Abstract

Local anaesthetics such as lidocaine (lignocaine) interact with sodium channels in a manner that is exquisitely sensitive to the voltage-dependent conformational state of the ion channel. When depolarized in the presence of lidocaine, sodium channels assume a long-lived quiescent state. Although studies over the last decade have localized the lidocaine receptor to the inner aspect of the aqueous pore, the mechanistic basis of depolarization-induced ‘use-dependent’ lidocaine block remains uncertain.

Recent studies have shown that lowering the extracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]o) and mutations in the sodium channel outer P-loop modulate occupancy of a quiescent ‘slow’ inactivated state with intermediate kinetics (termed IM) that involves structural rearrangements in the outer pore.

Site-directed mutagenesis and ion-replacement experiments were performed using voltage-clamped Xenopus oocytes and cultured (HEK-293) cells expressing wild-type and mutant rat skeletal muscle (μ1) sodium channels.

Our results show that lowering [Na+]o potentiates use-dependent lidocaine block. The effect of [Na+]o is maintained despite a III-IV linker mutation that partially disrupts fast inactivation (F1304Q). In contrast, the effect of lowering [Na+]o on lidocaine block is reduced by a P-loop mutation (W402A) that limits occupancy of IM.

Our findings are consistent with a simple allosteric model where lidocaine binding induces channels to occupy a native slow inactivated state that is inhibited by [Na+]o.

Lidocaine (lignocaine) and its analogues, compounds that suppress Na+ current (INa), are used as local anaesthetics and as therapies for cardiac arrhythmias and epilepsy. When depolarized, Na+ channels only transiently conduct ions due to rapidly developing (fast) inactivation (Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952), a conformational change involving amino acid residues in the III-IV interdomain linker (Stühmer et al. 1989; West et al. 1992) and vicinal sites near the inner surface of the channel (McPhee et al. 1994, 1995, 1998; Smith & Goldin, 1997; Lerche et al. 1997; Filatov et al. 1998; Tang et al. 1998). While drug-free Na+ channels quickly recover from fast inactivation between depolarizing stimuli, lidocaine delays such recovery, inducing a stable non-conducting state that results in cumulative reduction in INa with brief, repetitive stimuli (so-called ‘use-dependent block’) (Courtney, 1975). Lidocaine binds to amino acids positioned on the intracellular side of the putative selectivity filter (Ragsdale et al. 1994, 1996; Sunami et al. 1997), near (and perhaps overlapping) the fast-inactivation gating structures (Bennett et al. 1995).

A high-affinity binding interaction between lidocaine and the fast inactivated conformational state is a structural hypothesis for use-dependent local anaesthetic block supported by compelling, but circumstantial, experimental evidence (Hille, 1977; Hondeghem & Katzung, 1977; Cahalan, 1978; Yeh, 1978; Bean et al. 1983; Balser et al. 1996b). Surprisingly, a recent study found that amino acid residues intimately involved in fast inactivation recover to their pre-inactivated conformation rapidly, even while conduction is fully suppressed by lidocaine (Vedantham & Cannon, 1999), casting doubt on the prevailing notion that lidocaine arrests Na+ channels in the fast inactivated conformational state. In rare circumstances such as prolonged depolarization, Na+ channels may assume slow inactivated conformations from which recovery is considerably delayed (Adelman & Palti, 1969; Chandler & Meves, 1970; Rudy, 1978). One such slow inactivated state with ‘intermediate’ kinetics (Cummins & Sigworth, 1996; Hayward et al. 1996) is influenced by externally positioned residues in the outer pore region (μ1-W402) (Balser et al. 1996a; Kambouris et al. 1998; Benitah et al. 1999).

Earlier studies (Cahalan & Almers, 1979) suggested that external Na+ opposed the use-dependent action of charged (quaternary) lidocaine derivatives through a competitive ‘knock-off’ mechanism. However, recent studies have shown that external Na+ also prevents Na+ channels from entering slow inactivated states (Townsend & Horn, 1997), including an inactivated state of ‘intermediate’ stability (denoted IM) (Benitah et al. 1999). Moreover, earlier studies proposed that local anaesthetic action involves a gating conformational change linked to a stable inactivated state (Khodorov et al. 1976; Zilberter et al. 1991), and we recently showed that an outer pore (P-loop) mutation that opposes IM also reduces use-dependent lidocaine action (Kambouris et al. 1998). Here we examine the possibility that this gating effect of external Na+, inhibition of IM, plays a role in Na+ antagonism of use-dependent lidocaine action. Our data show that augmenting slow inactivation by lowering the extracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]o) sensitizes the Na+ channel to use-dependent lidocaine action, even when fast inactivation is disabled (μ1-F1304Q). Moreover, the effects of lowering [Na+]o on slow inactivation and lidocaine action are decreased by the P-loop mutation that opposes IM (W402A). Our findings are consistent with a simple allosteric model where lidocaine binding induces channels to occupy a native slow inactivated state that is inhibited by [Na+]o.

METHODS

Molecular biology

Site-directed mutagenesis of the μ1 Na+ channel α subunit (Trimmer et al. 1989) was performed on a full-length cDNA clone encoding the wild-type μ1 channel using a PCR-based method (Weiner et al. 1993). Both sense and antisense oligonucleotides (30-34mer) containing the desired mutation(s) were used as primers for amplification with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The PCR product was treated with DpnI to select for the mutant plasmid and then transformed into E. coli for subsequent isolation and purification using standard protocols. Both modifications (W402A, F1403Q) were confirmed by di-deoxy sequencing of the region of the α subunit containing the mutation and by electrophysiological characterization of, at least, two independent mutagenic clones (Lawrence et al. 1996; Kambouris et al. 1998). In vitro mRNA transcription was performed using the SP6 promoter region and commercially available reagents (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA).

Ion channel expression

All procedures surrounding the care and use of Xenopus laevis conformed with our institution animal care committee guidelines. Oocytes were harvested from human chorionic gonadotropin-primed adult females (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI, USA) after 30 min of submersion anaesthesia in an aqueous solution containing 0.17 % 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester (methanesulphonate salt, Sigma). Following survival surgery, the animals were allowed to recover in shallow water to maintain head out position until awake (∼30 min). Oocytes were isolated by digestion in a 2 mg ml−1 solution of collagenase (Type IA; Sigma) and stored in a modified Barth's solution containing (mM): NaCl, 88; KCl, 1; NaHCO3, 2.4; Tris base, 15; Ca(NO3)2.4H2O, 0.3; CaCl2.6H2O, 0.41; MgSO4.7H2O, 0.82; sodium pyruvate, 5; theophylline, 0.5; supplemented with penicillin, 100 U ml−1; streptomycin, 100 μg ml−1; fungizone, 250 ng ml−1 and gentamicin, 50 μg ml−1. Oocytes were injected with 50 nl of a 0.1–0.25 μg μl−1 solution of cRNA transcribed from wild-type or mutant cDNA. In all oocyte experiments, an equimolar ratio of similarly transcribed rat brain β1 subunit RNA was co-injected with the α subunit cRNA.

For expression in human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells, the wild-type μ1 α subunit was subcloned into the vector HindIII- XbaI site of the vector GFPIRS for bicistronic expression of the channel protein and GFP reporter as previously described (Johns et al. 1997). Cells were transfected with this plasmid using lipofectamine (Gibco), and were cultured in modified Eagle's medium (MEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin in a 5 % CO2 incubator at 37°C for 1–3 days. The HEK cells were not transfected with the Na+ channel β1 subunit. Cells exhibiting green fluorescence were chosen for electrophysiological analysis.

