pharmacological similarity between the retinal APB receptor and the family of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;71:2258–2268. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian N, Slaughter MM. Functional properties of a metabotropic glutamate receptor at dendritic synapses of ON bipolar cells in the amphibian retina. Visual Neuroscience. 1995;12:755–765. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800009019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werblin F. Transmission along and between rods in the tiger salamander retina. The Journal of Physiology. 1978;280:449–470. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M, Wässle H. Responses of rod bipolar cells isolated from the rat retina to the glutamate agonist 2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (APB) Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:2372–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-08-02372.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]