Abstract

Early in development, ascidian muscle cells generate spontaneous, long-duration action potentials that are mediated by a high-threshold, inactivating Ca2+ current. This spontaneous activity is required for appropriate physiological development.

Mature muscle cells generate brief action potentials only in response to motor neuron input. The mature action potential is mediated by a high-threshold sustained Ca2+ current.

Action potentials recorded from these two stages were imposed as voltage-clamp commands on cells of the same and different stages from which they were recorded. This strategy allowed us to study how immature and mature Ca2+ currents are optimized to their particular functions.

Total Ca2+ entry during an action potential did not change during development. The developmental increase in Ca2+ current density exactly compensated for decreased spike duration. This compensation was a function purely of Ca2+ current density, not of the transition from immature to mature Ca2+ current types.

In immature cells, Ca2+ entry was spread out over the entire waveform of spontaneous activity, including the interspike voltage trajectory. This almost continuous Ca2+ entry may be important in triggering Ca2+-dependent developmental programmes, and is a function of the slightly more negative voltage dependence of the immature Ca2+ current.

In contrast, Ca2+ entry in mature cells was confined to the action potential itself, because of the slightly more positive voltage dependence of the mature Ca2+ current. This may be important in permitting rapid contraction-relaxation cycles during larval swimming.

The inactivation of the immature Ca2+ current serves to limit the frequency and burst duration of spontaneous activity. The sustained kinetics of the mature Ca2+ current permit high-frequency firing during larval swimming.

Ca2+ entry plays a key role in translating electrical activity into cellular output. In a given cell, that cellular output changes during development. In mature cells, it takes the form of physiological processes such as transmitter release or contraction. In developing cells, Ca2+ entry triggers activity-dependent developmental programmes, such as those controlling neurite outgrowth, synaptic connectivity, or ion channel maturation (Gu & Spitzer, 1997; Moody, 1998a, b). The forms of electrical activity that underlie Ca2+ entry serving these two functions are often very different. In developing cells, activity most often takes the form of spontaneous, long-duration action potentials, whereas in mature cells, action potentials are most often short in duration and triggered by external inputs (Spitzer, 1991; Moody, 1995). This difference is reflected in the ion channels that mediate activity: the properties of ion channels present at early stages of development are often markedly different from those of their mature counterparts (Moody, 1998a, b). How these properties are optimized to mediate the patterns of Ca2+ entry required at different stages of development is poorly understood.

We have studied this question in developing ascidian muscle. Ascidians are marine chordates whose small cell number in the larvae, rapid development, and early commitment of cell fates have made them a classic preparation in embryology. In the species we use, Boltenia villosa, muscle lineage cells in the larva are pigmented, so they can be identified at all stages of development. We have used this property to make an extensive voltage-clamp study of the development of Ca2+ and K+ channels in these cells (larval ascidian muscle has no Na+ current; contraction is triggered by Ca2+ entry) (Davis et al. 1995; Greaves et al. 1996; Dallman et al. 1998). Early in development, just after neurulation and before innervation and contractility appear, Boltenia muscle cells are spontaneously active. Activity takes the form of 2–4 Hz bursts of action potentials lasting about 20 s, separated by 1 min silent periods. Action potentials are long in duration (mean 34 ms) and are mediated by a high-threshold, inactivating Ca2+ current (ICa(i)) and a voltage-gated delayed K+ current which activates slowly (τ= 60 ms). Spontaneous activity lasts about 6 h, starting just after neurulation, and is triggered by the transient absence during that time of the resting conductance of the cells, an inwardly rectifying K+ current. The inward rectifier is present at all stages of development before and after this spontaneous activity occurs. In mature muscle, action potentials occur only in response to motor neuron input, are short in duration (mean 9.4 ms), and can occur at frequencies up to 10–20 Hz during larval swimming. The mature action potential is mediated by a high-threshold, sustained Ca2+ current (ICa(m)) and a Ca2+-activated K+ current that activates rapidly (τ= 8 ms). The development of this Ca2+-activated K+ current, which shortens the action potential, depends completely on the spontaneous activity: blocking this activity prevents its appearance in mature muscle, without affecting the development of any other current (Dallman et al. 1998).

These cells therefore exist in two distinct electrophysiological states, each with its stage-specific forms of activity, Ca2+ and K+ channel types, and Ca2+-dependent cellular functions. In this paper, we examine how the immature and mature ion channels are optimized to their stage-specific roles. To do this, we have used action potential waveforms (APWs) recorded from immature and mature cells as voltage-clamp commands (Llinas et al. 1982; Gola et al. 1986; McCobb & Beam, 1991). We find that the slightly more negative activation voltage and the inactivation of ICa(i) serve to spread out Ca2+ entry over the entire waveform of spontaneous activity, including the subthreshold interspike voltage trajectory. ICa(i) inactivation also limits spontaneous activity to relatively low frequencies. As action potential duration shortens during development, total Ca2+ entry per event (spike plus interspike voltage trajectory) does not change, because the increased density of ICa(m) compensates for the shorter spike duration. Ca2+ entry in mature muscle is, however, confined to the action potential waveform itself. This is due to the more positive voltage of activation and the lack of inactivation of ICa(m), properties which also permit high-frequency firing. These results emphasize the significance of differences between immature and mature ion channel types and the complex relationships that exist between them.

METHODS

Animals and cell culture

Boltenia villosa were collected from Puget Sound and maintained as described in Greaves et al. (1996). Muscle lineage cells of Boltenia villosa are pigmented, allowing us to identify them throughout development. Because few if any tissue interactions are required for muscle development, these cells differentiate normally in dissociated preparations (Greaves et al. 1996). All cells were dissociated at neurula stage as in Greaves et al. (1996) and cultured to maturity. Intact embryos reared in parallel with the cells were used to determine staging. At 12°C, typical timing of various stages of development is as follows: neurulation, 16 h; tailbud (beginning of tail extension), 20 h; hatching, 36 h.

Solutions

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise noted.

External solutions

Artificial sea water (ASW) contained (mM): 400 NaCl, 10 KCl, 50 MgCl2, 10 CaCl2, 10 Hepes (pH 8.0, with 1 M NaOH). For the modified ASWs, only constituents differing from ASW are listed. Divalent free sea water (DFSW) contained (mM): 460 NaCl, 0 MgCl2, 0 CaCl2, 0.5 EGTA. BaASW contained (mM): 0 CaCl2, 10 BaCl2. Cadmium ASW contained (mM): 5 CaCl2, 5 CdCl2. Pronase ASW contained: 1 mg ml−1 pronase E in ASW.

