Abstract

A mutation in the G-protein-linked, inwardly rectifying K+ channel GIRK2 leads to the loss of cerebellar and dopaminergic mesencephalic neurons in weaver mice. The steps leading to cell death are not well understood but may involve constitutive influx of Na+ and Ca2+ into the neurons.

We found that resting [Ca2+]i was dramatically higher in cerebellar neurons from weaver mice compared to wild-type neurons.

High-K+ stimuli elicited much smaller changes in [Ca2+]i in weaver cerebellar neurons compared to wild-type neurons.

weaver cerebellar granule cells could be rescued from cell death by the GIRK2wv cationic channel blocker, QX-314.

QX-314 lowered resting intracellular Ca2+ levels in weaver cerebellar granule cells.

These results suggest that changes in resting [Ca2+]i levels and alterations in K+ channel function are most likely to contribute to the developmental abnormalities and increased cerebellar cell death observed in weaver mice.

In weaver (wv) mice, the substitution of a serine for a glycine (G156S) (Patil et al. 1995) alters the putative pore-forming H5 region (MacKinnon & Yellen, 1990) of the inwardly rectifying GIRK2 potassium channel and results in the loss of selectivity for K+ ions, allowing Na+ and Ca2+ ions to permeate into cells (Kofuji et al. 1996; Navarro et al. 1996; Silverman et al. 1996; Slesinger et al. 1996; Tong et al. 1996). The wv mutation results in cell death in the central nervous system and testes producing a range of neurological dysfunctions and infertility in the male (Vogelweid et al. 1993; Patil et al. 1995; Kofuji et al. 1996; Liao et al. 1996; Navarro et al. 1996; Silverman et al. 1996; Slesinger et al. 1996; Surmeier et al. 1996; Tong et al. 1996). In particular, the wv mutation affects two regions of the CNS. In cerebellum, granule cell neurons die soon after birth as they fail to differentiate and migrate into the internal granule cell layer (Goldowitz, 1989; Hess, 1996). Large numbers of granule cells are lost (Rakic & Sidman, 1973a,b; Sidman, 1976) as well as lesser numbers of Purkinje cells (Smeyne & Goldowitz, 1990) producing the prominent ataxia characteristic of these animals. In addition, there is a severe depletion of tyrosine hydroxylase positive neurons in the midbrain (substantia nigra, pars compacta) (Schmidt et al. 1982; Roffler-Tarlov & Graybiel, 1986; Triarhou et al. 1986). These anatomical changes coexist with an altered distribution of GIRK1 and GIRK2 K+ channel proteins throughout the brain (Liao et al. 1996).

Putative GIRK2wv channels have been expressed in Xenopus oocytes and in CHO cells (Patil et al. 1995; Kofuji et al. 1996; Liao et al. 1996; Navarro et al. 1996; Silverman et al. 1996; Surmeier et al. 1996; Tong et al. 1996; Slesinger et al. 1996, 1997; Lauritzen et al. 1997). GIRK1 subunits expressed by themselves do not form functional channels although it is believed that GIRK2 subunits can form functional homomeric channels (assuming there was no complementation by endogenous subunits in these experiments). Homomeric GIRK2wv channels expressed in oocytes produce a constitutively active non-selective inward current (Kofuji et al. 1996; Navarro et al. 1996; Silverman et al. 1996; Slesinger et al. 1996; Tong et al. 1996) suggesting that GIRK2wv channels lose their selectivity for K+ ions and their regulation by G-proteins. Native channels are believed to be comprised of both GIRK1 and GIRK2. Co-expression of wild-type GIRK1 and GIRK2 subunits produce large K+-selective currents that are G-protein regulated (Slesinger et al. 1996). Co-expression of GIRK1 and GIRK2wv results in much smaller currents that are non-selective (Kofuji et al. 1996; Navarro et al. 1996; Slesinger et al. 1996) and which may (Slesinger et al. 1996) or may not (Kofuji et al. 1996; Navarro et al. 1996) show some G-protein regulation.

In contrast to studies on expression systems, the causes leading to cell death in wv cerebellar neurons are still in dispute, but may be due to a constitutive Na+ or Ca2+ leak into neurons through GIRKwv channels (Kofuji et al. 1996; Silverman et al. 1996; Slesinger et al. 1997). In support of these conclusions, cerebellar neurons are rescued by blocking GIRK2wv channels with QX-314, MK-801, verapamil (Kofuji et al. 1996) or the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA AM (Liesi et al. 1997); GIRK2 knockout mice did not exhibit augmented neuronal cell death (Signorini et al. 1997). In contrast, Surmeier et al. (1996) proposed that cell death resulted from the loss of GIRK function. GIRK channels constitute an important inhibitory pathway in the CNS; loss of this pathway would lead to hyperexcitability and cell death. Greatly diminished GIRK currents in weaver animals have been reported by other labs as well (Lauritzen et al. 1997). Interestingly, granule cells were rescued when NR1 NMDA subunits were knocked out in weaver NR1 double mutants (Jensen et al. 1999). Thus, the exact cause of cell death remains unknown.

To help clarify the cause of cerebellar granule cell death, we focused our studies on whether alterations in resting [Ca2+]i levels or changes in [Ca2+]i levels in response to elevations of external K+ could be observed in wv/wv cerebellar granule cells. In addition, if a chronic leak through GIRK2wv channels initiates a cascade leading to death, then blockade of the channels should rescue the neurons. We found that (1) resting [Ca2+]i was dramatically elevated in wv/wv cerebellar granule cells relative to +/+ neurons, (2) high-K+ stimulation produced much smaller changes in [Ca2+]i in wv/wv neurons than in +/+ neurons, and (3) the cationic channel blocker, QX-314, rescued wv/wv neurons from cell death. Our results suggest that K+ permeability is altered in wv/wv animals and are most consistent with the hypothesis that a constitutive Ca2+ and Na+ leak through GIRKwv channels probably accounts for the cerebellar granule cell death observed in wv/wv animals.

