Abstract

Turtle cochlear hair cells are electrically tuned by a voltage-dependent Ca2+ current and a Ca2+-dependent K+ current (IBK(Ca)). The effects of intracellular calcium buffering on electrical tuning were studied in hair cells at apical and basal cochlear locations tuned to 100 and 300 Hz, respectively.

Increasing the intracellular BAPTA concentration changed the hair cell's resonant frequency little, but optimized tuning at more depolarized membrane potentials due to a positive shift in the half-activation voltage (V½) of the IBK(Ca).

The shift in V½ depended similarly on BAPTA concentration in basal and apical hair cells despite a 2·4-fold difference in the size of the Ca2+ current at the two positions. The Ca2+ current amplitude increased exponentially with distance along the cochlea.

Comparison of V½ values and tuning properties using different BAPTA concentrations with values measured in perforated-patch recordings gave the endogenous calcium buffer as equivalent to 0·21 mM BAPTA in low-frequency cells, and 0·46 mM BAPTA in high-frequency cells.

High conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels recorded in inside-out membrane patches were 2-fold less Ca2+ sensitive in high-frequency than in low-frequency cells.

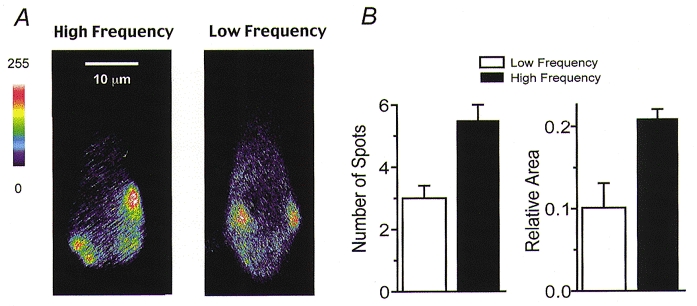

Confocal Ca2+ imaging using the fluorescent indicator Calcium Green-1 revealed about twice as many hotspots of Ca2+ entry during depolarization in high-frequency compared to low-frequency hair cells.

We suggest that each BKCa channel is gated by Ca2+ entry through a few nearby Ca2+ channels, and that Ca2+ and BKCa channels occupy, at constant channel density, a greater fraction of the membrane area in high-frequency cells than in low-frequency cells.

Hair cells of the turtle cochlea are frequency tuned through the gating of large-conductance Ca2+-dependent K+ (BKCa) channels that are activated by Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels (Art & Fettiplace, 1987). The resonant frequency of a hair cell is correlated with its complement of Ca2+ and BKCa channels, cells tuned to higher frequencies possessing more channels of both types (Wu et al. 1995). To achieve local Ca2+ concentrations of sufficient magnitude to activate the BKCa, the Ca2+ and BKCa channels are thought to be co-localized in clusters of high channel density proposed to coincide with the synaptic release sites (Roberts et al. 1990). The multiple hotspots of Ca2+ entry observed with confocal microscopy (Issa & Hudspeth, 1994; Tucker & Fettiplace, 1995; Hall et al. 1997) are consistent with the clustered arrangement of Ca2+ channels on the basolateral aspect of hair cells. With such an arrangement, how are the numbers of Ca2+ channels regulated with changes in the cell's resonant frequency? For example, an increase in resonant frequency might be associated with either a higher Ca2+ channel density in a cluster or an enlargement of the membrane area devoted to the clusters. In support of the latter hypothesis, there is evidence in both turtle (Sneary, 1988) and chicken (Martinez-Dunst et al. 1997) that the number of hair cell transmitter release sites and, by implication, Ca2+-channel clusters, increases along the tonotopic axis of the cochlea.

Both the amplitude and timing of Ca2+ excursions at the BKCa channel will depend on the microstructure of the clusters, especially the density of the two channel types. Local Ca2+ gradients will also be accentuated by the concentration and kinetics of the mobile intracellular calcium buffers (Stern, 1992; Roberts, 1994; Naraghi & Neher, 1997). Depending on the overall channel density and the buffer concentration, each BKCa channel might be influenced by all Ca2+ channels in the cluster or by only a few nearest neighbours. To approach this problem we have examined the effects of exogenous calcium buffers on the activation of the IBK(Ca) and the hair cell's tuning properties. Comparison with results derived from perforated-patch recordings have allowed us to estimate the effective concentration of endogenous calcium buffer (Zhou & Neher, 1993; Roberts, 1993; Tucker & Fettiplace, 1996; Ricci et al. 1998). We have collected data from hair cells at two cochlear locations, enabling us to study cells with different magnitudes of Ca2+ current. Our results suggest that each BKCa channel is gated by Ca2+ entry through a few adjacent Ca2+ channels, and that an increase in channel numbers is accomplished by augmentation of clusters at constant channel density.

METHODS

Preparation

The preparation and methods of hair cell recording in the intact basilar papilla have been described previously (Ricci & Fettiplace, 1997). Turtles (Trachemys scripta elegans, carapace length 75–100 mm) were decapitated and the cochlea dissected out using procedures approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of Wisconsin (protocol number A3368-01). The tectorial membrane was removed following 20 min incubation in turtle saline, composition (mM): NaCl, 125; KCl, 4; CaCl2, 2.8; MgCl2, 2.2; sodium pyruvate, 2; glucose, 8; NaHepes, 10 (pH 7.6) containing up to 50 μg ml−1 of protease (Sigma type XXIV). The preparation was transferred to a recording chamber on the stage of a Zeiss Axioskop FS microscope and viewed through a × 63 water immersion objective (NA 0.9) and a Hamamatsu C2400 CCD camera. The chamber was continuously perfused with turtle saline. For voltage-clamp measurements at the low-frequency location, 1 mM 4-aminopyridine and 0.1 μM apamin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) were added to the saline to block K+ channels other than the large-conductance BKCa channel. Other K+ channels are known to occur in low frequency hair cells (Goodman & Art, 1996), and their presence complicates the analysis of the Ca2+ currents and IBK(Ca).

Whole-cell currents were measured with a List EPC-7 amplifier attached to a borosilicate patch electrode that was advanced from the abneural edge of the basilar papilla to seal on to the basolateral membrane of a hair cell (Ricci & Fettiplace, 1997). Recordings usually came from cells in the middle of the papilla two to three cells in from the abneural edge. Hair cell location and total length of the basilar papilla were documented at the end of an experiment. Most recordings came from cells in two regions, at about 0.3 (the apical location) or 0.6 (the basal location) of the distance along the cochlea from the low-frequency end. Measurements are given as means ± 1 standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Membrane currents were stored on a Sony PCM108 recorder at a bandwidth of 0–20 kHz. Experiments were performed at 21–23°C.

Electrical recordings

Whole-cell electrodes were normally filled with a solution containing (mM): KCl, 125; Na2ATP, 3; MgCl2, 2; KHepes, 10, adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH, with the addition of various concentrations (0.1-30 mM) of the calcium buffers BAPTA, nitro-BAPTA, (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) or EGTA (Fluka, Ronkonkoma, NY, USA). With 10 or 30 mM calcium buffer, the KCl concentration was reduced to maintain constant osmolarity. To measure voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents, Cs+ was substituted for K+ as the major monovalent ion (see below). After applying up to 50 % series resistance compensation, electrode access resistances were 3–10 MΩ, giving recording time constants of 30–150 μs. Membrane potentials were corrected for the uncompensated series resistance and junction potential.