Internal solutions

The pipette solution for voltage-clamp recording contained (mM): 200 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 20 Hepes, 0.1 cAMP, 2 ATP, 400 D-sorbitol (to maintain osmotic balance) (pH 7.3, with CsOH). The pipette solution for recording activity during current clamp was as above with the substitution of KCl for CsCl (pH 7.3, with KOH).

Electrical recordings

Currents were recorded with perforated patch whole-cell recording (Horn & Marty, 1988; Greaves et al. 1996) using nystatin. A stock solution of 30 mg ml−1 nystatin in DMSO (stored at -20°C for up to 2 weeks) was diluted into the internal solution to give a working concentration of 300 μg ml−1. Pipette tips were dipped in internal solution without nystatin and backfilled with nystatin-containing solution. Patch perforation was monitored by recording capacitative transients. Perforation took an average of 5 min after seal formation. Because yolk granules present in ascidian muscle at all stages of development often clog whole-cell pipettes, we found that perforated patch recordings usually yielded lower series resistance values than conventional whole-cell recordings. Series resistance in our recordings was typically 5 MΩ or less. Recordings were made using the List Electronic EPC-7 amplifier, filtered at 0.5 kHz with an 8-pole Bessel filter. Pipettes were pulled from 50 μl haematocrit glass (VWR Scientific) using a Narishige two-stage puller to obtain 1–4 MΩ resistance in sea water. Capacitance was measured as described in Moody & Bosma (1985).

Action potential waveform clamp

Action potential waveforms were recorded from immature (20 h) and mature (36 h) muscle using K+-containing pipette solution. To ensure the accuracy of recorded waveforms, only recordings with input resistance > 5 GΩ were used (see Results). Waveforms were recorded using pCLAMP6 software (Axon Instruments), and then replayed as commands in voltage clamp in other cells. Leak and capacitative currents were subtracted by playing the same APW command superimposed on a holding potential of -100 mV, so that no active currents flowed during the command, or by replaying the APW command from the normal holding potential after exposing the cell to 5 mM Cd2+ to block all active currents (see Results; see also Llinas et al. 1982).

To quantify Ca2+ influx during the action potential, we integrated Ca2+ currents over the interval starting at threshold (defined as the point of maximum d2V/dt2) and ending at the post-spike minimum voltage. Baseline was determined as the portion of the trace that was most flat (the part that, when averaged, had the smallest standard deviation). This value was taken as zero current, and traces were analysed accordingly. All statistical P values were calculated using Student's unpaired t test. Values are means ±s.e.m.

RESULTS

Properties of Ca2+ currents in immature and mature ascidian muscle

There are three calcium current subtypes in Boltenia muscle, with different physiological properties and developmental profiles (Davis et al. 1995; Greaves et al. 1996). We have previously shown that these currents can be separated on the basis of voltage dependence, kinetics and conotoxin sensitivity.

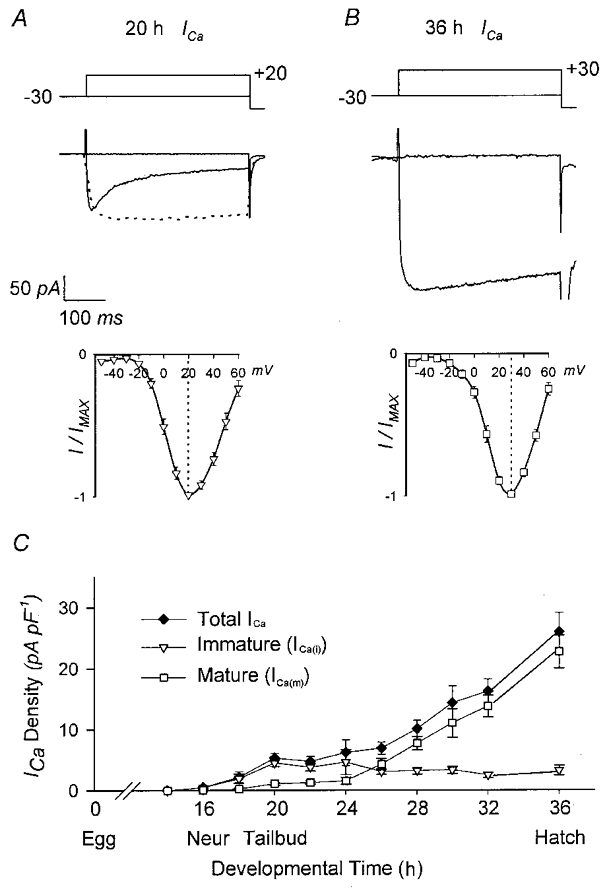

In immature muscle, the major calcium current is a high-threshold, inactivating Ca2+ current, ICa(i) (Fig. 1A). Inactivation of this current depends on Ca2+ entry (Davis et al. 1995). ICa(i) begins to activate at -20 mV and peak current occurs at +20 mV. ICa(i) first appears at 18 h, just after neurulation. By 20 h, it is expressed at an average density of 5 pA pF−1 and persists at this density through the rest of development.

Figure 1. Calcium currents in immature and mature muscle cells.

A, ICa(i) recorded from a 20 h muscle cell in response to rectangular voltage steps. Current inactivates significantly during the pulse; inactivation is prevented by substituting Ba2+ for Ca2+ as the charge carrier (dotted trace). Below is shown the average I–V relationship for ICa(i) (n = 7 cells), normalized to peak current. Peak current occurs at +20 mV. B, ICa(m) recorded from a 36 h muscle cell. The current shown is a mixture of ICa(m) and ICa(i), since ICa(i) is retained in the mature cells. On average, ICa(m) comprises 85 % of the current at this stage. ICa(m) shows little if any inactivation. Below is shown the average I–V relationship at this stage, normalized to peak current. Peak current occurs at +30 mV, and compared to ICa(i), a relatively small proportion of the current is activated negative to 0 mV. C, developmental profiles of ICa(i), ICa(m) and total ICa at 11 stages of development (adapted from Greaves et al. 1996). Note that total ICa increases about 5-fold between 20 and 36 h, and the relative contributions of ICa(i) and ICa(m) are approximately inverse at the two stages.