METHODS

Animals

All experiments were conducted according to the ‘Principles of Laboratory Animal Care’ (NIH publication 86–23, revised 1985). The animals were obtained from a colony of mice housed at Indiana University School of Medicine. The wv mutation is maintained on a B6CBA-Awj/A hybrid stock. For timed pregnancies which are critical to procure the embryos of defined gestational age, wv/wv and +/+ females were mated with wv/+ and +/+ males, respectively. After 12 h, the males and females were separated and the day designated as embryonic day 1 (see Altman & Bayer, 1995 for details). Animals were assessed via the Champlin method for the stage of the oestrous cycle on the day of mating, and pregnancy was monitored by visual appraisal and palpation.

Cell culture

Pregnant mice were killed by cervical dislocation and their embryos were decapitated. The neuronal cultures were prepared from embryonic day 19 mice, a time in development which corresponds to the onset of an active period of apoptosis. Although our data may be contaminated by normal developmental apoptosis, we chose to use the cerebellar granule cells at this developmental stage in order to facilitate comparisons with the work of others who used young animals, typically postnatal days 4–7, in their wv/wv studies (Kofuji et al. 1996; Surmeier et al. 1996; Slesinger et al. 1997). Dissociated primary cerebellar neuronal cultures in serum-free medium were prepared from individual cerebella of wv mutant and wild-type animals using the bilaminar culture method described by Banker & Goslin (1988). These cultures comprised almost exclusively cerebellar granule cell precursor neurons, which are referred to as cerebellar granule cells throughout this paper. The neurons were plated onto polylysine-coated (15 μg ml−1) 25 mm glass coverslips which had three paraplast ‘feet’ affixed, incubated for 2–3 h at 37°C to allow the cells to attach, and inverted onto the astrocyte feeder (for details see Fox et al. 1998). All neurons were grown in the presence of QX-314 (100 μM) to promote cell survival.

[Ca2+]i measurements

Experiments were conducted 3–5 days after neurons were prepared. [Ca2+]i was measured with fura-2 and an imaging system. Data were acquired and analysed prior to any knowledge of genotype of the cells. An individual coverslip that contained neurons was removed from the glial feeder layer and placed into Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; see below) solution to load fura-2 (either 1, 1.5 or 2 μM fura-2 AM) for 45 min. The cells were washed in a fura-2-free solution for 1 h. Fura-2 loading and wash were carried out at 37°C in the absence of QX-314. The coverslip was transferred to an experimental chamber for recording. Background fluorescence at 340 nm and 380 nm was obtained using an area of the coverslip devoid of cells. Data were continuously collected throughout the experiment. On each coverslip, 10–20 small, round granule neurons were selected and individually imaged. Image pairs (one at 340 nm and 380 nm) were obtained every 10 s by averaging 16 frames at each wavelength. Background fluorescence was subtracted from the individual wavelengths, and the 340 nm image was divided by the 380 nm image to provide a ratiometric image. Ratios were converted to free [Ca2+]i by comparing data to fura-2 calibration curves made in vitro by adding fura-2 (50 μM free acid) to solutions that contained known concentrations of calcium (0 nM to 2000 nM). The liver from each embryo was genotyped after the imaging data analysis was complete (for details, see Fox et al. 1998). The data were grouped as either +/+ or wv/wv and Student's t test was performed.

Neuronal survival

Cerebellar granule neurons from individual wv mutant and +/+ embryos were plated onto 15 mm coverslips and maintained in culture for 72 h in the presence or absence of QX-314 (100 μM). Neurons on the coverslips were visualized immunocytochemically for NeuN, a neuronal nuclear protein. Neuronal survival was estimated by placing a template with four circles (comprising ∼3.3 % of total coverslip area) over each coverslip and counting the NeuN labelled cells within the circles. Cells touching the inner edge of the circles were not counted.

Solutions

Experiments were carried out in HBSS (Gibco) which contained (mM): 138 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 0.3 KH2PO4, 0.8 MgSO4, 0.3 Na2HPO4, 5.6 D-glucose and 20 Hepes. The 50 mM K+ solution contained (mM): 50 KCl, 87 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 CaCl2, 10 D-glucose and 12 Hepes. The 20 mM K+ solution was identical to the 50 mM K+ solution with the exception of 20 mM KCl and 115 mM NaCl.