The method of perforated-patch recording was identical to that used previously (Horn & Marty, 1988; Ricci et al. 1998). The electrode solution contained (mM): potassium aspartate, 110; KCl, 15; MgCl2, 2; K4BAPTA, 0.1 or 1; Hepes, 10; neutralized to pH 7.2 with KOH. For each experiment, 2.4 mg nystatin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) was dissolved in 10 μl dry dimethyl sulphoxide and diluted 1:1000 in the stock intracellular solution. The patch pipette was tip filled with antibiotic-free stock solution, and back-filled with the nystatin solution to prevent the antibiotic leaking into the bath during penetration of the papilla and sealing to the membrane. In general it took at least 15 min from sealing to achieve a stable low-resistance patch perforation, after which time the recordings were stable for at least a further 30 min. During this period there was no evidence of either run down in the currents or Ca2+ loading. Although the perforated-patch recordings did not allow wash in of ATP, the Ca2+-ATPase was clearly functional, since there was never any indication during repeated depolarizations of the slow component of the IK(Ca) tail current that appeared when the Ca2+-ATPase was blocked with vanadate (see Results). Series resistances for the perforated-patch recordings were 7–20 MΩ after applying up to 40 % series resistance compensation. Potentials were adjusted for a 10 mV junction potential between the potassium aspartate solution and the external saline.

The amplitude of the Ca2+ current in a given hair cell showed up to a 2-fold increase during the first 5 min after attaining the whole-cell configuration. A time-dependent growth of the IK(Ca) was also observed in both whole-cell and perforated-patch measurements, which may reflect the augmentation of the Ca2+ current. However, the variations in IK(Ca) size were not accompanied by any significant shift in the channel's activation curve. For example, 6 of the 11 cells recorded in perforated-patch mode showed a 35 % mean increase in IK(Ca) during the course of the recording, but less than 1 mV mean shift in the half-activating voltage (V1/2, see eqn (1)). It was difficult to study the phenomenon systematically due to the time required for equilibration of the patch electrode solution with the cytoplasm in whole-cell recording, and the time to achieve low-resistance access in perforated-patch mode. However, measurements were not normally taken until the current amplitude had stabilized, and the activation curve parameters quoted in the Results are those obtained when a steady state had been reached.

Macropatch recordings

IK(Ca) were measured in inside-out membrane macropatches excised from hair cells at known locations (Art et al. 1995). Electrodes (resistance 0.5-1 MΩ), connected to an Axopatch 200 amplifier, were filled with a solution (mM): KCl, 130; K2EGTA, 5; KHepes, 10; pH 7.4. The intracellular face of the patch was exposed to solutions (mM): KCl, 130; K4dibromo BAPTA, 2 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA); dithiothreitol, 1; KHepes, 10, pH 7.4, with different amounts of CaCl2 added to yield free Ca2+concentrations from 0.3-20 μM. Solutions with free Ca2+ greater than 20 μM contained no dibromoBAPTA. Ca2+ activities in all samples were measured with a MI-600 Ca2+ electrode (Microelectrodes Inc., Londonderry, NH, USA) calibrated in a series of standard Ca2+ buffer solutions (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA). Leak currents, measured in a nominally zero-Ca2+ solution containing 10 mM EGTA, were subtracted from all traces. Current responses were filtered with an eight-pole Bessel filter at 5 kHz prior to digitization and analysis.

Confocal imaging

The composition of the patch-electrode solution, both for imaging and for measuring voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents, was (mM): CsCl, 110; Na2ATP, 3; MgCl2, 2; Na2GTP, 0.3; creatine phosphate, 5; ascorbic acid, 1; EGTA (or BAPTA), 1; Hepes, 10; adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH. Spatial distributions of intracellular Ca2+ transients were measured with 0.1 mM K4 Calcium Green-1 as the 3000 Da-dextran conjugate (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) in the patch-electrode solution. Cells were illuminated with the 488 nm line of an argon laser and fluorescence images, passed through a 515 nm long pass filter, were collected with an Odyssey real-time laser scanning confocal microscope (Noran Instruments, Middleton, WI, USA) attached to the TV port of the Axioskop FS. Images were stored on an S-VHS videocassette recorder (Sony SVO 9500 MD) or an optical disc recorder (Panasonic TQ 3031F). Images were later analysed with Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA, USA) on a Pentium computer equipped with a Matrox LC image board. Other details about the confocal microscope and method of analysis are given in Tucker & Fettiplace (1995).

RESULTS

Map of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ current along the tonotopic axis

Recording in the isolated basilar papilla allows the ionic properties of a hair cell to be measured in cells of known location. The turtle basilar papilla is tonotopically organized with a hair cell's resonant frequency increasing along the long axis of the papilla. Figure 1 shows examples of the tuning properties of hair cells, the resonant frequency being deduced from the period of oscillations at the onset of an injected current step. The inferred tonotopic map is similar to that described in the turtle half-head (Crawford & Fettiplace, 1980). Figure 2 shows that the magnitude of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ current increased in parallel with the cell's resonant frequency. To construct the plot, results from cells within each 100 μm length of the papilla were pooled, giving mean values that show an exponential increase in current size with fractional distance along the papilla from the low-frequency end (Fig. 2C). The value of 0.35 for the space constant λ, is similar to the average value of λ for the frequency map (0.37; Wu & Fettiplace, 1996), indicating that the hair cell Ca2+ current increases in proportion to resonant frequency. For subsequent analysis of IBK(Ca), we compared measurements at two locations with mean fractional distances along the papilla of 0.29 ± 0.05 (low frequency) and 0.6 ± 0.04 (high frequency). The peak Ca2+ current was 0.30 nA at the low-frequency location and 0.72 nA at the high-frequency location. The Ca2+ current activation curve was similar for 1 and 10 mM BAPTA intracellular calcium buffer (Fig. 2B).

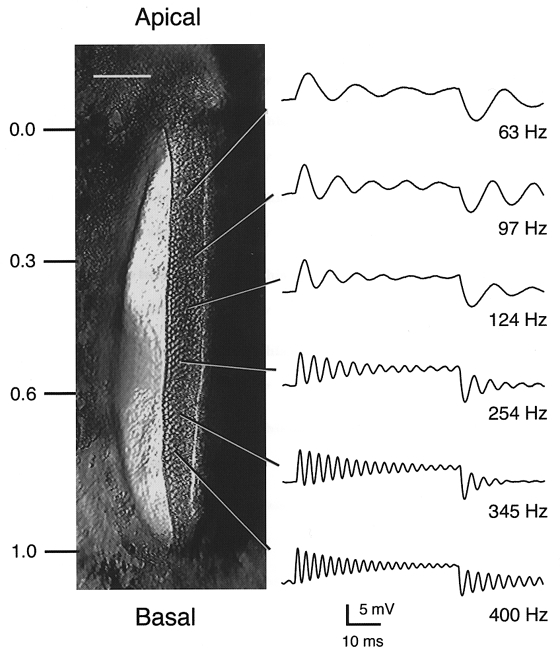

Figure 1. Tonotopic organization of the turtle basilar papilla.

Left, surface view of the basilar papilla during an experiment showing the epithelial strip of hair cells on the right-hand side, apical (lagenar) end at the top and basal (saccular) end at the bottom. Scale bar, 100 μm. Fractional distance (d) from lagena end shown on left. Most of the measurements of the buffer effects were taken at values of d of approximately 0.3 or 0.6. Right, examples of electrical resonance recorded in hair cells at the locations indicated. Each record is the response to 25 presentations of a small depolarizing current step evoking oscillations in membrane potential at the start and end of the step. Recordings were obtained with electrodes containing 0.1 or 1 mM BAPTA as the calcium buffer. For some of the cells, the resting potential was about -70 mV, and thus the current step was superimposed on a standing current to depolarize the cell into the range where tuning was optimal. Resonant frequencies are given next to traces. Membrane potentials prior to current step: -51 mV (63 Hz), -47 mV (97 Hz), -47 mV (124 Hz), -39 mV (254 Hz), -44 mV (345 Hz) and -44 mV (400 Hz).