In mature muscle, the major Ca2+ current is high-threshold and sustained (ICa(m); Fig. 1B). ICa(m) begins to activate at about -10 mV and peak current occurs at +30 mV; both values are about 10 mV more positive than those for ICa(i). ICa(m) is initially expressed at 26 h and reaches an average density of 20 pA pF−1 in mature cells (36 h), in which it comprises 85 % of the total ICa (Fig. 1B). The small amount of ICa(i) that is retained in mature muscle can be seen as a shoulder on the I–V relationship in Fig. 1B.

Thus during development there is a transition between two forms of ICa, with the immature form differing from the mature form in three ways: its more negative voltage dependence, its inactivation and its low density.

A third Ca2+ current, which is expressed in some muscle cells at all stages of development, is a low-threshold, voltage-inactivated Ca2+ current (ICa(t)). In contrast to ICa(i), ICa(t) is elicited only from negative pre-potentials (< -80 mV, as opposed to < -30 mV for ICa(i)), reaches peak amplitude at 0 mV (as opposed to +20 mV for ICa(i)), and inactivates more rapidly. ICa(t) is expressed in only about 40 % of immature cells, and in those, its density is very low (0.45 ± 0.07 pA pF−1). Because ICa(t) is absent in almost half of the immature cells and present only at very low density in the others, we have not studied its role in mediating Ca2+ entry. We have not found a specific blocker for ICa(t). There are no sodium currents expressed in ascidian muscle cells.

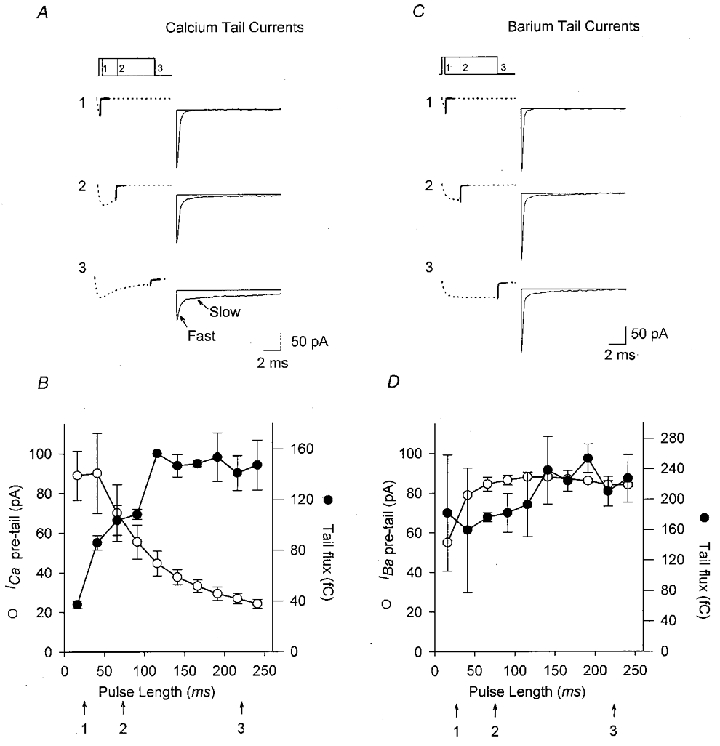

Reopening of inactivated ICa(i) channels

Some high-threshold inactivating Ca2+ channels reopen obligatorily in making the transition from the inactivated to the closed states on repolarization (Slesinger & Lansman, 1991). If such reopenings occurred in ICa(i) channels, they would augment Ca2+ entry during spontaneous activity by creating a conductance for calcium on the downstroke of each action potential, when the Ca2+ driving force is high. To test for reopening of inactivated ICa(i) channels in immature muscle, we analysed currents flowing at the termination voltage pulses of varying durations to +20 mV, which maximally activate ICa(i). The currents at the termination of such pulses consisted of two components (Fig. 2A). The fast component became smaller as the prepulse became longer and ICa(i) inactivated, indicating that it was a true ‘tail’ current resulting from direct closing of Ca2+ channels open at pulse termination. The slower component became larger with longer prepulses, suggesting that it results from reopening of Ca2+ channels which are in the inactivated state at the termination of the prepulse. When inactivation was blocked by substituting Ba2+ for Ca2+ as the charge carrier, the fast component no longer decreased with increasing pulse duration, as expected because the number of Ca2+ channels open at the end of the pulse does not change with increased pulse duration. The slow component, in contrast, was almost eliminated in Ba2+, as predicted from the lack of channels that enter the inactivated state. When Ca2+ was the charge carrier, the net result of these two opposing changes in post-pulse current amplitude is that total Ca2+ flux after pulse termination increased with pulse duration, in direct proportion to the amount of ICa(i) inactivation at the end of the pulse (Fig. 2B). This effect was eliminated in Ba2+ (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Reopening of inactivated ICa(i) channels.

A, 20 h muscle cells, which express predominantly ICa(i), were stimulated with rectangular voltage pulses of varying durations to +20 mV. Calcium tail currents following pulse termination are highlighted in black and displayed to the right on an expanded time scale. Representative currents for pulse durations of 25, 75 and 225 ms are shown. The fast tail component, representing Ca2+ current flowing through channels that were open at the end of the pulse, decreases with increasing pulse duration. The slow tail current, representing Ca2+ currents flowing through channels that were inactivated at the end of the pulse and which reopen following pulse termination, increases with increasing pulse duration. Currents were leak and capacitance subtracted. B, relationship between ICa at pulse termination (^) and total charge flux during tail currents (•) and pulse duration. As pulse length increases, ICa at pulse termination decreases due to inactivation, and charge flux during tail currents increases. C and D, same experiments as in A and B, but with Ba2+ substituted for Ca2+ as the charge carrier to prevent inactivation. The slow tail component is absent, and the amplitude of the fast tail current and the charge flux during the tail current do not change with pulse duration.

