Abstract

The objective was to evaluate the pro-inflammatory response of bovine macrophages towards Porphyromonas levii, an etiologic agent of acute interdigital phlegmon, by evaluating the mRNA expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and interleukin 8 (IL-8). Bovine macrophages detect the presence of bacteria, such as P. levii, and respond by upregulating transcription of the genes for pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β in addition to the neutrophil chemoattractant IL-8. Monocytes were isolated from blood obtained from Holstein steers. These cells were cultured and differentiated into macrophages over 7 d, followed by exposure to P. levii, Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or tissue culture medium for 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, or 24 h. Total RNA was extracted, and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction was conducted to examine the presence of TNF-α, IL-1β, or IL-8 mRNA. Products were visualized on agarose gels to determine the presence or absence of cytokine mRNA amplified DNA. Bovine macrophages, when exposed to P. levii or E. coli LPS, produced mRNA for TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8. Expression of all 3 cytokines was higher in the P. levii and LPS-exposed macrophages at all time points examined, compared with tissue culture medium-treated cells. Expression of these cytokines by macrophages is likely directly involved in orchestration of the immune response, and particularly in neutrophil recruitment to affected tissues in acute interdigital phlegmon.

Introduction

Acute interdigital phlegmon, or bovine footrot, is an important anaerobic bacterial infection that affects a large proportion of cattle within all sectors of agriculture. It primarily affects the interdigital region of the bovine foot and characteristically involves inflammation and lameness. Porphyromonas levii and Prevotella intermedia, obligatory anaerobic gram-negative bacterial species, have been isolated from cases of acute interdigital phlegmon in western Canada (1). Typically the bacterial species Fusobacterium necrophorum, Bacteroides melaninogenicus and B. (Dichelobacter) nodosus are described as the etiologic agents of footrot in bovids (2). Current taxonomic changes within the Bacteroides genus have led to the reclassification of several bacteria and some of these changes involve the pathogens of acute interdigital phlegmon. B. melaninogenicus has been reclassified into 3 distinct genera and 17 unique species (3). Both P. levii and P. intermedia, bacteria recently identified in acute interdigital phlegmon, would have previously been classified as B. melaninogenicus. Reports associating F. necrophorum and B. melaninogenicus with footrot may have encompassed a wider range of bacterial species than previously thought. In our laboratory, acute interdigital phlegmon was experimentally induced using either P. levii or P. intermedia in conjunction with F. necrophorum. Our results have shown that although both isolates were capable of inducing infection, P. levii caused markedly more severe clinical signs than P. intermedia (4).

To date, there has been little research into the immunopathology of this disease. Our objective was to evaluate some of the early inflammatory steps that are involved in acute interdigital phlegmon with respect to the novel isolate P. levii. Past work in our laboratory has involved P. levii and the role of neutrophils in this infection (5,6). Neutrophils have been shown to be an important immune cell in this disease, and they form much of the inflammatory discharge seen in unresolved infections. In particular, we have shown that specific humoral immunity is important for neutrophil clearance of P. levii, and, in the absence of immunoglobulin, neutrophils are poorly phagocytic. Our objective in this work was to investigate the events prior to neutrophil recruitment that are likely seen in acute interdigital phlegmon. These events are initiated by cells within the affected tissues and often involve specific responses by macrophages (7). Resident tissue macrophages are one of the first immune cells that typically encounter foreign particles such as these pathogens (7,8). Macrophages function to phagocytose and kill bacteria as well as orchestrate subsequent cellular and humoral responses (8). They mobilize additional leukocytes by the production of cytokines and chemokines (8). These factors can act as chemical attractants for recruitment of additional immune cells, including neutrophils, as well as functioning in cell activation at local inflammatory foci (7).

Specifically, the objective of this study was to examine and evaluate the induction of mRNA expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin 1β (IL-1β), as well as the chemokine interleukin 8 (IL-8), in cultured bovine macrophages exposed to P. levii. The function of these particular pro-inflammatory cytokines is to communicate to adjacent tissues the presence of an inflammatory stimulus (9). In particular, TNF-α and IL-1β can increase neutrophil recruitment by stimulating a variety of cell types, including endothelial cells (10). Interleukin 8 functions as a potent chemoattractant that stimulates neutrophil migration towards the infected site, as well as inducing antimicrobial activities in neutrophils once present in the infected area (11). Therefore, if macrophages have the capacity to detect P. levii and initiate the production of these pro-inflammatory cytokines, the neutrophil-mediated resolution of infection should not be limited or restricted at that stage.