Electrophysiology and data analysis

Whole-cell Na+ current (INa) was recorded from Xenopus oocytes using a two-electrode voltage clamp, OC-725B (Warner Instrument Corp., Hamden, CT, USA), 1–3 days after cRNA injection. Currents were measured using electrodes of 1–3 MΩ resistance when filled with 3 M KCl. Currents were recorded in frog Ringer (ND-96) solution containing (mM): NaCl, 96; KCl, 2; MgCl2, 1; Hepes, 5; pH 7.6, and [Na+]o was reduced to 25 or 10 mM by equimolar replacement with N-methyl-D-glucamine-chloride (NMGCl). INa was recorded from HEK-293 cells using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). Electrode resistances were 1–3 MΩ when filled with a pipette solution containing (mM): NaF, 140; NaCl, 10; EGTA, 5; Hepes, 10 (pH 7.40). Series resistance was ∼85 % compensated. The 150 mM Na+ bath solution contained (mmol l−1): NaCl, 150; KCl, 4.5; CaCl2, 1.5; MgCl2, 1; Hepes, 10 (titrated to pH 7.40 with NaOH). [Na+]o was reduced to 10 mM by equimolar replacement with NMGCl. In both oocyte and HEK cell experiments, junction potentials were minimized during bath solution changes by using a 3 M KCl-agar bridge. Inactivation gating kinetics and use-dependent block were assessed using voltage-clamp protocols described in the text and figure legends. In all cases, lidocaine HCl (2 % preservative free; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA) was added to the bathing solution at concentrations indicated in the text. In experiments where lidocaine was used, a recovery period at −100 mV of at least 20 s was allowed prior to each set of measurements in order to avoid cumulative use-dependent block. All electrophysiological recordings were made at room temperature (20–22°C).

Multi-exponential functions were fitted to the data using non-linear least-squares methods (Microcal Origin version 4.10, Microcal Software Inc., Northampton, MA, USA) to determine the amplitudes and time constants associated with development or recovery from slow inactivation or use-dependent block. Pooled data are expressed as the means ± s.e.m., and statistical comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA (Origin) with P ≤ 0.05 indicating significance. A Markov gating scheme (Fig. 5) was evaluated using numerical integration methods tailored for stiff sets of differential equations (Hindmarsh, 1983; Petzold, 1983) and linked to custom-written software (Balser et al. 1990). Model parameters were minimized by fitting data from four conditions simultaneously (high/low [Na+]o, ± lidocaine) using a simplex-based global fitting method described previously (Tomaselli et al. 1995) and as discussed in the legend of Fig. 5.

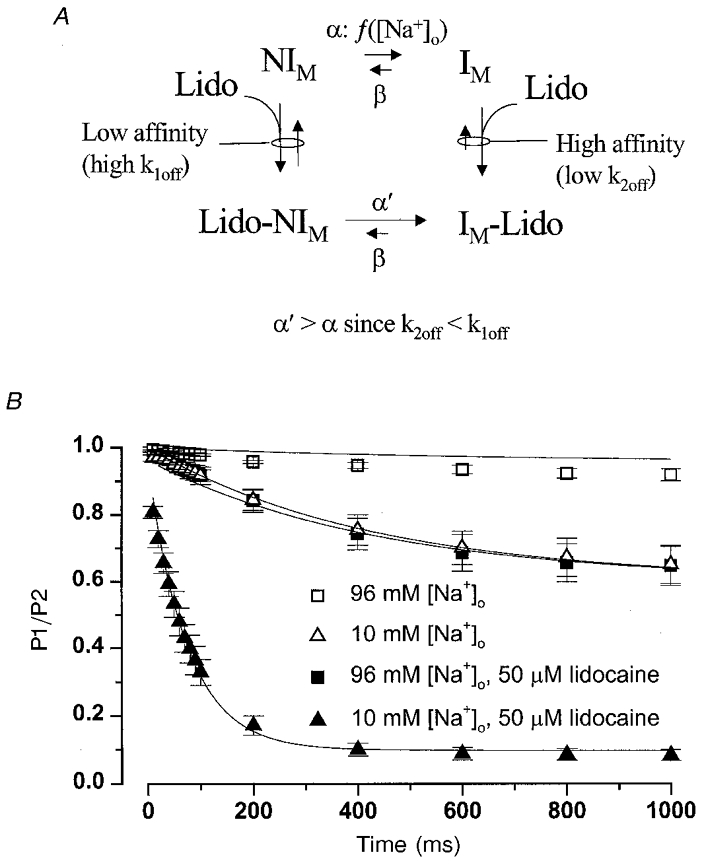

Figure 5. A model for lidocaine block that invokes [Na+]o-dependent slow inactivation.

A, in this two-affinity modulated receptor model, IM represents the slow inactivated state for which lidocaine has high affinity, while NIM represents all other states (closed, open, fast inactivated) for which lidocaine has lower affinity. The forward rate constant controlling slow inactivation in drug-free conditions (α) was allowed to differ in 96 mM vs. 10 mM [Na+]o, and the forward rate constant for slow inactivation with lidocaine bound (α′) was determined by α and the lidocaine off-rates (k2off, k1off) from detailed balances (eqn (1)). The lidocaine kon was fixed at 108 m−1 s−1 (see text). The remaining rate constants (β, k2off, k1off) were derived from fitting the model to the data, but were constrained to be the same in high or low [Na+]o. In the model, both lidocaine-bound states (Lido-NIM, IM-Lido) were considered to be non-conducting, so that NIM is the only state where channels are available to open and conduct Na+. B, the data shown were replotted from Fig. 1B and C. The ordinate (P2/P1) represents the probability that channels are not slow inactivated, and are therefore available to open. Using a numerical integration method (Methods), the model was evaluated at each time point (abscissa, Fig. 5B) and the calculated probability of occupying the NIM state was compared directly to the P2/P1 data value. At t = 0, the probability of occupying the NIM state was set to 1.0 (P2/P1 = 1.0). The model was fitted to the data in four conditions (high/low [Na+]o, ± lidocaine) simultaneously using a simplex-based global fitting approach (Nelder & Mead, 1965) that updates the parameters to minimize the sum-of-squares error. Continuous lines show the non-linear least-squares fit of the model to the mean 10 mM and 96 mM [Na+]o data. Fitted parameters for the rate constants controlling slow inactivation were: α in 96 mM [Na+]o = 0.063 s−1, α in 10 mM [Na+]o = 0.92 s−1, and β = 1.41 s−1. Fitted values for lidocaine k1off and k2off were 127 × 103 s−1 and 386 s−1, giving Kd values for the NIM and IM states of 1.27 mM and 3.86 μM, respectively.