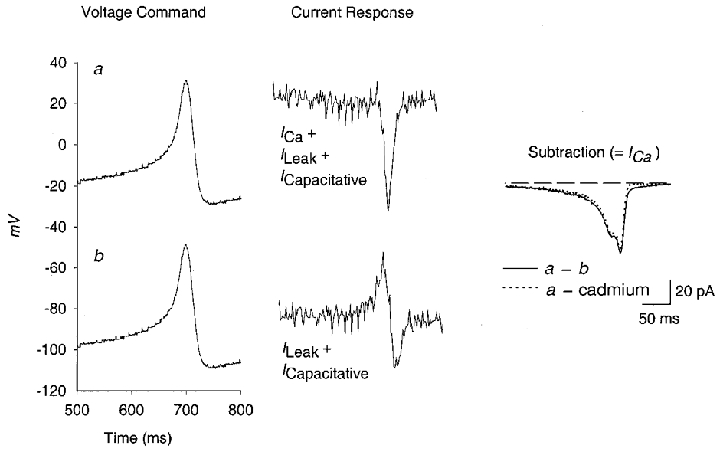

Using action potential waveform commands to measure Ca2+ flux during activity

The numerous and complex changes in Ca2+ and K+ current kinetics, density and voltage dependence that occur during the development of these cells all affect the pattern of Ca2+ flux during activity. Fortunately, all of these changing parameters exert their effects on calcium entry by means of voltage and are thus encapsulated in the action potential waveforms that they help to shape. To study these effects, we therefore digitized action potential waveforms recorded under normal conditions (K+ in the pipette solution) and replayed them into cells as voltage-clamp commands under conditions that isolate Ca2+ currents (Cs+ in the pipette solution). The resulting Ca2+ currents flowing during these commands represent the Ca2+ flux during the action potential.

For this approach to be accurate, both the waveform of recorded action potentials and the subtraction of leak and capacitative currents during the waveform command must be correct. For recording action potential waveforms, we accepted only experiments in which the input resistance was 5 GΩ or greater (measured at -60 mV, where the inward rectifier, if present, is not activated). We judged that such records were accurate by three criteria: (1) spontaneous activity recorded in immature cells matched the frequency of activity recorded extracellularly, using cell-attached patches (Dallman et al. 1998); (2) in more mature cells, where attached-patch recordings show no spontaneous activity, we recorded only stable, resting potentials negative to -60 mV in perforated-patch recordings; (3) the maximum dV/dt of recorded spikes occurred at the same potential as the maximum net inward current recorded during step commands. Action potentials representative of average waveform parameters (threshold, rate of rise, frequency) were chosen to be digitized and used as commands.

Subtraction of leak and capacitative currents is also more difficult during commands in which voltage is constantly changing than during step commands, where these currents can be distinguished kinetically from voltage-gated currents. We isolated leak and capacitative currents by replaying the APW command from a very negative holding potential (-100 mV) so that the entire waveform occurred at potentials at which no voltage-gated currents are activated. (The inward rectifier is absent in immature cells, and blocked by internal Cs+ in mature cells.) Figure 3 shows raw currents, leak and capacitative currents, and the subtracted ICa trace from one such experiment. To check that this method was accurate, we determined leak + capacitative currents in some cells by replaying the APW at normal holding potential after application of 5 mM Cd2+ to block all Ca2+ currents. Figure 3 shows that the subtracted ICa traces are almost identical using these two methods.

Figure 3. Subtraction protocol for APW commands.

The total current that flows in response to an APW command is the sum of ICa, leak and capacitative currents. A control APW command and these associated currents are shown in the top row. To isolate leak and capacitative currents, the same APW command was applied with an 80 mV negative voltage offset, so that no active currents flowed (bottom trace). Subtraction of these two yielded the isolated ICa shown on the right. To confirm the accuracy of this method, leak and capacitative currents were also isolated by blocking ICa with a saturating dose of cadmium (5 mM) and applying the APW command with no voltage offset. The resulting subtracted ICa is shown on the right as the dotted trace. The dashed line represents zero current. All subsequent data were obtained using the offset method of subtraction.

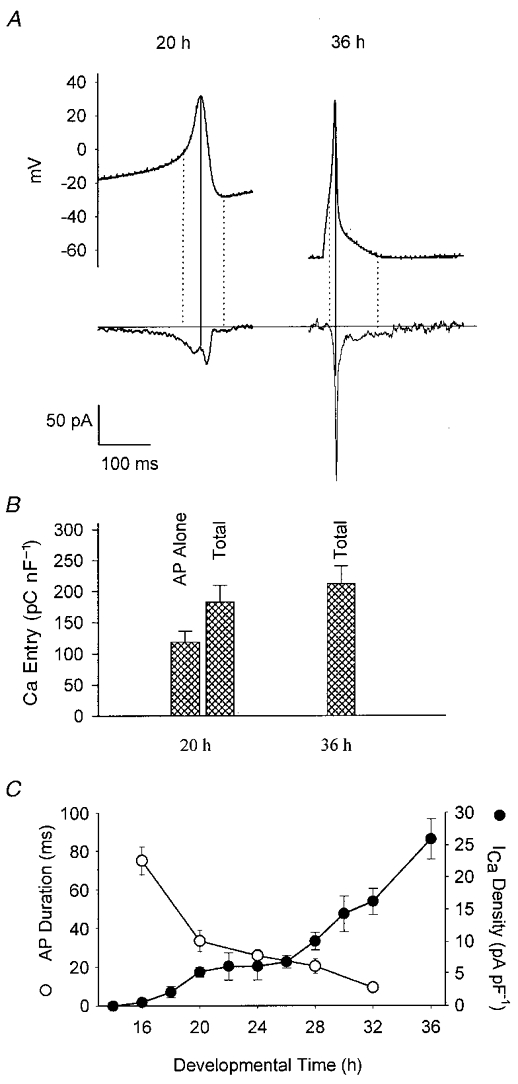

Calcium currents resulting from immature APWs replayed into immature cells showed a characteristic two-peaked appearance (Figs 3 and 4A). The first peak occurred on the rising phase of the spike, and results from the initial opening of Ca2+ channels. Ca2+ entry decreases when the APW reaches its peak, because of decreased driving force for Ca2+ entry. A second, larger peak of Ca2+ entry occurred on the falling phase of the spike waveform, as the driving force increases again. This current probably flows through Ca2+ channels that have opened for the first time late in the waveform, and through those that have reopened after entering the inactivated state (see Fig. 2).