RESULTS

Intracellular calcium measurements

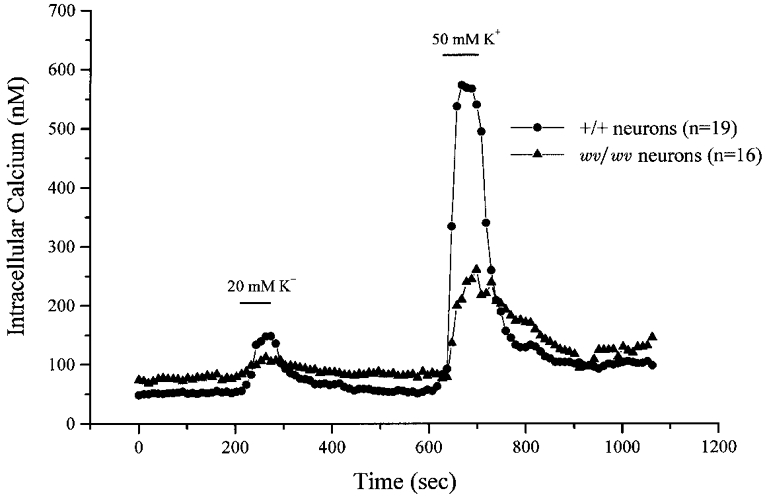

The cerebellar granule cell cultures were prepared from E19 mice, and after 3–5 days in primary culture, a coverslip that contained either wv/wv or +/+ cerebellar granule neurons was transferred to an experimental chamber for each experiment. The microscope was adjusted until a field of view was obtained that had dozens of cerebellar granule neurons visible. [Ca2+]i measurements from 10–20 neurons per coverslip was collected every 10 s. Figure 1 shows representative data from two different experiments; the averages and statistics are described in more detail in Figs 2 and 3. In Fig. 1, data from 19 +/+ cerebellar granule neurons are averaged and plotted (circles), and in the other experiment, data from 16 wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons are averaged and plotted (triangles). Approximately the first 200 s of each experiment represents resting [Ca2+]i levels. Figure 1 shows that resting [Ca2+]i was elevated in wv/wv neurons compared to +/+ neurons. Figure 1 also shows representative responses to high-K+ stimulation in wv/wv and +/+ cerebellar granule neurons. The high-K+ solution depolarized the cerebellar granule cells and activated voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels to produce a change in [Ca2+]i. Responses to both 20 and 50 mM high-K+ solutions are plotted. +/+ neurons responded to the 20 mM K+ stimulation, whereas wv/wv responses were small. Although both the wv/wv and +/+ neurons exhibited increases in [Ca2+]i when 50 mM K+ solution was applied, the response was much larger in the +/+ neurons than the wv/wv neurons. There was considerable variation in the response of individual neurons to high-K+ stimulation.

Figure 1. A representative experiment shows that resting [Ca2+]i is elevated in the wv/wv cerebellar neurons, and that high-K+ stimulations elicited larger increases in [Ca2+]i in +/+ cerebellar neurons than in wv/wv cerebellar neurons.

A field of individual neurons was imaged and the ratio of fluorescence at 340 nm to that at 380 nm was collected once every 10 s. The ratio was averaged for each time point for the field of neurons and plotted as circles for the +/+ neurons (n = 19) and as triangles for the wv/wv neurons (n = 16). Depolarizing stimulations of either 20 or 50 mM K+ were applied for 1 min as indicated above the plots (bar).

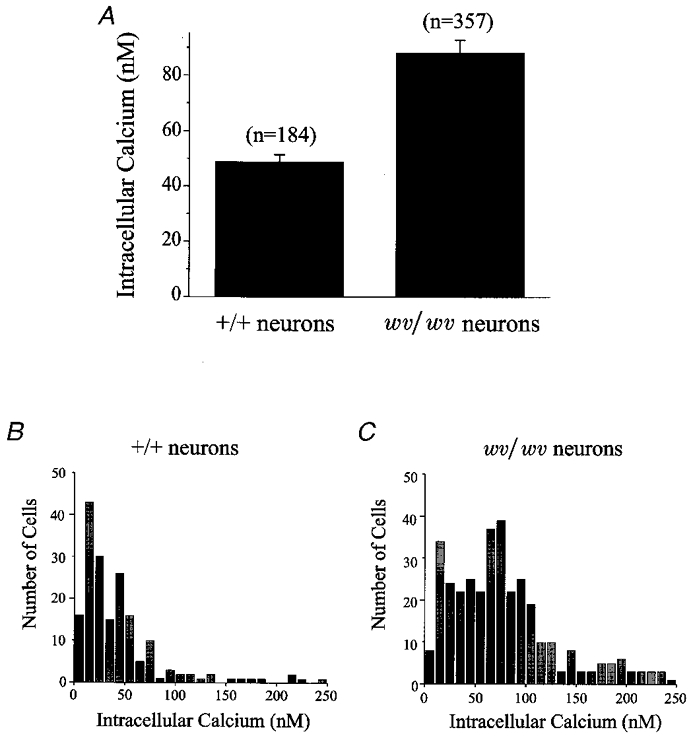

Figure 2. Resting [Ca2+]i was elevated in wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons compared with +/+ granule neurons.

[Ca2+]i was measured with the AM ester of fura-2 and compared with an in vitro saline solution of known calcium concentrations. A, average resting [Ca2+]i in either +/+ or wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons. Resting [Ca2+]i in +/+ cerebellar neurons was 48.9 ± 4.0 nM (n = 184; mean ±s.e.m.) and in wv/wv cerebellar neurons was 88.2 ± 4 nM (n = 357; P < 0.001). B and C, histograms constructed by binning all resting [Ca2+]i measurements of the +/+ neurons (B) or wv/wv neurons (C). All neurons that had a resting [Ca2+]i over 250 nM were eliminated from analysis.

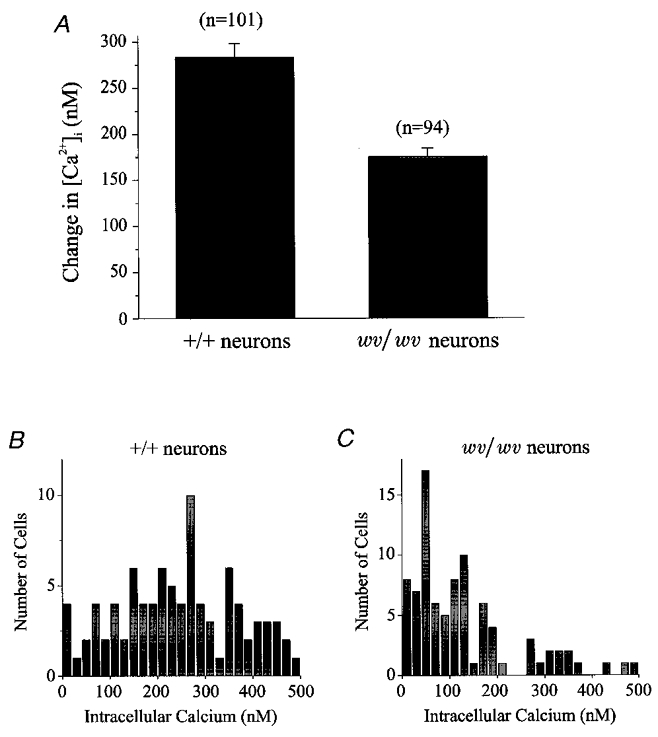

Figure 3. Exposure to 50 mM K+ elicited a larger change in [Ca2+]i in +/+ cerebellar neurons than in wv/wv cerebellar neurons.