RESULTS

Effects of lowering [Na+]o on use-dependent lidocaine block

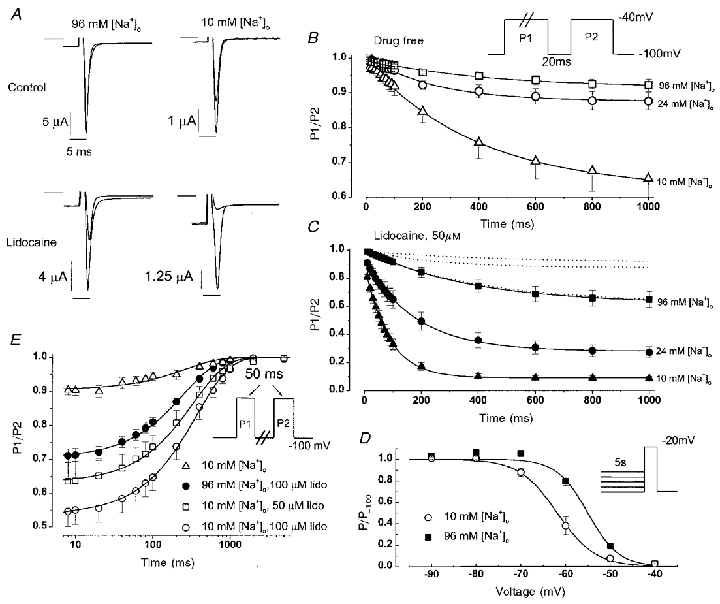

During brief depolarizations, μ1 Na+ channels recover from inactivation rapidly in physiological (96 mM) [Na+]o when the β1 subunit is coexpressed (Cannon et al. 1993; Chang et al. 1996). Figure 1A shows pairs of Na+ currents elicited at the beginning of a 1 s depolarization (P1), and a second current (superimposed) recorded at the same membrane potential (P2) after a brief (20 ms) recovery interval at −100 mV. Under these conditions, fast inactivated channels recover in < 10 ms; hence, any reduction in INa during the P2 pulse reflects slow inactivation (IM). In 96 mM [Na+]o, (Fig. 1A, left top) peak INa during the P2 pulse is only slightly decreased relative to P1 (92 ± 2 %, n = 7), confirming that little IM occurs normally. However, lowering [Na+]o to 10 mM (Fig. 1A, right top) increased entry into IM (P2: 65 ± 6 % of P1, n = 8). While reducing [Na+]o decreased the magnitude of INa, the current was within an acceptable range for voltage control in either [Na+]o. In Fig. 1B, the duration of the P1 pulse was varied from 10 ms to 1 s to examine the rate at which IM develops. Summary data (shown for 10, 24, and 96 mM [Na+]o) are well-fitted by a single exponential function (continuous lines, fit parameters in Table 1), suggesting occupancy of a single slow inactivated state. The development of a single slow inactivated state with intermediate kinetics under these conditions (with β1 subunit coexpression) is consistent with previous results in oocytes (Featherstone et al. 1996; Kambouris et al. 1998). However, depolarizations of similar duration in mammalian expression systems (Hayward et al. 1997) or longer depolarizations in oocytes (minutes; Todt et al. 1999) recruit additional slow kinetic components with longer time constants for recovery. Previous studies suggest that these more stable inactivated states do not influence lidocaine block (Kambouris et al. 1998).

Figure 1. The effects of [Na+]o on slow inactivation and use-dependent lidocaine block.

A, whole-cell currents recorded from Xenopus oocytes in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of 50 μM lidocaine. Oocytes were bathed in solutions containing either 96 mM (left) or 10 mM [Na+]o (right). The superimposed current pairs were recorded at the beginning of a pulse of 1000 ms duration to −40 mV (holding potential −100 mV, bar indicates zero current level) and then during a second pulse to −40 mV which followed a 20 ms of recovery period at −100 mV. B, symbols indicate peak INa (means ± s.e.m.) during the P2 pulse relative to the P1 pulse with varying P1 pulse durations (protocol inset). Oocytes were bathed in either 96 mM [Na+]o (n = 7), 24 mM [Na+]o (n = 13), or 10 mM [Na+]o (n = 8). Continuous lines are single exponential fits (y = y0 + Aexp(-t/τ)) to the mean data; kinetic parameters derived from fitting data measured in individual oocytes are summarized in Table 1. C, the symbols show data obtained in an identical manner in solutions containing 50 μM lidocaine and either 96 mM [Na+]o (n = 10), 24 mM [Na+]o (n = 7), or 10 mM [Na+]o (n = 8). Continuous lines show single exponential fits to the mean data (parameters summarized in Table 1). Dotted lines show the results in drug-free conditions (from panel B) for comparison. D, voltage-dependent availability is plotted for oocytes bathed in 10 mM [Na+]o (n = 9) or 96 mM [Na+]o (n = 5). The continuous lines are Boltzman equations (1 + exp(V–V½/δ))−1 fitted to the mean data. Summary values for the mid-point (V½) and slope factor (δ) were, respectively, −62.0 ± 1.5 and 3.4 ± 0.2 mV in 10 mM [Na+]o, and −55.4 ± 0.7 and 3.5 ± 0.2 mV in 96 mM [Na+]o. V½ values in 96 and 10 mM [Na+]o differed significantly (P = 0.01). E, slow time-dependent recovery of availability following a 50 ms depolarization to −20 mV is plotted over an 8–5000 ms range. Recovery components more rapid than 8 ms (fast inactivation, deactivation) are not considered. Data are from oocytes bathed in 10 mM [Na+]o (n = 10), 96 mM [Na+]o + 100 μM lidocaine (n = 12), 10 mM [Na+]o + 50 μM lidocaine (n = 7) and 10 mM [Na+]o + 100 μM lidocaine (n = 6). Continuous lines are single exponential fits (y = y0 + A(1 – exp(-t/τ))) to the mean data; kinetic parameters are given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for development of IM

| 96 mm[Na+]o | 24 mm[Na+]o | 10 mm[Na+]o | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lidocaine | A | τ (ms) | A | τ (ms) | A | τ (ms) |

| 0 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 462 ± 119 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 264 ± 44 | 0.38 ± 0.05* | 452 ± 31 |

| 50 μm | 0.39 ± 0.06 | 389 ± 39 | 0.68 ± 0.03* | 201 ± 34* | 0.83 ± 0.02* | 86 ± 9* |

The function y = y0 + Aexp(-t/τ) was fitted to the data in Fig. 1, panels B and C, and the values (means ± s.e.m.) for A and τ are shown.

Value differed significantly from data measured under the same conditions in 96 mm [Na+]o.

Figure 1A (lower, left) shows that in 96 mM [Na+]o, 50 μM lidocaine caused a reduction in P2 peak INa (65 ± 6 % of P1, n = 7) that was similar in magnitude to lowering [Na+]o to 10 mM in drug-free solutions. Lowering [Na+]o to 10 mM while in lidocaine (Fig. 1A, bottom, right) dramatically augmented use-dependent block (P2: 8.5 ± 2 %, n = 10). Notably, the lidocaine-associated block was entirely dependent on the preceding depolarization (i.e. was use dependent). Even 100 μM lidocaine did not block the current elicited by the first pulse (P1) after a long hyperpolarization in either 10 mM [Na+]o (peak INa 99 ± 11 % of control, n = 12) or 96 mM [Na+]o (99 ± 9 %, n = 10). Figure 1C shows the time course for development of use-dependent lidocaine block as the length of the P1 pulse was extended from 10 ms to 1 s (note ordinate difference from Fig. 1B). The results in drug-free conditions (from Fig. 1B) are shown as dotted lines. As before, the time-dependent loss of availability was well fitted by a single exponential (continuous line). Both the rate and extent of use-dependent block were augmented by lowering [Na+]o from 96 to 10 mM. The time constant for block development decreased from 389 ± 39 ms in 96 mM [Na+]o to 86 ± 9 ms in 10 mM [Na+]o (P < 10−6, Table 1).

If inducing slow inactivation plays a major role in use-dependent lidocaine ‘block’, then recovery from use-dependent block should recapitulate recovery from IM. Moreover, increasing the lidocaine concentration should increase the extent of use-dependent block, but should not alter the rate at which channels recover availability. Figure 1E shows the fraction of channels available to open (P2/P1) as the recovery interval at −100 mV is lengthened following a brief depolarization to −20 mV. A single exponential was fitted to fractional recovery data spanning an 8 to 5000 ms time range (continuous lines). In lidocaine-free solutions, the time constant for recovery from IM was 335 ± 87 ms (10 mM [Na+]o, Table 2), consistent with earlier results linking varying [Na+]o (Benitah et al. 1999) and outer pore mutations (Kambouris et al. 1998) to IM. In 50 and 100 μM lidocaine, the total number of channels exhibiting slow recovery progressively increased (i.e. the y intercept decreased), but the time constant for slow recovery was unchanged (see Table 2). Hence, the rate of recovery from lidocaine block was concentration independent and was kinetically indistinguishable from recovery from IM.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for recovery from Im

| Lidocaine | [Na+]o | A | τ (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 mm | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 335 ± 87 |

| 50 μm | 10 mm | 0.38 ± 0.06* | 360 ± 74 |

| 100 μm | 10 mm | 0.47 ± 0.04* | 368 ± 58 |

| 100 μm | 96 mm | 0.29 ± 0.02* | 252 ± 12** |

The function y = y0 + A(1 − exp(−t/τ)) was fitted to the data in Fig. 1, panel E. Fitted parameters (means ± s.e.m.) are shown. Lidocaine increased the fraction of slowly recovering channels

(P < 0·0001 versus 0 μm lidocaine, 10 mm [Na+]o). In 10 mm [Na+]o, lidocaine did not change the time constant for slow recovery (τ), although in 100 μm lidocaine raising [Na+]o from 10 to 96 mm significantly decreased τ

(P = 0·02).