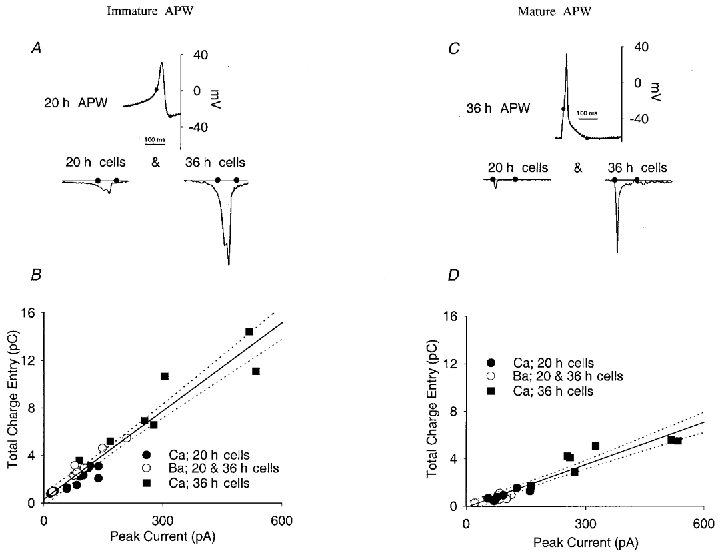

Figure 4. Changes in action potential-mediated Ca2+ fluxes with development.

A, typical action potential waveforms recorded from 20 and 36 h cells and used as commands in cells of the same stages. Subtracted Ca2+ currents flowing during these commands are shown below. The 20 h action potential is taken from a burst of spontaneous activity whereas the 36 h action potential was stimulated by a brief current pulse. The vertical dotted lines demark the action potential itself, defined as starting at maximum d2V/dt2 and ending at minimum post-spike voltage (see text). B, total Ca2+ fluxes during activity were quantified by integrating the Ca2+ current traces either over the action potential itself, or over the entire waveform of activity including a single spike. These two were the same for the 36 h cell. In the 20 h cell, Ca2+ flux during the action potential accounts for only 65 % of the total flux per spike during activity. When this interspike flux is included in the total, the flux per spike does not change during development. C, this result can be accounted for by the reciprocal changes in total ICa density and action potential duration during development. These parameters are plotted vs. developmental time (adapted from Greaves et al. 1996).

Developmental changes in the profile of AP-triggered Ca2+ influx

We first compared Ca2+ fluxes during single APW commands in 20 h cells (the peak of spontaneous activity) and 36 h cells (fully mature muscle) (Fig. 4). APWs were imposed (Cs+ in the pipette solution) on cells of the same stage as those from which they were recorded (K+ in the pipette solution). The APWs recorded from 20 h cells were parts of bursts of spontaneous activity. These action potentials ride on a very depolarized potential, with an interspike trajectory rising from -25 mV to a threshold at near 0 mV. In contrast, spikes in 36 h cells were triggered by current pulses, delivered from a stable -60 mV resting potential. This approximates the normal synaptic stimulation of muscle, which we have recorded from intact larvae. Threshold for these spikes was about -30 mV. In both cells, the peak of the action potential occurred at about +35 mV.

There was very little difference in the total Ca2+ flux during one entire action potential waveform at the two stages of development. If we integated ICa over the entire waveform in immature cells, including the interspike trajectory, Ca2+ entry did not differ between immature and mature action potentials (immature: 0.183 ± 0.026 pC pF−1, n = 7; mature: 0.212 ± 0.028 pC pF−1; P = 0.389). However, if we restricted our integration of ICa to the action potential itself, defined as starting at the point of maximum d2V/dt2 and ending at the most negative post-spike potential (see Fig. 4A, dotted vertical lines), mature action potentials admitted, on average, 1.8 times as much Ca2+ as immature spikes, in their respective cells (immature cells: 0.119 ± 0.017 pC pF−1, n = 7; mature cells: 0.212 ± 0.028 pC pF−1, n = 8; P = 0.01; Fig. 4B). This difference is very close to that predicted from the fact that mature action potentials are 28 % the duration of immature spikes, but have total ICa densities 5 times larger (Greaves et al. 1996). Thus the main difference between the two stages is that in mature cells Ca2+ entry is almost entirely restricted to the spike waveform itself, whereas in immature cells a large fraction of the Ca2+ entry occurs between spikes, during the slow depolarization that leads to threshold. This is probably due to the more negative voltage dependence of ICa(i): the interspike trajectory starts at about -25 mV and reaches threshold at about 0 mV, a voltage range at which a much larger proportion of ICa(i) than ICa(m) is activated (see Fig. 1). Thus during development, Ca2+ entry during an action potential changes very little, despite the dramatic change in spike waveform, because increased ICa density compensates for decreased spike duration.

The influence of action potential waveform vs. Ca2+ current subtype on calcium influx

In the experiments of Fig. 4, applying recorded APWs appropriate for the cell's stage allowed us to simulate Ca2+ influx during normal development, in which both the action potential waveform and Ca2+ current subtype are changing simultaneously. By applying APWs recorded at one stage to cells of a different stage, we can distinguish between the contributions of Ca2+ current subtype and action potential waveform to Ca2+ entry.

First, we imposed both immature and mature APW commands on individual cells at both 20 and 36 h of development (Fig. 5), and integrated the Ca2+ currents during only the spike waveform itself, as defined above (filled circles in Fig. 5A and C). Both immature and mature APWs admit considerably more Ca2+ in a mature cell than in an immature cell. To determine whether this was a function of ICa type or simply ICa density, we plotted total Ca2+ flux vs. peak ICa determined in rectangular pulses (Fig. 5B and D). Because of variability of ICa density among cells of a single stage, and because ICa density is larger in mature cells, these relationships extend from about 10 pA to nearly 600 pA of ICa. When examined in this way, it is clear that Ca2+ entry during either an immature or a mature APW is a function only of ICa density, not type, because immature and mature cells fall on the same linear relationship for each waveform type. From the different slopes of the two relationships in Fig. 5B and D, we can conclude that when normalized to total ICa density, independent of ICa type, the immature APW admits an average of 2.1 times more Ca2+ than the mature waveform. This is not surprising since the immature waveform is longer in duration.

Figure 5. Role of action potential waveform and Ca2+ current subtype in determining Ca2+ flux.

A and B, action potential waveforms recorded from 20 h cells were used as commands in both 20 and 36 h cells with either Ca2+ or Ba2+ as the charge carrier. A, the 20 h waveform and the resulting Ca2+ current when it is applied to a 20 h (left) or 36 h (right) cell. B, Ca2+ flux during the immature APW command in 20 and 36 h cells plotted as a function of peak Ca2+ current obtained during rectangular pulses. ICa density at both stages varies among cells, although it is on average much larger in 36 h cells. Note that fluxes for both 20 and 36 h cells exposed to an immature APW waveform fall along the same line describing flux as a function of ICa density, indicating that ICa density, rather than subtype, is the major determinant of Ca2+ flux during the action potential. C and D, the same experiment as in A and B, but using a mature APW. The slope of the relationship between Ca2+ flux and ICa density is smaller, indicating that on average the shorter mature action potential admits less Ca2+ to the cell for a given ICa density.

