Abstract

Focal and global Ca2+ releases were monitored in voltage-clamped control and hypertrophied calsequestrin (CSQ)-overexpressing mouse cardiomyocytes, dialysed with fluo-3, using rapid (120–240 frames s−1) two-dimensional confocal imaging.

Spontaneous focal Ca2+ releases (Ca2+ sparks) were absent or significantly reduced in frequency in hypertrophied myocytes of CSQ-overexpressing mice compared to their age-matched controls. Sporadic Ca2+ sparks seen in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes had intensities and durations similar to those of controls although quantitative analysis showed a trend towards more diffuse focal releases.

Activation of Ca2+ current (ICa) failed to produce the typical sarcomeric Ca2+ striping pattern consistently seen in control myocytes. Instead, focal Ca2+ releases appeared as a disorganized patchwork of diffuse or ‘woolly’ fluorescence signals, resulting in slowly developing and reduced global Ca2+ transients.

Although the density of ICa in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes was only slightly smaller than that of controls, the inactivation kinetics of the current were greatly reduced, consistent with the much smaller rate of rise of cytosolic Ca2+.

Enhancement of ICa by elevation of [Ca2+]o from 2 to 10 mM or addition of 3 μM isoproterenol (isoprenaline) failed to normalize the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks at rest or the pattern and the magnitude of ICa-gated Ca2+ transients. Isoproterenol was somewhat more effective than elevation of [Ca2+]o.

In sharp contrast, low (0·5 mM) caffeine concentrations that produced no measurable effects on ICa or Ca2+ transients in control myocytes, re-established spontaneous focal Ca2+ releases in CSQ-overexpressing cells, triggered large ICa-gated cellular Ca2+ transients, and strongly enhanced the kinetics of inactivation of ICa.

Our data suggest that impaired Ca2+ signalling in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes results from reduced co-ordination and decreased frequency of Ca2+ sparks. The impaired Ca2+ signalling could not be restored by procedures that increased ICa, but was mostly restored in the presence of caffeine, which may alter the Ca2+ sensitivity of the ryanodine receptor.

In cardiac muscle the influx of Ca2+ through the Ca2+ channel is critical in triggering Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). The released Ca2+ in turn inactivates the L-type Ca2+ channel by interacting with the ‘Ca2+ sensing’ domains of the C-terminal tail (Soldatov et al. 1998) expressing calmodulin-binding properties (Zühlke et al. 1999; Peterson et al. 1999; Qin et al. 1999). Ca2+ mediated cross-signalling between the Ca2+ channel and ryanodine receptor (RyR) allows for tight functional coupling between these proteins, such that the influx of Ca2+ through the Ca2+ channel activates Ca2+ release from the RyR and the released Ca2+ in turn inactivates the Ca2+ channel, thereby inhibiting the release process (Sham et al. 1995). Quantitative analysis of the contribution of the released Ca2+ to the inactivation of the Ca2+ channel suggests that about 70 % of Ca2+ channel inactivation is determined by the Ca2+ released via the ryanodine receptor (Adachi-Akahane et al. 1996).

In the cardiac Ca2+ signalling cascade, the Ca2+ storage capacity of SR and the extent to which Ca2+ can be released from the low affinity (Kd≈ 1 mM) Ca2+ binding protein calsequestrin (CSQ) (MacLennan & Wong, 1971; Ikemoto et al. 1989) may also play a critical role in the release process (Kawasaki & Kasai, 1994). The structural properties of CSQ and its localization within the lumen of the SR suggest that this protein may interact with the RyR via the junctional proteins junctin and triadin (Jones, et al. 1995; Guo et al. 1996; Zhang et al. 1997). Recently we reported that mouse hearts overexpressing canine CSQ hypertrophied by 50–100 % and developed heart failure (Jones et al. 1998). Isolated myocytes from such hearts were 50–100 % larger and had significant electrophysiological and electromechanical alterations (Knollmann et al. 1998b). The most prominent features of electrical remodelling of these CSQ-overexpressing hearts were prolongation of the action potential and Q-T interval, downregulation of the transient outward K+ current (Ito), and greatly slowed kinetics of inactivation of ICa (Jones et al. 1998; Knollmann et al. 1998b). Since ICa-gated Ca2+ release was impaired in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes despite the presence of 10- to 15-fold larger caffeine-releasable Ca2+ pools (Jones et al. 1998), we suggested that impaired Ca2+ release was mostly responsible for the marked slowing of the inactivation kinetics of ICa. In a subsequent report on another strain of transgenic mice overexpressing murine calsequestrin, similar hypertrophy and slowing of the kinetics of ICa were described, but the extent of impairment of ICa-gated Ca2+ release was not quantified (Sato et al. 1998).

In the present report we have quantified the properties of focal and global Ca2+ release in this model and have studied the nature of impaired Ca2+ signalling in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes by interventions that modify the Ca2+ channel or the Ca2+ sensitivity of the RyR. We find that agents that enhance Ca2+ current are less effective in re-establishing normal Ca2+ signalling than those that sensitize the Ca2+ release channel. A preliminary report of this work has already appeared (Wang & Morad, 1999).

METHODS

Transgenic mice and cell isolation

Mice expressing 10- to 15-fold higher levels of cardiac calsequestrin, aged 9–21 weeks, and showing significant cardiac hypertrophy were used in this study (Jones et al. 1998). Single ventricular myocytes were enzymatically isolated using a modification of a previously described collagenase-protease technique (Mitra & Morad, 1985). Briefly, mice were deeply anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1, i.p.), the chest cavity was opened and hearts were excised, resulting in exsanguination. Experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional and NIH established guidelines. The excised hearts were placed in ice-cold incubation solution of the following composition (mM): 30 taurine, 90 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 10 Hepes, 10 glucose and 1 MgCl2, titrated to pH 7.2 with NaOH. The aorta was cannulated and perfused for 5 min with an oxygenated incubation solution at 36°C containing 0.5 mM EGTA. The solution was then switched to an isolation solution containing 1 mg ml−1 albumin (Sigma Chemical Co.), 0.12 mg ml−1 protease (Type XIV, Sigma Chemical Co.) and 0.33 mg ml−1 collagenase (Type IV, 204 U mg−1, Worthington Biochemical Corp.) for 8 min. The heart was then removed and the ventricle minced and digested for an additional one to three digestion periods (5-10 min each) in a shaking water bath at 37°C. The resulting cell suspensions were collected after each digestion and stored at room temperature in an incubation solution containing an additional 0.2 mM CaCl2. This procedure yielded 30–40 % rod-shaped myocytes that were used for up to 10 h.

Electrophysiological measurements

Myocytes were whole-cell clamped (Hamill et al. 1981) using borosilicate glass capillaries (resistance 2–3 MΩ) filled with an internal Cs+-rich solution (see below) containing 1 mM EGTA and 1 mM fluo-3. The cell capacitance was measured using previously established protocols (Cleemann & Morad, 1991). Currents were neither leak nor capacitance substracted (to obtain high quality data and to control for myocyte viability), but were series resistance compensated. Since imaging of the myocytes with a two-dimensional laser scanner required 10–15 min of dye dialysis, only cells with low leak current and clear striations were included in the final analysis of the results. All myocytes were clamped at a holding potential (Vh) of -70 mV prior to application of test pulses. Ca2+ currents were activated with test depolarizations to 0 mV either from -70 mV or more rarely from -50 mV to further suppress the residual TTX-resistant Na+ current.

Two-dimensional confocal Ca2+ imaging

Ca2+ currents and 2-D Ca2+ images of a whole-cell-clamped myocyte were simultaneously monitored in cells dialysed with 1 mM fluo-3 and 1 mM EGTA. This concentration of dye in combination with EGTA was chosen to limit the diffusion distance of Ca2+ and Ca2+-dye complex to about 50 nm (Adachi-Akahane et al. 1996; Cleemann et al. 1998). The combined use of fluorescent and non-fluorescent Ca2+ buffers and a confocal apparatus capable of rapidly scanning the cellular image via an accousto-optically steered laser beam (Noran, Odyssey, Madison, WI, USA) made it possible to obtain high resolution images of the rise and fall of cytosolic Ca2+ at high spatial and temporal resolution: ∼0.5 μm and 120–240 frames s−1 (Cleemann et al. 1998). Briefly, the confocal apparatus was mounted on an inverted microscope (Zeiss, Axiovert 135 TV) with a water immersion objective lens (Zeiss, C-apochromat, ×40, NA 1.2). The 488 nm excitation beam was generated from an argon ion laser (Omnichrome, Chino, CA, USA). The confocal slit in the rapidly scanned direction was set at 50 μm (0.8 μm in the focal plane), and the fluorescent light emitted was measured with a high efficiency photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu, Middlesex, NJ, USA). The data were acquired by a Silicon Graphics workstation computer (Indy, Unix operating system, Noran Instruments, Middleton, WI, USA) and stored temporarily in 100 Mbyte random access memory before being transferred to hard disk.