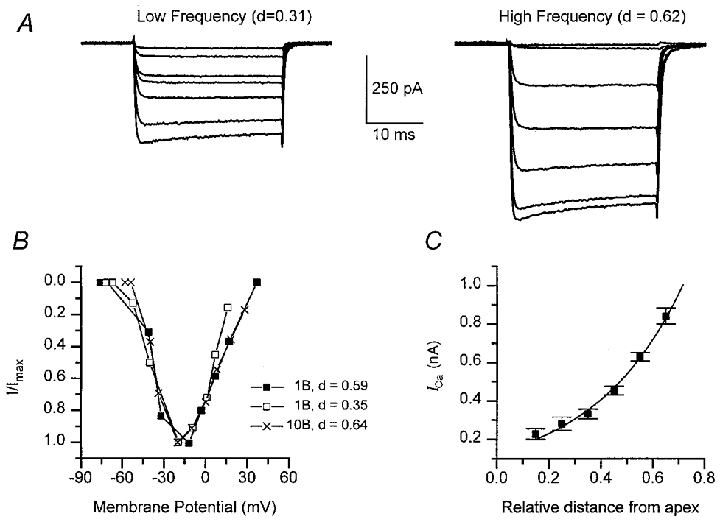

Figure 2. Variations in peak Ca2+ current with hair cell location.

A, voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents in hair cells at a low-frequency position (d, the distance along papilla, 0.3) and a high-frequency position (d = 0.6). Average currents recorded with Cs+-filled electrodes for depolarizations from -80 mV, 1 mM intracellular BAPTA. Membrane potentials during steps were (mV): -55, -50, -45, -42, -40, -31, -21 (low-frequency cell) and -51, -49, -40, -38, -33, -20, -10 (high-frequency cell). Each current response is the average of 5–25 stimuli. B, examples of steady-state current-voltage relationships for the Ca2+ current in three other cells with different internal BAPTA concentration, currents scaled to peak values. Peak currents and cochlear location, d:□, 1 mM BAPTA, 0.44 nA, d = 0.35; ▪, 1 mM BAPTA, 0.78 nA, d = 0.59; ×, 10 mM BAPTA, 1.04 nA, d = 0.64. C, plot of the peak Ca2+ current (ICa) against hair cell distance (d) from the apical end of the papilla. Each point is the mean ± 1 s.e.m of at least nine measurements in a 100 μm long region. Smooth curve: ICa=ICa(0) exp(d/λ), with ICa(0) = 0.13 nA and λ= 0.35, where λ is the space constant.

Effects of calcium buffers on activation of the BKCa channel

Ca2+ influx via the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel serves the dual function in hair cells of gating the BKCa channel involved in frequency tuning (Art & Fettiplace, 1987; Roberts et al. 1990), and controlling exocytosis of neurotransmitter (Parsons et al. 1994). The effects of intracellular calcium buffering on the BKCa channel was assessed from shifts in the channel's voltage-activation curve obtained from tail current measurements. The procedure is illustrated in Fig. 3A for perforated-patch recordings where the cells retain their native mobile buffer. The results demonstrate differences in BKCa channel performance at the two papillar locations. IBK(Ca) were approximately 2-fold larger and faster at the high-frequency location (Fig. 3A). At a holding potential of -60 mV, the maximum tail currents and time constants of deactivation for perforated-patch were 0.46 ± 0.04 nA and 1.45 ± 0.06 ms (n = 6) and 0.96 ± 0.08 nA and 0.65 ± 0.03 ms (n = 5) at the low-frequency and high-frequency locations, respectively. Thus cells tuned to higher frequencies possess larger and faster IBK(Ca), which agrees with previous observations on isolated hair cells (Art & Fettiplace, 1987; Art et al. 1993). Figure 3B shows plots of the tail current I, against membrane potential V, which have been fitted with the Boltzmann equation:

| (1) |

where Imax is the maximum tail current, V1/2 is the half-activation voltage and VS is the slope factor. V1/2 and VS had mean values of -46 ± 0.8 mV and 1.8 ± 0.2 mV (n = 6; low-frequency location) and -42 ± 1.0 mV and 2.3 ± 0.5 mV (n = 5; high-frequency location).

Figure 3. BKCa channel currents under different calcium buffering conditions.

A, families of tail currents obtained with perforated-patch recordings for 25 ms depolarizing voltage steps of increasing amplitude from a holding potential of -60 mV. The top family was obtained for a high-frequency location (d = 0.63) and the bottom family from a low-frequency location (d = 0.31). Note that the tail currents, representing deactivation of the BKCa channel, are larger and faster in the high-frequency hair cell. Each trace is the average of 5–25 presentations. B, activation curves of the IBK(Ca) current obtained from plots of the tail current (I), against membrane potential (V), during the voltage step for the two cells shown in A. The smooth curves are fits to eqn (1) with values of maximum current (Imax), half-activation voltage (V1/2) and slope factor (VS) of: high frequency, 1.22 nA, -41 mV, 1.4 mV (▪); low frequency, 0.58 nA, -46 mV, 2.1 mV (^). C, average IBK(Ca) in three different cells recorded with 0.1, 10 and 30 mM intracellular BAPTA. The membrane potential during the voltage step is given above each trace, holding potential -60 mV. Note that more depolarization is needed to activate the outward current in higher concentrations of BAPTA. In 30 mM BAPTA, the smallest depolarizations elicit only inward Ca2+ current. Each trace is the average of 5–25 presentations.

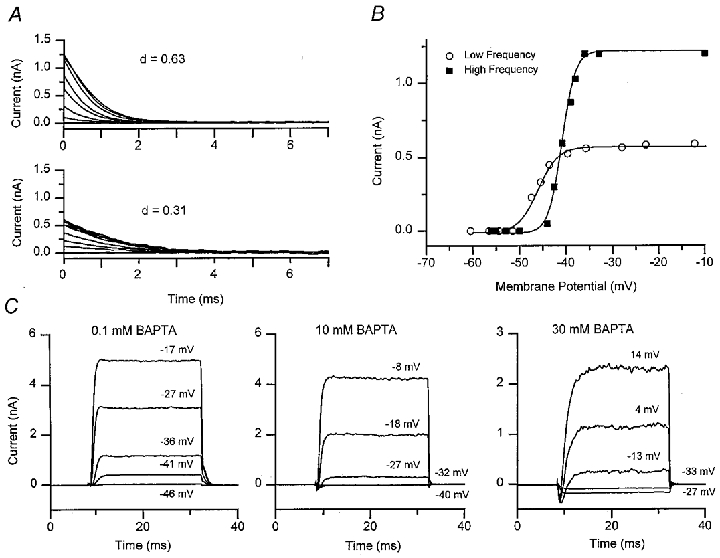

IK(Ca) activation was similarly characterized with exogenous calcium buffers in whole-cell recording (Fig. 3C). At both papillar locations, raising the BAPTA concentration from 1 to 10 mM shifted the current activation to more depolarized potentials (Fig. 4). Values of VS from whole cell measurements were similar to those obtained in perforated- patch recordings (Fig. 4D). The V1/2 values were independent of the size of the maximum current, but there was an ∼4 mV difference between the V1/2 values at the low- and high-frequency locations for all BAPTA concentrations. A possible reason for this disparity is examined later. The effective concentration of endogenous mobile buffer can be estimated by comparison with the V½ values obtained in the perforated-patch recordings. Interpolation from the plots in Fig. 4C gave the endogenous buffer as equivalent to 0.20 mM BAPTA at the low-frequency location and 0.47 mM BAPTA at the high-frequency location. The results suggest an increase in endogenous buffer concentration towards the high-frequency end of the cochlea.