These results imply that the ability of ICa(i) to admit Ca2+ during long immature action potentials is not affected by its inactivation, since it is as effective as ICa(m), which does not inactivate. Confirming this, when Ba2+ was substituted for Ca2+, to block ICa(i) inactivation, total Ba2+ entry during an immature APW fell along the same linear relationship as did Ca2+ entry (Fig. 5B, open circles). Inactivation probably has little effect on Ca2+ entry because even the long immature APW is relatively short compared to the time constant of inactivation. In addition, blocking inactivation has two opposing effects: first, slightly more entry occurs because the current is more sustained; and second, blocking inactivation reduces the burst of Ca2+ entry during spike repolarization due to channel reopening (see Fig. 6; see next section).

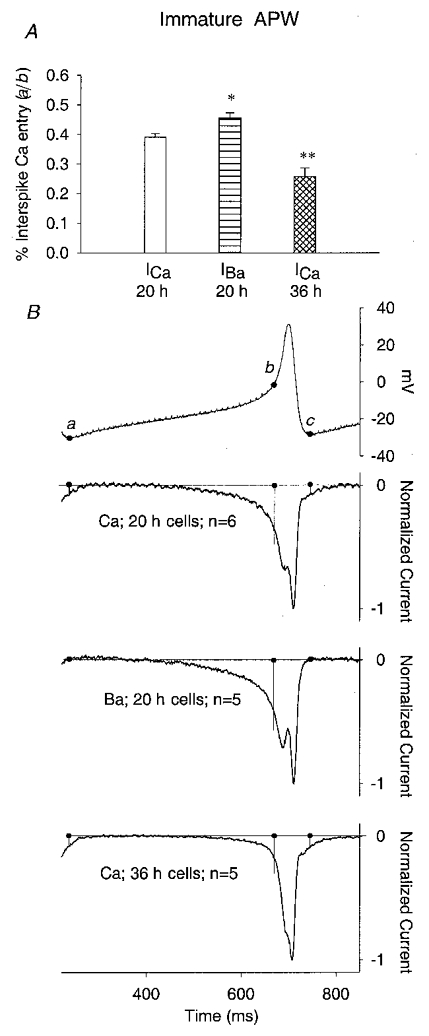

Figure 6. Function of ICa subtype in mediating interspike calcium entry in 20 and 36 h cells.

A, plot of percentage of total Ca2+ flux that occurs between immature action potentials in 20 h cells, using Ca2+ or Ba2+ as the charge carrier, and in 36 h cells, using Ca2+ as the charge carrier. Immature APWs were used for all cells. Spikes were defined as before, as starting at the maximum d2V/dt2 and ending at minimum post-spike voltage (see text). B, the immature APW used in these experiments (top), and the resulting ICa waveforms in 20 h cells, using Ca2+ or Ba2+ as the charge carrier, and in 36 h cells, using Ca2+ as the charge carrier. Filled circles mark the integration boundaries: between a and b for interspike fluxes; between b and c for spike-mediated fluxes. Currents are normalized to their peak values. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01.

Optimization of the immature Ca2+ current for mediating interspike Ca2+ entry

The above conclusions were obtained by integrating ICa during only the spike waveform. In contrast, when interspike Ca2+ entry in response to immature total activity waveforms was examined, we found that ICa(i) and ICa(m) do admit Ca2+ differently (Fig. 6). In immature cells, the fraction of total Ca2+ entry (a–c in Fig. 6) contributed by interspike entry (a–b) was 40 % whereas in mature cells responding to the same immature APW, it was only 24 % (Fig. 6B). This is caused by the more negative voltage dependence of ICa(i) (see Fig. 1), and, to a lesser extent, by Ca2+ channel reopening after the spike. These data show that these properties of ICa(i) are important for increasing total Ca2+ entry during spontaneous activity in immature cells, and for spreading out that Ca2+ entry over the entire waveform of activity. In other words, if the early part of the developmental profile of ICa were composed of ICa(m) rather than ICa(i), Ca2+ entry during spontaneous activity in immature cells would be reduced by about 16 %, and would occur in discrete events rather than being almost continuous during activity.

The results in Fig. 6 also show that reopening of inactivated channels contributes relatively little to Ca2+ entry during single action potentials. Substitution of Ba2+ for Ca2+ in immature cells increased the interspike Ca2+ entry by only about 10 %, and Ca2+ entry occurring immediately after spike repolarization is only a fraction of that. However, it may play a more significant role during bursts of spikes during spontaneous activity. Normal spontaneous activity comes in bursts of 2–4 Hz action potentials lasting on average 20 s, separated by silent periods lasting on average 74 s. It is possible that accumulating inactivation of ICa(i) during these bursts might result in a large post-burst Ca2+ entry at the start of each silent period. We have not tested this hypothesis directly.

Role of different inactivation properties of ICa(i) and ICa(m)

Most of the experiments above concentrated on the role of Ca2+ currents in mediating Ca2+ entry. It was initially puzzling, given the developmental importance of Ca2+ entry during spontaneous activity in immature cells, that the long-duration action potentials should be mediated by an inactivating, rather than a sustained, Ca2+ current. However, the above results show that inactivation of ICa(i) does not result in decreased Ca2+ entry during an action potential.

A second possible role of the transition from the inactivating ICa(i) to the sustained ICa(m) might be to mediate developmental changes in the repetitive firing abilities of the cells. Immature cells fire relatively low-frequency bursts of spontaneous activity, whereas mature muscle must fire repetitively at 10–20 Hz during larval swimming. To test whether cumulative inactivation of ICa(i) might be in part responsible for terminating bursts of action potentials during spontaneous activity, we replayed immature APWs into immature cells in brief 2 Hz bursts (Fig. 7). The Ca2+ current gradually decreased during such bursts, and stabilized at about half its initial value after 15–20 s (Fig. 7B), which is about the average burst length during spontaneous activity (Dallman et al. 1998). When the same experiment was repeated using Ba2+ as the charge carrier, there was very little decrease in ICa with repetitive APWs (Fig. 7B, □). In mature cells, even the long-duration immature APW could be repeated at 2 Hz without decrement in ICa, because ICa(m) does not inactivate (Fig. 7B, ▪). Thus it seems likely that gradual accumulation of [Ca2+]i during bursts of activity in immature cells leads to cumulative inactivation of ICa(i), which in turn terminates the burst. The transition to ICa(m) in the mature cell appears necessary for their ability to engage in high-frequency firing.