Fluorescence measurements were initiated 6–8 min after rupture of the membrane under the patch pipette. After this period of dialysis, the intracellular fluo-3 concentration was typically close to its equilibrium near the patch electrode, but continued to exhibit slight gradients towards the ends of the cell (Cleemann et al. 1997). Static images of Ca2+-dependent fluorescence show the average fluorescence intensity (F0) calculated from several frames (Figs 1A and B (arrows) and 7A (arrows) and B). Dynamic Ca2+ signals were illustrated by sequences of frames showing the change in fluorescence (ΔF) relative to the average fluorescence (F0) measured either in the presence of scattered focal Ca2+ releases (Figs 1 and 7), or immediately before and after Ca2+ releases activated by ICa (Figs 4A and B and 5A and B). This method of normalization was used to show Ca2 sparks as clearly as possible without resorting to the use of contrast enhancement. In another approach (Figs 3A and B, 6A and B and 8A and B) we relied, in part, on a colour scale to present total fluorescence (F) with a large dynamic range. Tracings of cellular Ca2+ transients are shown as the average fluorescence of each frame normalized relative to the average resting fluorescence (F/F0) prior to the ionic or pharmacological interventions (Figs 3F and G, 4E, 5E, 6E and F, and 8E). This type of normalization was used to permit comparison of results from different cells, and allow detection of systematic changes in both cellular transients (ΔF) and resting fluorescence (Fr) during the experiment (Figs 4F, 5F and 8F). Focal Ca2+ releases were identified, and followed in time, using a computerized algorithm (Figs 2 and 7). This algorithm (Cleemann et al. 1998) identified local fluorescence maxima by means of a centre-minus-surround detection kernel (inset in Fig. 2), which consists of pixels (0.207 μm spacing) approximating a central positively weighted disc (radius 0.8 μm) and a concentric negatively weighted ring (radius 1–1.5 μm). A new computer algorithm was developed in Visual Basic (Microsoft) to remove constraints of the previous program and allow routine measurements of the amplitude and size of Ca2+ sparks by fitting a Gaussian distribution to the local fluorescence intensity (Fig. 1C).

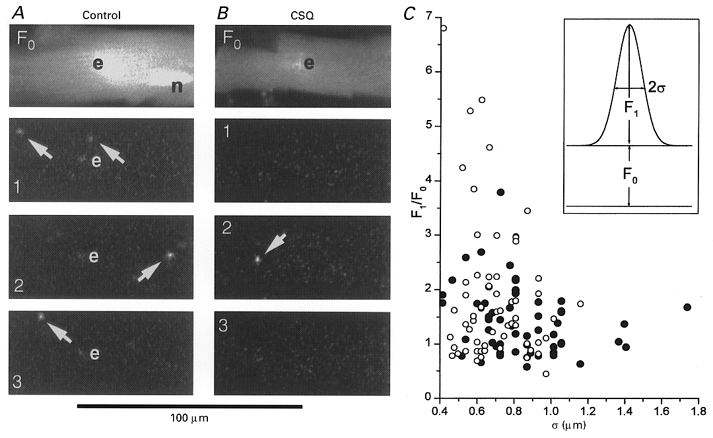

Figure 1. Spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in control (panel A) and CSQ-overexpressing (panel B) mouse cardiomyocytes and comparison of their size and magnitude (panel C).

The top images of two cardiomyocytes in panels A and B show the average fluorescence intensity (F0) obtained from 60 frames recorded at 30 Hz in cells voltage clamped at a holding potential of -70 mV. In recordings obtained from 4 to 6 min after rupture of the patch, the fluorescence intensity is still highest near the dialysing patch electrode (e) suggesting that that the Ca2+-sensitive dye (1 mM fluo-3 with 1 mM EGTA as an adjuvant) has not equilibrated fully in the longitudinal direction and/or that the dye in the pipette is partially detected even though it is outside the confocal plane. Nuclear regions (n) and faint longitudinal lines suggestive of fibrils are often seen. The lower images (1, 2 and 3) show three consecutive frames recorded at 33 ms interval in the two cells. The frames show the change in fluorescence (ΔF) so that the outline of the cell and the position of the electrode are seen only as changes in the intensity of the noise. Panel A shows the typical presence in control cells of one or more Ca2+ sparks in each frame. Panel B shows one of the rare Ca2+ sparks (arrow) in CSQ-overexpressing cells. Notice that the Ca2+ sparks are brief so that at 30 Hz they are seen clearly only in single frames and have, at most, a faint afterglow in the following frame (panel B, arrows). Panel C shows a scattergram with regression lines of the normalized intensity (F1/F0) and dimension (σ) of Ca2+ sparks in control (^) or CSQ-overexpressing (•) cells. The fluorescence intensity of each Ca2+ spark was fitted by least-squares approximation by a Gaussian distribution (F1exp(-[(x–x0)2+ (y–y0)2]/2σ2)) characterized by its centre (x0, y0), its standard deviation (σ, see inset) and the central increase in fluorescence (F1) measured relative to the resting fluorescence (F0).

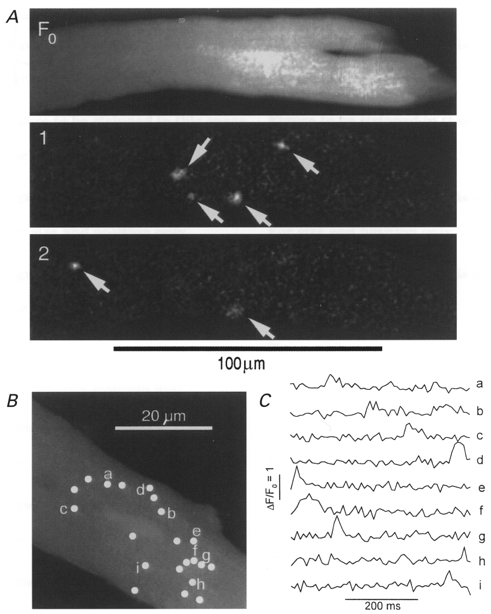

Figure 7. A low concentration of caffeine (0.5 mM) causes spontaneous Ca2+ spark activity in CSQ-overexpressing mouse cardiomyocytes.

Panel A shows recordings in a layout similar to Fig. 1. Upper image, average fluorescence intensity (F0). Lower images (1 and 2), sequential frames showing transient fluorescence changes (ΔF). Panel B shows the distribution and panel C the time course of Ca2+ sparks in a single cell exposed to 0.5 mM caffeine. The sample traces and their locations are labelled a-i.

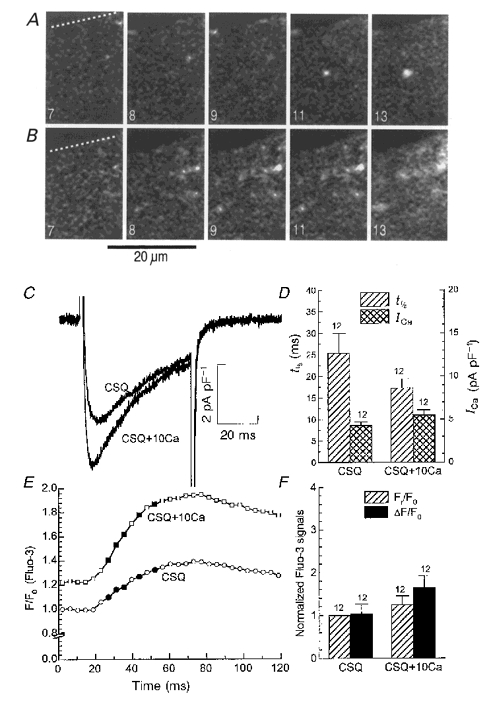

Figure 4. Effect of increased extracellular calcium concentrations on ICa-gated Ca2+ release in CSQ-overexpressing cells.