Materials and methods

Preparation of bacteria

Porphyromonas levii was grown to logarithmic phase in brain-heart infusion (BHI) broth (Mikrobiologie BDH, Darmstadt, Germany) supplemented with 0.05% hemin (Sigma Diagnostics Inc., St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and 0.01% vitamin K (Sigma Diagnostics Inc.), in a strictly anaerobic atmosphere of 5% CO2, 5% H2, and 90% N2 at 37°C, in a gloveless anaerobic chamber (Bactron II Anaerobic Chamber; Sheldon Laboratories, Cornelius, Oregon, USA) (5). Broth cultures were washed 3 times and resuspended in sterile pyrogen-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma Diagnostics Inc.) to a 0.5 McFarland Standard [≈ 1.5 × 108 colony-forming units per milliliter (cfu/mL)]. To ensure purity, bacteria were streaked onto non-selective Brucella laked blood agar (BLBA) plates supplemented with hemin and vitamin K (Dalynn Laboratories, Calgary, Alberta) before and after washing. Colony-forming units were determined by a 10-fold dilution series plated onto BLBA. The final P. levii preparation of 1.5 × 108 cfu/mL was further diluted in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Grand Island, New York, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco BRL Life Technologies) to establish a bacterial concentration of 2 × 106 cfu/mL for all macrophage exposure experiments.

Preparation of monocyte-derived macrophages

Procedures were conducted in accordance with the standards of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and were approved by the Life & Environmental Sciences Animal Care Committee of the University of Calgary. Bovine blood was collected from Holstein steers using jugular venipuncture and centrifuged at 1200 × g for 20 min to separate cellular fractions. Mononuclear cells were isolated from the buffy coat and mixed 1:1 with sterile saline (12). The buffy coat cell mixture was overlaid on a density gradient (Histopaque-1077; Sigma Diagnostics Inc.), and centrifuged for 40 min at 1500 × g in a swinging-bucket rotor (12). The mononuclear cells were washed twice in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS; Gibco BRL Life Technologies), quantified, and then seeded into 25 cm2 tissue culture-treated flasks (Falcon; Becton-Dickinson, Lincoln Park, New Jersey, USA) for adherence and differentiation. Tissue culture flasks were seeded with mononuclear cells at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/mL, approximately 15 mL per flask. Following a 1-hour incubation, cells were washed with prewarmed Ca2+/Mg2+ HBSS to remove non-adherent lymphocytes. Adherent monocytes were then cultured in IMDM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 μg/mL of streptomycin (Sigma Diagnostics Inc.), and 0.08 mg/mL of tylosin (Sigma Diagnostics Inc.) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere (12). Differentiation of monocytes into macrophages occurred over 7 d, and cells were characterized using non-specific esterase, CD68 antigen staining, and trypan blue exclusion staining (12,13). To evaluate CD68 antigen staining, monocytes were seeded into 8-well tissue culture-treated chamber slides (Lab Tek; Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, Illinois, USA) at a concentration of 2 ×106 cells/mL and stained following 7 d of incubation. Cells were fixed in prechilled 5% (v/v) acetic acid in methanol for 10 min at −20°C and then digested for 30 min at 37°C with a 0.1% (v/v) solution of 1X trypsin/triethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) in PBS with 0.2% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (Sigma Diagnostics Inc.) and 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 (Sigma Diagnostics Inc.). Cells were washed with PBS and blocked with 10% goat serum in a 1.0 mM tetramisole-PBS solution prior to the addition of a 1:50 dilution of anti-CD68 monoclonal antibody (EMB11; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) (13). Cells were incubated overnight in the primary antibody at 4°C. Following another washing with PBS, a 1:100 rabbit anti-mouse alkaline phosphate-conjugated IgG (CB1542; Cortex BioChem, Inc., San Leandro, California, USA) was incubated with the cells for 40 min at 37°C (13). Slides were washed and CD68 antigen detected using a 5-minute room temperature incubation with Sigma Fast Red TR/Naphthol AS-MX (Sigma Diagnostics Inc.). Macrophages were counterstained with Gill's hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific, Nepean, Ontario) for 1 min, followed by a 1-minute incubation in saturated lithium carbonate. Macrophages were observed under 1000X magnification by direct light microscopy and quantified for the presence of CD68 antigen (as indicated by red staining within the cytoplasm). To determine the presence of CD68 antigen, 300 cells per chamber were quantified.