Lidocaine induces a hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of INa availability (Bean et al. 1983), implying lidocaine-bound channels occupy a stabilized inactivated state. We therefore examined how [Na+]o influences voltage-dependent availability of INa. The time constant for development of IM was consistently ≤ 500 ms (Table 1); hence, 5 s prepulses (Fig. 1D, inset) were used to achieve steady-state occupancy of IM while minimizing recruitment of even more stable (ultra-slow) inactivated states seen with longer (∼1 min) depolarizations (Kambouris et al. 1998; Todt et al. 1999). Figure 1D shows that lowering [Na+]o induced a 7 mV hyperpolarizing shift in steady-state availability, consistent with the notion that external Nao+ destabilizes IM (Benitah et al. 1999). In this case, if use-dependent lidocaine block requires stable occupancy of IM, then raising [Na+]o should speed recovery from lidocaine block. Figure 1E shows that raising [Na+]o to 96 mM not only reduced the extent of slow inactivation (filled vs. open circles in 100 μM lidocaine), but also speeded the time constant for recovery from block (Table 2: 252 ± 12 ms vs. 368 ± 58 ms, P = 0.02).

Effect of lowering [Na+]o on lidocaine block in a fast-inactivation mutant

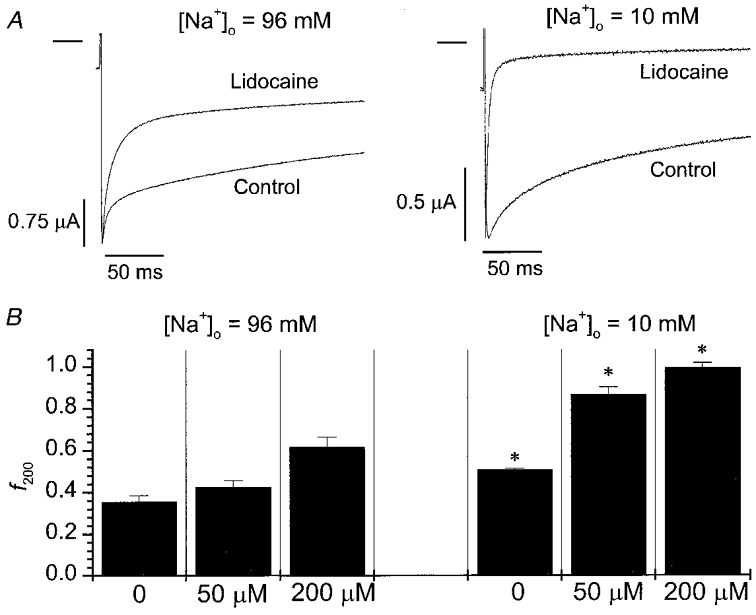

The kinetic overlap between fast inactivation and entry into IM in low [Na+]o makes it difficult to rule out the possibility that the inhibitory effect of [Na+]o on lidocaine block is due to an indirect effect on fast inactivation. We therefore examined the interaction between [Na+]o and lidocaine block in mutant μ1 channels with impaired fast inactivation (F1304Q) (West et al. 1992; Lawrence et al. 1996). Figure 2A shows slowly decaying F1304Q currents during a 200 ms depolarization in 96 mM (left) or 10 mM [Na+]o (right) before and during exposure to lidocaine (200 μM). In drug-free conditions, the slow decay of F1304Q current has been linked to slow inactivation (Townsend & Horn, 1997). The rate of this slow decay is increased either by lowering [Na+]o (Fig. 2A, see also Townsend & Horn, 1997) or by lidocaine (Fig. 2A and Balser et al. 1996b). Moreover, lowering the [Na+]o to 10 mM potentiated the effect of lidocaine, markedly speeding F1304Q current decay (Fig. 2A, right). In Fig. 2B these [Na+]o-dependent differences in lidocaine action are summarized by plotting the fraction of peak current remaining 200 ms into the depolarizing pulse (f200). Lowering [Na+]o from 96 to 10 mM hastened the current decay of F1304Q produced by either 50 or 200 μM lidocaine (P < 0.001). Hence, in conditions where IM is facilitated (by low [Na+]o) and fast inactivation is destabilized, low concentrations of lidocaine rapidly induce the formation of a stable non-conducting state when the membrane is depolarized.

Figure 2. Interaction between [Na+]o and lidocaine block in F1304Q channels.

A, whole-oocyte currents elicited at −20 mV (holding potential −100 mV, bar indicates zero current level) before and during lidocaine exposure (200 μM) in either 96 mM [Na+]o (left) or 10 mM [Na+]o (right). Lidocaine enhanced the decay of whole-cell current to a greater extent when [Na+]o was reduced. B, summary data plotting the fractional reduction in current by 200 ms (f200) at −20 mV in 96 mM [Na+]o (control n = 8, 50 μM lidocaine n = 8, 200 μM lidocaine n = 8) or 10 mM [Na+]o (control n = 7, 50 μM lidocaine n = 4, 200 μM lidocaine n = 5). At each lidocaine concentration (0, 50, 200 μM), current decay was hastened by lowering [Na+]o from 96 to 10 mM (*P < 0.001).

Lidocaine block in a mutant channel with impaired slow inactivation

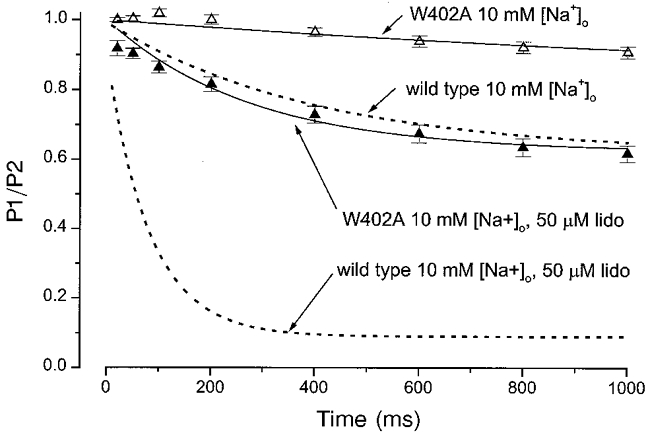

Previous work has shown that mutation of a P-loop tryptophan (μ1-W402) reduces an intermediate kinetic component of slow inactivation (IM) (Balser et al. 1996a). Alanine replacement (W402A) primarily attenuates the IM state (in preference to more long-lived slow inactivated states), and also reduces use-dependent lidocaine block (Kambouris et al. 1998). However, this correlation between reduction of IM and reduced lidocaine block could be fortuitous: the mutation could modify slow inactivation gating and the lidocaine receptor (directly or indirectly) through independent mechanisms. Nonetheless, if augmentation of lidocaine block by low [Na+]o was attenuated by the W402A mutation, the hypothesis of a mechanistic linkage between IM occupancy and lidocaine block would be strengthened. Figure 3 shows the time course for development of slow inactivation (open symbols) and use-dependent lidocaine block (filled symbols) in W402A channels bathed in 10 mM [Na+]o. The continuous lines are single exponential fits to these data. The comparable exponential fits to the wild-type data (from Fig. 1B and C) are shown by the dashed lines. In drug-free conditions, the IM state developed more slowly (τ = 1870 ms) and less fully (A = 0.19) in the W402A channel relative to the wild-type channel (Table 1, comparable parameters for wild-type were: τ = 452 ms, A = 0.38). In 50 μM lidocaine, the rate (τ = 274 ms) and extent (A = 0.38) of use-dependent block was similarly reduced compared to wild type (Table 1, τ = 86 ms, A = 0.83). Hence, the W402A mutation reduced the slow inactivation normally induced by lowering [Na+]o and at the same time inhibited the development of use-dependent lidocaine block in low [Na+]o. These findings suggest that external Na+ and the P-loop mutation both modulate use-dependent lidocaine action through effects on the IM state.