Panels A and B show representative sample frames from stacks of fluorescence images (ΔF) recorded at 240 Hz during voltage-clamp depolarization from -70 to 0 mV with normal (2 mM, panel A) and elevated (10 mM, panel B) extracellular Ca2+ concentrations. Notice that elevation of [Ca2+]o increased the number of Ca2+ sparks but did not change their appearance. The numbered sample frames (7, 8, 9, 11, 13 corresponding to filled symbols in panel E) show the increase in fluorescence (ΔF) after subtraction of the average background fluorescence. Panels C and E show, respectively, ICa and the cellular fluorescence signal in CSQ-overexpressing cardiomyocytes with 2 mM (CSQ) and 10 mM (CSQ+10Ca) [Ca2+]o. The fluorescence signals (F) in panel E were normalized relative to the resting cellular fluorescence (F0) measured with 2 mM [Ca2+]o. Panel D shows average values of the amplitude of the current (ICa, right axis, ) and its half-time of inactivation (t1/2, left axis,

) and its half-time of inactivation (t1/2, left axis, ) recorded with 2 mM (CSQ) and 10 mM (CSQ+10Ca) [Ca2+]o. Similarly, panel F shows the effect of elevated [Ca2+]o on the average values of the resting (Fr,

) recorded with 2 mM (CSQ) and 10 mM (CSQ+10Ca) [Ca2+]o. Similarly, panel F shows the effect of elevated [Ca2+]o on the average values of the resting (Fr, ) and transient (ΔF, ▪) cellular fluorescence signals normalized relative to the resting fluorescence (F0) measured with 2 mM Ca2+. The numbers (12) next to the error bars indicate the number of cells examined.

) and transient (ΔF, ▪) cellular fluorescence signals normalized relative to the resting fluorescence (F0) measured with 2 mM Ca2+. The numbers (12) next to the error bars indicate the number of cells examined.

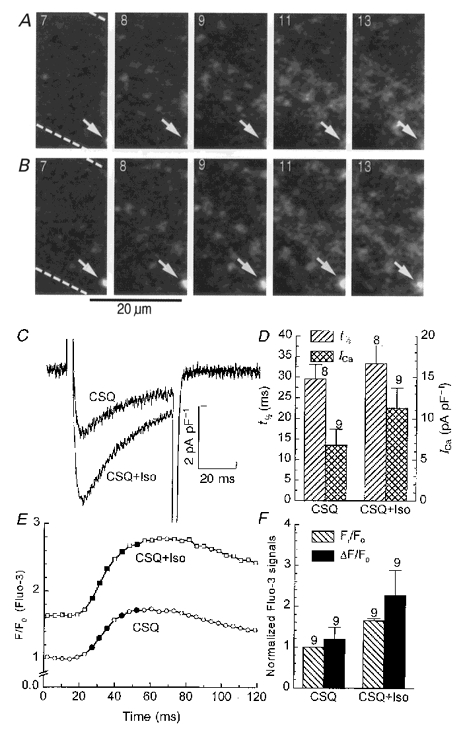

Figure 5. Effect of isoproterenol on ICa-gated Ca2+ release in transgenic cells.

The layout of this figure is identical to that of Fig. 4. After the initial recording (CSQ), the transgenic cells were exposed to 3 μM isoproterenol for 1 min before testing the drug effect (CSQ+Iso). Panel A, sample frames before isoproterenol. Panel B, sample frames in the presence of isoproterenol. Arrows indicate the location of long lasting releases at a site that is barely visible in panel A, but in clearer view in panel B after some cell shortening. Panel C, membrane currents. Panel D, effect of isoproterenol on ensemble averages of half-time and amplitude of ICa. Panel E, Ca2+ transients. Panel F, effect of isoproterenol on ensemble averages of resting and transient fluorescence signals.

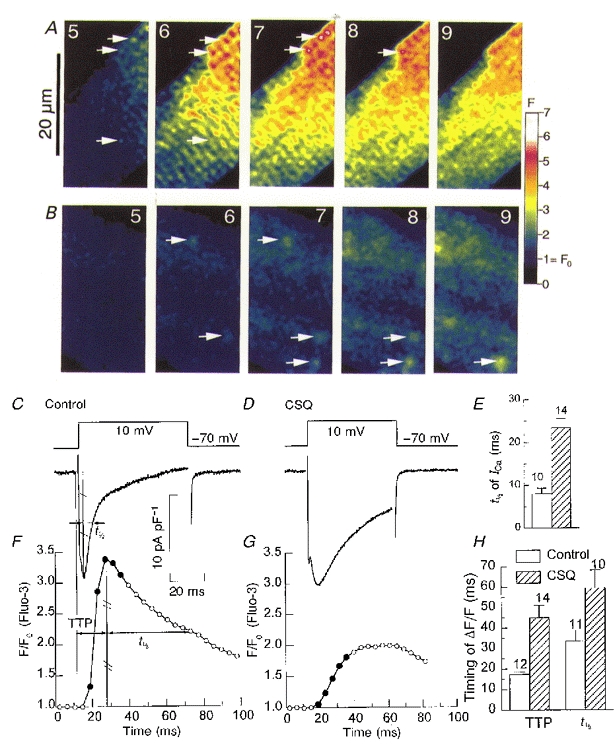

Figure 3. Comparison of ICa-induced Ca2+ release in voltage-clamped control (A, C and F) and transgenic (B, D and G) ventricular mouse cardiomyocytes.

Panels A and B show numbered sample frames of total fluorescence (F) recorded at 240 Hz at the times indicated by filled symbols in the tracings of the cellular Ca2+ transients (panels F and G). Arrows identify some Ca2+ sparks that can be followed from frame to frame. The colour scale provides a calibration of the fluorescence intensity (F) relative to the resting fluorescence (F0= 1). Panels C and D illustrate the voltage-clamp protocol and the time course of the Ca2+ current. The bar charts compare the time course of the Ca2+ current (panel E) and the Ca2+ signal (panel H) in control (□) and CSQ-overexpressing ( ) cells. The Ca2+ current is characterized by its half-time of inactivation (t1/2, see panel C) while the Ca2+ signal is described by both its time-to-peak (TTP, see panel F) and its half-time of decay (t1/2). The error bars indicate the standard error of the mean and adjacent numbers indicate the number of cells examined.

) cells. The Ca2+ current is characterized by its half-time of inactivation (t1/2, see panel C) while the Ca2+ signal is described by both its time-to-peak (TTP, see panel F) and its half-time of decay (t1/2). The error bars indicate the standard error of the mean and adjacent numbers indicate the number of cells examined.

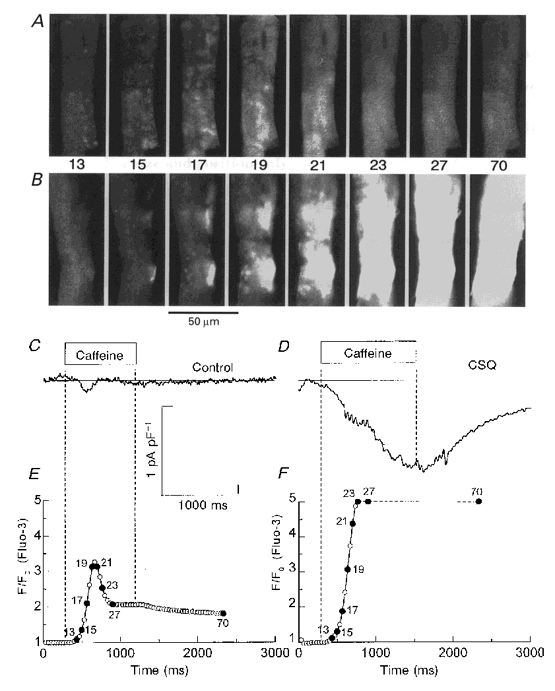

Figure 6. Caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in control (panels A, C and E) and transgenic (panels B, D and F) cardiomyocytes.

The numbered sample frames from a control cell (panel A) and a transgenic cell (panel B) were recorded as total fluorescence (F) at 30 Hz at the times indicated by filled and numbered symbols in the fluorescence tracings (F/F0) of panels E and F. The timing of the exposure to 10 mM caffeine is indicated by vertical dashed lines and the labelled bars (Caffeine) in panels C and D, which also show the time course of the Na+-Ca2+ exchange current. Notice that frames 23 and 27 in panel B were recorded at a time when the inward Na+-Ca2+ exchange current continued to increase, but the Ca2 + signal could no longer be followed because the fluorescence detector was in saturation (horizontal dashed line in panel F) and the Ca2+ waves were invading the ends of the cell outside the detection area.