For non-specific esterase staining, cells were cultured in 8-well tissue culture-treated chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International) and stained at 7 d to evaluate differentiation. Cells were fixed for 30 s, rinsed 4 times, and then incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C with the esterase substrate solution, made according to previously published methods (14). Following incubation, cells were washed with 3 changes of distilled water and counterstained in a 1% (w/v) methyl green solution, rinsed, and then air dried (14). Macrophages were examined under light microscopy at 1000X and 300 cells per chamber were counted. A heavy red brown precipitate in the cell cytoplasm indicated an esterase-positive cell.

Macrophage exposure studies

Macrophages were exposed to P. levii, Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS, serotype O26:B6, Sigma Diagnostics Inc.) (positive control), or tissue culture medium with 10% FBS (negative control) to evaluate cytokine mRNA expression. Prior to exposure, IMDM was aspirated from cultured macrophages, and 5 mL of P. levii (2 ×106 cfu/mL), E. coli LPS (5 μg/mL), or IMDM with 10% (v/v) FBS was added to the individual flasks. Macrophages were exposed to one of each of the 3 stimulants for 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Following exposure, media were removed and the macrophages rapidly lysed with 2 mL of TRI REAGENT (Sigma Diagnostics Inc.).

Total RNA was isolated from the macrophages by a modified phenol-chloroform extraction method using TRI REAGENT (Sigma Diagnostics Inc.) (15). The resultant cell lysates (2 mL) were placed into microcentrifuge tubes (1 mL/tube) followed by 0.3 mL of chloroform. The tubes were shaken vigorously for 15 s, set to stand for 15 min, and then centrifuged for 15 min at 12 000 × g. The clear upper aqueous phase was carefully collected and transferred to a new, sterile, 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube (15). Isopropanol (550 μL) was added to each tube. After mixing, the tube stood for 10 min and then was centrifuged for 10 min at 12 000 × g, resulting in the precipitation of total RNA. The supernatant was decanted and the total RNA washed with 75% ethanol, vortex mixed, and centrifuged for 5 min at 7500 × g (15). The ethanol was removed, and the RNA pellet was dried and resuspended in 20 μL of molecular-grade (free of RNase and DNase) H2O (Sigma Diagnostics Inc.). A DNA-removal step was conducted with the DNase treatment and removal kit (DNA-free; Ambion Inc., Austin, Texas, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The total RNA from each sample was evaluated for purity and quantified by A260 with the GeneQuant RNA/DNA Calculator spectrophotometer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Baie d'Urfé, Quebec). The total RNA (250 ng) was used for the one-step reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Laval, Quebec). Primers were selected from previously published material in which RT-PCR was used to detect the bovine cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 (16,17). The primer sequences were as follows: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH) (356 bp) forward 5′-GAGATGATGACCCTTTTGGC-3′, reverse 5′-GTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACG-3'; TNF-α (298 bp) forward 5'-CGGTAGCCCACGTTGTA-3′, reverse 5′-TGGCCTCAGCCCACTCT-3′; IL-1β (279 bp) forward 5′-AATGAACCGAGAAGTGG-3′, reverse 5′-TTCTTCGATTTGAGAAG-3′; IL-8 (304 bp) forward 5′-GACTTCCAAGCTGGCTGTTG-3′, reverse 5′-CATGGATCTTGCTTCTCAGCTC-3′. Reverse transcription was conducted for 30 min at 55°C for GADPH, TNF-α and IL-8 sequences and at 50°C for the IL-1β cDNA. The PCR was completed under the following conditions: 94°C hot start for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C melting for 30 s, 57°C annealing for 30 s, and 68°C elongation for 45 s. A final 3.5-minute prolonged elongation step at 68°C was conducted upon completion of the 40 cycles. For IL-8 PCR, an annealing temperature of 58°C was used, and for the IL-1β PCR the annealing temperature was optimized for 51°C. For each RT-PCR reaction the 50 μL volume contained 10 μL of 5X RT-PCR buffer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), 1 μL of 0.2 mM dNTP mix solution, 0.4 μM each of the appropriate forward and reverse primers, 2.5 μL of 5 mM dithiothreitol, 5 U of RNase inhibitor, and 1 μL of Expand High Fidelity enzyme mix containing avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase, Taq DNA polymerase, and a proofreading polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The negative RT control contained 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Fisher Scientific) instead of the Expand High Fidelity enzyme mix. Amplified samples were visualized on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide to confirm the correct size and presence of PCR product using the BioRad Gel Doc 2000 with Quantity One BioRad Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA). The PCR products were sequenced and analyzed to confirm the presence of the appropriate cytokines. Amplification products for GADPH were also sequenced.