Figure 4. Effects of intracellular calcium buffer on IBK(Ca) activation.

A, example of activation curves obtained from tail current measurements as in Fig. 3A, for cells at a high-frequency location (d = 0.62). Intracellular calcium buffer: 0.1 mM BAPTA (^); 1 mM BAPTA (▵); 10 mM BAPTA (×) and perforated-patch measurements (PP) for endogenous buffer (▪). B, activation curves obtained from tail current measurements for cells at a low-frequency location (d = 0.32). Symbols as in A. For each set of points in A and B, the tail current has been normalized to its maximum value and fitted with a Boltzmann equation (eqn (1)) to obtain half-activation voltage V1/2, and slope factor VS, for each condition. C, half-activation voltage V1/2, plotted against BAPTA concentration. Each point is the mean ± 1 s.e.m. for the low-frequency location (^) and the high-frequency location (•), the number of measurements averaged being given beside each point. The construction lines are interpolations to derive the endogenous buffer from V1/2 values of -42 mV (high frequency) and -46 mV (low frequency) obtained with perforated-patch recording (see text). D, slope factor VS, plotted against BAPTA concentration for the low-frequency location (^) and the high-frequency location (•). Perforated-patch values for VS were 1.8 ± 0.2 mV (low frequency) and 2.3 ± 0.5 mV (high frequency).

The effect of buffer concentration most probably stems from the mobile buffer restricting the spread of Ca2+ away from its source, the Ca2+ channel. Thus greater depolarization is needed to achieve the same concentration of Ca2+ at its binding site on the BKCa channel. With up to 10 mM BAPTA, it was possible to activate fully the IBK(Ca) by suitable depolarization. However, when the BAPTA concentration was raised to 30 mM, the IBK(Ca) could not be completely activated with depolarization, even to the peak of the Ca2+ current at -20 mV, and the smallest depolarizations evoked only inward Ca2+ current (Fig. 3C). V½ values were measured for two other calcium buffers, the slow buffer EGTA and the low-affinity buffer nitroBAPTA. At the high-frequency location, the mean V½ value was -41 ± 1.0 mV (n = 11) for 10 mM EGTA, and -40 ± 0.7 mV (n = 7) for 1 mM nitroBAPTA. These results indicate that nitroBAPTA has a comparable efficacy to BAPTA but EGTA is about 15-fold less effective. NitroBAPTA, although having a low Ca2+ affinity (Kd 40 μM), has the same forward rate constant as BAPTA, whereas EGTA has a similar affinity to BAPTA (Kd∼0.2 μM) but binds Ca2+ at least 100-fold slower (Naraghi, 1997). Our results agree with those of Roberts (1993), arguing for the importance of the forward rate constant rather than the buffer affinity in influencing Ca2+ activation of the hair cell BKCa channel. The results also imply, based on the analysis of Naraghi & Neher (1997), that the two channels must be close neighbours.

Ca2+ accumulation near the BKCa channel

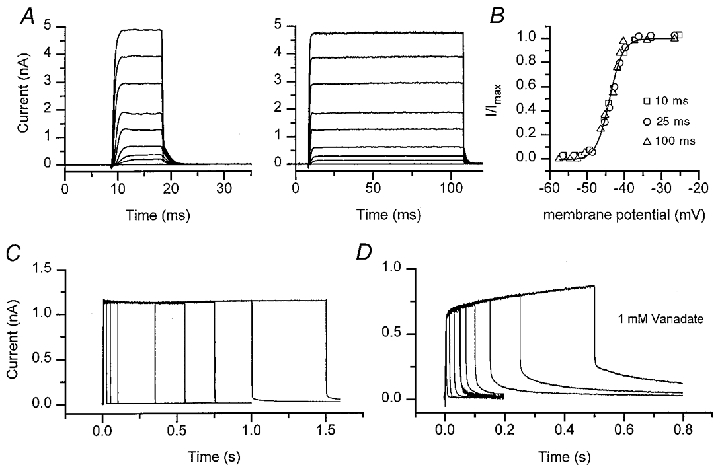

Ca2+ entering through the voltage-dependent channels will be rapidly bound by cytoplasmic buffers and then extruded on a slower time scale by a Ca2+-ATPase (Tucker & Fettiplace 1995). During a prolonged depolarization, Ca2+ might be expected to accumulate beneath the membrane, its concentration growing due to diffusion from neighbouring channels. The BKCa channel-activation curves in Fig. 4 were constructed from 25 ms depolarizing voltage steps. Figure 5 shows results from a cell where the duration of the voltage step was varied from 10 to 100 ms. For all amplitudes of depolarization, the outward current attained a maximum level within 2 ms, little longer than it takes the Ca2+ current to fully activate (Art & Fettiplace, 1987), and then remained constant for the duration of the step. Activation curves deduced from tail currents were identical for different stimulus durations (Fig. 5B). In other experiments (not illustrated), including a perforated-patch recording, the amplitude of the IK(Ca) was found to be invariant with duration of the voltage step between 2 ms and more than 1000 ms. These results suggest that the time course of free Ca2+ at the BKCa channel resembles that of the Ca2+ current itself, and implies that each Ca2+ channel influences only nearby BKCa channels.

Figure 5. BKCa channel activation is independent of the voltage step duration.

A, average currents in response to depolarizing voltage steps of duration 10 ms (left) and 100 ms (right), holding potential of -60 mV. B, IBK(Ca) activation curves for cell in A, derived from the tail currents at the end of voltage steps of duration 10 ms (□), 25 ms (^) and 100 ms (▵). The tail currents (I) have been normalized to their maximum value (Imax), which was 4.8 nA, independent of step duration. Smooth curve is a fit to eqn (1) with half-activation voltage V1/2=−44 mV and slope factor VS= 3.5 mV. C, average currents in response to sub-saturating depolarizating voltage steps, with durations from 25 to 1500 ms. Note that the maximum current is independent of the step duration. D, same experiment as in C in another cell, with electrode solution containing 1 mM vanadate to block Ca2+-ATPase pumps. Note the increase in steady current with step duration and the slow component of the tail current, which may reflect clearance of Ca2+ accumulated during the step. In both C and D, the voltage was stepped from a holding potential of -60 to -44 mV corresponding to the V1/2 of the channel. Each trace is the average of 5–25 responses. In all panels, the intracellular calcium buffer was 0.1 mM BAPTA.

Rapid equilibration of Ca2+ in the vicinity of its target the BKCa channel, must partly depend on fast diffusion away from the source without local saturation of the calcium buffer. A constant IBK(Ca) was found for sub-maximal stimulation even with the lowest buffer concentration, 0.1 mM BAPTA. However, when the Ca2+ extrusion mechanism was blocked by adding 1 mM vanadate to the internal solution, the current acquired a secondary growth phase and a slow component of the tail current on repolarization (Fig. 5D). Both features are symptomatic of lack of clearance of Ca2+ in the absence of an extrusion process, implying that the Ca2+-ATPase is vital for maintaining intracellular gradients away from the channel cluster to prevent local buffer saturation and accumulation of Ca2+. Slow components of the tail current were never seen in control recordings, either whole cell or perforated patch, suggesting that in those recordings, Ca2+ extrusion via the Ca2+-ATPase was fully operational.