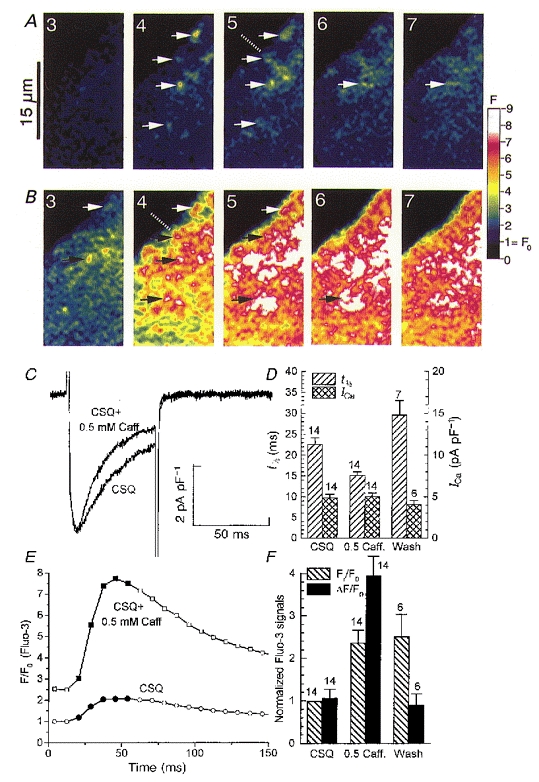

Figure 8. Caffeine in low concentrations strongly enhances the ICa-gated Ca2+ release in CSQ-overexpressing mouse cardiomyocytes.

The sample frames of total fluorescence (F) were recorded at 120 Hz before (CSQ, panel A) and during (CSQ + 0.5 mM Caff, panel B) exposure to 0.5 mM caffeine during activation of ICa (panel C) at the times indicated by filled symbols in the tracings of the cellular fluorescence signals (panel E). Arrows in panels A and B show locations of prominent Ca2+ release sites; the dashed lines supposedly indicate alignment of release sites along a z-line; and the colour scale provides the means of calibration. In addition to the caffeine effect (0.5 mM Caff.) the ensemble averages in the bar graphs (panels D and F) also show the effect of washout (Wash).

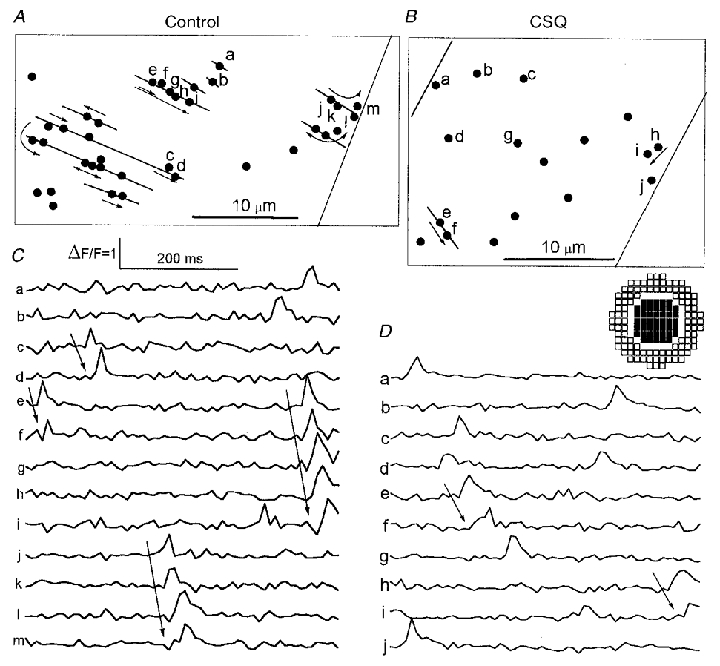

Figure 2. Time course and distribution of Ca2+ sparks in a control cell (panels A and C) and a CSQ-overexpressing cell (panels B and D).

Panels A and B show the location of all Ca2+ sparks (•) recorded in 60 frames at 120 Hz over a period of 500 ms in relation to the edges of the cell (nearly vertical lines) and the probable location of z-lines (panel A, nearly horizontal lines). Panels C and D illustrate the time course of Ca2+ sparks plotted as ΔF/F0, where ΔF is measured with a centre-minus-surround kernel (inset between panels B and D; see Methods), and F0 is the average fluorescence intensity in the analysed area. In these abnormally active cells, what might appear as very intense, long lasting Ca2+ sparks could often be resolved as composites of several smaller Ca2+ sparks that were propagating primarily in the direction of the z-lines (→).

Solutions and data analysis

The solution used for cellular equilibration and formation of the gigaseal contained (mM): 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, buffered to pH 7.4 with NaOH. In experimental solutions, inward K+ currents were suppressed by addition of Ba2+ (0.2 mM) and omission of extracellular K+. Na+ currents were mostly suppressed using 3–6 μM TTX, and holding potentials (Vh) of -70 to -50 mV. We used 200 μM cAMP in all experiments except those where cells were exposed to isoproterenol (3 μM). In some experiments, elevation of [Ca2+]o was achieved by adding the salt without correcting for the increase in osmolarity. Isoproterenol was used at 3 μM and caffeine at 0.5-10 mM. Patch pipettes were filled with solutions containing (mM): 110 CsCl, 20 TEA, 10 Hepes, 5 MgATP, 5 glutathione, 1 EGTA, 1 fluo-3 (Molecular Probes Inc.), with the pH adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH. All experiments were performed at room temperature (22-25°C).

Ensemble values were calculated as means ±s.e.m.

RESULTS

Transgenic mice overexpressing calsequestrin live into adulthood but develop significant cardiac dilatation and hypertrophy 30 days post partum (Knollmann et al. 1998b). Hypertrophy increases progressively with age, leading to heart failure. Isolated CSQ-overexpressing ventricular myocytes are also enlarged (∼2-fold larger membrane capacitance; Jones et al. 1998) and have longer action potentials with significant downregulation of K+ channels (Ito and IK1; Knollmann et al. 1998a,b).

Spontaneous focal Ca2+ releases (Ca2+ sparks)

Figure 1 shows examples of two-dimensional confocal images of spontaneously occurring Ca2+ sparks in myocytes obtained from the hearts of CSQ-overexpressing mice (panel B) and their non-transgenic littermate (panel A). The two top images (F0) show the average fluorescence intensity measured with the Ca2+ indicator dye fluo-3. The outline of each cell and the position of the whole-cell patch-clamp electrode (e) are clearly visible while the fading of the fluorescence signal towards the ends of the cells suggests that, following 6 min of dialysis, longitudinal equilibration of the cell with fluo-3 is still incomplete (see Cleemann et al. 1997). In Fig. 1A and B the lower three images (1, 2 and 3) are sequential frames at 30 Hz measured differentially as the increase in fluorescence (ΔF) relative to the average fluorescence (F0). Consequently the outline of the cell and the position of the electrode are seen only as variations in the noise. On the other hand, the differential measurement aids the visual detection of Ca2+ sparks over the entire cell, including its edges. In control cells, spontaneous focal Ca2+ releases were almost always detected in normal Tyrode solution (2 mM [Ca2+]o, Vh=−70 mV), appeared well defined (0.8-2.4 μm in diameter corresponding to 2σ in panel C), and occurred randomly in different regions of the cells, typically at a rate of 1–2 per frame recorded at 30 Hz, covering the major part of the cell. In sharp contrast, spontaneously occurring Ca2+ sparks were absent in almost all transgenic myocytes, and in rare exceptions (7 out of 49 cells monitored for 1–2 s) they were generally seen only in a few singular frames (e.g. Fig. 1B).

Recordings at 30 frames s−1 were used to survey the major part of a cell typically for 2 s. In such records, each Ca2+ spark was seen clearly only in a single frame, and appeared, at best, as a much fainter diffuse fluorescence in the next frame consistent with a spark duration of less than 33 ms. These images were analysed by approximating individual Ca2+ sparks in single frames by a Gaussian distribution (inset of panel C) characterized by its normalized amplitude (F1/F0) and standard deviation (σ). Panel C compares the parameters of the sporadic spontaneous Ca2+ sparks measured in CSQ-overexpressing cells (•) to a randomly selected subset of the more numerous events in control cells (^). In terms of photons, the overall intensity of Ca2+ sparks (evaluated as the average of σ2F1/F0) was the same in control (0.91 ± 0.08 μm2, n = 60 sparks) and CSQ-overexpressing cells (1.04 ± 0.10 μm2, n = 55 sparks). Notice, however, that smaller (σ= 0.4-0.8 μm) but very bright (F1/F0= 3-7) Ca2+ sparks were only found in control cells (^) while very large sparks (σ > 1.2 μm) of lower intensity (F1/F0 < 2) appeared to be a characteristic of CSQ-overexpressing cells (•). This difference is based on a small number of observations, but it raises the possibility that Ca2+ sparks in CSQ-overexpressing cells tend to: (a) spread by diffusion during sustained Ca2+ release from a single site, (b) spread by Ca2+-induced Ca2+ releases from a primary release site to some neighbouring sites, or (c) originate from more poorly defined or deformed diadic junctions (for ultrastructural deformity, see Jones et al. 1998).