Figure 7. Responses of immature and mature Ca2+ currents to repetitive stimuli.

Cells were stimulated with a series of twenty immature APWs delivered at a frequency of 2 Hz, to mimic the spontaneous activity that normally occurs in 20 h cells. A, Ca2+ currents recorded during the 1st and 15th APW of this series in 20 h cells with Ca2+ as the charge carrier (top), 20 h cells with Ba2+ as the charge carrier (middle), and 36 h cells with Ca2+ as the charge carrier (bottom). Only the Ca2+ current of the 20 h cells decreases with repetitive stimuli. B, plot of mean data (n = 5 for each plot) for these experiments, showing that significant decrement during repetitive activity occurs only for the 20 h cell with Ca2+ as the charge carrier.

DISCUSSION

The physiological development of ascidian muscle is characterized by a 6 h period of spontaneous action potentials that occurs immediately after neurulation (Greaves et al. 1996). These action potentials are long in duration and are mediated by immature forms of Ca2+ and K+ currents. Ca2+ entry resulting from this activity is required for later expression of mature ion currents and of contractility (Dallman et al. 1998). After spontaneous activity ceases, muscle cells mature and become contractile. Mature muscle generates a short-duration action potential, which only occurs in response to nerve input. The mature action potential is mediated by mature forms of Ca2+ and K+ currents that have markedly different properties from their immature counterparts. Ca2+ entry during mature activity is required for contraction. Because we obtained the same developmental changes in ionic currents using either the perforated patch or conventional whole-cell method, it is likely to be the properties of the ion channels themselves, rather than constituents of the intracellular milieu, that are responsible (see e.g. Owens et al. 1996).

The experiments reported here investigated how the waveform of the action potential and the properties of the Ca2+ and K+ currents that determine that waveform control the different kinetics of Ca2+ entry required in immature and mature muscle. The action potential mechanisms must balance two requirements at each stage of development. The first is to be triggered by the appropriate stimuli and at the appropriate frequencies to serve its particular functions in immature and mature muscle. Thus, the immature spike must reliably occur spontaneously, because activity is required for later development but innervation has not yet occurred. The mature spike must occur only with nerve input, and at high enough frequencies to mediate larval swimming behaviour. The second requirement is that enough Ca2+ must enter during each event to trigger the appropriate response at each stage of development. So, even though mature muscle must be capable of high-frequency activity, each action potential must admit enough Ca2+ to reliably trigger contraction. Our experiments have shown how these constraints determine the patterns of Ca2+ entry in immature and mature cells. Although Ca2+ entry is only one of several parameters that control how activity translates into intracellular Ca2+ transients, isolating it experimentally will allow us to understand in later experiments how other properties that might change during muscle development, such as Ca2+ channel location and intracellular Ca2+ buffering systems, also participate in controlling the changing biological roles of Ca2+ signalling.

These experiments relied primarily on the technique of action potential waveform voltage clamp (McCobb & Beam, 1991; Scroggs & Fox, 1992). We recorded spontaneous activity in immature cells and evoked action potentials in mature cells and then replayed these waveforms as voltage-clamp commands under conditions that eliminated outward currents. The resulting current, after leak and capacitative current subtraction, represents Ca2+ entry during the waveform. This method was used in three types of experiments. First, by replaying APWs into cells of the same stages that generated them, we could ask how the kinetics and magnitude of Ca2+ entry during an action potential change during development. Second, by replaying several APWs recorded at different stages into a single cell, we could ask how action potential waveform, independent of the properties of the underlying Ca2+ currents, affects Ca2+ entry. This addresses the role of outward K+ currents in shaping Ca2+ entry. Third, by replaying a single APW into several cells at different stages, we could ask how Ca2+ current properties, independent of action potential waveform, shape Ca2+ entry.

The first type of experiment – measuring the normal developmental profile of Ca2+ entry – showed that despite a 4-fold shortening of the action potential during maturation, total Ca2+ entry during the course of a single spike changed very little. The increase in ICa density almost exactly compensated for spike shortening. What did change was the time course of Ca2+ entry. During spontaneous activity in immature cells, Ca2+ entry was not only spread over the entire duration of the spike, but also occurred during the interspike voltage trajectory. The result is that Ca2+ entry almost never ceases during a burst of spontaneous activity. In contrast, Ca2+ entry in mature muscle is restricted to the spike itself. The compensation of reduced spike duration by the rise in ICa density suggests a tight coordination of the development of the mature ICa with that of the Ca2+-activated K+ current, which is responsible for shortening the spike (Davis et al. 1995). This coordination occurs despite the fact that IK(Ca) development depends on spontaneous activity whereas ICa(m) development does not (Dallman et al. 1998). It remains to be seen whether keeping total Ca2+ influx constant during development translates into similar cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients with each action potential at early and late stages. The changes in the kinetics of Ca2+ entry alone could alter the amplitude of the Ca2+ transients with each spike, as could changes in several other properties of the cells, such as the physical location of the Ca2+ channels or the efficiency of intracellular Ca2+ buffering and uptake mechanisms.

The compensation of decreased spike duration by increased ICa density is purely a function of ICa density, and does not depend on ICa type. By imposing a single APW on cells with different ICa densities and different proportions of ICa(i) and ICa(m), we showed that the relationship between total Ca2+ flux and ICa density was the same for ICa(i) and ICa(m) (Fig. 5). In contrast, the spreading out of Ca2+ entry over the entire waveform of spontaneous activity is a function of the particular properties of ICa(i). In immature cells, the more negative voltage dependence of ICa(i) (and a smaller contribution from reopening of inactivated channels) results in about 40 % of Ca2+ entry occurring between spikes during bursts of activity (Fig. 6). When the same activity waveforms are replayed into mature cells, only 24 % of the Ca2+ entry occurs between spikes. Because the residual ICa(i) in mature cells contributes about 15 % of the total ICa, ICa(m) itself probably only allows about 18 % of Ca2+ entry to occur between spikes. When mature APWs are played into mature cells, almost no Ca2+ entry occurs between spikes, which take off abruptly from a negative resting potential.