Figure 3. Lidocaine block of a mutant channel (W402A) with impaired slow inactivation.

The time course for development of slow inactivation (▵, n = 6) and use-dependent lidocaine block (▴, n = 6) is shown for W402A channels bathed in 10 mM [Na+]o. The continuous lines are single exponential fits to these data (similar to Fig. 1, parameters given in text). Comparable results in wild-type channels at the same [Na+]o (from Fig. 1B and C) are shown by the dashed lines. Compared to wild type, the W402A mutation markedly reduced the extent of slow inactivation in 10 mM [Na+]o, and also significantly reduced the development of use-dependent lidocaine (lido) block in 10 mM [Na+]o.

Electrochemical gradient and use-dependent block

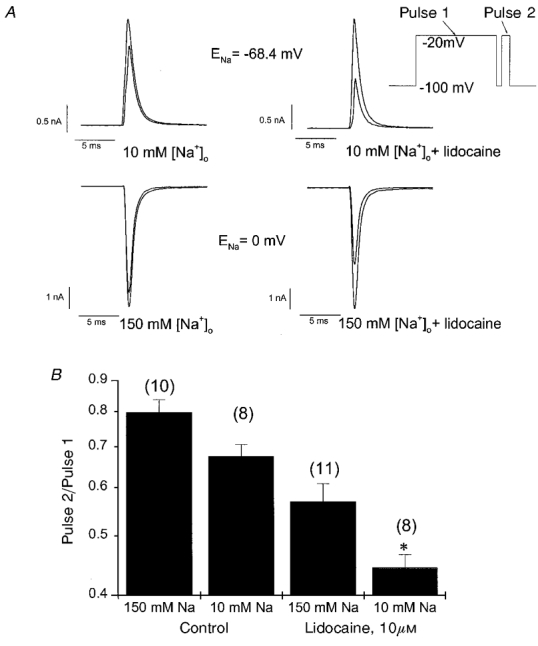

These findings point toward a mechanistic link between occupancy of the IM state and use-dependent lidocaine action. However, all the currents measured in the oocyte experiments were inward (Fig. 1A) and lidocaine block consistently increased in parallel with a reduced electrochemical gradient for Na+ (Fig. 1C). We therefore re-examined the effect of lowering [Na+]o on lidocaine block in μ1 Na+ channels expressed in HEK-293 cells using the whole-cell voltage-clamp method (see Methods). Using this approach, we could raise [Na]i to 150 mM, and thereby induce outward currents in low [Na+]o at typical depolarized membrane potentials. Figure 4A shows INa measured before (left) and during (right) exposure to 10 μM lidocaine in either 10 mM [Na+]o (top) or 150 mM [Na+]o (bottom). In each panel, the superimposed Na+ currents were elicited by an 800 ms depolarizing pulse to −20 mV and a subsequent brief (50 ms) pulse to the same membrane potential, separated by a 20 ms interval at −100 mV to allow recovery from fast inactivation (protocol inset, Fig. 4A). Hence, the fractional decrement in peak INa between the superimposed currents (pulse 2/pulse 1) reflects slow inactivation or use-dependent lidocaine block. Although the macroscopic currents were somewhat smaller in cells bathed in low [Na+]o due to gating effects, the absolute driving force for Na+ flux through the open channel at −20 mV was 28 mV greater in 10 mM [Na+]o (+48 mV vs. −20 mV). The left panels (drug free) indicate that slow inactivation was still 15 % greater in low [Na+]o despite the change in direction of current flow or the increased electrochemical gradient (summarized data Fig. 4B, left). Use-dependent current reduction in lidocaine was 23 % greater in low [Na+]o (right panels, Fig. 4A; summary data Fig. 4B, right). Lidocaine block increased under conditions where slow inactivation was enhanced even though the currents in low [Na+]o were outward and the electrochemical gradient driving INa was increased.

Figure 4. Na+ channel α subunits expressed in HEK-293 cells.

A, Na+ currents were recorded from HEK cells prior to (left) and during lidocaine exposure (right, 10 μM) in either 10 mM (top) or 150 mM [Na+]o (bottom). The pipette [Na]i was 150 mM, so that INa at −20 mV was outward in 10 mM [Na+]o (Vclamp – ENa = +48 mV), but inward in 150 mM [Na+]o (Vclamp – ENa = −20 mV). In each case, the first (larger) INa was elicited by an 800 ms depolarizing pulse to −20 mV, while the second (smaller) INa was recorded from a brief (50 ms) step to −20 mV that followed a 20 ms recovery interval at −100 mV (see inset voltage clamp protocol). B, the bar graph plots the fractional change in peak INa between the superimposed currents in panel A (pulse 2/pulse 1) for each of the four bath conditions. The number of cells recorded in each condition are shown in parentheses. *Significant difference from the matched condition in 150 mM [Na+]o (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In a previous paper (Kambouris et al. 1998) we reported that alanine mutation of a P-loop tryptophan (W402A), external to both the selectivity (DEKA) ring (Heinemann et al. 1992) and the putative local anaesthetic receptor in domain IV S6 (Ragsdale et al. 1994), unexpectedly reduced use-dependent lidocaine block. Since the W402A mutation also reduced IM, the results suggested the possibility that this component of slow inactivation gating and use-dependent lidocaine action are mechanistically linked. However, although these two effects of the mutation (gating and pharmacological) shared similar kinetic features, we could not exclude the possibility that the mutation modified IM and the local anaesthetic receptor through distinct mechanisms. Our rationale for the present study was to explore this potential linkage using a different, non-mutagenic approach. Our results show that lowering [Na+]o both augments entry into the IM state and potentiates use-dependent block by lidocaine (Fig. 1). With a view to bridging this result to our prior mutagenesis work (Kambouris et al. 1998), we show (Fig. 3) that W402A reduced the effect of lowering [Na+]o on both slow inactivation gating and lidocaine block, suggesting that [Na+]o and the P-loop mutation both modify lidocaine block through effects on the IM state. In addition, we find that these effects of [Na+]o on lidocaine action are not abolished by mutagenic disruption of fast inactivation (Fig. 2).

An allosteric model for lidocaine-induced use dependence

We considered whether the opposing effects of Nao+ and lidocaine on use-dependent channel availability could be rationalized by a modulated receptor scheme (Fig. 5A). For simplicity, all gated conformational states other than the slow inactivated state (IM) were grouped together as ‘available’ states for Na+ conduction (NIM). Included among the NIM states is the fast inactivated state, recognizing that (1) fast-inactivation gating structures recover rapidly despite use-dependent lidocaine block (Vedantham & Cannon, 1999) and (2) under the conditions of our protocol (Fig. 1) fast inactivated channels were allowed sufficient time to recover, and were therefore ‘available’ to open.

Discrete block of unitary current cannot be observed with lidocaine (Grant et al. 1989), so the true on-rate for lidocaine binding remains uncertain. Hence, we arbitrarily set the on-rate for lidocaine binding at a fixed upper limit approaching diffusion (108 m−1 s−1), and allowed the unbinding rates to determine the stabilities of the two (NIM and IM) drug-bound complexes. We further assumed that channels in the IM state have the higher affinity for lidocaine (i.e. a lower koff).