To compare the time course of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in control and CSQ-overexpressing myocytes the imaging speed was increased to 120 or 240 Hz, which reduced the scanned region (Fig. 2). In such experiments we were forced to choose the rare CSQ-overexpressing myocytes that produced a larger number of spontaneous diadic Ca2+ releases. Considering the variability in ultrastructural and electrophysiological properties of myocytes from CSQ-overexpressing hearts, we accepted the possibility that the more active CSQ-overexpressing myocytes were somewhat atypical of the fully developed stages of cardiac impairment. To obtain a valid comparison we therefore used for comparison control cells that also had a relatively high incidence of Ca2+ sparks and thus ascertained that the analysed CSQ-overexpressing myocytes were obtained from hearts with established hypertrophy and exhibited the characteristic slow kinetics of inactivation of ICa and Ca2+ transients (see Fig. 3). A computerized algorithm was used to locate the Ca2+ sparks and follow their development (Cleemann et al. 1998). The spatial resolution of these measurements was determined by a detection kernel, which measured the average fluorescence intensity over a disc with 0.8 μm radius relative to a surrounding ring of 1–1.5 μm radius. The selected traces of Fig. 2 suggest that Ca2+ sparks were of similar amplitude and duration in control (panels A and C, traces a–m) and in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes (panels B and D, traces a–j). The duration of focal Ca2+ release (15-20 ms) was somewhat briefer than that observed in most other studies (Cannell et al. 1994, 1995), probably because we have used both a centre-minus-surround kernel, and 1 mM EGTA as a secondary non-fluorescent Ca2+ buffer (for detailed analysis and rationale of this approach, see Cleemann et al. 1998). The 2-D confocal measurements made it possible to distinguish isolated focal Ca2+ releases from compound releases that spread slowly in the direction of the z-lines in control cells (Fig. 2A and C, arrows) and collectively lasted longer than the spatially confined releases. Such propagated releases were also seen occasionally in CSQ-overexpressing cells (Fig. 2B and D, traces e and f and h and i), but we found no indication that this mechanism significantly enhances the overall level of spontaneously released Ca2+. The cells illustrated in Fig. 2 had unusually high levels of spontaneous Ca2+ release, but the properties of each Ca2+ spark were similar to those typically observed in less active cells. When analysis was limited to Ca2+ sparks that showed no sign of propagation, and the analysis was performed with identical settings (detection threshold, dimensions of detection kernel, Cleemann et al. 1998), the average durations of sparks in control (17.3 ± 2.8 ms, n = 4 cells) and CSQ-overexpressing myocytes (17.6 ± 2.0 ms, n = 8 cells) were comparable.

Confocal images of ICa-gated Ca2+ release

Figure 3 compares the Ca2+ current and the profiles of rise of intracellular Ca2+ in a control and CSQ-overexpressing myocyte. Two-dimensional confocal images of Ca2+ obtained at 4.17 ms intervals (240 frames s−1) shows that activation of ICa in the control myocyte leads to the development of sparks (arrows in panel A, frame 5; first filled circle in panel F) that appear as bright spots which tend to fuse into a sarcomeric Ca2+ striping pattern in later frames (Fig. 3A, frames 6 and 7; cf. Cleemann et al. 1998). This pattern of focal Ca2+ release generates rapidly activating and coordinated Ca2+ release (Fig. 3F). In CSQ-overexpressing myocytes, on the other hand, Ca2+ sparks do not develop into the characteristic sarcomeric Ca2+ stripes (Fig. 3B). Instead, large diffuse areas of Ca2+ fluorescence with embedded Ca2+ sparks (Fig. 3B, arrows) can be consistently observed during the slowly rising cytosolic Ca2+ transients (Fig. 3G). Note that the slow rise in cytosolic Ca2+ transients is accompanied by much slower inactivation of ICa (Fig. 3D), suggesting impaired Ca2+ signalling in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes (Adachi-Akahane et al. 1996; Jones et al. 1998).

The bar charts in Fig. 3 document the significance of these findings based on pooled data from a number of control and transgenic myocytes. Panel H compares the kinetics of Ca2+ transients and shows that the time-to-peak (TTP, see panel F) and the half-time (t1/2) of its decay are much longer in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes, consistent with slower rise and fall of global cytosolic Ca2+. Similarly, panel E shows that the half-time of inactivation of ICa (t1/2, see Fig. 3C) in transgenic myocytes was prolonged more than 2-fold compared to the control myocytes. It is likely that the absence of coordinated and rapid Ca2+ release in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes is mostly responsible for the slower inactivation of ICa in transgenic mice, as has been described for Ca2+ currents in rat ventricular myocytes (Adachi-Akahane et al. 1996). In this analysis the half-time, rather than exponential analysis, was used to approximate the inactivation kinetics of the channel, as relatively brief 50–60 ms pulses were used in confocal imaging experiments to limit photo-damage caused by intense laser light.

Enhancement of ICa is not sufficient to restore Ca2+ signalling

Since the degree of activation of RyRs in part depends on a rapid rise of Ca2+ in the microenvironment of the Ca2+ channel-RyR complexes, we examined whether increasing the influx of Ca2+ through the channel would restore the impaired Ca2+ signalling in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes. To ensure that the Ca2+ content of the SR remained constant when 2 or 10 mM Ca2+ was used as charge carrier through the Ca2+ channel, a sequence of five conditioning depolarizing pulses in 2 mM Ca2+ were applied prior to the rapid and short (0.5 s) application of the 10 mM Ca2+ solution. Figure 4 shows the effect of elevation of extracellular Ca2+ from 2 to 10 mM on ICa (panels C and D), global cellular Ca2+ transients (panel E and F) and focal Ca2+ releases (panels A and B). Elevation of Ca2+ enhanced ICa (panel D, 32 ± 9 %, mean ±s.e.m., n = 12), increased the cellular Ca2+ transients (ΔF/F0 in panel F, by 100 ± 9 %, mean ±s.e.m., n = 12), and decreased the half-time of inactivation of ICa (t1/2, panel D, 28 ± 7 %, mean ±s.e.m., n = 12); but the sporadic pattern of focal Ca2+ releases and their size, duration and uncoordinated nature remained unchanged.

Figure 5 shows that isoproterenol was somewhat more effective than elevation of Ca2+ in restoring the coordinated Ca2+ release, whether monitored as confocal images (frames of panels A and B) or as global intracellular Ca2+ transients (panels E and F). In the presence of isoproterenol, cytosolic Ca2+ transients were increased more than 2-fold (133 ± 35 %, n = 9) as the resting Ca2+ signal increased by 65 ± 5 % (mean ±s.e.m., n = 9, Fr/F0 in panel F). Isoproterenol did not reduce the time-to-peak of global Ca2+ transients (panel E) or accelerate the inactivation kinetics of ICa significantly (panel D), consistent with the idea that coordinated Ca2+ release was not fully re-established. The increase in the number of Ca2+ sparks detected shortly after activation of ICa (frames 7–9 of panels A and B) appeared to be roughly proportional to the increase in the cellular Ca2+ transients (panel E), and occurred without significant changes in the size of the individual Ca2+ sparks. In this context, note that strong, long lasting focal Ca2+ releases, of the type seen near the edge of the cell in the lower right corner in each frame of both panels A and B (arrows), were detected both in the absence and presence of isoproterenol, but were too rare to contribute significantly to the global Ca2+ transient.

Caffeine improves the efficacy of Ca2+ release in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes

It has been previously reported that caffeine-releasable Ca2+ stores in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes were markedly enhanced even though ICa-gated Ca2+ release was impaired (Jones et al. 1998). In the next series of experiments, we attempted to examine the effects of high and low concentrations of caffeine on direct or ICa-gated Ca2+ release in CSQ-overexpressing transgenic myocytes. Figure 6 compares the effect of a rapid and short application (‘puff’) of 10 mM caffeine in control and transgenic myocytes. In control cells dialysed with 1 mM fluo-3 and 1 mM EGTA, rapid application of 5–10 mM caffeine triggered a rapid release of Ca2+, the time course of which decayed slowly in the presence of caffeine (panel A, frames 13-70; panel E). Note that the rise in global Ca2+ concentrations activated only a brief and small Na+-Ca2+ exchange current (INa-Ca; Callewaert et al. 1989), in part because cytosolic Ca2+ is well buffered by 1 mM EGTA and 1 mM fluo-3 (panel C; see also Adachi-Akahane et al. 1996). In sharp contrast, in similarly Ca2+-buffered CSQ-overexpressing myocytes, the caffeine-induced Ca2+ release was so large as not only to activate a large INa-Ca (panel D), but also to fully saturate the fluorescent dye signal (panel F, dashed line). These findings are consistent with the global measurements of Ca2+ in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes previously reported using high concentrations of fura-2 as Ca2+ buffer (Jones et al. 1998). Confocal images recorded at 30 Hz show that the pattern of caffeine-induced Ca2+ release was noticeably different in control (panel A) and transgenic (panel B) myocytes. In control cells, local Ca2+ releases were initiated at many sites, first close to the surface of the cell (panel A, frames 13 and 15) then at its centre (frames 17-21), and were followed by a more homogeneous rise in cytosolic Ca2+ that faded rapidly (frames 23-27), except for the delayed response from the nuclear region (frames 27 and 70). In contrast, the caffeine-induced Ca2+ signal in transgenic cells was typically initiated at only a few sites near the cell surface (panel B, frames 15 and 17), and then appeared to spread as a wave with some focal releases ahead of the front to the entire cell (frames 19 and 21), saturating the detector (frames 23 and 27) and causing noticeable cell shortening (frame 70), often irreversibly. Thus, it appears that the large Ca2+ release triggered by caffeine in CSQ-overexpressing cells may activate propagating Ca2+ waves (cf. Cheng et al. 1996).