A, average change of [Ca2+]i in response to 1 min application of 50 mM K+. +/+ cerebellar neurons responded with a 284.3 ± 17.6 nM (n = 101) change in [Ca2+]i while the wv/wv cerebellar neurons responded with a 175.7 ± 22.0 nM (n = 94; P < 0.001) change in [Ca2+]i. B and C, histograms constructed by binning all of the changes in [Ca2+]i from +/+ neurons (B) and wv/wv neurons (C) in response to 50 mM K+ stimulation. Neurons with an increase of [Ca2+]i greater than 500 nM were eliminated from analysis.

Resting calcium is elevated in wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons

Figure 2A plots the average resting [Ca2+]i levels observed in the wv/wv and +/+ cerebellar granule cells. Resting [Ca2+]i was significantly higher in the wv/wv neurons, 88.2 ± 4 nM (mean ±s.e.m., n = 357; P < 0.001) compared to +/+ neurons, 48.9 ± 4.0 nM (n = 184). Figure 2B and C shows histograms constructed by binning the resting [Ca2+]i data from +/+ and wv/wv neurons, respectively. Interestingly, there is significant overlap between the two data sets. Some of the +/+ cerebellar granule cells had elevated resting [Ca2+]i levels, while many of the wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons had low resting [Ca2+]i levels. In general, the resting [Ca2+]i levels were almost twice as high in wv/wv compared to +/+ cerebellar granule cells.

High K+ stimulation evokes less change in [Ca2+]i in wv/wv than +/+ cerebellar granule neurons

Figure 3 provides a detailed analysis of +/+ and wv/wv cerebellar granule cell responses to 50 mM K+ stimulation. In +/+ neurons, the average change in [Ca2+]i (Δ[Ca2+]i) elicited by 50 mM K+ was 284.3 ± 17.6 nM (n = 101). In contrast, the wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons responded to 50 mM K+ stimulation with a significantly smaller Δ[Ca2+]i of 175.7 ± 22.0 nM (n = 94; P < 0.001). Figure 3B and C shows histograms where the responses of individual neurons to 50 mM K+ are plotted. Although some +/+ and wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons showed little or relatively small changes to 50 mM K+ stimulation, more +/+ neurons (77 of 90) responded to the 50 mM K+ with a Δ[Ca2+]i greater than 100 nM compared to the wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons (44 of 87).

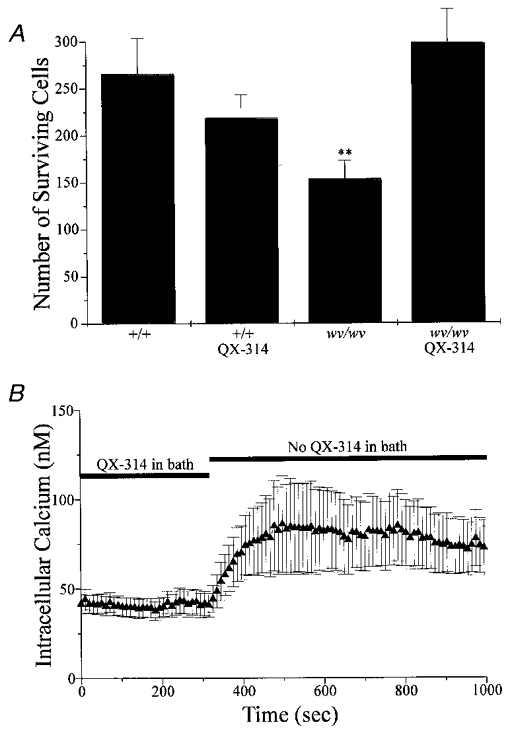

wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons are rescued from death by QX-314

Figure 4A shows that wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons are rescued from cell death by the cation channel blocker QX-314. In these experiments, primary cerebellar granule neuronal cultures were prepared from individual cerebella of embryonic day 19 mice, plated onto coverslips and grown in culture for 72 h either in the presence or absence of QX-314 (100 μM). Neurons were visualized immunocytochemically with NeuN, a neuronal nuclear protein, and counted. Figure 4 shows the number of cerebellar granule cells that survived for each genotype group, +/+ (n = 4 embryos) and wv/wv (n = 13 embryos). QX-314 did not affect the survival of +/+ cerebellar granule cells, but QX-314 did increase wv/wv survival. The survival of the wv/wv cerebellar granule cells in the presence of QX-314 (298 ± 36) was not different than that of +/+ neurons (266 ± 38) in the absence of QX-314. wv/wv cerebellar granule cell death was significantly greater in the absence of QX-314 (154 ± 20; P < 0.01).

Figure 4. wv/wv neurons are rescued from cell death by the cation channel blocker QX-314 (100 μM).

QX-314 alters intracellular calcium in these neurons. A, number of neurons that survived for each group. There was no significant difference in survival of +/+ cells grown in the absence or the presence of QX-314. In contrast, the number of wv/wv neurons that survived in the presence of QX-314 was almost twice the number of neurons that survived in the absence of QX-314 (P < 0.01). B, a field of 13 individual wv/wv neurons was imaged and intracellular calcium was measured. QX-314 was in the bath at the beginning of the experiment and then washed out as indicated. For this experiment alone, cells were continuously in the presence of QX-314 (in the culture dishes, during fura-2 loading and wash), until it was removed from the bath as indicated.