Results

Macrophage differentiation

Macrophages were positive for both non-specific esterase and CD68 antigen following 7 d of incubation after monocyte isolation. Macrophages displayed high amounts of the non-specific esterase enzyme per 300 cells viewed as the cells differentiated over time (0 to 7 d). Cells examined at 7 d were 94.13% ± 0.58% [mean ± standard error (SE)] positive (n = 18) for non-specific esterase, and this was significantly different from the presence of the enzyme after 1 d in culture: 36.5% ± 1.89% (n = 18) [P 0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunn's test for multiple comparisons]. When CD68 antigen staining was conducted and quantified, similar results were seen. By day 7, the differentiated macrophages had a significant (P 0.05) increase in the presence of CD68 when compared with the cell staining immediately following isolation (day 0). At day 0, the number of CD68-positive cells was 7.06% ± 2.08%, whereas at day 7 the number was 99.47% ± 0.23% (n = 5) (P 0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA and Dunn's test for multiple comparisons).

Macrophage exposure studies

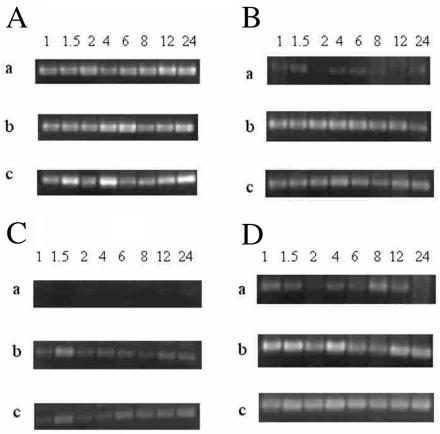

The RT-PCR was used to determine the effect of P. levii on the expression of cytokine-specific mRNA in bovine macrophages. As shown in Figure 1A, macrophages exposed to any of the 3 treatment groups had similar levels of mRNA expression of the internal standard GADPH. Figure 1, 1, and 1D illustrate the RT-PCR products of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8, respectively, when bovine macrophages were exposed to tissue culture medium, E. coli LPS, or P. levii. All cytokines of interest (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8) were detected in P. levii-exposed and LPS-exposed macrophage samples. In the control group (tissue culture medium), macrophages expressed qualitatively lower levels of mRNA for the cytokines examined (Figure 1B, 1C, and 1D). At all time points, the negative IMDM control macrophages contained lower mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 cytokines when compared with P. levii-stimulated or LPS-exposed macrophages.

Figure 1. A: The mRNA expression of GADPH by bovine macrophages over 24 h, assessed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) when the macrophages were exposed to: a) Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (control), b) 2 × 106 cfu/mL of Porphyromonas levii, or c) 5 μg/mL of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. Equal amounts of total RNA (250 ng) were reverse transcribed, amplified using PCR, and electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels. B: mRNA expression of TNF-α by bovine macrophages over 24 h (assessed by RT-PCR) when macrophages were exposed as described in 1A. C: mRNA expression of IL-1β by bovine macrophages over 24 h (assessed by RT-PCR) when macrophages were exposed as described in 1A. D: mRNA expression of IL-8 by bovine macrophages over 24 h (assessed by RT-PCR) when macrophages were exposed as described in 1A.