To explore the effect of caffeine on spontaneous or Ca2+ channel-gated Ca2+ release in transgenic myocytes with intact Ca2+ stores, we tested the effects of lower concentrations of caffeine (0.5 mM) on focal and global Ca2+ releases. Figure 7A (frames 1 and 2) shows the spontaneous occurrence of a number of Ca2+ sparks in a CSQ-overexpressing myocyte clamped to -70 mV following 1 min exposure to 0.5 mM caffeine (cf. Fig. 1). This effect was observed in 20 out of 24 quiescent CSQ-overexpressing myocytes. In comparison, incubation of myocytes in 1 μM isoproterenol induced spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in 9 out of 13 quiescent CSQ-overexpressing myocytes. Figure 7 also shows the distribution (panel B) and time course of development of Ca2+ sparks in solution containing 0.5 mM caffeine (panel C, traces a–i). These focal Ca2+ releases occurred for the duration of caffeine exposure (seconds to minutes), were markedly suppressed or absent upon washout of caffeine, and had intensities and durations similar to those seen in non-transgenic myocytes in the absence of caffeine (cf. Fig. 2).

Figure 8 compares ICa-gated Ca2+ transients and focal Ca2+ releases in the same transgenic myocyte in the absence and presence of 0.5 mM caffeine. Consistent with the findings of Fig. 3, depolarization of CSQ-overexpressing myocytes to 0 mV activated a slowly inactivating Ca2+ current (panel C, CSQ) which failed to release significant coordinated focal Ca2+ releases (panel A, frames 4-6) or global Ca2+ transients (panel E, CSQ). In the presence of 0.5 mM caffeine, however, global Ca2+ releases (panel E, CSQ + 0.5 mM Caff) recovered in response to activation of ICa. However, although some alignment in Ca2+ release sites was occasionally observed (dashed lines in panel A, frame 5 and panel B, frame 4), the characteristic Ca2+ striping pattern seen in control cells did not fully develop (panel B). The cellular response of CSQ-overexpressing myocytes in the presence of caffeine appeared to be composed of a large number of ‘woolly’ sparks, which were resolved most clearly shortly after depolarization or at the edges of the cells (panel B, arrows in frames 4 and 5), as they tended to fuse rapidly in the cell interior. It should be noted that the slow inactivation kinetics of ICa in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes (t1/2, panel D) were also significantly enhanced in the presence of 0.5 mM caffeine (panel C), consistent with the restoration of more effective Ca2+ release. Caffeine, however, had little or no effect on the peak magnitude of the Ca2+ current (Fig. 8D). The 3- to 4-fold enhancement of the cellular Ca2+ release induced by 0.5 mM caffeine was completely reversible (ΔF/F0, panel F) after washout of caffeine. The smaller increase in resting Ca2+ signal observed in the presence of caffeine, however, was not reversible (Fr/F0, panel F), suggesting that photoinactivation, in part, contributes to the rise in the background signal.

In a few cells, where we used 1 and 2 mM concentrations of caffeine, we found that 1.0 mM caffeine consistently increased ICa and similarly enhanced the global Ca2+ transients. Caffeine at a concentration of 2 mM or higher, on the other hand, often induced partial Ca2+ release with transient suppression and then steady-state potentiation of ICa (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The present data indicate that the impairment of Ca2+ release in myocytes overexpressing cardiac CSQ is associated with a reduced frequency of spontaneous or Ca2+ channel-gated Ca2+ sparks and the disappearance of the coordinated Ca2+ release which generates the sarcomeric Ca2+ striping pattern in non-transgenic cardiomyocytes. Effective Ca2+ signalling could be restored by low (0.5 mM) concentrations of caffeine, but not by agents that enhance ICa (isoproterenol and high [Ca2+]o), suggesting that impairment of ICa-gated Ca2+ release in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes may result from decreased Ca2+ sensitivity of the ryanodine receptors or their number in the diadic junctions.

Impaired Ca2+ release in CSQ-overexpressing transgenic myocytes

Although the caffeine-releasable Ca2+ pools in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes were enhanced (Fig. 6) 10- to 15-fold (Jones et al. 1998), the Ca2+ channel-gated Ca2+ release was small and uncoordinated (Fig. 3). We considered the possibilities that this reduction might occur because the unitary events associated with diadic Ca2+ release were either: (a) smaller in amplitude, (b) smaller in dimensions, or (c) fewer in number. To distinguish between these possibilities we studied spontaneous Ca2+ releases in control solutions and found that they occurred rarely in transgenic myocytes (Fig. 1A and B), but when they did sporadically occur, had the same magnitude as those of control cells (Fig. 1C). We cannot exclude the possibility that the release of Ca2+ in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes is distributed over a somewhat larger area (Fig. 1C), but found little evidence that this might result from the prolongation of the release process and the subsequent dispersion by diffusion. The measured duration (15-20 ms) of focal Ca2+ release in control and transgenic myocytes was somewhat longer than the value obtained by similar 2-D confocal measurements in rat ventricular myocytes (Cleemann et al. 1998), but was considerably shorter than line-scan estimates of the duration of Ca2+ sparks (Cheng et al. 1993; Cannell et al. 1994, 1995; Lopez-Lopez et al. 1995). It remains to be determined if this is due to differences in technique (target size (inset of Fig. 2), use of Ca2+ buffers, detection thresholds, scan mode, etc.) or reflects species-dependent variations.

Since large (5-10 mM) concentrations of caffeine produced propagated Ca2+ waves in CSQ-overexpressing cells, but not in control myocytes (Fig. 6A and B), we considered whether a similar mechanism might also contribute to the modulation of focal Ca2+ releases. We found that spontaneous Ca2+ releases sometimes showed saltatory propagation along z-lines, but this mechanism was not more pronounced in CSQ-overexpressing than in control myocytes (Fig. 2). It is more likely that propagated waves represent cells that are unusually active or Ca2+ overloaded.

The characteristic Ca2+ striping pattern of the ICa-activated Ca2+ release pattern in control cells (Fig. 3A) was absent (Figs 3B, 4 and 5) or only partially apparent (Fig. 8A and B, dashed lines) in transgenic myocytes. The analysis of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks and the patterns of Ca2+ release triggered by ICa indicate that the CSQ-overexpressing cells are capable of producing focal Ca2+ releases similar to those seen in control cells but with much lower frequency. This impairment may be, in part, related to downregulation of the expression of ryanodine receptors (Jones et al. 1998). In addition, ultrastructural distortion previously reported (Jones et al. 1998) may also alter the strategic location of RyRs, thereby diminishing their ability to sense influx of Ca2+ through the Ca2+ channel and trigger regenerative diadic Ca2+ releases. While transgenic cells show a spectrum of properties depending on the progression of hypertrophy with age (Knollmann et al. 1998a), b it should be noted that the cells selected for detailed spark analysis came from hearts with established hypertrophy and characteristic slow Ca2+ kinetics of ICa and Ca2+ transients (Fig. 3).

Ca2+ channel activity in transgenic mice

The most prominent change in the biophysical properties of the Ca2+ channel in CSQ-overexpressing transgenic myocytes is its slow inactivation compared to control mice (Figs 3D, 4C, 5C and 8C) such that t1/2 is increased from 8 to 24 ms (Fig. 3E). Such slow kinetics were first described by Jones et al. (1998) and were confirmed by Sato et al. (1998) in another murine CSQ-overexpressing transgenic strain. This effect appears to be unrelated to structural properties of the channel, as the kinetics of Ba2+ current through the Ca2+ channel of control and transgenic myocytes remained similar (data not shown). Furthermore, since the peak value of ICa shows little (< 25 %) or no change, the marked decrease in the rate of inactivation could not have resulted from a decrease in the influx of Ca2+ through the channel. We conclude therefore that the marked slowing of the kinetics of inactivation of ICa in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes of transgenic mice occurs secondary to the impaired Ca2+ release from the ryanodine receptor (Figs 3, 4, 5 and 8; see also Jones et al. 1998). Such Ca2+ cross-talk has been quantified in rat ventricular myocytes where Ca2+ release appears to determine 60–70 % of the Ca2+-induced inactivation of the Ca2+ channel (Lee et al. 1985; Adachi-Akahane et al. 1996).