Figure 4B plots representative data from an experiment where [Ca2+]i data from 13 wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons were averaged and plotted (triangles) in the absence or presence of QX-314 (100 μM); resting [Ca2+]i was significantly lower in the presence of QX-314. The ability of QX-314 to lower [Ca2+]i may play a role in its capacity to rescue neurons. In total 29 cells showed responses similar to those shown in Fig. 4B.

DISCUSSION

We focused our studies on whether alterations in resting [Ca2+]i levels could be observed in wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons. In this study we show that unstimulated cultured embryonic cerebellar granule neurons from wv/wv mice exhibit dramatically elevated resting [Ca2+]i levels, which suggests that basal Ca2+ influx is elevated. High-K+ stimulation produced much smaller changes in [Ca2+]i in wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons than in +/+ cerebellar granule neurons indicating that K+ conductance is altered. Furthermore, if a chronic leak of Ca2+ through GIRK2wv channels initiates a cell-death cascade, then blockade of the channels should rescue the cerebellar granule neurons. Cerebellar granule cells were rescued from cell death when they were incubated in media containing the cationic channel blocker QX-314, in agreement with a report by Kofuji et al. (1996). Furthermore, QX-314 reversed the [Ca2+]i elevation observed in wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that a chronic leak through GIRKwv channels may account for the neuronal death observed in wv/wv animals, and that QX-314 rescues the neurons, in part, by lowering [Ca2+]i.

Developmental abnormalities have been observed in cerebellum of weaver heterozygote animals (wv/+ (Rakic & Sidman, 1973a; Smeyne & Goldowitz, 1989) even in embryos (Bayer et al. 1996). Increased cell death has been observed in cerebellar neurons of the wv/+ animals (Willinger & Margolis, 1985; Wullner et al. 1995) as well as in dopaminergic neurons of the mesencephalon (Verina et al. 1997; Won et al. 1997) but much less than that found in wv/wv animals. In part, the diminished cell death observed in wv/+ animals relative to wv/wv may be due to a gene dosage effect; the heterozygous cells presumably express less GIRK2wv (Hess, 1996). In our earlier studies we showed that resting [Ca2+]i was significantly elevated in wv/+ cerebellar granule cells relative to +/+ (Fox et al. 1998). Nonetheless, the change in resting Ca2+ reported in our earlier study was much smaller than that reported in this manuscript for wv/wv neurons (there was a 10.8 nM increase in resting Ca2+ in wv/+ neurons compared to +/+, which corresponds to ∼20 % change, versus a 39.3 nM increase in resting Ca2+ in wv/wv neurons compared to +/+, which corresponds to ∼80 % change). These results are consistent with the dramatic increase in neuronal cell death observed in wv/wv animals when compared to wv/+ mice. A recent study by Womack et al. (1998) came to a somewhat different conclusion; they showed a comparable elevation in resting Ca2+ in both wv/wv and wv/+ mice. Womack et al. (1998) used neurons from older animals (postnatal days 4-5) in their study; some of the most severely affected neurons may have already died while the surviving neurons may have had a somewhat lowered resting Ca2+. Interestingly, our earlier study in wv/+ animals also found significantly diminished responses to high-K+ stimuli; our study showed that neither intracellular Ca2+ stores nor plasma membrane Ca2+ channels were affected by the wv mutation, suggesting that the diminished responses to high-K+ stimulation were due to the defect in GIRK2wv producing less of a depolarization (Fox et al. 1998).

There are five known members of the GIRK family of K+ channels (GIRK1-GIRK5), coupled to a variety of G-protein linked receptors, that are believed to play a critical role in establishing the resting potential of neurons and cardiac cells as well as determining the threshold for excitability (Andrade et al. 1986; North et al. 1987; Williams et al. 1988; Perkel et al. 1990; Brown et al. 1993; Penington et al. 1993a,b; Kovoor et al. 1995). GIRK1 and GIRK2 are broadly expressed, while GIRK3 appears exclusively expressed in brain (Hess, 1996). There is considerable overlap in the distribution of the three brain isoforms (GIRK1-GIRK3) (Lesage et al. 1994; Kobayashi et al. 1995; Kofuji et al. 1995; Patil et al. 1995; Chan et al. 1996; Karschin et al. 1996; Kofuji et al. 1996; Ponce et al. 1996). High levels of GIRK expression are found in the olfactory bulb, hippocampus, cortex, thalamus and cerebellum (Karschin et al. 1996). Identification of the mutation in the GIRK2wv channel as the causative agent leading to cell death in specific neuronal populations within the substantia nigra and cerebellum has underscored the important role these channels play in normal CNS functions across a broad range of systems (Kofuji et al. 1996; Liao et al. 1996; Navarro et al. 1996; Slesinger et al. 1996; Tong et al. 1996; Won et al. 1997). Although the exact mechanism by which the defect in GIRK2wv leads to death is still unknown, several possible explanations have been proposed.