The developmental transition from the inactivating ICa(i) to the sustaned ICa(m) also mediates the transition in firing properties that occurs during maturation. In immature muscle, activity is slow and spontaneous. Replaying immature APWs into these cells at frequencies that approximate those during spontaneous activity results in a gradual decrease in peak ICa(i) due to accumulating inactivation, which is not seen when inactivation is prevented by external barium. The decrease reaches an asymptotic value of about 45 % of the initial current in about 20 s (Fig. 7B), which is the average duration of bursts during spontaneous activity (Dallman et al. 1998). This suggests that ICa(i) inactivation may serve to limit burst duration during spontaneous activity, which might limit total Ca2+ entry to acceptable values. ICa(m) does not show such accumulating inactivation, a property which is clearly important in allowing high-frequency firing of mature muscle during larval swimming.

Taken together, these results clarify the complex interplay between Ca2+ and K+ current development, action potential waveform and Ca2+ entry that characterize the transition between the immature and mature states of ascidian muscle. The disappearance of the inward rectifier just after neurulation triggers spontaneous activity. The spontaneous action potentials are long in duration, because the outward K+ curent expressed at this time is slowly activating, and Ca2+ entry is virtually continuous during bursts of activity, because the interspike voltage trajectory falls in a range where ICa(i) is activated. A rapidly activating IK would not permit spikes to be of sufficient duration to admit enough Ca2+ to trigger activity-dependent developmental programmes. If the spikes were mediated by ICa(m), instead of ICa(i), Ca2+ entry would be in brief pulses rather than long-lasting waves. ICa(i) inactivation limits bursts of spontaneous activity, and recovery from accumulating inactivation may set silent periods between bursts. The resulting cycles of long-lasting waves of Ca2+ entry may be critical in triggering second messenger systems involved in activity-dependent development.

As the muscle cells mature, it is essential that they gain the ability to engage in high-frequency contraction-relaxation cycles required for larval swimming and dispersal. To do so, action potential duration must shorten and spikes must no longer occur spontaneously. These properties are created by the re-expression of the inward rectifier, which stabilizes the resting potential, and by expression of a rapidly activating IK(Ca), which shortens the spike. IK(Ca) expression is activity dependent, so in a sense spontaneous action potentials result in their own shortening. However, if this shortening occurred without any changes in ICa density, Ca2+ entry would be greatly reduced (see Fig. 5), which would probably reduce contractile output to unacceptably low levels. To compensate, ICa density increases so as to precisely compensate for decreased spike duration, and Ca2+ entry remains unchanged in amplitude. To ensure that Ca2+ entry during mature spikes is confined to the spike itself and that spikes can repeat at high frequency, properties required for rapid contraction and relaxation cycles, increased ICa density is mediated by expression of a new ICa (ICa(m)), which has a more positive voltage of activation than ICa(i), and which does not inactivate.

Low-threshold, or T-type Ca2+ currents also exist in these cells, although we have not considered their contribution to Ca2+ entry during spontaneous activity. Because T-type Ca2+ currents are activated at negative voltages, where Ca2+ driving force is large, they can contribute more to Ca2+ entry than would be expected from their density as measured in step clamp experiments (McCobb & Beam, 1991). However, the voltage excursions during spontaneous activity in ascidian muscle fall entirely within a range where the T-type Ca2+ current would be inactivated. This and the fact that the current is found is fewer than half the cells indicate that it plays little role in Ca2+ entry. It may, however, be important in initiating the bursts of activity.

These results indicate that a complex and subtle relationship exists between developmental changes in action potential waveform, Ca2+ entry and the properties of the ion channels that mediate them. This relationship exists in the context of a cell in which Ca2+ entry plays clearly defined roles in both the immature and mature states. Our results may be particularly relevant to similar situations such as might be found in growth cones and presynaptic terminals, or in smooth and cardiac muscle.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant HD17486 to W.J.M. from the National Institutes of Health, by training grant BIR 9256532 to J.E.D. from the National Science Foundation, and by a predoctoral fellowship to J.B.D. from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- Dallman JE, Davis AK, Moody WJ. Spontaneous activity regulates calcium-dependent K+ current expression in developing ascidian muscle. The Journal of Physiology. 1998;511:683–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.683bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AK, Greaves AA, Dallman JE, Moody WJ. Comparison of ionic currents expressed in immature and mature muscle cells of an ascidian larva. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:4875–4884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04875.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gola M, Hussy N, Crest M, Ducreux C. Time course of Ca2+ and Ca2+-dependent K+ currents during molluscan nerve cell action potentials. Neuroscience Letters. 1986;70:354–359. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90578-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves AA, Davis AK, Dallman JE, Moody WJ. Co-ordinated modulation of Ca2+ and K+ currents during ascidian muscle development. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:39–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Spitzer NC. Breaking the code: regulation of neuronal differentiation by spontaneous Ca2+ transients. Developmental Neuroscience. 1997;19:33–41. doi: 10.1159/000111183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn R, Marty A. Muscarinic activation of ionic currents measured by a new whole-cell recording method. Journal of General Physiology. 1988;92:145–159. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, Sugimori M, Simon SM. Transmission by presynaptic spike-like depolarization in the squid giant synapse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1982;79:2415–2419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.7.2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCobb DP, Beam KG. Action potential waveform voltage-clamp commands reveal striking differences in Ca entry via low and high voltage-activated calcium channels. Neuron. 1991;7:119–127. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90080-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody WJ. Critical periods of early development created by the coordinate modulation of ion channel properties. Perspectives on Developmental Neurobiology. 1995;2:309–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody WJ. The development of voltage-gated ion channels and its relation to activity-dependent development events. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 1998a;39:159–185. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody WJ. The control of spontaneous activity during development. Journal of Neurobiology. 1998b;37:97–109. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199810)37:1<97::aid-neu8>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody WJ, Bosma MM. Hormone-induced loss of surface membrane during maturation of starfish oocytes. Developmental Biology. 1985;112:396–404. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DF, Boyce LH, Davis MB, Kriegstein AR. Excitatory GABA responses in embryonic and neonatal cortical slices demonstrated by gramicidin perforated-patch recordings and calcium imaging. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:6414–6423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06414.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS, Fox AP. Multiple Ca2+ currents elicited by action potential waveforms in acutely isolated adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:1789–1801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01789.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesinger PA, Lansman JB. Reopening of Ca2+ channels in mouse cerebellar neurons at resting membrane potentials during recovery from inactivation. Neuron. 1991;7:755–762. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer NC. A developmental handshake: neuronal control of ionic currents and their control of neuronal differentiation. Journal of Neurobiology. 1991;22:659–673. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]