Recovery of ICa-gated Ca2+ release

Low doses of caffeine (0.5 mM) largely restored the ability of CSQ-overexpressing cells to produce both spontaneous Ca2+ sparks at rest (cf. Figs 1 and 7), and ICa-gated cellular Ca2+ transients (cf. Figs 3 and 8). In experiments with sufficient signal-to-noise ratio to resolve individual Ca2+ sparks, it was consistently observed that augmentation of cellular Ca2+ transients was accompanied, primarily, by an increased number of Ca2+ sparks (Figs 4 and 5) which, in the presence of 0.5 mM caffeine, tended to fuse together (Fig. 8). Individual Ca2+ sparks, under these conditions, were seen clearly only near the edges of the cell (Fig. 8). Considering also that the more clearly resolved spontaneous Ca2+ releases in transgenic cells are similar to those in control cells with respect to their amplitude, duration and confinement, it is likely that the major effect of caffeine is to increase the number of focal Ca2+ releases.

The large, almost 2- to 2.5-fold, increase in the myocyte surface area noted earlier (Jones et al. 1998) and confirmed here in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes may, in part, distort the ultrastructural organization of the DHP-ryanodine receptor complex making the Ca2+ release mechanism, which requires an organized dyadic microdomain, less efficient. This would especially be true if the level of expression of ryanodine receptor were depressed, as reported by Jones et al. (1998). In transgenic mice overexpressing murine cardiac calsequestrin, Sato et al. (1998) report no decrease in the level of cardiac ryanodine receptors or the associated junctional proteins junctin or triadin, but do report strongly modified kinetics of ICa, consistent with the compromised ICa-gated Ca2+ release. These authors did, however, find that the ryanodine-associated FKB12 protein was suppressed. Removal of FKB12 protein in vitro has been reported to be associated with development of multiple substate openings and ‘chaotic’ behaviour of the ryanodine receptor (Brillantes et al. 1994; Marks, 1996). Our 2-D confocal imaging, however, failed to confirm significant focal Ca2+ sparks at rest in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes (Fig. 1). Discrete sparks associated with the activation of Ca2+ channels were also rare and appeared to be replaced by fairly disorganized sparks which may be responsible for the slow and uncoordinated global intracellular Ca2+ rise in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes. Although ultrastructural studies might suggest distortions in dyadic junctions with SR (Jones et al. 1998), the finding that low concentrations of caffeine re-establish Ca2+ signalling is not quite consistent with major ultrastructural changes in the DHP-RyR complex or its immediate microenvironment; rather it may reflect increased sensitivity of ryanodine receptors to Ca2+ (Rousseau & Meissner, 1989; Sitsapesan & Williams, 1990). An alternative possibility for the impairment of Ca2+ signalling is that high levels of luminal Ca2+ may directly, or via the junctional protein, reduce the sensitivity of ryanodine receptor to Ca2+ or Ca2+ signalling via the Ca2+ channel. Thus, the impairment in Ca2+ signalling may be related primarily to functional interaction of Ca2+ channels with ryanodine receptors, rather than distortions in the ultrastructural architecture of the DHP-RyR complex.

Enhancement of ICa by elevation of [Ca2+]o and isoproterenol was always less effective than low doses of caffeine in restoring ICa-gated Ca2+ release and producing only modest enhancements of the cellular Ca2+ transients (Figs 4F and 5F), which generally were related, but not strictly proportional, to changes in the magnitude and rate of inactivation of ICa (Figs 4D and 5D). Details of the observed responses may therefore reflect the fact that Ca2+ release is sensitive to changes in unitary Ca2+ current (Santana et al. 1996) and that inactivation of ICa is modulated not only by Ca2+ release, but also by screening charge effects of divalent cations, and modal shifts in the gating of ICa (McDonald et al. 1994). The variable effect of isoproterenol on recovery of Ca2+ signalling (data not shown) may reflect progression of the disease with age (Knollmann et al. 1998a) and the unexpected finding that enhancement of ICa by isoproterenol is pharmacologically different from that in control cells suggests a higher activity of phosphodiestrases in CSQ-overexpressing myocytes (Zhang et al. 1997; Knollmann et al. 1998b). Irrespective of these variations with age and experimental conditions, it seems unlikely that the β-adrenergic pathway can restore effective Ca2+ signalling in myocytes from CSQ-overexpressing mice with established cardiac hypertrophy.

The enhancements of the ICa-triggered Ca2+ releases by 10 mM [Ca2+]o, 3 μM isoproterenol, and, especially, 0.5 mM caffeine were paralleled at rest by changes in the basal Ca2+ signal (Fr/F0, Figs 4F, 5F and 8F). This increase in resting signal failed to return fully to baseline after washout of these inotropic agents (e.g. caffeine, Fig. 8F), suggesting that: (1) the effect of caffeine on [Ca]i is long lasting, (2) resting cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations are gradually increasing (Cleemann & Morad, 1991), (3) dialysis of fluo-3 is still in progress at the time of measurement, or (4) photo-damaged fluo-3, though producing an increase in cellular fluorescence, is insensitive to Ca2+ (Lipp et al. 1996). It is likely that the apparent effect of caffeine on basal [Ca2+]i (Fig. 8E and F) is real since it is much larger than the effects observed with elevation of [Ca2+]o (Fig. 4E and F) and isoproterenol (Fig. 5E and F). To distinguish clearly between the different possibilities and examine the physiological consequences of this finding it would be useful to perform accurately calibrated ratiometric measurements using, for example, indo-1 or fura-2 as Ca2+ probes.

Animal models of cardiac hypertrophy and impaired Ca2+ signalling

The pathophysiology of impaired Ca2+ signalling, cardiac hypertrophy, and heart failure seen in CSQ-overexpressing mice is distinctly different from the phenotype associated with other genetically modified animal models, including mice overexpressing the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, Ca2+-ATPase, phospholamban, or the α1c subunit of the Ca2+ channel, as well as spontaneously hypertensive rats, and salt-sensitive mice. Overexpression of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (Adachi-Akahane et al. 1997; Terracciano et al. 1998), Ca2+-ATPase (He et al. 1997; Yao et al. 1998), and phospholamban (Chu et al. 1997; Masaki et al. 1998), or the knockout of phospholamban (Masaki et al. 1997) produced no change in myocyte or heart size and did not impair Ca2+ signalling. The overexpression of the α1c subunit of the Ca2+ channel produced a small (10-20 %) increase in cell size, but did not alter Ca2+ release (Muth et al. 1999). The overexpression of Ca2+-ATPase or phospholamban and knockout of phospholamban appeared to regulate Ca2+ signalling only by altering the Ca2+ content of the SR. For instance, the increased SR Ca2+ content of phospholamban-deficient cardiomyocytes was reported to be directly related to an increased frequency of nearly unchanged Ca2+ sparks (Santana et al. 1997) and could be normalized by decreasing the Ca2+ content of the SR. Thus up- or downregulation of the Ca2+ content is not sufficient by itself to produce impairment of Ca2+ signalling or cardiac hypertrophy. In comparison, cells from hypertrophied hearts of spontaneously hypertensive rats produced larger Ca2+ sparks without a change in the SR Ca2+ content (Shorofsky et al. 1998).

Overexpression of CSQ and the α1c subunit of the Ca2+ channel was unexpectedly accompanied by impaired β-adrenergic signalling (Zhang et al. 1997; Muth et al. 1999). Whether the defect in β-adrenergic signalling is a prerequisite for cardiac hypertrophy and failure, as previously suggested (Cho et al. 1999), remains to be determined. The impaired Ca2+ signalling of CSQ-overexpressing myocytes did not recover significantly in the presence of β-adrenergic agonists, as was reported for those of salt-sensitive mice in heart failure (Gomez et al. 1997). It might be of some interest to see if a modulation of Ca2+ signalling by caffeine is as effective in other models of heart failure as it is in murine CSQ-overexpressing myocytes. Although CSQ levels do not appear to change with cardiac disease in man, it is of interest that CSQ overexpression in mice exhibits the syndrome of hypertrophy and electrical remodelling almost identical to that found in human heart failure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1-HL16152 and Grant-in-Aid 9808116U from the American Heart Association.