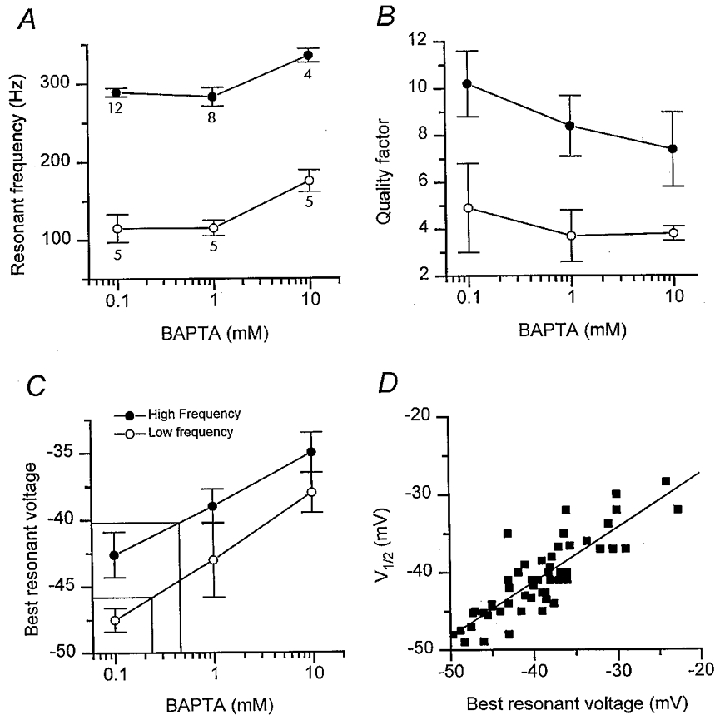

Effects of the calcium buffer on hair cell tuning

Calcium buffer effects on electrical tuning were studied in current-clamp conditions, where under-damped voltage resonance could be evoked by injection of small current pulses (Fig. 1). Both the frequency of the voltage oscillations (Fo) and their time constant of decay (τ) depend on membrane potential, (Crawford & Fettiplace, 1981). Therefore a hair cell's resonant frequency was defined as that frequency at which the quality factor (Q) was maximal. Q is given by ((πFoτ)2+ 0.25)½, where τ is the decay time constant of the oscillations (Crawford & Fettiplace, 1981). The membrane potential for maximal Q, referred to as the best resonant voltage, became systematically more depolarized with higher BAPTA concentrations. The best resonant voltage correlated with the V½ for the BKCa channel (Fig. 6D), which reflects the balance between the inward Ca2+ current and the outward K+ current needed to achieve optimal tuning. As with the V½ values, there was an ∼5 mV difference between the best resonant voltages in the low- and high-frequency cells.

Figure 6. Effects of intracellular calcium buffer on electrical tuning.

A, hair cell resonant frequencies plotted against concentration of BAPTA in electrode solution. The resonant frequency was obtained from the period of the oscillations at the onset of a current step that produced the sharpest tuning (the largest quality factor). The membrane potential at which tuning was sharpest is referred to as the ‘best resonant voltage’. Each point is the mean ± 1 s.e.m of measurements at the low-frequency location (^) and at the high-frequency location (•). The number of values averaged is given beside each point, the same numbers apply also to the measurements in B and C. B, maximal quality factors of electrical tuning plotted against concentration of BAPTA in electrode solution, conventions as in A. Definition of quality factor is given in text. The small changes in Fo and Q with increasing BAPTA concentration were not statistically significant using a one-way ANOVA test at the 0.01 confidence level. C, the membrane potential at which the quality factor was maximal (best resonant voltage) plotted against internal concentration of BAPTA for cells at the low-frequency location (^) and at the high-frequency location (•). Construction lines are interpolations to derive the endogenous buffer from the ‘best resonant voltages’ of -40.2 and -46 mV measured with perforated-patch recording at the high- and low-frequency locations, respectively. D, the half-activation voltage of the BKCa channel (V1/2) is plotted against ‘best resonant voltage’ for all buffering conditions. The straight line is the least squares fit, slope 0.7 and regression coefficient, r = 0.85.

With perforated-patch recordings, the best resonant voltages for the low-frequency and high-frequency locations were -45.8 ± 1.0 mV (Fo= 97 ± 27 Hz; n = 5) and -40.2 ± 2.3 mV (Fo= 265 ± 14 Hz; n = 6). Using values for the best resonant voltage at the two locations, it was also possible to obtain a second estimate of the endogenous calcium buffer (Fig. 6C). Expressed as an equivalent BAPTA concentration, the mobile buffer was 0.22 mM in the low-frequency cells and 0.45 mM in the high-frequency cells. The concentrations are similar to those deduced from half-activation voltages for the IBK(Ca), supporting the notion of a cochlear gradient of endogenous calcium buffer. Owing to the correlation between the best resonant voltage and the V½ for the BKCa channel (Fig. 6D), the two methods for estimating endogenous buffer concentration are not independent.

Tuning was assessed during a period of several minutes in current clamp when the cell was depolarized to membrane potentials between -50 and -40 mV. Usually, in the absence of mechanotransduction, it was necessary to impose a holding current to bias the cell into the range where it was optimally tuned (Art & Fettiplace, 1987). On return to voltage clamp we observed a consistent increase in membrane capacitance that may reflect exocytosis of synaptic vesicles (Parsons et al. 1994). The cells initially had an average capacitance of approximately 12 pF, and responded to the period in current clamp with an increase of 2–3 pF. For those cells showing a capacitance increase, the magnitude of the change varied with cochlear location and was 1.9 ± 0.2 pF in 12 low-frequency cells and 2.9 ± 0.3 in 10 high-frequency cells. The likelihood of observing the capacitance increasing also depended on the nature of the exogenous calcium buffer. The fraction of cells showing an increase was 0.75 (0.1 BAPTA; nT= 8), 0.56 (1.0 mM BAPTA; nT= 18), 0.17 (10 mM BAPTA; nT= 12) and 0.70 (10 mM EGTA; nT= 13) where nT is the total number of cells in each group. Thus the capacitance change displayed a similar dependence on calcium buffer concentration to BKCa channel activation. BAPTA at 10 mM was needed to attenuate it significantly, but 10 mM EGTA had little effect. In 11 perforated-patch recordings, no increase in capacitance was observed (-0.2 ± 0.09 pF), which may be due to concurrent re-uptake of exocytosed membrane, a property lost in whole cell recordings from hair cells (Parsons et al. 1994). Our results lack the temporal resolution to distinguish between different pools of exocytosed vesicles which may possess different dependencies on calcium buffer concentration. Nevertheless, they suggest a component of the transmitter-release apparatus experiences a Ca2+ signal comparable to that activating the BKCa channel.