Expression of cytokine mRNA was evident as early as 1 h postexposure in the P. levii-exposed and LPS-exposed samples. Qualitative assessment of the P. levii-exposed macrophages indicated that IL-1β mRNA was present maximally at approximately 1.5 h after initial exposure (Figure 1C). Expression of TNF-α mRNA was elevated above the negative control for a longer time than IL-1β mRNA in both the P. levii-exposed and the LPS-exposed macrophages. Messenger RNA levels for TNF-αwere high in the P. levii test group over the entire 24-hour period. The LPS-exposed macrophages showed similar trends for TNF-α mRNA expression (Figure 1B). As seen with the TNF-α and mRNA expression, a background level of IL-8 mRNA was present in the negative control group (IMDM) (Figure 1D). Levels of IL-8 mRNA expression were variable in the negative control, but when compared with IL-8 mRNA expression in the P. levii-exposed and LPS-treated macrophages, baseline expression was much lower. At all time points evaluated over the course of the 24-hour experiment, IL-8 was elevated in the P. levii-exposed and LPS-treated macrophages, compared with controls (Figure 1D). Haphazardly selected bands of PCR products were extracted from the gel and subjected to DNA sequencing to confirm the presence of bovine GADPH, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 cytokine mRNA. The GADPH sequence and all of the cytokine PCR products evaluated had correct sequences corresponding to the known database of sequences (data not shown).

Discussion

Tissue macrophages are one of the first immune cells to encounter foreign material such as pathogens in the interdigital region of the bovine hoof. It was our objective to examine P. levii, a recently identified footrot pathogen, and the pro-inflammatory cytokine response of macrophages upon exposure to this bacterial species. Data from this study suggest that macrophages can respond to P. levii as early as 1 h postexposure with increasing transcription of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, as well as an increased presence of mRNA transcripts for the neutrophil chemoattractant IL-8. Translation of these mRNA molecules can lead to elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 and could result in increased neutrophil recruitment (10). Increased expression of IL-8 has been associated with enhanced neutrophil recruitment via chemotaxis, which can accelerate the clearance of footrot pathogens through phagocytosis by neutrophils that have migrated into the affected site (10).

Past research that examined the production of IL-1β by immune cells stimulated with other Porphyromonas spp. has shown that IL-1β can be produced from monocytes and macrophages (18,19), in agreement with our findings. In these P. levii-exposed macrophages, mRNA of IL-1β appears to decline over 24 h, but LPS-induced IL-1β mRNA expression levels did not decline (Figure 1C). It may be that, over the extended incubation period, phagocytosis of P. levii was occurring, resulting in a decrease in the stimuli bombarding the macrophages. Porphyromonas levii would initially stimulate IL-1β production in cells, but phagocytosis would result in a decline over time as fewer P. levii were available to stimulate the macrophages. When the expression profile of E. coli LPS-exposed macrophages was examined a biphasic response was seen, IL-1β mRNA peaking at approximately 1.5 h and again at 6 h (Figure 1C). This was not seen in the P. levii-exposed macrophages (Figure 1C).

The mRNA expression of TNF-α in both P. levii-exposed and LPS-exposed macrophages was elevated, compared with that in controls, at all time points examined (Figure 1B). These data did not clearly illustrate any obvious differences in expression over time. One of the initial cytokines produced by activated macrophages, TNF-α is thought to have a large influence in the clinical signs observed during acute inflammatory infections (20). Although TNF-α can be synthesized by numerous cell types, it is primarily produced by macrophages and monocytes, and particularly following exposure to LPS from gram-negative bacteria (20,21,22). That bovine macrophages had increased levels of TNF-α mRNA expression following exposure to commercial LPS and P. levii was anticipated (6,20,22). Our results were consistent with those of other investigators who used distinct Porphyromonas species to study the effects of LPS on TNF-α production by monocytes or macrophages (23,24,25). The expression of IL-8 mRNA was markedly increased in both the P. levii-exposed and the LPS-exposed macrophages over the entire 24-hour period, compared with the medium-exposed macrophages (Figure 1D). There were detectable levels of IL-8 mRNA in the controls (Figure 1D). Expression in controls may be due to the production of low levels of TNF-α resulting from activation of macrophages when culture medium was added. The fact that TNF-α can stimulate macrophages to elicit further cytokine production (specifically IL-8) may explain the comparatively elevated levels of IL-8 mRNA expression in the control macrophages (26,27). It was evident that P. levii and LPS can activate bovine macrophages to stimulate the production of IL-8 mRNA directly; this is in accordance with the previous theory that macrophages induced by LPS can stimulate the production of IL-8 (27,28,29). The upregulation of IL-8, a potent neutrophil chemoattractant, may lead to the infiltration and subsequent activation of neutrophils in the bovine foot (26,27,28). To date, no one has demonstrated IL-8 mRNA expression in macrophages in the context of bovine footrot. If IL-8 mRNA expression is occurring in bovine macrophages, IL-8 may be present in the affected tissues, and this stimulus could be strong enough to elicit the infiltration of neutrophils. Modification of this IL-8 response could be important in the pathogenesis of infection. It may be of interest in the future to attempt detection of IL-8 protein in tissues by using immunohistochemical localization of this cytokine in biopsy specimens from animals with acute interdigital phlegmon.