One explanation for the cell death observed suggests that the defect leads to a constitutive Na+ or Ca2+ influx through native GIRKwv channels (Kofuji et al. 1996; Silverman et al. 1996) much like the constitutively active, non-selective inward current of GIRK2wv channels expressed in oocytes (Kofuji et al. 1996; Navarro et al. 1996; Silverman et al. 1996; Slesinger et al. 1996; Tong et al. 1996). A large non-selective membrane conductance was observed in dopaminergic midbrain from wv/wv but not +/+ mice; these neurons exhibited a depolarized membrane potential and a complete loss of spontaneous pacemaker activity (Liss et al. 1999). Elevation of [Ca2+]i as a mediator of cell death is particularly appealing as Ca2+ is a well-known trigger of neuronal cell death (Tymianski et al. 1994; Choi, 1995) including apoptotic cell death (Ui-Tei et al. 1996; Guo et al. 1997; Nicotera & Orrenius, 1998). In this paper, we show that resting [Ca2+]i is, in fact, elevated as predicted by this model. If GIRK2 channels help set the resting potential, then the model also predicts that responses to elevated K+ solutions may be diminished as GIRK2wv channel selectivity for K+ is altered. Our results of cerebellar granule cell survival are in agreement with those of Kofuji et al. (1996) and demonstrate that wv cerebellar granule neurons can be rescued with a cationic channel blocker such as QX-314 which is consistent with this model for cell death (Kofuji et al. 1996; Silverman et al. 1996). Previous work has shown that wv/wv cerebellar neurons could be rescued by MK-801, verapamil or the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA AM (Kofuji et al. 1996; Liesi et al. 1997); however, these agents all have other cellular effects that may complicate the interpretation. Our data are most consistent with the hypothesis that a constitutive Ca2+ and Na+ leak into wv/wv neurons initiates cell death. Nonetheless, it must be kept in mind that, to promote cell survival, cerebellar granule cells are cultured in media containing elevated K+ levels; these high-K+ media elevate [Ca2+]i to levels that are comparable to resting levels in wv/wv neurons (see Fig. 1). Thus, it seems unlikely that by itself elevated [Ca2+]i initiates cell death in cerebellar granule cells.

A second possible mechanism leading to neuronal death in the wv mouse may involve compromised metabolic function due to the energy required to pump Na+ out of cells to overcome the constitutive leak (Silverman et al. 1996). Increased Na+ influx via GIRK2wv channels may result from a regenerative link between Na+-influx and channel activation (Silverman et al. 1996). These conditions may also elevate resting [Ca2+]i and diminish responses to high-K+ solutions.

In contrast, a third mechanism has been proposed in which cerebellar granule cell death results from the loss of GIRK channel function (Surmeier et al. 1996). In this model, reducing a major inhibitory pathway in the CNS results in hyperexcitability of the cells which leads to cell death (Surmeier et al. 1996). In support of this hypothesis, GIRK currents in wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons are greatly diminished (Slesinger et al. 1996; Lauritzen et al. 1997), and GIRK1/GIRK2 expression levels are dramatically decreased in wv animals (Liao et al. 1996). Our data are consistent with the loss-of-function model only if cerebellar granule neurons become sufficiently depolarized to elevate resting [Ca2+]i and if QX-314 could inhibit this depolarization.

Interestingly, the net effect of these different cell death models may be similar. If GIRK2wv channels are constitutively active and leak Na+ or Ca2+ ions (Kofuji et al. 1996; Silverman et al. 1996) they will depolarize granule neurons. If the channels are non-functional, as suggested by the loss-of-function data (Liao et al. 1996; Slesinger et al. 1996; Surmeier et al. 1996; Lauritzen et al. 1997), cerebellar granule cells may be chronically depolarized as these channels help set the resting potential and make cells less excitable after activation. In all cases, prolonged depolarization of the neurons would lead to elevation of [Ca2+]i. In addition, cell death may require functional NMDA receptors as cerebellar granule cells were rescued in weaver NR1 double mutant animals.

Our [Ca2+]i data and the rescue of neurons by QX-314 suggest that mutant GIRK2wv channels underlie the differences observed between +/+ and wv/wv cerebellar granule cell survival. The large difference in resting [Ca2+]i may indicate the presence of a constitutive influx of Ca2+ in the wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons. The importance of elevated resting [Ca2+]i observed is unclear, although prolonged elevation of [Ca2+]i may initiate a cell death cascade (Ui-Tei et al. 1996; Guo et al. 1997; Nicotera & Orrenius, 1998). Studies in raphé neurons indicate that native GIRK channels are active at the resting potential (Penington et al. 1993a,b), even without stimulation of G-protein coupled receptors. Although it is not known whether the molecular composition of GIRK2-containing channels in cerebellum are similar to GIRK channels in raphé neurons or whether the channels are regulated in a similar manner, the results from raphé neurons suggest the possibility of constitutive activity in granule cells. The observation that depolarizing stimulations with 50 mM K+ caused a change in [Ca2+]i in both +/+ and wv/wv neurons implies that there is a K+ conductance active at rest. Even if voltage-activated K+ channels are activated by stimulation, they would only be activated after an initial depolarization by the ‘resting’ K+ conductance which could be due to K+-selective ‘leak’ channels or GIRK channels. If the initial depolarization was due to a ‘leak’ channel, no differences would be expected in wv/wv cerebellar granule neurons compared to +/+ neurons. The observation that high-K+ stimulation produced smaller changes in [Ca2+]i in wv/wv than in +/+ cerebellar granule neurons implies that GIRK2wv channels are active at or near the resting potential in these neurons. Thus, it is likely that the loss of K+ selectivity in GIRK2wv channels plays a role in the cerebellar neuronal death of the wv mutant phenotype.

The elevation of [Ca2+]i that we have observed suggests that both GIRK2wv as well as another K+ conductance are active at rest. An iso-osmotic replacement of Na+ with K+ should produce little or no depolarization of the neurons if non-selective wv/wv channels are active at rest. It is interesting to note that GIRK2 expression levels are quite high in different regions of the brain, including the hippocampus and olfactory bulb (Lesage et al. 1994; Patil et al. 1995; Kobayashi et al. 1995; Kofuji et al. 1995, 1996; Chan et al. 1996; Hess, 1996; Karschin et al. 1996; Ponce et al. 1996), but that the loss of neurons is only evident in the cerebellum (Rakic & Sidman, 1973a,b; Sidman, 1976) and dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra (Triarhou et al. 1988). A comparison of the differences in resting [Ca2+]i levels and the responses to high-K+ stimulation between the different neurons in the CNS may reveal how GIRK2wv affects cell survival.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Deborah Lucas, Carmen Stauss and Yue Feng for technical assistance, and Eric Gruenstein for the imaging software. This research was supported by grants NS-14426, NS-27613, and MH-28942.