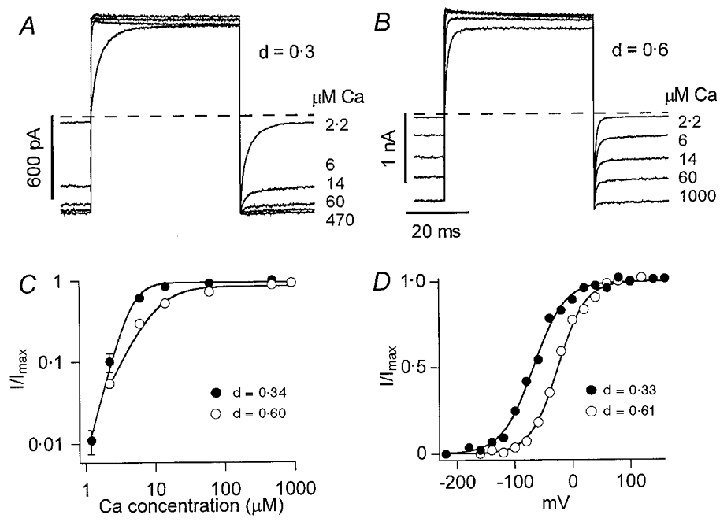

Ca2+ sensitivity of the BKCa channel

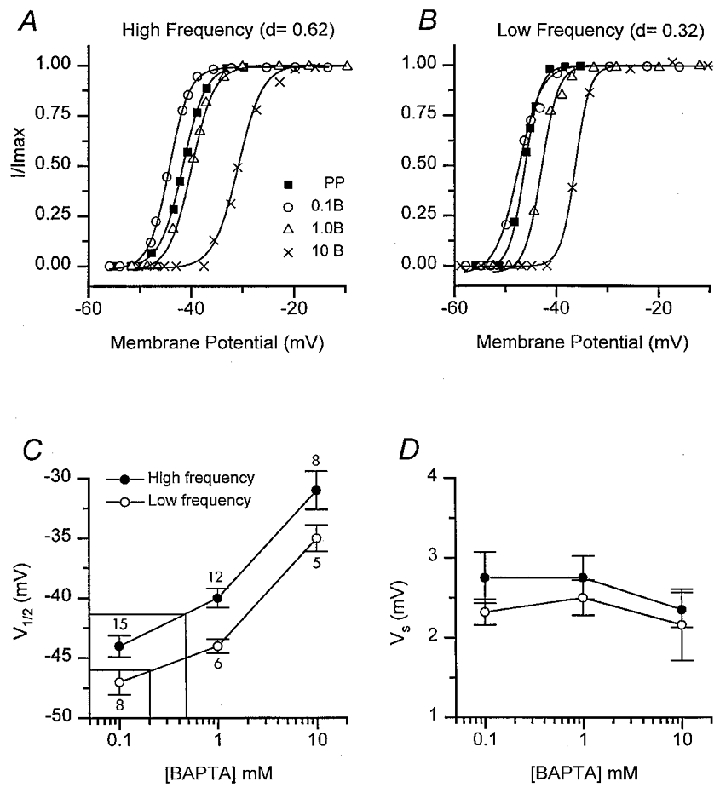

Figure 4 demonstrated that the IBK(Ca) activates at more depolarized potentials in high-frequency hair cells compared to low-frequency cells. One factor that might contribute to this disparity is a difference in the Ca2+ sensitivity of the BKCa channel. To test for this possibility, IK(Ca) were recorded in inside-out membrane macro patches from hair cells at two locations with fractional distances along the papilla of 0.34 ± 0.03 (low frequency) and 0.60 ± 0.01 (high frequency). Data were obtained on seven hair cells at each location with maximal patch currents of 0.12-0.68 nA (low frequency) and 0.2-1.4 nA (high frequency) at -50 mV. These currents correspond approximately to 10–100 BKCa channel per patch. Each patch was exteriorized from the hair cell epithelium so that its intracellular face could be exposed to a range of Ca2+ concentrations between 1 and 1000 μM, and IBK(Ca) were evoked with depolarizing voltage steps from -50 to +50 mV. Figure 7 illustrates the major differences observed in BKCa channels at the two positions. These were most conspicuous at -50 mV, where the high-frequency channels were less Ca2+ sensitive and deactivated more rapidly. For each patch, the current at -50 mV, normalized to its maximum value, was plotted against Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 7C). Fits to the Hill equation gave a half-saturating Ca2+ concentration (Ca1/2) of 5.8 ± 0.6 μM (low-frequency position) and 10.3 ± 0.6 μM (high-frequency position) with mean Hill coefficients of 2.9 and 1.9 at the low- and high-frequency positions, respectively. The deactivation of the currents at -50 mV in 2.5 μM Ca2+ could be fitted with a single exponential decay with a time constant of 2.4 ± 0.4 ms in low-frequency and 0.74 ± 0.05 ms in high-frequency cells.

Figure 7. BKCa channel properties in inside out patches.

A, average currents recorded in an inside-out membrane patch detached from a low-frequency hair cell (d = 0.3) for voltage steps from -50 to +50 mV in the presence of Ca2+ concentrations from 2.2 to 470 μM. Dashed line denotes zero current level. B, currents recorded in an inside-out patch from a high-frequency hair cell (d = 0.6) for voltage steps from -50 to +50 mV in Ca2+ concentrations from 2.2 to 1000 μM. Each trace in A and B is the average of between 100 and 250 responses. C, IBK(Ca) (I) scaled to its maximum value (Imax) is plotted against Ca2+ concentration in low-frequency (•) and high-frequency (^) hair cells. Each point is the mean ± 1 s.e.m of measurement on seven inside-out patches; for most of the points the s.e.m. is less than the symbol size. Smooth curves are fits to the Hill equation, I/Imax= 1/(1 + (Ca1/2/Ca)nH), with Ca½ and Hill coefficient (nH), respectively, of 5.8 μM and 2.9 (•) and 10.3 μM and 1.9 (^). D, BKCa channel activation curves for channels in a low-frequency hair cell (d = 0.33; •) and a high-frequency hair cell (d = 0.61; ^), derived from tail-current measurements (I) from a holding potential of -80 mV. Smooth curves are fits to eqn (1) with values of V1/2 and VS, respectively, of -68 and 27 mV (low frequency) and -26 and 24 mV (high frequency).

Further evidence supporting location-dependent variations in Ca2+ sensitivity of the BKCa channel was obtained from voltage-activation curves in a fixed Ca2+ concentration. For one patch at each position, it was possible to obtain a complete activation curve in 5 μM Ca2+ (Fig. 7D), from which a half-activation voltage of -68 mV was inferred for the low-frequency patch and -26 mV for the high-frequency patch. Owing to the combined Ca2+ and voltage dependence of the channels, the need for greater depolarization to activate the high-frequency channels is consistent with them being less Ca2+ sensitive. The reported Ca2+ sensitivities and deactivation time constants are both within the range of values previously reported for single BKCa channels in turtle isolated hair cells (Art et al. 1995). However, in the earlier measurements it was not possible to demonstrate a correlation between the two parameters. Such a correlation would fit with the notion that hair cells at different locations express distinct variants of the BKCa channels (Jones et al. 1999). Indeed, the alternatively spliced variants cloned from turtle hair cells possess the property that those with faster kinetics are less Ca2+ sensitive, which accords with the present results on the native channels.