We allowed the forward rate constant for slow inactivation (α) to differ in 10 and 96 mM mM Nao+, but assumed (in the simplest case) the rate constant controlling recovery from slow inactivation (β) was not influenced by [Na+]o or drug binding (Fig. 1E), and was therefore constrained to be identical for drug-free (top of Fig. 5A) and drug-bound (bottom of Fig. 5A) channels. Based on these definitions and detailed balances, the forward rate constant for slow inactivation with lidocaine bound (α′) is explicitly defined as a function of α and the off-rates for lidocaine binding (k1off, k2off) as follows:

| (1) |

Since we assume lidocaine binds with greater affinity to the IM state (i.e. k2off < k1off), the rate of slow inactivation with lidocaine bound must exceed the rate under drug-free conditions (α′ > α). In this sense, the lidocaine action parallels that of allosteric effector molecules (Monod et al. 1965), where drug binding allosterically promotes an intrinsic channel conformation (i.e. slow inactivation). Figure 5B shows model fits (continuous lines) to the 10 mM and 96 mM [Na+]o data from Fig. 1B and C. The fitted rate constants and binding affinities (see legend) were all constrained to be identical in 10 and 96 mM [Na+]o, with the exception of α which decreased 15-fold as [Na+]o was raised, consistent with slowed development of IM. By speeding entry of drug-bound channels into the IM state, the model simulates the marked increase in the rate at which lidocaine ‘block’ develops when [Na+]o is reduced. The model converged on Kd values for the NIM and IM states (1.27 mM and 3.86 μM, respectively) that resemble previously determined experimental Kd values for tonic and ‘inactivated-state’ lidocaine block of skeletal muscle Na+ channels (Nuss et al. 1995).

Processes other than IM may influence use-dependent Na+ channel block

Sodium channel μ1 α subunits expressed in oocytes exhibit an unusual degree of slow (mode 2) gating and slow inactivation when the β1 subunit is omitted (Zhou et al. 1991). In the oocyte experiments (Figs 1-3), the β1 subunit was coexpressed in order to minimize these phenomena, and thereby more closely recapitulate the in vivo gating phenotype. However, use-dependent lidocaine block of Na+ channels expressed in oocytes is attenuated by β1 coexpression, a phenomenon that may result from β1 effects on slow gating (Balser et al. 1996c) or from a direct β1 interaction with the lidocaine receptor (Makielski et al. 1996). Thus, our intepretation of the lidocaine-[Na+]o interaction in oocytes could be confounded if there are changes in α-β1 coupling as [Na+]o changes. However, gating of the μ1 Na+ channel α subunit in cultured mammalian cells (in contrast to oocytes) is almost entirely rapid, regardless of whether the β1 subunit is coexpressed (Ukomadu et al. 1992). The experiments in Fig. 4 were performed without β1 subunit coexpression and recapitulated the results in oocytes, suggesting that these findings are not contingent on the expression system or variable α-β1 coupling.

Although our results cannot exclude the possibility that Nao+ inhibits use-dependent lidocaine action through a competitive or otherwise gating-independent mechanism, several factors support a role for slow inactivation. The wild-type Na+ channel occupies the open state (and conducts Na+ ions) for only a few milliseconds (coincident with peak INa), while use-dependent lidocaine ‘block’ develops over hundreds of milliseconds (Table 1, Fig. 1C), during a time period when channels are inactivated and non-conducting. Moreover, lowering the [Na+]o to 10 mM still produced no first-pulse (so-called ‘tonic’) block in 100 μM lidocaine (see Results, paragraph 2), a concentration that induces substantial use-dependent block under these conditions (Fig. 1C). At the same time, lowering [Na+]o enhanced IM entry and lidocaine-use dependence, while both effects were reduced by a mutant (W402A) that inhibits the same slow inactivation gating process (Fig. 3). Finally, use-dependent lidocaine block tracks the degree of slow inactivation in a manner independent of the electrochemical gradient for Na+ (Fig. 4).

Nonetheless, it remains possible that a competitive interaction between Na+ and lidocaine influences the results to some degree, especially if the two species interact at a site where Na+ occupancy correlates poorly with current magnitude. Further, while Nao+ probably inhibits slow inactivation through occupying a site external to the selectivity filter (Townsend & Horn, 1997), it is still conceivable that Nao+ and the W402A mutation modify slow inactivation and use-dependent lidocaine action via independent, albeit parallel mechanisms. A competitive interaction between Na+ and lidocaine in the permeation pathway could have influenced the F1304Q results (Fig. 2) given the much longer single-channel open time and high frequency of re-openings for this μ1 mutant (Lawrence et al. 1996). This could partly explain why lowering [Na+]o seemed to potentiate lidocaine suppression of F1304Q INa to a greater extent than wild type.

It is well known that cardiac (hH1) INa is more sensitive to use-dependent lidocaine action than skeletal muscle INa (Nuss et al. 1995; Wang et al. 1996). In light of recent reports that find slow inactivation is more prominent in the skeletal muscle isoform (Richmond et al. 1998), a positive interaction between slow inactivation and lidocaine sensitivity may seem paradoxical. However, the component of slow inactivation that is amplified in skeletal muscle has a kinetic signature (τ = ∼5–20 s) far slower than the ‘intermediate’ IM state discussed here (τ < 500 ms). Additionally, we have recently shown that hH1 channels recover from IM states more slowly than μ1 channels, and this may partly account for the enhanced ‘sensitivity’ of the cardiac isoform to use-dependent lidocaine action (Nuss et al. 2000).

Other differences between ‘classic’ slow inactivation and the IM state warrant discussion in this context. Most studies find that slow inactivation competes with fast inactivation (Rudy, 1978; Featherstone et al. 1996), whereas our prior studies suggest that fast inactivation and the IM state are positively coupled. After relatively brief periods of depolarization (< 100 ms) sufficient to induce IM but not ‘classic’ slow inactivation, μ1 channels carrying the III-IV linker IFM→QQQ mutation exhibited less slow inactivation than wild type (Balser et al. 1996a). In addition, following a 1 s depolarization, partly destabilizing fast inactivation (μ1F1304Q) hastened recovery from an intermediate (τ ∼500 ms) component of inactivation, but slowed recovery from a more stable (τ ∼5 s) inactivated state (Nuss et al. 1996). Taken together, these results support the notion that fast inactivation and IM are positively coupled, while fast inactivation and ‘classic’ slow inactivation are inversely coupled.

The mechanistic role of fast inactivation in lidocaine action remains unresolved. Accessibility of the III-IV linker to covalent modification is reduced by inactivation, but accessibility recovers rapidly with hyperpolarization, and this recovery is not slowed by use-dependent lidocaine block (Vedantham & Cannon, 1999). While this result would suggest use-dependent lidocaine action does not involve fast-inactivation gate ‘trapping’, mutations that severely disrupt fast inactivation (i.e. III-IV linker IFM→ QQQ) markedly attenuate use-dependent block of peak INa (Bennett et al. 1995). At the same time, lidocaine markedly accelerates the decay of whole-cell current through F1304Q channels during sustained depolarization (Balser et al. 1996b), and this effect is potentiated by reducing [Na+]o (Fig. 2). Whole-cell current decay through F1304Q channels in drug-free conditions is multiexponential, and prior studies suggest this represents entry into multiple inactivated states. Specifically, whole-cell (Nuss et al. 1996) and single-channel analyses (Lawrence et al. 1996; Townsend & Horn, 1997) suggest that the early, more rapid decay phase represents entry into a ‘destabilized’ fast inactivated state, while the slower decay that follows represents partitioning into more stable, slow inactivated states. Hence, prior studies have suggested that lidocaine may influence fast inactivation gating in III-IV linker mutants by ‘repairing’ the destabilized gating process to some degree (Balser et al. 1996b; Fan et al. 1996). Therefore, the salutary effect of lowering [Na+]o on lidocaine action in Fig. 2 could be influenced by concurrent lidocaine effects on fast and slow inactivation gating.