References

- Adachi-Akahane S, Cleemann L, Morad M. Cross-signaling between L-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;108:435–454. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.5.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi-Akahane S, Lu L, Li Z, Frank JS, Philipson KD, Morad M. Calcium signaling in transgenic mice overexpressing cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;109:717–729. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.6.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brillantes A, Ondrias K, Scott A, Marks A. Stabilization of calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) by FK-506 binding protein. Cell. 1994;77:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callewaert G, Cleemann L, Morad M. Caffeine-induced Ca2+ release activates Ca2+ extrusion via Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in cardiac myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;268:1045–1049. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.257.1.C147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MB, Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Spatial non-uniformities in [Ca2+]i during excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac myocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1994;67:1942–1956. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80677-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MB, Cheng H, Lederer WJ. The control of calcium release in heart muscle. Science. 1995;268:1045–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.7754384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer MR, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Ca2+ sparks and [Ca2+]i waves in cardiac myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270:C148–159. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.1.C148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science. 1993;262:740–744. doi: 10.1126/science.8235594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M-C, Rapacciuolo A, Koch WJ, Kobayashi Y, Jones LR, Rockman HA. Defective β-adrenergic receptor signaling precedes the development of dilated cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice with calsequestrin overexpression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:22251–22256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu G, Dorn GW, Luo W, Harrer JM, Kadambi VJ, Walsh RA, Kranias EG. Monomeric phospholamban overexpression in transgenic mouse heart. Circulation Research. 1997;81:485–492. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleemann L, DiMassa G, Morad M. Ca2+ sparks within 200 nm of the sarcolemma of rat ventricular cells: Evidence form total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. In: Siedman S, Beyer R, editors. Analytical and Quantitative Cardiology. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleemann L, Morad M. Role of Ca2+ channel in cardiac excitation-contraction coupling in the rat: evidence from Ca2+ transients and contraction. The Journal of Physiology. 1991;432:283–312. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleemann L, Wang W, Morad M. Two-dimensional confocal images of organization, density, and gating of focal Ca2+ release sites in rat cardiac myocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:10984–10989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez AM, Valdivia HH, Cheng H, Lederer MR, Santana LF, Cannell BM, McCune SA, Altschuld RA, Lederer WJ. Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science. 1997;276:800–806. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Jorgenson AO, Jones LR, Campbell KP. Biochemical characterization and molecular cloning of cardiac triadin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:458–465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp technique for high resolution current recording from cells and cell-free patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Giordano FJ, Hilal-Dandan R, Choi D-J, Rockman HA, McDonough PM, Bluhm W, Meyer M, Sayen R, Swanson E, Dillmann WH. Overexpression of the rat sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase gene in the heart of transgenic mice accelerates calcium transients and cardiac relaxation. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;100:380–389. doi: 10.1172/JCI119544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto N, Ronjat M, Meszaros LG, Koshita M. Postulated role of calsequestrin in the regulation of calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6764–6771. doi: 10.1021/bi00442a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LR, Suzuki YJ, Wang W, Kobayashi YM, Ramesh V, Franzini-Armstrong C, Cleemann L, Morad M. Regulation of Ca2+-signaling in transgenic mouse cardiac myocytes overexpressing calsequestrin. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101:1385–1393. doi: 10.1172/JCI1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LR, Zhang L, Sanborn K, Jorgensen AO, Kelley J. Purification, primary structure, and immunological characterization of the 26-kDa calsequestrin binding protein (junctin) from cardiac junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:30787–30796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T, Kasai M. Regulation of calcium channel in sarcoplasmic reticulum by calsequestrin. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1994;199:1120–1127. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knollmann BC, Duc J, Groth A, Weissman NJ, Cleemann L, Morad M. Cardiac phenotype of transgenic mice overexpressing calsequestrin. Circulation. 1998a;98:I-490. [Google Scholar]

- Knollmann BC, Jones LR, Morad M. Electrophysiologic properties of transgenic myocytes overexpressing cardiac calsequestrin. Circulation. 1998b;98:I-187. [Google Scholar]

- Lee KS, Marban E, Tsien RW. Inactivation of calcium channel in mammalian heart cells: joint dependence on membrane potential and intracellular calcium. The Journal of Physiology. 1985;364:395–411. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp P, Luscher C, Niggli E. Photolysis of caged compounds characterized by ratiometric confocal microscopy: a new approach to homogeneously control and measure the calcium concentration in cardiac myocytes. Cell Calcium. 1996;19:255–266. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(96)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Lopez JR, Shacklock PS, Balke CW, Wier WG. Local calcium transients triggered by single L-type calcium currents in cardiac cells. Science. 1995;268:1042–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.7754383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald TF, Pelzer S, Trautwein W, Pelzer DJ. Regulation and modulation of calcium channels in cardiac, skeletal and smooth muscle cells. Physiological Reviews. 1994;74:365–507. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan DH, Wong PT. Isolation of a calcium-sequestering protein from sarcoplasmic reticulum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1971;68:1231–1235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.6.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks A. Molecular structure of calcium release channels. In: Morad M, Ebashi S, Trautwein W, Kurachi Y, editors. Molecular Physiology and Pharmacology of Cardiac Ion Channels and Transporters. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluver Academic Publishers; 1996. pp. 397–408. [Google Scholar]

- Masaki H, Sako H, Kadambi VJ, Sato Y, Kranias EG, Yatani A. Overexpression of phospholamban alters inactivation kinetics of L-type Ca2+ channel currents in mouse atrial myocytes. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Cardiology. 1998;30:317–325. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki H, Sato Y, Luo W, Kranias EG, Yatani A. Phospholamban deficiency alters inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels in mouse ventricular myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:H606–612. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra R, Morad M. A uniform enzymatic method for dissociation of myocytes from hearts and stomachs of vertebrates. American Journal of Physiology. 1985;249:H1056–1060. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.5.H1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muth JN, Yamaguchi H, Mikala G, Grupp IL, Lewis W, Cheng H, Song L-S, Lakatta EG, Varadi G, Schwartz A. Cardiac-specific overexpression of the α1 subunit of the L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel in transgenic mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:21503–2150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BZ, DeMaria CD, Yue DT. Calmodulin is the Ca2+ sensor for Ca2+-dependent inactivation of L-type calcium channels. Neuron. 1999;22:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin N, Olcese R, Bransby M, Lin T, Birnbaumer L. Ca2+-induced inhibition of the cardiac Ca2+ channel depends on calmodulin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:2435–2438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau E, Meissner G. Single cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release channel: activation by caffeine. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:H328–333. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.2.H328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana LF, Cheng H, Gomez AM, Cannell MB, Lederer WJ. Relation between the sarcolemmal Ca2+ current and Ca2+ sparks and local control theories for cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Circulation Research. 1996;78:166–171. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana LF, Kranias EG, Lederer WJ. Calcium sparks and excitation-contraction coupling in phospholamban-deficient ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1997;503:21–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.021bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Ferguson DG, Sako H, Dorn GW, II, Kadambi VJ, Yatani A, Hoit BD, Walsh RA, Kranias EG. Cardiac-specific overexpression of mouse cardiac calsequestrin is associated with depressed cardiovascular function and hypertrophy in transgenic mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:28470–28477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham JSK, Cleemann L, Morad M. Functional coupling of Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in cardiac myocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:121–125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorofsky SR, Aggarwal R, Corretti M, Baffa JM, Strum JM, Al-Seikhan BA, Kobayashi YM, Jones LR, Wier WG, Balke CW. Cellular mechanism of altered contractility in the hypertrophied heart. Big hearts, big sparks. Circulation Research. 1998;84:424–434. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitsapesan R, Williams AJ. Mechanism of caffeine activation of single calcium-release channel of sheep cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;423:425–439. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldatov NM, Oz M, O'Brien KA, Abernethy DR, Morad M. Molecular determinants of L-type Ca2+ channel inactivation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:957–963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano CM, De Souza AI, Philipson KD, MacLeod KT. Na+-Ca2+ exchange and sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+ regulation in ventricular myocytes from transgenic mice overexpressing the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;512:651–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.651bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Morad M. Caffeine restores Ca signaling and spark formation in transgenic myocytes over-expressing calsequestrin. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:W-368. [Google Scholar]

- Yao A, Su Z, Dillmann W, Barry WH. Sarcoplasmic reticulum function in murine ventricular myocytes overexpressing SR CaATPase. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1998;30:2711–2718. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Kelley J, Schmeisser G, Kobayashi YM, Jones LR. Complex formation between junctin, triadin, calsequestrin, and ryanodine receptor. Proteins of the cardiac junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:23389–23397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zühlke RD, Pitt GS, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW, Reuter H. Calmodulin supports both inactivation and facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nature. 1999;399:159–162. doi: 10.1038/20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]