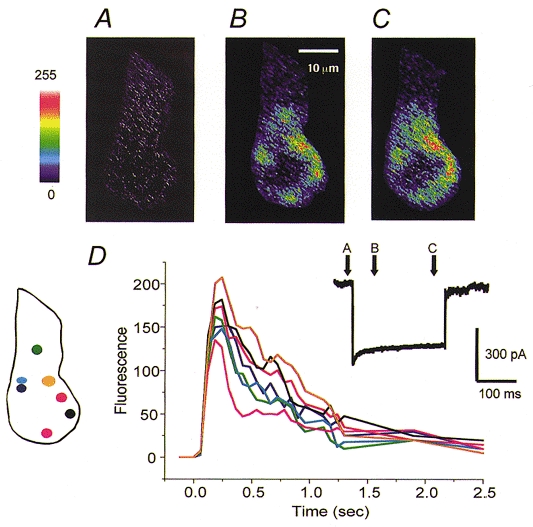

Hotspots of Ca2+ influx

In isolated turtle hair cells, Ca2+ influx via voltage-gated channels occurs over small regions or ‘hotspots’ confined to the basal half of the cell (Tucker & Fettiplace, 1995). The ability to record from hair cells at specific papillar locations allowed us to examine whether the structure of the hotspots varied with location to reflect the difference in maximum Ca2+ current. Regions of Ca2+ elevation were defined using the fluorescent dye Calcium Green-1. Following attachment of the whole-cell electrode, the cell was drawn onto its side in order to optimize spatial resolution in the confocal images. Figure 8A–C shows single images of a high-frequency hair cell captured before and during a 200 ms depolarization to -20 mV designed to maximally activate the Ca2+ current. The increase in intracellular Ca2+ was distributed over a ring around the nucleus, but there was evidence of punctate regions or ‘hotspots’ of fluorescence.

Figure 8. Hotspots of Ca2+ influx in a high-frequency hair cell.

Confocal images of a hair cell filled with Calcium Green-1 before (A) and during (B and C) a 200 ms depolarizing current step to -20 mV. Times at which the images were captured are shown as arrows above the Ca2+ current (inset). Pseudocolour scale on left corresponds to pixel intensities from 0 to 255. D, time course of the fluorescence changes in seven regions in response to the depolarization. Different traces correspond to the regions of the same colour shown in the schematic hair cell on the left. Orange region may contain multiple hotspots, but was judged to be a single spot on the criteria given in the text.

The lack of temporal resolution imposed by the frame rate hinders an accurate determination of the number of hotspots. To approach this problem, the time course of the fluorescence changes was characterized by constructing around the hotspots contours to correspond to a fixed Ca2+ level (Tucker & Fettiplace, 1995, 1996). Contours were initially drawn starting with the areas of bright fluorescence evident in the first image, and the fluorescence change mapped over several seconds. For example, at least seven regions are discernable in Fig. 8B, and their associated time courses are given in Fig. 8D. Two pieces of evidence were used to support the enumeration of hotspots. Firstly, all hotspots should demonstrate a similar time course. If the contour was not appropriately centred, or if it covered two spots, the fluorescence change would rise more slowly or with a delay. Secondly the size of the maximal fluorescence change should be comparable for all spots. In some cells, where the contours were initially incorrectly contrived, the magnitude of the peak fluorescence exhibited ‘quantization’, so that some spots had two or three times larger peaks than the average, suggesting that they encompassed multiple sites of Ca2+ entry. Applying these procedures showed that each high frequency hair cell possessed between five and eight hotspots. As previously reported, the maximum number of spots was visible in a central section through the cell, and few extra spots appeared de novo on focusing through the cell, even though such focusing sometimes improved the sharpness of a given spot.

Measurements on cells at the two papilla locations demonstrated that the mean number of Ca2+ hotspots in high-frequency hair cells was 1.8 times that in low-frequency cells (Fig. 9B). As an alternative method of comparing cells, the total area occupied by the hotspots was calculated from the sum of the areas encompassed by the contours. These areas were normalized to the total cross-sectional area of the cell, which was similar for the two positions (154 ± 16 μm2 in four low-frequency cells and 151 ± 14 μm2 in six high-frequency cells). This method of analysis avoided the difficulty in hotspot counting of distinguishing between closely spaced spots, but confirmed that twice the cell area was occupied by hotspots in high-frequency compared to low-frequency cells (Fig. 9C). The fluorescence hotspots require Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent channels (Tucker & Fettiplace, 1995). The imaging results therefore suggest that Ca2+ channels are distributed over twice the membrane area in high-frequency cells compared to low-frequency cells. Since cells at the high-frequency location possess 2.4 times the number of Ca2+ channels, these results are consistent with Ca2+ channels being present at a constant density irrespective of location.

Figure 9. Comparison of Ca2+ hotspots in high-frequency and low-frequency hair cells.

A, examples of hotspots of Ca2+ elevation in a high-frequency hair cell (left) and a low-frequency hair cell (right). Each image was acquired at the end of a 200 ms depolarization to -20 mV, and has had the background prior to the stimulus subtracted. B, numbers (left) and relative areas (right) of hotspots in low-frequency and high-frequency cells. Bars represent the mean ± 1 s.e.m of measurements on four low-frequency and six high-frequency cells. For each cell, contours were drawn around every hotspot visible at the end of a 200 ms depolarization to -20 mV. The criteria for constructing the contours are described in the text, the same criteria being applied to cells at both locations. The number of spots was counted and the total area enclosed by the contours was summed and normalized to the cell's total area in the image. The total area was 154 ± 16 μm2 in the low-frequency cells and 151 ± 14 μm2 in the high-frequency cells. Note that there are 1.8 times as many hotspots in high-frequency cells and the hotspots occupy approximately twice the area as low-frequency cells.

DISCUSSION

The endogenous buffer

By recording in the intact papilla, we have been able to compare the properties of hair cells at two specific locations tuned to approximately 100 and 300 Hz. We have provided evidence about Ca2+ entry, buffering and action at one target, the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel BKCa, in the soma of auditory hair cells. All aspects of this pathway were found to vary with the cochlear location of the hair cell, and hence the frequency to which it was tuned. The concentration of mobile endogenous calcium buffer in the hair cell soma was estimated as 0.21 mM BAPTA at the low-frequency location, and 0.46 mM BAPTA at the high frequency location (means of the values in Fig. 4 and 6). These values are in good agreement with estimates of buffer in the hair bundle of 0.1 mM BAPTA at the same low-frequency position and 0.4 mM BAPTA at the high-frequency location (Ricci et al. 1998). Taken together the results suggest that the calcium buffer has a uniform concentration throughout the cell, and that this concentration increases along the cochlea's tonotopic axis. The variation in buffer concentration is consistent with the gradient in the expression of calbindin-28k, a likely candidate for the endogenous buffer (Navaratnam et al. 1995), found in the chick cochlea. A larger value of 0.9 mM BAPTA for the endogenous buffer was previously measured in isolated turtle hair cells using the small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK) channel as the Ca2+ sensor (Tucker & Fettiplace, 1996). The cochlear origin of those cells was unknown, but their properties, including size of Ca2+ current, suggest they were tuned to high frequencies. Roberts (1993) estimated the native calcium buffer in isolated frog saccular hair cells to be in excess of 1 mM BAPTA, though he also did not distinguish the epithelial location or frequency specificity of the cells.

Ca2+ and BKCa channel interactions

Both the insensitivity of the BKCa channel activation to BAPTA (Fig. 4) and the lack of accumulation of Ca2+ near the BKCa channel (Fig. 5) argue for the BKCa channels being in close proximity to the Ca2+ channels. At least 10 mM BAPTA was required to alter significantly the activation range of the BKCa channel. Since the voltage-activation curve for the channel was independent of pulse duration, the BAPTA effect must approximate the steady-state condition. Naraghi & Neher (1997) have estimated that, for a steady-state Ca2+ gradient, 2 mM BAPTA would have a space constant of 28 nm, indicative of its buffering range near a Ca2+ source. For 10 mM BAPTA, the space constant would be roughly halved. Thus it is likely that each Ca2+ channel influences only its immediate neighbouring BKCa channels. Since the Ca2+ and BKCa channels maintain a constant stoichiometry in cells tuned across the spectrum, (Art et al. 1993), it is conceivable that the two channel types are assembled into a single complex in the membrane. The proximity of the Ca2+ channel to its target ensures that the rate of BKCa channel activation is limited solely by intrinsic channel kinetics and not by Ca2+ diffusion.