We previously found that the W402A mutation reduced the rate of entry into the IM state during depolarization (Kambouris et al. 1998). However, the mutation did not shift the steady-state availability curve to depolarized potentials (Kambouris et al. 1998), contrary to the expectation for an inactivation-destabilizing intervention (and in contrast to raising [Na+]o in Fig. 1D). It is important to note that Fig. 1D assesses the equilibrium between inactivated states and closed states during modest (sub-threshold) depolarization, but does not consider inactivated-state stability at more depolarized membrane potentials sufficient to open the channel. Figure 1B and prior data (Kambouris et al. 1998) indicate that either raising [Na+]o or the W402A mutation decrease the rate of entry into IM at depolarized membrane potentials sufficiently to activate channels. W402A antagonizes the effects of reducing [Na+]o on both IM and use-dependent development of lidocaine block (Fig. 3), suggesting these two interventions share common mechanisms at depolarized membrane potentials. At hyperpolarized potentials, in Xenopus oocytes with the β1 subunit coexpressed, the W402A mutation seemed to have little effect on the time constants for recovery from slow inactivation, consistent with the absent shift in steady-state availability (Kambouris et al. 1998). Conversely, raising [Na+]o increases the rate of recovery from slow inactivation at hyperpolarized voltages (Townsend & Horn, 1997), and our data (Fig. 1D) show that Nao+ shifts the steady-state availability curve at ‘subthreshold’ voltages in a positive direction. Both findings suggest IM is ‘destabilized’ by Nao+ at negative voltages, and Fig. 1E shows that the rate of recovery from use-dependent lidocaine ‘block’ at −100 mV is also hastened when [Na+]o is raised.

The evidence that mutating residues accessible to the pore modifies slow inactivation (Balser et al. 1996a; Todt et al. 1999) suggests a relationship between the Na+ permeation pathway and the IM gating mechanism. An analogous ‘slow’ inactivation process in K+ channels (so-called ‘C-type’ inactivation) involves conformational rearrangements in the outer pore, and is inhibited by raising the extracellular concentration of K+ (Lopez-Barneo et al. 1993; Liu et al. 1996). Moreover, use-dependent ‘block’ of Shaker channels by intracellular pore blockers involves induced C-type inactivation (Baukrowitz & Yellen, 1996). Hence, our results may suggest some general similarities between use-dependent drug action in Na+ channels and K+ channels. We caution, however, that these findings should not be generalized to suggest occupancy of IM fully explains the use-dependent current suppression by all local anaesthetics. In contrast to lidocaine, which exhibits a preference for inactivated channels, high-affinity binding to the open channel may play a greater role in use-dependent block by disopyramide (Barber et al. 1992) as well as quinidine and flecainide (Ragsdale et al. 1996). Hence, future studies will determine the relative role of the IM state in the action of other Na+ channel blocking compounds with diverse use-dependent kinetic properties.

Our findings support a model for use-dependent lidocaine block where drug binding induces the channel to enter an intrinsic inactivated state (IM) with high lidocaine affinity. The available evidence suggests that lidocaine binds to a site in the aqueous pore, on the cytoplasmic side but very near to the putative selectivity filter (Ragsdale et al. 1994, 1996; Sunami et al. 1997). Site-directed mutations suggest that the IM state also involves conformational changes in the pore, but slightly external to the selectivity filter (Balser et al. 1996a; Kambouris et al. 1998; Benitah et al. 1999). The emerging recognition that Na+ channel pore segments are exceptionally mobile (Benitah et al. 1997; Tsushima et al. 1997) could abridge these intramolecular distances.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Drs Lou DeFelice and Christoph Fahlke for their critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM56307 to J.R.B., HL52668 to E.M. and R01 HL50411 to G.F.T.).

References

- Adelman WJ, Palti Y. The effects of external potassium and long duration voltage conditioning on the amplitude of sodium currents in the giant axon of the squid, Loligo pealei. Journal of General Physiology. 1969;54:589–606. doi: 10.1085/jgp.54.5.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balser JR, Nuss HB, Chiamvimonvat N, Perez-Garcia MT, Marbán E, Tomaselli GF. External pore residue mediates slow inactivation in μ1 rat skeletal muscle sodium channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1996a;494:431–442. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balser JR, Nuss HB, Orias DW, Johns DC, Marbán E, Tomaselli GF, Lawrence JH. Local anesthetics as effectors of allosteric gating: lidocaine effects on inactivation-deficient rat skeletal muscle Na channels. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996b;98:2874–2886. doi: 10.1172/JCI119116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balser JR, Nuss HB, Romashko DN, Marbán E, Tomaselli GF. Functional consequences of lidocaine binding to slow-inactivated sodium channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1996c;107:643–658. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balser JR, Roden DM, Bennett PB. Global parameter optimization for cardiac potassium channel gating models. Biophysical Journal. 1990;57:433–444. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82560-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber MJ, Wendt DJ, Starmer CF, Grant AO. Blockade of cardiac sodium channels: competition between the permeant ion and antiarrhythmic drugs. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1992;90:368–381. doi: 10.1172/JCI115871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Yellen G. Use-dependent blockers and exit rate of the last ion from the multi-ion pore of a K channel. Science. 1996;271:653–656. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP, Cohen CJ, Tsien RW. Lidocaine block of cardiac sodium channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1983;81:613–642. doi: 10.1085/jgp.81.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitah JP, Chen Z, Balser J, Tomaselli GF, Marbán E. Molecular dynamics of the sodium channel pore vary with gating: interactions between P-segment motions and inactivation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:1577–1585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01577.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitah JP, Ranjan R, Yamagishi T, Janecki M, Tomaselli GF, Marbán E. Molecular motions within the pore of voltage-dependent sodium channels. Biophysical Journal. 1997;73:603–613. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78096-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett PB, Valenzuela C, Li-Qiong C, Kallen RG. On the molecular nature of the lidocaine receptor of cardiac Na+ channels. Circulation Research. 1995;77:584–592. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.3.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan MD. Local anesthetic block of sodium channels in normal and pronase-treated squid axons. Biophysical Journal. 1978;23:285–311. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85449-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan MD, Almers W. Interactions between quaternary lidocaine, the sodium channel gates, and tetrodotoxin. Biophysical Journal. 1979;27:39–56. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85201-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SC, McClatchey AI, Gusella JF. Modification of the Na+ current conducted by the rat skeletal muscle α subunit by coexpression with a human brain β subunit. Pflügers Archiv. 1993;423:155–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00374974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler WK, Meves H. Slow changes in membrane permeability and long lasting action potentials in axons perfused with fluoride solutions. The Journal of Physiology. 1970;211:707–728. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SY, Satin J, Fozzard HA. Modal behavior of the μ1 Na+ channel and effects of coexpression of the β1 subunit. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:2581–2592. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79829-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney KR. Mechanism of frequency-dependent inhibition of sodium currents in the frog myelinated nerve by the lidocaine derivative gea 968. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1975;195:225–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR, Sigworth FJ. Impaired slow inactivation in mutant sodium channels. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:227–236. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, George AL, Kyle JW, Makielski JC. Two human paramyotonia congenita mutations have opposite effects on lidocaine block of Na+ channels expressed in a mammalian cell line. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:275–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone DE, Richmond JE, Ruben PC. Interaction between fast and slow inactivation in Skm1 sodium channels. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:3098–3109. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79504-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filatov GN, Nguyen TP, Kraner SD, Barchi RL. Inactivation and secondary structure in the D4/S4–5 region of the Skm1 sodium channel. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:703–715. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.6.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AO, Dietz MA, Gilliam FR, III, Starmer CF. Blockade of cardiac sodium channels by lidocaine: single-channel analysis. Circulation Research. 1989;65:1247–1262. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LJ, Brown RH, Cannon SC. Inactivation defects caused by myotonia-associated mutations in the sodium channel III-IV linker. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;107:559–576. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LJ, Brown RH, Cannon SC. Slow inactivation differs among mutant Na channels associated with myotonia and periodic paralysis. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:1204–1219. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78768-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann SH, Terlau H, Stühmer W, Imoto K, Numa S. Calcium channel characteristics conferred on the sodium channel by single mutations. Nature. 1992;356:441–443. doi: 10.1038/356441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Local anesthetics: hydrophilic and hydrophobic pathways for the drug-receptor reaction. Journal of General Physiology. 1977;69:497–515. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindmarsh AC. Odepack, a systematized collection of ode solvers. In: Stepleman RS, editor. Scientific Computing. Amsterdam: North-Holland Company; 1983. pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. The Journal of Physiology. 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem LM, Katzung BG. Time- and voltage-dependent interactions of the antiarrhythmic drugs with cardiac sodium channels. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1977;472:373–398. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(77)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns DC, Nuss HB, Marbán E. Suppression of neuronal and cardiac transient outward currents by viral gene transfer of dominant negative KV4.2 constructs. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:31598–31603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambouris NG, Hastings L, Stepanovic S, Marbán E, Tomaselli GF, Balser JR. Mechanistic link between lidocaine block and inactivation probed by outer pore mutations in the rat μ1 skeletal channel sodium channel. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;512:693–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.693bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodorov B, Shishkova L, Peganov E, Revenko S. Inhibition of sodium currents in frog Ranvier node treated with local anesthetics: role of slow sodium inactivation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1976;433:409–435. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JH, Orias DW, Balser JR, Nuss HB, Tomaselli GF, Marbán E. Single-channel analysis of inactivation-defective rat skeletal muscle sodium channels containing the F1304Q mutation. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerche H, Peter W, Fleischhauer R, Pika-Hartlaub U, Malina T, Mitrovic N, Lehmann-Horn F. Role in fast inactivation of the IV/S4-S5 loop of the human muscle Na+ channel probed by cysteine mutagenesis. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;505:345–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.345bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Jurman ME, Yellen G. Dynamic rearrangement of the outer mouth of a K channel during gating. Neuron. 1996;16:859–867. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Barneo J, Hoshi T, Heinemann SH, Aldrich RW. Effects of external cations and mutations in the pore region on C-type inactivation of Shaker potassium channels. Receptors and Channels. 1993;1:61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee JC, Ragsdale DS, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. A mutation in segment IVS6 disrupts fast inactivation of sodium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:12346–12350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee JC, Ragsdale DS, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. A critical role for transmembrane segment IVS6 of the sodium channel α subunit in fast inactivation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:12025–12034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee JC, Ragsdale DS, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. A critical role for the intracellular loop in domain IV of the sodium channel α subunit in fast inactivation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:1121–1129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makielski JC, Limberis JT, Chang SY, Fan Z, Kyle JW. Coexpression of β1 with cardiac sodium channel α subunits in oocytes decreases lidocaine block. Molecular Pharmacology. 1996;49:30–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux J-P. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelder JA, Mead R. A simplex method for function minimization. Computer Journal. 1965;7:308–313. [Google Scholar]