References

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Atlas of Prenatal Rat Brain Development. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade R, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. A G protein couples serotonin and GABAB receptors to the same channels in hippocampus. Science. 1986;234:1261–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.2430334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker G, Goslin K. Developments in neuronal cell culture. Nature. 1988;336:185–186. doi: 10.1038/336185a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA, Wills KV, Wei J, Feng Y, Dlouhy SR, Hodes ME, Verina T, Ghetti B. Phenotypic effects of the weaver gene are evident in the embryonic cerebellum but not in the ventral midbrain. Brain Research Developmental Brain Research. 1996;96:130–137. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, Kim KM, Nakajima Y, Nakajima S. The role of G protein in muscarinic depolarization near resting potential in cultured hippocampal neurons. Brain Research. 1993;612:200–209. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91661-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KW, Langan MN, Sui JL, Kozak JA, Pabon A, Ladias JAA, Logothetis DE. A recombinant inwardly rectifying potassium channel coupled to GTP-binding proteins. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;107:381–397. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.3.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Calcium: still center-stage in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Trends in Neurosciences. 1995;18:58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AP, Dlouhy S, Ghetti B, Hurley JH, Nucifora PG, Nelson DJ, Won L, Heller A. Altered responses to potassium in cerebellar neurons from weaver heterozygote mice. Experimental Brain Research. 1998;123:298–306. doi: 10.1007/s002210050572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldowitz D. The weaver granuloprival phenotype is due to intrinsic action of the mutant locus in granule cells: Evidence from homozygous weaver chimeras. Neuron. 1989;2:1565–1575. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Sopher BL, Furukawa K, Pham DG, Robinson N, Martin GM, Mattson MP. Alzheimer's presenilin mutation sensitizes neural cells to apoptosis induced by trophic factor withdrawal and amyloid beta-peptide: involvement of calcium and oxyradicals. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:4212–4222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04212.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess EJ. Identification of the weaver mouse mutation: The end of the beginning. Neuron. 1996;16:1073–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Surmeier DJ, Goldowitz D. Rescue of cerebellar granule cells from death in weaver NR1 double mutants. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:7991–7998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07991.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karschin C, Dissmann E, Stuehmer W, Karschin A. IRK(1–3) and GIRK(1–4) inwardly rectifying K+ channel mRNAs are differentially expressed in the adult rat brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:3559–3570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-11-03559.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Ikeda K, Ichikawa T, Abe S, Togashi S, Kumanishi Y. Molecular cloning of a mouse G-protein-activated K+ channel (mGIRK1) and distinct distributions of three GIRK (GIRK1, 2 and 3) mRNAs in mouse brain. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1995;208:1166–1173. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofuji P, Davidson N, Lester HA. Evidence that neuronal G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels are activated by Gβγ subunits and function as heteromultimers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:6542–6546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofuji P, Hofer M, Millen KJ, Millonig JH, Davidson N, Lester HA, Hatten ME. Functional analysis of the weaver mutant GIRK2 K+ channel and rescue of weaver granule cells. Neuron. 1996;16:941–952. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovoor A, Henry DJ, Chavkin C. Agonist-induced desensitization of the mu opioid receptor-coupled potassium channel (GIRK1) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:589–595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen I, De Weille J, Adelbrecht C, Lesage F, Murer G, Raisman-Vozari R, Lazdunski M. Comparative expression of the inward rectifier K+ channel GIRK2 in the cerebellum of normal and weaver mutant mice. Brain Research. 1997;753:8–17. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage F, Duprat F, Fink M, Guillemare E, Coppola T, Lazdunski M, Hugnot J-P. Cloning provides evidence for a family of inward rectifier and G-protein coupled K+ channels in the brain. FEBS Letters. 1994;353:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao YJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Heteromultimerization of G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel proteins GIRK1 and GIRK2 and their altered expression in weaver brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:7137–7150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07137.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesi P, Wright JM, Krauthamer V. BAPTA-AM and ethanol protect cerebellar granule neurons from the destructive effect of the weaver gene. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1997;48:571–579. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970615)48:6<571::aid-jnr10>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss B, Neu A, Roeper J. The weaver mouse gain-of-function phenotype of dopaminergic midbrain neurons is determined by coactivation of wvGirk2 and K-ATP channels. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:8839–8848. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08839.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R, Yellen G. Mutations affecting TEA blockade and ion permeation in voltage-activated K+ channels. Science. 1990;250:276–279. doi: 10.1126/science.2218530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro B, Kennedy ME, Velimirovic B, Bhat D, Peterson AS, Clapham DE. Nonselective and G βγ-insensitive weaver K+ channels. Science. 1996;272:1950–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotera P, Orrenius S. The role of calcium in apoptosis. Cell Calcium. 1998;23:173–180. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA, Williams JT, Surprenant A, Christie MJ. μ and δ receptors belong to a family of receptors that are coupled to potassium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1987;84:5487–5491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil N, Cox DR, Bhat D, Faham M, Myers RM, Peterson AS. A potassium channel mutation in weaver mice implicates membrane excitability in granule cell differentiation. Nature Genetics. 1995;11:126–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penington NJ, Kelly JS, Fox AP. Whole cell recordings of inwardly rectifying K+ currents activated by 5-HT1A receptors on dorsal raphe neurons of the adult rat. The Journal of Physiology. 1993a;469:407–426. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penington NJ, Kelly JS, Fox AP. Unitary properties of potassium channels activated by 5-HT in acutely isolated rat dorsal raphe neurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1993b;469:387–405. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkel DJ, Hestrin S, Sah P, Nicoll RA. Excitatory synaptic currents in Purkinje cells. Proceedings of the Royal Society. 1990;B 241:116–121. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1990.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce A, Bueno E, Kentros C, Miera E V-SD, Chow A, Hillman D, Chen S, Zhu L, Wu MB, Wu X, Rudy B, Thornhill WB. G-protein-gated inward rectifier K+ channel proteins (GIRK1) are present in the soma and dendrites as well as in nerve terminals of specific neurons in the brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:1990–2001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-01990.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P, Sidman RL. Sequence of developmental abnormalities leading to granule cell deficit in cerebellar cortex of weaver mutant mice. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1973a;152:103–132. doi: 10.1002/cne.901520202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P, Sidman RL. Organization of cerebellar cortex secondary to deficit of granule cells in weaver mutant mice. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1973b;152:133–161. doi: 10.1002/cne.901520203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roffler-Tarlov S, Graybiel AM. Expression of the weaver gene in dopamine-containing neural systems is dose-dependent and affects both striatal and nonstriatal regions. Journal of Neuroscience. 1986;6:3319–3330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-11-03319.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MJ, Sawyer BD, Perry KW, Fuller RW, Foreman MM, Ghetti B. Dopamine deficiency in the weaver mutant mouse. Journal of Neuroscience. 1982;2:376–380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-03-00376.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman RL. Cell surface properties and the expression of inherited brain diseases in mice. In: Bolis L, Hoffman JF, Leaf A, editors. Membranes and Disease. New York: Raven Press; 1976. pp. 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Signorini S, Liao Y, Duncan S, Jan L, Stoffel M. Normal cerebellar development by susceptibility to seizures in mice lacking G protein-coupled, inwardly rectifying K+ channel GIRK2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:923–927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman SK, Kofuji P, Dougherty DA, Davidson N, Lester HA. A regenerative link in the ionic fluxes through the weaver potassium channel underlies the pathophysiology of the mutation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:15429–15434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesinger PA, Patil N, Liao YJ, Jan YN, Jan LY, Cox DR. Functional effects of the mouse Weaver mutation on G-protein gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Neuron. 1996;16:321–331. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesinger PA, Stoffel M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Defective gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptor-activated inwardly rectifying K+ currents in cerebellar granule cells isolated from weaver and girk2 null mutant mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:12210–12217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeyne RJ, Goldowitz D. Development and death of external granular layer cells in the weaver mouse cerebellum: A quantitative study. Journal of Neuroscience. 1989;9:1608–1620. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01608.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeyne RJ, Goldowitz D. Purkinje cell loss is due to a direct action of the weaver gene in Purkinje cells: evidence from chimeric mice. Brain Research Developmental Brain Research. 1990;52:211–218. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90237-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, Mermelstein PG, Goldowitz D. The weaver mutation of GIRK2 results in a loss of inwardly rectifying K+ current in cerebellar granule cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:1–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong YH, Wei JJ, Zhang SW, Strong JA, Dlouhy SR, Hodes ME, Ghetti B, Yu L. The weaver mutation changes the ion selectivity of the affected inwardly rectifying potassium channel GIRK2. FEBS Letters. 1996;390:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00632-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triarhou LC, Low WC, Ghetti B. Transplantation of ventral mesencephalic anlagen to hosts with genetic nigrostriatal dopamine deficiency. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1986;83:8789–8793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triarhou LC, Norton J, Ghetti B. Mesencephalic dopamine cell deficit involves areas A8, A9 and A10 in weaver mutant mice. Experimental Brain Research. 1988;70:256–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00248351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tymianski M, Spigelman I, Zhang L, Carlen PL, Tator CH, Charlton MP, Wallace MC. Mechanism of action and persistence of neuroprotection by cell-permeant Ca2+ chelators. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1994;14:911–923. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui-Tei K, Sato S, Miyake T, Miyata Y. Induction of apoptosis in a Drosophila neuronal cell line by calcium ionophore. Neuroscience Letters. 1996;203:191–194. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verina T, Norton JA, Sorbel JJ, Triarhou LC, Laferty D, Richter JA, Simon JR, Ghetti B. Atrophy and loss of dopaminergic mesencephalic neurons in heterozygous weaver mice. Experimental Brain Research. 1997;113:5–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02454137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelweid CM, Verina T, Norton J, Harruff R, Ghetti B. Hypospermatogenesis is the cause of infertility in the male weaver mutant mouse. Journal of Neurogenetics. 1993;9:89–104. doi: 10.3109/01677069309083452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, Colmers WF, Pan ZZ. Voltage- and ligand-activated inwardly rectifying currents in dorsal raphe neurons in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:3499–3506. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-09-03499.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willinger M, Margolis DM. Effect of the weaver (wv) mutation on cerebellar neuron differentiation. I. Qualitative observations of neuron behavior in culture. Developmental Biology. 1985;107:156–172. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womack M, Thompson K, Fanselow E, Augustine GJ, Peterson A. Elevated intracellular calcium levels in cerebellar granule neurons of weaver mice. NeuroReport. 1998;9:3391–3395. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199810260-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won L, Ghetti B, Heller B, Heller A. In vitro evidence that the reduction in mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons in the weaver heterozygote is not due to a failure in target cell interaction. Experimental Brain Research. 1997;115:174–179. doi: 10.1007/pl00005679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullner U, Loschmann PA, Weller M, Klockgether T. Apoptotic cell death in the cerebellum of mutant weaver and lurcher mice. Neuroscience Letters. 1995;200:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12090-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]