There was a difference of 4 mV between the half-activation voltage (V1/2) for the BKCa channels at the low- and high frequency locations and at least part of this difference may be due to the lower Ca2+ sensitivity of BKCa channels at the high-frequency location (Fig. 7). Assuming that the Ca2+ current activation increases e-fold in 6.7 mV (Art & Fettiplace, 1987), the fraction of the total Ca2+ current required to half-activate the BKCa channels in high-frequency cells is 1.8(= exp(4/6.7)) that in low-frequency cells. This is close to the ratio of the Ca2+ sensitivities of the BKCa channels in detached patches, which was 1.78(= 10.3/5.8). After correction for the 4 mV difference, the V½ values at the two locations (Fig. 4C) possess an identical dependence on BAPTA concentration. Such a result would be expected if each BKCa channel is influenced by the same number of Ca2+ channels in cells at both cochlear locations.

Structure of the Ca2+ microdomains

Hair cells tuned to the higher frequency had approximately twice the number of Ca2+ channels and also twice the number of Ca2+ entry zones or ‘hotspots’. The number of hotspots is less than the number of sites of transmitter release in turtle hair cells (at least 17; Sneary, 1988). It is possible that the number of ‘hotspots’ was underestimated due to the limited temporal resolution of the imaging experiments causing neighbouring Ca2+ microdomains to fuse. However, the area of the hotspots also differed by the same 2-fold ratio between the two locations. This suggests that the Ca2+ channels that cluster to form the hotspots are present at a constant density in both high-frequency and low-frequency cells. An increase in the number of channels per cell is then accomplished by addition of clusters at constant channel density.

If the Ca2+ and BKCa channels are aggregated at synaptic release sites (Roberts et al. 1990; Issa & Hudspeth, 1994), changes in intracellular Ca2+ by influx through Ca2+ channels will regulate exocytosis as well as BKCa channel activation. Similar elevations in Ca2+ may be required to control the two processes, both of which must be fast and continuously graded from the resting potential near -50 mV, to -20 mV. The need for multiple clusters of Ca2+ channels is most likely linked to their role in exocytosis. The maximum size of each cluster may then be constrained by the area of membrane adjacent to the synaptic body, allowing the release site to be rapidly replenished with vesicles. The synaptic body in frog hair cells has a mean diameter of about 0.5 μm (Lenzi et al. 1999). An increase in the hair cell's complement of Ca2+ channels may therefore serve a dual role in signalling. In conjunction with changes in the BKCa channels, it will augment the electrical resonant frequency. The increased number of release sites may also enhance the temporal fidelity of synaptic transmission by allowing the release sites to be used asynchronously, one site being refilled while another discharges.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by NIH grants RO1 DC01362 to R.F. and RO1-DC03896 to A.J.R. and a Deafness Research Foundation grant to A.J.R.

References

- Art JJ, Fettiplace R. Variation of membrane properties in hair cells isolated from the turtle cochlea. The Journal of Physiology. 1987;385:207–242. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Art JJ, Fettiplace R, Wu Y-C. The effects of low calcium on the voltage-dependent conductances involved in tuning of turtle hair cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;470:109–123. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Art JJ, Wu Y-C, Fettiplace R. The calcium-activated potassium channels of turtle hair cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1995;105:49–72. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. The frequency selectivity of auditory nerve fibres and hair cells in the cochlea of the turtle. The Journal of Physiology. 1980;306:79–125. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. An electrical tuning mechanism in turtle cochlear hair cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1981;312:377–412. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MB, Art JJ. Variations in the ensemble of potassium currents underlying resonance in turtle hair cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:395–412. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JD, Betarbet S, Jaramillo F. Endogenous buffers limit spread of free calcium in hair cells. Biophysical Journal. 1997;73:1243–1252. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78157-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn R, Marty A. Muscarinic activation of ionic currents measured with a new whole-cell recording method. Journal of General Physiology. 1988;92:145–159. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa N, Hudspeth AJ. Clustering of Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ -activated K+ channels at fluorescently-labeled presynaptic active zones of hair cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:7578–7582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EMC, Gray-Keller M, Fettiplace R. The role of Ca2+-activated K+ channel splice variants in the tonotopic organization of the turtle cochlea. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;518:653–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0653p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi D, Runyeon JW, Crum J, Ellisman MH, Roberts WM. Synaptic vesicle populations in saccular hair cells reconstructed by electron tomography. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:119–132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00119.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Dunst C, Michaels RL, Fuchs PA. Release sites and calcium channels in hair cells of the chick's cochlea. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:9133–9144. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09133.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naraghi M. T-jump study of calcium binding kinetics of calcium chelators. Cell Calcium. 1997;22:255–268. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naraghi M, Neher E. Linearized buffered Ca2+ diffusion in microdomains and its implications for calculations of [Ca2+] at the mouth of a calcium channel. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:6961–6973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-06961.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaratnam DS, Escobar L, Covarrubias M, Oberholtzer JC. Permeation properties and differential expression across the auditory receptor epithelium of an inward rectifier Ca2+ channel cloned from the chick inner ear. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:19238–19245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons TD, Lenzi D, Almers W, Roberts WM. Calcium-triggered exocytosis and endocytosis in an isolated presynaptic cell: capacitance measurements in saccular hair cells. Neuron. 1994;13:875–883. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci AJ, Fettiplace R. The effects of calcium buffering and cyclic AMP on mechano-electrical transduction in turtle auditory hair cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;501:111–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.111bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci AJ, Wu Y-C, Fettiplace R. The endogenous Ca2+ buffer and the time course of transducer adaptation in auditory hair cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:8261–8277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08261.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WM. Spatial calcium buffering in saccular hair cells. Nature. 1993;363:74–76. doi: 10.1038/363074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WM. Localization of calcium signals by a mobile calcium buffer in frog saccular hair cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:3246–3262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03246.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WM, Jacobs RA, Hudspeth AJ. Colocalization of ion channels involved in frequency selectivity and synaptic transmission at presynaptic active zones of hair cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:3664–3684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03664.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneary M. Auditory receptor of the red-eared turtle: II. Afferent and efferent synapses and innervation patterns. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1988;276:588–606. doi: 10.1002/cne.902760411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern MD. Buffering of calcium in the vicinity of a channel pore. Cell Calcium. 1992;13:183–192. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(92)90046-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker T, Fettiplace R. Confocal imaging of calcium microdomains and calcium extrusion in turtle hair cells. Neuron. 1995;15:1323–1335. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker T, Fettiplace R. Monitoring calcium in turtle hair cells with a calcium-activated potassium channel. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:613–626. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y-C, Art JJ, Goodman MB, Fettiplace R. A kinetic description of the calcium-activated potassium channel and its application to electrical tuning of hair cells. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 1995;63:131–158. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(95)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y-C, Fettiplace R. A developmental model for generating frequency maps in the reptilian and avian cochleas. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:2557–2570. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79827-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Neher E. Mobile and immobile calcium buffers in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. The Journal of Physiology. 1993;469:245–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]