- Nuss HB, Balser JR, Orias DW, Lawrence JH, Tomaselli GF, Marbán E. Coupling between fast and slow inactivation revealed by analysis of a point mutation (F1304Q) in μ1 rat skeletal muscle sodium channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:411–429. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss HB, Kambouris NG, Marbán E, Tomaselli GF, Balser JR. Isoform-specific lidocaine block of sodium channels explained by differences in gating. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:200–210. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76585-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss HB, Tomaselli GF, Marbán E. Cardiac sodium channels (hH1) are intrinsically more sensitive to tonic block by lidocaine than are skeletal muscle (μ1) channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1995;106:1193–1210. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.6.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold LR. Automatic selection of methods for solving stiff and nonstiff systems of ordinary differential equations. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. Journal of Scientific Computing. 1983;4:136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale DS, McPhee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of state-dependent block of Na+ channels by local anesthetics. Science. 1994;265:1724–1728. doi: 10.1126/science.8085162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale DS, McPhee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Common molecular determinants of local anesthetic, antiarrhythmic, and anticonvulsant block of voltage-gated Na+ channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:9270–9275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JE, Featherstone DE, Hartmann HA, Ruben PC. Slow inactivation in human cardiac sodium channels. Biophysical Journal. 1998;74:2945–2952. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)78001-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy B. Slow inactivation of the sodium conductance in squid giant axons. Pronase resistance. The Journal of Physiology. 1978;238:1–21. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MR, Goldin AL. Interaction between the sodium channel inactivation linker and domain III S4-S5. Biophysical Journal. 1997;73:1885–1895. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78219-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stühmer W, Conti F, Suzuki H, Wang X, Noda M, Yahagi N, Kubo H, Numa S. Structural parts involved in activation and inactivation of the sodium channel. Nature. 1989;339:597–603. doi: 10.1038/339597a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunami A, Dudley SC, Jr, Fozzard HA. Sodium channel selectivity filter regulates antiarrhythmic drug binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:14126–14131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Chehab N, Wieland SJ, Kallen RG. Glutamine substitution at alanine1649 in the S4-S5 cytoplasmic loop of domain 4 removes the voltage sensitivity of fast inactivation in the human heart sodium channel. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:639–652. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.5.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todt H, Dudley SC, Jr, Kyle JW, French RJ, Fozzard HA. Ultra-slow inactivation in mu 1 Na+ channels is produced by a structural rearrangement of the outer vestibule. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:1335–1345. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77296-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, Chiamvimonvat N, Nuss HB, Balser JR, Perez-Garcia MT, Xu RH, Orias DW, Backx PH, Marbán E. A mutation in the pore of the sodium channel alters gating. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68:1814–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80358-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend C, Horn R. Effect of alkali metal cations on slow inactivation of cardiac Na channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:23–33. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimmer JS, Cooperman SS, Tomiko SA, Zhou J, Crean SM, Boyle MB, Kallen RG, Sheng Z, Barchi RL, Sigworth FJ, Goodman RH, Agnew WS, Mandel G. Primary structure and functional expression of a mammalian skeletal muscle sodium channel. Neuron. 1989;3:33–49. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsushima RG, Li RA, Backx PH. P-loop flexibility in Na+ channel pores revealed by single- and double-cysteine replacements. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:59–72. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukomadu C, Zhou J, Sigworth FJ, Agnew WS. μ1 Na+ channels expressed transiently in human embryonic kidney cells: biochemical and biophysical properties. Neuron. 1992;8:663–676. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90088-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedantham V, Cannon SC. The position of the fast-inactivation gate during lidocaine block of voltage-gated Na+ channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:7–16. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DW, Nie L, George AL, Bennett PB. Distinct local anesthetic affinities in Na+ channel subtypes. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:1700–1708. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79732-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner MP, Felts KA, Simcox TG, Brama JC. A method for the site-directed mono- and multi-mutagenesis of double stranded DNA. Gene. 1993;126:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90587-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J, Patton D, Scheuer T, Wang Y, Goldin AL, Catterall WA. A cluster of hydrophobic amino acid residues required for fast Na+-channel inactivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:10910–10914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh JZ. Sodium inactivation mechanism modulates qx-314 block of sodium channels. Biophysical Journal. 1978;24:569–574. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85403-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Potts JF, Trimmer JS, Agnew WS, Sigworth FJ. Multiple gating modes and the effect of modulating factors on the μ1 sodium channel. Neuron. 1991;7:775–785. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90280-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberter Y, Motin L, Sokolova S, Papin A, Khodorov B. Ca-sensitive slow inactivation and lidocaine-induced block of sodium channels in rat cardiac cells. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1991;23:61–72. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90025-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]