The production of mRNA coding for the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β as well as the chemotactic cytokine IL-8 by bovine macrophages in response to P. levii may be an important initiating event for the induction of inflammation in acute interdigital phlegmon. Past research has shown that experimental induction of footrot can result in a substantial lag prior to the appearance of the clinical signs of inflammation (up to 5 or 6 d) (2,4). Although inflammation appears to be delayed in these experimental infections, neutrophils are one of the key histopathologic features in the affected tissues from animals in the feedlot (4). The expression of cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8, can have a marked effect on the establishment of inflammation, through the activation of endothelium and the infiltration of neutrophils and plasma fluids. Other studies on Porphyromonas species have shown that their large contingent of proteases includes ones that can degrade cytokines (18,30). One study indicates that P. gingivalis may have the potential to degrade the chemoattractant IL-8 (30). If P. levii has a similar potential to degrade cytokines, particularly IL-8, then this may explain the observed delay of inflammation in experimental infection models of acute interdigital phlegmon. The degradation of IL-8 and additional cytokines would reduce cell activation and neutrophil migration into the affected tissues, thus inhibiting these early features of inflammation.

The induction of inflammation is a complicated process, given the many events that are required to take place. The aim of this study was to examine the pro-inflammatory events, with particular focus on tissue macrophages and their potential role in the inflammatory process during acute interdigital phlegmon. We have shown that upon exposure to the footrot pathogen P. levii, bovine macrophages upregulate production of mRNA coding for the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, as well as the chemoattractant IL-8. The production of these cytokines may have a profound impact on the migration and activation of bovine neutrophils, a key inflammatory cell in infected tissues. On the other hand, if P. levii can directly alter the ability of these cytokines to exert their effects, inflammation may be delayed or even reduced within this infection. Further studies that examine the levels of cytokine expression in bovine tissues may aid in interpreting the activation events that initiate bovine acute interdigital phlegmon.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Alberta Agriculture Research Institute.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Douglas W. Morck, tel: 403-220-5278, fax: 403-284-1537, e-mail dmorck@ucalgary.ca

Received July 11, 2001. Accepted February 7, 2002.

Data in this manuscript were presented at the Canadian Society of Microbiologists Annual General Meeting, June 10–13, 2001 in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

References

- 1.Morck DW, Olson ME, Louie TJ, Koppe A, Quinn B. Comparison of ceftiofur sodium and oxytetracycline for the treatment of acute interdigital phlegmon (footrot) in feedlot cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;212:254–257. [PubMed]

- 2.Diseases caused by bacteria. V. In: Radostits OM, Blood DC, Gay CC, eds. Veterinary Medicine: a Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats, and Horses. 8th ed. London: Bailliere Tindall, 1994;867–870.

- 3.Jousimies-Somer HR. Update on the taxonomy and the clinical and laboratory characteristics of pigmented anaerobic gram- negative rods. Clin Infect Dis 1995;20:S187–191. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Morck DW, Merrill JK, Olson ME, Sparrow DG, Dick P. Experimentally induced acute bovine footrot (interdigital phlegmon): treatment with tilmicosin. Proc 20th World Buiatrics Congress, 1998:517.

- 5.Lobb DA, Loeman HJ, Sparrow DG, Morck DW. Bovine polymorphonuclear neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis and an immunoglobulin G2 protease produced by Porphyromonas levii. Can J Vet Res 1999;63:113–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Sparrow DG, Gard S, Buret A, Ceri H, Olson M, Morck DW. Expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) by bovine endothelial cells in vitro. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:S178–S179. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Dinarello CA. Interleukin 1: A proinflammatory cytokine. In: Gallin JI, Snyderman R, eds. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999:443–461.

- 8.Hauschildt S, Kleine B. Bacterial stimulators of macrophages. Int Rev Cytol 1995;161:263–331. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Moldawar LL. Biology of proinflammatory cytokines and their antagonists. Crit Care Med 1994;22:S3–S7. [PubMed]

- 10.Fantone JC, Ward PA. Inflammation. In: Farber RE, ed. Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1994:33–66.

- 11.Sundy JS, Patel DD, Haynes BF. Cytokines in normal and pathogenic inflammatory responses. In: Gallin JI, Snyderman R, eds. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999: 433–441.

- 12.Bounous DI, Enright FM, Gossett KA, Berry CM. Phagocytosis, killing, and oxidant production by bovine monocyte-derived macrophages upon exposure to Brucella abortus strain 2308. Vet Immun Immunopathol 1993;37:243–256. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ackermann MR, DeBey BM, Stabel TJ, Gold JH, Registerm KB, Meehan JT. Distribution of anti-CD68 (EBM11) immunoreactivity in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded bovine tissues. Vet Pathol 1994;31:340–348. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Partridgen LJ, Dransfield I. Isolation and characterization of mononuclear phagocytes. In: Gallagher G, Rees RC, Reynolds CW, eds. Tumor Immunobiology: a Practical Approach. New York: IRL Press, 1993:99–118.

- 15.Chomczynski P. A reagent for the single step simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA, and proteins from cell and tissue samples. Biotechnology 1993;15:532–536. [PubMed]

- 16.Goff WL, O'Rourke KI, Johnson WC, Lacy PA, Davis WC, Wyatt CR. The role of IL-10 in iNOS and cytokine mRNA expression during in vitro differentiation of bovine mononuclear phagocytes. J Interfer Cytok Res 1998;18:139–149. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mathy NL, Walker J, Lee RP. Characterization of cytokine profiles and double-positive lymphocyte subpopulations in normal bovine lungs. Am J Vet Res 1997;58:969–975. [PubMed]

- 18.Lamont RJ, Jenkinson HF. Life Below the Gum Line: Pathogenic Mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 1998;62:1244–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Saito A, Sojar HT, Genco RJ. Interleukin-1 gene expression in macrophages induced by surface protein components of Porphyromonas gingivalis: role of tyrosine kinases in signal transduction. Oral Microbiol Immunol 1997;12:135–140. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Wang H, Tracey KJ. Tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-6, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 in inflammation. In: Gallin JI, Snyderman R, eds. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999: 471–486.

- 21.Mannel DN, Echtenacher B. TNF in the inflammatory response. Chem Immunol 2000;74:141–161. [PubMed]

- 22.Tracey KJ, Cerami A. Tumor necrosis factor: a pleiotropic cytokine and therapeutic target. Annu Rev Med 1994;45:491–503. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kirikae T, Nitta T, Kirakae F, et al. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) of oral black-pigmented bacteria induce tumor necrosis factor production by LPS-refractory C3H/HeJ macrophages in a way different from that of Salmonella LPS. Infect Immun 1999; 67:1736–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Shapira L, Houri Y, Barak V, Soskolne WA, Halabi A, Stabholz A. Tetracycline inhibits Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide-induced lesions in vivo and TNFα processing in vitro. J Periodont Res 1997;32:183–188. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Shapira L, Champage C, Van Dyke TE, Amar S. Strain-dependent activation of monocytes and inflammatory macrophages by lipopolysaccharide of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun 1998;66:2736–2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Adams DH, Lloyd AR. Chemokines: leukocyte recruitment and activation cytokines. Lancet 1997;349:490–495. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Mukaida N, Okamoto S, Ishikawa Y, Matsushima K. Molecular mechanisms of interleukin-8 gene expression. J Leukocyte Biol 1994;56:554–558. [PubMed]

- 28.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Chemokines. In: Gallin JI, Snyderman R, eds. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999:419–431.

- 29.Harada A, Sekido N, Akahoshi T, Wada T, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Essential involvement of interleukin 8 (IL-8) in acute inflammation. J Leukocyte Biol 1994;56:559–563. [PubMed]

- 30.Madianos PN, Papapanou PN, Sandros J. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection of oral epithelium inhibits neutrophil transepithelial migration. Infect Immun 1997;65:3983–3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]